Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

To investigate the early developmental characteristics and mitochondrial inheritance patterns of the hybrid offspring of a paternal Plectropomus leopardus and maternal Epinephelus fasciatus, the study systematically mapped the embryonic developmental trajectory and mitochondrial genome of the new germplasm. Results revealed that the fertilized hybrid eggs completed embryonic development within 28h55min, with the newly hatched larvae measuring 2.05 ± 0.37 mm in total length. The mitochondrial genome length of the hybrid was 16,570 bp, preserving 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), two ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, and 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes. The hybrid's mitochondrial gene composition and arrangement showed high consistency with that of the maternal E. fasciatus. Concurrently, the co-linearity, Ka/Ks, and phylogenetic tree analyses collectively indicate that the hybrid progeny has a closer genetic relationship with the maternal parent, supporting the mitochondrial maternal inheritance of this species. This study details the embryonic development and mitochondrial inheritance of an intergeneric hybrid grouper germplasm, providing significant molecular biological evidence for grouper hybrid breeding, germplasm resource identification, and genetic diversity conservation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Observation

2.2. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.3. Mitochondrial Genome Assembly and Gene Annotation

2.4. Genome Collinearity Analysis

2.5. Ka/Ks Analysis

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Embryonic Development Observation and Mitochondrial Group Comparative Analysis

