1. Introduction

Water contamination is a major global health challenge. Pollutants from agriculture, industry, and consumer products accumulate in drinking water and aquatic ecosystems, creating exposures that span acute high-dose insults and chronic low-level accumulation, each with distinct toxicological consequences [

1,

2]. Key contaminants include heavy metals and metalloids, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs), pesticides and pharmaceuticals, engineered nanoparticles, and emerging endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) such as bisphenols and flame retardants; all notable for persistence, low-dose activity, and co-occurrence in mixtures [

3,

4]. Epidemiological studies link these exposures to cancer, neurodevelopmental impairment, cardiometabolic and immune dysfunction, and reproductive toxicity [

5,

6]. Importantly, over the last three decades, early-onset cancer incidence has risen by 79.1%, highlighting the role of environmental factors beyond genetics [

7]. Traditional toxicity testing has relied heavily on animal models and two-dimensional (2D) cultures [

8,

9]. While informative, animal studies are costly, ethically contentious, and often poorly predictive of human outcomes due to species-specific differences in physiology and metabolism [

10,

11]. 2D cultures, on the other hand, lack the cellular diversity, heterogeneity, and spatial organization of real tissues, limiting their ability to capture organ-specific responses [

12,

13]. Organoids represent advanced in vitro models for toxicological research [

14,

15]. Derived from adult (ASCs) or pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) and patient tissues, they self-organize into three-dimensional structures that recapitulate the cellular heterogeneity, spatial organization, and functional characteristics of their tissue of origin [

16,

17,

18]. The ability to establish organoids from multiple donors further enables the investigation of inter-individual variability in toxicological responses, an aspect rarely captured by conventional models [

19,

20,

21]. Recent advances in microengineering have enabled the integration of organoids into microfluidic devices, giving rise to organoid-on-a-chip platforms that allow precise regulation of the microenvironment and support inter-organ communication [

22,

23]. To further enhance physiological relevance, co-culture strategies incorporating fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells are increasingly applied, while microfluidic systems are being adapted to include vascular flow and extracellular matrix dynamics [

24,

25]. These approaches collectively improve organoid maturation, functionality, and responsiveness, strengthening their application in mechanistic toxicology and risk assessment. Importantly, organoids can also be applied to model short-term, high-dose exposures, thereby complementing the regulatory emphasis on chronic exposure scenarios and providing a platform to examine acute contaminant spikes in drinking water systems [

15].

This review synthesizes current evidence on the use of organoids to investigate cancer and disease risks from water contaminants. We critically evaluate the advantages of organoid models compared with epidemiological studies, outline the methods used for a systematic literature review, present findings across major contaminant groups, and discuss implications for regulatory guideline development.

2. Materials and Methods

To capture the state of research, we conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed literature using Scopus, while ensuring no additional, relevant articles were missed for specific topics, from Google Scholar. The Boolean query we used was: ("organoids" OR "3D culture" OR "tumor spheroid”) AND “metals” OR “trihalomethanes” OR “pesticides” OR “disinfection” OR “PFAS” OR “nanoplastics” OR “haloacetic acid” OR “cyanotoxin” OR “algal toxin” OR “microcystin” OR “cylindrospermopsin” OR “saxitoxin” OR “lyngbyatoxin” OR “anatoxin”).

The search covered publications from 2013 to 2025, reflecting the period of rapid organoid development. From the initial list, we included only studies that addressed all the following criteria: (1) Using human-derived organoids (intestine, liver, kidney, brain, bladder, or multi-organoid systems); (2) Experimental assessments of contaminant exposure relevant to drinking water; (3) Mechanistic or phenotypic outcomes linked to disease or carcinogenesis. We instead excluded (1) 2D cell line studies (unless compared directly to organoids) (2) Animal organoid studies without human relevance; and (3) Reviews, though these were considered in the broader context of the paper (e.g. for the discussion or introduction sections).

The Initial database query returned 555 publications, and after abstract/title screening and then full text review, 90 articles met the inclusion criteria. This accounts for excluding a number of studies addressing compounds that are not environmental contaminants but at the same time including papers that focused on emerging contaminants

For each study, we extracted: 1) Organoid model used 2) Water contaminants assessed, including concentrations and exposure times, along with experimental methods. 3) Results including inter-patient variation if provided 4) Biological mechanism involved. This was performed with the assistance of generative AI (Microsoft Copilot) with review and quality assurance by the authors.

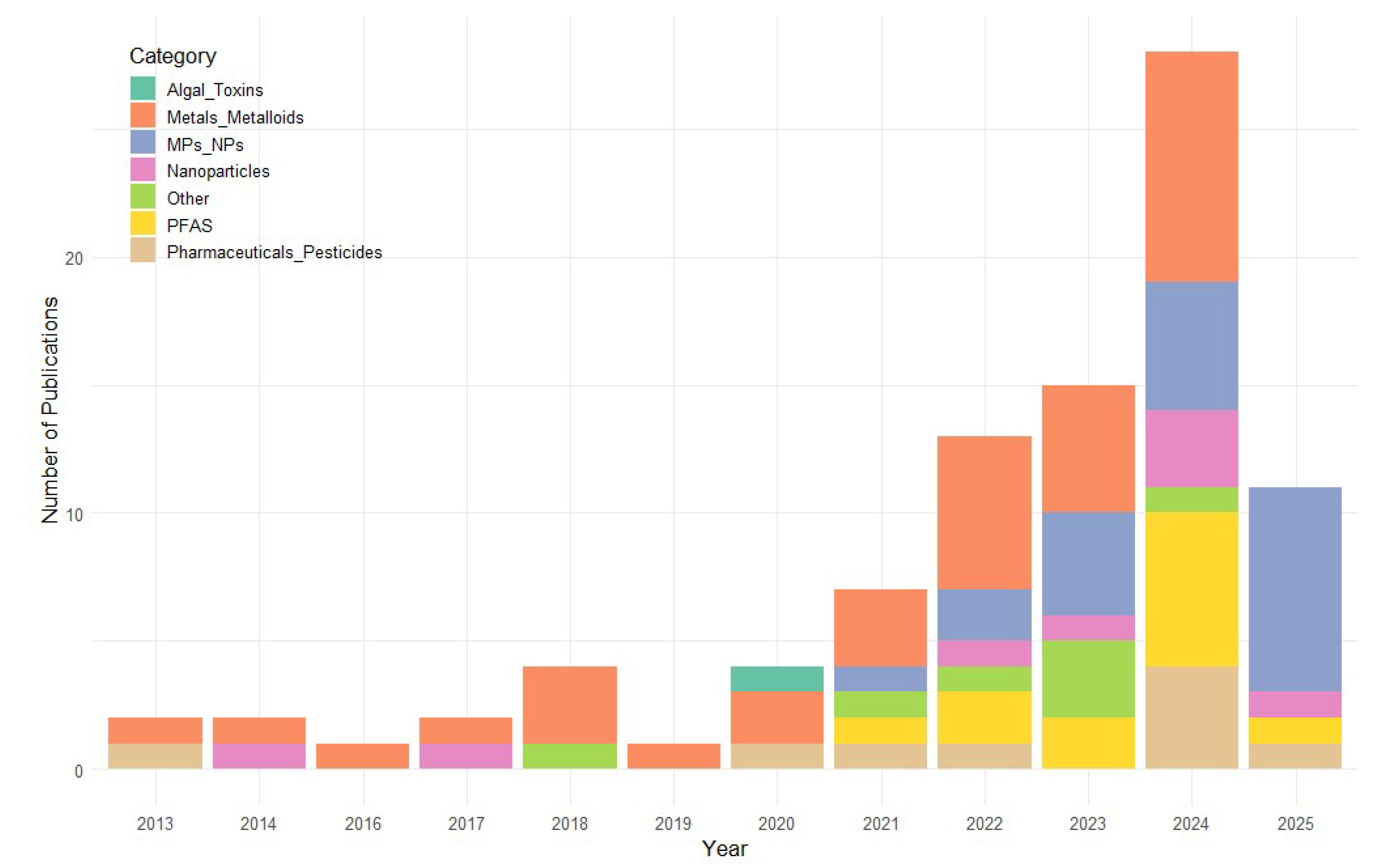

2.1. Temporal Distribution

The temporal distribution of publications on organoid-based toxicology for water contaminants demonstrates a clear upward trajectory over the past decade. From a modest output of one to two publications per year between 2013 and 2017, the field has experienced steady growth, reaching a peak of 29 publications in 2024. Although 2025 currently shows less publications, the year is not yet complete, and this number is expected to increase. This surge likely reflects both the increasing accessibility of human-derived organoid models and their recognized value for studying the mechanistic effects of environmental water contaminants, including heavy metals, microplastics, and persistent organic pollutants. In particular it can be seen that, while the number of studies on metals/metalloids increased only slightly, other less established contaminants classes, such as PFAS, MPs/NPs, pesticides and pharmaceuticals, have seen comparatively more research interest in the past five years (

Figure 1).

