1. Introduction

This study has been prepared in order to be included in the special issue of “Minerals” entitled “Understanding Tectonic Evolution: From Deformed Grains to Tectonic Plates”. Our aim is to link the Neoproterozoic rift located in the Congo craton and particularly the Itombwe basin which is a master piece of this “Neoproterozoic rift” (

Figure 1) with the coevals surrounding “Panafrican” belts such as the Lufilian and Zambian belts to the South and the Mozambique and Madagascar belts to the East. The Pan-African orogen which succeeded to the Kibaran orogen and led to the assembly of Western Gondwana between 950 and 500 Ma suffers several tectonothermal events which have impacted this Neoproterozoic rift. Geochronological and geological data show that this ancient rift and surrounding belts are strongly dependent. Tectonic constraints were transmitted to the rift structures and their surroundings basement both by local folding and large transversal transcurrent shear-zone.

2. Geological Framework

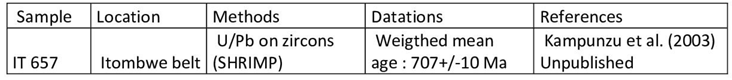

The CC (Congo Craton) in place at the end of the Mesoproterozoic, is gathering the Congo shield, the Tanzania block and the Bangweulu block reunited by the Kibaran belts (

Figure 1)

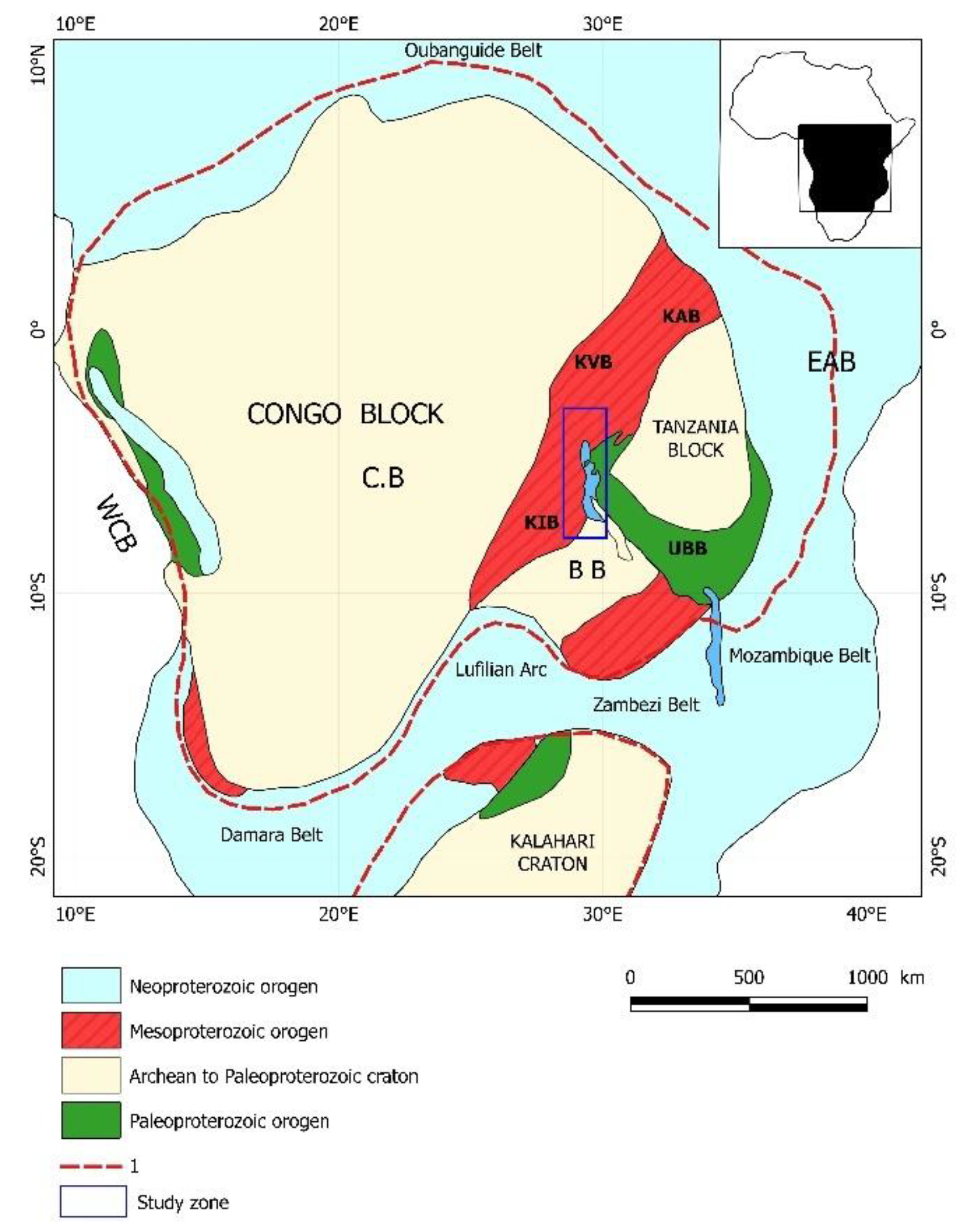

It is surrounded by several Pan-African belts and particularly the Mozambique belt to the East and Zambian and Lufilian (or Katangan) belts to the south. However, inside the CC, between the Congo and Tanzanian blocks, several structures linked to the Pan-African belts crops out within the Mesoproterozoic Kibaran belt, close to the present African rift and alongside the great African lakes. These internal structures constitute the Neoproterozoic rift which is the topic of the present paper. These structures constitute the so called “Central African Neoproterozoic rift”. The Geology of this Central Africa area can be divided in two parts: the basement (Archean to Mesoproterozoic) and the post-Mesoproterozoic events including three different geological events: I-the Panafrican orogen, including the cambered zone with anorogenic complex, the Neoproterozoic rifting with opening and closure of throughs, II-the Karoo event with deposition of the carboniferous tillites and associated Permian and Triassic deposits, III- the East African rift with its associated volcanic outpouring (Tertiary to Quaternary).

These post-Kibaran events are exposed in

Figure 2. Our study only is only devoted to the Pan-African orogen.

The basement of this central African area is mainly composed by the Kibaran belts recently synthesized by [

2,

3]. According to [

2] the Kibaran orogen includes five different stages (K1 to K5) between 1600 and 950 Ma. Older units belonging to the Archean or Paleoproterozoic are the Kibalian (Northern Kivu), the Ruzizian (Southern Kivu and Rwanda and Burundi) and the Tanzanian basement (Tanzania and Uganda). The younger Kibaran stage (1100 to 950 Ma) corresponds to the post tectonic granitic intrusions (G4 granites) which provide the main occurrences of Tin and Coltan minerals. By contrast, the post-Kibaran events excepted the modern rift and associated deposits, are less known. The topic of this paper is to enhance our knowledge on the post Kibaran events comprises between the last intrusive Kibaran stage (1000 -950 Ma) and the last Pan-African tectonic events (550-500Ma). In the contrary of the surrounding areas exhibiting large belts linked to the plate tectonic orogens (Mozambique, Madagascar, Zambian and Lufilian belts), our studied zone only presents rare structures coming from an ancient rift and folded by a field effect of the surrounding belts. This Neoproterozoic rift corresponds to several troughs unfilled during the late Neoproterozoic and folded at the end of the Neoproterozoic and the beginning of Cambrian, during the last Panafrican stages. Between the surrounding Pan-African belts and the Neoproterozoic rift structures, some of the Kibaran belts are locally remobilized by tectonic or metamorphic effects but also along the transverse faults which play an important role in the tectonic transfers from the Pan-Aafrican belts to the central rift structures. This Pan-African orogen which succeed to the Kibaran orogen is bracketed between 950 and 500 Ma.

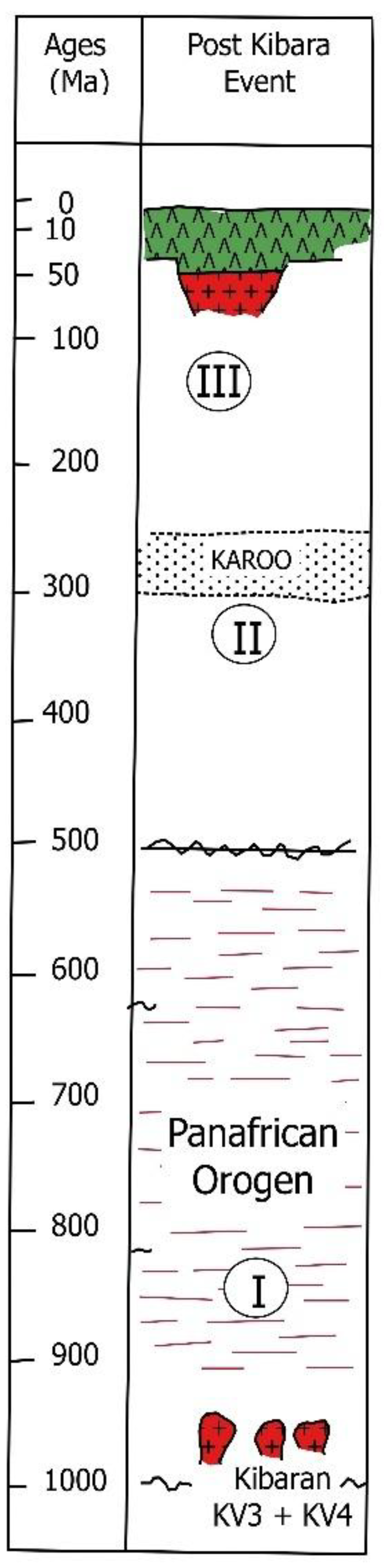

3. TheNeoproterozoic Rift System in Africa

The Neoproterozoic rifting consists in several elongated N-S structures setting in the vicinity of the Great African Lakes (

Figure 3) similarly to the present Eastern African rift. This similarity has been underlined by several authors following Dixey [

4].The main structures ascribed to this Neoproterozoic rift are: the Itombwe belt [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], the Irumu belt [

14,

15] and the Bunyoro belt [

16,

17]. However, other tillitic formations (Haute Ibina, Gety, etc.) have been associated to this Neoproterozoic rifting.

Between the last Kibaran stage (Kb5, 1100 -950 Ma) and the end of the Pan-African orogen (500 Ma) five stages have been distinguished: P1 (950-850 Ma), P2- (850-700 Ma), P3- (650- 620 Ma), P4 (620-550 Ma) and P5 (550-500Ma). Concerning the Neoproterozoic rift, three periods are considered: ante-rifting, rifting and post rifting.

