1. Introduction

Since the “year of MOOC” (Pappano, 2012), Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have undergone dramatic development over the past decades (Peng & Jiang, 2022), and emerged as an innovative online education which facilitates broader access to diverse disciplinary content for the general public with common interest (Bárcena et al., 2014; Terras & Ramsay, 2015). Accordingly, MOOCs have been engaging millions of learners at various levels worldwide (Gupta & Sabitha, 2019), especially in dealing with the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic. To date, MOOCs have been significant pedagogical resources and novel curriculum type for instruction and have gained widespread adoption in higher education.

However, extant studies manifest that despite MOOCs’ salient advantages in free access and spatiotemporal flexibility, MOOC learners encounter several challenges (Hew & Cheung, 2014), such as deficient face-to-face interaction (Cho & Byun, 2017), high dropout rate (Bárcena et al., 2014; Chen, 2014; Gupta & Sabitha, 2019; Lee, Watson & Watson, 2020; Chen et al., 2024), low pass rates (Kuo, Tsai & Wang, 2021; Qian et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2024), academic integrity and ethics(Marshall,2014; Peng & Jiang, 2022). These issues would be particularly relevant to language MOOCs, of course including English writing MOOCs, where language is both the medium of instruction (Peng & Jiang, 2022) and the tool of writing.

To explore reasons resulting in the challenges, LPA (latent profile analysis), which is a person-centered approach assuming that the MOOC learners are not homogeneous, can provide deeper insights by identifying latent subgroups of learners based on their self-efficacy levels and associated learning characteristics, and highlight the value of classifying individual learner according to different clusters of variables (Masyn, 2013), is employed. However, while self-efficacy has been extensively studied in traditional classroom settings, scarce research has explored its role in MOOC-based English writing instruction, particularly in the Chinese context.

Besides, in response to the aforementioned challenges, there is a rising body of literature which recognize the positive effect of learner self-efficacy in MOOCs (Kormos & Nijkowska, 2017; Zhang, Yin, Luo & Yan, 2017; Hsu, Chen & Ting, 2018;Gameel & Wilkins, 2019; Kuo, Tsai, & Wang, 2021; Rekha, Shetty & Basri, 2023; Wei, Saab & Admiraal, 2024). However, how learners with varying levels of self-efficacy engage in MOOC learning remains unclear. As for research on MOOCs learners, most has largely used variable-centered approach neglecting that they are heterogeneous (Lee et al., 2020; Kuo et al., 2021).

To bridge these gaps, this study employs LPA to (1) identify latent profiles of Chinese college students in terms of their self-efficacy levels in an English writing MOOC, and (2) examine how these profiles differ in terms of interaction and discussion, perseverance in online learning, attitude, preference, flexibility in online learning. By employing the person-centered approach, this study intends to offer a more nuanced understanding of learner diversity in online writing instruction, providing practical insights for writing MOOC designers and instructors to better facilitate learners with varying self-efficacy levels.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy in foreign language learning typically refers to learners’ confidence in their foreign language abilities and their capacity to cope with the challenges of language acquisition, exhibiting a certain degree of dynamism and context-dependency. When it comes to English writing, self-efficacy plays a pivotal role in the composition process, for it necessitates not only students’ mastery of writing and linguistic skills but also their confidence in efficiently regulating the anxieties and affective challenges inherent to writing tasks (Pajares &Valiante, 2006). Therefore, online Learners with high self-efficacy are generally more inclined to adopt proactive learning strategies and demonstrate greater persistence when encountering difficulties. Research on online learning indicates that self-efficacy and extrinsic motivation have a significant positive predictive effect on English learning (An et al., 2024). In addition, Agonacs et al. (2020) emphasized MOOC learners are extremely diverse in terms of their age, qualifications, background and so on. Therefore, the impact of self-efficacy may vary depending on individual backgrounds and learning contexts, its specific mechanisms in online language learning require further empirical validation.

The academic community remains divided regarding the influence of self-efficacy on technology acceptance. Lai & Huang (2018) emphasized that self-efficacy can directly and indirectly affect perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, while self-efficacy also influences attitudes of usage (Bulut & Delialioğlu, 2022) and behavioral intentions (Gan & Balakrishnan, 2016). Against the backdrop of digital transformation in education, studies on the impact of self-efficacy on MOOC learning suggest a generally positive influence, yet such precise mechanisms remain unclear. Thus, there is an urgent need to investigate the demonstration of self-efficacy across different learning platforms and elucidate its functional mechanisms in digital language learning, thereby providing stronger theoretical support for enhancing learners’ online learning experiences and outcomes.

