Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

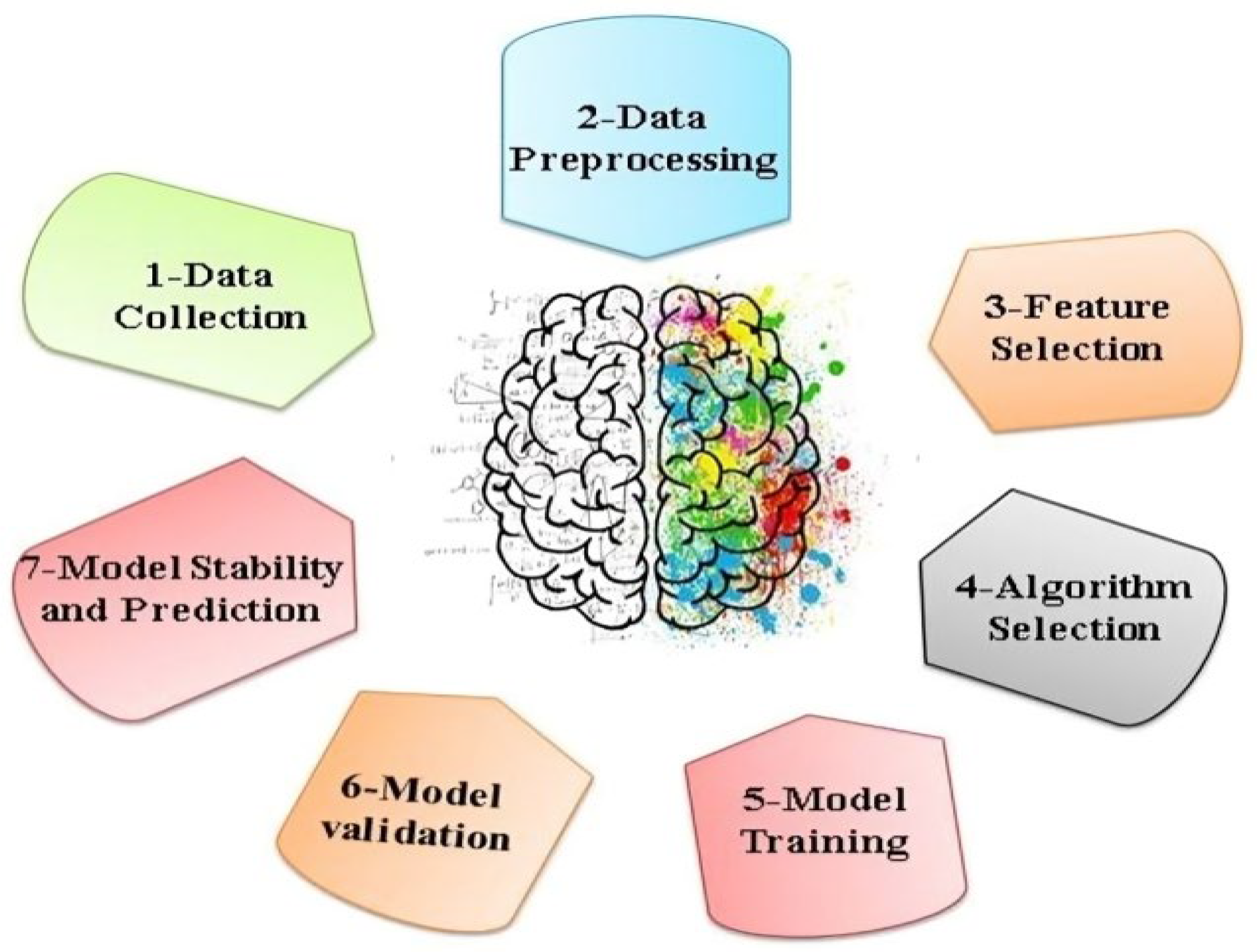

2. The ML Steps

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Feature Selection Methods

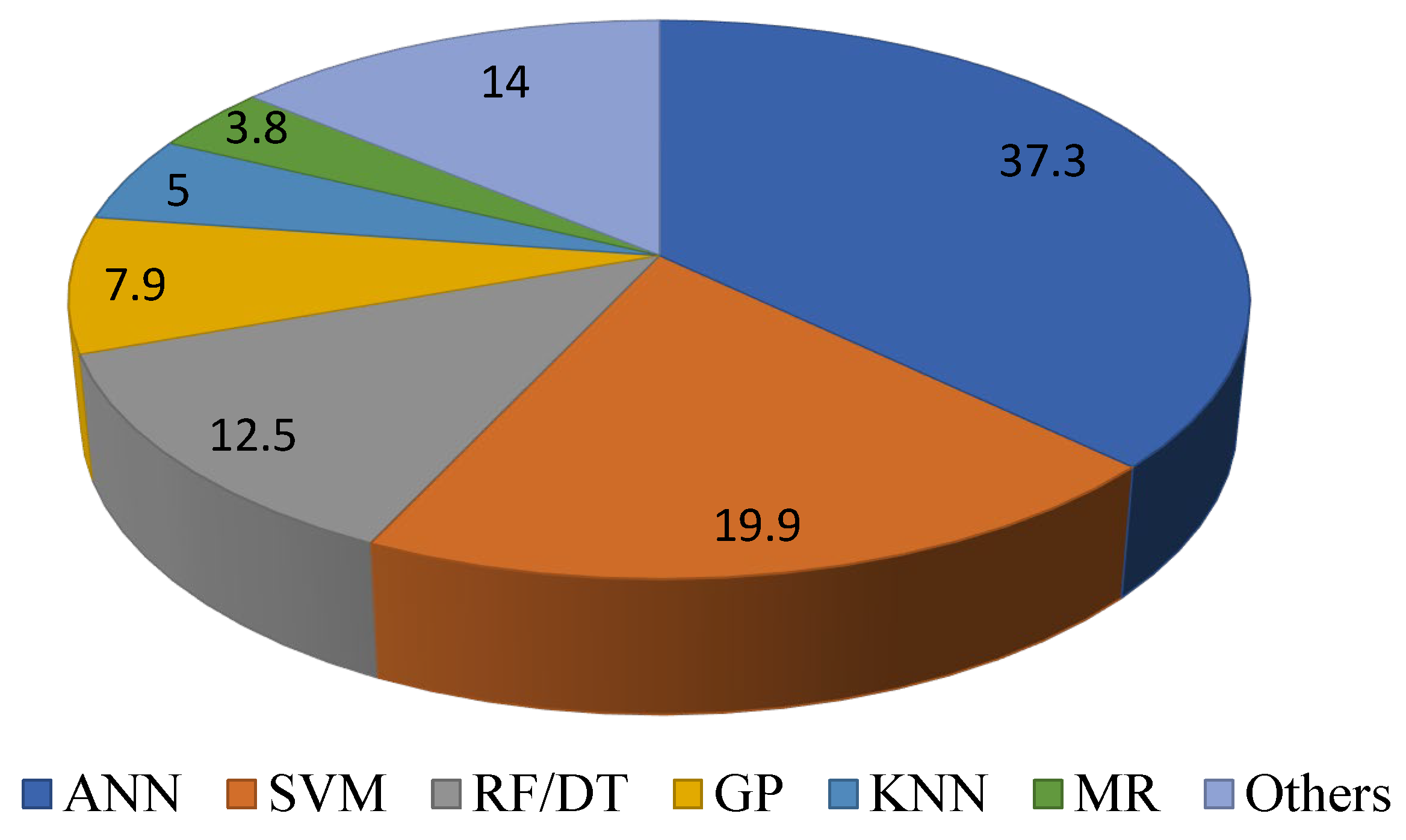

2.4. Algorithm Selection

2.5. Model Training and Data Pipeline

2.6. Model Validation

2.7. Model Stability and Prediction

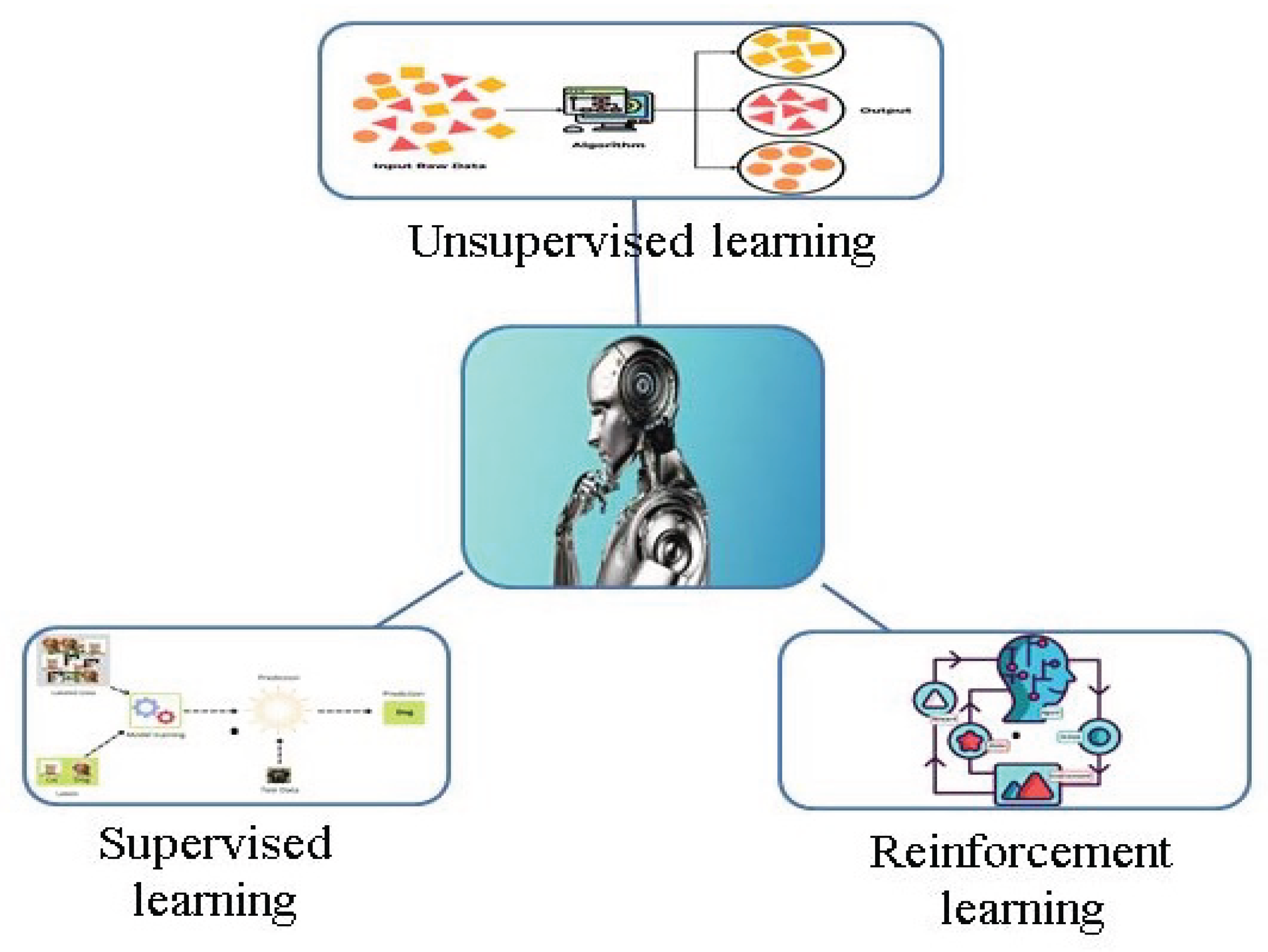

3. Type of the ML

- Data evaluation: Are data labeled or not?

- Specifying objectives: Is the topic repetitive and well-defined? Or is the algorithm needed to solve problems?

- Cycle through available algorithm options: Is there a suitable algorithm to create a model with the highest accuracy according to the data distribution?

- The big data classes can be a real challenge to monitor, but the results can also be very accurate and reliable. In contrast, large volumes of data can be managed in real time without supervision. However, there is a lack of clarity about the clustering method and the possibility of false results in this method [29].

