1. Introduction

Vietnam, a developing nation with a middle-income economy, faces challenges in its tertiary education system, including limited capacity, uneven quality, and a misalignment between graduate skills and market demands [

1]. With an enrolment rate of 30-35%, smaller institutions lag behind due to outdated curricula and resource constraints [

1]. This study focuses on South and South-central Vietnam, regions central to the country’s aquaculture industry, which collectively accounts for ~90% of Vietnam's aquaculture production area [

2]. Despite being the world’s fifth-largest producer of farmed fish and the third-largest seafood exporter [

3], Vietnam performs poorly in animal welfare legislation, earning an "F" grade on the World Animal Protection's global index [

4]. Despite the presence of legislation to support animal welfare, penalties are kept low since the goal serves to only raise awareness of animal cruelty [

4]. While some progress has been made, the lack of enforcement mechanisms, species-specific guidelines, and alignment with the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) (2024) standards leaves significant room for improvement. In Vietnam AAW remains an underexplored concept, with concerns such as high stocking densities, poor handling and transport practices, farmer inexperience or suboptimal training concerning AAW, animals sold live at wet markets in poor welfare conditions, and inconsistent environmental monitoring prevalent in Vietnamese aquaculture [

4]. Our ethical and moral responsibility is to ensure animal welfare is because animals including aquatic animals are sentient [

5] and are therefore capable of experiencing pain and suffering.

The treatment of animals, particularly in developing nations, is influenced by socio-economic, cultural, and religious factors [

6]. Limited resources, high cost of living, political priorities, and food insecurity often lead to deprioritisation of animal welfare improvements unless tied to economic benefits [

7]. This is significant for countries in Africa and Asia, where agriculture and livestock farming serve a key economic role, where animals are often valued largely for their contributions to human well-being [

8]. By understanding such perceptions towards AAW, misconceptions or knowledge deficits that may hinder the adoption of welfare practices can be identified, and targeted interventions employed. Understanding these perceptions is critical, as they directly impact our behaviour and motivations [

9], and therefore the execution of welfare-friendly practices. Sinclair, Lee [

10] reported that the treatment of animals is influenced more by societal perceptions and the importance placed on their welfare, compared to scientific understanding of it. Cultural factors, shaped from a young age, provide a framework for processing information [

11] and play a significant role in socio-cultural perceptions of animal welfare, which should be considered before implementing international welfare programs [

12]. Personal experiences, values, interests and convictions also influence public perceptions [

13], alongside demographic factors such as gender and age [

14,

15]. Research consistently finds that females tend to have higher pro-animal welfare attitudes than males, influenced by factors like human-animal interactions [

14,

16] and childhood experiences with companion animals [

17]. Younger individuals often exhibit more favorable attitudes towards animal welfare, as seen in China, where the younger generation demonstrates greater awareness and concern than older adults [

18], likely due to improved education and cultural shifts [

19].

Religious beliefs were reported to also affect animal welfare attitudes, with some studies indicating reduced concern for welfare among individuals with stronger religious values Serpell [

6], Deemer and Lobao [

20]. However, geographic and cultural factors show a stronger correlation with attitudes than religion [

21]. The moulding of attitudes, beliefs, and values through education underscores the importance of including aquatic animal welfare content in curricula [

22,

23]. Vietnamese employers have expressed concern over the skill gaps of university graduates in relation to market requirements [

24], which underscores the need to assess any AAW education gap to ensure graduates are equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary to implement welfare standards, meet industry expectations, and contribute to sustainable and ethical aquaculture practices.

Despite the critical role of aquatic animals in Vietnam's aquaculture economy, research on perceptions and education concerning AAW among students and educators at tertiary institutions, and industry professionals is lacking. This exploratory study is the first to address this gap, in addition to evaluating whether an AAW education gap at the undergraduate level negatively impacts students' perceptions towards AAW (hypothesis). The findings aim to provide a model for other countries facing similar challenges, contributing to global efforts to advance AAW and promote the responsible use and stewardship of aquatic animals. Identifying perceptions and educational gaps also provide a basis for advocating policy reforms, curriculum reform, institutional changes that will prioritise AAW in Vietnam and help align its aquaculture practices with international welfare standards. Although the authors recognise the importance of animal welfare to all animals, aquatic animal welfare is the focus of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

The geographical scope of this project spanned South and South-Central Vietnam, encompassing key academic and vocational institutions across multiple provinces in the Mekong Delta and coastal regions. These included Bạc Liêu College of Economics and Technology and Bạc Liêu University (Bạc Liêu Province); Cà Mau Community College (Cà Mau Province); Đồng Tháp Community College (Đồng Tháp Province); Sóc Trăng Vocational College (Sóc Trăng Province); Southern Agricultural College (Hậu Giang Province); Trà Vinh University (Trà Vinh Province); and Cần Thơ University (Cần Thơ City) in the Mekong Delta. It also included Ho Chi Minh City University of Agriculture and Forestry (Ho Chi Minh City, South East) and Nha Trang University (Khánh Hòa Province, South Central Coast). Together, these institutions provide broad coverage of the region’s educational landscape in aquaculture.

Survey design and implementation: a mixed methods survey was administered to a target population of 2,048 students and 164 educators across ten universities and eight colleges in Vietnam, with priority given to institutions offering aquatic animal or aquaculture-related programmes (

Figure 1). Digital surveys (via Google Survey) were used for students, and telephonic interviews were conducted with educators and stakeholders. Interview data were digitally recorded, with procedural consistency maintained by the TVU team. Questionnaires were validated by five TVU members using face and content validation methods [

25]. A pilot study involving seven participants (students, educators, and aquaculture sector stakeholders) assessed clarity, translation accuracy, and cultural alignment. Refinements were made accordingly. Internal reliability, assessed using McDonald’s omega in R Studio, showed acceptable values: 0.71 (students), 0.70 (educators), and 0.84 (aquaculture sector stakeholders) [

26].

Sampling strategy: A weighted, stratified random sampling approach [

27] was employed for students, with educator samples proportionate to institutional student numbers (

Table 1) from the target population. Stakeholders of aquaculture sector were selected via convenience sampling within the TVU network. The study included five universities and five colleges. Students (n=359) were randomly selected through hierarchical sampling at institutional, major, and academic year mid-program and final-year students) levels using a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. Educators (n=47) were randomly selected based on institutional ratios (one educator per 50 students at universities and one per 20 students at colleges) and involvement in aquatic animal-related curricula. Aquaculture sector stakeholders (n=34) represented commercial enterprises, government agencies, and research institutions.

Survey instruments and variables: variables influencing AAW perception were grouped by respondent type. The variables investigated in this study included gender, age, religion, nationality, household income, views on Vietnamese culture, and seafood consumption, which were collected across all respondent groups. In addition, specific variables were considered for each group. For educators, these included professional rank, highest qualification, and duration of teaching. For students, additional variables included major studies, academic year, other tertiary education background, planned future job or role, and whether AAW education would influence this. No additional variables were collected for aquaculture sector stakeholders beyond those common across groups. Survey instruments included 29 questions for students, 26 for educators, and 25 for stakeholders of aquaculture industry.

These covered demographic details, AAW perspectives, and relevant curriculum content and educational gaps. A combination of Likert-scale, multiple-choice, binary, matrix, open- and close-ended formats were used. Welfare scoring: perceptions of AAW were evaluated using ten tailored questions, whilst their understanding of what AAW meant were scored based on: the recognition of human concern, humane treatment, and ethics; legal responsibilities concerning regulations and rights for aquatic animals; the Five Freedoms [

28]; and application across diverse interactions with aquatic animals.

Perception scores: these were categorised from low to very high and reflected knowledge, attitudes, and ethical awareness towards AAW. Students answered seven questions which included assessing: their perceived importance of animal welfare in Vietnamese culture and society; their opinion on which aspects contribute to good AAW; their opinion on where animal welfare is an important feature when farming aquatic animals; their preference on paying for a higher welfare product and the percentage mark-up they are willing to pay; their opinion on what AAW is an important consideration for; and how important learning about AAW is concerning their academic and professional interests. Educators and aquaculture sector stakeholders answered the same first five questions as students. Educators additionally answered on their perceived importance of AAW inclusion for learners in aquaculture and animal health professions; and aquaculture sector stakeholders answered on the perceived importance of AAW and its application to relevant industries for students, in addition to their willingness to support tertiary institutions to enrich the learners’ experience.

Education gap scoring: four aspects of student perceptions of educational adequacy were assessed, including confidence in discussing AAW, curriculum sufficiency, satisfaction with materials, and teaching quality. A 40-point scale categorised education gaps from very low to high (

Table 2), with higher scores indicating greater perceived deficits.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in R Studio (version 4.1.3). Normality and homogeneity were tested using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Kendall-Theil Sen, Welch’s ANOVA, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied, with Bonferroni post hoc corrections where relevant. Results were reported as mean ± 1SD. Perception and education gap scores were standardised to a 100-point scale. Significance was defined at p < 0.05. Weighted sampling combined with robust statistical methods ensured results were representative and valid despite unequal sample sizes and variances.

Dependent variables included perception and education gap scores. Key independent variables were academic major and year, were analysed using Welch’s ANOVA to address unequal sample sizes. Other potential explanatory variables evaluated included: gender, age, household income, religion, professional rank, highest educator qualification, teaching experience, seafood consumption, and welfare product mark-ups were independently assessed using Welch’s ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests, with ANCOVA applied to assess interaction effects.

