Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

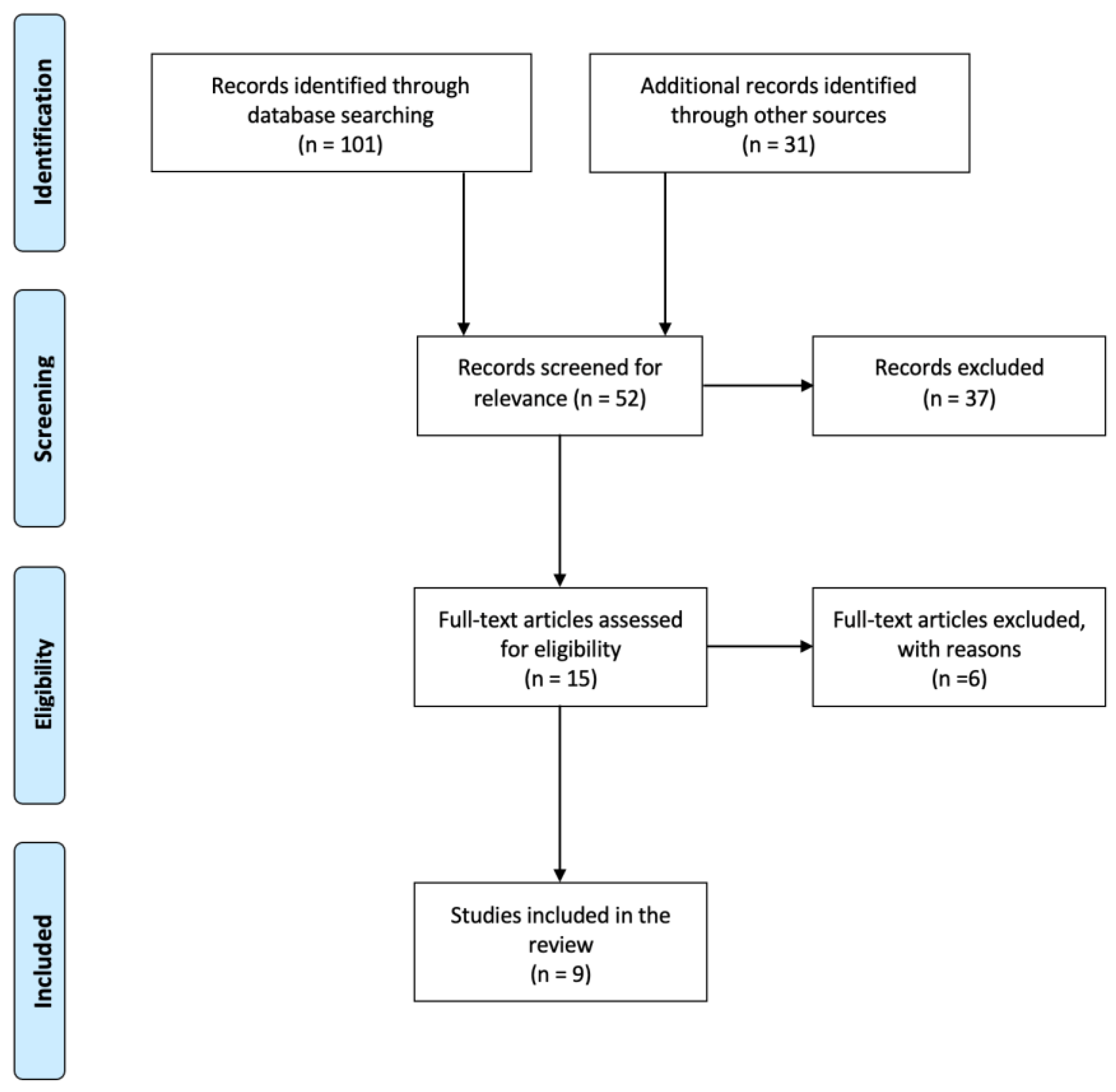

II. Methods

| Reference | Year | Study Design | No. of participants | Age of participants (mean and SD) |

