1. Introduction

For over half a century, Yang-Mills gauge theory has formed the mathematical bedrock of the Standard Model of particle physics, describing the electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions with unprecedented accuracy. Despite its phenomenal predictive success, its foundation is often perceived as resting on a set of brilliant but abstract mathematical postulates. The principle of local gauge invariance, while powerful, is typically introduced as a formal requirement rather than a concept derived from a deeper, more intuitive physical or philosophical picture. This leaves a lingering question: is the gauge structure of our universe a fundamental truth about reality, or merely a convenient mathematical tool?

This paper argues for the former. We propose that the structure of Yang-Mills theory is the inevitable consequence of a relational ontology, where physical properties are not intrinsic to objects but emerge from the network of relationships between them. We take as our starting point Covariant Rotation Geometry (CRG), a framework that reinterprets rotation not as a property of a single object against an absolute background, but as a relationship between multiple entities.

Our central thesis is that by elevating this relational view to a first principle and systematically developing its consequences, one can derive the entire structure of Yang-Mills theory without postulating it. We demonstrate that:

Generalizing the relational structure of CRG to accommodate non-commuting finite rotations naturally leads to a non-Abelian group structure.

Introducing dynamics into this relational network necessitates the existence of a connection field (the gauge field) to maintain relational consistency across spacetime.

The curvature of this connection (the field strength) arises as a measure of relational inconsistency around a closed loop.

The demand for a Lorentz-invariant and gauge-invariant action that quantifies this inconsistency uniquely leads to the Yang-Mills action.

This approach recasts Yang-Mills theory from a purely mathematical construct into a physical theory grounded in a clear ontological principle. It provides a conceptual bridge between Einstein’s vision of geometrizing physics and Yang’s principle that symmetry dictates interaction, suggesting both are manifestations of a fundamentally relational reality.

1.1. Overview of the Paper

We begin by revisiting the core tenets of CRG and motivating its generalization to a non-Abelian framework, which we call Generalized Covariant Rotation Geometry (GCRG). We then show how the GCRG structure is equivalent to a principal fiber bundle, where the gauge connection and curvature find a natural geometric interpretation. Next, we introduce dynamics and derive the Yang-Mills field strength from the failure of relational transitivity around an infinitesimal loop. From this, we construct the gauge-invariant action for the pure gauge field. We then extend the framework to include matter fields, showing that their interaction with gauge fields is also a necessary consequence of relational principles. Finally, we provide concrete examples for SU(2) and SU(3), connect the generalized theory back to the original CRG in the Abelian limit, and discuss the profound physical and philosophical implications of our relational interpretation of gauge theory.

2. From CRG to Gauge Theory: Conceptual Upgrade

2.1. Core Structure of CRG Revisited

Covariant Rotation Geometry is built upon a relational ontology where physical reality is described by entities and their relationships:

Definition 1 (Basic Entities)

. The fundamental entities form a set .

Definition 2 (Relational States)

. For each pair of entities , there is a relational state satisfying:

Theorem 1 (Structure Theorem)

. There exists a global field such that .

Theorem 2 (Gauge Symmetry)

. The transformation (where is a constant vector) leaves all physical observables invariant.

This structure is essentially an Abelian gauge theory with gauge group , which is the translation group (or additive group ).

2.2. Motivation for Non-Abelian Generalization

In CRG, rotations are simplified to angular velocity vector addition, which implicitly assumes that the rotation group is Abelian. However, the true three-dimensional rotation group is non-Abelian: finite rotations do not commute.

Remark 1 (Key Insight)

. Axiom 4 of CRG () holds only for infinitesimal rotations (i.e., at the Lie algebra level). For finite rotations, we must use group multiplication: , where .

Therefore, to construct a more realistic geometry, we must elevate the basic relations from Lie algebra-valued () to Lie group-valued (, where G is a compact Lie group).

3. Constructing Generalized Covariant Rotation Geometry (GCRG)

We now generalize CRG to a non-Abelian framework:

3.1. Basic Entities and Relations

Definition 3 (Entity Set)

. The entity set remains .

Definition 4 (Basic Relations)

. For each pair of entities , we assign a group element , where G is a compact semi-simple Lie group (such as , ), satisfying:

This is precisely the discrete version of parallel transport on a principal bundle.

3.2. Geometric Interpretation: Principal Bundles and Connections

To fully understand the geometric meaning of GCRG, we need to establish its connection to the theory of principal bundles and connections.

Definition 5 (Principal Bundle)

. A principal G-bundle over a manifold M is a fiber bundle where:

P is the total space, M is the base space, G is the structure group

G acts freely and transitively on each fiber

The bundle is locally trivial: for open sets

Theorem 3 (GCRG as Discrete Principal Bundle)

. In GCRG, the collection defines a discrete principal G-bundle where:

The "base manifold" is the discrete set of entities

Each entity corresponds to a "fiber" over point i

The group elements represent "transition functions" between fibers

Proof. The transition functions must satisfy the cocycle condition:

This is precisely the transitivity condition in GCRG. The antisymmetry condition

ensures that the transition functions are invertible, as required for a principal bundle. □

Definition 6 (Connection on Principal Bundle)

. A connection on a principal G-bundle is a -valued 1-form A on P that:

In local coordinates, the connection is represented by the gauge field .

Theorem 4 (GCRG Connection as Discrete Gauge Field)

.

