Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

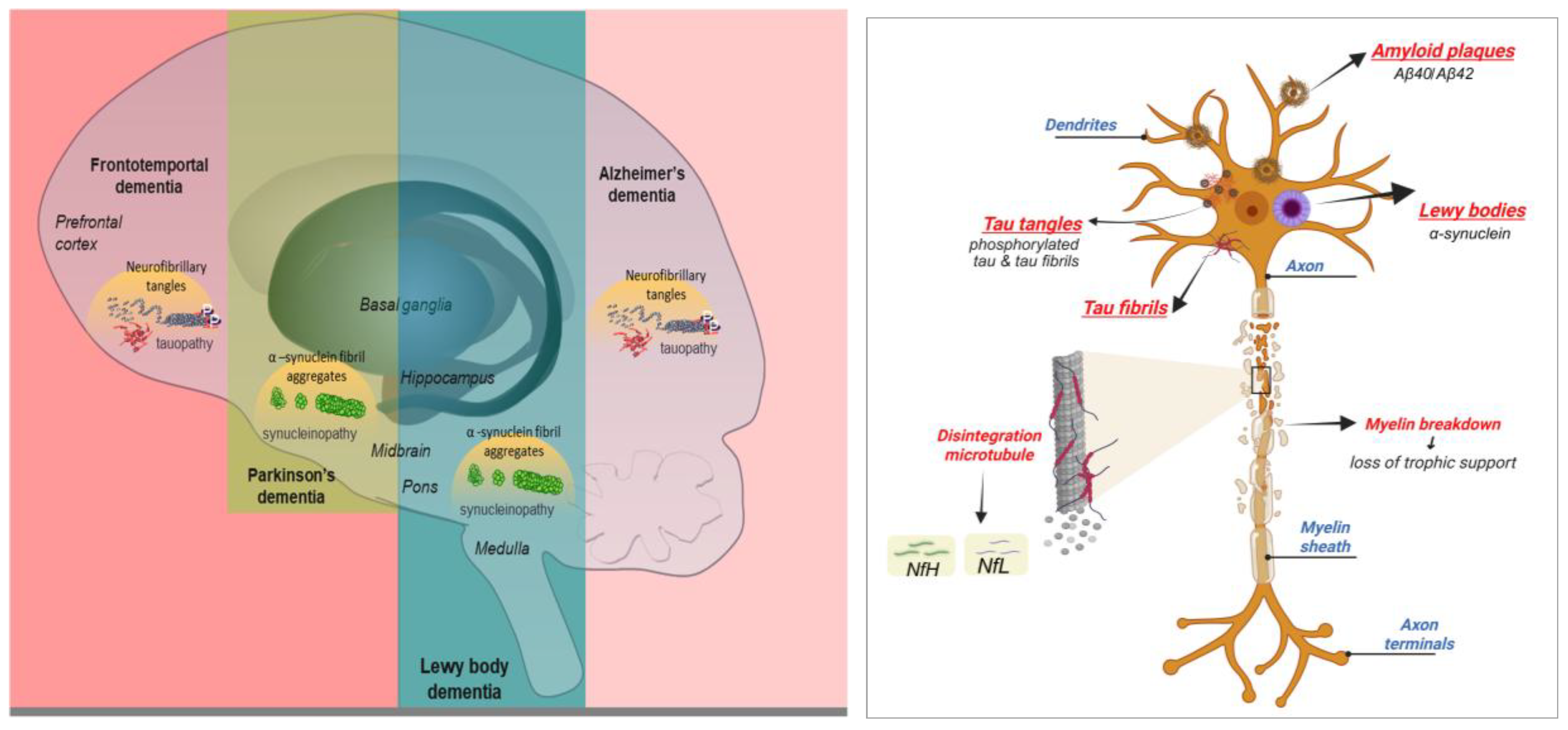

2. Alzheimer's Disease (AD)

3. Lewy Body Dementia (LBD)

3.1. Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB)

2.2. Parkinson’s Disease Dementia (PDD)

4. Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)

5. Huntington's Diseases (HD)

6. Mixed Dementia

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| APP | amyloid precursor protein |

| AT(N) | amyloid/tau/neurodegeneration |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| Aβ | amyloid-β peptide |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| BMP | bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate |

| bvFTD | behavioural variant FTD |

| CAG | Cytosine–Adenine–Guanine |

| CE | cholesteryl ester |

| Cer | ceramide |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT | computer tomography |

| DESI | desorption electrospray ionization |

| DLB | dementia with Lewy body |

| DMS | differential ion mobility spectrometry |

| ESI | electrospray ionization |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FDG-PET | fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography |

| FTD | frontotemporal dementia |

| GalCer | galactosylceramide |

| GalSph | galactosylsphingosine |

| GCase | β-glucocerebrosidase |

| GG | ganglioside |

| GlcCer | glucosylceramide |

| GlcSph | glucosylsphingosine |

| GM | monosialoganglioside |

| GRN | progranulin gene |

| GroPIn | glycerophosphoinositol |

| GSL | glycosphingolipid |

| HD | Huntington’s disease |

| HDD | Huntington’s disease dementia |

| Hex1Cers | monohexosylceramides |

| HEXA | Hexosaminidase Subunit Alpha gene |

| HexCers | hexosylceramides |

| HTT | huntingtin gene |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| IMS-MS | ion mobility spectrometry |

| LacCer | lactosylceramide |

| LBD | Lewy body Dementia |

| LC-MS | liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry |

| MALDI | matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization |

| MGDG | monogalactosyldiacylglycerol |

| mHTT | mutant huntingtin |

| ML | machine learning |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MS | mass spectrometry |

| MS/MS | tandem mass spectrometry |

| MSI | mass spectrometry imaging |

| NfL | neurofilament light chain |

| NFT | neurofibrillary tangles |

| PC | phosphatidylcholine |

| PD | Parkinson's disease |

| PDD | Parkinson's disease dementia |

| PE | phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PGRN | progranulin |

| p-tau | phosphorylated tau |

| QTOF | quadrupol time of flight |

| SHexCer | sulfatide |

| SIMS | secondary ion mass spectrometry |

| SIVD | subcortical ischemic vascular dementia |

| SM | sphingomyelin |

| SP | senile plaques |

| SPECT | single photon emission computer tomography |

| SRM | selected reaction monitoring |

| TG | triglyceride |

| TLC | thin-layer chromatography |

| UHPLC MS/MS | ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem MS |

| VD | vascular dementia |

| VLCFA | very long-chain fatty acid |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WT | wild-type |

References

- Gale, S.A.; Acar, D.; Daffner, K.R. Dementia. Am. J. Med.2018, 131, 1161–1169. [CrossRef]

- Duara, R.; Barker, W. Heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis and Progression Rates: Implications for Therapeutic Trials. Neurotherapeutics2022, 19, 8–25. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Recent Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Trials and New Drug Development Strategies. Signal Transduct. Target Ther.2024, 9, 211. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.; Gochanour, C.; Caspell-Garcia, C.; Dobkin, R.D.; Aarsland, D.; Alcalay, R.N.; Barrett, M.J.; Chahine, L.; Chen-Plotkin, A.S.; Coffey, C.S.; et al. Long-Term Dementia Risk in Parkinson Disease. Neurology2024, 103, e209699.

- Hobbs, N.Z.; Barnes, J.; Frost, C.; Henley, S.M.; Wild, E.J.; Macdonald, K.; Barker, R.A.; Scahill, R.I.; Fox, N.C.; Tabrizi, S.J. Onset and Progression of Pathologic Atrophy in Huntington Disease: A Longitudinal MR Imaging Study. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.2010, 31, 1036–1041. [CrossRef]

- Aarsland, D.; Kurz, M.W. The Epidemiology of Dementia Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Pathol.2010, 20, 633–639. [CrossRef]

- Custodio, N.; Montesinos, R.; Lira, D.; Herrera-Pérez, E.; Bardales, Y.; Valeriano-Lorenzo, L. Mixed Dementia: A Review of the Evidence. Dement. Neuropsychol.2017, 11, 364–370. [CrossRef]

- Attems, J.; Jellinger, K.A. The Overlap between Vascular Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease—Lessons from Pathology. BMC Med.2014, 12, 206. [CrossRef]

- Vollhardt, A.; Frölich, L.; Stockbauer, A.C.; Danek, A.; Schmitz, C.; Wahl, A.-S. Towards a Better Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia: Identifying Common and Distinct Neuropathological Mechanisms in Alzheimer’s and Vascular Dementia. Neurobiol. Dis.2025, 208, 106638. [CrossRef]

- Mohandas, E.; Rajmohan, V. Frontotemporal Dementia: An Updated Overview. Indian J. Psychiatry2009, 51 (Suppl.1), S65–S69.

- Rabinovici, G.D.; Miller, B.L. Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. CNS Drugs2010, 24, 375–398.

- Mollah, S.A.; Nayak, A.; Barhai, S.; Maity, U. A Comprehensive Review on Frontotemporal Dementia: Its Impact on Language, Speech and Behavior. Dement. Neuropsychol.2024, 18, e20230072. [CrossRef]

- Deleon, J.; Miller, B.L. Frontotemporal Dementia. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Geschwind, D.H., Paulson, H.L., Klein, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 148, pp. 409–430.

