3.1. Grey Forecasting Model

Grey theory, initially proposed by Deng [

16], is designed to analyze systems that have incomplete or limited information. A key advantage of grey models is their ability to generate forecasts using relatively small datasets.

The GM(1,1) model refers to a first-order, single-variable grey model. The procedure for constructing GM(1,1) is outlined as follows:

Let the original data sequence be

where

x(0)(k) stands for the original data sequence in period

k. The following sequence

is defined as

Equation (2) was generated based on the accumulated generating operation (AGO) of Equation (1).

Before building the model, a class ratio must be performed to ensure that the sequence is suitable for modeling. The class ratio

is defined as follows:

If (0,1), then is appropriate for modeling.

After finishing the class ratio test, the GM(1, 1) model is formulated as a first-order differential equation for

as:

where

a and

b are coefficients to be estimated.

Next, we applied the ordinary least squares method to Equation (4) to estimate the coefficients of

a and

b. Once

and

are estimated, we generate predictions by substituting

and

into the following equation:

Finally, the forecasted values of the time series are obtained by applying the inverse accumulated generating operation (IAGO) to convert to

as follows:

3.2. SARIMA

The seasonal model employed in this study belongs to the general class of univariate models originally introduced by Box and Jenkins [

17]. SARIMA has been widely applied across various disciplines and remains a cornerstone in time series forecasting. A fundamental requirement in constructing this model is that the time series must be stationary, meaning its probabilistic properties remain constant over time.

SARIMA extends the ARIMA framework by incorporating seasonal components, making it suitable for time series data exhibiting seasonality. The model is typically expressed as SARIMA(p, d, q)(P, D, Q)s, where

p represents the order of the non-seasonal autoregressive terms,

d denotes the degree of non-seasonal differencing,

q corresponds to the order of the non-seasonal moving average terms,

P, D, and Q represent the seasonal autoregressive, seasonal differencing, and seasonal moving average orders, respectively,

s indicates the length of the seasonal cycle.

The general representation of the SARIMA model can be written as:

where

ψp(B) = (1-ψ1B-ψ2B2-…-ψp Bp),

Φp(Bs) is the seasonal operator of order P,

B is the backshift operator with Bm(Zt)=Zt-m,

s is the season length,

▽d=(1-B) is the non-seasonal operator,

is the seasonal differencing operator,

Zt is the stationary data at time t,

θq(B) = (1-θ1B-θ2B2-…-θqBq),

is the seasonal operators of order Q, and εt is the white noise with zero mean and variance.

