Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

Patient Selection

Data Collection

Fluid Data

Acute Kidney Injury and mRAI

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Laboratory Findings

Acute Kidney Injury

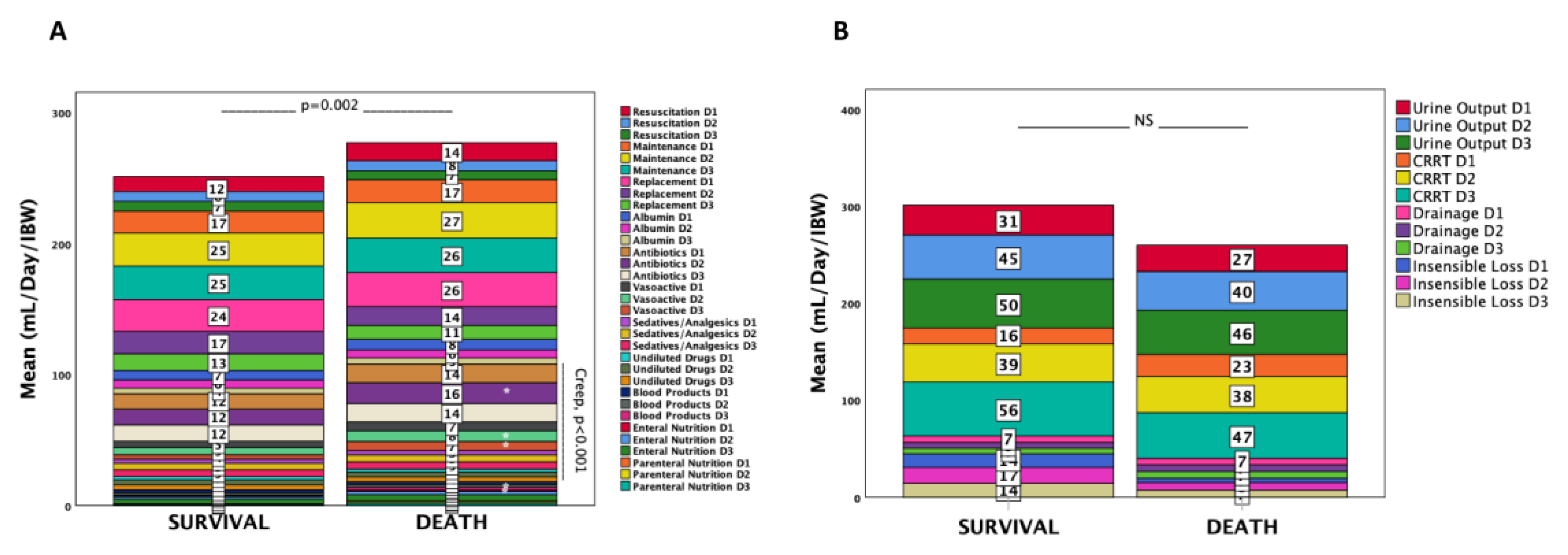

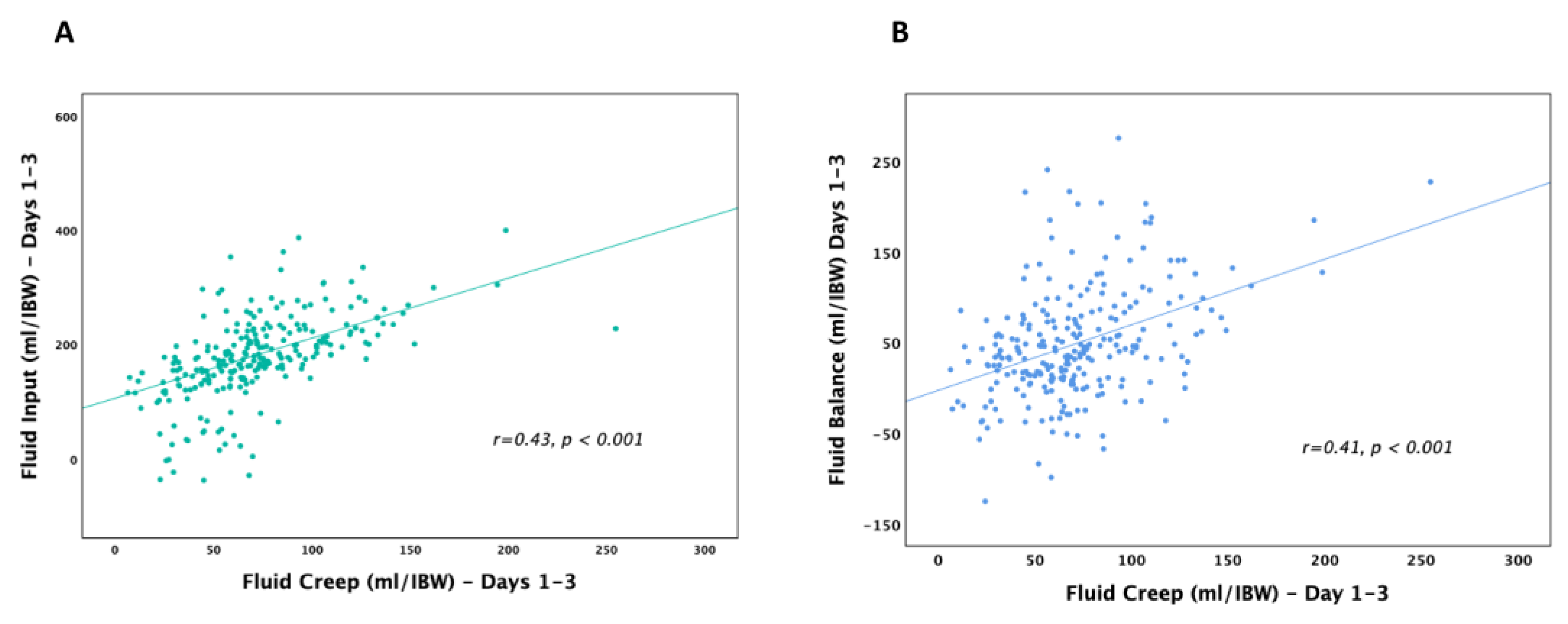

Categories of Administered Fluids

Pre-ICU

ICU Days 1–3

Fluid Types

Fluid Overload

Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| FO | Fluid Overload |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| mRAI | modified Renal Angina Index |

| IBM | Ideal Body Weight |

References

- Alobaidi, R.; Morgan, C.; Basu, R.K.; Stenson, E.; Featherstone, R.; Majumdar, S.R.; Bagshaw, S.M. Association Between Fluid Balance and Outcomes in Critically Ill Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2018, 172, 257–268. [CrossRef]

- Lintz, V.C.; Vieira, R.A.; Carioca, F. de L.; Ferraz, I. de S.; Silva, H.M.; Ventura, A.M.C.; de Souza, D.C.; Brandão, M.B.; Nogueira, R.J.N.; de Souza, T.H. Fluid Accumulation in Critically Ill Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 74, 102714. [CrossRef]