3. Results

3.1. General Information of Demographics of Survey Participants

Table 3 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the survey participants, including gender, age, religion, monthly income, and teaching experience. Among participants the majority were male (55.2%), whilst 43.9% were female and < 1% of participants preferred not to disclose their gender. The results show that among the students (n = 359), the majority were between 18–21 years old (61.6%), followed by 22–25 years old (37.3%), while very few were in the older age groups. Most student respondents identified as non-religious (66.0%), with 24.0 % identifying as Buddhist and smaller proportions identifying as Catholic (4.26%) or other religions (5.85%). In terms of income, most students reported a monthly income of less than 10 million VND (69.9%), with decreasing proportions in the higher income brackets.

The largest proportion of educators (66.0%) was between 36–45 years old, followed by those aged 46–55 years (29.8%). Most educators also identified as non-religious (76.6%), and the majority had over 15 years of teaching experience (63.8%). Monthly income varied, with the largest group (61.7%) earning about 10–20 million VND, and smaller proportions in the higher income brackets (

Table 4). For stakeholders (n = 34) in the aquaculture industry, 55.9% were aged 36–45, followed by 23.5% aged 25–35, and 11.8% aged 46–55. Like the other groups, the majority (70.6%) reported no religious affiliation. Income distribution was broader compared to educators and students, with 32.4% earning 10–20 million VND, 23.5% earning 20–30 million, and 20.6% above 30 million (

Table 3).

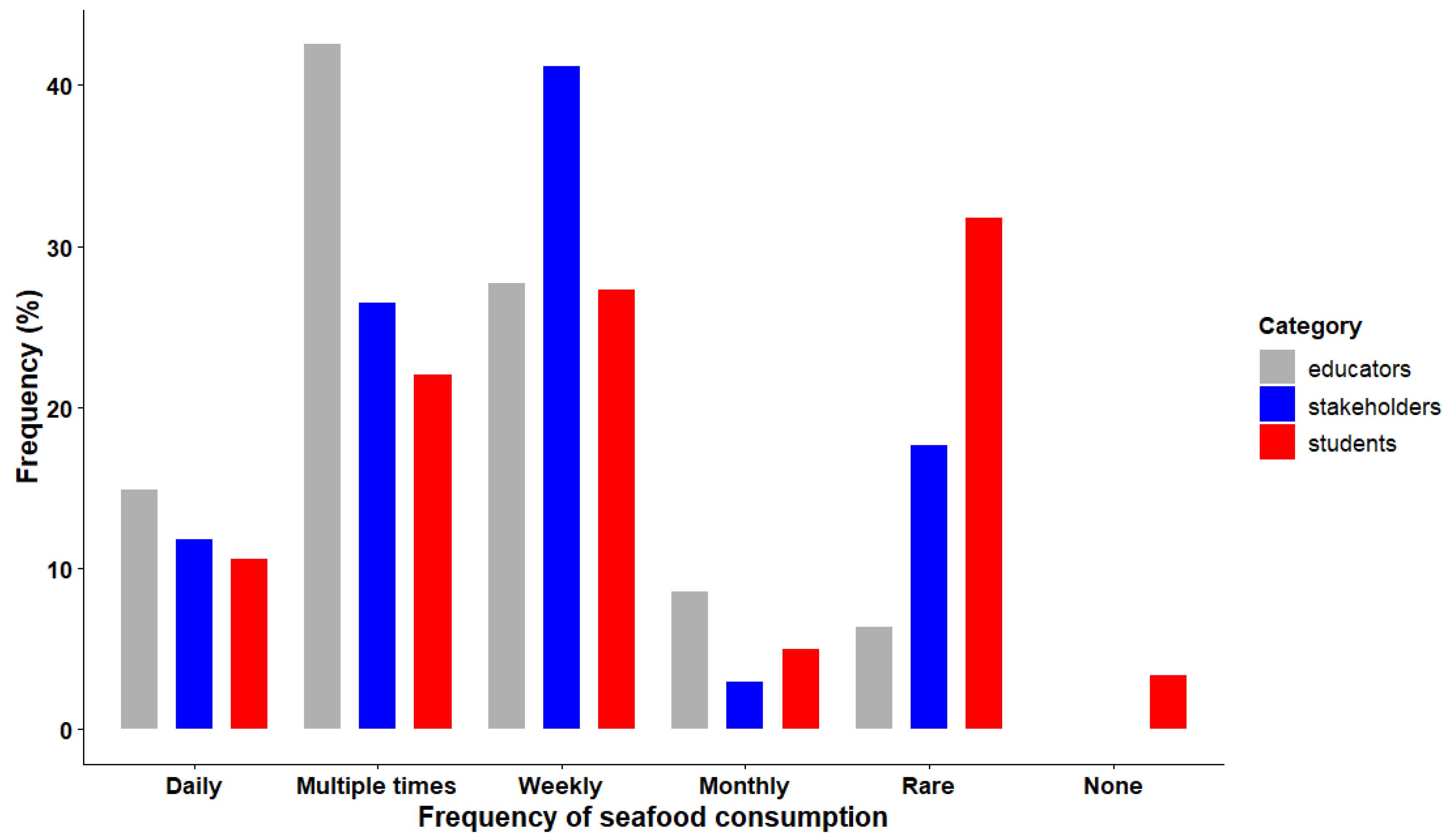

Figure 2 illustrates the frequency of seafood consumption among students, educators, and aquaculture sector stakeholders. Most educators consumed seafood multiple times per week (over 40%), followed by weekly (approximately 30%), indicating high consumption rates. Among stakeholders of aquaculture industry, seafood consumption was primarily weekly (42%) and multiple times per week (25%). In contrast, students reported lower seafood intake, with the majority consuming seafood on a weekly (29%) or rare (33%) basis. Very few participants reported daily or no seafood consumption.

3.2. Students’ Perspectives on Aquatic Animal Welfare (AAW)

Among students, 98.1% had no prior tertiary education. Career aspirations were varied but did not reference AAW. A majority 89.7 reported a positive perception of AAW education's impact on career opportunities, citing benefits such as enhanced employment prospects and contributions to conservation, sustainability support for welfare policy and research. Most students (68.0%) regarded current AAW curriculum inclusion as adequate, while only 6.13% reported dissatisfaction. Remaining students were unsure (5.85%) were indifferent (1.39%) or did not answer because they did not study it yet (18.7%).

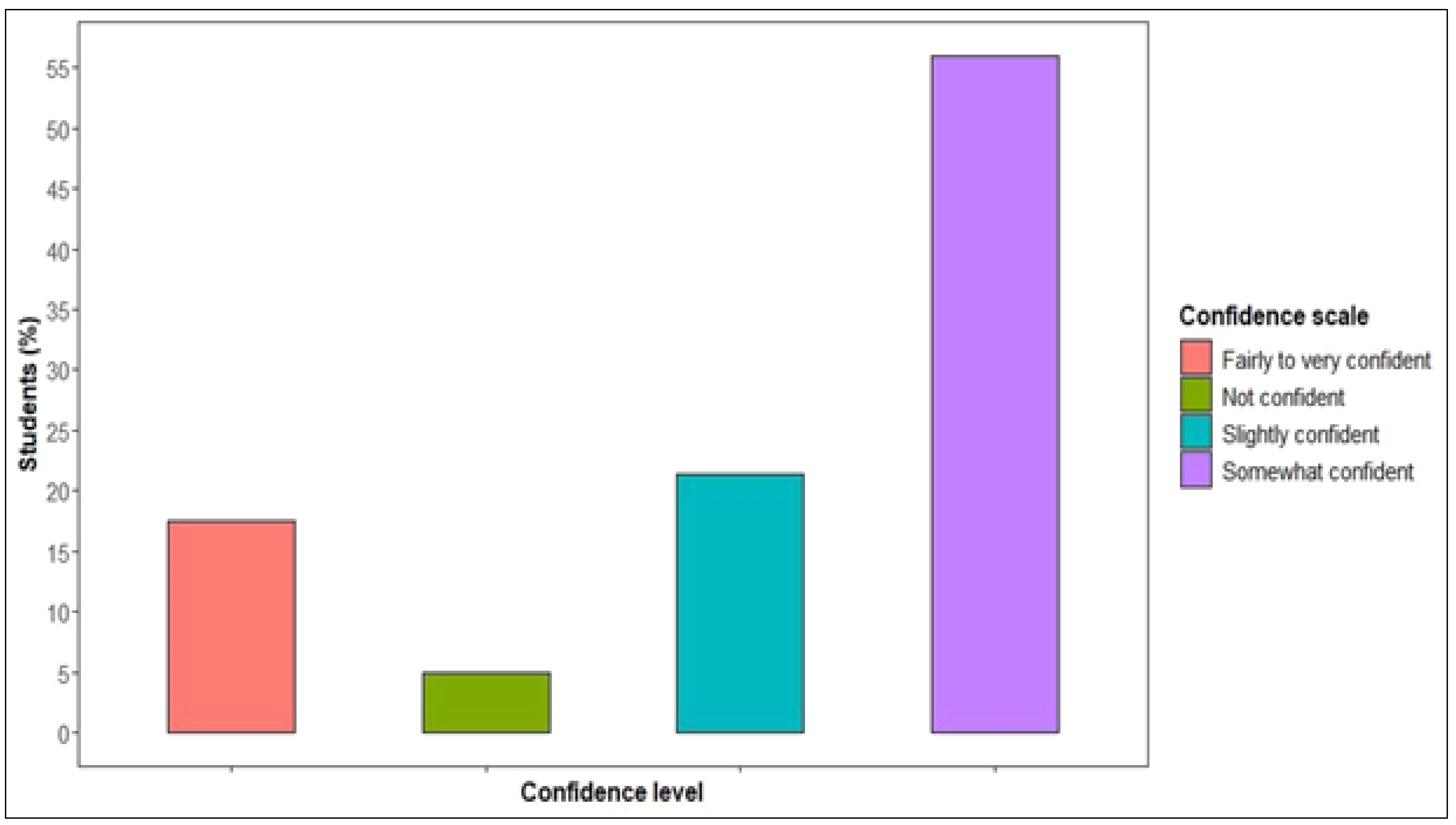

Only 34.6% of student responses reflected the desire for improved AAW content (with some students expressing more than one recommendation). Satisfaction with learning resources and learning experience was generally high, with 37.1% being “very satisfied” and 40.7% being “relatively satisfied”. Similarly, 48.2% were “very satisfied” with AAW teaching quality, communication skills, student support, and knowledge on AAW at respective institutions, whilst 31.8% were “relatively satisfied”. However, only 17.6% expressed high confidence (“fairly to very confident”) in discussing AAW topics, with an average confidence score of 63.7% (

Figure 3).