3.2. Mitochondrial Genome Composition

3.3. Analysis of Mitochondrial PCGs

3.4. Collinearity Analysis

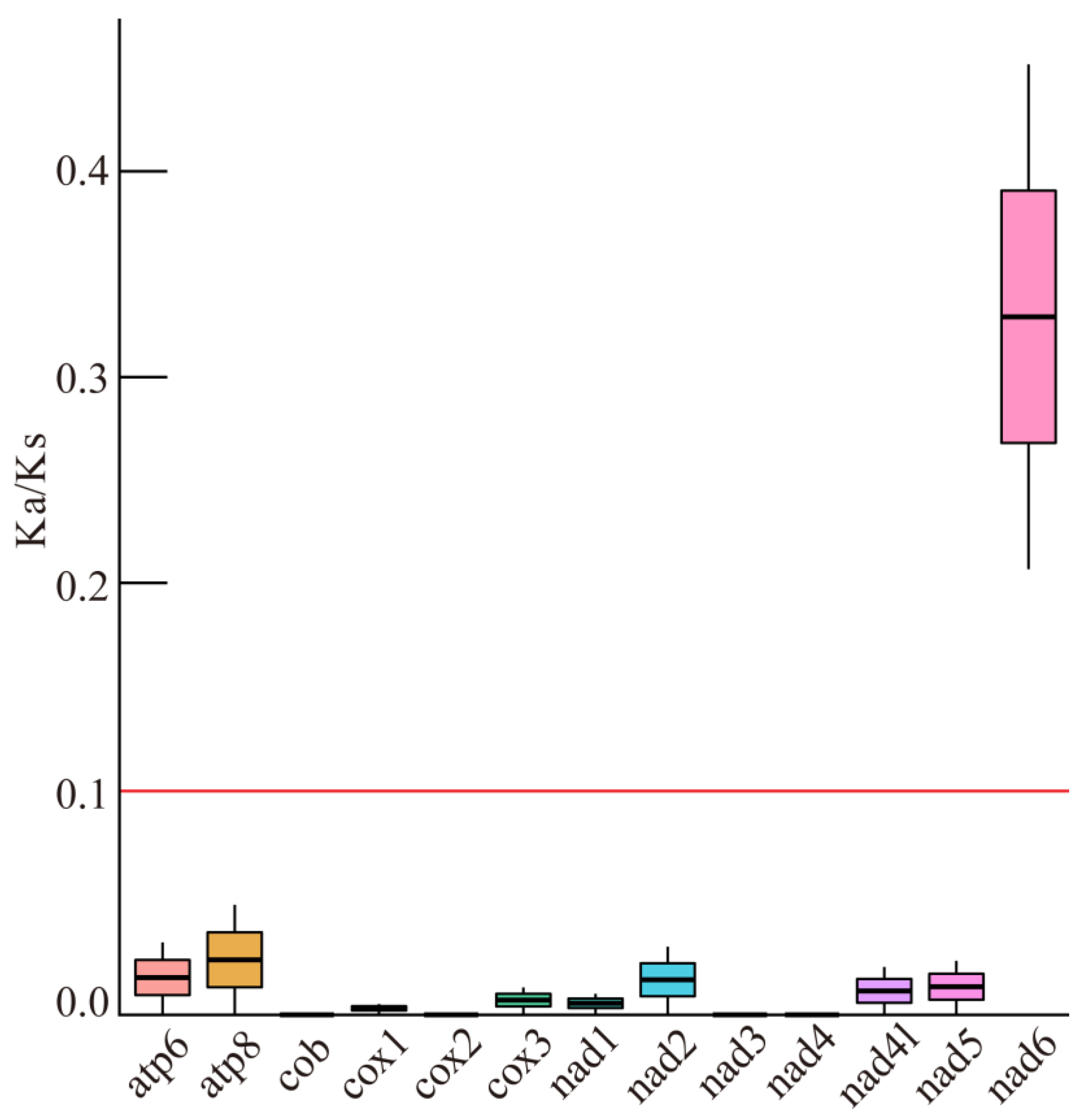

3.5. Ka/Ks Analysis

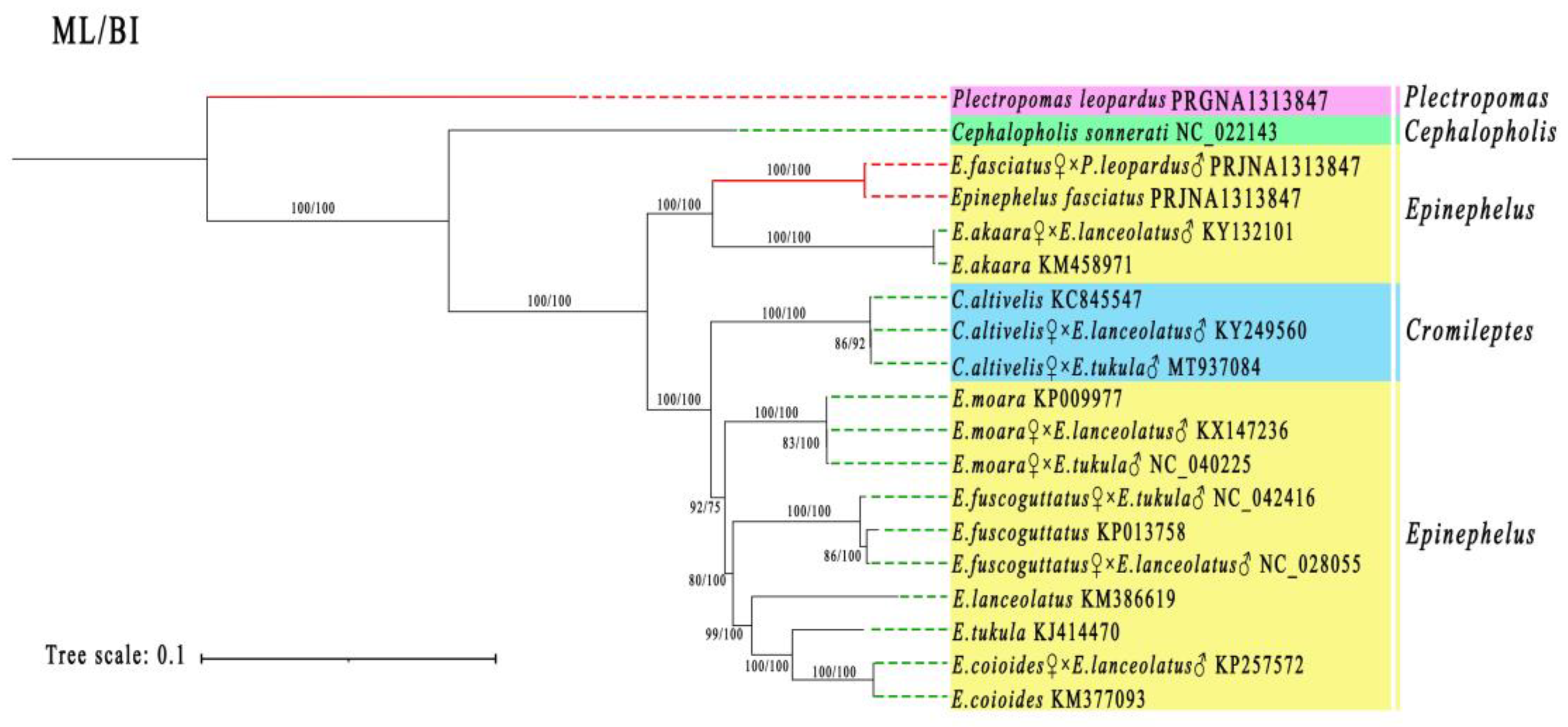

3.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuriiwa, K.; Chiba, S.N.; Motomura, H.; Matsuura, K. Phylogeography of Blacktip Grouper, Epinephelus fasciatus (Perciformes: Serranidae), and influence of the Kuroshio Current on cryptic lineages and genetic population structure. Ichthyol. Res. 2014, 61, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Hao, R.; Tian, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, C.; Li, G. Integrative Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Analysis of Body Color Formation in the Leopard Coral Grouper (Plectropomus leopardus). Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratchett, M.S.; Caballes, C.F.; Hobbs, J.-P.A.; DiBattista, J.D.; Bergseth, B.; Waldie, P.; Champion, C.; Mc Cormack, S.P.; Hoey, A.S. Variation in the Physiological Condition of Common Coral Trout (Plectropomus leopardus) Unrelated to Coral Cover on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Fishes 2023, 8, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- THàNH P N, TAKAFUMI A. Growth, sexual transition, and maturation of blacktip grouper Epinephelus fasciatus under long-term artificial rearing: Puberty and its associated physiological and endocrine changes. 2022.

- Kawabe, K.; Kohno, H. Morphological development of larval and juvenile blacktip grouper, Epinephelus fasciatus. Fish. Sci. 2009, 75, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xia, S.; Feng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Rahman, M.M.; Rajkumar, M.; Jiang, S. Effects of water temperature on