3.1. Types of Supervised Learning Problems

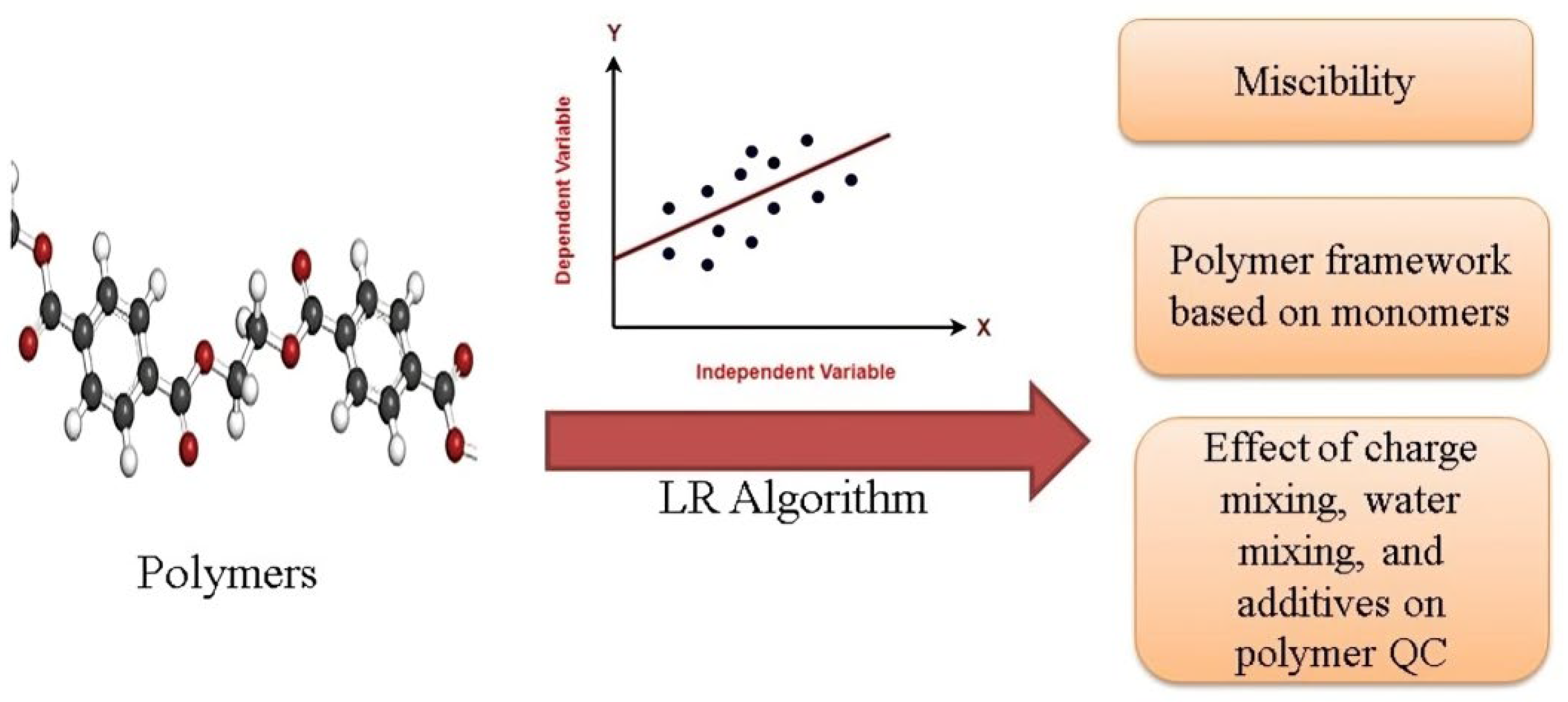

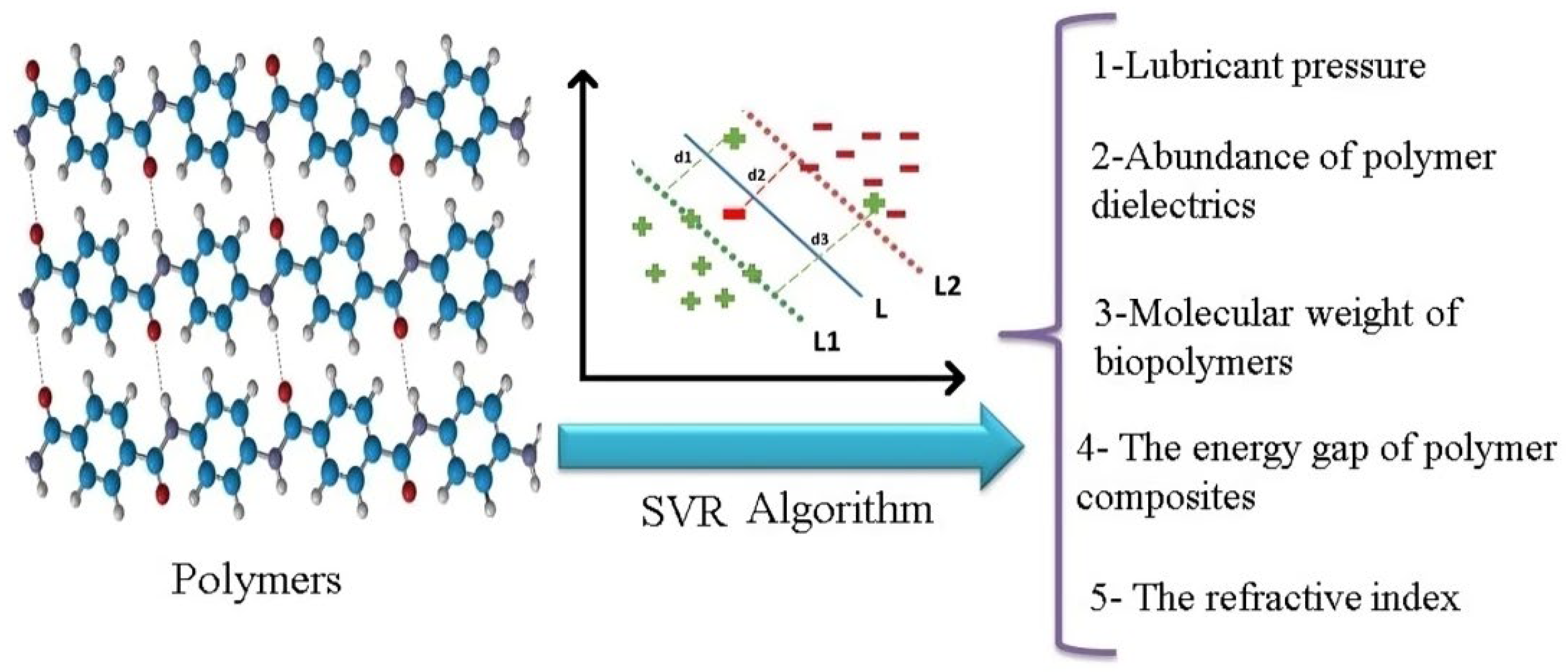

3.1.1. Regression Algorithms

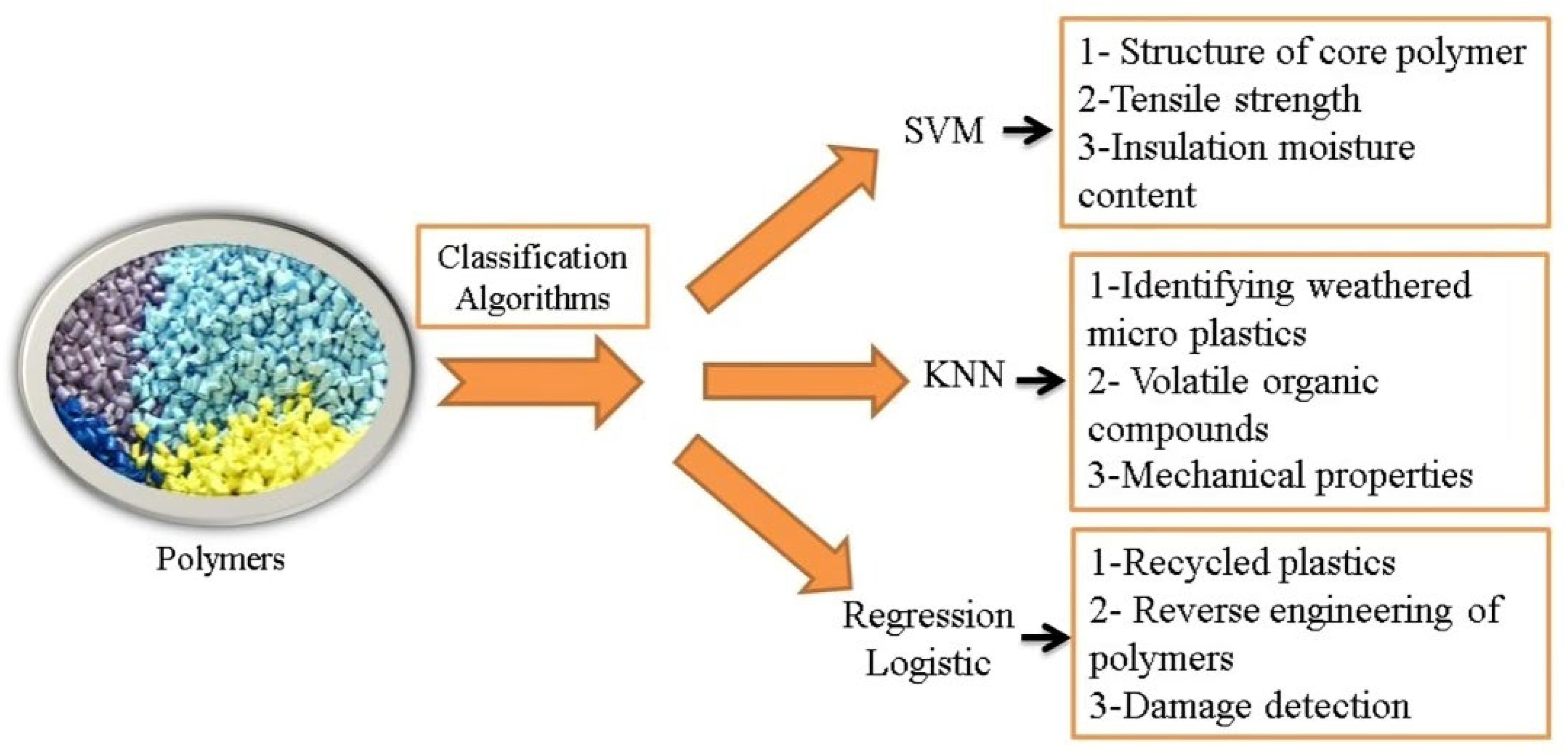

3.1.2. Classification Algorithms

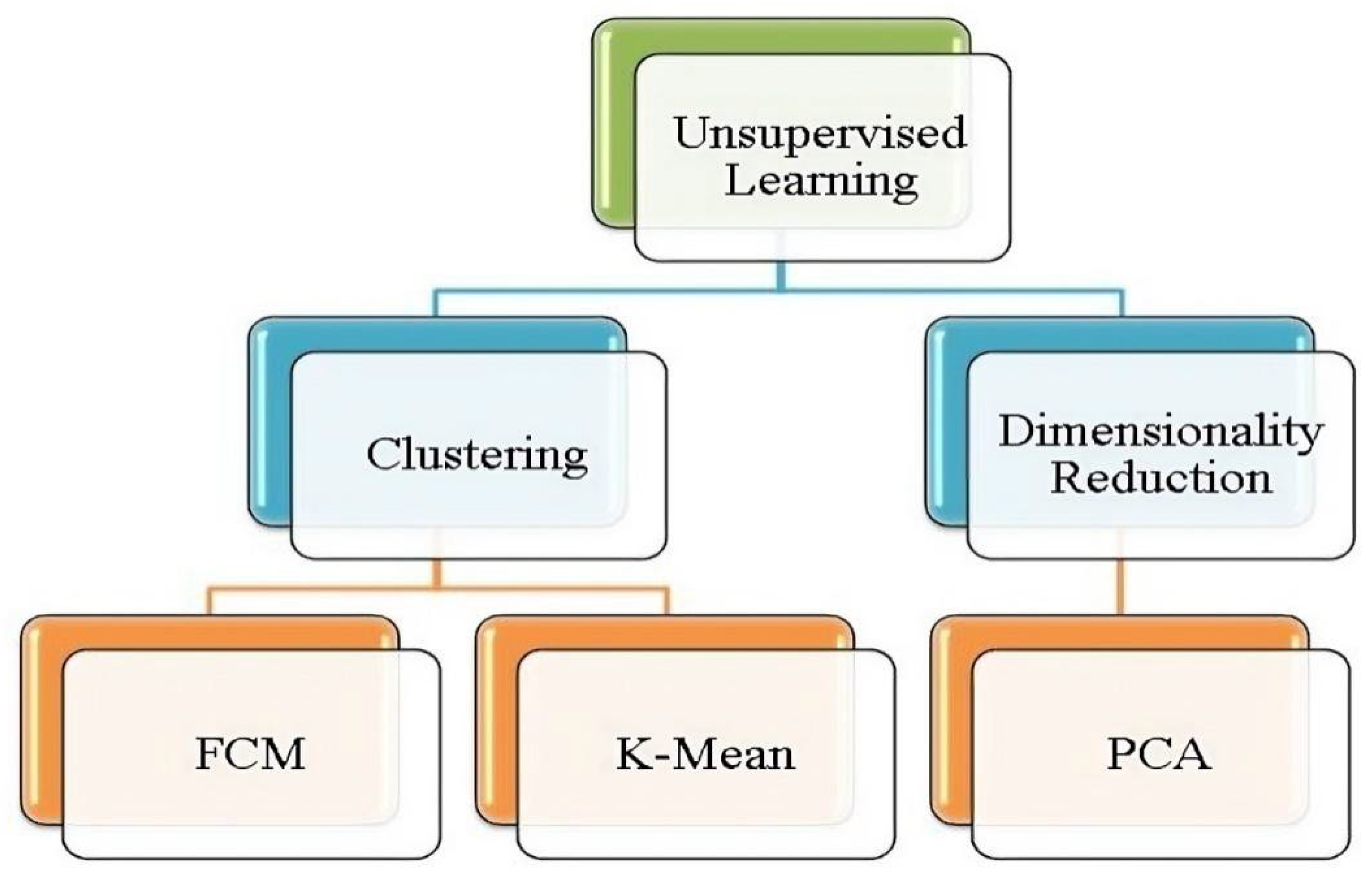

3.2. Unsupervised Learning

3.4. Ensemble Algorithms

4. Deep Learning

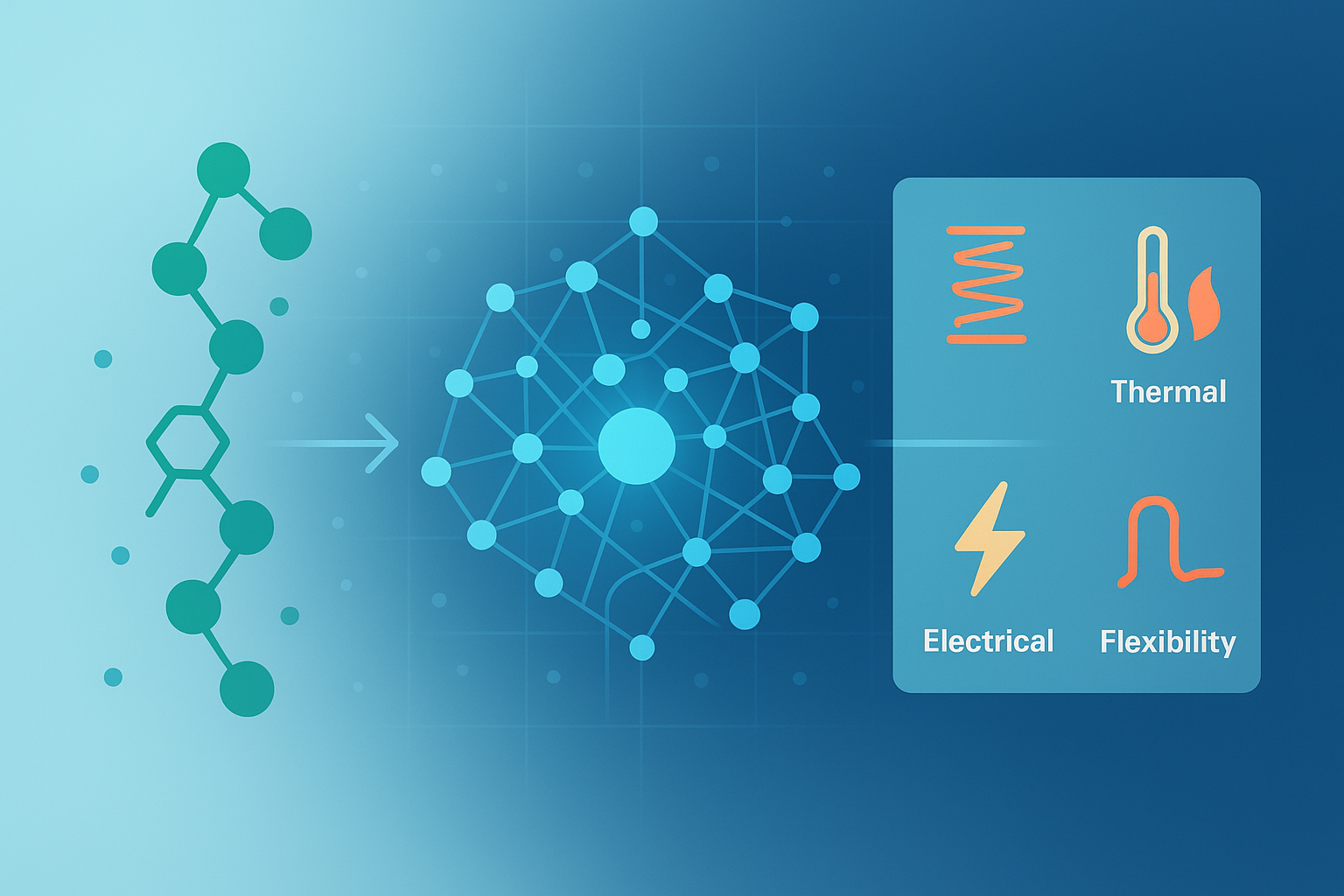

5. Examples of ML Applications in Polymer Development

Tires

D Printing of Composites

6. Advantages and Disadvantages

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jagadeesh, Praveenkumara, et al. A comprehensive review on polymer composites in railway applications. Polymer Composites 2022, 43, 1238–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritsema van Eck, Guido C. , Leonardo Chiappisi, and Sissi De Beer. "Fundamentals and applications of polymer brushes in air. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2022, 4, 3062–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Wuxin, et al. MLin polymer informatics. InfoMat 2021, 3, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Ruimin, and Tengfei Luo. "PI1M: a benchmark database for polymer informatics. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2020, 60, 4684–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama-Sato, Kan. "Recent advances and challenges in experiment-oriented polymer informatics. Polymer Journal 2023, 55, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, Anand, Chiho Kim, and Rampi Ramprasad. "Polymer genome: a polymer informatics platform to accelerate polymer discovery. Machine Learning Meets Quantum Physics, 2020; 397–412. [CrossRef]