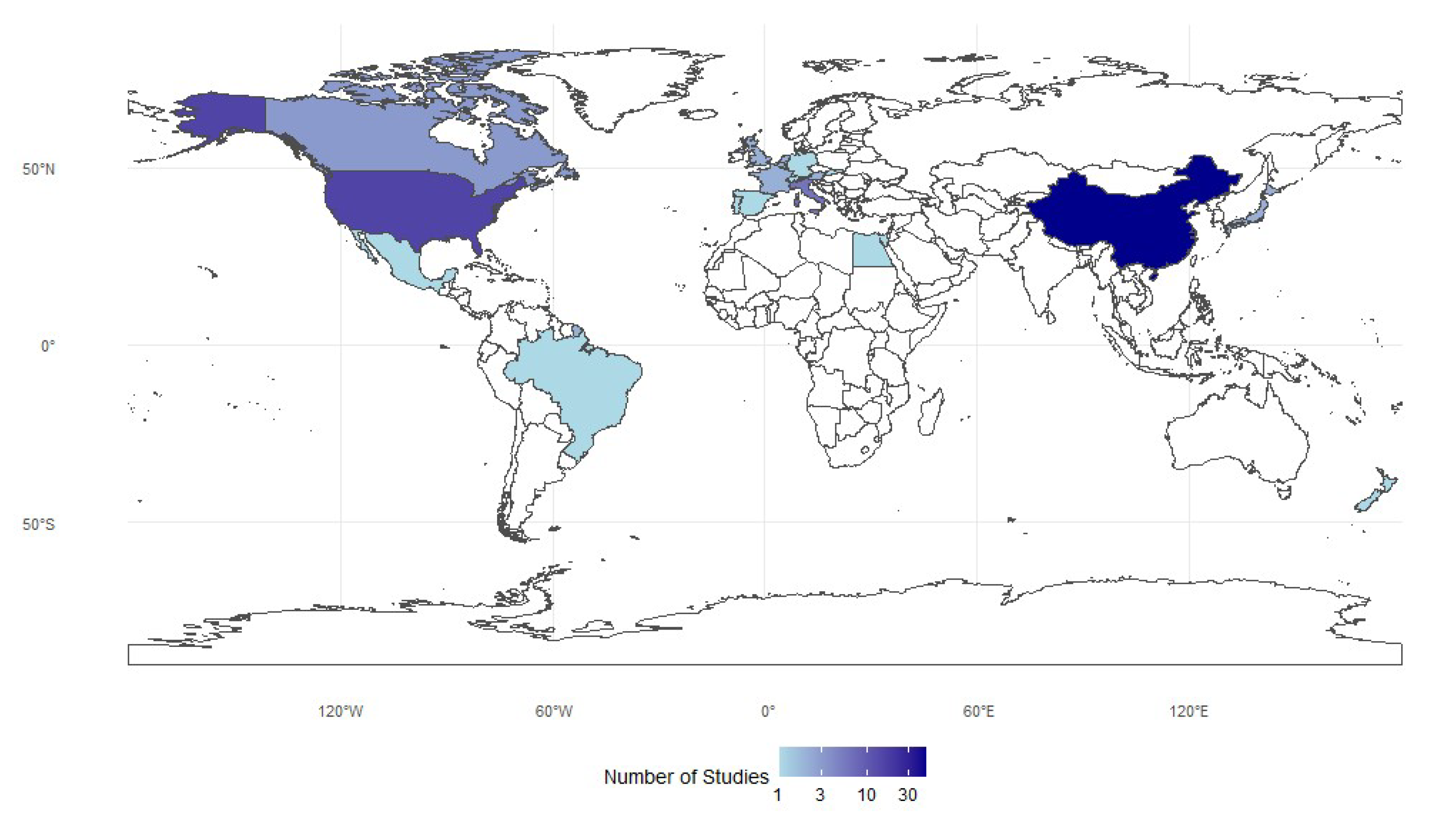

2.2. Spatial Distribution

The distribution of studies is highly uneven, with China contributing nearly half of all entries (n=46), followed by the United States (n=15) and several European countries, led by Italy (n=6). Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand add only modest representation, while Africa, South America, and much of Southeast Asia are minimally represented or absent. Overall, research is concentrated in economically developed or industrialized nations, reflecting institutional and funding disparities. A logarithmic color scale highlights these gaps, showing that a few countries dominate while many contribute little (

Figure 2).

3. Disinfection By-Products (DBPs) and Algal Toxins

DBPs are chemical compounds formed when disinfectants, such as chlorine or chloramine, react with natural organic matter in water. Over 700 DBPs have now been identified globally, and there is growing recognition that many unregulated DBPs may be way more toxic than those currently monitored [

26,

27] supporting the belief that most of current standards are outdated [

28]. Interestingly, no study meeting our search criteria, even following additional searches in Google Scholar, focused on DBPs. There seems to be a gap in organoid research studies focusing on assessing toxicity of existing and emerging DBPs at exposure levels and durations typical of disinfected potable water.

Cyanobacterial toxins represent a globally significant yet often underestimated waterborne health risk. They are among the most potent naturally occurring compounds, with acute neurotoxic and hepatotoxic effects demonstrated in animal studies and occasional confirmed human intoxications. Epidemiological evidence remains limited and inconsistent due to challenges in quantifying exposure, differentiating co-occurring hazards, and the historical absence of molecular diagnostic tools. Consequently, current guideline values are largely extrapolated from experimental toxicology rather than population-level health outcomes, underscoring both the seriousness of potential risks and the uncertainty surrounding long-term, low-dose exposure effects [

29]. Despite the opportunity, organoid research in relation to algal/cyanobacterial toxins seems to be limited. Only three related studies were identified, however two of them used cell line models so they were excluded. In the only relevant study using human brain organoids, saxitoxin (12 μg/L) synergistically amplified Zika virus–induced neural damage after 13 days, enhancing viral replication and neural progenitor apoptosis, indicating synergistic neurotoxicity [

30].

4. Metals and Metalloids

Metals and metalloids are among the most pervasive water contaminants, with well-documented links to neurotoxicity, carcinogenesis, and endocrine disruption [

31,

32].

4.1. Dose, Timing, and Mixture Effects of Heavy Metal Toxicity in Organoids

Toxic effects of heavy metals occur across a wide concentration range, from picomolar [

33] to millimolar exposures [

34], reflecting both intrinsic potency and experimental conditions. In neural organoids, micromolar doses of cadmium (Cd) or lead (Pb) were sufficient to disrupt normal development: 1 μM Cd impaired cerebral maturation [

35], while 10 μM Pb triggered premature neuronal differentiation [

36]. Mercury (Hg) and thallium (Tl) displayed even greater potency, with IC₅₀ values in the nanomolar to low micromolar range in liver and cardiac organoids [

34]. Importantly, long-term exposure to environmentally relevant levels of Cd (10–100 nM) led to persistent defects in cortical maturation [

37], showing that chronic low-dose exposures can approximate or even exceed acute high-dose toxicity.

Phenotypic outcomes varied across tissues in ways that reflected each organoid’s developmental and physiological functions. Neural models were particularly vulnerable to Cd, Pb, As, and Al, showing reduced progenitor proliferation [

38], disorganized cortical lamination [

37], and premature neuronal differentiation [

36]. Cardiac organoids exhibited impaired development and function, with Cd suppressing Wnt signaling, blocking mesodermal specification, and weakening contractility, while Tl reduced beating frequency [

34,

39]. In liver organoids, Tl induced marked cytotoxicity [

34], whereas in skeletal tissue Cd disrupted essential metal uptake, leading to extracellular matrix degradation and possible osteoarthritic changes [

40]. Mammary organoids exposed to Cd displayed impaired branching morphogenesis through HIF-1α suppression [

41], and thyroid organoids confirmed the endocrine-disrupting actions of Cd, Ni, and Hg via reduced iodide uptake [

42].

Exposure duration and developmental timing further modulated these outcomes. Acute high-dose exposures (24–72 h) often produced overt cytotoxicity, apoptosis, or cell-cycle arrest [

34,

43], while chronic low-dose exposures disrupted more subtle developmental processes, such as maintenance of progenitor pools [

37] or proper branching morphogenesis [

41]. Sensitivity was heightened during specific developmental windows: for example, Cd disrupted mesodermal specification only when exposure coincided with early cardiogenesis, whereas later stages were comparatively resistant [

39].

Combined exposures introduced additional complexity. Wang et al. [

44] showed that Cd, Pb, chromium (Cr-VI), and arsenic (As-III) produced distinct morphological changes in intestinal organoids without strong cross-interference. Co-exposure to Pb and As synergistically impaired neurogenesis by convergent inhibition of Wnt signaling and activation of autophagy [

45], while mixtures of Pb, Hg, and Cd abolished neural and glial differentiation altogether despite differing single-agent potencies[

33].

Together, these findings indicate that metal toxicity in organoids is defined not only by concentration but also by tissue context, exposure duration, developmental timing, and mixture effects.

4.2. Disrupted Pathways and Cellular Mechanisms of Heavy Metal Toxicity

At the molecular level, these studies converge on several recurrent mechanisms. Disrupted signaling pathways are central: Pb and Cd consistently inhibited Wnt/β-catenin signaling, impairing progenitor proliferation and differentiation [

36,

39], while Al exposure suppressed the Hippo–YAP1 pathway, skewing cortical lineage decisions [

38]. Heavy metals also altered ion homeostasis: Cd, Pb, and As upregulated metallothioneins and metal transporter genes [

43,

45], reflecting compensatory stress responses but also contributing to zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu) imbalance. Mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis, and oxidative stress were frequently implicated [

33,

34], as were epigenetic changes such as repressive histone methylation [

39]. Tissue-specific mechanisms were also apparent; Cd antagonized essential metal uptake in chondrocytes [

40], suppressed HIF-1α in mammary organoids [

41], and disrupted ciliogenesis in cerebral organoids [

43]. Notably, co-exposures triggered convergence of pathways: Pb and As jointly inhibited Wnt signaling while enhancing autophagy, amplifying apoptosis and migration defects [

45]. These mechanistic insights suggest metals act not only as direct cytotoxins but as developmental reprogrammers, perturbing key regulatory nodes that determine tissue fate and function.

An overview of the specific contaminants, organoid models, exposure ranges, and associated phenotypes is provided in

Table 1.

5. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

PFAS are a large class of synthetic fluorinated compounds widely used in industrial and consumer products for their surfactant and water-repellent properties. Because of their high environmental persistence and bioaccumulative potential, PFAS such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) are often termed “forever chemicals” [

47]. Organoid models have provided new insights into the tissue-specific and dose-dependent toxicity of these compounds across physiological systems.

5.1. Dose, Timing, and Mixture Effects of PFAS Toxicity in Organoids

Chronic exposure of human prostate stem-progenitor cells to 10 nM PFOA or PFOS for 3–4 weeks increased spheroid number and size, consistent with enhanced stem-cell self-renewal and a potential preneoplastic transition [

48]. Mammary epithelial organoids exposed to 0.01–500 µM PFOA for up to 12 days exhibited dose- and time-dependent architectural disorganization and reduced intracellular motility, with significant effects at ≥ 100 µM [

49]. In liver organoids, 100–1000 µM PFOS or PFOA for 96 h caused acute hepatotoxicity marked by nuclear pyknosis and caspase-mediated apoptosis, while short-chain PFAS produced only mild functional alterations [

50]. Transcriptomic profiling of human hepatocyte and liver spheroids revealed bioactivity at 10–100 µM, with long-chain PFAS suppressing lipid and steroid metabolism, and short-chain analogs such as perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) enhancing fatty-acid and cholesterol biosynthesis [

51,

52]. Thyroid cell spheroids exposed to 0.01–1000 ng/mL PFAS displayed altered viability, chemokine induction, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related gene expression at environmentally relevant concentrations [

53].