- Roberson, E.D.; Hesse, J.H.; Rose, K.D.; Slama, H.; Johnson, J.K.; Yaffe, K.; Forman, M.S.; Miller, C.A.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Kramer, J.H.; Miller, B.L. Frontotemporal Dementia Progresses to Death Faster than Alzheimer Disease. Neurology2005, 65, 719–725. [CrossRef]

- Foxe, D.; Muggleton, J.; Cheung, S.C.; Mueller, N.; Ahmed, R.M.; Narasimhan, M.; Burrell, J.R.; Hwang, Y.T.; Cordato, N.J.; Piguet, O. Survival Rates in Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag.2025, 15, 191–197. [CrossRef]

- Antonioni, A.; Raho, E.M.; Lopriore, P.; Pace, A.P.; Latino, R.R.; Assogna, M.; Mancuso, M.; Gragnaniello, D.; Granieri, E.; Pugliatti, M.; et al. Frontotemporal Dementia, Where Do We Stand? A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2023, 24, 11732. [CrossRef]

- Manabe, T.; Fujikura, Y.; Mizukami, K.; Akatsu, H.; Kudo, K. Pneumonia-Associated Death in Patients with Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE2019, 14, e0213825. [CrossRef]

- Amoatika, D.A.; Absher, J.R.; Khan, M.T.F.; Miller, M.C. Dementia Deaths Most Commonly Result from Heart and Lung Disease: Evidence from the South Carolina Alzheimer’s Disease Registry. Biomedicines2025, 13, 1321. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, Q. Mortality Rate of Pulmonary Infection in Senile Dementia Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore)2024, 103, e39816. [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Boeve, B.F.; Dickson, D.W.; Halliday, G.; Taylor, J.P.; Weintraub, D.; Aarsland, D.; Galvin, J.; Attems, J.; Ballard, C.G.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia with Lewy Bodies: Fourth Consensus Report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology2017, 89, 88–100. [CrossRef]

- Walker, Z.; Possin, K.L.; Boeve, B.F.; Aarsland, D. Lewy Body Dementias. Lancet2015, 386, 1683–1697. [CrossRef]

- Cycyk, L.M.; Wright, H.H. Frontotemporal Dementia: Its Definition, Differential Diagnosis, and Management. Aphasiology2008, 22, 422–444. [CrossRef]

- Tampi, R.R.; Tampi, D.J.; Parish, M. Easy to Miss, Hard to Treat: Notes on Frontotemporal Dementia. Psychiatric Times2020, 37, 37(10).

- Muangpaisan, W. Clinical Differences among Four Common Dementia Syndromes. Geriatrics Aging2007, 10, 425–429.

- Harciarek, M.; Jodzio, K. Neuropsychological Differences between Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review. Neuropsychol. Rev.2005, 15, 131–145. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Xu, Z.; Han, X. Lipidome Disruption in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain: Detection, Pathological Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Implications. Mol. Neurodegener.2025, 20, 11. [CrossRef]

- Osetrova, M.; Tkachev, A.; Mair, W.; Guijarro Larraz, P.; Efimova, O.; Kurochkin, I.; Stekolshchikova, E.; Anikanov, N.; Foo, J.C.; Cazenave-Gassiot, A.; et al. Lipidome Atlas of the Adult Human Brain. Nat. Commun.2024, 15, 4455. [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.K.; Nakatani, Y.; Yanagisawa, M. The Role of Glycosphingolipid Metabolism in the Developing Brain. J. Lipid Res.2009, 50 (Suppl.), S440–S445. [CrossRef]

- Grassi, S.; Giussani, P.; Mauri, L.; Prioni, S.; Sonnino, S.; Prinetti, A. Lipid Rafts and Neurodegeneration: Structural and Functional Roles in Physiologic Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Lipid Res.2020, 61, 636–654. [CrossRef]

- Ledeen, R.; Wu, G. Gangliosides of the Nervous System. Methods Mol. Biol.2018, 1804, 19–55. [CrossRef]

- Blomqvist, M.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Månsson, J.E. Sulfatide in Health and Disease: The Evaluation of Sulfatide in Cerebrospinal Fluid as a Possible Biomarker for Neurodegeneration. Mol. Cell. Neurosci.2021, 116, 103670. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wong, L.C.; Boland, S. Lipids as Emerging Biomarkers in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2023, 25, 131. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.R.; Gahl, W.A. Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Transl. Sci. Rare Dis.2017, 2, 1–71. [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, K. Aβ-Ganglioside Interactions in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr.2020, 1862, 183233. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, R.; Wong, G.; Huang, X. Lewy Body Dementia: Exploring Biomarkers and Pathogenic Interactions of Amyloid β, Tau, and α-Synuclein. Mol. Neurodegener.2025, 20, 90. [CrossRef]

- Di Pardo, A.; Maglione, V.; Alpaugh, M.; Horkey, M.; Atwal, R.S.; Sassone, J.; Ciammola, A.; Steffan, J.S.; Fouad, K.; Truant, R.; Sipione, S. Ganglioside GM1 Induces Phosphorylation of Mutant Huntingtin and Restores Normal Motor Behavior in Huntington Disease Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.2012, 109, 3528–3533. [CrossRef]

- Magistretti, P.J.; Geisler, F.H.; Schneider, J.S.; Li, P.A.; Fiumelli, H.; Sipione, S. Gangliosides: Treatment Avenues in Neurodegenerative Disease. Front. Neurol.2019, 10, 859. [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, A.D. Neurological Analyses: Focus on Gangliosides and Mass Spectrometry. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.2014, 806, 153–204. [CrossRef]

- Müthing, J. High-Resolution Thin-Layer Chromatography of Gangliosides Methods. J. Chromatogr. A. 1996, 720, 3–25. [CrossRef]

- Nishina, K.A.; Supattapone, S. Immunodetection of Glycophosphatidylinositol-Anchored Proteins Following Treatment with Phospholipase C. Anal. Biochem.2007, 363, 318–320. [CrossRef]

- Dehelean, L.; Sarbu, M.; Petrut, A.; Zamfir, A.D. Trends in Glycolipid Biomarker Discovery in Neurodegenerative Disorders by Mass Spectrometry. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.2019, 1140, 703–729. [CrossRef]

- Touboul, D.; Gaudin, M. Lipidomics of Alzheimer's Disease. Bioanalysis2014, 6, 541–561. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Suzuki, M.; Ito, E.; Nitta, T.; Inokuchi, J.I. Mass Spectrometry of Gangliosides. Methods Mol. Biol.2018, 1804, 207–221. [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.E.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Quiason, C.; Dale, S.; Shahidi-Latham, S.; Grabowski, G.A.; Setchell, K.D.R.; Drake, R.R.; Sun, Y. Tissue Localization of Glycosphingolipid Accumulation in a Gaucher Disease Mouse Brain by LC-ESI-MS/MS and High-Resolution MALDI Imaging Mass Spectrometry. SLAS Discov.2017, 22, 1218–1228. [CrossRef]

- Lanekoff, I.; Geydebrekht, O.; Pinchuk, G.E.; Konopka, A.E.; Laskin, J. Spatially Resolved Analysis of Glycolipids and Metabolites in Living Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 Using Nanospray Desorption Electrospray Ionization. Analyst2013, 138, 1971–1978. [CrossRef]

- Shon, H.K.; Son, J.G.; Lee, S.Y.; Moon, J.H.; Lee, G.S.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, T.G. Comparison Study of Mouse Brain Tissue by Using ToF-SIMS within Static Limits and Hybrid SIMS Beyond Static Limits (Dynamic Mode). Biointerphases2023, 18, 031005. [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, M.; Fabris, D.; Vukelić, Ž.; Clemmer, D.E.; Zamfir, A.D. Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry Reveals Rare Sialylated Glycosphingolipid Structures in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid. Molecules2022, 27, 743. [CrossRef]

- Biricioiu, M.R.; Sarbu, M.; Ica, R.; Vukelić, Ž.; Clemmer, D.E.; Zamfir, A.D. Human Cerebellum Gangliosides: A Comprehensive Analysis by Ion Mobility Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom.2024, 35, 683–695. [CrossRef]

- Ica, R.; Sarbu, M.; Biricioiu, R.; Fabris, D.; Vukelić, Ž.; Zamfir, A.D. Novel Application of Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry Reveals Complex Ganglioside Landscape in Diffuse Astrocytoma Peritumoral Regions. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2025, 26, 8433. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Boucher, F.R.; Nguyen, T.T.; Taylor, G.P.; Tomlinson, J.J.; Ortega, R.A.; Simons, B.; Schlossmacher, M.G.; Saunders-Pullman, R.; Shaw, W.; Bennett, S.A.L. DMS as an Orthogonal Separation to LC/ESI/MS/MS for Quantifying Isomeric Cerebrosides in Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid. J. Lipid Res.2019, 60, 200–211. [CrossRef]

- Michno, W.; Bowman, A.; Jha, D.; Minta, K.; Ge, J.; Koutarapu, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Lashley, T.; Heeren, R.M.A.; Hanrieder, J. Spatial Neurolipidomics at the Single Amyloid-β Plaque Level in Postmortem Human Alzheimer's Disease Brain. ACS Chem. Neurosci.2024, 15, 877–888. [CrossRef]

- Evers, B.M.; Rodriguez-Navas, C.; Tesla, R.J.; Prange-Kiel, J.; Wasser, C.R.; Yoo, K.S.; McDonald, J.; Cenik, B.; Ravenscroft, T.A.; Plattner, F.; et al. Lipidomic and Transcriptomic Basis of Lysosomal Dysfunction in Progranulin Deficiency. Cell Rep.2017, 20, 2565–2574. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Nie, Y.; Tang, Y.; Qu, M. Plasma Lipidomic Signatures of Dementia with Lewy Bodies Revealed by Machine Learning, and Compared to Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther.2024, 16, 226. [CrossRef]

- Galleguillos, D.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, B.; Vandermeer, B.; Zaidi, A.; Al Hamarneh, Y.N.; Sarna, J.; Suchowersky, O.; Curtis, J.; Sipione, S. Plasma Gangliosides Correlate with Disease Stages and Symptom Severity in Huntington’s Disease Carriers. bioRxiv2025. [CrossRef]

- Strnad, Š.; PraŽienková, V.; Holubová, M.; Sýkora, D.; Cvačka, J.; Maletínská, L.; Železná, B.; Kuneš, J.; Vrkoslav, V. Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Free-Floating Brain Sections Detects Pathological Lipid Distribution in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's-like Pathology. Analyst2020, 145, 4595–4605. [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.; Chen, L.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Metabolomics and Isotope Tracing. Cell2018, 173, 822–837. [CrossRef]

- Toprakcioglu, Z.; Jayaram, A.K.; Knowles, T.P.J. Ganglioside Lipids Inhibit the Aggregation of the Alzheimer's Amyloid-β Peptide. RSC Chem. Biol.2025, 6, 809–822. [CrossRef]

- Galper, J.; Dean, N.J.; Pickford, R.; Lewis, S.J.G.; Halliday, G.M.; Kim, W.S.; Dzamko, N. Lipid Pathway Dysfunction Is Prevalent in Patients with Parkinson's Disease. Brain2022, 145, 3472–3487. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Jia, C.; Wu, H.; Liao, Y.; Yang, K.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, G.; Guan, F.; et al. Nao Tan Qing Ameliorates Alzheimer's Disease-like Pathology by Regulating Glycolipid Metabolism and Neuroinflammation: A Network Pharmacology Analysis and Biological Validation. Pharmacol. Res.2022, 185, 106489. [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/dementia-statistics/ (accessed on 30.09.2025).

