Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

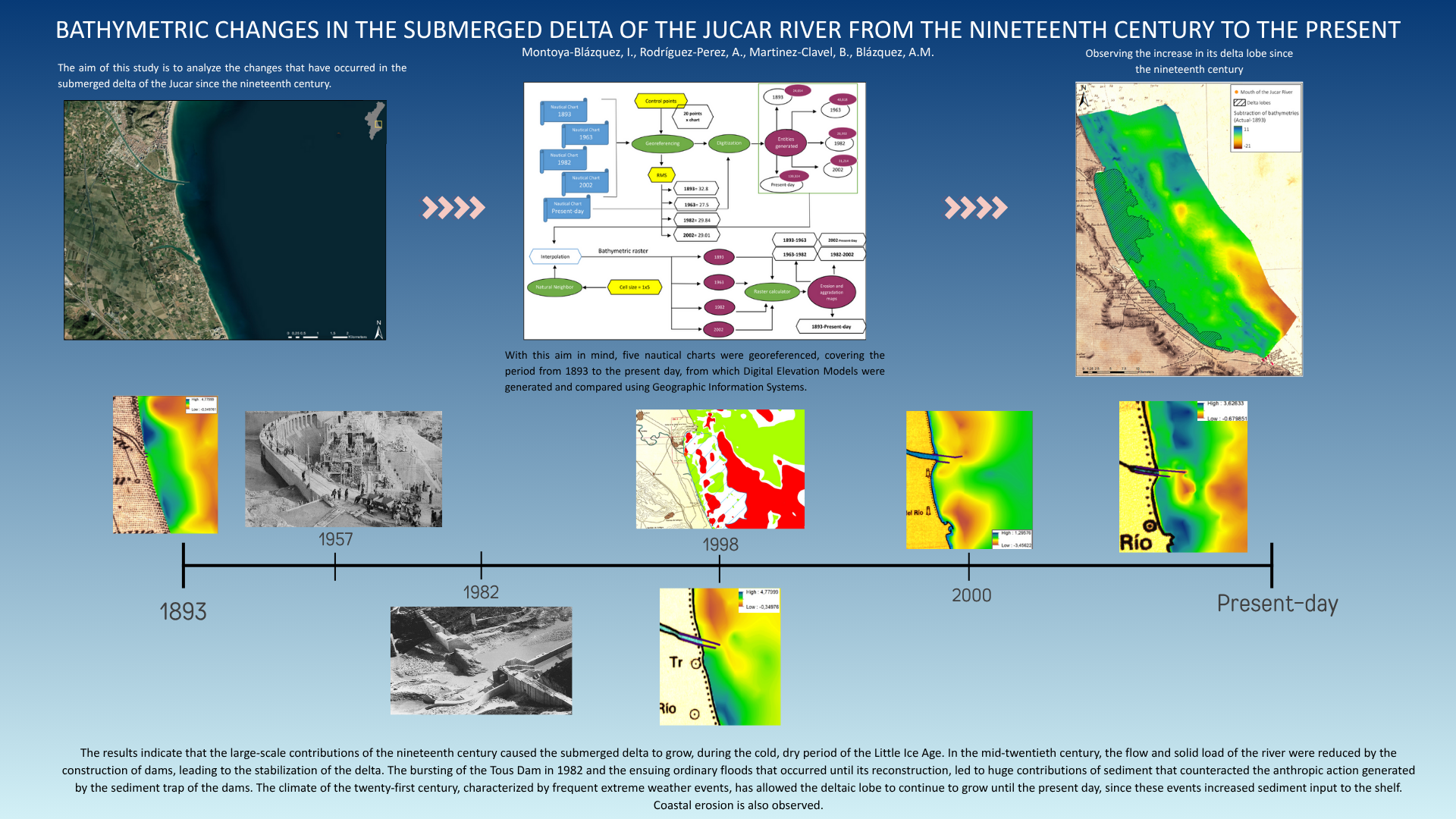

- To obtain a Digital Elevation Model from the digitized bathymetry of each of the nautical charts.

- To evaluate the impact of the lamination of the Jucar since the 1950s on the submerged delta.

- To analyze the influence of the 1982 flood, the most important during the period covered by this study, on the submerged Jucar Delta.

- To understand how global warming and its extraordinary storms could influence the sedimentation of the Jucar River.