3.1. Ante Rifting (Stages P1 and P2)

Stage P1 corresponds to the deposition of the Mwasha fm (Roan super-group) were no intrusive or tectonic activity has been recorded and stage P2 with an N S cambered zone parallel to the Great Lakes zone followedby a period of E-W extension given rise to anorogenic intrusions (

Figure 3). These anorogenic intrusions (granites, syenites and carbonatites) occurred between 800 Ma and 700 Ma (

Table 1). Younger than the posts tectonic granites, there are thirteen alkaline and carbonatitic complexes mainly located on the Western Kivu Lake shoreline. Three types of intrusive complexes have been evidenced by Kampunzu et al. [

18]: 1-undersatured silicate rocks and carbonatites (Bingo, Lueshe, Kirumba and Numbi); 2- Oversatured and undersatured with carbonatites (Upper Ruvubu complex in Burundi) and (3) Silica-oversatured rocks (Kahuzi and Biega massifs).

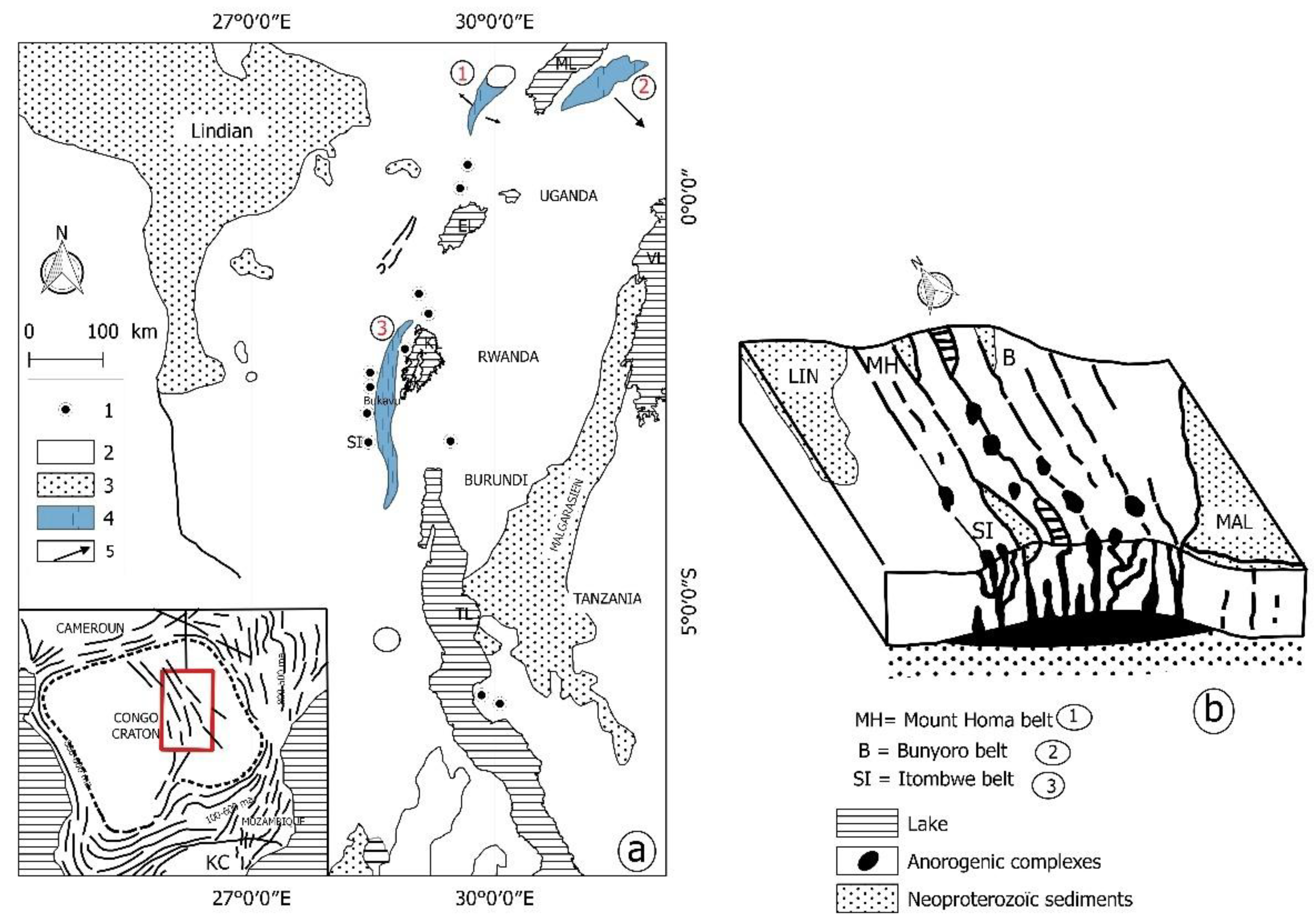

Table 1 provide some U-Pb ages on zircons from seven anorogenic intrusions.

These radiometric ages are in the bracket 850 to 705 Ma and correspond to the age of detrital zircons recorded by in the Nya-Ngezie formations belonging to the basement of the Itombwe structure [

2]. These detrital zircons have been ascribed to the surrounding anorogenic complexes. Out of the Kivu area is there adeposition of sediments in the Neoproterozoic covers (Lindien and Bukoban-Malagarasien) intruded by dolerites dated between 820+/- 30 Ma and 810+/-25 Ma [

24,

25]. Mafic igneous rocks in the Bukoban-Malagarasi Supergroup yielded Ar-Ar ages of 795+/-7 Ma [

26]. These undeformed covers are coeval with the anorogenic intrusions.

3.2. Rifting

The rifting stage corresponds to the opening of the troughs according to the age of the first deposits. However, without fossils and chronological data, this age of deposits is confusing and depending of correlations with adjacent area. The stratigraphic sequence in the Irumu through (half graben) start with green sericitoshistes (Luma fm) covered by a succession of sandstones, shale sans tillitic levels (Loyo fm). These two formations, folded and slightly metamorphosed are capped by the flat Mt Homa formation with dolomites, shales and conglomerate itself covered by the Lukuga formation belonging to the Karoo system (Permian and Trias). The tillitic levels have been correlated to the Akwokwo setting at the base of Lindian (950 Ma) by Sluys [

15] and Lepersonne [

14] the only one known at that time, but these glacial sediments with their surrounding equivalents (Gety tillite, Mont Nongo and Eholu conglomerates) could also be correlated to the Marinhoan glacial event (650-635 Ma) now well-known over the Africa. The symmetrical Bunyoro series evidenced by Davies [

16] were studied by Bjorlykke [

17]. These series also folded are composed of shales and tillitic levels with “drop stones’ deposited between 650 Ma and the beginning of Cambrian after Bjorlykke.

3.3. Post Rifting

Taking into account that theses intra rift deposits are folded and slightly metamorphosed the post rift period is obviously linked to the age of this tectono-metamorphic event ascribed to the last Pan-African events. But no relevant geochronological data allow us to know the true age of these events. However, the datations on the Itombwe structure bring these informations.

4. The Itombwe Belt

4.1. History

The southern part of the Itombwe syncline was evidenced since 1946 [

27] at Luemba (South Kivu) by a disconformity but it was ascribed to the upper Burundian (Late Neoproterozoic). Later on, this disconformity has been evidenced close to Bukavu by Villeneuve [5, 6and 7]. But the ascribing to Pan-African was later on [28, 10 and 11]. New geochronological data [29, 13 and 3] allow us to date its opening and closure.

4.2. Structure

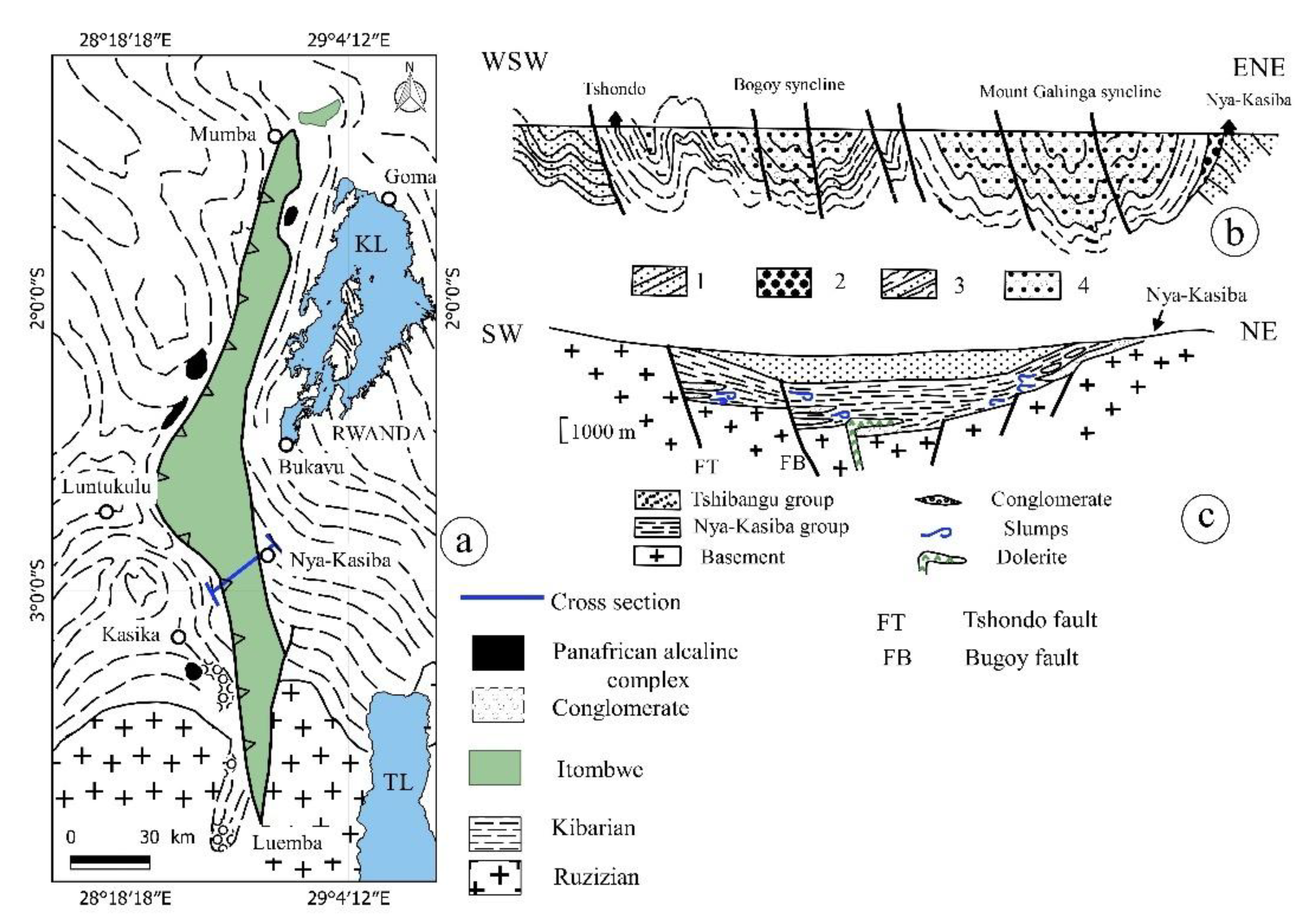

According to the

Figure 4, the main elements of this Itombwe structure are a NS elongated belt which extends from the North of the Tanganyika Lake to the North of the Kivu Lake with only 20 km wide (

Figure 4a).

