Submitted:

12 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

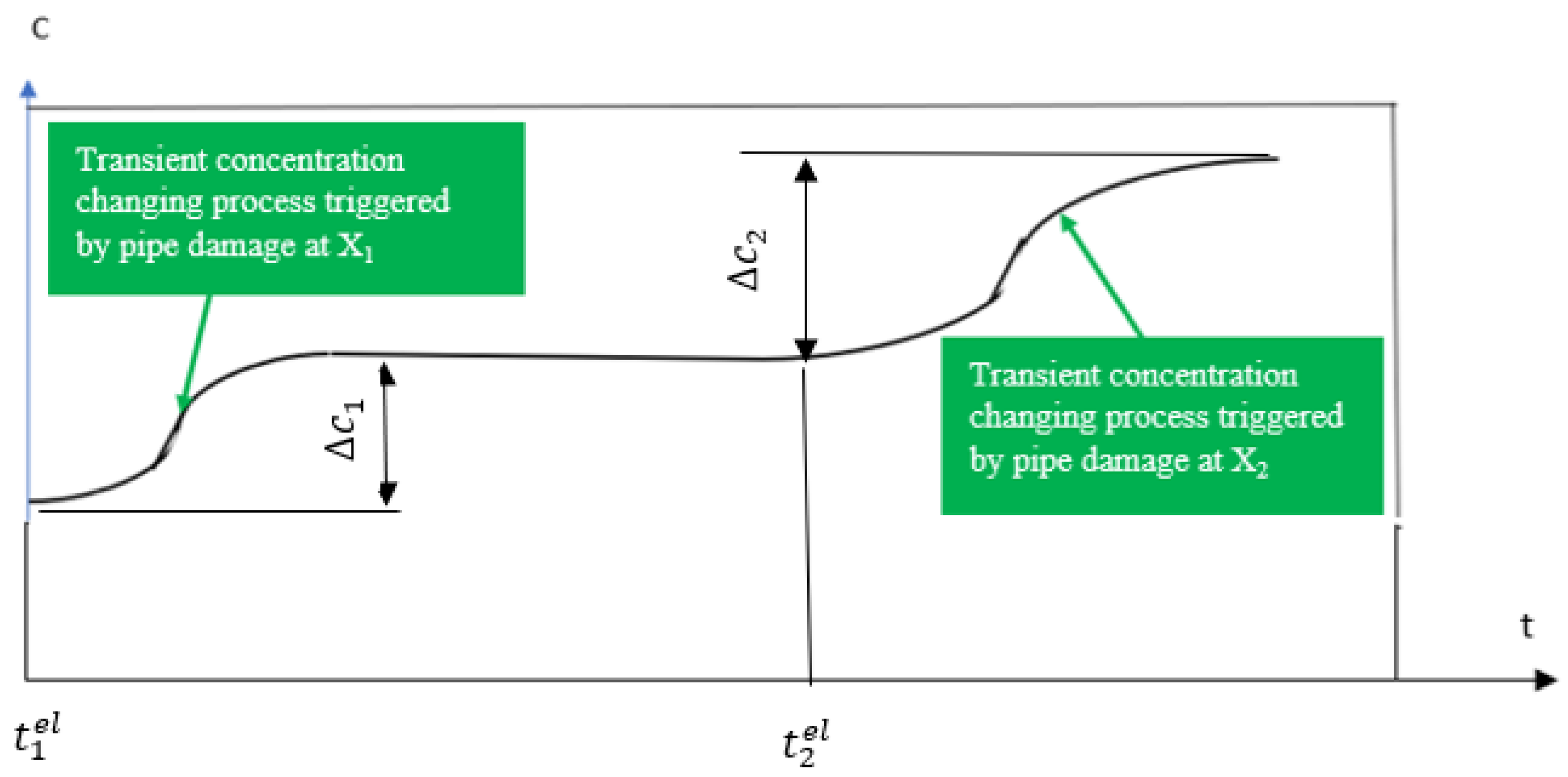

The paper introduces a machine learning method of detecting multiple sources of water contamination caused by wildfire. The method includes changing the water flow regime, monitoring the time series of the contaminant concentration caused by regime changes, and associating the signature of the contaminant changes over time with sources locations. The contaminant signature from multiple sources starting at the moment of changing water velocity are defined by extending the approach for one contamination source. The intensity, location of each source, and diffusion coefficient are defined to satisfy the minimum square between monitoring and theoretical concentrations. The equations derived from the criteria of the best fit between experimental and modeling data are solved using the theory of hypernumbers. The initial values for hypernumber solutions are computed using the transient process of contaminant transport curve analysis. The defined in this paper algorithm can by used for detecting location of the arbitrary impurity in water network system.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Contaminant Release into Water Distribution Systems as a Wildfire Consequence