Regarding student perspectives on recommended curriculum changes related to AAW, the results showed that nearly half of the respondents (47.6%) believed that no changes were needed, while a substantial proportion supported curriculum enhancement, including increased inclusion of AAW topics (12.5%), and a larger practical component (12.8%). Smaller proportions suggested the need for specific improvement recommendations (5.59%) and more in-depth information (3.72%). A notable portion (6.91%) reported no comment due to lack of prior exposure to AAW content, whilst 8.51% listed “other” reasons or “did not know” (2.39%). Preferences varied across institutions, with a general emphasis on experiential learning and theoretical-practical alignment (

Table 4).

3.3. Students’ Perspectives on Aquatic Animal Welfare (AAW)

Among the educators surveyed, satisfaction with inclusion of AAW within tertiary curricula was found to be variable. At institutions where AAW was incorporated, 23.4% reported its integration across various aquaculture-related subjects, rather than as a standalone course. Regarding satisfaction with how AAW was incorporated into the curriculum, 27.7% of educators were unsure and 31.9% were not satisfied. Only a small proportion (4.26%) expressed satisfaction with AAW content across all programs, while 36.2% were satisfied with its inclusion limited to certain programs.

A total of 19.2% confirmed that AAW was already included in their institution’s curriculum, 46.8% reported that inclusion was not yet implemented but was planned, 19.2% were unsure, whilst 14.9% reported that AAW was not included, with no plans for its future integration. Nearly half (48.9%) either did not respond or provided responses deemed inappropriate. With respect to future integration, 51.1% recommended incorporating AAW into existing modules, while only 2.13% suggested establishing a new subject. A notable proportion either did not provide specific answers (19.2%), were unsure (27.7%), or were unable to specify changes due to the current exclusion of AAW in their curricula (6.38%). Educators proposed several strategies for improving AAW instruction, the most frequent recommendation (27.7%) being the development of dedicated curriculum content (

Table 5). Anticipated challenges to curriculum reform were also identified, with the most frequently cited barriers being related to curriculum structure and educational alignment (21.3%) and limited awareness or understanding of AAW (19.2%) (

Table 6).

3.4. Aquaculture Sector Stakeholder’s Perspective on Aquatic Animal Welfare (AAW)

Stakeholders (70.6%) reported that graduates were able to identify AAW issues, however reasons for such confidence were not always clear amongst 41.2% of this group. For those who provided reasons, confidence was attributed to various factors: (1) observations of employees during their duties; (2) selection of aquatic feed by employees; (3) verbal interactions and information exchanges; (4) review of curriculum vitae during recruitment; (5) annual examinations; (6) employees’ seafood consumption choices; (7) adherence to company animal welfare protocols; (8) periodic evaluations of employees' handling of AAW issues; (9) training gained through academic programs, company-led initiatives, or self-study.

Aquaculture sector groups identified several key areas where graduates could contribute greater value to the aquaculture sector in South and South-Central Vietnam. Aquaculture emerged as the most frequently cited area (21.4%), reflecting the sector’s strong demand for skilled personnel in production and technological applications. Other notable areas included welfare research (17.6%), policy and legislation development (12.2%), industry relevant practices (13.7%) and conservation (16.0%), indicating increasing attention to sustainability and ethical practices in aquatic resource management. Public awareness and advocacy (15.3%) were also emphasised, suggesting a need for improved communication and stakeholder engagement. Lower response frequencies for industry practices (13.7%) and policy and legislation development (12.2%) may reflect existing capacities or lower perceived gaps. These results highlight the importance of aligning academic programs with practical aquaculture competencies, while integrating cross-cutting themes such as welfare, conservation, and public engagement to enhance graduate preparedness and sectoral impact. Regarding the support aquaculture industry stakeholders are prepared to offer to enhance student learning in AAW, paid internships (0–6 months) received the highest level of support (32.6%), followed by short-term practical exposure integrated into elective modules (28.3%). Aquaculture sector stakeholders recognised the value of practical demonstrations by academics and supported the use of their facilities for this purpose (19.6%). In contrast, less than 19.6% of stakeholders supported the use of their facilities for research (15.2%) or unpaid internships (4.35%). indicating strong commitment to hands-on, experiential training. Additionally, the use of facilities for academic demonstration (19.6%) and student-led research (15.2%) underscores opportunities for academic-industry collaboration. Unpaid internships were the least supported (4.35%), possibly due to concerns about equity and effectiveness. These findings emphasize the need to promote structured, practice-oriented learning experiences that foster both academic and professional development in the aquaculture and aquatic welfare domains.

3.5. Understanding of Fish Welfare Among Survey Respondents

Respondents' understanding of fish welfare varied notably across the surveyed groups. Although 53.8% of students indicated familiarity with the concept of the Five Freedoms of Animal Welfare, only 5.57% were able to accurately list all five freedoms. Among the three groups, aquaculture sector stakeholders demonstrated the lowest level of conceptual understanding, with a correct response rate of 21.3%, followed by students (29.4%) and educators (32.5%). Standardised perception scores (on a 100-point scale) were highest among aquaculture sector stakeholders (73.3%), slightly ahead of students (69.2%) and educators (68.9%). A detailed breakdown of respondents’ recognition of specific welfare-related aspects is presented in

Table 7, while

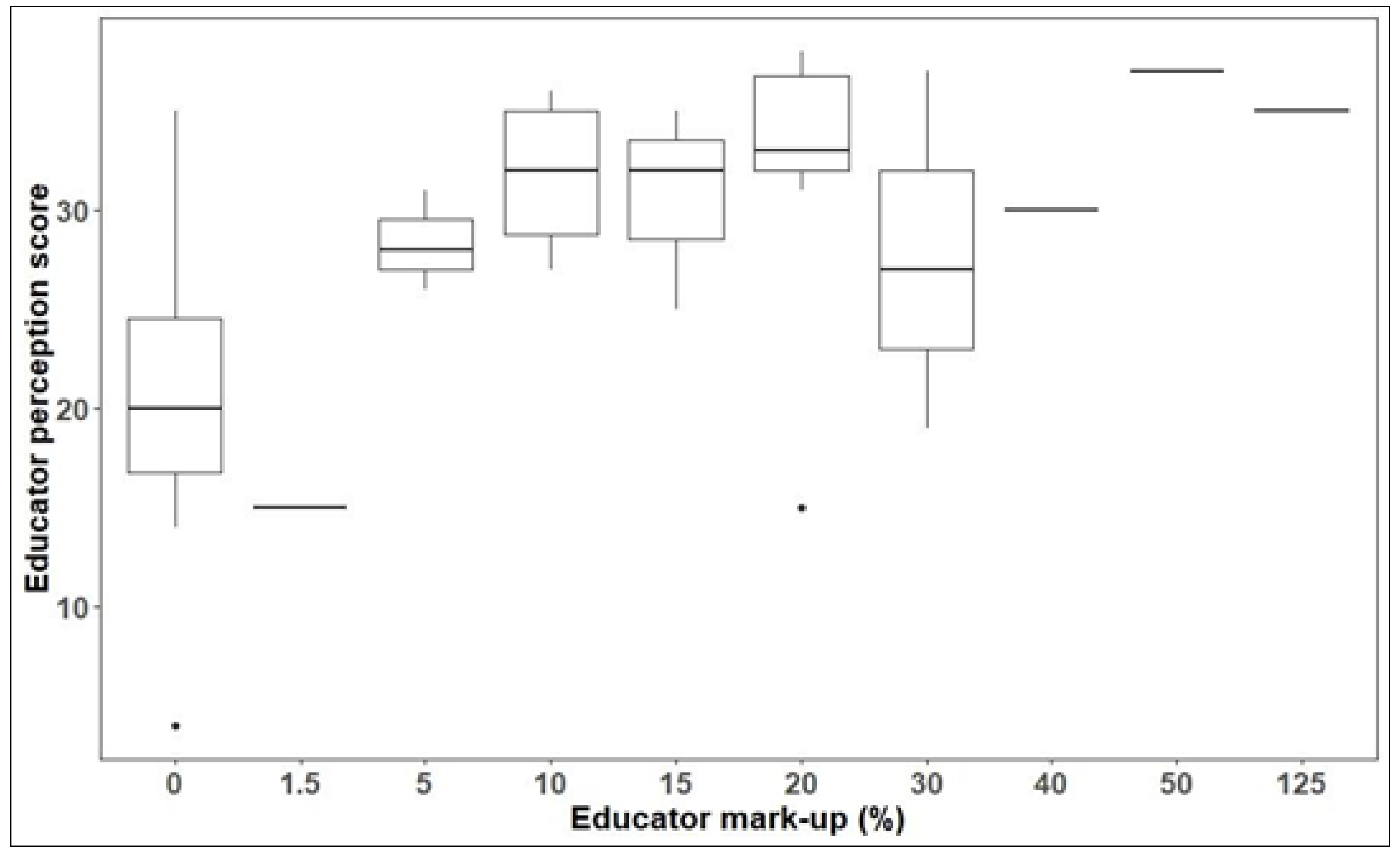

Table 8 provides a comparative summary of average perception scores across the three respondent categories. Regarding consumer behavior, the most accepted premium for higher-welfare aquatic products fell within the 6–10% range. Notably, significant positive correlations (p < 0.05) were found between perception scores and willingness to pay among both educators and students, as illustrated in

