1. Introduction

Urbanization poses challenges in drinking water supply and sewerage management due to higher demand and greater wastewater generation, necessitating an integrated approach to infrastructure and resource optimization. Increasing urban development increases the demand for drinking water, which may go beyond the capacity of existing infrastructure [

1]. Furthermore, the concentration of people intensifies the generation of domestic wastewater [

2]. This requires much more efficient sewerage systems [

3,

4]. Efficiency in management becomes crucial to have an adequate and continuous supply [

5,

6]. Urbanization, on the other hand, has negative implications in terms of aggravating the impact of climate change [

7], requiring adaptations [

8]. Water management in this scenario will be transversal to include efficiency, sustainability and adaptation to climate change. Therefore, it is necessary to examine how WUOs have decided to use resources for this purpose and whether geography influences their performance.

Efficiency in the water sector is critical to ensuring universal access to drinking water, sustainability of water resources, and user satisfaction; several studies have shown that inefficiency in water management can have adverse effects in terms of economic losses, waste of resources, and deterioration in service quality [

9,

10]. In this context, DEA has emerged as an important tool to examine the efficiency of water utilities, their ability to identify best practices, and guide performance improvement decisions [

11].

DEA faces problems related to data comparability and underlying assumptions regarding production frontiers. Different data quality [

12], information availability [

13,

14] and data collection methods [

5](Molinos-Senante et al., 2010) do not allow for comparisons across firms. Ferro et al. [

16] indicate that data comparability is important. The definition of production frontier [

17] is also likely to be affected by external factors [

18] and assumptions related to technology [

19]. When comparing companies from different geographical locations [

20] or companies with different structures [

21], the idiosyncrasies of each scenario are paramount. Camanho et al. [

22] indicated that the selection of variables is important in performance evaluation. It can even distort the analysis and require some specific models [

23] since there could be results that are not useful, such as unaccounted for water [

24]. These are key obstacles that need to be addressed to ensure that efficiency analyses remain valid in the water industry.

There is a spatial component included in the DEA, which speaks of all those regional influences on the efficiency of the WUOs. Previous work has shown that population density, water resource availability, socioeconomic conditions and management policies can significantly affect water utilities [

25,

26,

27]. Spatial analysis allows to model spatial dependence and capture the interactions of WUOs with their geographic environment, thus allowing a more comprehensive view of the factors that cause their efficiency.

This work was carried out with data from 2020 and deals with the efficiency of water management in 49 WUO in Mexico, by applying a methodology through the DEA model with Tobit. DEA evaluates the relative efficiency of these WUOs in obtaining resources (total employment, total costs) for the production and distribution of drinking water (volume produced, population served). The premise is that the geographic location of WUOs in Mexico significantly affects their performance due to differences in socioeconomic conditions, population density, geographic conditions, and access to resources. To demonstrate this, a Tobit model is deployed that analyzes the influence of geographic location on the efficiency estimated by DEA.

The paper is organized in several stages: first, the literature on water sector efficiency, governance, and the use of DEA and Tobit models in this context is reviewed. The methodology employed is described, which combines DEA to assess the technical efficiency of WUOs and a Tobit model to analyze the effect of geographic location. Next, the PIGOO-CONAGUA data and the selected variables (employment, costs, production volume, and population served) are presented. The results of the DEA are shown, accompanied by estimates of average efficiency for WUOs under CRS and VRS, as well as the least and most efficient WUOs identified. Finally, a Tobit analysis is performed to test whether geographic location is a factor in efficiency, after which the discussion of the results is presented, a comparison with previous literature, the limitations of the study, and lines for future research are outlined.

2. Literature Review.

Governance in the water sector is essential for efficiency and public trust. Transparent, accountable, and participatory governance [

28,

29] is often linked to more efficient resource management, though its impact may vary based on local implementation and political dynamics [

30,

31], process optimization [

32] and continuous service improvement [

33]. Control has incorporated transparency into trust generation [

1], while public participation [

34] legitimizes actions and facilitates adaptive solutions. Pinto et al. [

35] and Molinos-Senante et al. [

36] have confirmed the importance of governance for efficiency and optimization of services. Public participation enhances public trust, as noted by Walker et al. [

37]. Strong governance ensures the efficiency, sustainability and legitimacy of water companies.

Since the 1983 reform, the institutional framework for water in Mexico aimed to decentralize management and grant greater autonomy to WUOs, adopting a client-oriented approach. However, challenges remain in separating service provision from political influence. However, this model failed to sever the ties between the service and politics, maintaining subordination to mayors and governors. Although private participation was encouraged, it prospered mainly in the construction of treatment plants, not in the operation of services, which are mostly maintained in the public sphere with a "low-level equilibrium" [

38].

The evaluation of water companies’ performance takes into account parameters other than technical and economic efficiency. Service quality, which includes aspects such as continuity of supply [

39], water quality [

40] and customer service [

41], has a considerable impact on customer satisfaction.

Environmental sustainability also acquires much greater importance and studies that analyse eco-efficiency [

25,

42], greenhouse gas emissions [

43] and water loss management [

10,

44] have identified it as one of the main indicators.

Several factors influence firm performance, including efficiency, service quality, and financial sustainability. These factors are regulations [

12,

45], incentives [

46,

47], ownership structure [

48,

49,

50], responsiveness [

35,

51], and governance structure [

52,

53]. Finally, asset management, including investment planning and infrastructure maintenance, is crucial for future service continuity and quality [

54,

55].

Performance evaluation and benchmarking are crucial for water utilities to optimize their efficiency and improve customer service. Techniques such as DEA [

21,

46,

56,

57] and the Malmquist index [

8,

24], among others, allow identifying best practices and inefficiencies [

57,

58]. This process of learning and sharing successful strategies [

59,

60], which is facilitated by benchmarking and comparison between companies [

32,

61] or operational units [

62], promotes efficiency in the use of resources [

63], encourages innovations [

15,

47] and drives improvements in service quality [

46,

64]. Studies such as Marques et al. [

65], Marques & De Witte [

66] and Molinos-Senante et al. [

67] attest to these tools for service optimization and improvement. Combined, they result in efficient, transparent and customer-oriented management.