Figure 4b exposes an E-W cross section which is interpreted in

Figure 4c as a graben with an active normal fault to the West.

4.3. Evolution

This evolution consists in three different stages: I-pre-opening, II-opening and infilling and III-closure of the graben by folding of sediments.

4.3.1. Pre-Opening

The occurrence of several anorogenic intrusions on both sides of this Itombwe belts which are dated between 820 and 705 Ma. (

Table 1) could be linked to cycle P2 above mentioned.

4.3.2. Opening and Infilling

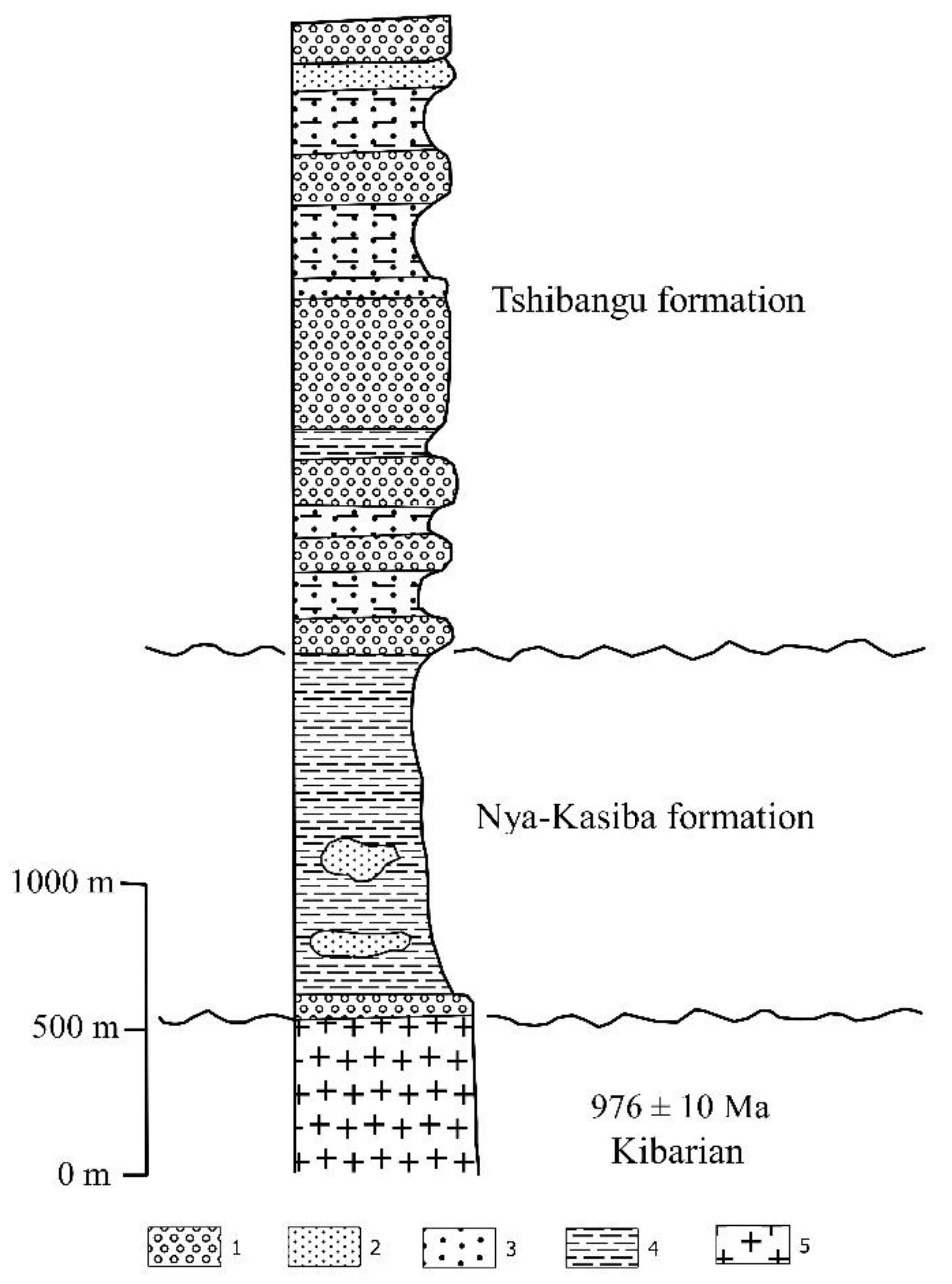

The stratigraphic succession (

Figure 5) shows two superimposed formations: Nya-Kasiba to the base and Tshibangu on top.

The Nya-Kasiba formation consists in shales with a conglomerate at the base and the Tshibangu formation corresponds to a succession of black shales interbedded with tillitic levels. The presence of clasts of tin granites (1-0.95 Ma) in the basal conglomerate allow us to establish the post Mesoproterozoic age of this basin. But, 36 detrital zircons from the basal conglomerate of the Kasiba formation have been dated by U/Pb by Kampunzu et al., [

29] in the sample IT657. This sample provides ages in the range 777-662 Ma and a weighed mean age at 707+/-10 Ma. The maximum depositional age in this basal conglomerate is less than 662 Ma.

Table 2.

Mean age of zircons in sample IT 657 from the basal conglomerate of the Nya-Kasiba formation (Itombwe super group) [

29].

Table 2.

Mean age of zircons in sample IT 657 from the basal conglomerate of the Nya-Kasiba formation (Itombwe super group) [

29].

A minimal age for deposition is given by the Ar/Ar ages of hydrothermal muscovites from the Twangiza pyrite – arsenopyrite bearing ore deposits yield ages between 629+/-7 and 608+/-9 Ma [

30]. Other clusters of ages on detrital zircons have been recorded in this IT 657 sample: 2700-2600, 2000-1900, 1200-900,800-650 Ma which corresponds to the ages of the basement [

29]. Similar age clusters have been evidenced in the Nya-Ngezie group [

2] which is the basement of the Itombwe structure, with exception for the group 800-650 Ma. This is favouring a local provenance for the zircons dated in sample IT 657. However, the lack of detrital zircons in the range 900-800 Ma is noteworthy. This gap corresponds to a magmatic gap in the country. Thus, the opening post 662 Ma could explain the lack of Sturtian glacial (717-660 Ma) deposits and the deposition of Marinhoan glacial (650-635 Ma) sediments (Itombwe tillite).

4.3.3. Closure and Folding

Taking into account that there is no local plate tectonic event the closure and folding of these Neoproterozoic to early Cambrian structures is linked to the Pan-African orogeny that occurred around the central African Craton, in surrounding Pan-African belts. Panafrican ages are also recorded in the Archean or Kibarian basement. These Pan-African deformations are well studied both in the Itombwe trough and in the eastern neighbouring basement.

-In the Itombwe trough.

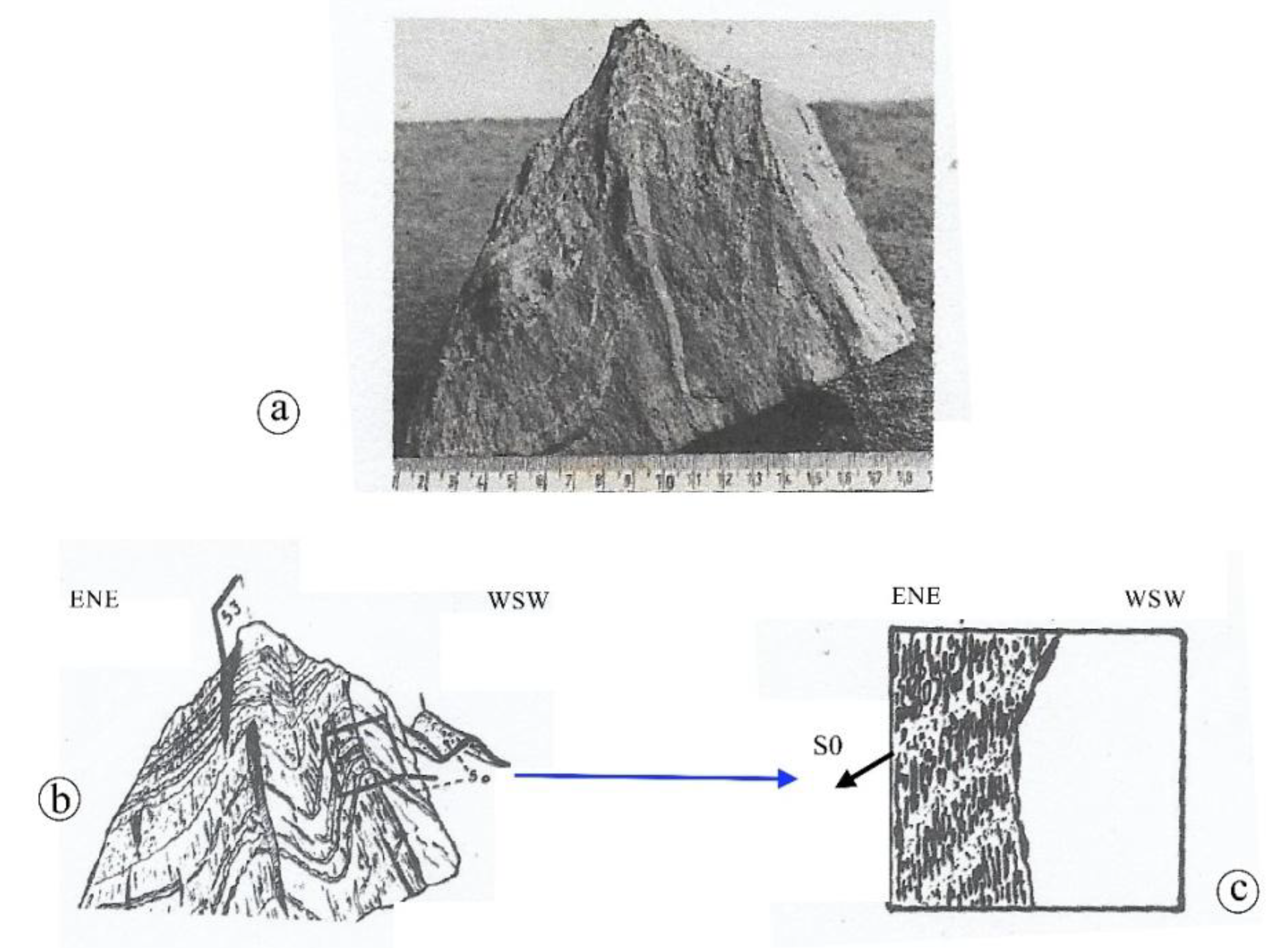

The tectonic imprint, in the Itombwe structure, is evidenced by the deep of the stratification and by a vertical shistosity. However, some isoclinal folds are observed at different scales: at a regional scale (