Figure 4 and

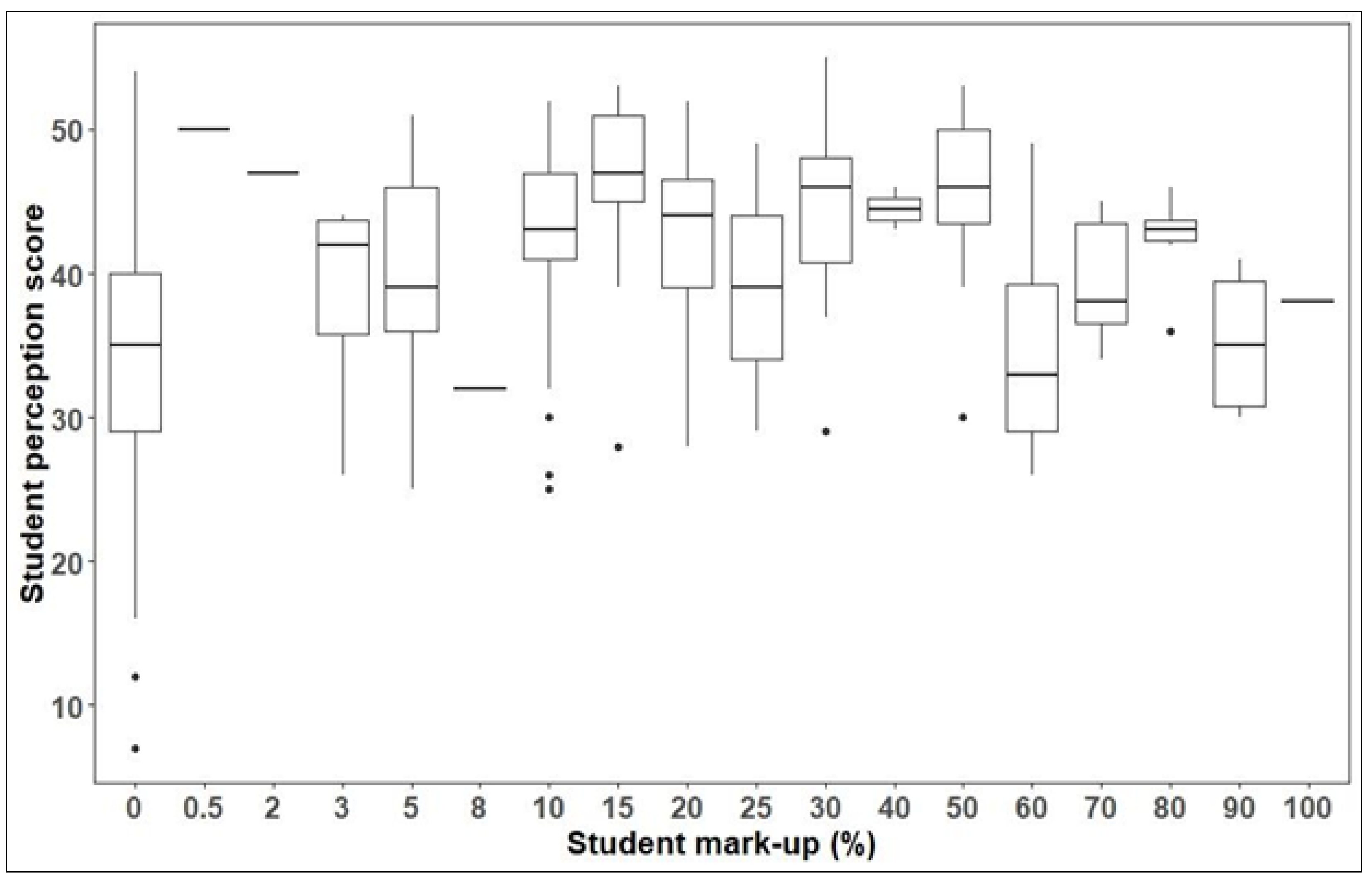

Figure 5.

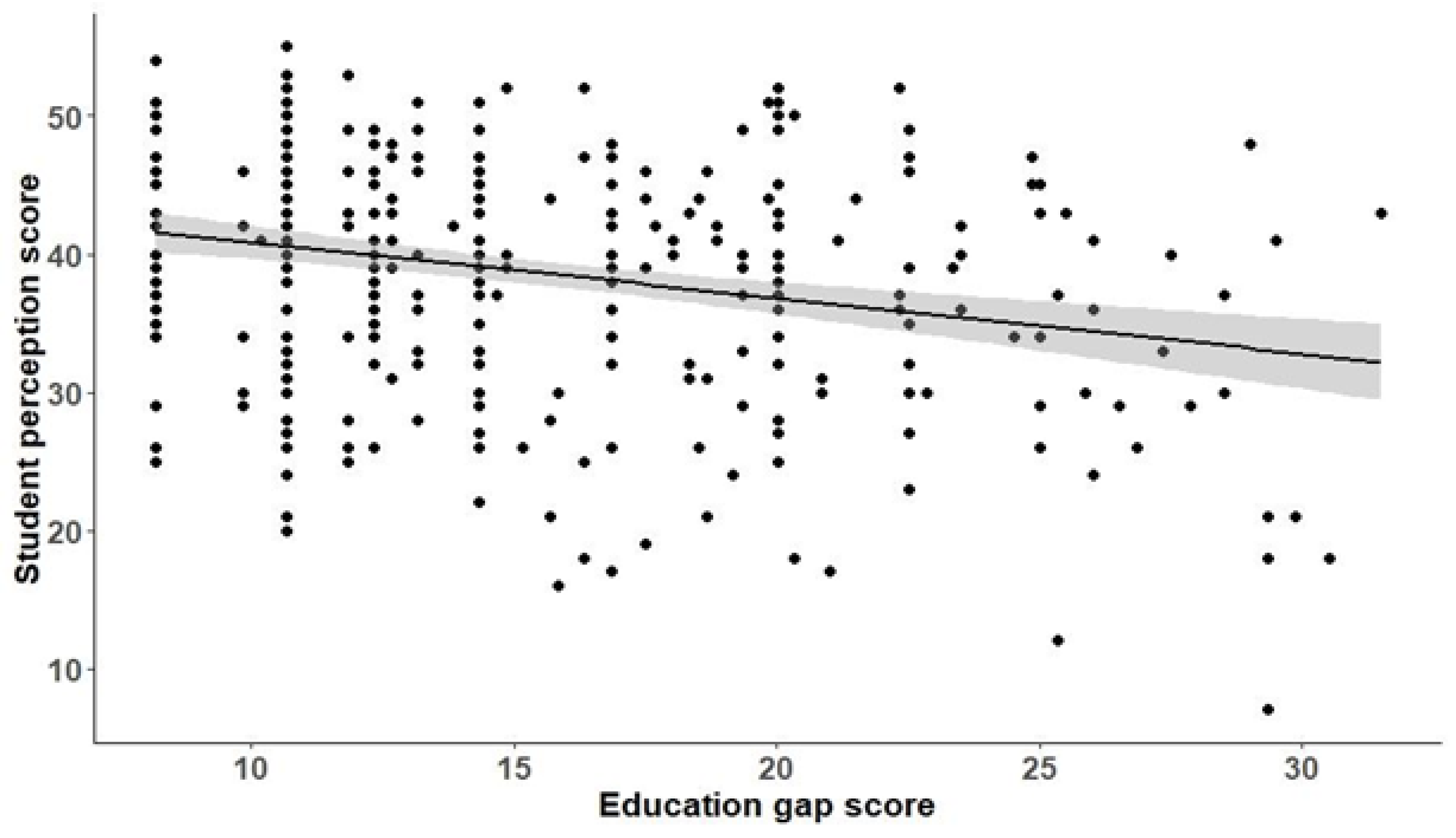

Additionally, a small but statistically significant inverse relationship was observed between students' perception scores, and their education gap scores (slope = -0.28; p = 1.25×10−12), as shown in

Figure 6. However, no significant differences in education gap scores were identified based on institution, major, or academic year (p > 0.05). Most students (74.9%) exhibited low education gap scores, whereas only a small fraction (0.56%) was classified as having high education gaps (

Table 8).