Across systems, both short- and long-term exposures were deleterious but with distinct manifestations. High-dose, short-term exposure (24–96 h) primarily caused overt cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and hepatocellular collapse [

50,

54], whereas prolonged low-dose exposure induced more insidious effects, including persistent reprogramming of stem-progenitor behavior (3–4 weeks) [

48], loss of epithelial architecture (12 days) [

49,

55], and progressive metabolic dysregulation (10–14 days) [

51]. Liver models consistently showed steatosis, mitochondrial damage, and inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis resembling classical hepatotoxicants [

52,

56]. Reproductive and endocrine organoids exhibited structural instability, EMT activation, and pro-tumorigenic chemokine signaling [

49,

53,

55], while cerebral organoids revealed neuronal vulnerability and transcriptomic signatures associated with neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment [

57]. Studies of PFAS mixtures generally followed a concentration-addition pattern: longer-chain PFAS exhibited greater potency, but no strong synergism or antagonism was detected [

52,

54,

58]. In thyroid organoids, PFHxA and PFOA produced overlapping reductions in viability and activation of tumor-promoting pathways, whereas the short-chain replacement C6O4 showed minimal activity [

53]. However, PFAS mixtures induced complex, cell-type-specific transcriptional responses in cerebral organoids, suggesting that additive models may underestimate subtle neurodevelopmental risks.

5.2. Disrupted Pathways and Cellular Mechanisms of PFAS Toxicity

At the molecular level, PFAS toxicity converges on pathways regulating lipid metabolism, nuclear receptor activity, and cellular stress responses. Long-chain PFAS such as PFOS, perfluorodecane sulfonate (PFDS), and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) consistently downregulated genes controlling cholesterol and fatty-acid metabolism through repression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α/δ (PPARα/δ) and sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factors 1/2 (SREBF1/2) [

51,

52,

54]. In contrast, short-chain compounds like PFHxA upregulated fatty-acid oxidation and cholesterol biosynthesis, revealing chain-length-dependent divergence in metabolic effects. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and steatotic changes were frequently observed in hepatic organoids [

56], whereas in reproductive models PFAS induced EMT-associated transcription factors and pro-inflammatory chemokines such as CXCL8 and CCL2, promoting a tumor-supportive microenvironment [

53]. Neural organoids exhibited impaired neuronal differentiation and survival, potentially through synaptic dysregulation and Alzheimer’s disease-related signaling alterations [

57]. Across organoid systems, recurrent features included apoptosis, cytoskeletal remodeling, and metabolic stress, indicating that PFAS act as systemic metabolic disruptors rather than simple cytotoxins.

A summary of specific PFAS compounds, organoid models, exposure ranges, and associated phenotypic effects is presented in

Table 2.

6. Micro- and Nanoplastics (MNPs)

MNPs are small plastic fragments (<5 mm and <100 nm, respectively) generated through environmental degradation of larger polymers or direct industrial use. Because of their persistence, surface reactivity, and capacity to adsorb other pollutants, MNPs have become emerging contaminants of global concern [

59]. Organoid systems provide a physiologically relevant platform to assess their concentration-dependent and tissue-specific toxicities.

6.1. Dose, Timing, and Mixture Effects of MNPs Toxicity in Organoids

Across organoid systems, adverse effects generally emerged in the low–mid µg/mL range, with thresholds shaped by tissue context, particle chemistry, and aging state. Cardiac organoid-on-chip models showed contractile dysfunction and fibrosis at 5–20 µg/mL, with pronounced hypertrophic remodeling above 60 µg/mL, accompanied by increased brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and cardiac troponin T (cTnT) [

60,

61,

62]. Brain organoids typically required 100–200 µg/mL to induce mitochondrial injury and impaired neurogenesis, though developmental-stage models responded at 10–25 µg/mL [

63,

64,

65]. Intestinal organoids displayed broad vulnerability: reduced proliferation at 0.05 µg/mL [

66,

67], metabolic and mitochondrial alterations within 10–50 µg/mL [

68,

69], and immune dysregulation [

68,

70]. Liver organoids were highly responsive to aged particles, with acute injury and oxidative stress at ng/mL concentrations, and lipid/metabolic dysregulation, ferroptosis, and altered transporter expression at higher exposures [

71,

72,

73]. Renal organoids developed nephron-patterning defects and apoptosis at environmentally relevant doses [

74,

75], and pulmonary systems showed oxidative stress and epithelial remodeling [

76,

77,

78]. Overall, pristine polystyrene (PS) required higher concentrations than aged or chemically modified particles to induce comparable damage, emphasizing the role of environmental weathering.

Exposure duration critically modulated outcomes: acute high doses caused rapid injury [

63,

64,

65,

76,

77,

78], whereas repeated low-level or chronic exposure drove progressive structural and functional decline (e.g., sustained contractile impairment in cardiac models [

60,

61]), disrupted differentiation trajectories in intestine and liver [

66,

72], and heightened developmental susceptibility, where brief early exposures irreversibly altered lineage specification in cardiac, renal, and neural organoids [

62,

65,

75]. Recent organoid-on-chip work revealed low-dose sensitivity. Cheng et al., (2025) [

79] used a liver–heart organoid-on-a-chip to test polypropylene micro/nanoplastics (PPs), finding that 6–600 ng/mL exposures produced reduced cardiac contractility and hepatic stress responses, indicating cross-organ cardio-hepatic toxicity at environmentally relevant levels.

Co-exposure studies show that MNPs rarely act alone but interact with other pollutants. Aged polystyrene microplastics (PSMPs) complexed with chromium (Cr, 20 ppm) intensified intestinal organoid toxicity, inducing ROS accumulation, barrier disruption, pyroptosis, and increased microbial susceptibility [

80]. Similarly, co-exposure of neural retina organoids to polystyrene nanoparticles (PS-NPs) and cadmium chloride enhanced apoptosis, axonal disorganization, and neurodevelopmental defects [

81]. Collectively, organoid studies confirm that MNPs act as vectors and amplifiers of co-contaminant toxicity, implying that environmentally relevant mixtures may be substantially more harmful than single-agent exposures.

6.2. Disrupted Pathways and Cellular Mechanisms of MNPs Toxicity

Despite diverse tissue outcomes, studies converge on a common cascade of reactive-oxygen-species (ROS) generation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and disturbed calcium (Ca²⁺) homeostasis, which then trigger tissue-specific signaling. In neural organoids, MNPs suppress Wnt/β-catenin and disrupt neuroactive-ligand–receptor signaling, leading to defective neuronal differentiation [

63,

65]. In the intestine, Notch hyperactivation drives progenitor imbalance, while PI3K–AKT–mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition promotes autophagy and necroptosis; transcriptomic data reveal accompanying metabolic rewiring [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. Hepatic organoids show multiple layers of redox and metabolic stress. UV-aged polypropylene (aPP) at 75 ng/mL suppressed NADH dehydrogenase complex I, decreased ATP, and disrupted homocysteine (Hcy) and cysteine/methionine metabolism, reducing cysteine and glutathione (GSH) pools and weakening antioxidant defense [

82]. Complementary findings from Cheng et al., (2025) [

79] identified reductive stress with elevated NADH, GSH, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, implicating FGF21-mediated liver–heart signaling in systemic toxicity.Co-exposure mechanisms further illustrate MNP-driven signaling disruption. PSMP–Cr complexes modified surface charge and wettability, enhancing particle–cell interactions and oxidative stress in instestinal models [

80]. Hou et al. (2022) [

83] demonstrated that intestinal organoids preferentially accumulated PS-NPs in secretory cell lineages via clathrin-dependent endocytosis, and blocking this pathway reduced both uptake and inflammation, suggesting a mechanistic route for targeted intervention. While in neural retina orgnaoids, combined PS-NP and cadmium exposure perturbed MAPK, PI3K–AKT, Ca²⁺, and Wnt pathways, amplifying metal-induced developmental neurotoxicity in [

81].

In other systems, pulmonary organoids exposed to PS-NPs exhibited DNA damage and defective repair mechanisms [

76], whereas hepatic models displayed iron dysregulation–linked ferroptosis [

71]. Transcriptomic analyses further highlighted immune and inflammatory responses, including downregulation of interferon-inducible factor 6 (IFI6) in gut-on-chip systems [

70] and suppression of chemokine signaling in intestinal organoids [

68]. Across tissues, apoptosis, autophagy, and cytoskeletal disorganization recur as final outcomes. Collectively, these findings indicate that mitochondrial and redox stress initiate toxicity, while downstream signaling, metabolic, inflammatory, and cell-fate alterations determine tissue-specific pathologies.

A summary of the studied particle types, organoid systems, exposure conditions, and resulting phenotypic and mechanistic outcomes is presented in

Table 3.

7. Pesticides and Pharmaceuticals

Pesticides and pharmaceuticals represent chemically diverse but biologically active classes of contaminants that frequently co-occur in water and soil, raising concern for chronic low-dose human exposure. Although their intended molecular targets differ, from pest-specific enzymes to therapeutic receptors, many share convergent toxicological features, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and developmental pathway disruption [

84,

85].

7.1.1. Neonicotinoids

Mariani et al. (2024) [

86] provided evidence that neonicotinoids, such as imidacloprid (IMI), clothianidin, and dinotefuran, at concentrations reflecting estimated human dietary intake, compromise neuronal viability in both rodent and human-derived central nervous system (CNS) models. Notably, IMI exerted the strongest effects, altering synaptic protein expression and inducing microglial activation in mouse fetal brain and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cortical organoids. The exposure durations were acute to subacute, yet already sufficient to elicit neurodevelopmental toxicity, suggesting that even relatively low, chronic exposures could be harmful. Disruption of synaptic integrity and immune–neural crosstalk emerged as primary contributors to these effects.

7.1.2. Antimicrobials: Triclosan and Triclocarban

Intestinal toxicity of triclosan (TCS) and triclocarban (TCC) were demonstrated in mouse small intestinal organoids at 1–10 μM over 48–72 h, supported by in vivo experiments [

87]. TCC was more potent, depleting Lgr5-positive (Lgr5⁺) stem cells and impairing organoid budding, thereby affecting epithelial renewal. Importantly, even short-term exposure disrupted nutrient absorption and increased susceptibility to inflammatory stimuli such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and dextran sodium sulfate (DSS). Wnt/β-catenin signaling suppression was a key mechanistic driving the loss of regenerative capacity, an effect reversible by pharmacological activation of the pathway.

