Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

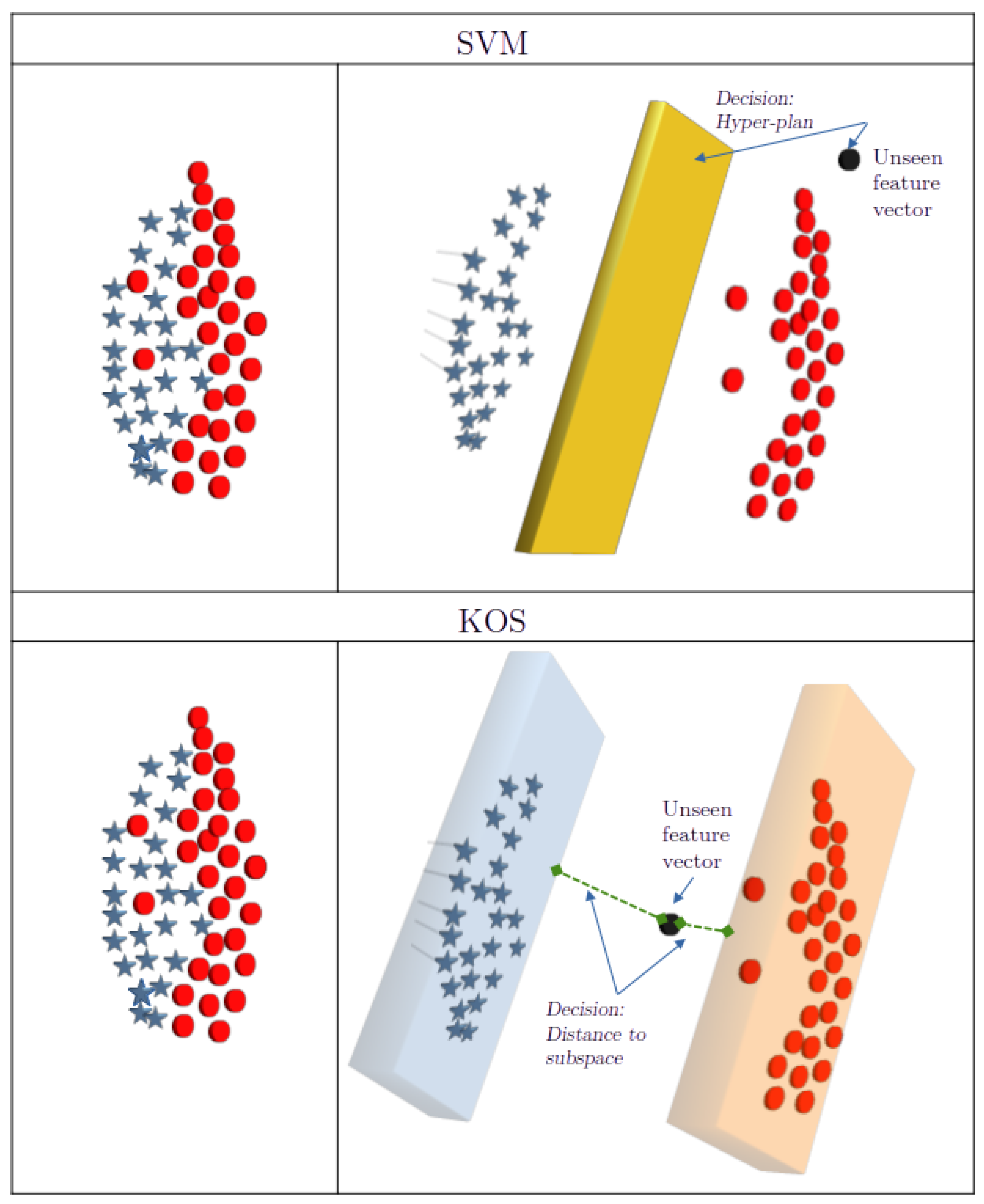

- As an optimization problem, SVM may fail, particularly in high-dimension, even though the cost function is convex (quadratic).