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Key Research Findings on Perceptions of Aquatic Animal Welfare (AAW)

This exploratory study offers the first empirical evidence on perceptions of AAW and associated educational gaps among students, educators, and key aquaculture sector stakeholders in South and South-Central Vietnam. Survey results revealed consistently high perception scores across all respondent groups, with 87.8% of students, 94.1% of aquaculture sector stakeholders, and 80.9% of educators rating AAW as either "important" or "very important." These findings reflect a generally favorable attitude toward the welfare of aquatic animals among those involved in the education and aquaculture sectors. However, a closer examination of student responses revealed a significant gap between general awareness and depth of understanding. While 53.8% of students reported recognizing most or all components of the Five Freedoms of Animal Welfare, a globally accepted framework for assessing animal welfare [

29] only a small fraction could accurately articulate them. Notably, 17.0% of students demonstrated no conceptual understanding of animal welfare principles. This "awareness depth gap" mirrors findings from previous studies suggesting that positive perceptions of animal welfare do not necessarily translate into practical knowledge or ethical decision-making capabilities [

7,

30,

31]. Such gaps underscore a pressing need for curriculum reform in aquatic/aquaculture and animal sciences education in Vietnam. Moving beyond surface-level awareness, educational programs should incorporate structured, experiential, and applied learning modules that foster deeper comprehension of welfare science, ethics, and practice. As suggested by Deemer and Lobao [

20], integrating real-world case studies, hands-on husbandry practices, and critical thinking exercises can help bridge the gap between normative attitudes and functional knowledge.

No statistically significant differences in AAW perception scores were observed across academic majors or year levels, suggesting a consistent pattern of understanding among students regardless of disciplinary background or academic progression. This uniformity likely reflects the limited integration of structured AAW content within existing curricula across programs. These findings highlight the importance of adopting a progressive, tiered approach to AAW education one that builds conceptual depth and applied understanding throughout the academic trajectory. While cultural familiarity and informal learning may contribute to a baseline awareness of animal welfare principles [

32,

33], the frequency of aquatic animal consumption showed no significant relationship with perception scores among respondents (

Figure 2). This suggests that positive attitudes toward animal welfare may coexist with habitual consumption behaviors, potentially influenced by cultural norms, dietary preferences, or economic practicality. Such inconsistencies between belief and behavior may be explained through the lens of cognitive dissonance theory, wherein individuals reconcile ethical concerns with existing practices [

34].

A strong majority of students (89.7%) expressed the belief that education in AAW could enhance their future career opportunities, indicating a high level of awareness regarding the relevance of welfare knowledge within the aquaculture sectors. This perception aligns with global trends recognizing animal welfare as an increasingly important dimension of sustainable aquaculture, particularly in countries engaged in international trade and export-oriented production [

35]. Among all respondent groups, the Five Freedoms of Animal Welfare emerged as the most frequently cited welfare framework especially among students (53.8%) highlighting its role as the most familiar and accessible entry point for AAW education (

Table 7). In contrast, legal obligations related to animal welfare were the least referenced, particularly among aquaculture stakeholders (3.45%), suggesting limited awareness of regulatory dimensions within the industry. This may be attributed to the absence of comprehensive animal welfare legislation applicable to aquaculture in Vietnam [

4,

36]. Furthermore, the relatively low proportion of respondents acknowledging the role of welfare in diverse aspects of animal use such as farming, transport, and handling was notable across all groups (14.8% among educators, 7.52% among students, and 17.2% among aquaculture industry stakeholders). These findings underscore the need for enhanced integration of practical animal welfare considerations into both academic curricula and professional training programs, to build competence in welfare-related decision-making and practice across the aquaculture value chain.

4.2. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Higher Fish Welfare Standards

Higher AAW perception scores among both educators (Fig. 4) and students (Fig. 5) were positively associated with a greater willingness to pay (WTP) a premium for welfare-friendly aquaculture products. This trend suggests a shared understanding among educators that higher welfare standards justify increased consumer costs, reflecting the influence of professional knowledge on ethical purchasing decisions. Similarly, students demonstrated an upward shift in median perception scores from approximately 30 at a 0% mark-up to the high 30s to mid-40s at a 5–15% mark-up. However, beyond the 30% premium threshold, perception scores showed no consistent trend, indicating a diminishing correlation between WTP and AAW perception at higher price points. These findings imply that a higher level of welfare awareness and understanding can enhance consumers' willingness to support ethical production practices through market behavior, a trend also observed in other studies linking welfare knowledge to WTP [

14,

37,

38]. In contrast, no significant association was observed between aquaculture stakeholders’ perception scores and their willingness to pay, suggesting that practical or economic constraints in industry contexts may override welfare considerations.

Notably, the most accepted price premium among all respondents fell within the 6–10% range, supporting previous research identifying moderate price mark-ups as optimal for consumer acceptance of welfare-certified products [

39,

40]. This range should be considered a practical recommendation for marketing welfare-friendly aquaculture products in emerging markets like Vietnam. Although the statistically significant association between perception scores and WTP reinforces the value of welfare education in influencing consumer behavior, the non-linear relationship highlights that perception alone is not a sufficient predictor of payment willingness. This underscores the need for integrated consumer engagement strategies that combine welfare awareness with economic, cultural, and social considerations. As a behavioral indicator, WTP remains a valid proxy for market demand and further supports the integration of animal welfare education into public outreach and policy initiatives in aquaculture development.

4.3. The Education Gap and Its Influence on Perceptions of Aquaculture Animal Welfare

A small but statistically significant negative association was observed between student perception scores and education gap scores (Kendall–Theil Sen slope = –0.28, p = 1.25 × 10⁻¹²) (Fig. 6), supporting the central hypothesis that deficiencies in AAW education are linked to lower perception levels. Specifically, students from institutions with greater curricular inclusion of AAW concepts tended to report higher perception scores, reinforcing the critical role of formal education in shaping awareness, ethical sensitivity, and welfare-related attitudes. These findings are consistent with previous studies emphasizing the influence of educational exposure on animal welfare perceptions [

22]. The average education gap score was 15.3 ± 5.4, with the majority of students falling within the moderate range (11–20), and only 0.56% categorized as having a “high” education gap. These results suggest that while most students felt reasonably confident in their knowledge, uncertainty persists regarding the extent and depth of AAW content in their curricula. The considerable variability around the trend line further indicates that, although curriculum depth is a significant determinant of student perceptions as also reported by Sinclair, Lee [

10], Mijares, Sullivan [

22], other factors, such as informal learning, cultural background, and personal values, likely contribute to shaping student attitudes toward animal welfare. This highlights the need for a more comprehensive and multi-dimensional educational approach that incorporates both formal instruction and experiential learning opportunities.

The cluster of students categorized as having a “low” education gap represents a promising target group for curriculum enhancement initiatives, as modest improvements could shift many into the “very low” gap category. Notably, the threshold between a gap score of 20 (low) and 21 (moderate) marks a conceptual transition from "some uncertainty" to "active dissatisfaction" regarding curriculum coverage. This suggests that a score of 20 may serve as an early-warning indicator, prompting timely interventions such as remedial sessions or the provision of supplemental materials. The scatterplot analysis further demonstrates a general trend: as education gap scores increase indicating greater perceived deficiencies in AAW instruction, student perception scores tend to decrease. While this inverse relationship suggests that perceived curricular shortcomings are associated with weaker welfare perceptions, the relatively modest effect size indicates that other influences, such as informal learning, cultural background, and personal values, also play a substantial role in shaping attitudes. These findings are consistent with prior research emphasizing the multi-dimensional nature of welfare perception formation [

12,

41,

42].

Importantly, the absence of significant differences in education gaps scores across academic institutions, disciplines, or year levels points to a systemic shortfall in AAW education. This finding underscores the need for comprehensive, sector-wide integration of aquatic animal welfare content into formal aquaculture curricula. A more structured and consistent inclusion of welfare principles across programs could address these gaps and improve student preparedness for ethical decision-making in future professional contexts.

4.4. Understanding the Depth of Awareness Gap in Aquatic Animal Welfare

In the domain of animal welfare, cultural and societal values often contribute to a baseline or superficial awareness that does not necessarily translate into the specialized knowledge or practical competencies required for humane and ethical practice [

6]. Educational theory further supports this distinction, cautioning that mere exposure to content, particularly when delivered through rote learning, fails to promote meaningful understanding or skill development. Without structured, experiential, and critically engaging instruction, students are unlikely to develop the cognitive depth needed for applied learning [

43,

44,

45].

Biggs and Tang [

44] differentiate between surface and deep approaches to learning. In surface learning, students focus on memorization and fulfilling basic requirements, while deep learning involves understanding underlying principles, integrating knowledge across contexts, and applying it in new situations. These educational frameworks help explain the observed discrepancy in this study: students may score highly on perception measures, reflecting general awareness of AAW yet still lack a robust conceptual understanding. In the absence of pedagogical strategies that foster deep learning, such as reflective practice, critical analysis, and hands-on engagement, students are likely to remain at the level of surface awareness, unable to fully internalize or operationalize AAW principles.

4.5. Curricular Strengths and Gaps in Aquaculture Animal Welfare Education

Although 79.9% of students expressed satisfaction with teaching and 77.7% were satisfied with available learning resources, only 17.6% reported feeling confident discussing AAW. This notable discrepancy between high satisfaction and low confidence suggests limited exposure to AAW content rather than genuine preparedness, revealing a gap between perceived adequacy and actual competence. These findings are consistent with the low education gap scores reported by most students (74.9%), indicating moderate levels of satisfaction and general awareness, yet a persistent uncertainty regarding the sufficiency and depth of the current curriculum. The fact that over half of students (56.0%) rated themselves as only “somewhat confident” points to the presence of foundational knowledge without the corresponding practical or applied skills. This reinforces the need for pedagogical strategies such as case-based learning, collaborative group discussions, and experiential training to bridge the gap between theoretical awareness and practical application [

44,

46].