2.2. Self-Efficacy and English Writing MOOC Learning

The current literature on the relationship between self-efficacy and MOOC learning generally falls into four classifications, presenting different or even conflicting views. First, self-efficacy affects in-service teachers’ completion of professional development MOOCs (Ma et al., 2023). Additionally, self-efficacy shows significantly influence on learners’ persistence and readiness in MOOC participation (Shao, 2018; Subramaniam et al., 2019). However, research also verified that direct predictive effect of self-efficacy on perceived course effectiveness was not statistically significant (Lee et al., 2020). There is still literature with divergent perspectives, indicting self-efficacy was found to be unrelated to MOOC learning (Wang & Zhu, 2019). Synthesizing the above, the consensus is that self-efficacy has a positive impact on MOOC learning.

Additionally, learners’ belief in their ability to use technology on MOOC platforms (i.e., computer self-efficacy) has a direct impact on their learning outcomes (Bandura, 1997; Liaw & Huang, 2013). When learners believe that they can effectively utilize computers and related technologies (such as large language models), their motivation to learn and their intention to continue learning are significantly enhanced (Zhang et al., 2020). This sense of self-efficacy affects their perception of using the course, thereby influencing their satisfaction with the course and their ultimate intention to persist in MOOC learning (Joo, Joung, & Kim, 2014).

Studies also have shown that higher levels of computer self-efficacy can increase learners’ perceived usefulness of MOOCs, which in turn improves their satisfaction with the learning experience and their intention to continue using the platform (Alraimi et al., 2015). The enhancement of self-efficacy allows students to better cope with the technical challenges they might encounter during online learning, thus improving their learning efficiency and outcomes (Compeau & Higgins, 1995). Moreover, the research also indicates that confirming learners’ expectations (i.e., the platform delivering on learners’ initial expectations) plays a significant role in enhancing self-efficacy. Nevertheless, how learners with varying degrees of self-efficacy participate in English writing MOOC-based learning remains insufficiently understood.

2.3. Latent Classes of Self-Efficacy and Their Characteristics

The existing studies have demonstrated that language learners cannot be simply categorized into groups of high or low self-efficacy, as evidenced by the Internet-based learning self-efficacy like Kuo et al., (2021). However, empirical research remains limited in examining the potential latent classes of MOOC learning self-efficacy among Chinese university students and how self-efficacy profiles relate to their MOOC learning performance.

To date, only a limited number of studies in the field of second language writing acquisition have adopted an individual-centered approach to analyze the latent categories of self-efficacy (DeBusk-Lane et al., 2023; Zhang & Zhang, 2024). Specifically, Zhang and Zhang (2024) used a sample of 391 EFL students from two Chinese universities to profile their writing self-efficacy and its relationship with their writing strategies under self-regulated learning environment. Latent profile analysis identified three distinct profiles of writing self-efficacy: “Low on All Self-efficacy”, “Average on All Self-efficacy”, and “High on All Self-efficacy” (Zhang & Zhang, 2024). Moreover, Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Welch’s tests further indicated that these profiles exhibited statistically significant differences in writing self-efficacy, self-regulated learning (SRL) writing strategies, and writing achievement. Subsequent path analyses revealed profile-based variations in (a) the predictive relationships between writing self-efficacy and SRL writing strategies, and (b) the predictive effects of both writing self-efficacy and SRL strategies on writing achievement outcomes. DeBusk-Lane et al. (2023) adopted a bifactor ESEM, three latent profiles were attracted from a sample of 1466 8th–10th graders, characterized by a common indicator across Strongly Inefficacious (Conventions), Moderately Inefficacious (Ideation), and Efficacious (Self-Regulation). And evidence for concurrent, divergent, and discriminant validity was substantiated through a comprehensive set of analyses examining both antecedents and consequences of the identified profiles, including demographic characteristics, standardized writing assessment scores, and academic grades (DeBusk-Lane et al., 2023). Overall, existing research on MOOC learners has predominantly employed variable-centered methodologies, often overlooking the inherent heterogeneity within this population.

2.4. The Present Study

This study aimed to discern Chinese college students’ profiles of self-efficacy in college English writing MOOC through LPA and to identify the possible differences in their learning performance in terms of interaction and discussion, perseverance in online learning, attitude, preference, flexibility in online learning. The research questions were addressed as bellow.

- (1)

What are the latent profiles of self-efficacy in college English writing MOOC in China?

- (2)

Do the identified profiles differ significantly in their learning performance (i.e., interaction and discussion, perseverance in online learning, attitude, preference, flexibility)?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

586 first year students from a college in eastern China were recruited based on convenience sample method. Among these participants, 417 were male, and 169 were female. All the participants’ English learning followed the same curriculum set by the Chinese Ministry of Education which aims to assist learners for the College Entrance Examination at the end of the third year. In addition, all the participants were native Chinese students with no foreign learning experience. Questionnaires were distributed during the break by their English teachers respectively. All the participants were informed of the purposes of the study, and those who wanted to participate could finish the questionnaires onsite during the break. The total response rate was 99.5%.

