Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Discovery of Biocatalysis and Chirality

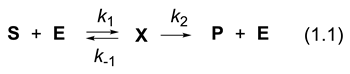

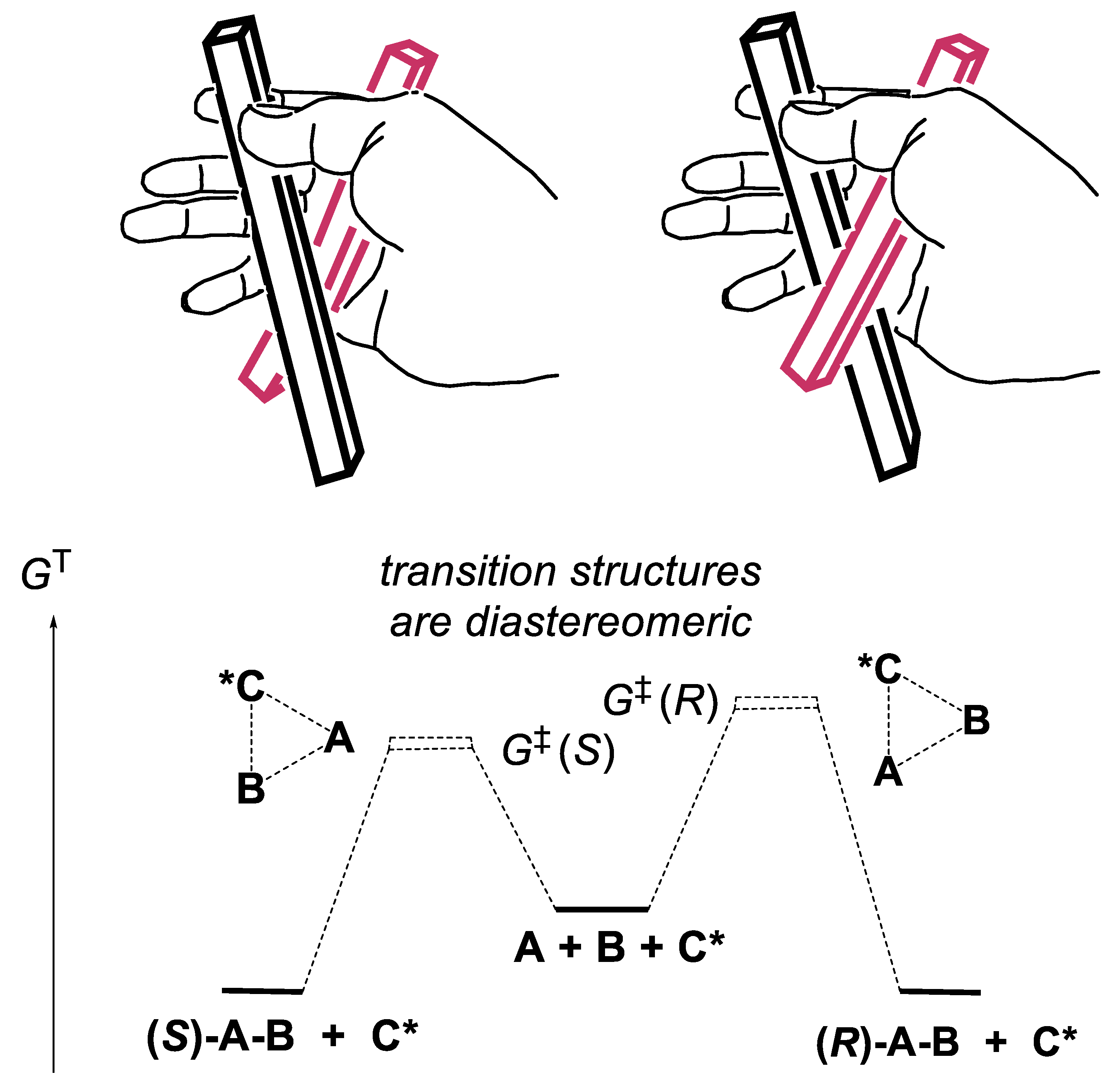

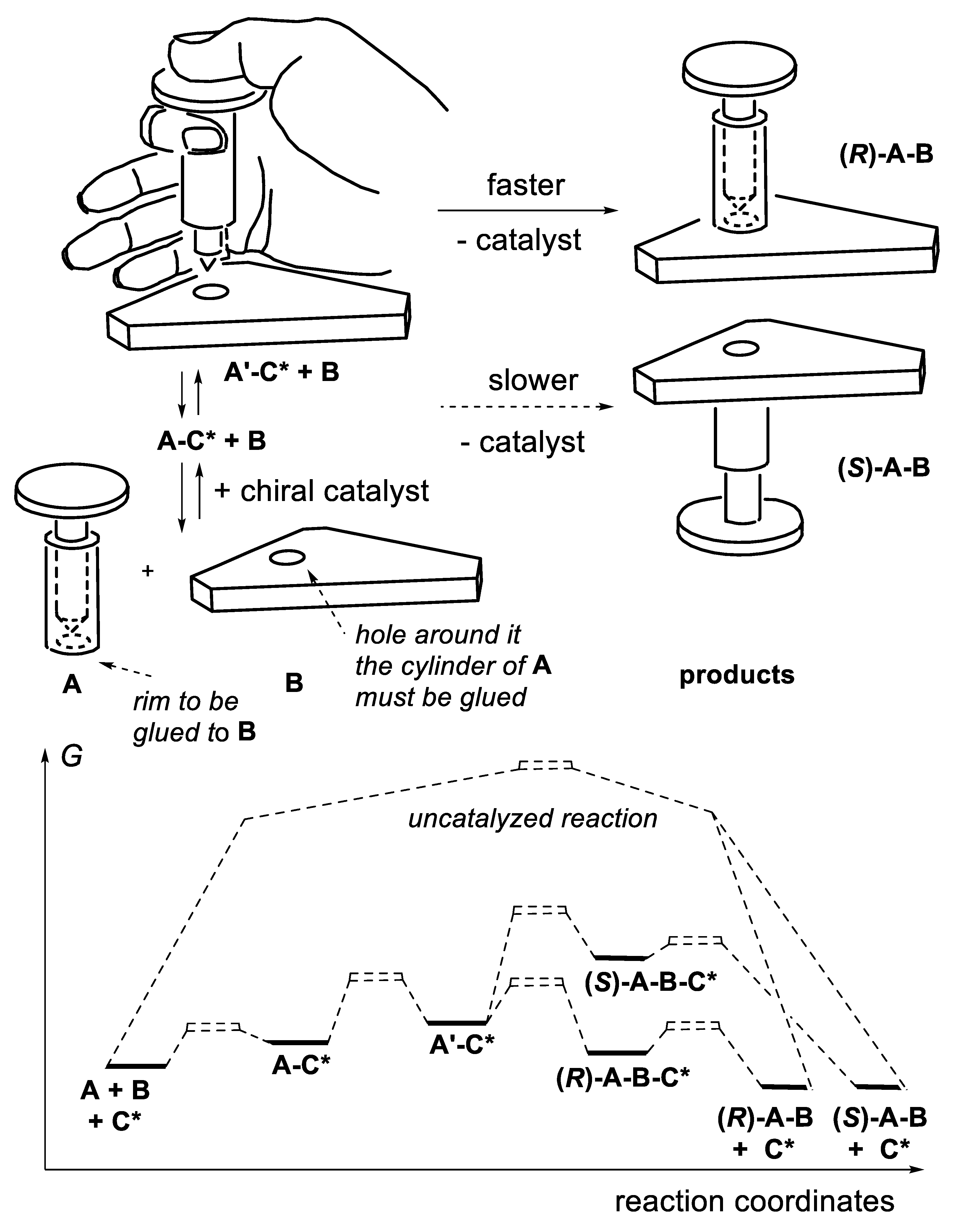

1.2. Kinetic Enantioselectivity

1.3. Chiral Catalysts Are Temporary Chiral Auxiliaries

2. Biocatalysis

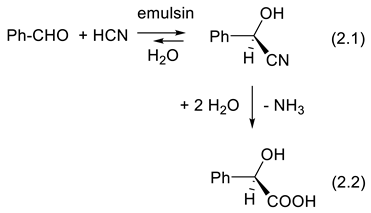

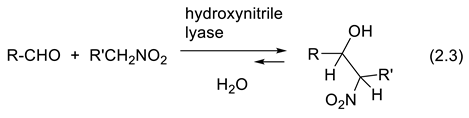

2.1. Hydroxynitrile Lyases

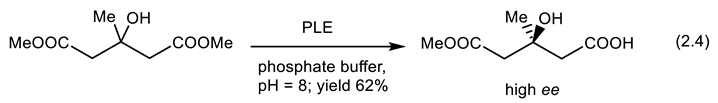

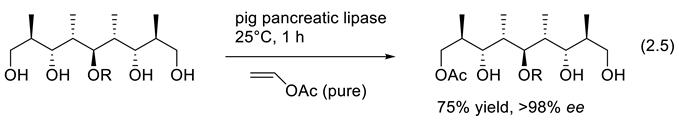

2.2. Esterases

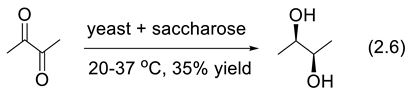

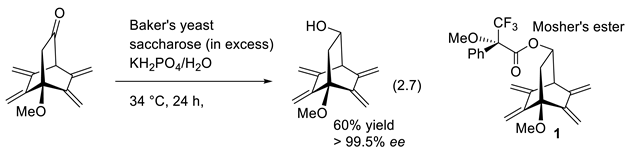

2.3. Baker’s Yeast

2.4. Fermentative Oxidation

2.5. Aldolases

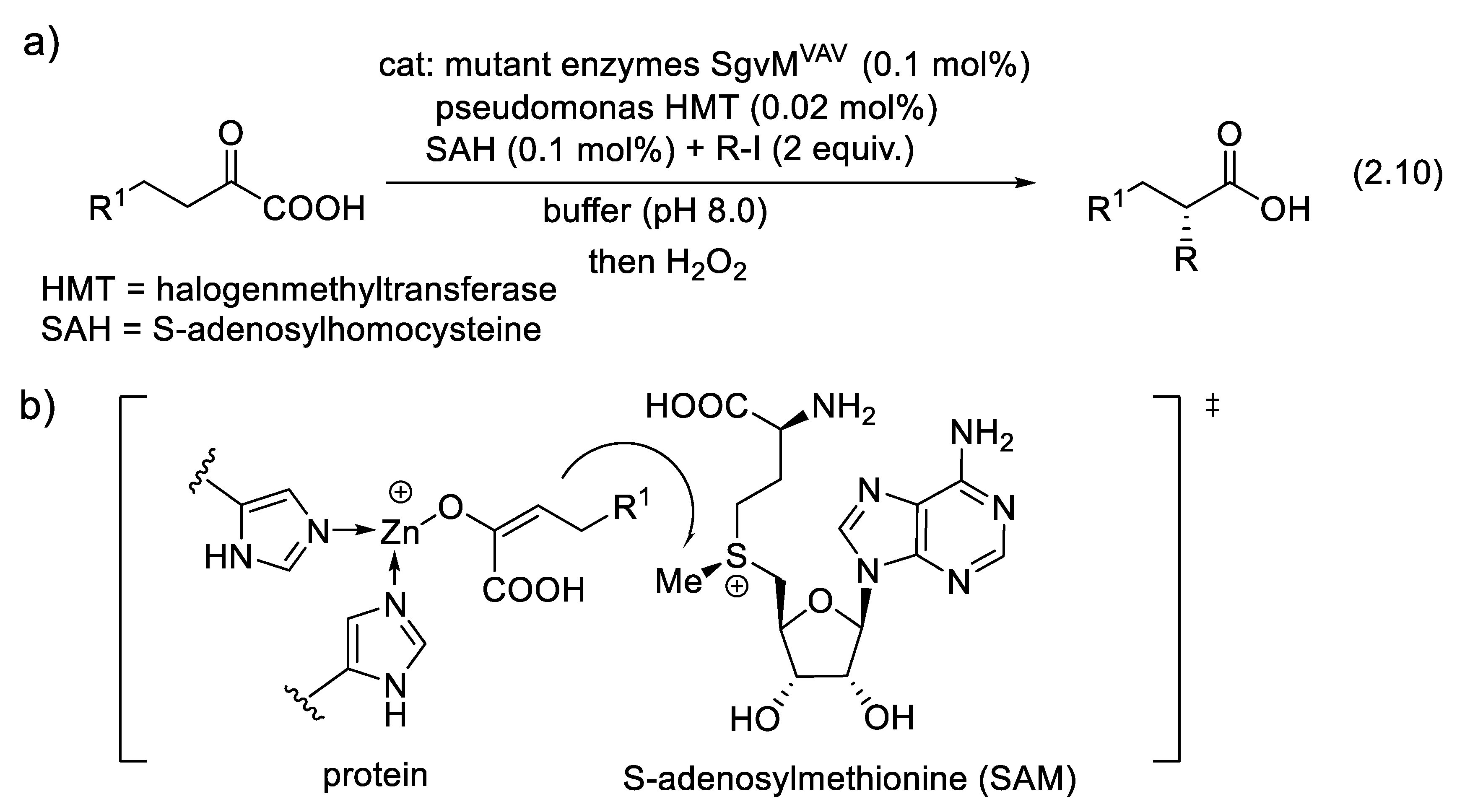

2.6. Other Asymmetric Biocatalyzed C-C Bond-Forming Reactions.

3. Asymmetric Amino-Catalysis: The Queen of Organocatalysis

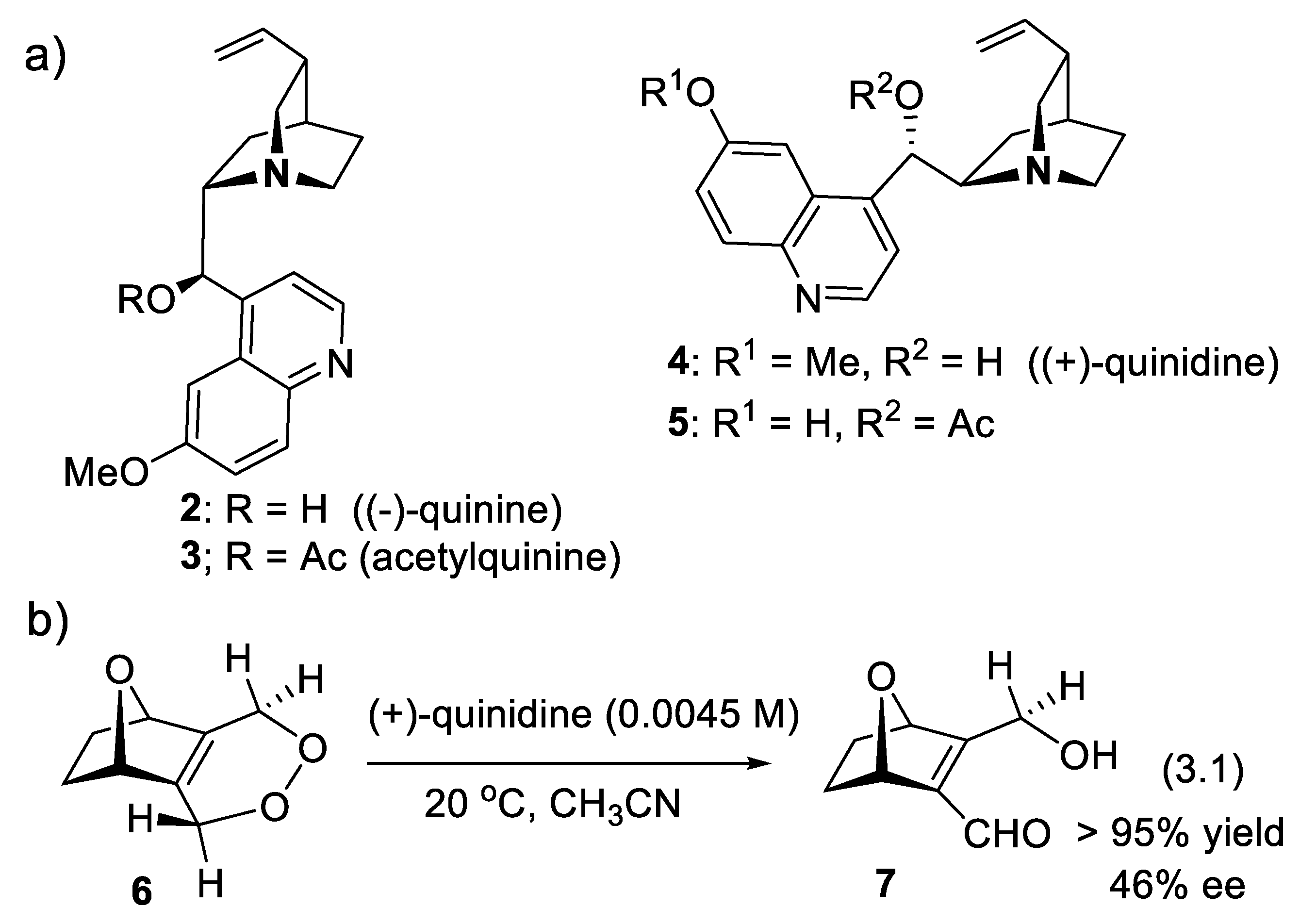

3.1. Cinchona Alkaloids and Derivatives as Catalysts

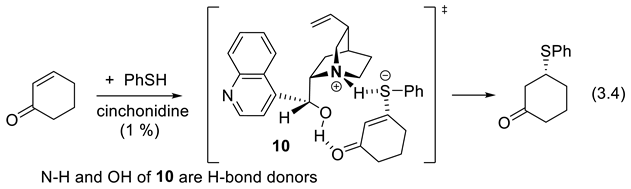

3.1.1. Cinchona Alkaloids as Chiral Brønsted Bases

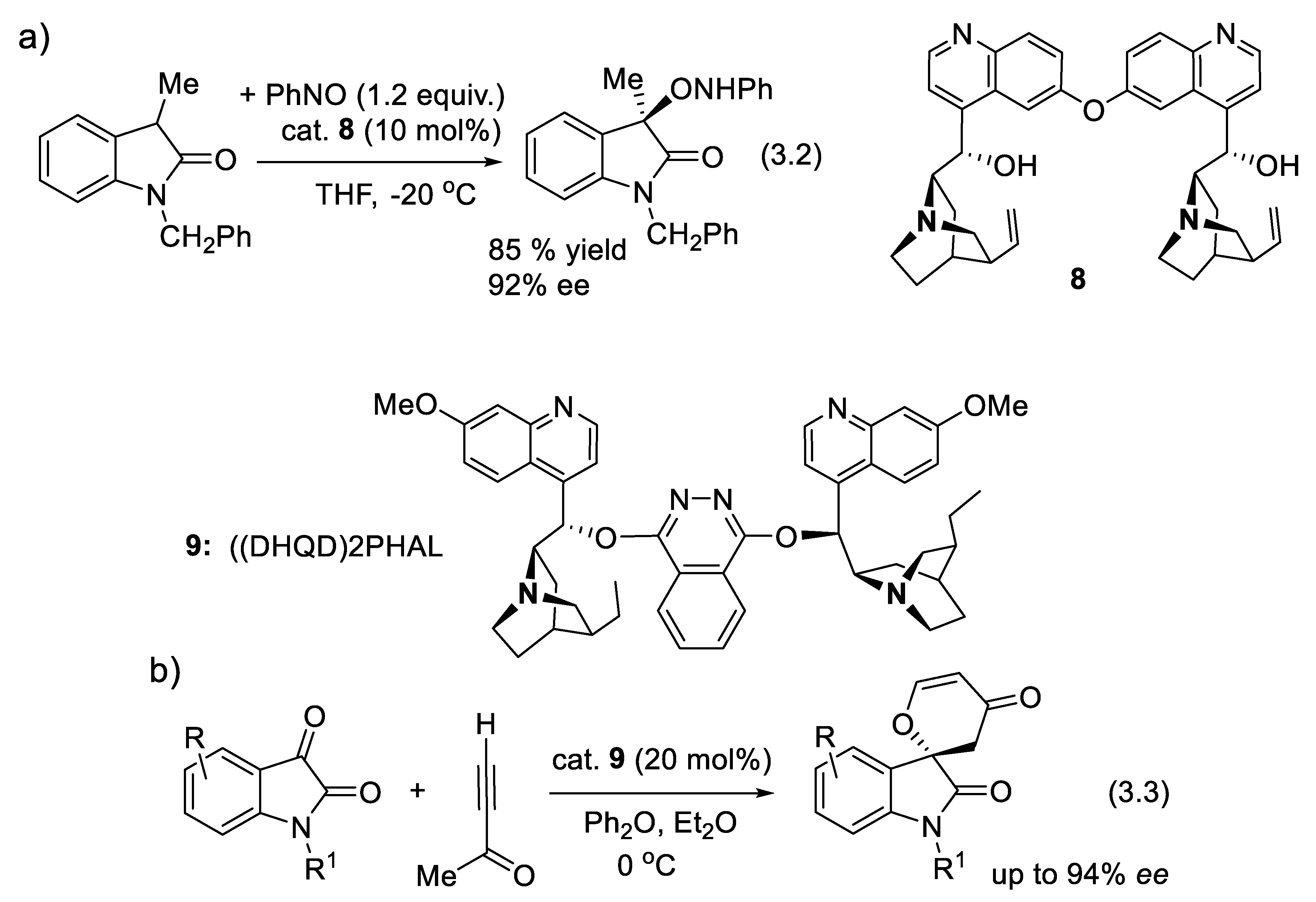

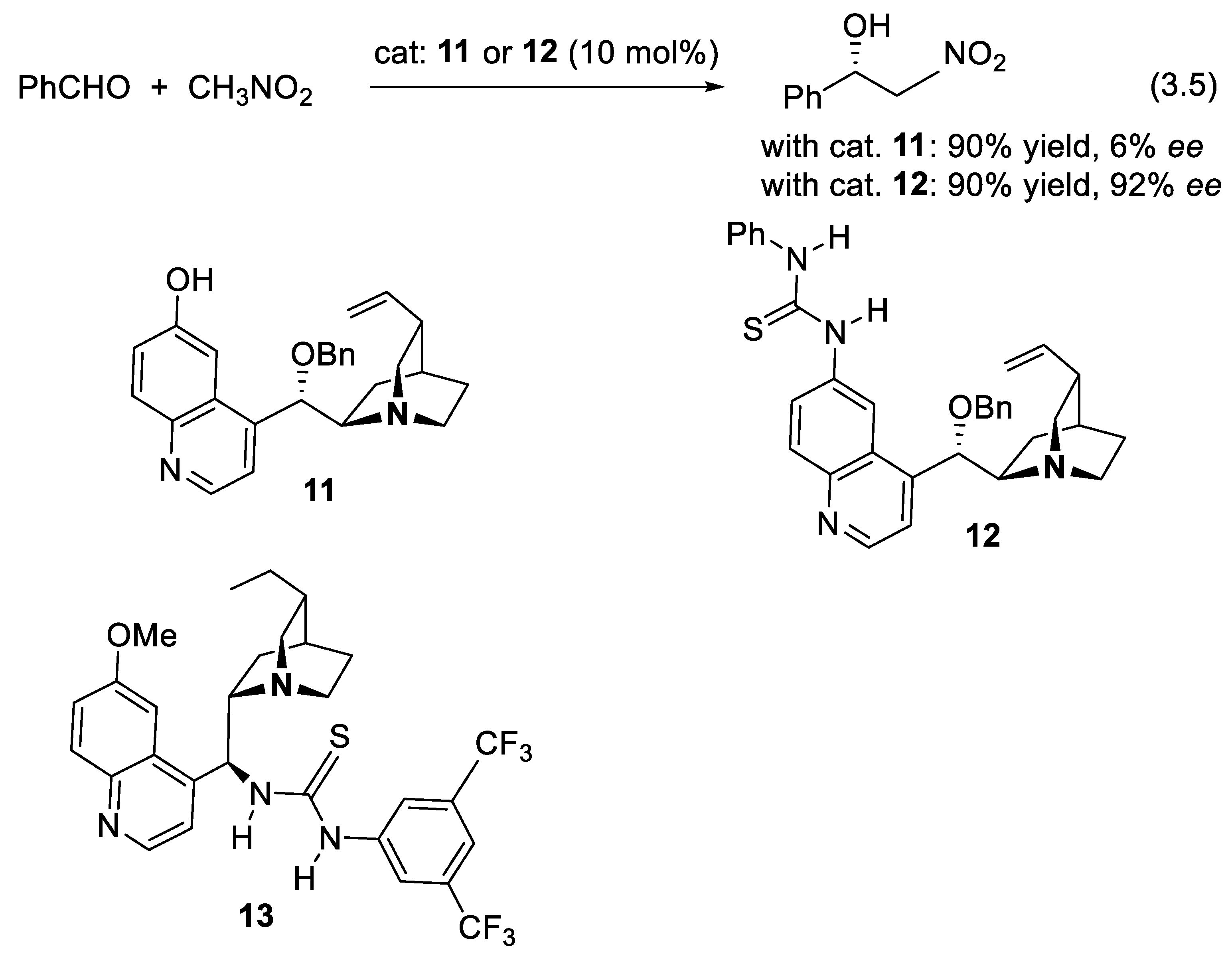

3.1.2. Cinchona Alkaloids and Derivatives Are Capable of Providing Hydrogen Bonding

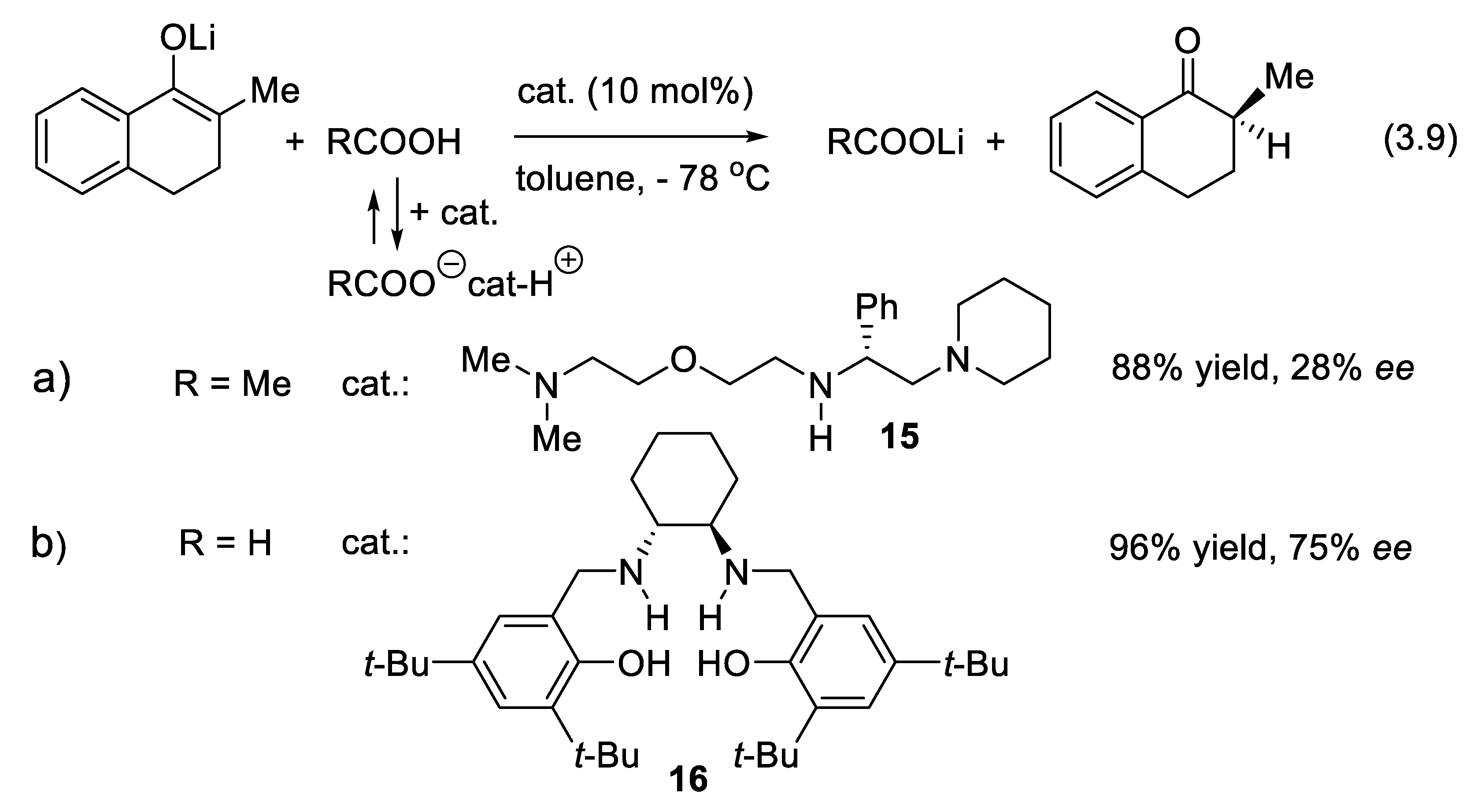

3.1.3. Conjugate Acids of Cinchona Alkaloids and Simpler Chiral Amines as Enantioselective Protonation Catalysts

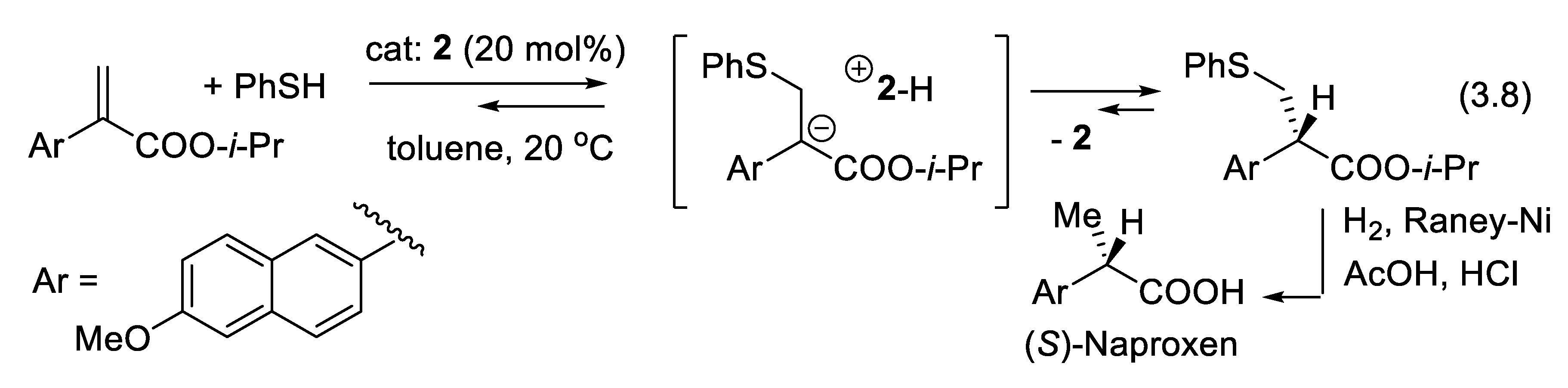

3.1.4. Cinchona Alkaloid Derivatives as Nucleophilic Activators

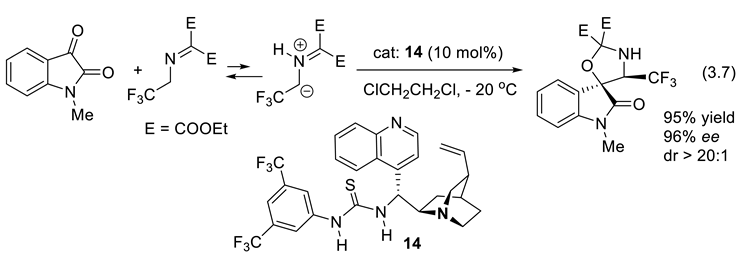

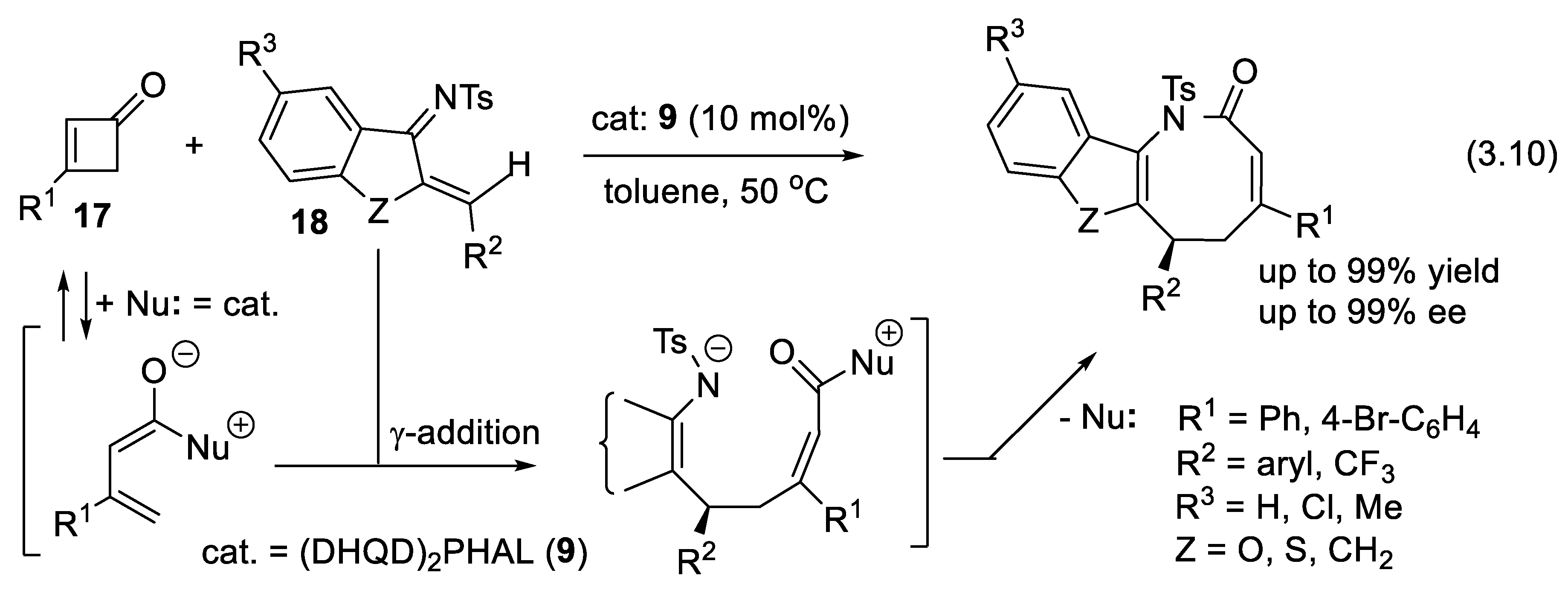

3.1.5. Iminium Ion Mode of Activation by Cinchona Alkaloids

3.1.6. Enamine Mode of Activation by Cinchona Alkaloids

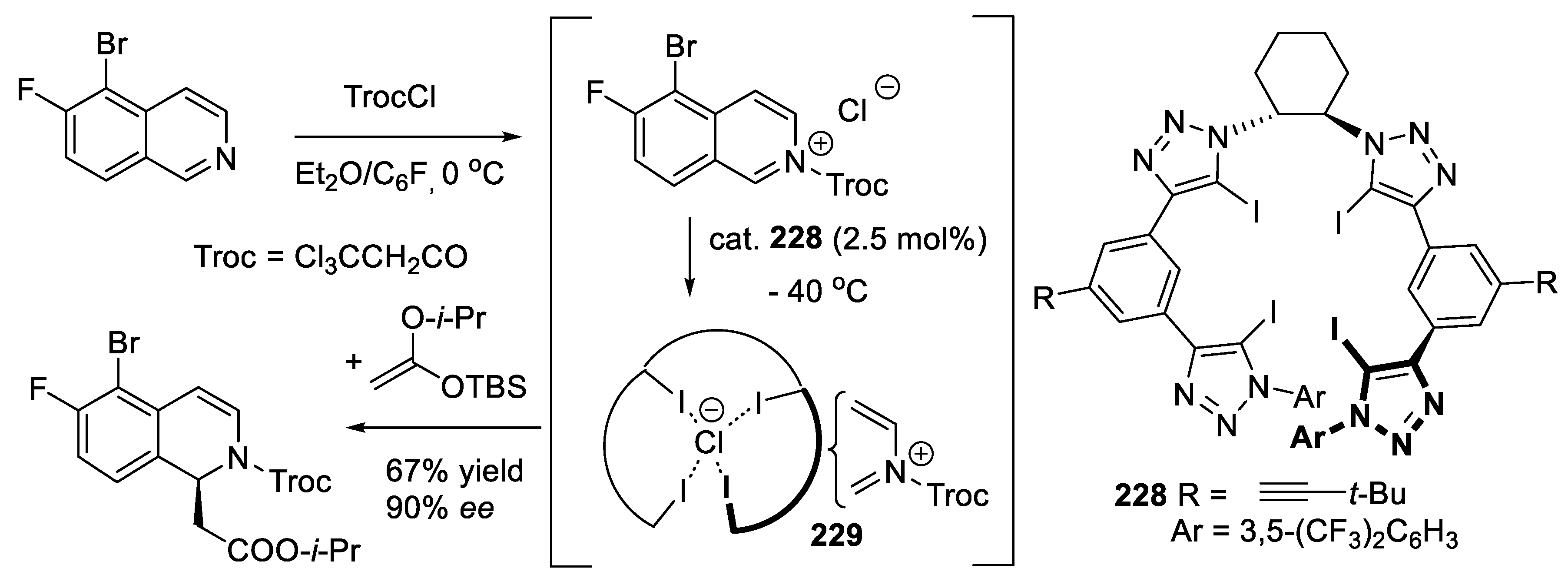

3.1.7. Cinchona Alkaloid Derivatives with Halogen Bond (XB) Donors

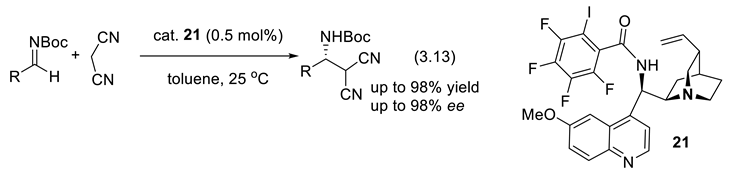

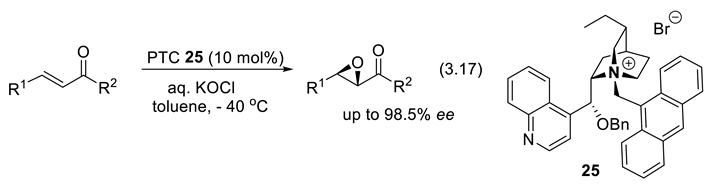

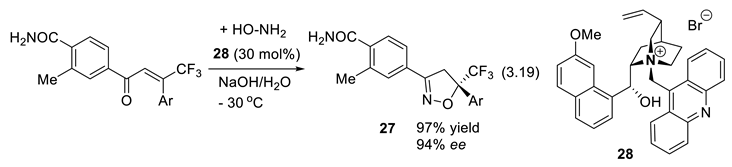

3.2. Cinchona Alkaloid-Derived Ammonium Salts: Enantioselective Phase Transfer Catalysts (PTCs)

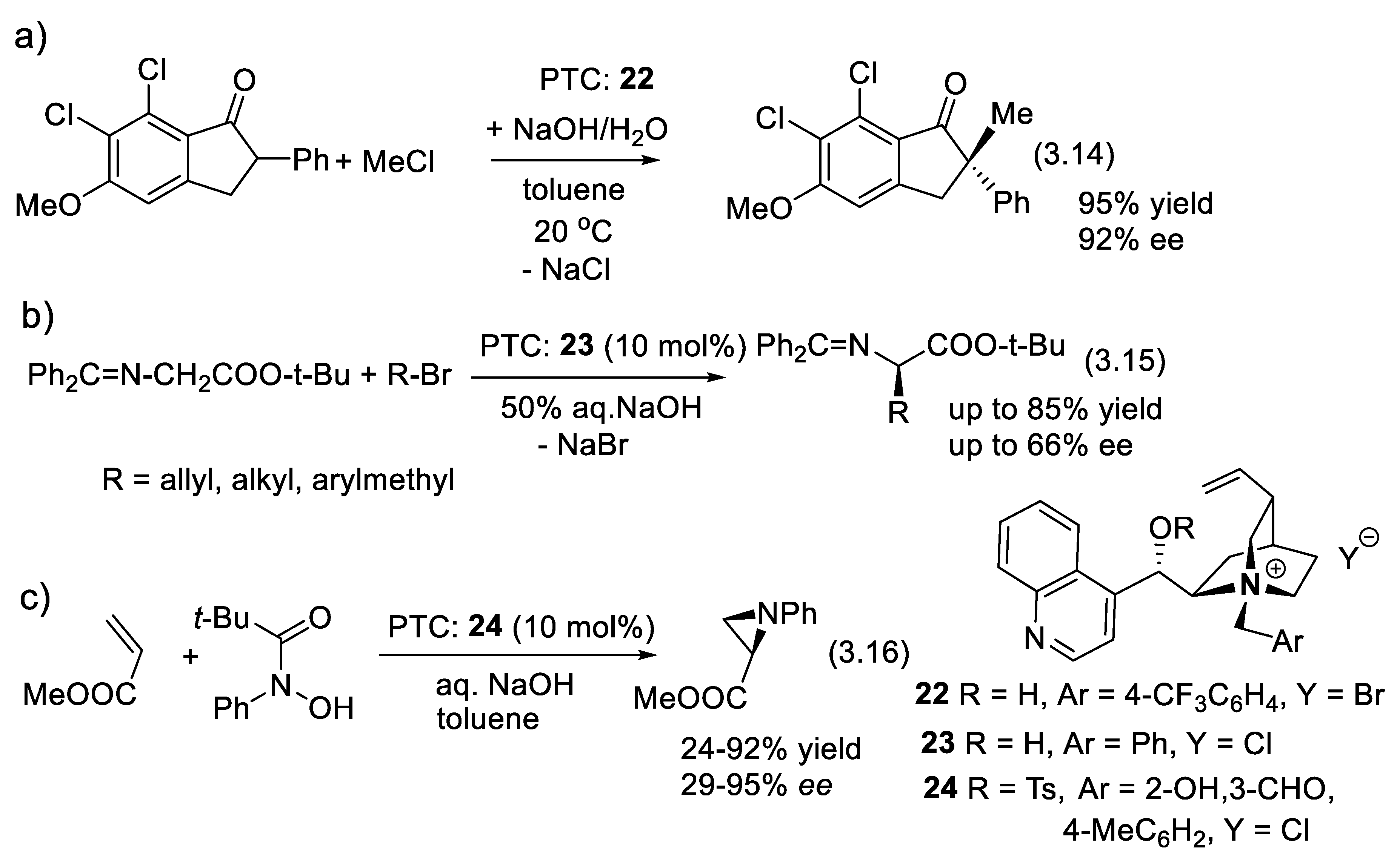

3.2.1. Early Enantioselective Phase Transfer Catalyzed Applications

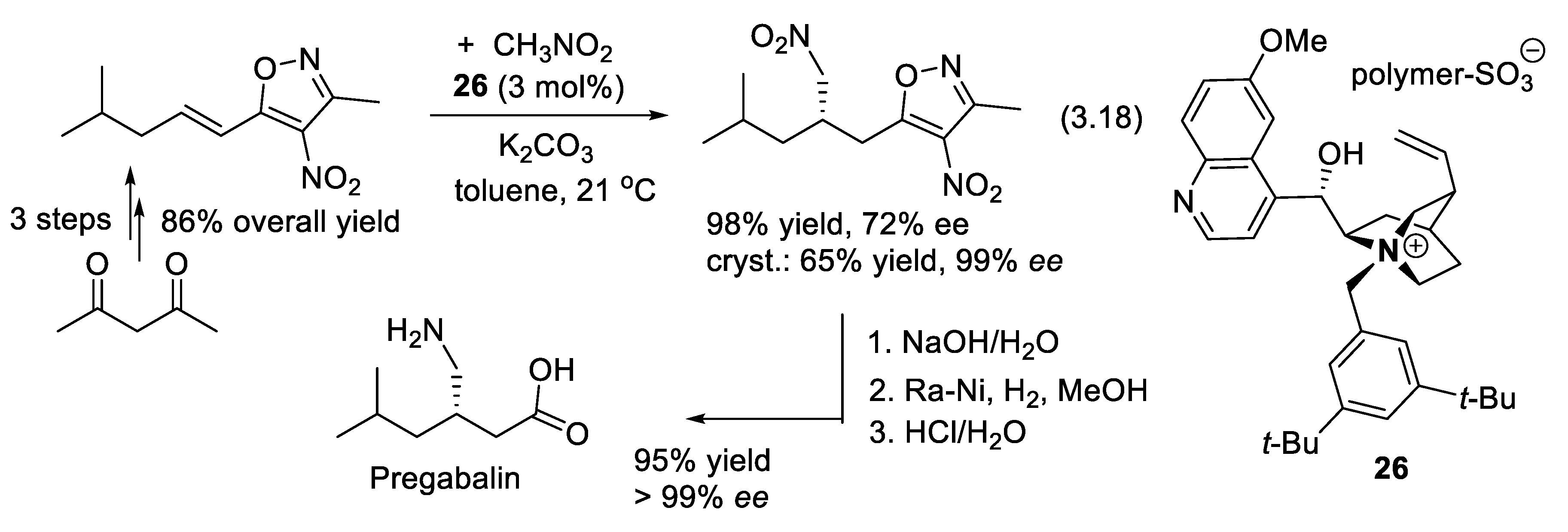

3.2.2. Industrial Applications of Chiral PTCs

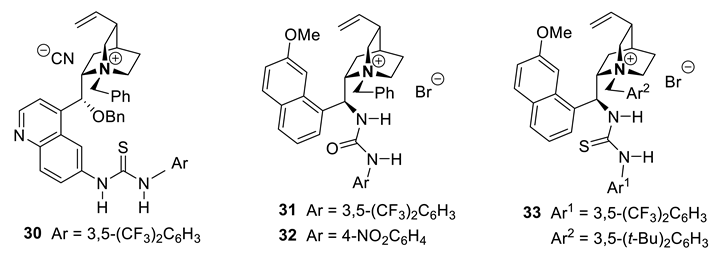

3.2.3. Polyfunctional Cinchona-Derived Polyfunctional PTCs

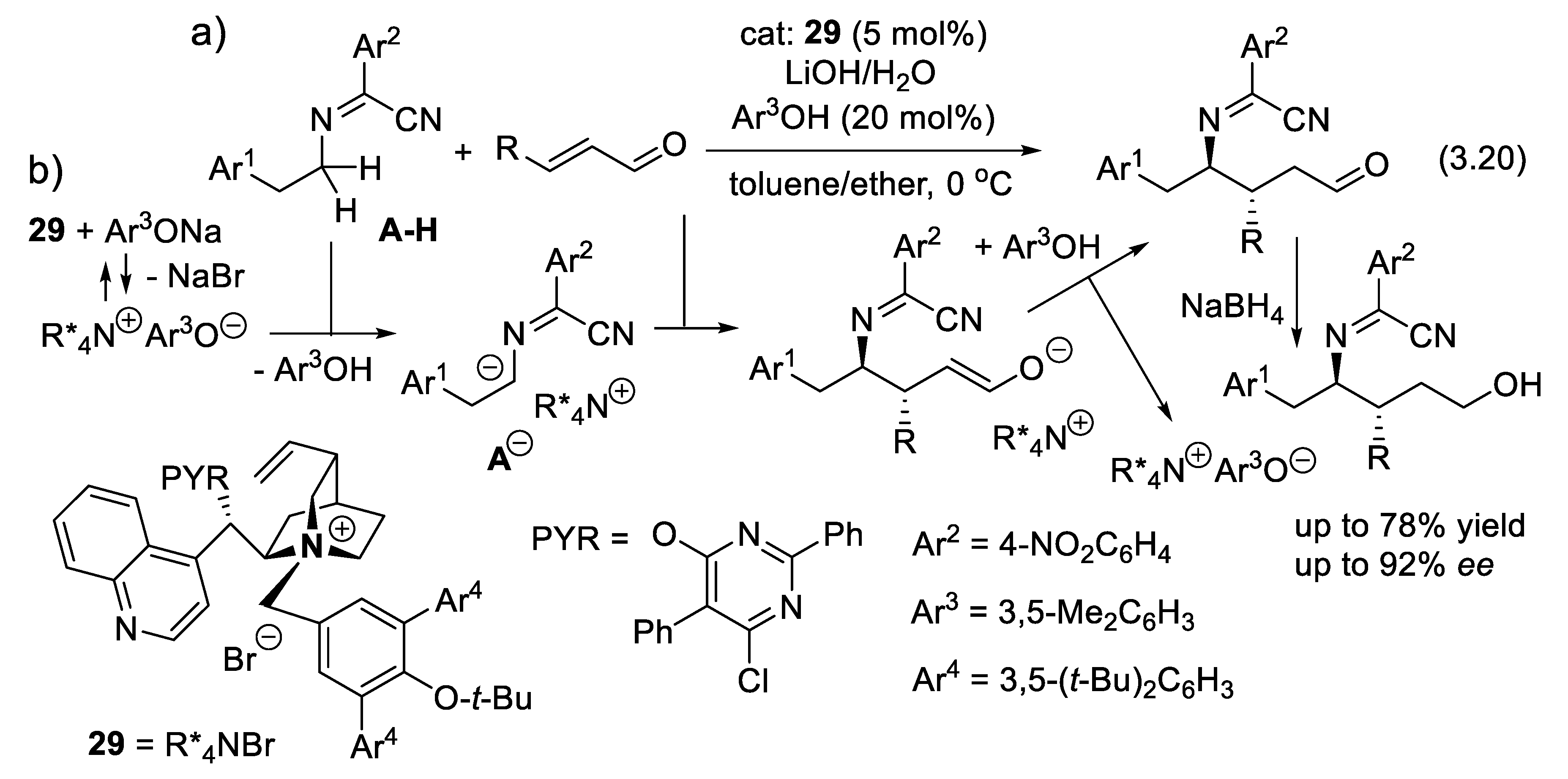

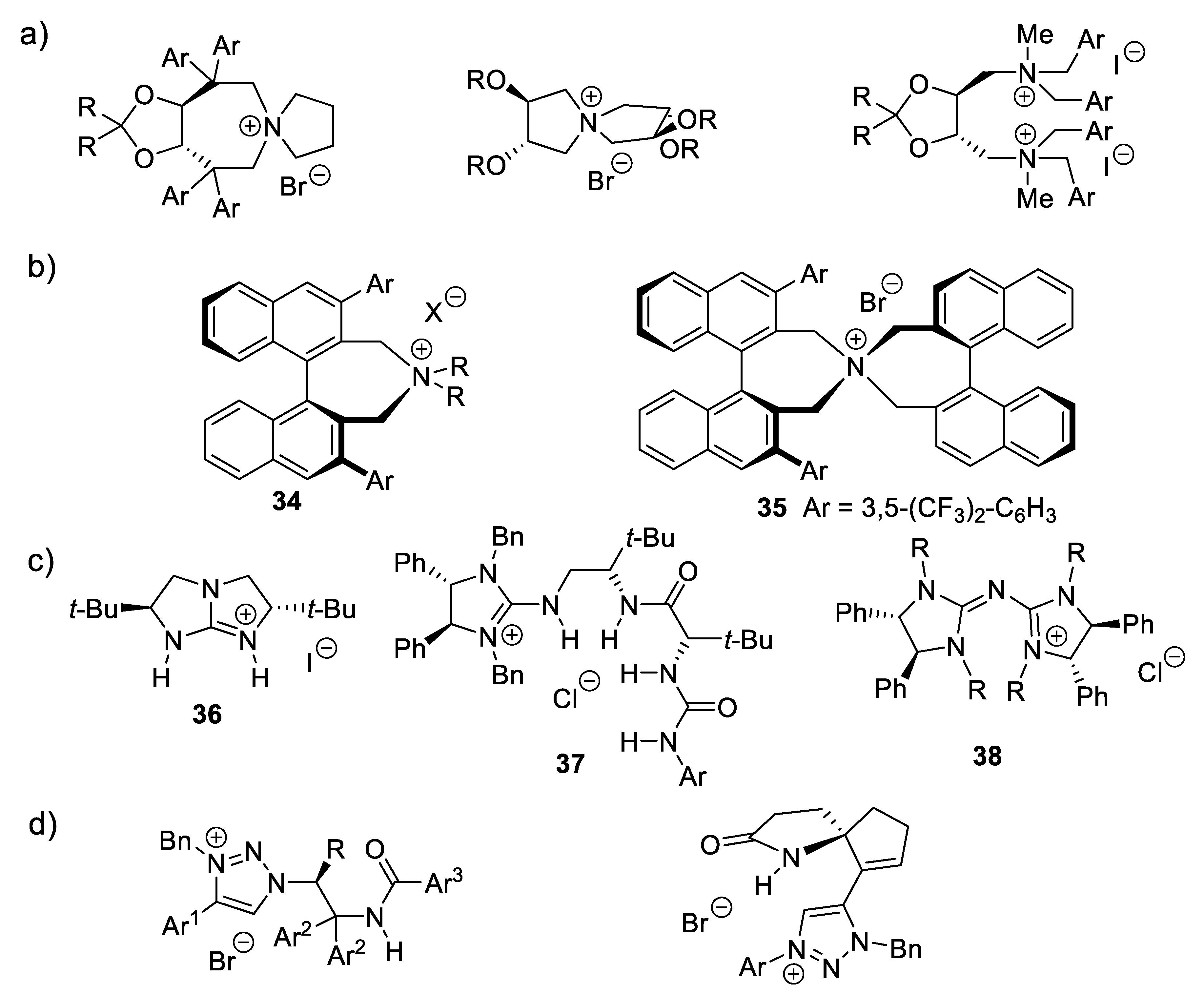

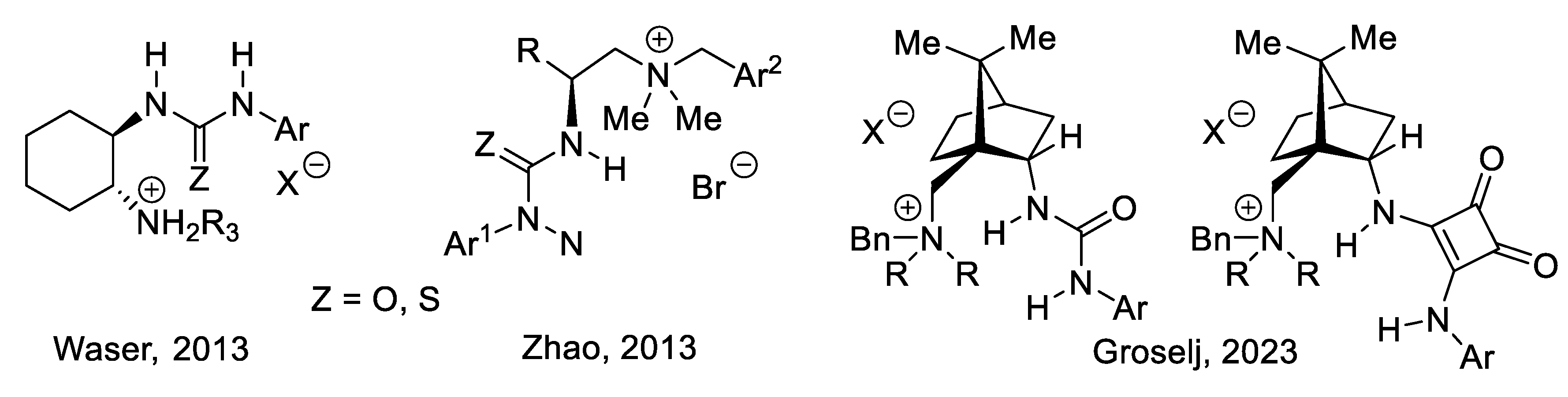

3.2.4. Non-Cinchona-Derived Chiral Ammonium Phase Transfer Catalysts

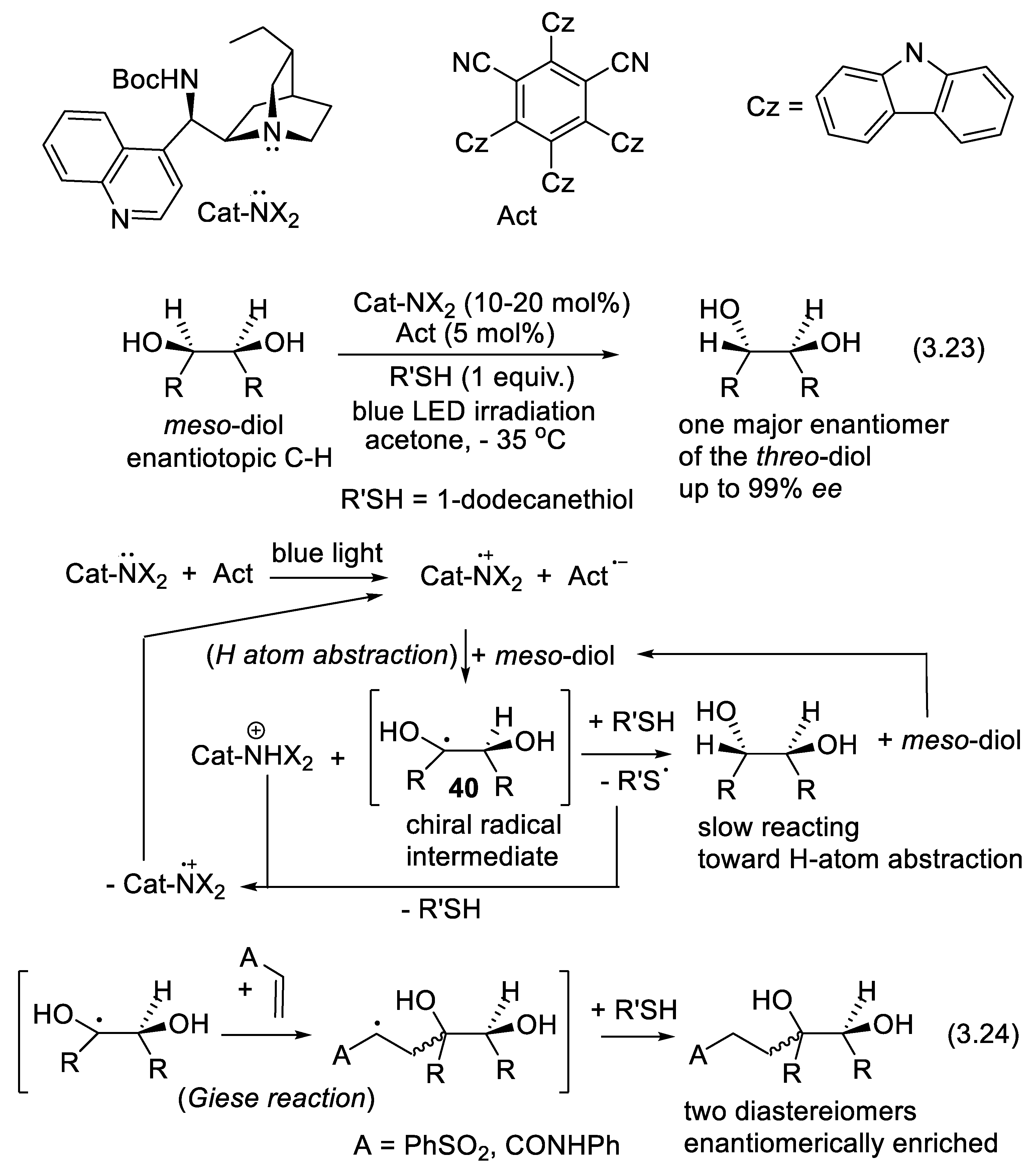

3.3. Asymmetric Hydrogen Atom Abstraction with Cinchona Alkaloid Derivatives

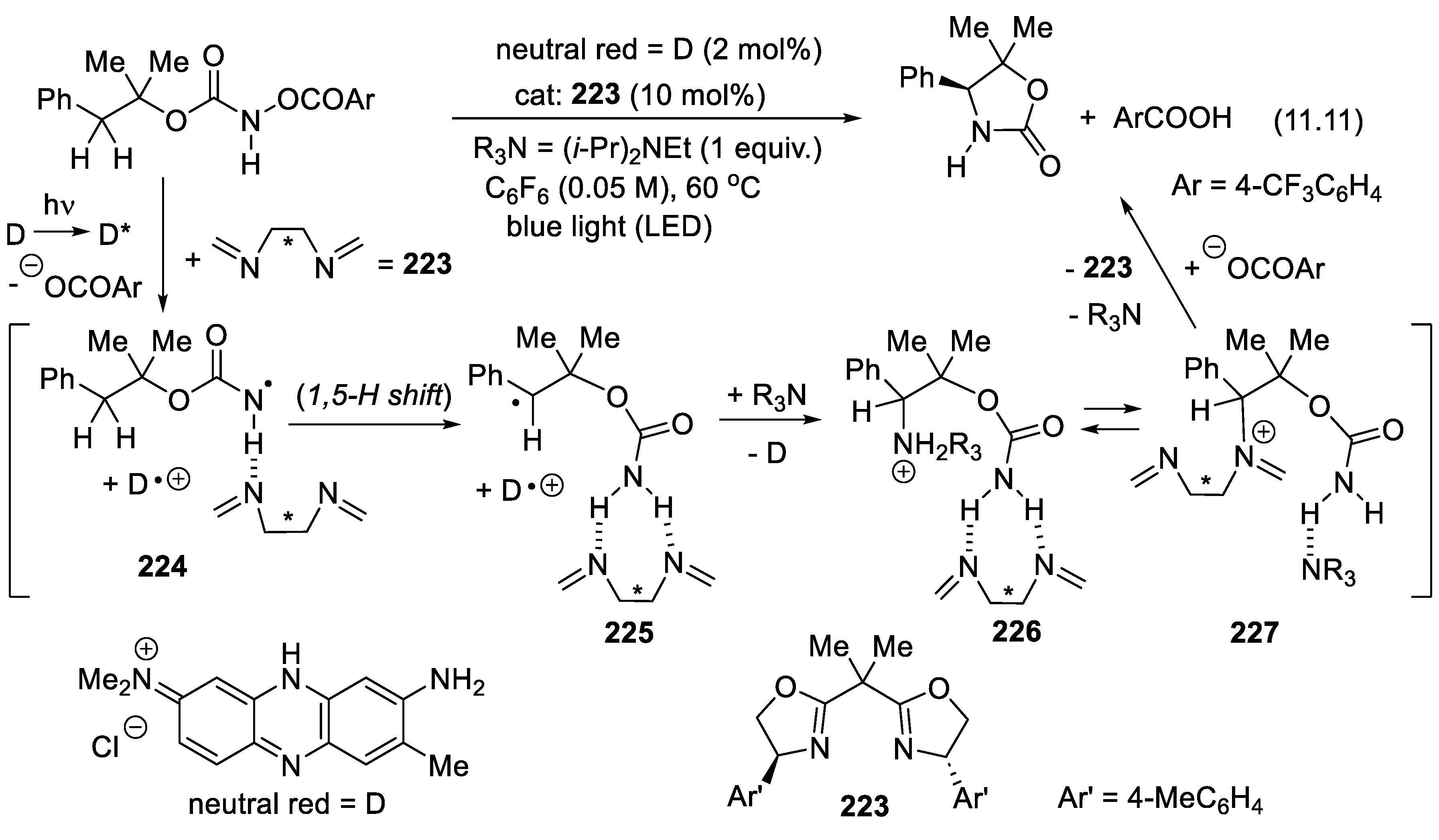

3.4. Iminium Ion Mode of Activation by Simple Chiral Amines

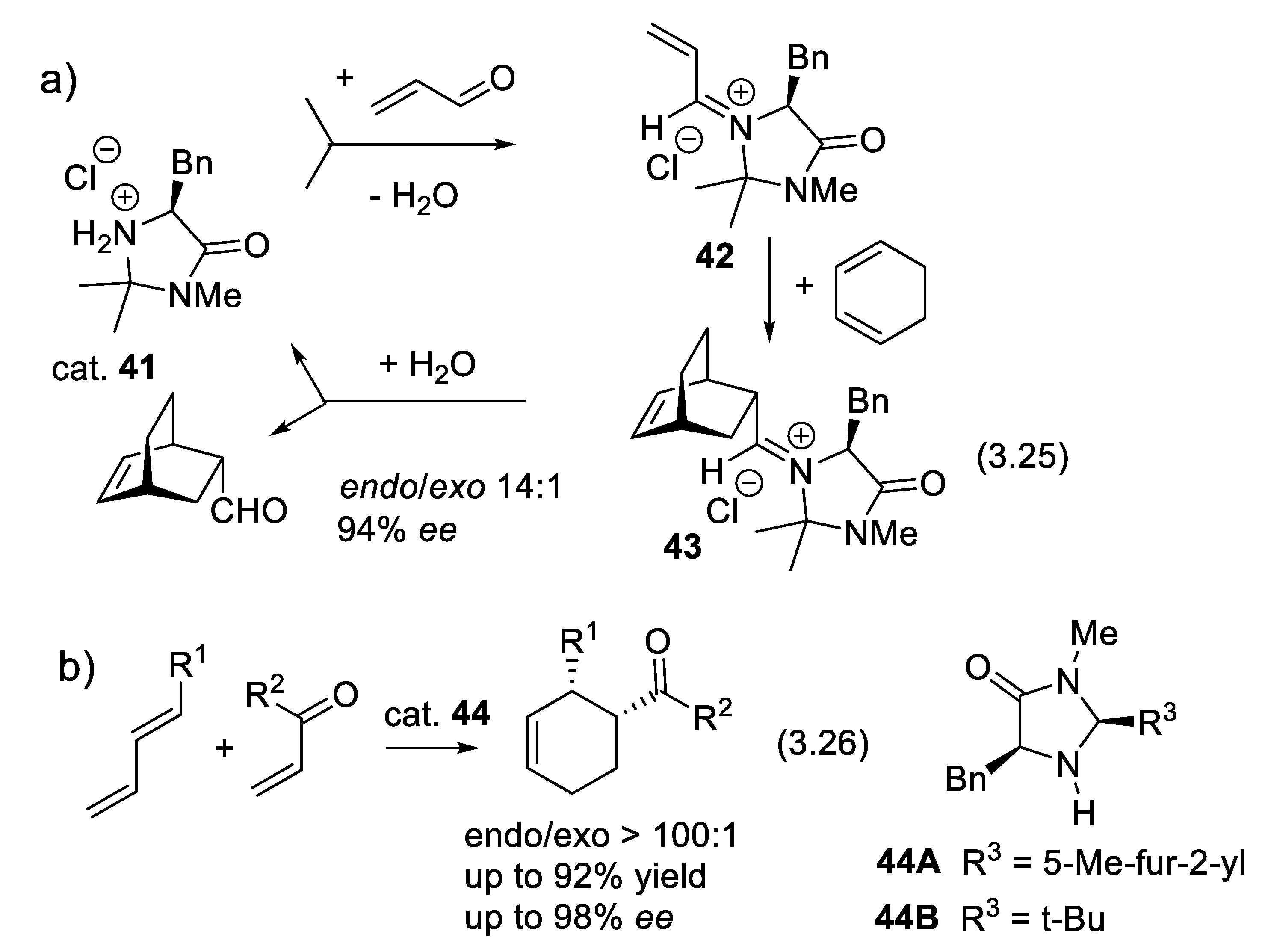

3.5. Enamine Mode of Activation by Simple Chiral Amines

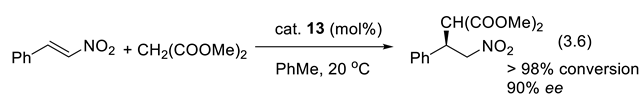

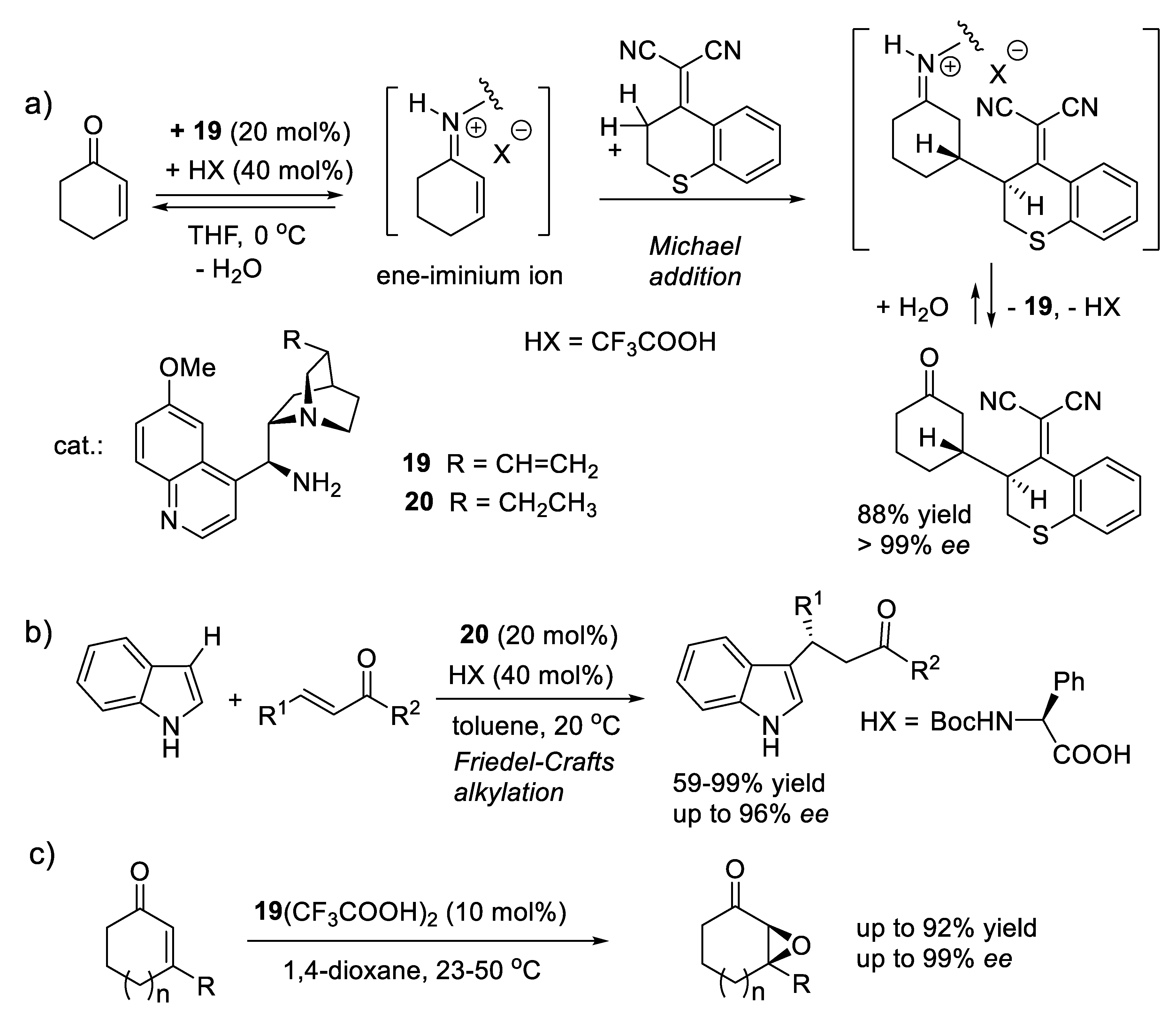

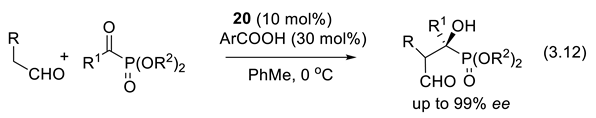

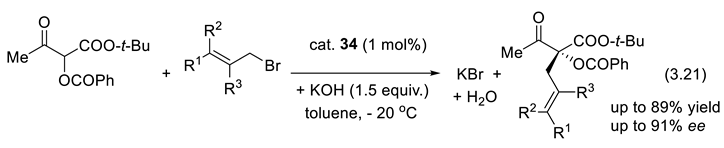

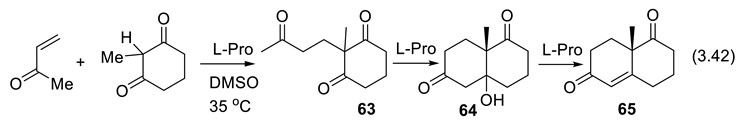

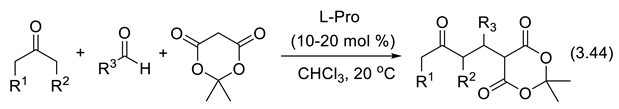

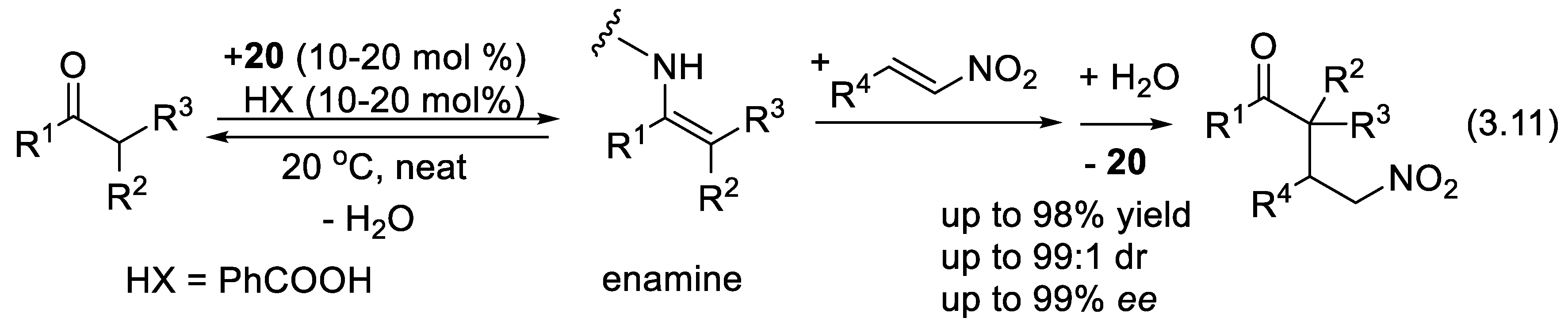

3.5.1. Asymmetric Michael Additions

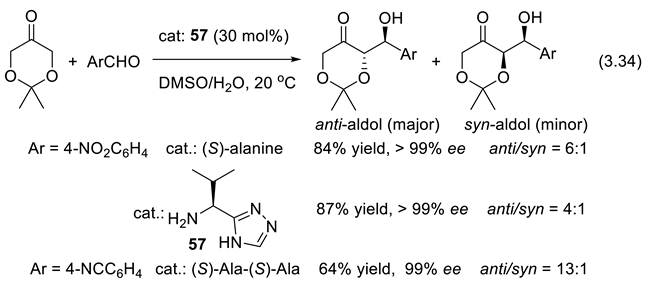

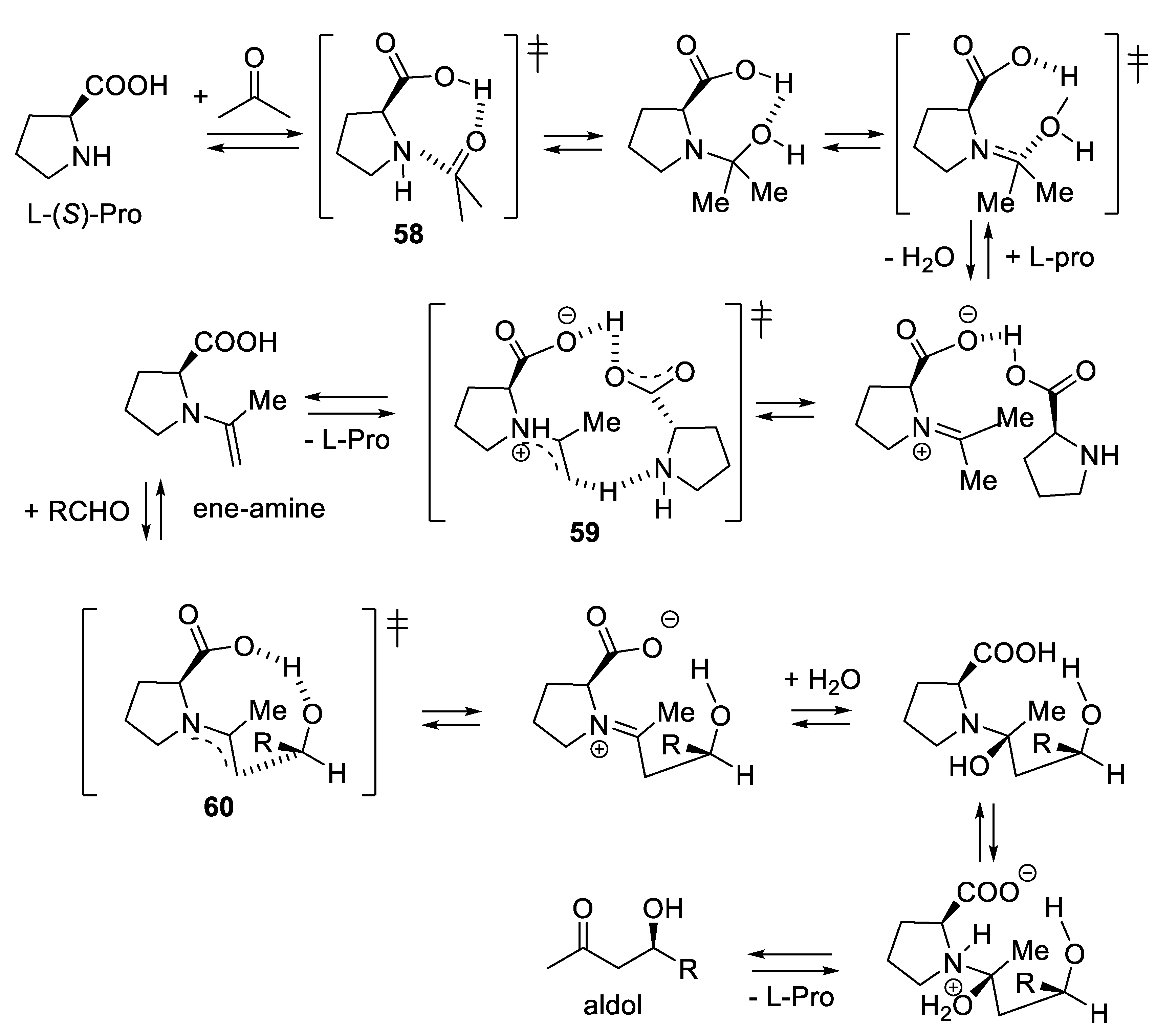

3.5.2. Asymmetric Aldol Reactions

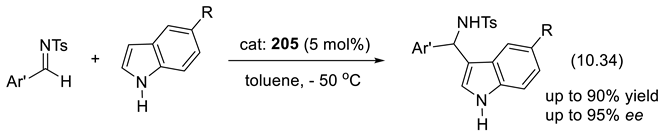

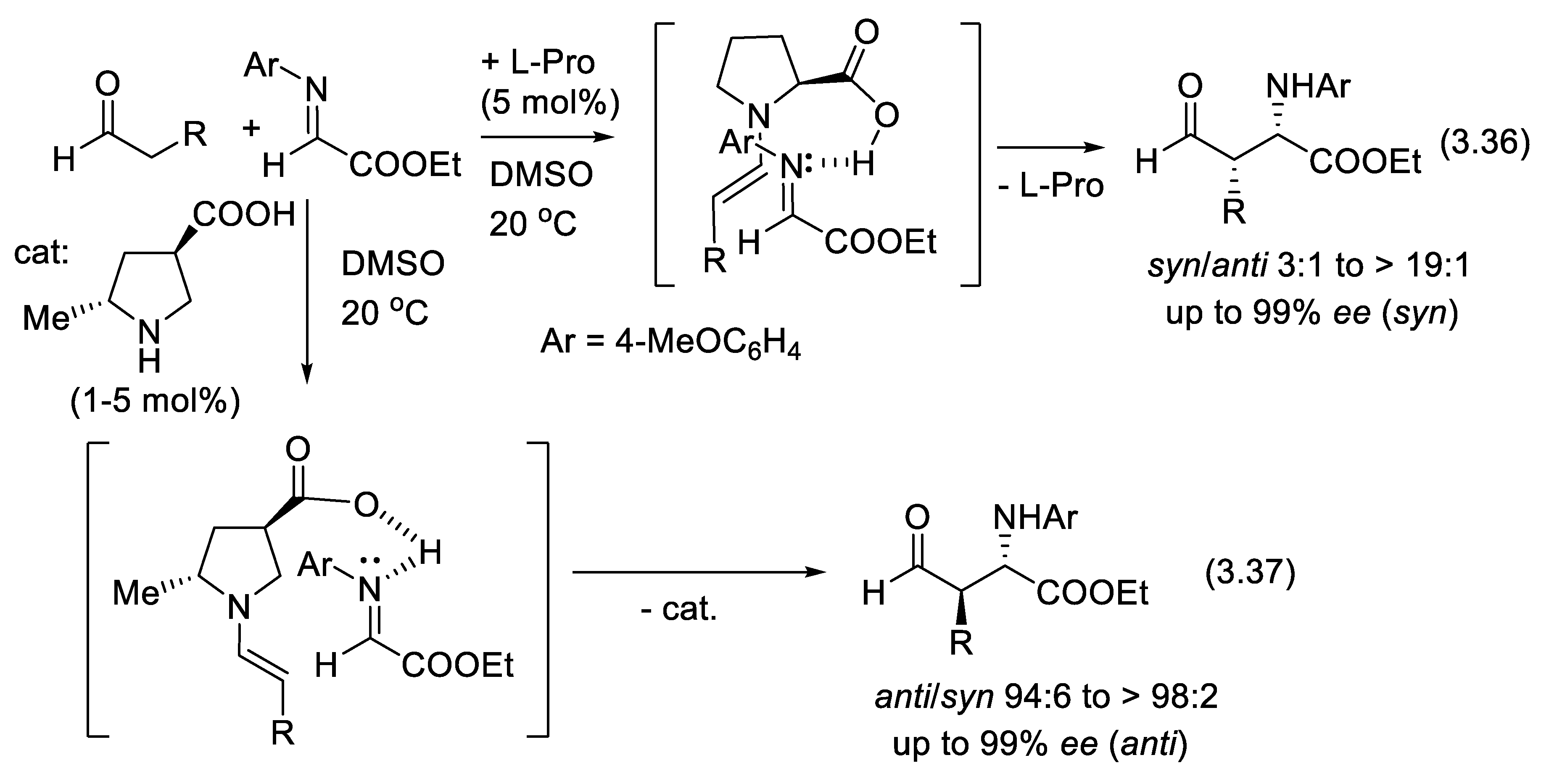

3.5.3. Asymmetric Mannich Condensations

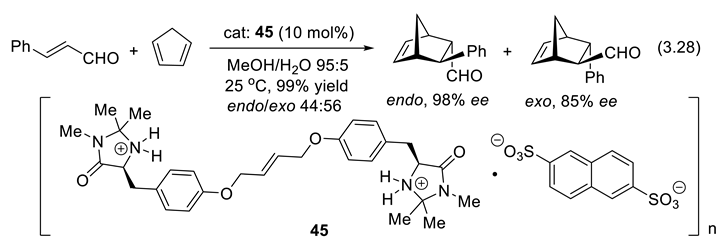

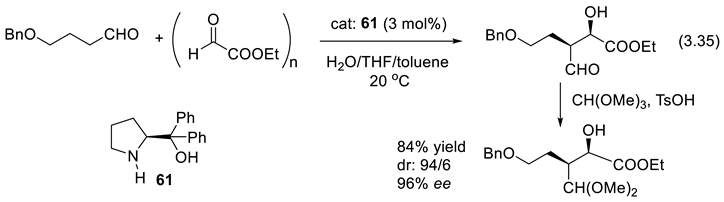

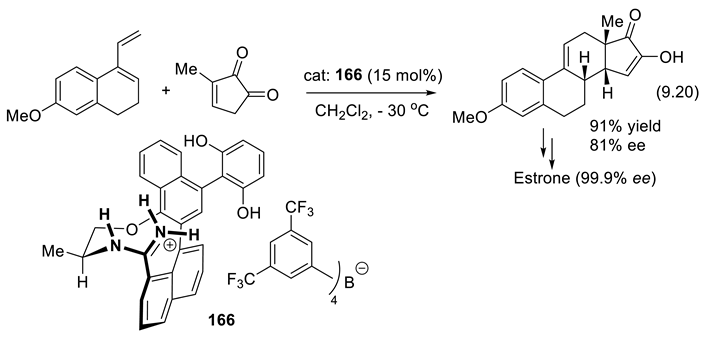

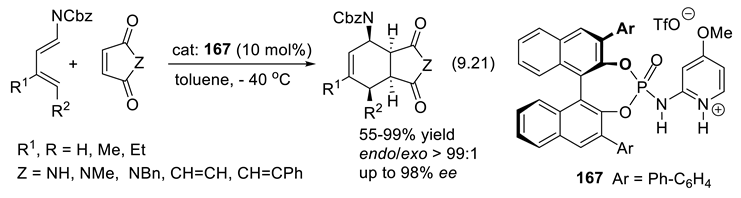

3.5.4. Asymmetric Diels-Alder Reactions with Inverse-Electron-Demand

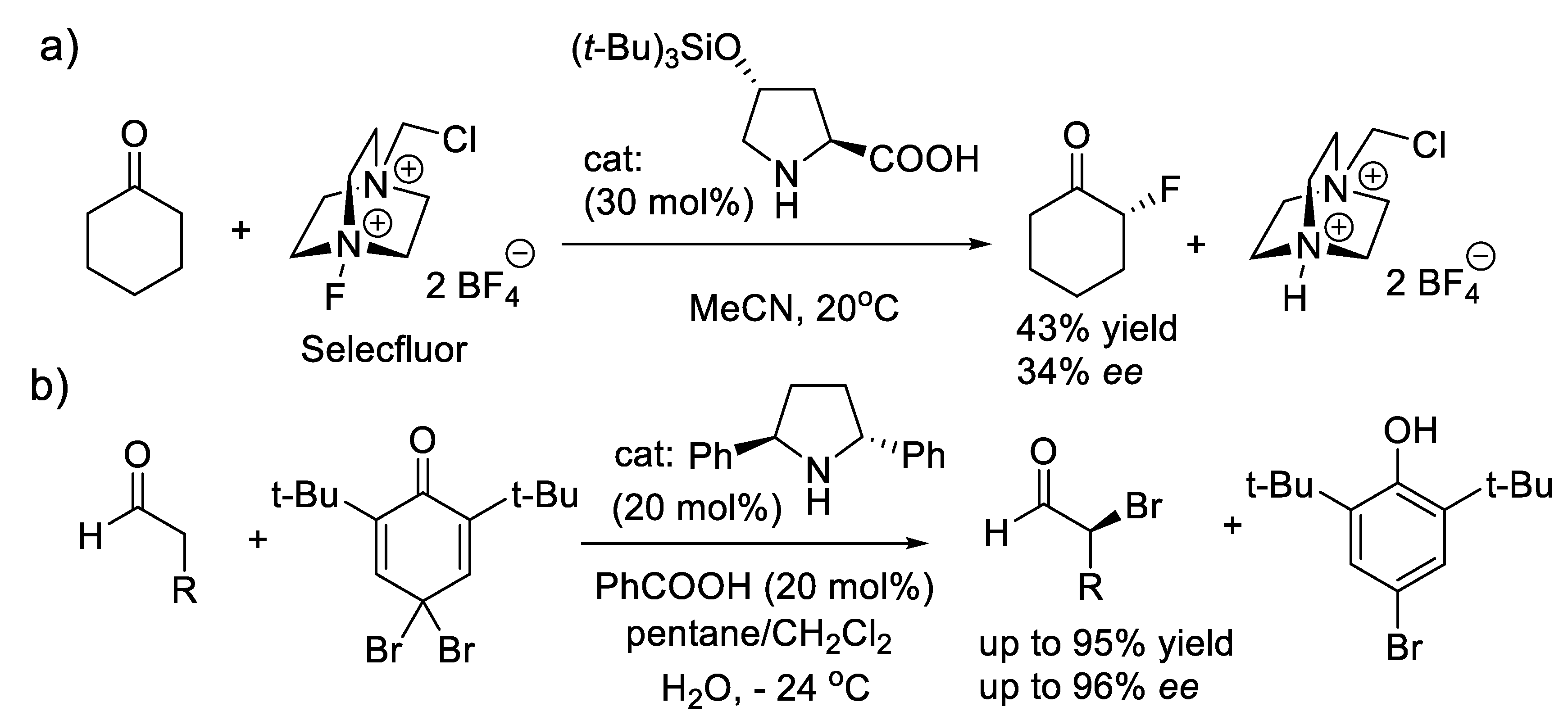

3.5.5. Asymmetric α Halogenations

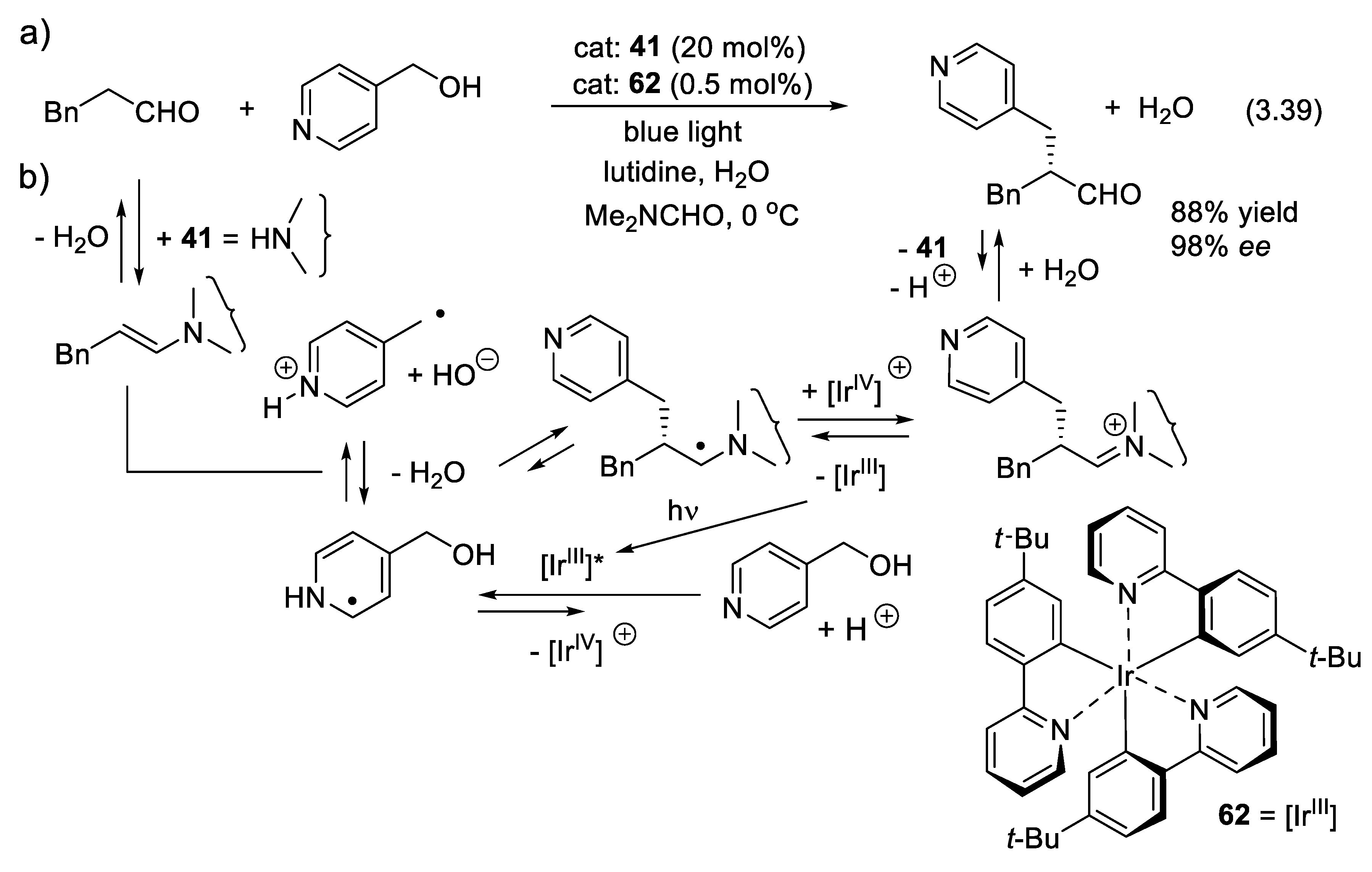

3.5.6. Asymmetric α-Benzylation of Aldehydes with Alcohols

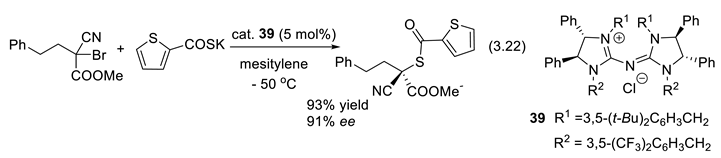

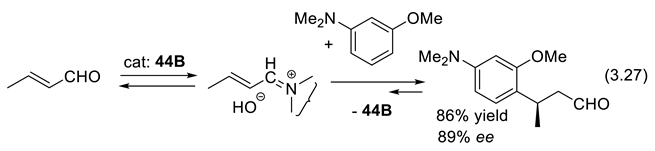

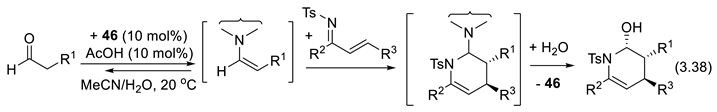

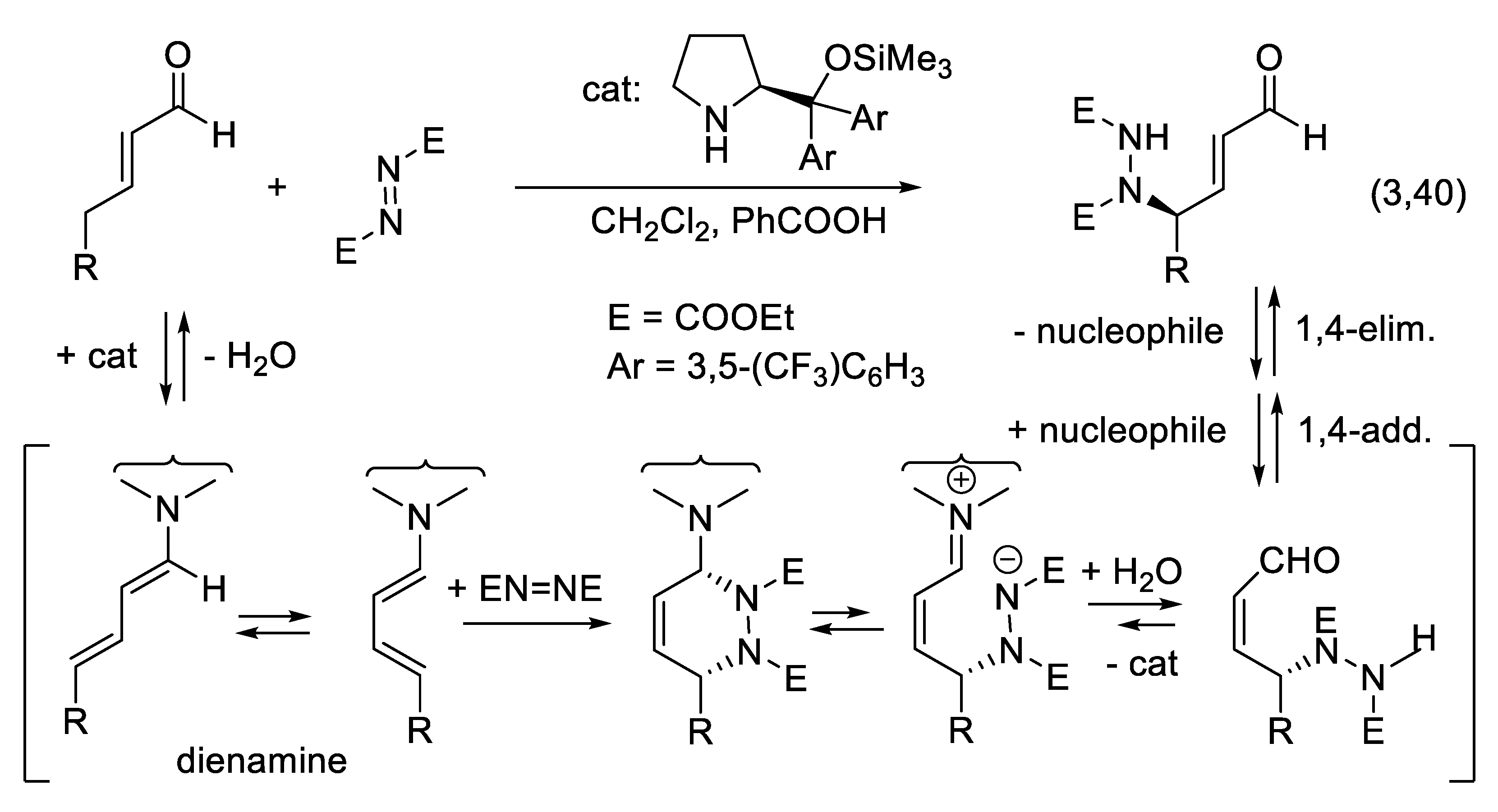

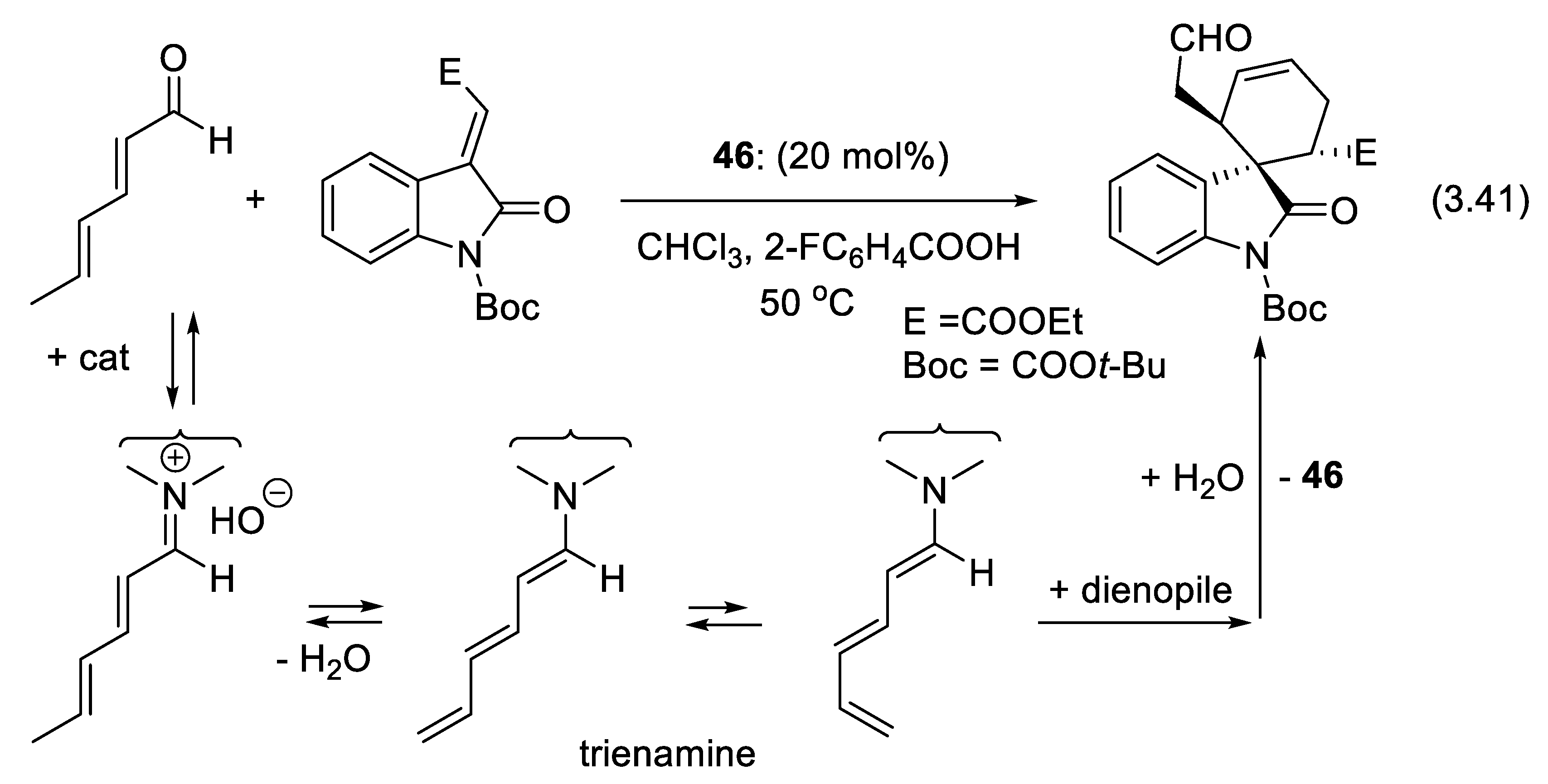

3.6. Dienamine and Trienamine Mode of Activation

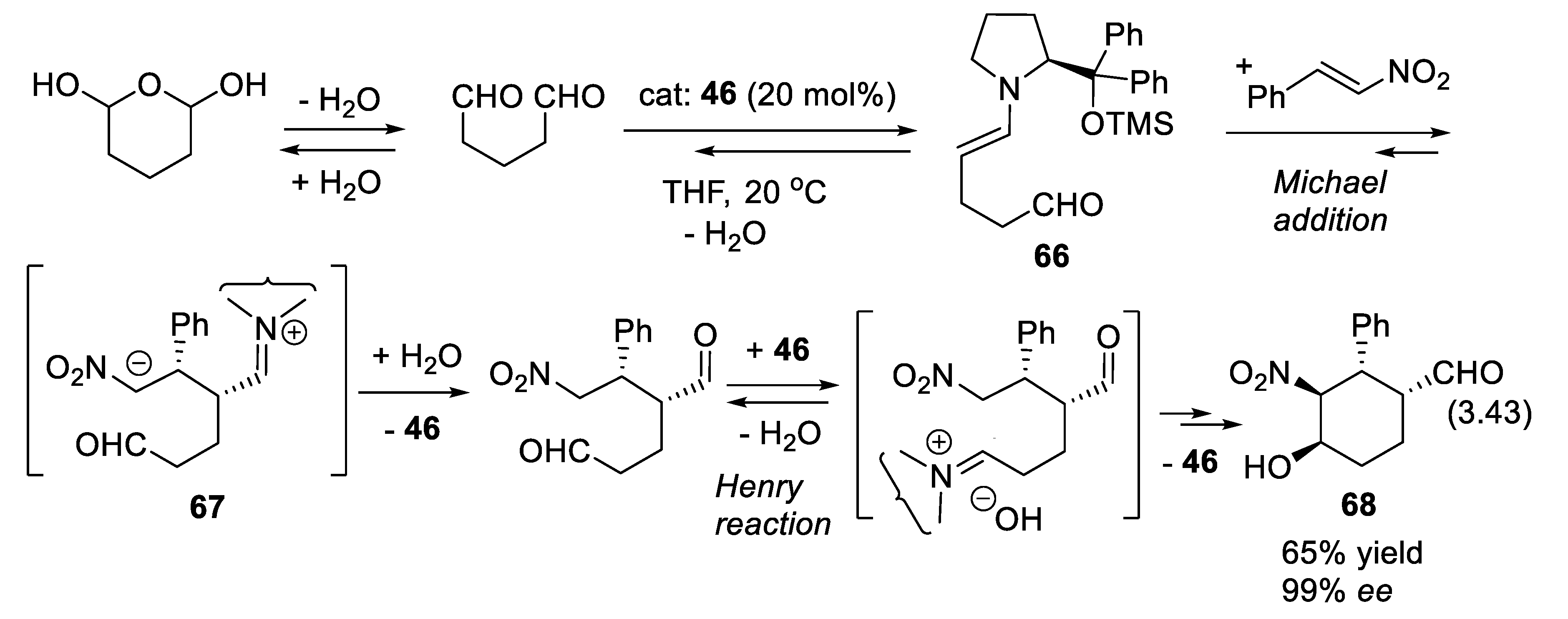

3.7. Asymmetric Amine-Catalyzed Domino Reactions

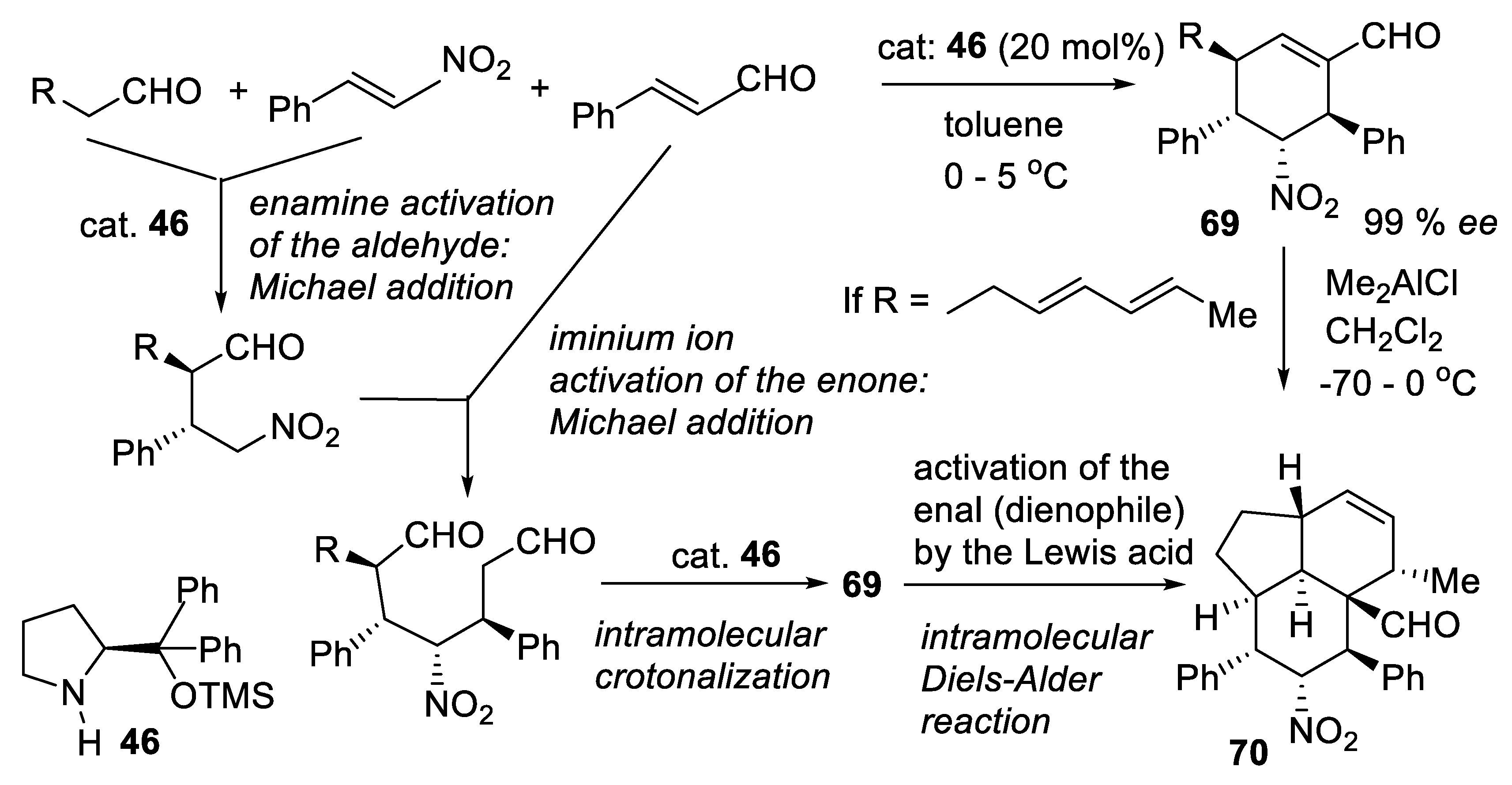

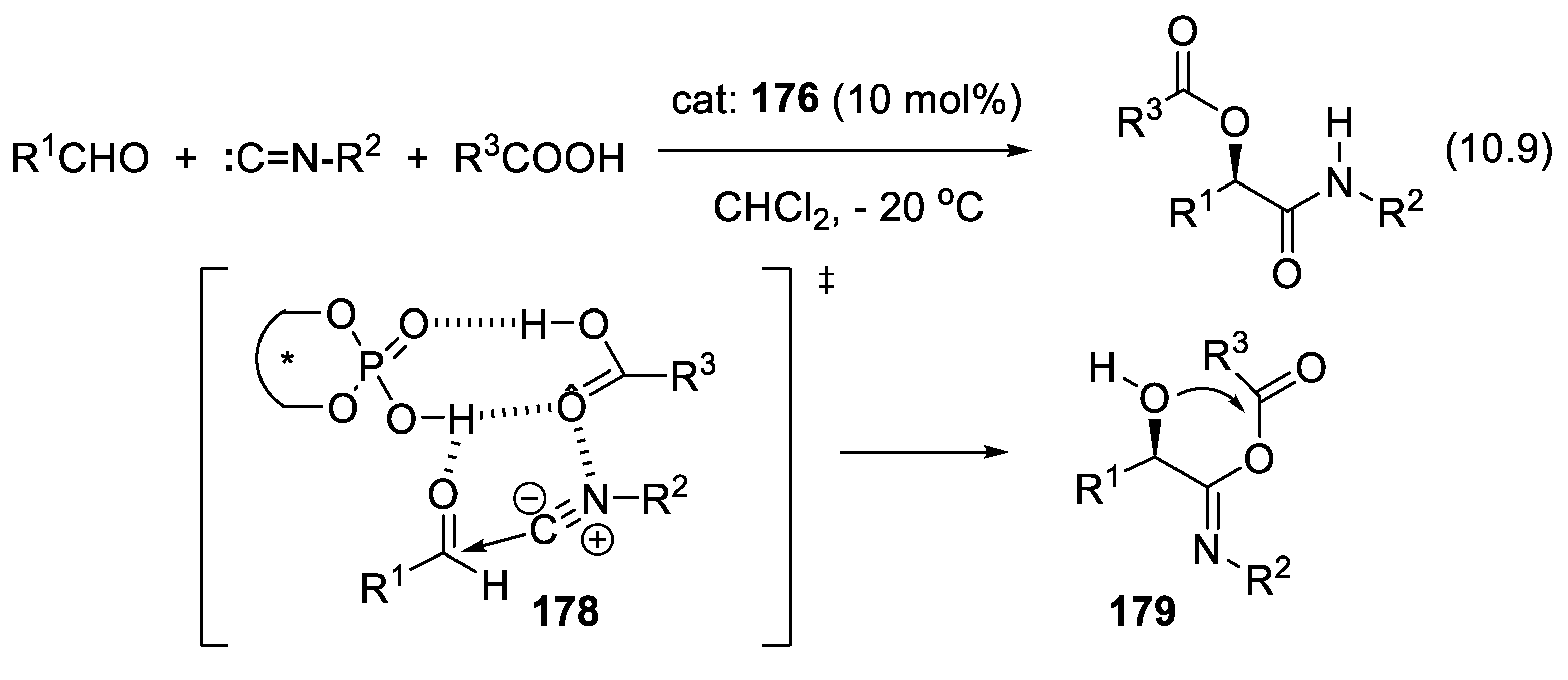

3.8. Asymmetric Amine Catalyzed Multicomponent Synthesis

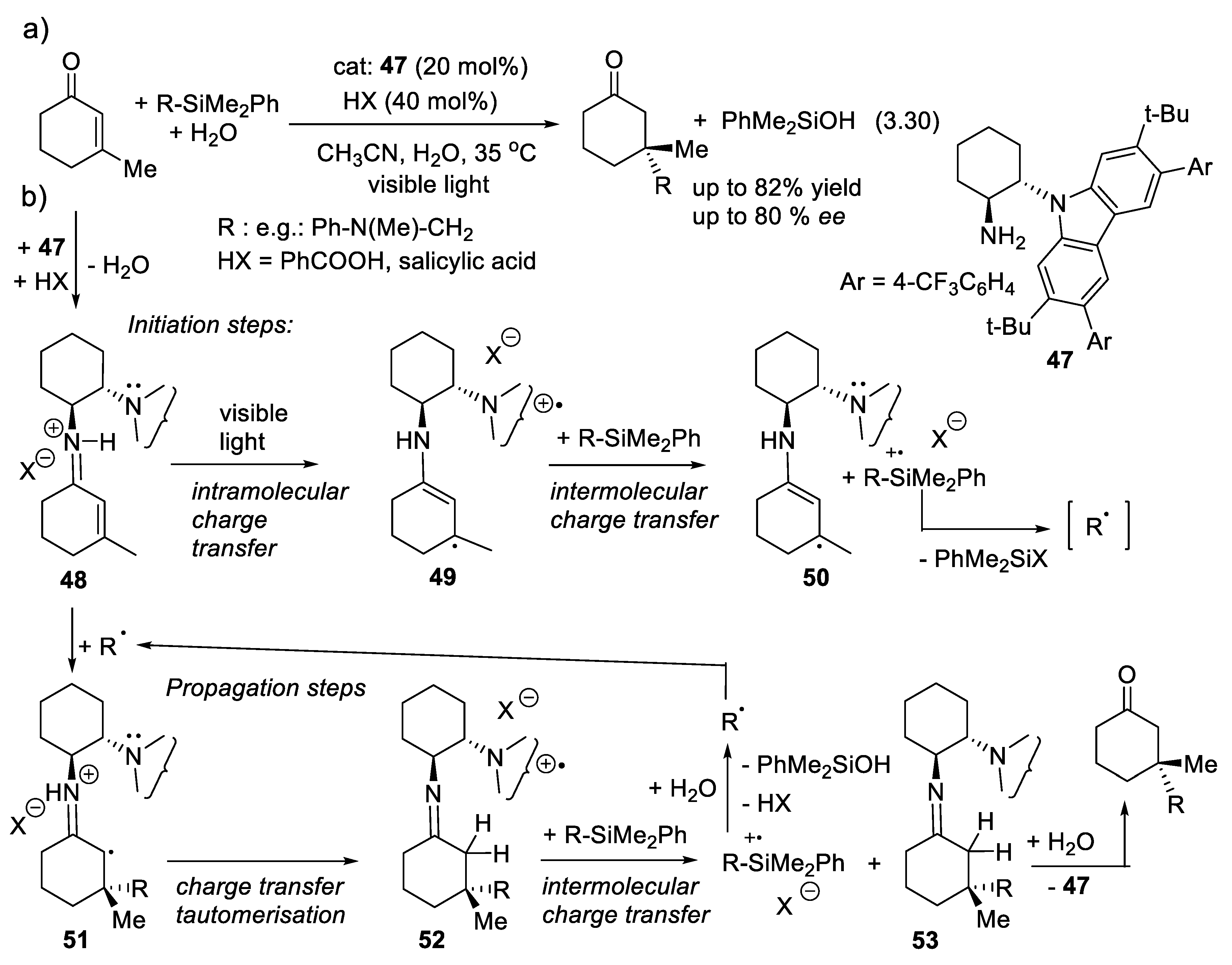

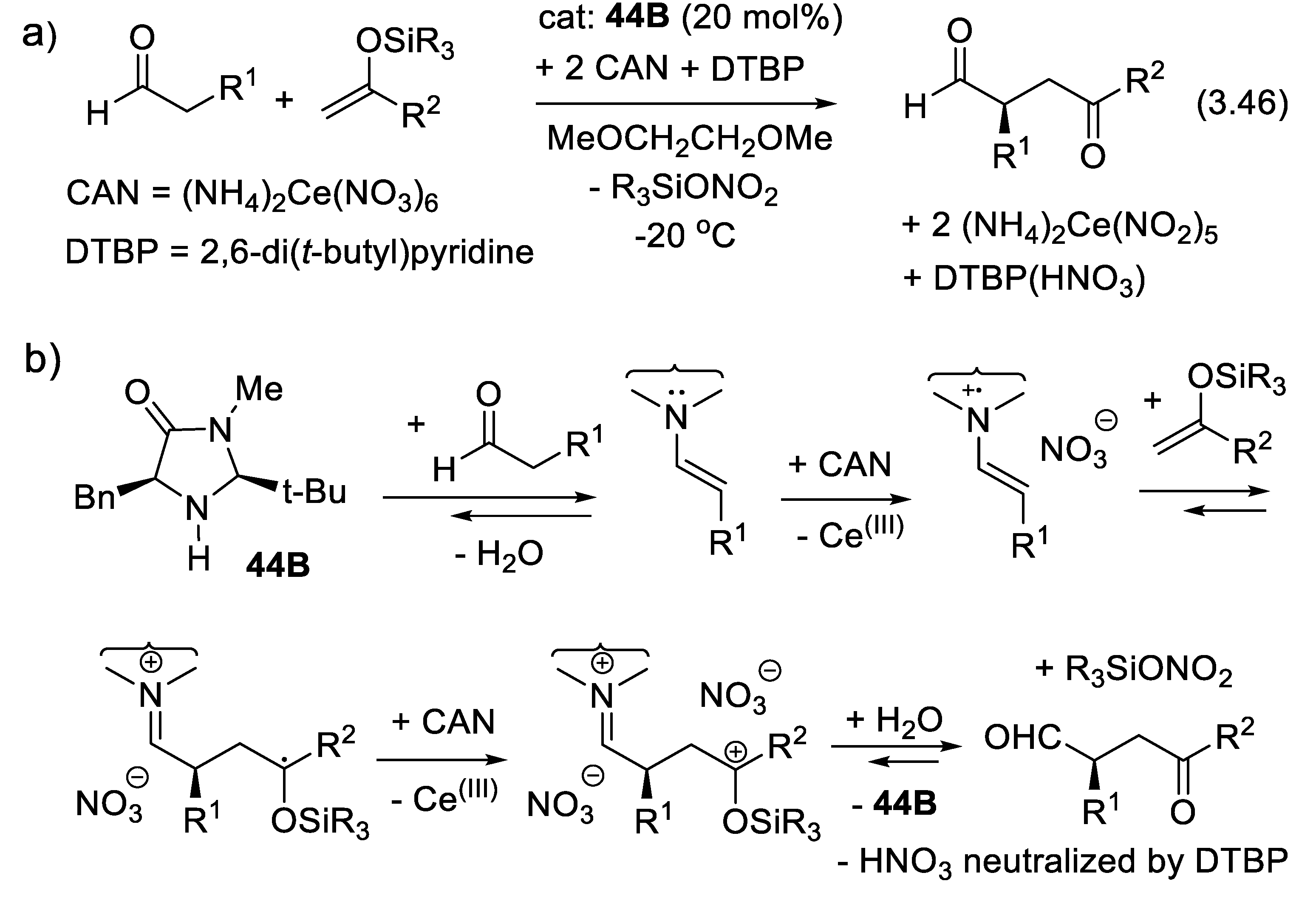

3.9. Ene-Aminium Radical-Cation Mode of Activation

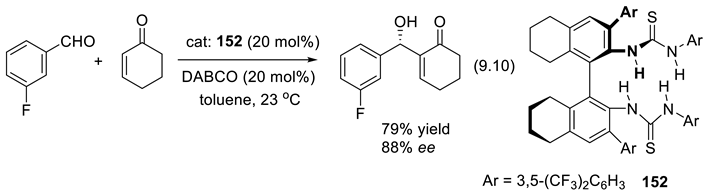

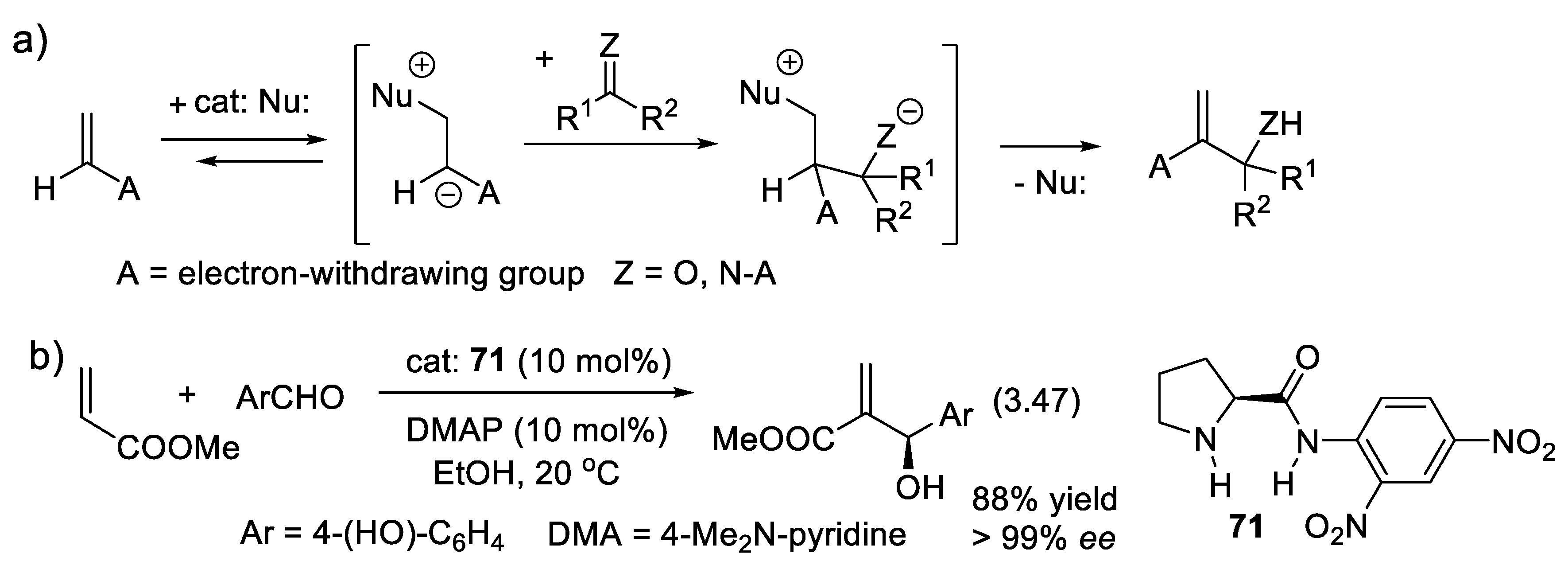

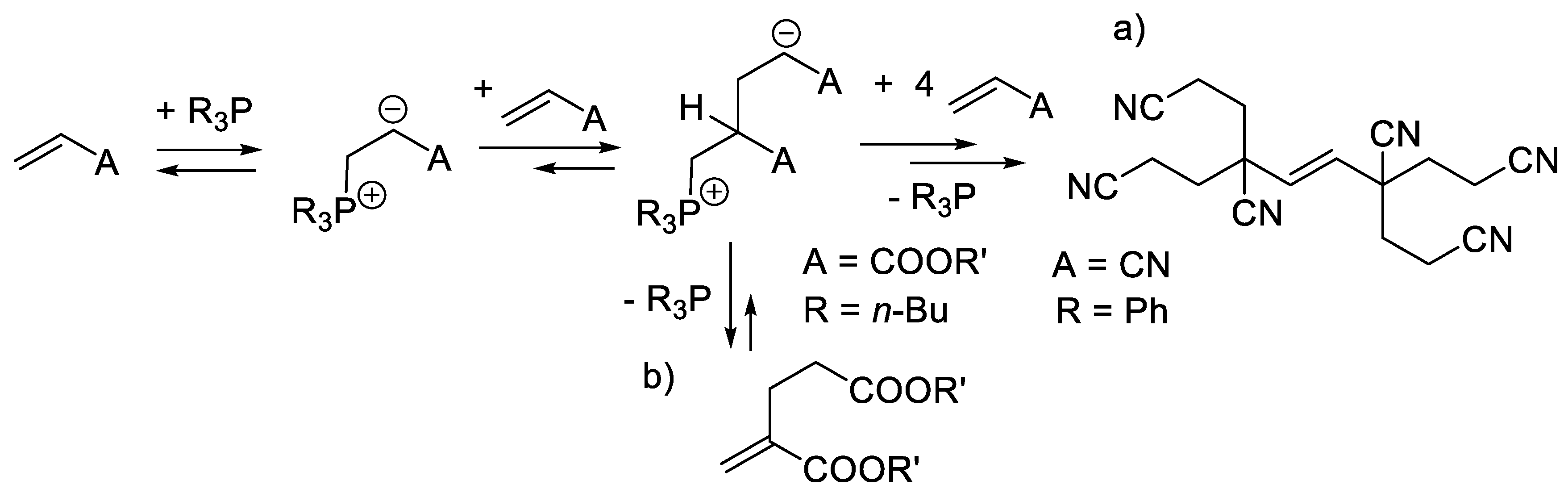

3.10. Asymmetric Morita-Baylis-Hillman Reactions Catalyzed by Amines

3.11. Chiral Lewis Bases That Are Not Amines as Organo-Catalysts

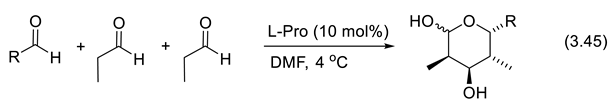

3.11.1. Chiral Guadinines

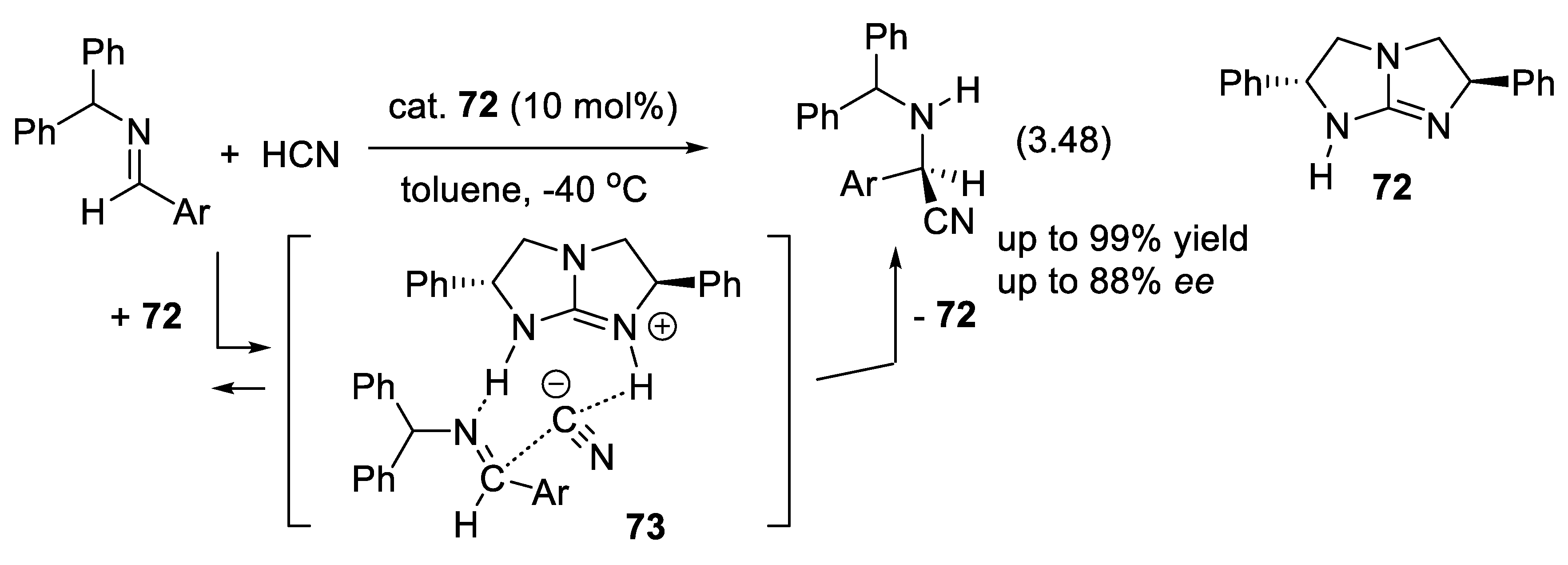

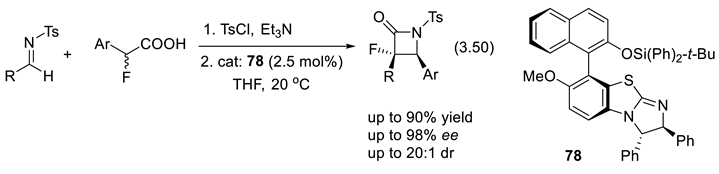

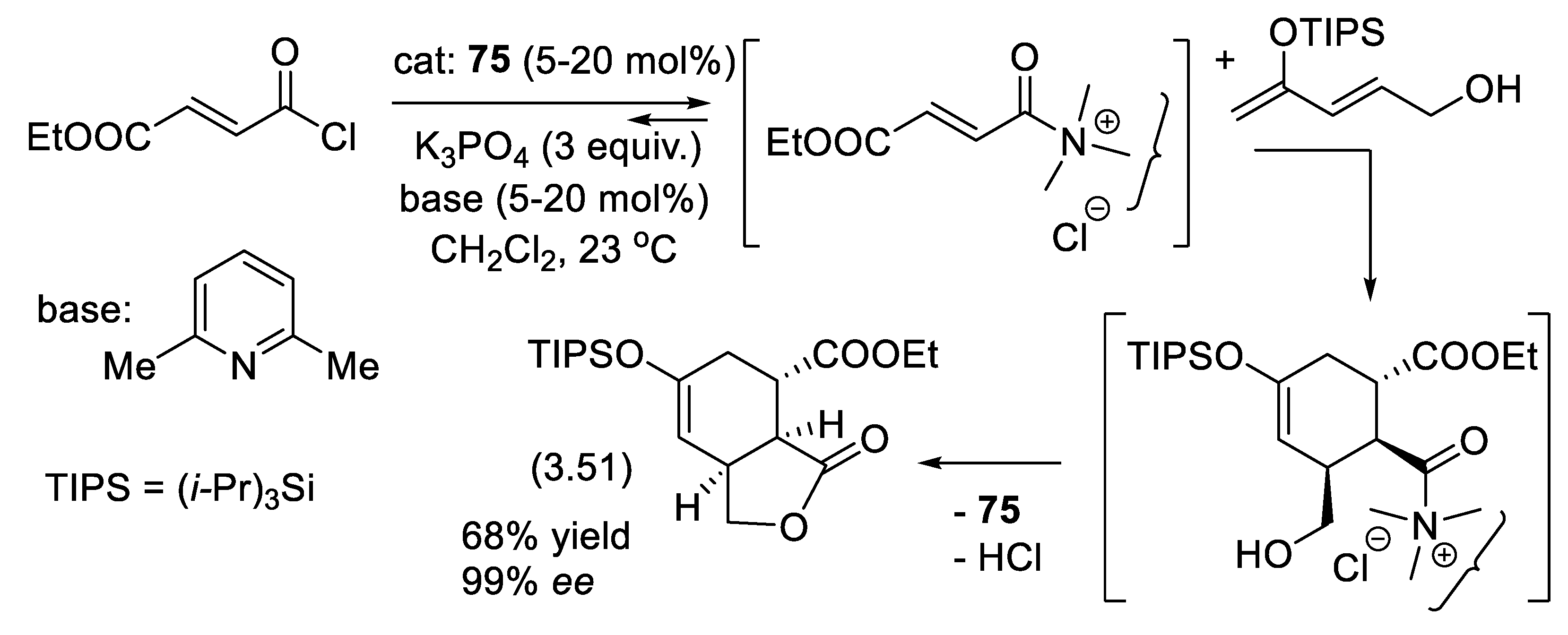

3.11.2. Benzotetramisoles

3.11.3. Acylammonium Mode of Activation

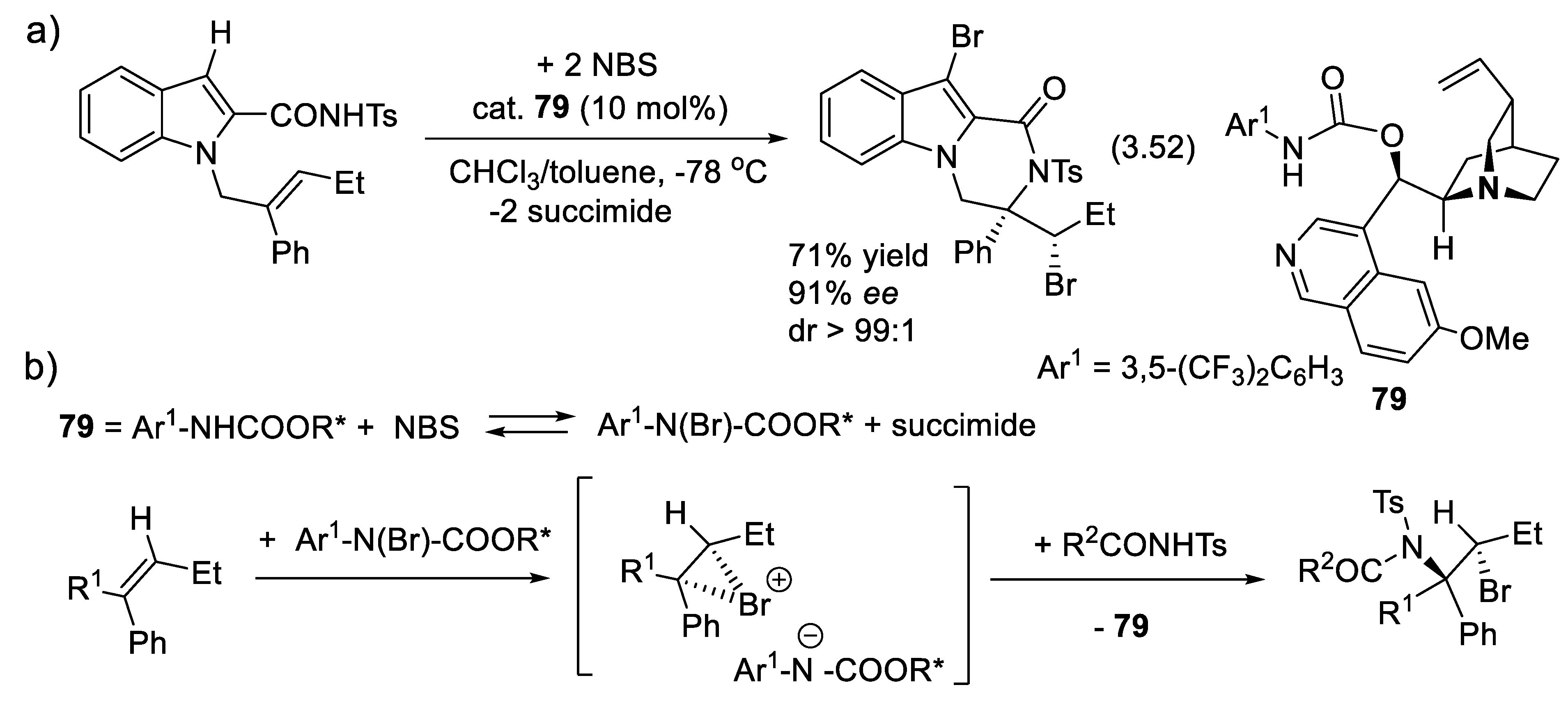

3.11.4. Carbamates

4. Asymmetric Organo-Catalysis with Peptides

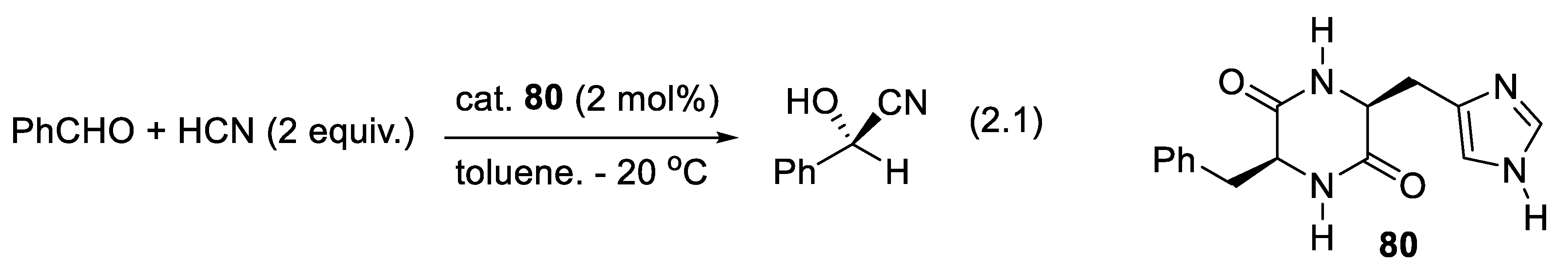

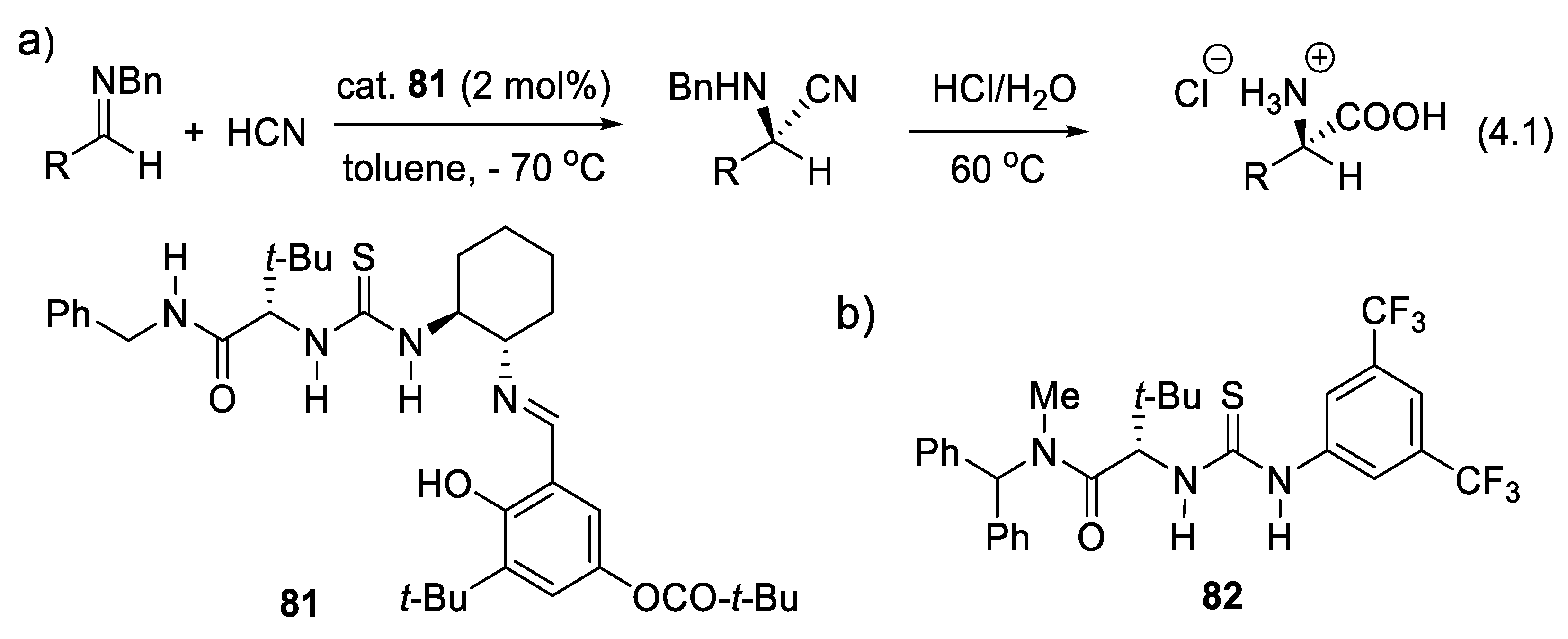

4.1. Asymmetric Hydrocyanations

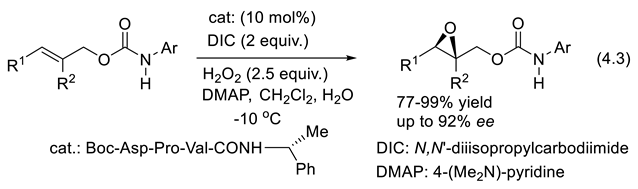

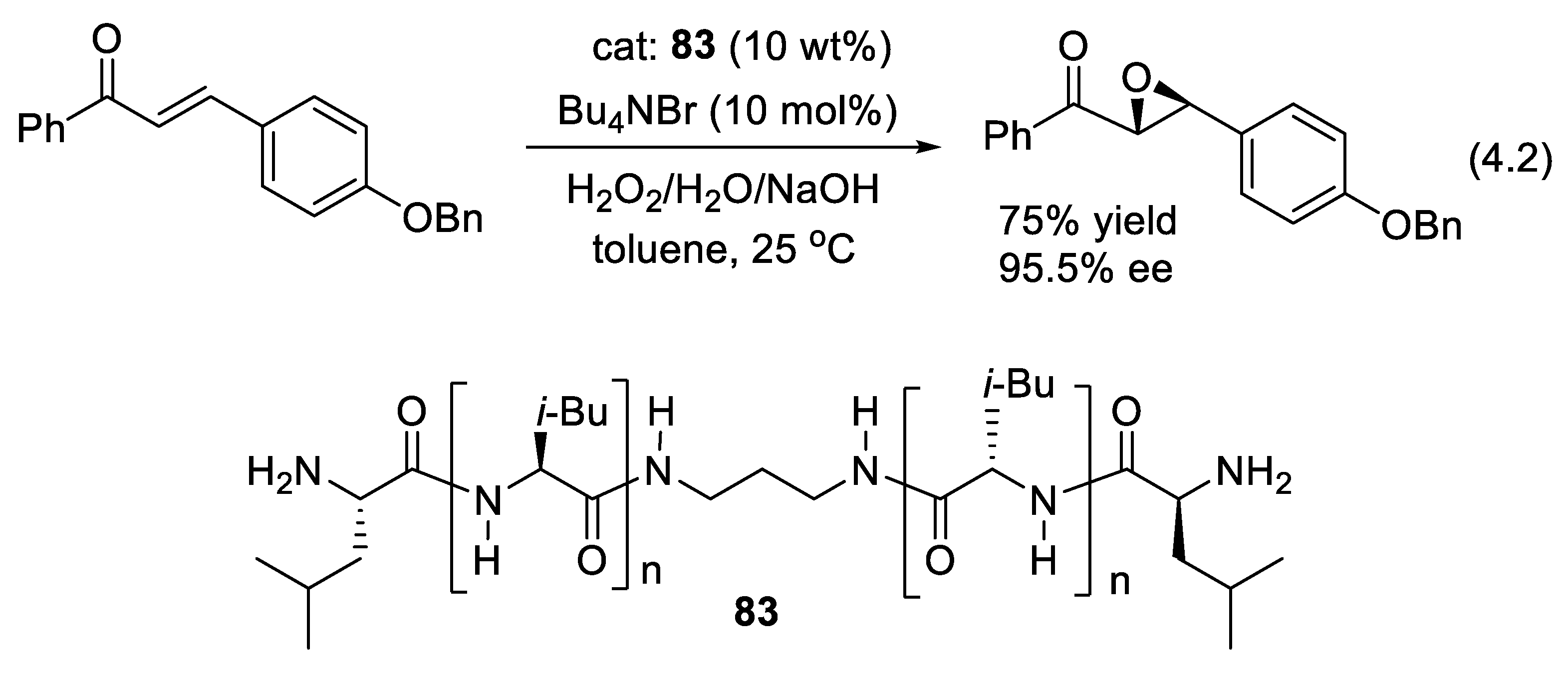

4.2. Asymmetric Oxidations

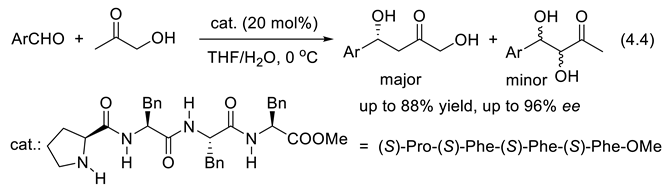

4.3. Asymmetric Intermolecular Aldol Reactions

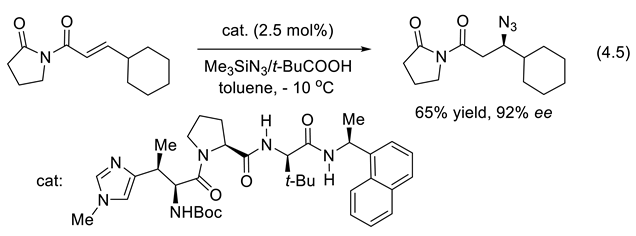

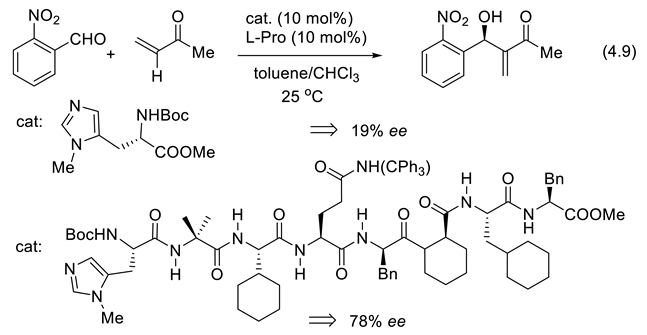

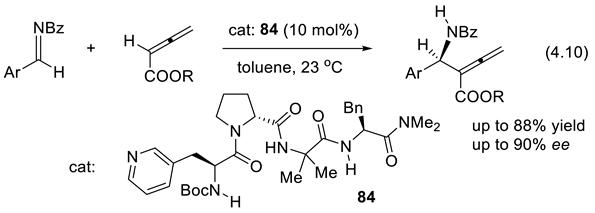

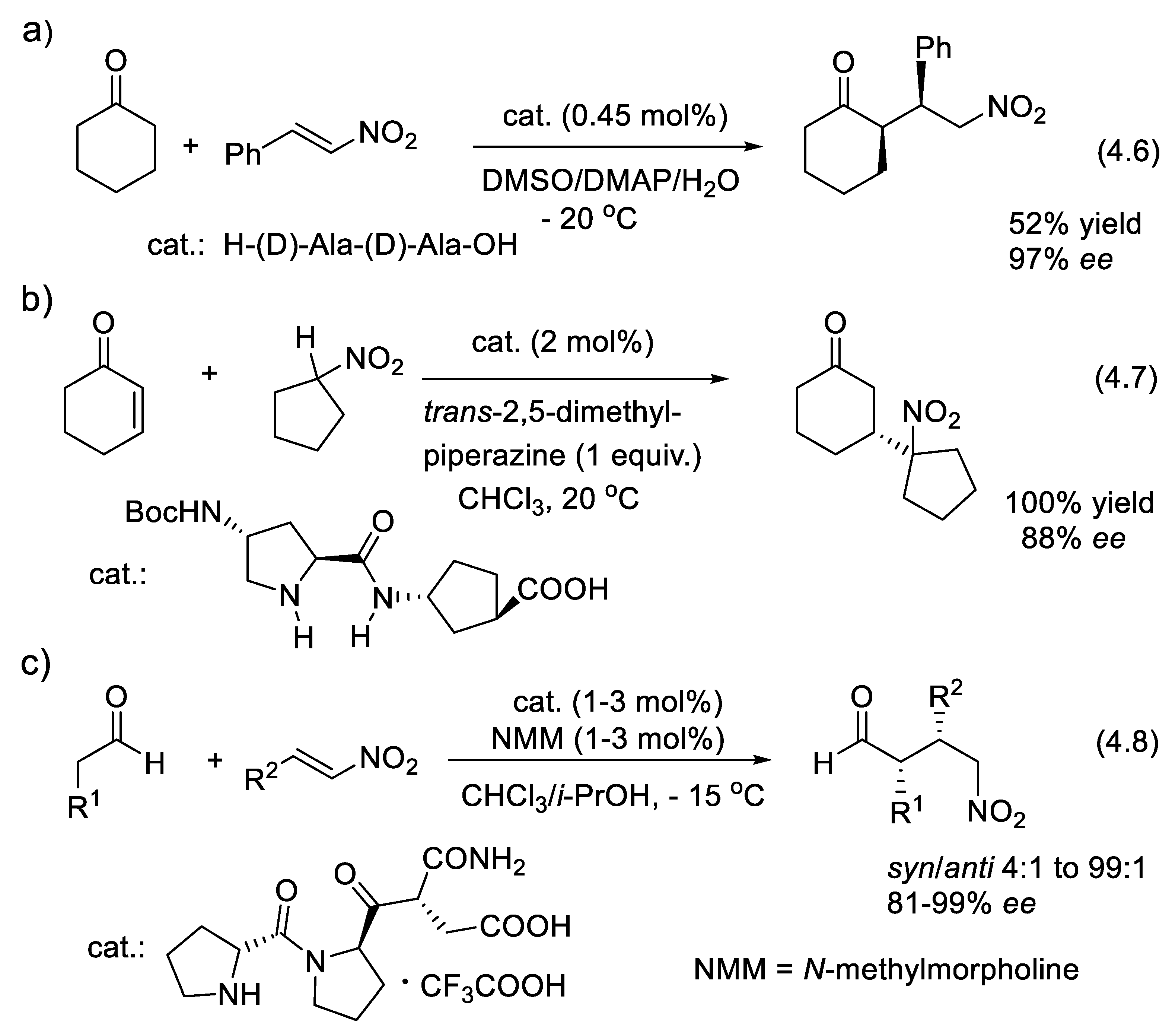

4.4. Peptide-Catalyzed Conjugate Additions

4.5. Peptide-Catalyzed Morita-Baylis-Hillman Reaction

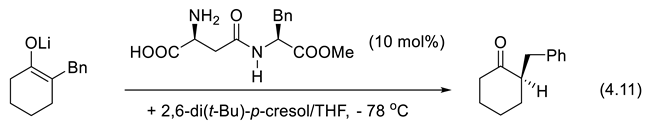

4.6. Catalytic Enantioselective Enolate Protonation by Peptides

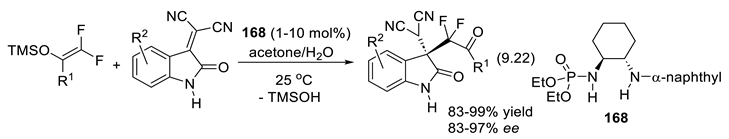

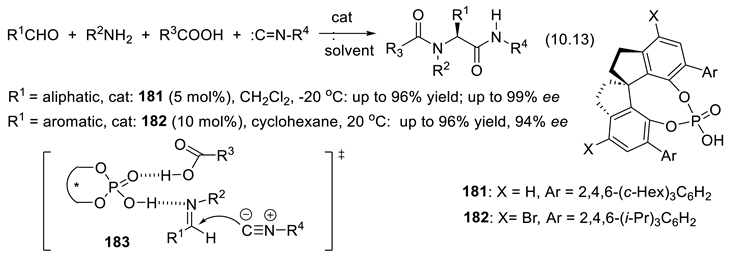