Figure 4b) and on hand samples (

Figure 6a). The shistosity is parallel to the fold axial plane (

Figure 6b) and is materialised by biotites (

Figure 6c). The orientation of axial plane of folds and shistosity are mainly N-S to WSW-ENE. No reworking of this fold have been observed in the Itombwe formations indicating that those folding phase is the last one in thiscentral Africa area.

Age of this tectonic folding is provided directly by the datations on biotites and muscovites as witness of a low-grade metamorphism

-In the basement.

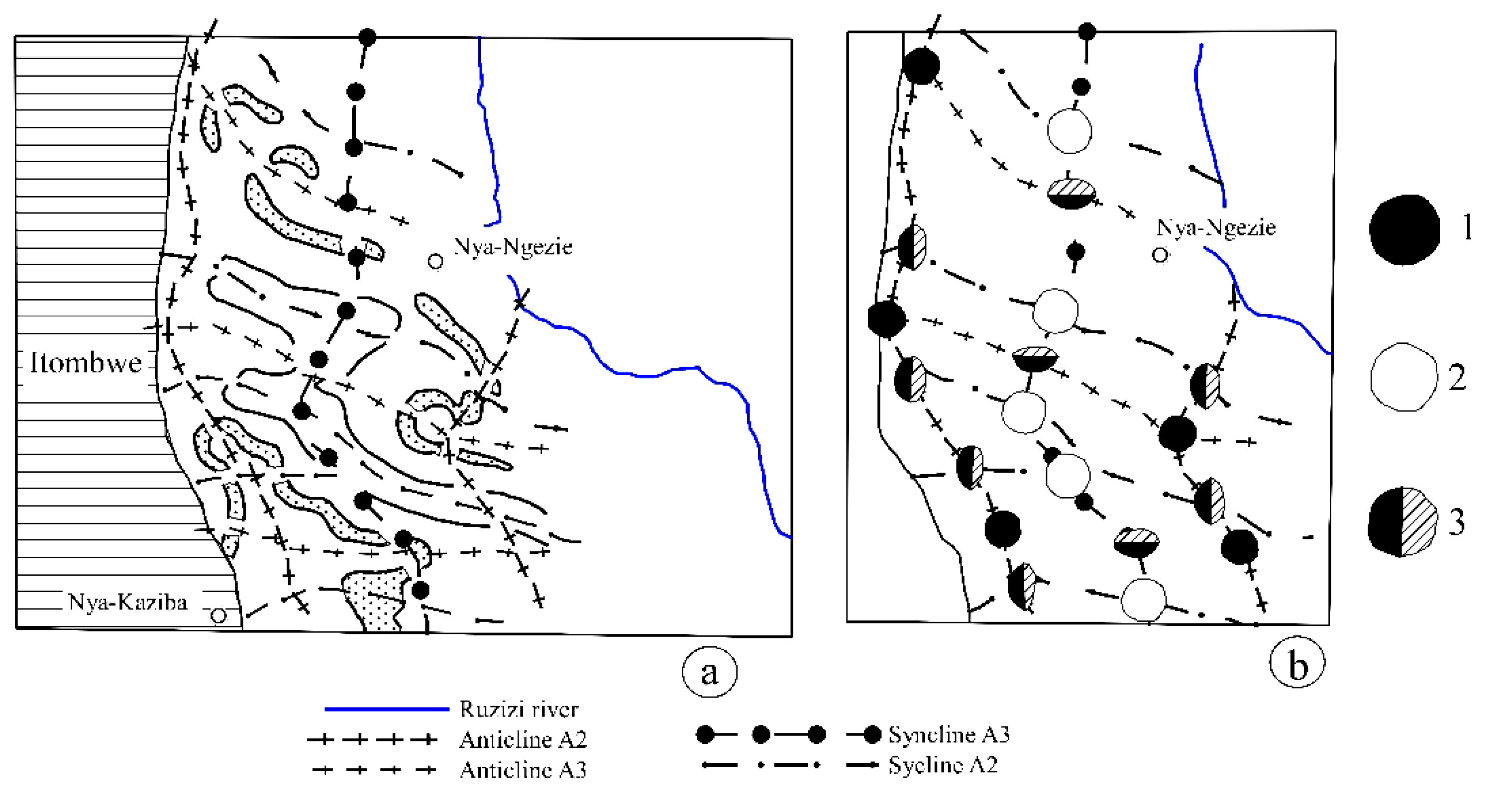

The Kibaran basement located on the Eastern side of the Itombwe structure has been carefully studied in the Nya-Ngezie area located to the south of the Kivu Lake (

Figure 7) by Villeneuve [

6]. In this area the Kibaran basement belong to the cycle K5 of the Kibaran Orogen [

2].

The NW-SE regional structures (anticlines and synclines) are ascribed to the last Kibaran event (A2) meanwhile se superimposed N-S (A3) structures are ascribed to the Itombwe tectonic event. The interpretation of this superimposition is shown in

Figure 7b. But in this regional scale, the Kibaran structures A2are little deformed by the Itombwe structures A3 as it is shown in

Figure 8 which is a 3D interpretation of the Kibaran structures presented in

Figure 7a.

This reworking is dated by Ar/Ar method on biotites from the rocks (C166 and 766) belonging to the cycle 4 of the Kibaran orogeny. These datations on micashists and quartz–micaschists provides 2 plateau-ages respectively 573.2+/-1.6 Ma and 546.3 +/-1.7 Ma [

3] indicating a Panafrican reworking. Similar Pan-African ages have been recorded in granitic intrusions recorded in the Kibaran basement.

Table 3 shown some examples of this Panafrican reworking.

The best example of this Pan-African reworking is the Kasika granite to the West of the Itombwe trough and which is linked post Kibaran intrusion dated at 986+/- 10 Ma by Tack et al. [

32] with U/Pb on zircons and yielded an age between 549+/- 7 Ma and 513+/- 8 Ma on muscovites by Walemba [

33] and 520+/- 9 Ma with Rb/Sr on microcline by Monteyne-Poulaert [

30]. Another example is given by the Kahusi and Biega massifs considered as a part of the tertiary volcanic outpouring linked to the East African rift and which are yielded ages between 440 and 505 Ma for the Kahuzi by Ar/K on whole rocks [

21] and 825.2 +/-5 Ma 808+/-6 Ma with U/Pb on zircons [

34]. Such reworking is common in this area as well as in Rwanda as in Burundi. For example, Van Deale and Sherer [

35] yield ages of 602.3 Ma+/-1.1 Ma and 618.9+/-1.6 Ma with Lu-Hf on grenats –micaschists close to Kibuye, in Rwanda. Taking into account the discrepancies induced by the different radiometric methods, we are considering two stages of deformations: first in Rwanda (618-602 Ma) and the second one related to the Itombwe folding (546-513 Ma).

4.3.4. Post Rifting

There is no direct evidence of post rifting data on the Itombwe belt. But considering reworking of the the Kahuzi and Biega, located in the western side of the Itombwe by the late Ediacarian-Early Cambrian (452-442+/-11 Ma,) [

21], we are considering this extensional event as the post-rift stage of this Neoproterozoic rifting.

4.3.5. Origin of Orogenic Driving Force and Tectonic Transfer

Considering that there is no driving force in the studied area, we should have a look to the neighbouring belts in order to locate this active tectonic zone and also understand how these local tectonic activities have been transmitted from these active zones located at least 500km far away from our studied zone. These active tectonic zones were obviously located in the surrounding Pana-African belts. The central African belts concerned here are located between the Congo Craton (CC) including the Tanzanian Shield (TS), the Dharwar Craton (DC), the Rhodesian Shield (RS) and the northern part of the Kalahari Craton (

Figure 9).

These belts are: the East African belt (EAS) to the East and the Katangan belts (Luf) and Zambezi-Kuungan belt to the South.

The tectonic activities were likely transmitted either by superimposition of new deformations onto the old basement either by tectonic transfers along the strike-slip zones or by a combination of both processes.

5. The Pan-African structures in Eastern Africa

5.1. Pan-African Belts

5.1.1. East African Belt

The East African belts which run from the Arabia to the Mozambique includes several segments: Egypt-Arabia, Ethiopian-Tanzanian and Madagascar-Mozambique only the last one could interest the Kivu Area.

5.1.1-The Madagascar-Mozambique segment.

The Mozambique belt is made with Kibaran basement terranes reworked during the Pan-African orogeny [

36,

37]. Shackleton [

38] takes into account an internal anomaly in the Mozambique belt as the suture between the western and eastern Gondwana. According to Fitzsimons and Hulscher [

39] the main steps of the geodynamical evolution are:

- 850 Ma two different oceans separated the Great Congo Craton (Tanzanian block and Irumide belt), the Itremo block and the Darwar craton

- 750 Ma. Both oceans subducted to the West given rise to two volcanic arcs.

- 650 Ma the Itremo and Darwar blocks collided meanwhile the subduction underneath the between the Itremo Block and the Congo Craton was still active. However the corresponding slab had a vergence to the West according to Fitzsimons and Hulscher [

39] meanwhile Cutten et al [

40] support a vergence to the East with Granulitic massifs obducted to the Congo craton (Tanzanian Block). The thrusting of “nappes” is clearly to the West.

- 550 Ma the three blocks (Dharwar, Itremo and Congo) are grouped by collision of the two last blocks.