The decision to combine the DEA with a Tobit model in efficiency studies arises from the need to have a broader and more precise view of the subject. The DEA allows the relative efficiency of a set of decision units to be assessed without restrictions on the functional form of the production frontier [

68] as it is a non-parametric technique. However, on its own, the DEA does not allow the identification of those factors that explain the differences in efficiency between decision units. This is where the Tobit model complements the analysis. It is a regression model for limited or censored dependent variables, so Tobit allows the impact of various explanatory variables on the efficiency scores obtained in the DEA to be analysed [

69]. In the specific case of water efficiency, this means that factors such as regulation, investment in infrastructure, socioeconomic characteristics and climatic conditions that influence the performance of water companies can be identified [

70]. DEA-Tobit therefore presents a robust methodology through which efficiency and its determinants can be analysed, thereby leading to a more complete understanding of the phenomenon and more precise recommendations for improving it. This study aims to provide an understanding of the very complex interactions underpinning efficiency and to equip decision-making with such knowledge. It is therefore particularly designed to analyse whether geographical location has a significant influence on the efficiency of WUOs.

There is a debate about the role of geography in the efficiency of water industries. Some studies indicate that companies located in rural areas tend to be inefficient due to population dispersion and extensive distribution networks [

23,

61], while others argue that rurality alone is not a determining factor, but interacts with variables such as customer density and available infrastructure [

46,

59]. Ferro et al. [

51], Zschille and Walter [

71] emphasize that regional factors, including resource availability, socioeconomics and ownership structure, affect efficiency. However, there is no clear link between region and efficiency, according to Peda et al. [

72]. This interrelation is complex and requires a multifactorial analysis, according to the particularities of each context [

19,

73].

Most research on water efficiency in industry has opened some gaps in terms of research on how the interaction between region and demand side management influences performance. Although there have been studies on the effect of population density [

46,

47,

59,

61,

63] and water availability [

61], only few have explored how demand side management strategies such as tariffs [

74], public education [

34] and saving technologies [

6] interact with regional specificities. With this in mind, a study is proposed that combines DEA with a quantitative approach and examines the impact of DEA on various microregions to analyse their strategies. Studies such as Suárez-Varela et al. [

75],| Molinos-Senante and Sala-Garrido [

76], Ferro et al. [

51] and Zschille and Walter [

71] have highlighted the need to analyse this interaction between regional factors and demand management.

Studies combining DEA and Tobit models provide a more comprehensive analysis of water use efficiency. While DEA identifies efficient and inefficient units [

21,

46,

56,

57], Tobit models analyze which factors lead to inefficiency [

21,

60]. This combination also allows for the study of relationships such as regulation, ownership, and management. Simar and Wilson [

21] applied this approach to the study of efficiency in water services and found ownership and organizational structure to be key. Renzetti and Dupont [

60] applied it to the analysis of municipal water agencies and included environmental factors. Together, it is a powerful combination that provides analysis to measure inefficiency and directs the identification of its determinants.

The Tobit model: It is useful for investigating censored or limited dependent variables. It has been used quite successfully along with DEA to identify the different factors affecting water use efficiency. Integration of both techniques can facilitate the measurement of efficiency and an investigation into how regulation, ownership and management influence the level of efficiency across firms. Chakraborty et al., [

77] in education and Rangan et al., [

78] in the banking sector reveal its usefulness. The Tobit model along with DEA provides a very strong argument for efficiency analysis in the water sector.

3. Methodology

To analyse water efficiency, a two-phase methodological scheme is suggested, first using DEA to obtain efficiency scores for each company [

21,

56,

57], comparing it with best practices [

57,

58], then detecting potential input reductions [

58,

60]. The approach is supported by studies such as those by Charnes et al. [

56] and Ferreira da Cruz et al. [

79]. Second, a Tobit model is used to study the impact of uncontrollable factors on inefficiencies [

21,

60], such as regulations, population density and water availability. Maddala [

80] describes the combination of DEA and Tobit, which provides a deeper understanding of the determinants of efficiency and helps identify gaps in this area and formulate more effective policies.

This is a DEA model in which inputs seek to minimize resources, even to produce a specific quantity of products [

17]. In the study of water, this will be the evaluation of how resource inputs such as water, energy and capital can be reduced in companies while maintaining the level of services [

63,

81]. The efficient frontier is the one that represents those companies that cause production maximization from the lowest input [

21,

56,

57] that also function as a ’reference point’. Inefficient companies will be projected on this frontier to identify possible reductions [

58,

60] and show how much reduction of resources they would have if they had produced at the same level of efficiency as the best. Studies such as Ferreira da Cruz et al. [

79] and Charnes et al. [

56] have validated this approach. Therefore, the input-oriented treatment of DEA theory studies would guide water utilities towards optimization, cost reduction and improved sustainability of their operations [

64,

82].

The choice of an input-oriented DEA model is concerned with assessing the efficiency of public utilities, especially when cost reductions and optimal use of resources must be achieved without affecting the quality of services provided. This model can identify best practices in the management of inputs [

17], such as water, energy and capital [

63,

81], to achieve a certain level of service. Faraia et al. [

83] advocate for the same model. In water utilities, efficiency, sustainability [

82], cost reduction [

63,

84] and supply optimization [

2](Cetrulo et al., 2019) are crucial. The input-oriented DEA model identifies opportunities for improvement [

58,

60] with service levels being maintained [

85]. Furthermore, by comparing companies [

19,

32], it encourages learning and the adoption of more efficient strategies [

59,

60]. Therefore, this model is promising with respect to improving efficiency and sustainability, ensuring optimal use of resources without compromising service.

The DEA of this study to determine efficiency among water companies has considered as inputs EmplTotal (number of employees) [

86,

87] and CostoTotal (total costs) [

28,

63], reflecting human and financial resources (See

Table 1). As outputs, there are VolProd (production volume) [

28,

84] and PoblAtend (population served) [

31]. It is assumed that a greater number of employees and costs are related to greater production and attention. However, efficiency is maximizing production with minimum resources [

21,

56,

57]. At this stage, the DEA would only be responsible for identifying efficient and inefficient companies for decision making.

In an environment that demands efficiency and transparency in public services, tools such as DEA are essential to assess performance and improve management functions. DEA offers a comparison between several units in terms of their relative efficiency [

56,

57], presents an objective picture of the company’s performance [

19,

32] and identifies best practices [

59,

60]. By including multiple inputs and outputs, DEA offers a more comprehensive assessment than traditional methods [

58]. Charnes et al. [

56] and Carvalho and Marques [

5] prove the effectiveness of DEA in assessing efficiency. Furthermore, by considering the particularities of each company [

21,

60], the DEA promotes equity in comparisons, thus avoiding bias [

19,

20]. Through the DEA, efficient and transparent management of public services is achieved, promoting continuous improvement.