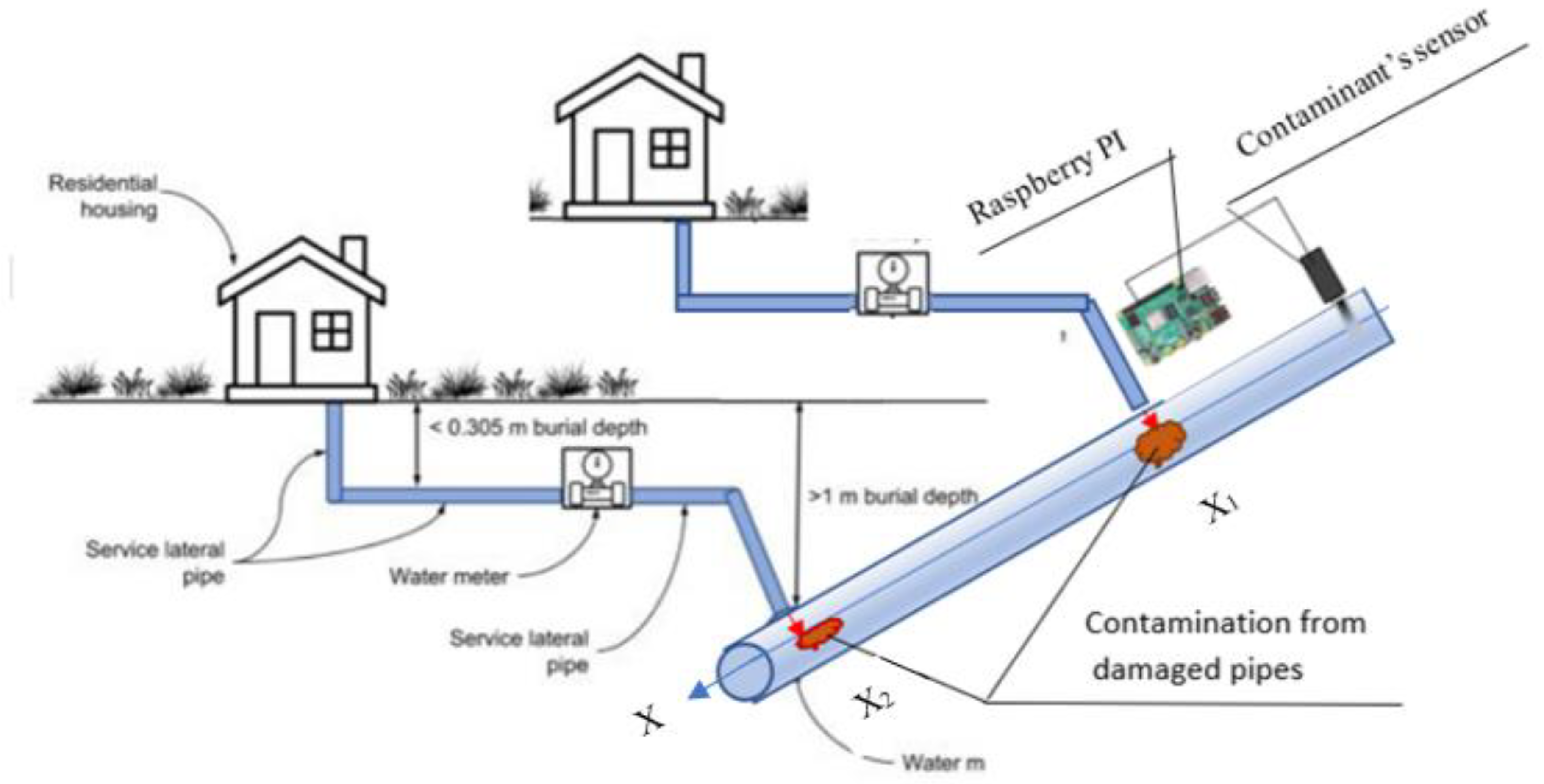

- Contaminant Release Due to Heat Damage to Pipes: Intense heat from wildfires can degrade plastic pipes and fittings, releasing volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Wildfires can introduce VOCs, such as benzene and toluene, into water systems due to the overheating plastics material (Solomon et al., 2021). Two ways overheated pipes introduce contamination are provided in recent research (Meadows, 2022). The paper lists methods for plastic pipe thermal state diagnostics. The modeling of the thermal impact on the pipe is covered in a research paper (Richter et al., 2022). The research covers experiments to determine the critical temperature and duration of heating at which contaminants migrate from pipes to contained water (Fischer, Wham, & Metz, 2022, Metz, Fischer, & Wham, 2023).

