Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

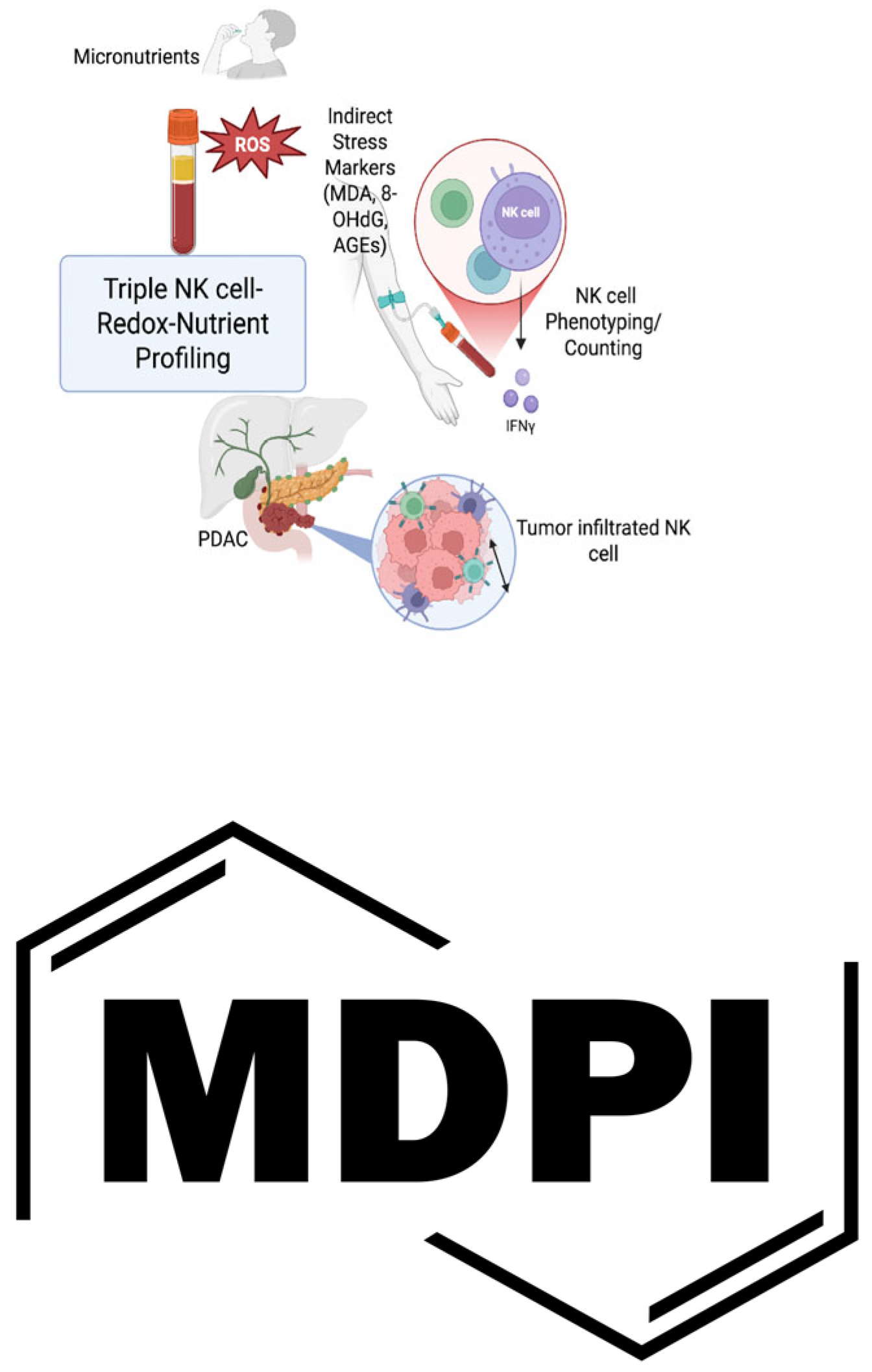

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Reactive Species Stress and PDAC

3. Nutrient Sensing and PDAC

3.2. AMPK in PDAC

4. NK Cells and PDAC

5. NK Cell and Oxidative Stress

5.1. NK Cell and ROS

5.2. NK Cell and NO

5.3. NK Cell and RSS

6. NK Cell and Nutrient Sensing

6.1. NK Cell and mTOR

6.2. NK cell and AMPK

7. Micronutrient-NK Cell Interaction

7.1. Vitamins

7.1.1. A Vitamin

7.1.2. D Vitamin

7.1.3. E Vitamin

7.1.4. Vitamin K (VK)

7.1.5. B Vitamin

7.1.6. C vitamin

7.2. Minerals

7.2.1. Calcium

7.2.2. Iron

7.2.3. Magnesium

7.2.4. Zinc, Copper, and Cadmium

7.2.5. Iodine

7.2.6. Selenium

7.2.7. Phosphorus

| Year, Reference | Cases | Cancer Type | Vitamin, Dosis | Mechanism | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986, [Fraker LD] | Athymic mice | Breast Cancer |

Retinol | Increasing the cytotoxicity measurements using a specific cytotoxicity assay | NK cell levels in immunocompetent mice are increased significantly after retinol treatment |

| 1989[prabhala] | In vitro (human PMBC) | Canthaxanthin (vitamin A) | Increased NK cell activation marker | ||

| 1991[Prabhala] | Clinical | Betacaroten (Vitamin A) | Increased NK cell cytotoxicity | ||

| 1991[Watson] | Clinical | Betacaroten (Vitamin A) | Increased NK cell number | ||

| 1992[Garewal] | Clinical | Betacaroten (Vitamin A) | Increased NK cell number | ||

| 1994[Ozturk] |

Preclinical | Zinc | Increased NK cell cytotoxicity | ||

| 1996[Santos] | Clinical | Betacaroten | Increased NKA | ||

| 1997[Adachi] | Clinical (a 16-months boy with Shwachman-Diamons syndrome) | Vit E | Increased NKA | ||

| 1998[Xu] | Preclinical | Zinc | Low Zinc resulted in decreased NKA | ||

| 2006[Troen] | Clinical | Folic Acid | Folate supplement in women with low folate diet, increased NKA, while in folate rich diet decrease the NKA | ||

| 2007[Giacconi] | Clinical (atherosclerotic patients) | Intercellular Magnesium (Mg) and zinc | Decreased level of Mg, zinc leading to decreased NKA | ||

| 2007, [Hanson MG] | 13 Cancer patients | CRC, Duke C and D | Vitamin E, 750 mg/day, for 2 weeks | A slight but consistent increase in NKG2D expression in all CRC patients | Vitamin E can be an adjuvant in cancer immunotherapy |

| 2022, [Lou Y] | Cell line | Breast Cancer | ATRA, 200 mcg/day from day before to 3 day after cryo-thermal therapy | Vitamin A can enhance NK cell cytotoxicity and improve survival | |

| 2022, [Kim KS] | Cell line | Prostate Cancer | Ferumoxytol (iron) | Increase IFNG and NKG2D | Ferumoxytol enhance NK cell cytotoxicity and significant tumor volume regression |

| 2023[christofyllakis] | Clinical | Vitamin D | Increased the expression of over 120 NKA genes | ||

| 2024, [He C] | Cell line | PDAC | B6 supplement | Intracellular glycogen breakdown and energy production | Increase NK cell cytotoxicity and inhibit tumor growth |

| 2024, [Partearroyo] | Preclinical (aged rats) | B12 | Decreased level of B12, leading to decreased NKA |

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Abbreviations

| alpha-TS | alpha-TS alpha-tocopheryl succinate |

| ATRA | All-trans-retinoic acid |

| Ca. | Calcium |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| CU | Copper |

| IFNG | Interferon Gamma |

| KIR | Killer Immunoglobulin-like Receptor |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| MSA | Methylseleninic acid |

| MTHFR | Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase |

| MTs | Metallothioneins |

| NKA | Natural Killer cell Activity |

| NKG2D | Natural killer group 2, member D |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood mononuclear cell |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| ROS. | Reactive Oxygen |

| TEPA | Tetraethylenepentamine Pentahydrochloride |

| TET | Ten-Eleven Translocation |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| Zn. | Zinc |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33.