- Schustik, Santiago A. , et al. Polymer informatics: Expert-in-the-loop in QSPR modeling of refractive index. Computational Materials Science. 2021, 194, 110460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, Harikrishna, et al. An informatics approach for designing conducting polymers. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 53314–53322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Roshan A. , Carlos H. Borca, and Michael A. Webb. "Featurization strategies for polymer sequence or composition design by machine learning. Molecular Systems Design & Engineering 2022, 7, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Jie, et al. Feature selection in machine learning: A new perspective. Neurocomputing 2018, 300, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, Massimo, et al. Machine Learning for industrial applications: A comprehensive literature review. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 175, 114820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikmukhametov, Timur, and Johannes Jäschke. "First principles and machine learning virtual flow metering: a literature review. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 184, 106487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antil SK, Antil P, Singh S, Kumar A, Pruncu CI. Artificial neural network and response surface methodology based analysis on solid particle erosion P. Pattnaik, A. Sharma, M. Choudhary et al. Materials Today: Proceedings 44 (2021) 4703–47084707 behavior of polymer matrix composites. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- V. Infante, JFA Madeira, R.B. Ruben, F. Moleiro, S.T. de Freitas, Characterization and optimization of hybrid carbon–glass epoxy composites under combined loading. J. Compos. Mater. 2019, 53, 2593–2605. [CrossRef]

- P.R. Pati, Prediction and wear performance of red brick dust filled glass–epoxy composites using neural networks. Int. J. Plast. Technol. 2019, 23, 253–260. [CrossRef]

- P. Antil, S. Singh, A. Manna, Analysis on effect of electroless coated SiC p on mechanical properties of polymer matrix composites. Part. Sci. Technol. 2019, 37, 791–798. [CrossRef]

- Baseer, Ahmed Abdul, D. V. Ravi Shankar, and M. Manzoor Hussain. "Interfacial and tensile properties of hybrid FRP composites using dnn structure with optimization model. Surface Review and Letters 2020, 27, 1950099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volovici, Victor, et al. Steps to avoid overuse and misuse of machine learning in clinical research. Nature Medicine 28, 1996-1999. [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, Hugo M. , A. W. Stannat, and Giulio Mecacci. "Machine learning against terrorism: how big data collection and analysis influences the privacy-security dilemma. Science and engineering ethics 2020, 26, 2975–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Shivani, and Atul Gupta. "Dealing with noise problem in machine learning data-sets: A systematic review. Procedia Computer Science 2019, 16, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, Mhd Hasan, et al. Machine learning techniques for ophthalmic data processing: a review. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2020, 24, 3338–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Pronab, et al. Efficient prediction of cardiovascular disease using machine learning algorithms with relief and LASSO feature selection techniques. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 19304–19326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Li, and Abdallah Shami. "On hyperparameter optimization of machine learning algorithms: Theory and practice. Neurocomputing 2020, 415, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, Iqbal H. "Machine learning: Algorithms, real-world applications and research directions. SN computer science 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Kate, and Trevor Paglen. "Excavating AI: The politics of images in machine learning training sets. Ai & Society 2021, 36, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, Davide, and Giuseppe Jurman. "The ABC recommendations for validation of supervised machine learning results in biomedical sciences. Frontiers in big Data 2022, 5, 979465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Jie, et al. A Survey on Self-supervised Learning: Algorithms, Applications, and Future Trends. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024,. [CrossRef]

- Watson, David S. "On the philosophy of unsupervised learning. Philosophy & Technology 2023, 36, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, Oyeniyi Akeem, Khmaies Ouahada, and Adnan M. Abu-Mahfouz. "A review of machine learning approaches to power system security and stability. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 113512–113531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, Jeevith, and Børge Rokseth. "Applications of machine learning methods for engineering risk assessment–A review. Safety science 2020, 122, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulud, Dastan, and Adnan M. Abdulazeez. "A review on linear regression comprehensive in machine learning. Journal of Applied Science and Technology Trends 2020, 1, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodi, Yaser, Mohammad Ghasemi, and Seyed Roohollah Mousavi. "Estimating the compressive strength of rectangular fiber reinforced polymer–confined columns using multilayer perceptron, radial basis function, and support vector regression methods. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites 2022, 41, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujeeun, Lakshmi Yaneesha, et al. Predictive modeling as a tool to assess polymer–polymer and polymer–drug interactions for tissue engineering applications. Macromolecular Research 2023, 31, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Jianxin, and Hao Yang. "Linear regression-based efficient SVM learning for large-scale classification. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2015, 26, 2357–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulud, Dastan, and Adnan M. Abdulazeez. "A review on linear regression comprehensive in machine learning. Journal of Applied Science and Technology Trends 2020, 1, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, Onur, et al. Prediction of CIELab data and wash fastness of nylon 6, 6 using artificial neural network and linear regression model. Fibers and Polymers 2008, 9, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QIU, Sai-bing, and T. A. N. G. Bo. "Application of mutiple linear regression analysis in polymer modified mortar quality control. 2nd International Conference on Electronic & Mechanical Engineering and Information Technology. Atlantis Press,2012. [CrossRef]

- Ido, Ryota, et al. A method for inferring polymers based on linear regression and integer programming. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2021, 2109, 02628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, Hamid, and Hessam Yazdani. "Plastics and sustainability in the same breath: Machine learning-assisted optimization of coarse-grained models for polyvinyl chloride as a common polymer in the built environment. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2022, 186, 106510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. L. et al. Prediction of plasticization pressure of polymeric membranes for CO2 removal from natural gas. Journal of Membrane Science 2015, 480, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Yong, Liming Wang, and Zhengying Chen. "Adaptive global kernel interval SVR-based machine learning for accelerated dielectric constant prediction of polymer-based dielectric energy storage. Renewable Energy 2021, 176, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugasamy, Senthil Kumar, et al. Comparison between artificial neural networks and support vector machine modeling for polycaprolactone synthesis via enzyme catalyzed polymerization. Process Integration and Optimization for Sustainability 2021, 5, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owolabi, Taoreed O. , and Mohd Amiruddin Abd Rahman. "Modeling the optical properties of a polyvinyl alcohol-based composite using a particle swarm optimized support vector regression algorithm. Polymers 2021, 13, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, Nadim, et al. A Systematic Literature Review on Contemporary and Future trends in Virtual Machine Scheduling Techniques in Cloud and Multi-Access Computing. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Amor, Nesrine, Muhammad Tayyab Noman, and Michal Petru. "Classification of textile polymer composites: Recent trends and challenges. Polymers 2021, 13, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koinig, G. , et al. Inline classification of polymer films using Machine learning methods. Waste Management 2024, 174, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Zhen, et al. Structure control classification and optimization model of hollow carbon nanosphere core polymer particle based on improved differential evolution support vector machine. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2013, 37, 7442–7451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarazi, Safwan, Rula Allaf, and Firas Alhindawi. "Machine learning models for predicting and classifying the tensile strength of polymeric films fabricated via different production processes. Materials 2019, 12, 1475. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yiyi, et al. Moisture prediction of transformer oil-immersed polymer insulation by applying a support vector machine combined with a genetic algorithm. Polymers 2020, 12, 1579. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Navarro, Javier, et al. Performance evaluation of classical classifiers and deep learning approaches for polymers classification based on hyperspectral images. Advances in Computational Intelligence: 16th International Work-Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, IWANN 2021, Virtual Event, June 16–18, 2021, Proceedings, Part II 16. Springer International Publishing, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Xin, Frederic Beén, and Patrick S. Bäuerlein. "Quantum cascade laser imaging (LDIR) and machine learning for the identification of environmentally exposed microplastics and polymers. Environmental Research 2022, 212, 113569. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Panchal, A. Phadke, U. Gopinathan and S. Datar, "Development of a Polymer Modified Quartz Tuning Fork (QTF) Sensor Array-Based Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Classifier. IEEE Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 20870–20877. [CrossRef]

