Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

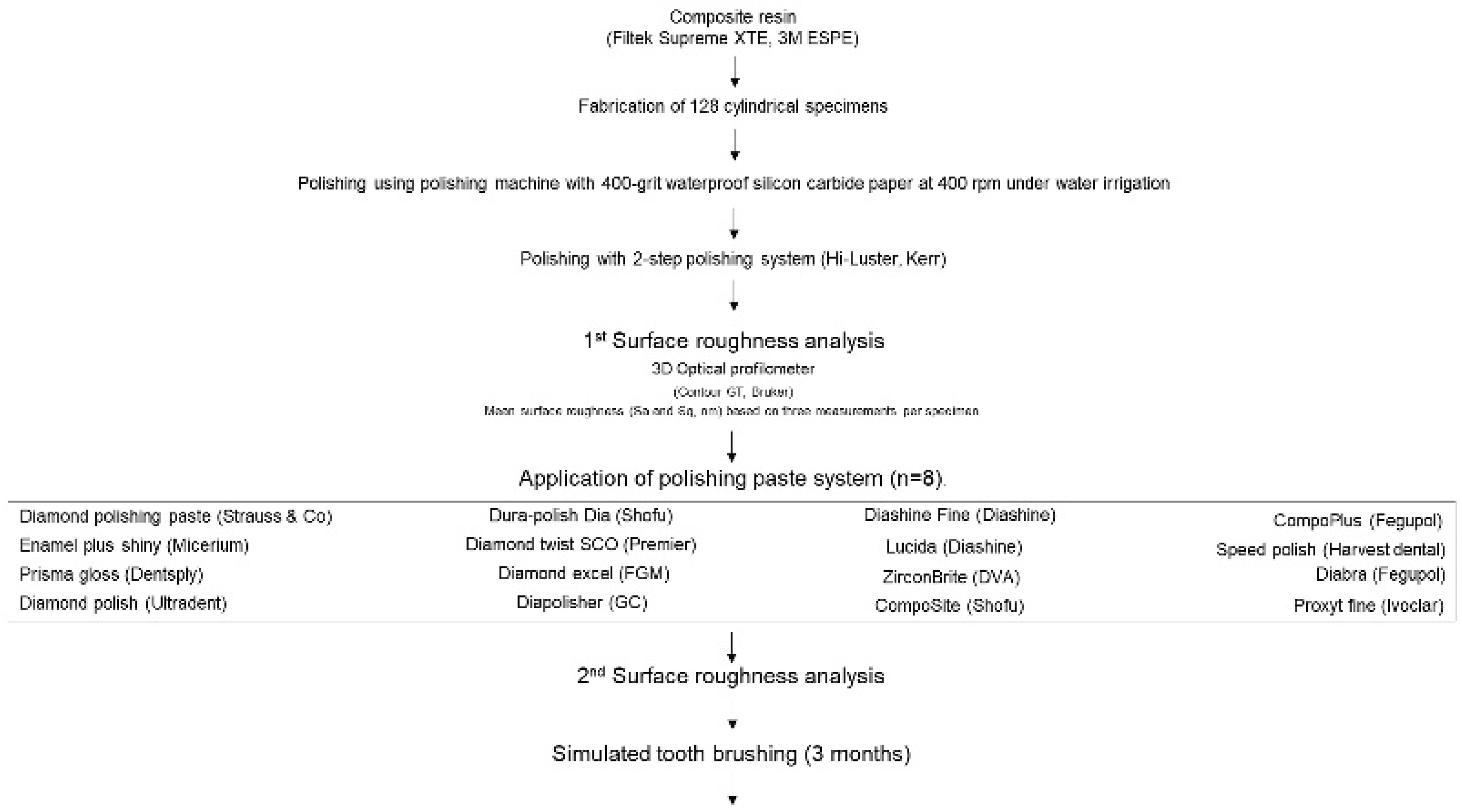

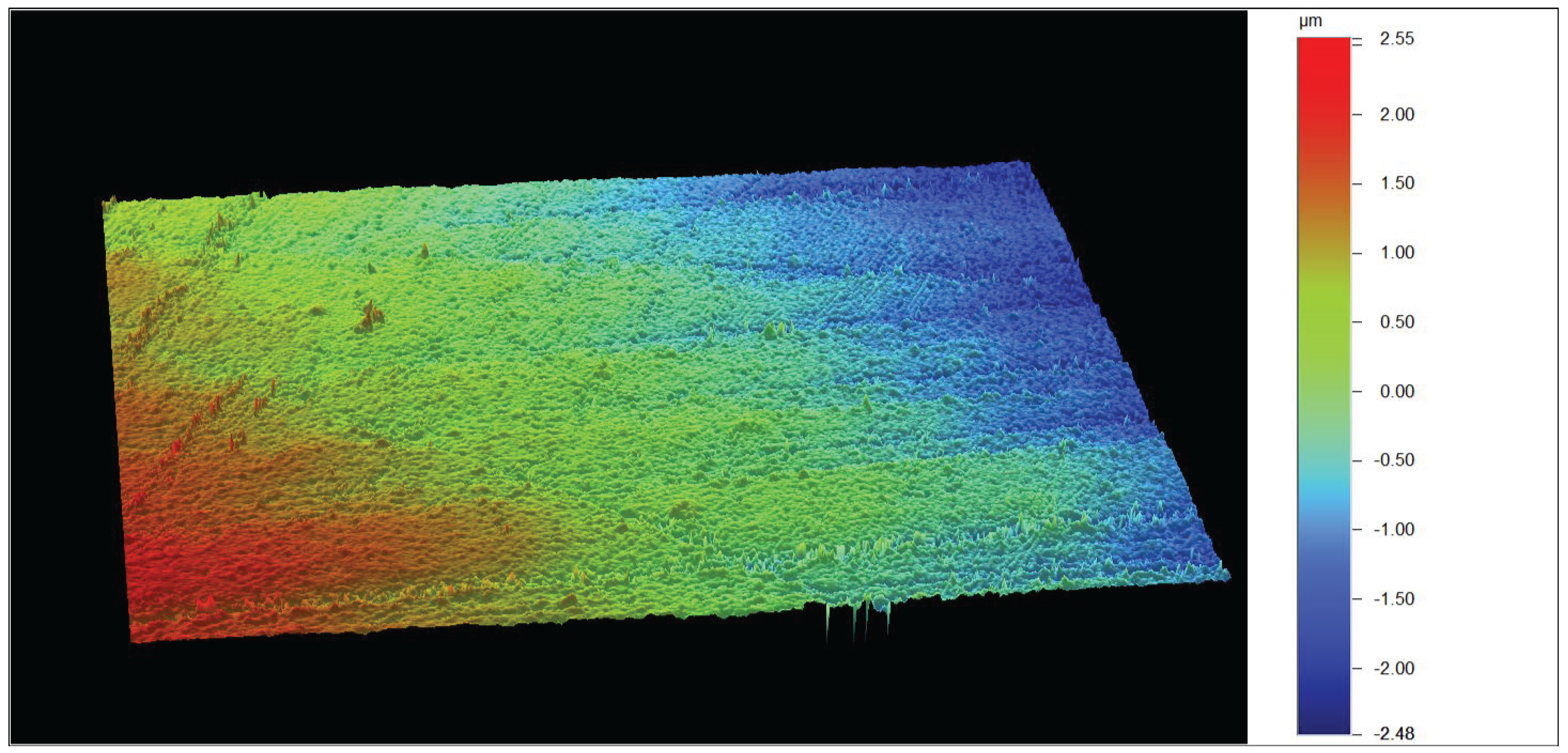

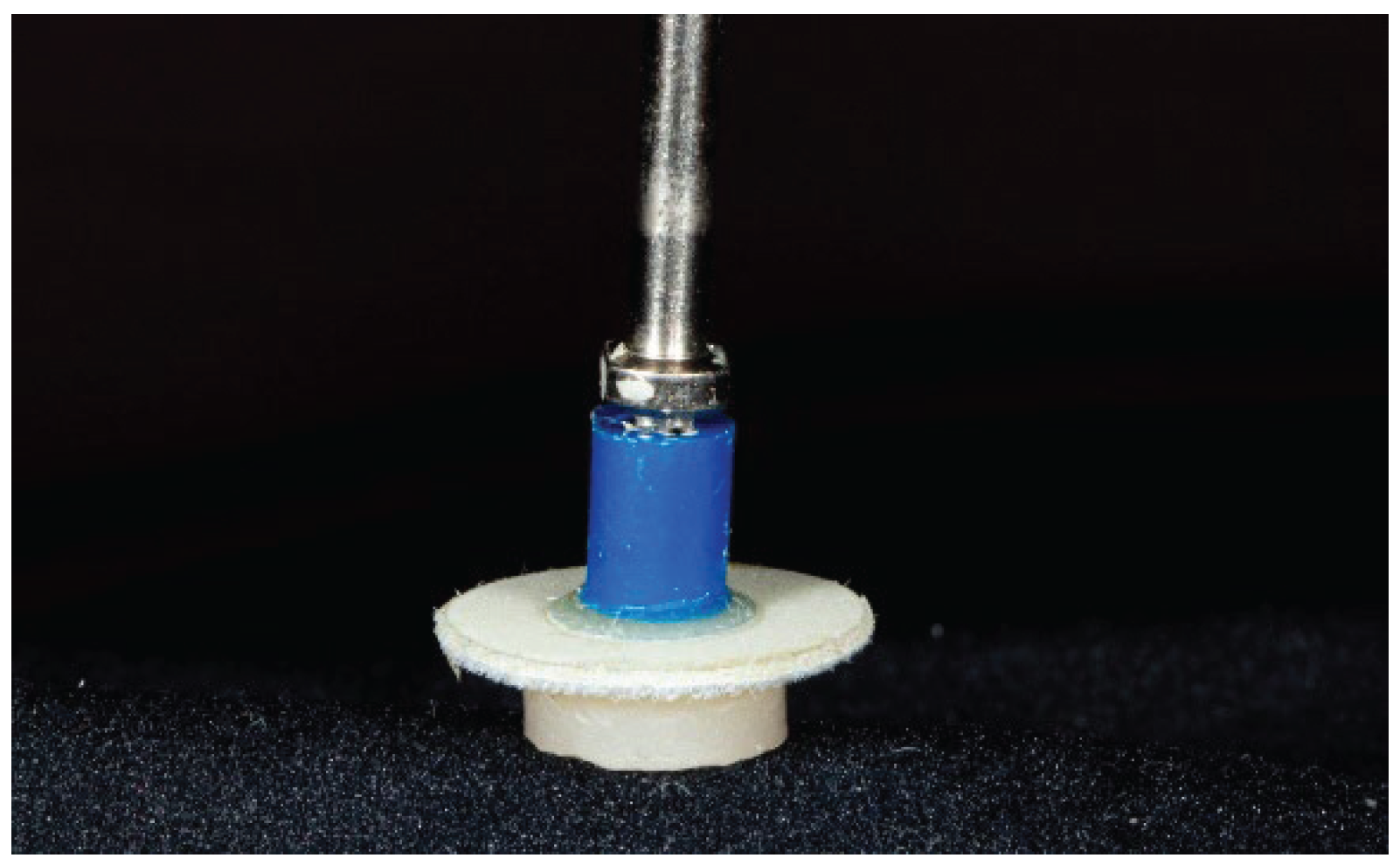

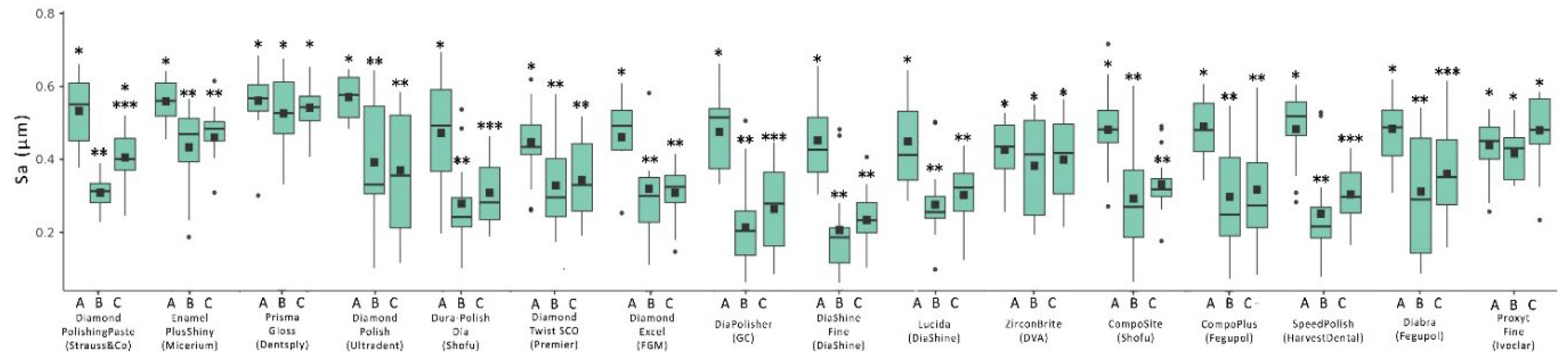

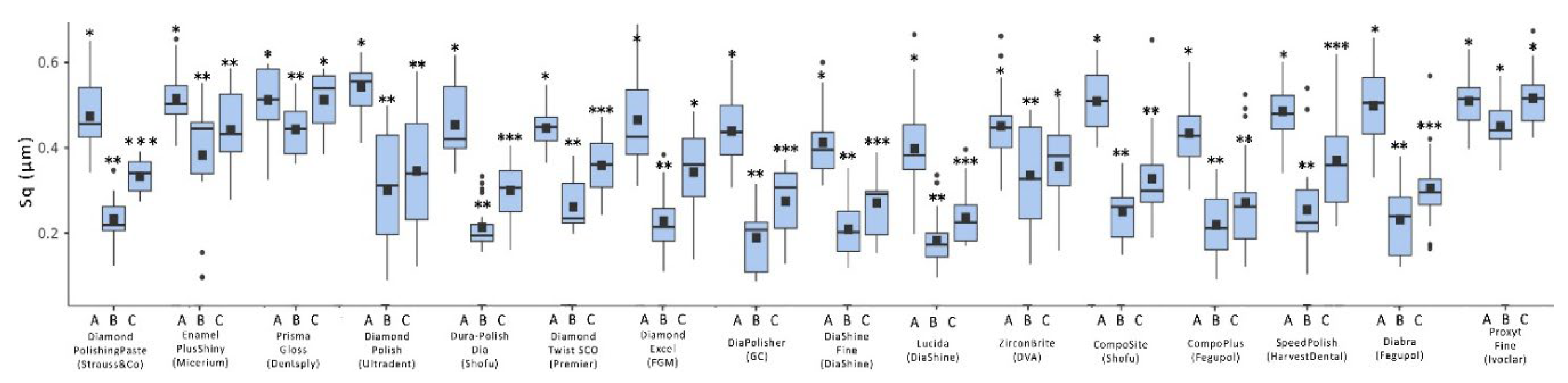

Background/Objectives: Achieving and maintaining a smooth restoration surface is clinically significant, as surface roughness is linked to plaque accumulation, staining, and wear. This study aimed to evaluate in vitro the effect of different polishing paste systems on reducing surface roughness and to assess their performance after simulated post-operative maintenance through toothbrushing. Methods: A total of 128 cylindrical, flat-surface specimens were fabricated from a nanohybrid composite (Filtek Supreme XTE, 3M, USA) using a standardized metal mold. All specimens were finished with silicon carbide paper and polished with a two-step rubber disc system (Hi-Luster, Kerr, USA). They were then randomly assigned to 16 groups (n = 8) according to the polishing protocol. One group was polished with a prophylaxis paste, while the other 15 groups were treated with pastes indicated for composite and/or ceramic materials. Polishing was performed with a flat buff wheel. To simulate clinical maintenance, specimens underwent a standardized toothbrushing cycle equivalent to three months of