- Wood, L.D.; Canto, M.I.; Jaffee, E.M.; Simeone, D.M. Pancreatic Cancer: Pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 386–402.

- Conroy, T.; Desseigne, F.; Ychou, M.; Bouché, O.; Guimbaud, R.; Bécouarn, Y.; Adenis, A.; Raoul, J.L.; Gourgou-Bourgade, S.; De La Fouchardière, C.; et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1817–1825.

- Fanijavadi, S.; Jensen, L.H. Dysbiosis–NK Cell Crosstalk in Pancreatic Cancer: Toward a Unified Biomarker Signature for Improved Clinical Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 730. [CrossRef]

- Hayyan, M., Hashim, M. A., & AlNashef, I. M. (2016). Superoxide ion: Generation and chemical implications. Chemical Reviews, 116(5), 3029–3085. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S., et al. (2022). Role of ROS in the development of chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Antioxidants, 11(7), 1355.); (Galli & Ruggiero.

- Xu, G., et al. (2023). Nitric oxide in the tumor microenvironment: Implications for therapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Letters, 529, 172-181.

- Zhang, X., et al. (2023). Hydrogen sulfide as a potential therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 14, 725908.).

- Jiang, H., et al. (2023). The dual role of nitric oxide in immune modulation in pancreatic cancer. Journal of Immunology, 210(2), 319-328.

- Galli, F., & Ruggiero, A. Hydrogen sulfide and its role in redox signaling in immune cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—General Subjects, 2016, 1860(10), 2187-2196].

- Gong J, Robbins LA, Lugea A, Waldron RT, Jeon CY, Pandol SJ. Diabetes, pancreatic cancer, and metformin therapy. Front Physiol (2014) 5:426. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00426.

- Iriana S, Ahmed S, Gong J, Annamalai AA, Tuli R, Hendifar AE. Targeting mTOR in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2016 Apr 25;6:99. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Friedman MD, Jeevan DS, Tobias M, Murali R and Jhanwar-Uniyal M: Targeting cancer stem cells in glioblastoma multiforme using mTOR inhibitors and the differentiating agent all-trans retinoic acid. Oncol Rep 30: 1645-1650, 2013.

- Fanijavadi, S.; Thomassen, M.; Jensen, L.H. Targeting Triple NK Cell Suppression Mechanisms: A Comprehensive Review of Biomarkers in Pancreatic Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 515. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S. U., et al. (2022). Therapeutic resistance in pancreatic cancer: Role of RNS and NO in resistance to gemcitabine. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 746218.

- Li, Y., et al. (2022). Hydrogen sulfide: A novel modulator of redox signaling in pancreatic cancer. Redox Biology, 45, 102053.

- Muller, L., et al. (2023). Reactive sulfur species in cancer and their modulation: Implications for therapy. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 39(5), 547-560.).

- Lal MK, Sharma E, Tiwari RK, Devi R, Mishra UN, Thakur R, Gupta R, Dey A, Lal P, Kumar A, Altaf MA, Sahu DN, Kumar R, Singh B, Sahu SK. Nutrient-Mediated Perception and Signalling in Human Metabolism: A Perspective of Nutrigenomics. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 25;23(19):11305. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911305. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vaziri-Gohar, A., Cassel, J., Mohammed, F.S. et al. Limited nutrient availability in the tumor microenvironment renders pancreatic tumors sensitive to allosteric IDH1 inhibitors. Nat Cancer 3, 852–865 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Saravia J, Raynor JL, Chapman NM, Lim SA, Chi H. Signaling networks in immunometabolism. Cell Res. 2020 Apr;30(4):328-342. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E. Current development of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov (2006) 5:671–88. [CrossRef]

- Populo H, Lopes JM, Soares P. The mTOR signalling pathway in human cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2012) 13:1886–918. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Wang, B., Maswikiti, E.P. et al. AMPK–a key factor in crosstalk between tumor cell energy metabolism and immune microenvironment?. Cell Death Discov. 10, 237 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J. Hilbert, F. Genevaux, S. Höfer, L. Krauß, F. Schicktanz, C. T. Contreras, S. Jansari, A. Papargyriou, T. Richter, A. M. Alfayomy, C. Falcomatà, C. Schneeweis, F. Orben, R. Öllinger, F. Wegwitz, A. Boshnakovska, P. Rehling, D. Müller, P. Ströbel, V. Ellenrieder, L. Conradi, E. Hessmann, M. Ghadimi, M. Grade, M. Wirth, K. Steiger, R. Rad, B. Kuster, W. Sippl, M. Reichert, D. Saur, G. Schneider, A Novel AMPK Inhibitor Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Ferroptosis Induction. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2307695. [CrossRef]

- R S, et al. (2023) The total mass, number, and distribution of immune cells in the human body. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120.

- Huber, M.; Brehm, C.U.; Gress, T.M.; Buchholz, M.; Alashkar Alhamwe, B.; von Strandmann, E.P.; Slater, E.P.; Bartsch, J.W.; Bauer, C.; Lauth, M. The Immune Microenvironment in Pancreatic Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7307. [CrossRef]

- TJ L, A B, K R (2022) Natural killer cells in antitumor adoptive cell immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 22(10). [CrossRef]

- E V, L R, E NM, et al. (2024) Natural killer cell therapies. Nature 626. URL . [CrossRef]

- J C, F G, et al. (2022a) Natural killer cells: a promising immunotherapy for cancer. J Transl Med 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Ran G, q LY, et al. (2022) Natural killer cell homing and trafficking in tissues and tumors: from biology to application. Sig Transduct Target Ther 7(205). URL . [CrossRef]

- M‘ F, PM A, KY T (2023) Potentiation of natural killer cells to overcome cancer resistance to NK cell-based therapy and to enhance antibody-based immunotherapy. Front Immunol . [CrossRef]

- M G, A R (2018) Effect of Natural Compounds on NK Cell Activation. J Immunol Res . [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Micó O, Aceves C. Micronutrients and Breast Cancer Progression: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2020 Nov 25;12(12):3613. doi: 10.3390/nu12123613.

- N D, F G, et al. (2021) NK Cell Therapy: A Rising Star in Cancer Treatment. Cancers (Basel) 13(16). [CrossRef]

- KN P, A K, et al. (1999) High doses of multiple antioxidant vitamins: essential ingre- dients in improving the efficacy of standard cancer therapy. J Am Coll Nutr 18(1). [CrossRef]

- KN P, WC C, et al. (2002) Pros and cons of antioxidant use during radiation therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 28(2). [CrossRef]

- CB A, GR Z, et al. (2020) Dietary Supplement Use During Chemotherapy and Survival Outcomes of Patients with Breast Cancer Enrolled in a Cooperative Group Clinical Trial (SWOG S0221). J Clin Oncol 38(8). [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, H., et al. (2024). Spatiotemporal Characteristics Determining the Multifaceted Nature of Reactive Oxygen, Nitrogen, and Sulfur Species in Relation to Proton Homeostasis. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling.

- Yang Y, Neo SY, Chen Z, Cui W, Chen Y, Guo M, Wang Y, Xu H, Kurzay A, Alici E, Holmgren L, Haglund F, Wang K, Lundqvist A. Thioredoxin activity confers resistance against oxidative stress in tumor-infiltrating NK cells. J Clin Invest. 2020 Oct 1;130(10):5508-5522. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chia, D., et al. (2025). Navigating the dichotomy of reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species: detection strategies and therapeutic interventions. RSC Chemical Biology].