A majority of students (across 60% of sampled institutions) preferred integrating AAW content into existing technical modules rather than developing standalone welfare courses. In addition, expert-led workshops and hands-on experiences were ranked highly as preferred instructional methods (

Table 4). These preferences indicate that while awareness of AAW is increasing, many students still view the current educational provision as lacking in both practical depth and applied relevance. The results clearly underscore the need for a more structured, practice-oriented approach to AAW education within aquaculture training programs. A mixed-delivery model embedding welfare topics into core aquaculture subjects, strengthening field-based training, and incorporating expert-led sessions can address diverse student learning needs and foster deeper engagement. Furthermore, for the 20.3% of students who expressed no preference for further inclusion of AAW in the curriculum, emphasizing the career relevance of welfare knowledge may be critical. Aligning AAW principles with professional development goals could enhance student motivation, increase confidence, and ultimately strengthen the long-term impact of welfare education in the sector.

4.6. Understanding Educator’s Perspectives on Aquatic Animal Welfare

Educators identified several systemic barriers to the integration of AAW into existing curricula (

Table 6), including overloaded syllabi, misalignment with Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) frameworks, and limited support or buy-in from key stakeholders of aquaculture sectors. These findings underscore that effective curriculum reform in aquaculture education requires not only pedagogical redesign, but also faculty development, institutional commitment, targeted funding, and engagement from industry and policy stakeholders. Variations in perception scores among educators with differing qualifications further support existing literature suggesting that individual-level factors such as empathy, ethical orientation, and personal values, play a critical role in shaping attitudes toward animal welfare [

16,

42]. These intrinsic factors may influence how educators prioritize welfare content and advocate for its inclusion, regardless of formal policy guidance. As such, fostering awareness and ethical commitment among faculty members may be as crucial as structural curriculum reform in advancing AAW education in Vietnam’s aquaculture sector [

47,

48].

Educators’ responses highlight a fragmented and inconsistent approach to the integration of AAW into aquaculture curricula. Only 4.26% of educators reported satisfaction with comprehensive AAW coverage, while 36.2% indicated partial inclusion. Notably, 46.8% stated that AAW content was currently excluded but planned for future integration, and 48.9% provided no clear response. This high rate of unclear or noncommittal responses likely reflects limited awareness of AAW curriculum content, poor communication regarding curricular updates, and/or the marginal prioritisation of AAW within institutional frameworks. Although plans for future integration indicate a growing recognition of the importance of welfare education, effective implementation will require institutional support in the form of funding, instructional materials, and faculty capacity-building. The significant proportion of uncertain or inadequate responses suggest notable gaps in educator knowledge or engagement with curriculum development, supporting previous findings that faculty buy-in is critical to successful welfare education reform [

10,

12].

Currently, AAW is most often integrated into existing aquaculture courses (23.4%) rather than offered through standalone modules, which risks inconsistent depth and uneven coverage. This piecemeal approach underscores the need for standardized, institution-wide strategies for AAW education. Persistent systemic challenges including curriculum overload, misalignment with national policy frameworks, and limited faculty expertise highlight the urgency of clear policy directives, targeted professional development, and dedicated resources to enable a coherent and comprehensive AAW curriculum across institutions.

4.7. Perspectives of Aquaculture Sector Stakeholders and Opportunities for Collaboration

Aquaculture industry stakeholders identified a substantial disconnect between academic training and the practical demands of the aquaculture sector. Although 70.6% of stakeholders indicated that graduates were sufficiently trained in AAW, 41.2% were unable to provide specific examples to support this perception. This discrepancy reflects a classic knowledge–action gap, in which concern or awareness does not necessarily lead to corresponding behavior or applied skills [

49]. Addressing this gap requires curriculum reforms that prioritize active, experiential learning and real-world application. Stakeholders of aquaculture sector demonstrated strong support for curriculum enhancement, with 88.2% expressing willingness to engage in reform efforts through various mechanisms. Notably, 32.6% offered paid internships and 28.3% endorsed short-term practical modules, reflecting a preference for compensated, hands-on learning opportunities. In contrast, unpaid internships were uncommon (4.35%), suggesting that employers increasingly recognise the need to value students’ time and emerging expertise.

Industry priorities were clearly articulated: technical skill development (21.4%) was identified as the most critical area, followed by welfare-related research (17.6%) and conservation practices (16.0%). These priorities signal growing demand for graduates who possess both scientific competence and practical AAW experience. Embedding these components into academic programs will help bridge the gap between university training and industry expectations. The misalignment between educational preparation and industry requirements can be attributed to insufficient practical exposure and limited integration of welfare-related content. As Parajuli, Pham [

50], Bui and Takuro [

51] observed, low levels of university industry collaboration in Vietnam stem from both weak private-sector engagement and the limited focus of universities on industry-relevant research. Strengthening collaboration through joint curriculum committees, structured internship placements, and regular curriculum review processes will be essential to ensure that academic programs remain responsive to evolving industry needs.

4.8. No Significant Influence of Demographic Variables

In contrast to studies from Western contexts that frequently identify gender and age as significant predictors of animal welfare attitudes [

14,

18] this study found no statistically significant demographic effects (p > 0.05), despite balanced gender representation among both students and educators. This may reflect cultural and educational uniformity in Vietnam, where centralized curricula and relatively homogeneous sociocultural norms can diminish variation across demographic groups.

While international research often highlights religion as a strong modifier of animal welfare perceptions ([

20,

32,

52], the largely secular composition of the Vietnamese population estimated at 66–76% according to recent national census data may explain the absence of religious influence observed in this study [

53,

54]. Similarly, household income did not significantly affect attitudes, potentially due to social desirability bias, wherein respondents underreport divergent views to align with perceived social norms [

55]. This aligns with findings from aquaculture education research in Southeast Asia, where collectivist cultural values and standardized state-led curricula have been shown to moderate individual-level variation in attitudes toward sustainability and welfare [

56,

57]. These results suggest that while demographic predictors may hold explanatory value in Western studies, their influence may be attenuated in contexts like Vietnam, where structural and cultural factors play a more dominant role in shaping welfare perceptions.

4.9. Institutional and Policy Implications

Educators identified several key barriers to integrating AAW into existing curricula, including curriculum overload, limited subject-matter expertise, and institutional resistance to change (

Table 6). These constraints echo the assertion of Fraser [

7] that welfare progress in low- and middle-income countries is often hindered by competing economic priorities and prevailing cultural norms, where animals are frequently valued for their utility rather than their sentience. The findings from this study underscore an urgent need for coherent national policy frameworks, institutional mandates, and capacity-building initiatives to support AAW integration.

Recommended strategies include the development of national guidelines defining AAW learning outcomes aligned with the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) standards; professional development programs to equip educators with in-house expertise; and incentivised university–industry partnerships to promote the application of welfare competencies in real-world settings. Whether implemented through standalone modules, embedded course units, or hands-on placements, any enhancement of AAW curricula must also address the structural education-access gaps faced by lower-income students in Vietnam. As highlighted by Parajuli, Pham [

50], financial barriers can significantly impede equitable participation in higher education, particularly in technical fields. Therefore, targeted scholarships, flexible delivery models, and inclusive teaching approaches are essential to ensure both access to welfare education and its broader impact on aquaculture industry standards.

5. Conclusion

This study applied a mixed-methods design and robust sampling to examine the influence of education on perceptions of AAW, introducing the Awareness Depth Gap framework to distinguish between superficial support and applied understanding. While this enhances generalisability, several limitations warrant consideration. Response bias may have arisen from live survey administration, and the perception scoring system requires further validation through practical competency assessments. The education-gap metric relied on self-reporting and equally weighted criteria, potentially overlooking the differing influence of specific welfare components. Convenience sampling of industry stakeholders also limited representativeness, highlighting the need for randomised, stratified sampling in future work.

Causal links between education and perception remain unconfirmed, and longitudinal or experimental studies are needed to assess whether curricular changes improve attitudes and practices. Future research should pilot targeted AAW training, investigate unmeasured influences (e.g., informal learning, peer networks, institutional culture), and replicate the study in other aquaculture-producing nations to test the framework’s generalisability. In the Vietnamese context, a community development approach is recommended in aligning welfare improvements with human benefits such as nutrition, income, and livelihoods [

8]. This will ensure that advances are both ethically meaningful and socially sustainable.

Author Contributions

Phan Kim Long., Sasha Saugh., Chau Thi Da: Conceptualisation, design of the experiment, and acquisition of funding. Pham Kim Long, Sasha Saugh, Lien-Huong Trinh, Oanh Duong Hoang, Huong Huynh Kim, Pham Van Day, Men Nguyen Thi: Conduct of experiments and data collection. Phan Kim Long., Sasha Saugh., Chau Thi Da: Formal analysis and writing—original draft preparation. Phan Kim Long., Sasha Saugh., Chau Thi Da, Simao Zacarias, John Bostock, David Little: Review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

From Open Philanthropy through the “Improving Farmed Fish Welfare in Asia” Project managed by the University of Stirling.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experiments were conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by TràVinh University (TVU) (reference no. Decision No. 2I7|QE-HDKH&ET).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of time and facilities from Tra Vinh University (TVU) for this study. Gratitude is also extended to the University of Stirling for their valuable support in refining the project design and facilitating access to funding. Finally, the author(s) gratefully acknowledged Open Philanthropy for their financial support, which enabled the successful completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Bank. The World Bank in Viet Nam 2024. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Truong, B. Investing in aquaculture in Vietnam. Vietnam Briefing. 2023.