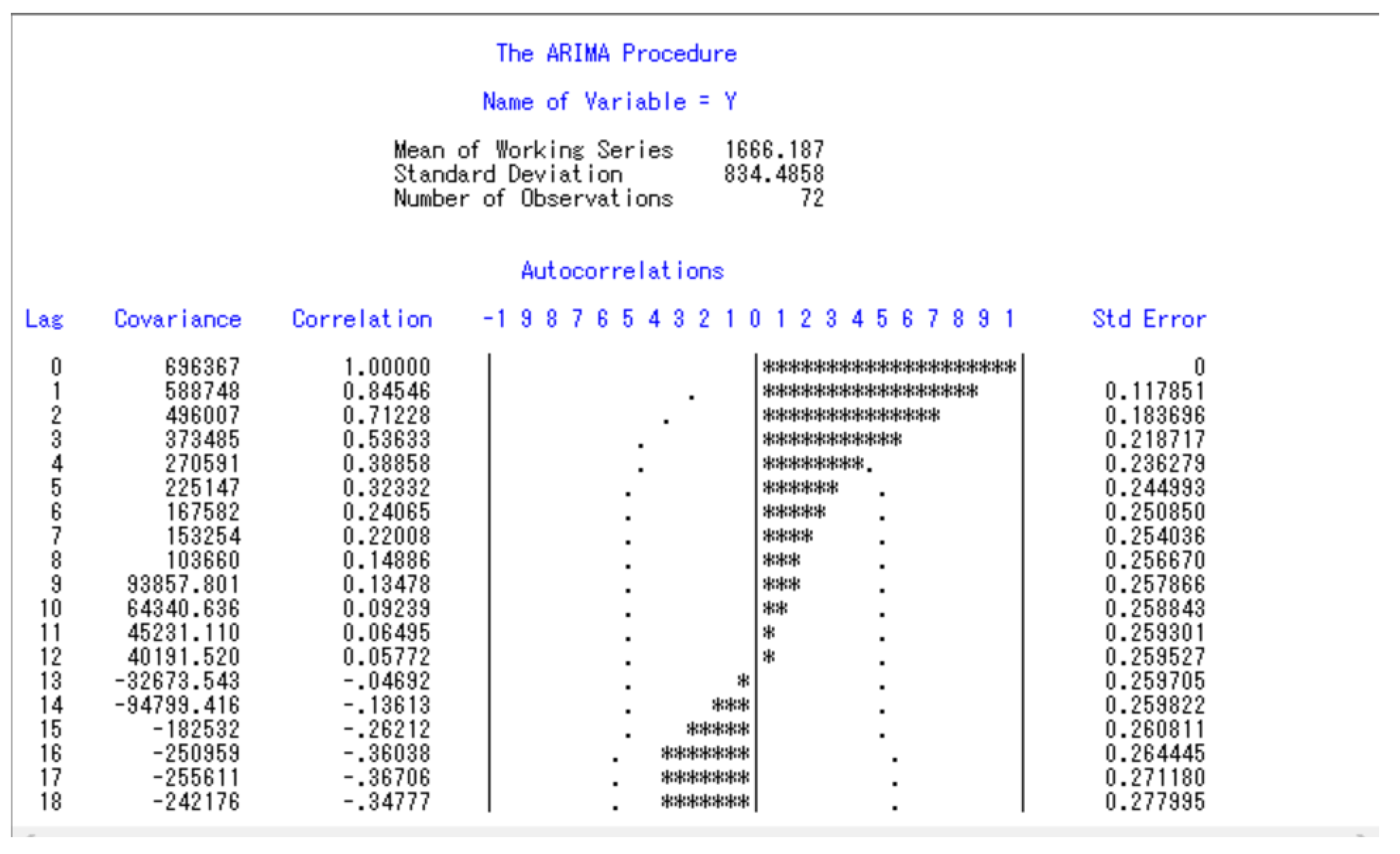

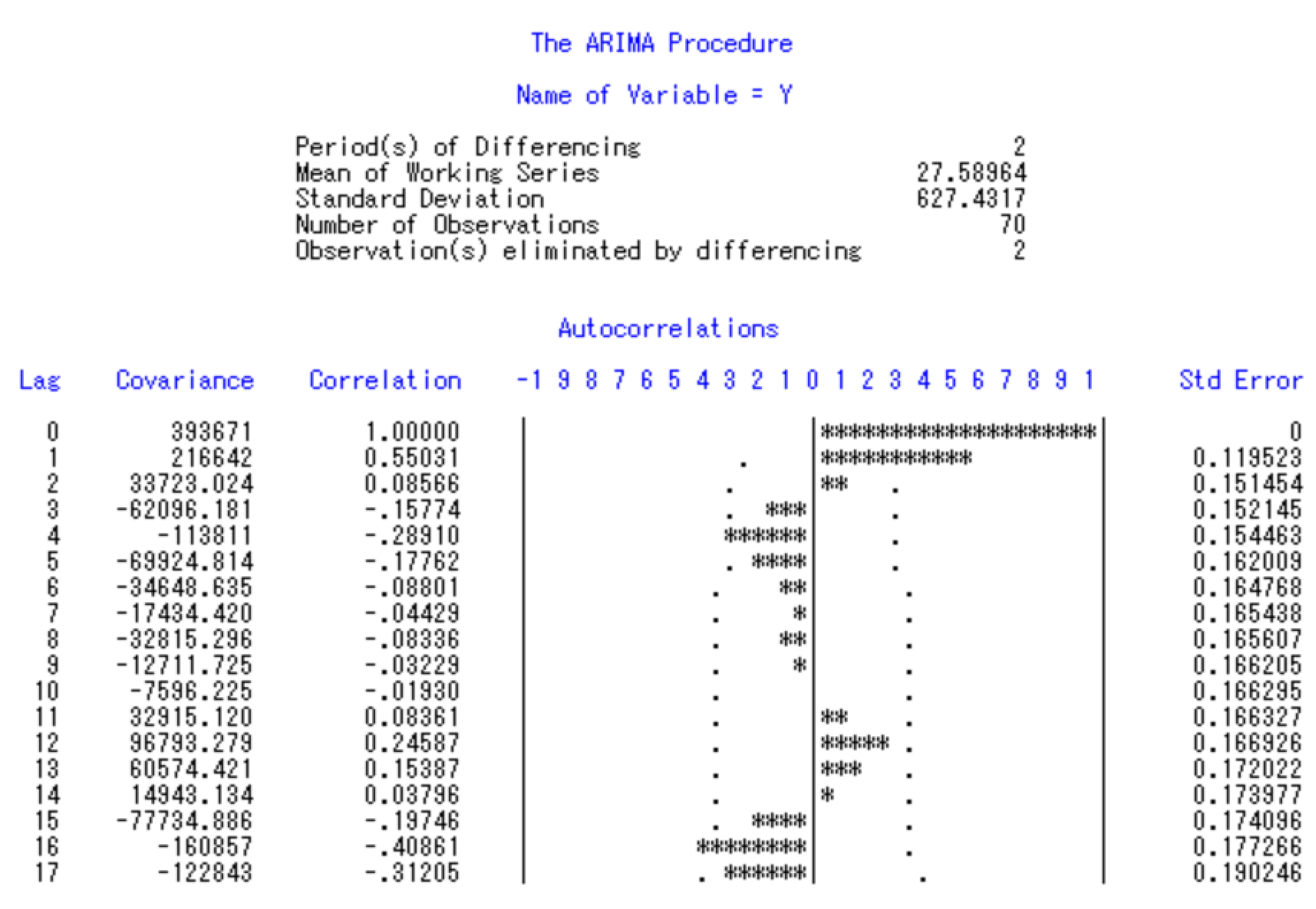

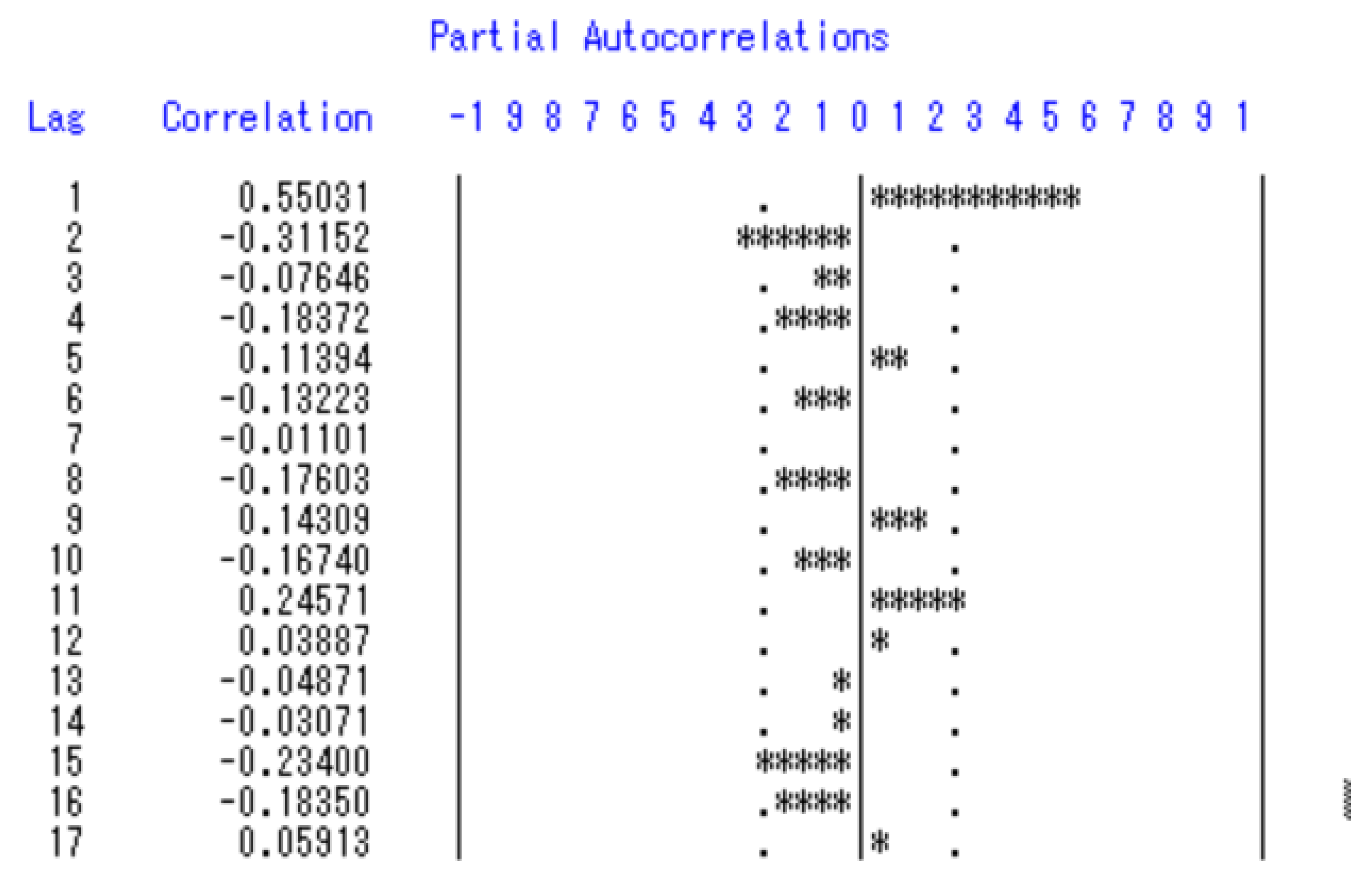

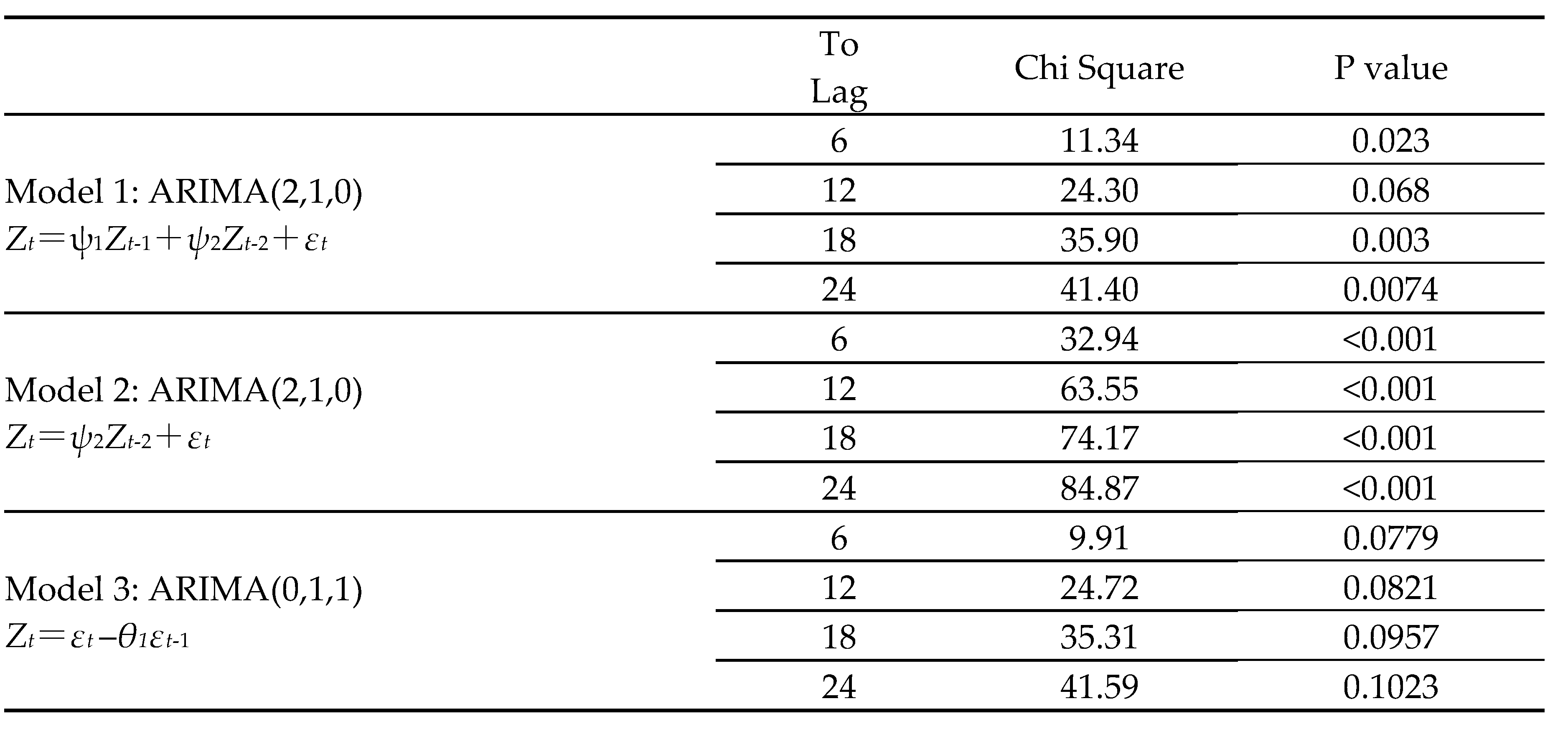

The model-building process involves three main stages: identification, parameter estimation, and diagnostic checking. In the identification phase, the tentative structure of the AR and MA terms (p and q) is determined by analyzing the autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation patterns. Once an initial specification is chosen, parameter estimation is carried out, often using methods such as maximum likelihood or least squares. Finally, diagnostic checking assesses the adequacy of the fitted model by examining residuals to ensure they exhibit the properties of white noise. If the diagnostics confirm model suitability, the SARIMA model is then employed for forecasting.

3.3. The EMD-SVR-GWO Model

3.3.1. EMD Model

Empirical Mode Decomposition is a data-driven technique developed by Norden E. Huang [

18] in the late 1990s for analyzing non-linear and non-stationary time series data. Unlike traditional signal processing methods that rely on predefined basis functions (e.g., Fourier or wavelet transforms), EMD adaptively decomposes a signal into a set of intrinsic mode functions based on the inherent characteristics of the data. This makes EMD particularly useful for a wide range of applications, including signal processing, economics, geophysics, and biomedical engineering.