- Renaudier, M.; Lascarrou, J.-B.; Chelly, J.; Lesieur, O.; Bourenne, J.; Jaubert, P.; Paul, M.; Muller, G.; Leprovost, P.; Klein, T.; et al. Fluid Balance and Outcome in Cardiac Arrest Patients Admitted to Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care 2025, 29, 152. [CrossRef]

- Pfortmueller, C.A.; Dabrowski, W.; Wise, R.; van Regenmortel, N.; Malbrain, M.L.N.G. Fluid Accumulation Syndrome in Sepsis and Septic Shock: Pathophysiology, Relevance and Treatment-a Comprehensive Review. Ann Intensive Care 2024, 14, 115. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.; Flindall, H.; Basmaji, J.; Ablordeppey, E.; Díaz-Gómez, J.L.; Lanspa, M.; Nikravan, S.; Piticaru, J.; Lewis, K. Critical Care Ultrasonography for Volume Management: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Trials. Crit Care Explor 2025, 7, e1261. [CrossRef]

- Woodward, C.W.; Lambert, J.; Ortiz-Soriano, V.; Li, Y.; Ruiz-Conejo, M.; Bissell, B.D.; Kelly, A.; Adams, P.; Yessayan, L.; Morris, P.E.; et al. Fluid Overload Associates With Major Adverse Kidney Events in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury Requiring Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. Crit Care Med 2019, 47, e753–e760. [CrossRef]