- De-Jong, D. World Seafood Map 2019. Available online: https://effop.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Rabobank-Seafood-map-May-2019.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- O’Reilly, K. Animal welfare in the implementation of the EU-Vietnam FTA. Eurogroup for Animals 2022. Available online: https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/files/eurogroupforanimals/2022-12/2022_E4A-Vietnam-Report-ENG-screen.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Browning, H.; Birch, J. Animal sentience. Philosophy Compass 2022, 17, 12822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpell, J.A. Factors influencing human attitudes to animals and their welfare. Animal Welfare 2023, 13, S145–S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. Understanding animal welfare. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 2008, 50, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrindle, C.M.E. The community development approach to animal welfare: an African perspective. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 1998, 59, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. Skill and value perceptions: how do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 2008, 4, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M. International perceptions of animals and the importance of their welfare. Frontiers in Animal Science 2022, 3, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2010; https://e-edu.nbu.bg/pluginfile.php/900222/mod_resource/content/1/G.Hofstede_G.J.Hofstede_M.Minkov%20-%20Cultures%20and%20Organizations%20-%20Software%20of%20the%20Mind%203rd_edition%202010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, M.; Phillips, C.J. Key tenets of operational success in international animal welfare initiatives. Animals 2018, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, B.K.; Oosting, S.J.; Bock, B.B. Elements of societal perception of farm animal welfare: A quantitative study in The Netherlands. Livestock Science 2006, 104, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B. A Systematic review of public attitudes, perceptions and behaviours towards production diseases associated with farm animal welfare. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 2016, 29, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Martens, P. How ethical ideologies Relate to public attitudes toward animals: The Dutch case. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A. Gender differences in human–animal interactions: A review. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S. Empathy with animals and with humans: Are they linked? Anthrozoös, 2000, 13, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Martens, P. Public attitudes toward animals and the influential factors in contemporary China. Animal Welfare 2023, 26, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, G. Chinese university students' attitudes toward the ethical treatment and welfare of animals. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 2006, 9, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deemer, D.R.; Lobao, L.M. Public concern with farm-animal welfare: Religion, politics, and human disadvantage in the food sector. Rural Sociology 2011, 76, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M.; Phillips, C.J.C. Asian livestock industry Leaders’ perceptions of the importance of, and solutions for, animal welfare issues. Animals 2019, 9, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijares, S. Perceptions of animal welfare and animal welfare curricula offered for undergraduate and graduate students in animal science departments in the United States. Translational Animal Science 2021, 5, txab222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoll, K.; Samuels, W.E.; Trifone, C. An in-class, humane education program can improve young students' attitudes toward animals. Society & Animals 2008, 16, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, D. Improving the performance of higher education in Vietnam: Strategic priorities and policy options; World Bank: Washington, DC, 2020; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/347431588175259657.

- Yaddanapudi, S.; Yaddanapudi, L.N. How to design a questionnaire. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods 2018, 23, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J. Sampling essentials: Practical guidelines for making sampling choices; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, California, 2012; Available online: https://10.4135/9781452272047 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC). Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC). Report on priorities for animal welfare research and development. Surbiton, Surrey (England) 1993. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/134980.

- Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC). Five freedoms. 2009. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/farm-animal-welfare-committee-fawc.

- Fragoso, A. Animal welfare science: Why and for whom? Animals 2023, 13, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassen, J.; Sandøe, P.; Forkman, B. Happy pigs are dirty: Conflicting perspectives on animal welfare. Livestock Science 2006, 103, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Building Towards One Health: A Transdisciplinary Autoethnographic Approach to Understanding Perceptions of Sustainable Aquatic Foods in Vietnam. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, T.C. Improving productivity in integrated fish-vegetable farming systems with recycled fish pond sediments. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1−19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, E. "Do you consider animal welfare to be important?” activating cognitive dissonance via value activation can promote vegetarian choices. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2022, 83, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, B.; Ewell, C.; Jacquet, J. Animal welfare risks of global aquaculture. Science Advances 2021, 7, eabg0677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Animal Protection, Vietnam: Animal protection index 2020. Available online: https://api.worldanimalprotection.org/country/vietnam.

- Harper, G. Consumer concerns about animal welfare and the impact on food choice 2001. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/1650/2/EU/harper.pdf.

- Ammann, J. Consumers’ meat commitment and the importance of animal welfare as agricultural policy goal. Food Quality and Preference 2023, 112, 105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Girolami, A.; Braghieri, A. Consumer liking and willingness to pay for high welfare animal-based products. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2010, 21, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocella, G.; Hubbard, L.; Scarpa, R. Farm animal welfare, consumer willingness to pay, and trust: Results of a cross-national survey. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 2009, 32, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, D.H. Perspectives on the social sciences in global animal health governance: A qualitative study of experts. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2025, 238, 106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornish, F. Participatory action research. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2023, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C.; Kennedy, G. Teaching for quality learning at university 5e 2022, McGraw-hill education (UK).

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C. Using constructive alignment in outcomes-based teaching and learning teaching for quality learning at university, 3rd ed.; Maidenhead: Open University Press, 1566; pp. 50–63. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1566338.

- Entwistle, N.J.; Peterson, E.R. Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: Relationships with study behaviour and influences of learning environments. International Journal of Educational Research 2004, 41, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development 2014. ISBN: 0133892506, FT press.

- Signal, T.D.; Taylor, N. Attitudes to animals: Demographics within a community sample. Society & Animals 2016, 14, 147–157. Available online: https://www.animalsandsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/signal.pdf.

- Coleman, G.J.; Hemsworth, P.H. Training to improve stockperson beliefs and behaviour towards livestock enhances welfare and productivity. Scientific & Technical Review 2014, 33, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, R.; Pham, H.M.; Wiberg, D. University–industry linkages in the Vietnamese context: A review of challenges and potential solutions. Asia Pacific Education Review 2020, 21, 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, T.T.V.; Takuro, K. Exploring university-industry collaboration in Vietnam: An in-depth review of types and influencing factors. Industry and Higher Education 2024, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A. Evidence for an association between pet behavior and owner attachment levels. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 1996, 47, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSO. Population and housing census 2019: Major findings. Hanoi: General Statistics Office of Vietnam 2020.

- Nguyen, T.M.; Dang, K.A. Secularism and religious life in contemporary Vietnam. Journal of Vietnamese Studies 2021, 16, 70–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.J. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research 1993, 20, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.T.; Le, Q.T.; Bui, T.N. Aquaculture training and rural development in the Mekong Delta: Challenges and reform needs. Journal of Aquaculture Research & Development 2019, 10, 555–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Hossain, M.Z.; Belton, B. Livelihoods, learning, and aquaculture: Education in the context of small-scale fisheries in Bangladesh. Aquaculture Reports 2020, 17, 100–382. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Map of tertiary institutions sampled in South and South-Central Vietnam for the aquatic animal welfare perception survey.

Figure 1.

Map of tertiary institutions sampled in South and South-Central Vietnam for the aquatic animal welfare perception survey.

Figure 2.

Illustration showing seafood consumption frequency among perception survey respondents (students, educators, and aquaculture industry stakeholders) in South and South-central Vietnam.

Figure 2.

Illustration showing seafood consumption frequency among perception survey respondents (students, educators, and aquaculture industry stakeholders) in South and South-central Vietnam.

Figure 3.

Confidence ratings of Vietnamese tertiary education students in discussing various components of aquatic animal welfare including nutrition and feeding, pain, health and disease, natural behaviour, habitat needs, emotional states, environmental enrichment, and ethics and social values revealed that the majority (55.9%, n = 201) of students were somewhat confidentdents were somewhat confident.

Figure 3.

Confidence ratings of Vietnamese tertiary education students in discussing various components of aquatic animal welfare including nutrition and feeding, pain, health and disease, natural behaviour, habitat needs, emotional states, environmental enrichment, and ethics and social values revealed that the majority (55.9%, n = 201) of students were somewhat confidentdents were somewhat confident.

Figure 4.

Illustration of association between perception score and mark-up (%) from educators in Vietnamese tertiary institutions surveyed for the perception study (p =3.18×10−7 ***, df=45, Kendall-Theil Sen).

Figure 4.

Illustration of association between perception score and mark-up (%) from educators in Vietnamese tertiary institutions surveyed for the perception study (p =3.18×10−7 ***, df=45, Kendall-Theil Sen).

Figure 5.

Illustration of association between perception score and mark-up (%) from students in Vietnamese tertiary institutions surveyed for the perception study (p <2 × 10⁻¹⁶***, df=357, Kendall-Theil Sen).

Figure 5.

Illustration of association between perception score and mark-up (%) from students in Vietnamese tertiary institutions surveyed for the perception study (p <2 × 10⁻¹⁶***, df=357, Kendall-Theil Sen).

Figure 6.

Illustration of the negative relationship (slope -0.28) between student perception scores and their education gap scores (p = 1.25 × 10⁻¹²**, df=357, Kendall Theil Sen), suggesting that students with larger gaps in aquatic animal welfare have associated lower perceptions on it.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the negative relationship (slope -0.28) between student perception scores and their education gap scores (p = 1.25 × 10⁻¹²**, df=357, Kendall Theil Sen), suggesting that students with larger gaps in aquatic animal welfare have associated lower perceptions on it.

Table 1.

Summary of tertiary institutions sampled in South and south-central Vietnam, including majors of interest, and student and educator sample sizes. Where multiple majors were present at an institution, sample numbers are indicated in brackets.

Table 1.