- Mariappan, M. M., & Balasubramanian, K. (2017). Nitrosative stress in immune responses: The role of reactive nitrogen species in NK cell function. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 26(11), 595-608., Reference: Ju, R. L., & Wu, F. (2018). Nitrosative stress and the role of nitric oxide in natural killer cell function. Journal of Immunology Research, 2018, Article ID 6234321.

- Andrés, C. M. C., et al. (2022). The Role of Reactive Species on Innate Immunity. Vaccines, 10(10), 1735. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., & Wu, L. (2015). Hydrogen sulfide and its effects on immune cell function. Frontiers in Immunology, 6, 2. [CrossRef]

- Borde S, Matosevic S. Metabolic adaptation of NK cell activity and behavior in tumors: challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2023 Nov;44(11):832-848. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang C, Tsaih SW, Lemke A, Flister MJ, Thakar MS, Malarkannan S. mTORC1 and mTORC2 differentially promote natural killer cell development. Elife. 2018 May 29;7:e35619. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ouissam AJ, Hind C, Sami Aziz B, Said A. Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in pancreatic cancer: is it a worthwhile endeavor? Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2024 Oct 4;16:17588359241284911. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- R.H. P, G.S H, et al. (1991) The effects of 13-cis-retinoic acid and beta-carotene on cellular immunity in humans. Cancer 67. [CrossRef]

- Ashley H Davis-Yadley, Mokenge P Malafa, Vitamins in Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Underlying Mechanisms and Future Applications, Advances in Nutrition, Volume 6, Issue 6, 2015, Pages 774-802, ISSN 2161-8313. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2161831323001242). [CrossRef]

- N T, D S, et al. (2022) Vitamin A in health care: Suppression of growth and induction of differentiation in cancer cells by vitamin A and its derivatives and their mechanisms of action. Pharmacol Ther . [CrossRef]

- MV G, PN H, et al. (2020) Current Trends in ATRA Delivery for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics pp 12–8. [CrossRef]

- M.A. C, A Z, M. T, et al. (2024) Cellular and micro-environmental responses influencing the antitumor activity of all-trans retinoic acid in breast cancer. Cell Commun Signal 22(127). URL . [CrossRef]

- J Y, Y Z, et al. (2022c) β-Carotene Supplementation and Risk of Cardiovascular Dis- ease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 14(6). [CrossRef]

- The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(15):1029–1035. [CrossRef]

- Omenn GS, et al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(18):1150–1155. [CrossRef]

- Y L, P P, et al. (2022) Combining all-trans retinoid acid treatment targeting myeloid- derived suppressive cells with cryo-thermal therapy enhances antitumor immunity in breast cancer. Front Immunol 13. [CrossRef]

- A B, A K, et al. (2014) Saffron and natural carotenoids: Biochemical activities and anti- tumor effects. Biochim Biophys Acta 1854(1). [CrossRef]

- R.H. P, V. M, et al. (1989) Enhancement of the expression of activation markers of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by in vitro culture with retinoids and carotenoids J Leuk Biol 45. [CrossRef]

- R.R. W, R.H. P, et al. (1991) Effects of β-carotene on lymphocyte subpopulations in elderly humans: evidence for a dose-response relationship. Am J Clin Nutr 53.

- H.S. G, N.M. A, et al. (1992) A preliminary trial of beta carotene in subjects infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Nutr 122. [CrossRef]

- Grudzien, Malgorzata, Rapak, Andrzej, Effect of Natural Compounds on NK Cell Activation, Journal of Immunology Research, 2018, 4868417, 11 pages, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H., et al. (2023). Vitamin A modulates immune cell responses through regulation of reactive oxygen species. Frontiers in Immunology, 14, 947021.

- Müller, L., et al. (2022). Vitamin A and its impact on nitric oxide production in immune cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(12), 6924.

- Kolluru, G. K., et al. (2023). Retinoic acid and the regulation of reactive sulfur species in immune function. Redox Biology, 55, 102380.

- Zhang T, Chen H, Qin S, Wang M, Wang X, Zhang X, Liu F, Zhang S. The association between dietary vitamin A intake and pancreatic cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 11 studies. Biosci Rep. 2016 Nov 22;36(6): e00414. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guan J, Zhang H, Wen Z, Gu Y, Cheng Y, Sun Y, Zhang T, Jia C, Lu Z, Chen J. Retinoic acid inhibits pancreatic cancer cell migration and EMT through the downregulation of IL-6 in cancer associated fibroblast cells. Cancer Lett. 2014 Apr 1;345(1):132-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pili R, Salumbides B, Zhao M, Altiok S, Qian D, Zwiebel J, Carducci MA, Rudek MA. Phase I study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat in combination with 13-cis retinoic acid in patients with solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2012 Jan 3;106(1):77-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- HM K, B B, et al. (2020) Phase I clinical trial repurposing all-trans retinoic acid as a stromal targeting agent for pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun. 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Kocher HM, Basu B, Froeling FEM, Sarker D, Slater S, Carlin D, deSouza NM, De Paepe KN, Goulart MR, Hughes C, Imrali A, Roberts R, Pawula M, Houghton R, Lawrence C, Yogeswaran Y, Mousa K, Coetzee C, Sasieni P, Prendergast A, Propper DJ. Phase I clinical trial repurposing all-trans retinoic acid as a stromal targeting agent for pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun. 2020 Sep 24;11(1):4841. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- K C, F N, M B, et al. (2023) Vitamin D Enhances Immune Effector Pathways of NK Cells Thus Providing a Mechanistic Explanation for the Increased Effectiveness of Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies. Nutrients 15(16). [CrossRef]

- Sheeley MP, Andolino C, Kiesel VA, Teegarden D. Vitamin D regulation of energy metabolism in cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 2022 Jun;179(12):2890-2905. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- PD C, WY C, et al. (2020) Effect of Vitamin D3 Supplements on Development of Advanced Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of the VITAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 3(11). [CrossRef]

- JD S, JE M, R S (2020) Vitamin D and Clinical Cancer Outcomes: A Review of Meta-Analyses. JBMR Plus 5(1). [CrossRef]

- GY L, CY P, et al. (2018) Differential effect of dietary vitamin D supplementation on natural killer cell activity in lean and obese mice. J Nutr Biochem 55. [CrossRef]

- F N, F A (2018) Determination of optimum vitamin D3 levels for NK cell-mediated rituximab- and obinutuzumab-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Cancer Immunol Immunother 67(11). [CrossRef]

- S Y, MT C (2008) The vitamin D receptor is required for iNKT cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(13). [CrossRef]

- Mijatović, S.; Savić-Radojević, A.; Plješa-Ercegovac, M.; Simić, T.; Nicoletti, F.; Maksimović-Ivanić, D. The Double-Faced Role of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species in Solid Tumors. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 374. [CrossRef]

- Ravid A, Koren R. The role of reactive oxygen species in the anticancer activity of vitamin D. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2003;164:357-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenercioglu AK. The Anti-Inflammatory Roles of Vitamin D for Improving Human Health. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024 Nov 26;46(12):13514-13525. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quigley M, Rieger S, Capobianco E, Wang Z, Zhao H, Hewison M, Lisse TS. Vitamin D Modulation of Mitochondrial Oxidative Metabolism and mTOR Enforces Stress Adaptations and Anticancer Responses. JBMR Plus. 2021 Dec 1;6(1):e10572. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Yanan and He, Qingmin and Rong, Kang and Zhu, Mingyang and Zhao, Xiaoxiao and Zheng, Pengyuan and Mi, Yang; Vitamin D3 promotes gastric cancer cell autophagy by mediating p53/AMPK/mTOR signaling; Frontiers in Pharmacology; Volume 14—2023, 2024; https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1338260; ISSN 1663-9812. [CrossRef]