- Vignon, P.; Evrard, B.; Asfar, P.; Busana, M.; Calfee, C.S.; Coppola, S.; Demiselle, J.; Geri, G.; Jozwiak, M.; Martin, G.S.; et al. Fluid Administration and Monitoring in ARDS: Which Management? Intensive Care Med 2020, 46, 2252–2264. [CrossRef]

- Charaya, S.; Angurana, S.K.; Nallasamy, K.; Jayashree, M. Restricted versus Usual/Liberal Maintenance Fluid Strategy in Mechanically Ventilated Children: An Open-Label Randomized Trial (ReLiSCh Trial). Indian J Pediatr 2025, 92, 7–14. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Soriano, V.; Kabir, S.; Claure-Del Granado, R.; Stromberg, A.; Toto, R.D.; Moe, O.W.; Goldstein, S.L.; Neyra, J.A. Assessment of a Modified Renal Angina Index for AKI Prediction in Critically Ill Adults. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2022, 37, 895–903. [CrossRef]

- Langer, T.; D’Oria, V.; Spolidoro, G.C.I.; Chidini, G.; Scalia Catenacci, S.; Marchesi, T.; Guerrini, M.; Cislaghi, A.; Agostoni, C.; Pesenti, A.; et al. Fluid Therapy in Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Children: The Sodium, Chloride and Water Burden of Fluid Creep. BMC Pediatr 2020, 20, 424. [CrossRef]

- Van Regenmortel, N.; Verbrugghe, W.; Roelant, E.; Van den Wyngaert, T.; Jorens, P.G. Maintenance Fluid Therapy and Fluid Creep Impose More Significant Fluid, Sodium, and Chloride Burdens than Resuscitation Fluids in Critically Ill Patients: A Retrospective Study in a Tertiary Mixed ICU Population. Intensive Care Med 2018, 44, 409–417. [CrossRef]

- Messmer, A.; Pietsch, U.; Siegemund, M.; Buehler, P.; Waskowski, J.; Müller, M.; Uehlinger, D.E.; Hollinger, A.; Filipovic, M.; Berger, D.; et al. Protocolised Early De-Resuscitation in Septic Shock (REDUCE): Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Multicentre Feasibility Trial. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e074847. [CrossRef]

- Gamble, K.C.; Smith, S.E.; Bland, C.M.; Sikora Newsome, A.; Branan, T.N.; Hawkins, W.A. Hidden Fluids in Plain Sight: Identifying Intravenous Medication Classes as Contributors to Intensive Care Unit Fluid Intake. Hosp Pharm 2022, 57, 230–236. [CrossRef]

- Sakuraya, M.; Yoshihiro, S.; Onozuka, K.; Takaba, A.; Yasuda, H.; Shime, N.; Kotani, Y.; Kishihara, Y.; Kondo, N.; Sekine, K.; et al. A Burden of Fluid, Sodium, and Chloride Due to Intravenous Fluid Therapy in Patients with Respiratory Support: A Post-Hoc Analysis of a Multicenter Cohort Study. Ann Intensive Care 2022, 12, 100. [CrossRef]

- Bihari, S.; Prakash, S.; Potts, S.; Matheson, E.; Bersten, A.D. Addressing the Inadvertent Sodium and Chloride Burden in Critically Ill Patients: A Prospective before-and-after Study in a Tertiary Mixed Intensive Care Unit Population. Crit Care Resusc 2018, 20, 285–293.

- Van Regenmortel, N.; Moers, L.; Langer, T.; Roelant, E.; De Weerdt, T.; Caironi, P.; Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; Elbers, P.; Van den Wyngaert, T.; Jorens, P.G. Fluid-Induced Harm in the Hospital: Look beyond Volume and Start Considering Sodium. From Physiology towards Recommendations for Daily Practice in Hospitalized Adults. Ann Intensive Care 2021, 11, 79. [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, R.; Srisawat, N.; Claure-Del Granado, R.; Doi, K.; Yoshida, T.; Nangaku, M.; Noiri, E. Use of the Renal Angina Index in Determining Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Rep 2018, 3, 677–683. [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.K.; Kaddourah, A.; Goldstein, S.L.; AWARE Study Investigators Assessment of a Renal Angina Index for Prediction of Severe Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Children: A Multicentre, Multinational, Prospective Observational Study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018, 2, 112–120. [CrossRef]