In the continuum limit, the discrete relations give rise to a connection 1-form A such that:

This connection encodes the "relational dynamics" between entities.

3.3. Curvature as Geometric Obstruction

Definition 7 (Curvature of Connection)

.

The curvature 2-form F of a connection A is defined by:

In components: .

Theorem 5 (Curvature as Relational Inconsistency)

. In GCRG, the curvature measures the failure of the relational structure to be "flat." Specifically:

Proof. Consider a small loop in spacetime. If the connection were flat (

), parallel transport around the loop would return to the identity:

However, if

, the Wilson loop is non-trivial:

This non-trivial Wilson loop represents the geometric obstruction to consistent relational transport. □

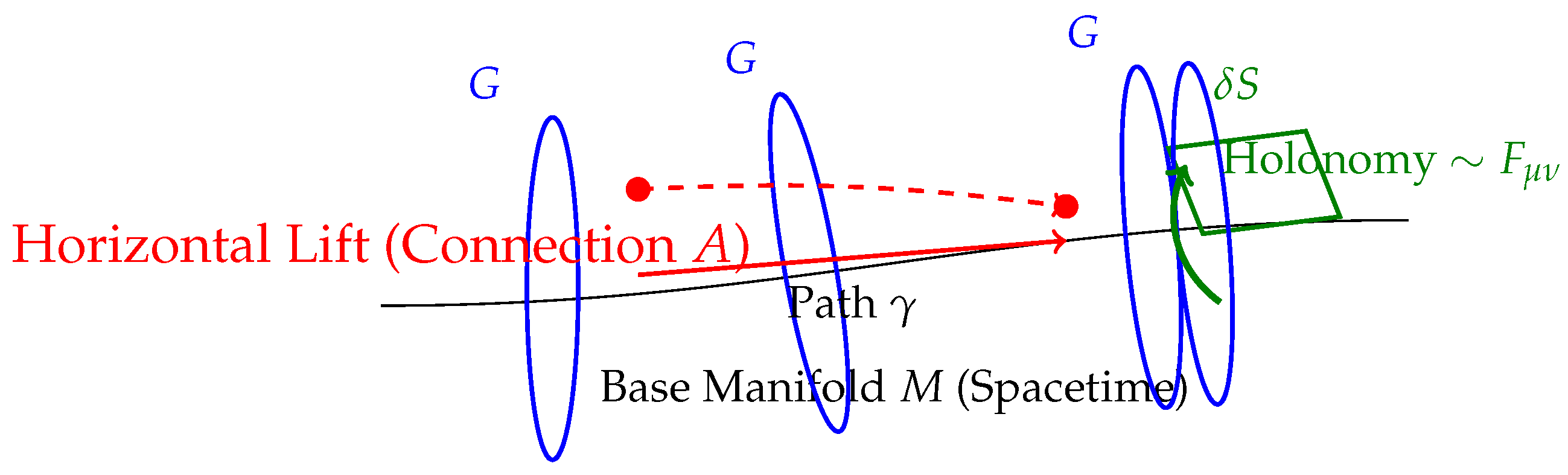

Figure 1.

The geometric interpretation of GCRG as a principal G-bundle. A path on the base manifold M is lifted to a path in the total space P via the connection A. The curvature is manifest as the holonomy (a vertical displacement in the fiber) resulting from parallel transport around an infinitesimal loop .

Figure 1.

The geometric interpretation of GCRG as a principal G-bundle. A path on the base manifold M is lifted to a path in the total space P via the connection A. The curvature is manifest as the holonomy (a vertical displacement in the fiber) resulting from parallel transport around an infinitesimal loop .

3.4. Relational Reality Principle

Definition 8 (Relational Reality)

. Physical reality is completely described by the collection .

This principle establishes that all physical properties emerge from relations between entities, not from intrinsic attributes of the entities themselves.

3.5. Structure Theorem (Non-Abelian Version)

Theorem 6 (Structure Theorem)

. If E is connected, there exists a mapping such that .

Proof. Fix

and let

. Then:

since

. This completes the proof. □

3.6. Gauge Symmetry

Consider the transformation

, where

is a

global constant group element. Then:

This is not ideal if we require to be invariant.

Theorem 7 (Correct Gauge Transformation)

.

Define local gauge transformations: , where depends on i. Then:

To keep invariant, we must introduce aconnection that transforms as:

This ensures that the Wilson line

transforms correctly under local gauge transformations.

4. Introducing Dynamics: From Static Relations to Gauge Fields

Static relations describe "geometry" but lack dynamics. To describe evolution, we must introduce a connection—the gauge field.

4.1. Discrete Spacetime and Connection

Assume that entities

also label

spacetime points (or events). Consider two adjacent points

i and

j, and define the

gauge connection (Lie algebra) such that:

for an infinitesimal path.

In the discrete setting, it’s more natural to treat as the fundamental variable, with A being its logarithm.

4.2. Emergence of Curvature (Field Strength)

In non-Abelian theories, the transitivity holds only in the curvature-free case. If there are interactions or dynamical degrees of freedom, the product along a closed loop is not the identity element.

Definition 9 (Curvature/Field Strength)

.

Define the curvature (or field strength) as the Wilson loop: For a triangle , define

By the transitivity axiom, if there are no dynamical degrees of freedom, then . But if we allow the geometry to "curve," then , which is precisely the discrete version of gauge field strength.

In the continuum limit, we consider an infinitesimal loop in the - plane. For a small parallelogram with sides and , we need to carefully compute the Wilson loop.