survival, growth, digestive enzyme activities, and body composition of the leopard coral grouper Plectropomus leopardus. Fish. Sci. 2014, 81, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TIAN Y S, CHEN Z F, DUAN H M. The family line establishment of the hybrid Epinephelus moara(♀)× E. lanceolatus(♂) by using cryopreserved sperm and the related genetic effect analysis. J. Fish. 1: China 2017, 41(12), 2017.

- CHEN S, TIAN Y. Heterosis in growth and low temperature tolerance in Jinhu grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀× Epinephelus tukula♂). 7: Aquaculture 2023, 562, 2023.

- LI Z T, TIAN Y S, CHENG M L. Comparison of development and growth of hybrid Chromileptes altivelis (♀) × Epinephelus tukula(♂). 1: South China Fisheries Science 2020, 16(1), 2020.

- GONG S, WANG T. Development and characterization of a novel intergeneric hybrid grouper (Cromileptes altivelis♀× Epinephelus lanceolatus♂). 7: Aquaculture 2025, 595, 2025.

- Yan, F.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Gan, S.; Lin, H.R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S. Transcriptome analysis reveals the dynamics of gene expression during early embryonic development of hybrid groupers. Aquaculture 2024, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Ma, W.; et al. Construction of high-density linkage maps and QTL mapping for growth-related traits in F1 hybrid Yunlong grouper (Epinephelus moara♀ × E. lanceolatus♂). Aquaculture 2022, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DING T T, TIAN Y S, BAI D Q. Observation on Embryonic and Post-Embryonic Development, and Morphological Changes of Larval, Juvenile and Young Epinephelus fasciatus. Progress in Fishery Sciences 2025: 1-11.10.19663/j.issn2095-9869. 2024.

