1. Introduction

In a globalised economy weakened by a profound water crisis and the urgent need to transition towards regenerative economic models, the circular water economy has now become a strategic axis for achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 6, 9, 11, 12 and 13 [

1,

2,

3] . This transition towards a circular approach that prioritises the reuse, regeneration and recovery of water resources is clearly a critical response to the challenges of water scarcity and environmental stress faced by approximately 36% of the world's population. However, this technical and environmental imperative faces significant structural resistance that limits its systematic implementation, particularly in emerging economies (developing countries) where financial constraints, institutional gaps and complex socio-cultural barriers converge.

The review of documented progress in the implementation of water reuse technologies has revealed geographically differentiated patterns that suggest the existence of contextual factors. Europe has consolidated integrated circular water economy systems that operate with efficiencies greater than 85% in industrial plants. Asia has demonstrated the technical and economic viability of advanced membrane technologies with recovery rates of 90%. Meanwhile, in Latin America, fragmented implementations remain that fail to achieve sustainable scalability [

4,

5,

6] . This regional disparity suggests that technical limitations represent only a fraction of the factors explaining the success or failure of circular initiatives, highlighting the critical relevance of organisational, psychosocial and institutional variables traditionally overlooked in academic and public policy analysis.

Specialised literature has favoured techno-economic approaches which, although they provide evidence on technical feasibility and financial profitability, omit explanatory dimensions that are crucial for understanding the differential adoption of reuse technologies. This limitation is particularly evident in the scant attention given to organisational factors such as financial capacity, managerial leadership, organisational culture towards sustainability, and availability of technical resources, which have been studied in a fragmented manner without consideration of their synergistic effects [

7]. At the same time, the psychosocial dimension, which includes attitudes towards environmental innovation, risk perception, social norms, and technical knowledge of staff, remains one of the most significant gaps in current research, despite growing evidence of its relationship with environmental technology adoption processes [

8,

9] .

At the same time, it is important to note that there is still a critical knowledge gap regarding the real impact of water reuse technologies implemented under circular economy principles. Although there is abundant literature on theoretical potential benefits, empirical evidence on measurable impacts in terms of water consumption reduction, operational efficiency, economic profitability, and social acceptance remains fragmented and methodologically inconsistent. This lack of rigorous impact assessments creates uncertainty for organisational and institutional decision-makers about the real effectiveness of investments in circular technologies, limiting the expansion of successful initiatives and perpetuating dependence on linear water management models. Particularly in emerging economies, the absence of longitudinal studies documenting medium- and long-term impacts makes it difficult to build solid business cases that justify the transition to circular practices.

Analysis of failed implementations and pilot projects that were not scaled up reveals that technical limitations account for only 23% of the factors explaining failure, while governance barriers, cultural resistance and regulatory gaps account for the remaining 77% [

10,

11]. This empirical evidence corroborates the association of non-technical factors with the success of circular initiatives, particularly in institutional fragmentation where multiple government agencies with overlapping jurisdictions generate regulatory uncertainty and increase transaction costs for organisations seeking to implement circular technologies. Additionally, the persistence of linear water management paradigms, mistrust of reuse technologies, and negative perceptions of recycled water quality create cultural resistance that amplifies initial technical and economic barriers [

12,

13] .

The application of structural equation modelling (SEM) to analyse complex causal relationships and associations between organisational, psychosocial and institutional factors represents a methodological opportunity that has thus far been unexplored in this specific field. Unlike traditional correlational approaches, SEM modelling allows us to identify direct and indirect effects, associations and moderating relationships that explain the mechanisms underlying the adoption of circular technologies. This methodological approach is particularly relevant for examining complex phenomena where multiple variables interact simultaneously, as occurs in organisational environmental innovation processes.

Therefore, this research aims to analyse, using a structural equation model, the associations between organisational, psychosocial and institutional factors and the implementation of water reuse technologies within the framework of the circular economy in industrial and urban contexts. Specifically, it seeks to evaluate how organisational characteristics relate to the adoption of reuse technologies, examine the associations of psychosocial factors with decisions to implement reuse systems, and analyse the relationship between institutional factors and the successful implementation of circular water economy technologies.

This multidisciplinary integration allows specific levers for intervention to be identified at each analytical level, providing elements for the design of differentiated public policies and contextualised organisational strategies.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.1.1. Circular Water Economy: Conceptual and Operational Differentiation

The circular water economy is a paradigm under study that transcends conventional integrated water resource management through the implementation of three interconnected systemic principles : (1) elimination of waste and pollution through regenerative design, (2) maintenance of water and nutrients in multiple production cycles, and (3) restoration of natural systems through biomimetic treatment processes [

14,

15].

This reconceptualisation operates through closed-loop architectures where industrial effluents are transformed into inputs for subsequent processes, sequential cascades that optimise value extraction per unit of water, and comprehensive valorisation of by-products such as nutrients and energy [

16]. Unlike conventional reuse, which prioritises operational efficiency, the circular water economy integrates considerations of ecosystem regeneration and absolute waste elimination [

17].

1.1.2. Multilevel Integrative Framework: Theoretical Foundation

The organisational adoption of circular water economy technologies emerges from the complex convergence of endogenous organisational capabilities, individual psychosocial factors, and enabling institutional frameworks. This multilevel theoretical integration is empirically justified, given that no single analytical level adequately explains the differentiated patterns of adoption observed among organisations with comparable resource endowments or similar institutional contexts.

1.1.3. Organisational Perspective: Strategic Resources and Dynamic Capabilities

The Resource-Based View approach posits that heterogeneous organisational resources are associated with sustainable competitive advantages when they meet criteria of value, rarity, inimitability, and organisational exploitation [

18]. In the context of the circular water economy, specialised financial resources, distinctive technical capabilities, and organisational cultures oriented towards sustainability constitute strategic assets that are positively related to the successful implementation of circular systems [

19].

However, the availability of resources is a necessary but insufficient condition without dynamic capabilities that facilitate adaptive organisational reconfiguration. These capabilities include sensing routines for detecting technological opportunities, seizing processes that mobilise resources towards implementation, and reconfiguring mechanisms that adapt organisational structures to emerging technical requirements [

20,

21].

The implementation of a circular water economy requires organisational transformations that go beyond capital investment, incorporating the development of specialised technical skills, the establishment of strategic alliances with technology providers, and the re-engineering of production processes to integrate circular principles [

22,

23].

1.1.4. Psychosocial Dimension: Cognitive and Normative Mediators

Psychosocial factors operate as critical mediators between the availability of organisational resources and decisions regarding effective implementation. The Theory of Planned Behaviour specifies that attitudes towards specific technologies, organisational social norms, and perceptions of behavioural control are systematically associated with adoption intentions that precede implementation behaviours [

24].

Attitudes towards the circular water economy integrate cognitive assessments of anticipated economic benefits, perceptions of technical and operational risk, and assessments of the environmental legitimacy of reuse technologies [

25]. These cognitive assessments are particularly relevant because circular technologies require substantial modifications to established processes and generate uncertainty about operational outcomes.

Conceptual frameworks from environmental psychology integrate cognitive, affective, and normative factors into configurations that recognise the social construction of environmental perceptions [

26,

27]. Specialised technical knowledge about reuse technologies is a cognitive prerequisite linked to the informed evaluation of alternatives and the reduction of uncertainty associated with implementation, particularly when the technologies require highly specialised expertise [

28,

29].