Theorem 8 (Detailed Wilson Loop Calculation)

.

For an infinitesimal parallelogram in the μ-ν plane with vertices at coordinates x, , , and , the Wilson loop is:

where is the boundary of the parallelogram traversed counterclockwise.

Proof. Let the infinitesimal parallelogram have vertices at

x,

,

, and

, where

and

. The Wilson loop is the path-ordered product of four segments:

where the segments are traversed in the order

.

: from x to . .

: from to . .

: from to . This is a path in the direction. .

: from to x. This is a path in the direction. .

We use Taylor expansion for the gauge fields at different points:

Now, we compute the product

, keeping terms up to the second order in

(i.e., of order

).

First, compute

:

Next, compute

:

Finally, we multiply the two results:

. We only need to keep terms up to second order. The inverse of

up to second order is approximately

. A more direct multiplication is clearer:

Collecting all terms up to order

:

The terms linear in cancel out: .

The quadratic terms in the same direction, like , are of order and can be ignored compared to the area element .

The term appears with a plus sign from the expansion and with a minus sign from the cross-term , so they cancel.

We are left with the crucial terms:

where we have reordered the terms and used the definition of the commutator

. The area element is

. Thus, we find:

This rigorously derives the field strength tensor from the Wilson loop. □

Therefore, we define the field strength tensor as:

This is exactly the Yang-Mills field strength! The commutator term is the crucial non-Abelian contribution that vanishes in the Abelian case.

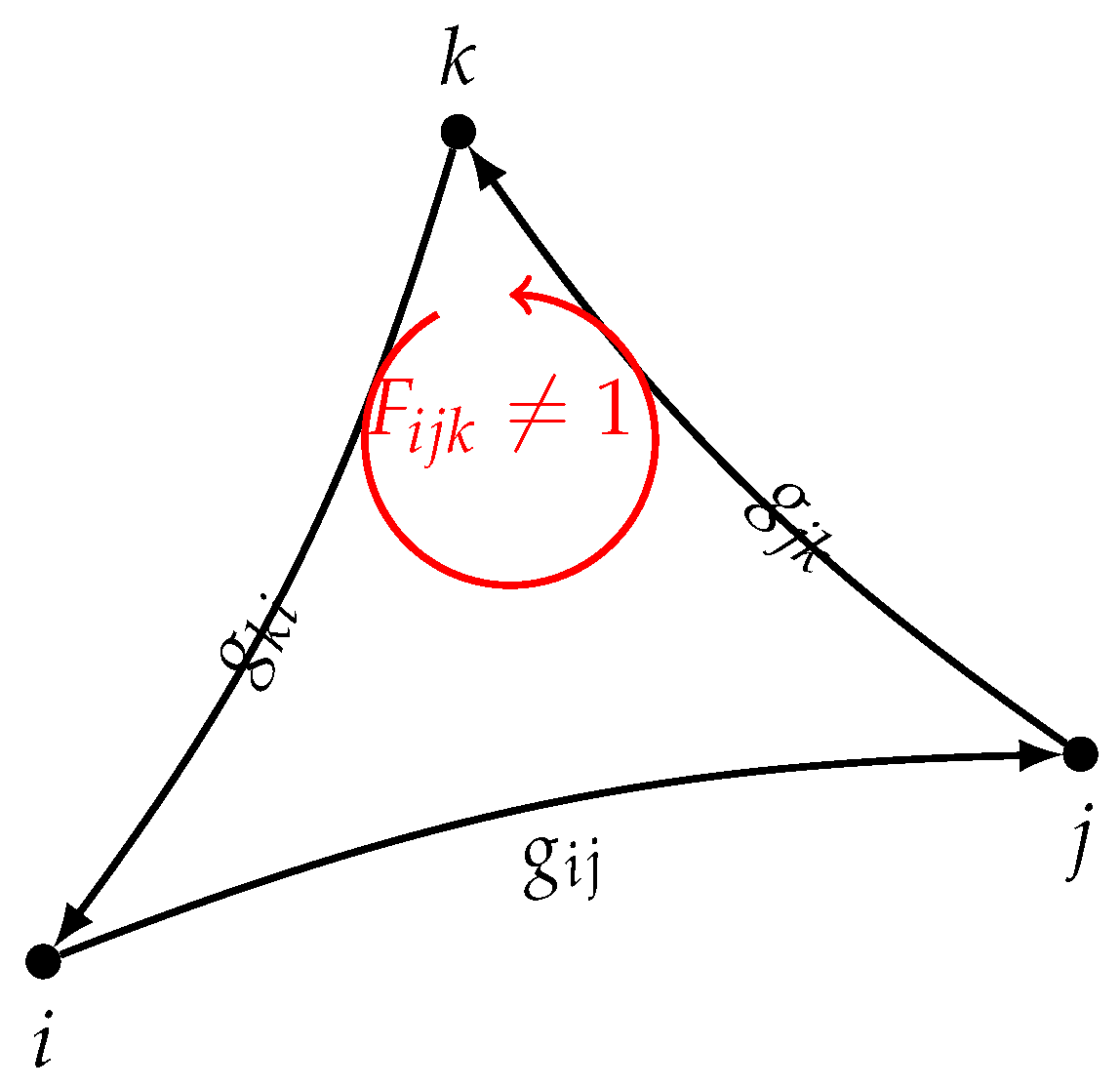

Figure 2.