3.2. Measurements

Composite questionnaires were used in the present study, and they consisted of demographic information and two well-established psychometric scales aimed to measure students’ self-efficacy, English writing MOOC learning performance. During the data collection, all participants were enrolled in the “College English Writing” MOOC. This course serves as an extended resource for the compulsory “College English” writing instruction, with a primary focus on assisting learners in enhancing their English writing skills.

3.2.1. Self-Efficacy Scale

The self-efficacy scale was developed by Teng et al. (2018) to investigate the self-efficacy status and level of learners engaged in online college English writing MOOCs. The scale includes three subscales: language self-efficacy, self-regulatory efficacy, and behavioral self-efficacy, with a total of 20 items. In this research, the overall reliability of the scale is excellent (Cronbach’s α = .937), and the structural validity is also good (χ2/df = 1.854 < 3; CFI = .954 > .90; TLI = .947 > .90; SRMR = .042 < .08; RMSEA = .064 < .08).

3.2.2. English Writing MOOC Learning Scale

The English writing MOOC learning scale was slightly adapted from the scale developed by Li et al. (2013) to assess the overall learning status of learners engaged in online college English writing MOOCs. The scale consists of five subscales: persistence, flexibility, interaction and communication, learning attitude, and online tendency, with a total of 22 items. In this research, the overall reliability of the scale is good (Cronbach’s α = .908), and the structural validity fits well (χ2/df = 1.585 < 3; CFI = .964 > .90; TLI = .958 > .90; SRMR = 0.043 < .08; RMSEA = .053 < .08).value (Cronbach’s α = 0.90). The construct validity was also found to be acceptable (χ2/df = 2.70, CFI = 0.992, TLI = 0.989, SRMR =0.017, RMSEA = 0.047).

3.3. Data Analysis

The reliability and structural validity of the measurement tools were examined using SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 26.0 respectively.

In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficients were also calculated to examine the reliability of these scales using SPSS 26.0. Referring to Zhang and Zhang’s (2024) article, Cronbach’s α above 0.70 indicates that the questionnaire has acceptable internal consistency. Besides, goodness-of-fit indices for construct validity included the Chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom (χ2/df), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The model fit is acceptable when χ2/df < 5 (Marsh & Hocevar, 1985), TLI and CFI >0.90 (Byrne, 2011), SRMR <0.05 (Diamantopoulos, Siguaw, & Siguaw, 2000), and RMSEA <0.08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1992) are reported. After checking reliability and validity, descriptive statistics (i.e., means and standard deviations) and correlation coefficients were also computed.

In order to answer the first research question, LPA as one of the most typical person-centered approaches that aim to identify externally heterogeneous but internally homogenous subgroups, was conducted using Mplus 8.3(Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Following the recommendations of DeBusk-Lane et al. (2023) and Zhang and Zhang (2024), model selection took the following criteria into consideration: self-efficacy theory, English writing MOOC learning practice in China, and model fit indices. The statistical indices used in this study included Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), sample size adjusted BIC (aBIC), the p-value of the Lo-Mendel-Rubin’s Likelihood ratio test (LMR), Bootstrap Likelihood ratio test (BLRT), and entropy (Li et al., 2022). The best model needed to show the following characteristics: AIC, BIC, and aBIC values should be lower than that of the other models; LMR and BLRT values should be significant at the p < 0.05 level; the value of entropy should be higher than 0.80 (as a higher level of entropy indicates a better model fit with value 1 indicating perfect classification) (Spurk et al., 2020). Model fit indices of two-profile to four-profile solutions were compared to identify the best model (Zhang & Zhang, 2024). Last, in order to answer the second research question, data generated from the LPA were imported into SPSS 26.0 for one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Detailed comparisons of the five variables between the three subgroups were conducted using Post hoc tests. Specifically, LSD tests were chosen when equal variances were reported, while Tamhane T2 tests were used when unequal variances were found.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Latent Profile Analysis

Based on a two-class model as the baseline, sequentially increased the number of latent classes, ultimately three distinct class models with varying numbers of categories were constructed.

Table 1 presents the goodness-of-fit indices for these three class models.