CRS and VRS models are used in DEA for efficiency evaluation. CRS (Constant Returns to Scale) stands for constant return to scale [

56]. VRS (Variable Returns to Scale) indicates that the returns are variable [

57]. The selection of requirements is made based on whether the increase in inputs leads to an equivalent increase in outputs or not.

According to Charnes et al. [

56], the input-oriented CRS model within data envelopment analysis is recognized as a robust framework for assessing the efficiency of data measurement units. The model minimizes the inputs required to produce a predetermined level of output, which lends itself particularly well to measuring efficiency based on given quantities of resources generated in the outputs. Input reduction especially benefits organizations that focus on optimizing resources and improving their performance in terms of productivity.

Mathematical Model

In this context, we consider n Decision-Making Unit(s) (DMUs), each with m inputs and s outputs. We define:

The objective is to evaluate the efficiency of a specific DMU, say DMU k. Efficiency is measured by minimizing the total amount of inputs used, given a desired level of output.

The input-oriented CRS model can be expressed as a linear programming problem that seeks to minimize the amount of inputs used by the DMU

k, subject to the constraint that at least the output levels of the outputs must be achieved. This is formulated as follows :

Using the CRS input-DEA model, the efficiency of a DMU is analyzed using the θk criterion. The value of θk is set equal to 1 so that it is considered efficient by the DMU, that is, with the minimum amount of inputs to produce it. If θk were greater than 1, the DMU would be inefficient and could reduce the use of inputs. Additionally, in the model, the relative importance of each input (vi) is determined to minimize its use in production.

On the other hand, the VRS Model in DEA, according to Banker [

57], evaluates efficiency on the basis that the relationship between inputs and products, according to the size of each DMU, varies with the scale of operation. This allows us to observe how the quantity of inputs and their volume influences efficiency itself. The input-oriented VRS model specifies the minimization of inputs given the products obtained, and thus performs a more precise evaluation in reference to DMUs of different scales. The objective function is expressed as:

where x

ij represents the inputs used by DMU

j, y

rj are the products obtained, v

i are the weights assigned to the inputs and ur are the weights assigned to the products.

To ensure the validity of the evaluation, constraints are imposed to ensure that the level of inputs used by DMU

j is not lower than that of the other DMUs in the set. This can be expressed as follows:

where

J is the set of all DMUs.

To incorporate the concept of variable returns to scale, an additional restriction is imposed that allows the sum of the weights to be less than or equal to one:

This restriction allows the efficiency frontier to be properly adjusted to the operating scale of each DMU, given that not all DMUs operate under fully optimized conditions with respect to the their inputs.

After the DEA, the Tobit model in the second stage will include the variable “region” [

70] in order to analyze whether the geographic location (microregions

1) has an effect on the efficiency scores of the WUOs, thus completing the DEA and allowing a greater understanding of whether there are regional disparities in performance. Smithson and Merkle [

93] explain that the Tobit model is used to analyze censored variables, assuming that the dependent variable follows a normal distribution. It is expressed as:

where

is the latent variable and

is the normally distributed error. Censoring is defined as:

The model allows inferences about relationships between variables, estimating parameters using maximum likelihood, being useful for limited data.

Finally, this study was developed with information from the Program of Management Indicators of Operating Agencies (PIGOO) available on the official portal of the Mexican Institute of Water Technology (

http://www.pigoo.gob.mx/) which depends on the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) for the year 2020. The technical efficiency analysis was carried out using the DEA methodology with the DEAP software version 2.1. In addition, the Tobit model analysis was carried out with RStudio, thus guaranteeing a robust and adequate statistical treatment of the analyzed data.

4. Results

Table 2 shows the results of the descriptive statistics for the WUOs, which reflect a fairly high variability between the variables considered, so the differences in operation and capacities are significant. The variable EmplTotal registers a maximum of 4,684 and a minimum of 127, obtaining a standard deviation of 787.06, indicating a medium dispersion between the numbers of workers among the agencies. The coefficient of variation (CV) of 1.12 (112%) reflects a marked heterogeneity in the labor structure of the agencies, which could be due to differences in size and scope in their operations. On the other hand, the variable Vprod presents an extremely wide range - from a maximum of 8,501,117,672.79 to a minimum of 52,474,136.00 with a standard deviation of 1,306,895,758.27 and a CV of 1.70 (170%). This highlights significant differences in productivity and revenue-generating capacity between agencies.

For the variable TotalCost, values range from a maximum of $478,689,022.10 to a minimum of $935,663.00, with a standard deviation of $85,065,234.75 and a CV of 1.28 (128%). This reflects a large dispersion between operating costs, which probably originates from variations in the scale of operation, efficiency, and characteristics of the areas served. Finally, the variable PobAtend has a maximum of 4,957,280 people and a minimum value of 105,201, with an associated standard deviation of 931,248.79 and a CV of 1.36 (136%), showing differences within the population served by each agency, probably due to density and territory factors that influence the amount of population served.

In

Table 3, the correlation matrix comprises the correlation coefficients of variables, which analyze the linear relationships between them. First, total employment versus total costs is correlated at a level of 0.95, which represents a highly positive linear relationship. This means that, in general, the increase in the total number of employees is related to higher expenditures incurred on operating costs.

EmplTotal correlates with Vprod at a coefficient of 0.93, again suggesting a strong positive linear correlation. From the above correlations, it can be seen that higher staff strength tends to be associated with higher outputs measured as value, reflecting the value placed on human resources to achieve production capability.

Table 3.

Analysis of correlation coefficients of variables.

Table 3.

Analysis of correlation coefficients of variables.

| |

EmplTotal |

TotalCost |

Vprod |

PopAtend |

| EmplTotal |

1 |

|

|

|

| TotalCost |

0.95389497 |

1 |

|

|

| Vprod |

0.93444161 |

0.92170399 |

1 |

|

| PopAtend |

0.94560348 |

0.91203689 |

0.95531224 |

1 |

On the other hand, EmplTotal and PobAtend represent a correlation of 0.95, so this indicates a very substantial and strong positive linear correlation. This indicates that cities or entities with a larger number of employees tend to serve larger populations, which is indicative of a possible larger operational scale as well.

For example, the correlation between CostTotal and Vprod is 0.92, indicating a strong association. However, this does not establish causality between the variables. This would mean that if total costs were to increase, the value of output would follow suit, probably due to the cost factor of the inputs and materials that the stakeholders have to produce.