Summary of tertiary institutions sampled in South and south-central Vietnam, including majors of interest, and student and educator sample sizes. Where multiple majors were present at an institution, sample numbers are indicated in brackets.

| Institution names |

Majors |

Students |

Educators |

| Colleges |

31 |

9 |

| Bạc Liêu College of Economics and Technology |

- Aquaculture diploma |

7 |

2 |

| Cà Mau Community College |

- Aquaculture diploma |

7 |

2 |

| Đồng Tháp Community College |

- Aquaculture diploma |

4 |

1 |

| Sóc Trăng Vocational College |

- Aquaculture diploma

- Engineer aquaculture post- harvest |

11 |

3 |

| Southern Agricultural College |

- Aquaculture diploma |

2 |

1 |

| Universities |

328 |

38 |

| Bạc Liêu University |

- Engineer aquaculture

- Engineer aquatic resource management (n=17)

- Engineer aquaculture (n=76)

- Engineer aquaculture pathology (n=22)

- Engineer aquaculture post-harvest (n=35) |

34 |

4 |

| Cần Thơ University |

150 |

15 |

| Ho Chi Minh City University of Agriculture and Forestry |

- Engineer aquatic resource management (n=7)

- Engineer aquaculture (n=19)

- Engineer aquaculture pathology (n=6)

- Engineer aquaculture post-harvest (n=20) |

52 |

5 |

| Nha Trang University |

- Engineer aquaculture |

41 |

6 |

| TràVinh University |

- Engineer aquaculture |

51 |

8 |

Table 2.

Scoring scale for education gap scores for the student survey that were calculated based on four criteria: (i) confidence in discussing AAW topics, (ii) perception of curriculum sufficiency in covering AAW, (iii) satisfaction with materials, resources, and overall learning experiences, and (iv) satisfaction with instructors teaching AAW.

Table 2.

Scoring scale for education gap scores for the student survey that were calculated based on four criteria: (i) confidence in discussing AAW topics, (ii) perception of curriculum sufficiency in covering AAW, (iii) satisfaction with materials, resources, and overall learning experiences, and (iv) satisfaction with instructors teaching AAW.

| Education gap levels |

Score range |

Description |

| Very low |

0−10 |

Students have a high level of confidence concerning AAW knowledge, are satisfied with their curriculum and instructors, and feel they are taught adequate AAW. |

| Low |

11−20 |

Students are moderately confident, relatively satisfied with learning materials and instructors, but may feel uncertain about the sufficiency of AAW coverage in the curriculum. |

| Moderate |

21−30 |

Students have low confidence, are dissatisfied with learning resources or instructor quality, and perceive a lack of sufficient AAW education. |

| High |

31−40 |

Students lack confidence, express dissatisfaction or disinterest in AAW content, and feel the curriculum does not adequately address AAW. |

Table 3.

Demographic details included age, religion, income and experiences of survey participants.

Table 3.

Demographic details included age, religion, income and experiences of survey participants.

| Variables |

Category |

Students (n=359) |

Educators (n=47) |

Aquaculture sector stakeholders (n=34) |

| Gender (%) |

Male |

55.2 |

| Female |

43.9 |

| Undisclosed |

0.9 |

| Age (Year) (%) |

18–21 |

61.6 |

- |

- |

| 22–25 |

37.3 |

- |

- |

| 26–30 |

0.6 |

- |

- |

| > 30 |

0.6 |

- |

- |

| 36–45 |

- |

66.0 |

55.9 |

| 46–55 |

- |

29.8 |

11.8 |

| 56–65 |

- |

4.3 |

8.8 |

| 25–35 |

- |

- |

23.5 |

| Religion (%) |

Buddhism |

24.0 |

8.5 |

8.8 |

| Catholic |

4.2 |

4.3 |

5.9 |

| None |

66.0 |

76.6 |

70.6 |

| Other |

5.8 |

4.3 |

8.8 |

| No answer |

- |

6.4 |

5.9 |

Monthly income

(Million VND) |

< 10 |

69.9 |

10.6 |

17.6 |

| 10–20 |

22.8 |

61.7 |

32.4 |

| 20–30 |

5.3 |

17.0 |

23.5 |

| > 30 |

2.0 |

10.6 |

20.6 |

| No answer |

- |

- |

5.9 |

| Teaching experience (%) |

0–5 years |

- |

4.3 |

- |

| 6–10 years |

- |

10.6 |

- |

| 11–15 years |

- |

21.3 |

- |

| > 15 years |

- |

63.8 |

- |

Table 4.

Number of Vietnamese tertiary students (n=359) recommending various methods for including and improving AAW content in the curriculum, across the different institutions sampled.

Table 4.

Number of Vietnamese tertiary students (n=359) recommending various methods for including and improving AAW content in the curriculum, across the different institutions sampled.

| Tertiary institution |

A new subject |

Integration into technical subjects |

More practical experience |

Talks, seminars, workshops with specialists |

| Bạc Liêu College of Economics and Technology (n=7) |

2 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

| Bạc Liêu University (n=34) |

19 |

19 |

17 |

14 |

| Cà Mau Community College (n=7) |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

| Cần Thơ University (n=150) |

73 |

76 |

94 |

66 |

| Đồng Tháp Community College (n=4) |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

| Ho Chi Minh City University of Agriculture and Forestry (n=52) |

15 |

35 |

25 |

16 |

| Nha Trang University (n=41) |

14 |

19 |

17 |

21 |

| Sóc Trăng Vocational College (n=11) |

4 |

8 |

8 |

6 |

| Southern Agricultural College (n=2) |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| TràVinh University (n=51) |

17 |

16 |

25 |

23 |

Table 5.

Collective recommendations by educators (n=47) for improving the teaching of AAW at their institutions and departments in South and South central Vietnam.

Table 5.

Collective recommendations by educators (n=47) for improving the teaching of AAW at their institutions and departments in South and South central Vietnam.

| Recommendation category |

Frequency (%) |

Key suggestions |

| Dedicated curriculum content |

27.66 |

Introduce dedicated modules or subjects, integrate into aquaculture theory, or offer elective courses. |

| Awareness and ethical understanding |

10.64 |

Enhance knowledge through the KAP (Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices) model, ethical principles, and welfare awareness. |

| Practical welfare applications |

10.64 |

Include topics such as anesthetic use, sustainable husbandry, humane harvesting, and environmental management. |

| Interdisciplinary and sector-specific content |

12.77 |

Align AAW with fisheries law, aquatic processing, scientific research, and sector-specific requirements. |

| Workshops and curriculum updates |

6.38 |

Organize workshops with expert input and ensure regular updates on regulations and standards. |

| Resource development and expertise |

4.26 |

Develop educator expertise and allocate resources for effective AAW teaching. |

Table 6.

Anticipated challenges to AAW curriculum integration as reported by educators (n=47).

Table 6.

Anticipated challenges to AAW curriculum integration as reported by educators (n=47).

| Category |

Challenges |

Response frequency (%) |

| Awareness and understanding of AAW |

(i) Lack of understanding and awareness of AAW’s importance across various societal groups, including cultural contexts.

(ii) Limited familiarity with recent AAW developments, particularly among farmers and consumers.

(iii) Prevailing attitudes that prioritize aquatic animals’ utility over welfare considerations. |

19.15 |

| Curriculum and educational structure |

(i) Curriculum overload and restricted time or resources.

(ii) Need for alignment with Ministry of Education policies and frameworks.

(iii) Fragmented AAW coverage across multiple modules and absence of a dedicated subject. |

21.28 |

| Economic and institutional constraints |

(i) Emphasis on economic efficiency and profit margins in the industry at the expense of welfare considerations.

(ii) High financial investment required to incorporate AAW into curricula. |

10.64 |

| Expertise and training |

(i) Lack of field-specific AAW expertise and insufficient staff training. (ii) Reluctance among educators to invest in skill development. (iii) Absence of a national or institutional reference model for AAW. |

14.89 |

| Resistance to change and culture |

(i) Institutional resistance due to entrenched traditions and low levels of interest in AAW among some individuals or departments. |

4.00 |

| Information and resources |

(i) Inadequate access to AAW-related information and teaching resources.

(ii) Lack of established national legislation governing animal welfare. |

3.00 |

| Uncertainty |

(i) Ambiguity surrounding the potential outcomes of curriculum changes involving AAW. |

8.00 |

Table 7.

Responses from Vietnamese students, educators, and stakeholders (%) on their understanding of fish welfare. Figures reflect the percentage of welfare criteria mentioned per response, not individual respondents, which are based on the total criteria identified within each respondent category.

Table 7.

Responses from Vietnamese students, educators, and stakeholders (%) on their understanding of fish welfare. Figures reflect the percentage of welfare criteria mentioned per response, not individual respondents, which are based on the total criteria identified within each respondent category.

| Respondent category |

Human concern (ethics, morals, humane treatment) (%) |

Legal responsibility (regulations & rights) (%) |

5 freedoms of animal welfare (%) |

Impact on variety activities (farming, harvest, slaughter, transport, handling, etc.) (%) |

| Students (n=359) |

32.59 |

23.68 |

53.76 |

7.52 |

| Educators (n=47) |

29.51 |

27.87 |

27.87 |

14.75 |

| Aquaculture sector stakeholders (n=34) |

44.83 |

3.45 |

34.48 |

17.24 |

Table 8.

Score scale for perception scores (Standardised to 100), score ranges, and scores for students, educators, and stakeholders in South and south-central Vietnam, for welfare scoring questions from the perception survey (% of responses).

Table 8.

Score scale for perception scores (Standardised to 100), score ranges, and scores for students, educators, and stakeholders in South and south-central Vietnam, for welfare scoring questions from the perception survey (% of responses).

| Respondent category |

Low |

Moderate |

High |

Very high |

| 0−25 |

26−50 |

51−75 |

76−100 |

| Students (n=359) |

0.56 |

11.70 |

48.75 |

39.00 |

| Educators (n=47) |

2.13 |

17.02 |

31.91 |

48.94 |

| Aquaculture sector stakeholders (n=34) |

0 |

5.88 |

52.94 |

41.18 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).