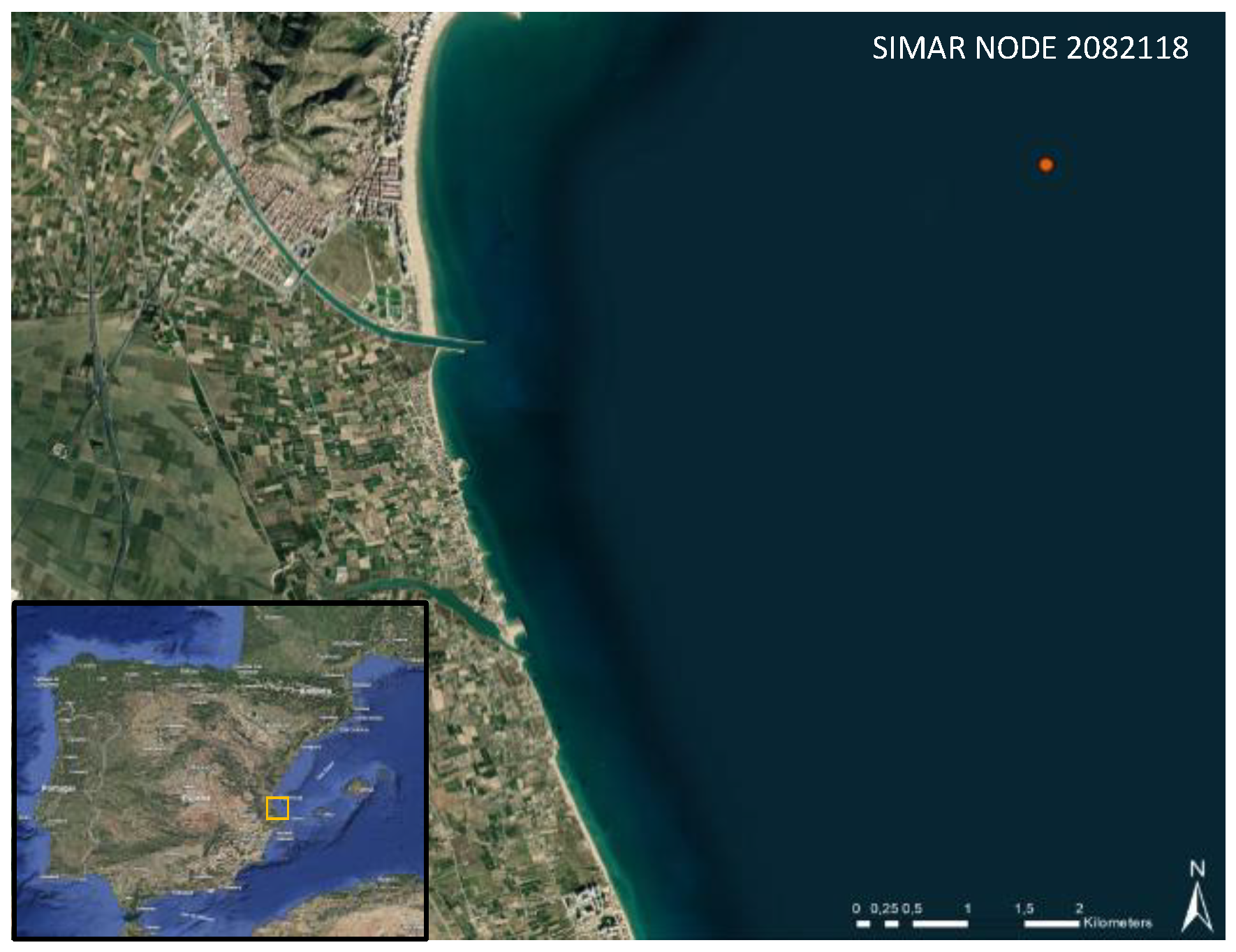

2. Materials and Methods

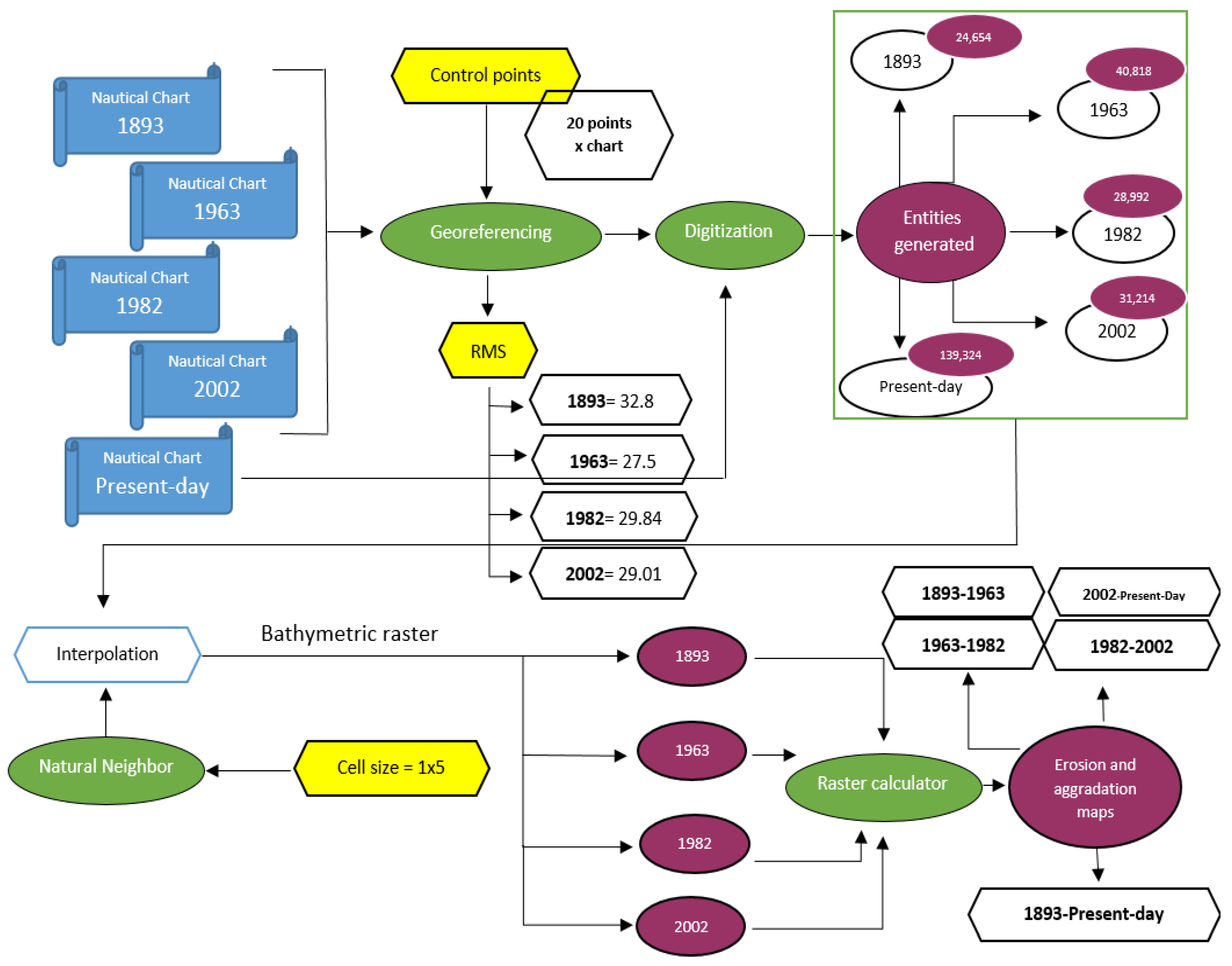

2.1. Georeferencing of Nautical Charts

2.2. Digitization of the Bathymetric Coordinates and Isobaths of the Nautical Charts

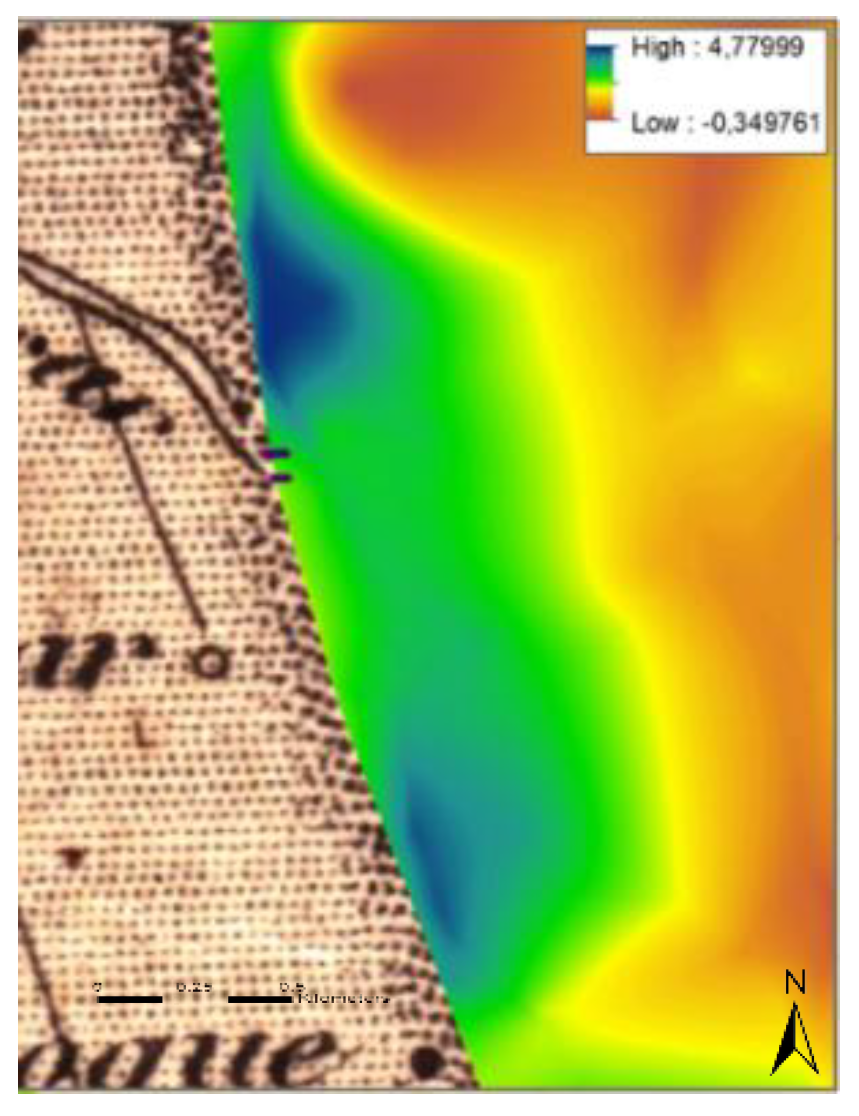

2.3. Rasterization and Interpolation

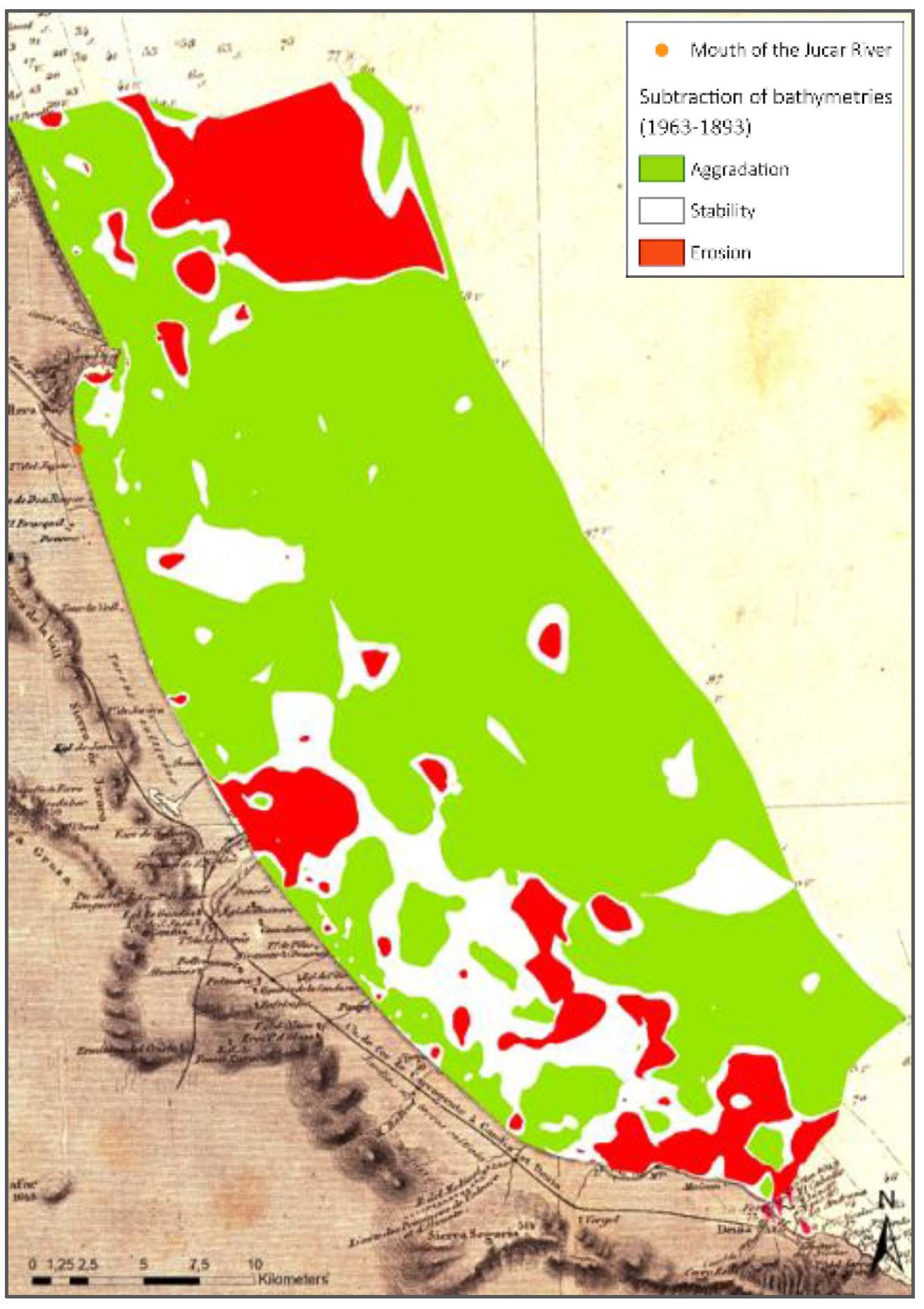

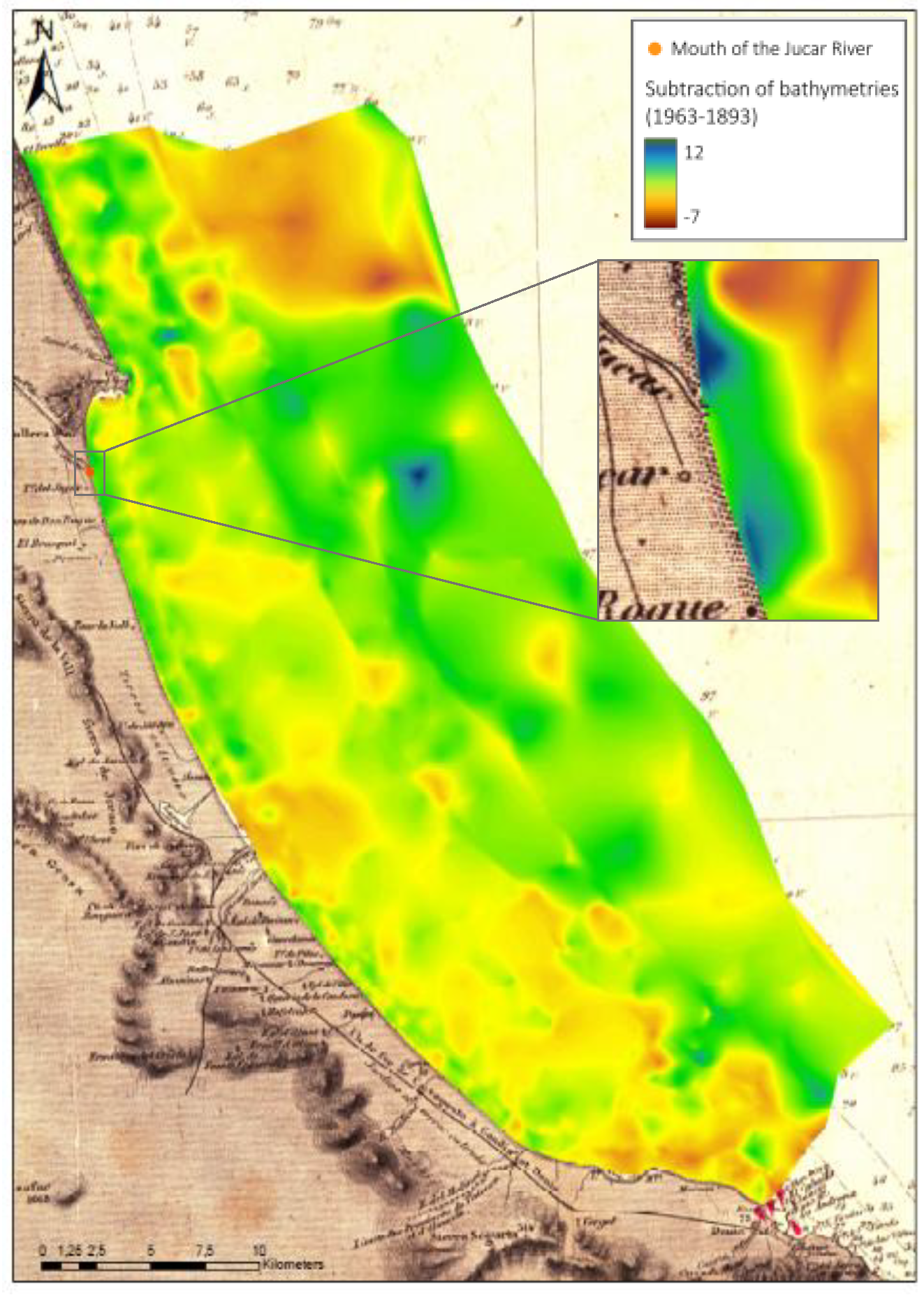

2.4. Raster Processing Analysisand

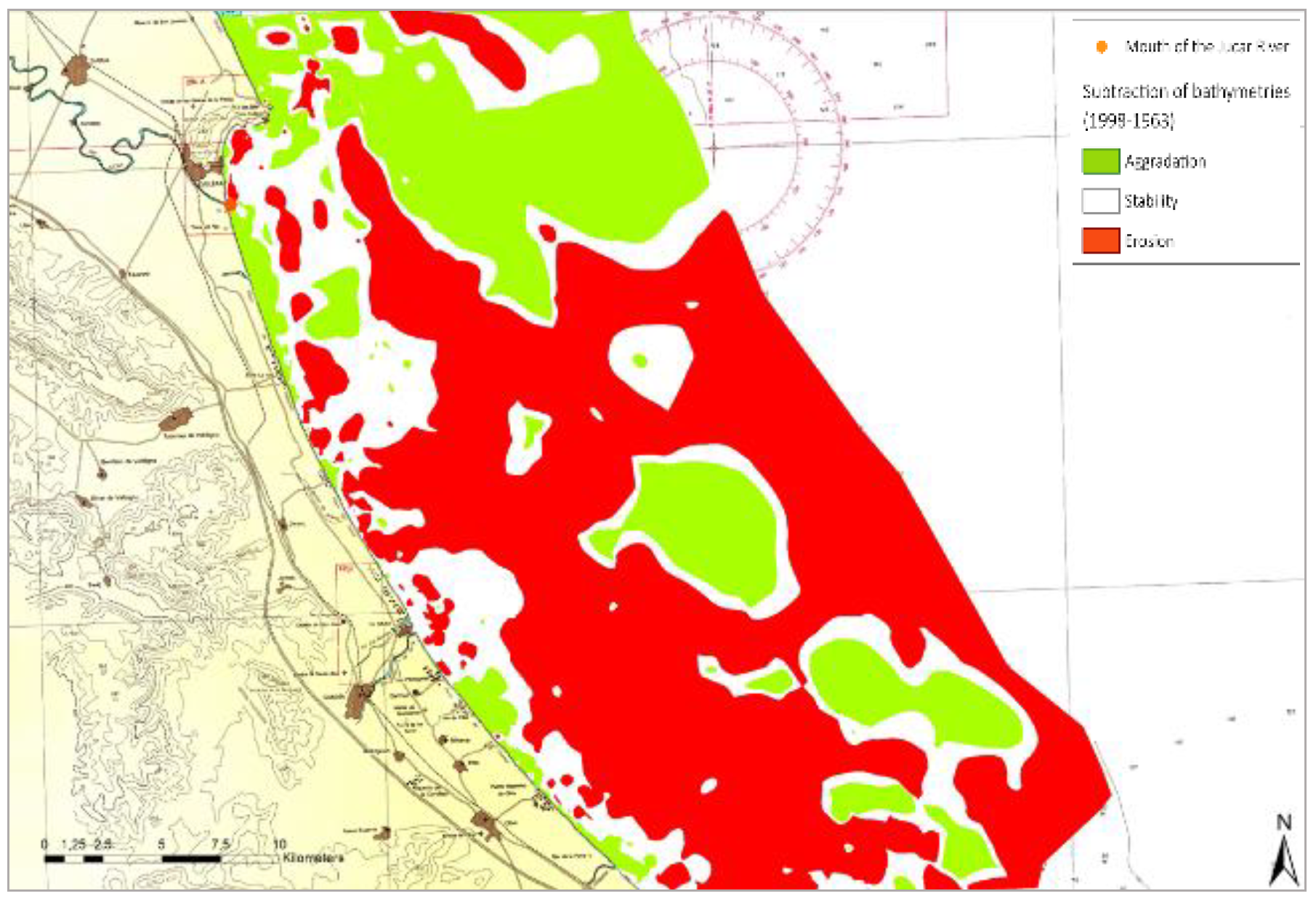

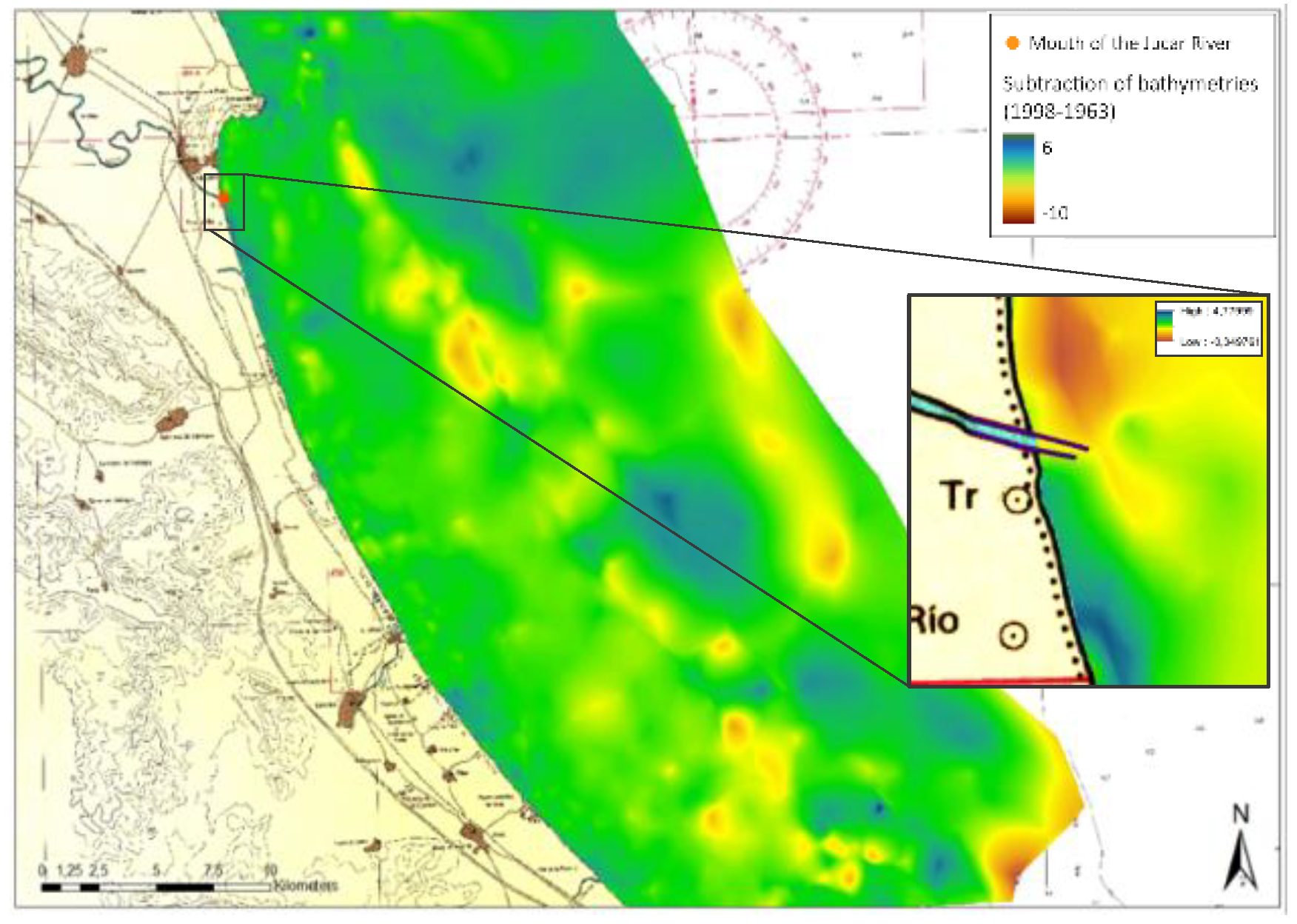

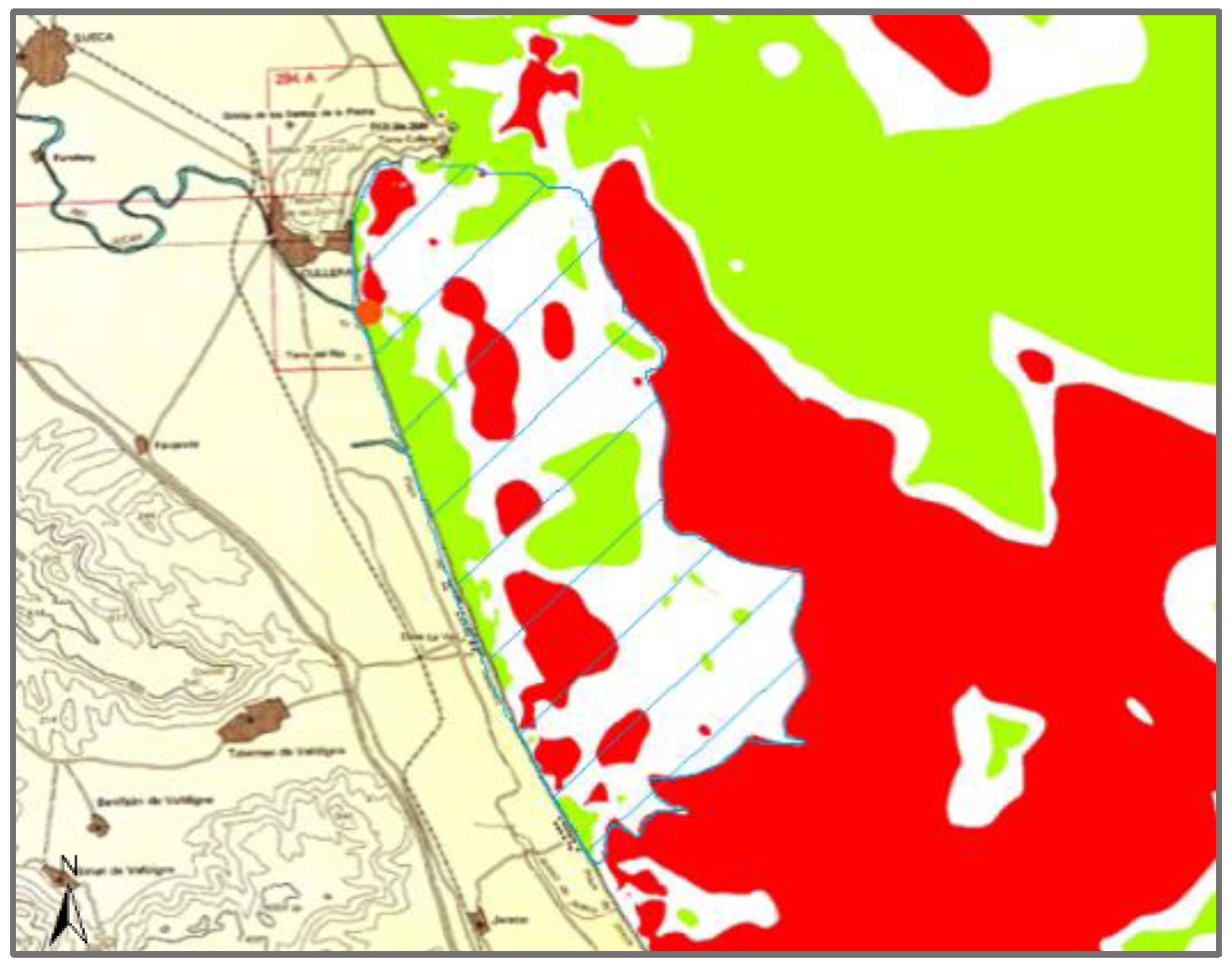

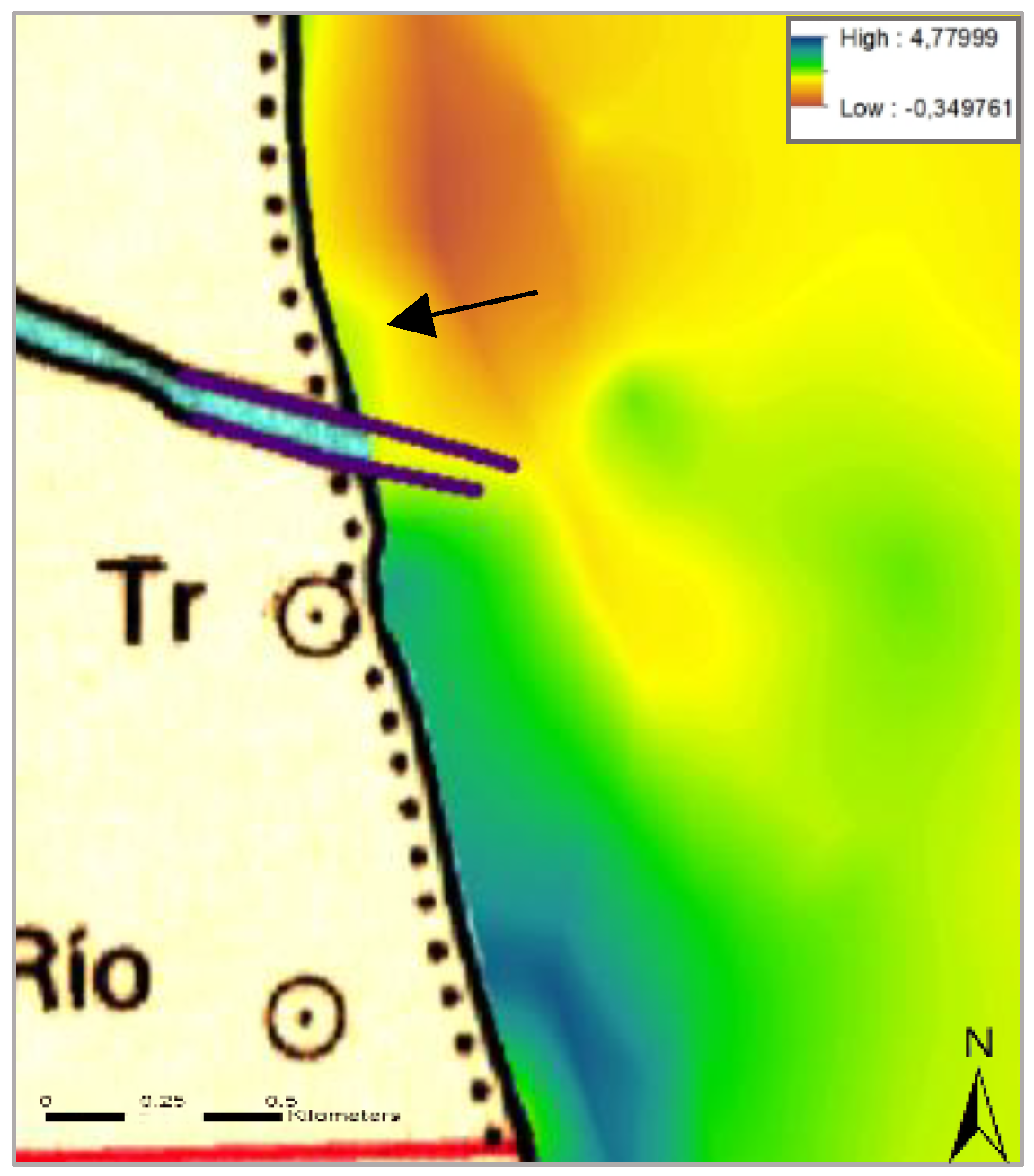

- 1893-1963

- 1963-1992

- 1992-2002

- 2002-Present-day

3. Results and Discussion

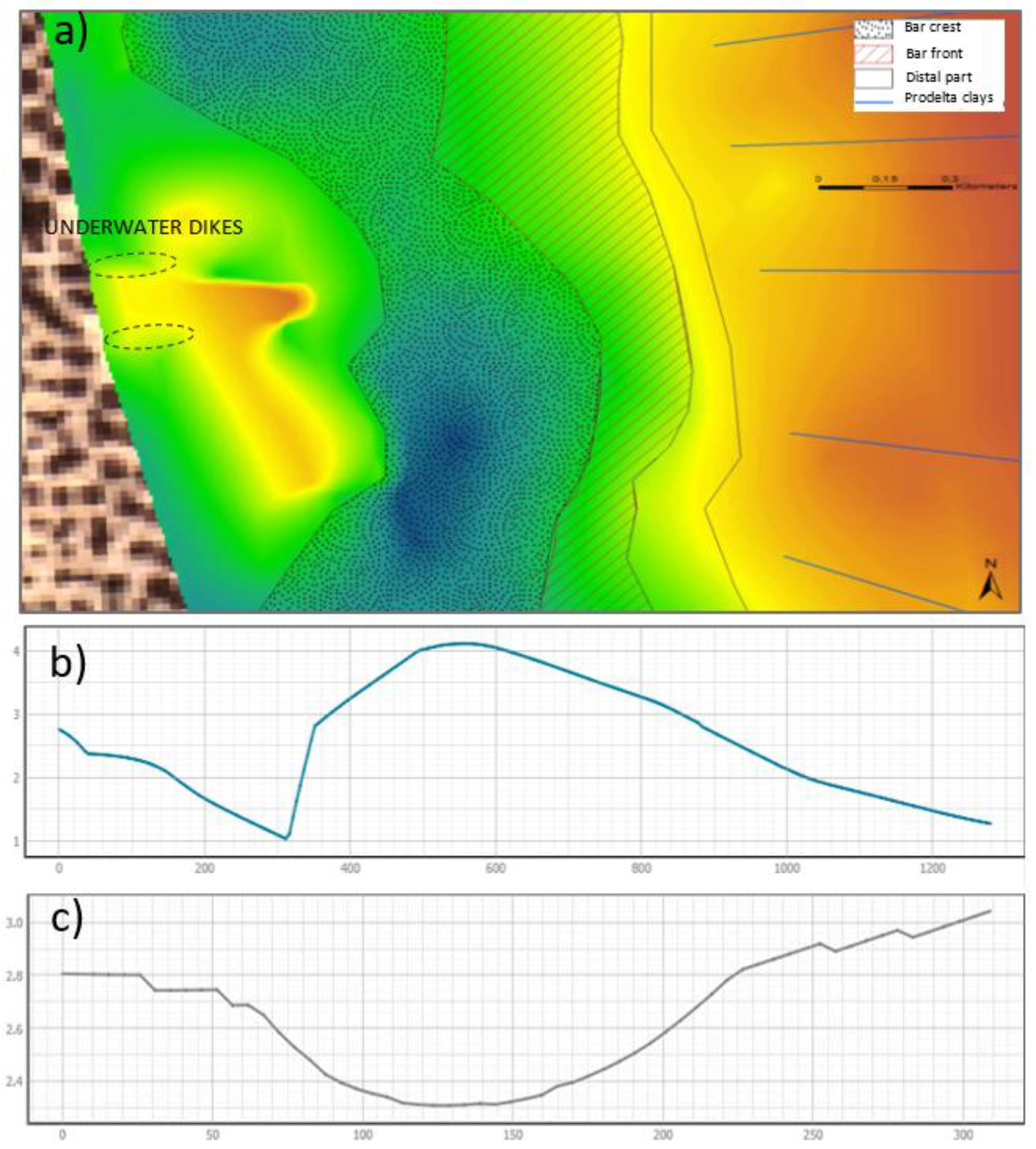

3.1. Bathymetric Analysis of the Delta from the 19th Century to the Present

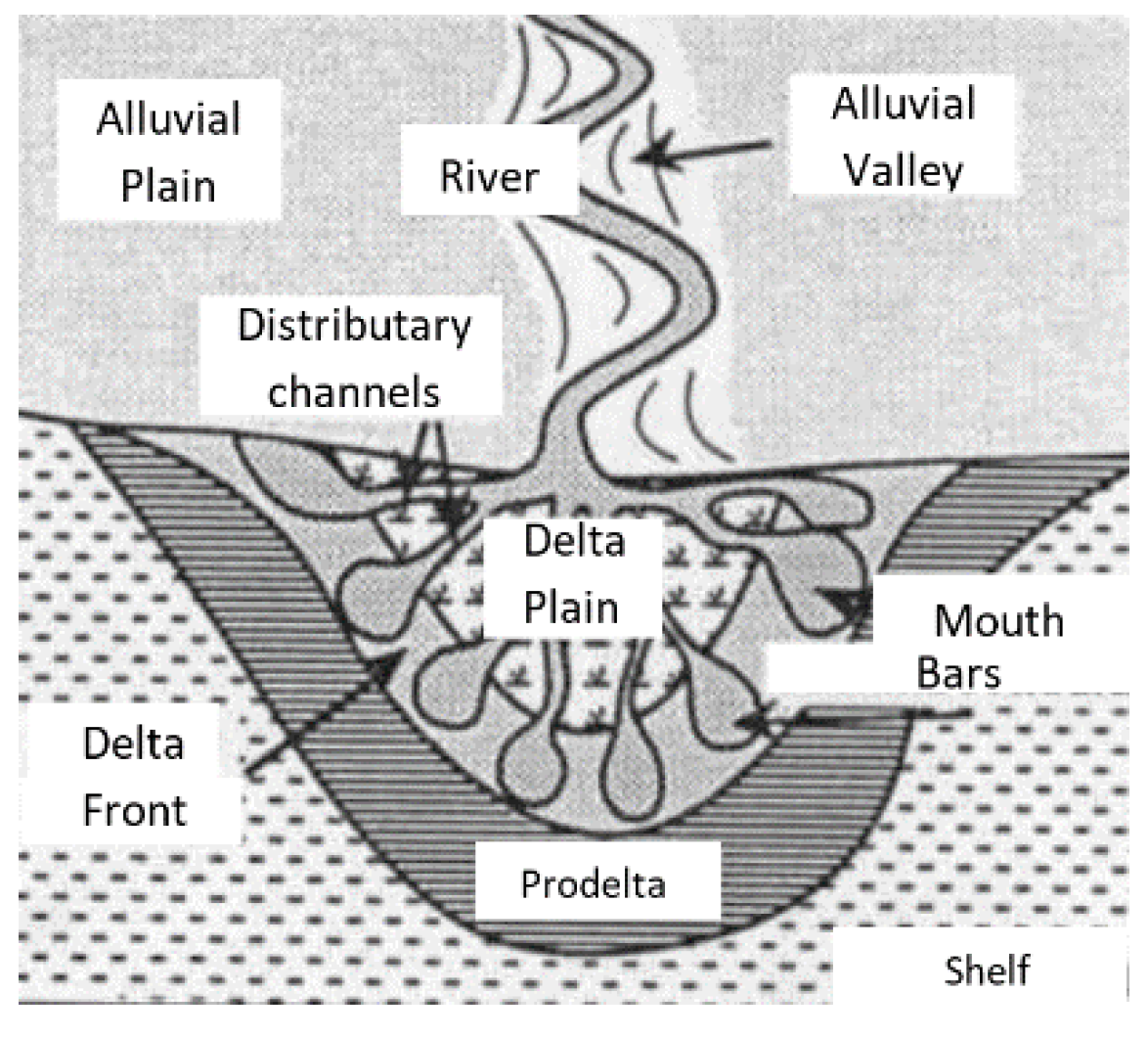

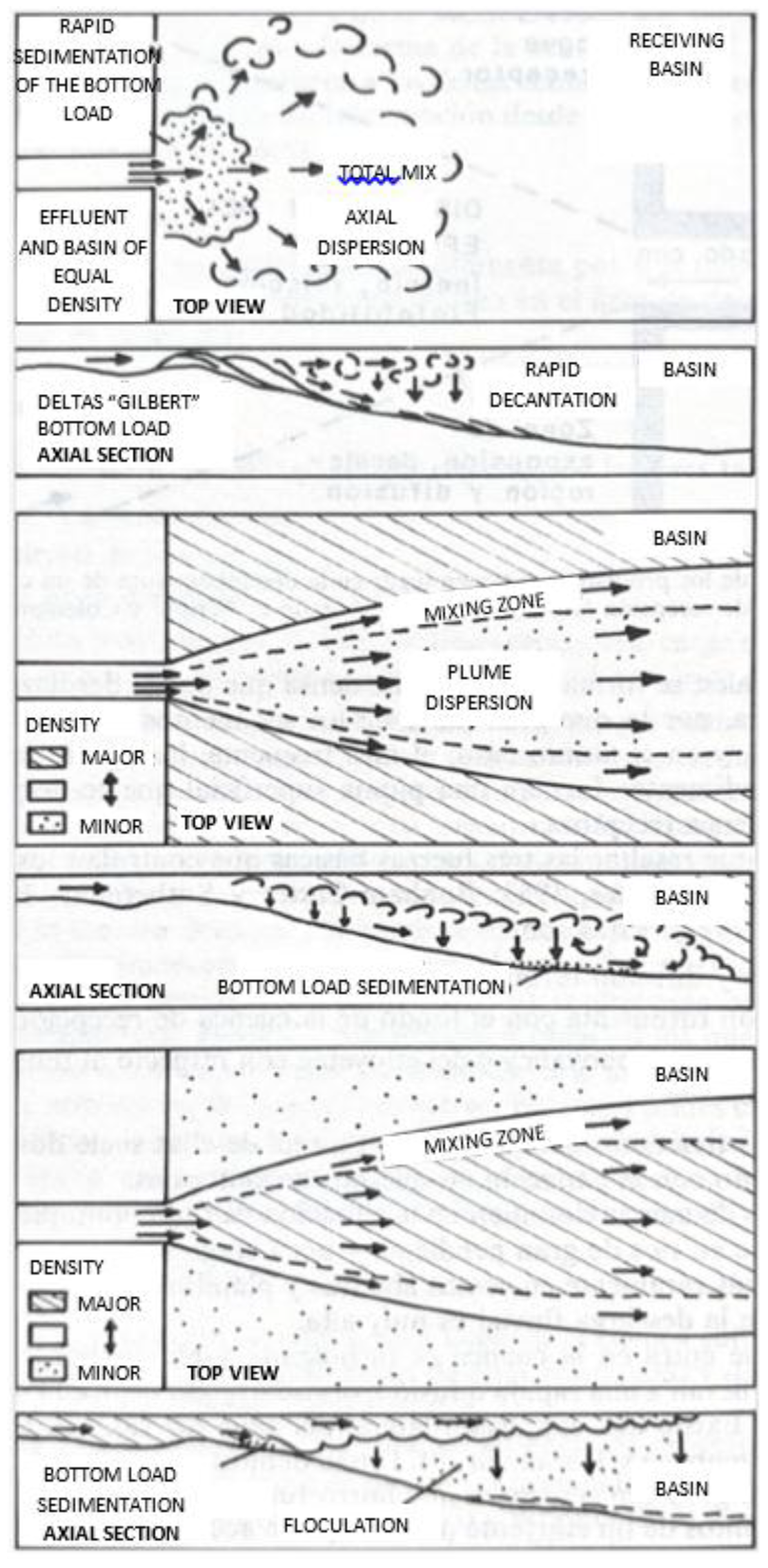

3.2. Determination of Delta Type

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| MIS 1 | Marine Isotopic Stage 1 |

| CHJ | Jucar Hydrographic Confederation |

| “DANA” | Isolated High Level Depression |