CostTotal and PobAtend have a correlation of 0.91, indicating a strong positive linear relationship, but not as strong as some other combinations. This suggests that costs have generally increased with a population being served, but the relationship is not as close as in other cases. Between Vprod and PobAtend, the correlation is 0.96, the highest.

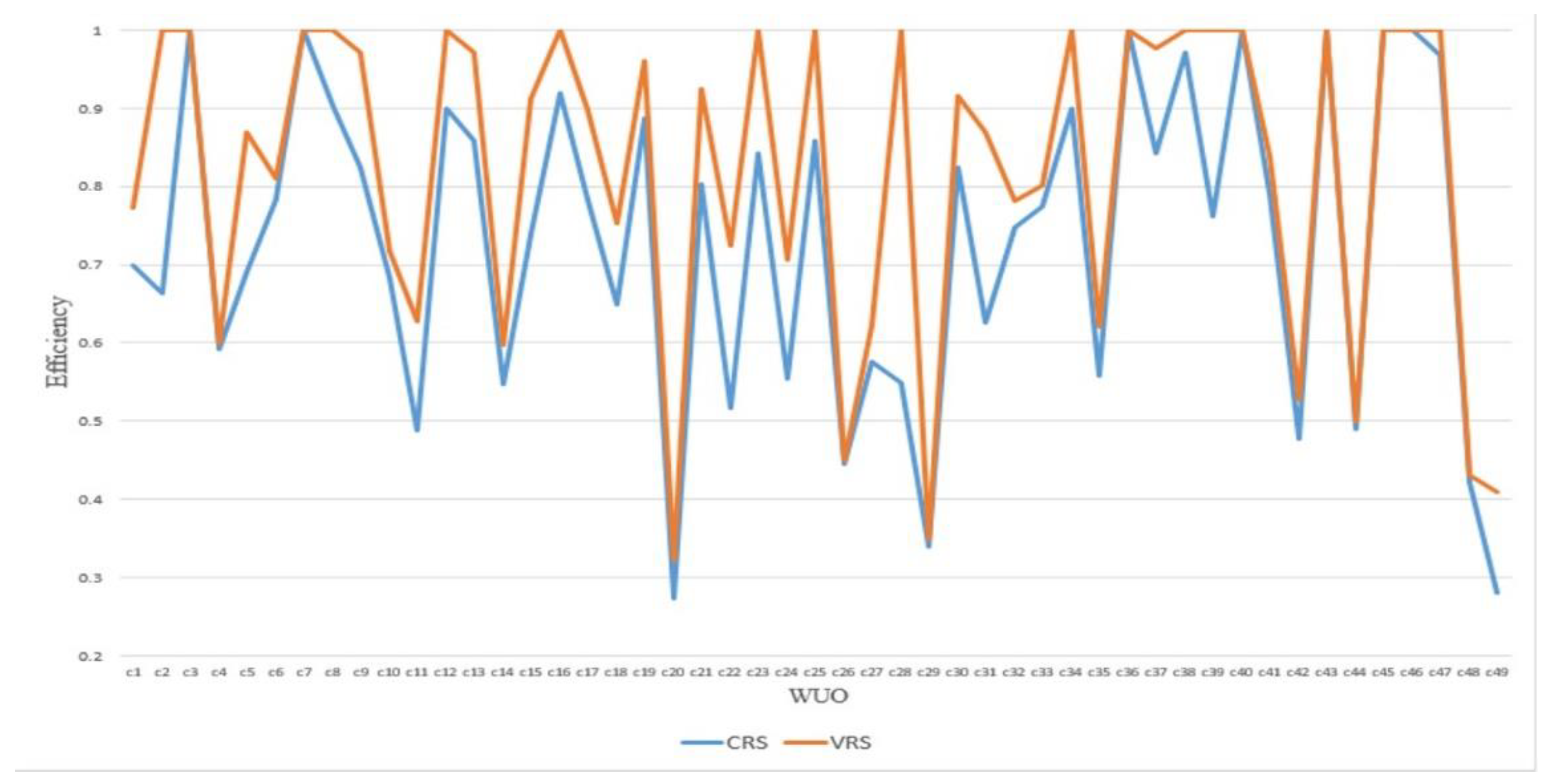

In

Figure 1, the DEA shows an average efficiency of 0.73 under CRS and 0.82 under VRS. This means that, on average, cities could reduce their inputs by 27% (under CRS) or 18% (under VRS) without affecting their level of output.

The cities with the lowest efficiencies (Huixquilucan, Zihuatanejo, Naucalpan, Zacatecas and Matamoros) exhibit substantial potential for improvement. Conversely, 7 cities are efficient under CRS and 18 under VRS, making them exemplary cases.

Figure 1.

Relative efficiency by DEA of the WUO in 2020. Source: Prepared by the authors using data from PIGOO-CONAGUA.

Figure 1.

Relative efficiency by DEA of the WUO in 2020. Source: Prepared by the authors using data from PIGOO-CONAGUA.

Optimizing resource management primarily requires cities, especially those lagging behind in efficiency, to measure inefficiency in various areas, learn from and adopt best practices, optimize their resource allocations, reduce waste, improve technology and staff training.

In order to better understand the differences in terms of efficiency, it would be possible to complement the DEA with a Tobit model, because the DEA alone does not consider external factors that may influence the efficiency of the WUOs, adding the geographical location as an independent variable. This will then allow taking into account the external factors that determine efficiency and also understanding regional differences, thus improving the accuracy of the analysis and, consequently, the decisions that are taken.

A first Tobit analysis was performed on the efficiency data from the DEA-CRS analysis in 49 WUOs and “microregions” was used to denote geography. The results suggest that this variable has no statistically significant effect on efficiency (p-value = .814). This means that geography, as interpreted here, does not account for the differences in efficiency. The constant coefficients of the model, 0.731 and -1.466, are statistically significant (p-value < 2e-16), and no reliability problems in the estimates, such as the Hauck-Donner effect, were detected.

Despite these observations, the model has very low explanatory power with an R² of only 0.003 and a correlation of 0.055 between the fitted and observed values. "Microregions" are not a significant factor in explaining service delivery efficiency in the cities studied; greater explanatory power could come from the inclusion of additional variables.

A second Tobit analysis was performed with the efficiency data from the DEA-VRS analysis in 49 WUOs and the variable microregions was used to denote geography. This analysis reveals that this variable has no statistically significant influence on efficiency (p-value = 0.794). In other words, according to the requested representation, the region does not explain the differences in efficiency between the cities considered.