Risk perception emerges as a critical mediator, given that reuse technologies generate concerns about water quality, technical reliability, and social acceptance that can inhibit adoption regardless of documented economic benefits [

30,

31].

1.1.5. Institutional Framework: Coercive, Normative, and Mimetic Mechanisms

Institutional theory specifies three mechanisms through which regulatory frameworks are linked to organisational technology adoption: coercive pressures derived from regulations and sanctions, normative pressures emerging from professional expectations, and mimetic pressures resulting from the imitation of legitimised organisational practices related to the implementation of circular systems [

32,

33].

Coercive pressures operate through regulations that establish discharge standards, tariff structures for fresh water use, and economic incentives for reuse that are associated with changes in organisational cost-benefit calculations. Normative pressures emerge from sectoral expectations regarding corporate environmental responsibility related to organisational legitimacy. Mimetic pressures derive from processes of imitation of successful organisations that have implemented circular technologies and documented operational and reputational benefits.

The institutional framework takes on particular relevance in contexts characterised by regulatory fragmentation, inconsistent policies and limited state capacities, which generate institutional ambiguities linked to obstacles to technological implementation [

34,

35].

1.1.6. Contextual Specificities in Emerging Economies

Experiences documented in emerging economies reveal specific structural limitations linked to patterns of circular water economy implementation. The literature identifies persistent gaps in cross-sectoral coordination, sustainable financing, and technological innovation that operate as systemic constraints [

36,

37].

Peruvian contexts exhibit regulatory fragmentation characterised by multiple agencies with overlapping competences, generating uncertainty about technical requirements and approval procedures[

38] . This institutional configuration creates vicious circles where the absence of institutional technical expertise is associated with limitations in organisational absorption capacity, while the lack of documented successful experiences is related to reduced incentives for investment in capabilities, perpetuating dependence on conventional technologies [

39,

40].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study adopted an 'organisational adoption' perspective that examines the level of technological integration achieved by organisations at a specific point in time, recognising that technological adoption is a dynamic process where this design captures associations between facilitating factors and observed adoption states. The temporal limitation inherent in the cross-sectional design prevents the examination of adoption trajectories, transitions between stages, or causal temporal sequences, constituting a fundamental methodological restriction that conditions all inferences derived from this study.

The cross-sectional nature of the study allowed for data collection at a specific point in time, while the analytical approach facilitated the examination of relationships between organisational, psychosocial, and institutional variables associated with the implementation of water reuse technologies [

41,

42].

The methodological strategy was based on structural equation modelling (SEM), specifically using the partial least squares technique (PLS-SEM), which is particularly appropriate for testing hypotheses with direct and indirect relationships in complex models that include latent variables [

42]. This methodological approach allows for the simultaneous evaluation of the measurement model and the structural model, providing evidence on the validity of the theoretical constructs and the proposed causal relationships [

43].

2.2. Participants and Sampling

The target population consisted of key organisational decision-makers in water resource management, including: managers and executives from industrial, service and construction companies; sustainability and environmental managers; operations and maintenance managers; municipal public service officials; wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) managers; and urban environmental project coordinators in the regions of Lima, Trujillo and Cajamarca, Peru.

Non-probabilistic convenience and quota sampling was used, considering the specificity of the target population and the limitations of access to high-level organisational decision-makers [

44,

45]. This sampling approach has proven effective in studies of sustainability and organisational innovation where specific expertise is required from participants [

46].

Rationality of the Design Adopted: Sampling targeting specialised organisational decision-makers responds to the technical and strategic nature of decisions on the adoption of circular water economy technologies, which require specific expertise that is inaccessible in general probabilistic samples. This methodological approach, established in organisational research on environmental innovation, prioritises depth of expertise over population representativeness, constituting a deliberate methodological decision that optimises internal validity at the expense of external generalisation.

The final sample size was n = 150 participants, exceeding the minimum requirements for PLS-SEM, which establish between 5 and 10 observations per estimated parameter [

42]. Considering that the model includes 8 constructs with 25 indicators, the sample size achieved guarantees the stability of the results and adequate statistical power to detect significant effects.

2.3. Instrument

A structured 5-point Likert-type questionnaire (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) was developed, organised into eight theoretical constructs: Organisational Resources (OR, 3 items), Organisational Culture (OC, 3 items), Individual Attitudes (IA, 4 items), Knowledge (KN, 2 items), External Pressure (EP, 4 items), Institutional Framework (IF, 5 items), Implementation (IM, 4 items) and Results (RE, 4 items).

During confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), three items were eliminated for having factor loadings below 0.70: one item from the Individual Attitudes construct, one item from the Knowledge construct, and one item from the Institutional Framework construct. This elimination improved the composite reliability of each respective construct.

2.4. Procedure and Data Analysis

Data collection was carried out between January and May 2025 using a mixed approach that included the use of digital forms and in-person visits to public and private universities, as well as industrial and urban service organisations in the three regions under study. Quality control protocols were implemented to minimise response bias, including item randomisation and internal consistency checks.

The data underwent a cleaning process that included identifying and handling missing values (<5% of the total), detecting multivariate outliers using Mahalanobis distance, and verifying multivariate normality assumptions. Complementary analyses of multicollinearity were performed using variance inflation factors (VIF), confirming values below 4.0 for all constructs. Additionally, correlations between residuals were examined to detect systematic patterns that could indicate omitted variables, without identifying substantial problems beyond the reported HTMT correlations. Subsequently, descriptive analyses were performed to characterise the sample and examine the distributions of the variables.

The main analysis used the PLS-SEM technique implemented in SmartPLS 4.0, including: (1) evaluation of the measurement model using confirmatory factor analysis, convergent and discriminant validity; (2) assessment of the structural model using path coefficients, statistical significance, and coefficients of determination (R²); and (3) bootstrap procedure with 5,000 subsamples for confidence interval estimation. Goodness-of-fit criteria included SRMR < 0.08, NFI > 0.90, and χ²/df between 1 and 3 [

47,

48].

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The research complied with the fundamental ethical principles for studies involving human subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, guaranteeing the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses. The data were coded to protect the identity of the participants and organisations. The study was classified as minimal risk as it did not involve invasive procedures or the handling of sensitive information, obtaining exemption from formal ethical review in accordance with current institutional regulations.

To test the research hypotheses, an empirical evaluation was carried out using a survey of organisational decision-makers [

49], highlighting that SEM modelling allowed for the evaluation of complex associations between organisational, psychosocial and institutional factors related to the implementation of circular water economy technologies.

Direct Hypotheses:

H1. Organisational Resources (OR) are positively associated with Implementation (IM) of water reuse technologies.

H2. Organisational Culture (OC) is positively associated with Implementation (IM) of water reuse technologies.

H3. Individual Attitudes (IA) are positively associated with Implementation (IM) of water reuse technologies.

H4. Knowledge (KN) is positively associated with Implementation (IM) of water reuse technologies.

H5. External Pressure (EP) is positively associated with Implementation (IM) of water reuse technologies.

H6. Institutional Framework (IF) is positively associated with Implementation (IM) of water reuse technologies.

H7. Implementation (IM) is positively associated with Results (RE) of water reuse technologies.