| IPCC | Intergubernamental Panel on Climate Change |

| RMS | Root Mean Square error |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| TIN | Triangulated Irregular Network |

| ESRI | Environmental Systems Research Institute |

| ICV | Valencian Cartographic Institute |

References

- Arche, A. Deltas. In Sedimentología; Arche, A., Ed.; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: Madrid, Spain, 1992; Volume 1, pp. 397–454. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, G.K. The topographic features of lake shores. U.S. Geol. Surv. 1885, 5, 75–123. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, G.K. Lake Bonneville. U.S. Geol. Surv. 1890, Monography 1, 1–148. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.M.; Gagliano, S.M. Sedimentary Structures: Mississippi River Deltaic Plain. In Primary Sedimentary Structures and Their Hydrodynamic Interpretation; Middleton, G.V., Ed.; Society for Sedimentary Geology: Oklahoma, OK, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, C. Rational theory of delta formation. AAPG Bull. 1953, 37, 2119–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.D. Sediment transport and deposition at river mouths: A synthesis. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1977, 88, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, J.; Duvail, C.; Le Strat, P.; Gensous, B. High resolution stratigraphy and evolution of the Rhône delta plain during Postglacial time, from subsurface drilling data bank. Mar. Geol. 2005, 222–223, 267–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneton, H.; Arnaud-Fassetta, G.; Provansal, M.; Sistach, D. Geomorphological evidence for fluvial change during the Roman period in the lower Rhone valley (southern France). Catena 2001, 45, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, P.; Caputo, C.; Davoli, L.; Evangelista, S.; Garzanti, E.; Pugliese, F.; Valeria, P. Morpho-sedimentary characteristics and Holocene evolution of the emergent part of the Ombrone River delta (southern Tuscany). Geomorphology 2004, 61, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorosi, A.; Milli, S. Late Quaternary depositional architecture of Po