Among the key results of the model, the coefficients for the constant “(Intercept):1” are at 0.871 and for “(Intercept):2” -1.215; both are highly significant with a p-value < 2e-16. The log-likelihood of the model is -21.2935 with 95 degrees of freedom and no Hauck-Donner effect was found, supporting the reliability of the estimates. The explanatory capacity of the model, however, is small, as evidenced by the low coefficient of determination (R²=0.002) and only a correlation of 0.045 between the fitted and observed values under the Variable Return on Scale (VRS) model. In other words, the analysis suggests that “Microregions” are not a significant factor in terms of efficiency in public service provision in the cities focused on.

Comparison of the Tobit model results using DEA-CRS and DEA-VRS efficiencies shows that in both cases microregions were found to have no statistically significant effect on efficiency. However, the correlation between modeled and observed values is slightly higher in the case of CRS (0.055) than in the case of VRS (0.045), while the R2 of the model remains very low in both approaches (0.003 for CRS and 0.002 for VRS). These measurements reinforce the idea: regardless of the returns to scale assumption, the Tobit model has limited explanatory power and geographic location, represented by the microregions variable, does not seem to be a critical determinant of WUO efficiency.

5. Discussion

This DEA-Tobit analysis assessed the water management efficiency of 49 Mexican water utilities, analyzing employment, costs, production volume, and population served at the water utility level. The DEA results indicated average efficiencies of 0.73 (CRS) and 0.82 (VRS), which were consistent with previous studies but still show potential for improvement. Aguascalientes, Celaya, and Saltillo were identified as efficient water utilities, while Huixquilucan, Zihuatanejo, and Naucalpan were identified as having potential optimization possibilities, among others.

According to Tobit analysis, geographic location does not affect efficiency. We take this opportunity to acknowledge the relevance of applying regional factors such as resource availability, socioeconomics and climatic conditions; these factors could have an effect on the efficiency of WUOs.

Some limitations of the study, such as the selection of variables and the possible omission of other important factors such as water quality, customer satisfaction and demand management, deserve to be pointed out. Although digitalisation and new technologies are changing the way water is managed, the existing literature largely fails to address their effect on the efficiency of water utilities. This calls for research into how the adoption of information and communication technologies (ICT), remote sensing, data analytics and other technologies can lead to more efficient management of water resources, with cost reduction and improved service delivery.

The literature on water efficiency has mainly focused on factors such as regulation, ownership, operations management, and environmental variables. However, climate change and increasing uncertainty about the availability of water resources pose new challenges in water management [

94]. There is a need to investigate how uncertainty and climate change affect the efficiency of WSOs and the means by which water utilities can adapt to these challenges to ensure sustainability.

While the result is valid, it would be worth investigating the possible reasons for this lack of significance. The lack of significance of “microregions” in the Tobit model, which indicates that geographic location does not affect the efficiency of WUOs, may be the result of several factors. First , efficiency may be more closely related to management, investment, water quality, and consumer satisfaction than to region [

39,

95]. Second, The variable ’microregions’ used in this analysis represents broad geographic categories. Its lack of granularity may obscure finer regional differences such as socioeconomic conditions or infrastructure levels [

26,

95]. Third, heterogeneity between micromicroregions can blur the regional effect [

9,

27].

The article therefore contributes to understanding the efficiency of water management in Mexico, showing the need to optimize resources and take into account contextual factors. Future research should examine the determinants of efficiency in the sector to contribute to improving the management of this vital resource.

6. Conclusions

The DEA assessed the water management efficiency of 49 water utility organizations in Mexico, showing significant potential for improvement. Cities such as Aguascalientes, Celaya and Saltillo were identified as performing efficiently, but could be examples of best practices for those with greater room for improvement, such as Huixquilucan, Zihuatanejo and Naucalpan.

The Tobit model did not show a significant effect of geographic location on efficiency; however, this research provided an avenue for further studies that delved deeper into regional-specific factors such as water availability, population density, and climatic conditions on WUO performance.

It is very important to highlight the importance of this type of studies in decision-making in the water sector in Mexico. A clear identification of the areas where there are inefficiencies and the factors that affect performance could help WUO to optimize resource management, improve service quality and contribute to environmental sustainability.

Future studies should include additional variables such as water quality, customer satisfaction, and demand management to gain a more complete understanding of water management efficiency; further exploration of the application of complementary techniques such as stochastic frontier analysis for more robust analysis is also recommended.

In fact, this study advances the understanding of the efficiency of the water sector in Mexico and contributes to laying the foundations for future research aimed at improving this key service.

Author Contributions

G.N.L.: Writing—original draft, Methodology; Conceptualization, Administration; J.A.S.R.: Writing—review and editing; R.C.L.B.: Writing—original draft, Methodology; L.A.C.R.: Conceptualization and Methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WUOs |

Water Utility Organizations |

| DEA |

Data Envelopment Analysis |

| CRS |

Constant Returns to Scale |

| VRS |

Variable Returns to Scale |

| DMUs |

Decision-Making Unit(s) |

| CV |

Coefficient of variation |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| PoblAtend |

Population served |

| EmplTotal |

Number of employees |

| CostoTotal |

Total costs |

| VolProd |

Total volume of drinking water |

| PIGOO |

Program of Management Indicators of Operating Agencies |

| CONAGUA |

National Water Commission |

Notes

| 1 |

In Mexico, there are nine regions: Northwest, Northeast, West, East, North Central, South Central, Southwest, Southeast, and Center. However, the selected OOAs, which will be part of the analysis, belong to the Central, West, Northeast, Northwest, and South-Southeast regions. They will focus solely on analyzing those five regions. |

References

- Marques, R. C., Berg, S., & Yane, S. (2014). Nonparametric benchmarking of Japanese water utilities: institutional and environmental factors affecting efficiency. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management, 140(5), 562-571. [CrossRef]

- Cetrulo, T. B., Marques, R. C., & Malheiros, T. F. (2019). An analytical review of the efficiency of water and sanitation utilities in developing countries. Water research, 161, 372-380.

- Gidion, D. K., Hong, J., Adams, M. Z., & Khoveyni, M. (2019). Network DEA models for assessing urban water utility efficiency. Utilities policy, 57, 48-58.

- Golder, P. N., Mitra, D., & Moorman, C. (2012). What is quality? An integrative framework of processes and states. Journal of marketing, 76(4), 1-23.