The Wilson loop as a measure of discrete curvature. In a curved relational geometry, traversing a closed loop of relations does not return to the identity element. The resulting holonomy, , quantifies this relational inconsistency, which corresponds to the field strength.

Figure 2.

The Wilson loop as a measure of discrete curvature. In a curved relational geometry, traversing a closed loop of relations does not return to the identity element. The resulting holonomy, , quantifies this relational inconsistency, which corresponds to the field strength.

5. Action Principle: From Relational Invariance to Yang-Mills Action

5.1. Physical Requirements

The action S must satisfy several key physical requirements:

S must be gauge invariant (i.e., independent of the observer’s choice of )

S should depend on the curvature F, since a trivial connection () should correspond to a "free" state

In the weak field limit, it should reduce to the kinetic form of CRG

5.2. Constructing Gauge Invariants

The most natural scalar is , because:

5.3. Emergence of Yang-Mills Action

To construct the action, we need to identify a gauge-invariant quantity that measures the "degree of inconsistency" in the relational structure. In GCRG, physical reality is described by , but dynamics requires us to allow to not strictly satisfy transitivity (i.e., ).

Theorem 9 (Action Construction from Relational Inconsistency)

. The action should penalize the degree of "inconsistency" in the relational structure. For a small loop, this is measured by . In the continuum limit, this becomes proportional to .

Proof. Consider the Wilson loop

. For small loops, we can expand:

The "inconsistency" is measured by the deviation from the identity:

For a matrix Lie group, the natural norm is the Killing form, which gives:

Integrating over all spacetime, we obtain the action:

where g is the coupling constant that determines the "stiffness" of relational dynamics. □

5.4. Variational Principle and Equations of Motion

Theorem 10 (Yang-Mills Equations from Variational Principle)

. The Yang-Mills equations of motion follow from the variational principle applied to the action .

Proof. We need to compute the variation of the action with respect to the gauge field

. Since

, we have:

where

is the covariant derivative:

.

The variation of the action is:

Using integration by parts and the fact that

:

For the action to be stationary (

) for arbitrary variations

, we must have:

This is the

Yang-Mills equation, which can be written explicitly as:

□

5.5. Rigorous Gauge Invariance Proof

Theorem 11 (Gauge Invariance of Yang-Mills Action)

. The Yang-Mills action is invariant under local gauge transformations.

Proof. Under a local gauge transformation

, the gauge field transforms as:

Note: We use the common physics convention

, which is equivalent to the one with

up to a sign convention in the covariant derivative. Let’s compute the transformed field strength

.

First, let’s compute the derivative terms:

Using the identity

, this becomes:

So, for

:

Next, let’s compute the commutator term

:

Using

, the first term is

. The other terms are:

Simplifying this expression:

Now, we add the two parts, . We can see that the extra terms cancel out perfectly:

The terms like from the derivative part cancel with terms like from the commutator part.

The terms like from the derivative part cancel with terms like from the commutator part.

The commutator of derivatives from the derivative part cancels with the same term with an opposite sign from the commutator part.

We are left with only the desired terms:

Therefore, the field strength tensor transforms covariantly. The trace in the action is then invariant:

where we used the cyclic property of the trace. Thus, the action is gauge invariant. □

This action satisfies all the physical requirements:

It is gauge invariant because is invariant under gauge transformations .

It depends on the curvature F, so a trivial connection () corresponds to a "free" state with zero action.

In the weak field limit, it reduces to the kinetic form of CRG.

6. Introducing Matter: Fermions in the Relational Framework

So far, our discussion has focused on the dynamics of the gauge fields themselves, which mediate interactions. However, a complete physical theory must also describe the entities that interact—the matter fields (e.g., electrons and quarks). In this section, we extend the GCRG framework to include matter, demonstrating that the interaction between matter and gauge fields is also a necessary consequence of relational ontology.

6.1. The Relational Role of Matter Fields

In the GCRG framework, we can posit that each fundamental entity is not just a point in a relational network, but also possesses an internal state. This state is described by a field, , which we associate with matter. For fermions like electrons, is a spinor field.

Definition 10 (Matter Field)

. A matter field is a field that lives in a representation of the gauge group G. It is associated with the entities (or spacetime points) and describes their intrinsic state.

For a particle to be fundamental, its properties should not depend on the observer’s relational perspective. This leads directly to the requirement of gauge invariance.

6.2. Gauge Transformation of Matter Fields and the Covariant Derivative

If we change our relational frame at each point

x by a local gauge transformation

, the description of the matter state

must transform accordingly. For a field

in the fundamental representation, it transforms as:

Now, consider the derivative

, which is needed to define the kinetic energy of the field. Under a gauge transformation, it transforms as:

This transformation is not covariant because of the extra term

. A simple derivative

is not gauge-invariant, meaning it has no physical meaning in a relational theory because it depends on the observer’s arbitrary choice of gauge.

To solve this, we must introduce a covariant derivative that transforms just like itself. This is precisely where the gauge field comes in. The gauge field acts as a connection that allows us to compare the state at infinitesimally separated points x and in a gauge-invariant way.

Definition 11 (Covariant Derivative)

.

The covariant derivative is defined as:

where is the gauge field (connection) and g is the coupling constant. The term is designed to cancel the unwanted term in the transformation.

Theorem 12 (Covariance of the Covariant Derivative)

.