5. Phosphorous-Based Catalysis

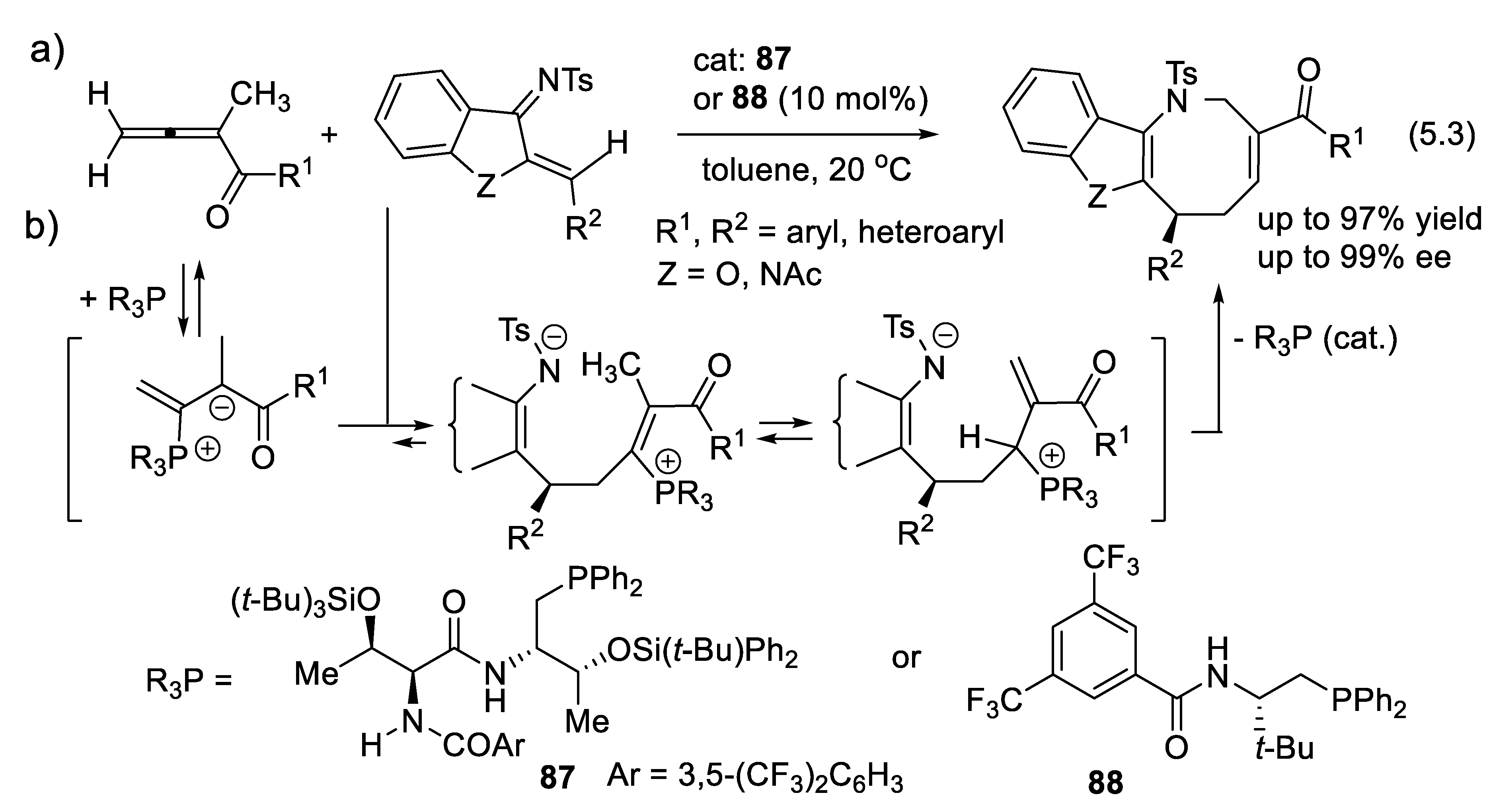

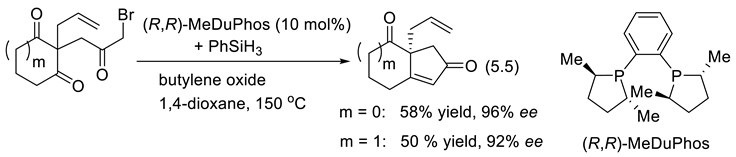

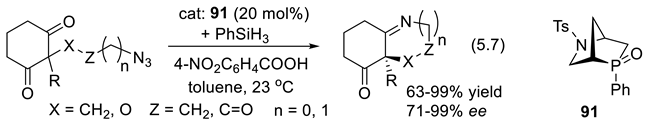

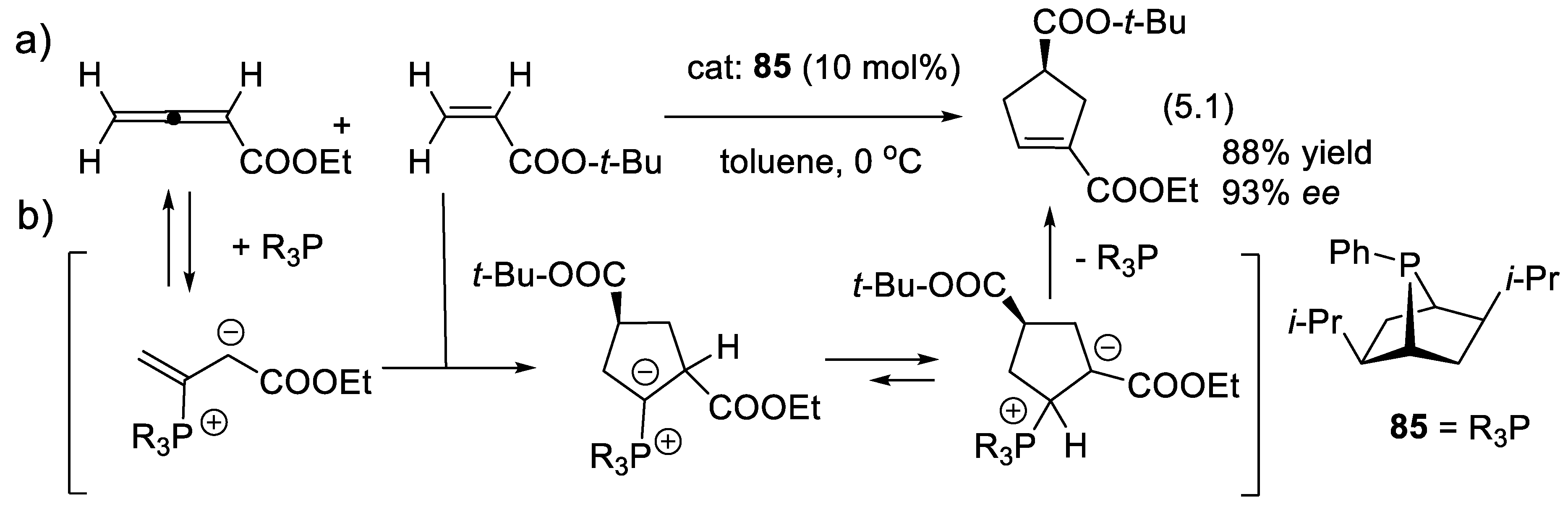

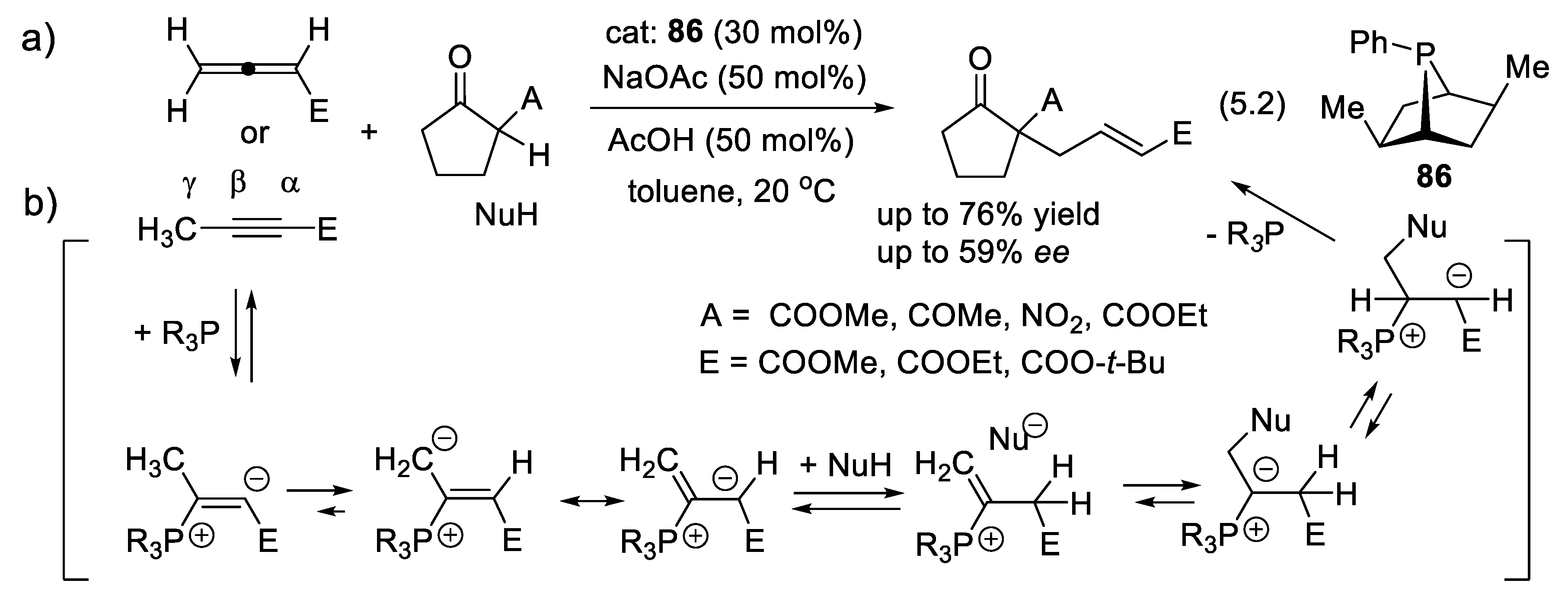

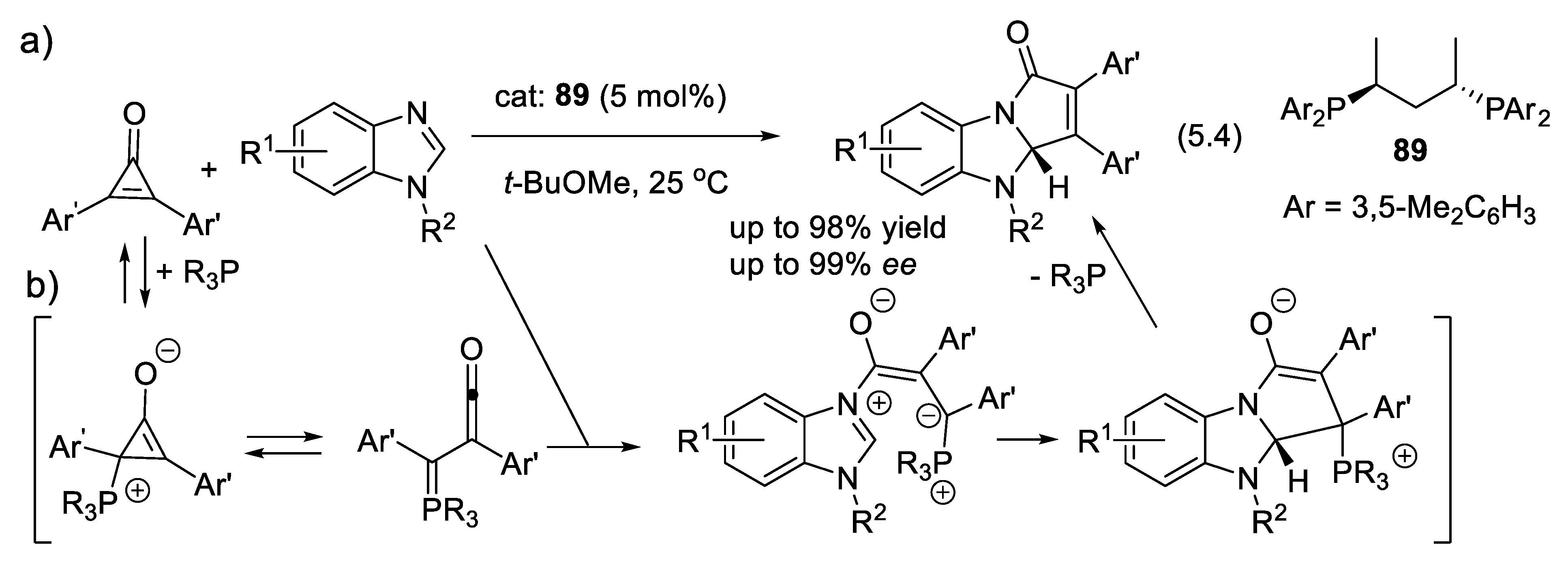

5.1. Nucleophilic Activation by Chiral Phosphines

5.2. Enantioselective Wittig and Staudinger-Aza-Wittig Reactions

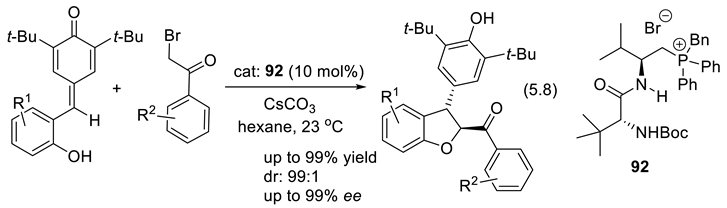

5.3. Chiral Phosphonium Salts as Phase Transfer Catalysts

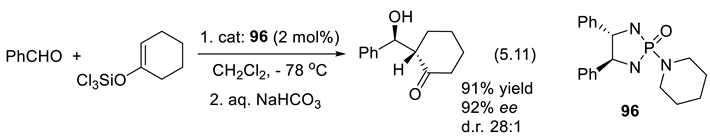

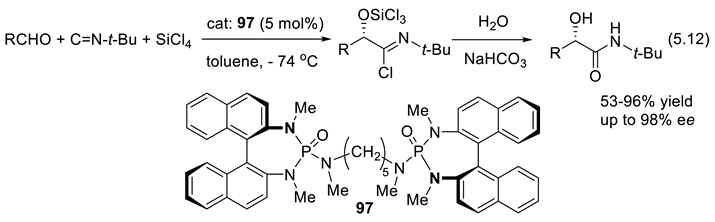

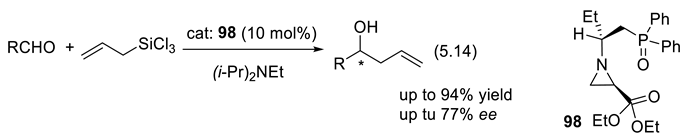

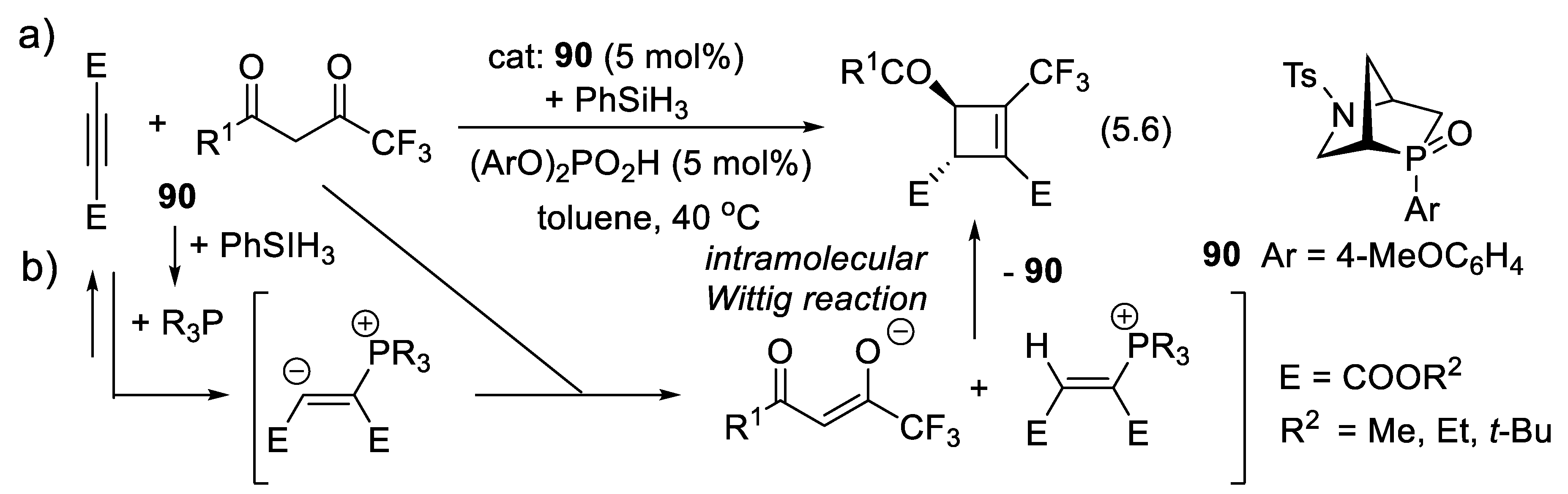

5.4. Chiral Phosphoramides as Lewis Base Catalysts

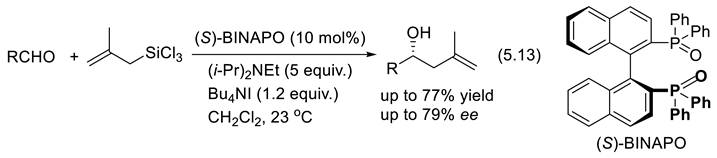

5.5. Chiral Phosphine Oxides as Organocatalysts

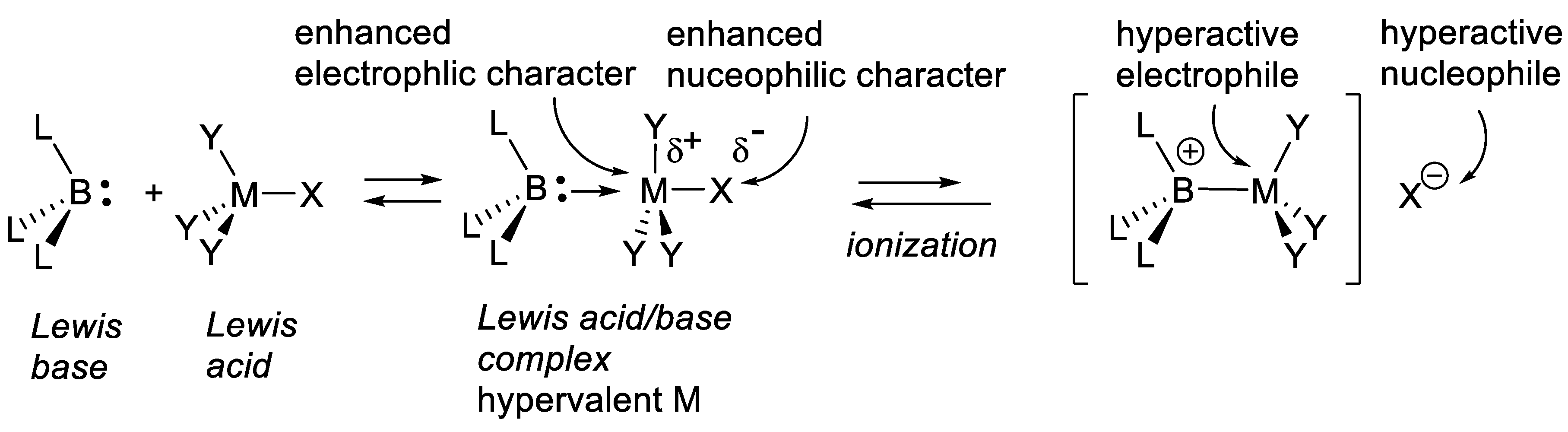

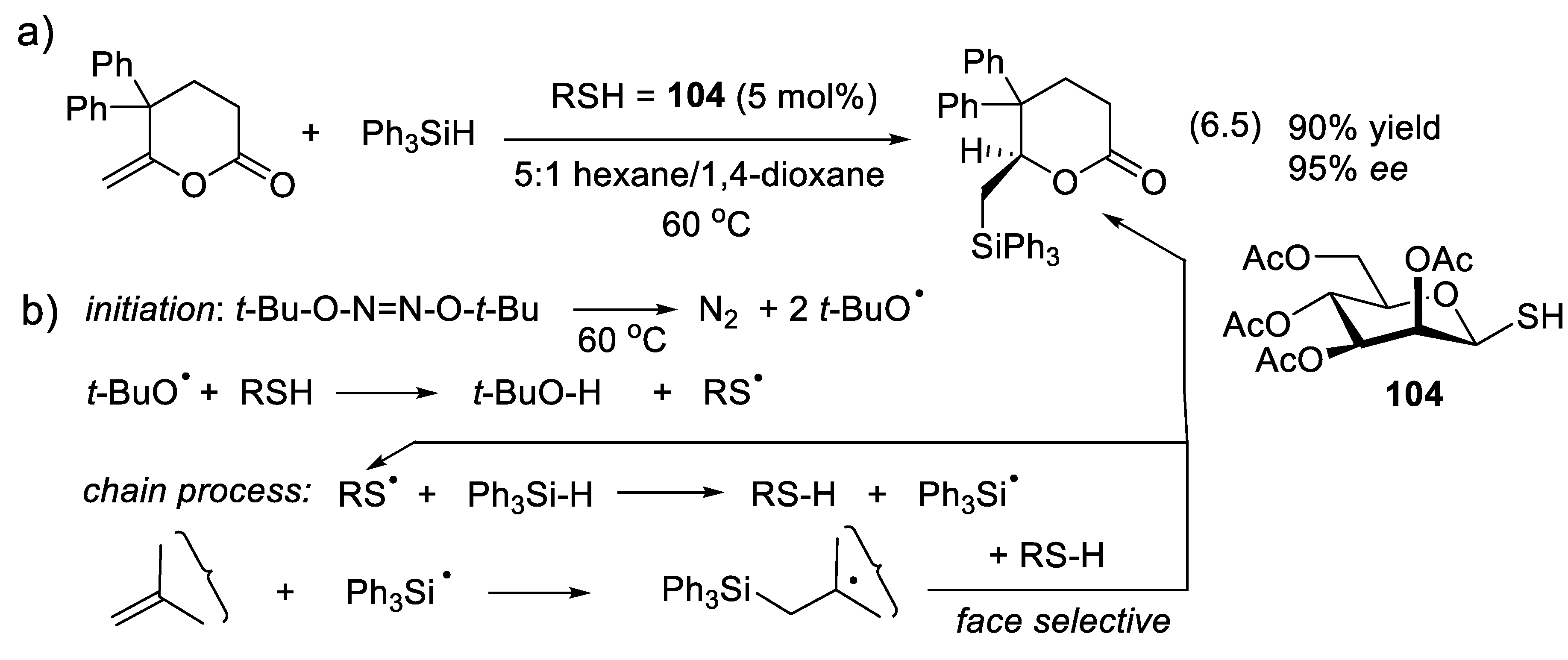

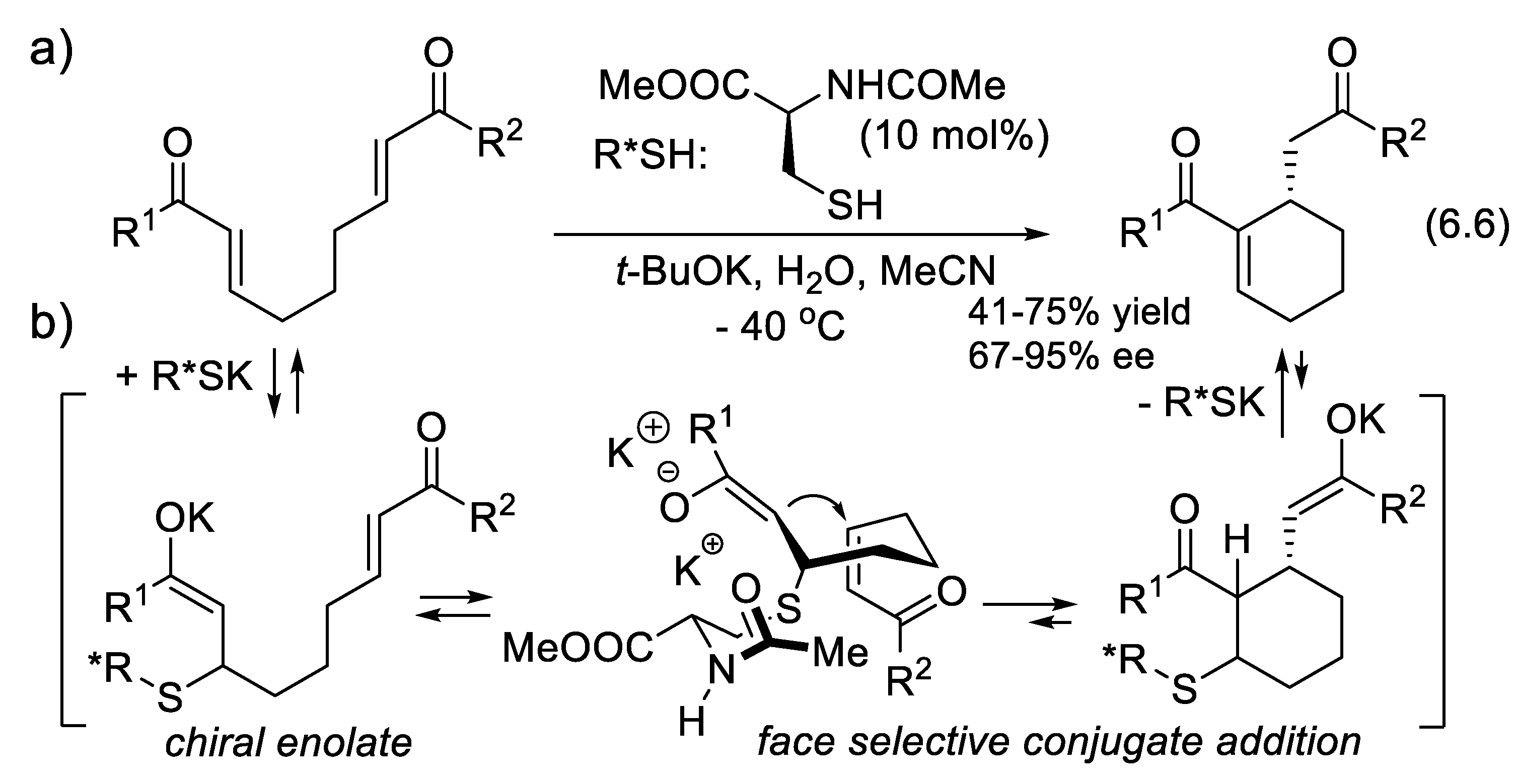

6. Asymmetric Organocatalysis by Sulfur Compounds

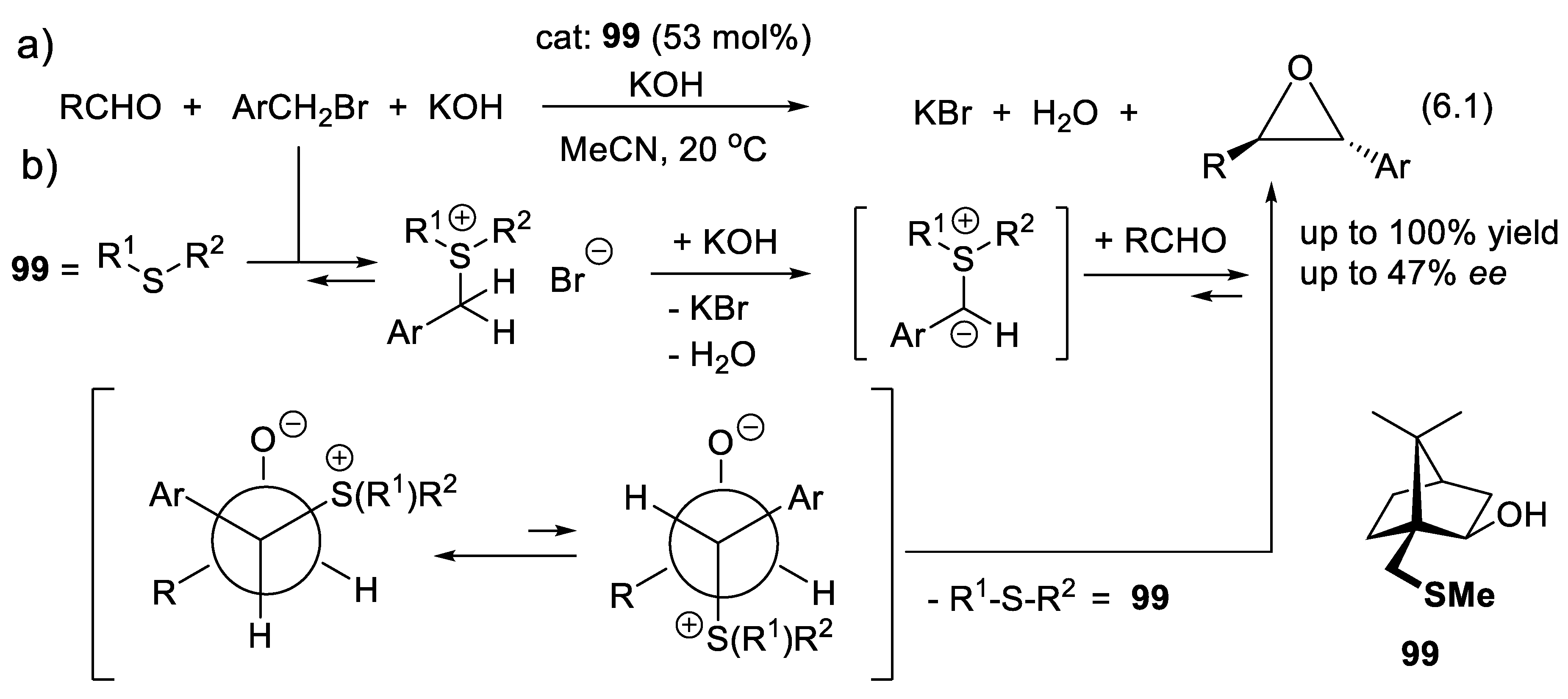

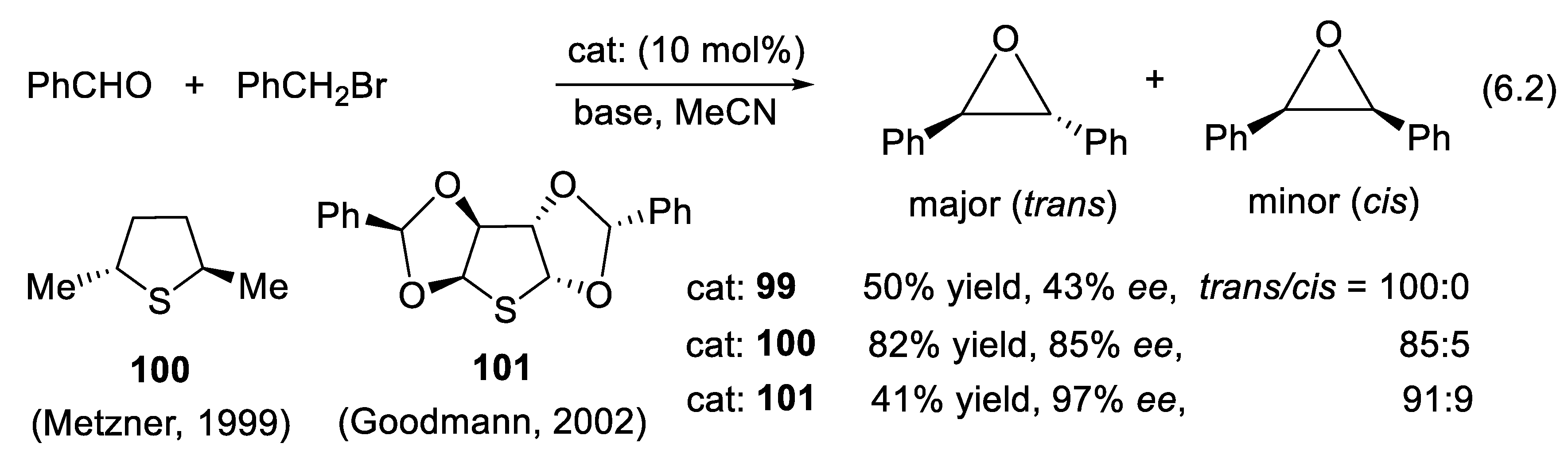

6.1. Asymmetric Aldehyde Epoxidations Catalyzed by Chiral Dialkylsulfides

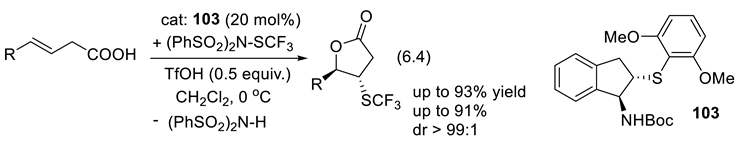

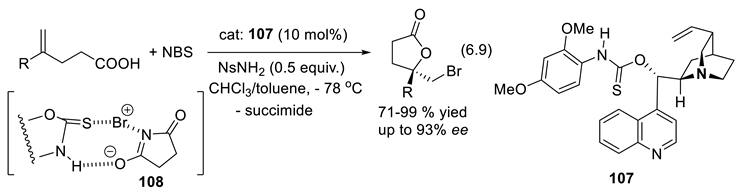

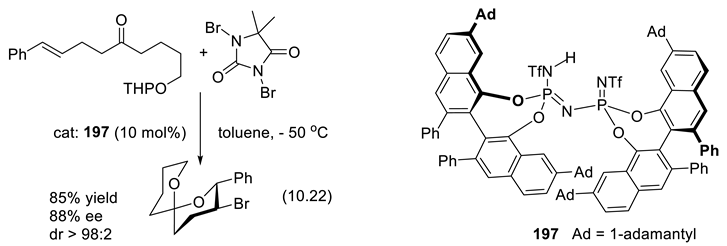

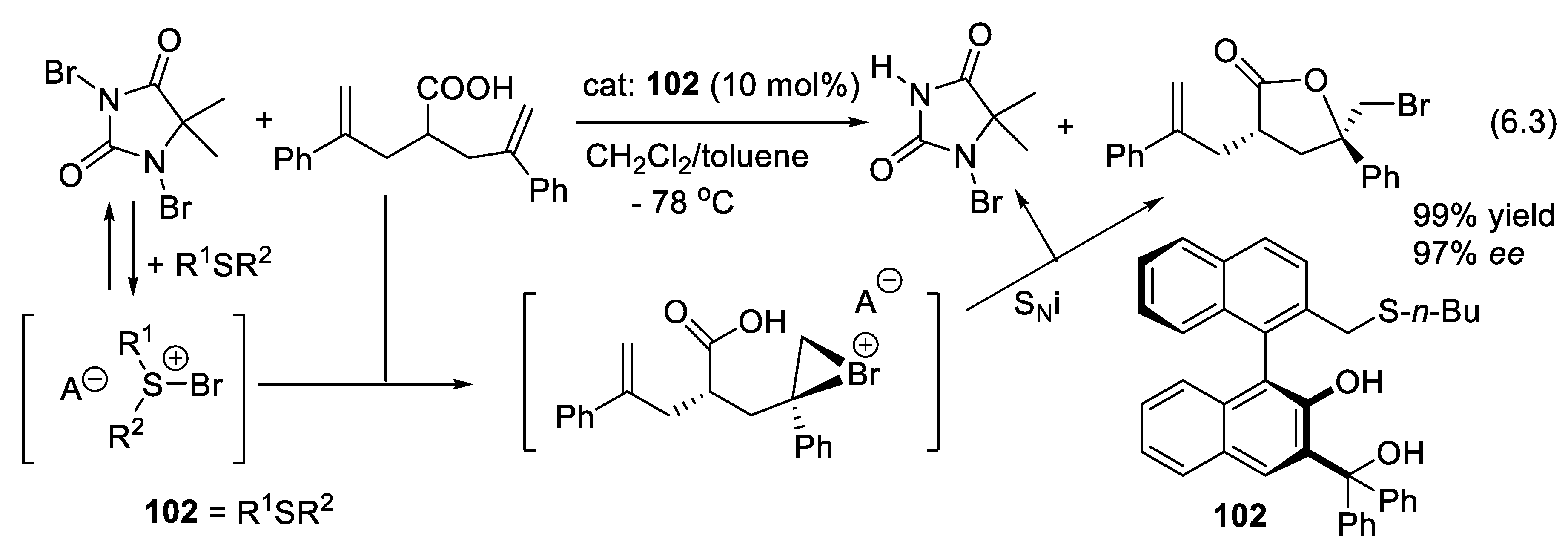

6.2. Asymmetric Halo- and Chalcolactonization Catalyzed by Sulfides

6.3. Enantioselective Hydrogen-Atom Transfer Catalyzed by Chiral Thiols

6.4. Asymmetric Rauhut-Currier Reaction Catalyzed by a Chiral Thiols

6.5. Sulfonium Salts as Chiral PTCs

6.6. Chiral Sulfoxides

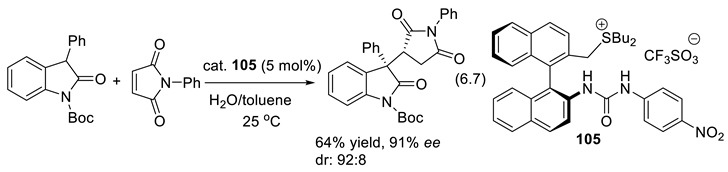

6.7. Chiral Amino-Thiocarbamates

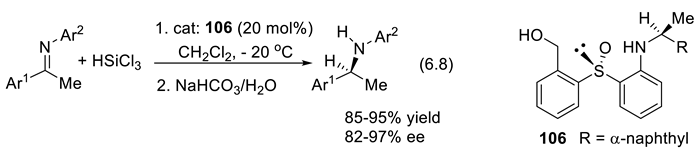

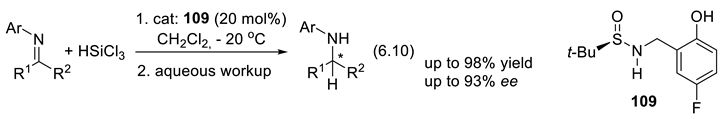

6.8. Chiral Sulfinamides

6.9. Chiral Thiophosphoramides

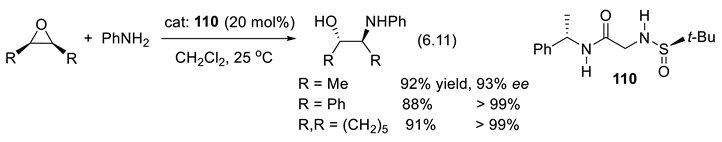

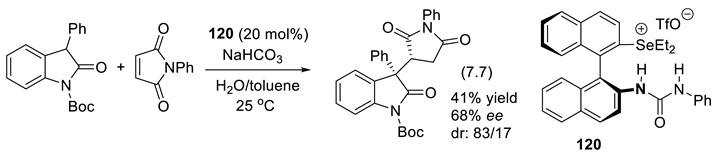

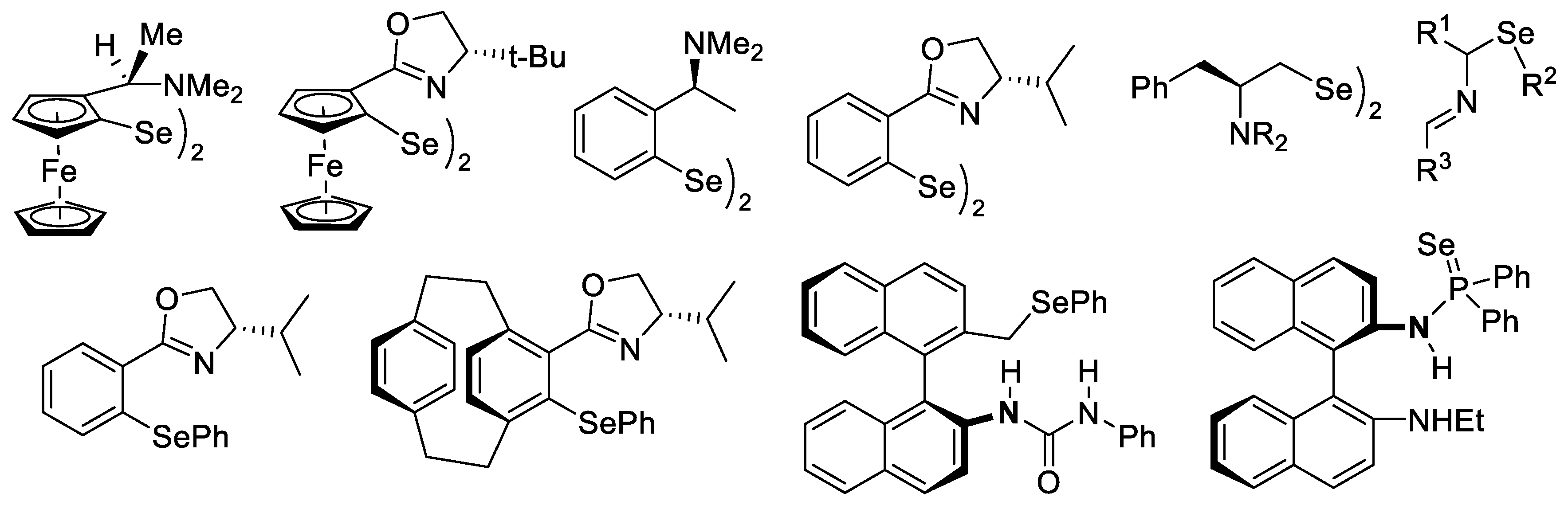

7. Asymmetric Catalysis with Organo-Selenium Compounds

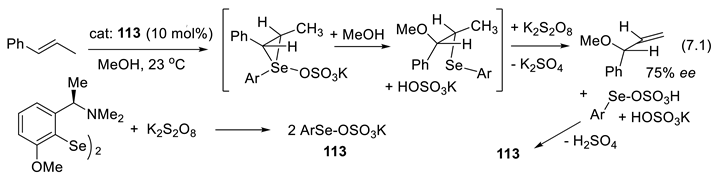

7.1. Aminodiselenides as Chiral Pre-Catalysts

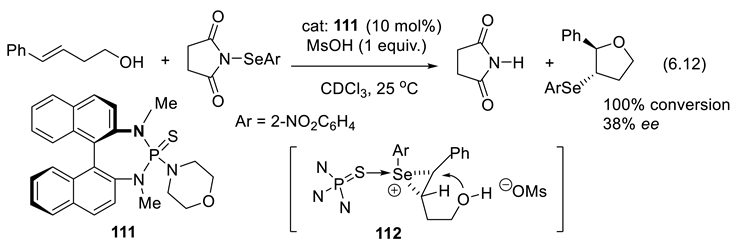

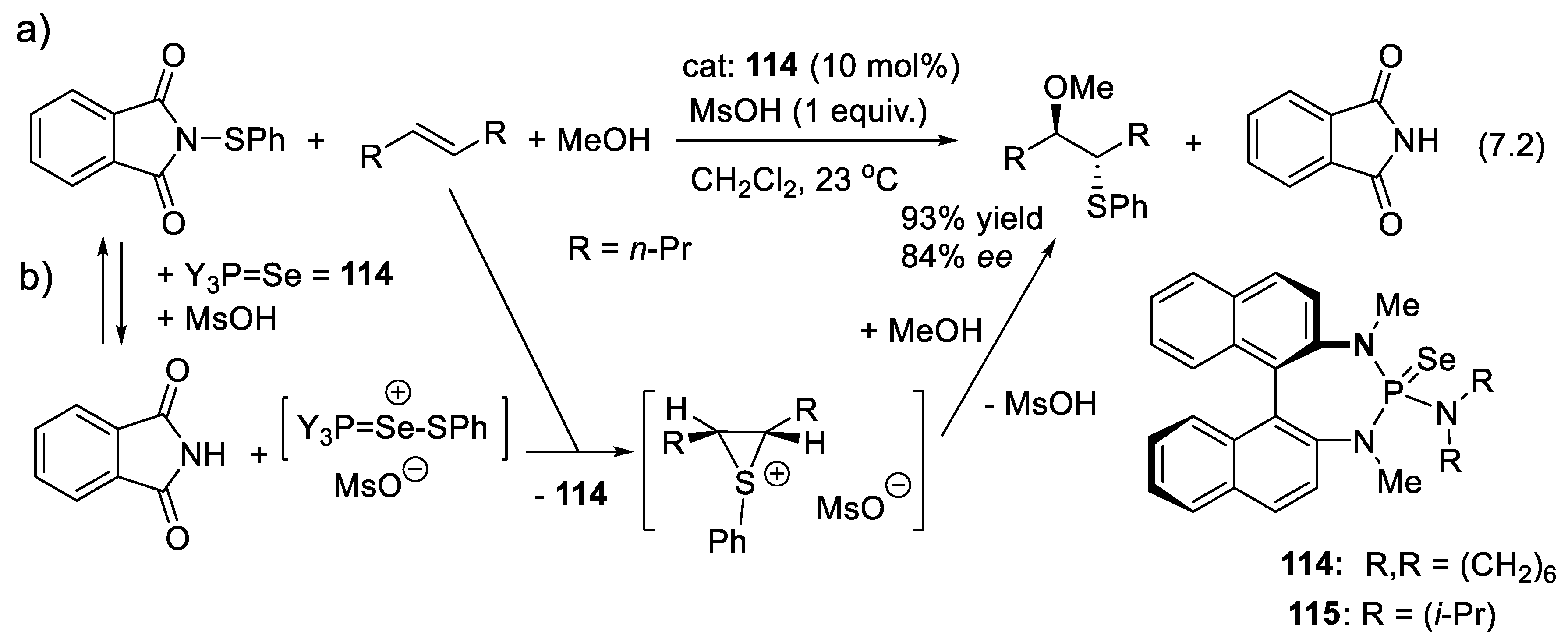

7.2. Selenophosphoramides as Chiral Catalyts

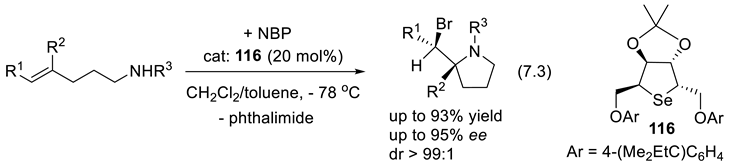

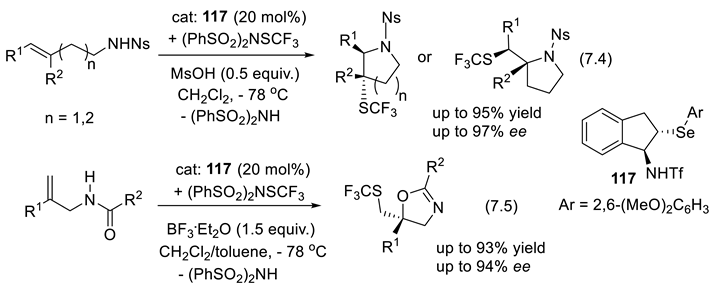

7.3. Selenides as Chiral Catalysts

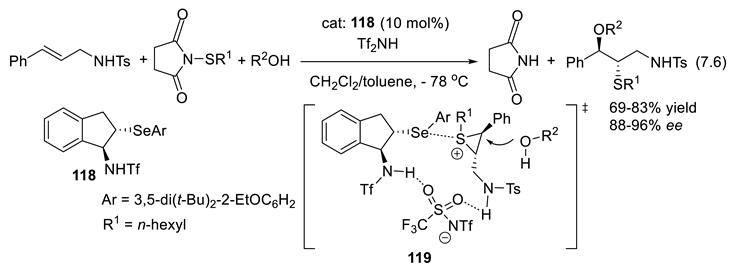

7.4. Chiral Trivalent Selenonium Salts as PTCs

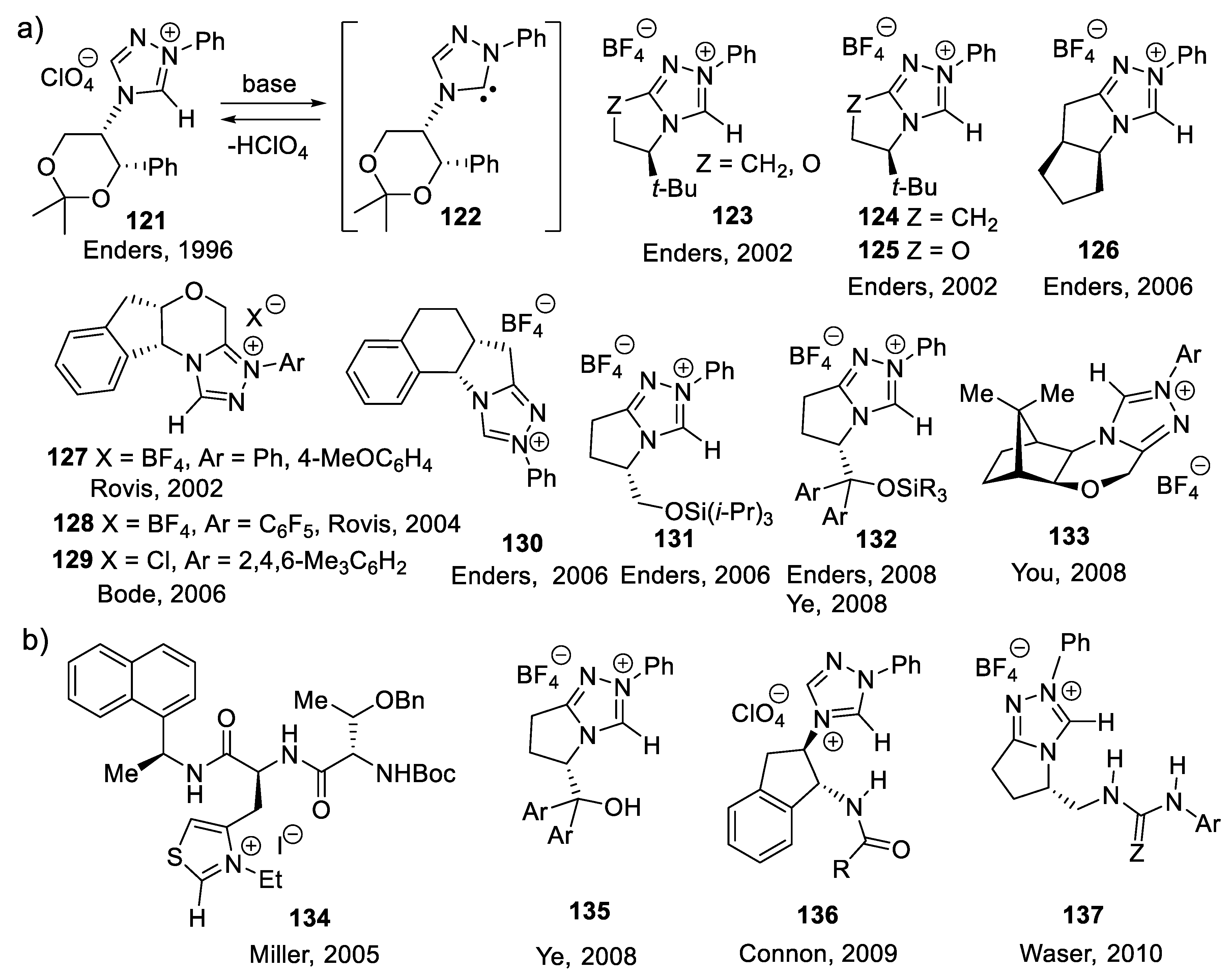

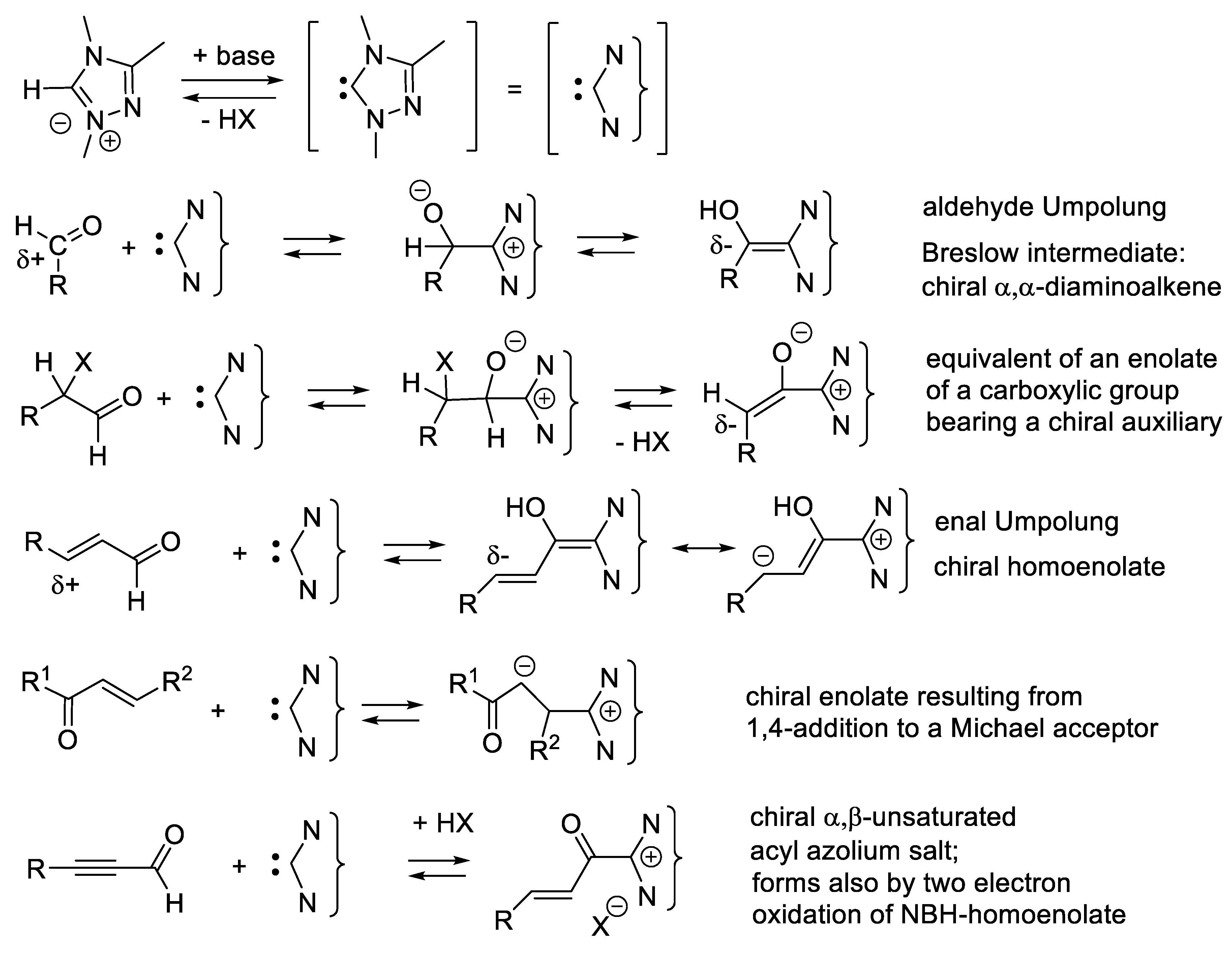

8. Asymmetric Organocatalysis with Electron-Rich Carbene Intermediates

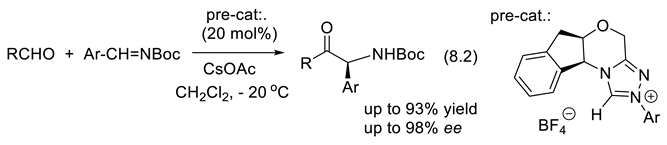

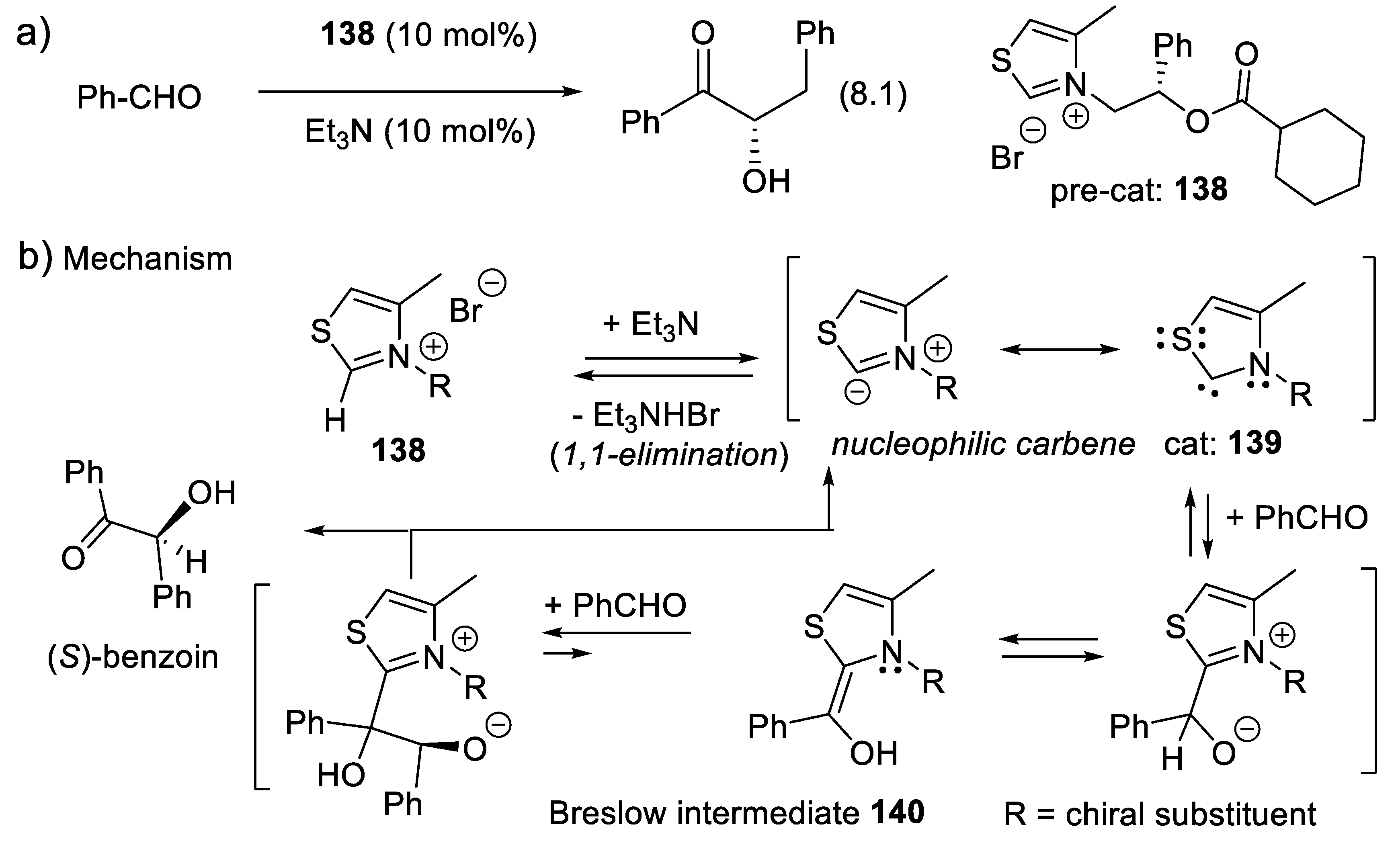

8.1. NHC-Catalyzed Asymmetric Benzoin Condensations

8.2. NHC-Catalyzed Asymmetric Aza-Benzoin Condensations

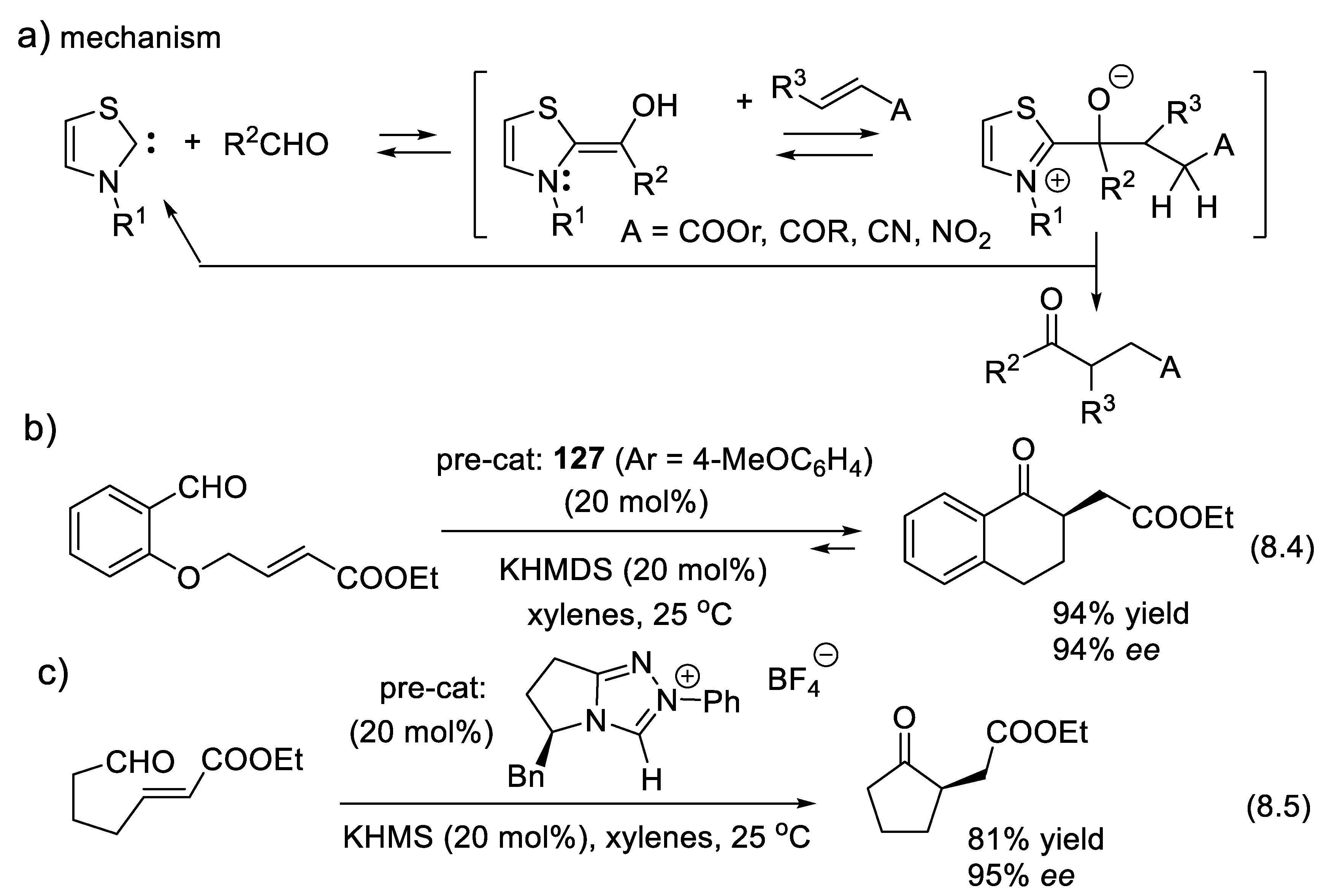

8.3. NHC-Catalyzed Asymmetric Stetter Reactions

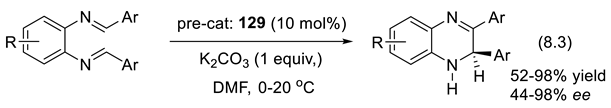

8.4. NHC-Catalyzed Asymmetric Aza-Stetter Reactions

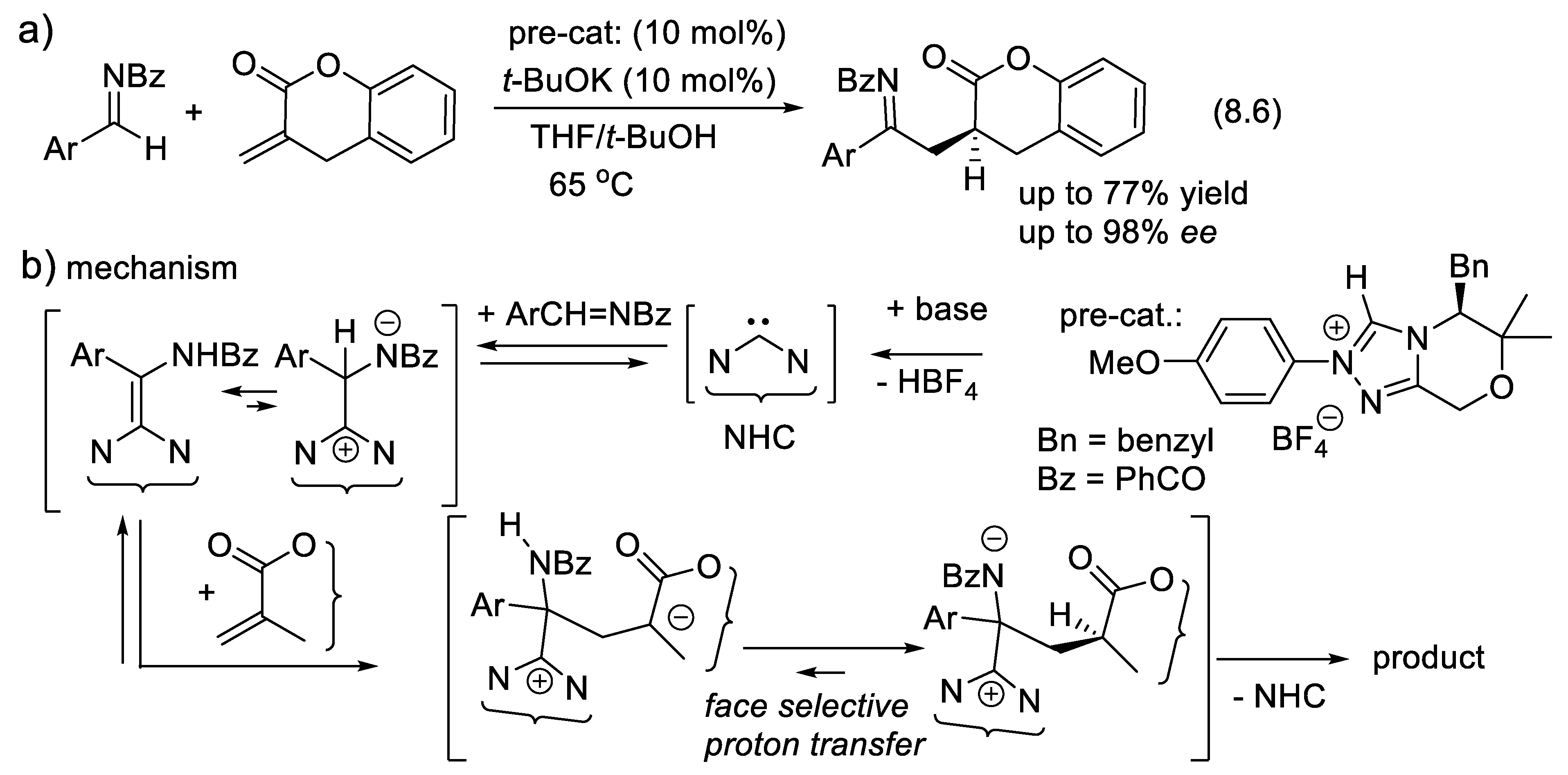

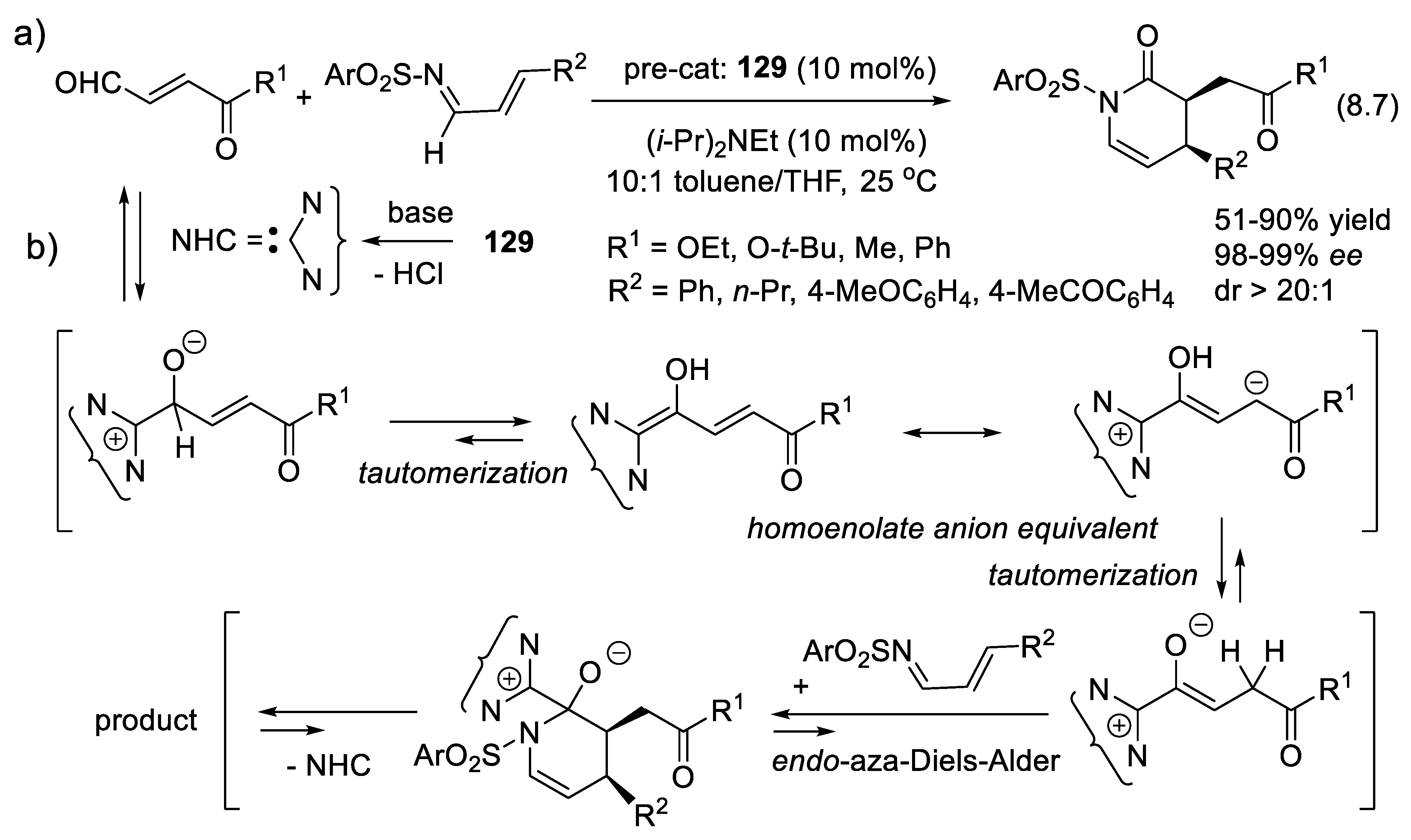

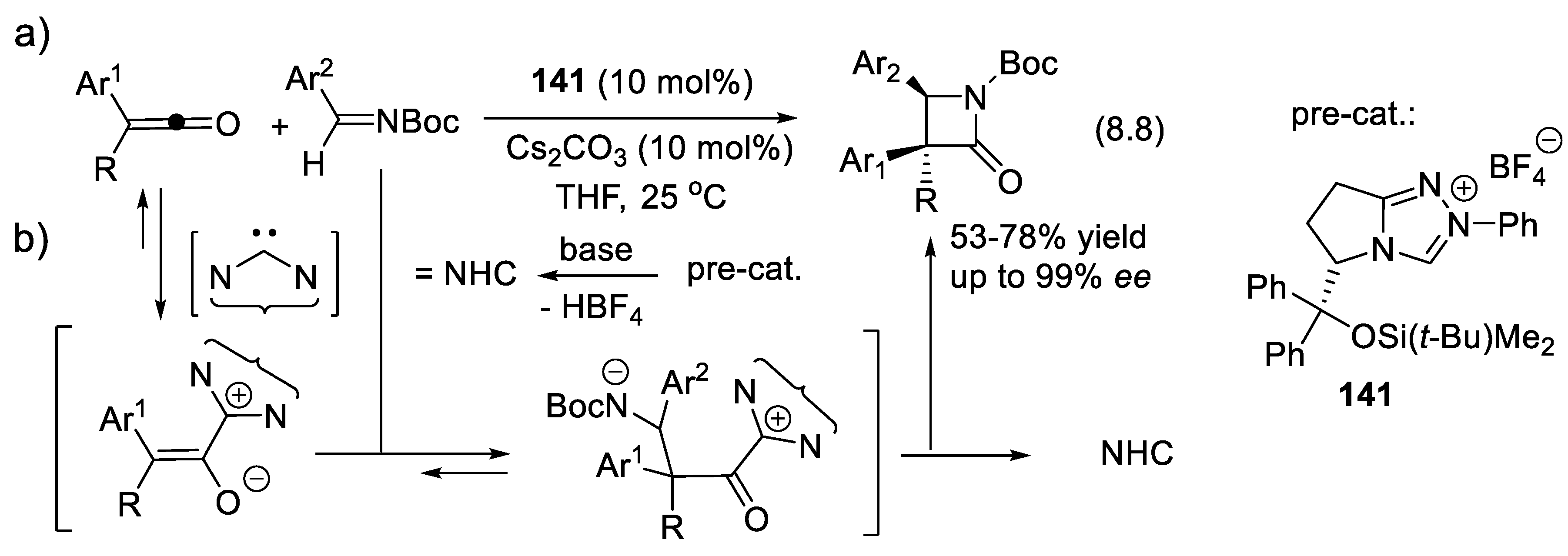

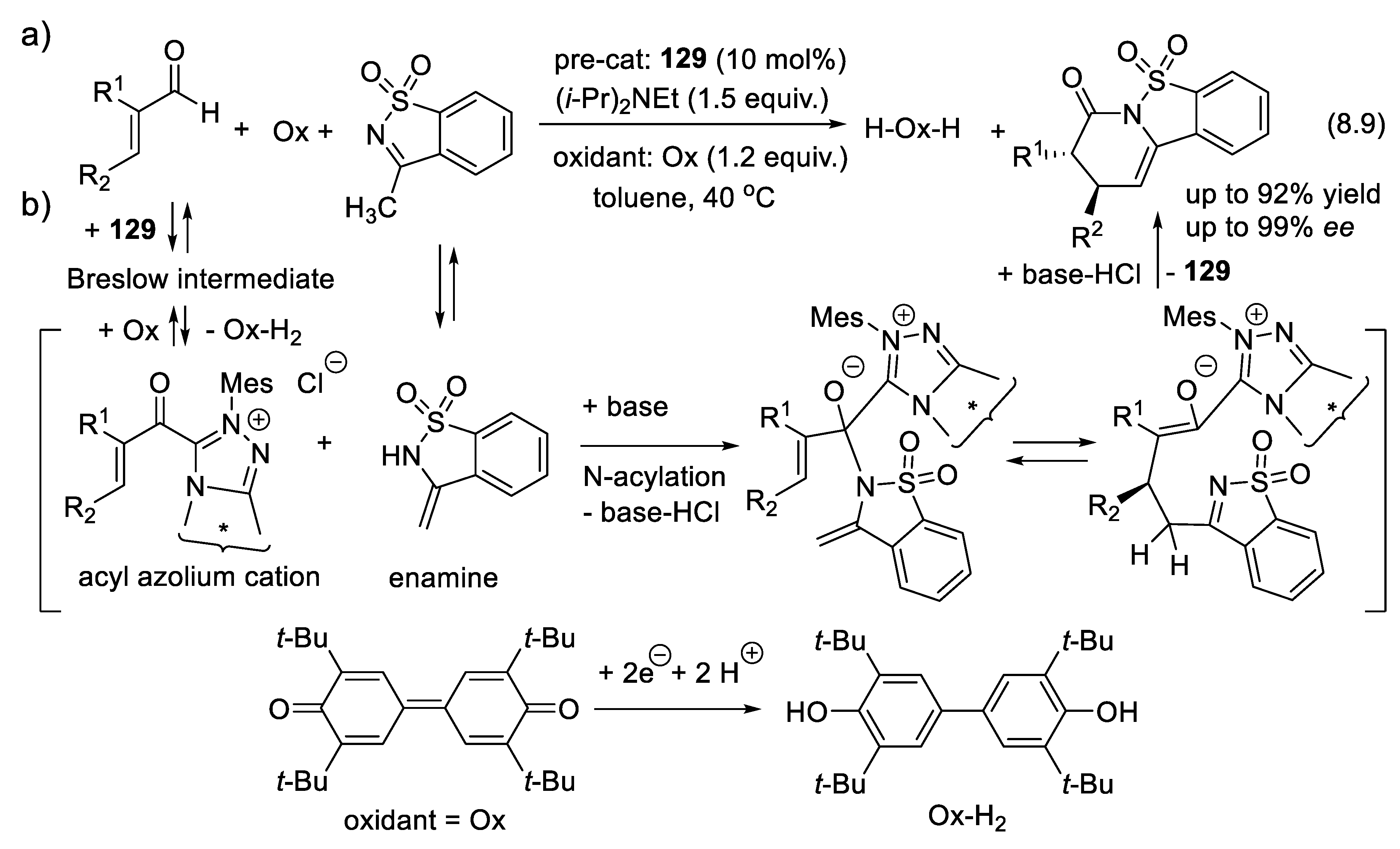

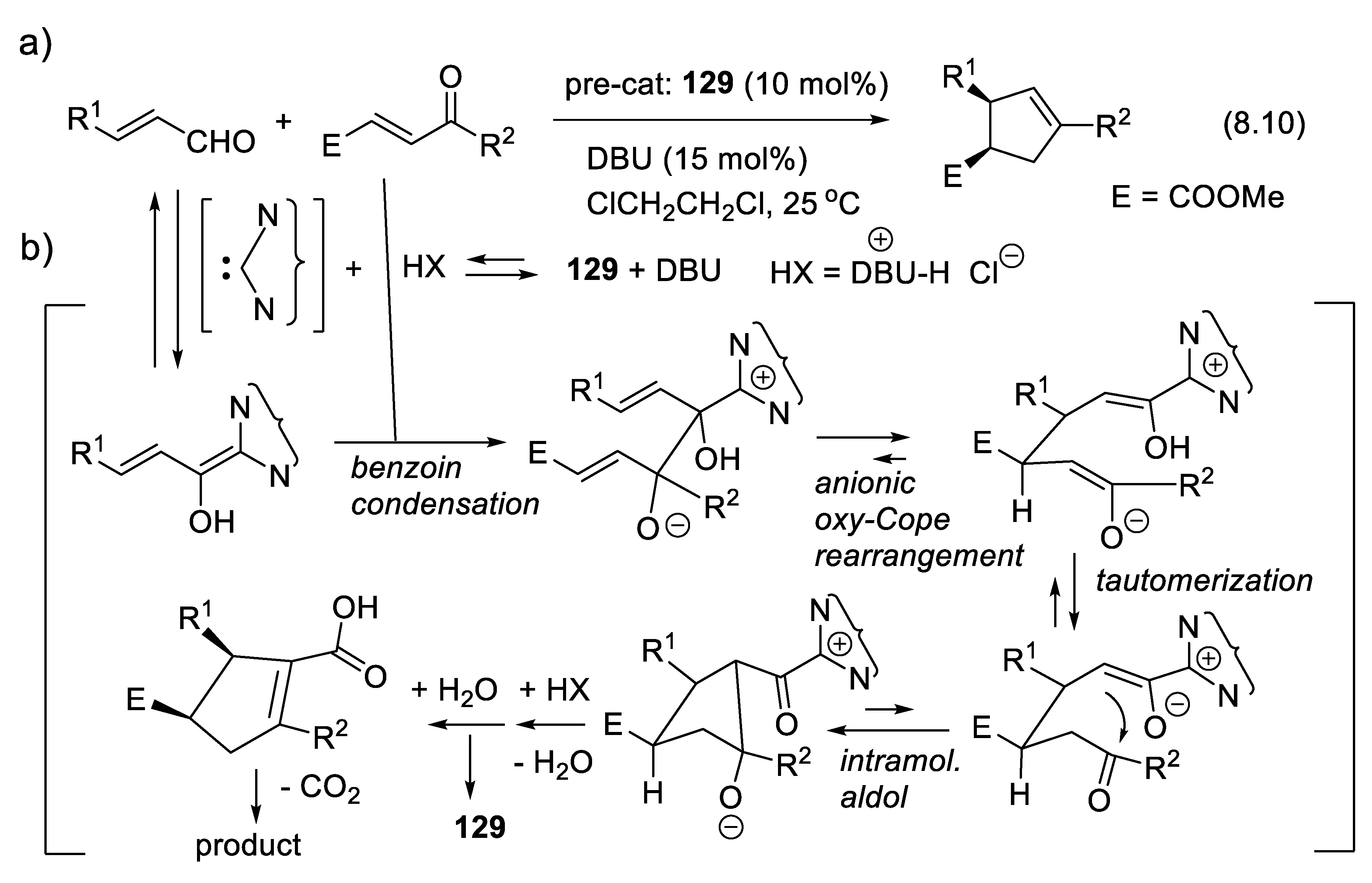

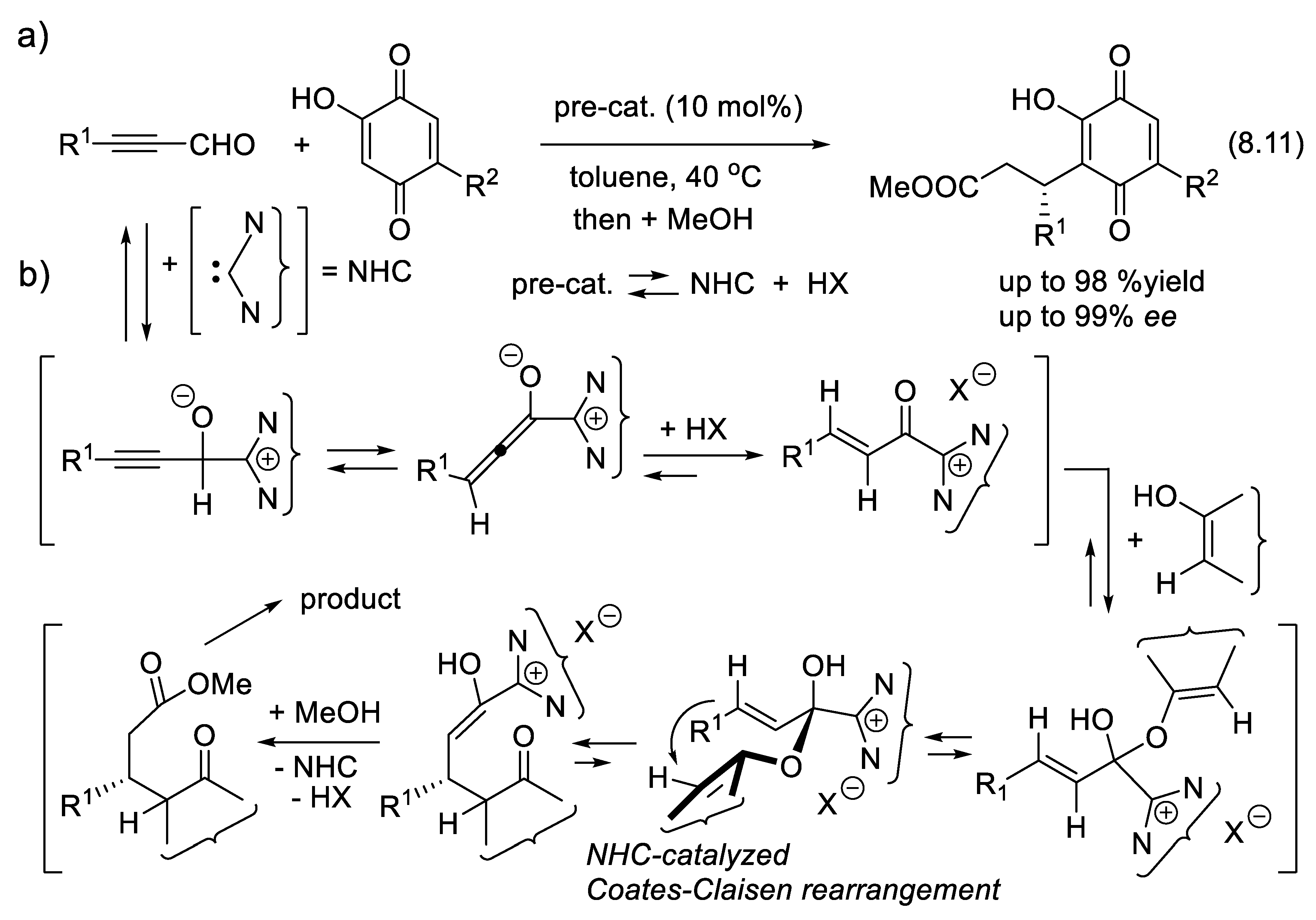

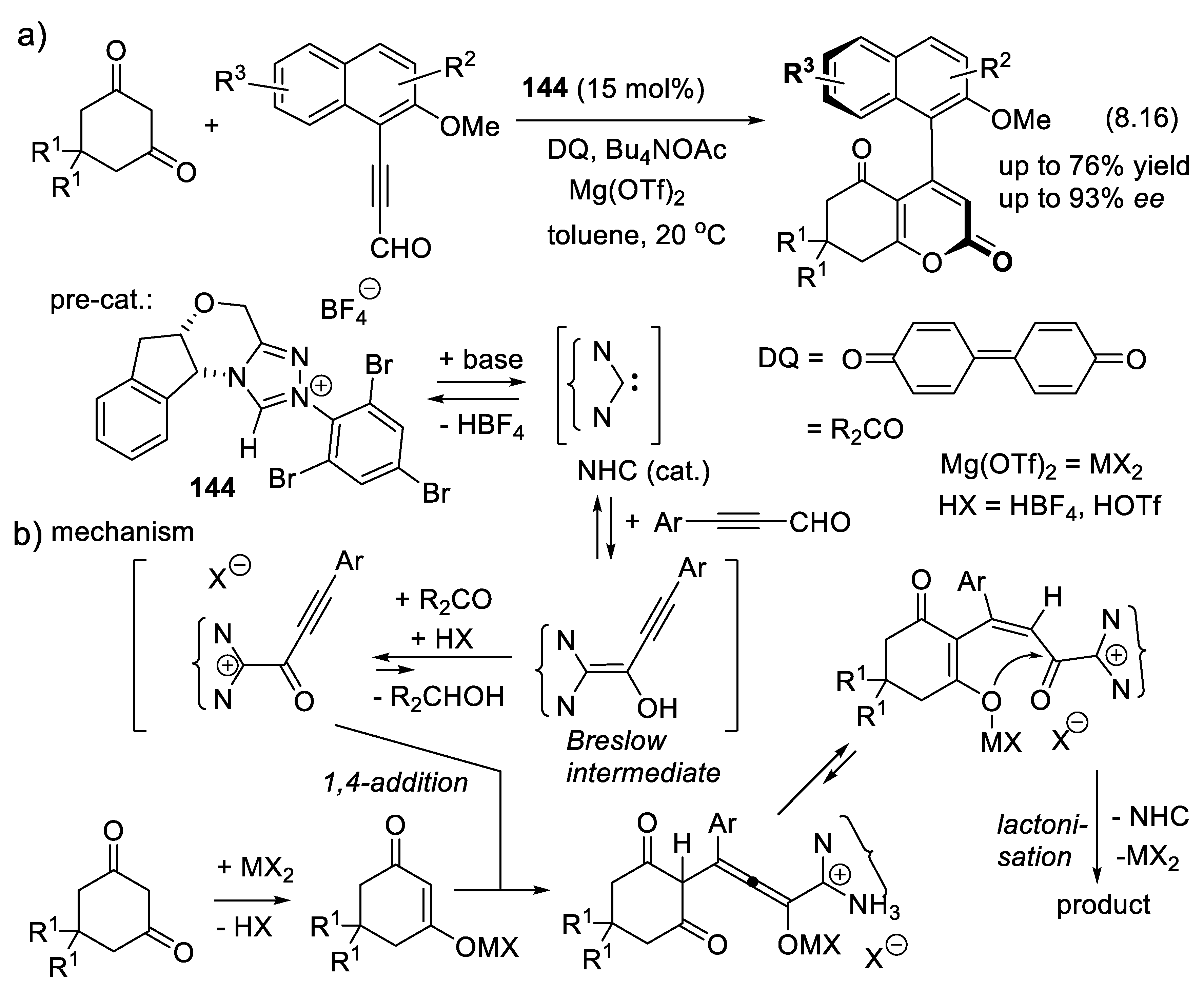

8.5. NHC-Catalyzed Asymmetric Cycloadditions

8.6. NHC Catalyzed Asymmetric (3,3)-Sigmatropic Rearrangements

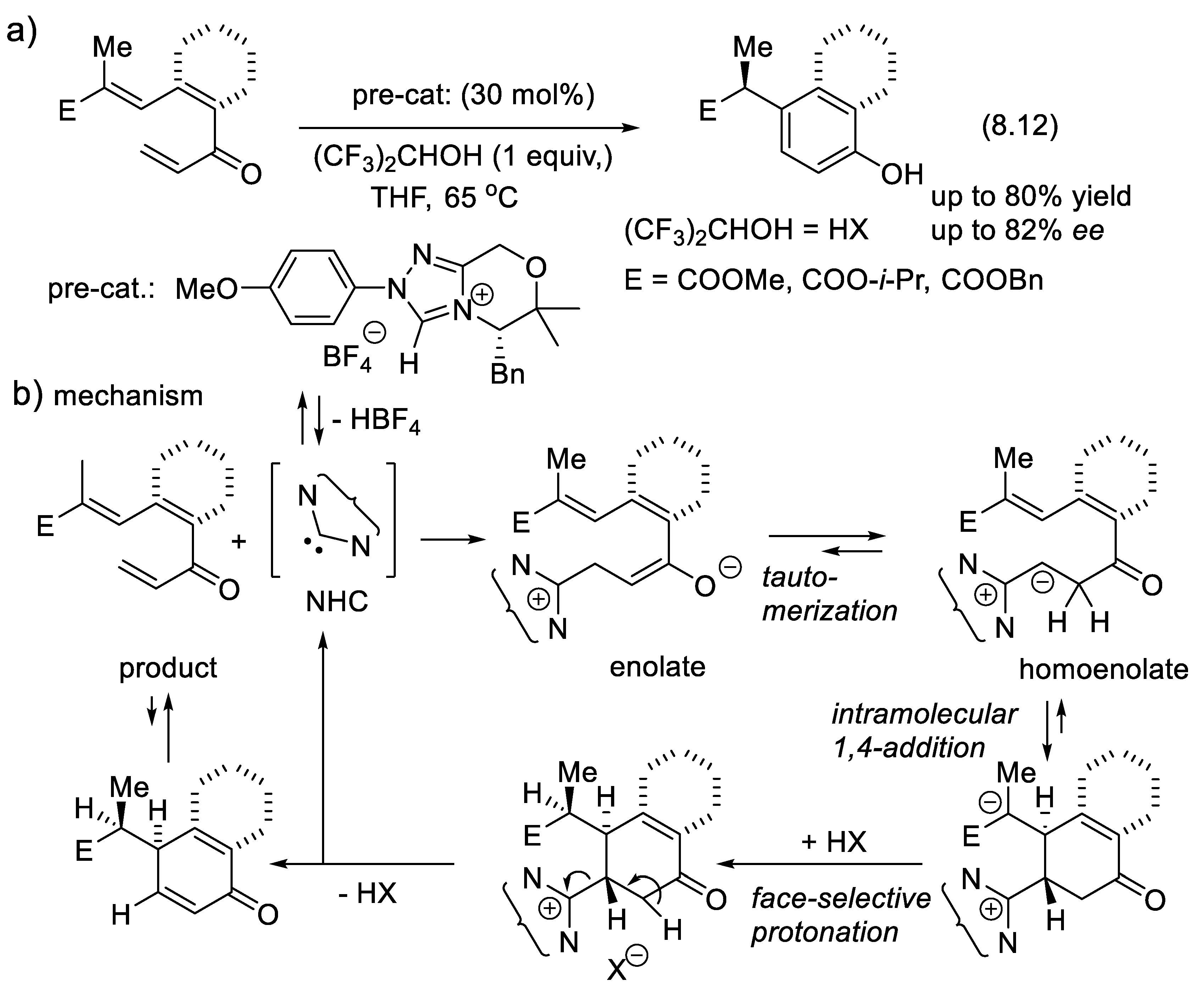

8.7. Umpolung of Michael Acceptors by NHCs: Conversion of Enones into Homoenolates

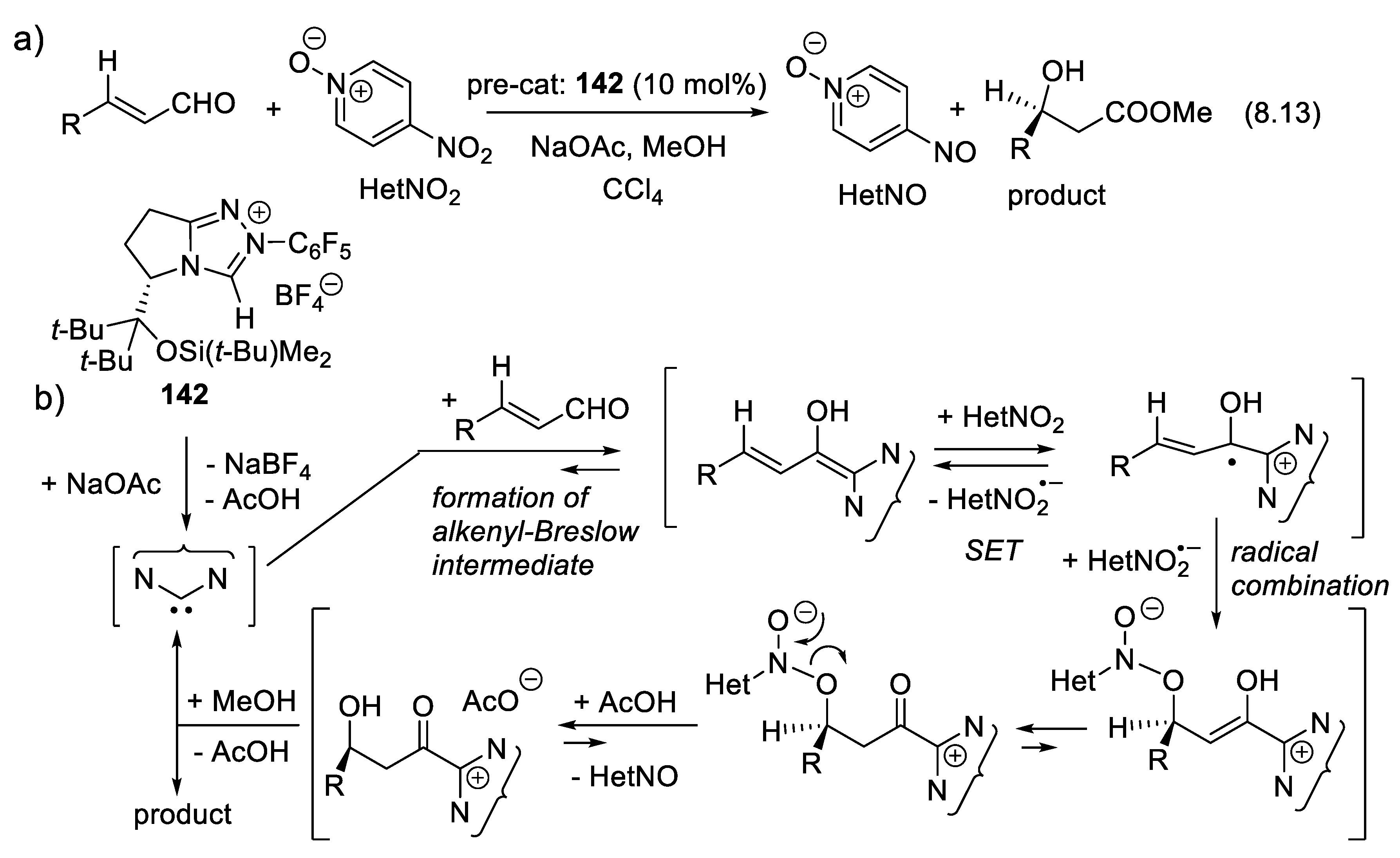

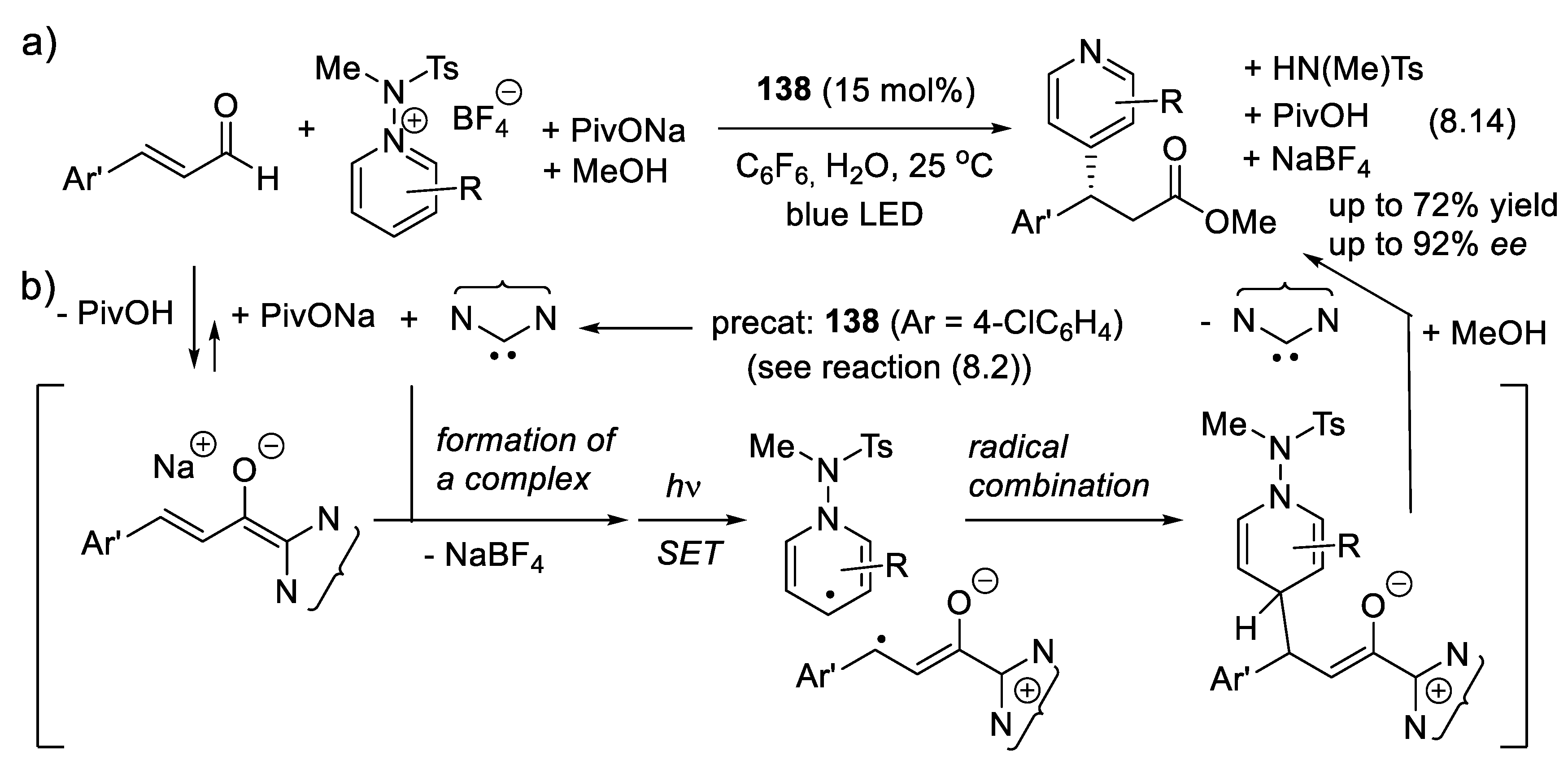

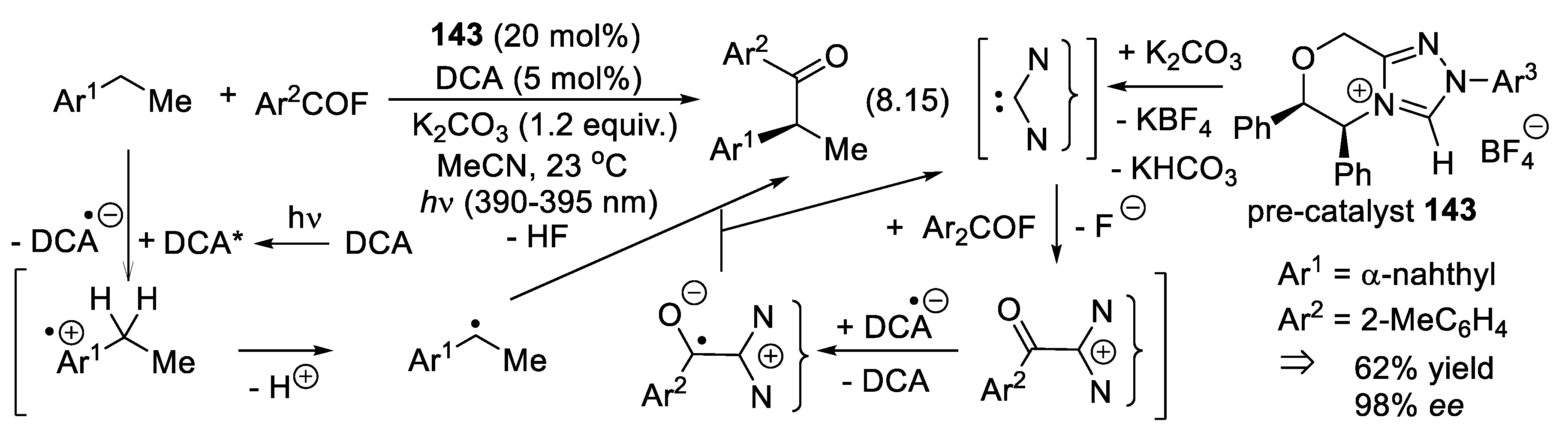

8.8. Radical Reactions Promoted by NHC Catalysts

8.9. NHC-Catalyzed Enantioselective Synthesis of Atropisomers

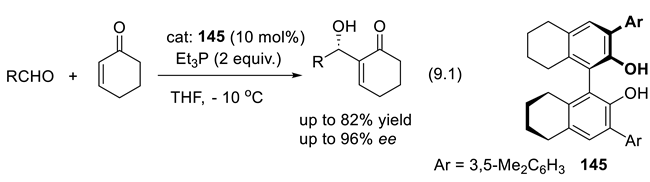

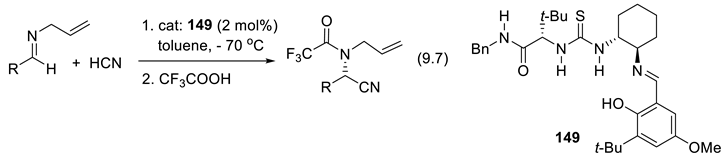

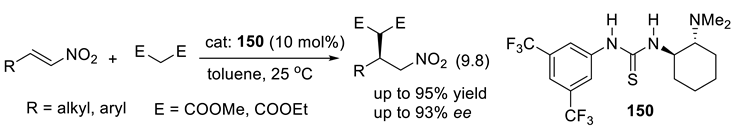

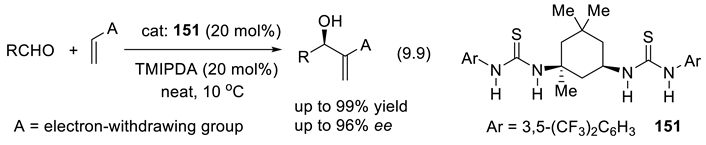

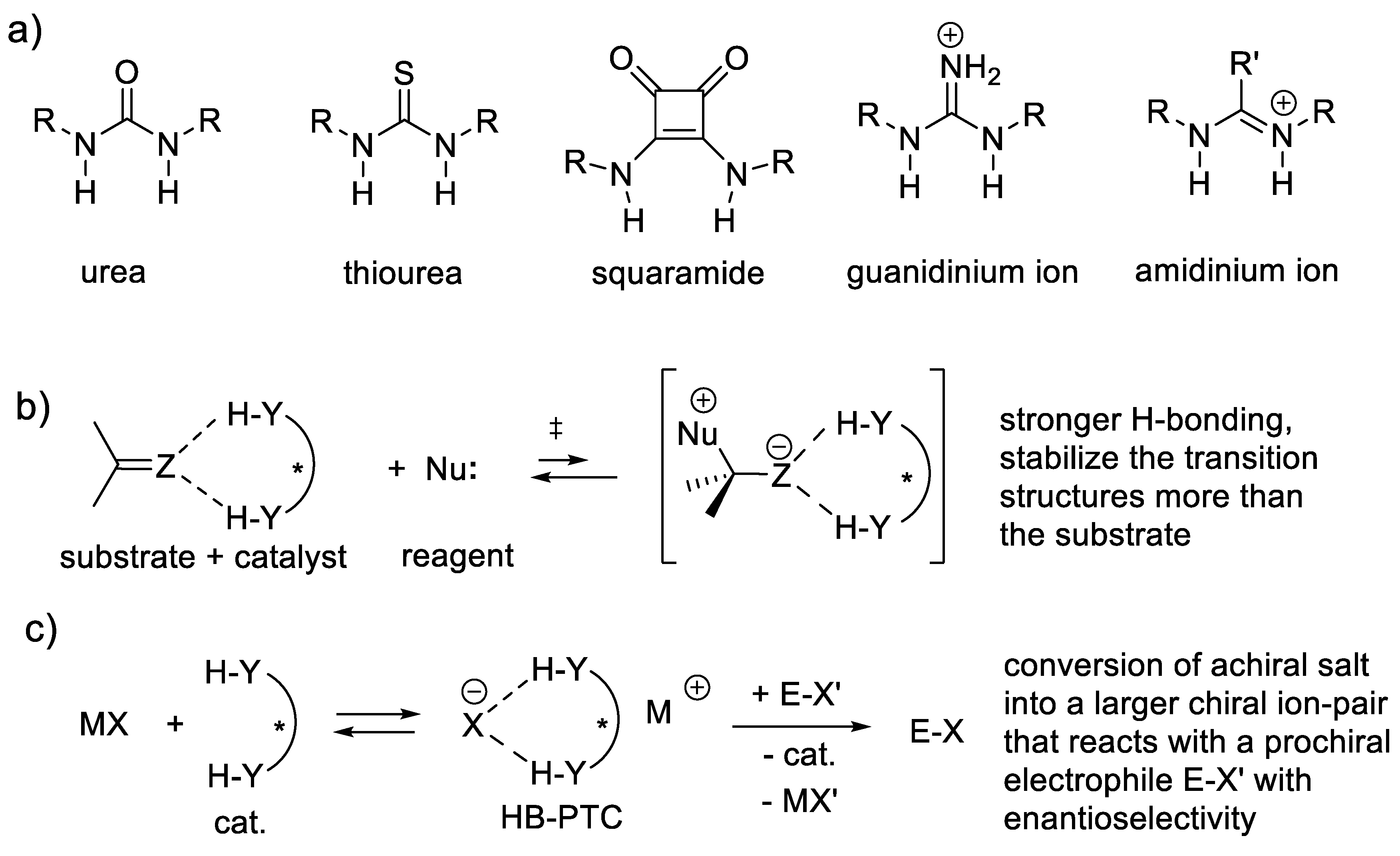

9. Enantioselective Organocatalysis by Hydrogen Bonding

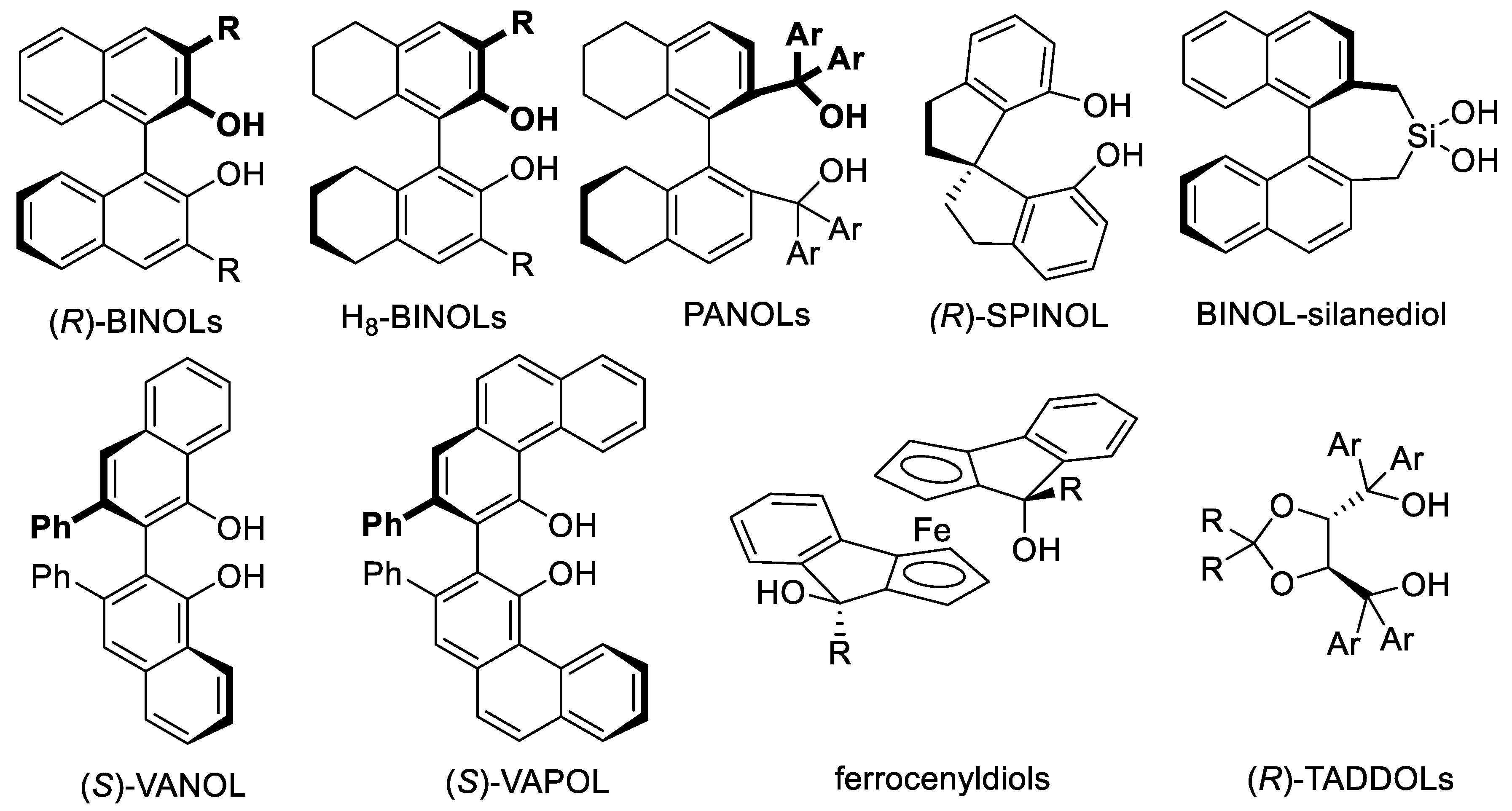

9.1. Applications of Chiral Diols as Organocatalysts

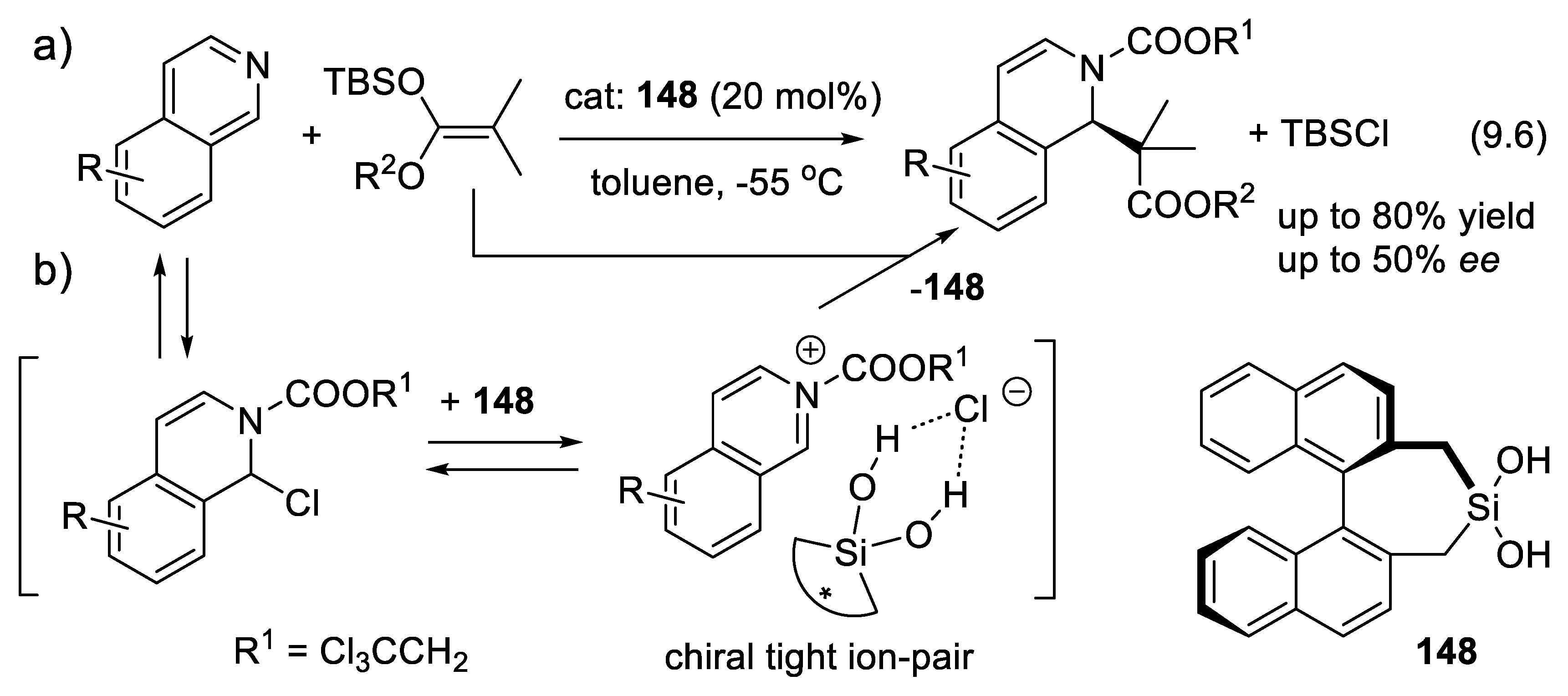

9.2. Silane-1,1-Diols as Chiral Catalysts

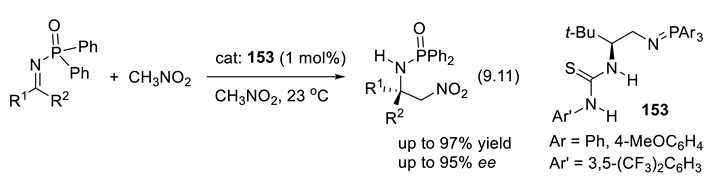

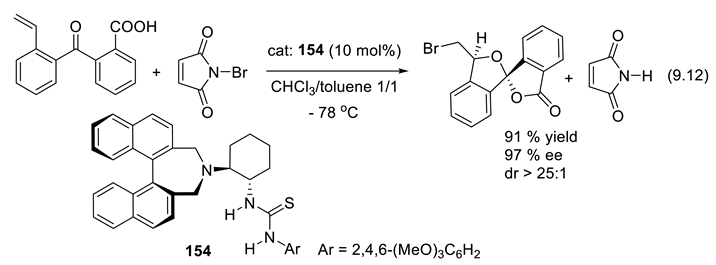

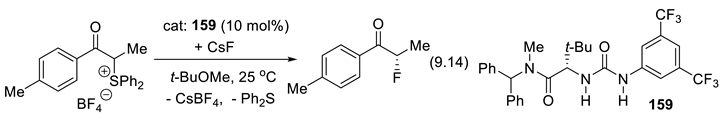

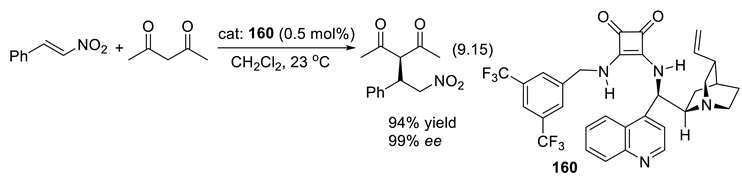

9.3. Applications of Chiral Urea and Thiourea Catalysts

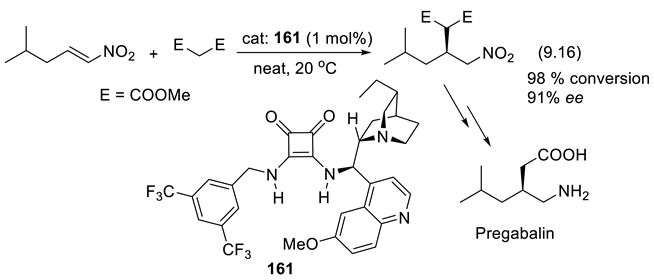

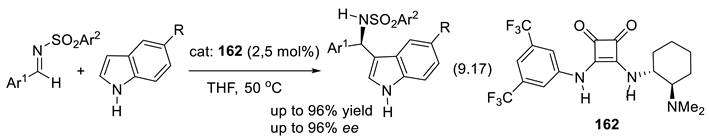

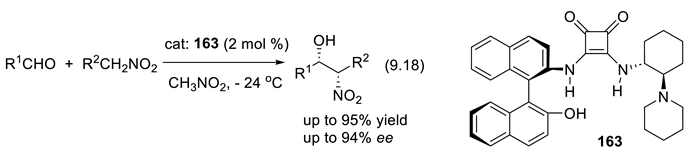

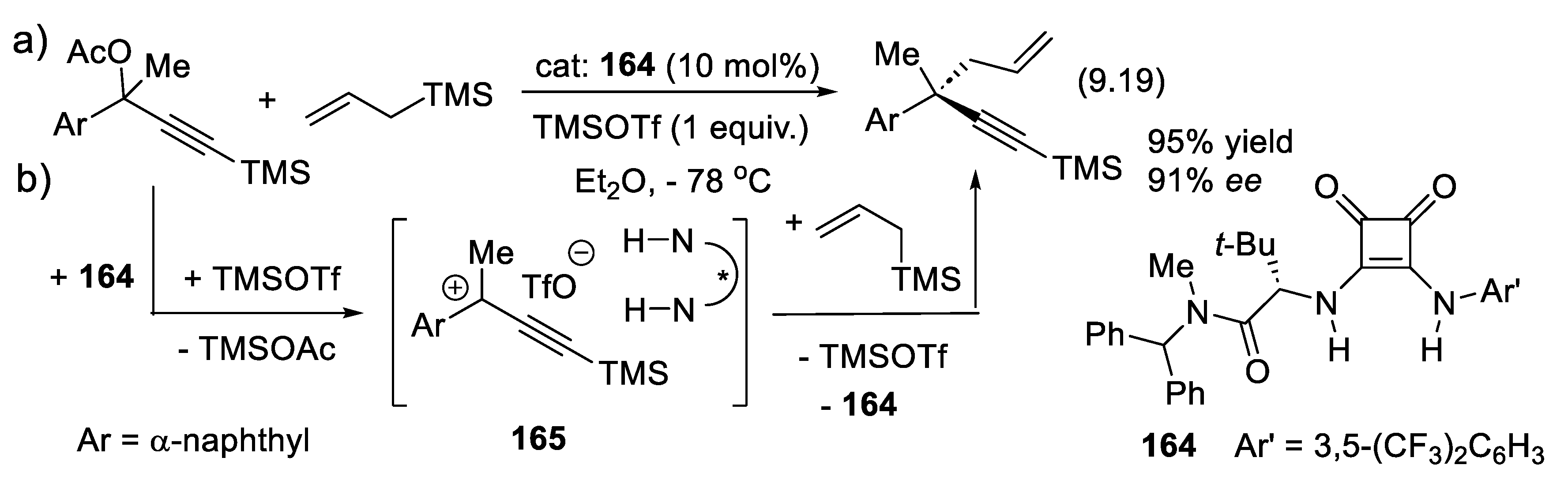

9.4. Applications of Chiral Squaramide-Containing Catalysts

9.5. Amidinium Ions as Chiral Organo-Catalysts

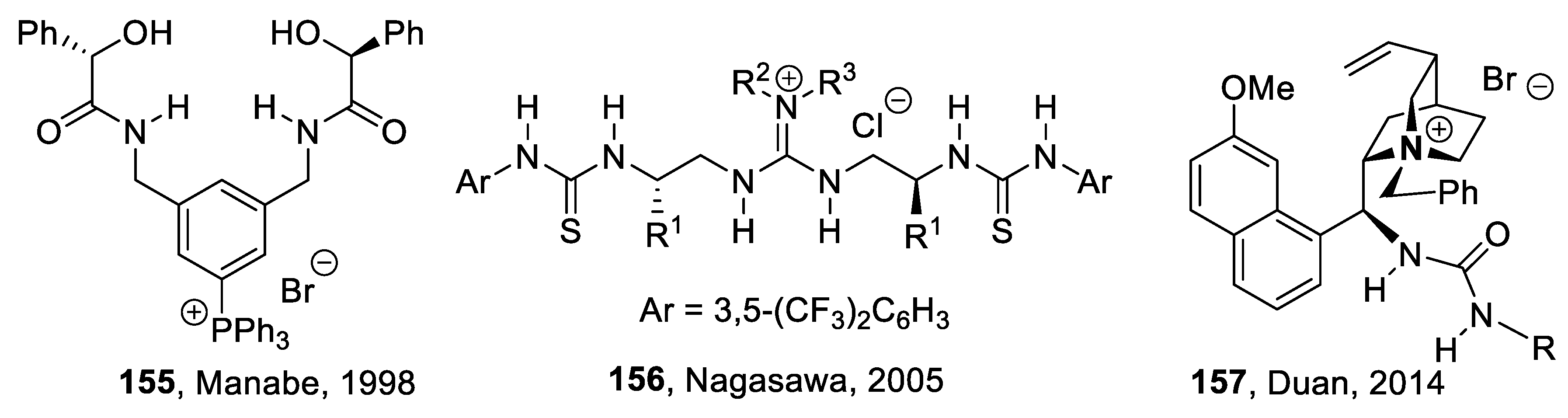

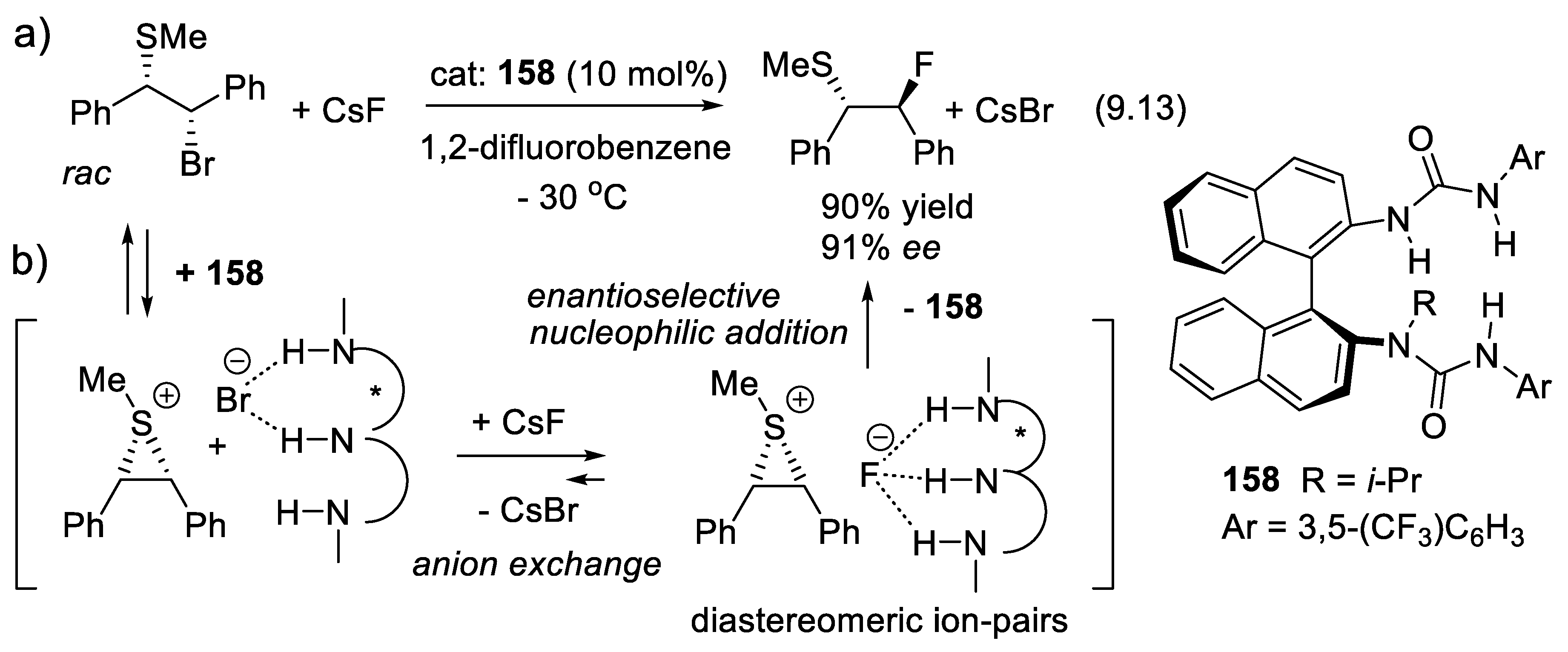

9.6. Other H-Bond Donor Chiral Catalysts

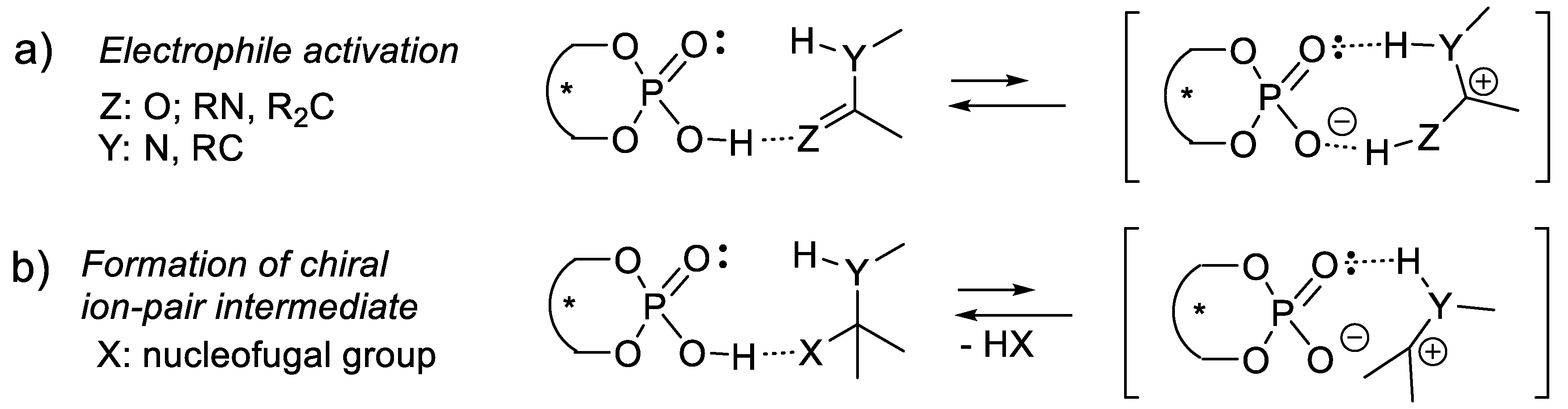

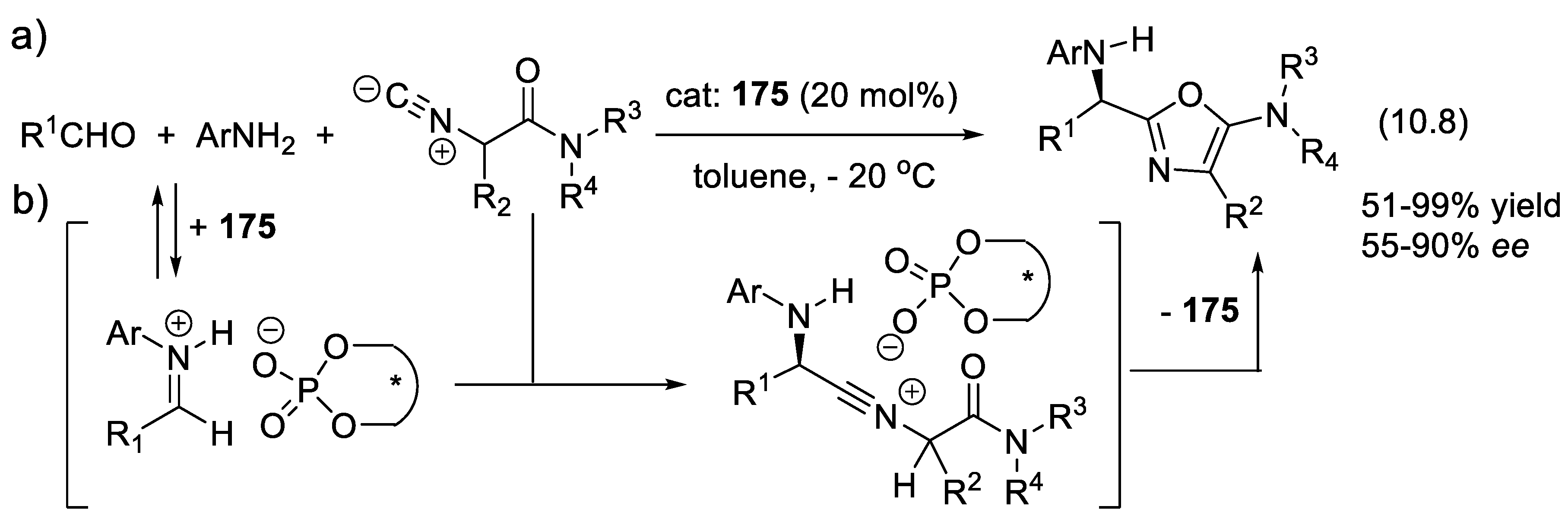

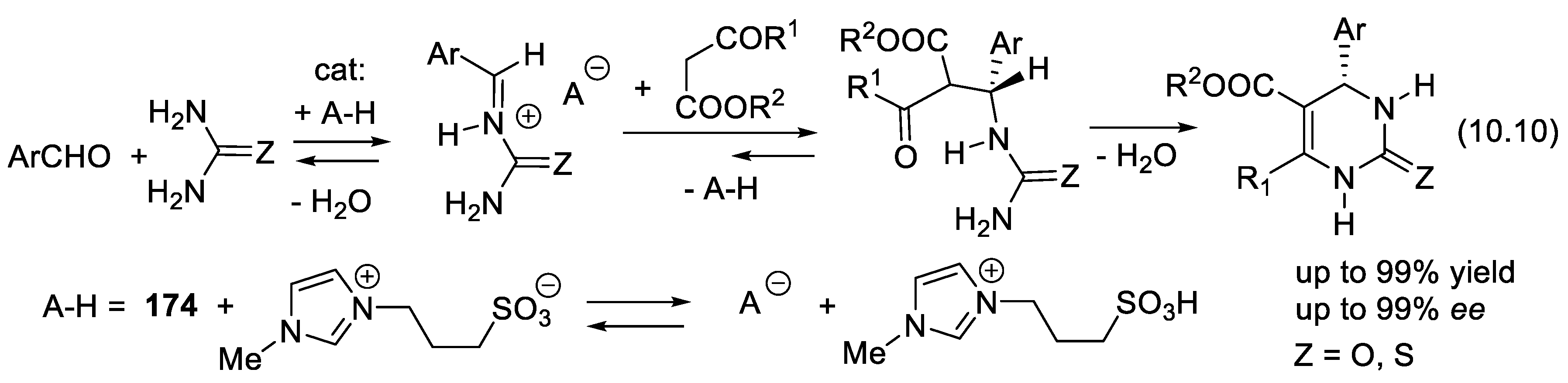

10. Acid Catalysis by Chiral Brønsted Acids

10.1. Chiral Diol Phosphate Catalysts

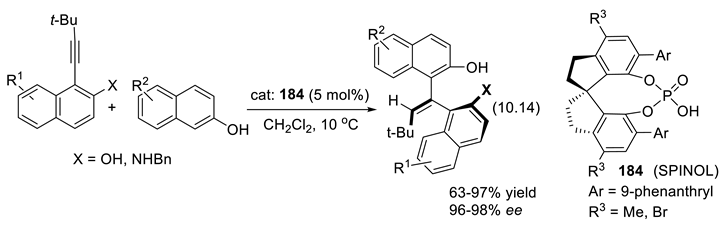

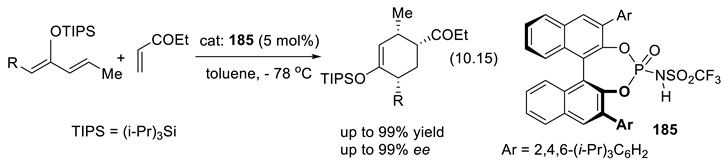

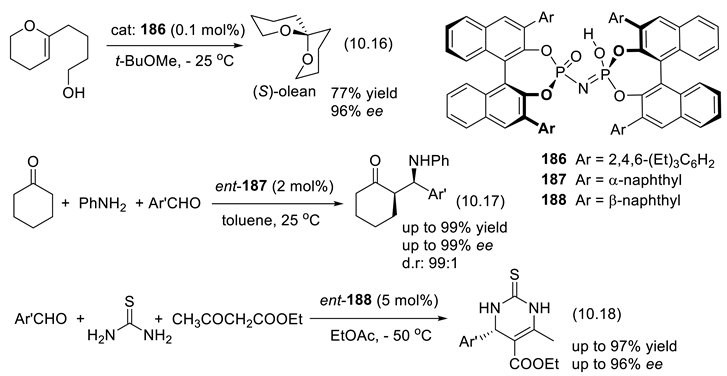

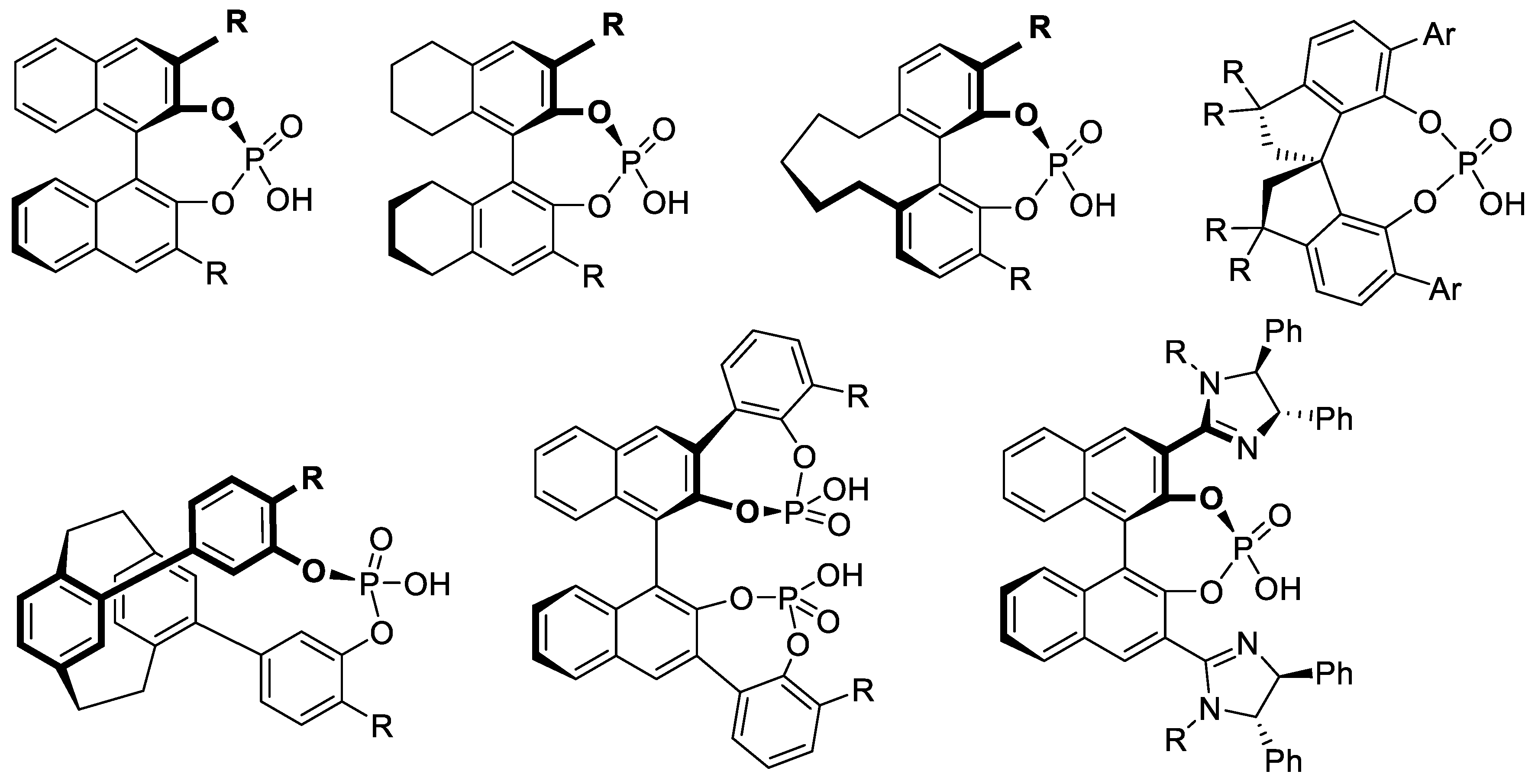

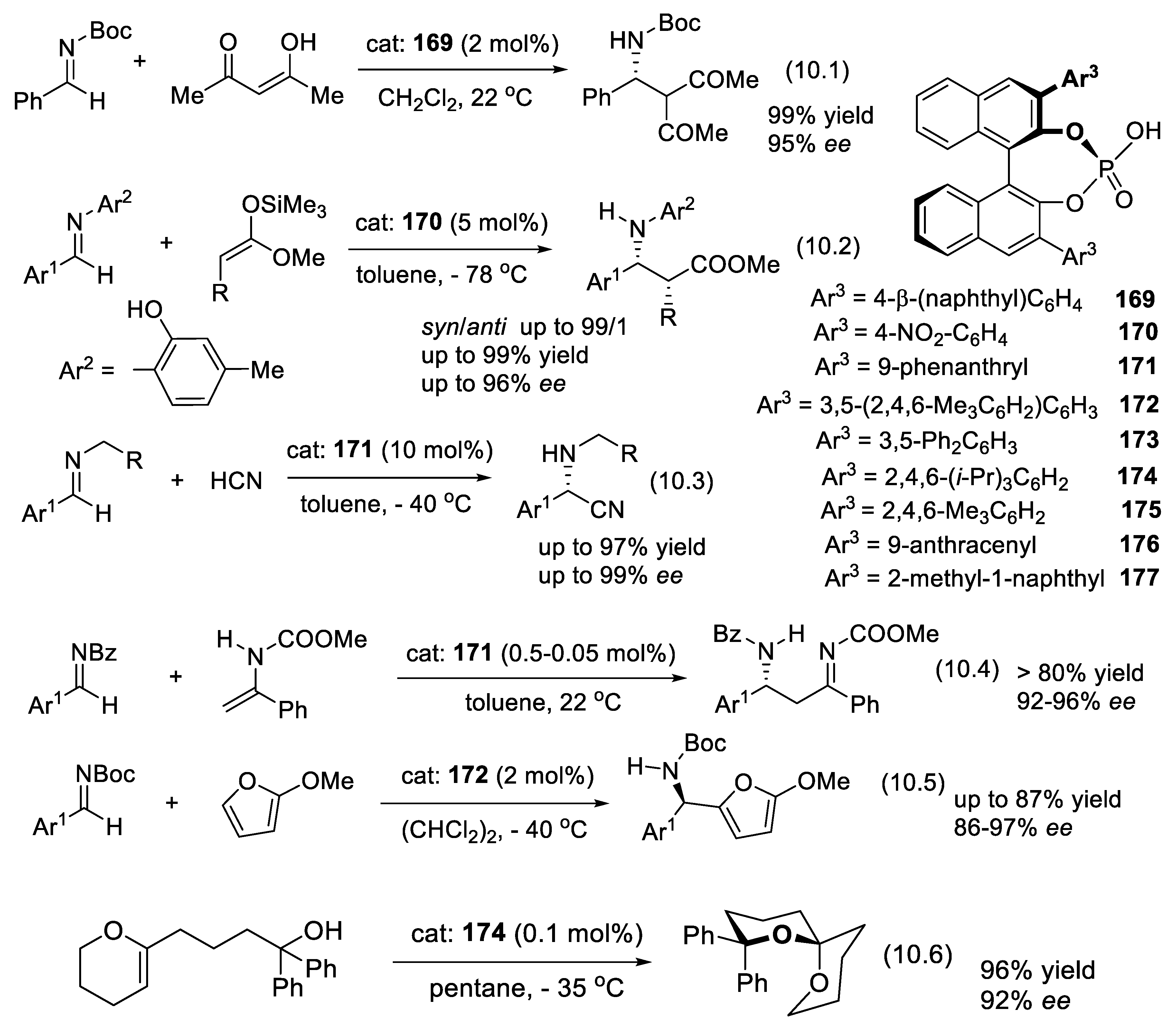

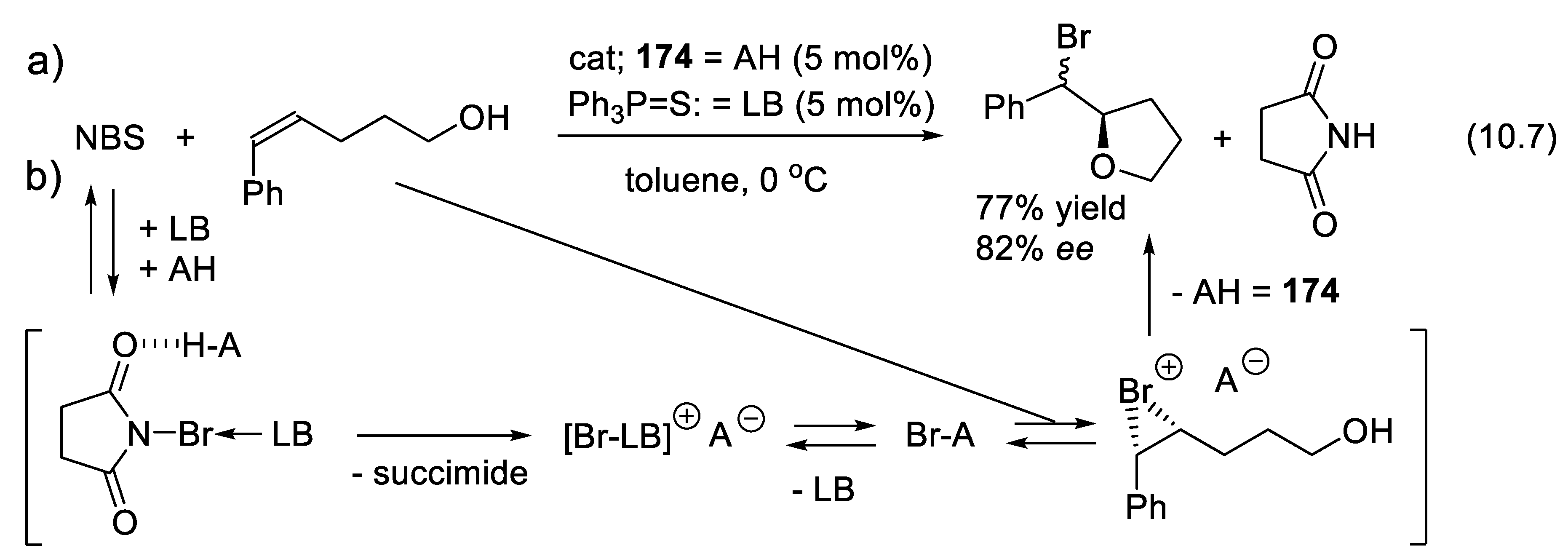

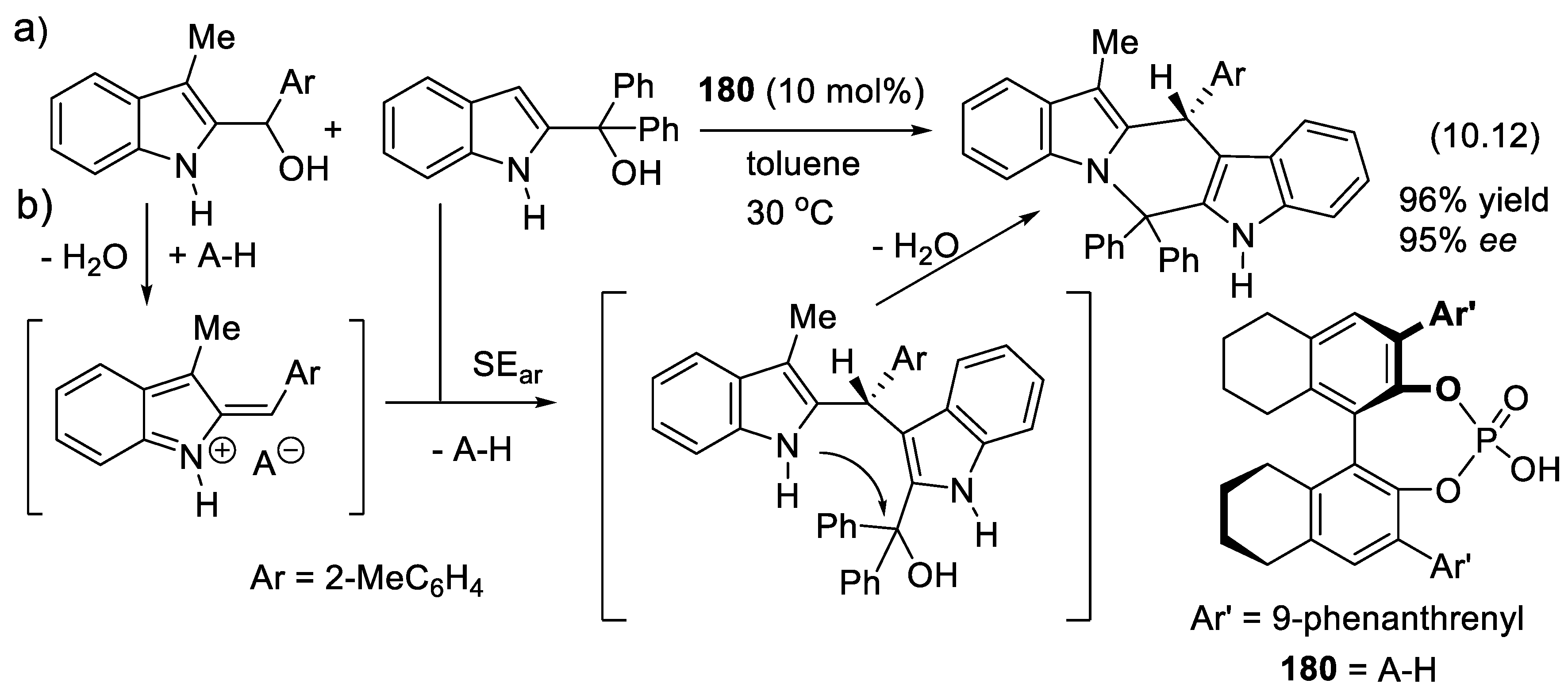

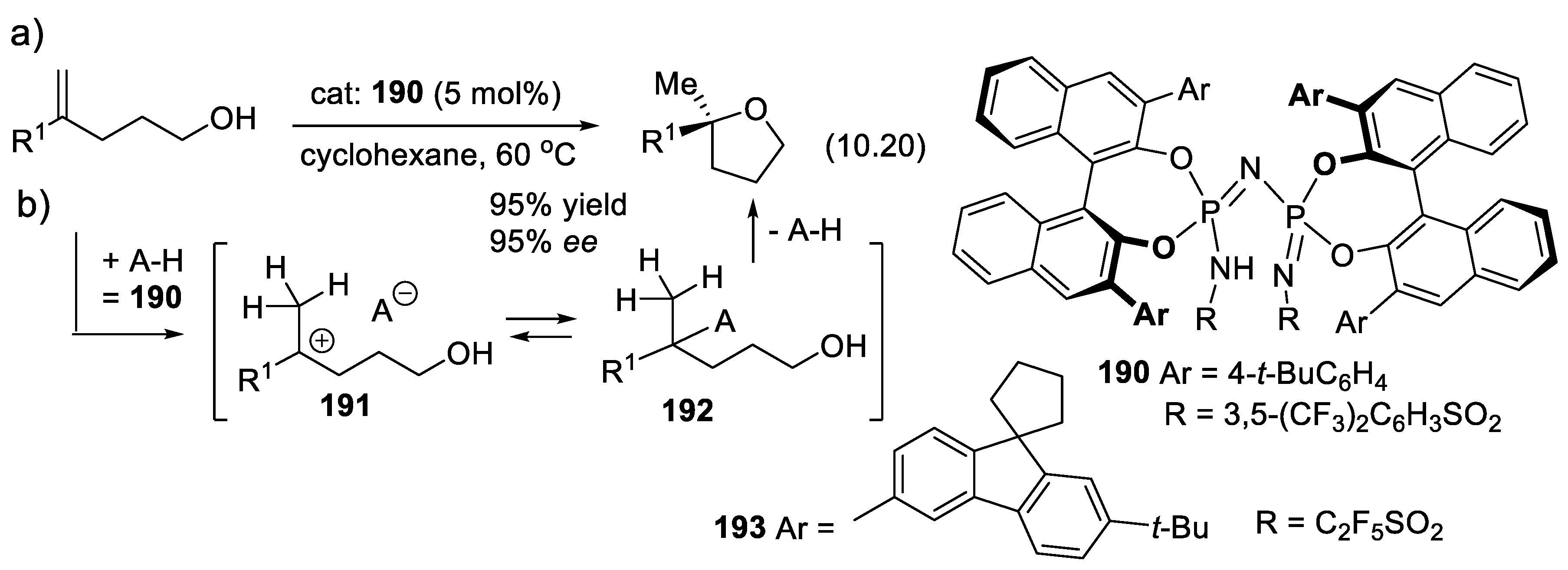

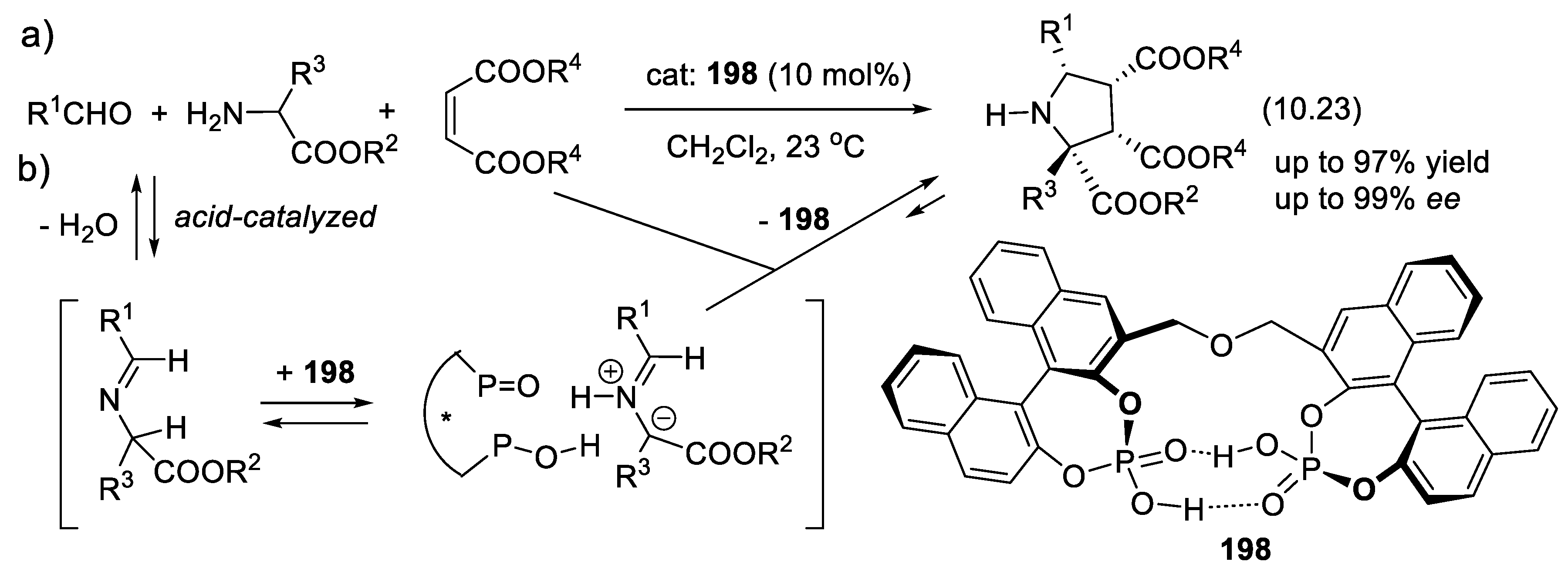

10.1.1. BINOL Phosphates

10.1.2. Other Diol Phosphates

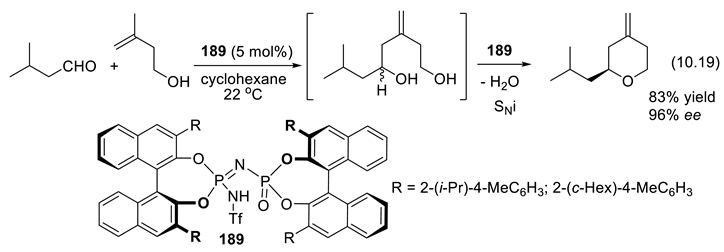

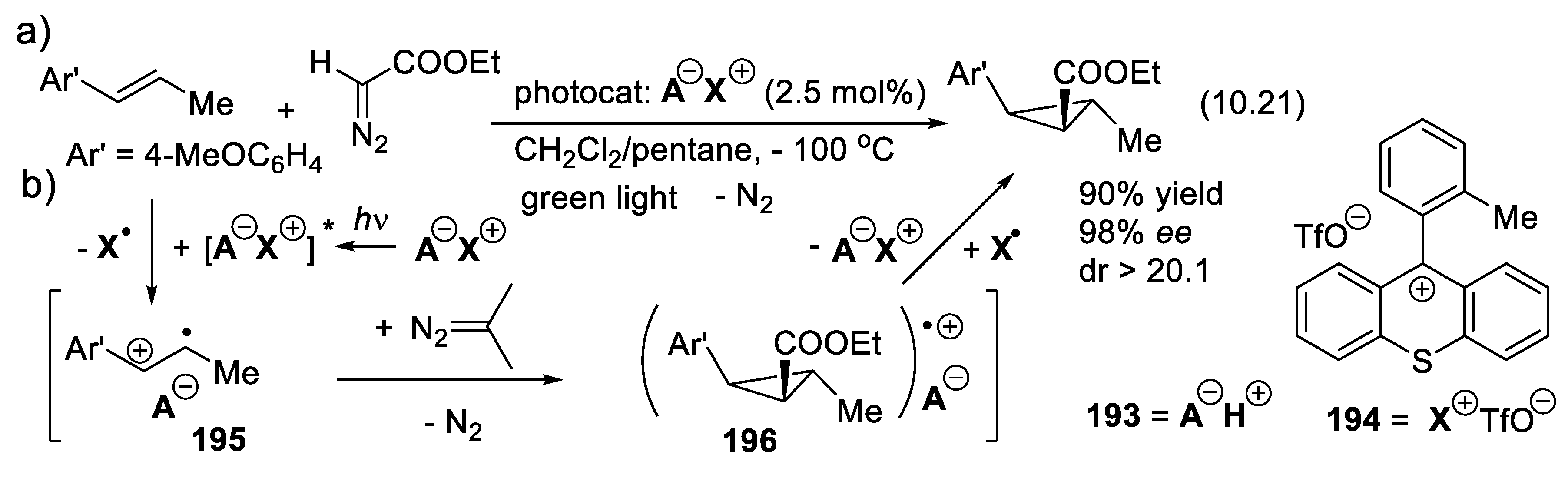

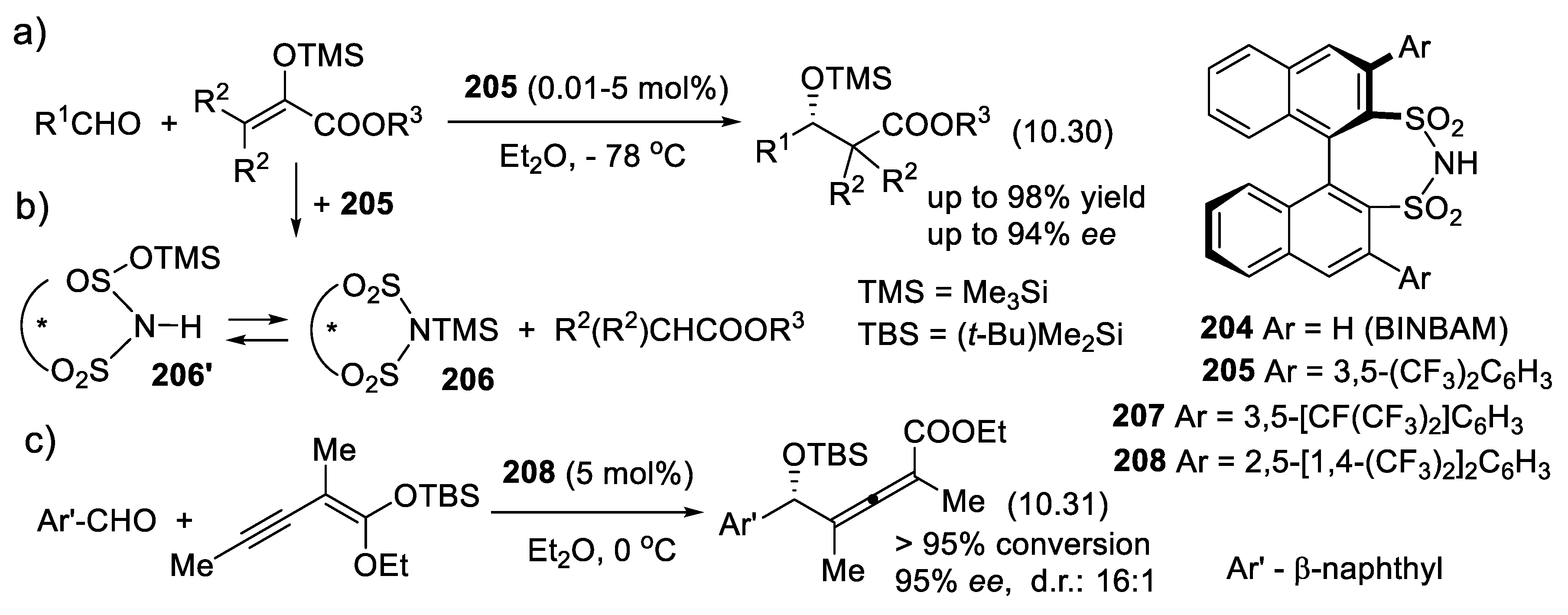

10.2. Stronger Acids Than Diolphosphates

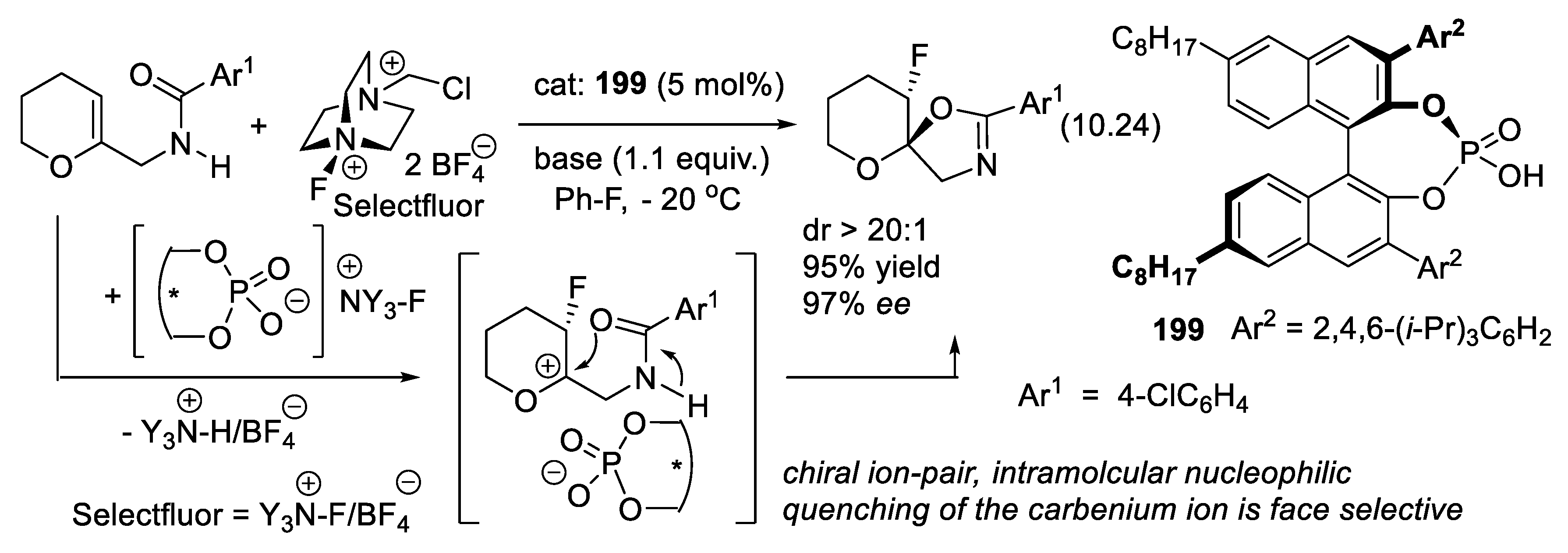

10.3. Diolphosphates as Chiral Anionic Phase Transfer Catalysts for Electrophilic Fluorination

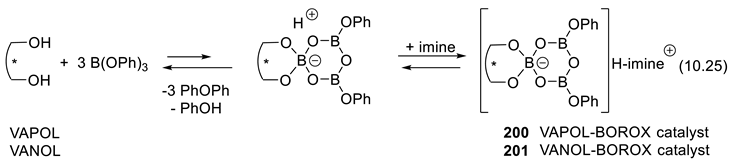

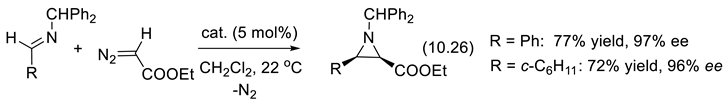

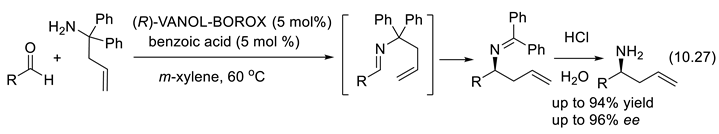