use. Surface roughness parameters (Sa and Sq) were measured at three stages with an optical profilometer: after initial polishing, after paste application, and after simulated toothbrushing. Results: Mean Sa values ranged from 0.065 to 0.560 and Sq values from 0.075 to 0.676. Significant differences were found among pastes for both parameters (P<0.05). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant differences after polishing paste application, both before and after toothbrushing (P < 0.05). Toothbrushing increased roughness in most groups (P<0.05), although no significant deterioration was observed for 9 pastes in Sa and 8 in Sq (P≥0.05). Conclusions: Polishing pastes vary in effectiveness, and not all produce measurable improvements in surface smoothness. Their efficiency appears to be unrelated to the abrasive or the number of steps. Simulated toothbrushing over a three-month period may reduce the initial benefits, emphasizing the importance of careful clinical selection.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

Sample

Sample Fabrication

Initial Polishing

Additional Polishing

Simulated Tooth Brushing

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Clinicians need to recognize that the effectiveness of polishing paste systems varies among composite resins, as some systems may not effectively enhance the surface smoothness of restorations.

- The efficiency of each paste does not appear to be related to the type of abrasive particles or the number of polishing steps.

- Simulated toothbrushing over 3 months diminishes the beneficial effects achieved by the additional application of some of the investigated polishing paste systems.

- Further research is needed to identify the optimal combination of polishing paste and composite resin.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gnusins, V.; Akhondi, S.; Zvirblis, T.; Pala, K.; Gallucci, G.O.; Puisys, A. Chairside vs Prefabricated Sealing Socket Abutments for Posterior Immediate Implants: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2025, 27, e70076. [CrossRef]

- Dutra, M.D.Z.; De Carli, J.P.; Dallepiane, F.G.; et al. Effectiveness of customized healing abutments in immediate implants: a randomized clinical trial. Braz Oral Res 2025, 39, e084.

- Wolff, D.; Frese, C.; Frankenberger, R.; et al. Direct Composite Restorations on Permanent Teeth in the Anterior and Posterior Region – An Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline – Part 1: Indications for Composite Restorations. J Adhes Dent 2024, 26, 185–200. [CrossRef]

- Dutra, D.; Pereira, G.; Kantorski, K.Z.; Valandro, L.F.; Zanatta, F.B. Does Finishing and Polishing of Restorative Materials Affect Bacterial Adhesion and Biofilm Formation? A Systematic Review. Oper Dent 2018, 43, E37–E52. [CrossRef]