As is shown in

Table 1, the AIC, BIC, and aBIC values progressively decreased while the Entropy values first decreased and then increased with additional profiles, indicating superior model fit with more profiles. The BLRT

p-values for profile 2, 3 and 4models were all significant (

p < .001). LMR tests (

p < .001,

p = .046 < .05,

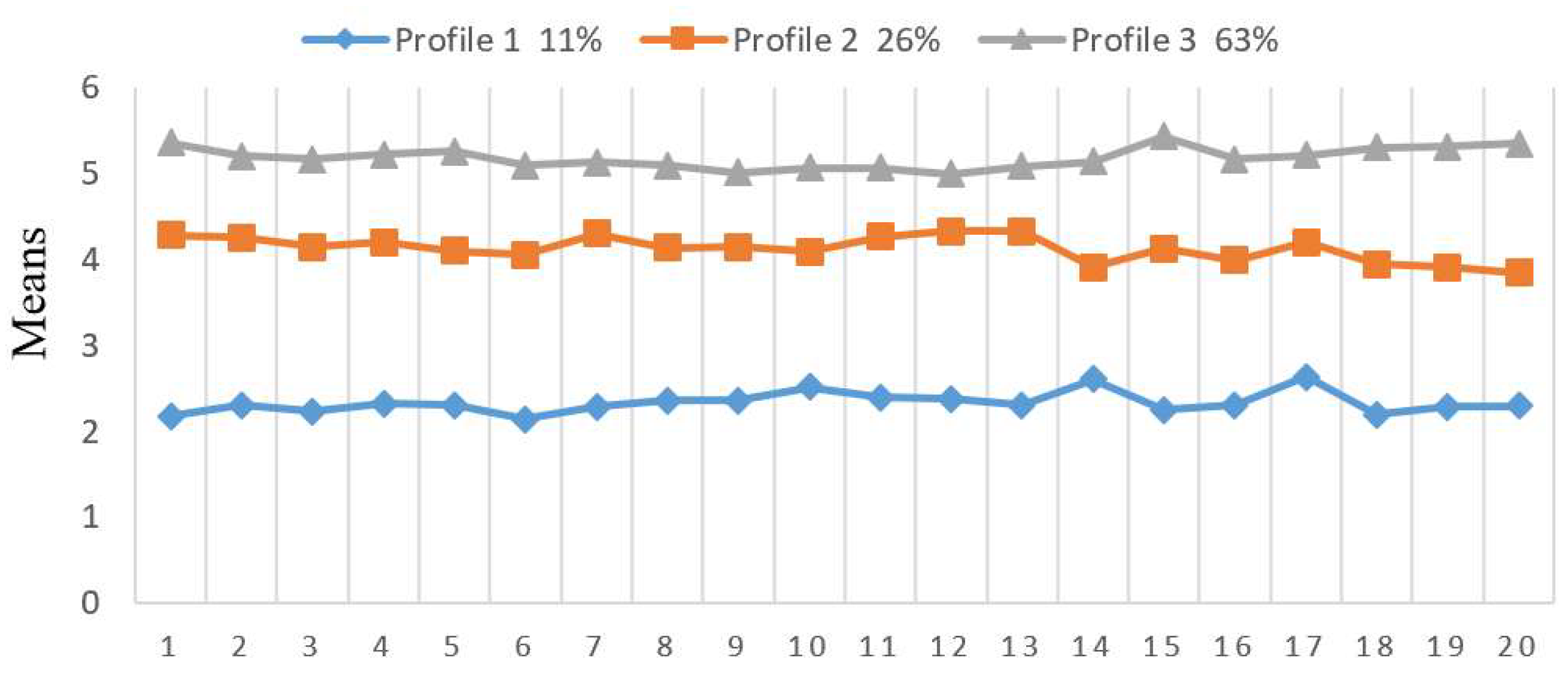

p =.665 > .05) demonstrated that the 3-class model showed improvement over their 2 and 4 class counterparts theory although the 2 and 4 class models achieved Entropy values exceeding .8, suggesting that the three-profile solution might be the best-fitted model for the profiles of students’ self-efficacy. The subtlety of the three profiles is displayed in

Figure 1.

Based on

Figure 1, the participants assigned to Profile 1 were identified by low scores on all the indicator items concerning linguistic self-efficacy, self-regulatory self-efficacy, and performance self-efficacy; and those classified to Profile 2 by average scores on nearly the total indicator items; while those classified to Profile 3 by moderately high scores on all the items. Overall, we labelled Profiles 1 to 3 as “Low on All Self-efficacy”, “Average Self-efficacy, “Moderately High Self-efficacy” respectively, which echoes Zhang & Zhang (2024). Significant differences among the three categories were observed at five aspects of English writing MOOC learning (F

Linguistic = 516.99,

P Linguistic < .001; F

Regulation = 280.08,

P Regulation < .001; F

Performance = 569.49,

P Performance < .001;) (see

Table 2).