- Dilbas, Hasan, et al. Mechanical performance improvement of super absorbent polymer-modified concrete. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102151. [CrossRef]

- Das, Abhik. "Logistic regression. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 1-2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Boateng, Ernest Yeboah, and Daniel A. Abaye. "A review of the logistic regression model with emphasis on medical research. Journal of data analysis and information processing 2019, 7, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Z. Development of an in-process Pokayoke system utilizing accelerometer and logistic regression modeling for monitoring injection molding flash. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2014, 71, 1793–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idolor, Ogheneovo, et al. Nondestructive examination of polymer composites by analysis of polymer-water interactions and damage-dependent hysteresis. Composite Structures 2022, 287, 115377. [CrossRef]

- Mairpady, Anusha, Abdel-Hamid I. Mourad, and Mohammad Sayem Mozumder. "Accelerated Discovery of the Polymer Blends for Cartilage Repair through Data-Mining Tools and Machine-Learning Algorithm. Polymers 2022, 14, 1802. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Xin, et al. Recognition of polymer configurations by unsupervised learning. Physical Review E 2019, 99, 043307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, Prabha, and R. D. S. Yadava. "Polymer selection for SAW sensor array based electronic noses by fuzzy c-means clustering of partition coefficients: Model studaies on detection of freshness and spoilage of milk and fish. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2015, 209, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Zhudan, et al. Unsupervised machine learning methods for polymer nanocomposites data via molecular dynamics simulation. Molecular Simulation 2020, 46, 1509–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Yun, et al. Industrial polymers classification using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy combined with self-organizing maps and K-means algorithm. Optik 2018, 165, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezer, Danijela. "Application of Cluster Analysis for Polymer Classification According to Mechanical Properties., https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0787-948X, (2021).

- Kurita, Hiroki, et al. k-Means Clustering for Prediction of Tensile Properties in Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Advanced Engineering Materials 2022, 24, 2101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamizadeh, Sasan, et al. An overview of principal component analysis. Journal of Signal and Information Processing 2013, 4, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiles, Melanie, Michael Grossutti, and John R. Dutcher. "Classifying formulations of crosslinked polyethylene pipe by applying machine-learning concepts to infrared spectra. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics 2019, 57, 1255–1262. [CrossRef]

- Lightstone, Jordan P., et al. Refractive index prediction models for polymers using machine learning. Journal of Applied Physics 2020, 127.21. 10.1063/5. 0008. [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, Rahul, et al. Prediction of the specific heat of polymers from experimental data and machine learning methods. Polymer 2021, 220, 123558. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Praveen, Linda S. Schadler, and Ravishankar Sundararaman. "Dielectric properties of polymer nanocomposite interphases from electrostatic force microscopy using machine learning. Materials Characterization 2021, 173, 110909. [CrossRef]

- D. Mienye and Y. Sun, "A Survey of Ensemble Learning: Concepts, Algorithms, Applications, and Prospects," in IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 2022, 99129-99149. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Liao J, Zheng Y, Chen Y, Liu H, Shi X. Random forest algorithm-enhanced dual-emission molecularly imprinted fluorescence sensing method for rapid detection of pretilachlor in fish and water samples. J Hazard Mater. Oct 5;439,129591, Epub 2022 Jul 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Wenyang, and Dongchu Sun. "The improved AdaBoost algorithms for imbalanced data classification. Information Sciences 2021, 563, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

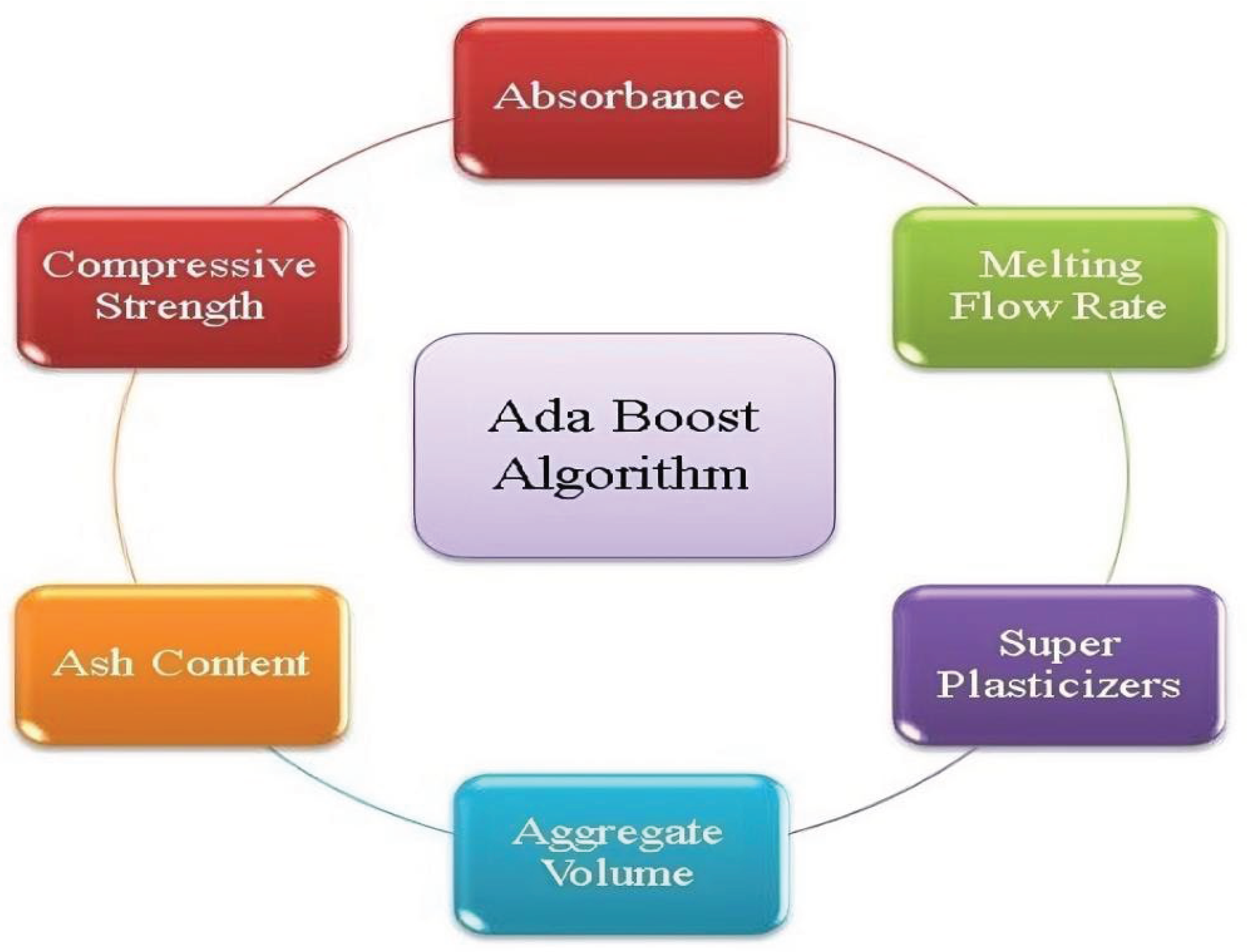

- Wang, Qichen, et al. Application of soft computing techniques to predict the strength of geopolymer composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Muhammad Nasir, et al. Use of artificial intelligence for predicting parameters of sustainable concrete and raw ingredient effects and interactions. Materials 2022, 15, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, Madiha, et al. Application of ensemble machine learning methods to estimate the compressive strength of fiber-reinforced nano-silica modified concrete. Polymers 2022, 14, 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledwani, D., I. Thakur, and V. Bhatnagar. "Comparative Analysis of Prediction Models for Melt Flow Rate of C2 and C3 Polymers Synthesized using Nanocatalysts. NanoWorld J 2022, 8, S123–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Wenjuan, Yutao Liu, and Dirk Söffker. "A novel adaptive boosting algorithm with distance-based weighted least square support vector machine and filter factor for carbon fiber reinforced polymer multi-damage classification. Structural Health Monitoring 2022, 22, 1273–1289. [CrossRef]