- Carvalho, P., & Marques, R. C. (2011). The influence of the operational environment on the efficiency of water utilities. Journal of environmental management, 92(10), 2698-2707.

- Kirkpatrick, C., Parker, D., & Zhang, Y. F. (2006). An empirical analysis of state and private-sector provision of water services in Africa. The World Bank Economic Review, 20(1), 143-163. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A. (2012). Service productivity and service quality: A necessary trade-off?. International Journal of Production Economics, 135(2), 800-812.

- Feng, Y., Zhu, Q., & Lai, K. H. (2017). Corporate social responsibility for supply chain management: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 158, 296-307. [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Senante, M., & Maziotis, A. (2020). Drivers of productivity change in water companies: an empirical approach for England and Wales. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 36(6), 972-991. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A. L., Martins, R., & Dias, L. C. (2023). Drivers of water utilities’ operational performance–An analysis from the Portuguese case. Journal of Cleaner Production, 389, 136004. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, O., Hasan, M., Kurniasari, F., Hermawan, A., & Gunardi, A. (2019). Productivity and efficiency analysis using DEA: Evidence from financial companies listed in bursa Malaysia. Management Science Letters, 9(2), 301-312. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, B., & Andrade-Campos, A. (2014). Efficiency achievement in water supply systems—A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 30, 59-84. [CrossRef]

- Mann, P. C., & Mikesell, J. L. (1976). Ownership and water system operation 1. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 12(5), 995-1004. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Cook, D. J., Eastwood, S., Olkin, I., Rennie, D., & Stroup, D. F. (1999). Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. The Lancet, 354(9193), 1896-1900. [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Senante, M., Hernández-Sancho, F., & Sala-Garrido, R. (2010). Economic feasibility study for wastewater treatment: A cost–benefit analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 408(20), 4396-4402.

- Ferro, G., Romero, C. A., & Covelli, M. P. (2011). Regulation and performance: A production frontier estimate for the Latin American water and sanitation sector. Utilities Policy, 19(4), 211-217.

- Romano, G., & Guerrini, A. (2011). Measuring and comparing the efficiency of water utility companies: A data envelopment analysis approach. Utilities Policy, 19(3), 202-209. [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P. J., Mavros, P., & Wassmer, R. W. (1999). Public sector technical inefficiency in large US cities. Journal of Urban Economics, 46(2), 278-299. [CrossRef]

- De Witte, K., & Marques, R. C. (2010a). Designing performance incentives, an international benchmark study in the water sector. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 18, 189-220. [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J., Crase, L., Dollery, B., & Villano, R. (2010). The relative economic efficiency of urban water utilities in regional New South Wales and Victoria. Resource and Energy Economics, 32(3), 439-455. [CrossRef]

- Simar, L., & Wilson, P. W. (2007). Estimation and inference in two-stage, semi-parametric models of production processes. Journal of econometrics, 136(1), 31-64. [CrossRef]

- Camanho, A. S., Silva, M. C., Piran, F. S., & Lacerda, D. P. (2024). A literature review of economic efficiency assessments using Data Envelopment Analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 315(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Bottasso, A., & Conti, M. (2009). Scale economies, technology and technical change in the water industry: Evidence from the English water only sector. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 39(2), 138-147. [CrossRef]

- Daraio, C., & Simar, L. (2005). Introducing environmental variables in nonparametric frontier models: a probabilistic approach. Journal of productivity analysis, 24, 93-121. [CrossRef]

- Sala-Garrido, R., Mocholí-Arce, M., Molinos-Senante, M., & Maziotis, A. (2021). Comparing operational, environmental and eco-efficiency of water companies in England and Wales. Energies, 14(12), 3635.v. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L., Song, S., & Xie, Y. (2022). Evaluation of water resources utilization efficiency in Guangdong Province based on the DEA–Malmquist model. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 819693. [CrossRef]

- Tourinho, M., Barbosa, F., Santos, P. R., Pinto, F. T., & Camanho, A. S. (2023). Productivity change in Brazilian water services: A benchmarking study of national and regional trends. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 86, 101491. [CrossRef]

- Estache, A., & Kouassi, E. (2002). Sector organization, governance, and the inefficiency of African water utilities. Governance, and the Inefficiency of African Water Utilities (September 2002). https://ssrn.com/abstract=636253.

- Walter, M., Cullmann, A., von Hirschhausen, C., Wand, R., & Zschille, M. (2009). Quo vadis efficiency analysis of water distribution? A comparative literature review. Utilities Policy, 17(3-4), 225-232. [CrossRef]

- Levidow, L., Lindgaard-Jørgensen, P., Nilsson, Å., Skenhall, S. A., & Assimacopoulos, D. (2016). Process eco-innovation: assessing meso-level eco-efficiency in industrial water-service systems. Journal of Cleaner Production, 110, 54-65. [CrossRef]

- Tupper, H. C., & Resende, M. (2004). Efficiency and regulatory issues in the Brazilian water and sewage sector: an empirical study. Utilities Policy, 12(1), 29-40. [CrossRef]

- Färe, R., Grosskopf, S., Norris, M., & Zhang, Z. (1994). Productivity growth, technical progress, and efficiency change in industrialized countries. The American economic review, 66-83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2117971.

- Meeusen, W., & van Den Broeck, J. (1977). Efficiency estimation from Cobb-Douglas production functions with composed error. International economic review, 435-444. [CrossRef]

- Aigner, D., Lovell, C. K., & Schmidt, P. (1977). Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production function models. Journal of econometrics, 6(1), 21-37. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, FS, Simões, P., & Marques, RC (2017a). Raising the bar: the role of governance in performance assessments. Utilities Policy , 49 , 38-47.

- Molinos-Senante, M., Maziotis, A., & Sala-Garrido, R. (2017). Assessment of the total factor productivity change in the English and Welsh water industry: A Färe-primont productivity index approach. Water Resources Management, 31, 2389-2405. [CrossRef]

- Walker, N. L., Styles, D., Gallagher, J., & Williams, A. P. (2021). Aligning efficiency benchmarking with sustainable outcomes in the United Kingdom water sector. Journal of Environmental Management, 287, 112317. [CrossRef]

- Pineda Pablos, N. (2017). Urban water management between opportunism and adaptive development. Denzin, Christian, Taboada, Federico, Pacheco-Vega, Raúl, Water in Mexico, actors, sectors and paradigms for an ecological social transformation, Mexico, Ed. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung , 171-193. http://centro.paot.org.mx/documentos/paot/libro/aguaen_mexico.pdf.