10.4. Chiral Borate and Boroxinate Brønsted Acids

10.5. Chiral Disulfonic Acids and Their Ammonium Salts

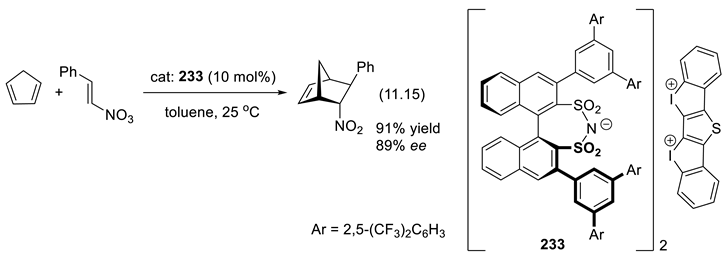

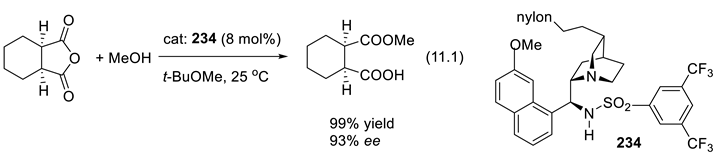

10.6. Chiral Disulfonimides

11. Other Asymmetric Organo-Catalysts

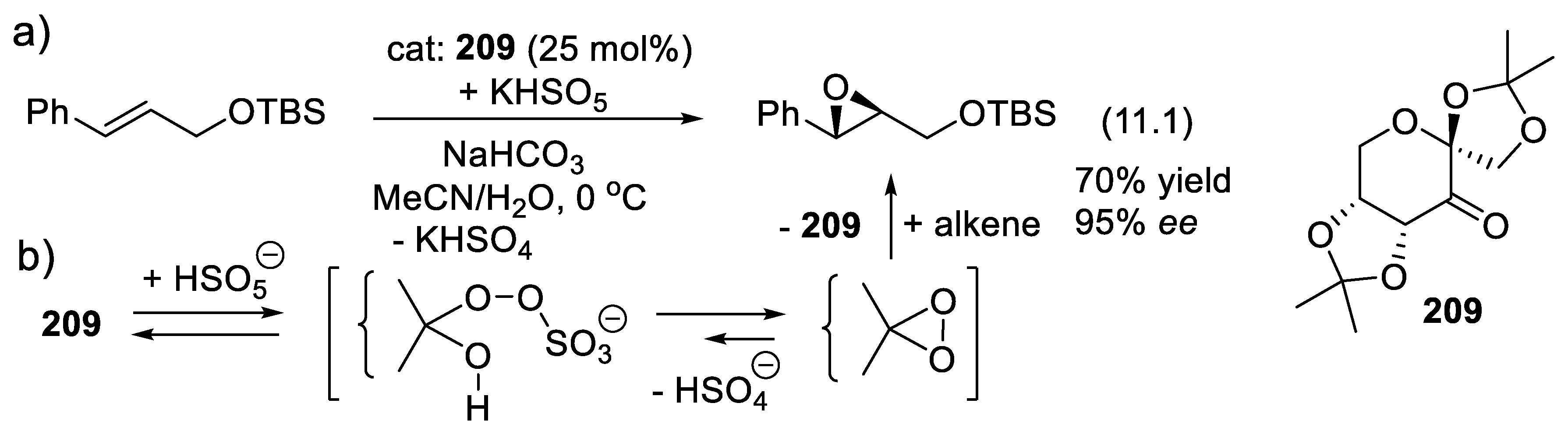

11.1. Asymmetric Alkene Epoxidation Catalyzed by Chiral Ketones

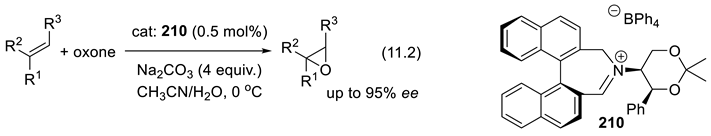

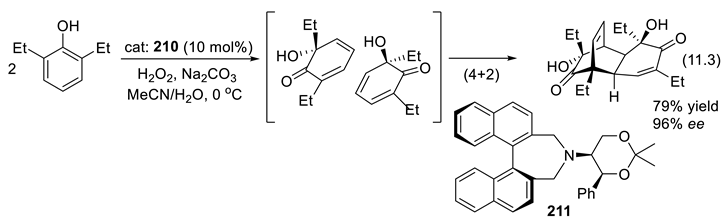

11.2. Asymmetric Alkene Epoxidation Catalyzed by Chiral Iminium Salts

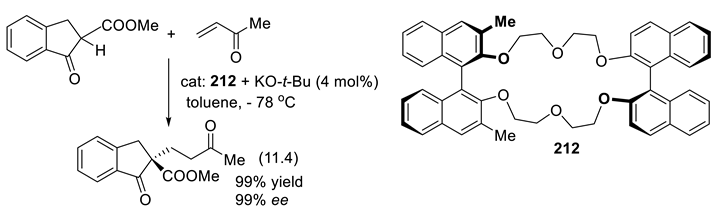

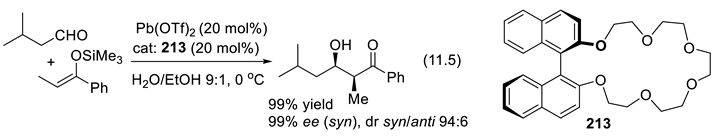

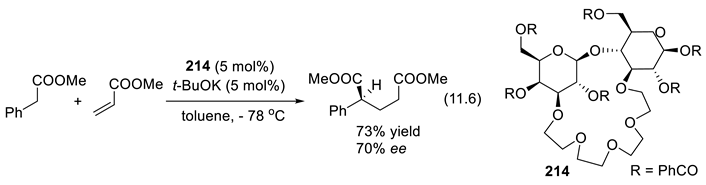

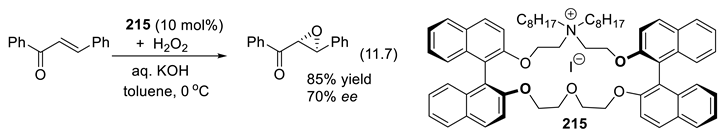

11.3. Crown Ethers

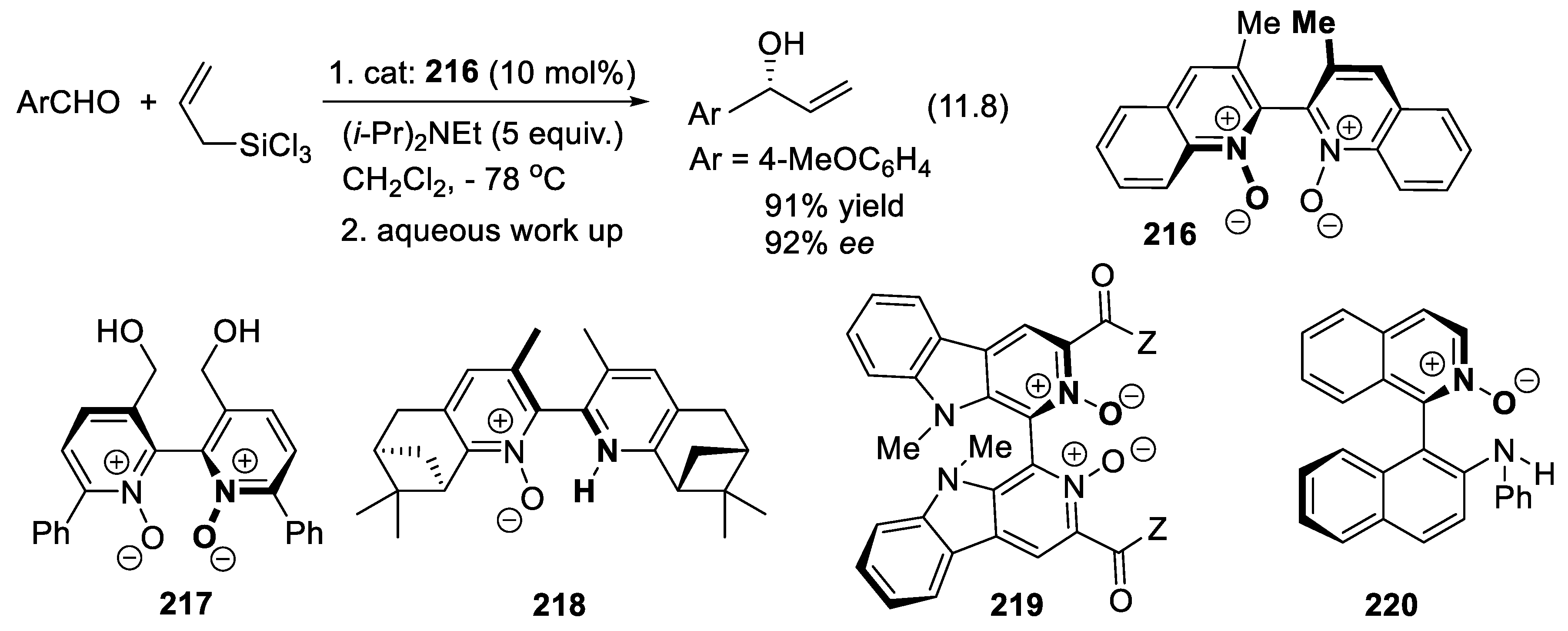

11.4. Chiral N-Amine Oxides

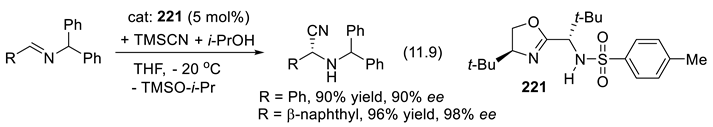

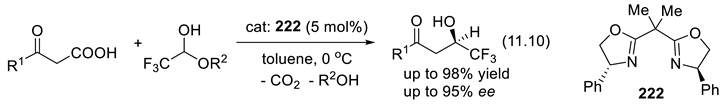

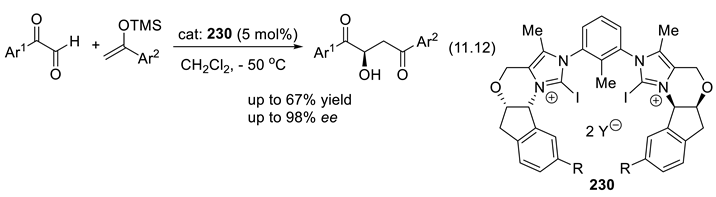

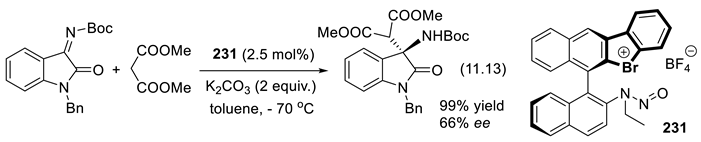

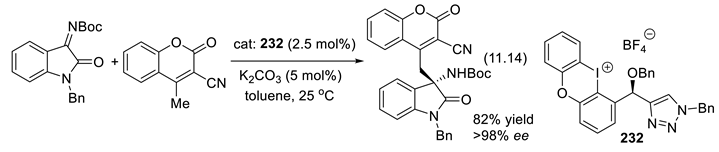

11.5. Chiral Oxazolines and Bisoxazolines

11.6. Chiral Iodine(I) Lewis Acids (XB Donor, σ-Hole Catalysts)

11.7. Chiral Halonium Salts as σ-Hole Catalysts

12. Epilogue

References

- Mila, A.; Ooi, T.; Bach, T. Modern enantioselective catalysis in organic chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 7615–7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemán, J, Cabrera, S. Applications of asymmetric organocatalysis in medicinal chemistry. Chem Soc Rev. 2013, 42, 774–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, S.; Mondal, D. Asymmetric Synthesis in Medicinal Chemistry, Encyclopedia Phys. Org. Chem. First edition; Wang, Z. Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2017, pp. 1-150; ISBN 978—1-118-46858-6.

- Yang, H.; Yu, H-x; Stolarzewicz, I. A.; Tang, W-j. Enantioselective transformations in the synthesis of therapeutic agents. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 9397–9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A. M.; Zanotti-Gerosa, A. Homogenous asymmetric hydrogenation: Recent trends and industrial applications. Curr. Opin. Drug. Discov. Develop. 2010, 13, 698–716. [Google Scholar]

- Bulger, P. G. Industrial applications of organocatalysis. 9, 2012; 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröger, H. Shibasaki catalysts and their use for asymmetric synthetic applications by the chemical industry. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 24, 4116–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylong, D.; Hansoul, P. J. C.; Palkovits, R.; Eisenacker, M. Synthesis of (-)-menthol: industrial synthesis routes and recent development. Flavour Fragrance J. 2022, 37, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Snajdrova, R.; Moore, J. C.; Baldenius, K.; Bornscheuer, U. T. Biocatalysis: Enzymatic synthesis for industrial applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 88–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aukland, Miles, H. ; List, B. Organocatalysis emerging as a technology. Pure Appl. Chem. 2021, 93, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D. L. Highlights of the recent patent literature: Focus on asymmetric organocatalysis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022, 26, 2224–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. K. The importance of organocatalysis (asymmetric and non-asymmetric) in agrochemicals. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202300204, pp. 1-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmchen, G. Definition of the term asymmetric synthesis—History and revision. Chirality 2024, 35, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapatra, S. K. , Talapatra, B. Asymmetric Synthesis. In Basic Concepts in Organic Stereochemistry. Springer Nature, Cham, CH, 2022, pp. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.; Slimmer, M. Versuche über asymmetrische Synthese. Ber. dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1903, 36, 2575–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwald, W. Ueber asymmetrische Synthese. Ber. dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1904, 37, 1368–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, A. Studies in asymmetric synthesis. I/II J Chem Soc. 1904, 85, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bada, J. L. Origins of homochirality. Nature 1995, 374, 594–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinert, C.; Filippi, J-J. ; Nahon, L.; Hoffmann, S. V.; d’Hendecourt, L.; de Marcellus, P.; Bredehöft, J. H.; Thiemann, W. H-P.; Meierhenrich, U. J. Photochirogenesis: photochemical models on the origin of biomolecular homochirality. Symmetry 2010, 2, 1055–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmond, D. G. The origin of biological homochirality. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, article nb. 032540, pp. 1-12; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolnick, J.; Gao, M. On the emergence of homochirality and life itself. Biochem. 2021, 43, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, J. The discovery of stereoselectivity at biological receptors: Arnaldo Piutti and the taste of the asparagine enantiomers-History and analysis on the 125th anniversary. Chirality 2012, 24, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandula, J. S.; Rayala, V. V. S. P. K.; Pullapanthula, R. Chirality: An inescapable concept for the pharmaceutical, bio-pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries. Sep. Sci. plus 2023, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, W. H.; Guida, W. C.; Daniel, K. G. The significance of chirality in drug design and development. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkadi, H.; Jbeily, R. Role of chirality in drugs: An overview. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2018, 18, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceramella, J.; Iacopetta, D.; Franchini, A.; De Luca, M.; Saturnino, C.; Andreu, I.; Sinicropi, M. S.; Catalano, A. A look at the importance of chirality in drug activity: Some significative examples. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, article–nb.10909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S-j. ; Zhu, Y-y.; Luo, C-y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, F-y.; Li, R-x.; Lin, G-q.; Zhang, J-g. Chiral drugs: Sources, absolute configuration identification, pharmacological applications, and future research trends. LabMed Discovery 2024, 1, article nb. 100008, pp. 1-9; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVicker, R. U.; O’Boyle, N. M. Chirality of new drug approvals (2013–2022): Trends and perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67(4), 2305–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S. K.; Colburn, W. A.; Tracewell, W. G.; Kook, K. A.; Stirling, D. I.; Jaworsky, M. S.; Scheffler, M. A.; Thomas, S. D.; Laskin, O. L. Clinical pharmacokinetics of thalidomide. Clin. Pharmacokinetics 2004, 43, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitchagno, G. T. M.; Nchiozem-Ngnitedem, V. A.; Melchert, D; Fobotou, S. A. Demystifying racemic natural products in the homochiral world. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasteur, L. Mémoire sur la fermentation de l'acide tartrique. Compt. rend. hebd. séa. Acad. Sci. 1858, 46(13), 615-618; see also: Gal, J. The discovery of biological enantioselectivity: Louis Pasteur and the fermentation of tartaric acid, 1857--A review and analysis 150 yr later. Chirality 2008, 20(1), 5-19; [CrossRef]

- Contesini, F. J.; Lopes, D. B.; Macedo, G. A.; Nascimento, M. d. G.; Carvalho, P. d. O. Aspergillus sp lipase: Potential biocatalyst for industrial use. J. Mol. Catal. B-Enzymatic. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R. N. Biocatalysis: Synthesis of key intermediates for development of pharmaceuticals. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 1056–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriata-Adamusiak, R.; Strub, D.; Lochynski, S. Application of microorganisms towards synthesis of chiral terpenoid derivatives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechn. 2012, 95, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, D.; Green, A. P.; Pontini, M.; Willies, S. C.; Rowles, I.; Frank, A.; Grogan, G.; Turner, N. J. Engineering an enantioselective amine oxidase for the synthesis of pharmaceutical building blocks and alkaloid natural products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10863–10869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reetz, M. T. Biocatalysis in organic chemistry and biotechnology: past, present, and future. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12480–12496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, M.; Farnberger, J. E.; Kroutil, W. The industrial age of biocatalytic transamination. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 32, 6965–6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, R.; Hayashi, T.; Buller, R. M. Directed evolution of carbon-hydrogen bond activating enzymes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 60, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E. Einfluss der Configuration auf die Wirkung der Enzyme. Ber. dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1894, 27, 2985–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- a) Chapman, J.; Ismail, A. E.; Zoica Dinu, C. Industrial applications of enzymes: Recent advances, techniques, and outlooks. Catalysts 2018, 8(6), article nb. 238, pp. 1-26; https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8060238; b) Wu, S.; Snajdrova, R.; Moore, J. C.; Baldenius, K.; Bornscheuer, U. T. Biocatalysis: enzymatic synthesis for industrial applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 60(1), 88-119. [CrossRef]

- IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 3rd ed. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry; 2006. Online version 3.0.1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Micha, D. A. Molecular interactions: concepts and methods. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York, USA, 2020, pp. 9: 1-385; Print ISBN: 9780470290743; Online ISBN, 9780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, V. Théorie générale de l'action de quelques diastases, Compt. rend. hebd. séa. Acad. Sci. 1902, 135, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, L.; Menten, M. L. Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung, Biochemische Zeitschrift 1913, 49, 333-369. 49.

- Michaelis, L.; Menten, M. L.; Johnson, K. A.; Goody, R. S. The original Michaelis constant: translation of the 1913 Michaelis-Menten paper. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 8264–8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchot, C.; Samuel, O.; Dunach, E.; Zhao, S.; Agami, C.; Kagan, H. B. Nonlinear effects in asymmetric synthesis. Examples in asymmetric oxidations and aldolization reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 2353–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaneux, D. , Zhao, S.-H., Samuel, O., Rainford, D.; Kagan, H. B. Nonlinear effects in asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 9430–9439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soai, K. , Shibata, T., Morioka, H.; Choji, K. Asymmetric autocatalysis and amplification of enantiomeric excess of a chiral molecule. Nature 1995, 378, 767–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmond, D. G. ; Kinetic aspects of nonlinear effects in asymmetric catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athavale, S.; Simon, A.; Houk, K. N.; Denmark, S. E. Demystifying the asymmetry-amplifying, autocatalytic behaviour of the Soai reaction through structural, mechanistic and computational studies. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thierry, T.; Geiger, Y.; Bellemin-Laponnaz, S. Observation of hyperpositive non-linear effect in asymmetric organozinc alkylation in presence of N-pyrrolidinyl norephedrine. Molecules 2022, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Suh, S-E. ; Kang, H. Advances in exploring mechanisms of oxidative phenolic coupling reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 4347–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassermann, A. Homogeneous catalysis of diene syntheses. A new type of third-order reaction. J. Chem. Soc, 1942; 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, P.; Houk, K. N. Organic Chemistry, Theory, Reactivity and Mechanisms in Modern Synthesis, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany, 2019, Chap. 5.3.9-11, pp. 387-396, Chap. 7.6.6-7, pp. 849-853; ISBN 978-3-527-34532-8.

- Gröger, H.; Asano, Y. Introduction – Principles and historical landmarks of enzyme catalysis in organic synthesis. In “Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis”. Drauz K.; Gröger, H.; May, O. Eds., Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany, Print: ISBN: 9783527325474; Online ISBN: 978352763 9861, 2012, Chap. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeller, K. , Wong, C-H. Enzymes for chemical synthesis. Nature 2001, 409, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Hanfeld, H. Enzyme catalysis in organic synthesis. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai, T.; Higashibayashi, S.; Hanaya, K. Recent examples of the use of biocatalysts with high accessibility and availability in natural product synthesis. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 3469–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanfeld, U.; Hollmann, F.; Paul, C. E. Biocatalysis making waves in organic chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 594–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. Recent advances in enzymatic carbon-carbon bond formation. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 25932–25974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- a) O’Connell, A.; Barry, A.; Burke, A. J.; Hutton, A: E.; Bell, E. L.; Green, A: P.; O’Reilly, E. Biocatalysis: landmark discoveries and applications in chemical synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 53(6), 2828-2850; https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cs00689a; b)Wu, S-k.; Snajdrova, R.; Moore, J. C.; Baldenius, K.; Bornscheuer, U.T. Biocatalysis: Enzymatic synthesis for industrial applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60(1),88-119; [CrossRef]

- Gilio, A. K.; Thorpe, T. W.; Turner, N.; Grogan, G. Reductive aminations by imine reductases: from milligrams to tons. Chem. Science 2022, 13, 4697–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benítez-Mateos, A. I.; Roura, P. D.; Francesca, P. Multistep enzyme cascades as a route towards green and sustainable pharmaceutical syntheses. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G. F. S.; Seong-Heun Kim, S.-H.; Castagnolo, D. Harnessing biocatalysis as a green tool in antibiotic synthesis and discovery. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 30396–30410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D. R.; Lohman, D. C.; Wolfenden, R. Catalytic proficiency: The extreme case of S–O cleaving sulfatases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J. John Cornforth (1917–2013). Nature 2014, 506, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunitz, J. Vladimir Prelog (1906-98). Nature 1998, 391, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, R.; Mallojjala, S: C. ; Wheeler, S: E. Electrostatic interactions in asymmetric organocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 1990–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M. S.; Jacobsen, E. N. Asymmetric catalysis by chiral hydrogen-bond donors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1520–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal P., K. A biophysical perspective on enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, R. A. Enzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism, and Data Analysis. 3rd. Ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New Jersey, USA, 2023; ISBN: 9781119793250.

- Goodman, C. Jean-Marie Lehn. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, P. The shape of things. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiraju, G. Chemistry beyond the molecule. Nature 2001, 412, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, M. Donald J. Cram (1919–2001). Nature 2001, 412, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Helgeson, R. C.; Houk, K. N. Building on Cram’s legacy: stimulated gating in hemicarcerand. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2168–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifazi, D. A universal receptor. Nature Nanotech. 2013, 8, 896–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, C. R.; Ling, S.; Jacobsen, E. N. The cation-pi interaction in small-molecule catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12596–12624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornscheuer, U. T.; Huisman, G-W. ; Kazlauskas, R.; Lutz, S.; Moore, J. C.; Robins, K. Engineering the third wave of biocatalysis. Nature 2012, 485(7397), 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. S.; Liu, D. R. Methods for the directed evolution of proteins. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, B. A.; Hyster, T. K. Emerging strategies for expanding the toolbox of enzymes in biocatalysis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 55, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. P.; Peñafel, I.; Cosgrove, S. C.; Turner, N. J. Biocatalysis using immobilized enzymes in continuous flow for the synthesis of fine chemicals. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2019, 23, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsalami, S. M.; Mirsalami, M.; Ghodousian, A. Techniques for immobilizing enzymes to create durable and effective biocatalysts. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.; Hodgson, D. R. W.; O'Donoghue, A. C. Going full circle with organocatalysis and biocatalysis: The latent potential of cofactor mimics in asymmetric synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 7619–7629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.; Gocke, D.; Pohl, M. Exploitation of ThDPdependent enzymes for asymmetric chemoenzymatic synthesis. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 2894–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasparyan, E.; Richter, M.; Dresen, C.; Walter, L. S.; Fuchs, G.; Leeper, F. J.; Wacker, T.; Andrade, S. L.; Kolter, G.; Pohl, M.; Müller, M. Asymmetric Stetter reactions catalyzed by thiamine diphosphate-dependent enzymes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 9681–9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouali, N.; Gana, I.; Dorra, A.; Khelifi, F.; Nouioui, A.; Masri, W.; Belwaer, I.; Hayet Ghorbel, H.; Hedhili, A. Potential toxic levels of cyanide in almonds (Prunus amygdalus), apricot kernels (Prunus armeniaca), and almond syrup. Hindawi Publishing Corporation ISRN Toxicology (Hindawi Publ. Corp.) 2013, article nb. 610648, pp. [CrossRef]

- Wöhler, F.; Liebig, J. Ueber die Bildung des Bittermandelöls. Ann. Pharm. 1837, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthaler, L. Durch Enzyme bewirkte asymmetrische Synthesen. Biochem. Z., 1908, 14, 238–253. [Google Scholar]

- Effenberger, F. Synthesis and reactions of optically active cyanohydrins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1994, 33, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effenberger, F.; Förster, S.; Wajant, H. Hydroxynitrile lyases in stereoselective synthesis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000, 11, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkarthofer, T.; Skranc, W. , Schuster, C.; Griengl, H. Potential and capabilities of hydroxynitrile lyases as biocatalysts in the chemical industry. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 76, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashipour, M.; Asano, Y. Hydroxynitrile lyases insights into biochemistry, discovery, and engineering. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 1121–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prixa, B. V.; Padhi, S K. Hydroxynitrile lyase discovery, engineering, and promiscuity towards asymmetric synthesis: Recent progress. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reetz, M. Directed evolution of enantioselective enzymes: An unconventional approach to asymmetric catalysis in organic chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 5767–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 96. Arnold, F. H. Innovation by evolution: Bringing new chemistry to life (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 14420–14426. [CrossRef]

- Bornscheuer, U. T.; Hauer, B.; Jaeger, K. E.; Schwaneberg, U. Directed evolution empowered redesign of natural proteins for the sustainable production of chemicals and pharmaceuticals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. K.; Li, F-L. ; Lin, Z.; Lin, G-Q.; Hong, R.; Yu, H-L.; Xu, J-H. Structure-guided tuning of a hydroxynitrile lyase to accept rigid pharmaco aldehydes. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5757–5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reetz, M. T. ; García-Borràs. The unexplored importance of fleeting chiral intermediates in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14939–14950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purkarthofer, T.; Gruber, K.; Gruber-Khadjawi, M.; Waich, K.; Skranc, W.; Mink, D.; Griengl, H. A biocatalytic Henry reaction--the hydroxynitrile lyase from Hevea brasiliensis also catalyzes nitroaldol reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3454–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhshuku, K.; Asano, Y. Synthesis of (R)-β-nitro alcohols catalyzed by R-selective hydroxynitrile lyase from Arabidopsis thaliana in the aqueous-organic biphasic system. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 153(3-4),153-159. [CrossRef]

- von Langermann, J.; Nedrud, D. M.; Kazlauskas, R. J. Increasing the reaction rate of hydroxynitrile lyase from Hevea brasiliensis toward mandelonitrile by copying active site residues from an esterase that accepts aromatic esters. Chembiochem. 2014, 15, 1931–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekerle-Bogner,M. ; Gruber-Khadjawi, M.; Wiltsche, H.; Wiedner, R.; H. Schwab, H.; Steiner, K. (R)-Selective nitroaldol reaction catalyzed by metal-dependent bacterial hydroxynitrile lyases ChemCatChem, 2016, 8, 2214–2216. [CrossRef]

- Priya, B. V.; Rao, D. H. S.; Chatterjee, A.; Padhi, S. K. Hydroxynitrile lyase engineering for promiscuous asymmetric Henry reaction with enhanced conversion, enantioselectivity and catalytic efficiency. Chem. Commun. 2023, 12274–12277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busto, E.; Gotor-Fernández, V.; Gotor, V. Hydrolases: catalytically promiscuous enzymes for non-conventional reactions in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, (11), 4504–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Iglesias, M,.; Gotor-Fernández, V. Recent advances in biocatalytic promiscuity: hydrolase-catalyzed reactions for nonconventional transformations. Chem. Rec, 2015; 743–759. [CrossRef]