The EMD process consists of the following steps:

(1) identify Extrema: Detect all local maxima and minima in the signal. These points indicate where the signal changes direction and are used to construct the upper and lower envelopes.

(2) Interpolate: Using the identified extrema, create smooth upper and lower envelopes by interpolating between the maxima and minima, respectively. Common interpolation methods include cubic splines or piecewise linear functions.

(3) Mean Calculation: Compute the mean of the upper and lower envelopes. This mean represents the local trend of the signal.

(4) Sifting Process: Subtract the mean from the original signal to obtain a candidate IMF. This component is called a “proto-IMF.” The sifting process involves repeating the steps of extrema identification, interpolation, and mean calculation on the proto-IMF until it meets the IMF criteria: (i) The number of zero crossings and extrema must either be equal or differ by at most one. (ii) The mean value of the envelopes should be zero at every point.

(5) Residual Calculation: Once a valid IMF is obtained, subtract it from the original signal to get a residual. This residual represents the remaining signal after extracting the first IMF.

(6) Repeat: Apply the EMD process recursively to the residual to extract further IMFs until the residual becomes a monotonic function or has no more than two extrema. The decomposition is complete when the residual is either a constant, a monotonic trend, or contains no further oscillatory modes.

EMD has been applied across various fields due to its ability to handle non-linear and non-stationary data. In signal processing, it facilitates denoising, feature extraction, and fault detection in mechanical and electrical systems. The technique supports the analysis of financial time series, market trends, and economic cycles in economics. Geophysics benefits from EMD through seismic signal analysis, ocean wave modeling, and climate data interpretation. In biomedical engineering, EMD is instrumental in processing physiological signals such as electroencephalograms, electrocardiograms, and speech signals.

The advantages of EMD include its data-driven nature, which eliminates the need for predefined basis functions and makes it versatile for various types of data. Additionally, its adaptability allows it to handle non-linear and non-stationary signals effectively.

In summary, Empirical Mode Decomposition is a powerful and adaptive method for analyzing complex signals. By decomposing signals into intrinsic mode functions, EMD provides a flexible approach for revealing underlying patterns and trends in non-linear and non-stationary data. Its wide range of applications and ability to handle diverse data types make it an essential tool in various scientific and engineering disciplines.

3.3.2. SVR

Support Vector Regression (SVR) is a robust and versatile machine learning algorithm used for regression tasks. Originating from the principles of Support Vector Machines, SVR aims to predict continuous outcomes based on input features. While SVM is widely recognized for its effectiveness in classification problems, SVR extends these capabilities to the realm of regression, making it a valuable tool in various applications, such as financial forecasting, time series prediction, and biological data analysis.

At its core, SVR is designed to find a function that approximates the relationship between input features and a continuous target variable. The primary objective of SVR is to minimize the error of predictions while maintaining a degree of robustness by considering only a subset of the training data, known as support vectors. These support vectors are the critical elements of the training set that define the model.

SVR operates by introducing a margin of tolerance (epsilon), within which errors are ignored. This margin is referred to as the epsilon-insensitive zone. The essence of SVR is to ensure that the predictions lie within this margin for as many data points as possible, thereby balancing the complexity of the model with its predictive accuracy.

The SVR problem can be formulated as follows:

Given a training dataset , where xi represents the input features and yi the target variable, the goal is to find a function f(x) that deviates from the actual targets yi by at most ϵ. The function f(x) is typically expressed as:

f(x)=⟨w,x⟩+b where w is the weight vector and b is the bias term. The optimization problem is defined as (Vapnik [

19]):

subject to

Here, slack variables that allow for deviations greater than ϵ, and C is a regularization parameter that determines the trade-off between the flatness of f(x) and the amount by which deviations larger than ϵ are tolerated.

One of the strengths of SVR, inherited from SVM, is the ability to handle non-linear relationships through the kernel trick. By mapping the input features into a higher-dimensional space using a kernel function, SVR can fit complex, non-linear functions. Commonly used kernels include the linear, polynomial, and radial basis function (RBF) kernels. In this research, the radial basis function is adopted.

3.3.3. GWO

The Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) is a metaheuristic algorithm inspired by the leadership structure and cooperative hunting strategies of grey wolves. These animals typically live in packs of 5–12 members and exhibit a well-defined social hierarchy. This hierarchy is the foundation of GWO’s design.

- (1)

Social Hierarchy of Grey Wolves

In a grey wolf pack, leadership and responsibilities are distributed among four main roles:

Alpha (α): The alpha wolves, usually a dominant male and female, lead the pack by making critical decisions regarding hunting, resting, and movement. Interestingly, alpha wolves are not always the strongest physically; their primary role is managing and maintaining order. While their decisions are generally followed by the rest of the pack, occasional democratic behaviors are observed where alpha wolves heed suggestions from others. Submission to alpha decisions is typically shown by the other wolves lowering their tails.