2.6. Hypotheses of Indirect Associations

H8. The association between Organisational Resources (OR) and Results (RE) operates through Implementation (IM).

H9. The association between Organisational Culture (OC) and Results (RE) operates through Implementation (IM).

H10. The association between Individual Attitudes (IA) and Results (RE) operates through Implementation (IM).

H11. The association between Knowledge (KN) and Results (RE) operates through Implementation (IM).

H12. The association between External Pressure (EP) and Results (RE) operates through Implementation (IM).

H13. The association between Institutional Framework (IF) and Results (RE) operates through Implementation (IM).

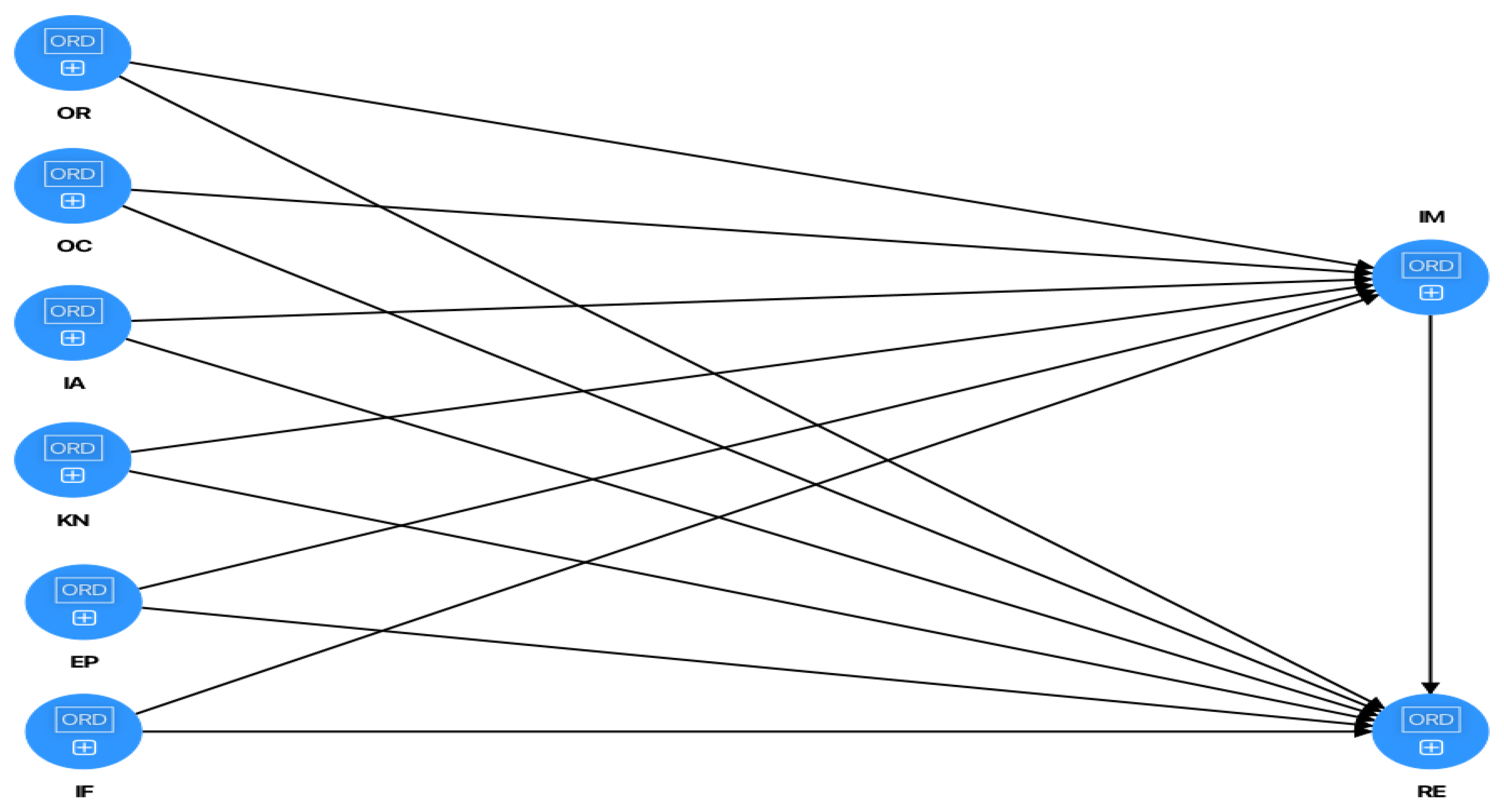

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

3. Results

This study used the partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) approach, which allowed for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to be performed to ensure the convergent validity of the measurement model.

Table 1 presents the factor loadings for each item, which, according to the criteria [

50] reach values above 0.70, considered adequate to confirm the representativeness of the indicators in their respective constructs.

Likewise, all constructs evaluated show average extracted variance (AVE) values that exceed the threshold of 0.50, ensuring that each construct explains more than 50% of the variance of its indicators [

42]. These results confirm that the measurement model has adequate convergent validity and complies with the methodological standards established in the specialised literature.

Table 2.

Factor loadings of the measurement model.

Table 2.

Factor loadings of the measurement model.

| Construct |

Item |

Description |

Load |

STDEV |

p-value |

| EP |

EP1 |

In my sector, it is increasingly common and expected to adopt reuse technologies. |

0.840 |

0.026 |

0.000 |

| |

EP2 |

There is a growing social expectation that we adopt circular economy practices. |

0.880 |

0.021 |

0.000 |

| |

EP3 |

In my sector, there is growing regulatory pressure to implement sustainable practices. |

0.787 |

0.050 |

0.000 |

| |

EP4 |

Industry standards are progressively demanding greater efficiency in water use. |

0.827 |

0.033 |

0.000 |

| IA |

IA1 |

I believe that reuse technologies represent essential innovations for the future. |

0.864 |

0.034 |

0.000 |

| |

IA2 |

I am genuinely motivated to lead the adoption of innovative environmental technologies. |

0.879 |

0.034 |

0.000 |

| |

IA3 |

The economic and environmental benefits far outweigh the potential risks. |

0.865 |

0.028 |

0.000 |

| |

IA4 |

I have complete confidence in the safety and effectiveness of modern reuse systems |

0.904 |

0.018 |

0.000 |

| IF |

IF1 |

Current regulations effectively facilitate the implementation of reuse technologies. |

0.820 |

0.037 |

0.000 |

| |

IF2 |

The legal requirements for water reuse are clear, consistent and achievable |

0.815 |

0.035 |

0.000 |

| |

IF3 |

There are attractive government financial incentives to adopt reuse technologies. |

0.870 |

0.022 |

0.000 |

| |

IF4 |

Public policies effectively and consistently promote the circular water economy. |

0.849 |

0.025 |

0.000 |

| |

IF5 |

Public institutions provide competent and timely technical advice |

0.808 |

0.034 |

0.000 |

| IM |

IM1 |

Our organisation has successfully implemented functional water reuse systems. |

0.892 |

0.018 |

0.000 |

| |

IM2 |

We regularly use advanced treatment technologies for internal reuse. |

0.905 |

0.018 |

0.000 |

| |

IM3 |

We have concrete, funded strategic plans to expand reuse. |

0.894 |

0.018 |

0.000 |

| |

IM4 |

We systematically monitor and optimise our reuse systems |

0.892 |

0.022 |

0.000 |

| KN |

KN1 |

I have solid knowledge of the technologies available for water reuse. |

0.944 |

0.014 |

0.000 |

| |

KN2 |

I clearly understand the technical and economic benefits of these technologies. |