- Mohoric, S.; Alobaidi, R.; McGraw, T.; Joffe, A.R. The Determinants of Fluid Accumulation in Critically Ill Children: A Prospective Single-Center Cohort Study. Pediatr Nephrol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, A.; Bamne, P.; Upadhyay, N.; Pandwar, U.; Shrivastava, J. Impact of Fluid Overload on Mortality Among Critically Ill Pediatric Patients: An Observational Study at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Central India. Cureus 2025, 17, e82178. [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.B.; Akhondi-Asl, A.; Mehta, N.; Yang, Y. Association between Early Fluid Overload and Clinical Outcomes in a Pediatric ICU. Pediatr Res 2025. [CrossRef]

- Van Regenmortel, N.; Verbrugghe, W.; Roelant, E.; Van den Wyngaert, T.; Jorens, P.G. Maintenance Fluid Therapy and Fluid Creep Impose More Significant Fluid, Sodium, and Chloride Burdens than Resuscitation Fluids in Critically Ill Patients: A Retrospective Study in a Tertiary Mixed ICU Population. Intensive Care Med 2018, 44, 409–417. [CrossRef]

- Molin, C.; Wichmann, S.; Schønemann-Lund, M.; Møller, M.H.; Bestle, M.H. Sodium and Chloride Disturbances in Critically Ill Adult Patients: A Protocol for a Sub-Study of the FLUID-ICU Cohort Study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2025, 69, e70028. [CrossRef]

- Gamble, K.C.; Smith, S.E.; Bland, C.M.; Sikora Newsome, A.; Branan, T.N.; Hawkins, W.A. Hidden Fluids in Plain Sight: Identifying Intravenous Medication Classes as Contributors to Intensive Care Unit Fluid Intake. Hosp Pharm 2022, 57, 230–236. [CrossRef]

- Self, W.H.; Semler, M.W.; Wanderer, J.P.; Wang, L.; Byrne, D.W.; Collins, S.P.; Slovis, C.M.; Lindsell, C.J.; Ehrenfeld, J.M.; Siew, E.D.; et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Noncritically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 819–828. [CrossRef]

- Messina, A.; Matronola, G.M.; Cecconi, M. Individualized Fluid Optimization and De-Escalation in Critically Ill Patients with Septic Shock. Curr Opin Crit Care 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, J.; Soroko, S.B.; Chertow, G.M.; Himmelfarb, J.; Ikizler, T.A.; Paganini, E.P.; Mehta, R.L.; Program to Improve Care in Acute Renal Disease (PICARD) Study Group Fluid Accumulation, Survival and Recovery of Kidney Function in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int 2009, 76, 422–427. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, B.; Wen, Y.; Xi, X.-M.; Beijing Acute Kidney Injury Trial (BAKIT) Workgroup Fluid Balance and Mortality in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury: A Multicenter Prospective Epidemiological Study. Crit Care 2015, 19, 371. [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, J.; Soroko, S.B.; Chertow, G.M.; Himmelfarb, J.; Ikizler, T.A.; Paganini, E.P.; Mehta, R.L.; Program to Improve Care in Acute Renal Disease (PICARD) Study Group Fluid Accumulation, Survival and Recovery of Kidney Function in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int 2009, 76, 422–427. [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, E.; Naruse, H.; Ishihara, Y.; Hattori, H.; Yamada, A.; Kawai, H.; Muramatsu, T.; Tsuboi, Y.; Fujii, R.; Suzuki, K.; et al. Assessment of the Renal Angina Index in Patients Hospitalized in a Cardiac Intensive Care Unit. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 75. [CrossRef]

- Waskowski, J.; Salvato, S.M.; Müller, M.; Hofer, D.; van Regenmortel, N.; Pfortmueller, C.A. Choice of Creep or Maintenance Fluid Type and Their Impact on Total Daily ICU Sodium Burden in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Crit Care 2023, 78, 154403. [CrossRef]

- Bihari, S.; Prakash, S.; Potts, S.; Matheson, E.; Bersten, A.D. Addressing the Inadvertent Sodium and Chloride Burden in Critically Ill Patients: A Prospective before-and-after Study in a Tertiary Mixed Intensive Care Unit Population. Crit Care Resusc 2018, 20, 285–293.