- Cazzaniga, G.; Ottobelli, M.; Ionescu, A.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Brambilla, E. Surface properties of resin-based composite materials and biofilm formation: A review of the current literature. Am J Dent 2015, 28, 311–320.

- Jaramillo-Cartagena, R.; López-Galeano, E.J.; Latorre-Correa, F.; Agudelo-Suárez, A.A. Effect of Polishing Systems on the Surface Roughness of Nano-Hybrid and Nano-Filling Composite Resins: A Systematic Review. Dent J (Basel) 2021, 9, 95. [CrossRef]

- Bollen, C.M.; Papaioannou, W.; Van Eldere, J.; Schepers, E.; Quirynen, M.; Van Steenberghe, D. The influence of abutment surface roughness on plaque accumulation and peri-implant mucositis. Clin Oral Implants Res 1996, 7, 201–211.

- Daud, A.; Gray, G.; Lynch, C.D.; Wilson, N.H.F.; Blum, I.R. A randomized controlled study on the use of finishing and polishing systems on different resin composites using 3D contact optical profilometry and scanning electron microscopy. J Dent 2018, 71, 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Joniot, S.B.; Grégoire, G.L.; Auther, A.M.; Roques, Y.M. Three-dimensional optical profilometry analysis of surface states obtained after finishing sequences for three composite resins. Oper Dent 2000, 25, 311–315.