0.943 |

0.012 |

0.000 |

| OC |

OC1 |

Organisational leaders actively communicate the importance of the circular water economy |

0.896 |

0.018 |

0.000 |

| |

OC2 |

There is a well-established culture of environmental responsibility in our organisation |

0.914 |

0.017 |

0.000 |

| |

OC3 |

Organisational values explicitly include sustainability and water conservation. |

0.898 |

0.023 |

0.000 |

| OR |

OR1 |

Our organisation has adequate financial resources to invest in water reuse technologies. |

0.912 |

0.019 |

0.000 |

| |

OR2 |

The costs of implementing reuse technologies are within our budgetary means. |

0.938 |

0.013 |

0.000 |

| |

OR3 |

Senior management demonstrates visible commitment to the implementation of water reuse technologies. |

0.872 |

0.025 |

0.000 |

| RE |

RE1 |

The systems implemented consistently exceed performance expectations. |

0.895 |

0.017 |

0.000 |

| |

RE2 |

We have achieved quantifiable and significant reductions in fresh water consumption. |

0.910 |

0.021 |

0.000 |

| |

RE3 |

The implementation has generated measurable and substantial economic savings. |

0.894 |

0.026 |

0.000 |

| |

RE4 |

Our stakeholders recognise and value our achievements in the circular water economy. |

0.906 |

0.019 |

0.000 |

Table 3.

Convergent validity by construct.

Table 3.

Convergent validity by construct.

| Construct |

Code |

Full name |

AVE |

Interpretation |

| EP |

External Pressure |

External Pressure |

0.696 |

Valid (>0.50) |

| IA |

Individual Attitudes |

Individual Attitudes |

0.771 |

Valid (>0.50) |

| IF |

Institutional Framework |

Institutional Framework |

0.693 |

Valid (>0.50) |

| IM |

Implementation |

Implementation |

0.803 |

Valid (>0.50) |

| KN |

Knowledge |

Knowledge |

0.890 |

Valid (>0.50) |

| OC |

Organisational Culture |

Organisational Culture |

0.815 |

Valid (>0.50) |

| OR |

Organisational Resources |

Organisational Resources |

0.824 |

Valid (>0.50) |

| RE |

Results |

Results |

0.812 |

Valid (>0.50) |

Table 4 reports the reliability and discriminant validity analyses of the constructs included in the model. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach's alpha (α) and composite reliability (rho_a and rho_c). Values above 0.70 are considered acceptable [

42,

52]; in this study, all constructs exceeded this threshold, confirming adequate internal consistency and robustness of the measurement scales.

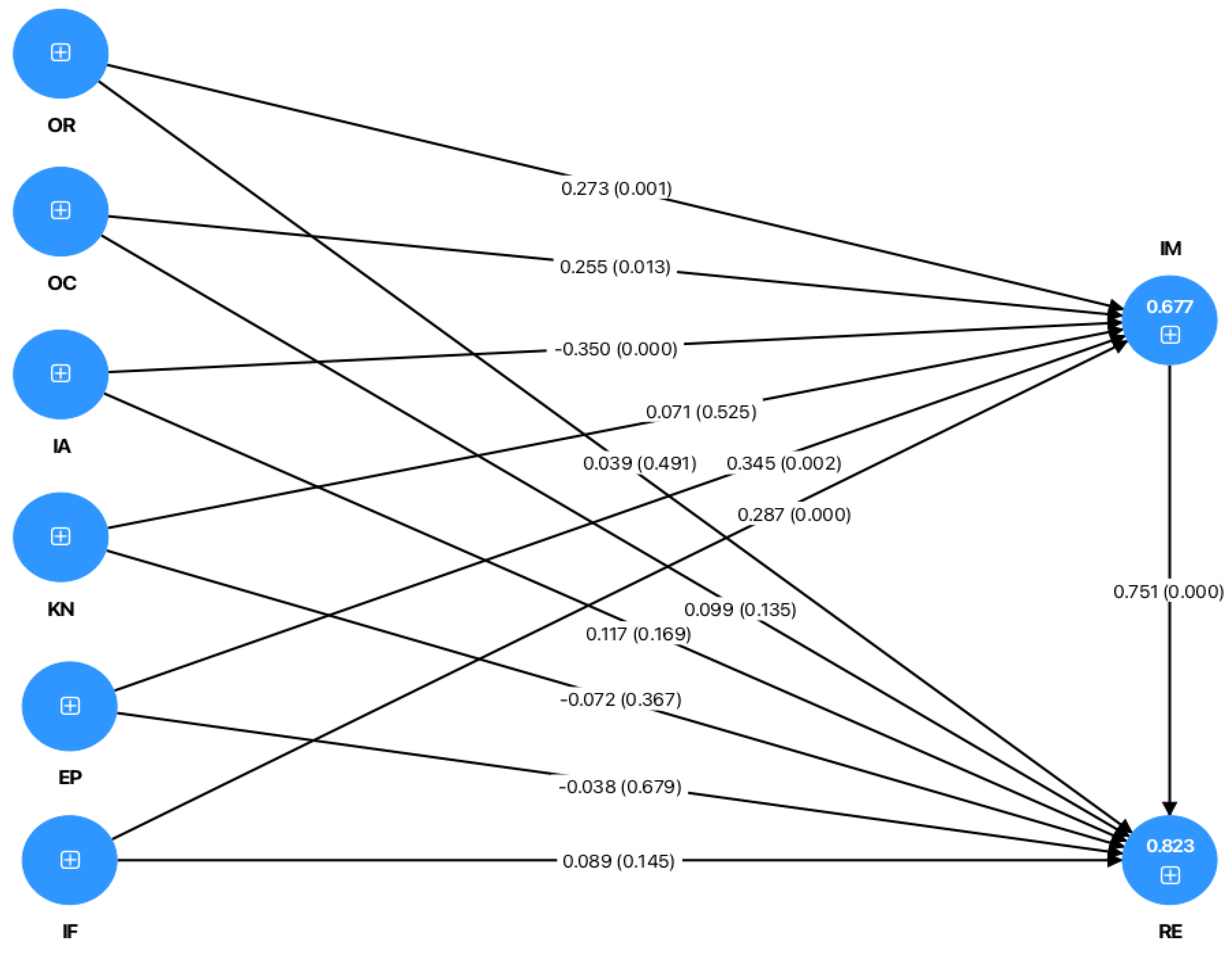

In relation to the coefficient of determination (R²), the results show that the Implementation (IM) construct reaches a value of 0.677, indicating that the OR, OC, IA, KN, EP and IF constructs explain 67.7% of its variation. Similarly, the Results (RE) construct has an R² of 0.823, which means that the OR, OC, IA, KN, EP, IF and IM constructs explain 82.3% of the variance in this factor. These values reflect a high level of explanatory power of the structural model, which supports its empirical relevance.

Discriminant validity was assessed solely using the HTMT criterion, whose values remained below the threshold of 0.85 [

53]. This confirms that the constructs are conceptually distinct from one another and that the instrument has the required discriminant validity.