7.1.3. Glyphosate-Based Herbicides (GBHs)

Sun et al. (2024) [

88] examined human cardiac organoids exposed to glyphosate (0.1–10 µg/mL) and its surfactant co-formulant polyoxyethylene tallow amine (POEA; 0.033–3.333 µg/mL) during 16 days of differentiation. While glyphosate alone induced mild epicardial hyperplasia, POEA markedly impaired contractility, induced apoptosis, and suppressed cardiomyocyte specification. Combined exposure replicated the POEA phenotype, identifying the surfactant as the principal toxicant. Disruption of WNT/bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling and lipid metabolism was involved in the observed cardiotoxicity.

7.1.4. Fungicides: Mancozeb and ETU

Mancozeb (≥3 μg/mL) and its metabolite ETU (≥300 μg/mL) impair embryo attachment in human primary endometrial epithelial cell (EEC) spheroids after 48 h [

89]. Mancozeb at 10 μg/mL reduced viability, while sub-cytotoxic levels disrupted adhesion molecules, impairing trophoblast–endometrial interactions. Transcriptomic profiling identified broad transcriptional reprogramming (>150 genes) involving endocrine and adhesion pathways, suggesting that even low-dose exposures can perturb reproductive signaling networks critical for embryo implantation.

7.1.5. Chlorpyrifos

Human brain organoids were used to investigate chlorpyrifos (CPF; 100 µM) and its oxon metabolite in a model of chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 8 heterozygosity (CHD8⁺/⁻), relevant to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [

90]. CPF exposure (short-term: 24 h) intensified metabolic and neurotransmitter abnormalities in CHD8⁺/⁻ organoids but not in wild type. Reduced CHD8 protein levels and altered neurotransmitter metabolism were central to this response, highlighting how pesticides may modulate genetic susceptibility even at sub-toxic concentrations.

7.1.6. Vinclozolin

González-Sanz et al. (2020) [

91] reported that vinclozolin (10–200 µM, 6 days) impaired meiotic differentiation in fetal ovarian organoids, with a metabolic shift toward glycolysis. Inhibition of androgen signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction accounted for the observed reproductive toxicity, illustrating the sensitivity of germline differentiation to antiandrogenic agents at moderate concentrations.

7.1.7. Broad Neurotoxic Screening

A screening of 16 pesticides in human iPSC-derived neural spheroids revealed neurotoxicity at 3–10 μM after 24–72 hours [

92]. Effects intensified with longer exposure, coinciding with altered calcium oscillations and disturbances in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) and glutamatergic signaling. The findings establish calcium signaling perturbation as a sensitive marker of pesticide-induced neurodevelopmental disruption.

7.1.8. Binary Pesticide Mixtures

Combined exposure to imidacloprid (30 μM) and lambda-cyhalothrin (6 μM) was explored in human glioma neurospheroids [

93,

94]. Even 24-hour co-exposure caused cytotoxicity, morphological degeneration, and proteomic alterations. Dysregulation of mitochondrial function, mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK), and calcium signaling was evident. Proteomic adductomics revealed covalent modification of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMK2) and annexin A1 (ANXA1), consistent with oxidative and cytoskeletal stress. Mixture exposures consistently produced greater toxicity than individual compounds, emphasizing the need for combinatorial testing in neurotoxicity assessment.

7.1.9. Pharmaceuticals

Rodrigues et al. (2022) [

95] investigated doxorubicin (DOX, 1–60 µM, 24–72 h) in human intestinal organoids, revealing dose- and time-dependent gastrointestinal toxicity, with colonic organoids showing the highest sensitivity. Mitochondrial complex I inhibition, reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and suppression of WNT/retinoic acid signaling were implicated, accompanied by tissue-specific metabolic reprogramming between glycolytic and one-carbon metabolism.) Another study using retinal organoids for pharmaceutical toxicity testing found that digoxin (40 nM), thioridazine (135 µM), and sildenafil (225 µM; 7 days) induced photoreceptor and retinal ganglion cell loss, whereas ethanol (500 mM) and methanol (32 mM) caused milder structural disorganization. Across compounds, unfolded protein response (UPR) activation, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) signaling, α-crystallin B chain (CRYAB) upregulation, and caspase-3 activation represented shared molecular hallmarks of retinal injury [

96].

7.2. Disrupted Pathways and Cellular Mechanisms of Pesticide and Pharmaceutical Toxicity

Across organoid systems, pesticide and pharmaceutical toxicity converges on a limited set of molecular perturbations. Neurotoxicants, including neonicotinoids, organophosphates, and pyrethroid mixtures, consistently impaired neuronal differentiation and synaptic integrity through calcium signaling disruption, MAPK/ERK pathway alteration, and GABAergic/glutamatergic imbalance, while also triggering microglial activation and immune–neural crosstalk [

86,

92,

93,

94]. Cardiotoxic compounds, such as glyphosate-based herbicides (GBHs) and surfactant co-formulants, suppressed WNT/BMP signaling, impaired lipid metabolism, and induced apoptosis, reflecting developmental vulnerability during cardiomyocyte specification [

88]. Epithelial organoid models exposed to antimicrobials showed Wnt/β-catenin suppression leading to impaired regeneration and barrier maintenance [

87]. Endocrine disruptors such as vinclozolin and fungicides like mancozeb further perturbed androgen and adhesion signaling and induced mitochondrial dysfunction during gametogenesis [

89,

91]. At higher exposures, chemotherapeutics and psychoactive drugs elicited mitochondrial complex I inhibition, ROS accumulation, and unfolded protein response (UPR) activation, indicating that diverse xenobiotics converge on shared stress-response pathways [

95,

96]. Together, these findings highlight that despite structural and functional heterogeneity, most pesticides and pharmaceuticals converge on mitochondrial and signaling network disruption, compromising energy metabolism, developmental patterning, and tissue integrity across organoid models.

A summary of the studied compounds, organoid models, exposure conditions, and the resulting phenotypic and mechanistic outcomes is presented in

Table 4.

8. Nanoparticles (NPs)

NPs encompass a broad spectrum of engineered and environmentally derived materials with at least one dimension below 100 nm, widely used in electronics, cosmetics, and food products. Their increasing release into the environment and ability to penetrate biological barriers have raised concern about long-term human exposure [

99].

8.1. Dose, Timing, and Mixture Effects of Nanoparticle Toxicity in Organoids

Organoid studies reveal that NP toxicity occurs across a broad concentration spectrum, reflecting differences in chemical composition, morphology, and biological context. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were among the most potent, inducing proliferation–apoptosis imbalance, ciliary disruption, and cytoskeletal damage at 0.1–0.5 μg/mL after 5–7 days in human cerebral organoids. At these concentrations, AgNPs caused persistent developmental perturbations and apoptosis, whereas lower doses transiently enhanced proliferation before sensitizing neurons to later stress [

100,

101]. Moss-synthesized AgNPs exhibited a higher threshold (6–12 μg/mL, 24 h) in mesenchymal stem cell spheroids [

102], suggesting that synthesis method and biological model strongly influence toxicity levels. Gold-based nanomaterials displayed organ-specific effects that depended on both concentration and structure. Poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers induced mild nephrotoxicity and inflammatory stress in kidney organoids at ≥0.675 mg/mL (48h) [

103], while gold nanobranches triggered hepatic mitochondrial and cytoskeletal damage at ≤200 μg/mL (24 h) [

104]. Therefore, particle shape emerged as a critical determinant of toxicity than chemical composition. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) were cytotoxic to human brain organoids at 64 μg/mL (24 h), producing nuclear fragmentation and micronuclei formation [

105]. In contrast, titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO₂ NPs) exhibited pronounced intestinal toxicity at much lower levels (20 μg/mL) [

106,

107]. Chronic dietary exposure to TiO₂ NPs for 12 weeks disrupted glucose homeostasis in vivo [

106], while 24-day organoid exposure impaired intestinal stem cell function [

107].

Overall, exposure duration was a critical modulator of toxicity, suggesting that long-term, low-dose contact [

100,

101,

106,

107] can be more detrimental than short, high-dose exposure [

103,

105]. A cross nanoparticle types, toxicity reflected tissue-specific sensitivity: neural organoids showed the lowest tolerance (AgNPs, ZnO NPs) [

100,

101,

102,

105], intestinal organoids were particularly vulnerable to TiO₂ NPs [

106,

107], and hepatic or renal organoids displayed mitochondrial and cytoskeletal injury under gold nanostructures or dendrimers [

103,

104].

8.2. Disrupted Pathways and Cellular Mechanisms of Nanoparticle Toxicity

Despite diverse particle compositions, several convergent mechanisms underlie NP-induced toxicity across organoid models. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction represent the primary initiating events for silver, gold, and zinc nanoparticles [

102,

104,

105]. These processes lead to energy depletion, redox imbalance, and subsequent activation of apoptotic cascades.

Autophagy impairment emerged as a sensitive molecular hallmark: ZnO NPs inhibited LC3B-mediated autophagy [

105], while AgNPs dysregulated autophagic flux in neural organoids; pharmacological autophagy inhibition further intensified toxicity [

101]. In intestinal organoids, TiO₂ NPs disrupted Wnt/β-catenin signaling, suppressed stem cell renewal, and downregulated genes controlling differentiation and hormone biosynthesis, leading to impaired enteroendocrine differentiation, reduced glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) secretion, and stem cell depletion [

106,

107]. Brain organoids displayed additional vulnerability through activation of NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling, calcium homeostasis disruption, and cytoskeletal collapse following AgNP exposure [

100,

101]. Hepatic organoids exposed to gold nanobranches exhibited ROS-driven mitochondrial damage and disordered cytoskeletal networks [

104].

Together, these mechanisms illustrate that nanoparticles target fundamental cellular stress and survival pathways, while secondary interference with developmental and lineage-specific signaling (e.g., Wnt, NF-κB, Nrf2) shapes tissue-selective phenotypes.

A summary of nanoparticle types, organoid systems, exposure parameters, and corresponding phenotypic and mechanistic outcomes is presented in

Table 5.