- St-Pierre, L.; Martel, C.; Crépeau, H.; Vargas, M.A. Influence of Polishing Systems on Surface Roughness of Composite Resins: Polishability of Composite Resins. Oper Dent 2019, 44, E122–E132. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.G.; Rocha, R.S.; Spinola, M.D.S.; Batista, G.R.; Bresciani, E.; Caneppele, T.M.F. Surface smoothness of resin composites after polishing – A systematic review and network meta-analysis of in vitro studies. Eur J Oral Sci 2023, 131, e12921. [CrossRef]

- Mangat, P.; Masarat, F.; Rathore, G.S. Quantitative and qualitative surface analysis of three resin composites after polishing – An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent 2022, 25, 448–451. [CrossRef]

- Kamonkhantikul, K.; Arksornnukit, M.; Takahashi, H.; Kanehira, M.; Finger, W.J. Polishing and toothbrushing alters the surface roughness and gloss of composite resins. Dent Mater J 2014, 33, 599–606. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Junior, S.A.; Chemin, P.; Piaia, P.P.; Ferracane, J.L. Surface Roughness and Gloss of Actual Composites as Polished With Different Polishing Systems. Oper Dent 2015, 40, 418–429. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.A.; Eskelson, E.; Cavalli, V.; Liporoni, P.C.; Jorge, A.O.; do Rego, M.A. Streptococcus mutans biofilm adhesion on composite resin surfaces after different finishing and polishing techniques. Oper Dent 2011, 36, 311–317. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, J.B.; Ferracane, J.L.; Amaya-Pajares, S.; Pfefferkorn, F. Visually acceptable gloss threshold for resin composite and polishing systems. J Am Dent Assoc 2021, 152, 385–392. [CrossRef]

- Saleh Ismail, H.; Ibrahim Ali, A. The Effect of Finishing and Polishing Systems on Surface Roughness and Microbial Adhesion of Bulk Fill Composites: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Dent 2023, 20, 26. [CrossRef]

- Bollen, C.M.; Lambrechts, P.; Quirynen, M. Comparison of surface roughness of oral hard materials to the threshold surface roughness for bacterial plaque retention: a review of the literature. Dent Mater 1997, 13, 258–269. [CrossRef]

- Kaizer, M.R.; de Oliveira-Ogliari, A.; Cenci, M.S.; Opdam, N.J.; Moraes, R.R. Do nanofill or submicron composites show improved smoothness and gloss? A systematic review of in vitro studies. Dent Mater 2014, 30, e41–78. [CrossRef]

- Devlukia, S.; Hammond, L.; Malik, K. Is surface roughness of direct resin composite restorations material and polisher-dependent? A systematic review. J Esthet Restor Dent 2023, 35, 947–967. [CrossRef]

- Amaya-Pajares, S.P.; Koi, K.; Watanabe, H.; da Costa, J.B.; Ferracane, J.L. Development and maintenance of surface gloss of dental composites after polishing and brushing: Review of the literature. J Esthet Restor Dent 2022, 34, 15–41. [CrossRef]

- Heintze, S.D.; Forjanic, M.; Rousson, V. Surface roughness and gloss of dental materials as a function of force and polishing time in vitro. Dent Mater 2006, 22, 146–165. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.D.; Raisingani, D.; Jindal, D.; Mathur, R. A Comparative Analysis of Different Finishing and Polishing Devices on Nanofilled, Microfilled, and Hybrid Composite: A Scanning Electron Microscopy and Profilometric Study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2016, 9, 201–208. [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.B.; Marsilio, A.L.; Pagani, C.; Rodrigues, J.R. Surface roughness of packable composite resins polished with various systems. J Esthet Restor Dent 2004, 16, 42–47. [CrossRef]

- Joniot, S.; Salomon, J.P.; Dejou, J.; Grégoire, G. Use of two surface analyzers to evaluate the surface roughness of four esthetic restorative materials after polishing. Oper Dent 2006, 31, 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Krithikadatta, J.; Gopikrishna, V.; Datta, M. CRIS Guidelines (Checklist for Reporting In-vitro Studies): A concept note on the need for standardized guidelines for improving quality and transparency in reporting in-vitro studies in experimental dental research. J Conserv Dent 2014, 17, 301–304. [CrossRef]

- Neme, A.M.; Wagner, W.C.; Pink, F.E.; Frazier, K.B. The effect of prophylactic polishing pastes and toothbrushing on the surface roughness of resin composite materials in vitro. Oper Dent 2003, 28, 808–815.

- Adam, R. Introducing the Oral-B iO electric toothbrush: next generation oscillating-rotating technology. Int Dent J 2020, 70 (Suppl 1), S1–S6. [CrossRef]

- Bizhang, M.; Schmidt, I.; Chun, Y.P.; Arnold, W.H.; Zimmer, S. Toothbrush abrasivity in a long-term simulation on human dentin depends on brushing mode and bristle arrangement. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0172060. [CrossRef]

- Pietrokovski, Y.; Zeituni, D.; Schwartz, A.; Beyth, N. Comparison of Different Finishing and Polishing Systems on Surface Roughness and Bacterial Adhesion of Resin Composite. Materials (Basel) 2022, 15, 7415. [CrossRef]

- Yap, A.U.; Yap, S.H.; Teo, C.K.; Ng, J.J. Comparison of surface finish of new aesthetic restorative materials. Oper Dent 2004, 29, 100–104.