Discriminant validity is confirmed by two complementary criteria. First, the Fornell-Larcker criterion shows that all √AVE (diagonal) values exceed the correlations between constructs, confirming that each construct shares more variance with its indicators than with other constructs. Second, the HTMT analysis reveals that two values (EP-IA: 0.880; EP-IF: 0.860) exceed the conservative threshold of 0.85 but remain below the liberal limit of 0.90. This high correlation between external pressure and individual attitudes is conceptually expected, as environmental pressures naturally influence individual perceptions, without compromising the discriminant validity of the model.

The HTMT values between EP-IA (0.880) and EP-IF (0.860) exceed the conservative threshold of 0.85, although they remain below the liberal limit of 0.90 suggested by Henseler et al. (2015). This high correlation may reflect the interrelated nature of external and institutional pressures in contexts where regulatory frameworks simultaneously influence individual perceptions and organisational expectations. Additional collinearity analyses using VIF confirm values below 3.5 for all constructs, suggesting that the correlation, although high, does not compromise the model estimation.

Table 5 shows the main indicators of fit for the measurement model. First, the SRMR obtained a value of 0.069, below the threshold of 0.85, which indicates an adequate fit for the model. Likewise, the χ²/df index reached a value of 1.499, falling within the recommended range of 1 to 3, which supports the acceptability of the model according t[

48] . Similarly, the NFI presented a value of 0.942, higher than the threshold of 0.90 suggested by the same authors, confirming a satisfactory fit. The values obtained in d_ULS (2.066) and d_G (1.278), although they do not have an explicit comparison criterion in the table, complement the evidence of good model performance. Taken together, these results allow us to conclude that the measurement model achieves acceptable levels of fit consistent with the theoretical parameters proposed in the specialised literature.

Table 6 and

Figure 2 show the direct associations identified in the structural model. Hypothesis 5 (H5) was confirmed, showing a significant positive association between External Pressure (EP) and Implementation (IM) (β = 0.345; p = 0.002), suggesting that regulatory and social factors are linked to a higher probability of adopting water reuse technologies.

Hypothesis 3 (H3) was significant, showing a negative association between Individual Attitudes (IA) and Implementation (IM) (β = -0.350; p < 0.001). This finding indicates that, contrary to expectations, individual perceptions are not positively associated with implementation, but may be linked to resistance in the adoption process.

The negative association between Individual Attitudes and Implementation (H3: β = -0.350; p < 0.001) is a counterintuitive finding that requires theoretical explanation. This result can be interpreted from the perspective of the "attitude-behaviour gap" documented in environmental psychology literature, where favourable attitudes do not automatically translate into behaviours due to structural barriers. In organisational contexts, individual attitudes may be associated with resistance when they are not aligned with organisational capabilities or institutional pressures, suggesting that structural factors (external pressure, institutional framework) show stronger associations than individual perceptions with the successful implementation of water reuse technologies.

Hypothesis 6 (H6) was also confirmed, as the Institutional Framework (IF) shows a positive and statistically significant association with Implementation (IM) (β = 0.287; p < 0.001), reinforcing the importance of regulatory clarity and institutional incentives in the adoption of sustainable practices.

Hypothesis 7 (H7) showed the strongest association in the model, demonstrating that Implementation (IM) is significantly associated with Results (RE) (β = 0.751; p < 0.001). This result highlights that the implementation of reuse technologies is linked to tangible benefits, such as resource savings and stakeholder recognition.

Hypothesis 2 (H2) showed a positive and significant association between Organisational Culture (OC) and Implementation (IM) (β = 0.255; p = 0.013), confirming that values and environmental responsibility within the organisation are favourably associated with the adoption of reuse technologies.

In contrast, the hypotheses related to direct associations of Knowledge (KN), as well as the links between EP, IA, IF, OC, and OR with Outcomes (RE), did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05) and were therefore rejected.

Hypothesis 1 (H1) was confirmed, showing that Organisational Resources (OR) have a positive and significant association with Implementation (IM) (β = 0.273; p = 0.001), confirming that the availability of financial resources and senior management commitment are linked to the adoption of water reuse technologies.

Table 7 presents the indirect associations of the structural model through the Implementation (IM) variable. The results show that Hypothesis 12 (H12) was confirmed, demonstrating that External Pressure (EP) has a positive and significant association with Results (RE) through Implementation (β = 0.259; p = 0.003). This indicates that regulatory and social pressure is linked to improvements in outcomes when the organisation implements reuse technologies.

Hypothesis 10 (H10) was also significant, showing a negative association between Individual Attitudes (IA) and Outcomes (RE) operating through Implementation (β = -0.263; p < 0.001). This finding suggests that individual attitudes are negatively associated with organisational achievements through their relationship with implementation.

Hypothesis 13 (H13) was accepted, confirming that the Institutional Framework (IF) is positively associated with Results (RE) through Implementation (β = 0.216; p < 0.001). This result highlights the importance of having regulatory and public policy support linked to tangible benefits.

Hypothesis 9 (H9) also obtained empirical support, showing that Organisational Culture (OC) has a positive and significant association with Outcomes (RE) operating through Implementation (β = 0.191; p = 0.020), confirming the association of organisational environmental values with the achievement of outcomes.

Hypothesis 11 (H11) was rejected, as Knowledge (KN) did not show a significant indirect association with outcomes (β = 0.054; p = 0.528).

Hypothesis 8 (H8) was accepted, showing that Organisational Resources (OR) are positively associated with Outcomes (O) through Implementation (β = 0.205; p = 0.002). This suggests that the availability of financial and technical resources is linked to organisational benefits when it materialises in effective implementation processes.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Negative Association of Individual Attitudes with Technological Implementation

The most counterintuitive finding of this study lies in the significant negative effect of individual attitudes on the implementation of water reuse technologies (β = -0.350; p < 0.001). This result challenges fundamental theoretical assumptions that have traditionally positioned attitudes as positively associated with technology adoption. In this sense, our findings align with emerging evidence on the "attitude-behaviour gap" in organisational contexts, where favourable individual perceptions do not automatically translate into successful implementations due to structural constraints and organisational power dynamics.

Theoretical Interpretation of the Paradoxical Effect of Attitudes: The negative association identified is supported by emerging literature on 'implementation gaps', where favourable attitudes disconnected from structural capacities generate cycles of frustration and resistance. In organisational contexts with limited resources, positive individual attitudes can operate as signals of unrealistic expectations which, when confronted with budgetary or institutional constraints, transform into resistance towards initiatives perceived as unachievable.

4.2. The Centrality of Implementation as a Total Mediating Variable

A key finding of the structural model is that all associations with outcomes are channelled exclusively through the implementation variable, forming a pattern of total mediation that theoretically validates the critical importance of translating capabilities into concrete actions. This result corroborates systemic perspectives on environmental innovation that emphasise the inadequacy of resources, regulatory frameworks or organisational cultures when they do not materialise in specific operational practices.

The observed mediation pattern, where associations with outcomes are mainly channelled through implementation, may reflect the sequential nature of technology adoption processes, where resources, institutional frameworks and psychosocial factors need to be translated into concrete actions before generating measurable benefits. However, the absence of significant direct associations with outcomes may also indicate limitations in the model specification or the need for additional mediating variables not considered in this study.