- Extending SVM to multiclass classification is not straightforward and becomes computationally expensive in high dimensions or when the number of classes is large. For instance, a common approach combining one-against-one and one-against-all strategies requires computing a total of separating hyperplanes (i.e., solving n optimization problems), where n is the number of classes.

- Imbalanced classes poses another challenge. A popular approach to addressing this involves adding synthetic attributes to underrepresented classes. While effective, the process is not straightforward, and can alter the structure of the original class data.

- In dynamic classification, where classes may be added or removed, all separating hyperplanes must be recalculated, which can be prohibitively expensive for real-time applications.

2. KOS: Kernel-Based Optimal Subspaces Method

2.1. Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD): Overview

2.1.1. POD Basis System

- (1)

- : if , let M be the correlation matrix where is any inner product. Let V the matrix of eigenvectors of M, then the basis functions , called modes, are given by:where are the components of the eigenvector of M

- (2)

- : if , the POD basis is defined by the eigenvectors of the matrix

This is an example of a quote.

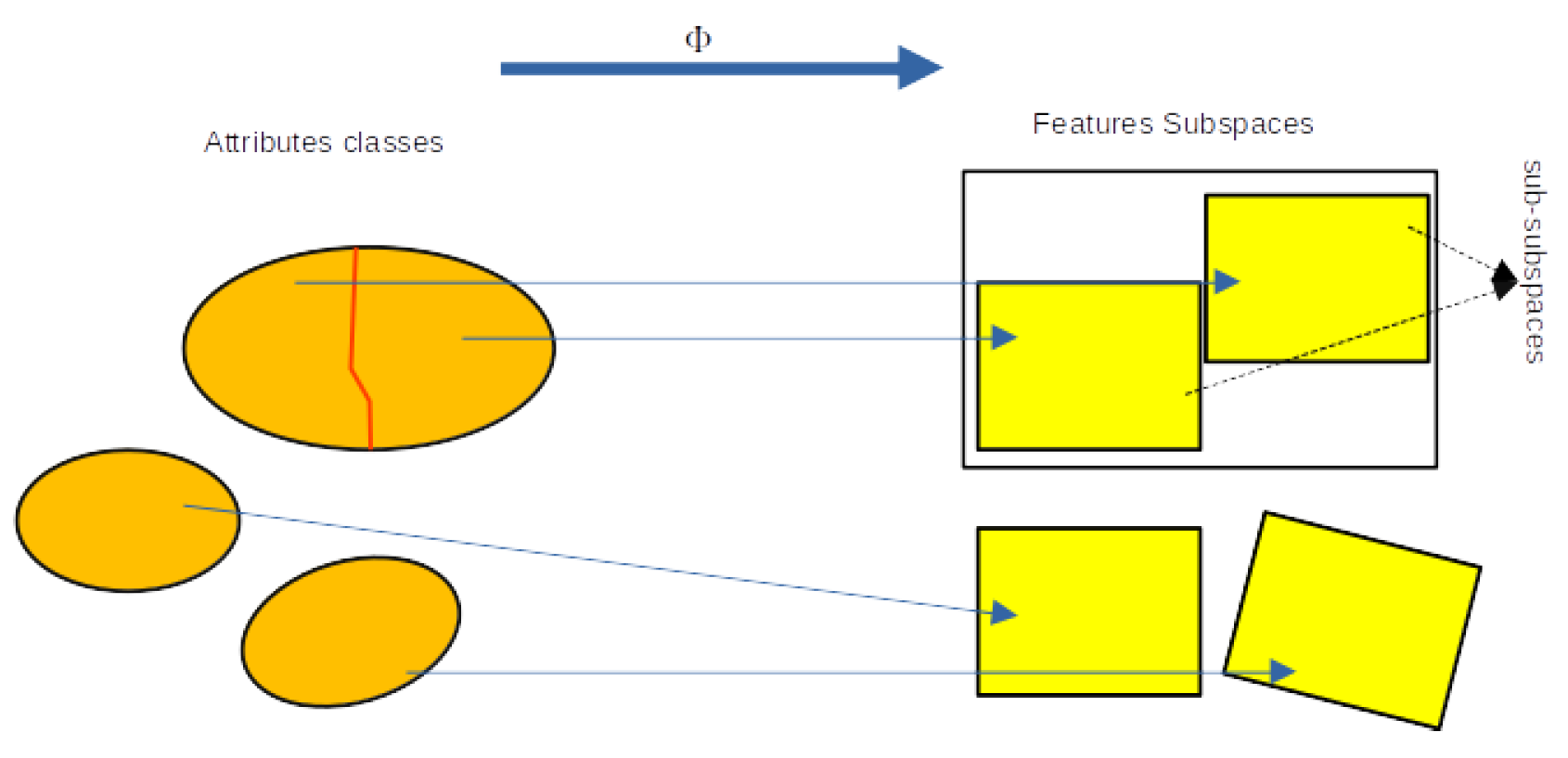

2.2. KOS: Global Description and Some Theoretical Aspects

2.3. POD Feature Subspaces

- 1.

-

None-Centered data formulation: In this case, the data in the feature space are used without centering. Let be the mapped data points of a selected class of size N. First, we construct the correlation matrix:where denotes the kernel function evaluated at and . As seen, the POD correlation matrix is equivalent to the kernel matrix derived from the mapping.The normalized POD modes are then given by:where is the eigenvector of the kernel matrix M and the associated eigenvalue.

- 2.

-