No. of controls | Age of controls (mean and SD) |

Cytokines | Research Focus | Confounding Factor controlled |

| Skibinska et al. [32] | 2022 | Longitudinal | 25 | 18.28 (±2.82) | 31 | 21.1 (±2.76) | IL-8, TNF-α | Examined defensive mechanisms and cytokines | Age, gender |

| Goldstein et al. [33] | 2015 | Longitudinal | 123 | 20.4 (±3.8) | N/A | N/A | IL-6, TNF-α | Examined pro-inflammatory markers in lifetime characteristics, clinical characteristics, and metabolic syndrome variables | N/A |

| Goldstein et al. [34] | 2011 | Longitudinal | 30 | 15.5 (±2.3) | N/A | N/A | IL-6 | Examined bipolar subtypes and pro-inflammatory markers | N/A |

| Bai et al. [35] | 2024 | Longitudinal | 21 | 12-17 | 69 | 12-17 | TNF-α | Examined suicidal symptom severity and proinflammatory cytokines | Suicide severity, age, sex, BMI, education years, non-suicidal depressive symptoms |

| Karthikeyan et al. [36] | 2022 | Prospective repeated-measures study | 43 | 17.27 (±1.51) | 36 | 17.09 (±1.68) | IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α | Examined inflammatory markers as predictors of future mood symptoms and time for recovery | Age, sex, SES, BMI |

| Miklowitz et al. [37] | 2016 | Cross-sectional | 18 | 16.0 (±2.1) | 20 | 16.6 (±2.2) | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α | Examined systemic and cellular markers of inflammation in BD patients | N/A |

| Terczynska et al. [38] | 2025 | Longitudinal | 24 | 18.95 (±3.52) | N/A | N/A | TNF-α, IL-8 | Examined cytokines with temperament and character dimensions | N/A |

| Pearlstein et al. [39] | 2020 | Longitudinal | 25 | 15.03 (±1.90) | N/A | N/A | IL-6, IL-12, IL-1β, TNF-α | Examined the changes in cytokine levels between pre- and post-cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) | N/A |

| Hatch et al. [40] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | 40 | 17.41 (±1.64) | 20 | 16.06 (±1.67) | IL-6, TNF-α | Examined the link between cytokine levels in BD patients and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk | Age, BMI |

- 1)

- IL-6

- 2)

- IL-8

- 3)

- TNF-α

- 4)

- IL-10

- 5)

- IL-1β

IV. Discussion

V. Conclusion

References

- Digiovanni, A., Ajdinaj, P., Russo, M., Sensi, S. L., Onofrj, M., & Thomas, A. (2022). Bipolar spectrum disorders in neurologic disorders. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 1046471. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders : DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; (2013). 947 p.

- Waraich P, Goldner EM, Somers JM, Hsu L. Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. (2004) 49:124–38. [CrossRef]

- Birmaher, B. (2013), Bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Ment Health, 18: 140-148.

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, et al. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2006) 63:175–83. [CrossRef]

- Bolton, S., Warner, J., Harriss, E., Geddes, J., & Saunders, K. E. A. (2021). Bipolar disorder: Trimodal age-at-onset distribution. Bipolar disorders, 23(4), 341–356.