and Tevere river deltas (Italy) and worldwide comparison with coeval deltaic successions. Sediment. Geol. 2001, 144, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, P.; Caputo, C.; Davoli, L.; Evangelista, S.; Garzanti, E.; Pugliese, F.; Valeria, P. Morpho-sedimentary characteristics and Holocene evolution of the emergent part of the Ombrone River delta (southern Tuscany). Geomorphology 2004, 61, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorosi, A.; Giovanni, S.; Rossi, V.; Fontana, V. Anatomy and sequence stratigraphy of the late Quaternary Arno valley fill (Tuscany, Italy). In Advances in Application of Sequence Stratigraphy in Italy; Amorosi, A., Haq, B.U., Sabato, L., Eds.; University of Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2008; pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, V.; Amorosi, A.; Sarti, G.; Romagnoli, R. New stratigraphic evidence for the mid-late Holocene fluvial evolution of the Arno coastal plain (Tuscany, Italy). Géomorphol. Relief Processus Environ. 2012, 2, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cearreta, A.; Benito, X.; Ibáñez, C.; Trobajo, R.; Giosan, L. Holocene palaeoenvironmental evolution of the Ebro Delta (Western Mediterranean Sea): Evidence for an early construction based on the benthic foraminiferal record. Holocene 2016, 26, 1438–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, P.; Ruiz, J.M. Las inundaciones de los ríos Júcar y Turia. Ser. Geogr. 2000, 9, 49–69. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10017/1093 (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Carmona, P.; Ruiz, J.M. Historical morphogenesis of the Turia River coastal flood plain in the Mediterranean litoral of Spain. Catena 2011, 86, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Clavel, B.; Segura, F.; Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Guillén, J. Análisis de los cambios morfológicos en el delta sumergido del Ebro (1880–1992). In Comprendiendo el relieve: del pasado al futuro. Actas de la XIV Reunión Nacional de Geomorfología; Durán Valsero, J.J., Montes Santiago, M., Robador Moreno, A., Salazar Rincón, Á., Eds.; Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Málaga, Spain, 2016; pp. 531–537. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, R.; Roca, M.; Martínez-Clavel, B.; Blázquez, A.M. Long-term bathymetric changes in the submerged delta of the Turia river since the nineteenth century (Western Mediterranean) and their drivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete, E. Apuntes de geología histórica, 1st ed.; Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL): Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alzaga, D.; Solórzano, D. Deltas. Available online: https://usuarios.geofisica.unam.mx/cecilia/CT-SeEs/Deltas_13-2.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Canale, N.; Ponce, J.J.; Carmona, N.B.; Parada, M.N.; Drittani, D.I. Sedimentología de un delta fluvio-dominado, Formación Lajas (Jurásico Medio), cuenca Neuquina, Argentina. Andes. Geol. 2020, 47, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala, C. Los deltas litorales hiperpícnicos de la formación Mulichinco (Valanginiano), Cuenca Neuquina. In Actas del XXI Congreso Geológico Argentino, Puerto Madryn, Argentina, 2022.