- Poddar, H.; Rahimi, M.; Geertsema, E. M.; Thunnissen, A. M.; Poelarends, G. J. Evidence for the formation of an enamine species during aldol and Michael-type addition reactions promiscuously catalyzed by 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase. Chembiochem. 2015, 16, 738–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copley, S.D. Shining light on enzyme promiscuity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017, 47, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.-C.; Lee, L. F. H.; Mittal, R. S. D.; Ravikumar, P. R.; Chan, J. A.; Sih, C. J.; Capsi, E.; Eck, C. R. Preparation of (R)- and (S)-mevalonic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 4144–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, P.; Waespe-Sarevi, N.; Tamm, C.; Gawronska, K.; Gawronski, J. A study of stereoselective hydrolysis of symmetrical diesters with pig liver esterase. Helv. Chim. Acta 1983, 66, 2501–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Urdiales, E.; Alfonso, I.; Gotor, V. Enantioselective enzymatic desymmetrization in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105(1), 313–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutter, U.; Iding, H.; Spurr, P.; Wirz, B. New, efficient synthesis of Oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu) via enzymatic desymmetrization of a meso-1,3-cyclohexanedicarboxylic acid diester. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 4895–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedee, B. R.; Soni, S.; Sharma, M.; Bhaumik, J.; Laha, J. K.; Banerjee, U. C Promiscuity of lipase-catalyzed reactions for organic synthesis: A recent update. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 2441–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W. Natural polypropionates in 1999–2020: An overview of chemical and biological diversity. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, P.; Sordo Gonzalo, J. A. Expeditious asymmetric synthesis of polypropionates relying on sulfur dioxide-induced C–C bond forming reactions. Catalysts 2021, 11, article nb.1267, pp. 1-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chênevert, R.; Rose, Y. S. Enzymatic desymmetrization of a meso polyol corresponding to the C(19)-C(27) segment of Rifamycin S. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 1707–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Tsutsumi, S.; Ihori, T.; Ohta, H. Enzyme-mediated enantioface-differentiating hydrolysis of alpha-substituted cycloalkanone enol esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 9614–9619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, J. T.; Hong, A. Y.; Stoltz, B. M. Enantioselective protonation. Nat. Chem, 2009; 359–369. [Google Scholar]

- Neuberg, C. Biochemical reductions at the expense of sugars. Adv. Carbohyd. Chem. 1949, 4, 75–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sih, C. J.; Chen, C-S. Microbial asymmetric catalysis—Enantioselective reduction of ketones [New Synthetic Methods]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1984, 23, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebach, D.; Roggo, S.; Maetzke, T.; Braunschweiger, H.; Cercus, C.; Krieger, M. Diasterio- und enantioselektive Reduktion von β-Ketoestern mit Cyclopentanon-, Cyclohexanon-, Piperidon- und Tetralon-Struktur durch nicht fermentierende Bäcker-Hefe. Helv. Chim. Acta 1987, 70, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Hosomi, K.; Araki, M.; Nishida, K.; Node, M. Enantioselective reduction of σ-symmetric bicyclo[3.3.0]octane-2,8-diones with baker's yeast. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1995, 6, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R. de S. The use of Baker’s yeast in the generation of asymmetric centers to produce chiral drugs and other compounds. Crit. Rev. Biotechn. [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, A.; Dlugy, C.; Tavor, D.; Blumefeld, J. Baker’s yeast catalyzed asymmetric reduction in glycerol. Tetrahedon Asymmetry 2006, 17, 2043–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. C.; Pollard, D. J.; Kosjek, B.; Devine, P. N. Advances in the enzymatic reduction of ketones. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 1412–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberg, C.; Nord, F. F. Die phytochemische Reduktion der Ketone. Biochemische Darstellung optisch-aktiver sekundärer Alkohole. Ber. deutch. chem. Ges. 1919, 52, 2237–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, R.; Prosser, H.; Fickentscher, L.; Lanyi, J.; Mosher, H. S. Asymmetric Reductions. XII. Stereoselective Ketone Reductions by Fermenting Yeast. Biochemistry 1964, 3, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prelog, V. Specification of the stereospecificity of some oxido-reductases by diamond lattice sections. Pure Appl. Chem. 1964, 9, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

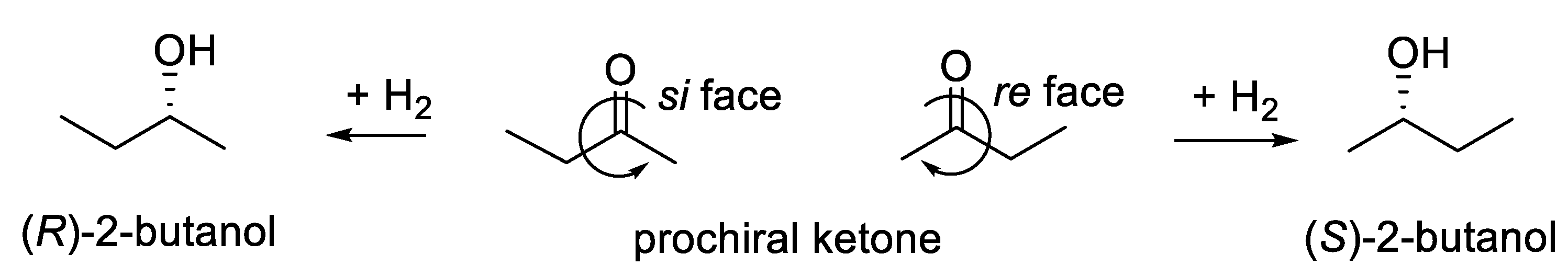

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "prochirality". [CrossRef]

- Burnier, G. , Vogel, P. Synthesis and circular dichroism of optically pure (-)-( 1S,2S,5S)-5-methoxy-3,4,6,7-tetramethylidenebicyclo[3.2.l]oct-2-yl derivatives. Baker's yeast reduction of 4-methoxy-5,6,7,8-tetramethylidenebicyclo[2.2.2]octan-2-one. Helv. Chim. Acta 1990, 73, 985–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, J. A.; Dull, D. L.; Mosher, H. S. J. Org. Chem. 1969, 34(9), 2543-2549. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Qiu, H. Recent advances in chiral liquid chromatography stationary phases for pharmaceutical analysis. J. Chromat. A. 2023, 1708, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utaka, M.; Konishi, S.; Mizuoka, A.; Ohkubo, T.; Sakai, T.; Tauboi, S. ; Takeda, A: Asymmetric reduction of the prochiral carbon-carbon double bond of methyl 2-chloro-2-alkenoates by use of fermenting bakers' yeast J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 4989–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