-530 to 480 Ma. This last stage considered as a post tectonic extensible event could be linked to the E-W Kuungan collision [

41]. But Goscombe et al. [

41] consider only one block facing the Congo Craton: the Azania Block (AZ) which collided the Congo craton during the Adamastor/Mozambique phase (660-640 Ma). Taking into account the radiometric ages of the thermo-tectonic events delivered by twelve different authors (

Figure 10), three main different tectonothermal events are considered: 1-(580 -630 Ma), 2- (560-520 Ma), 3-(500 Ma). However, four radiometric datations between 700 and 850 Ma have also been recorded. Despite large discrepancies owing to the different radiometric methods, these ages seem to be coherent with the events in adjacent belts.

5.1.2. The Katangan Belt (or Lufilian Belt)

This belt includes two main stratigraphic sections: the Roan super-group (870-880 Ma to 735Ma) studied by Unrug [

49] and the Kundelungu super-group (735-575 Ma) divided in Lower and Upper Kundelungu group. The Lower beginning by the “Grand conglomerat” (Sturtian glacial event, 717-660 Ma) and the Upper includes the “Petit conglomerat” linked to the Marinhoan Glacial event (650 -635 Ma). This Katangan Belt was folded many times between the 760 Ma tectonic events and the Lufilian tectonic event (650-620 Ma). According to Cahen [

50], l’uranite du Shaba dated at 620 Ma post-date the Katangan orogenic event, but according to Kipita et al. [

51] the paroxysm of the Lufulian orogeny is dated at about 550 Ma. However, according to Unrug [

52] a last tectonic event occurred between 480 and 500 Ma. However,

Figure 9 and Unrug [

49] suggest a Lufilian arc reworked by sinistral strike-slip along the Mwenbeshi Fault Zone.

5.1.3. Zambezi-Kuungan Belt

According to Hanson et al. [

53] the Zambien belt located between the Bangweulu Block and the Zimbabwe craton is cutted by the WSW-ENE Mwenbeshi Fault. The basement is intruded by Kibaran granites (1100 to 1106 Ma) and granitic complexes at ca.880 and 820 Ma. The last tectonic events occurred between 590 to 530 Ma together with the Mwenbeshi Fault activity [

53]. However, according to Goscombe et al. [

41] the geological evolution of this Zambezi-Kuunga block is more complex. They consider an oceanic plate separating the Kalahari and Congo cratons until the collision of both cratons. This collisional process could be separated in two phases: the Kaokoan/Zambezi Phase (590-570 Ma) which involve the eastern Luiro, Zambezi and Lufilian belts and the Damaran/Kuunga Phase (555-515 Ma) which involve the western Damara and Gariep belts. Thus, the limit between the northern Katangan, Muva and West Zambia belts and the southern Nampula and West Zambezi blocks, is the E-W “Kuunga suture”.

5.2. Pan-African Transcurrent Shears Zones

Several fault zones perpendicular or with an “oblique angle” with respect to the belts have been evidenced but the main one are (

Figure 9): The Aswa FZ (ASFZ) to the North, The Rukwa FZ (RKFZ) in the middle and the Mwembezi FZ (MBFZ) to the South; Obviously, they are operating at many times depending of the surrounding tectonic events but these events are very poorly dated.

5.2.1. Aswa FZ (ASFZ)

The ASWA fault zone which separate the Mozambique belt from the Northern Pan-African belts ( From Sudan to Arabia) has been well studied at many times: Chorowicz et al. [

54] and [

55], Fernandez-Alonso et al. [

56], Saalman et, al. [

57]. According to Saalman et, al. [

57], the main events recorded by U-Pb on zircons yielded two main ages for sinistral strike-slip: 686 and 640 Ma. Chorowicz et al. [

54] recorded 2 ages: 660 Ma and 685-655 Ma

5.2.2. Rukwa FZ (RKFZ)

The NW-SE Rukwa Fault Zone located between the Tanzanian craton and the Bangwelu block is setting within the Ubendian (Paleoproterozoic) basement. It was active at many times: by the Kibaran orogen (Wakole terrane), by the Neoproterozoic at ca. 724+/-6 Ma [58) and at 601+/-7 Ma and 596+/-41 Ma [

58,

59,

60].

5.2.3. Mwenbezi FZ

The Mwenbeshi Fault zone located between the Bangweulu block and the Kalahari Craton. Well studied by Daly [

61].The last tectonic events occurred between 590 to 530 Ma [

53].

5.2.4. Other FZ

Obviously, similar faults with strike-slip motions have been evidenced like the Chongwa Fault Zone which I associated to the Mwenbezi FZ.

5.2.5. Radiometric Data

The main radiometric data ascribed to the tectonic events linked to these shear zone, are shown in

Figure 11.

This figure shown that that the main tectonic events recorded by radiometric methods are comprised between 800 and 400 Ma with two concentrations at 700Ma and 600 Ma. One of these events could be linked to the reworking of the Lufilian arc.

The tectonic events linked to the Cainozoic to Quaternary East African Rift have not been recorded in radiometric data

6. Geodynamic Interpretations of the Itombwe and Related Structures

Obviously, several models have been proposed to explain this Itombwe trough. Chorowicz et al. [

65] proposed to link the structures of the Neoproterozoic rift to a large SW-NE sinistral fault running from the Katanga to the Uganda. This strike-slip system which was associated to a parallel dextral strike-slip system in the western side of the Congo basin was used to explain the structure of this basin. (

Figure 12).

On the other hand, Kampunzu et al [

29] have proposed an opening of the N-S Itombwe through in relation with the E-W Lufilian belt similarly to the Cainozoic N-S Baikal rift which is associated to the E-W Himalaya belt. However, if the age of the opening (662 Ma) and folding of the Itombwe trough (562 Ma) are consistent with the Kampunzu et al. [

29] ‘hypothesis, it must be compared with the present data. Although the lack of a Sturtian glacial event in the Itombwe is consistent with an opening later than 660 Ma, the occurrence of Marinhoan deposits (650-635 Ma) are older than the main tectonic event in the Lufilian arc (602 Ma). So, the Lufilian belt could not be responsible for the Itombwe opening. In the present status of knowledge, we ascribe the Itombwe through opening to a dextral strike-slip displacement along the Rukwa-Fault Zone which is located in the southern part of the Itombwe. In taking in consideration that the fold axis in the Itombwe are N-S similarly to those of the East African belts we are ascribing the closure of this Itombwe trough to the East Pan-African belts. In our hypothesis, the tectonic folding in the Itombwe trough has been transmitted by the East African belt, partly by tectonic transfer along this Rukwa-Fault zone and partly by deformation of the basement.

7. Examples of Similar Structures

Several rifts around the world can be compared to this Neoproterozoic rift but the best “analogs” are: the West European rift, the East African rift and the central Asian rift (Baikal Rift)

6.1. West European Rift

The West European rift which is crossing the West Europe in an N-S direction. It extends from the North Africa to the North Sea. Transverse faults are also evidenced like the E-W transform fault separating the Saone and the Rhenan troughs. These troughs have been opened during the Lower Oligocene before the opening of the West Mediterranean sea. Some of them have been folded by the adjacent Alpine belt likely by far-field tectonic effects similarly to our central African Neoproterozoic rift.

6.2. East African Rift

The present East African rift has already been compared to our Neoproterozoic rift by Villeneuve [

28] in taking into account that the western branch of this Cenozoic to Quaternary rift has partly re-used the Neoproterozoic structures. This Cenozoic to Quaternary rift could be linked to Cenozoic Middle East belts.

6.3. The Central Asian Rift

This central Asian rift which is running across the Siberia in an N-S extension has been linked to the E-W Himalayan belt. The comparison between the East African and the central Asian rift has already been discussed in Kampunzu et al. [

29].

8. Discussion

This discussion intends to understand the evolution of this part of Africa during the Panafrican orogeny mainly in the Neoproterozoic. We also have in purpose to provide some paths for next researchs.

8.1. Geodynamic Evolution the Neoproterozoic in Central and Eastern Africa

In paragraph 3 five stages of evolution have been distinguished: P1 (950-850 Ma), P2- (850-700 Ma), P3- (650- 620 Ma), P4 (620-550 Ma) and P5 (550-500Ma). But only three main stages are illustrated in

Figure 13: the precollisional stage P2 (

Figure 13a), the collisional stage P4 (

Figure 13b) and the post collisional stage (stage P5) in the Mozambique belt, (

Figure 13c) which also correspond to the collision with the southern blocks at the end of the Kuunga orogeny.

However, there are some Kibarian inherited structures related to this Neoproterozoic rift. For example, the K4 Kibaran stage (1120-1020 Ma) which consist in a narrow N-S trough parallel to the Itombwe and setting between the Kivu Lake and the Itombwe trough, could be an ancestor of the Itombwe trough. These N-S Kibarian structures may have guided the Pan-African troughs.

These main stages are:

-

Stage P1: (950-850 Ma) this is a quiet period in the Kivu area (Lack of zircons between 900 to 800 Ma) which corresponds to an extensive period with Oceans between the main future Panafrican blocks, the deposition of the Roan super-group in Katanga and likely to the doming of the Kivu lake area (

Figure 3b)

-Stage P2. (850-700 Ma) Intrusions of anorogenic magmatic rocks by extensive relaxation in the doming area and deposition of the Lindian and Malagarasian covers in both sides of the Kivu Lake area.

-Stage P3- (650- 620 Ma): a stage giving rise to the main collisional events in the East Panafrican belts, to tectonic event in the Lufilian belt which could be the result of a strike –slip displacement along the Mwenbeshi fault zone and likely provided the opening of the Itombwe trough.

Stage P4 (620-550 Ma). Last tectonic events in the Mozambique belts with the collision between the Itremo block and Congo craton. This tectonic event provides the folding of the Itombwe trough and other associate rifting troughs. We are also supposing that this tectonic event could have again deformed the Lufilian belt.

Stage P5(550- 500Ma). Corresponds to the N-S collision between the Congo craton and the newly accreted terranes with the Kalahari craton and Nampula block (

Figure 9 and 13c). This collision which followed the subduction of the Khomas Ocean below the Congo Craton provides an E-W relaxation with extensive deformations in the studied area including the reworking of the Kahuzi and Biega massifs by the early Cambrian (456 and 446 Ma).

8.2. Next Researchs

Our interpretation of the geodynamic evolution of this central African area deserve to be developed noticeably by land studies on reworking of the basement, by new studies on the role of the transcurrent faults and by new radiometric datations given a more precise period for the main tectonic events. That could explain why the sediments deposited in the Neoproterozoic rift were folded meanwhile coeval sediments in the Lindian and Malgarasian covers are flat.