Beta (β): Positioned just below alpha wolves, the beta wolves act as advisors and enforcers. They help implement alpha’s decisions, maintain discipline, and provide feedback. Betas are also the likely successors if an alpha dies or becomes incapable of leading.

Omega (ω): At the lowest rank, omega wolves serve as scapegoats and stress relievers for the group, which prevents internal conflicts. Although they eat last and hold minimal authority, omegas are essential for pack stability. Occasionally, they also serve as caretakers for pups.

Delta (δ): Wolves that do not belong to the above categories are called subordinates (delta wolves). They serve various roles such as scouts (patrolling territory), sentinels (guarding), hunters (assisting in hunting), and caregivers for weak or injured members.

Group Hunting Behavior

Grey wolves hunt cooperatively, and their hunting process can be divided into three stages:

- i.

Tracking and approaching the prey.

- ii.

Pursuing, encircling, and harassing until the prey is immobilized.

- iii.

Attacking once the prey is exhausted.

GWO incorporates these two behavioral aspects—social hierarchy and hunting strategy—into its optimization mechanism (Muro et al. [

20]).

- (2)

Mathematical Modeling in GWO

The algorithm assigns the best candidate solution as alpha (α), the second-best as beta (β), and the third-best as delta (δ). All other solutions are considered omega (ω). These three top solutions guide the remaining wolves during the optimization process.

- 2.

Encircling Prey

Grey wolves encircle their prey during hunting, which is modeled as follows:

where:

t = current iteration,

= position vector of the wolf,

= position vector of the prey,

and = coefficient vectors,

= vector used to specify a new position of the grey wolf.

The coefficient vectors are defined as (Mirjalili et al., [

21]):

Here:

a decreases linearly from 2 to 0 over iterations,

r1 and r2 are random vectors in [0, 1].

- 3.

Hunting (Exploitation Phase)

To simulate hunting, GWO assumes α, β, and δ wolves have the most accurate information about the prey’s position. The algorithm stores these three best solutions and updates others accordingly:

This mechanism ensures wolves move toward the prey’s estimated location.

- 4.

Attacking the Prey

The attack occurs as decreases from 2 to 0. When lies within [-1, 1], wolves close in on the prey, leading to exploitation and convergence.

- 5.

Searching for Prey (Exploration)

During exploration, wolves diverge to search for prey. This is controlled by ; if ∣A∣> 1, wolves move away from the prey to explore new areas. Another component, , introduces randomness by adjusting the emphasis on the prey’s position (C > 1 amplifies attraction; C < 1 reduces it). Unlike , does not decrease linearly, which helps maintain global search capability and prevents premature convergence. Overall, these mechanisms allow GWO to balance exploration and exploitation, reducing the risk of getting trapped in local optima.