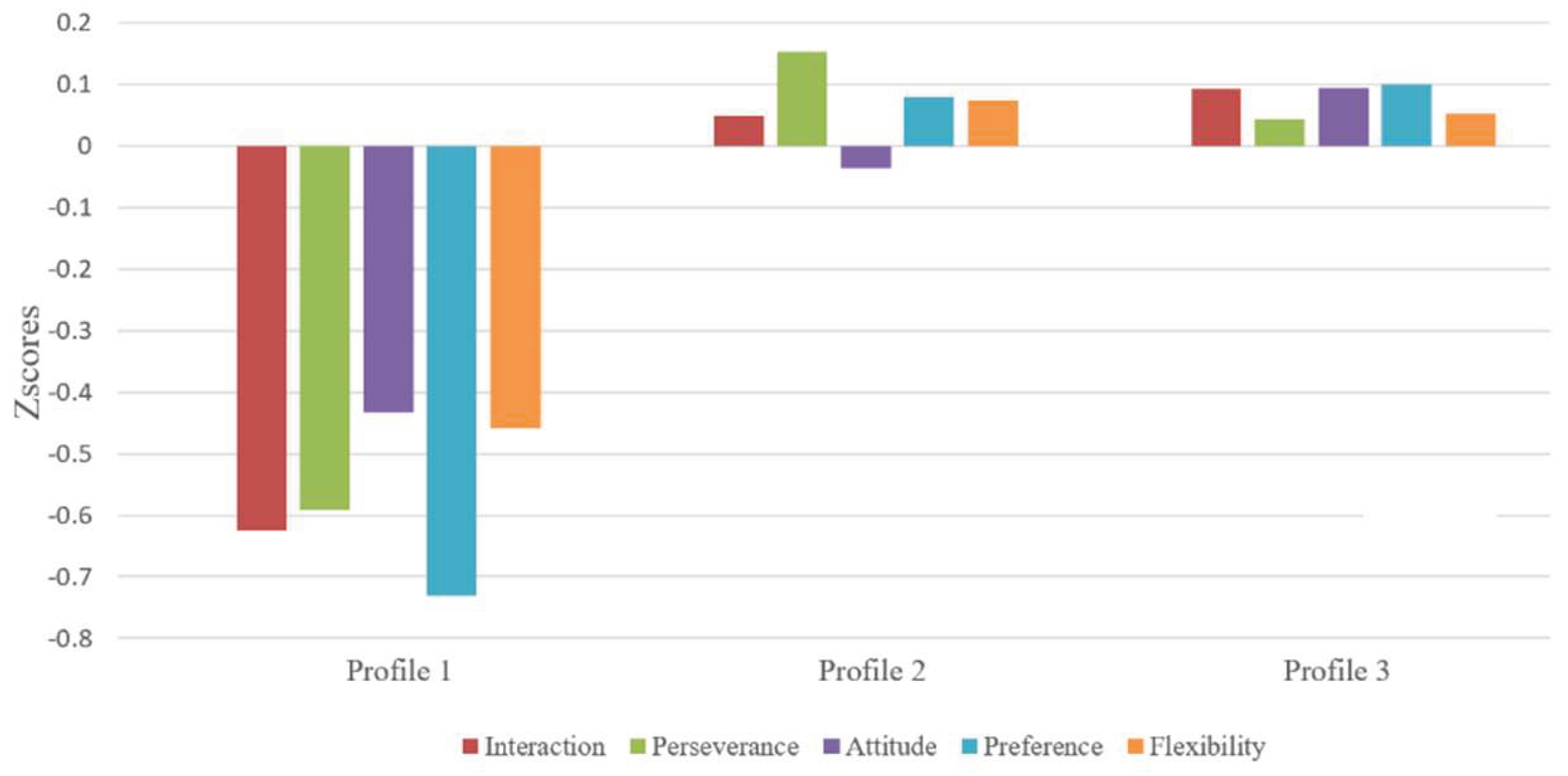

4.2. Comparison of Five Aspects of English Writing MOOC Learning Among the Profiles

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to examine the differences in the five aspects of Chinese college English writing MOOC learning among the three profiles. The results (see

Table 3) revealed significant differences in interaction (F(2, 580) = 15.33,

p < .001) , perseverance (F(2, 580) = 14.23,

p < .001), attitude (F(2, 580) = 8.03,

p < .001), preference (F(2, 580) = 21.29,

p < .001) and flexibility (F(2, 580) = 8.02,

p < .001) across different latent categories of self-efficacy. The levels of interaction, attitude and preference increased in the following order:

low on all self-efficacy, average on all self-efficacy, moderately high on all self-efficacy. While the levels of perseverance and flexibility increased in the following order: low on all self-efficacy, moderately high on all self-efficacy, average on all self-efficacy. Post hoc multiple comparisons indicated that the low on all self-efficacy category had significantly lower levels than average self-efficacy and moderately high self-efficacy category in terms of all the five aspects of English writing MOOC learning. The average self-efficacy category had significantly higher perseverance and preference than the other two categories. And the moderately high self-efficacy category showed significantly higher interaction, attitude and preference than the other two categories.