9. Conclusions

There is a big challenge to understand how the Pan-African belts in central and East Africa are acting through times from the Neoproterozoic to the Cambrian. But the second challenge was to connect the non-active coeval structures with the active Pan-African belts. The aim of our study is to understand the process the tectonic transfer of active deformations from the belts resulting from a Wilson cycle, to the far away coeval passive structures. Our study implying microscopic thin sections, regional field observations and local plate tectonic knowledge answer to the demand of this “Minerals” special issue. Despite a lack of extensive observations between the Central African Neoproterozoic rift and the surrounding Panafrican belts we are proposing a process of tectonic transfer involving the oblique transcurrent faults together with an history of the evolution of the central and East Africa since the end of the Mesoproterozoic Kibaran orogens (950 Ma) to the end of the Neoproterozoic to Cambrian Panafrican orogen (510 Ma).

References

- Villeneuve M., Gartner A., Kalikone C., Wazi.N. Amalgamation in the Central African Shield (CAS) by the Kibaran orogen : new hypothesis and implications for the Rodinia assembly. J Afr.Earth Sci., 2023, 202,1-10.

- Villeneuve M., Gärtner A., Kalikone C., Wazi N., Hofmann M., Linnemann U. U-Pb Ages and Provenance of Detrital Zircon from Metasedimentary Rocks of the Nya-Ngezie and Bugarama Groups (D.R. Congo): A Key for the Evolution of the Mesoproterozoic Kibaran-Burundian Orogen in Central Africa. Prec. Res. 2019, 328, 81–98.

- Delvaux D., Kalikone-Buzera C., Ilombe G., Mushamalirwa T.N., Wazi R., Safari E.N., Murhambo.A., Ganza G., Nahimana L., Borst A., François C., Corsini M., Jourdan F., Villeneuve M. Lithiostratigraphic correlations in the Mesoproterozoic Karagwe-Ankole Belt across the Kivu rift segment. A review of the geological evolution and new data from eastern RDC. Prec. Res., (in press).

- Dixey F. The East African rift system. London H.M., Stationary Office Overseas Geol., Miner. Resour. Bull., Supp., 1956, 1,77p.

- Villeneuve M. Mise en évidence d’une discordance angulaire majeure dans les terrains précambriens du Nord du flanc oriental du “synclinal de l’Itombwe” (Zaire). C. R Acad.Sc.,Paris , D, 1976, 282, 1709-1712.

- Villeneuve, M. Le Précambrien du sud du lac Kivu (région du Kivu, République du Zaïre), Etude stratigraphique, pétrographique et structurale. Thèse 3eme cycle. Université Aix Marseille III: Marseille, 1977. 195p.

- Villeneuve M. La stratigraphie du Précambrien au Sud du lac Kivu (Zaïre oriental). Bull. Soc. Geol. Fr., 1978.17, XX, 6, 9l5-920.

- Villeneuve M. La structure du rift africain dans la région du lac Kivu (Zaïre oriental). Bull. Volc. Intern, 1980, 43, 3, 541-551.

- Villeneuve M. Les formations précambriennes antérieures ou rattachées au super groupe de l’Itombwe, au Kivu oriental et méridional (Zaïre). Bull. Soc. Géol. Belgique, 1980, 89,4, 301-308.

- Villeneuve, M. Géologie du synclinal de l’Itombwe (Zaïre oriental) et le problème de l’existence d’un sillon plissé pan-africain. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 1987, 6, 869–880.

- Villeneuve M. The main geological elements of the Kibaran fold belt in the Kivu area (Eastern Zaire). 14th African geological colloquium, Berlin, 1987b, p.61.

- Cahen L., Ledent D., Villeneuve M. Existense d’une chaine plissée Protérozoique supérieur au Kivu Oriental (Zaire). Données geochronologiques relatives au Supergroupe de l’Itombwe. Soc. Belge de Géologie, 1979, 88, 1, 71-73.

- Walemba K.M.A, Master S. Neoproterozoic diamictites from the Itombwe Synclinorium, Kivu province, Democratic Republic of Congo: Paleoclimatic signifiance and regional correlations. J. Afric. Earth Sci., 2005, 42, 200-210.

- Sluys M. La géologie de l’Ituri. Les lambeaux sédimentaires apparaissant dans l’Ituri oriental et sur les plateaux encadrant le lac Albert. Bull. Serv. Geol. C .B et RU. 1946, 2 1. 101-153.

- Lepersonne J., 1969. Etude photogéologique de la région du mont de la Luma et de la Loyo (Congo nord-oriental). Mus. Roy. Afr. Centr. Dpt .Geol.Min. Rapp ann. 1968, 19-26.

- Davies K.A. The glacial sediments of Bunyoro, N.W. Uganda. Bull. Geol. Surv. Uganda, 1939, 3, 29-37.

- Bjorlykke K. Glacial conglomerates of Late Precambrian age from the Bunyoro séries, W. Uganda. Geol. Rdsch. 1973, 62, 183-195.

- Kampunzu A.B., Kramers J.D., Makutu M.N. Rb-Sr whole rocks age of the Lueshe, Kirumba and Numbi igneous complexes (Kivu, DR Congo) and the break-up of the Rodinia supercontinent. J. Afric. Earth Sci., 1998, 26, 1, 29-36.

- Midende, G., Boulvais, P., Tack, L., Melcher, F., Gerdes, A., Dewaele, S., Demaiffe, D., Decree, S. Petrography, geochemistry and U-Pb zircon age of the Matongo carbonatite Massif (Burundi): implication for the Neoproterozoic geodynamic evolution of Central Africa. J. Afr. Earth Sci., 2014. 100, 656–674.

- Akilimali Maheshe, S. Gitologie, métallogénie et exploitation minière artisanale dans le Kivu: Bref aperçu sur les gisements stanniferes. Cah. BEGE-RDC, 2016, 1, 27–32.

- Vellutini, P., Bonhomme, M., Caron, J.P.H., Kampunzu, A.B., Lubala, T. Sur la signification « tectonique » des complexes alcalins acides du Kahuzi et du Biega (Kivu-Zaïre), C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, 1981, 292, 1027-1029.

- Tack, L., De Paepe, P., Deutsch, S., Liégeois, J.P. The alkaline plutonic complex of the Upper Ruvubu (Burundi): geology, age, isotopic geochemistry and implications for the regional geology of the Western rift. In: Klerkx, J., Michot, J. (Eds.), African Geology, 1984, pp. 91–114.

- Rumvegeri B.R., Caron J.P.H., Kampunzu A.B., Lubala R.T., Vellutini P.J. Petrologie et signification geotectonique des plutonites de Kambuzi (Sud Kivu, Zaire). Can. J. Earth Sci. 1985, 22, 304-311.

- Briden J.C., Piper J.D., Henthorn D, I., Rex D.C. New palaeomagnetic results from Africa and related potassium-argon age determinations. In 15th annual Report Research Institute African Geology, University of Leeds, 1971, 46-50.

- Cahen l., Snelling N.L. The geochronology of equatorial Africa. North Holland Publ.Co Amterdam, 1966, 195p.

- Deblond A., Punzalan L.E., Boven A., Tack, L. The Malagarazi Supergroup of Southeast Burundi and Its Correlative Bukoba Supergroup of Northwest Tanzania: Neo- and Mesoproterozoic Chronostratigraphic Constraints from Ar-Ar Ages on Mafic Intrusive Rocks. J. Afr. Earth Sci., 2001, 32, 435–449.

- Lhoest A. Une coupe remarquable des couches de base de l’Urundi dans l’Itombwe (Congo belge). Ann.Soc. geol. Belgique, 1946, 69, 250-256.

- Villeneuve M. Les sillons tectoniques du Précambrien supérieur dans l’Est du Zaïre ; comparaisons avec les directions du rift Est-Africain. Bull. Centres Rech. Explor-Prod, Elf-Aquitaine, 1983, 7, 1,163-174.

- Kampunzu, A.B., Armstrong, R., Chorowicz, J., Villeneuve, M. Geology and detrital zircons from the Precambrian Itombwe supergroup (Congo): implications for the depositional age, provenance and the geotectonic evolution of East African orogen during East-West Gondwana continental collision, Unpublished manuscript, 2003,32p.

- Monteyne-Poulaert, G., Delwiche, R., Safiannikoff, A., Cahen, L. Ages de minéralisations pegmatitiques et filoniennes du Kivu méridional (Congo oriental). Indications préliminaires sur les âges des phases pegmatitiques successives. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, 1962, 71(2), 272-295.

- Cahen, L., Ledent, D., Villeneuve, M. Existence d’une chaine plissée Protérozoïque supérieur au Kivu oriental (Zaïre). Données géochronologiques relatives au Supergroupe de l’Itombwe. Soc. Belge de Géologie, 1979, 88, 1, 71-83.

- Tack L., Wingate M. T. D., De Waele B., Meert J., Belousova E., Griffin A., Tahon A., Fernandez-Alonso M. The emplacement of bimodal magmatism under the extensional regime. Prec. Res., 180, 2010, 63- 84.

- Walemba, K.M.A. Geology, Geochemistry and Tectono-Metallogenic Evolution of the Neoproterozoic Gold Deposits in the Kadubu Area, Kivu, DRC, PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 2001.150p.

- Kalikone-Buzera, C. Contrôle lithostructural de la circulation des fluides minéralisateurs et piégages des composants métalliques transportés dans l’espace transfrontalier du Kivu (Kalehe, Idjwi, Nya-Ngezie et Kamanyola- Rwanda-Burundi. PhD. Thèsis, Université du Burundi, Bujumbura, 2024, 270p.

- Van Deale J., Sherer E.E. Neoproterozoic pre and post deformational metamorphism in the western domain of the Karagwe-Ankole belt reconstructed by Lu-Hf garnet geochronology in the Kibuye-Gatumba area .Rwanda. Prec.Res. 2020, 344.

- Pinna P. On the dual nature of the Mozambique Belt, Mozambique to Kenya. J. Afric.Earth Sci., 1995, 21, 23, 477-480.

- Grantham G.H., Manhica A.D.S.T., Armstrong R.A, Kruger F.J., Loubser M.,.New SHRIMP, Rb/Sr and Sm/Nd isotope and whole rock chemical data from central Mozambique and Western Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica: Implications for the nature of the eastern margin of the Kalahari Craton and the amalgamation of Gondwana. J. Afric. Earth Sci. 2011,59,74-100.