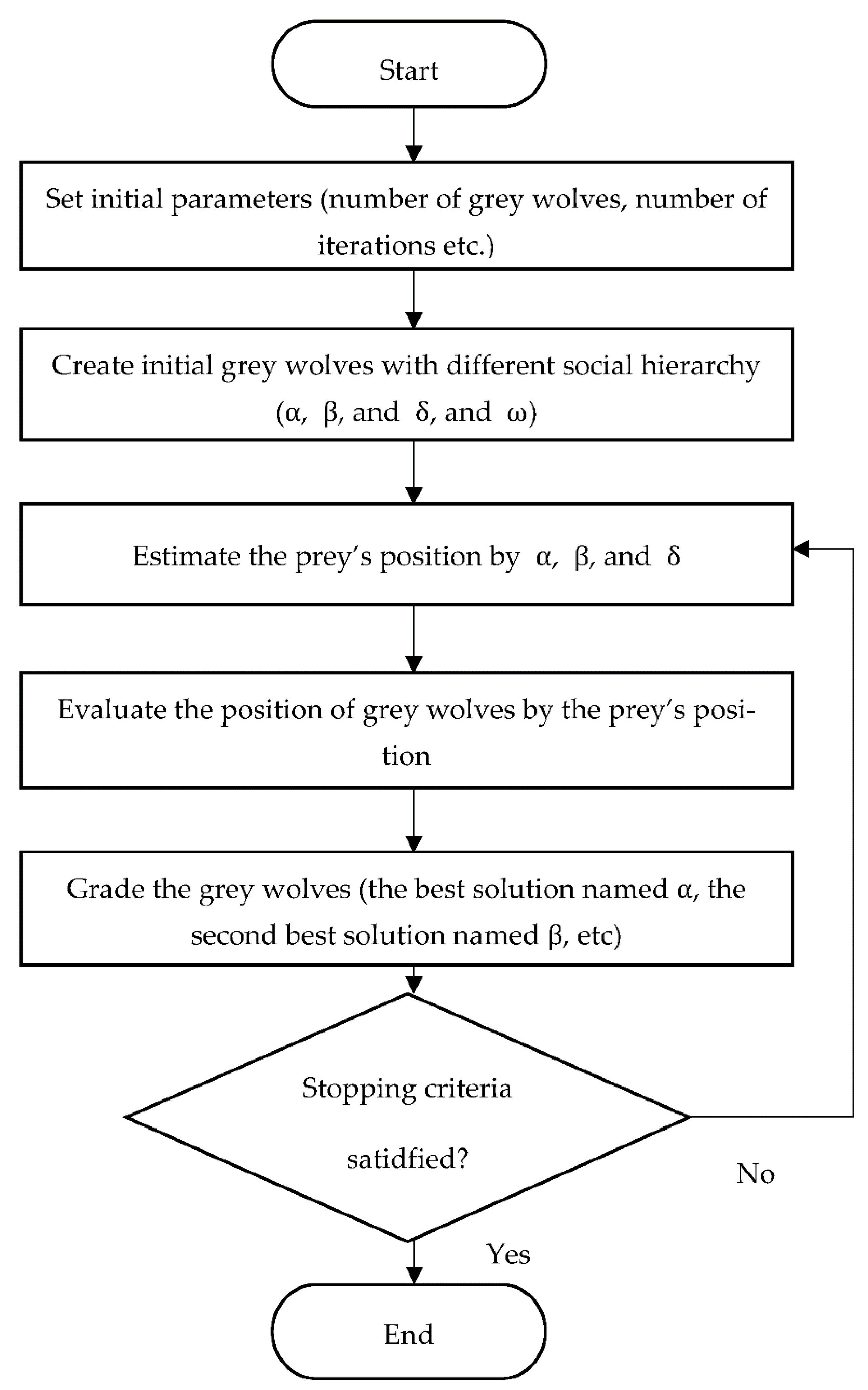

Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the GWO algorithm.

3.3.4. Model Construction of EMD-SVR-GWO

The EMD-SVR-GWO model is a hybrid forecasting framework designed to improve prediction accuracy by leveraging the strengths of three advanced techniques: Empirical Mode Decomposition, Support Vector Regression, and the Grey Wolf Optimizer. This model is particularly effective for complex, nonlinear, and non-stationary time series data, such as financial indices, economic indicators, or environmental data. The construction of the EMD-SVR-GWO model involves three primary stages:

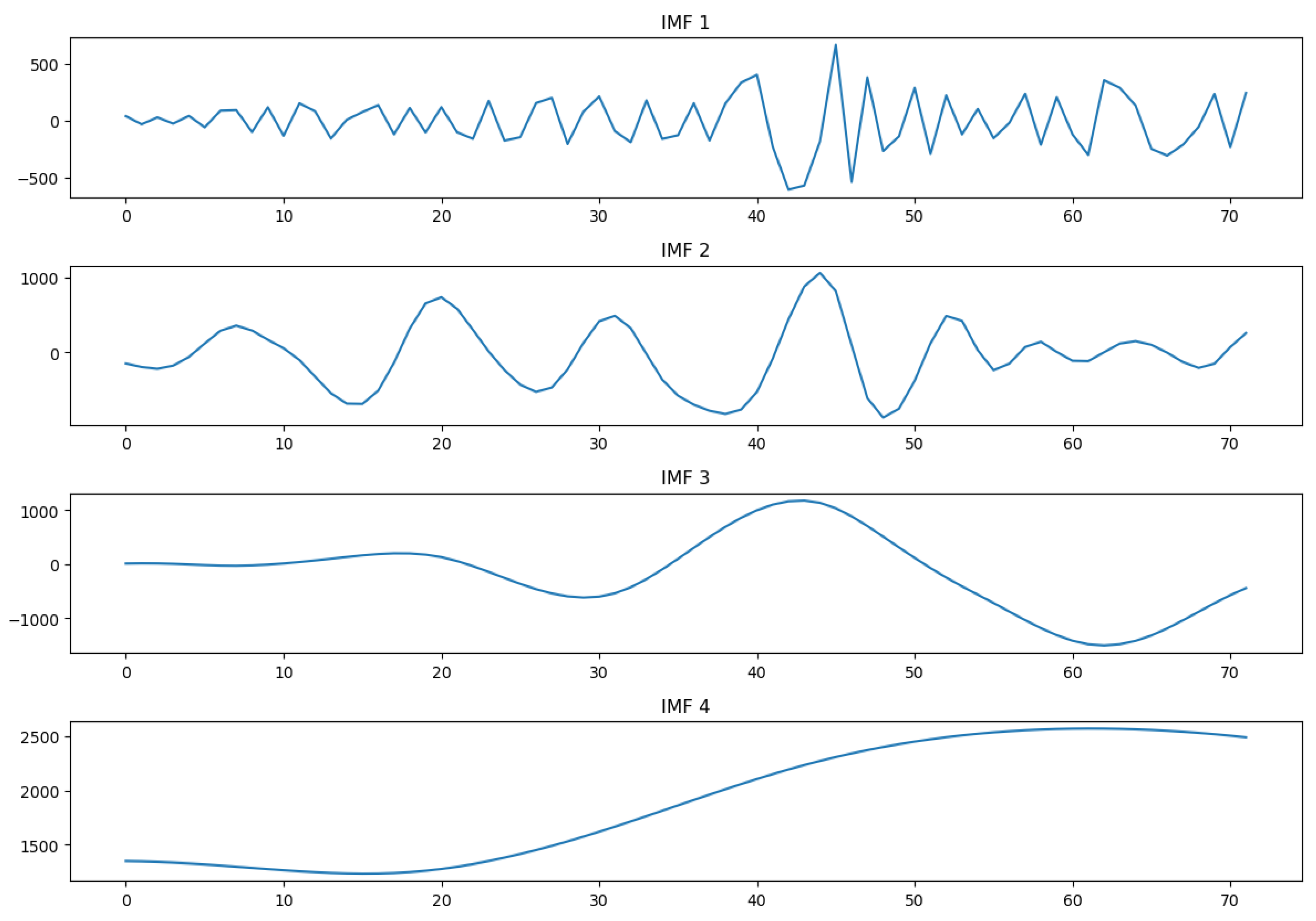

1. Empirical Mode Decomposition

EMD is a data-driven decomposition technique that breaks down the original data into a set of components called Intrinsic Mode Functions and a residual trend. Each IMF represents oscillatory modes embedded within the data, capturing different frequency characteristics, while the residual captures the long-term trend.

The decomposition enables the isolation of distinct patterns (high-frequency fluctuations, medium-term cycles, and long-term trends), which are modeled separately in the next stage.

2. Support Vector Regression

After decomposition, each IMF and the residual are treated as independent sub-series. Support Vector Regression is applied to predict each component individually. SVR is chosen for its robustness in handling nonlinear relationships and its strong generalization capabilities.

Each IMF captures different dynamics of the original time series, and SVR models are trained separately to forecast these dynamics effectively.

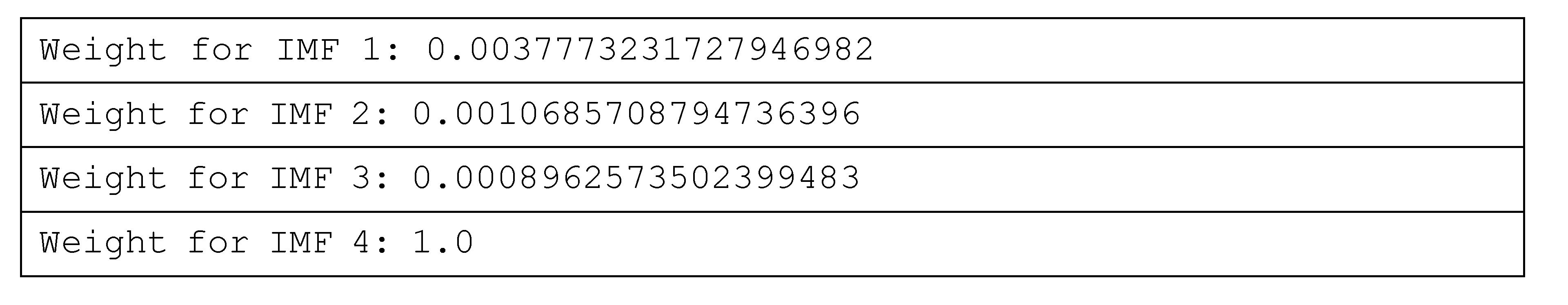

3. Grey Wolf Optimizer

The final stage involves the reconstruction of the original time series by combining the predicted IMFs and residual. To achieve the most accurate forecast, the Grey Wolf Optimizer is employed to determine the optimal combination of these forecasts. GWO is a metaheuristic optimization algorithm inspired by the hunting behavior and social hierarchy of grey wolves in nature.

The EMD-SVR-GWO hybrid model offers a powerful and flexible framework for time series forecasting. EMD enhances the model by decomposing complex data into simpler components, SVR captures nonlinear relationships within each component, and GWO optimizes the final forecast by adjusting the weights for the most accurate reconstruction. This approach is highly effective for datasets with mixed trends, seasonality, and noise, providing superior forecasting performance compared to traditional single-model methods.