- Zhang, X.; Lu, H.; Xiong, J. Incidence trends and age-period-cohort analysis of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in the world and China from 1990 to 2021: analyses based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Front. Neurol.2025, 16, 1628577. [CrossRef]

- Korczyn, A.D.; Grinberg, L.T. Is Alzheimer disease a disease? Nat. Rev. Neurol.2024, 20(4), 245–251. [CrossRef]

- Kamatham, P.T.; Shukla, R.; Khatri, D.K.; Vora, L.K. Pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics for Alzheimer's disease: Breaking the memory barrier. Ageing Res. Rev.2024, 101, 102481. [CrossRef]

- Oka, T.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Tsuneyoshi, M.; et al. Multiomics analysis to explore blood metabolite biomarkers in an Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort. Sci. Rep.2024, 14(1), 6797. [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’sAssociation. 2018 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures Alzheimer's & Dementia2018, 14, 367-429. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tahami Monfared, A.A.; Zhang, Q.; Honig, L.S. Incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in Medicare beneficiaries. Neurol. Ther.2025, 14(1), 319–333. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Myers, S.J.; Ollen-Bittle, N.; Whitehead, S.N. Elevation of ganglioside degradation pathway drives GM2 and GM3 within amyloid plaques in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Dis.2025, 205, 106798. [CrossRef]

- Cerasuolo, M.; Di Meo, I.; Auriemma, M.C.; Paolisso, G.; Papa, M.; Rizzo, M.R. Exploring the dynamic changes of brain lipids, lipid rafts, and lipid droplets in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Biomolecules2024, 14(11), 1362. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Wei, X.; Han, B.; et al. Quantitative analysis of targeted lipidomics in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice employing the UHPLC-MS/MS method. Front. Aging Neurosci.2025, 17, 1561831. [CrossRef]

- Ariga, T.; Kubota, M.; Nakane, M.; Oguro, K.; Yu, R.K.; Ando, S. Anti-Chol-1 antigen, GQ1bα, antibodies are associated with Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One2013, 8(5), e63326. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Li, Q. Global incidence trends and projections of Alzheimer disease and other dementias: an age-period-cohort analysis 2021. J. Glob. Health2025, 15, 04156. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, R.; Sun, X.; et al. Preferential regulation of γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of APP by ganglioside GM1 reveals a potential therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.)2023, 10(32), e2303411. [CrossRef]

- Hirano-Sakamaki, W.; Sugiyama, E.; Hayasaka, T.; Ravid, R.; Setou, M.; Taki, T. Alzheimer's disease is associated with disordered localization of ganglioside GM1 molecular species in the human dentate gyrus. FEBS Lett.2015, 589(23), 3611–3616. [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; De Strooper, B.; Kivipelto, M.; et al. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet2021, 397(10284), 1577–1590. [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Barnes, J.M.; Young, S.A.; et al. Discovery and confirmation of diagnostic serum lipid biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease using direct infusion mass spectrometry. J. Alzheimers Dis.2017, 59(1), 277–290. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Holtzman, D.M.; McKeel, D.W., Jr.; Kelley, J.; Morris, J.C. Substantial sulfatide deficiency and ceramide elevation in very early Alzheimer's disease: potential role in disease pathogenesis. J. Neurochem.2002, 82(4), 809–818. [CrossRef]

- Yuyama, K.; Sun, H.; Sakai, S.; et al. Decreased amyloid-β pathologies by intracerebral loading of glycosphingolipid-enriched exosomes in Alzheimer model mice. J. Biol. Chem.2014, 289(35), 24488–24498. [CrossRef]

- González-Domínguez, R.; García-Barrera, T.; Gómez-Ariza, J.L. Metabolomic study of lipids in serum for biomarker discovery in Alzheimer's disease using direct infusion mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.2014, 98, 321–326. [CrossRef]

- Michno, W.; Wehrli, P.M.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Hanrieder, J. GM1 locates to mature amyloid structures implicating a prominent role for glycolipid-protein interactions in Alzheimer pathology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom.2019, 1867(5), 458–467. [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, M.; Ica, R.; Zamfir, A.D. Gangliosides as biomarkers of human brain diseases: Trends in discovery and characterization by high-performance mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2022, 23(2), 693. [CrossRef]

- Chi, E.Y.; Frey, S.L.; Lee, K.Y. Ganglioside GM1-mediated amyloid-beta fibrillogenesis and membrane disruption. Biochemistry2007, 46(7), 1913–1924. [CrossRef]

- Oikawa, N.; Matsubara, T.; Fukuda, R.; et al. Imbalance in fatty-acid-chain length of gangliosides triggers Alzheimer amyloid deposition in the precuneus. PLoS One2015, 10(3), e0121356. [CrossRef]

- Goux, W.J.; Rodriguez, S.; Sparkman, D.R. Analysis of the core components of Alzheimer paired helical filaments: a gas chromatography/mass spectrometry characterization of fatty acids, carbohydrates and long-chain bases. FEBS Lett.1995, 366(1), 81–85. [CrossRef]

- Goux, W.J.; Liu, B.; Shumburo, A.M.; Parikh, S.; Sparkman, D.R. A quantitative assessment of glycolipid and protein associated with paired helical filament preparations from Alzheimer's diseased brain. J. Alzheimers Dis.2001, 3(5), 455–466.

- Chakraborty, A.; Praharaj, S.K.; Prabhu, R.K.; Prabhu, M.M. Lipidomics and cognitive dysfunction–a narrative review. Turk. J. Biochem.2020, 45(2), 109–119. [CrossRef]

- Ollen-Bittle, N.; Pejhan, S.; Pasternak, S.H.; Keene, C.D.; Zhang, Q.; Whitehead, S.N. Co-registration of MALDI-MSI and histology demonstrates gangliosides co-localize with amyloid beta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol.2024, 147(1), 105. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Sui, P.; Sun, X.H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.Y. MALDI mass spectrometry imaging discloses the decline of sulfoglycosphingolipid and glycerophosphoinositol species in the brain regions related to cognition in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Talanta2024, 266(2), 125022. [CrossRef]

- Blank, M.; Hopf, C. Spatially resolved mass spectrometry analysis of amyloid plaque-associated lipids. J. Neurochem.2021, 159(2), 330–342. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Meng, F.; et al. Serum metabolites differentiate amnestic mild cognitive impairment from healthy controls and predict early Alzheimer's disease via untargeted lipidomics analysis. Front. Neurol.2021, 12, 704582. [CrossRef]

- Ariga, T.; Jarvis, W.D.; Yu, R.K. Role of sphingolipid-mediated cell death in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Lipid Res.1998, 39(1), 1–16.

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. Mass spectrometry-based ganglioside profiling provides potential insights into Alzheimer's disease development. J. Chromatogr. A. 2022, 1676, 463196. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Combination of ESI and MALDI mass spectrometry for qualitative, semi-quantitative and in situ analysis of gangliosides in brain. Sci. Rep.2016, 6, 25289. [CrossRef]

- Taki, T. An approach to glycobiology from glycolipidomics: ganglioside molecular scanning in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease by TLC-blot/matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight MS. Biol. Pharm. Bull.2012, 35(10), 1642–1647.

- Caughlin, S.; Maheshwari, S.; Agca, Y.; et al. Membrane-lipid homeostasis in a prodromal rat model of Alzheimer's disease: characteristic profiles in ganglioside distributions during aging detected using MALDI imaging mass spectrometry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj.2018, 1862(6), 1327–1338. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, I.; Jennische, E.; Dunevall, J.; et al. Spatial lipidomics reveals region and long chain base specific accumulations of monosialogangliosides in amyloid plaques in familial Alzheimer's disease mice (5xFAD) brain. ACS Chem. Neurosci.2020, 11(1), 14–24. [CrossRef]

- Good, C.J.; Bowman, A.P.; Klein, C.; et al. Spatial mapping of gangliosides and proteins in amyloid beta plaques at cellular resolution using mass spectrometry imaging and MALDI-IHC. J. Mass Spectrom.2025, 60(9), e5161. [CrossRef]

- Caughlin, S.; Hepburn, J.D.; Park, D.H.; et al. Increased expression of simple ganglioside species GM2 and GM3 detected by MALDI imaging mass spectrometry in a combined rat model of Aβ toxicity and stroke. PLoS One2015, 10(6), e0130364. [CrossRef]

- Fantini, J.; Yahi, N.; Garmy, N. Cholesterol accelerates the binding of Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide to ganglioside GM1 through a universal hydrogen-bond-dependent sterol tuning of glycolipid conformation. Front. Physiol.2013, 4, 120. [CrossRef]

- Yahi, N.; Fantini, J. Deciphering the glycolipid code of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's amyloid proteins allowed the creation of a universal ganglioside-binding peptide. PLoS One2014, 9(8), e104751. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Katta, M.R.; Abhishek, S.; et al. Recent advances in Lewy body dementia: A comprehensive review. Dis. Mon.2023, 69(5), 101441. [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.; Mintzer, J.; Aarsland, D.; et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol.2004, 3(1), 19–28. [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, K.; Nishizawa, M.; Ikeuchi, T. α-Synuclein as CSF and blood biomarker of dementia with Lewy bodies. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis.2012, 2012, 437025. [CrossRef]

- Ferman, T.J.; Aoki, N.; Crook, J.E.; et al. The limbic and neocortical contribution of α-synuclein, tau, and amyloid β to disease duration in dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Dement.2018, 14(3), 330–339. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.J. Advances in dementia with Lewy bodies. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord.2021, 14, 17562864211057666. [CrossRef]

- Scamarcia, P.G.; Agosta, F.; Caso, F.; Filippi, M. Update on neuroimaging in non-Alzheimer's disease dementia: a focus on the Lewy body disease spectrum. Curr. Opin. Neurol.2021, 34(4), 532–538. [CrossRef]

- Kantarci, K.; Lowe, V.J.; Chen, Q.; et al. β-Amyloid PET and neuropathology in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology2020, 94(3), e282–e291. [CrossRef]

- Palmqvist, S.; Hansson, O.; Minthon, L.; Londos, E. Practical suggestions on how to differentiate dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer's disease with common cognitive tests. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry2009, 24(12), 1405–1412. [CrossRef]

- Senanarong, V.; Wachirutmangur, L.; Rattanabunnakit, C.; Srivanitchapoom, P.; Udomphanthurak, S. Plasma alpha synuclein (α-syn) as a potential biomarker of diseases with synucleinopathy. Alzheimers Dement.2020, 16(S9), e044409.