- L L Y, C C, Y W Q. Comparative analysis of growth characteristics between hybrid F1 by Epinephelus moara(♀)×Epinephelus septemfasciatus(♂) and the offspring of their parents. 4: Progress in Fishery Sciences 2015, 36(03), 2015.

- CHEN Z F, TIAN Y S. Embryonic and larval development of a hybrid between kelp grouper Epinephelus moara♀× giant grouper E. lanceolatus♂ using cryopreserved sperm. Aquacult. Res. 1: 2018, 49(4), 2018.

- Lü, Z.; Zhu, K.; Jiang, H.; Lu, X.; Liu, B.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, L.; Liu, L.; Gong, L. Complete mitochondrial genome of Ophichthus brevicaudatus reveals novel gene order and phylogenetic relationships of Anguilliformes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 135, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Huang, G.; Zhang, D.; Guo, Y.; Yu, D. The complete nucleotide sequence of Malabar grouper (Epinephelus malabaricus) mitochondrial genome. Mitochondrial DNA 2014, 27, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KIM Y H, PARK J Y. Complete mitochondrial genome of the hybrid grouper Hyporthodus septemfasciatus (♀)× Epinephelus moara (♂)(Perciformes, Serranidae) and results of a phylogenetic analysis. 7: Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2021, 6(3), 2021.

- Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Cheng, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Pang, Z.; Ma, W.; Zhai, J. The complete mitochondrial genome of the hybrid grouper Epinephelus moara (♀)×Epinephelus tukula (♂), and phylogenetic analysis in subfamily Epinephelinae. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2020, 39, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Gao, Z.; Hu, Z.; Cai, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Liang, R. Comparative characterization and phylogenetic analysis of complete mitogenome of three taxonomic confused groupers and the insight to the novel gene tandem duplication in Epinephelus. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1450003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Qu, M.; Zhang, X.; Ding, S. A Comprehensive Description and Evolutionary Analysis of 22 Grouper (Perciformes, Epinephelidae) Mitochondrial Genomes with Emphasis on Two Novel Genome Organizations. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e73561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Ye, P.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, H.; Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. Comparative Analysis of Four Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Epinephelidae (Perciformes). Genes 2022, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J. Complete Mitochondrial Genome of King Threadfin, Polydactylus macrochir (Günther, 1867): Genome Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis. Genes 2025, 16, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Shih, Y.; Jia, C.; Gao, T. Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Four Peristediidae Fish Species: Genome Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis. Genes 2024, 15, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zou, H.; Wu, S.G.; Li, M.; Jakovlić, I.; Zhang, J.; Chen, R.; Li, W.X.; Wang, G.T. Three new Diplozoidae mitogenomes expose unusual compositional biases within the Monogenea class: implications for phylogenetic studies. BMC Evol. Biol. 2018, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnens, M.; Thijs, S.; Briscoe, A.G.; Clark, M.; Frost, E.J.; Littlewood, D.T.J.; Sewell, M.; Smeets, K.; Artois, T.; Vanhove, M.P. The first mitochondrial genomes of endosymbiotic rhabdocoels illustrate evolutionary relaxation of atp8 and genome plasticity in flatworms. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Ye, Z.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of the hybrid grouper (Cromileptes altivelis♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus♂) with phylogenetic consideration. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2017, 2, 171–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TANG Z, CHEN J. The complete mitochondrial genome of the hybrid grouper Epinephelus coioides♀× Epinephelus akaara♂ with phylogenetic consideration. 3: Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2017, 2(1), 2017.

- LI L, TIAN Y. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of the hybrid grouper (Cromileptes altivelis♀× Epinephelus tukula♂) with phylogenetic consideration. 1: Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2021, 6(3), 2021.