- Tosco, V.; Monterubbianesi, R.; Orilisi, G.; Procaccini, M.; Grandini, S.; Putignano, A.; Orsini, G. Effect of four different finishing and polishing systems on resin composites: roughness surface and gloss retention evaluations. Minerva Stomatol 2020, 69, 207–214. [CrossRef]

- Atash, R.; et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of four composite polishing systems: an in vitro study. Int J Prosthod Restor Dent 2024, 14, 16–22. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, C.M.; Bhat, K.M.; Bansal, R. Evaluation of surface roughness of different restorative composites after polishing using atomic force microscopy. J Conserv Dent 2016, 19, 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Güler, A.U.; Güler, E.; Yücel, A.C.; Ertaş, E. Effects of polishing procedures on color stability of composite resins. J Appl Oral Sci 2009, 17, 108–112. [CrossRef]

- Korkut, B.; Alkan, E.; Öztürk, E.K.; Türkmen, C.; Tağtekin, D. Questioning the effectiveness of composite polishing systems by crosschecking profilometer and dental microscope outcomes. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 21118. [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, J.; Ferracane, J.; Paravina, R.D.; Mazur, R.F.; Roeder, L. The effect of different polishing systems on surface roughness and gloss of various resin composites. J Esthet Restor Dent 2007, 19, 214–224. [CrossRef]

- Monterubbianesi, R.; Tosco, V.; Orilisi, G.; Grandini, S.; Orsini, G.; Putignano, A. Surface evaluations of a nanocomposite after different finishing and polishing systems for anterior and posterior restorations. Microsc Res Tech 2021, 84, 2922–2929. [CrossRef]

- St Germain, H.; Samuelson, B.A. Surface characteristics of resin composite materials after finishing and polishing. Gen Dent 2015, 63, 26–32.

- Babina, K.; Polyakova, M.; Sokhova, I.; Doroshina, V.; Arakelyan, M.; Novozhilova, N. The Effect of Finishing and Polishing Sequences on The Surface Roughness of Three Different Nanocomposites and Composite/Enamel and Composite/Cementum Interfaces. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2020, 10, 1339. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Heath, J.R.; Watts, D.C. Finishing composite restorative materials. J Oral Rehabil 1990, 17, 79–87. [CrossRef]

- Botta, A.C.; Duarte, S. Jr.; Paulin Filho, P.I.; Gheno, S.M.; Powers, J.M. Surface roughness of enamel and four resin composites. Am J Dent 2009, 22, 252–254.

- Endo, T.; Finger, W.J.; Kanehira, M.; Utterodt, A.; Komatsu, M. Surface texture and roughness of polished nanofill and nanohybrid resin composites. Dent Mater J 2010, 29, 213–223. [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, K.G.; Almeida, K.G.; Medeiros, I.S.; Costa, J.F.; Alves, C.M. Effect of different polishing systems on the surface roughness of microhybrid composites. J Appl Oral Sci 2009, 17, 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Karakaş, S.N.; Batmaz, S.G.; Çiftçi, V.; Küden, C. Experimental study of polishing systems on surface roughness and color stability of novel bulk-fill composite resins. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 74. [CrossRef]

- Eguivar, Y.A.; França, F.M.; Turssi, C.P.; Basting, R.T.; Vieira-Junior, W.F. Effect of simplified or multi-step polishing techniques on roughness and color stability of resin composites. Am J Dent 2023, 36, 274–280.

- Rodrigues-Junior, S.A.; Chemin, P.; Piaia, P.P.; Ferracane, J.L. Surface Roughness and Gloss of Actual Composites as Polished With Different Polishing Systems. Oper Dent 2015, 40, 418–429. [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, S.R. The art and science of abrasive finishing and polishing in restorative dentistry. Dent Clin North Am 1998, 42, 613–627. [CrossRef]

- Gömleksiz, S.; Gömleksiz, O. The effect of contemporary finishing and polishing systems on the surface roughness of bulk fill resin composite and nanocomposites. J Esthet Restor Dent 2022, 34, 915–923. [CrossRef]

- Türkün, L.S.; Türkün, M. The effect of one-step polishing system on the surface roughness of three esthetic resin composite materials. Oper Dent 2004, 29, 203–211.

- Randolph, L.D.; Palin, W.M.; Leloup, G.; Leprince, J.G. Filler characteristics of modern dental resin composites and their influence on physico-mechanical properties. Dent Mater 2016, 32, 1586–1599. [CrossRef]

- Vinagre, A.; et al. Surface Roughness Evaluation of Resin Composites after Finishing and Polishing Using 3D-Profilometry. Int J Dent 2023, 2023, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Miyazaki, M.; Takamizawa, T.; Kurokawa, H.; Rikuta, A.; Ando, S. Influence of polishing duration on surface roughness of resin composites. J Oral Sci 2005, 47, 21–25. [CrossRef]

- Dalla-Vecchia, K.B.; Taborda, T.D.; Stona, D.; Pressi, H.; Burnett, Júnior L.H.; Rodrigues-Junior, S.A. Influence of polishing on surface roughness following toothbrushing wear of composite resins. Gen Dent 2017, 65, 68–74.