- Verma, B.; Luethi, N.; Cioccari, L.; Lloyd-Donald, P.; Crisman, M.; Eastwood, G.; Orford, N.; French, C.; Bellomo, R.; Martensson, J. A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Pilot Study of Fluid Resuscitation with Saline or Plasma-Lyte 148 in Critically Ill Patients. Crit Care Resusc 2016, 18, 205–212.

- Hammond, N.E.; Zampieri, F.G.; Di Tanna, G.L.; Garside, T.; Adigbli, D.; Cavalcanti, A.B.; Machado, F.R.; Micallef, S.; Myburgh, J.; Ramanan, M.; et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Critically Ill Adults - A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. NEJM Evid 2022, 1, EVIDoa2100010. [CrossRef]

- Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; Van Regenmortel, N.; Saugel, B.; De Tavernier, B.; Van Gaal, P.-J.; Joannes-Boyau, O.; Teboul, J.-L.; Rice, T.W.; Mythen, M.; Monnet, X. Principles of Fluid Management and Stewardship in Septic Shock: It Is Time to Consider the Four D’s and the Four Phases of Fluid Therapy. Ann Intensive Care 2018, 8, 66. [CrossRef]

- Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; Van Regenmortel, N.; Saugel, B.; De Tavernier, B.; Van Gaal, P.-J.; Joannes-Boyau, O.; Teboul, J.-L.; Rice, T.W.; Mythen, M.; Monnet, X. Principles of Fluid Management and Stewardship in Septic Shock: It Is Time to Consider the Four D’s and the Four Phases of Fluid Therapy. Ann Intensive Care 2018, 8, 66. [CrossRef]

- Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; Martin, G.; Ostermann, M. Everything You Need to Know about Deresuscitation. Intensive Care Med 2022, 48, 1781–1786. [CrossRef]

- Gist, K.M.; Selewski, D.T.; Brinton, J.; Menon, S.; Goldstein, S.L.; Basu, R.K. Assessment of the Independent and Synergistic Effects of Fluid Overload and Acute Kidney Injury on Outcomes of Critically Ill Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2020, 21, 170–177. [CrossRef]

- Vaara, S.T.; Korhonen, A.-M.; Kaukonen, K.-M.; Nisula, S.; Inkinen, O.; Hoppu, S.; Laurila, J.J.; Mildh, L.; Reinikainen, M.; Lund, V.; et al. Fluid Overload Is Associated with an Increased Risk for 90-Day Mortality in Critically Ill Patients with Renal Replacement Therapy: Data from the Prospective FINNAKI Study. Crit Care 2012, 16, R197. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, G.; Wang, D.; Lei, Y.; Mao, Z.; Hu, P.; Hu, J.; Liu, R.; Han, D.; Zhou, F. Balanced Crystalloids versus Normal Saline for Fluid Resuscitation in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis. Am J Emerg Med 2019, 37, 2072–2078. [CrossRef]

- Van Regenmortel, N.; Verbrugghe, W.; Roelant, E.; Van den Wyngaert, T.; Jorens, P.G. Maintenance Fluid Therapy and Fluid Creep Impose More Significant Fluid, Sodium, and Chloride Burdens than Resuscitation Fluids in Critically Ill Patients: A Retrospective Study in a Tertiary Mixed ICU Population. Intensive Care Med 2018, 44, 409–417. [CrossRef]

| Patient Characteristics | Total | Survival | Death | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 250 (100) | 171 (68.4) | 79 (31.6) | p-value |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.115 | |||

| • Male | 160 (64.0) | 115 (67.3) | 45 (57.0) | |

| • Female | 90 (36.0) | 56 (32.7) | 34 (43.0) | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 64.8 ± 17 | 63.6 ± 17 | 67.5 ± 16 | 0.081 |