|

Developmental stage |

Developmental stage of embryonic |

Main developmental characteristics |

Time after fertilization |

| One-cell | fertilized egg | Spherical, with one oil ball | 0 |

|

Cleavage |

blastodisc formation stage | The blastoderm has formed, and when viewed from the side, it can be seen that the blastoderm protrudes like a cap | 28min |

| 2-cell stage | The first cleavage forms two cells | 48min | |

| 4-cell stage | The second cleavage forms four cells | 1h10min | |

| 8-cell stage | The third cleavage forms eight cells | 1h27min | |

| 16-cell stage | The fourth cleavage forms 16 cells | 1h43min | |

| 32-cell stage | The fifth cleavage forms 32 cells | 2h03min | |

| 64-cell stage | The sixth cleavage formed 64 cells, and the division surface was rather disordered | 2h24min | |

| Multicellular stage | Continuous division leads to smaller cells and an increase in their number | 2h46min | |

| Morula stage | The cells are piled up in multiple layers, resembling mulberries in appearance | 3h05min | |

| Blastula | high blastula stage | The blastocyst is tall and concentrated, and when viewed from the side, it appears as a high cap | 3h41min |

| low blastula stage | The blastocyst becomes lower, and the cells are preparing to wrap towards the lower pole of the plant | 4h05min | |

| Gastrula | early gastrula stage | One-third of the yolk is encapsulated under the germ layer | 5h53min |

| middle gastrula stage | The embryo layer is subtracted from half of the yolk | 8h29min | |

| late gastrula stage | The embryo layer is subtracted to three-quarters of the yolk, the blastocyst becomes slender, and the embryo body is in the process of formation | 9h49min | |

| Neurula | Embryonic formation stage | The embryonic body is formed with distinct contours | 10h50min |

| Embryonic hole closure stage | The embryo layer is subcapsulated, and the embryo pore is completely closed | 11h32min | |

| Organogenesis | Optic capsule stage | A pair of visual sacs appeared at the head of the embryo | 13h13min |

| Muscle burl stage | Muscle segments appear in the middle of the embryo | 14h30min | |

| Otocyst stage | A pair of auditory sacs appeared at the posterior position of the visual sac in the head | 16h50min | |

| Brain vesicle stage | Brain vesicles appear between the two visual sacs | 18h41min | |

| Heart stage | The heart is formed on the ventral side with a clear outline | 20h25min | |

| Tail-bud stage | The tail of the embryo begins to separate from the yolk sac | 22h57min | |

| Crystal stage | Crystals appear in the eye of the embryo | 23h42min | |

| Heart-beating stage | The heart began to beat slightly and then gradually stabilized | 24h44min | |

| Hatching | Early incubation stage | The embryo is twitching violently | 27h14min |

| Incubation stage | The head emerges from the membrane first | 28h02min | |

| Newly hatched fry | The larvae hatch from the membrane | 28h55min | |

| Incubate for 48h | The yolk sac shrinks and becomes smaller, the notochord becomes more obvious, the dorsal fin folds, the ventral fin folds, and the caudal fin membranes widen, pigmentation begins to form in the eyes, and the mouth can be slightly opened and closed | Total length is 2.35 ± 0.05 mm |

| Gene | Strand | Plectropomus leopardus | Epinephelus fasciatus | E. Fasciatus♀ × P. leopardus♂ | Start_coden | Stop_coden | ||||||

|

Position (Start-End) |

Length(bp) | Intergenic_spacer |

Position (Start-End) |

Length(bp) | Intergenic_spacer |

Position (Start-End) |

Length(bp) | Intergenic_spacer | ||||

| trnF(gaa) | F | 1-69 | 69 | - | 1-70 | 70 | - | 1-70 | 70 | - | - | - |

| rrnS | F | 70-1018 | 949 | 0 | 71-1022 | 952 | 0 | 71-1022 | 952 | 0 | - | - |

| trnV(tac) | F | 1022-1092 | 71 | 3 | 1024-1094 | 71 | 1 | 1024-1094 | 71 | 1 | - | - |

| rrnL | F | 1096-2802 | 1707 | 3 | 1098-2798 | 1701 | 3 | 1098-2798 | 1701 | 3 | - | - |

| trnL2(taa) | F | 2800-2872 | 73 | -3 | 2799-2873 | 75 | 0 | 2799-2873 | 75 | 0 | - | - |

| nad1 | F | 2873-3847 | 975 | 0 | 2874-3848 | 975 | 0 | 2874-3848 | 975 | 0 | ATG/ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA/TAA |