9. Other emerging contaminants

Emerging contaminants, including endocrine disruptors (bisphenols, phthalates), pesticides, pharmaceuticals, microplastics, and nanoparticles, are increasingly detected in surface, ground, and drinking waters at trace concentrations, largely due to incomplete removal during wastewater treatment and ongoing discharge from agricultural, industrial, and urban sources [

108]. Their presence in aquatic systems raises significant concern, since many of these compounds can cross biological barriers, accumulate through trophic levels, and act additively or synergistically under chronic exposure [

109]

9.1. Dose, Timing, and Mixture Effects of Emerging Contaminant Toxicity in Organoids

Toxic thresholds across these chemical classes span a wide range, depending on compound potency and organoid model. Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) induced necrosis in bovine mammary epithelial organoids only at high experimental doses (15–35 µL, 8–48 h) [

110]. In contrast, bisphenols and phthalates, as potent endocrine disruptors, acted at far lower concentrations. Bisphenol S (BPS) inhibited neuronal differentiation in cerebral organoids at 100 nM (14 days) [

111], while bisphenol A (BPA) analogues impaired cardiomyocyte contractility and electrical activity at 1–20 nM [

112,

113], extending to altered morphogenesis in mammary and prostate organoids at 1–15 nM, values consistent with human exposure ranges [

114,

115]. In contrast, phthalates and flame retardants (e.g., TBBPA, DBDPE) disrupted thyroid [

42] or retinal organoids [

116,

117] at micro- to millimolar concentrations, underscoring class-dependent potency.

Organ-specific responses reflected physiological susceptibility. Mammary organoids exposed to AFB1 underwent necrosis, raising implications for milk contamination and breast carcinogenesis [

110]. Thyroid organoids displayed reduced iodide uptake and hormone synthesis under phthalate or organophosphate flame retardant (OPFR) exposure, aligning with known endocrine-disrupting activity [

42]. Neural organoids exposed to BPS or flame retardants showed reduced neural progenitor proliferation and altered calcium oscillations, consistent with developmental neurotoxicity [

92,

111]. Retinal organoids exhibited relative resilience to acute pesticide or pharmaceutical exposures but remained vulnerable to brominated flame retardants and bisphenols [

116,

117]. Placental trophoblast organoids exposed to the EHDPP demonstrated impaired differentiation and reduced hormone secretion, linking exposure to implantation failure and fetal growth restriction [

118]. In cardiac organoids, chronic exposure to BPAF (20 days, nanomolar levels) suppressed contractility and induced electrophysiological irregularities [

112].

Temporal analyses revealed that exposure duration modulates toxicity as much as concentration. Acute bisphenol exposure (minutes to hours) already prolonged action potential duration and impaired ion flux in cardiac models [

113], whereas chronic exposure induced structural remodeling and reduced beating strength [

112]. Long-term exposure to bisphenols or flame retardants (up to 63 days) altered retinal development and inflammatory signaling [

116,

117]. Similarly, EHDPP elicited trophoblast differentiation defects only after sustained exposure [

118]. These findings collectively indicate that acute assays may underestimate the impact of persistent, low-level exposure, especially in endocrine and developmental systems.

Evidence of interactive or compounding effects is emerging. Co-exposure of BPA with polystyrene microplastics synergistically intensified hepatotoxicity in liver organoids, marked by mitochondrial damage, lipid accumulation, and inflammatory gene activation [

119]. While combined pesticides and pharmaceuticals exhibited only mild additive effects, flame retardants and bisphenols consistently enhanced overall toxicity [

97]. Trophoblast organoid studies further suggest that physiological conditions such as maternal metabolism or inflammation can magnify chemical effects [

118]. Together, these findings highlight that realistic environmental exposures, typically involving chemical mixtures rather than isolated agents, pose greater biological risks than single-compound studies suggest.

9.2. Disrupted Pathways and Cellular Mechanisms of Emerging Contaminant Toxicity

Despite the chemical diversity, several convergent molecular pathways emerge across organoid models. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis represent central mechanisms shared by AFB1, bisphenols, and microplastic co-exposures [

110,

119]. Endocrine disruptors such as phthalates and OPFRs additionally targeted thyroid hormone synthesis pathways, specifically inhibiting sodium/iodide symporter (NIS) activity, suppressing thyroperoxidase (TPO) and thyroglobulin (TG) expression, and downregulating cAMP signaling. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) perturbed the Akt/FoxO3a/NIS axis, further impairing iodide uptake [

42].

In neural and retinal organoids, BPS disrupted Wnt signaling and lipid metabolism, while flame retardants altered calcium-dependent excitatory signaling without overt cytotoxicity [

92,

111,

116]. Cardiac models exposed to BPAF showed decreased expression of SERCA2a and Cav1.2, leading to dysregulated Ca²⁺ handling and reduced contractility [

112,

113]. Retinal organoids exposed to bisphenols upregulated TNF and IL-17 inflammatory pathways [

116], whereas trophoblast organoids treated with EHDPP exhibited impaired proliferation and differentiation through IGF1R binding and PI3K–Akt pathway suppression [

118].

Together, these data indicate that while generic stress responses dominate across contaminants, each chemical class also triggers tissue-selective molecular disruptions, notably within hormonal, calcium, and PI3K–Akt regulatory networks, that account for organ-specific vulnerability patterns observed in organoid models.

A summary of contaminant types, organoid systems, exposure parameters, and corresponding phenotypic and mechanistic outcomes is presented in

Table 6.

10. Organoid-Based Experimental Evidence to Refine Water Quality Standards

Patient-derived and stem cell–derived organoids capture tissue- and development-specific toxic responses that are often missed by conventional assays, providing a translational bridge between in vitro findings and human health protection. As regulators revisit drinking-water limits (e.g., the U.S. EPA’s 2024 PFAS MCLs) and WHO guidance values, organoid data can help identify sub-cytotoxic, functional perturbations at environmentally relevant concentrations. Recent reviews highlight organoids’ sensitivity to endocrine, neurodevelopmental, and cardiotoxic effects across contaminant classes, supporting their use alongside epidemiology and animal studies when deriving health-protective thresholds [

15,

120]. Together, these platforms offer mechanistic and dose–response insights necessary for modernizing water quality standards.

10.1. Metals and Metalloids

The concentrations of heavy metals that elicit toxicity in organoid models are gen-erally higher than the thresholds set by major drinking water guidelines, including those from the EPA [

121], WHO [

122], and Australian authorities [

123]. For instance, cadmium disrupted neurodevelopment in cerebral organoids at 10–100 nM (0.01–0.1 µM), while the EPA’s Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) is 0.005 mg/L (≈0.044 µM), WHO’s is 0.003 mg/L (≈0.027 µM), and Australia’s is 0.002 mg/L (≈0.018 µM). Lead induced premature neuronal differentiation at 10 µM, yet the EPA sets an action level of 0.015 mg/L (≈0.072 µM), while both WHO and Australian guidelines recommend 0.01 mg/L (≈0.048 µM). Mercury showed toxicity at nanomolar to low micromolar levels, with EPA’s MCL at 0.002 mg/L (≈0.01 µM), WHO’s at 0.006 mg/L (≈0.03 µM), and Australia’s at 0.001 mg/L (≈0.005 µM). Thallium was found to have a IC50 of 13.5 µM in liver organoids and 1.35 µM in cardiac organoids (

Table 1), however it has an EPA MCL of 0.002 mg/L (≈0.01 µM), far below the concentrations causing 50% toxicity in organoid models, which is expected because guidelines are designed for chronic lifetime exposure in humans, whereas organoid IC50 reflects acute in vitro toxicity. However, the fact that cardiac organoid function is affected at low micromolar levels suggests that even sub-IC50 exposures could have functional effects, highlighting potential developmental or sensitive-window risks not fully captured by standard MCLs. Moreover, the synergistic effects observed in co-exposures (e.g., Pb + As) suggest that single-metal guidelines may underestimate real-world toxicity (

Table 1).

10.2. PFAS

Organoid studies indicate that PFAS can induce toxic effects at extremely low concentrations, sometimes approaching regulatory thresholds. Human prostate stem progenitor cells, for instance, exhibited functional changes at 10 nM (~4 ppt) PFOA or PFOS, while transcriptomic alterations were observed at ~20 nM (~8 ppt), demonstrating that sub-cytotoxic exposures can reprogram cellular metabolism and signaling (

Table 2). By comparison, the U.S. EPA’s enforceable MCLs for PFOA and PFOS are 4 ppt each, with non-enforceable health advisories of 0.004 ppt for PFOA and 0.02 ppt for PFOS, reflecting conservative estimates of safe exposure. The WHO’s draft provisional guidance values (pGVs) are higher, at 100 ppt for individual PFOA or PFOS and 500 ppt for total PFAS, based largely on treatment feasibility rather than strict health-based thresholds. In Australia, the ADWG recommends 200 ng/L (~200 ppt) for PFOA and 8 ng/L (~8 ppt) for PFOS, integrating updated toxicological evidence and chronic exposure considerations. The fact that organoid systems display functional and transcriptional effects at concentrations near or above EPA and ADWG thresholds, but well below WHO pGVs, highlights the sensitivity of these models.

10.3. Microplastics and Nanoplastics

Organoid studies show that MNPs are capable of eliciting toxicity at concentrations overlapping with human exposure scenarios, and their effects are amplified in the presence of co-contaminants or under chronic, developmental, or cell-type-specific contexts. For example, cardiac and intestinal organoids showed disruption at 5–50 µg/mL, while liver models revealed ferroptosis at nanogram-per-milliliter levels, especially with aged particles (

Table 3). Despite these findings, no enforceable drinking water standards currently exist for MNPs in the United States (EPA), though the EPA is considering monitoring under the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 6) for 2027–2031 following a 2024 petition [

124] from 175 environmental groups. Both the European Commission’s Science Advice for Policy organ, SAPEA [

125], and the WHO published reports [

126] stating that very little published data is available regarding either exposure to, or the toxicity of MNPs in humans, and acknowledging the challenges facing scientists attempting to gather robust information. In Australia, the National Plastics Plan 2021 acknowledges the growing concern around plastic pollution, including microplastics, and outlines actions such as phasing out problematic plastics and investing in research. However, Australia has not yet established specific drinking water guideline values for MNPs.