- Mukaetova-Ladinska, E.B.; Monteith, R.; Perry, E.K. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for dementia with Lewy bodies. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis.2010, 2010, 536538.

- Mollenhauer, B.; Schlossmacher, M.G. CSF synuclein: adding to the biomarker footprint of dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry2010, 81(6), 590–591. [CrossRef]

- Donadio, V.; Incensi, A.; Rizzo, G.; et al. A new potential biomarker for dementia with Lewy bodies: Skin nerve α-synuclein deposits. Neurology2017, 89(4), 318–326. [CrossRef]

- Stokholm, M.G.; Danielsen, E.H.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S.J.; Borghammer, P. Pathological α-synuclein in gastrointestinal tissues from prodromal Parkinson disease patients. Ann. Neurol.2016, 79(6), 940–949. [CrossRef]

- Kotzbauer, P.T.; Tu, Z.; Mach, R.H. Current status of the development of PET radiotracers for imaging alpha synuclein aggregates in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites. Clin. Transl. Imaging2017, 5(1), 3–14.

- Mavroudis, I.; Petridis, F.; Kazis, D. Cerebrospinal fluid, imaging, and physiological biomarkers in dementia with Lewy bodies. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen.2019, 34(7–8), 421–432. [CrossRef]

- Vrillon, A.; Bousiges, O.; Götze, K.; et al. Plasma biomarkers of amyloid, tau, axonal, and neuroinflammation pathologies in dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Res. Ther.2024, 16(1), 146. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Bautista, C.; Bolsewig, K.; Gonzalez, M.C.; et al. The association between plasma and MRI biomarkers in dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Res. Ther.2025, 17(1), 197. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Chen, W.; Xu, W.; et al. Neurofilament light chain in cerebrospinal fluid and blood as a biomarker for neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis.2019, 72(4), 1353–1361. [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, M.V.; Ribeiro, F.C.; Santos, L.E.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurotransmitters, cytokines, and chemokines in Alzheimer's and Lewy body diseases. J. Alzheimers Dis.2021, 82(3), 1067–1074. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, B.; Lautner, R.; Andreasson, U.; et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol.2016, 15(7), 673–684. [CrossRef]

- Janelidze, S.; Mattsson, N.; Palmqvist, S.; et al. Plasma P-tau181 in Alzheimer's disease: relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer's dementia. Nat. Med.2020, 26(3), 379–386. [CrossRef]

- Savica, R.; Murray, M.E.; Persson, X.M.; et al. Plasma sphingolipid changes with autopsy-confirmed Lewy body or Alzheimer's pathology. Alzheimers Dement. (Amst.)2016, 3, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Lerche, S.; Wurster, I.; Valente, E.M.; et al. CSF d18:1 sphingolipid species in Parkinson disease and dementia with Lewy bodies with and without GBA1 variants. NPJ Parkinsons Dis.2024, 10(1), 198. [CrossRef]

- Miglis, M.G.; Adler, C.H.; Antelmi, E.; et al. Biomarkers of conversion to α-synucleinopathy in isolated rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder. Lancet Neurol.2021, 20(8), 671–684. [CrossRef]

- Moussaud, S.; Jones, D.R.; Moussaud-Lamodière, E.L.; Delenclos, M.; Ross, O.A.; McLean, P.J. Alpha-synuclein and tau: teammates in neurodegeneration? Mol. Neurodegener.2014, 9, 43. [CrossRef]

- Gomperts, S.N. Lewy body dementias: dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson disease dementia. Continuum (Minneap Minn)2016, 22(2), 435–463. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, K.Y.; Bhoopatiraju, S.; Silverglate, B.D.; Grossberg, G.T. Biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease: A state of the art review. Biomark. Neuropsychiatry2023, 9, 100074. [CrossRef]

- Hely, M.A.; Reid, W.G.; Adena, M.A.; Halliday, G.M.; Morris, J.G. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson's disease: the inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov. Disord.2008, 23(6), 837–844. [CrossRef]

- Aarsland, D.; Andersen, K.; Larsen, J.P.; Lolk, A.; Kragh-Sørensen, P. Prevalence and characteristics of dementia in Parkinson disease: an 8-year prospective study. Arch. Neurol.2003, 60(3), 387–392. [CrossRef]

- Emre, M.; Aarsland, D.; Brown, R.; et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord.2007, 22(12), 1689–1707. [CrossRef]

- Savica, R.; Knopman, D.S. Dementia with Lewy bodies. In: Schapira, A.; Wszolek, Z.; Dawson, T.M.; Wood, N., Eds. Neurodegeneration; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Zardini Buzatto, A.; Tatlay, J.; Bajwa, B.; et al. Comprehensive serum lipidomics for detecting incipient dementia in Parkinson's disease. J. Proteome Res.2021, 20(8), 4053–4067. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.; Jacquemin, C.; Villain, N.; Fenaille, F.; Lamari, F.; Becher, F. Mass spectrometry for neurobiomarker discovery: the relevance of post-translational modifications. Cells2022, 11(8), 1279. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, A.W.; Fauvet, B.; Moniatte, M.; Lashuel, H.A. Alpha-synuclein post-translational modifications as potential biomarkers for Parkinson disease and other synucleinopathies. Mol. Cell. Proteomics2013, 12(12), 3543–3558. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.P.; Walker, D.E.; Goldstein, J.M.; et al. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J. Biol. Chem.2006, 281(40), 29739–29752. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Sampathu, D.M.; Kwong, L.K.; et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science2006, 314(5796), 130–133. [CrossRef]

- Wesseling, H.; Mair, W.; Kumar, M.; et al. Tau PTM profiles identify patient heterogeneity and stages of Alzheimer's disease. Cell2020, 183(6), 1699–1713.e13. [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Maetzler, W.; Haughey, N.J.; et al. Plasma ceramide and glucosylceramide metabolism is altered in sporadic Parkinson’s disease and associated with cognitive impairment: a pilot study. PLoS One2013, 8(9), e73094. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. Associations between plasma ceramides and cognitive and neuropsychiatric manifestations in Parkinson's disease dementia. J. Neurol. Sci.2016, 370, 82–87. [CrossRef]

- Galper, J.; Mori, G.; McDonald, G.; et al. Prediction of motor and non-motor Parkinson's disease symptoms using serum lipidomics and machine learning: a 2-year study. NPJ Parkinsons Dis.2024, 10(1), 123. [CrossRef]

- Avisar, H.; Guardia-Laguarta, C.; Area-Gomez, E.; et al. Lipidomics prediction of Parkinson’s disease severity: a machine-learning analysis. J. Parkinsons Dis.2021, 11(3), 1141–1155. [CrossRef]

- Raz, L.; Knoefel, J.; Bhaskar, K. The neuropathology and cerebrovascular mechanisms of dementia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.2016, 36(1), 172–186. [CrossRef]

- Peet, B.T.; Spina, S.; Mundada, N.; La Joie, R. Neuroimaging in frontotemporal dementia: heterogeneity and relationships with underlying neuropathology. Neurotherapeutics2021, 18(2), 728–752. [CrossRef]

- Erkkinen, M.G.; Kim, M.O.; Geschwind, M.D. Clinical neurology and epidemiology of the major neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.2018, 10(4), a033118. [CrossRef]

- Urso, D.; Giannoni-Luza, S.; Brayne, C.; et al. Incidence and prevalence of frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol.2025, e253307. [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J.; Ahern, E.G.M.; Logan, B.; et al. Factors associated with true-positive and false-positive diagnoses of behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia in 100 consecutive referrals from specialist physicians. Eur. J. Neurol.2025, 32(1), e70036. [CrossRef]

- Rohrer, J.D.; Guerreiro, R.; Vandrovcova, J.; et al. The heritability and genetics of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology2009, 73(18), 1451–1456. [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.M.; Falcone, D.; Suh, E.; et al. Development and validation of pedigree classification criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration. JAMA Neurol.2013, 70(11), 1411–1417. [CrossRef]

- DeJesus-Hernandez, M.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Boeve, B.F.; et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron2011, 72(2), 245–256. [CrossRef]

- Renton, A.E.; Majounie, E.; Waite, A.; et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron2011, 72(2), 257–268. [CrossRef]

- Lashley, T.; Rohrer, J.D.; Mead, S.; Revesz, T. An update on clinical, genetic and pathological aspects of frontotemporal lobar degenerations. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol.2015, 41(7), 858–881. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.M.; Hodges, J.R.; Piguet, O. Behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia: recent advances in the diagnosis and understanding of the disorder. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.2021, 1281, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Bott, N.T.; Radke, A.; Stephens, M.L.; Kramer, J.H. Frontotemporal dementia: diagnosis, deficits and management. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag.2014, 4(6), 439–454. [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, D.; de Vugt, M.E.; Bakker, C.; et al. Time to diagnosis in young-onset dementia as compared with late-onset dementia. Psychol. Med.2013, 43(2), 423–432. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Lv, X.; Tuerxun, M.; et al. Delayed help seeking behavior in dementia care: preliminary findings from the Clinical Pathway for Alzheimer's Disease in China (CPAD) study. Int. Psychogeriatr.2016, 28(2), 211–219. [CrossRef]