- Moukayed, M.; Grant, W.B. Molecular Link between Vitamin D and Cancer Prevention. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3993-4021. [CrossRef]

- Colston KW, James SY, Ofori-Kuragu EA, Binderup L, Grant AG. Vitamin D receptors and anti-proliferative effects of vitamin D derivatives in human pancreatic carcinoma cells in vivo and in vitro. Br J Cancer. 1997;76(8):1017-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Evans TR, Colston KW, Lofts FJ, Cunningham D, Anthoney DA, Gogas H, de Bono JS, Hamberg KJ, Skov T, Mansi JL. A phase II trial of the vitamin D analogue Seocalcitol (EB1089) in patients with inoperable pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002 Mar 4;86(5):680-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- A A, AJ K (2019) Vitamin E and its anticancer effects. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 59(17). [CrossRef]

- Q J (2019) Natural forms of vitamin E and metabolites-regulation of cancer cell death and underlying mechanisms. IUBMB Life 71(4). [CrossRef]

- KN P, B K, et al. (2003) Alpha-tocopheryl succinate, the most effective form of vitamin E for adjuvant cancer treatment: a review. J Am Coll Nutr 22(2). [CrossRef]

- CS Y, N S, AN K (????) Does vitamin E prevent or promote cancer? Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 5(5). [CrossRef]

- MK A, HS Z, M AW (2000) Vitamin E and beta-carotene affect natural killer cell function. Int J Food Sci Nutr.

- MG H, V O, et al. (2007) A short-term dietary supplementation with high doses of vitamin E increases NK cell cytolytic activity in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother 56(7). [CrossRef]

- N A, M M, et al. (1997) Depressed natural killer cell activity due to decreased natural killer cell population in a vitamin E-deficient patient with Shwachman syndrome: reversible natural killer cell abnormality by alpha-tocopherol supplementation. Eur J Pediatr.

- Ehizuelen Ebhohimen, I., Stephen Okanlawon, T., Ododo Osagie, A., & Norma Izevbigie, O. (2021). Vitamin E in Human Health and Oxidative Stress Related Diseases. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Jagdeep K. Sandhu, Arsalan S. Haqqani, H. Chaim Birnboim, Effect of Dietary Vitamin E on Spontaneous or Nitric Oxide Donor-Induced Mutations in a Mouse Tumor Model, JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Volume 92, Issue 17, 6 September 2000, Pages 1429–1433. [CrossRef]

- Fabio Hecht, Marco Zocchi, Fatemeh Alimohammadi, Isaac S. Harris, Regulation of antioxidants in cancer, Molecular Cell, Volume 84, Issue 1, 2024, Pages 23-33, ISSN 1097-2765. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1097276523009176. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Hou L, Song H, Xu P, Sun Y, Wu K. Akt/AMPK/mTOR pathway was involved in the autophagy induced by vitamin E succinate in human gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2017 Jan;424(1-2):173-183. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein EA, Thompson IM Jr, Tangen CM, et al. Vitamin E and the Risk of Prostate Cancer: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2011;306(14):1549–1556. [CrossRef]

- Husain K, Francois RA, Yamauchi T, Perez M, Sebti SM, Malafa MP. Vitamin E δ-tocotrienol augments the antitumor activity of gemcitabine and suppresses constitutive NF-κB activation in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011 Dec;10(12):2363-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kunnumakkara AB, Sung B, Ravindran J, Diagaradjane P, Deorukhkar A, Dey S, Koca C, Yadav VR, Tong Z, Gelovani JG, Guha S, Krishnan S, Aggarwal BB. {Gamma}-tocotrienol inhibits pancreatic tumors and sensitizes them to gemcitabine treatment by modulating the inflammatory microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2010 Nov 1;70(21):8695-705. Erratum in: Cancer Res. 2018 Sep 1;78(17):5181. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1826. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gröber U, Reichrath J, Holick MF, Kisters K. Vitamin K: an old vitamin in a new perspective. Dermatoendocrinol. 2015 Jan 21;6(1):e968490. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anqi Chen, Jialu Li, Nianxuan Shen, Haifeng Huang, Qinglei Hang, Vitamin K: New insights related to senescence and cancer metastasis, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—Reviews on Cancer, Volume 1879, Issue 2, 2024, 189057, ISSN 0304-419X, (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304419X23002068) . [CrossRef]

- Gergues Marina , Bari Rafijul , Koppisetti Sharmila , Gosiewska Anna , Kang Lin , Hariri Robert J. Senescence, NK cells, and cancer: navigating the crossroads of aging and diseaseFrontiers in Immunology; Volume 16—2025; https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1565278; ISSN=1664-3224. [CrossRef]

- Textor S, Bossler F, Henrich KO, Gartlgruber M, Pollmann J, Fiegler N, Arnold A, Westermann F, Waldburger N, Breuhahn K, Golfier S, Witzens-Harig M, Cerwenka A. The proto-oncogene Myc drives expression of the NK cell-activating NKp30 ligand B7-H6 in tumor cells. Oncoimmunology. 2016 Jul 28;5(7): e1116674. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ponti, C., Gibellini, D., Boin, F., Melloni, E., Manzoli, F.A., Cocco, L., Zauli, G. and Vitale, M. (2002), Role of CREB transcription factor in c-fos activation in natural killer cells. Eur. J. Immunol., 32: 3358-3365. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Nakamura H, Yamamoto T, Ikeda N, Saito M, Ohno M, Hara N, Imanishi H, Shimomura S, Yamamoto T, Sakai T, Nishiguchi S, Hada T. Vitamin K2 inhibits the proliferation of HepG2 cells by up-regulating the transcription of p21 gene. Hepatol Res. 2007 May;37(5):360-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diana Schnoegl, Angela Hiesinger, Nicholas D Huntington, Dagmar Gotthardt, AP-1 transcription factors in cytotoxic lymphocyte development and antitumor immunity, Current Opinion in Immunology, Volume 85, 2023, 102397, ISSN 0952-7915. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0952791523001164). [CrossRef]

- Article Source: Vitamin K2 Induces Mitochondria-Related Apoptosis in Human Bladder Cancer Cells via ROS and JNK/p38 MAPK Signal Pathways Duan F, Yu Y, Guan R, Xu Z, Liang H, et al. (2016) Vitamin K2 Induces Mitochondria-Related Apoptosis in Human Bladder Cancer Cells via ROS and JNK/p38 MAPK Signal Pathways. PLOS ONE 11(8): e0161886. [CrossRef]

- Duan F, Yu Y, Guan R, Xu Z, Liang H, et al. (2016) Vitamin K2 Induces Mitochondria-Related Apoptosis in Human Bladder Cancer Cells via ROS and JNK/p38 MAPK Signal Pathways. PLOS ONE 11(8): e0161886. [CrossRef]

- Duan, F., Mei, C., Yang, L. et al. Vitamin K2 promotes PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α-mediated glycolysis that leads to AMPK-dependent autophagic cell death in bladder cancer cells. Sci Rep 10, 7714 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Showalter SL, Wang Z, Costantino CL, Witkiewicz AK, Yeo CJ, Brody JR, Carr BI. Naturally occurring K vitamins inhibit pancreatic cancer cell survival through a caspase-dependent pathway. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Apr;25(4):738-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei G, Wang M, Carr BI. Sorafenib combined vitamin K induces apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer cell lines through RAF/MEK/ERK and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2010 Jul;224(1):112-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Osada S, Tomita H, Tanaka Y, Tokuyama Y, Tanaka H, Sakashita F, Takahashi T. The utility of vitamin K3 (menadione) against pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008 Jan-Feb;28(1A):45-50. [PubMed]

- Hanna M, Jaqua E, Nguyen V, Clay J. B Vitamins: Functions and Uses in Medicine. Perm J. 2022 Jun 29;26(2):89-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- AM T, B M, B S, et al. (2006) Unmetabolized folic acid in plasma is associated with reduced natural killer cell cytotoxicity among postmenopausal women. J Nutr 136(1). [CrossRef]

- CT P, DA R, et al. (2020) B Vitamins and Their Role in Immune Regulation and Cancer. Nutrients. Nutrients 12(11). [CrossRef]

- X C, H A, et al. (2019) Association of intake folate and related gene polymorphisms with breast cancer. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 65.