- Shackleton R.M. The final collision zone between East and West Gondwana: Where is it? J. Afric. Earth Sci., 1996, 23, 271-287.

- Fitzsimons I.C.W., Hulscher B. Out of Africa: detrital zircon provenance of central Madagascar and Neoproterozoic terrane transfer across the Mozambique Ocean. Terra Nova, 2005,17, 224-235.

- Cutten H., Johnson S.P., Dewaele B. Protolith Ages and Ttiming of the Metasomatism related to the Formation of Whiteschists at Mauria Hill, Tanzania : implications for the assembly of Gondwana. The journal of Geology, 2006, 114, 6, 683-698.

- Goscombe B., Foster D.A., Gray D., Wade B. Assembly of central Gondwana along the Zambezi Belt : Metamorphic response and basement reactivation during the Kuunga Orogeny. Gondwana Resarch, 2020, 80, 410-465.

- Mosley P.N. Geological evolution of the Late Proterozoic “Mozambique Belt” of Kenya. , Tectonophysics. 1993, 221, 223-250.

- Thomas K, et al. Structural and geochronological constraints on the evolution of the Eastern margin of the Tanzania craton in the Mpwapwa area, central Tanzania, Prec. Res. 2013, 224, 671-689.

- Maboko M.A.H., Boher M., Nakamura E. Neodynium isotopic constraints on the protolith ages of rocks involved in Pan-African tectonism in the Mozambique Belt of Tanzania. J. of Geol. Soc. 1995, 152,1, 93-98.

- Rosseti F., Cozzupoli D.., Phillips D. Compressional reworking of the East African Orogen in the Uluguru Mountains of Eastern Tanzania at c. 550 Ma : implications for the final assembly of Gondwana. Terra Nova, 2008, 20, 1, 59-67.

- Kroner A., Willner A.P., Hegner E., Jeackel P., Nemchin A. Single zircon ages, PT evolution and Nd isotopic systematic high-grade gneisses in southern Malawi and their bearing on the evolution of the Mozambique belt in southeastern Africa. Prec. Res., 2001, 109, 257-291.

- Tenczer V., Hauzenberger C., Wallbrecher C., Fritz H., Muhongo S., Mogessie A., Hoinkes G. Loizinbauer J. Bauernhofer A. New ages from the Mozambique Belt in Central Tanzania. 20éme colloque géologie africaine, Orléans, France, 2004, p 398.

- Vogt M., Kroner A., Poller U., Sommer H., Muhongo S., Wingate M .T.D. Archean and Paleoproterozoic gneisses reworked during a Neoproterozoique (Pan-African) high grade event in the Mozambique belt of East Africa : structural relationships and zircon ages from the Kidatu area, central Tanzania. J. Afr.Earth Sci . 2006, 45, 139-155.

- Unrug R. The Lufilian arc: a microplate in the Pan-African collision zone of the Congo and Kalahari cratons. Prec. Res., 1983, 21, 181-196.

- Cahen L. L’uranite de 620 Ma post-date tout le Katanguien (Mise au point). Rapp. Ann. 1972, Dép Geol. Miner. Musée Roy. Afr. Centr., 1973, 35-38.

- Kipata, M.L., Delvaux, D., Sebagenzi, M.N., Cailteux, J.-J., Sintubin M. Brittle tectonic and stress field evolution in the Pan-African Lufilian arc and its foreland (Katanga, DRC): from orogenic compression to extensional collapse, transpressional inversion and transition to rifting. Geologica Belgica, 2013, 16, 1-2, 1-17.

- Hanson R.E., Wilson T.J., Wardlaw M.S. Deformed batholiths in the Pan-African Zambezi age and implications for the regional Proterozoic tectonic. Geology, 1998, 16, 1134-1137.

- Unrug R. The Mwenbeshi and Zambezi dislocation systems: the central segment of a transcontinental shear zone in south-central Africa. Gondwana 7, 1991, San-Paolo (Brazil), 57-64.

- Chorowicz J., Le Fournier J., Vidal G. A model for rift developmpent in eastern Africa. In Bowden P. and Kinnaird J. (Eds). Africa, geology review. Geological Journal, 1987, 495-713.

- Chorowicz J. The East African rift system. J. Afric. Earth Sci. 2005, 43, 379-410.

- Fernandez-Alonso M., Delvaux D, Kervin F. Trefois P. Structural linéaments in the Aswa-Shear-Zone area, (Uganda and Soudan), Dep. Geol.Min.,Roy. Museum Central Africa, 1996,1-10.

- Saalman K., Mänttäri I., Nyakecho C., Isabirye E. Age, tectonic evolution and origin of the Aswa Shear Zone in Uganda: Activation of an oblique ramp during convergence in the East African Orogen. J. Afr Earth Sci., 2016, 117, 303-330.

- Theunissen K., Lenoir J.-L., Liegeois J.-P., Delvaux D. and Mruma A. Empreinte mozambiquienne majeure dans la chaîne ubendienne de Tanzanie sud-occidentale: géochronologie U-Pb sur zircon et contexte structural. C.R. Acad. Sci., Paris. 1992, 314, II, 1355-1362.

- Boniface N., Schenk V., Appel P. Paleoproterozoic eclogites of MORB-type chemistry and three Proterozoic orogenic cycles in the Ubendian Belt (Tanzania): evidence from monazite and zircon geochronology, and geochemistry. Prec. Res., 2012, 192-195, 16-33.

- Boniface N., Schenk V., Appel P. Mezoproterozoic high-grade metamorphism in pelitic rock of the northwestern Ubendian Belt : implication for the extension of the northwestern Kibaran intra-continental basins to Tanzania. Prec. Res. 2001, 249, 215-228.

- Daly M.C. Crustal shear zones in central Africa: a kinematic approach to Proterozoic Tectonics. Episodes, 1988, 11, 1, 5-11.

- Ring U, Kroner A., Buchwaldt A., Toulkeridis M., Layer P.W. Shear-zone patterns and eclogite-facies in the Mozambique belt of northern Malawi, east-central Africa: implications for the assembly of Gondwana. Prec. Res., 2002, 116,19-56.

- Bjelgard T., Stein H.J., Bingen B., Henderson I.H.C., Sandstad J.S., Moniz A. The Nyassa Gold Belt, northern Mozambique – A segment of a continental-scale Pan-African gold bearing structure. J. Afric. Earth Sci. 2009 53, 45-58.

- Maboko M.A.H, Mac Dougall I, Zeitler P.K. Dating Late Pan-African cooling in the Uluguru granulite complex of Eastern Tanzania using the40Ar/39Ar technique. J. Afric.Earth Sci., 1989, 9, 1 ,159-167.

- Chorowicz J., Le Fournier J., Mvumbi M.M.. La cuvette centrale du Zaire: un bassin initié au Protérozoique supérieur. Contribution de l’analyse du réseau hydrographique. C.R. Acad. Sci., Paris, 1990, 311, II, 349-356.

Figure 1.

The CC (Congo Craton) and Panafrican belts after Villeneuve et al. [

1], modified.

Legend: CB-Congo Block, BB-Bangwelu Block, WCB-West Congo Belt, EAB-East African Belts, KAB-Karagwe-Ankolean Belt, KVB- Kivu Belt, KIB- Kibarides, UBB-Ubendian Belt.

Figure 1.

The CC (Congo Craton) and Panafrican belts after Villeneuve et al. [

1], modified.

Legend: CB-Congo Block, BB-Bangwelu Block, WCB-West Congo Belt, EAB-East African Belts, KAB-Karagwe-Ankolean Belt, KVB- Kivu Belt, KIB- Kibarides, UBB-Ubendian Belt.

Figure 2.

The main post-Kibaran events in central Africa. Legend: I- Pan-African Orogen, II- Karoo deposits, III-east African Rift: Sediments and lavas.

Figure 2.

The main post-Kibaran events in central Africa. Legend: I- Pan-African Orogen, II- Karoo deposits, III-east African Rift: Sediments and lavas.

Figure 3.

The Neoproterozoic rifting in central Africa.

Figure 3a: The main belts linked to the Neoproterozoic rift, 1- Mont Homa, 2-Bunyoro, 3-Itombwe.

Legend: 1- Anorogenic intrusions, 2-basement, 3- Neoproterozoic covers, 4- Troughs and belts linked to the Neoproterozoic rift, 5- Fold “vergence” in the Neoproterozoic belts.

Figure 3b: 3D interpretation of the Neoproterozoic rift system.

Figure 3.

The Neoproterozoic rifting in central Africa.

Figure 3a: The main belts linked to the Neoproterozoic rift, 1- Mont Homa, 2-Bunyoro, 3-Itombwe.

Legend: 1- Anorogenic intrusions, 2-basement, 3- Neoproterozoic covers, 4- Troughs and belts linked to the Neoproterozoic rift, 5- Fold “vergence” in the Neoproterozoic belts.

Figure 3b: 3D interpretation of the Neoproterozoic rift system.

Figure 4.

Geology of the Itombwe belt

: 4a- sketch map of the Itombwe belt with location of the profile Tshondo-Nya-Kasiba, 4b-cross-section Tshondo-Nya-Kasiba, 4c -Interpretation of the Itombwe trough infilling.

Legend: Figure 4b- 1-Kibaran basement, 2-Nya-Kasiba conglomerate, 3-Nya-Kasiba formation (shales and sandstones), 4- Tshibabngu formation (mixtites and shales).

Figure 4.

Geology of the Itombwe belt

: 4a- sketch map of the Itombwe belt with location of the profile Tshondo-Nya-Kasiba, 4b-cross-section Tshondo-Nya-Kasiba, 4c -Interpretation of the Itombwe trough infilling.

Legend: Figure 4b- 1-Kibaran basement, 2-Nya-Kasiba conglomerate, 3-Nya-Kasiba formation (shales and sandstones), 4- Tshibabngu formation (mixtites and shales).

Figure 5.

Sedimentary succession in the Itombwe Belt. Legend: 1- Conglomerates, 2- Sandstones, 3-Mixtites (tillites), 4- shales, 5- Kibarian basement.

Figure 5.

Sedimentary succession in the Itombwe Belt. Legend: 1- Conglomerates, 2- Sandstones, 3-Mixtites (tillites), 4- shales, 5- Kibarian basement.

Figure 6.

Fold of the Itombwe Belt at centimeter scale; a: photograph of a centimeter fold, b-interpretation of the centimeter fold, c- Thin – section with biotites recristallized in the schists beds.

Figure 6.

Fold of the Itombwe Belt at centimeter scale; a: photograph of a centimeter fold, b-interpretation of the centimeter fold, c- Thin – section with biotites recristallized in the schists beds.