| trnI(gat) | F | 3852-3921 | 70 | 4 | 3853-3922 | 70 | 4 | 3853-3922 | 70 | 4 | - | - |

| trnQ(ttg) | R | 3921-3991 | 71 | -1 | 3922-3992 | 71 | -1 | 3922-3992 | 71 | -1 | - | - |

| trnM(cat) | F | 3992-4060 | 69 | 0 | 3993-4061 | 69 | 0 | 3993-4061 | 69 | 0 | - | - |

| nad2 | F | 4061-5107 | 1047 | 0 | 4062-5108 | 1047 | 0 | 4062-5108 | 1047 | 0 | ATG/ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA/TAA |

| trnW(tca) | F | 5107-5177 | 71 | -1 | 5108-5178 | 71 | -1 | 5108-5178 | 71 | -1 | - | - |

| TrnA(tgc) | R | 5179-5247 | 69 | 1 | 5180-5248 | 69 | 1 | 5180-5248 | 69 | 1 | - | - |

| trnN(gtt) | R | 5249-5321 | 73 | 1 | 5249-5321 | 73 | 0 | 5249-5321 | 73 | 0 | - | - |

| trnC(gca) | R | 5358-5424 | 67 | 36 | 5362-5428 | 67 | 40 | 5362-5428 | 67 | 40 | - | - |

| trnY(gta) | R | 5425-5494 | 70 | 0 | 5429-5499 | 71 | 0 | 5429-5499 | 71 | 0 | - | - |

| cox1 | F | 5496-7046 | 1551 | 1 | 5501-7051 | 1551 | 1 | 5501-7051 | 1551 | 1 | GTG/GTG/GTG | TAA/TAA/TAA |

| trnS2(tga) | R | 7047-7117 | 71 | 0 | 7053-7123 | 71 | 1 | 7053-7123 | 71 | 1 | - | - |

| trnD(gtc) | F | 7120-7193 | 74 | 2 | 7124-7197 | 74 | 0 | 7124-7197 | 74 | 0 | - | - |

| cox2 | F | 7200->7890 | 691 | 6 | 7205->7895 | 691 | 7 | 7205->7895 | 691 | 7 | ATG/ATG/ATG | T/T/T |

| trnK(ttt) | F | 7891-7965 | 75 | 0 | 7896-7968 | 73 | 0 | 7896-7968 | 73 | 0 | - | - |

| atp8 | F | 7967-8134 | 168 | 1 | 7970-8137 | 168 | 1 | 7970-8137 | 168 | 1 | ATG/ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA/TAA |

| atp6 | F | 8188-8808 | 621 | 53 | 8155-8811 | 657 | 17 | 8155-8811 | 657 | 17 | ATG/ATA/ATA | TAA/TAA/TAA |

| cox3 | F | 8808-9593 | 786 | -1 | 8811-9596 | 786 | -1 | 8811-9596 | 786 | -1 | ATG/ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA/TAA |

| trnG(tcc) | F | 9593-9662 | 70 | -1 | 9596-9666 | 71 | -1 | 9596-9666 | 71 | -1 | - | - |

| nad3 | F | 9663-10013 | 351 | 0 | 9667->10015 | 349 | 0 | 9667->10015 | 349 | 0 | ATG/ATG/ATG | TAG/T/T |

| trnR(tcg) | F | 10012-10080 | 69 | -2 | 10016-10084 | 69 | 0 | 10016-10084 | 69 | 0 | - | - |

| nad4l | F | 10081-10377 | 297 | 0 | 10085-10381 | 297 | 0 | 10085-10381 | 297 | 0 | ATG/ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA/TAA |

| nad4 | F | 10371->11751 | 1381 | -7 | 10375->11755 | 1381 | -7 | 10375->11755 | 1381 | -7 | ATG/ATG/ATG | T/T/T |

| trnH(gtg) | F | 11752-11820 | 69 | 0 | 11756-11825 | 70 | 0 | 11756-11825 | 70 | 0 | - | - |

| trnS1(gct) | F | 11821-11898 | 78 | 0 | 11826-11895 | 70 | 0 | 11826-11895 | 70 | 0 | - | - |