The covariant derivative of a matter field, , transforms covariantly under a gauge transformation:

Proof. We apply the transformation to

:

Using the identity

, the last term becomes:

Substituting this back, we get:

This shows that

transforms in the same way as

, making it a gauge-covariant quantity. □

6.3. Gauge-Invariant Action for Matter Fields

With the covariant derivative, we can now construct a gauge-invariant action for a fermion field

. For a Dirac fermion, the action is:

where

and

are the Dirac matrices. This action is Lorentz invariant and, by construction, gauge invariant.

Expanding the covariant derivative, we get:

This action consists of two parts:

: The kinetic and mass term for a free fermion.

: The interaction term that describes the coupling between the matter field and the gauge field .

This confirms a key principle: in GCRG, the interaction between matter and force fields is not an ad-hoc addition but a necessary consequence of demanding that the theory respects the relational principle of local gauge invariance.

6.4. The Complete Yang-Mills Theory with Matter

By combining the action for the pure gauge field and the action for the matter field, we arrive at the full Lagrangian for a Yang-Mills theory coupled to fermions:

This Lagrangian is the foundation of theories like Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), which describes the strong interaction between quarks and gluons.

This completes our derivation. Starting from the simple relational principle of CRG, we have naturally arrived at the complete mathematical structure of Yang-Mills gauge theories, including the dynamics of the force fields and their interaction with matter.

7. From Classical Action to Quantum Theory: A Conceptual Bridge

Our derivation has successfully produced the classical Lagrangian for Yang-Mills theory coupled to matter. However, the Standard Model is a quantum field theory. In this section, we briefly discuss how the relational framework provides a conceptual bridge to the quantum realm, suggesting that quantization is not just a mathematical procedure but a natural extension of relational principles.

7.1. The Path Integral Formalism

The primary method for quantizing gauge theories is the path integral formalism, developed by Richard Feynman. In this approach, the probability amplitude for a system to transition from an initial state to a final state is given by summing over all possible field configurations that connect the two states. Each configuration is weighted by a phase factor determined by the classical action

S:

where

represents a sum (an integral) over all possible configurations of the gauge field

and matter fields

.

7.2. A Relational Interpretation of the Path Integral

From the perspective of GCRG, the path integral acquires a beautiful and intuitive interpretation. The classical action S measures the "cost" of relational inconsistency. A field configuration with zero curvature () corresponds to a perfectly consistent relational geometry and is a minimum of the action.

The path integral can be re-conceptualized as follows:

The quantum transition amplitude is the coherent sum over all possible ways the relational geometry of the universe could have evolved.

In this view:

The integration measure is a sum over all possible relational geometries, not just abstract field configurations.

The term assigns a complex phase to each geometry. Geometries that are close to the classical solution (i.e., those with minimal relational inconsistency) interfere constructively, while those far from it tend to interfere destructively and cancel out.

Planck’s constant, ℏ, sets the scale for what constitutes a significant deviation from classical relational consistency. In the limit , only the path of least action (the classical solution) survives, as expected.

This relational interpretation of quantization suggests that the quantum world’s probabilistic nature and superposition of states might be rooted in the universe exploring all possible relational structures simultaneously. It provides a conceptual foundation for why the path integral is the correct way to quantize a gauge theory derived from relational principles.

8. Concrete Examples: SU(2) and SU(3) Yang-Mills Theories

Before establishing the connection to the original CRG, we provide concrete examples of how our framework applies to the specific Lie groups that appear in the Standard Model.

8.1. SU(2) Yang-Mills Theory: The Weak Interaction

Definition 12 (SU(2) Group and Algebra)

. The special unitary group consists of complex matrices U satisfying:

(unitarity)

(special)

The Lie algebra consists of traceless Hermitian matrices.

Theorem 13 (SU(2) Generators and Structure Constants)

.

The algebra is spanned by the Pauli matrices:

The generators are for , satisfying:

where is the Levi-Civita symbol.

Proof. Direct computation shows:

□

Example 1 (SU(2) Gauge Field and Field Strength)

.

For SU(2) Yang-Mills theory, the gauge field is:

where are real-valued functions. The field strength becomes:

where:

8.2. SU(3) Yang-Mills Theory: The Strong Interaction

Definition 13 (SU(3) Group and Algebra)

. The special unitary group consists of complex matrices U satisfying:

(unitarity)

(special)

The Lie algebra consists of traceless Hermitian matrices.

Theorem 14 (SU(3) Generators: Gell-Mann Matrices)

.

The algebra is spanned by the eight Gell-Mann matrices:

The generators are for , satisfying:

where are the SU(3) structure constants.

Example 2 (SU(3) Structure Constants)

.

Some non-zero SU(3) structure constants include:

8.3. Relational Interpretation of Non-Abelian Structure

Theorem 15 (Physical Meaning of Non-Commutativity)

. In GCRG, the non-commutativity of the gauge group reflects the fundamental fact that the order of relational comparisons matters. For SU(2) and SU(3), this manifests as:

Proof. Consider two SU(2) group elements

. In the relational framework, these represent different ways of relating entities through weak isospin. The fact that

in general means that:

"First applying relation , then " yields a different result than "first applying relation , then "

This non-commutativity is the mathematical expression of the physical principle that

relational order matters in non-Abelian interactions. □

8.4. Killing Form and Action Normalization

Theorem 16 (Killing Form for SU(N))

.

For , the Killing form is:

where .

Corollary 1 (Normalized Yang-Mills Action)

.