10.4. Pesticides and Pharmaceuticals

Organoid-based studies consistently show that many pesticides and pharmaceuticals exert toxicity at low-to-moderate micromolar concentrations. For example, triclosan, triclocarban, vinclozolin, and chlordecone typically disrupt cellular processes at 1–10 µM, while neurotoxic pesticides act within the 3–10 µM range. Pharmaceuticals such as doxorubicin and digoxin demonstrate toxicity at nanomolar to micromolar levels, overlapping with clinical exposure ranges. Glyphosate-based herbicides (GBHs) have shown developmental toxicity in cardiac organoids at concentrations as low as 0.1–10 µg/mL (

Table 4). Regulatory benchmarks often exceed these toxicologically active concentrations. The U.S. EPA sets the MCL for glyphosate in drinking water at 700 µg/L (≈4.1 µM), while the WHO has opted not to establish a formal guideline value, citing low risk under typical exposure conditions. In Australia, the freshwater ecosystem trigger value for glyphosate is 0.37 µg/L, which is well below the EPA’s drinking water limit and within the range of organoid-detected toxicity. Notably, chlorpyrifos, chlordecone, and vinclozolin are not currently regulated under EPA drinking water standards, despite being classified as hazardous pesticides. The WHO also does not include triclosan, vinclozolin, or most pharmaceuticals in its drinking water guidelines. Organoid models also reveal that short-term exposures can cause acute cytotoxicity or signaling disruption, while chronic exposures, such as to chlordecone or glyphosate with co-formulants like POEA, can lead to fibrosis and developmental mis-specification. Mixture studies (e.g., glyphosate + POEA, imidacloprid + lambda-cyhalothrin, or chlorpyrifos combined with CHD8 mutation) consistently show additive or synergistic effects that exceed single-agent toxicity (

Table 4), emphasizing the need for mixture testing in regulatory frameworks.

10.5. Nanoparticles

Nanoparticle toxicity is highly variable, depending on particle type, size, mor-phology, and biological context. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are among the most potent, with toxic effects observed at concentrations as low as 0.1–0.5 µg/mL in human cerebral organoids (

Table 5). The EPA’s secondary drinking water standard for silver is 0.1 mg/L (100 µg/L), which is 200–1000 times higher than the concentrations causing neurodevelopmental toxicity in organoids. The WHO has also reviewed silver in drinking water but does not currently recommend a health-based guideline value, citing limited data on chronic exposure, however suggesting that chronic exposure to up to 0.1 mg/L should be tolerated without health consequences [

127], contrasting the outcomes of the organoid studies. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) showed cytotoxicity in brain organoids at 64 µg/mL, with au-tophagy disruption and micronuclei formation (

Table 5). While zinc has a secondary EPA guideline of 5 mg/L (5000 µg/L), this is significantly above organoid-detected toxicity thresholds. The Australian Guidelines provide aquatic eco-system protection values for zinc but do not specify drinking water limits for ZnO na-noparticles. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO₂ NPs) impaired intestinal stem cell re-newal and hormone secretion at 20 µg/mL in mouse organoids (

Table 5). Despite widespread use in food and consumer products, TiO₂ is not currently regulated under EPA or WHO drinking water standards, and Australia does not list a drinking water guideline for TiO₂ NPs. Gold nanoparticles displayed shape-dependent toxicity: dendrimers induced ne-phrotoxicity at ≥0.675 mg/mL, while nanobranches caused hepatotoxicity at ≤200 µg/mL (

Table 5). These thresholds are well below any existing regulatory benchmarks, which are currently absent for gold-based nanomaterials.

10.6. Other Emerging Contaminants

Bisphenols and flame retardants consistently emerge as low-dose, high-risk disruptors, especially in brain, cardiac, thyroid, and placental organoids. Chronic exposure typically reveals more toxicity than acute exposure, even at lower concentrations. More specifically, studies reveal that bisphenols (e.g., BPA, BPS) and flame retardants exert toxicity at nanomolar concentrations, with effects on neural, cardiac, and endocrine organoids observed at levels as low as 1–100 nM (

Table 6). These thresholds are significantly lower than most regulatory benchmarks. The EPA has not established enforceable drinking water standards for BPA or its analogues, though it has listed BPA as a chemical of concern due to its reproductive and developmental toxicity and potential environmental risks. The WHO has not set formal guideline values for BPA, BPS, phthalates, or flame retardants in drinking water, citing insufficient toxicological data, though BPA has been flagged for endocrine-disrupting potential in recent EU directives. In Australia, none of these substances currently have specific drinking water guideline values under the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines (ADWG). By contrast, AFB1, which caused necrosis in mammary organoids at high experimental doses, has clearer regulatory attention due to its carcinogenicity (

Table 6). However, drinking water standards for AFB1 are rare, as it is more commonly regulated in food. The absence of enforceable limits for bisphenols and flame retardants is partic-ularly concerning given their potency at environmentally realistic concentrations, and their ability to disrupt organoid function over chronic low-dose exposures. Moreover, co-exposure scenarios, such as BPA with microplastics, have shown synergistic hepatotoxicity, reinforcing the need for mixture-based risk assessments.

Across contaminant classes, organoids reveal tissue-specific and developmental vulnerabilities, functional effects at sub-cytotoxic doses, and frequent mixture interactions; features that are incompletely captured by current guideline frameworks based mainly on chronic systemic endpoints. Integrating organoid-derived dose–response and mechanism-of-action data alongside epidemiology and animal studies would sharpen uncertainty factors, better represent sensitive life stages, and prioritize mixtures, thereby enabling more health-protective and evidence-aligned water quality standards.

11. Implications for Drinking Water Guidelines

The comparison between organoid-derived toxicity thresholds and existing inter-national drinking water guidelines reveals several important trends and discrepancies.

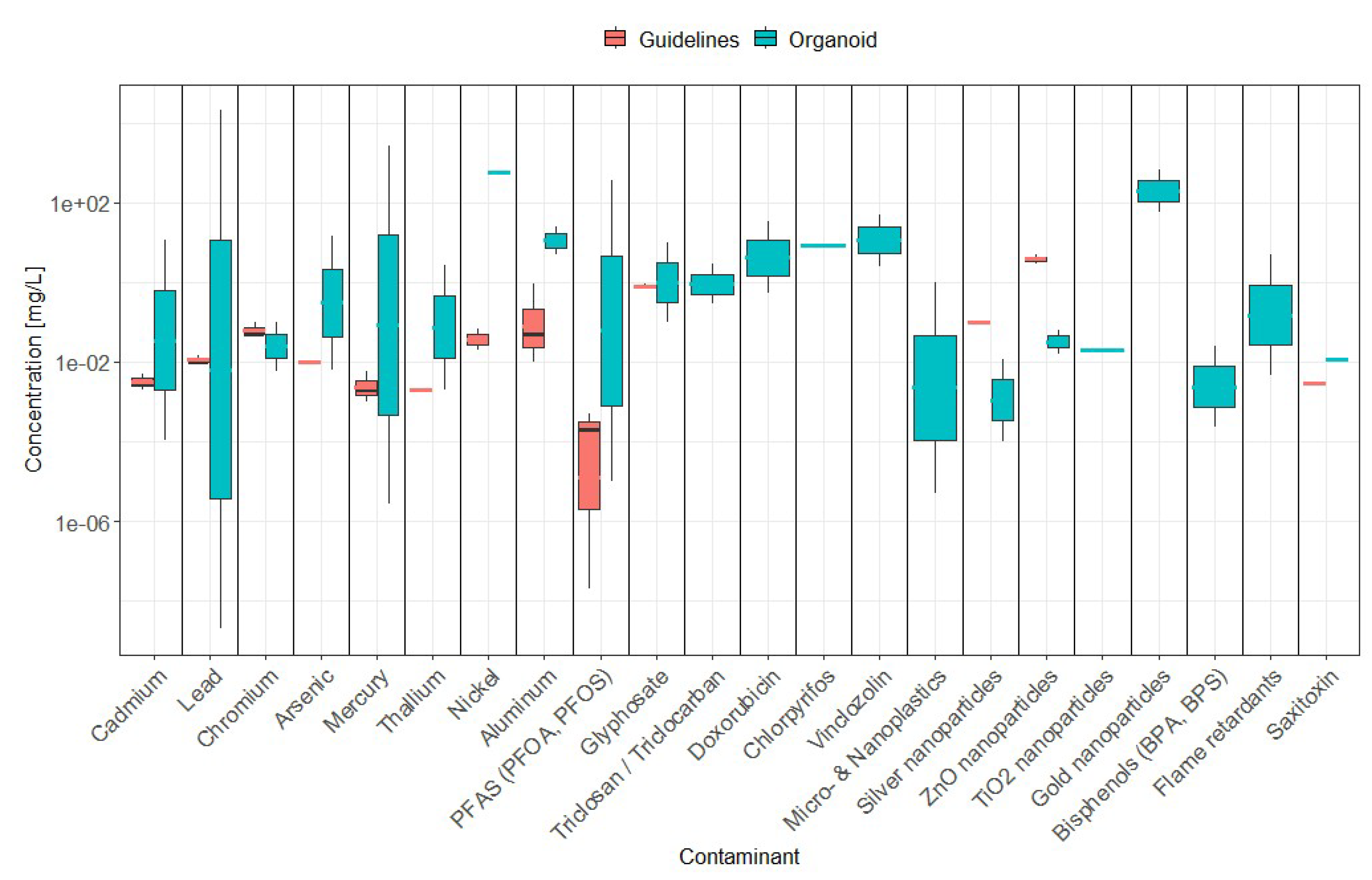

Figure 3 synthesizes these contrasts by juxtaposing guideline concentration ranges (ADWG, WHO, EPA) with organoid-derived toxic ranges across contaminant classes. As a result, organoid models often suggest adverse effects at concentrations that differ from current regulatory thresholds.

For heavy metals and metalloids, organoid studies frequently identified toxicity at concentrations close to, or in some cases below, drinking water guidelines. While cadmium, lead, and mercury caused toxicity within or near regulatory thresholds (as indicated in 10.1), these findings largely derive from short-term exposures, highlighting the need for time-resolved evaluations before any adjustment of guideline levels is considered. For thallium and nickel, organoid toxicity typically occurred above regulatory limits (e.g., Tl 0.002–2.76 mg/L versus an EPA limit of 0.002 mg/L), suggesting that current standards may already account for chronic, systemic effects not captured by acute in vitro assays. In contrast, aluminium caused organoid toxicity only at 5–25 mg/L, well above drinking-water limits (0.01–0.9 mg/L), consistent with the notion that current standards are protective.

Figure 3.