- Yarahmadi, Bita, Seyed Majid Hashemianzadeh, and Seyed Mohammad-Reza Milani Hosseini. "A new approach to prediction riboflavin absorbance using imprinted polymer and ensemble machine learning algorithms. Heliyon 2023, 9, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Shams Forruque, et al. Deep learning modelling techniques: current progress, applications, advantages, and challenges. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 13521–13617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

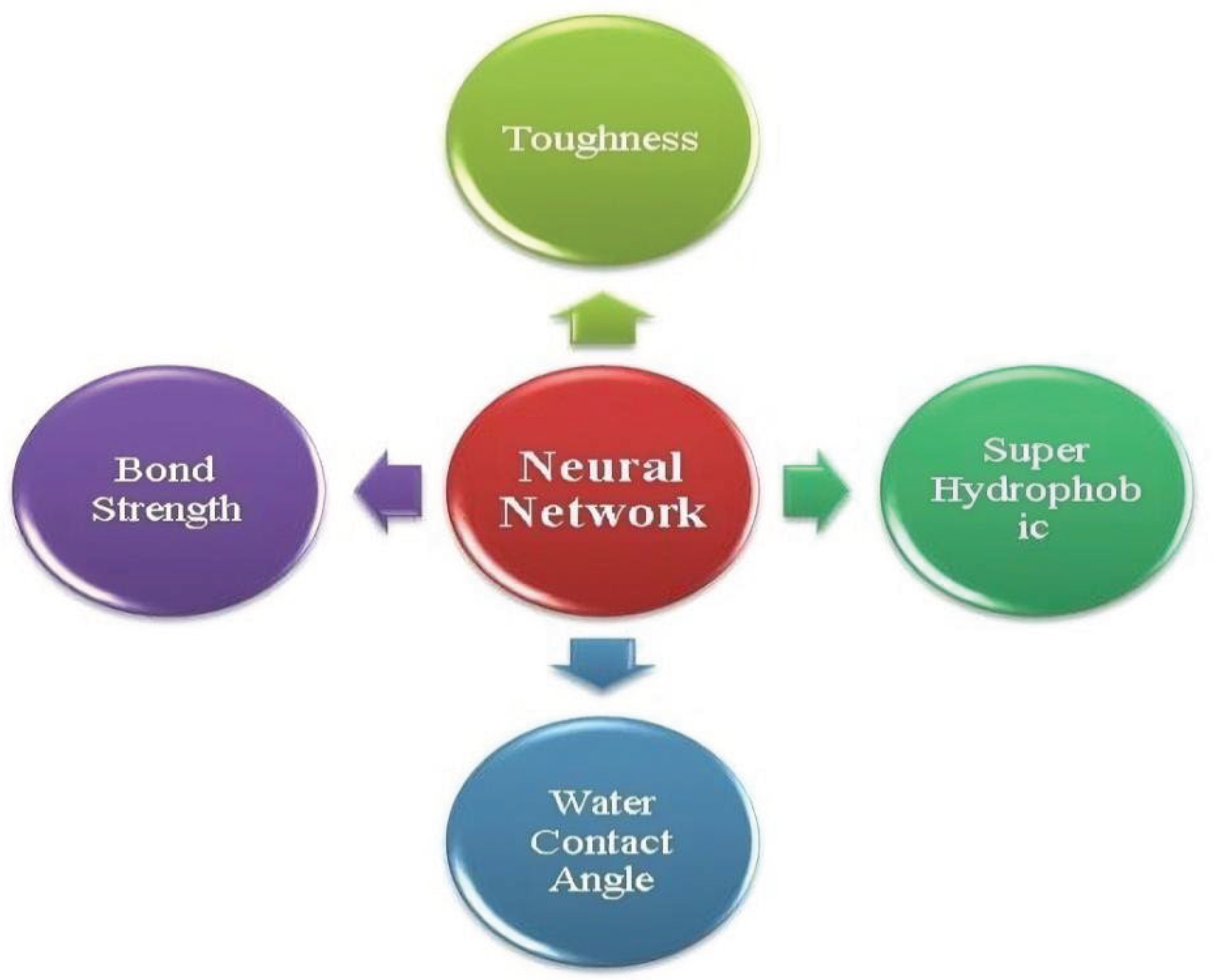

- Mengshan, Li, et al. Solubility prediction of gases in polymers based on an artificial neural network: a review. RSC advances 2017, 7, 35274–35282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Aanchna, and Vinod Kushvaha. "Predictive modelling of fracture behaviour in silica-filled polymer composite subjected to impact with varying loading rates using artificial neural network. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 2020, 239, 107328. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Qiang, et al. Superhydrophobic polymer topography design assisted by machine learning algorithms. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 30155–30164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Rami, and Madeleine Haddad. "Predicting fiber-reinforced polymer–concrete bond strength using artificial neural networks: A comparative analysis study. Structural Concrete 2021, 22, 38–49. [CrossRef]

- Amor, Nesrine, Muhammad Tayyab Noman, and Michal Petru. "Classification of textile polymer composites: recent trends and challenges. Polymers 2021, 13, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushik, Jayanth. "Understanding convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint, 1605. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Minggang, et al. Graph convolutional neural networks for polymers property prediction, 2018. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.06231. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Liyong, Wei Xie, and Yong Zhang. "Blister defect detection based on convolutional neural network for polymer lithium-ion battery. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 1085. [CrossRef]

- Miccio, Luis A. , and Gustavo A. Schwartz. "From chemical structure to quantitative polymer properties prediction through convolutional neural networks. Polymer 2020, 193, 122341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, Göksu, Ali Uysal, and Cafer Bal. A New Lithium Polymer Battery Dataset with Different Discharge Levels: SOC Estimation of Lithium Polymer Batteries with Different Convolutional Neural Network Models. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2023, 48, 6873–6888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z. , et al. (2025). Machine learning helps chemists develop tougher plastics. MIT News.

- Malashin, I. , et al. Boosting-Based Machine Learning Applications in Polymer Science. Polymers 2025, 17, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J. N, Li Qianxiao, Jun Ye. "Challenges and opportunities of polymer design with machine learning and high throughput experimentation. MRS Communications 2019, 9, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Junnan, Aaron C. Tan, and Peter F. Green. "Thermally induced chain orientation for improved thermal conductivity of P (VDF-TrFE) thin films. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Miccio, L. A, Schwartz G. A. From chemical structure to quantitative polymer properties prediction through convolutional neural networks. Polymer. 2020, 193, 122341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hongyu, et al. Thermal conductivity of polymer-based composites: Fundamentals and applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2016, 59, 41–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Carlos, and Joaquín Fernández-León. "A machine learning model to detect flow disturbances during manufacturing of composites by liquid moulding. Journal of Composites Science 2020, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassola, Stefano, et al. Machine learning for polymer composites process simulation–a review. Composites Part B: Engineering 2022, 246, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Qisong, et al. Synergizing machine learning, molecular simulation and experiment to develop polymer membranes for solvent recovery. Journal of Membrane Science 2023, 678, 121678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatle, Bill K. , et al. Design of polymer blend electrolytes through a machine learning approach. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 9449–9459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanorkar, Ritesh J. , Subhra Mohanty, and Virendra Kumar Gupta. "Synthesis of functionalized styrene butadiene rubber and its applications in SBR–silica composites for high performance tire applications. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2021, 60, 4517–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejna, Aleksander, et al. Waste tire rubber as low-cost and environmentally-friendly modifier in thermoset polymers–A review. Waste Management 2020, 108, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, Akarsh, et al. Processing and characterization analysis of pyrolyzed oil rubber (from waste tires)-epoxy polymer blend composite for lightweight structures and coatings applications. Polymer Engineering & Science 2019, 59, 2041–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Song, Jinlian Luo, and Youping Wu. "Properties prediction and design of tire tread composites using machine learning. Macromolecular Theory and Simulations 2020, 29, 1900063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Yusha, et al. Fuel composition forecasting for waste tires pyrolysis process based on machine learning methods. Fuel 2024, 362, 130789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, Sivaldo Leite, Denilso Palaoro, and Ana Maria Segadães. "Property optimisation of epdm rubber composites using mathematical and statistical strategies. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2017, 2017, 2730830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarian, N. , and M. Hamedi. "Optimization of rubber compound design process using artificial neural network and genetic algorithm. International Journal of Engineering 2020, 33, 2319–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saran, O. Sai, et al. 3D printing of composite materials: A short review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 64, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dananjaya, S. A. V. , et al. 3D printing of biodegradable polymers and their composites–Current state-of-the-art, properties, applications, and machine learning for potential future applications. Progress in Materials Science, 2024; 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkaria, V. , et al. (2024). A Machine Learning–Based Tire Life Prediction Framework for Increasing Life of Commercial Vehicle Tires. ASME Journal of Computing and Information Science in Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z. , et al. (2025). Machine learning helps reveal key factors affecting tire wear. Science of The Total Environment. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z. , et al. (2025). Machine learning-driven intelligent tire wear detection system. Computers in Industry. [CrossRef]