Using the Killing form normalization, the Yang-Mills action for SU(N) becomes:

This ensures that the action has the correct normalization for all SU(N) groups.

9. Connection to Original CRG: Abelian Limit

To establish the connection between our generalized theory and the original CRG, we consider the Abelian limit where (or ).

Theorem 17 (Abelian Limit)

. In the Abelian limit , GCRG reduces to:

(commutator vanishes)

(standard electromagnetic field strength)

(electromagnetic action)

Proof. For

, the group elements are phases

where

. The connection

is a real-valued 1-form, and the field strength becomes:

since the commutator

for Abelian groups. The action simplifies to:

which is precisely the action for

electromagnetism. □

9.1. Static Limit and CRG

The original CRG can be recovered as the static, time-component-only limit of the Abelian theory. In this case:

The spatial components (no spatial variation)

Only the time component remains, which corresponds to the original in CRG

The field strength (no dynamics)

Corollary 2 (CRG as a Limit of Yang-Mills)

. CRG is the limit of Yang-Mills theory in the static, Abelian, time-component-only case. This establishes CRG as a special case of the more general Yang-Mills framework, providing a solid foundation for our relational approach to gauge theories.

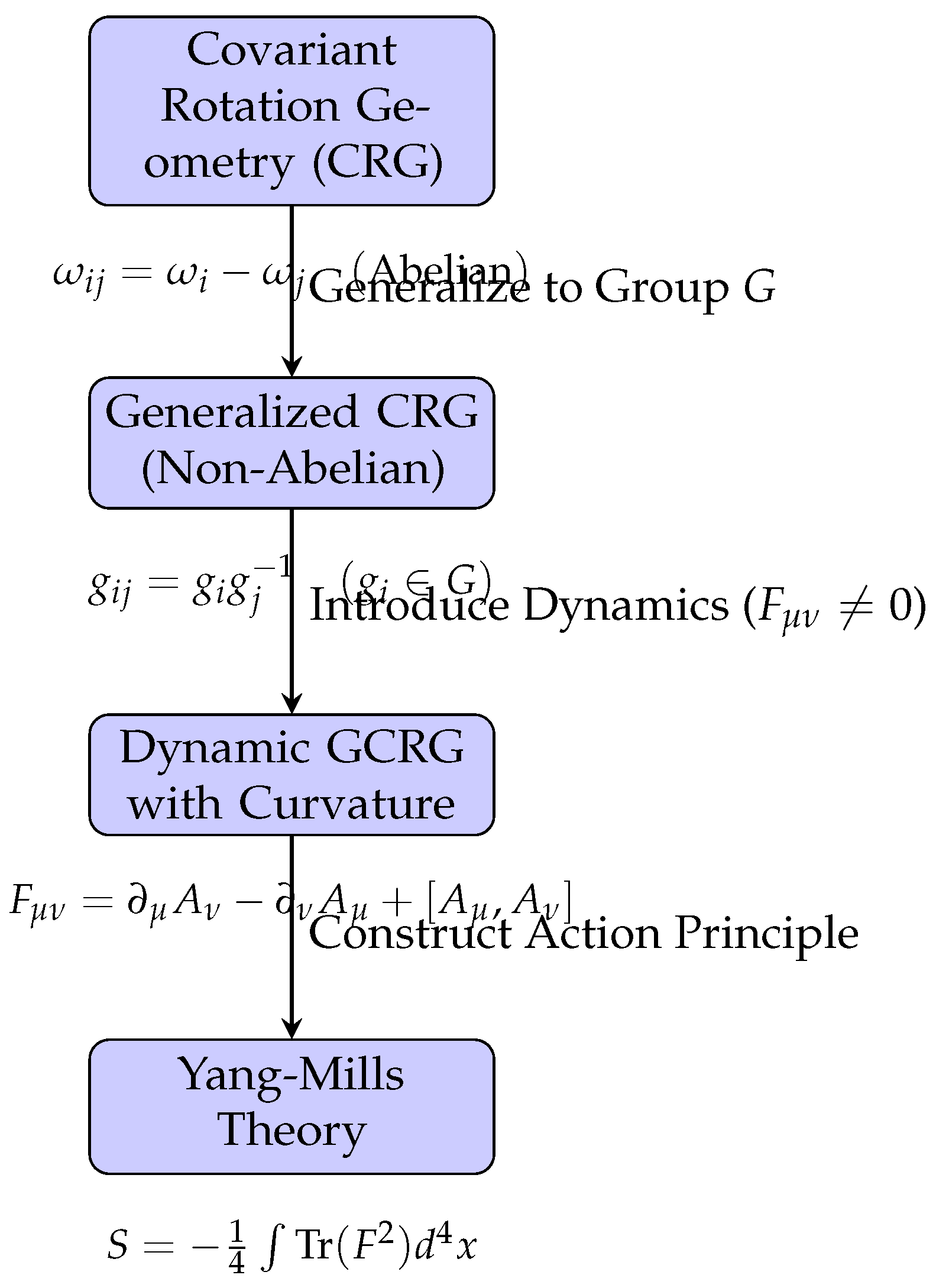

Figure 3.

The conceptual evolution from CRG to Yang-Mills Theory. The journey begins with an Abelian relational model, generalizes to a non-Abelian group structure, incorporates dynamics through curvature, and culminates in the gauge- and Lorentz-invariant action principle of Yang-Mills theory.

Figure 3.