- Sohn Ji Yun, Kim Eun Young, Jeong Jae-Hwang, Kim Dae Joong, Nam Sang Yoon, Lee Hyun Jik, Lee Beom Jun. Protective effects of folic acid on colon carcinogenesis induced by azoxymethane in mice. J Biomed Transl Res 2021;22(3):111-120. [CrossRef]

- H S, J W, et al. (2016) High folic acid intake reduces natural killer cell cytotoxicity in aged mice. J Nutr Biochem . [CrossRef]

- J T, MHSMMTTTSKHKubota K, et al. (1999) Immunomodulation by vitamin B12: augmentation of CD8+ T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cell activity in vitamin B12-deficient patients by methyl-B12 treatment. . Clin Exp Immunol 116(1).

- T P, U’beda N, et al. (2013) Vitamin B (12) and folic acid imbalance modifies NK cyto- toxicity, lymphocytes B and lymphoprolipheration in aged rats. Nutrients. 5(12). [CrossRef]

- Frost, Z.; Bakhit, S.; Amaefuna, C.N.; Powers, R.V.; Ramana, K.V. Recent Advances on the Role of B Vitamins in Cancer Prevention and Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1967. [CrossRef]

- Xie, S., Tan, M., Li, H. et al. Study on the correlation between B vitamins and breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int 23, 22 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ayuk S.M., Abrahamse H. mTOR Signaling Pathway in Cancer Targets Photodynamic Therapy In Vitro. Cells. 2019;8:431. [CrossRef]

- Ueno M, Okusaka T, Omuro Y, Isayama H, Fukutomi A, Ikeda M, Mizuno N, Fukuzawa K, Furukawa M, Iguchi H, Sugimori K, Furuse J, Shimada K, Ioka T, Nakamori S, Baba H, Komatsu Y, Takeuchi M, Hyodo I, Boku N. A randomized phase II study of S-1 plus oral leucovorin versus S-1 monotherapy in patients with gemcitabine-refractory advanced pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016 Mar;27(3):502-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- C H, D W, SK S, et al. (2024) Vitamin B6 Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Hampers Antitumor Functions of NK Cells. Cancer Discov. 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Jin-Peng Yong, Xiao-Yan Mu, Chao-Feng Zhou, Ke-Ke Zhang, Jie-Qiong Gao, Zhi-Zhong Guo, Shi-Fan Zhou, Zhen Ma, Radiofrequency ablation of liver metastases in a patient with pancreatic cancer and long-term survival: A case report, World Journal of Clinical Cases, 13, 20, (2025). [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211. [CrossRef]

- Wilson MK, Baguley BC, Wall C, Jameson MB, Findlay MP. Review of high-dose intravenous vitamin C as an anticancer agent. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014 Mar;10(1):22-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, B., Van Riper, J.M., Cantley, L.C. et al. Targeting cancer vulnerabilities with high-dose vitamin C. Nat Rev Cancer 19, 271–282 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Huijskens MJ, Walczak M, Sarkar S, Atrafi F, Senden-Gijsbers BL, Tilanus MG, Bos GM, Wieten L, Germeraad WT. Ascorbic acid promotes proliferation of natural killer cell populations in culture systems applicable for natural killer cell therapy. Cytotherapy. 2015 May;17(5):613-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M V, J F (2021) The Role of Vitamin C in Cancer Prevention and Therapy: A Litera- ture Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 10(12). [CrossRef]

- J GM, S C, et al. (2022b) Ascorbate as a Bioactive Compound in Cancer Ther- apy: The Old Classic Strikes Back. Molecules 27(12). [CrossRef]

- CY W, B Z, et al. (2020) Ascorbic Acid Promotes KIR Demethylation during Early NK Cell Differentiation. J Immunol 205(6). [CrossRef]

- Du J, Martin SM, Levine M, Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Wang SH, Taghiyev AF, Du C, Knudson CM, Cullen JJ. Mechanisms of ascorbate-induced cytotoxicity in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 Jan 15;16(2):509-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qin S, Wang G, Chen L, Geng H, Zheng Y, Xia C, Wu S, Yao J, Deng L. Pharmacological vitamin C inhibits mTOR signaling and tumor growth by degrading Rictor and inducing HMOX1 expression. PLoS Genet. 2023 Feb 14;19(2):e1010629. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Espey MG, Chen P, Chalmers B, Drisko J, Sun AY, Levine M, Chen Q. Pharmacologic ascorbate synergizes with gemcitabine in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011 Jun 1;50(11):1610-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pereira M, Cardeiro M, Frankel L, Greenfield B, Takabe K, Rashid OM. Increased Vitamin C Intake Is Associated With Decreased Pancreatic Cancer Risk. World J Oncol. 2024 Aug;15(4):543-549. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fan, H., Kou, J., Han, D. et al. Association between vitamin C intake and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep 5, 13973 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Conte E, Rizzolo E, Flower G, Legacy M, Seely D. Intravenous Vitamin C in Cancer Care: Evidence Review and Practical Guidance for Integrative Oncology Practitioners. CANDJ [Internet]. 2024 Mar. 21 [cited 2025 Apr. 18];31(1):2-18. Available from: https://candjournal.ca/index.php/candj/article/view/149.

- Bodeker KL, Smith BJ, Berg DJ, Chandrasekharan C, Sharif S, Fei N, Vollstedt S, Brown H, Chandler M, Lorack A, McMichael S, Wulfekuhle J, Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Allen BG, Caster JM, Dion B, Kamgar M, Buatti JM, Cullen JJ. A randomized trial of pharmacological ascorbate, gemcitabine, and nab-paclitaxel for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Redox Biol. 2024 Nov;77:103375. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Polireddy, K., Dong, R., Reed, G. et al. High Dose Parenteral Ascorbate Inhibited Pancreatic Cancer Growth and Metastasis: Mechanisms and a Phase I/IIa study. Sci Rep 7, 17188 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Seyed Mohammad Taghi Gharibzahedi, Seid Mahdi Jafari, The importance of minerals in human nutrition: Bioavailability, food fortification, processing effects and nanoencapsulation, Trends in Food Science & Technology, Volume 62, 2017, Pages 119-132, ISSN 0924-2244, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924224416306203. [CrossRef]

- Janakiram NB, Mohammed A, Madka V, Kumar G, Rao CV. Prevention and treatment of cancers by immune modulating nutrients. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016 Jun;60(6):1275-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pravina, P., Sayaji, D. and Avinash, M. (2013) Calcium and Its Role in Human Body. International Journal of Research in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences, 4, 659-668.

- Zhang M, Song R (2019) Calcium-Overload-Mediated Tumor Therapy by Calcium Peroxide Nanoparticles. CelPress URL . [CrossRef]

- EC S, B Q, M H (2013) Calcium, cancer and killing: the role of calcium in killing cancer cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833(7). [CrossRef]

- A MP, SC C, et al. (2011) ORAI1-mediated calcium influx is required for human cytotoxic lymphocyte degranulation and target cell lysis Proc. Natl Acad Sci 108.