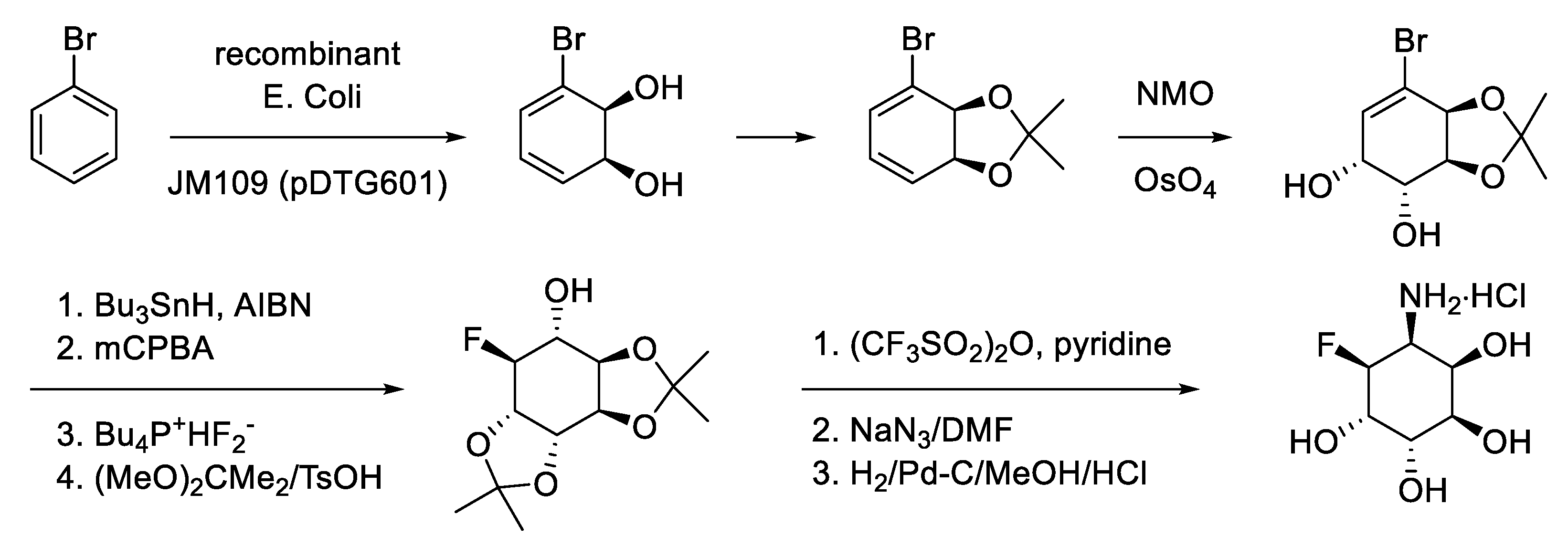

- Gibson, D. T.; Koch, J. R.; Schuld, C. L.; Kallio, R. E. Oxidative degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons by microorganisms. II. Metabolism of halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons. Biochemistry 1968(11), 3795–3802. [CrossRef]

- Zylstra, G. J.; Gibson, D. T. Toluene degradation by Pseudomonas putida F1. Nucleotide sequence of the todC1C2BADE genes and their expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 14940–14946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endoma, M. A.; Bui, V. P.; Hansen, J.; Hudlicky, T. Medium-scale preparation of useful metabolites of aromatic compounds via whole-cell fermentation with recombinant organisms. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2002, 6, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. A. Microbial arene oxidations. Org. React, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, H. A. J. The use of cyclohexa-3,5-diene-1,2-diols in enantiospecific synthesis. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1992, 31, 795–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudlicky, T.; Gonzalez, D.; Gibson, D. T. Enzymatic dihydroxylation of aromatics in enantioselective synthesis: expanding asymmetric methodology. Aldrichim. Acta 1999, 32, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwell, M. G.; Edwards, A: J. ; Harfoot, G. J.; Jolliffe, K. A.; McLeod, M. D.; McRae, K. J.; Stewart, S. G.; Vögtle, M. Chemoenzymatic methods for the enantioselective preparation of sesquiterpenoid natural products from aromatic precursors. Pure Appl. Chem. 2003, 75, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudlicky, T.; Reed, J. W. Applications of biotransformations and biocatalysis to complexity generation in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 8, 3117–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, E. S.; Banwell, M. G.; Buckler, J. N.; Yan, Q.; Lan, P. The exploitation of enzymatically-derived cis-1,2-dihydrocatechols and related compounds in the synthesis of biologically active natural products. Chem. Rec. 2018, 18, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudlicky, T. Benefits of unconventional methods in the total synthesis of natural products. ACS Omega, 2018, 3, 17326–17340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart Stollmaier, J.; Hudlicky, T. Sequential enzymatic and electrochemical functionalization of bromocyclohexadienediols: Application to the synthesis of (−)-conduritol C. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

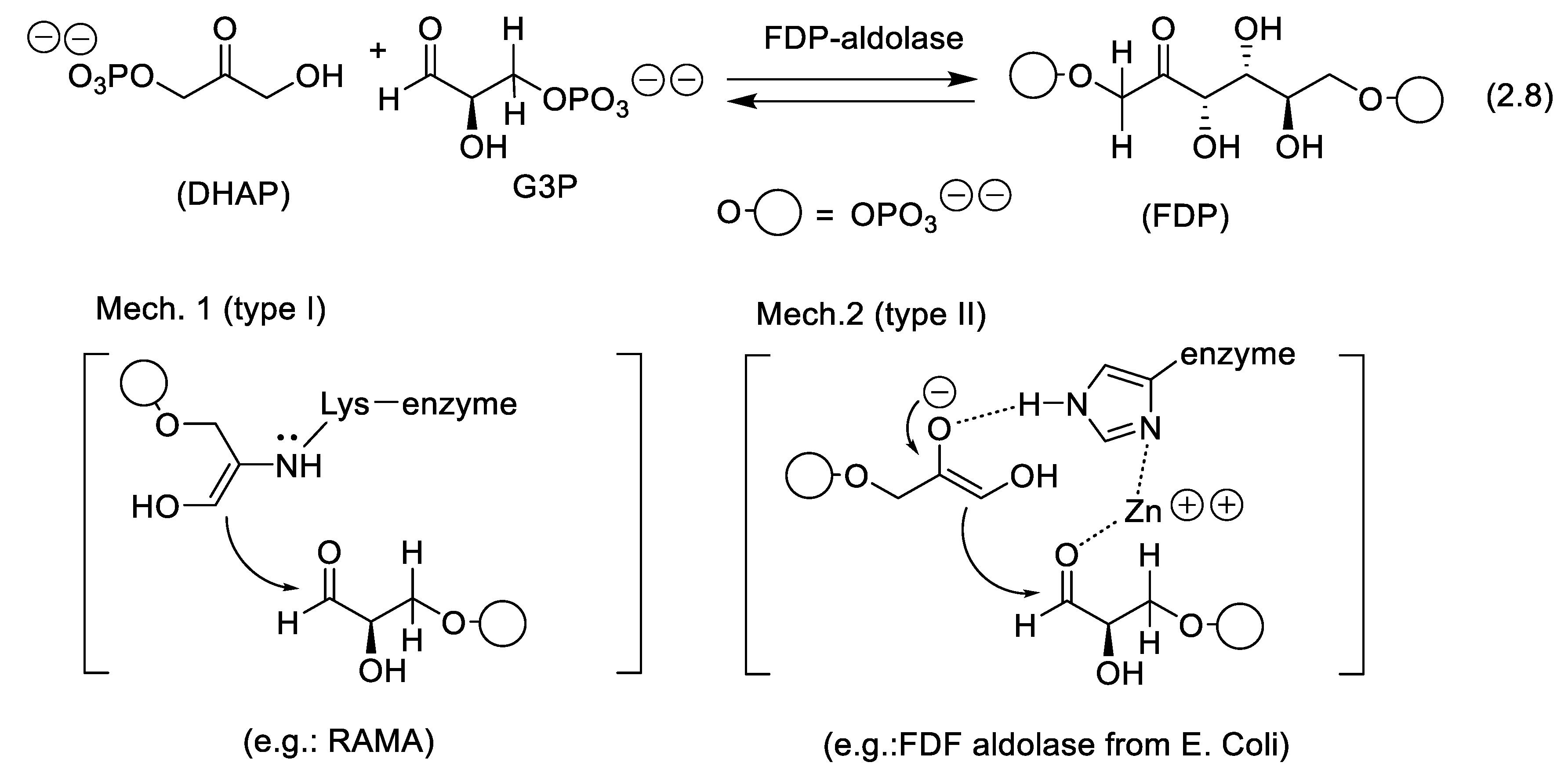

- Meyerhof, O. , Lohmann, K. Über den Nachweis von Triosephosphorsäure als Zwischenprodukt bei der enzymatischen Kohlehydratspaltung. Naturwissenschaften 1934, 22, 134–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresge, N.; Simoni, R. D.; Hill, R. L. Otto Fritz Meyerhof and the elucidation of the glycolytic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. , Christian, W. Isolierung und Kristallisation des Gärungsferments Enolase. Naturwissenschaften 1941, 29, 589–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O.; Christian, W. Isolierung und Kristallisation des Gärungsferments Zymohexase. Naturwissenschaften 1942, 30, 731–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O.; Christian, W. Isolierung und Kristallisation des Gärungsferments Zymohexase Biochem. Z. 1943, 314, 149–176. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, O. C.; Rutter, W. J. Preparation and properties of yeast aldolase, J. Biol. Chem. 1961, 236, 3177–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O.; Gawehn, K. Z.; Lange, G. Ueber das Verhalten von Ascites-Kbresbzellen zu Zymhexase. Naturforsch. 1954, 9b, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. K.; Sephton, H. H. Synthesis of D-glycero-D-altro-, L-glycero-L-galacto-, D-glycero-L-gluco-, and D-glycero-L-galato-octulose. Can J. Chem. 1960, 38, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarski, M. D.; Simon, E. S.; Bischofberger, N.; Fessner, W.-D.; Kim, M.-J.; Lees, W.; Saito, T.; Waldmann, H.; Whitesides, G. M. J. Am. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 627–635. [CrossRef]

- Toone, E. J.; Simon, E. S.; Bednarski, M. D.; Whitesides, G. M. Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of carbohydrates. Tetrahedron 1989, 45, 5365–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-H.; Halcomb, R. L.; Ichikawa, Y.; Kajimoto, T. Enzymes in organic synthesis: Application to the problems of carbohydrate recognition (Part 2). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995, 34, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C-H. ; Halcomb, R. L.; Ochikawa, Y.; Kajimoto. Enzymes in organic synthesis: Application to the problems of carbohydrate recognition (Part 1). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995, 34, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machajewski, T. D.; Wong, C.-H. The catalytic asymmetric aldol reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 1352–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, S. M.; Greenberg, W. A.; Wong, C-H. Recent advances in aldolase-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007, 349, 1308–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapés, P.; Garrabou, X. Current trends in asymmetric synthesis with aldolases. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2263–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hélaine, V; Gastaldi, C; Lemaire, M.; Clapès, P.; Guérard-Hélaine, C Recent advances in the substrate selectivity of aldolases. ACS Catal 2022, 12, 733–761.

- Lee, S-H. ; Yeom, S-J.; Kim. S-E.; Oh, D-K. Development of aldolase-based catalysts for the synthesis of organic chemicals. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, W.; Whitesides, G. M. A New approach to cyclitols based on rabbit muscle aldolase (RAMA). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 9670–9671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai, T., Kajimoto, T. Synthesis of biologically relevant monosaccharides. In: Fraser-Reid, B. O.; Tatsuta, K.; Thiem, J. (eds). Glycoscience: Chemistry and Chemical Biology I–III. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2001, Chapt. 4.3, 907-1021. [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, M. G. , Camici, M., Mascia, L., Sgarrella, F., Ipata, P. L. Pentose phosphates in nucleoside interconversion and catabolism. FASEB J. 2006, 273, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

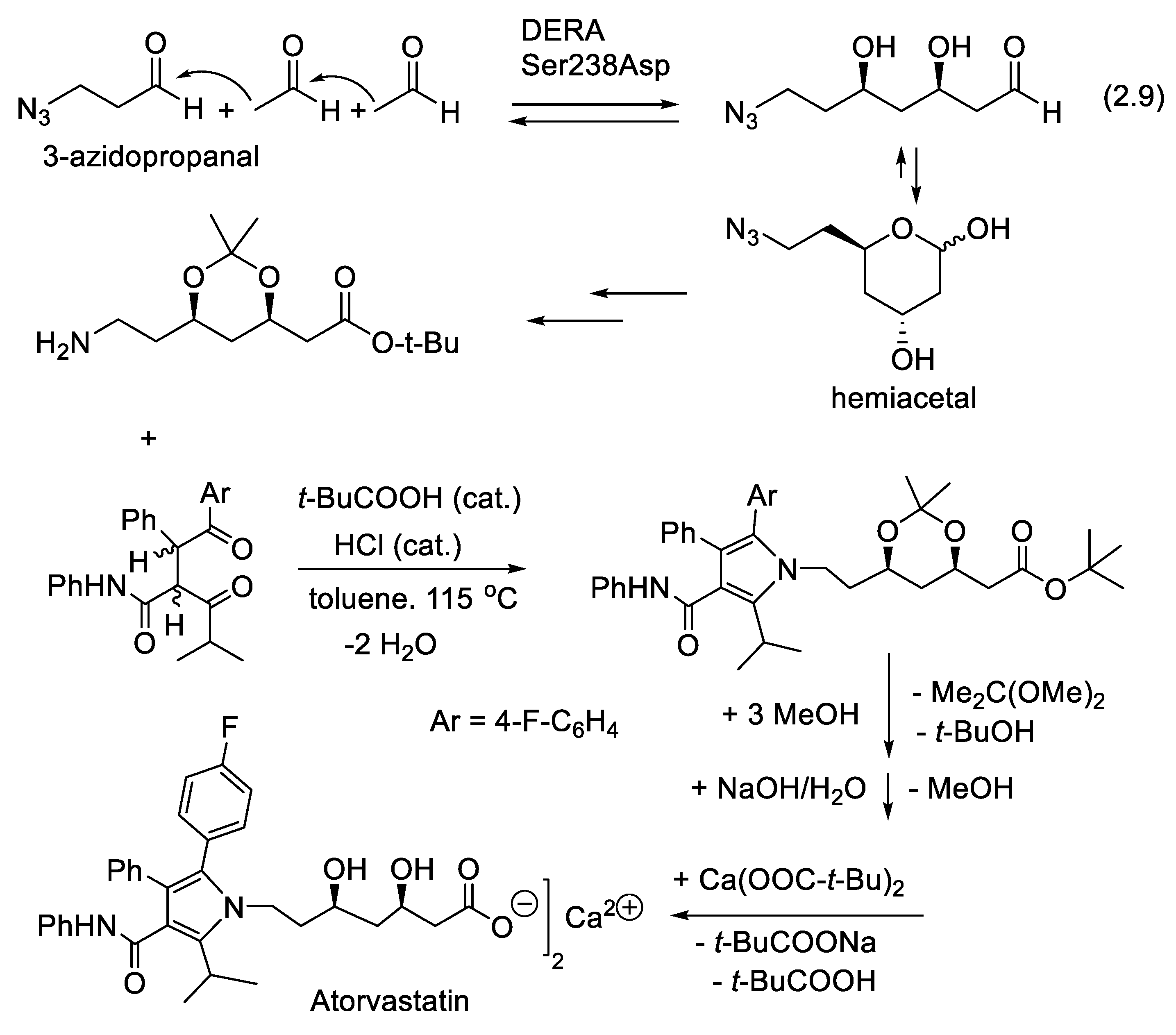

- Gijsen, H. J. M. , Wong, C.-H., Sequential one-pot aldol reactions catalyzed by 2-deoxyribose-5-phosphate aldolase and fructose-1,6-diphosphate aldolase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsen, H. J. M. , Wong, C.-H., Sequential three- and four-substrate aldol reactions catalyzed by aldolases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 7585–7591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, W. A.; Varvak, A.; Hanson, S. R.; Wong, K.; Huang, H.; Chen, P.; Burk, M. J. , Development of an efficient, scalable, aldolase-catalyzed process for enantioselective synthesis of statin intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5788–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of building blocks for statin side chains. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wong, C. H. Aldolase-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of novel pyranose synthons as a new entry to heterocycles and epothilones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1404–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ošlaj, M.; Cluzeau, J.; Orkić, D.; Kopitar, G.; Mrak, P.; Časar,Z. A highly productive, whole-cell DERA chemoenzymatic process for the production of key lactonized side-chain intermediates in statin synthesis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z. Some recent examples in developing biocatalytic pharmaceutical processes, in Asymmetric Catalysis, Eds.: Blaser, H-U.; Federsel, H-J. Wiley Online Books, 2010. Chap. 1. pp. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Dückers, N.; Baer, K.; Simon, S.; Gröger, H.; Hummel, W. Threonine aldolases-screening, properties and applications in the synthesis of non-proteinogenic beta-hydroxy-alpha-amino acids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 88, 409−424; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, S. E.; Stewart, J. D. Threonine aldolases. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 88, 57–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligibel, M.; Moore, C.; Bruccoleri, R.; Snajdrova, R. Identification and application of threonine aldolase for synthesis of valuable α-amino, β-hydroxy-building blocks. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom, 2020; 1868, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesko, K.; Reisinger, C.; Steinreiber, J.; Weber, H.; Schürmann,M. ; Griengl, H. Four types of threonine aldolases: Similarities and differences in kinetics/thermodynamics. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2008, 52, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T. A.; Heine, D.; Qin, Z.; Wilkinson, B. An l-threoninetransaldolase is required for l-threo-β-hydroxy-α-amino acid assembly during Obafluorin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, S. E.; Stewart, J. D. Threonine aldolases. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 88, 57–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fansher, D. J.; Palmer, D. R. J. A. Type 1 aldolase, NahE, catalyzes a stereoselective nitro-Michael reaction: Synthesis of β-aryl-γ-nitrobutyric acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e292214539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. J.; Domann, S.; Nelson, A.; Berry, A. Modifying the stereochemistry of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction by directed evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3143–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, S.; Kullartz, I.; Pietruszka, J. Cloning and characterisation of a new 2-deoxy-D-ribose-5-phosphate aldolase from Rhodococcus erythropolis. J. Biotechn. 2012, 161, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, S.; Roldan, R.; Joosten, H. J.; Clapés, P.; Fessner, W. D. Complete switch of reaction specificity of an aldolase by directed evolution in vitro: Synthesis of generic aliphatic aldol products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 57(32),10153–10157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Feng, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, D.; Ma, Y. Improving and inverting cβ-stereoselectivity of threonine aldolase via substrate-binding-guided mutagenesis and a stepwise visual screening. ACS Catal, 2019; 9, 4462–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widersten, M. Engineering aldolases for asymmetric synthesis. Methods Enzymol. 2020, 644, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Yu, H.; Fang, S.; Chen, K.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Xu, G.; Yang, L.; Wu, J. Directed evolution of L-threonine aldolase for the diastereoselective synthesis of β-hydroxy-α-amino acids. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 3198–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W. Comprehensive screening strategy coupled with structure-guided engineering of l-threonine aldolase from Pseudomonas putida for enhanced catalytic efficiency towards l-threo-4-methylsulfonylphenylserine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.; Lerner, R. A.; Barbas, C. F. III. Efficient aldolase catalytic antibodies that use the enamine mechanism of natural enzymes. Science 1995, 270, 1797–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, B.; Shabat, D.; Barbas, C. F. III.; Lerner, R. A. Enantioselective total synthesis of some Brevicomins using aldolase antibody 38C2. Chem. Eur. J. 1998, 4, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, B.; Shabat, D.; Zhong, G.; Turner, J. M.; Li, T.; Bui, T.; Anderson, J.; Lerner, R. A.; Barbas, C. F. III. A catalytic enantioselective route to hydroxy-substituted quaternary carbon centers: resolution of tertiary aldols with a catalytic antibody. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 7283–7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Hu, Q.; Fu, Y.; Tong, Y.; Zhou, Z. Design and evolution of an enzyme for the asymmetric Michael addition of cyclic ketones to nitroolefins by enamine catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönherr, H.; Cernak, T. Profound methyl effects in drug discovery and a call for new C-H methylation reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12256–12267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetzsche, L. E.; Narayan A. R., H. Broadening the scope of biocatalytic C-C bond formation. Nat. Rev. Chem, h: 334-346, 1038. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, S. , Kuzelka, K. P., Guo, R.; Krohn-Hansen, B.; Wi, J.; Nair, S. K.; Yang, Y. A biocatalytic platform for asymmetric alkylation of α-keto acids by mining and engineering of methyltransferases. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, B. Introduction: organocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5413–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, D. W. C. The advent and development of organocatalysis. Nature 2008, 455, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, C.; Guidotti, M. Organocatalysts for enantioselective synthesis of fine chemicals: definitions, trends and developments. ScienceOpen Res. 2015, 0, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S. H.; Tan, B. Advances in asymmetric organocatalysis over the last 10 years. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassaletta, J. M. Spotting trends in organocatalysis for the next decade. Nat. Commun, 3787; 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; He, X-H. ; Liu, Y-Q.; He, G.; Peng, C.; Li, J-L. Asymmetric organocatalysis: an enabling technology for medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 122–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Mancheño, O.; Waser, M. Recent developments and trends in asymmetric organocatalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, E.; Prieto, L.; Milelli, A. Asymmetric organocatalysis: A survival guide to medicinal chemists. Molecules 2023, 28, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P. T.; Warner, J. C. Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, Oxford, 2000; online edn, Oxford Academic, 31 Oct. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, B. M. The atom economy-a search for synthetic efficiency. Science 1991, 254, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

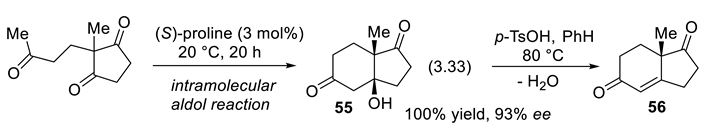

- List, B.; Lerner, R. A.; Barbas, C. F. III. Proline-catalyzed direct asymmetric aldol reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrendt, K. A.; Borths, C. J.; MacMillan, D. W.C. New strategies for organic catalysis: The first highly enantioselective organocatalytic Diels−Alder reaction, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122(17), 4243–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, B. Asymmetric aminocatalysis, Synlett 2001(11), 1675-1686; https//doi.org/ 10.1055/s-2001-18074.

- Melchiorre, P.; Marigo, M.; Carlone, A.; Bartoli, G. Asymmetric aminocatalysis - Gold rush in organic chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6138–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.; Worgull, D.; Zweifel, T.; Gschwend, B.; Bertelsen, S.; Jorgensen, K. A. Mechanisms in aminocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 632–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, F. Amines as catalysts: Dynamic features and kinetic control of catalytic asymmetric chemical transformations to form C−C bonds and complex molecules. Chem. Rec. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retamosa, M. de G.; Blanco-López, E.; Poyraz, S.; Döndas, H. A.; Sansano, J. M.; Cossio. F. R. Chap.3: Enantioselective C–C, C–halogen and C–H bond forming reactions promoted by organocatalysts based on non-proteinogenic α-amino acid derivatives. Adv. Catal. 2023, 73, 143–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoevenagel, E. Ber .dtsch. chem. Ges. 1896, 29, 172–174. [CrossRef]

- List, B. Emil Knoevenhagel and the roots of aminocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1730–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, A. G.; Jacobsen, E. N. Small-molecule H-bond donors in asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5713–5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Deiana, L.; Zhao, G. L.; Sun, J.; Córdova, A. Dynamic one-pot three-component catalytic asymmetric transformation by combination of hydrogen-bond-donating and amine catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 7624–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R. R.; Jacobsen, E. N. Attractive noncovalent interactions in asymmetric catalysis: links between enzymes and small molecule catalysts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010, 107, 20678–20685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, A.; Sinibaldi, A.; Nori, V.; Giorgianni, G.; Di Carmine, G.; Pesciaioli, F. Synergistic strategies in aminocatalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, Q-Q. ; Du, W.; Chen, Y-C. Asymmetric organocatalysis involving double activation. Tetrahedron Chem. 2022, 2, article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Lin, Q.; Luo, S. Enantioselective transformations by “1 + x” synergistic catalysis with chiral primary amines. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 1523–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson Afewerki, S.; Córdova. A. Combinations of aminocatalysts and metal catalysts: A powerful cooperative approach in selective organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 13512–13570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicewicz, D. A.; MacMillan, D. W. Merging photoredox catalysis with organocatalysis: the direct asymmetric alkylation of aldehydes. Science 2008, 322, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welin, E. R.; Warkentin, A. A; Conrad, J. C.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Enantioselective α-alkylation of aldehydes by photoredox organocatalysis: Rapid access to pharmacophore fragments from β-cyanoaldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 968–9672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvi, M.; Melchiorre, P. Enhancing the potential of enantioselective organocatalysis with light. Nature 2018, 554, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredig, G.; Fiske, P. S. Biochem. Z. 1912, 46, 7–23; Fiske, P. S. Durch katalysatoren bewirkte asymmetrische synthese (Doctoral dissertation, ETH Zurich) 1911; https://www.researchcollection. ethz.ch/handle/20.500.11850/136453.

- Pracejus, H. Organische Katalysatoren. LXI. Asymmetrische Synthesen mit Ketenen. I. Alkaloid-katalysierte asymmetrische Synthesen von α phenyl-proponsaüreestern. Liebigs Ann. Chem, 1960; 634, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G. S. , Yeboah, E. M. Recent applications of Cinchona alkaloid-based catalysts in asymmetric addition reactions. Rep. Org.Chem. 2016, 6, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, E. M.O.; Yeboah, S. O.; Singh, G. S. Recent applications of Cinchona alkaloids and their derivatives as catalysts in metal-free asymmetric synthesis. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 1725–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Miyairi, S. Recent advances in cinchona alkaloid catalysis for enantioselective carbon-nitrogen bond formation reactions. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolani, C.; Centonze, G.; Righi, P.; Bencivenni, G. Role of cinchona alkaloids in the enantio- and diastereoselective synthesis of axially chiral compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 3551–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreiro, E. P.; Burke, A: J. ; Hermann, G. J.; Federsel, H-J. Continuous flow enantioselective processes catalyzed by cinchona alkaloid derivatives. Tetrahedron Green Chem. 2023, 1, article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahdenpera, A. S. K.; Dhankhar, J.; Davies, D. J.; Lam, N. Y. S.; Bucos, P. D.; De la Vega-Hernández, K.; Philipps, R. J. Chiral hydrogen atom abstraction catalyst for the enantioselective epimerization of meso-diols. Science 2024, 386, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitesell, J. K.; Felman, S. W. Asymmetric induction. 3. Enantioselective deprotonation by chiral lithium amide bases. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 755–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblum, N.; DeLaMare, H. E. The base-catalyzed decomposition of dialkyl peroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 880–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenbuch, J.-P.; Vogel, P. Asymmetric induction in the rearrangement of monocyclic endoperoxides into γ-hydroxy-α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. Chem. Commun. 1980, (22), 1062–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staben, S. T.; Linghu. ; Toste, F. D. Enantioselective synthesis of gamma-hydroxyenones by chiral base-catalyzed Kornblum DeLaMare rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 12658–12659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.; Candeias, N. R.; Barbas III, C. F. Dimeric quinidine-catalyzed enantioselective aminooxygenation of oxindoles: An organocatalytic approach to 3-hydroxyoxindole derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 5574–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lian, Z.; Xu, Q, Shi, M. Asymmetric [4+2] annulations of isatins with but-3-yn-2-one. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 3344–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H. C.; Van Nieuwenhze, M. S.; Sharpless, K. B. Catalytic asymmetric dihydroxylation. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2483–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelMonte, A. J.; Haller, J.; Houk, K. N.; Sharpless, K. B.; Singleton, D. A.; Strassner, T.; Thomas, A. A. Experimental and theoretical kinetic isotope effects for asymmetric dihydroxylation. Evidence supporting a rate-limiting "(3 + 2)" cycloaddition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 9907–9908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentges, S. G.; Sharpless, K. B. Asymmetric induction in the reaction of osmium tetroxide with olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 4263–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, E. N.; Markó, I.; Mungall, W. S.; Schröder, G.; Sharpless, K. B. Asymmetric dihydroxylation via ligand-accelerated catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 116, 1968–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, B.; Ali, A. A.; Boruah, P. R.; Sarma, D.; Barua, N. C. Pd(OAc)2 and (DHQD)2PHAL as a simple, efficient and recyclable/reusable catalyst system for Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions in H2O at room temperature. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 2440–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. A.; Chetia, M.; Saikia, P. J.; Sarma, D. (DHQD)2PHAL ligand-accelerated Cu-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition reactions in water at room temperature. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 64388–64392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gao, L. X.; Mai, W. P.; Xia, A. X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, S. B. Enantioselective iodolactonization catalyzed by chiral quaternary ammonium salts derived from cinchonidine, J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 2874–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, D. C.; Yousefi, R.; Jaganathan, A.; Borhan, B. An organocatalytic asymmetric chlorolactonization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 3298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.; Braddock, D. C.; Jones, A. X.; Clark, S. Catalytic asymmetric bromolactonization reactions using (DHQD)2PHAL-benzoic acid combinations. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 7004–7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddock, D. C.; Lancaster, B. M. J.; Tighe, C. J.; White, A. J. P. Surmounting byproduct inhibition in an intermolecular catalytic asymmetric alkene bromoesterification reaction as revealed by kinetic profiling. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 8904–8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, H.; Wynberg, H. Addition of aromatic thiols to conjugated cycloalkenones, catalyzed by chiral beta-hydroxy amines. A mechanistic study of homogeneous catalytic asymmetric synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelli, T.; van der Haas, R. N. S.; van Maarseveen, J. H.; Hiemstra, H. Asymmetric organocatalytic Henry reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, L. Organocatalytic applications of cinchona alkaloids as a potent hydrogen-bond donor and/or acceptor to asymmetric transformations: A review. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2016, 13, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H.; Singh, V. K. Cinchona derivatives as bifunctional H-bonding organocatalysts in asymmetric ninylogous conjugate addition reactions. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCooey, S. H.; Connon, S. J. Urea- and thiourea-substituted cinchona alkaloid derivatives as highly efficient bifunctional organocatalysts for the asymmetric addition of malonate to nitroalkenes: inversion of configuration at C9 dramatically improves catalyst performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 6367–6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W-R. ; Su, Q.; Lin, N.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z-W.; Weng, J.; Lu, G. Organocatalytic synthesis of chiral CF3-containing oxazolidines and 1,2-amino alcohols: asymmetric oxa-1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of trifluoroethylamine-derived azomethine ylides: Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 3452–3458. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y-R. ; Xu, J.; Jiang, H-F., Fang, R-J., Zhang, Y-J., Chen, L., Sun, C., Eds.; Xiong, F. Bifunctional sulfonamide as hydrogen bonding catalyst in catalytic asymmetric reactions: Concept and application in the past decade. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, article nb. e202201081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Bhowmick, S.; Ghosh, A.; Chanda, T.; Bhowmick, K. C. Advances on asymmetric organocatalytic 1,4-conjugate addition reactions in aqueous and semi-aqueous media. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2017, 28, 849–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- a) Duhamel, L. C. R. C. R. Acad. Sci. 1976, 282C, 125-127 ; b) Duhamel, L.; Plaquevent, J.-C. Déracemisation par protonation enantioselective. Tetrahedron Lett. [CrossRef]

- Duhamel, L.; Duhamel, P.; Plaquevent, J.-C. Enantioselective protonations: fundamental insights and new concepts. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2004, 15, 3653–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, C.; Galindo, J. Catalytic enantioselective protonation of enolates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1994, 33, 1888–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, C. Enantioselective protonation of enolates and enols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996, 35, 2566–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, C. Catalytic enantioselective tauromerization of isolated enols. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007, 46, 7119–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. S.; Salunkhe, R. V.; Rane, R. A.; Dike, S. Y. Novel catalytic enantioselective protonation (proton transfer) in Michael addition of benzenethiol to α-acrylacrylates: synthesis of (S)-naproxen and α-arylpropionic acids or esters. Chem. Commun. 1991, (7), 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, K.; Ono, M.; Nagaoka, Y.; Tomioka, K. Catalytic enantioselective protonation of lithium ester enolates generated by conjugate addition of arylthiolate to enoates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, J. P.; Ellman, J. A. Conjugate addition-enantioselective protonation reactions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 1203–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, P.; Houk, K. N. Organic Chemistry: Theory, Reactivity, and Mechanisms in Modern Synthesis. Wiley VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany, 2019, Chap. 1.6.1, pp. 10-11; ISBN: 978-3-527-34532-8.

- Hintermann, L.; Ackerstaff, J.; Boeck, F. Inner workings of a cinchona alkaloid catalyzed oxa-Michael cyclization: Evidence for a concerted hydrogen-bond-network mechanism. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 2311–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.; Zhuang, W.; Jørgensen, K. A. Asymmetric conjugate addition of azide to α,β-unsaturated compounds catalyzed by cinchona alkaloids. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 5849–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukata, T.; Koga, K. Enantioselective protonation of achiral lithium enolates using a chiral amine in the presence of lithium bromide. Tetrahedron Asymmetry, 1993, 4, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviere, P.; Koga, K. An approach to catalytic enantioselective protonation of prochiral lithium enolates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 7589–7592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łowicki, D.; Watral, J.; Jelecki, M.; Bohusz, W.; Kwit, M. Stereoselective protonation of 2-methyl-1-tetralone lithium enolate catalyzed by salan-type diamines. Tetrahedron 2021, 86, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuhashi, K.; Ito, R.; Arai, T.; Yanagisawa, A. Catalytic asymmetric protonation of lithium enolates using amino acid derivatives as chiral proton sources. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 1721–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, T.; Dalla, V.; Marsais, F.; Dupas, G.; Oudeyer, S.; Levacher, V. Organocatalytic enantioselective protonation of silyl enolates mediated by cinchona alkaloids and a latent source of HF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7090–7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claraz, A.; Landelle, G.; Oudeyer, S.; Levacher, V. Asymmetric organocatalytic protonation of silyl enolates catalyzed by simple and original betaines derived from cinchona alkaloids. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 7693–7696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, H,; Baur, M. A. α-Amino acid derivatives by enantioselective decarboxylation. Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2854. [CrossRef]

- George, K. M.; Frantz, M.; Bravo-Altamirano, K.; LaValle, C. R.; Tandon, M.; Leimgruber, S.; Sharlow, E.R.; Lazo, J. S.; Wang, Q. J.; Wipf, P. Pharmaceutics 2011, 3(2), 186-22. [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.; Yamagami, M.; Vellalath, S.; Romo, D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 6527–6531. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y-L. ; Rodriguez, J.; Coquerel, Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Wei Du, W. ; Chen, Y-C. Modified cinchona alkaloid-catalysed enantioselective [4+4] annulations of cyclobutenones and 1-azadienes. Chem. Commun, 7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. W.; Chen, W.; Li, R.; Zeng, M.; Du, W.; Yue, L.; Chen, Y. C.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Deng, J. G. Highly asymmetric Michael addition to alpha,beta-unsaturated ketones catalyzed by 9-amino-9-deoxyepiquinine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, G.; Bosco, M.; Carlone, A.; Pesciaioli, F.; Sambri, L.; Melchiorre, P. Organocatalytic asymmetric Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indoles with simple alpha,beta-unsaturated ketones. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicario, J. L.; Badia, D.; Carrillo, L. Organocatalytic enantioselective Michael and hetero-Michael reactions. Synthesis 2007, (14), 2065–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Reisinger, C. M.; List, B. Catalytic asymmetric epoxidation of cyclic enones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6070–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooey, S. H.; Connon, S. J. Readily accessible 9-epi-amino cinchona alkaloid derivatives promote efficient, highly enantioselective additions of aldehydes and ketones to nitroolefins. Org Lett. 2007, 9, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.; Naganaboina, V. K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Guo, Q.; Rout, L.; Zhao, C-G. Organocatalytic highly enantioselective synthesis of β-formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonates. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 1729–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, P.; Beeson, T. D.; Conrad, J. C.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Enantioselective organocatalytic α-fluorination of cyclic ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1738–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Milani, R.; Pilati, T.; Priimagi, A.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2478–2601. [CrossRef]

- Beer, P. D.; Brown, A. Halogen bonding anion recognition. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 8645–8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutar, R. L.; Huber, S. M. Catalysis of organic reactions through halogen bonding. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 9622–9639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmann, A.; Pena, M. A.; Bolm, C. Organocatalysis through halogen-bond activation. Synlett 2008, (6), 900–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwano, S.; Suzuki, T.; Hosaka, Y.; Arai, T. A chiral organic base catalyst with halogen-bonding-donor functionality: asymmetric Mannich reactions of malononitrile with N-Boc aldimines and ketimines. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3847–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwano, S.; Nishida, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Arai, T. Catalytic asymmetric Mannich-type reaction of malononitrile with N-Boc α-ketiminoesters using chiral organic base catalyst with halogen bond donor functionality. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 1674–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarrigle, E.; Myers, E. L.; Illa, O.; Shaw, M. A, Riches S. L, Aggarwal, V. K. Chalcogenides as organocatalysts. Chem Rev. 2007, 107, 5841–5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breugst, M.; Koenig, J. J. σ-Hole interactions in catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 34, 5473–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zheng, M.; Xu, C.; Chen. F.-E. Harnessing noncovalent interaction of chalcogen bond in organocatalysis: From the catalyst point of view. Green Synth. Catal. 2021, 2, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makosza, M. Reactions of organic anions II. Catalytic alkylation of indene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1966, 38, 4621–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, C. M. Phase-transfer catalysis. I. Heterogeneous reactions involving anion transfer by quaternary ammonium and phosphonium salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helder, R.; Hummelen, J. C.; Laane, R. W. P. M.; Wiering, J. S.; Wynberg, H. Catalytic asymmetric induction in oxidation reactions. The synthesis of optically active epoxides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 1831–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluim, H.; Wynberg, H. Catalytic asymmetric induction in oxidation reactions. Synthesis of optically active epoxynaphthoquinones. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 2498–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cornwall, R. G.; Shi, Y. Organocatalytic asymmetric epoxidation and aziridination of olefins and their synthetic applications. Chem Rev. 2014, 114, 8199–8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moschona, F.; Savvopoulou, I.; Tsitopoulou, M.; Tataraki, D.; Rassias, G. Epoxide syntheses and ring-opening reactions in drug development. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolling, U. H.; Davis, P.; Grabowski, E. J. Efficient catalytic asymmetric alkylations. 1. Enantioselective synthesis of (+)-indacrinone via chiral phase-transfer catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 446–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M. J.; Bennett, W. D.; Wu, S. The stereoselective synthesis of α-amino acids by phase-transfer catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 2353–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, E.; Siva, A. Synthesis of asymmetric N-arylaziridine derivatives using a new chiral phase-transfer catalyst. Synthesis, 2005; 2022–2028. [Google Scholar]

- Lygo, B.; Wainwright, P. G. A new class of asymmetric phase-transfer catalysts derived from Cinchona alkaloids–application in the enantioselective synthesis of α-amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 8595–8598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, E. J.; Xu, F.; Noe, M. C. A rational approach to catalytic enantioselective enolate alkylation using a structurally rigidified and defined chiral quaternary ammonium salt under phase transfer conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 12414–12415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, E. J.; Zhang, F.-Y. Mechanism and conditions for highly enantioselective epoxidation of alpha,beta-enones using charge-accelerated catalysis by a rigid quaternary ammonium salt. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, E.; Nagai, A.; Hamasaki, A.; Tokunaga, M. Catalytic asymmetric hydrolysis: Asymmetric hydrolytic protonation of enol esters catalyzed by phase-transfer catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 7178–7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, S.; Maruoka, K. Recent developments in asymmetric phase-transfer reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4312–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Yasuda, N. Transfer catalysts: Large-scale industrial applications. Org. Proc. Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 1731–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, D. C. M.; Penso, M. New trends in asymmetric phase transfer catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Maruoka, K. Recent development and application of chiral phase-transfer catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5656–5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Yasuda, N. Contemporary asymmetric phase transfer catalysis: Large-scale industrial applications. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 1731–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. J.; Maruoka, K. Asymmetric phase-transfer catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haripriya, P. , Rai, R. Vijayakrishna, K. Polymer anchored cinchona alkaloids: Synthesis and their applications in organo-catalysis. Top. Curr. Chem. (Z) 2025, 383, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, M.; Cortigiani, M.; Monasterolo, C.; Torri, F.; del Fiandra, C.; Fuller, G.; Kelly, B.; Adamo, M. F. A. Development and scale-up of an organocatalytic enantioselective process to manufacture (S)-Pregabalin. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 1274–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgianni, G.; Bernardi, L.; Fini, F.; Pesciaioli, F.; Secci, F.; Carlone, A. Asymmetric organocatalysis—A powerful technology platform for academia and industry: Pregabalin as a case study. Catalysts 2022, 12, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Han, X-L. ; Yu, Y.; Cheng, C.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y.; Wu, K.; Li. Z.; Luo, J.; Deng, L. Organocatalytic asymmetric α-C–H functionalization of alkyl amines. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Y. Chiral phase-transfer catalysts with hydrogen bond: A powerful tool in the asymmetric synthesis. Catalysts 2019, 9, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, P.; Fernández, R.; Lassaletta, J. M. Organocatalytic asymmetric cyanosilylation of nitroalkenes. Chemistry 2010, 16, 7714–7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K. M.; Rattley, M. S.; Sladojevich, F.; Barber, D. M.; Nuñez, M. G.; Goldys, A. M.; Dixon, D. J. A new family of cinchona-derived bifunctional asymmetric phase-transfer catalysts: application to the enantio- and diastereoselective nitro-Mannich reaction of amidosulfones. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2492–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Woods, P. A.; Smith, M. D. Cation-directed enantioselective synthesis of quaternary-substituted indolenines. Chem. Science 2013, 4, 2907–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Fang, Y.; Gao. ; Wei, Z.; Cao, J.; Liang, D.; Lin, Y.; Duan, H. Bifunctional thiourea-ammonium salt catalysts derived from cinchona alkaloids: Cooperative phase-transfer catalysts in the enantioselective aza-Henry reaction of ketimines. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 1486–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Q.; Deng, Y. L.; Ling, D.; Li, T. T.; Chen, L. Z.; Jin, Z. C. ; Recent progress in chiral quaternary ammonium salt-promoted asymmetric nucleophilic additions. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 1973–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, T.; Shibuguchi, T.; Fukuta, Y.; Shibasaki, M. Catalytic asymmetric phase-transfer reactions using tartrate-derived asymmetric two-center organocatalysts. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 7743–7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waser, M.; Gratzer, K.; Herchl, R.; Müller, N. Design, synthesis, and application of tartaric acid derived N-spiro quaternary ammonium salts as chiral phase-transfer catalysts. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10(2), 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, L.; Tan, C.-H. Phase-transfer and ion-pairing catalysis of pentanidiums and bisguanidiniums. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Feng, X.; Liu, X. Chiral guanidines and their derivatives in asymmetric synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 8525–8540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, Z, Ye, X. ; Tan, C.-H, Ion-pair catalysts-pentanidinium. Chem. Record 2023, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. S.; Lu, K.; Li, C. X.; Zhao, Z, H. ; Zhang, X. M.; Zhang, F. M.; Tu, Y. Q. Chiral 1,2,3-triazolium salt catalyzed asymmetric mono- and dialkylation of 2,5-diketopiperazines with the construction of tetrasubstituted carbon centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, T.; Kameda, M.; Maruoka, K. ; Design of N-spiro C2-symmetric chiral quaternary ammonium bromides as novel chiral phase-transfer catalysts: synthesis and application to practical asymmetric synthesis of alpha-amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 5139–5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, T.; Sasaki, K.; Fukumoto, K.; Murase, Y.; Abe, N.; Ooi, T.; Maruoka, K. Phase-transfer-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation of α-benzoyloxy-β-keto esters: Stereoselective construction of congested 2,3-dihydroxycarboxylic acid esters. Chem. Asian. J. 2010, 5, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, H. W.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J. Y.; Lee, J. K.; Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Park, H.-g. Phase-transfer catalyzed enantioselective α-alkylation of α-acyloxymalonates: construction of chiral α-hydroxy quaternary stereogenic centers. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 77427–77430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C. M.; Franckevicius, V. The catalytic asymmetric allylic alkylation of acyclic enolates for the construction of quaternary and tetrasubstituted stereogenic centres. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 20, e202304289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Tan, S. M.; Tan, D.; Lee, R.; Tan, C. H. An enantioconvergent halogenophilic nucleophilic substitution (SN2X) reaction. Science 2019, 363, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novacek, J.; Waser, M. Syntheses and applications of (thio)urea-containing chiral quaternary ammonium salt catalysts. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2014(4), 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciber, L.; Požgan, F.; Brodnik, H.; Štefane, B.; Svete, J.; Waser, M.; Grošelj, U. Synthesis and catalytic activity of bifunctional phase-transfer organocatalysts based on camphor. Molecules 2023, 28, article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutar, R. L.; Engelage, E.; Stoll, R.; Huber, S. M. Bidentate chiral bis(imidazolium)-based halogen-bond donors: Synthesis and applications in enantioselective recognition and catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6806–6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, J- L. ; Terrett, J. A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. O-H hydrogen bonding promotes H-atom transfer from α-C-H bonds for C-alkylation of alcohols. Science 2015, 349, 1532–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J. A.; Adrianov, T.; Taylor, M. S. Understanding the origins of site selectivity in hydrogen atom transfer reactions from carbohydrates to the quinuclidinium radical cation: A computational study. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 5713–5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Huang, T.; Lin, Y-M. ; Gong, L. Advancements in organocatalysis for radical-mediated asymmetric synthesis: A recent perspective. Chem Catal. 2024, 4, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagib, D. A. Asymmetric catalysis in radical chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 15989–15992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northrup, A. B.; MacMillan, D. W. C. The first general enantioselective catalytic Diels-Alder reaction with simple α,β-unsaturated ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2458–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelais, G.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Modern strategies in organic catalysis: The advent and development of iminium activation. Aldriquimica Acta 2006, 39, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Erkkilä, A.; Majander, I.; Pihko, P. M. Iminium catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5416–5470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, G.; Melchiorre, P. A novel organocatalytic tool for the iminium activation of α,β-unsaturated ketones. Synlett 2008, 2008(12), 1759–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paras, N. A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. The enantioselective organocatalytic 1,4-Addition of electron-rich benzenes to α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 7894–7895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronina, Y.A.; Teglyai, L. A.; Ponyaev, A. I.; Petrov, M. L.; Boitsov, V. M.; Stepakow, A. V. Organocatalysis in 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions (A review). Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2024, 94, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, N.; Takenaka, N.; Najwa, A.; Takahara, Y.; Mun, M. K.; Itsuno, S. Synthesis of main-chain ionic polymers of chiral imidazolidinone organocatalysts and their application to asymmetric Diels–Alder reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 2018(1), 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

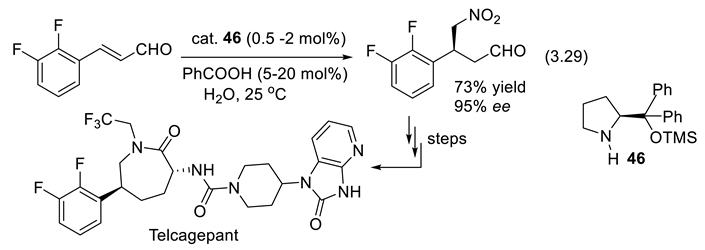

- Xu, F.; Zacuto, M.; Yoshikawa, N.; Desmond, R.; Hoerrner, S.; Itoh, T.; Journet, M.; Humphrey, G. R.; Cowden, C.; Strotman, N.; Devine, P. Asymmetric synthesis of telcagepant, a CGRP receptor antagonist for the treatment of migraine. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75(22), 7829–7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z. Y.; Ghosh, T.; Melchiorre, P. Enantioselective radical conjugate additions driven by a photoactive intramolecular iminium-ion-based EDA complex. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

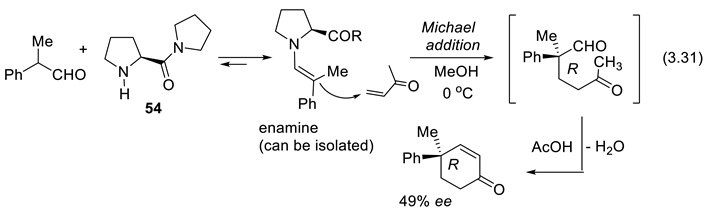

- Mukherjee, S.; Yang, J. W.; Hoffmann, S.; List, B. Asymmetric enamine catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5471–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burés, J.; Armstrong, A.; Blackmond, D. G. Explaining anomalies in enamine catalysis: “downstream species” as a new paradigm for stereocontrol. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, K.; Notz, W.; Bui, T.; Barbas, C. F. III. Amino acid catalyzed direct asymmetric aldol reactions: a bioorganic approach to catalytic asymmetric carbon-carbon bond-forming reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 5260–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. K. Efficient catalytic methods for asymmetric cross-aldol reaction of aldehydes. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

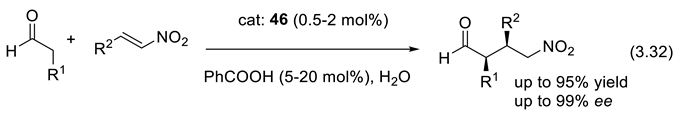

- Hayashi, Y.; Gotoh, H.; Hayashi, T.; Shoji, M. Diphenylprolinolsilyl ethers as efficient organocatalysts for the asymmetric Michael reaction of aldehydes and nitroalkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4212–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Zahoor, A. F.; Ahmad, S.; Akhtar, R.; Qurban, W.; Mehreen, A. Recent trends in the development of novel catalysts for asymmetric Michael reaction. Curr. Org. Chem. 2020, 24, 1397–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasuparthy, S. D.; Maiti, B. Enantioselective organocatalytic Michael addition reactions catalyzed by proline/prolinol/supported proline based organocatalysts: An overview. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova, A. The direct catalytic asymmetric Mannich reaction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, A.; Schaus, S. E. Organocatalytic asymmetric Mannich reactions: New methodology, catalyst design, and synthetic applications. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, (35), 5797–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notz, W.; Tanaka, F.; Barbas, C. F. Enamine-based organocatalysis with proline and diamines: The development of direct catalytic asymmetric aldol, Mannich, Michael, and Diels-Alder reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]