The conceptual evolution from CRG to Yang-Mills Theory. The journey begins with an Abelian relational model, generalizes to a non-Abelian group structure, incorporates dynamics through curvature, and culminates in the gauge- and Lorentz-invariant action principle of Yang-Mills theory.

10. Physical Interpretation: Gauge Fields from a Relational Perspective

In GCRG, gauge fields acquire a profound relational interpretation that differs significantly from the traditional field-theoretic view:

10.1. Relational Nature of Gauge Fields

Theorem 18 (Relational Interpretation of Gauge Fields)

.

In GCRG, thegauge field is not a "background field" existing independently of matter, but rather a measure of dynamic inconsistency between entity relations. It quantifies how the relational structure deviates from perfect transitivity when dynamics are introduced.

10.2. Field Strength as Relational Inconsistency

Theorem 19 (Relational Interpretation of Field Strength)

.

Thefield strength represents the degree to which comparing relations between entities along different spacetime paths yields inconsistent results. This inconsistency is precisely the geometric manifestation of "interaction" in the relational framework.

Proof. Consider two paths from point i to point k: a direct path and an indirect path through j. In a flat, non-dynamical geometry, the relation would equal the composed relation . However, in a dynamical theory with interactions, these two paths may yield different results. The Wilson loop measures this inconsistency:

If , the relations are perfectly consistent (no interaction)

If , there is an inconsistency (interaction present)

In the continuum limit, this becomes the field strength , which measures the path-dependence of parallel transport. □

10.3. Gauge Symmetry as Observer Freedom

Theorem 20 (Relational Interpretation of Gauge Symmetry)

. Gauge symmetry corresponds to the freedom of choosing different observers (i.e., different entities as reference points). This is completely consistent with CRG’s "inability to distinguish who is rotating" and represents a fundamental aspect of relational ontology.

Proof. In GCRG, the local gauge transformation corresponds to changing the reference frame from entity i to a new perspective defined by . The fact that physical observables must be invariant under such transformations reflects the relational principle that no entity is intrinsically special—all relations are defined between entities, not with respect to an absolute background. □

10.4. Unification Principle

Theorem 21 (Relational Interpretation of Yang-Mills Theory)

. Yang-Mills theory = dynamic, non-Abelian, spacetime-extended covariant rotation geometry

This unification principle reveals that the fundamental interactions described by Yang-Mills theory are not mysterious "forces" acting at a distance, but rather manifestations of relational inconsistencies in the geometric structure of spacetime. The Standard Model, therefore, can be understood as a specific realization of relational ontology in the quantum regime.

11. Conclusion: A Relational Foundation for Fundamental Forces

In this paper, we have charted a path from a simple, intuitive principle—that physical reality is fundamentally relational—to the complete mathematical structure of Yang-Mills theory, the cornerstone of the Standard Model. By starting with Covariant Rotation Geometry (CRG), we have shown that the complex machinery of non-Abelian gauge theory is not an ad-hoc invention but an inevitable consequence of a consistent relational ontology extended to a dynamic, non-Abelian, and continuous spacetime.

11.1. Summary of the Derivation

Our argument proceeded in a series of logical steps, each building upon the last:

We generalized the Abelian relations of CRG to a non-Abelian group structure (GCRG) to properly account for finite rotations, revealing a framework equivalent to a principal fiber bundle.

We introduced dynamics by allowing for local inconsistencies in the relational network. This led directly to the concept of curvature, which we identified with the Yang-Mills field strength tensor, .

We established that the only action that is both gauge-invariant and Lorentz-invariant, and that penalizes relational inconsistency, is the Yang-Mills action, .

We incorporated matter fields as states attached to the entities in our relational network and showed that their interaction with the gauge field is required to maintain the relational principle of gauge invariance.

11.2. A New Perspective on Gauge Theory

This derivation recasts our understanding of fundamental interactions in a new light:

Forces as Geometry of Relations: What we call fundamental forces are manifestations of the curvature in the geometry of relations. The field strength is not an abstract field in spacetime, but a measure of how much relational paths fail to close.

Symmetry as Relational Freedom: Local gauge symmetry is not a mysterious mathematical redundancy, but the physical expression of the freedom to choose any entity as a reference point without changing the objective reality of the relations themselves.

Physics from Ontology: The structure of physical law, in this case Yang-Mills theory, emerges directly from a clear ontological postulate. This provides a powerful answer to the question of why nature is described by gauge theories.

Our work fulfills, in the domain of the Standard Model, the spirit of Einstein’s program to geometrizing physics. It suggests that the profound insight of Yang—that symmetry dictates interaction—is itself dictated by the even deeper principle that reality is relational.

11.3. Future Directions

This relational foundation for gauge theory opens exciting avenues for future inquiry:

Quantum Reality: How does this relational picture extend to the quantum realm? A path-integral formulation based on summing over relational geometries, rather than field configurations, could offer new insights into quantum gauge theory and confinement.

The Problem of Gravity: Can gravity be incorporated into this framework as the dynamics of the underlying spacetime relations, unifying it with the other forces under a single relational principle?

Emergent Spacetime: Our approach treats spacetime points as the entities to be related. A more radical vision would be to derive spacetime itself as an emergent property of a more abstract, pre-geometric relational network.

In conclusion, by taking the concept of relationality seriously, Covariant Rotation Geometry provides a compelling and intuitive foundation for the gauge structure of the universe. It transforms Yang-Mills theory from a successful but abstract mathematical description into a profound statement about the nature of physical reality itself.