- Görlach A, Bertram K, Hudecova S, Krizanova O. Calcium and ROS: A mutual interplay. Redox Biol. 2015 Dec;6:260-271. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rizzuto, R., De Stefani, D., Raffaello, A. et al. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13, 566–578 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Huang Xuan , Reye Gina , Momot Konstantin I. , Blick Tony , Lloyd Thomas , Tilley Wayne D. , Hickey Theresa E. , Snell Cameron E. , Okolicsanyi Rachel K. , Haupt Larisa M. , Ferro Vito , Thompson Erik W. , Hugo Honor J; Heparanase Promotes Syndecan-1 Expression to Mediate Fibrillar Collagen and Mammographic Density in Human Breast Tissue Cultured ex vivo; Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology; Volume 8—2020 https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cell-and-developmental-biology/articles/10.3389/fcell.2020.00599; 10.3389/fcell.2020.00599; ISSN=2296-634X.

- Lin, Lan et al.; TRPV4 enhances the synthesis of fatty acids to drive the progression of ovarian cancer through the calcium-mTORC1/SREBP1 signaling pathway; iScience, Volume 26, Issue 11, 108226.

- Bettaieb L, Brulé M, Chomy A, Diedro M, Fruit M, Happernegg E, Heni L, Horochowska A, Housseini M, Klouyovo K, Laratte A, Leroy A, Lewandowski P, Louvieaux J, Moitié A, Tellier R, Titah S, Vanauberg D, Woesteland F, Prevarskaya N, Lehen’kyi V. Ca2+ Signaling and Its Potential Targeting in Pancreatic Ductal Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Jun 21;13(12):3085. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- D.R. Principe,A.F. Aissa,S. Kumar,T.N.D. Pham,P.W. Underwood,R. Nair,R. Ke,B. Rana,J.G. Trevino,H.G. Munshi,E.V. Benevolenskaya,& A. Rana, Calcium channel blockers potentiate gemcitabine chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119 (18) e2200143119. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Fong ZV, Severs G, Moir J, White S, Qadan M, Tingle S. Calcium channel blockers are associated with improved survival in pancreatic cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy and resection. HPB (Oxford). 2024 Mar;26(3):418-425. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami A, Mohammadzadeh M, Abdi F, Paydareh A, Khalesi S, Hejazi E. Calcium Intake and the Pancreatic Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Clin Nutr Res. 2024 Oct 30;13(4):284-294. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abbaspour N, Hurrell R, Kelishadi R. Review on iron and its importance for human health. J Res Med Sci. 2014 Feb;19(2):164-74. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Q G, L L, S H, et al. (2021) The Role of Iron in Cancer Progression. Front Oncol . [CrossRef]

- Kim K, Choi B, et al. (2022) Enhanced natural killer cell anti-tumor activity with nanoparticles mediated ferroptosis and potential therapeutic application in prostate cancer. J Nanobiotechnol 20(428). URL . [CrossRef]

- An, X., Yu, W., Liu, J. et al. Oxidative cell death in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Dis 15, 556 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q., Meng, Y., Li, D. et al. Ferroptosis in cancer: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Sig Transduct Target Ther 9, 55 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Shang C, Zhou H, Liu W, Shen T, Luo Y, Huang S. Iron chelation inhibits mTORC1 signaling involving activation of AMPK and REDD1/Bnip3 pathways. Oncogene. 2020 Jul;39(29):5201-5213. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jain V, Amaravadi RK. Pumping Iron: Ferritinophagy Promotes Survival and Therapy Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2022 Sep 2;12(9):2023-2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Julián-Serrano S, Yuan F, Barrett MJ, Pfeiffer RM, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ. Hemochromatosis, Iron Overload-Related Diseases, and Pancreatic Cancer Risk in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021 Nov;30(11):2136-2139. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iron and Lipocalin-2 Modulate Cellular Responses in the Tumor Micro-environment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma; Valentina Pita-Grisanti, Andrew W. Dangel, Kristyn Gumpper, Andrea Ludwig, Olivia Ueltschi, Xiaokui Mo, Maciej Pietrzak, Amy Webb, Rosa F. Hwang, Madelyn Traczek, Niharika Badi, Zobeida Cruz-Monserrate; bioRxiv 2020.01.14.907188;. [CrossRef]

- Osmola M, Gierej B, Mleczko-Sanecka K, Jończy A, Ciepiela O, Kraj L, Ziarkiewicz-Wróblewska B, Basak GW. Anemia, Iron Deficiency, and Iron Regulators in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Patients: A Comprehensive Analysis. Curr Oncol. 2023 Aug 18;30(8):7722-7739. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- S A, S K, et al. (2023) A narrative review on the role of magnesium in immune regulation, inflammation, infectious diseases, and cancer. J Health Popul Nutr 42(1). [CrossRef]

- Huang, WQ., Long, WQ., Mo, XF. et al. Direct and indirect associations between dietary magnesium intake and breast cancer risk. Sci Rep 9, 5764 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Chaigne-Delalande B, Li FY, O’Connor GM, Lukacs MJ, Jiang P, Zheng L, Shatzer A, Biancalana M, Pittaluga S, Matthews HF, Jancel TJ, Bleesing JJ, Marsh RA, Kuijpers TW, Nichols KE, Lucas CL, Nagpal S, Mehmet H, Su HC, Cohen JI, Uzel G, Lenardo MJ. Mg2+ regulates cytotoxic functions of NK and CD8 T cells in chronic EBV infection through NKG2D. Science. 2013 Jul 12;341(6142):186-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fujita, K., Shindo, Y., Katsuta, Y. et al. Intracellular Mg2+ protects mitochondria from oxidative stress in human keratinocytes. Commun Biol 6, 868 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kwesiga MP, Gillette AA, Razaviamri F, Plank ME, Canull AL, Alesch Z, He W, Lee BP, Guillory RJ 2nd. Biodegradable magnesium materials regulate ROS-RNS balance in pro-inflammatory macrophage environment. Bioact Mater. 2022 Nov 17;23:261-273. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xie J, Cheng C, Zhu XY, Shen YH, Song LB, Chen H, Chen Z, Liu LM, Meng ZQ. Magnesium transporter protein solute carrier family 41 member 1 suppresses human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through magnesium-dependent Akt/mTOR inhibition and bax-associated mitochondrial apoptosis. Aging (Albany NY). 2019 May 8; 11:2681-2698 . [CrossRef]

- Dibaba D, Xun P, Yokota K, White E, He K. Magnesium intake and incidence of pancreatic cancer: the VITamins and Lifestyle study. Br J Cancer. 2015 Dec 1;113(11):1615-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xianpeng Qin, Jing Chen, Guiqing Jia, Zhou Yang,Dietary Factors and Pancreatic Cancer Risk: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Prospective Observational Studies,Advances in Nutrition,Volume 14, Issue 3,2023,Pages 451-464,ISSN 2161-8313. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2161831323002636). [CrossRef]

- H.E. Heilmaier, G.A. Drasch, E. Kretschmer, K.H. Summer, Metallothionein, cadmium, copper and zinc levels of human and rat tissues, Toxicology Letters,Volume 38, Issue 3,1987,Pages 205-211,ISSN 0378-4274. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378427487900014. [CrossRef]

- Nordberg M, Nordberg GF. Metallothionein and Cadmium Toxicology-Historical Review and Commentary. Biomolecules. 2022 Feb 24;12(3):360. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- zel A K, et al. (2017) The Functions of Metamorphic Metallothioneins in Zinc and Copper Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 18(6). [CrossRef]

- M.George Cherian, A. Jayasurya, Boon-Huat Bay, Metallothioneins in human tumors and potential roles in carcinogenesis, Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis, Volume 533, Issues 1–2, 2003, Pages 201-209, ISSN 0027-5107. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0027510703002173). [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S. Molecular functions of metallothionein and its role in hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol 5, 41 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Roshani, D.; Gao, B.; Li, P.; Shang, N. Metallothionein: A Comprehensive Review of Its Classification, Structure, Biological Functions, and Applications. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 825. [CrossRef]

- G O, D E, et al. (1994) Decreased natural killer (NK) cell activity in zinc-deficient rats. Gen Pharmacol 25(7). [CrossRef]

- H X, F Z, et al. (1998) Effect of zinc on the cellular immunity and NK cell activity in acute heat exposed rats. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 27(5).