- Kamonkhantikul, K.; Arksornnukit, M.; Takahashi, H.; Kanehira, M.; Finger, W.J. Polishing and toothbrushing alters the surface roughness and gloss of composite resins. Dent Mater J 2014, 33, 599–606. [CrossRef]

- Lefever, D.; Krejci, I.; Ardu, S. Laboratory evaluation of the effect of toothbrushing on surface gloss of resin composites. Am J Dent 2014, 27, 42–46.

- Takahashi, R.; Jin, J.; Nikaido, T.; Tagami, J.; Hickel, R.; Kunzelmann, K.H. Surface characterization of current composites after toothbrush abrasion. Dent Mater J 2013, 32, 75–82. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.M.; Dória, J.; da Silva, Jde J.; Santos, G.V.; Guimarães, J.G.; Poskus, L.T. Longitudinal evaluation of simulated toothbrushing on the roughness and optical stability of microfilled, microhybrid and nanofilled resin-based composites. J Dent 2013, 41, 1081–1090. [CrossRef]

- Al Khuraif, A.A. An in vitro evaluation of wear and surface roughness of particulate filler composite resin after tooth brushing. Acta Odontol Scand 2014, 72, 977–983. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Miura, D.; Shinya, A. Influence of toothbrush abrasion on the surface characteristics of CAD/CAM composite resin blocks with shade gradations. Dent Mater J 2023, 42, 193–198. [CrossRef]

- de Gouvea, C.V.; Bedran, L.M.; de Faria, M.A.; Cunha-Ferreira, N. Surface roughness and translucency of resin composites after immersion in coffee and soft drink. Acta Odontol Latinoam 2011, 24, 3–7.

- Hamouda, I.M. Effects of various beverages on hardness, roughness, and solubility of esthetic restorative materials. J Esthet Restor Dent 2011, 23, 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, R.R.; Ribeiro, Ddos S.; Klumb, M.M.; Brandt, W.C.; Correr-Sobrinho, L.; Bueno, M. In vitro toothbrushing abrasion of dental resin composites: packable, microhybrid, nanohybrid and microfilled materials. Braz Oral Res 2008, 22, 112–118. [CrossRef]

- Tantanuch, S.; Kukiattrakoon, B.; Peerasukprasert, T.; Chanmanee, N.; Chaisomboonphun, P.; Rodklai, A. Surface roughness and erosion of nanohybrid and nanofilled resin composites after immersion in red and white wine. J Conserv Dent 2016, 19, 51–55. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.A.B.; Vitti, R.P.; Sinhoreti, M.A.C.; Consani, R.L.X.; da Silva-Junior, J.G.; Tonholo, J. Effect of alcoholic beverages on surface roughness and microhardness of dental composites. Dent Mater J 2016, 35, 621–626. [CrossRef]

- Weitman, R.T.; Eames, W.B. Plaque accumulation on composite surfaces after various finishing procedures. J Am Dent Assoc 1975, 91, 101–106. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.S.; Billington, R.W.; Pearson, G.J. The in vivo perception of roughness of restorations. Br Dent J 2004, 196, 42–45. [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.H. Effects of finishing and polishing procedures on the surface texture of resin composites. Dent Mater 1994, 10, 325–330. [CrossRef]

- Aykent, F.; Yondem, I.; Ozyesil, A.G.; Gunal, S.K.; Avunduk, M.C.; Ozkan, S. Effect of different finishing techniques for restorative materials on surface roughness and bacterial adhesion. J Prosthet Dent 2010, 103, 221–227. [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Saadaldin, S.; Rêgo, H.; Tayan, N.; Melo, N.M.; El-Najar, M. Clinical Longevity of Complex Direct Posterior Resin Composite and Amalgam Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Oper Dent 2025, 50, E30–E46. [CrossRef]

- Josic, U.; D’Alessandro, C.; Miletic, V.; et al. Clinical longevity of direct and indirect posterior resin composite restorations: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent Mater 2023, 39, 1085–1094. [CrossRef]

- Heintze, S.D.; Forjanic, M.; Rousson, V. Surface roughness and gloss of dental materials as a function of force and polishing time in vitro. Dent Mater 2006, 22, 146–165. [CrossRef]

- Maghaireh, G.A.; Alzraikat, H.; Hameed, R. Effect of Polishing Systems on Surface Roughness of Universal Resin Composites. Oper Dent 2025, 50, 431–442. [CrossRef]

| Composite Resin | Manufacturer | Shade | Type | Organic matrix | Abrasive Particles and Particles Size |

Filler (vol %, wt %) |

Batch number |

| Filtek Supreme XTE | 3M ESPE | A3E | Nanofill 5-75 nm 0.6-1.4μm |

BisGMA, UDMA, TEGDMA, PEGDMA, BisEMA | Silica (20 nm), Zirconia (4-11 nm), zirconia-silica nanoclusters (0.6-20μm) | 59.5/78.5 | N767724 |

| Polishing system | Manufacturer | Steps | Abrasive particle | Particle size |

| Hi-Luster | Kerr | 2 | GlossPlus Aluminum oxide particle-integrated polishers HilusterPlus diamond particle-integrated polishers |