- Maziotis, A., Sala-Garrido, R., Mocholi-Arce, M., & Molinos-Senante, M. (2023). Cost and quality of service performance in the Chilean water industry: A comparison of stochastic approaches. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 67, 211-219. [CrossRef]

- García-Rubio, M. A., González-Gómez, F., & Guardiola, J. (2010). Performance and ownership in the governance of urban water. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Municipal Engineer (Vol. 163, No. 1, pp. 51-58). Thomas Telford Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Mugisha, S. (2007). Performance assessment and monitoring of water infrastructure: an empirical case study of benchmarking in Uganda. Water policy, 9(5), 475-491. [CrossRef]

- Villegas, A., Molinos-Senante, M., & Maziotis, A. (2019). Impact of environmental variables on the efficiency of water companies in England and Wales: A double-bootstrap approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26, 31014-31025. [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Senante, M., & Maziotis, A. (2021). The impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the performance of water companies: a dynamic assessment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(35), 48284-48297. [CrossRef]

- Mocholi-Arce, M., Sala-Garrido, R., Molinos-Senante, M., & Maziotis, A. (2021). Performance assessment of water companies: A metafrontier approach accounting for quality of service and group heterogeneities. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 74, 100948. [CrossRef]

- See, K. F. (2015). Exploring and analysing sources of technical efficiency in water supply services: some evidence from Southeast Asian public water utilities. Water resources and economics, 9, 23-44. [CrossRef]

- Hana, U. (2013). Competitive advantage achievement through innovation and knowledge. Journal of competitiveness, 5(1), 82-96. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. S., Simões, P., & Marques, R. C. (2017b). Water services performance: do operational environment and quality factors count?. Urban Water Journal, 14(8), 773-781.Rangan, N., Grabowski, R., Aly, H. Y., y Pasurka, C. (1988). The technical efficiency of US banks.Economics letters,28(2), 169-175. [CrossRef]

- Filippini, M., Hrovatin, N. & Zoric, J., (2008). Cost efficiency of Slovenian water distribution utilities: an application of stochastic frontier methods. J. Prod. Anal. 29(2), 169-182. [CrossRef]

- Mbuvi, D., De Witte, K., & Perelman, S. (2012). Urban water sector performance in Africa: A step-wise bias-corrected efficiency and effectiveness analysis. Utilities Policy, 22, 31-40.

- Molinos-Senante, M., Villegas, A., & Maziotis, A. (2019). Are water tariffs sufficient incentives to reduce water leakages? An empirical approach for Chile. Utilities Policy, 61, 100971. [CrossRef]

- Ferro, G., Lentini, E. J., Mercadier, A. C., & Romero, C. A. (2014). Efficiency in Brazil’s water and sanitation sector and its relationship with regional provision, property and the independence of operators. Utilities Policy, 28, 42-51. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M., & Tavares, A. F. (2017). The same deep water as you? The impact of alternative governance arrangements of water service delivery on efficiency. Journal of Strategic Contracting and Negotiation, 3(2), 78-101. [CrossRef]

- Nyathikala, S. A., Jamasb, T., Llorca, M., & Kulshrestha, M. (2023). Utility governance, incentives, and performance: evidence from India’s urban water sector. Utilities Policy, 82, 101534. [CrossRef]

- Heather, A. I. J., & Bridgeman, J. (2007). Water industry asset management: a proposed service-performance model for investment. Water and environment journal, 21(2), 127-132. [CrossRef]

- Vilarinho, H., D’Inverno, G., Nóvoa, H., & Camanho, A. S. (2023). The measurement of asset management performance of water companies. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 87, 101545. [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European journal of operational research, 2(6), 429-444. [CrossRef]

- Banker, R. D., Charnes, A., & Cooper, W. W. (1984). Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Management science, 30(9), 1078-1092. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P., Marques, R. C., & Berg, S. (2012). A meta-regression analysis of benchmarking studies on water utilities market structure. Utilities Policy, 21, 40-49.

- Anwandter, L. (2002). Can public sector reforms improve the efficiency of public water utilities?. Environment and Development Economics, 7(4), 687-700. [CrossRef]

- Renzetti, S., & Dupont, D. P. (2009). Measuring the technical efficiency of municipal water suppliers: the role of environmental factors. Land Economics, 85(4), 627-636. [CrossRef]

- Saal, D. S., Parker, D., & Weyman-Jones, T. (2007). Determining the contribution of technical change, efficiency change and scale change to productivity growth in the privatized English and Welsh water and sewerage industry: 1985–2000. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 28, 127-139. [CrossRef]

- De Witte, K., & Marques, R. C. (2010b). Influential observations in frontier models, a robust non-oriented approach to the water sector. Annals of Operations Research, 181, 377-392. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Zhang, X., Feng, L., & Yang, W. (2020). Disruption risks in supply chain management: a literature review based on bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Production Research, 58(11), 3508-3526. [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Tadeo, A. J., Sáez-Fernández, F. J., & González-Gómez, F. (2008). Does service quality matter in measuring the performance of water utilities?. Utilities Policy, 16(1), 30-38. [CrossRef]

- Marques, R. C., Simões, P., & Pires, J. S. (2011). Performance benchmarking in utility regulation: the worldwide experience. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 20(1), 125-132..https://www.pjoes.com/Performance-Benchmarking-in-Utility-Regulation-r-nthe-Worldwide-Experience,88538,0,2.html.

- Marques, R. C., & De Witte, K. (2010). Towards a benchmarking paradigm in European water utilities. Public Money & Management, 30(1), 42-48. [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Senante, M., Donoso, G., Sala-Garrido, R., & Villegas, A. (2018). Benchmarking the efficiency of the Chilean water and sewerage companies: a double-bootstrap approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25, 8432-8440. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W. W., Seiford, L. M., & Tone, K. (2007). Data envelopment analysis: a comprehensive text with models, applications, references and DEA-solver software (Vol. 2, p. 489). New York: springer.