- Foulkes, L., & Blakemore, S. J. (2018). Studying individual differences in human adolescent brain development. Nature neuroscience, 21(3), 315–323. [CrossRef]

- Bombin, I., Mayoral, M., Castro-Fornieles, J., Gonzalez-Pinto, A., de la Serna, E., Rapado-Castro, M., Barbeito, S., Parellada, M., Baeza, I., Graell, M., Payá, B., & Arango, C. (2013). Neuropsychological evidence for abnormal neurodevelopment associated with early-onset psychoses. Psychological medicine, 43(4), 757–768. [CrossRef]

- Polderman, T. J., Benyamin, B., de Leeuw, C. A., Sullivan, P. F., van Bochoven, A., Visscher, P. M., & Posthuma, D. (2015). Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nature genetics, 47(7), 702–709. [CrossRef]

- O'Connell, K. S., & Coombes, B. J. (2021). Genetic contributions to bipolar disorder: current status and future directions. Psychological medicine, 51(13), 2156–2167. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Melbye M, Mors O, Ewald H. Individual and familial risk factors for bipolar affective disorders in Denmark. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1209–1215. [CrossRef]

- Arango, C., Dragioti, E., Solmi, M., Cortese, S., Domschke, K., Murray, R. M., Jones, P. B., Uher, R., Carvalho, A. F., Reichenberg, A., Shin, J. I., Andreassen, O. A., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2021). Risk and protective factors for mental disorders beyond genetics: an evidence-based atlas. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 20(3), 417–436. [CrossRef]

- McGowan, P.O., Kato, T. Epigenetics in mood disorders. Environ Health Prev Med 13, 16–24 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Dudek, D., Siwek, M., Zielińska, D., Jaeschke, R., & Rybakowski, J. (2013). Diagnostic conversions from major depressive disorder into bipolar disorder in an outpatient setting: results of a retrospective chart review. Journal of affective disorders, 144(1-2), 112–115. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B. I., Collinger, K. A., Lotrich, F., Marsland, A. L., Gill, M. K., Axelson, D. A., & Birmaher, B. (2011). Preliminary findings regarding proinflammatory markers and brain-derived neurotrophic factor among adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology, 21(5), 479–484. [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454, 428–435 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Dantzer, R., O'Connor, J., Freund, G. et al. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 9, 46–56 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Allan, S., Rothwell, N. Cytokines and acute neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci 2, 734–744 (2001).

- Uzzan, S., & Azab, A. N. (2021). Anti-TNF-α Compounds as a Treatment for Depression. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 26(8), 2368. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, T. D., Chung, Y., He, G., Sun, D., Jacobson, A., van Erp, T. G., McEwen, S., Addington, J., Bearden, C. E., Cadenhead, K., Cornblatt, B., Mathalon, D. H., McGlashan, T., Perkins, D., Jeffries, C., Seidman, L. J., Tsuang, M., Walker, E., Woods, S. W., Heinssen, R., … North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study Consortium (2015). Progressive reduction in cortical thickness as psychosis develops: a multisite longitudinal neuroimaging study of youth at elevated clinical risk. Biological psychiatry, 77(2), 147–157. [CrossRef]

- Kummer, K. K., Zeidler, M., Kalpachidou, T., & Kress, M. (2021). Role of IL-6 in the regulation of neuronal development, survival and function. Cytokine, 144, 155582. [CrossRef]

- Mondelli, V., Cattaneo, A., Murri, M. B., Di Forti, M., Handley, R., Hepgul, N., Miorelli, A., Navari, S., Papadopoulos, A. S., Aitchison, K. J., Morgan, C., Murray, R. M., Dazzan, P., & Pariante, C. M. (2011). Stress and inflammation reduce brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in first-episode psychosis: a pathway to smaller hippocampal volume. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 72(12), 1677–1684.

- Ghafelehbashi, H., Pahlevan Kakhki, M., Kular, L., Moghbelinejad, S., & Ghafelehbashi, S. H. (2017). Decreased Expression of IFNG-AS1, IFNG and IL-1B Inflammatory Genes in Medicated Schizophrenia and Bipolar Patients. Scandinavian journal of immunology, 86(6), 479–485.