Centered data formulation: In this case, the feature vectors are centered. Let be the mean vector, and be the centered data. The correlation matrix is then given by:Each of the inner products can be expressed in terms of the kernel function:Substituting back into the expression for , the centered correlation matrix becomes:As in the non-centered case, the correlation matrix can be entirely expressed using the kernel matrix.The normalized POD modes for centered data are then given by:where is the eigenvector of the correlation matrix M defined by 14 and the associated eigenvalue

2.4. Optimality of the POD Feature Subspaces

-

Geometrical Optimality of POD Feature Spaces:As shown in [19], if is the POD basis matrix constructed to represent the columns of a matrix , and is any other basis of a same size constructed for the same purpose, then the following inequality holds:where is the Frobenius norm, defined by:This result demonstrates the geometric optimality of the POD basis: among all possible orthonormal bases of the same dimension, the POD basis provides the best approximation (in the least-squares sense) of the original data matrix A. Therefore, the POD basis vectors are the closest possible representatives of the original feature vectors, ensuring maximum fidelity in capturing the data structure.

-

Algebraic Optimality of POD Feature Spaces:Lemma: The POD subspace is algebraically optimal; it is the smallest subspace containing the mapped data.Proof: The proof is straightforward. To show that the POD subspace is the smallest subspace containing the mapped (feature) data, it is sufficient to show that any subspace containing the feature data must also contain the POD subspace.Let F be a subspace that contains the given feature data. To prove that F also contains the POD subspace, it suffices to show that F ontains the POD modes (i.e., the basis of the POD subspace). Since the POD modes are linear combinations of the feature data, and F s a subspace (i.e., closed under linear combinations), the modes necessarily lie in F. Hence, the POD subspace is contained in a ny subspace that contains the mapped data, proving its algebraic optimality.