- Gendron, T.F.; Heckman, M.G.; White, L.J.; et al. Comprehensive cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of plasma neurofilament light across FTD spectrum disorders. Cell Rep. Med.2022, 3(4), 100607. [CrossRef]

- Katisko, K.; Cajanus, A.; Huber, N.; et al. GFAP as a biomarker in frontotemporal dementia and primary psychiatric disorders: diagnostic and prognostic performance. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry2021, 92(12), 1305–1312. [CrossRef]

- Chouliaras, L.; Thomas, A.; Malpetti, M.; et al. Differential levels of plasma biomarkers of neurodegeneration in Lewy body dementia, Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia and progressive supranuclear palsy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry2022, 93(6), 651–658. [CrossRef]

- Ntymenou, S.; Tsantzali, I.; Kalamatianos, T.; et al. Blood biomarkers in frontotemporal dementia: review and meta-analysis. Brain Sci.2021, 11(2), 244. [CrossRef]

- Liampas, I.; Kyriakoulopoulou, P.; Karakoida, V.; et al. Blood-based biomarkers in frontotemporal dementia: a narrative review. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2024, 25(21), 11838. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Tortosa, E.; Agüero-Rabes, P.; Ruiz-González, A.; et al. Plasma biomarkers in the distinction of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2025, 26(3), 1231. [CrossRef]

- Ambaw, Y.A.; Ljubenkov, P.A.; Singh, S.; et al. Plasma lipidome dysregulation in frontotemporal dementia reveals shared, genotype-specific, and severity-linked alterations. Alzheimers Dement.2025, 21(9), e70631. [CrossRef]

- Marian, O.C.; Matis, S.; Dobson-Stone, C.; et al. Reduced plasma hexosylceramides in frontotemporal dementia are a biomarker of white matter integrity. Alzheimers Dement. (Amst.)2025, 17(2), e70131. [CrossRef]

- Puljko, B.; Stojanović, M.; Ilic, K.; Kalanj-Bognar, S.; Mlinac-Jerkovic, K. Start me up: how can surrounding gangliosides affect sodium-potassium ATPase activity and steer towards pathological ion imbalance in neurons? Biomedicines2022, 10(7), 1518. [CrossRef]

- Vasques, J.F.; de Jesus Gonçalves, R.G.; da Silva-Junior, A.J.; et al. Gangliosides in nervous system development, regeneration, and pathologies. Neural Regen. Res.2023, 18(1), 81–86. [CrossRef]

- Schengrund, C.L. Gangliosides: glycosphingolipids essential for normal neural development and function. Trends Biochem. Sci.2015, 40(7), 397–406. [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, M.; Dehelean, L.; Munteanu, C.V.A.; Vukelić, Ž.; Zamfir, A.D. Assessment of ganglioside age-related and topographic specificity in human brain by Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem.2017, 521, 40–54. [CrossRef]

- Mlinac, K.; Bognar, S.K. Role of gangliosides in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Transl. Neurosci.2010, 1(4), 300–307. [CrossRef]

- Ica, R.; Petrut, A.; Munteanu, C.V.A.; et al. Orbitrap mass spectrometry for monitoring the ganglioside pattern in human cerebellum development and aging. J. Mass Spectrom.2020, 55(5), e4502. [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, M.; Petrica, L.; Clemmer, D.E.; Vukelić, Ž.; Zamfir, A.D. Gangliosides of human glioblastoma multiforme: a comprehensive mapping and structural analysis by ion mobility tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom.2021, 32(5), 1249–1257. [CrossRef]

- Ica, R.; Simulescu, A.; Sarbu, M.; Munteanu, C.V.A.; Vukelić, Ž.; Zamfir, A.D. High resolution mass spectrometry provides novel insights into the ganglioside pattern of brain cavernous hemangioma. Anal. Biochem.2020, 609, 113976. [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, M.; Clemmer, D.E.; Zamfir, A.D. Ion mobility mass spectrometry of human melanoma gangliosides. Biochimie2020, 177, 226–237. [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, A.D.; Fabris, D.; Capitan, F.; Munteanu, C.; Vukelić, Z.; Flangea, C. Profiling and sequence analysis of gangliosides in human astrocytoma by high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.2013, 405(23), 7321–7335. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N.; Toyoda, M.; Ishiwata, T. Gangliosides as signaling regulators in cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2021, 22(10), 5076. [CrossRef]

- Groux-Degroote, S.; Delannoy, P. Cancer-associated glycosphingolipids as tumor markers and targets for cancer immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2021, 22(11), 6145. [CrossRef]

- Cavdarli, S.; Delannoy, P.; Groux-Degroote, S. O-acetylated gangliosides as targets for cancer immunotherapy. Cells2020, 9(3), 741. [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, K.; Kato, K.; Yanagisawa, K. Ganglioside-mediated assembly of amyloid β-protein: roles in Alzheimer's disease. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci.2018, 156, 413–434. [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, K. GM1 ganglioside and Alzheimer’s disease. Glycoconj. J.2015, 32(3–4), 87–91. [CrossRef]

- Fukami, Y.; Ariga, T.; Yamada, M.; Yuki, N. Brain gangliosides in Alzheimer’s disease: increased expression of cholinergic neuron-specific gangliosides. Curr. Alzheimer Res.2017, 14(6), 586–591. [CrossRef]

- Ryckman, A.E.; Brockhausen, I.; Walia, J.S. Metabolism of glycosphingolipids and their role in the pathophysiology of lysosomal storage disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2020, 21(18), 6881. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Byeon, S.K.; Oglesbee, D.; Schultz, M.J.; Matern, D.; Pandey, A. A multiplexed targeted method for profiling of serum gangliosides and glycosphingolipids: application to GM2-gangliosidosis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.2024, 416(26), 5689–5699. [CrossRef]

- Boland, S.; Swarup, S.; Ambaw, Y.A.; et al. Deficiency of the frontotemporal dementia gene GRN results in gangliosidosis. Nat. Commun.2022, 13, 5924. [CrossRef]

- Kamp, P.E.; den Hartog Jager, W.A.; Maathuis, J.; de Groot, P.A.; de Jong, J.M.; Bolhuis, P.A. Brain gangliosides in the presenile dementia of Pick. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry1986, 49(8), 881–885. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.S.; Jary, E.; Pickford, R.; et al. Lipidomics analysis of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a scope for biomarker development. Front. Neurol.2018, 9, 104. [CrossRef]

- Marian, O.C.; Teo, J.D.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. Disrupted myelin lipid metabolism differentiates frontotemporal dementia caused by GRN and C9orf72 gene mutations. Acta Neuropathol. Commun.2023, 11(1), 52. [CrossRef]

- Arrant, A.E.; Roth, J.R.; Boyle, N.R.; Kashyap, S.N.; Hoffmann, M.Q.; Murchison, C.F.; Ramos, E.M.; Nana, A.L.; Spina, S.; Grinberg, L.T.; Miller, B.L.; Seeley, W.W.; Roberson, E.D. Impaired β-glucocerebrosidase activity and processing in frontotemporal dementia due to progranulin mutations. Acta Neuropathol. Commun.2019, 7(1), 218. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Phan, K.; Bhatia, S.; Pickford, R.; Fu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hodges, J.R.; Piguet, O.; Halliday, G.M.; Kim, W.S. Increased VLCFA-lipids and ELOVL4 underlie neurodegeneration in frontotemporal dementia. Sci. Rep.2021, 11(1), 21348. [CrossRef]

- Aqel, S.; Ahmad, J.; Saleh, I.; Fathima, A.; Al Thani, A.A.; Mohamed, W.M.Y.; Shaito, A.A. Advances in Huntington’s disease biomarkers: a 10-year bibliometric analysis and a comprehensive review. Biology2025, 14(2), 129. [CrossRef]

- Seeley, C.; Kegel-Gleason, K.B. Taming the Huntington's disease proteome: what have we learned? J. Huntingtons Dis.2021, 10(2), 239–257. [CrossRef]

- Peavy, G.M.; Jacobson, M.W.; Goldstein, J.L.; Hamilton, J.M.; Kane, A.; Gamst, A.C.; Lessig, S.L.; Lee, J.C.; Corey-Bloom, J. Cognitive and functional decline in Huntington's disease: dementia criteria revisited. Mov. Disord.2010, 25(9), 1163–1169. [CrossRef]

- Snowden, J.S.; Craufurd, D.; Thompson, J.; Neary, D. Psychomotor, executive, and memory function in preclinical Huntington's disease. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol.2002, 24(2), 133–145. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.M.; Salmon, D.P.; Corey-Bloom, J.; et al. Behavioural abnormalities contribute to functional decline in Huntington's disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry2003, 74(1), 120–122. [CrossRef]

- McGarry, A.; Gaughan, J.; Hackmyer, C.; Lovett, J.; Khadeer, M.; Shaikh, H.; Pradhan, B.; Ferraro, T.N.; Wainer, I.W.; Moaddel, R. Cross-sectional analysis of plasma and CSF metabolomic markers in Huntington's disease for participants of varying functional disability: a pilot study. Sci. Rep.2020, 10(1), 20490. [CrossRef]

- McGarry, A.; Gaughan, J.; Hackmyer, C.; et al. Author correction: Cross-sectional analysis of plasma and CSF metabolomic markers in Huntington's disease for participants of varying functional disability: a pilot study. Sci. Rep.2021, 11(1), 9947. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.; Demarais, N.J.; Faull, R.L.M.; Grey, A.C.; Curtis, M.A. An imaging mass spectrometry atlas of lipids in the human neurologically normal and Huntington's disease caudate nucleus. J. Neurochem.2021, 157(6), 2158–2172. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, G.R.; Saville, J.T.; Hancock, S.E.; Brown, S.H.J.; Jenner, A.M.; McLean, C.; Fuller, M.; Newell, K.A.; Mitchell, T.W. The long and the short of Huntington's disease: how the sphingolipid profile is shifted in the caudate of advanced clinical cases. Brain Commun.2021, 4(1), fcab303. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, G.R.; Hancock, S.E.; Brown, S.H.J.; Jenner, A.M.; Kreilaus, F.; Newell, K.A.; Mitchell, T.W. Cholesteryl ester levels are elevated in the caudate and putamen of Huntington's disease patients. Sci. Rep.2020, 10(1), 20314. [CrossRef]