- Rossi, S., Sacchetti, L., Napolitano, F., De Chiara, V., Motta, C., Studer, V., Musella, A., Barbieri, F., Bari, M., Bernardi, G., Maccarrone, M., Usiello, A., & Centonze, D. (2012). Interleukin-1β causes anxiety by interacting with the endocannabinoid system. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 32(40), 13896–13905. [CrossRef]

- Fillman, S. G., Weickert, T. W., Lenroot, R. K., Catts, S. V., Bruggemann, J. M., Catts, V. S., & Weickert, C. S. (2016). Elevated peripheral cytokines characterize a subgroup of people with schizophrenia displaying poor verbal fluency and reduced Broca's area volume. Molecular psychiatry, 21(8), 1090–1098. [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S. S., & Cheng, G. (2012). Role of interleukin 10 transcriptional regulation in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Critical reviews in immunology, 32(1), 23–63. [CrossRef]

- Porro, C., Cianciulli, A., & Panaro, M. A. (2020). The Regulatory Role of IL-10 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules, 10(7), 1017. [CrossRef]

- Tsai S. J. (2021). Role of interleukin 8 in depression and other psychiatric disorders. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 106, 110173.

- Fernandes, B. S., Steiner, J., Molendijk, M. L., Dodd, S., Nardin, P., Gonçalves, C. A., Jacka, F., Köhler, C. A., Karmakar, C., Carvalho, A. F., & Berk, M. (2016). C-reactive protein concentrations across the mood spectrum in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet. Psychiatry, 3(12), 1147–1156. [CrossRef]

- Sayana, P., Colpo, G. D., Simões, L. R., Giridharan, V. V., Teixeira, A. L., Quevedo, J., & Barichello, T. (2017). A systematic review of evidence for the role of inflammatory biomarkers in bipolar patients. Journal of psychiatric research, 92, 160–182. [CrossRef]

- Elsässer-Beile, U., Dursunoglu, B., Gallati, H., Mönting, J. S., & von Kleist, S. (1995). Comparison of cytokine production in blood cell cultures of healthy children and adults. Pediatric allergy and immunology : official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 6(3), 170–174. [CrossRef]

- Skibinska, M., Rajewska-Rager, A., Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M., Kapelski, P., Lepczynska, N., Kaczmarek, M., & Pawlak, J. (2022). Interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in youth with mood disorders-A longitudinal study. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 964538. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B. I., Lotrich, F., Axelson, D. A., Gill, M. K., Hower, H., Goldstein, T. R., Fan, J., Yen, S., Diler, R., Dickstein, D., Strober, M. A., Iyengar, S., Ryan, N. D., Keller, M. B., & Birmaher, B. (2015). Inflammatory markers among adolescents and young adults with bipolar spectrum disorders. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 76(11), 1556–1563. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B. I., Collinger, K. A., Lotrich, F., Marsland, A. L., Gill, M. K., Axelson, D. A., & Birmaher, B. (2011). Preliminary findings regarding proinflammatory markers and brain-derived neurotrophic factor among adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology, 21(5), 479–484. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y. M., Chen, M. H., Hsu, J. W., Huang, H. H., Jeng, J. S., & Tsai, S. J. (2024). Distinct Effects of Major Affective Disorder Diagnoses and Suicidal Symptom Severity on Inhibitory Control Function and Proinflammatory Cytokines: Single-Site Analysis of 800 Adolescents and Adults. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 27(10), pyae043. [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, S., Dimick, M. K., Fiksenbaum, L., Jeong, H., Birmaher, B., Kennedy, J. L., Lanctôt, K., Levitt, A. J., Miller, G. E., Schaffer, A., Young, L. T., Youngstrom, E. A., Andreazza, A. C., & Goldstein, B. I. (2022). Inflammatory markers, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and the symptomatic course of adolescent bipolar disorder: A prospective repeated-measures study. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 100, 278–286. [CrossRef]