| trnL1(tag) | F | 11905-11977 | 73 | 6 | 11911-11983 | 73 | 15 | 11911-11983 | 73 | 15 | - | - |

| nad5 | F | 11978-13816 | 1839 | 0 | 11984-13822 | 1839 | 0 | 11984-13822 | 1839 | 0 | ATG/ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA/TAA |

| nad6 | R | 13813-14334 | 522 | -4 | 13819-14340 | 522 | -4 | 13819-14340 | 522 | -4 | ATG/ATG/ATG | TAG/TAA/TAA |

| trnE(ttc) | R | 14335-14403 | 69 | 0 | 14341-14409 | 69 | 0 | 14341-14409 | 69 | 0 | - | - |

| cob | F | 14406->15546 | 1141 | 2 | 14417->15557 | 1141 | 7 | 14417->15557 | 1141 | 7 | ATG/ATG/ATG | T/T/T |

| trnT(tgt) | F | 15547-15618 | 72 | 0 | 15558-15630 | 73 | 0 | 15558-15630 | 73 | 0 | - | - |

| trnP(tgg) | R | 15618-15688 | 71 | -1 | 15630-15699 | 70 | -1 | 15630-15699 | 70 | -1 | - | - |

| Species | Region | Length(bp) | T% | C% | A% | G% | AT% | GC% |

| Plectropomus leopardus | Genome | 16753 | 27.92 | 26.75 | 29.11 | 16.22 | 57.03 | 42.97 |

| Protein_coding_genes | 11370 | 30.30 | 27.86 | 26.40 | 15.44 | 56.70 | 43.30 | |

| First position | 3790 | 28.71 | 28.23 | 26.70 | 16.36 | 55.41 | 44.59 | |

| Second position | 3790 | 31.58 | 28.39 | 24.85 | 15.17 | 56.44 | 43.56 | |

| Third position | 3790 | 30.61 | 26.97 | 27.65 | 14.78 | 58.26 | 41.74 | |

| tRNA | 1564 | 27.69 | 20.65 | 28.32 | 23.34 | 56.01 | 43.99 | |

| rRNA | 2656 | 22.06 | 23.43 | 33.43 | 20.97 | 55.50 | 44.50 | |

| Epinephelus fasciatus | Genome | 16570 | 26.81 | 28.32 | 28.73 | 16.14 | 55.55 | 44.45 |

| Protein_coding_genes | 11404 | 28.64 | 29.69 | 26.25 | 15.42 | 54.88 | 45.12 | |

| First position | 3801 | 24.49 | 26.99 | 26.57 | 21.94 | 51.06 | 48.93 | |

| Second position | 3801 | 33.88 | 29.83 | 21.91 | 14.36 | 55.8 | 44.2 | |

| Third position | 3801 | 27.52 | 32.25 | 30.25 | 9.97 | 57.77 | 42.22 | |

| tRNA | 1560 | 27.44 | 20.96 | 28.97 | 22.63 | 56.41 | 43.59 | |

| rRNA | 2653 | 21.56 | 25.52 | 32.42 | 20.51 | 53.98 | 46.02 | |

| E.fasciatus ♀ × P.leopardus ♂ | Genome | 16570 | 26.82 | 28.32 | 28.73 | 16.13 | 55.55 | 44.45 |

| Protein_coding_genes | 11404 | 28.65 | 29.68 | 26.25 | 15.42 | 54.89 | 45.11 | |

| First position | 3801 | 24.52 | 26.96 | 26.6 | 21.91 | 51.11 | 48.88 | |

| Second position | 3801 | 33.83 | 29.88 | 21.91 | 14.36 | 55.74 | 44.25 | |

| Third position | 3801 | 27.57 | 32.2 | 30.23 | 10 | 57.8 | 42.2 | |

| tRNA | 1560 | 27.44 | 20.96 | 28.97 | 22.63 | 56.41 | 43.59 | |

| rRNA | 2653 | 21.56 | 25.52 | 32.42 | 20.51 | 53.98 | 46.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).