4.3. Hierarchy of Structural Factors and Identified Association Patterns

The results reveal a clear hierarchy of determining factors, with external pressure emerging as the main driver (β = 0.345), followed by the institutional framework (β = 0.287), organisational resources (β = 0.273) and organisational culture (β = 0.255). This causal configuration validates institutionalist perspectives that position regulatory and social pressures as fundamental catalysts for organisational environmental innovation.

The primacy of external pressure is consistent with theoretical approaches to institutional configurations and environmental governance developed in the conceptual framework. In contrast to theoretical frameworks that privilege internal factors such as organisational culture or leadership, our findings suggest that in Latin American contexts, exogenous forces constitute more powerful mechanisms of change than endogenous capacities, corroborating the critical relevance of regulatory frameworks in the adoption of circular practices [

54].

In particular, the significance of the institutional framework as the second most relevant factor confirms the limitations of institutional fragmentation and regulatory gaps as systemic barriers to the implementation of the circular economy [

11]. This hierarchy implies that public policy interventions should prioritise the strengthening of clear regulatory frameworks and economic incentive systems over technical training or cultural awareness programmes.

4.4. The Negative Association of Individual Attitudes with Technological Implementation

Contrary to theoretical expectations derived from the conceptual framework on psychosocial dimensions, technical knowledge did not show significant associations with implementation (β = 0.071; p = 0.525). This finding challenges assumptions implicit in the literature on environmental management that position technical expertise as a fundamental prerequisite for the adoption of complex technologies.

The absence of significant associations with specialised technical knowledge may reflect a 'ceiling effect' where the restricted distribution of expertise in circular water economy in the context studied limits the statistical variability necessary to detect effects. Alternatively, it may indicate that in resource-constrained contexts, technical knowledge operates as an enabling prerequisite rather than a differentiating driver.

On the other hand, the insignificance of knowledge may reflect specificities of the Peruvian context, where access to specialised technical expertise in circular water economy remains limited, generating restricted distributions that reduce the statistical variability necessary to detect significant effects. Additionally, it is plausible that in contexts of limited resources, organisations prioritise the implementation of proven and accessible technologies over technically sophisticated solutions that require specialised expertise.

4.5. Theoretical and Methodological Contributions to the Field of Circular Economy

This study constitutes the first application of multidimensional SEM modelling to analyse factors conditioning the implementation of the circular water economy in Latin American contexts, overcoming the limitations of one-dimensional approaches identified in the theoretical framework. The model's high explanatory power (R² = 67.7% for implementation; R² = 82.3% for results) demonstrates the theoretical relevance of integrative frameworks that recognise the multi-causal nature of organisational environmental innovation phenomena.

Consistent with the conceptual developments presented, the findings validate the need for systemic approaches that transcend simplistic dichotomies between technical and social factors, revealing complex configurations where organisational, psychosocial, and institutional variables interact in a non-linear manner to produce differentiated outcomes. In contrast to previous studies that have examined isolated factors, this model demonstrates that successful implementation requires specific alignments between multiple levels of analysis, confirming the limitations of fragmented approaches [

7,

55].

4.6. Implications for Public Policy and Organisational Management

The findings have direct implications for the design of public policies aimed at accelerating the transition to a circular water economy in developing countries. The centrality of external pressure and the institutional framework suggests that government interventions should prioritise the strengthening of clear regulatory frameworks, attractive economic incentive systems and effective enforcement mechanisms over technical training or environmental awareness programmes.

In line with these findings, organisational strategies should focus on developing robust implementation capacities that enable available resources and institutional support to be translated into functional water reuse systems. This implies priority investments in infrastructure, monitoring systems and specialised technical equipment, complemented by organisational cultures that value sustainability as a strategic competitive advantage.

The pattern of indirect associations identified suggests that organisations that manage to develop effective implementation capacities reap significant benefits regardless of their initial limitations in terms of resources or technical knowledge, offering alternative routes for organisations with budgetary constraints that seek to participate in circular water economy initiatives. The pattern of indirect associations identified suggests that all organisational, psychosocial and institutional factors are linked to outcomes through their relationship with implementation.

4.7. Specific Contextual Configuration

The patterns of association identified emerge within a specific institutional, economic and cultural configuration of the Peruvian context studied, characterised by developing regulatory frameworks, limited institutional capacities and asymmetries in access to advanced technologies. This contextual configuration fundamentally conditions the dynamics of technological adoption observed, suggesting that the primacy of external factors over internal factors may reflect specific characteristics of contexts where state institutional capacity operates as a critical limiting factor.

4.8. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study has fundamental methodological limitations that condition the interpretation of findings. The cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of temporal directionality and definitive causal relationships, while non-probabilistic sampling restricts generalisation beyond the specific organisations studied, particularly considering the institutional heterogeneity that characterises Peruvian contexts.

Critical Contextual Delimitation: The sample is limited to three Peruvian regions selected for operational convenience, not for national or regional statistical representativeness. Lima (urban water stress), Trujillo (export-oriented agribusiness) and Cajamarca (mining with socio-environmental conflicts) constitute specific contexts whose particular hydroeconomic, institutional and cultural characteristics fundamentally condition the patterns of association identified. Extrapolation to other national, regional or sectoral contexts lacks empirical basis and would constitute a methodologically unjustified overgeneralisation.

The exceptional coefficients of determination (R² = 67.7% for implementation; R² = 82.3% for outcomes) constitute a statistical anomaly in organisational research that may reflect: (1) successful specification of determining factors, (2) undetected residual multicollinearity, (3) common method bias derived from the single survey design, or (4) model overfitting. High HTMT correlations between constructs (EP-IA: 0.880; EP-IF: 0.860) suggest conceptual redundancy that compromises discriminant validity, indicating a need for theoretical refinement. The total absence of direct associations with outcomes constitutes a methodologically suspect pattern of complete mediation that may indicate omission of relevant variables or incorrect model specification. These exceptionally high values require cautious interpretation and replication in independent samples before confirming the robustness of the model.

Future research should employ: (1) longitudinal designs that allow for legitimate causal inference, (2) comparative studies across diverse institutional contexts, (3) mixed methodological approaches that integrate quantitative analysis with organisational case studies, (4) cross-validation with independent samples, and (5) inclusion of additional mediating variables (organisational absorptive capacity, resistance to change) and contextual moderating effects to develop more sophisticated theories on circular water economy in emerging economies.

5. Conclusions

It is important to note that the association patterns identified emerge specifically within the context of three Peruvian regions (Lima, Trujillo, and Cajamarca) with particular hydroeconomic, institutional, and cultural characteristics that fundamentally condition the dynamics observed. Lima exhibits characteristics of urban water stress, Trujillo corresponds to an agro-industrial export context, and Cajamarca reflects a mining environment with socio-environmental tensions. This specific contextual configuration limits direct extrapolation to other national, regional or sectoral contexts, which lacks empirical basis without additional validation. Replication through longitudinal designs in diverse institutional contexts is a critical priority for validating the transferability of these findings.