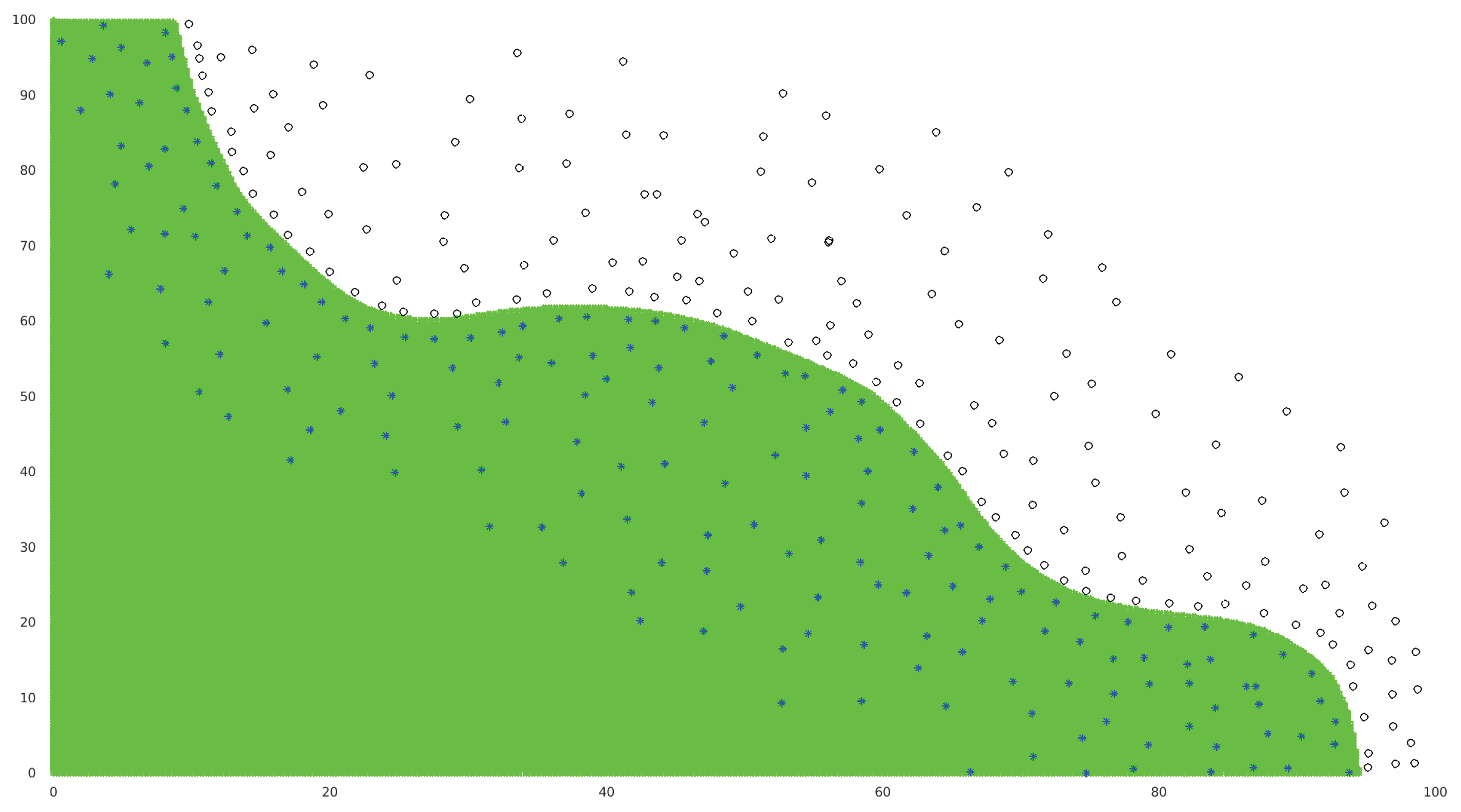

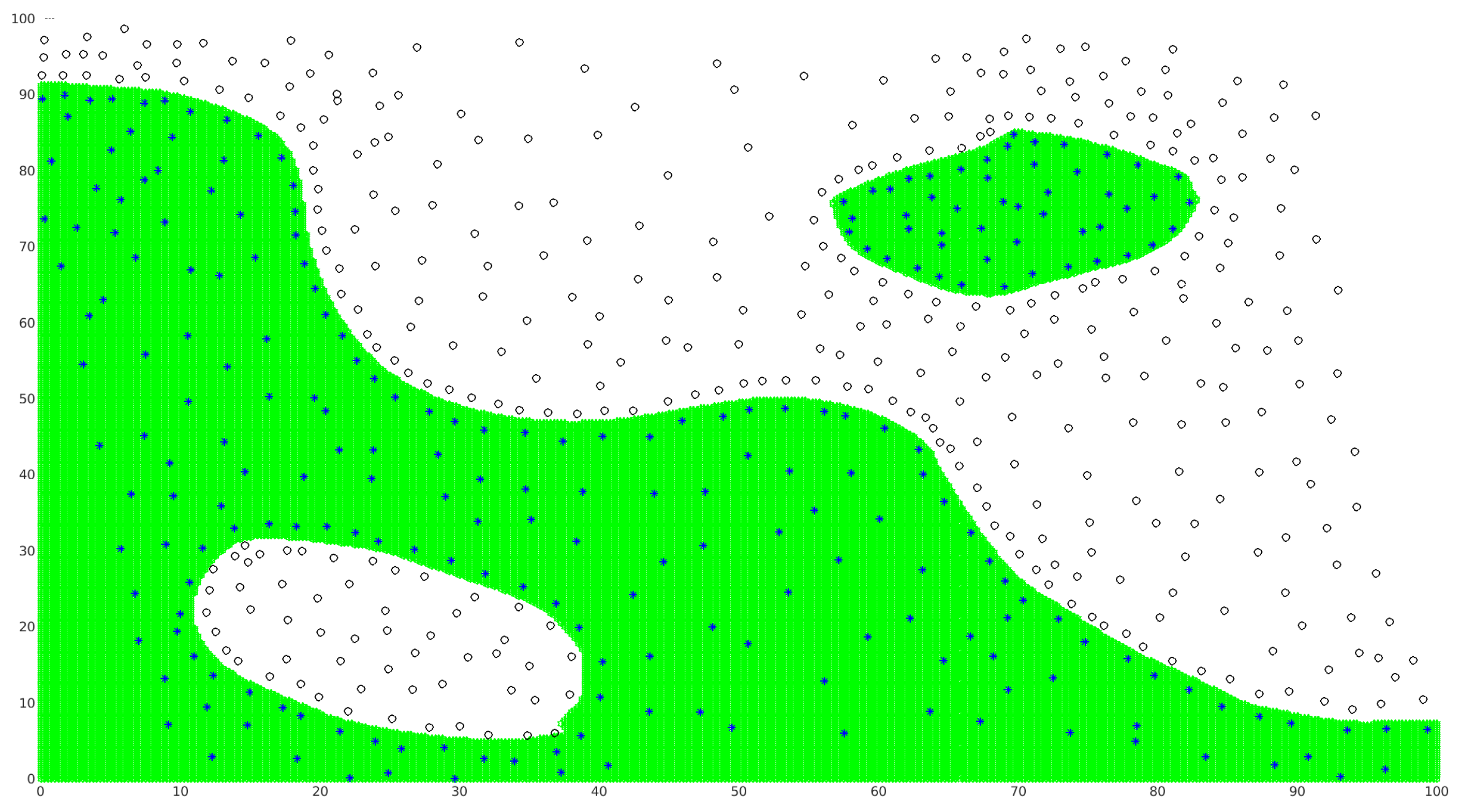

2.5. Decision Criterion

- 1.

-

None-Centered data formulation: The coordinates are given by the projection of the element on the POD modeswithThenUsing the Pythagoras rule, the distance of to the POD subspace F, is given byWith

- 2.

-

Centered data formulation: For the centered case, and are replaced by and respectively. That is,withThenSubstituting we obtain

2.6. Imbalanced Classes

2.7. RBF Parameter Learning

2.8. Summary of the Algorithm

- 1.

- Check whether the classes are imbalanced. If so, split the larger classes into smaller subclasses according to procedure described in Section 2.6.

- 2.

- Select a Mercer kernel K, then compute the kernel matrices for each feature class (of feature subclasses if applicable).

- 3.

- 4.

- Compute the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of each matrix .

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- Decision: Assign to the class corresponding to the minimum computed distance.