Contaminant-specific concentration ranges set by guidelines (ADWG, WHO, EPA – Red box plots) and toxic concentration ranges identified by the reviewed studies (Blue box plots). Specific chemical forms used in compiled studies are listed in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 and relevant sections.

Figure 3.

Contaminant-specific concentration ranges set by guidelines (ADWG, WHO, EPA – Red box plots) and toxic concentration ranges identified by the reviewed studies (Blue box plots). Specific chemical forms used in compiled studies are listed in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 and relevant sections.

For emerging organic contaminants, significant misalignments appear. PFAS (PFOA and PFOS) induced toxicity in organoids between 0.00001–371 mg/L, which is orders of magnitude higher than the increasingly stringent guideline values (down to 2 × 10⁻⁸ mg/L in the US EPA). This gap likely reflects precautionary risk assessments driven by epidemiological and bioaccumulation data, whereas organoid studies may underestimate low-dose chronic effects due to their experimental timeframes. Glyphosate (GLY) induced cytotoxicity in cardiac organoids at 0.1–10 mg/L, generally overlapping but occasionally exceeding drinking-water guideline values (0.7–0.9 mg/L), suggesting partial agreement but also highlighting potential for cardiac impairment after short-term exposure to doses below guidelines values. Triclosan (TCS), triclocarban (TCC), vinclozolin (VIN), and chlordecone (CHL) all exhibited cellular toxicity in the low mg/L range, however no regulatory thresholds exist, leaving a critical gap for risk assessment.For microplastics and nanoplastics (MNPs), organoid studies provide some of the first experimental evidence of toxicity, with effects observed at 0.000005–1 mg/L. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs, 0.0001–0.012 mg/L) and zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs, 0.016–0.064 mg/L) elicited toxicity below existing thresholds (EPA: 0.1 mg/L and 5 mg/L, respectively), suggesting regulatory concern is warranted and should be expanded to all regulatory bodies (e.g. ADWG). No international guidelines exist for titanium dioxide (TiO₂ NPs), gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), or MNPs, despite demonstrated cellular effects, reflecting in turn an urgent need to integrate these contaminants into regulatory frameworks. Similarly, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) such as bisphenols and flame retardants showed organoid toxicity at very low concentrations (e.g., bisphenol at 2.28 × 10⁻⁴ mg/L), suggesting potential risks at levels below those currently regulated. The absence of formal guideline values for these contaminants reflects regulatory lag relative to emerging toxicological evidence.

Additionally, for algal toxins, the limited research evidence from organoid studies points at saxitoxin toxicity at concentrations (12 ug/L) near most drinking water guidelines, but well below recreational water guidelines (30 ug/L, both ADWG and WHO) where toxic algal blooms may be more common and problematic; however, only a particular scenario was tested, i.e. increased vulnerability to zika virus, thus more research is warranted. Similarly, while excluded from this review due to the use of cell lines, other studies point at toxic concentrations of other toxins such as Microcystin-LR [

128] and Cylindrospermopsin [

129] below recreational water guidelines and in some instances also drinking water guidelines; due to the very limited number studies, more research on algal toxins with organoids is required to validate the appropriateness of current regulatory thresholds, when existing.

Overall, these findings highlight three critical themes. First, for established contaminants such as Cd and Hg, organoid-derived thresholds are broadly consistent with existing guidelines, but further research should continue investigating the short-term toxic effects at concentrations below current guidelines to inform potential regulatory changes. Second, for chemicals like Pb and PFAS, regulatory limits are orders of magnitude stricter than organoid toxicity concentrations, likely reflecting precautionary principles and long-term epidemiological data. Third, for emerging pollutants such as nanoparticles, microplastics, and EDCs, organoid studies provide essential early warning signals in the absence of formal guidelines. This suggests a dual role for organoid models: validating existing thresholds for known contaminants, while identifying potential risks for novel compounds.

Existing regulatory databases such as EPA’s IRIS [

130] and ECOTOX [

131] and the EU REACH [

132] framework provide a foundation for chemical risk assessment and guideline derivation. However, these systems remain incomplete for many cyanotoxins, emerging DBPs, and novel pollutants such as nanoparticles and microplastics. Their omission points, potentially, to regulatory data gaps and the limited applicability of traditional toxicity end-points to dynamic exposure scenarios. EU REACH regulation, in particular, increasingly advocates the use of human-relevant, non-animal models, which is an approach consistent with organoid-based toxicological assessments.

In this context, a critical gap emerges: to the best of our knowledge, organoid studies meeting our criteria that assess toxicity of DBPs are lacking. These studies would be important both for assessing toxicity of well-known DBPs, especially in scenarios not easily assessable by epidemiological studies such as short-term exposures or com-pounding effects from DBP mixtures, and for assessing toxicity risks of emerging DBPs of concern. Similarly, organoid studies on algal/cyanobacteria toxins are also very limited in numbers. Moving forward, integrating organoid toxicology with epidemiological and in vivo data will be crucial for refining water quality guidelines and addressing regulatory gaps for emerging contaminants.

A final important consideration involves not only the stringency of regulatory thresholds but also the practicalities of enforcement and monitoring. While for several compounds, current drinking water guidelines around the world seem to be sufficiently conservative to account for potential toxicity, compliance in real-world systems relies heavily on the frequency and resolution of monitoring. In many jurisdictions, water testing is conducted intermittently, often on monthly or even quarterly schedules. Such approaches may miss short-lived but biologically relevant spikes in contaminant concentrations, particularly in dynamic systems affected by rainfall, stormwater inflows, or industrial discharges. Evidence from organoid studies suggests that acute, transient exposures can be enough to trigger developmental or cellular toxicity, even if long-term averages remain below guideline values. For example, organoid models have demonstrated adverse outcomes after exposures of only 24–72 hours to contaminants such as Hg, bisphenols, or certain pesticides, raising concerns that episodic peaks in con-centration could pose risks that standard monitoring frameworks fail to capture. This issue becomes even more critical for emerging contaminants such as PFAS, nanoparticles, and microplastics, where bioaccumulation and interactions with other stressors may amplify effects that are not adequately reflected in snapshot monitoring data.

These insights point to the need for more adaptive, high-frequency monitor-ing/modelling strategies that can better capture fluctuations and short-term exceedances, rather than relying solely on compliance with static threshold values. Advances in real-time sensing technologies, combined with predictive modelling, could play an important role in bridging this gap. At the same time, policy frameworks may need to consider not just average concentrations, but also the frequency, duration, and intensity of exceedances in order to align regulatory enforcement with the biological reality of contaminant exposure.

11. Conclusions

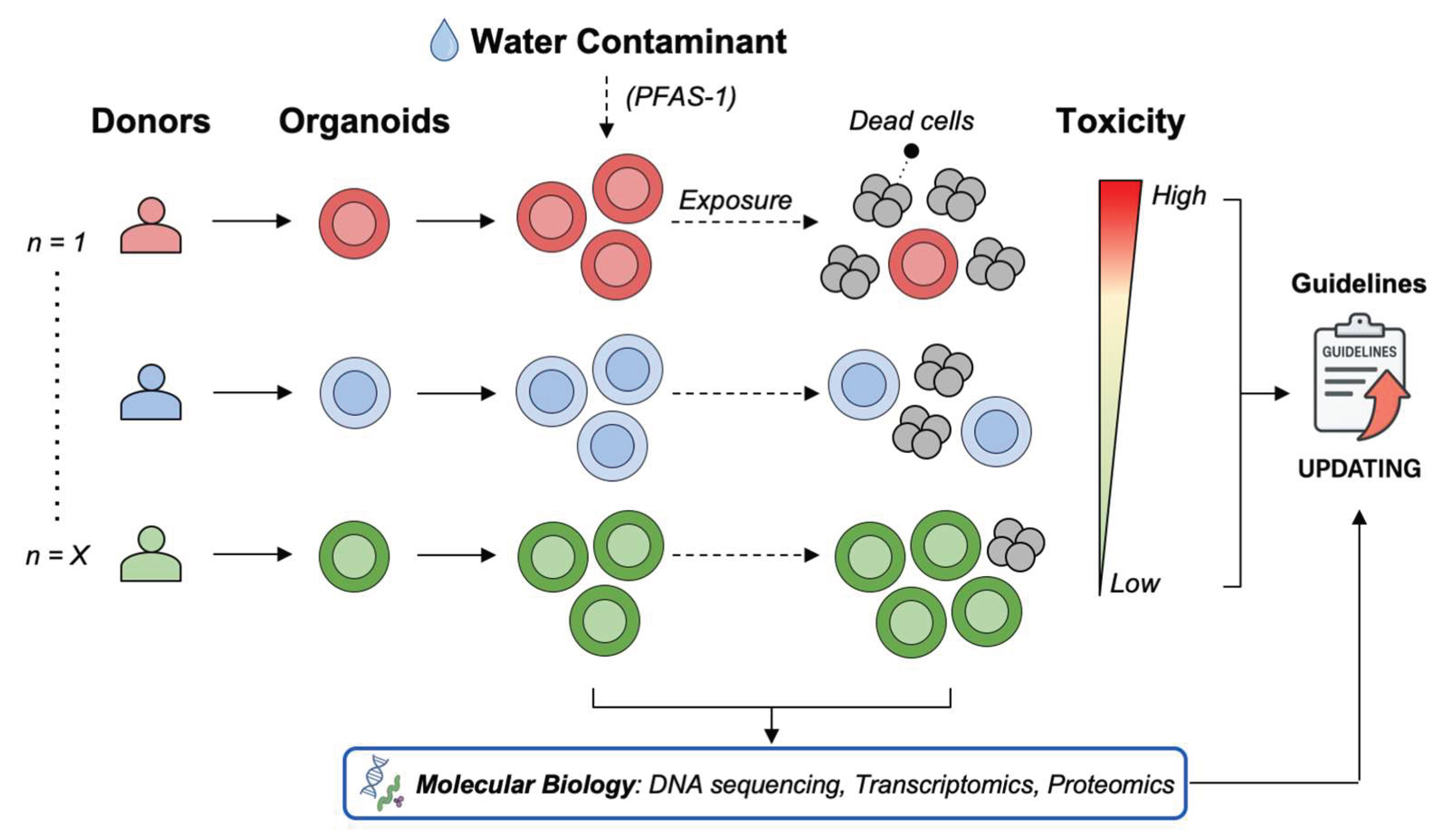

This review shows that organoids provide a physiologically relevant platform for assessing the toxicological impacts of environmental contaminants, offering a closer approximation of human tissue responses than conventional models. Organoid-based studies on water contaminants have demonstrated that organoids can reveal dose-dependent toxicity patterns, identify previously unrecognized cellular stress responses, and capture differential susceptibility across tissue types. Consequently, organoids offer a more accurate platform to investigate toxic effects and mechanisms, with significant potential for environmental toxicology. However, many toxicological assessments still rely on conventional 2D cell line cultures, which remain cheaper and easier to manipulate and form the basis for current water quality guidelines. One of the most important yet underexplored strengths of patient-derived organoids is their capacity to capture inter-donor variability in responses to environmental contaminants. To date, most organoid-based toxicology studies have not systematically addressed this concept, even though it represents a critical advantage over conventional models. When organoids from multiple donors are exposed to pollutants such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), heavy metals, or microplastics, the toxic effects are unlikely to be uniform. In some donors, contaminants may cause complete organoid death; in others, partial toxicity allows subpopulations to persist; while in a minority of donors, minimal or no effects are observed. This heterogeneity reflects intrinsic biological diversity that cannot be reproduced with 2D cell lines or animal surrogates. For instance, if organoids derived from 30 colorectal tissue donors were tested, one could imagine that 80% might exhibit marked toxicity to one PFAS (PFAS-1) while only 20% respond to another (PFAS-2). Such a hypothetical scenario illustrates how inter-donor variability could provide critical insight into population-level susceptibility (

Figure 4).