Figure 2 illustrates the between-group differences in standardized scores for interaction, perseverance, attitude, preference and flexibility across the three categories.

5. Discussion

5.1. Latent Profiles of College Students’ Self-Efficacy

Adopting a person-centered approach, this study employed Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) and identified a three-class model as the optimal solution for classifying self-efficacy patterns of Chinese university students in college English writing MOOC learning. The optimal model consisted of low on all self-efficacy(M Linguistic = 2.26, SD Linguistic = .57; M Regulation = 2.39, SD Regulation = .65; M Performance = 2.37, SD Performance = .70), average on self-efficacy(M Linguistic = 4.17, SD Linguistic = .98; M Regulation = 4.20, SD Regulation = 1.03; M Performance = 3.98, SD Performance = .92), moderately high self-efficacy profiles(M Linguistic = 5.19, SD Linguistic = .58; M Regulation = 5.05, SD Regulation =.82; M Performance = 5.26, SD Performance = .57), which echoes the prior research (Zhang & Zhang, 2024). The low on all self-efficacy in this study, consistent with Zhang and Zhang (2024), exhibited comparatively lower indicators in terms of interaction, perseverance, attitude, preference and flexibility of English writing MOOC learning, reflecting a small proportion of Chinese university students exhibit generally low self-efficacy in English MOOC learning. In contrast, the data of the three profiles suggest that as self-efficacy levels increase across the profiles, significant differences are observed in all three domains (Linguistic, Regulation, and Performance).

This highlights the significance of self-efficacy in predicting English writing MOOC learning outcomes. The statistical significance at the p < .001 level across all three dimensions indicates the robustness of the observed college students’ self-efficacy, which echoes Alshahrani(2025). The latent profiles of self-efficacy in this study contains moderately high self-efficacy profiles(M Linguistic = 5.19, SD Linguistic = .58; M Regulation = 5.05, SD Regulation =.82; M Performance = 5.26, SD Performance = .57), which differ from those in previous studies (DeBusk-Lane et al., 2023; Zhang & Zhang, 2024), likely due to the unique context of Chinese English writing MOOC and the characteristics of the participants’ academic backgrounds and their regional traits. In addition, the three-profile mode further confirms the complexity of self-efficacy, emphasizing the necessity and significance of self-efficacy research in language MOOC learning, thus making significant contribution to the theory and application of self-efficacy.

In terms of profile distribution, low on all self-efficacy profile constituted the smallest proportion (11%), followed by the average on self-efficacy profile (26%), while the moderately high self-efficacy profiles accounted for the highest proportion (63%). Dissimilar to the study by Zhang & Zhang (2024) on Chinese college students, the majority of university students in this study tended toward higher proportion of moderately high self-efficacy. This phenomenon may be partly attributed to the participants’ respective region distribution for the participants of this study are form a college in eastern China, as previous research has shown that a high on all self-efficacy taking up 25% (Zhang & Zhang, 2024). Besides, Alshahrani(2025) put forward that the three dimensions of self-efficacy all have predictive effects on the continued willingness to engage in English writing MOOC learning. Specifically, performance self-efficacy and self-regulation self-efficacy have a significant positive impact, while language self-efficacy has a significant negative impact, indicating that individuals with stronger language abilities tend to have lower willingness to continue learning (Alshahrani, 2025). These differences may reflect the influence of the advancement of digital transformation in foreign language education in China.

5.2. Differences in the Five Aspects of English Writing MOOC Learning Among the Profiles

The three latent profiles of college English writing MOOC learners’ self-efficacy are low on all self-efficacy, average on self-efficacy, moderately high self-efficacy profiles (taking up 63%). Regarding the differences observed across the three profiles, students exhibited significant variations in their interaction, perseverance, attitude, preference and flexibility, and actual English writing MOOC learning performance. The disparities in these five variables across the profiles provide empirical support for the theoretical proposition of the self-efficacy theory, which posits that varying levels of learners’ self-efficacy are closely associated with different levels of writing MOOC leaning willingness and performance (Alshahrani, 2025). The subclass of students characterized by moderately high self-efficacy profiles demonstrated the highest levels of interaction, attitude and preference, the lower levels of perseverance and flexibility. These findings are in line with those of Zhang and Zhang (2024), and in partial support and expand Alshahrani (2025) which has established that elevated levels of self-efficacy are strongly correlated with higher levels of actual English writing MOOC learning. In addition, the other two aspects, namely perseverance and flexibility, are highest in average on self-efficacy profile (constituting 26%) compared with the other two profiles (see

Table 3). And this profile has moderate interaction, attitude and preference while the rest one has the lowest on all the five aspects of English writing MOOC learning. This highlights the significance of enhancing students’ English writing self-efficacy in fostering their English writing MOOC learning success, which will eventually pave way to their language learning success. This study further supports the applicability of the self-efficacy theory in the field of English writing MOOC based second language acquisition from an individual perspective.