| Body weight (kg), mean ± SD | 80.1 ± 17 | 82.1 ± 17 | 75.8 ± 16 | 0.006 |

| BMI (kg/m²), mean ± SD | 28.2 ± 5.6 | 28.6 ± 5.6 | 27.4 ± 5.6 | 0.124 |

| BMI Nutritional Status, n (%) | 0.156 | |||

| • Undernutrition | 8 (3.2) | 7 (4.1) | 1 (1.3) | |

| • Normal weight | 118 (47.2) | 73 (42.7) | 45 (57.0) | |

| • Overweight | 93 (37.2) | 69 (40.4) | 24 (30.4) | |

| • Obesity | 31 (12.4) | 22 (12.9) | 9 (11.4) | |

| APACHE II score, mean ± SD | 21.9 ± 7.8 | 21.1 ± 7.5 | 23.8 ± 8.4 | 0.068 |

| SOFA score, mean ± SD | 8.45 ± 7.8 | 8.18 ± 2.9 | 9.05 ± 3.0 | 0.032 |

| Glascow Coma Scale, mean ± SD | 6.6 ± 4.9 | 7.0 ± 5.2 | 5.7 ± 4.2 | 0.049 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 231 (92.4) | 156 (91.2) | 75 (94.9) | 0.560 |

| Admission Type, n (%) | 0.020 | |||

| Medical, n (%) | 154 (61.6) | 97 (56.7) | 57 (72.2) | |

| Surgical, n (%) | 96 (38.4) | 74 (43.3) | 22 (27.8) | |

| Nosocomial Infection, n (%) | 89 (35.6) | 49 (28.7) | 40 (50.6) | <0.001 |

| Primary Clinical Diagnoses | 0.125 | |||

| Respiratory | 90 (36.0) | 55 (32.2) | 35 (44.3) | |

| Cardiac | 8 (3.2) | 6 (3.5) | 2 (2.5) | |

| Sepsis/Septic Shock | 47 (18.8) | 27 (15.8) | 20 (25.3) | |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | 17 (6.8) | 13 (7.6) | 4 (5.1) | |

| Surgery | 43 (17.2) | 35 (20.5) | 8 (10.1) | |

| Neurological | 21 (8.4) | 17 (9.9) | 4 (5.1) | |

| Other | 19 (7.6) | 14 (8.2) | 5 (6.3) | |

| Admission day worst value | ||||

| Heart rate,mean±SD | 80.1 ± 32 | 78.6 ± 30 | 83.5 ± 35 | 0.253 |

| Respiratory rate,mean±SD | 26.3 ± 5.8 | 26.2 ± 31 | 26.6 ± 6.1 | 0.566 |

| Systolic blood pressure,mean±SD | 115 ± 29.3 | 114 ± 27.7 | 115 ± 32 | 0.740 |

| Diastolic blood pressure,mean±SD | 58.4 ± 15 | 59.0 ± 15 | 57.1 ± 15 | 0.343 |

| Mean Blood Pressure,mean±SD | 77.1 ± 17 | 77.5 ± 17 | 76.3 ± 19 | 0.612 |

| SpO2 (%), mean±SD | 94.6 ± 4.5 | 94.9 ± 4.3 | 94.1 ± 4.9 | 0.179 |

| Therapeutic Interventions, n (%) | ||||

| • Mechanical ventilation | 97 (39.6) | 28 (16.9) | 69 (87.3) | <0.001 |

| • Vasoactive agents | 71 (28.5) | 10 (5.9) | 61 (77.2) | <0.001 |

| ICU stay (days), mean ± SD | 15.1 ± 16 | 14.2 ± 16 | 16.9 ± 16 | 0.220 |

| Hospital stays (days), mean ± SD | 35.6 ± 31 | 39.3 ± 31 | 27.7 ± 29 | 0.006 |

| Mechanical ventilation (days), mean ± SD | 14.5 ± 16 | 13.3 ± 16 | 16.9 ± 16 | 0.098 |

| Vasoactive therapy (days), mean ± SD | 11.8 ± 12 | 9.9 ± 11 | 15.5 ± 14 | <0.001 |

| Clinical characteristics | Total | Survivors | Non-survivors | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 250 (100) | 171 (68.4) | 79 (31.6) | |

| Urea D1 (mg/dL), mean±SD | 65.4 ± 48 | 61.4 ± 48 | 73.9 ± 48 | 0.056 |

| Urea D2 (mg/dL), mean±SD | 59.1 ± 40 * | 55.2 ± 40 * | 67.5 ± 39 | 0.023 |

| Urea D3 (mg/dL), mean±SD | 51.5 ± 33 *,** | 47.1 ± 30 *,** | 60.9 ± 36 * | 0.0092 |