- Maglione, V.; Marchi, P.; Di Pardo, A.; Lingrell, S.; Horkey, M.; Tidmarsh, E.; Sipione, S. Impaired ganglioside metabolism in Huntington's disease and neuroprotective role of GM1. J. Neurosci.2010, 30(11), 4072–4080. [CrossRef]

- Alpaugh, M.; Galleguillos, D.; Forero, J.; Morales, L.C.; Lackey, S.W.; Kar, P.; Di Pardo, A.; Holt, A.; Kerr, B.J.; Todd, K.G.; Baker, G.B.; Fouad, K.; Sipione, S. Disease-modifying effects of ganglioside GM1 in Huntington's disease models. EMBO Mol. Med.2017, 9(11), 1537–1557. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, L.M.; Rodrigues, F.B.; Johnson, E.B.; Wijeratne, P.A.; De Vita, E.; Alexander, D.C.; Palermo, G.; Czech, C.; Schobel, S.; Scahill, R.I.; Heslegrave, A.; Zetterberg, H.; Wild, E.J. Evaluation of mutant huntingtin and neurofilament proteins as potential markers in Huntington's disease. Sci. Transl. Med.2018, 10(458), eaat7108. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, L.M.; Rodrigues, F.B.; Blennow, K.; Durr, A.; Leavitt, B.R.; Roos, R.A.C.; Scahill, R.I.; Tabrizi, S.J.; Zetterberg, H.; Langbehn, D.; Wild, E.J. Neurofilament light protein in blood as a potential biomarker of neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease: a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet Neurol.2017, 16(8), 601–609. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, L.M.; Rodrigues, F.B.; Blennow, K.; et al. Corrections. Neurofilament light protein in blood as a potential biomarker of neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease: a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet Neurol.2017, 16(9), 683. [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, S.J.; Schobel, S.; Gantman, E.C.; Mansbach, A.; Borowsky, B.; Konstantinova, P.; Mestre, T.A.; Panagoulias, J.; Ross, C.A.; Zauderer, M.; Mullin, A.P.; Romero, K.; Sivakumaran, S.; Turner, E.C.; Long, J.D.; Sampaio, C.; Huntington's Disease Regulatory Science Consortium (HD-RSC). A biological classification of Huntington's disease: the Integrated Staging System. Lancet Neurol.2022, 21(7), 632–644. [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani-Jahromi, M.; Poudel, G.R.; Razi, A.; Abeyasinghe, P.M.; Paulsen, J.S.; Tabrizi, S.J.; Saha, S.; Georgiou-Karistianis, N. Prognostic enrichment for early-stage Huntington's disease: an explainable machine learning approach for clinical trial. Neuroimage Clin.20242, 43, 103650. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, S.; Chithambaram, T.; Krishnan, N.R.; Vincent, D.R.; Kaliappan, J.; Srinivasan, K. Exploring Huntington's disease diagnosis via artificial intelligence models: a comprehensive review. Diagnostics (Basel)2023, 13(23), 3592. [CrossRef]

- Meneses, A.; Koga, S.; O’Leary, J.; Dickson, D.W.; Bu, G.; Zhao, N. TDP-43 pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener.2021, 16, 84. [CrossRef]

- Knopman, D.S.; Parisi, J.E.; Boeve, B.F.; Cha, R.H.; Apaydin, H.; Salviati, A.; Edland, S.D.; Rocca, W.A. Vascular dementia in a population-based autopsy study. Arch. Neurol.2003, 60(4), 569–575. [CrossRef]

- Buciuc, M.; Whitwell, J.L.; Boeve, B.F.; Ferman, T.J.; Graff-Radford, J.; Savica, R.; Kantarci, K.; Fields, J.A.; Knopman, D.S.; Petersen, R.C.; Parisi, J.E.; Murray, M.E.; Dickson, D.W.; Josephs, K.A. TDP-43 is associated with a reduced likelihood of rendering a clinical diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies in autopsy-confirmed cases of transitional/diffuse Lewy body disease. J. Neurol.2020, 267(5), 1444–1453. [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Pan, K.Y.; Xu, H.; Qi, X.; Buchman, A.S.; Bennett, D.A.; Xu, W. Association of cardiovascular risk burden with risk of dementia and brain pathologies: a population-based cohort study. Alzheimers Dement.20210, 17(12), 1914–1922. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; Fox, N.C.; Ferri, C.P.; Gitlin, L.N.; Howard, R.; Kales, H.C.; Kivimäki, M.; Larson, E.B.; Nakasujja, N.; Rockwood, K.; Samus, Q.; Mukadam, N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet2024, 404(10452), 572–628. [CrossRef]

- Leocadi, M.; Canu, E.; Paldino, A.; Agosta, F.; Filippi, M. Awareness impairment in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia: a systematic MRI review. J. Neurol.2023, 270(4), 1880–1907. [CrossRef]

- Rowley, P.A.; Samsonov, A.A.; Betthauser, T.J.; Pirasteh, A.; Johnson, S.C.; Eisenmenger, L.B. Amyloid and Tau PET imaging of Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative conditions. Semin. Ultrasound CT MR2020, 41(6), 572–583. [CrossRef]

- Manjavong, M.; Kang, J.M.; Diaz, A.; Ashford, M.T.; Eichenbaum, J.; Aaronson, A.; Miller, M.J.; Mackin, S.; Tank, R.; Weiner, M.; Nosheny, R. Performance of plasma biomarkers combined with structural MRI to identify candidate participants for Alzheimer's disease-modifying therapy. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis.2024, 11(5), 1198–1205. [CrossRef]

- Mok, V.C.T.; Cai, Y.; Markus, H.S. Vascular cognitive impairment and dementia: mechanisms, treatment, and future directions. Int. J. Stroke2024, 19(8), 838–856. [CrossRef]

- Chang Wong, E.; Chang Chui, H. Vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Continuum (Minneap Minn)2022, 28(3), 750–780. [CrossRef]

- Tisher, A.; Salardini, A. A comprehensive update on treatment of dementia. Semin. Neurol.2019, 39(2), 167–178. [CrossRef]

- Kapasi, A.; James, B.D.; Yu, L.; Sood, A.; Arvanitakis, Z.; Bennett, D.A.; Boyle, P.; Schneider, J.A. Mixed pathologies and cognitive outcomes in persons considered for anti-amyloid treatment eligibility assessment: a community-based study. Neurology2025, 105(5), e214004. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-M. Vascular dementia: from pathophysiology to therapeutic frontiers. J. Clin. Med.2025, 14, 6611. [CrossRef]

- Alrouji, M.; Alshammari, M.S.; Tasqeeruddin, S.; Shamsi, A. Interplay between aging and tau pathology in Alzheimer's disease: mechanisms and translational perspectives. Antioxidants (Basel)2025, 14(7), 774. [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Wasnik, S.; Shandilya, C.; Srivastava, V.; Khan, S.; Singh, K.K. Pathogenic synergy: dysfunctional mitochondria and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases associated with aging. Front. Aging2025, 6, 1615764. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Ying, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, T.; Yoon, S.; Zheng, Q.; Fang, Y.; Yang, D.; Hua, F. The involvement of lactosylceramide in central nervous system inflammation related to neurodegenerative disease. Front. Aging Neurosci.2021, 13, 691230. [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, C.E.; Kimble, L.; Bayoumy, S.; Bolsewig, K.; Burtscher, F.; Coppens, S.; Das, S.; Gogishvili, D.; Fernandes Gomes, B.; Gómez de San José, N.; Mavrina, E.; Meda, F.J.; Mohaupt, P.; Mravinacová, S.; Waury, K.; Wojdała, A.L.; Abeln, S.; Chiasserini, D.; Hirtz, C.; Gaetani, L.; Vermunt, L.; Bellomo, G.; Halbgebauer, S.; Lehmann, S.; Månberg, A.; Nilsson, P.; Otto, M.; Vanmechelen, E.; Verberk, I.M.W.; Willemse, E.; Zetterberg, H.; MIRIADE consortium. Methods to discover and validate biofluid-based biomarkers in neurodegenerative dementias. Mol. Cell Proteomics2023, 22(10), 100629. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.; Ashrafi, N.; Ashrafi, R.; Akyol, S.; Saiyed, N.; Kerševičiūtė, I.; Gabrielaite, M.; Gordevicius, J.; Graham, S.F. Lipid profiling of Parkinson’s disease brain highlights disruption in lysophosphatidylcholines, and triacylglycerol metabolism. npj Parkinsons Dis.2025, 11, 159. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, A.R. Mass spectrometry-based analysis of lipid involvement in Alzheimer’s disease pathology—a review. Metabolites2022, 12, 510. [CrossRef]

- Cilento, E.M.; Jin, L.; Stewart, T.; Shi, M.; Sheng, L.; Zhang, J. Mass spectrometry: a platform for biomarker discovery and validation for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. J. Neurochem.2019, 151(4), 397–416. [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.M.; Wang, Y.; Duan, X.; Wenk, M.R.; Kalaria, R.N.; Chen, C.P.; Lai, M.K.; Shui, G. Brain lipidomes of subcortical ischemic vascular dementia and mixed dementia. Neurobiol. Aging2014, 35(10), 2369–2381. [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, T.F.E.; Krestensen, K.K.; Mohren, R.; Vandenbosch, M.; De Vleeschouwer, S.; Heeren, R.M.A.; Cuypers, E. MALDI-MSI-LC-MS/MS workflow for single-section single step combined proteomics and quantitative lipidomics. Anal. Chem.2024, 96(10), 4266–4274. [CrossRef]

- Noel, A.; Ingrand, S.; Barrier, L. Ganglioside and related-sphingolipid profiles are altered in a cellular model of Alzheimer's disease. Biochimie2017, 137, 158–164. [CrossRef]