In this study, interestingly, the levels of the five aspects of English writing MOOC learning in low on all self-efficacy profile (taking up 11%) were significantly the lowest respectively. Although the moderately high self-efficacy category has the highest three aspects, the average category owns the highest other two aspects. This makes the phenomenon of college English writing MOOC learners’ self-efficacy more intriguing and intertwining. From this perspective, the findings of this research contradicting Zhang and Zhang’ 2024 study. There might be two possible reasons. On one hand, traditional Chinese classical culture goes the rise of one thing corresponds to the decline of another. This may affect students’ beliefs about sound self-efficacy development from enjoying the online English writing learning process and facing failure and mistakes as confidently and maturely as they should perform. On the other hand, online English writing MOOC learning poses more requests and challenges than that offline, and self-efficacy theory may not be sufficiently illustrated to the learners when facing online language learning. This underscores the urgent significance of conducting this study.

6. Conclusion and Future Directions

6.1. Conclusion

The present study confirms that an individual-centered approach is an effective way to study individual (and group) differences in self-efficacy profiles, promoting methodological innovation in the field of English writing MOOC based second language acquisition research. And through LPA analysis, this study identified the optimal latent profile model of self-efficacy classes of Chinese college English MOOC learners as a three-category model, namely low on all self-efficacy, average on self-efficacy, moderately high self-efficacy profiles. Each of these categories is characterized by distinct elements of self-efficacy features. The study uncovers two mixed self-efficacy patterns, revealing the heterogeneity and complexity of self-efficacy patterns among Chinese college English MOOC learners. This finding corresponds to the call of Teng et al., (2018), expanding the application of self-efficacy. Additionally, from an individual perspective, it presents new evidences in the field of English writing MOOC based second language acquisition for self-efficacy profile as a precursor to English writing MOOC learning (Alshahrani, 2025) and further validates the applicability of the self-efficacy theory (Zhang & Zhang, 2024) and the motivational beliefs (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020) in English writing MOOC based applied linguistics.

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

The study serves as one of the early empirical investigations into self-efficacy profiles among Chinese college English MOOC learners, offering significant insights for researchers and college English teachers. However, it still has several limitations, including a comparatively small sample size in typically covering various kinds Chinese English writing MOOC learners and a comparatively narrow scope of self-efficacy factors. Therefore, future research may be conducted in the following directions: First, future studies could use larger sample data covering as many as possible typical learners to test the complexity of self-efficacy and expand the elements of self-efficacy by employing methods such as interviews or classroom (online and offline) observations to explore the various characteristics of these mixed profiles (see

Table 2). Second, given the significant individual differences in self-efficacy profiles and the intriguing and intertwining existence of average to moderately high self-efficacy profiles, teachers had better categorize learners into different profile with sounder and more convincing comparison and contrast. Lastly, since the belief systems of mixed self-efficacy learners under English writing MOOC environment remain relatively unclear or highly flexible, teachers are supposed to help learners adopt a sound self-efficacy belief system by incorporating positive language MOOC learning strategies and constructing sustainable online language learning environment, thereby enhancing positive emotional experiences (Dweck & Yeager, 2019) in college English writing MOOC based second language acquisition to better improve learners’ English writing proficiency.

References

- Alraimi, K.M.; Zo, H.; Ciganek, A.P. Understanding the MOOCs continuance: The role of openness and reputation. Computers & Education 2015, 80, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A. L2 writing self-efficacy and English writing achievement in MOOCs: A moderated mediating model. International Journal of Instruction 2025, 18, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agonacs, N.; Matos, J.F.; Bartalesi-Graf, D.; O’Steen, D.N. Are you ready? Self-determined learning readiness of language MOOC learners. Education and Information Technologies 2020, 25, 1161–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Zhang, H.; Akbar, A. The impact of self-efficacy on foreign language learning. Acta Psychologica 2024, 251, 104552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

- Bárcena, E.; Read, T.; Martín-Monje, E.; Castrillo, M.D. (2014). Analysing student participation in foreign language MOOCs: A case study. In U. Cress, & C. D. Kloos(Eds.), Proceedings of the European MOOC stakeholder summit 2014 (pp. 11–17). Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne.