Such donor-specific differences can be viewed as a toxicity gradient, from high to low sensitivity. Recognizing this spectrum highlights the need for population-scale organoid testing to identify both vulnerable and resilient subgroups. Integrating inter-donor heterogeneity into toxicology studies would directly connect in vitro findings with real-world variability, refine regulatory frameworks, and enable more personalized environmental risk assessments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and E.B; methodology, R.C. and E.B; software, R.C. and E.B; validation, R.C. and E.B; formal analysis, R.C. and E.B; investigation, R.C. and E.B; resources, R.C. and E.B; data curation, R.C. and E.B; writing—original draft preparation, R.C. and E.B; writing—review and editing, R.C. and E.B; visualization, R.C. and E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Microsoft 365 Copilot (Standard Access) and OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-5) to assist with systematic data extraction from reviewed literature. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited all generated content and take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. R.C. belongs to the Department of Clinical Bio-resource Research and Development at Kyoto University, which is sponsored by KBBM.

References

- Vasseghian, Y.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Khataee, A.; Dragoi, E.-N. The Concentration of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Water Resources: A Global Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Probabilistic Risk Assessment. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 796, 149000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Malule, H.; Quiñones-Murillo, D.H.; Manotas-Duque, D. Emerging Contaminants as Global Environmental Hazards. A Bibliometric Analysis. Emerging Contaminants 2020, 6, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Arjunan, A.; Baroutaji, A.; Zakharova, J. A Review of Physicochemical and Biological Contaminants in Drinking Water and Their Impacts on Human Health. Water Science and Engineering 2023, 16, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Qureshi, M.; Vishwakarma, D.K.; Al-Ansari, N.; Kuriqi, A.; Elbeltagi, A.; Saraswat, A. A Review on Emerging Water Contaminants and the Application of Sustainable Removal Technologies. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2022, 6, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Huo, X.; Cheng, Z.; Faas, M.M.; Xu, X. Early-Life Exposure to Widespread Environmental Toxicants and Maternal-Fetal Health Risk: A Focus on Metabolomic Biomarkers. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 739, 139626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.S.; D, D.; S, H.; Sonkusare, S.; Naik, P.B.; Kumari N, S.; Madhyastha, H. Environmental Pollutants and Their Effects on Human Health. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, L.; Sun, J.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Yuan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Larsson, S.; Tsilidis, K.; et al. Global Trends in Incidence, Death, Burden and Risk Factors of Early-Onset Cancer from 1990 to BMJ Oncology. 2023, 2, e000049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, K.; Grover, H.; Han, L.-H.; Mou, Y.; Pegoraro, A.F.; Fredberg, J.; Chen, Z. Modeling Physiological Events in 2D vs. 3D Cell Culture. Physiology 2017, 32, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, P.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, D.; Nandi, S.K. Role of Animal Models in Biomedical Research: A Review. Laboratory Animal Research 2022, 38, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, J.; Thew, M.; Balls, M. An Analysis of the Use of Animal Models in Predicting Human Toxicology and Drug Safety. Altern Lab Anim 2014, 42, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.-P.; Merlino, G.; Van Dyke, T. Preclinical Mouse Cancer Models: A Maze of Opportunities and Challenges. Cell 2015, 163, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvani, S.; Figliuzzi, M.; Remuzzi, A. Toxicological Evaluation of Airborne Particulate Matter. Are Cell Culture Technologies Ready to Replace Animal Testing? Journal of Applied Toxicology 2019, 39, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, U.; Siranosian, B.; Ha, G.; Tang, H.; Oren, Y.; Hinohara, K.; Strathdee, C.A.; Dempster, J.; Lyons, N.J.; Burns, R.; et al. Genetic and Transcriptional Evolution Alters Cancer Cell Line Drug Response. Nature 2018, 560, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Knoblich, J.A. Organogenesis in a Dish: Modeling Development and Disease Using Organoid Technologies. Science 2014, 345, 1247125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, L.; Pamies, D.; Frangiamone, M. Human Organoids to Assess Environmental Contaminants Toxicity and Mode of Action: Towards New Approach Methodologies. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H. Modeling Development and Disease with Organoids. Cell 2016, 165, 1586–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.H.N.; Chan, A.S.; Lai, F.P.-L.; Leung, S.Y. Organoid Cultures for Cancer Modeling. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 917–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppo, R.; Inoue, M. Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids to Model Cancer Cell Plasticity and Overcome Therapeutic Resistance. Cells 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roerink, S.F.; Sasaki, N.; Lee-Six, H.; Young, M.D.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Behjati, S.; Mitchell, T.J.; Grossmann, S.; Lightfoot, H.; Egan, D.A.; et al. Intra-Tumour Diversification in Colorectal Cancer at the Single-Cell Level. Nature 2018, 556, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppo, R.; Kondo, J.; Iida, K.; Okada, M.; Onuma, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Kamada, M.; Ohue, M.; Kawada, K.; Obama, K.; et al. Distinct but Interchangeable Subpopulations of Colorectal Cancer Cells with Different Growth Fates and Drug Sensitivity. iScience 2023, 26, 105962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, K.K.; Vendramin, R.; Karagianni, D.; Witsen, M.; Gálvez-Cancino, F.; Hill, M.S.; Foster, K.A.; Barbè, V.; Angelova, M.; Hynds, R.E.; et al. Subclonal Immune Evasion in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.E.; Georgescu, A.; Huh, D. Organoids-on-a-Chip.

- Nikolaev, M.; Mitrofanova, O.; Broguiere, N.; Geraldo, S.; Dutta, D.; Tabata, Y.; Elci, B.; Brandenberg, N.; Kolotuev, I.; Gjorevski, N.; et al. Homeostatic Mini-Intestines through Scaffold-Guided Organoid Morphogenesis. Nature 2020, 585, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magré, L.; Verstegen, M.M.A.; Buschow, S.; Van Der Laan, L.J.W.; Peppelenbosch, M.; Desai, J. Emerging Organoid-Immune Co-Culture Models for Cancer Research: From Oncoimmunology to Personalized Immunotherapies. J Immunother Cancer 2023, 11, e006290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwokoye, P.N.; Abilez, O.J. Bioengineering Methods for Vascularizing Organoids. Cell Reports Methods 2024, 4, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilca, A.F.; Teodosiu, C.; Fiore, S.; Musteret, C.P. Emerging Disinfection Byproducts: A Review on Their Occurrence and Control in Drinking Water Treatment Processes. Chemosphere 2020, 259, 127476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Chu, W.; Krasner, S.W.; Yu, Y.; Fang, C.; Xu, B.; Gao, N. The Stability of Chlorinated, Brominated, and Iodinated Haloacetamides in Drinking Water. Water Research 2018, 142, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R.; Villanueva, C.M.; Beene, D.; Cradock, A.L.; Donat-Vargas, C.; Lewis, J.; Martinez-Morata, I.; Minovi, D.; Nigra, A.E.; Olson, E.D.; et al. US Drinking Water Quality: Exposure Risk Profiles for Seven Legacy and Emerging Contaminants. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 2024, 34, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, Michael, C. Ingrid Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-1-003-08144-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa, C. da S.G.; Souza, L.R.Q.; Gomes, T.A.; de Lima, C.V.F.; Ledur, P.F.; Karmirian, K.; Barbeito-Andres, J.; Costa, M. do N.; Higa, L.M.; Rossi, Á.D.; et al. The Cyanobacterial Saxitoxin Exacerbates Neural Cell Death and Brain Malformations Induced by Zika Virus. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2020, 14, e0008060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Naseri, K.; Tahergorabi, Z.; Khazdair, M.R.; Sadeghi, M. Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, Volume 12-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shi, Q.; Liu, C.; Sun, Q.; Zeng, X. Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Heavy Metals on Human Health. Toxics 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasneem, S.; Farrell, K.; Lee, M.-Y.; Kothapalli, C.R. Sensitivity of Neural Stem Cell Survival, Differentiation and Neurite Outgrowth within 3D Hydrogels to Environmental Heavy Metals. Toxicology Letters 2016, 242, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, S.D.; Devarasetty, M.; Shupe, T.; Bishop, C.; Atala, A.; Soker, S.; Skardal, A. Environmental Toxin Screening Using Human-Derived 3D Bioengineered Liver and Cardiac Organoids. Frontiers in Public Health 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, J. Engineering Brain Organoids to Probe Impaired Neurogenesis Induced by Cadmium. ACS Biomaterials Science and Engineering 2018, 4, 1908–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, M.; Liu, Y.; Lu, R.; Feng, W. Lead Exposure Leads to Premature Neural Differentiation via Inhibiting Wnt Signaling. Environmental Pollution 2024, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Guo, X.; Lu, S.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Z.; Lai, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Luo, L.; Li, J. Long-Term Exposure to Cadmium Disrupts Neurodevelopment in Mature Cerebral Organoids. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]