- Chua, X.Y.; Torta, F.; Chong, J.R.; Venketasubramanian, N.; Hilal, S.; Wenk, M.R.; Chen, C.P.; Arumugam, T.V.; Herr, D.R.; Lai, M.K.P. Lipidomics profiling reveals distinct patterns of plasma sphingolipid alterations in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Alzheimers Res. Ther.2023, 15(1), 214. [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, V.C.; Lauer, A.A.; Haupenthal, V.; Stahlmann, C.P.; Mett, J.; Grösgen, S.; Hundsdörfer, B.; Rothhaar, T.; Endres, K.; Eckhardt, M.; Hartmann, T.; Grimm, H.S.; Grimm, M.O.W. A bidirectional link between sulfatide and Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Chem. Biol.2024, 31(2), 265–283.e7. [CrossRef]

- Reza, S.; Ugorski, M.; Suchański, J. Glucosylceramide and galactosylceramide, small glycosphingolipids with significant impact on health and disease. Glycobiology2021, 31(11), 1416–1434. [CrossRef]

- Pujol-Lereis, L.M. Alteration of sphingolipids in biofluids: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2019, 20(14), 3564. [CrossRef]

- Koal, T.; Klavins, K.; Seppi, D.; Kemmler, G.; Humpel, C. Sphingomyelin SM(d18:1/18:0) is significantly enhanced in cerebrospinal fluid samples dichotomized by pathological amyloid-β42, tau, and phospho-tau-181 levels. J. Alzheimers Dis.2015, 44(4), 1193–1201. [CrossRef]

- Montine, T.J.; Morrow, J.D. Fatty acid oxidation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol.2005, 166(5), 1283–1289. [CrossRef]

| Disorder Features |

Dementia of Alzheimer’s Type (AD) | Dementia with Lewy body (DLB) | Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) | Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) | Huntington's disease (HD) | Mixed dementia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Presenile or senile | Senile | Presenile | Late onset, usually after Parkinson's diagnosis | Presenile | Senile onset |

| Age at diagnosis | < 65s or > 65s | 70s, but range 50s–80s | 40s and early 60s | >70s | 30s or 40s | >65 |

| Patient profile | Predominantly female | Slight male predominance | Predominantly male | Predominantly male, in early onset cases | Equal in males and females (autosomal dominant inheritance) | No gender preference |

| Brain Abnormalities | Accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles throughout the brain, granulovacuolar degeneration in hippocampus | α-synuclein aggregation in cortical and subcortical Lewy bodies; often coexists with Alzheimer’s pathology | Buildup of abnormal tau and TDP-43 proteins in the frontal and temporal lobes | Accumulation of alpha-synuclein protein in Lewy bodies | Caused by a specific inherited gene mutation leading to neuron degeneration | Accumulation of tau and amyloid plaques, blood vessel damage and reduced blood flow |

| Cerebral damage | Diffuse cerebral atrophy, particularly in the posterior temporal hippocampus and parietal areas | Widespread Lewy body pathology affecting cortex, limbic regions, and brainstem; variable cortical atrophy | Severe atrophy of the frontal and anterior temporal lobes | Atrophy in subcortical regions and cortical Lewy body pathology | Neuronal loss in caudate nucleus and putamen | Combination of Alzheimer’s pathology and vascular lesions |

| Prominent symptom | Memory dysfunction | Fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, and parkinsonism (core clinical triad) | Personality and language disturbances | Impaired attention, executive dysfunction, memory issues | Cognitive decline with behavioral disturbances | Memory loss, cognitive decline, executive dysfunction |

| Motor signs | Less common | Parkinsonian motor features (rigidity, bradykinesia, tremor), usually milder than idiopathic Parkinson’s at onset | More common (in FTD with motor neuron disease). May include tremors, muscle stiffness, muscle spasms, poor coordination, swallowing difficulties, muscle weakness | Frequent; rigidity, bradykinesia, tremors | Chorea, dystonia, impaired voluntary movements | May include vascular-related motor symptoms (gait disturbance, weakness) |

| Visuospatial abilities | Severely impaired | Markedly impaired | Preserved | Moderately impaired | Impaired | Often impaired |

| Language problems | In late stages individuals lose the ability to understand or formulate words in a spoken sentence, or speaking is very hesitant, labored or ungrammatical | Mild word-finding difficulty possible, but language relatively preserved compared to Alzheimer’s and FTD | Trouble thinking of the right word or remembering names; Less difficulty making sense when they speak, understanding the speech of others, or reading | Word-finding difficulties, reduced fluency | Speech becomes slurred, eventual mutism | Variable; may mirror Alzheimer’s type difficulties |

| Mood | Depression, anxiety, suspiciousness | depression, anxiety, apathy as in Alzheimer's, plus anxiety secondary to confusional states | Marked irritability, lack of guilt, alexithymia (difficulties in understanding, processing, or describing emotions), euphoria, apathy | Depression, anxiety, apathy | Depression, irritability, aggression, apathy | Depression, anxiety, apathy |

| Intellectual deficit | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Psychotic features | Usually have delusion of misidentification or prejudice secondary to memory impairment type and usually occur in the middle or late stage | Prominent visual hallucinations, delusions | Rare persecutory delusions, usually jealous, somatic, religious and bizarre behaviours | Visual hallucinations, paranoid delusions | Psychosis may occur in later stages | Possible delusions and hallucinations |

| Appetite, dietary change | Less common: anorexia and weight loss | Weight loss may occur | Increased appetite, carbohydrate craving 80%, weight gain | Weight loss more common | Weight loss despite high caloric intake | Variable; can include weight loss or gain |

| Prognosis | Progresses to death in 11.8 ± 0.6 years | Average survival 5–8 years after diagnosis | Progresses to death in 8.7 ± 1.2 years | Average survival 5–10 years after dementia onset | Survival 15–20 years after onset | Variable; progression faster than single dementia types |

| Cause of death | Aspiration pneumonia secondary to swallowing disorders | Aspiration pneumonia, complications of immobility, and infections | Physical changes that can cause skin, urinary tract and/or lung infections | Complications from immobility, aspiration pneumonia | Complications from immobility, infections, aspiration pneumonia | Cardiovascular disease, pneumonia, infections |

| Platform / Workflow | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC MS/MS with Orbitrap/quadrupol time of flight (QTOF) | Chromatographic separation of glycolipids; high-resolution MS/MS for structural information | Quantitative, robust, reduces isobaric interference; structural info on fatty acyl chains; sensitive for cerebrospinal fluid(CSF)/plasma; suitable for both discovery (untargeted) and validation (targeted selected reaction monitoring, SRM) | Requires optimized chromatography for polar glycans; some isomers need derivatization or specialized columns | Discovery (by untargeted high resolution LC MS) and validation (by targeted SRM) of candidate glycolipids |

| Shotgun Lipidomics (Direct infusion, Orbitrap/triple-TOF) | Rapid, high-throughput profiling without LC | Broad coverage; quick surveys; minimal preparation steps | Ion suppression; poor isomer/isobar separation; less quantitative | Initial screening before LC-MS validation |

| MALDI MSI | Spatial mapping of glycolipids on tissue; moderate to high resolution | Links molecular and anatomical information; enables regional distribution analysis; improved sensitivity with on-tissue derivatization and high resolution analyzers | Lower absolute quantitation than LC MS; matrix/analyte suppression | Mapping glycolipids in brain tissue; correlating with plaques, vessels, microinfarcts |

| DESI MSI and SIMS Imaging | Ambient ionization (DESI); ultra-high resolution imaging (SIMS) | Minimal sample preparation (DESI); sub-micron resolution (SIMS); powerful when combined with immunohistochemistry (IHC)/ fluorescence |

SIMS historically limited mass range and fragmentation; complex data analysis | Subcellular mapping of glycolipids; complementary spatial lipidomics |

| IMS MS | Separates isomeric/isobaric species by shape/size | Resolves gangliosides and their isomers in native complex and mixtures; improves confidence in structural identification; boosts discovery | Requires specialized instrumentation | Discovery of novel glycolipid biomarkers; detailed structural assignment of glycoforms with or without various modifications |

| Targeted Derivatization and Glycan-Specific Workflows | Chemical modifications (permethylation, sialic acid methylation); specialized columns | Improves chromatographic behavior and MS sensitivity for glycans; resolves isomers | Extra sample preparation; workflow complexity | Quantifying disease-relevant GG isomers |

| Quantitative MSI and LC MS Hybrid | Combines on-tissue MSI with microextraction and LC-MS/MS | Provides spatial localization and validated concentration data; emerging gold standard | Complex, multi-step workflow | Linking tissue glycolipid changes to histopathology; anatomical and quantitative mapping |

| Glycolipid Class | Representative Species | Why Relevant to Mixed Dementia | Representative Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gangliosides (mono-/di-/tri-sialo) | GM1 (d18:1/18:0); GM2; GM3 (d18:1/16:0; d18:1/18:0); GD1a; GD1b; GT1b | Abundant in neuronal membranes and synapses; altered sialylation and acyl chain composition reflect membrane degradation, plaque association, and local inflammatory/ degenerative processes; GM3 and GM2 increased in near plaques and in white matter in several MS studies | Wang et al. [67] |

| Sulfatides (sulfated galactocerebrosides) | ST(d18:1/24:0) | Enriched in myelin; early sulfatide loss associated with AD and with white matter/myelin injury in vascular disease; sensitive to myelin degradation in mixed pathology | Zimmer et al. [229] |

| Galactosylceramides / Glucosylceramides (GalCer, GlcCer) | GalCer(d18:1/24:0); GlcCer species | Core myelin glycosphingolipids; shifts indicate demyelination and altered glycosphingolipid metabolism in ischemic white matter and mixed dementia | Reza et al. [230] |

| Ceramides (bioactive sphingolipids) | Cer(d18:1/16:0); Cer(d18:1/24:1) | Products of sphingomyelin breakdown; elevated ceramides associate with neurodegeneration, inflammation and vascular risk; link cell stress to apoptosis and promote Aβ production | Pujol-Lereis et al. [231] |

| Sphingomyelins (SM) | SM(d18:1/18:0); SM(36:1) | Structural membrane lipids; sphingomyelin/ceramide ratio changes indicate membrane changes and myelin injury; altered in mixed dementia tissue studies | Koal et al. [232] |

| Ganglioside Degradation Intermediates | GM2; lactosylceramides (LacCer) | Reflect increased glycosidase activity and disrupted catabolism around plaques and ischemic zones; accumulation indicates lysosomal/ autophagy perturbation common to mixed dementia |