- Miklowitz, D. J., Portnoff, L. C., Armstrong, C. C., Keenan-Miller, D., Breen, E. C., Muscatell, K. A., Eisenberger, N. I., & Irwin, M. R. (2016). Inflammatory cytokines and nuclear factor-kappa B activation in adolescents with bipolar and major depressive disorders. Psychiatry research, 241, 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Terczynska, M., Bargiel, W., Grabarczyk, M., Kozlowski, T., Zakowicz, P., Bojarski, D., Wasicka-Przewozna, K., Kapelski, P., Rajewska-Rager, A., & Skibinska, M. (2025). Circulating Growth Factors and Cytokines Correlate with Temperament and Character Dimensions in Adolescents with Mood Disorders. Brain sciences, 15(2), 121. [CrossRef]

- Pearlstein, J. G., Staudenmaier, P. J., West, A. E., Geraghty, S., & Cosgrove, V. E. (2020). Immune response to stress induction as a predictor of cognitive-behavioral therapy outcomes in adolescent mood disorders: A pilot study. Journal of psychiatric research, 120, 56–63. [CrossRef]

- Hatch, J. K., Scola, G., Olowoyeye, O., Collins, J. E., Andreazza, A. C., Moody, A., Levitt, A. J., Strauss, B. H., Lanctot, K. L., & Goldstein, B. I. (2017). Inflammatory Markers and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor as Potential Bridges Linking Bipolar Disorder and Cardiovascular Risk Among Adolescents. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 78(3), e286–e293. [CrossRef]

- Kummer, K. K., Zeidler, M., Kalpachidou, T., & Kress, M. (2021). Role of IL-6 in the regulation of neuronal development, survival and function. Cytokine, 144, 155582. [CrossRef]

- Lagzdina, R., Rumaka, M., Gersone, G., & Tretjakovs, P. (2023). Circulating Levels of IL-8 and MCP-1 in Healthy Adults: Changes after an Acute Aerobic Exercise and Association with Body Composition and Energy Metabolism. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(19), 14725. [CrossRef]

- Elhaik, E., & Zandi, P. (2015). Dysregulation of the NF-κB pathway as a potential inducer of bipolar disorder. Journal of psychiatric research, 70, 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B. I., Kemp, D. E., Soczynska, J. K., & McIntyre, R. S. (2009). Inflammation and the phenomenology, pathophysiology, comorbidity, and treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of the literature. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 70(8), 1078–1090.

- Uzzan, S., & Azab, A. N. (2021). Anti-TNF-α Compounds as a Treatment for Depression. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 26(8), 2368. [CrossRef]

- Sugino, H., Futamura, T., Mitsumoto, Y., Maeda, K., & Marunaka, Y. (2009). Atypical antipsychotics suppress production of proinflammatory cytokines and up-regulate interleukin-10 in lipopolysaccharide-treated mice. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 33(2), 303–307. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J. W., Lirng, J. F., Wang, S. J., Lin, C. L., Yang, K. C., Liao, M. H., & Chou, Y. H. (2014). Association of thalamic serotonin transporter and interleukin-10 in bipolar I disorder: a SPECT study. Bipolar disorders, 16(3), 241–248. [CrossRef]

- Kunz, M., Ceresér, K. M., Goi, P. D., Fries, G. R., Teixeira, A. L., Fernandes, B. S., Belmonte-de-Abreu, P. S., Kauer-Sant'Anna, M., Kapczinski, F., & Gama, C. S. (2011). Serum levels of IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: differences in pro- and anti-inflammatory balance. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil : 1999), 33(3), 268–274.