- Worthington, A. C. (2011). Efficiency, technology, and productivity change in Australian urban water utilities. Technology, and Productivity Change in Australian Urban Water Utilities (May 16, 2011). [CrossRef]

- Buendía Hernández, A., André, F. J., & Santos-Arteaga, F. J. (2024). On the Evolution and Determinants of Water Efficiency in the Regions of Spain. Water Resources Management, 38(9), 3093-3112. [CrossRef]

- Zschille, M., & Walter, M. (2012). The performance of German water utilities: a (semi)-parametric analysis. Applied Economics, 44(29), 3749-3764. [CrossRef]

- Peda, P., Grossi, G., & Liik, M. (2013). Do ownership and size affect the performance of water utilities? Evidence from Estonian municipalities. Journal of Management & Governance, 17, 237-259. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D. K., Dichev, D., & Raffiee, K. (1993). Ownership and sources of inefficiency in the provision of water services. Water Resources Research, 29(6), 1573-1578. [CrossRef]

- Berg, S., & Lin, C. (2008). Consistency in performance rankings: the Peru water sector. Applied Economics, 40(6), 793-805. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Varela, M., de los Ángeles García-Valiñas, M., González-Gómez, F., & Picazo-Tadeo, A. J. (2017). Ownership and performance in water services revisited: does private management really outperform public?. Water Resources Management, 31, 2355-2373. [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Senante, M., & Sala-Garrido, R. (2015). The impact of privatization approaches on the productivity growth of the water industry: a case study of Chile. Environmental Science & Policy, 50, 166-179.

- Chakraborty, K., Biswas, B., & Lewis, W. C. (2001). Measurement of technical efficiency in public education: A stochastic and nonstochastic production function approach. Southern economic journal, 67(4), 889-905. [CrossRef]

- Rangan, N., Grabowski, R., Aly, H. Y., & Pasurka, C. (1988). The technical efficiency of US banks. Economics letters, 28(2), 169-175.

- Ferreira da Cruz, N., Marques, R. C., Romano, G., & Guerrini, A. (2012). Measuring the efficiency of water utilities: a cross-national comparison between Portugal and Italy. Water Policy, 14(5), 841-853. [CrossRef]

- Maddala, G. S. (1983). Limited-dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics (Vol. 149). Cambridge University Press.

- Deng, G., Li, L., & Song, Y. (2016). Provincial water use efficiency measurement and factor analysis in China: based on SBM-DEA model. Ecological Indicators, 69, 12-18.

- Abbott, M., & Cohen, B. (2009). Productivity and efficiency in the water industry. Utilities Policy , 17 (3-4), 233-244. [CrossRef]

- Faraia, R. C. D., Moreira, T. B. S., & Souza, G. S. (2005). Public versus private water utilities: empirical evidence for Brazilian companies. Economics Bulletin. https://ssrn.com/abstract=662421.

- Molinos-Senante, M., Sala-Garrido, R., & Lafuente, M. (2015). The role of environmental variables on the efficiency of water and sewerage companies: a case study of Chile. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22, 10242-10253. [CrossRef]

- Lannier, A. L., & Porcher, S. (2014). Efficiency in the public and private French water utilities: prospects for benchmarking. Applied Economics, 46(5), 556-572. [CrossRef]

- De la Higuera-Molina, E. J., Campos-Alba, C. M., López-Pérez, G., & Zafra-Gómez, J. L. (2023). Efficiency of water service management alternatives in Spain considering environmental factors. Utilities Policy, 84, 101644. [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I. M. (2006). Efficiency measurement in Spanish local government: the case of municipal water services. Review of Policy Research, 23(2), 355-372. [CrossRef]

- Goldar, B., Renganathan, V. S., & Banga, R. (2004). Ownership and efficiency in engineering firms: 1990-91 to 1999-2000. Economic and Political Weekly, 441-447. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4414577.

- Correia, T., & Marques, R. C. (2011). Performance of Portuguese water utilities: how do ownership, size, diversification and vertical integration relate to efficiency?. Water Policy, 13(3), 343-361.

- Setiawan, A. R., Gravitiani, E., & Rahardjo, M. (2021, April). Production cost efficiency analysis of regional water companies in eastern Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 724, No. 1, p. 012012). IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Anh, N. V., & Tran, H. H. T. (2020). Evaluation of performance indicators of selected water companies in Viet Nam. Vietnam Journal of Science and Technology, 58(5A), 42-53. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J., Li, W., Zhou, Y., Zhang, P., & Zhang, H. (2022). Impact of public service quality on the efficiency of the water industry: Evidence from 147 cities in China. Sustainability, 14(22), 15160. [CrossRef]

- Smithson, M., & Merkle, E. C. (2013). Generalized linear models for categorical and continuous limited dependent variables. CRC Press.

- Bennich, A., Engwall, M., & Nilsson, D. (2023). Operating in the shadowland: Why water utilities fail to manage decaying infrastructure. Utilities Policy, 82, 101557. [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Senante, M., Maziotis, A., Sala-Garrido, R., & Mocholi-Arce, M. (2023). Assesing the influence of environmental variables on the performance of water companies: An efficiency analysis tree approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 212, 118844. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

A list of input and output variables of the DEA study.

Table 1.

A list of input and output variables of the DEA study.

| Variable |

Definition |

| Total employees (EmplTotal). |

Represents the number of human resources assigned to the production and distribution of drinking water [89]. EmplTotal is used as input. |

| Total Cost (TotalCost). |

The variable TotalCost, which includes all operational costs of a water utility (energy, chemicals, maintenance, administration), is used as an input in the DEA to assess efficiency. The objective is to minimize these costs to achieve a given level of production and service [90]. |

| Total volume of drinking water (VolProd). |

It represents the total volume of potable water produced by a company, entering the output in the DEA efficiency assessment. This is further justified because production is maximized with the available resources, meaning that higher production with similar inputs highlights greater efficiency [91]. |

| Population served (PoblAtend) |

It represents the total number of people who receive drinking water service, it is an outcome used in the DEA to evaluate the efficiency of the result. It is necessary to maximize the coverage capacity in relation to the available resources: a greater number of people served with the same contribution indicates greater efficiency [92]. Several studies, including PoblAtend, have applied it as an indicator of canned service, social impact and overall capacity of the company on demand. |

Table 2.

Results of Descriptive Statistics of Input and Output Variables.

Table 2.

Results of Descriptive Statistics of Input and Output Variables.

| |

Max |

Min |

Standard Deviation (SD) |

Coefficient of variation (CV) |

| TotalEmployees (total employees) |

4,684.00 |

127.00 |

787.06 |

1.12 |

| CostTotal (total cost) |

$478,689,022.10 |

$935,663.00 |

85,065,234.75 |

1.28 |

| Vprod (Volume of drinking water production) |

8,501,117,672.79 |

52,474,136.00 |

1,306,895,758.27 |

1.70 |

| PobAtend (population served) |

4,957,280.00 |

105,201.00 |

931,248.79 |

1.36 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).