Wang et al. [67] |

| Glycolipid Oxidation & Truncated Forms | Oxidized ceramides; truncated ganglioside species | Markers of oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation from ischemia/inflammation; likely elevated in tissue adjacent to microinfarcts and plaques | Montine et al. [233] |

| Type of dementia | Type | Sample | MS Platform | Glycolipid Findings | Study / Year – |

| AD | APP/PS1 transgenic mice | Brain tissue | MALDI MSI | ↓ShexCers and CroPIn in cerebral cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum | Zhang et al. 2024 [87] |

| APP/PS1 transgenic mice | Brain tissue | MALDI MSI | GM1 and GD1a modificationin white and grey matter ↑GM2 and GM3 in cortex and dentate gyrus, GM3 in Aβ plaques |

Wang et al. 2025 [67] | |

| APP/PS1 transgenic mice | Brain tissue | MALDI-IHC MSI | ↑GD3 and GD2 in hippocampal plaques, GM3 (38:1);O2 in cortical plaques GM3 (36:1);O2 and GM2 (36:1);O2 plaque-defining GGs |

Good et al. 2025 [96] | |

| APP21 transgenic Fischer rats | Brain tissue | MALDI MSI | ↑GM1, GM2, GM3, especially GM3 d18:1, d20:1/d18:1 ratio ↓complex GGs |

Caughlin et al. 2018 [94] | |

| TgAPPArcSwetransgenic mice | Brain tissue | TOF SIMS + MALDI MSI | ↑GM3 (C18:0) and GM2 (C18:0) inAβ plaque-like structures ↓[ST d18:1/24:0-H]⁻ and [ST d18:1/22:0-H]⁻ |

Michno et al. 2019 [79] | |

| APPswe/PS1dE9 (APP/PS1) | Hippocampal tissue | UHPLC-MS/MS | ↑TGs, CEs,PEs, PCs ↓MGDGs, HexCers |

Xiao et al. 2025 [69] | |

| APPswe/PS1dE9 | Hippocampal tissue | LC | di-O-Ac-GT1a (d36:1), O-Ac-GD1b (d36:1) and O-Ac-GD1b (d36:0) – biomarkers O-Ac-GT1a (d36:2) non-progressive biomarker |

Li et al. 2022 [91] | |

| 5xFAD mouse | Brain tissue | MALDI IMS | ↑GMs C18:1 in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus, GMs C20:1 in the molecular layer along the entorhinal hippocampal pathway Co-localized GM3 (d18:1/18:0), GM2 (d18:1/18:0), GM1 (d18:1/18:0), with Aβ peptides in the subiculum |

Kaya et al. 2020 [95] | |

| Dual injured mice (Aβ+stroke), stroke alone and Aβ alone | Brain tissue | MALDI IMS |

|

Caughlin et al. 2015 [97] | |

| AD patients | Hippocampal tissue | MALDI IMS | Loss of GM1 (d20:1/C18:0) at the edge of the dentate gyrus ↓GM1 (d20:1/C18:0) to GM1 (d18:1/C18:0) ratio in the outer molecular layer of the dentate gyrus No differences in other hippocampal subregions or in total hippocampal lipid content |

Hirano-Sakamaki et al. 2015 [73] | |

| AD patients | Serum | LC-MS | ↑CE (16:3) and GM3 (d18:1/9Z-18:1) – early clinical prediction and severity correlation | Zhang et al. 2021[89] | |

| AD patients | Brain tissue | MALDI MSI | GM3 and GM1 co-localizes with Aβ plaques ↓GM1 d20:1 to GM1 d18:1 in the molecular leyer, dentate gyrus and entorhinal cortex |

Ollen-Bittle et al. 2024 [86] | |

| AD patients | Brain tissue | TLC Blot/MALDI TOF MS | ↑GGs containing d18:1 compared to PD and control ↓GD1b and GT1b compared to PD and control |

Taki et al. 2012 [93] | |

| AD, VD and control patients | Serum | HPTLC + ELISA | ↑-GM1, -GD1b, -GT1b, -GQ1b, and anti-GQ1bα IgM type antibodies in AD and VD ↑ -GQ1b, -GQ1bα and anti-GT1b IgGtypeantibodies in AD |

Ariga et al. 2013 [70] | |

| DBL | Clinically diagnosed DLB | Plasma | untargeted UPLC–MS lipidomics + ML feature selection | sphingoid bases, ceramides, Hex1Cer differentially expressed in DLB vs controls and vs AD | Shen et al.2024 [53] |

| Autopsy-confirmed LB pathology | Plasma collected ~2 years before death | targeted LC-MS/MS | ↑HexCer/ceramide in both LB and AD groups; no significant difference between DLB and AD | Savica et al. 2016 [121] | |

| GBA1 variant and wild-type cohorts | CSF | targeted LC-MS/MS | no clear increase of Cer (d18:1/18:0), GlcCer (d18:1/18:0), SphM (d18:1/18:0), GlcSph (d18:1) and GalSph (d18:1); ↓GalSph and Cer vs controls/PD; no clear difference between GBA1 carriers and wild-type |

Lerche et al. 2024 [122] | |

| PDD | Clinically diagnosed Parkinson’s disease with dementia | Plasma | Targeted LC–MS/MS | ↑ Plasma ceramides&glucosylceramides; higher levels associated with cognitive impairment | Mielke et al. 2013 [137] |

| Clinically diagnosed Parkinson’s disease with dementia | Plasma | Targeted HPLC–MS/MS | C24:1 negatively correlated with immediate/delayed recall; C14:0 with delayed recall/recognition; C22:0 with hallucinations, C20:0 with anxiety, C18:0 with sleep disturbances | Xing et al. 2016 [138] | |

| Longitudinally followed PD patients without baseline dementia | Serum | Untargeted LC–QTOF–MS lipidomics with multivariate models | ↑ 24 ceramides, 24 diacylglycerols, 17 triacylglycerols; ↓ phosphatidylcholines, bis(monoacyl)glycerophosphates, phosphatidylserines; 5-lipid panel predicted dementia with >95% accuracy | ZardiniBuzatto et al. 2021 [131] | |

| FTD | GRN-mutation | Cells & human brain | MS–based lipidomics | ↑GM1, GD3, GD1 ↓ BMP levels (progranulin deficiency → BMP loss → GG accumulation) |

Boland et al. 2022 [181] |

| Pick presenile dementia | Brain tissue | TLC | ↑GT1a and/or GD2 ↓GalNAc-GDla |

Kamp et al. 1986 [182] | |

| bvFTD |

Plasma | untargeted LC-MS | largely unchangedsphingolipid profile | Kim et al. 2018 [183] | |

| GRN/C9orf72 FTD Subtypes | Brain tissue | LC-MS lipidomics+ enzymatic assays | ↓myelin sphingolipids; FTD-GRN shows more severe loss; consistent with MRI | Marian et al. 2023 [184] | |

| Familial bvFTD | Plasma | LC-MS lipidomics | ↓HexCers, especially C22:0 GlcCer and GalCer; reductions correlate with MRI measures of white matter damage and disease duration | Marian et al. 2025 [162] | |

| GRN-FTD Subtype | Frontal gyrus tissue | targeted HPLC-MS and biochemical assays | ↓mature GCase protein; accumulation of improperly processed forms; reduced GCase activity. No overt accumulation of GCase substrates (GlcCer, GlcSph) in examined regions. |

Arrant et al. 2019 [185] | |

| Not specified | Superior frontal cortex | quantitative discovery LC-MS lipidomics | ↑ VLCFA-lipid species ↑ ELOVL4 enzyme |

He et al. 2021 [186] | |

| HD | Clinically diagnosed Huntington’s disease | Plasma & CSF | Untargeted UHPLC-MS metabolomics | Altered ceramides, hexosylceramides, sphingomyelins, phosphatidylcholines; correlated with Stroop and Verbal Fluency | McGarry et al. 2020 [192] |

| Clinically diagnosed Huntington’s disease | Post-mortem brain (caudate, cortex) | MALDI-IMS | Regional sphingolipid and phospholipid dysregulation; linked to executive and memory circuits | Hunter et al. 2021 [194] | |

| Advanced clinical cases of Huntington’s disease | Post-mortem caudate | LC-MS | Ceramide/sphingomyelin chain-length shift: loss of very-long-chain, enrichment of long-chain species | Phillips et al. 2021 [195] | |

| Huntington’s disease patient-derived cells and animal models | Cultured cells and mouse brain tissue | Targeted LC-MS/MS gangliosides | ↓ GM1 ganglioside; supplementation with exogenous GM1 improved motor and cognitive phenotypes | Maglione et al. 2010 [197]; Di Pardo et al. 2012 [36]; Alpaugh et al. 2017 [198] | |

| Mixed dementia | AD + vascular pathology | Brain tissue | lipid pathway / histochemical analyses (study did not report MS platform in file) | ↑GM2 and GM3 within and around amyloid plaques; increased GG degradation pathway activity in plaque regions | Wang et al. 2025 [67] |

| SIVD, mixed dementia | White and gray matter from temporal cortex | comparative LC-MS lipidomic | ↑GM3 and markers of membrane breakdown in mixed dementia white matter; pronounced alterations in sphingolipid, ceramides, SM, GlcCer and GalCer classes | Lam et al. 2014 [225] | |

| VD | Plasma | LC-MS/MS | ↓sphingolipid d16:1 in VaD; ↑sphingolipid d18:1 in AD; Cer d16:1/24:0, Cer d18:1/16:0, Hex2Cer d16:1/16:0, HexCer d18:1/18:0, SM d16:1/16:0, SM d16:1/20:0, SM d18:2/22:0 - higher sensitivity and specificity for classifying VaD. |

Chua et al. 2023 [228] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).