- Si, M., Lang, J. The roles of metallothioneins in carcinogenesis. J Hematol Oncol 11, 107 (2018). [CrossRef]

- ndreia O. Latorre, Beatriz D. Caniceiro, Heidge Fukumasu, Dale R. Gardner, Fabricio M. Lopes, Harry L. Wysochi, Tereza C. da Silva, Mitsue Haraguchi, Fabiana F. Bressan, Silvana L. Górniak, Ptaquiloside reduces NK cell activities by enhancing metallothionein expression, which is prevented by selenium, Toxicology, Volume 304, 2013, Pages 100-108, ISSN 0300-483X. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0300483X12004295). [CrossRef]

- Li K, Zhang Z, Mei Y, Yang Q, Qiao S, Ni C, Yao Y, Li X, Li M, Wei D, Fu W, Guo X, Huang X, Yang H. Metallothionein-1G suppresses pancreatic cancer cell stemness by limiting activin A secretion via NF-κB inhibition. Theranostics. 2021 Jan 1;11(7):3196-3212. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ohshio, G., Imamura, T., Okada, N. et al. Immunohistochemical study of metallothionein in pancreatic carcinomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 122, 351–355 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Marreiro DD, Cruz KJ, Morais JB, Beserra JB, Severo JS, de Oliveira AR. Zinc and Oxidative Stress: Current Mechanisms. Antioxidants (Basel). 2017 Mar 29;6(2):24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee SR. Critical Role of Zinc as Either an Antioxidant or a Prooxidant in Cellular Systems. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018 Mar 20;2018:9156285. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nimmanon T, Ziliotto S, Morris S, Flanagan L, Taylor KM. Phosphorylation of zinc channel ZIP7 drives MAPK, PI3K and mTOR growth and proliferation signalling. Metallomics. 2017 May 24;9(5):471-481. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruiman Geng, Nengwen Ke, Ziyao Wang, Yu Mou, Bin Xiang, Zhengkun Zhang, Xuxu Ji, Jiaqiong Zou, Dingxue Wang, Zhaoru Yin, Xubao Liu, Fang Xie, Yanan Zhao, Dan Chen, Jingying Dong, Wenbing Wu, Lihong Chen, Huawei Cai, Ji Liu, Copper deprivation enhances the chemosensitivity of pancreatic cancer to rapamycin by mTORC1/2 inhibition, Chemico-Biological Interactions,Volume 382, 2023, 110546, ISSN 0009-2797. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0009279723002132). [CrossRef]

- Niture S, Gadi S, Lin M, Qi Q, Niture SS, Moore JT, Bodnar W, Fernando RA, Levine KE, Kumar D. Cadmium modulates steatosis, fibrosis, and oncogenic signaling in liver cancer cells by activating notch and AKT/mTOR pathways. Environ Toxicol. 2023 Mar;38(4):783-797. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li K, Zhang Z, Mei Y, Yang Q, Qiao S, Ni C, Yao Y, Li X, Li M, Wei D, Fu W, Guo X, Huang X, Yang H. Metallothionein-1G suppresses pancreatic cancer cell stemness by limiting activin A secretion via NF-κB inhibition. Theranostics. 2021 Jan 1;11(7):3196-3212. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- TAKISHITA, CHIE and NAGAKAWA, YUICHI and OSAKABE, HIROAKI and NAKAGAWA, NOBUHIKO and MITSUKA, YUSUKE and MAZAKI, JUNICHI and IWASAKI, KENICHI and ISHIZAKI, TETSUO and KOZONO, SHINGO, Significance of Zinc Replacement Therapy After Pancreaticoduodenectomy, volume 42, 5833-5837, 2022. https://ar.iiarjournals.org/content/42/12/5833}, Anticancer Research. [CrossRef]

- Iseki M, Mizuma M, Shimura M, Kokumai T, Sato H, Kusaka A, Aoki S, Inoue K, Nakayama S, Douchi D, Miura T, Maeda S, Ishida M, Nakagawa K, Kamei T, Unno M. Preoperative Chemotherapy With Gemcitabine for Pancreatic Cancer Causes Zinc Deficiency. Pancreas. 2025 Feb 1;54(2):e75-e81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiki Y, Ikezawa K, Watsuji K, Urabe M, Kai Y, Takada R, Yamai T, Mukai K, Nakabori T, Uehara H, Ishibashi M, Ohkawa K. Zinc supplementation for dysgeusia in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2024 Aug;29(8):1173-1181. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnarsdottir I, Dahl L. Iodine intake in human nutrition: a systematic literature review. Food Nutr Res. 2012;56. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- M W, and Boral A KZ, et al. (2022) The Impact of Iodine Concentration Disorders on Health and Cancer. Nutrients 14(11). [CrossRef]

- Winder M, Kosztyła Z, Boral A, Kocełak P, Chudek J. The Impact of Iodine Concentration Disorders on Health and Cancer. Nutrients. 2022 May 26;14(11):2209. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kawai, T., Akira, S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat Immunol 7, 131–137 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Xiaoyi Chen, Liegang Liu, Ping Yao, Dong Yu, Liping Hao, Xiufa Sun. Effect of excessive iodine on immune function of lymphocytes and intervention with selenium. Current Medical Science, 2007, 27(18): 422‒425 . [CrossRef]

- Xie S, Wu Z, Zhou L, Liang Y, Wang X, Niu L, Xu K, Chen J, Zhang M. Iodine-125 seed implantation and allogenic natural killer cell immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: a case report. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:7345-7352. [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, A.E.; Verzia, A.; Stanciu, M.M.; Zamfirescu, A.; Gheorghe, D.C. Analysis of the Correlation between the Radioactive Iodine Activity and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 1899. [CrossRef]

- Karbownik-Lewińska M, Stępniak J, Iwan P, Lewiński A. Iodine as a potential endocrine disruptor-a role of oxidative stress. Endocrine. 2022 Nov;78(2):219-240. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fuxiong Lu,Reactive oxygen species in cancer, too much or too little?, Medical Hypotheses,mVolume 69, Issue 6, 2007, Pages 1293-1298, ISSN 0306-9877.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306987707002514). [CrossRef]

- Siyu Liu, Peisen Ding, Xiaomeng Yu et al. Excess iodine promotes papillary thyroid carcinoma through the AKT/mTOR pathway, 19 November 2024, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square [. [CrossRef]

- J. Craps, V. Joris, B. De Jongh, P. Sonveaux, S. Horman, B. Lengelé, L. Bertrand, M.-C. Many, I. M. Colin, A.-C. Gérard, Involvement of mTOR and Regulation by AMPK in Early Iodine Deficiency-Induced Thyroid Microvascular Activation, Endocrinology, Volume 157, Issue 6, 1 June 2016, Pages 2545–2559. [CrossRef]