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. (2011). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.H.; Byun, M. Nonnative English-speaking students’ lived learning experiences with MOOCs in a regular college classroom. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 2017, 18, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Investigating MOOCs through blog mining. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 2014, 15, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhou, R. The more the better? How excessive content and online interaction hinder the learning effectiveness of high-quality MOOCs. British Journal of Educational Technology 2024, 00, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compeau, D.R.; Higgins, C.A. Computer self-efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test. MIS Quarterly 1995, 19, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBusk-Lane, M.L.; Zumbrunn, S.; Bae, C.L.; Broda, M.D.; Bruning, R.; Sjogren, A.L. Variable- and person-centered approaches to examining construct-relevant multidimensionality in writing self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14, 1091894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A.; Siguaw, J.A. (2000). Introducing LISREL: A guide for the uninitiated. Sage.

- Djafri, F.; Wimbarti, S. Measuring foreign language anxiety among learners of different foreign languages: In Relation to Motivation and Perception of Teacher’s Behaviors. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education 2018, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Yeager., D.S. Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2019, 14, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gameel, B.G.; Wilkins, K.G. When it comes to MOOCs, where you are from makes a difference. Computers & Education 2019, 136, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sabitha, A.S. Deciphering the attributes of student retention in massive open online courses using data mining techniques. Education and Information Technologies 2019, 24, 1973–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Ting, P.F. Understanding MOOC continuance: An empirical examination of social support theory. Interactive Learning Environments 2018, 26, 1100–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.M.; Tsai, C.C.; Wang, J.C. Linking web-based learning self-efficacy and learning engagement in MOOCs: The role of online academic hardiness. Internet and Higher Education 2021, 51, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, J.; Nijkowska, J. Inclusive practices in teaching students with dyslexia: Second language teachers’ concerns, attitudes, and self-efficacy beliefs on a massive open online learning course. Teaching and Teacher Education 2017, 68, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Watson, S.L.; Watson, W.R. The influence of successful MOOC learners’ self-regulated learning strategies, self-efficacy, and task value on their perceived effectiveness of a massive open online course. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 2020, 21, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Han, Y. (2022). Learner-internal and learner-external factors for boredom amongst Chinese university EFL students. Applied Linguistics Review. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, S.; Yao, Q.; Zhu, Y. A Study on College Students’ Online Learning Behavior. E-Education Research 2013, 2013, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S. Exploring the ethical implications of MOOCs. Distance Education 2014, 35, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Li, Y.M.; Guo, J.H.; Laurillard, D.; Yang, M. A learning model for improving in-service teachers’ course completion in MOOCs. Interactive Learning Environments 2023, 31, 5940–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hocevar, D. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First- and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychological Bulletin 1985, 97, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyn, K. (2013). Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In T. D. Little (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods in psychology (vol. 2, pp. 551–611). Oxford University Press.

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B. (2017). Mplus users guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Pappano, L. The Year of the MOOC. The New York Times 2012, 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.-E.; Jiang, Y. Mining opinions on LMOOCs: Sentiment and content analyses of Chinese students’ comments in discussion forums. System 2022, 109, 102879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F.; Valiante, G. (2006). Self-efficacy beliefs and motivation in writing development. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 158–170). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Qian, Y.; Li, C.C.; Zou, X.G.; Feng, X.B.; Xiao, M.H.; Ding, Y.Q. Research on predicting learning achievement in a flipped classroom based on MOOCs by big data analysis. Computer Applications in Engineering Education 2022, 30, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekha, I.S.; Shetty, J.; Basri, S. Students’ continuance intention to use MOOCs: Empirical evidence from India. Education and Information Technologies 2023, 28, 4265–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hirschi, A.; Wang, M.; Valero, D.; Kauffeld, S. Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2020, 120, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, T.T.; Suhaimi, N.A.D.; Latif, L.A.; Abu Kassim, Z.; Fadzil, M. MOOCs readiness: The scenario in Malaysia. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 2019, 20, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. Examining the impact mechanism of social psychological motivations on individuals’ continuance intention of MOOCs: The moderating effect of gender. Internet Research 2018, 28, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; DiBenedetto, M.K. Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology 2020, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terras, M.M.; Ramsay, J. Massive open online courses (MOOCs): Insights and challenges from a psychological perspective. British Journal of Educational Technology 2015, 46, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.S.; Sun, P.P.; Xu, L. Conceptualizing writing self-efficacy in English as a foreign language contexts: Scale validation through structural equation modeling. TESOL Quarterly 2018, 52, 911–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.M.; Saab, N.; Admiraal, W. What rationale would work? Unfolding the role of learners’ attitudes and motivation in predicting learning engagement and perceived learning outcomes in MOOCs. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2024, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhu, C. MOOC-based flipped learning in higher education: Students’ participation, experience and learning performance. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2019, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, L.J. Profiling L2 students’ writing self-efficacy and its relationship with their writing strategies for self-regulated learning. System 2024, 122, 103253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yin, S.J.; Luo, M.F.; Yan, W.W. Learner control, user characteristics, platform difference, and their role in adoption intention for MOOC learning in China. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2017, 33, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).