3. Results: Validation and Discussion

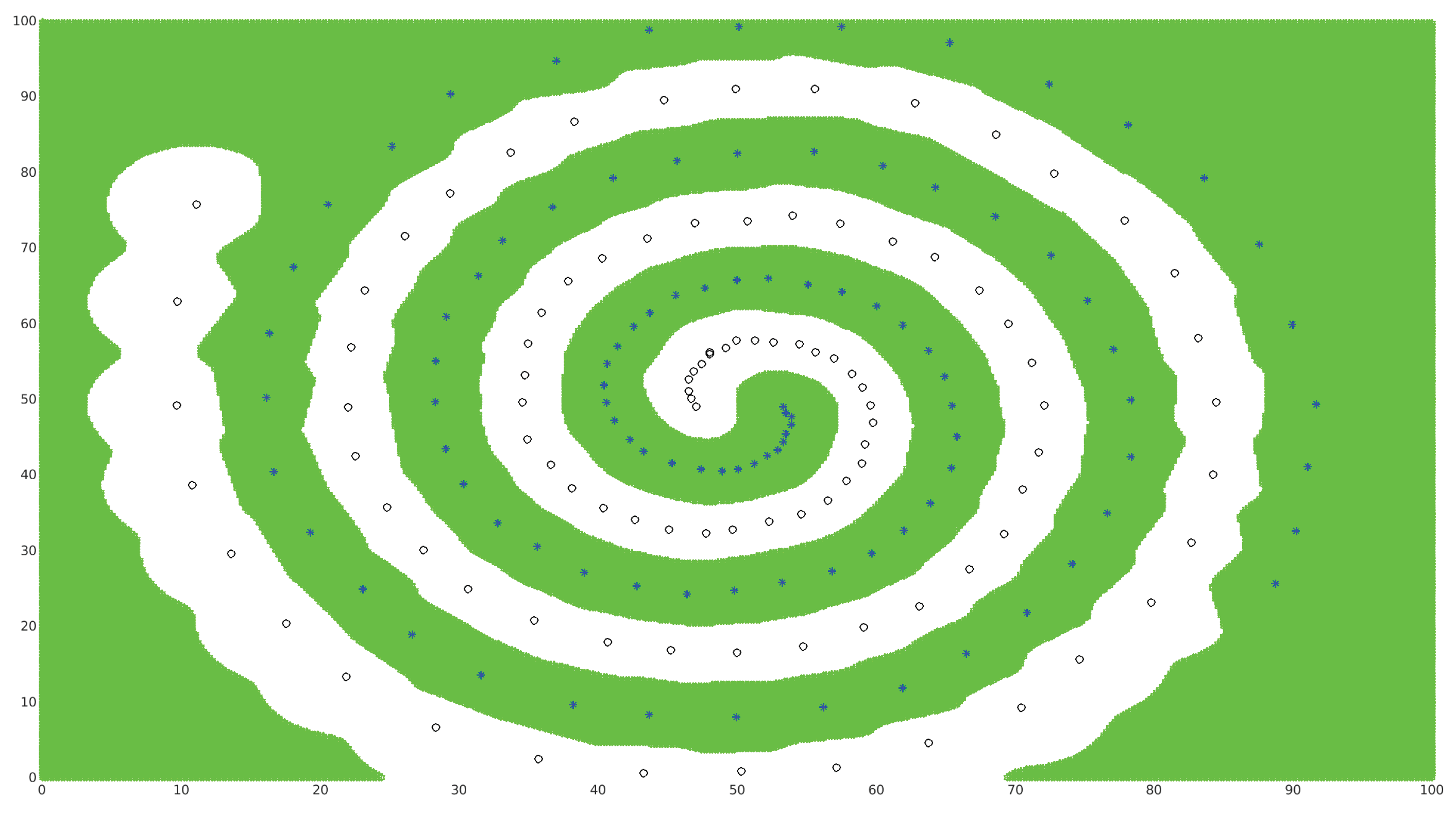

3.1. 2D Test Cases

3.2. Higher-Dimension Test Cases

3.3. KOS main Advantages Compared to SVM

- 1.

- 2.