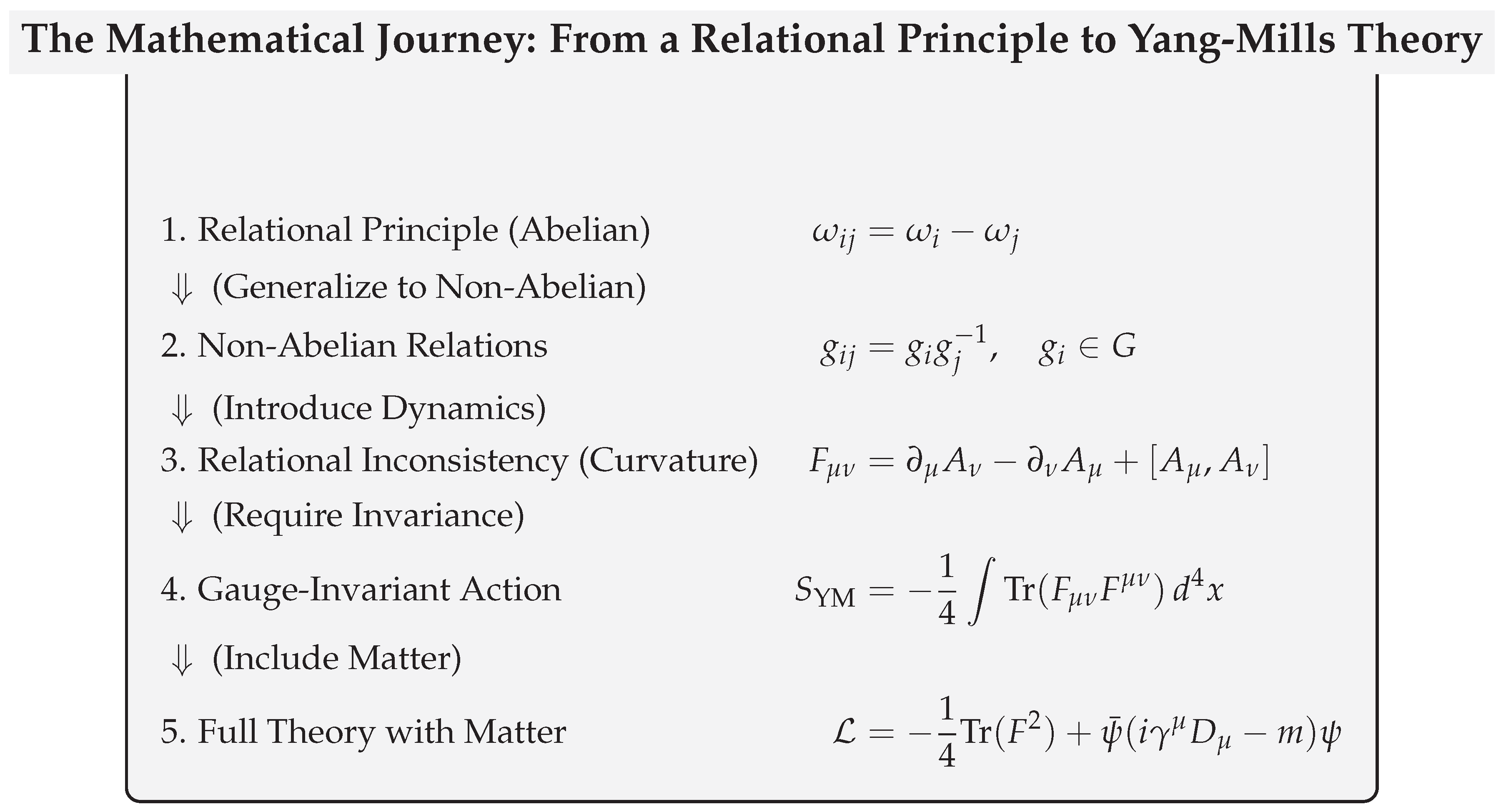

Figure 4.

A summary of the key mathematical steps in the derivation. The entire structure of Yang-Mills theory, including its interaction with matter, emerges from the progressive development of a single foundational principle of relational ontology.

Figure 4.

A summary of the key mathematical steps in the derivation. The entire structure of Yang-Mills theory, including its interaction with matter, emerges from the progressive development of a single foundational principle of relational ontology.

Covariant Rotation Geometry thus provides a pathway to the core of the Standard Model.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the foundational work in relational ontology and gauge theory that made this derivation possible. This research builds upon the deep insights into the nature of physical reality that have emerged from both geometric and field-theoretic perspectives.

References

- C.N. Yang and R.L. Mills,Conservation of Isotopic Spin and Isotopic Gauge Invariance, Physical Review, 96(1):191-195, 1954. [CrossRef]

- J.C. Baez and J.P. Huerta, An Introduction to Gauge Theory, arXiv:1410.6753, 2014.

- M. Nakahara, Geometry, Topology and Physics, Institute of Physics Publishing, 2nd edition, 2003.

- S. Weinberg, The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. 2: Modern Applications, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- L. Smolin, The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next, Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

- M.E. Peskin and D.V. Schroeder, An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory, Addison-Wesley, 1995.

- T. Frankel, The Geometry of Physics: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, 3rd edition, 2011.

- C. Rovelli, Relational Quantum Mechanics, International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 35(8):1637-1678, 1996.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).