Figure 7.

Interferences between the NW-SE Kibaran structures P2 and the N-S post Kibaran P3 in the Nya-Ngezie area located on the eastern flank of the Itombwe syncline. The reworking of the P2 structures is linked to the Itombwe folding during the Pan-African tectonic event.

Figure 7a: Kilometric anticlines and synclines in the Kibaran basement.

Figure 7b-Interpretation of the “egg box” structures: 1- domes by interference of two anticlines, 2-bowls by interference of two synclines, 3- interferences of mixed structures: anticline/syncline versus syncline/anticline.

Figure 7.

Interferences between the NW-SE Kibaran structures P2 and the N-S post Kibaran P3 in the Nya-Ngezie area located on the eastern flank of the Itombwe syncline. The reworking of the P2 structures is linked to the Itombwe folding during the Pan-African tectonic event.

Figure 7a: Kilometric anticlines and synclines in the Kibaran basement.

Figure 7b-Interpretation of the “egg box” structures: 1- domes by interference of two anticlines, 2-bowls by interference of two synclines, 3- interferences of mixed structures: anticline/syncline versus syncline/anticline.

Figure 8.

3D diagram. Illustration of the reworking of the P2 (Kibarian folding) by the P3 (Pan-African folding), in the Nya-Ngezie area.

Figure 8.

3D diagram. Illustration of the reworking of the P2 (Kibarian folding) by the P3 (Pan-African folding), in the Nya-Ngezie area.

Figure 9.

Pan-African and Cenozoic lavas in East Africa. Legend: 1- Cenozoic and Quaternary lavas linked to the East African Rift. 2- Neoproterozoic rift, 3-Kundelungu aulacogen (Molassic formations), 4-Panafrican belts, 5-Basement (mainly kibarian), 6- ante Kibarian basements, 7- Displacement direction by the early Neoproterozoic, 8-Displacements of blocks during the Pan-African tectonic event. 9- Strike-slips along the transverse faults. KS-Kuunga suture, TB- Tanzanian Block, KC, Kalahari Craton, DC- Dharwar block, Kb-Kibalian, KS-Kasai Shield, AS- Antarctic Shield, CS- Shri-Lanka block, Kd- Kundelungu aulacogen, Luf- Lufilian belt (or Katangan belt), Zb-Zambezi belt., Lub luiro belt, (or Nampula block), Mzb_- Mozambique Belt., L-Lindian, MA- Malagarasian, Ngz-Nyangara-Zemio belt, Hm, Mount Homa belt, Bun-Bunyoro belt, Upb-Upemba belt,, Bu- Bushimay belt., ASFZ- Aswa Fault Zone, RKFZ- Rukwe Fault Zone, MBFZ-Mwenbezi Fault Zone.ML-Malagarasi Lake, TL-Tanganyika Lake, KL-Kivu Lake, EL-Edouard Lake, LA-Lake Albert, VL-Victoria Lake, BL-Bangwelo Lake, MoL-Moero Lake. .

Figure 9.

Pan-African and Cenozoic lavas in East Africa. Legend: 1- Cenozoic and Quaternary lavas linked to the East African Rift. 2- Neoproterozoic rift, 3-Kundelungu aulacogen (Molassic formations), 4-Panafrican belts, 5-Basement (mainly kibarian), 6- ante Kibarian basements, 7- Displacement direction by the early Neoproterozoic, 8-Displacements of blocks during the Pan-African tectonic event. 9- Strike-slips along the transverse faults. KS-Kuunga suture, TB- Tanzanian Block, KC, Kalahari Craton, DC- Dharwar block, Kb-Kibalian, KS-Kasai Shield, AS- Antarctic Shield, CS- Shri-Lanka block, Kd- Kundelungu aulacogen, Luf- Lufilian belt (or Katangan belt), Zb-Zambezi belt., Lub luiro belt, (or Nampula block), Mzb_- Mozambique Belt., L-Lindian, MA- Malagarasian, Ngz-Nyangara-Zemio belt, Hm, Mount Homa belt, Bun-Bunyoro belt, Upb-Upemba belt,, Bu- Bushimay belt., ASFZ- Aswa Fault Zone, RKFZ- Rukwe Fault Zone, MBFZ-Mwenbezi Fault Zone.ML-Malagarasi Lake, TL-Tanganyika Lake, KL-Kivu Lake, EL-Edouard Lake, LA-Lake Albert, VL-Victoria Lake, BL-Bangwelo Lake, MoL-Moero Lake. .

Figure 10.

The main Panafrican thermo-tectonic events according to the radiometric data delivered by twelve authors.

Legend: Pinna [

36], Shakleton et al. [

38], Mosley et al. [

42], Goudenough et al. [X], Thomas et al. [

43], Maboko et al. [

44], Grantham et al. [

37], Fitzsimons et al. [

39], Rosseti et al. [

45], Kroner, [

46], Tenzer et al. [

47], Vogt et al. [

48]. Circled number: the main Panafrican events in Eastern Africa.

Figure 10.

The main Panafrican thermo-tectonic events according to the radiometric data delivered by twelve authors.

Legend: Pinna [

36], Shakleton et al. [

38], Mosley et al. [

42], Goudenough et al. [X], Thomas et al. [

43], Maboko et al. [

44], Grantham et al. [

37], Fitzsimons et al. [

39], Rosseti et al. [

45], Kroner, [

46], Tenzer et al. [

47], Vogt et al. [

48]. Circled number: the main Panafrican events in Eastern Africa.

Figure 11.

The main thermo-tectonic events recorded on the transcurrent faults, according to the radiometric data delivered by six authors.

Legend: Boniface et al. [

59], Ring et al. [

62], Theunissen et al. [

58], Bjelgard et al. [

63], Maboko et al. [

64], Saalman et al. [

57].

Figure 11.

The main thermo-tectonic events recorded on the transcurrent faults, according to the radiometric data delivered by six authors.

Legend: Boniface et al. [

59], Ring et al. [

62], Theunissen et al. [

58], Bjelgard et al. [

63], Maboko et al. [

64], Saalman et al. [

57].

Figure 12.

Neoproterozoic structuration of the Congo basin. (after Chorowicz et al. [

65] modified).

Legend: CB-Congo basin, LM- Lake Moero, LT- Lake Tanganyika, LK-Lake Kivu, LE-Lake Edouard, LA-Lake Albert. LV-Lake Victoria. Red arrow-Strike-slips, Violet arrows- tectonic stress.

Figure 12.

Neoproterozoic structuration of the Congo basin. (after Chorowicz et al. [

65] modified).

Legend: CB-Congo basin, LM- Lake Moero, LT- Lake Tanganyika, LK-Lake Kivu, LE-Lake Edouard, LA-Lake Albert. LV-Lake Victoria. Red arrow-Strike-slips, Violet arrows- tectonic stress.

Figure 13.

Illustration of three main stages in the geodynamic evolution of the Panafrican belts in Central and Eastern Africa. Legend: 1- Cratons, 2- Subduction zones and sutures, 3-Belts, 4- Moving direction of blocks, CC-Congo Craton, DC-Dharwar Craton, K-Kalahari craton, ITR-Itremo Block, DM-Droning-Maud Block, M-Mawson block, Ao-Adamastor Ocean, SF- Sao-Francisco block, WA-West African craton, S-Saharan Craton, RP- Rio de la Plata Block , Da-Damara ocean, DM-Damara Belt, G- Gariep Belt, Ko-Khomas Ocean,.

Figure 13.

Illustration of three main stages in the geodynamic evolution of the Panafrican belts in Central and Eastern Africa. Legend: 1- Cratons, 2- Subduction zones and sutures, 3-Belts, 4- Moving direction of blocks, CC-Congo Craton, DC-Dharwar Craton, K-Kalahari craton, ITR-Itremo Block, DM-Droning-Maud Block, M-Mawson block, Ao-Adamastor Ocean, SF- Sao-Francisco block, WA-West African craton, S-Saharan Craton, RP- Rio de la Plata Block , Da-Damara ocean, DM-Damara Belt, G- Gariep Belt, Ko-Khomas Ocean,.

Table 1.

Radiometric data on the anorogenic complex around the Itombwe belt.

Table 1.

Radiometric data on the anorogenic complex around the Itombwe belt.

| Location |

Methods |

Data |

References |

| Lueshe |

Rb/Sr |

822+/-120 Ma |

[18] |

| Lueshe |

U/Pb |

798.5 + :-4.9 Ma |

[19] |

| Kirumba |

Rb/Sr |

803+/-22 Ma |

[18] |

| Numbi |

Rb/Sr |

830+ /--51 Ma |

[18] |

| Kobokobo |

U/Pb sur Beryl |

900 Ma |

[20] |

| Kahuzi 1 |

U/Pb |

825 +/-5Ma |

[21,34] |

| Kahuzi 2 |

U/Pb |

814+/-5 |

[34] |

| Matongo/Hte Ruvubu |

U/Pb |

705+ /-4.5 Ma |

[19] |

| Matongo/Hte Ruvubu |

U /Pb and Rb/Sr wr |

740+/-7 Ma |

[22] |

| Kambuzi |

|

542/-27 Ma |

[23] |

Table 3.

Radiometric ages ascribed to the Panafrican thermo-tectonic events in the vicinity of the Itombwe syncline. Legend: G2/G4-Kibaran granites, Neoprot. com.-Neoproterozoic complex.wr-whole rock.

Table 3.

Radiometric ages ascribed to the Panafrican thermo-tectonic events in the vicinity of the Itombwe syncline. Legend: G2/G4-Kibaran granites, Neoprot. com.-Neoproterozoic complex.wr-whole rock.

| Location |

Method |

Age |

Generation of granite |

References |

| Kasika |

Rb/Sr (microcline) |

ca.520±9 Ma |

G2/G4 |

Monteyne et al. [30] |

| Kirumba |

Rb/Sr (whole rock) |

ca.578±9 Ma |

G4 |

Cahen et al. [31] |

| Numbi |

Rb/Sr (whole rock) |

ca.648 Ma |

G4 |

Cahen et al. [31] |

| Kadubu Riv. |

Ar/Ar (muscovite) |

ca.575+/-83Ma |

Phyllite Itombwe |

Walemba & Master [13] |

| Kahuzi |

K/Ar wr |

452+/-11 Ma |

Neoprot. com. |

Vellutini et al. [21] |

| Biega |

K/Ar wr |

442+/-11 Ma |

Neoprot. com. |

Vellutini et al. [21] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).