- Remlinger-Molenda, A., Wojciak, P., Michalak, M., Karczewski, J., & Rybakowski, J. K. (2012). Selected cytokine profiles during remission in bipolar patients. Neuropsychobiology, 66(3), 193–198. [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, H. R., Hosseini, R., Bijani, A., Akhavan-Niaki, H., Parsian, H., Pouramir, M., Saravi, M., Bagherzadeh, M., Mosapour, A., Saleh-Moghaddam, M., Rajabian, M., Golpour, M., & Mostafazadeh, A. (2019). Interleukin 10, lipid profile, vitamin D, selenium, metabolic syndrome, and serum antioxidant capacity in elderly people with and without cardiovascular disease: Amirkola health and ageing project cohort-based study. ARYA atherosclerosis, 15(5), 233–240. [CrossRef]

- Schlaak, J. F., Schmitt, E., Hüls, C., Meyer zum Büschenfelde, K. H., & Fleischer, B. (1994). A sensitive and specific bioassay for the detection of human interleukin-10. Journal of immunological methods, 168(1), 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Wiener, C. D., Moreira, F. P., Portela, L. V., Strogulski, N. R., Lara, D. R., da Silva, R. A., Souza, L. D. M., Jansen, K., & Oses, J. P. (2019). Interleukin-6 and Interleukin-10 in mood disorders: A population-based study. Psychiatry research, 273, 685–689. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. J., Davis, S., Morris, C., Jackson, E., Harrison, R., & O'Brien, J. T. (2005). Increase in interleukin-1beta in late-life depression. The American journal of psychiatry, 162(1), 175–177. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K. T., Deak, T., Owens, S. M., Kohno, T., Fleshner, M., Watkins, L. R., & Maier, S. F. (1998). Exposure to acute stress induces brain interleukin-1beta protein in the rat. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 18(6), 2239–2246. [CrossRef]

- Katoh-Semba, R., Wakako, R., Komori, T., Shigemi, H., Miyazaki, N., Ito, H., Kumagai, T., Tsuzuki, M., Shigemi, K., Yoshida, F., & Nakayama, A. (2007). Age-related changes in BDNF protein levels in human serum: differences between autism cases and normal controls. International journal of developmental neuroscience : the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience, 25(6), 367–372. [CrossRef]

- Lommatzsch, M., Zingler, D., Schuhbaeck, K., Schloetcke, K., Zingler, C., Schuff-Werner, P., & Virchow, J. C. (2005). The impact of age, weight and gender on BDNF levels in human platelets and plasma. Neurobiology of aging, 26(1), 115–123.

- Taurines, R., Segura, M., Schecklmann, M., Albantakis, L., Grünblatt, E., Walitza, S., Jans, T., Lyttwin, B., Haberhausen, M., Theisen, F. M., Martin, B., Briegel, W., Thome, J., Schwenck, C., Romanos, M., & Gerlach, M. (2014). Altered peripheral BDNF mRNA expression and BDNF protein concentrations in blood of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996), 121(9), 1117–1128. [CrossRef]

- Landry, A., Docherty, P., Ouellette, S., & Cartier, L. J. (2017). Causes and outcomes of markedly elevated C-reactive protein levels. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien, 63(6), e316–e323.

- Lovell, D. J., Giannini, E. H., Reiff, A., Cawkwell, G. D., Silverman, E. D., Nocton, J. J., Stein, L. D., Gedalia, A., Ilowite, N. T., Wallace, C. A., Whitmore, J., & Finck, B. K. (2000). Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. The New England journal of medicine, 342(11), 763–769. [CrossRef]

- Imhof, A., Froehlich, M., Brenner, H., Boeing, H., Pepys, M. B., & Koenig, W. (2001). Effect of alcohol consumption on systemic markers of inflammation. Lancet (London, England), 357(9258), 763–767. [CrossRef]

- Pacifici, R., Zuccaro, P., Pichini, S., Roset, P. N., Poudevida, S., Farré, M., Segura, J., & De la Torre, R. (2003). Modulation of the immune system in cannabis users. JAMA, 289(15), 1929–1931. [CrossRef]

- Hope, S., Melle, I., Aukrust, P., Steen, N. E., Birkenaes, A. B., Lorentzen, S., Agartz, I., Ueland, T., & Andreassen, O. A. (2009). Similar immune profile in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: selective increase in soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I and von Willebrand factor. Bipolar disorders, 11(7), 726–734. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).