- Ferdousi, Sanjida, et al. Investigation of 3D printed lightweight hybrid composites via theoretical modeling and machine learning. Composites Part B: Engineering 2023, 265, 110958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, Neelam, Sheifali Gupta, and Sartajvir Singh. "A review paper on machine learning applications, advantages, and techniques. ECS Transactions 2022, 107, 6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Yu Guang, et al. Incorporating artificial intelligence in urology: Supervised machine learning algorithms demonstrate comparative advantage over nomograms in predicting biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy. The Prostate 2022, 82, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, Ch Anwar Ul, Muhammad Sufyan Khan, and Munam Ali Shah. "Comparison of machine learning algorithms in data classification. 24th International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC). IEEE. 2018.

- Jha, Khushi Kumari, et al. A brief comparison on machine learning algorithms based on various applications: a comprehensive survey. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Computation System and Information Technology for Sustainable Solutions (CSITSS). IEEE. 2021.

| Polymer Composites | Characterization | Optimization methods | Inputs | Outputs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass fiber polymer composites |

Erosion behavior |

Response surface methodology (RSM) and ANN |

Nozzle diameter, slurry pressure, impingement angle |

The rate of the erosion | 13 |

| Hybrid carbon–glass epoxy composites |

Mechanical behavior |

GLODS, ABAQUS | Ply fiber orientation | Displacement, Stress | 14 |

| Red brick dust- glass– epoxy composites |

Wear behavior |

ANN |

RBD content, velocity, impingement angle, erodent temperature, erodent size |

The flow of erosion | 15 |

| Silicon behavior carbide particle/glass fiber–reinforced Polymer matrix composites |

Machining behavior |

Evolutionary computing | Inter- electrode gap, voltage, electrolyte concentration, and duty factor |

The rate of material removal | 16 |

| Hybrid fiber reinforced polymer composites |

Tensile and inter-facial properties |

Deep Neural Network (DNN) oppositional based Firefly optimization (OFFO) |

Hybridization of the layer | Tensile, and failure strain, tensile strength, modulus |

17 |

| Name | Description | URL |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 3D structures of complex, nucleic acids, and proteins | http://www.wwpdb.org |

| PoLyInfo | different data needed for polymeric material design | https://polymer.nims.go.jp/ |

| Physical Properties of Polymers | physical properties and characterization techniques of polymers | G. Wignall, J. Mark, L.Mandelkern , K. Ngai, W. Graessley, E. Samulski, and J. Koenig |

| Nano Mine | An open-source data resource used in nanocomposites | An open-source data resource for nanocomposites |

| Carination | Computed and practical properties of materials | https://citrination.com/ |

| NMR Databases | NMR spectra of polymer | https://www.acdlabs.com/dbs/nmr_db |

| Material characteristic Database | Engineering material characteristic | https://www.makeitfrom.com/ |

| NIST Synthetic Polymer MALDIR Database | Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry on a broad variety of synthetic polymers | https://maldi/http://nist.gov/ |

| CROW Polymer characteristic Database | A multitude of polymer characteristic | http://polymerdatabase.com/ |

| Dataset | Input layers nodes | Hidden layer numbers | Output layer nodes |

Activation function | Loss function1 | Dataset size | Accuracy | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| polymers and them their solvents |

Two branches: Solvents and Polymers | Branch of solvent:2 Hidden Layers: 3 | Binary classification: Good Solvent/NonSolvent | PReLU | NR. | 4595 Test: 10% Training: 90% |

%93.8 | [92] |

| TC dataset for polymers | The list of integer identifiers of 250 | 1-3 Conv2., 1 pooling layer, 3FC3. Layers | The structure of molecules | NR |

RMSE5 and MAE6 | Training: 90% Test: 10% |

%94.79 | [93] |

| polymers and their Tg value | Binary Images of SMILES information | 2Conv layers, 1 Max Pooling, 1 FC | one neuron | ReLU | Median relative error | Train/test: 75/25 80/20 90/10 |

%94 | [94] |

| dataset of the polymer genome project | two-dimensional graph | 2Conv, 1 Pooling Layer |

physical properties of polymers | The non-linear convolution functions | MAE | 1073 Polymers Training:60% Validation:20% test:20% |

MAE: 0.24 | [95] |

| pressure probes footprint pictures | 100*9 pictures | 2Conv/2Max Pooling/3 FC | Five nodes | ReLU | MSE | 3000 Images Train/test: 80%/20% |

%99 | [96] |

| Inputs | Algorithms | Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Dwelling time, furnace temperature, tension applied to strands | ANN | final properties of carbon fibers |

| Reactor temperature /pressure, liquid level and flow rate of catalyst | DBN | Monomer converting, average of molecular weight, Reaction time, dispersion and heat stability |

| temperature, feed rate, reaction time and catalyst amount | SVM | Viscosity |

| Injection speed / pressure, duration of pressure, mold temperature, time Coolant, injection amount, screw rotation speed, body pressure, body temperature |

ANN، GP, SVR | Process factors, fiber direction distribution, physical properties/ Mechanical, surface roughness |

| Feed rate, hydrogen concentration, and reaction temperature | PCA + GP | Prepare conditions and item quality |

| Material and operation factors (rotation speed, flow speed). output, temperature and composition |

ANN، sPGDSVM، C2V, iDMD |

properties and execution (Young's modulus, abdicate stretch, push) |

| process factors (position, contraction angle, polymer, channel width, and solvent flow |

GP | Product characteristics (average length, average diameter, etc.) |

| Reaction conditions (temperature and initiator concentration) | ANN | Average molecular weight, monomer conversion, and viscosity Reaction mass |

| ML algorithm | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Linear regression | Simple method | Ignore of non-linear linkage between properties and descriptors |

| SVM, KRR | Cost-effective | The number of attributes and the size of the kernel matrix quadratically, resulting in large errors for huge datasets. |

| GPR | It predicts uncertainty for objective values | It requires a manageable data size and cannot train multiple features in a model |

| RF | This criterion has a specific measure for evaluating each descriptor and predicts large datasets with high accuracy. | It is possible that an overfitting problem will arise due to the generation of overly complex trees |

| ANN | It has a great ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships from huge data sets. | It cannot be interpreted, requires more data to train, and is time-consuming. |

| Deep neural network | Suitable for graphic representation of materials, learning different levels of abstraction levels | It cannot be interpreted, is time-consuming, and requires more data to train. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).