Within these contextual limitations, this study suggests that in the Peruvian regions studied, the adoption of circular water economy technologies operates through complex configurations that challenge traditional theoretical frameworks developed in more consolidated institutional contexts. The findings reveal that external structural factors are more strongly associated with technological adoption than internal organisational capacities. The empirical hierarchy, in which external pressure outweighs organisational resources, institutional frameworks and organisational culture, contradicts decades of research that privileges endogenous factors, suggesting that, specifically in contexts of limited institutional development such as those studied, organisations respond primarily to external incentives. This configuration may reflect particular characteristics of emerging economies where state institutional capacity operates as a critical limiting factor.

The total mediation identified reveals that all organisational, psychosocial and institutional factors need to be translated into actions and implementations in order to generate measurable results. This configuration theoretically validates that resources, regulatory frameworks or organisational cultures are irrelevant if they do not materialise into functional operating systems, positioning implementation as a critical link between latent capabilities and observable results.

The negative association between favourable individual attitudes and implementation is the most disruptive finding, challenging fundamental assumptions in environmental psychology. This result suggests that positive attitudes disconnected from structural capabilities are associated with implementation resistance, revealing a pattern where favourable perceptions can paradoxically operate as barriers when not backed by adequate organisational support.

Methodologically, this research sets critical precedents as the first application of multidimensional SEM to examine the circular water economy by integrating organisational, psychosocial, and institutional levels. Its exceptional explanatory power exceeds typical standards in organisational research, demonstrating the potential of integrative approaches that transcend disciplinary fragmentation.

The findings suggest possible directions for public policy in contexts similar to the one studied. The empirical primacy of external pressure indicates that more effective government interventions operate through regulations that generate clear sectoral expectations rather than training programmes. For organisations, total mediation indicates that investments in implementation capabilities are the most direct route to benefits, regardless of initial constraints.

This study provides pioneering empirical evidence on factor configurations associated with technology adoption in contexts characterised by specific institutional constraints, establishing theoretical foundations for advancing towards a more sophisticated understanding of organisational transitions towards sustainability in developing country contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.L.R. and D.J.A.C.; methodology, G.S.L.R. and D.J.A.C.; software, F.S.M.G. and D.A.L.A.; validation, L.A.V.Z. and P.V.Z.; formal analysis, F.S.M.G. and P.V.Z.; investigation, G.S.L.R., R.L.C. and D.J.A.C.; resources, L.A.V.Z. and R.L.R.; data curation, F.S.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.L.A. and E.O.L.L.; writing—review and editing, E.O.L.L.; visualization, L.A.V.Z. and R.L.R.; supervision, D.A.L.A.; project administration, P.V.Z. and E.O.L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Bank Wastewater? : From Waste to Resource in a Circular Economy Context : Latin America and the Caribbean Region. Available online: https://documentos.bancomundial.org/es/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/453201567149470699 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Progress on Wastewater Treatment: Global Status and Acceleration Needs for SDG Indicator 6.3.1. UNEP. 2021.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Making Dispute Resolution More Effective – MAP Peer Review Report, Sweden (Stage 1). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/making-dispute-resolution-more-effective-map-peer-review-report-sweden-stage-1_9789264285736-en.html (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Chowdhury, S.; Dey, P.K.; Rodríguez-Espíndola, O.; Parkes, G.; Tuyet, N.T.A.; Long, D.D.; Ha, T.P. Impact of Organisational Factors on the Circular Economy Practices and Sustainable Performance of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Vietnam. Journal of Business Research 2022, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kek, H.Y.; Tan, H.; Othman, M.H.D.; Lee, C.T.; Ahmad, F.B.J.; Ismail, N.D.; Nyakuma, B.B.; Lee, K.Q.; Wong, K.Y. Transforming Pollution into Solutions: A Bibliometric Analysis and Sustainable Strategies for Reducing Indoor Microplastics. Environmental Research 2024, 252, 118928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.Z.; Wu, Y.; Liao, Z. Do Circular Economy Practices Matter for Financial Growth? An Empirical Study in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 370, 133255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Raut, R.D.; Kumar, M.; Zhang, C.; Gokhale, R.S. Does the Circular Economy Transition Aid to Carbon Neutrality? Examining Net-Zero Policy and Stakeholder Impact from the Environmental Justice Viewpoint. Journal of Cleaner Production 2025, 491, 144851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Hassan, S.; Hossain, S.; Ahmed, T.; Karmaker, C.L.; Bari, A.B.M.M. Exploring the Influence of Circular Economy on Big Data Analytics and Supply Chain Resilience Nexus: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Green Technologies and Sustainability 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, G.; Supino, S.; Grimaldi, M.; Troisi, O. Exploring the Political-Institutional Perspective of Sustainable Consumer Behaviour within the Circular Economy: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach from Nudge Theory. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 2025, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharayat, T.S.; Gupta, H. Assessment of Circular Economy Strategies for Climate Change Mitigation: A Forecast on India’s Path to a Net Zero Future. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2025, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seles, B.M.R.P.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Latan, H.; Mascarenhas, J. ‘Breaking the Mold’: Circular Economy Success in a Challenging Institutional Context. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guimarães, J.C.F.; Severo, E.A.; Klein, L.L.; Dorion, E.C.H.; Lazzari, F. Antecedents of Sustainable Consumption of Remanufactured Products: A Circular Economy Experiment in the Brazilian Context. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinkóczi, T.; Heimné Rácz, É.; Koltai, J.P. Exploratory Analysis of Zero Waste Theory to Examine Consumer Perceptions of Sustainability: A Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modelling (CB-SEM). Cleaner Waste Systems 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shen, N.; Chen, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, S. Chapter 2 - Water-Stable Metal–Organic Framework–Based Nanomaterials for Removal of Heavy Metal Ions and Radionuclides. In Emerging Nanomaterials for Recovery of Toxic and Radioactive Metal Ions from Environmental Media; Wang, X., Ed.; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 49–126, ISBN 978-0-323-85484-9.

- Das, P.P.; Mondal, P. 14 - Membrane-Assisted Potable Water Reuses Applications: Benefits and Drawbacks. In Resource Recovery in Drinking Water Treatment; Sillanpää, M., Khadir, A., Gurung, K., Eds.; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 289–309, ISBN 978-0-323-99344-9.

- Mannina, G.; Pandey, A. Boosting the Transition to Circular Economy in the Water Sector: Insights from EU Demonstration Case Studies; First edition.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2025; ISBN 978-0-443-30258-9. [Google Scholar]

- Adewuyi, S.O.; Anani, A.; Luxbacher, K. Advancing Sustainable and Circular Mining through Solid-Liquid Recovery of Mine Tailings. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2024, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeleru, O.O.; Sadare, O.O.; Idris, A.O.; Pandey, S.; Olubambi, P.A. Chapter 1 - Introduction to Smart Nanomaterials for Environmental Remediation. In Smart Nanomaterials for Environmental Applications; Ayeleru, O.O., Idris, A.O., Pandey, S., Olubambi, P.A., Eds.; Micro and Nano Technologies; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 3–28, ISBN 978-0-443-21794-4.

- Khizar, H.M.; Iqbal, M.J.; Khalid, J.; Adomako, S. Addressing the Conceptualisation and Measurement Challenges of Sustainability Orientation: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Business Research 2022, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Balaram, V.; Santosh, M.; Satyanarayanan, M.; Srinivas, N.; Gupta, H. Lithium: A Review of Applications, Occurrence, Exploration, Extraction, Recycling, Analysis, and Environmental Impact. Geoscience Frontiers 2024, 15, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Vigile, M.F.; Galiano, F.; Figoli, A. Chapter 2 - Green Solvents for Membrane Fabrication. In Green Membrane Technologies towards Environmental Sustainability; Dumée, L.F., Sadrzadeh, M., Shirazi, M.M.A., Eds.; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 9–44, ISBN 978-0-323-95165-4.