- Buatois, L.A.; Saccavino, L.L.; Zavala, C. Ichnologic signatures of hyperpycnal flow deposits in Cretaceous river-dominated deltas, Austral Basin, southern Argentina. In Sediment Transfer from Shelf to Deep Water—Revisiting the Delivery System; Slatt, R.M., Zavala, C., Eds.; AAPG Studies in Geology; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2011; Volume 61, pp. 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.M.; Gagliano, S.M. Cyclic Sedimentation in the Mississippi River Deltaic Plain. Gulf Coast Assoc. Geol. Soc. Trans. 1964, 14, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Arndorfer, D.J. Discharge patterns in two crevasses of the Mississippi River Delta. Mar. Geol. 1973, 15, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.D.; Coleman, J.M. Mississippi River Mouth Processes: Effluent Dynamics and Morphologic Development. J. Geol. 1974, 82, 751–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.H.; Adams, R.D.; Cunningham, H.W. Evolution of sand-dominant subaerial phase, Atchafalaya Delta, Louisiana. AAPG Bull. 1980, 64, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Heerden, I.L. Deltaic sedimentation in eastern Atchafalaya Bay, Louisiana. Ph.D. Thesis, Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Confederación Hidrográfica del Júcar. Memoria 2023. Available online: https://www.chj.es/es-es/Organismo/Memoriasdeactuaciones/Paginas/Memoria2023.aspx (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Meteorological Organization. State of the Global Climate 2023; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.M.; Carmona, P. Turia river delta and coastal barrier-lagoon of Valencia (Mediterranean coast of Spain): Geomorphological processes and global climate fluctuations since Iberian-Roman times. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019, 219, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, B. El Gran Calentamiento: Cómo Influyó el Cambio Climático en el Apogeo de las Civilizaciones; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, M.L. La Pequeña Edad de Hielo en el Golfo de València: procesos de deltas y sistemas de restinga-albufera. La desestabilización reciente. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, M.; Žebre, M.; Guglielmin, M.; Hughes, P.D.; Çiner, A.; Vieira, G.; Bodin, X.; Andrés, N.; Colucci, R.R.; García-Hernández, C.; et al. Permafrost conditions in the Mediterranean region since the Last Glaciation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 185, 397–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A. Regímenes natural y artificial del río Júcar. Investig. Geogr. 2006, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, J.B. Los proyectos de regulación de los ríos Júcar y Turia (1928–1964). Una nueva lectura. Cuad. Geogr. Univ. València 2012, 91–92, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.M.; Carmona, P. La llanura deltaica de los ríos Júcar y Turia la Albufera de Valencia. In Geomorfologia i Quaternari Litoral; Sanjaume, E., Mateu, J., Eds.; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2005; pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Fumanal, M.P.; Calvo, A. Repercusiones geomorfológicas de las lluvias torrenciales de octubre de 1982 en la cuenca media del río Júcar. Cuad. Geogr. Univ. València 1983, 32–33, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, P.; Fumanal, M.A. Estudio sedimentológico de los depósitos de inundación en la Ribera del Xúquer (Valencia), en octubre de 1982. Cuad. Investig. Geogr. 1985, 11, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, V. Dinámica litoral y sedimentación en las costas valencianas. In Geoarqueología Quaternari Litoral; Fumanal García, M.P., Ed.; Universitat de València, Departament de Geografía: Valencia, Spain, 1999; pp. 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjaume, E. Las costas valencianas. Sedimentología y morfología. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Roig Echegaray, V.; Gracia García, V.; Sánchez-Arcilla Conejo, A. Dinámica de desembocaduras en ambientes micromareales. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Linares, J. Los Principios Básicos de la Ecosonda; Ministerio de Pesquerías: Lima, Peru, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Pilesjö, P. Triangulated Irregular Network (TIN) Models. In The Geographic Information Science & Technology Body of Knowledge; Wilson, J.P., Ed.; Association of American Geographers: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Systems Research Institute. ArcGIS Desktop. Available online: https://desktop.arcgis.com/es/arcmap/latest/tools/spatial-analyst-toolbox/extract-by-mask.htm (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Pérez-Guerra, G.A.; Sosa-Franco, I.; Machado-García, N.; Ruiz-Pérez, M.E. Herramientas SIG, revisión de sus fundamentos, tipos y relación con las bases de datos espaciales. Rev. Cienc. Téc. Agropecu. 2023, 32, 3, Available online: https://repositorio.ucm.edu.co/handle/10839/3288. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Atehortúa, D.A.; Alzate Álvarez, Á.M.; López Naranjo, Ó. Diseño de mapas de información de radiación solar en el departamento de Caldas a través de métodos de interpolación y herramientas de SIG. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Católica de Manizales, Manizales, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, I.; Martínez-Clavel, B.; Rodríguez-Pérez, A.; Blázquez, A.M. Cambios batimétricos en el delta sumergido del río Júcar desde el siglo XIX hasta la actualidad. In Coast2Coast’2025: II Jornada de Jóvenes Investigador@s en Morfodinámica de Costas—Book of Abstracts; Calvete, D., Cáceres, I., Mösso, C., Fernández-Mora, À., Eds.; SOCIB: Barcelona, Spain, 2025; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- De Antonio, R.; Almorox, J.; Saa, A.; Rueda, J.P. Erosión y aterramiento de embalses. Agric. Rev. Agropecu. 1995, 64, 151–154. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/28272869_Erosion_y_aterramiento_de_embalses (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- National Geographic. La catástrofe de la DANA en Valencia vista desde el espacio. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com.es/medio-ambiente/asi-se-ve-catastrofe-dana-valencia-espacio_23574 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Guillén, J. Impacto sobre la franja litoral. In Resumen sobre la Formación y Consecuencias de la Borrasca Gloria; Berdalet, E., Marrasé, C., Pelegrí, J.L., Eds.; Institut de Ciències del Mar, CSIC: Barcelona, Spain, 2020; pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Buitrago, N. Efectos de temporales marítimos en sistemas litorales de la provincia de Cádiz. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, P.; Ruiz, J.M.; Ibáñez, M. Erosión costera y cambio ambiental en el humedal de Cabanes-Torreblanca (Castelló). Datos para una gestión sostenible. Bol. Asoc. Geóg. Esp. 2014, 66, 161–180.

- Toledo, I. Estudio de los factores causantes de la erosión costera en las playas de Benidorm y Guardamar del Segura. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Institut Cartogràfic Valencià. Visor de Cartografia. Available online: https://visor.gva.es/visor/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

| Date | Zone | Scale | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1893 | From Cartagena to Valencia. | 1:242,320 | Newspaper archive of Valencia |

| 1963 | From Cabo de San Antonio to Albufera de Valencia. | 1:97,800 | Newspaper archive of Valencia |

| 1998 | From Rio Bullent to Cabo Cullera. | 1:50,000 | Newspaper archive of Valencia |

| 2002 | From Puerto de Calpe to Puerto de Sagunto. | 1:175,000 | Newspaper archive of Valencia |

| Present-day | From Albufera of Valencia to Gandia. | 1:120,605 | Navionics |

| Nautical Chart | Number of geo-referencing point | RMS |

|---|---|---|

| 1893 | 20 | 32.9799 m |

| 1963 | 20 | 27.5031 m |

| 1998 | 20 | 29.8384 m |

| 2002 | 20 | 29.0119 m |

| Nautical Chart | Number of digitized items |

|---|---|

| 1893 | 24,654 |

| 1963 | 40,818 |

| 1998 | 28,992 |

| 2002 | 31,214 |

| Present-day | 139,324 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).