| Creatinine D1 (mg/dL), mean±SD | 1.42 ± 1.2 | 1.40 ± 1.3 | 1.44 ± 1.1 | 0.836 |

| Creatinine D2 (mg/dL), mean±SD | 1.36 ± 1.0 | 1.33 ± 0.9 | 1.44 ± 1.0 | 0.421 |

| Creatinine D3 (mg/dL), mean±SD | 1.22 ± 0.7 *,** | 1.17 ± 0.7 *,** | 1.33 ± 0.8 ** | 0.107 |

| ClCr D1 (ml/min/1.73m2),mean±SD | 51.7 ± 37 | 53.5 ± 37 | 47.6 ± 37 | 0.244 |

| ClCr D2 (ml/min/1.73m2),mean±SD | 51.9 ± 38 | 54.2 ± 37 | 47.1 ± 39 | 0.173 |

| ClCr D3 (ml/min/1.73m2), mean±SD | 55.0 ± 39 *,** | 57.8 ± 38 *,** | 49.1 ± 40 | 0.101 |

| AKI at admission, n (%) | ||||

| KDIGO 1 | 46 (48.9) | 28 (50.9) | 18 (46.2) | 0.901 |

| KDIGO 2 | 23 (24.5) | 13 (23.6) | 10 (25.6) | |

| KDIGO 3 | 25 (26.6) | 14 (25.5) | 11 (28.2) | |

| KDIGO2 (day 3), n (%) | 52 (20.8) | 19 (14.6) | 33 (27.7) | 0.011 |

| KDIGO2 (day 7), n (%) | 48 (21.8) | 15 (12.8) | 33 (32.0) | <0.001 |

| mRAI (score), mean±SD | 7.1 ± 7.8 | 6.4 ± 7.1 | 8.6 ± 8.9 | 0.043 |

| mRAI (6–40), n (%) | 62 (24.8) | 36 (21.1) | 26 (32.9) | 0.044 |

| Nephrotoxicity, n (%) | 0.164 | |||

| Nephrotoxic (NF) Drugs | 49 (19.6) | 40 (23.4) | 9 (11.4) | |

| Contrast Agents (CA) | 80 (32) | 51 (29.8) | 29 (36.7) | |

| AC and NF drugs | 31 (12.4) | 20 (11.7) | 11 (13.9) | |

| None | 90 (36) | 60 (35.1) | 30 (38.0) | |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 184 (93.9) | 134 (92.4) | 50 (98.0) | 0.150 |

| CRRT, n (%) | 59 (24.1) | 19 (14.8) | 40 (34.2) | <0.001 |

| Diuretics, (days), mean±SD | 11.1 ± 14 | 10.7 ± 15 | 11.9 ± 13 | 0.559 |

| CRRT, (days), mean±SD | 10.5 ± 10 | 8.7 ± 7.4 | 12.9 ± 13 | 0.201 |

| Clinical characteristics | Total | Survivors | Non-survivors | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 250 (100) | 171 (68.4) | 79 (31.6) | |