GlossPlus 10 μm HilusterPlus 5 μm |

| Diamond Polishing Paste | Strauss & Co | 3 | Diamond | 2 μm (F) 1 μm (SF) 0.5 μm (XXF) |

| Enamel Plus shiny | Micerium | 3 | Diamond (A,B) Aluminum oxide (C) |

3 μm (A) 1 μm (B) 0.5 μm (C) |

| Prisma Gloss | Denstply | 2 | Aluminum oxide | 1 μm 0.1 μm |

| Diamond Polish | Ultradent | 2 | Diamond | 1 μm 0.5 μm |

| Dura-Polish DIA | Shofu | 2 | Aluminum oxide Diamond (DIA) | < 1 μm < 1 μm (DIA) |

| Diamond Twist SCO | Premier | 1 | Diamond | 3μm |

| Diamond Excel | FGM | 1 | Diamond | 2-4μm |

| DiaPolisher | GC | 1 | Diamond | < 10 μm |

| Diashine Fine | DiaShine | 1 | Diamond | < 10 μm |

| Lucida | DiaShine | 1 | Sub-micron hybrid compound | 1 μm |

| ZirconBrite | DVA | 1 | Diamond | 1 μm |

| CompoSite | Shofu | 1 | Aluminum oxide | < 1 μm |

| CompoPlus | Fegupol | 1 | Diamond | 1 μm |

| Speed polish | Harvest Dental | 1 | Diamond | N/A |

| Diabra | Fegupol | 1 | Diamond | N/A |

| Proxyt fine | Ivoclar | 1 | Pyrogenic silicic acid | N/A |

| Polishing system | Manufacturer | Polishing | Tooth brushing simulation | ||

| Sa | Sq | Sa | Sq | ||

| Hi-Luster | Kerr | 0.458a ± 0.093 | 0.533a ± 0.088 | 0.485a,b ± 0.093 | 0.533a ± 0.088 |

| Diamond Polishing Paste | Strauss & Co 15 | 0.236b ± 0.077 | 0.344b ± 0.132 | 0.299c ± 0.093 | 0.417b ± 0.122 |

| Enamel Plus shiny | Micerium 9 | 0.205b,c ± 0.065 | 0.257b,c ± 0.069 | 0.267c ± 0.072 | 0.318c,c ± 0.070 |

| Prisma Gloss | Denstply 13 | 0.223b,c ± 0.082 | 0.298b,c ± 0.126 | 0.276c ± 0.114 | 0.370b.c ± 0.124 |

| Diamond Polish | Ultradent 8 | 0.172b ± 0.070 | 0.206c ± 0.075 | 0.258c ± 0.080 | 0.320c.d ± 0.114 |

| Dura-Polish DIA | Shofu 14 | 0.215b,c ± 0.108 | 0.256b,c ± 0.091 | 0.331c ± 0.118 | 0.341b,c ± 0.092 |

| Diamond Twist SCO | Premier 7 | 0.223b,c ± 0.067 | 0.295b,c ± 0.071 | 0.337c ± 0.101 | 0.354b,c,d ± 0.056 |

| Diamond Excel | FGM 4 | 0.315c ± 0.142 | 0.350b ± 0.171 | 0.361c ± 0.142 | 0.397b,c ± 0.151 |

| DiaPolisher | GC 2 | 0.391a ± 0.135 | 0.480a,d ± 0.115 | 0.434a,b,d ± 0.100 | 0.507a ± 0.092 |

| Diashine Fine | DiaShine 11 | 0.342c ± 0.110 | 0.419d ± 0.127 | 0.363c,d ± 0.091 | 0.464a,b ± 0.109 |

| Lucida | DiaShine 1 | 0.183b ± 0.047 | 0.209c ± 0.040 | 0.266c ± 0.039 | 0.331c,d ± 0.080 |

| ZirconBrite | DVA 12 | 0.231b,c ± 0.063 | 0.321b ± 0.102 | 0.308c ± 0.104 | 0.388b,c ± 0.068 |

| CompoSite | Shofu 10 | 0.207b,c ± 0.063 | 0.261b,c ± 0.060 | 0.261c ± 0.063 | 0.359b,c,d ± 0.063 |

| CompoPlus | Fegupol 5 | 0.177b,c ± 0.053 | 0.209c ± 0.066 | 0.264c ± 0.066 | 0.294d ± 0.077 |

| Speed Polish | Harvest Dental 3 | 0.436a ± 0.060 | 0.507a ± 0.091 | 0.506a ± 0.066 | 0.557a ± 0.056 |

| Diabra | Fegupol 6 | 0.178b,c ± 0.055 | 0.220c ± 0.072 | 0.271c ± 0.060 | 0.293d ± 0.098 |

| Proxyt Fine | Ivoclar 16 | 0.420a ± 0.057 | 0.481a,d ± 0.066 | 0.458a,b,d ± 0.063 | 0.589a ± 0.069 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).