- Segovia-Hernández, J.G.; Hernández, S.; Cossío-Vargas, E.; Sánchez-Ramírez, E. Tackling Sustainability Challenges in Latin America and the Caribbean from the Chemical Engineering Perspective: A Literature Review in the Last 25 Years. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2022, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, A.; Elías-Peñafiel, C.; Encina-Zelada, C.R.; Anticona, M.; Ramos-Escudero, F. Circular Bioeconomy for Cocoa By-Product Industry: Development of Whey Protein-Cocoa Bean Shell Concentrate Particles Obtained by Spray-Drying and Freeze-Drying for Commercial Applications. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2024, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O. Determinants of Green Behaviour (Revisited): A Comparative Study. Resources, Conservation & Recycling Advances 2024, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, A.; Kumar, A. 19 - Functionalised Polymer Nanocomposites for Environmental Remediation. In Advances in Functionalised Polymer Nanocomposites; Patel, G., Deshmukh, K., Hussain, C.M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Composites Science and Engineering; Woodhead Publishing, 2024; pp. 747–784, ISBN 978-0-443-18860-2.

- Hidalgo-Crespo, J.; Amaya-Rivas, J.L. Citizens’ pro-Environmental Behaviours for Waste Reduction Using an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour in Guayas Province. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, S.M.; Zolkepli, I.A.; Ahmad Rizal, A.R.; Tariq, R.; Mannan, S.; Ramayah, T. Paving the Way to Paddy Food Security: A Multigroup Analysis of Agricultural Education on Circular Economy Adoption. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Dixit, R.; Sharma, R.K. Chapter 7 - Remediation of Heavy Metals with Nanomaterials. In Separation Science and Technology; Ahuja, S., Ed.; Separations of Water Pollutants with Nanotechnology; Academic Press, 2022; Vol. 15, pp. 97–138.

- Jave-Chire, M.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Guevara-Zavaleta, V. Footwear Industry’s Journey through Green Marketing Mix, Brand Value and Sustainability. Sustainable Futures 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Singh, R.; Arfin, T.; Neeti, K. Fluoride Contamination, Consequences and Removal Techniques in Water: A Review. Environ. Sci.: Adv. 2022, 1, 620–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakkel, M. Chapter 8 - Efficient Adsorbent Based on Pomegranate Peel for Pollutants Removal from Aqueous Solution. In Sustainable Applications of Pomegranate Peels; Jeguirim, M., Khiari, B., Eds.; Academic Press, 2025; pp. 151–190, ISBN 978-0-443-22390-7.

- Aragaw, T.A.; Ayalew, A.A. Chapter 10 - Application of Metal-Based Nanoparticles for Metal Removal for Treatments of Wastewater -- a Review. In Emerging Techniques for Treatment of Toxic Metals from Wastewater; Ahmad, A., Kumar, R., Jawaid, M., Eds.; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 183–231, ISBN 978-0-12-822880-7.

- Holley, E.A.; Fahle, L.; Malone, A.; Zaronikola, N.; Nelson, P.P.; Erik Spiller, D. U.S. Industry Practices and Attitudes towards Reprocessing Mine Tailings for Metal Recovery. Resources Policy 2025, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltelli, M.-B.; Morganti, P.; Lazzeri, A. Chapter 20 - Sustainability Assessment, Environmental Impact, and Recycling Strategies of Biodegradable Polymer Nanocomposites. In Biodegradable and Biocompatible Polymer Nanocomposites; Deshmukh, K., Pandey, M., Eds.; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 699–737, ISBN 978-0-323-91696-7.

- Leal, R.; Alves Lima Sobrinho, R.; Tramontin Souza, M. Recycling Diatomaceous Earth Waste: Assessing Its Physicochemical Features, Recovery Techniques, Applications, Viability and Market Opportunities. Cleaner Waste Systems 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusimano, G.M.; Revue, C.A.; Chiang, J.-C.; Rustad, T.; Sasidharan, A.; Dalgaard, P.; Gasco, L.; Gai, F.; Sørensen, A.-D.M.; Geremia, E.; et al. Management of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus Thynnus) By-Products in Malta: Logistics, Biomass Quality and Environmental Impact. Journal of Cleaner Production 2025, 498, 145106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, E.B.; Fiorentini, E.F.; Dotto, G.L.; Escudero, L.B. When the Use of Derived Wastes and Effluents Treatment Is Part of a Responsible Industrial Production: A Review. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 2024, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.G.; Cabrera-Sumba, J.; Valdez-Pilataxi, S.; Villalta-Chungata, J.; Valdiviezo-Gonzales, L.; Alegria-Arnedo, C. Removal of Heavy Metals in Industrial Wastewater Using Adsorption Technology: Efficiency and Influencing Factors. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2025, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azriena, H.A.A.; Kaur, K.; Ilyas, R.A.; Kamaruddin, Z.H.; Neenu, K.V.; Midhun Dominic, C.D.; Wirawan, W.A.; Asrofi, M.; Dzulkifli, M.H.; Sulong, M.A.; et al. Recent Developments in Lignocellulosic Banana (Musa Spp.) Fibre-Based Biocomposites and Their Potential Industrial Applications: A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 323, 147180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvepalli, M.; Kairamkonda, M.; Khatoon, U.T.; Ramachandravarapu, A.K.; Godishala, V.; Velidandi, A. Transforming Lignocellulosic Based Waste into Nanomaterials for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment: A Comprehensive Review of Synthesis, Environment, Techno-Economic and Regulatory Considerations. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2025, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, Fourth Edition; Guilford Publications, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4625-2335-1.

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer, Cham, 2017; pp. 1–40, ISBN 978-3-319-05542-8.

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2015, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. Pros and Cons of Different Sampling Techniques. International Journal of Applied Research 2017, 3, 749–752. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson Education, 2019; ISBN 978-1-292-20879-4.

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo Portillo, M.T.; Hernández Gómez, J.A.; Estebané Ortega, V.; Martínez Moreno, G. Structural Equation Modelling: Features, Phases, Construction, Implementation and Results. Science & Work 2016, 18, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Dhir, S.; Das, V.M.; Sharma, A. Bibliometric Overview of the Technological Forecasting and Social Change Journal: Analysis from 1970 to 2018. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2020, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM); SAGE, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4522-1744-4.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education, 1994; ISBN 978-0-07-107088-1.

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Discriminant Validity Assessment in PLS-SEM: A Comprehensive Composite-Based Approach. Data Analysis Perspectives Journal 2022, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Radulescu, M.; Pilař, L.; Shah, S.A.R. A Holistic Approach to Sustainability: Exploring the Main and Mediating Role of Circular Economy in Net Zero Emissions. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Panigrahi, R.R.; Sharma, R.; Shrivastava, A.K. Advancing Circular Economy Performance through Blockchain Adoption: A Study Using Institutional and Resource-Based Frameworks. Sustainable Futures 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).