- Robustness: KOS algorithm is robust and faster; No optimization process is required that can slow down the algorithm in high dimensions and can fail even if the cost function is quadratic because of rounding-off errors as in the case of SVM.

- 3.

- Complexity: SVM complexity grows quadratically with the number of classes (requiring hyperplanes), while KOS scales linearly, needing only n sets of eigenpairs.

- 4.

- Time efficiency: As a result of the two previous proprieties, KOS is significantly faster than SVM, up to more than 60 times faster in certain tests as shown in Table 4.

- 5.

- Parallelization: KOS is highly parallelizable since all subspaces are independent..

- 6.

- Dynamic classification: In the case of class creation or cancellation, SVM requires recalculating all feature-space hyperplanes. By contrast, KOS only requires computing eigenpairs of the Mercer kernel matrix for the new class, with no update needed for canceled classes.

- 7.

- Imbalanced classes: In KOS, this issue is naturally handled by subdividing large classes into smaller, balanced subclasses (Section 2.6). This avoids the need for artificial attributes, which may distort the data structure, or the use of balancing weights, which often lack a clear and systematic procedure.

4. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Proof of the POD Best Representatives

References

- Alpaydin, E. Introduction to Machine Learning (Fourth ed.). MIT. pp. xix, 1–3, 13–18. (2020). ISBN 978-0262043793.

- Vapnik, V. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory. Springer-Verlag, NY, USA, 1995.

- Vapnik, V. Statistical Learning Theory. Wiley, NY, USA, 1998.

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support vector networks, Machine Learning, 20. 20:1–25, 1995.

- Mercer, J. Functions of positive and negative type and their connection with the theory of integral equations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, A(209):415–446, 1909.

- Wang, H.; Li, G.; Wang, Z. Fast SVM classifier for large-scale classification problems. Information Sciences, Volume 642, September 2023.

- Shao, Y.H.; Lv, X.J.; Huang, L.W.; Bai Wang, L. Twin SVM for conditional probability estimation in binary and multiclass classification. Pattern Recognition, Volume 136, April 2023.

- Wang, H.; Shao, Y. Fast generalized ramp loss support vector machine for pattern classification. Pattern Recognition, Volume 146, February 2024.

- Wang, B.Q.; Guan, X.P.; Zhu, J.W.; Gu, C.C.; Wu, K.J.; Xu, J.J. SVMs multi-class loss feedback based discriminative dictionary learning for image classification. Pattern Recognition, Volume 112, April 2021.

- Borah, P.; Gupta, D. UFunctional iterative approaches for solving support vector classification problems based on generalized Huber loss. Neural Computing and Applications, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 1135–1139, 2020.

- Gaye, B.; Zhang, D.; Wulamu, A. Improvement of Support Vector Machine Algorithm in Big Data Background. Hindawi Mathematical Problems in Engineering, Volume 2021,June 2021, Article ID 5594899, 9 pages. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liu, X. Advances on support vector machines research. Technological and Economic development of economy. iSSN 2029-4913 print/iSSN 2029-4921 online, 2012 Volume 18(1): 5–33. [CrossRef]

- Ayat, N.E.; Cheriet, M.; Remaki, L.; Suen, C.Y. KMOD-A New Support Vector Machine Kernel With Moderate Decreasing for Pattern Recognition. Application to Digit Image Recognition. Proceedings of Sixth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, pp.1215-1219, 2001.

- Lin, S.W.; Ying, K. C; Chen, S.C.; Lee, ZJ. Particle swarm optimization for parameter determination and feature selection of support vector machines. Expert Systems with Applications, 2008; 35: 1817-1824.

- Syarif, I.; Prugel-Bennett, A.; Wills, G. SVM Parameter Optimization Using Grid Search and Genetic Algorithm to Improve Classification Performance. TELKOMNIKA, Vol.14, No.4, December 2016, pp. 1502-1509 ISSN: 1693-6930. [CrossRef]

- Shekar, B.H. ;G. Dagnew, G. Grid Search-Based Hyperparameter Tuning and Classification of Microarray Cancer Data. Second International Conference on Advanced Computational and Communication Paradigms, (ICACCP)2019.