- Contaminant leaks into the pipeline due to loss of pressure: Firefighting efforts and system damage can lead to loss of water pressure, allowing contaminated water (including water containing bacteria) to be sucked into the system through leaks or damaged infrastructure (Pierce et al., 2021).

- Smoke and Ash Intrusion: As water systems lose pressure and drain, smoke containing chemicals can be drawn into the enumerate the pipes.

1.2. The Directions for Securing Pipeline from Contaminations

- The RFID sensor, which does not need batteries and, when triggered, emits a signal that can be scanned. The goal is to put RFID sensors on the laterals of the fire hydrants, which are evenly spaced throughout the communities and buried at the same depth as the vulnerable part of the laterals of the service

- Color indicator sensor to let homeowners know if they should replace their pipes after a fire.

- Deploying sensors across a complex network of pipes in fire areas where fire has a high tendency to occur might be expensive and logistically challenging.

- Maintenance and cost: The reliability and longevity of sensors in harsh environments and the potential need for frequent maintenance could be a significant factor for cost and feasibility.

2. Conclusions

References

- Burgin M, Dantsker A. Pollution information acquisition and discovering pollution sources. Journals Proceedings. 2022; 81(1).

- Burgin M, Dantsker AM. A method of solving operator equations by means of the theory of hypernumbers. Not. Nat. Acad. Sci. Kurt. 1995: 8; 27–30.

- Burgin M. Nonlinear partial differential equations in extrafunctions. Integr. Math. Theory App. 2010; 2(1): 17–50.

- Burgin M. Hypernumbers and extrafunctions: extending the classical calculus; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- Dantsker A, Burgin M. Monitoring Thermal Conditions and Finding Sources of Overheating. The 2021 Summit of the International Society for the Study of Information [Internet]. 2022 Mar 24. [CrossRef]

- Dantsker, A.; Brito, J. Leak Location Detection in Underground Pipeline Using Transient Pollutant Propagation Concentration Signature Analysis with Theory of Hypernumbers. Research & Reviews: Discrete Mathematical Structure 2025, 12(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, E. C., Wham, B. P., & Metz, A. (2022). Contaminant Migration from Polymer Pipes to Drinking Water under High Temperature Wildfire Exposure. Lifelines 2022. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, R. (2022, August 3). FEATURE: How Wildfire-damaged Plastic Pipes Contaminate Drinking water – and What We Can Do About It. MAVEN’S NOTEBOOK California Water News Central. https://mavensnotebook.com/2022/08/03/feature-how-wildfire-damaged-plastic-pipes-contaminate-drinking-water-and-what-we-can-do-about-it/.

- Metz, A. J.; Fischer, E. C.; Wham, B. P. Behavior of Service Lateral Pipes during Wildfires: Testing Methodologies and Impact on Drinking Water Contamination. ACS ES&T Water 2023, 3(2), 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, G.; Roquemore, P.; Kearns, F. Wildfire & water supply in California. 2021. Available online: https://innovation.luskin.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Wildfire-and-Water-Supply-in-California.pdf.

- Richter, E.G.; Fischer, E.C.; Metz, A.; Wham, B.P. Simulation of Heat Transfer Through Soil for the Investigation of Wildfire Impacts on Buried Pipelines. Fire Technology 2022, 58(13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Researchers warn of a threat to water safety from wildfires. (2025) ScienceDaily. Available online: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/04/250417145511.htm.

- Solomon, G.M.; Hurley, S.; Carpenter, C.; Young, T.M.; English, P.; Reynolods, P. Fire and Water: Assessing Drinking Water Contamination After a Major Wildfire. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 1878–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To Mitigate Impact of Wildfires on Communities’ Water, Report Fill Gaps in Guidance to Public Drinking Water System Staff. (2025) Lyles School of Civil and Construction Engineering – Purdue University. Available online: https://engineering.purdue.edu/CCE/AboutUs/News/Environmental_Features/to-mitigate-impact-of-wildfires-on-communities-water-report-fills-gaps-in-guidance-to-public-drinking-water-system-staff.

- Whelton, A. J.; Seidel, C.; Wham, B. P.; Fischer, E. C.; Isaacson, K.; Jankowski, C.; MacArthur, N.; McKenna, E.; Ley, C. The Marshall Fire: Scientific and Policy Needs for Water System Disaster Response. AWWA Water Science 2023, 5(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).