- Song, Yinghuia,b; Qi, Yuchenc; Yu, Zhangtaoa; Zhang, Zhihuaa; Li, Yuhanga; Huang, Junkaia; Liu, Sulaia,b,*. Iodine-125 seed implantation combined chemotherapy for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma with primary colon cancer: A case report. Medicine 101(36):p e30349, September 09, 2022. |. [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, S., Fuld, M. K., Laheru, D., Huang, P., & Fishman, E. K. (2018). Assessment of iodine uptake by pancreatic cancer following chemotherapy using dual-energy CT. Abdominal Radiology, 43(2), 445-456. [CrossRef]

- Yao H, ZhuGe Y, Jin S, Chen S, Zhang H, Zhang D, Chen Z. The efficacy of coaxial percutaneous iodine-125 seed implantation combined with arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Radiat Biol. 2024;100(7):1041-1050. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun Y, Wang Z, Gong P, Yao W, Ba Q, Wang H. Review on the health-promoting effect of adequate selenium status. Front Nutr. 2023 Mar 16;10:1136458. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- SP S, CS W (2017) Selenoproteins in Tumorigenesis and Cancer Progression. Adv Cancer Res . [CrossRef]

- RJ L, GM J, et al. (2018) The Interaction of Selenium with Chemotherapy and Radiation on Normal and Malignant Human Mononuclear Blood Cells. Int J Mol Sci 19(10). [CrossRef]

- Yu Yang and Ying Liu and Qingxia Yang and Ting Liu, The Application of Selenium Nanoparticles in Immunotherapy,2024, Nano Biomedicine and Engineering, volume 16,3, 345-356; https://www.sciopen.com/article/10.26599/NBE.2024.9290100},.

- Gao S, Li T, Guo Y, Sun C, Xianyu B, Xu H. Selenium-Containing Nanoparticles Combine the NK Cells Mediated Immunotherapy with Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy. Adv Mater. 2020 Mar;32(12):e1907568. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Razaghi, Mansour Poorebrahim, Dhifaf Sarhan, Mikael Björnstedt, Selenium stimulates the antitumour immunity: Insights to future research, European Journal of Cancer, Volume 155, 2021, Pages 256-267, ISSN 0959-8049. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959804921004627). [CrossRef]

- Murugan, D.; Murugesan, V.; Panchapakesan, B.; Rangasamy, L. Nanoparticle Enhancement of Natural Killer (NK) Cell-Based Immunotherapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 5438. [CrossRef]

- Wallenberg M, Misra S, Wasik AM, Marzano C, Björnstedt M, Gandin V, Fernandes AP. Selenium induces a multi-targeted cell death process in addition to ROS formation. J Cell Mol Med. 2014 Apr;18(4):671-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parvin GhasemiAtefeh MaddahAlireza SalehzadehNasrin ZiamajidiAshkan Kalantary-CharvadehRoghayeh AbbasalipourkabirMaryam Salehzadehet al.Study of Oxidative Stress and Apoptotic Genes in SW480 Cell Lines Treated with Selenium Nanoparticles.J Rep Pharm Sci.13(1):e151064. [CrossRef]

- Hwang JT, Kim YM, Surh YJ, Baik HW, Lee SK, Ha J, Park OJ. Selenium regulates cyclooxygenase-2 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathways by activating AMP-activated protein kinase in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006 Oct 15;66(20):10057-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu Y, Pu Q, Zhang Q, et al. Selenium-binding protein 1 inhibits malignant progression and induces apoptosis via distinct mechanisms in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2023; 12: 17149-17170. [CrossRef]

- Roberta Noè, Noemi Inglese, Patrizia Romani, Thauan Serafini, Carlotta Paoli, Beatrice Calciolari, Marco Fantuz, Agata Zamborlin, Nicoletta C. Surdo, Vittoria Spada, Martina Spacci, Sara Volta, Maria Laura Ermini, Giulietta Di Benedetto, Valentina Frusca, Claudio Santi, Konstantinos Lefkimmiatis, Sirio Dupont, Valerio Voliani, Luca Sancineto, Alessandro Carrer, Organic Selenium induces ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer cells, Redox Biology, Volume 68, 2023, 102962,ISSN 2213-2317.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213231723003634). [CrossRef]

- Wooten, D. J., Sinha, I., & Sinha, R. (2022). Selenium Induces Pancreatic Cancer Cell Death Alone and in Combination with Gemcitabine. Biomedicines, 10(1), Article 149. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Shihai & Wang, Yang & Wang, Meiqin & Jiang, Li & Ma, Xue & Huang, Yong & Liu, Ting & Zheng, Lin & Li, Yongjun. (2024). Construction and anti-pancreatic cancer activity of selenium nanoparticles stabilized by Prunella vulgaris polysaccharide. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 278. 134924. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134924.

- Kaya DE, Göktürk F, Batırbek F, Arıkoğlu H. Investigation of the Effects of Juglone-Selenium Treatments on Epithelial-Mesenchimal Transition and Migration in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Med J Bakirkoy. 2023 Sep;19(3):248-255. [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M.D. (2015), Phosphorus and Calcium. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 30: 21-33. [CrossRef]

- S A, O M (2021) Hypophosphatemia in cancer patients. Clin Kidney J 14(11). [CrossRef]

- R.B. B (2019) Vitamin D, cancer, and dysregulated phosphate metabolism. Endocrine 65. URL . [CrossRef]

- Kerr WG, Colucci F. Inositol phospholipid signaling and the biology of natural killer cells. J Innate Immun. 2011;3(3):249-57. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thirumalai A, Elboughdiri N, Harini K, Girigoswami K, Girigoswami A. Phosphorus-carrying cascade molecules: inner architecture to biomedical applications. Turk J Chem. 2023 Jun 23;47(4):667-688. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu HY, Da WM. [Regulation of immunity by sphingosine 1-phosphate and its G protein-coupled receptors--review].

- L. He, J. Zhao, H. Li, B. Xie, L. Xu, G. Huang, T. Liu, Z. Gu, T. Chen, Metabolic Reprogramming of NK Cells by Black Phosphorus Quantum Dots Potentiates Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2202519. [CrossRef]

- Fiore PF, Di Pace AL, Conti LA, Tumino N, Besi F, Scaglione S, Munari E, Moretta L, Vacca P. Different effects of NK cells and NK-derived soluble factors on cell lines derived from primary or metastatic pancreatic cancers. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023 Jun;72(6):1417-1428. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hayes JD, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Tew KD. Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020 Aug 10;38(2):167-197. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McCarty MF, Lerner A, DiNicolantonio JJ, Iloki-Assanga SB. High Intakes of Bioavailable Phosphate May Promote Systemic Oxidative Stress and Vascular Calcification by Boosting Mitochondrial Membrane Potential-Is Good Magnesium Status an Antidote? Cells. 2021 Jul 9;10(7):1744. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Soefje SA, Karnad A, Brenner AJ.. Common toxicities of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors. Target Oncol 2011; 6: 125–129.

- Lee JP, Darlington K, Henson JB, Kothari D, Niedzwiecki D, Farooq A, Liddle RA. Hypophosphatemia as a Predictor of Clinical Outcomes in Acute Pancreatitis: A Retrospective Study. Pancreas. 2024 Jan 1;53(1):e3-e8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng J, Glezerman IG, Sadot E, McNeil A, Zarama C, Gönen M, Creasy J, Pak LM, Balachandran VP, D’Angelica MI, Allen PJ, DeMatteo RP, Kingham PT, Jarnagin WR, Jaimes EA. Hypophosphatemia after Hepatectomy or Pancreatectomy: Role of the Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase. J Am Coll Surg. 2017 Oct;225(4):488-497e2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peiró-Valgañón V, Guardiola-Arévalo A, López Fernández A, Llorente Herrero E, Martín Fernández-Gallardo MT. A multidisciplinary challenge: Therapy with phosphorus-32 for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol (Engl Ed). 2023 Nov-Dec;42(6):403-409. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).