- Hinton, E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Computation, 18:1527–1554, 2006.

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random Search for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 13 (2012) 281-305.

- Volkwein, S. Proper orthogonal decomposition: Theory and reduced-order modelling Lecture Notes, University of Konstanz, 2013, 4.

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. Smote: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 16, 321–357 (2002).

- Chang, C.C.; Lin, C.J. LIBSVM : a library for support vector machines. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 2:27:1–27:27, 2011. Software available at https://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/ cjlin/libsvm/.

- Wang, W.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Y. Kernel PCA feature extraction and the SVM classification algorithm for multiple-status, through-wall, human being detection. EURASIP Journal of wireless communication and Networking, (2017) 2017:151.

- Golub, T.R.; Slonim, D.K.; Tamayo, P.; Huard, C.; Gaasenbeek, M.; Mesirov, J.P.; Coller, H.; Loh, M.L.; Downing, J.R.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Lander, E.S. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science, 286(5439):531, 1999.

- Hsu, C.W.; Chang, C. C,; C.J Lin. A practical guide to support vector classification. Technical report, Department of Computer Science, National Taiwan University, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Available online:http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/index.php.

- Available online: https://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/ cjlin/libsvmtools/datasets/.

- Guyon, I.; Gunn, S.; Ben Hur, A.; Dror, G. Result analysis of the NIPS 2003 feature selection challenge. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 17. 2005.

- Hsu, C.W.; Lin, C.J. A comparison of methods for multi-class support vector machines. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 13(2):415–425, 2002.

- Hull, J.J. A database for handwritten text recognition research. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 16(5):550–554, May 1994.

- Remaki, L. Efficient Alternative to SVM Method in Machine Learning. In: Arai, K. (eds) Intelligent Computing. 2025. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 1426. Springer, Cham.

| Test name | NB of Classes | Description/Reference | Training set size/ Class sizes |

Testing set size/ Feature vector size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia | 2 | Molecular classification of cancer [23] |

|

7129 |

| svmguide1 | 2 | Astroparticle application [24] |

|

4 |

| splice | 2 | Splice junctions in a DNA sequence [25] |

|

60 |

| austrian | 2 | Credit Approval dataset [26] |

|

14 |

| madelon 2 | Analysis of the NIPS 2003 [27] |

|

14 |

| Test name | NB of Classes | Description/Reference | Training set size/ Class sizes |

Testing set size/ Feature vector size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | 3 | DNA [28] |

|

180 |

| Satimage | 6 | Satelit images [28] | 4435 |

2000 36 |

| USPS | 10 | handwritten text recognition dataset [29] |

|

256 |

| letter | 26 | letter recognition dataset [29] |

|

16 |

| shuttle | 7 | space shuttle’ sensors [29] |

|

9 |

| name/ Classes | Test size | SVM-rate of success |

KOS-rate of success |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia/2 | Test. # 34 | ||

| svmguide1/2 | Test. # 4000 | ||

| splice/2 | Test. # 2175 | ||

| austrian/2 | Test. # 341 | ||

| madelon/2 | Test. # 600 | ||

| DNA/3 | Test. # 1186 | ||

| Satimage/6 | Test. # 200 | ||

| USPS/10 | Test. # 2007 | ||

| letter/26 | Test. # 5000 | ||

| shuttle/7 | Test. # 14,500 |

| name/ Classes | Test size | SVM processing time |

KOS processing time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia/2 | Test. # 34 | ||

| svmguide1/2 | Test. # 4000 | ||

| splice/2 | Test. # 2175 | ||

| austrian/2 | Test. # 341 | ||

| madelon/2 | Test. # 600 | ||

| DNA/3 | Test. # 1186 | ||

| Satimage/6 | Test. # 200 | ||

| USPS/10 | Test. # 2007 | ||

| letter/26 | Test. # 5000 | ||

| shuttle/7 | Test. # 14,500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).