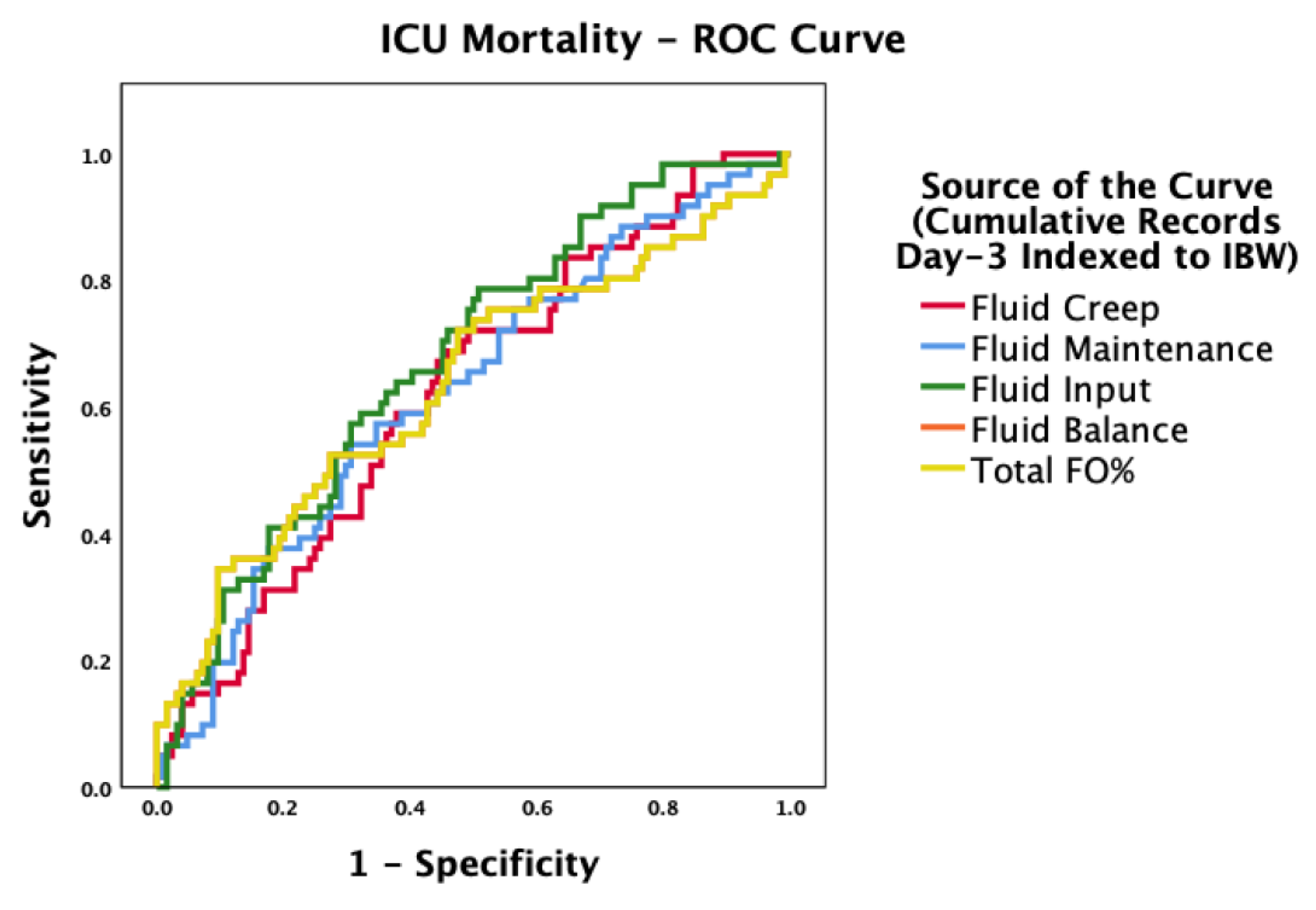

| Total Input (ml), mean±SD | 11561 ± 5366 | 11024 ± 5943 | 12724 ± 3599 | 0.020 |

| Total Input (ml/IBW), mean±SD | 180.7 ± 85.5 | 169.3 ± 91.5 | 205.5 ± 64.8 | 0.002 |

| Total Output (ml), mean±SD | 9627 ± 4226 | 10007 ± 4426 | 8804 ± 3649 | 0.036 |

| Total Output (ml/IBW), mean±SD | 148.9 ± 60.3 | 152.7 ± 62.0 | 140.5 ± 54.1 | 0.137 |

| Fluid Balance (ml), mean±SD | 3038 ± 3877 | 2327 ± 3298 | 4577 ± 4556 | <0.001 |

| Fluid Balance (ml/IBW), mean±SD | 48.8 ± 62.0 | 36.6 ± 52.1 | 75.1 ± 73.1 | <0.001 |

| FO%, mean±SD | 4.9 ± 6.2 | 3.7 ± 5.2 | 7.5 ± 7.3 | <0.001 |

| FO > 10% (clinically significant), n (%) | 43 (17.2) | 16 (9.4) | 27 (34.2) | <0.001 |

| FO > 15% (severe), (%) | 17 (6.8) | 5 (2.9) | 12 (15.2) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).