1. Introduction

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) is a hematological disease caused by the proliferation of monoclonal mature B lymphocytes [

1] with a prevalence of 25% to 35% of all leukemias and one of the most common forms in adults in Western countries [

1]. Patients with CLL tend to adopt sedentary behaviors due to disease symptoms as it progresses, including fatigue, shortness of breath during regular physical activity, lymph node enlargement, low-grade fever, unexplained weight loss, night sweats, feeling of fullness (related to enlarger spleen or liver) and multiple infections [

2]. As a result of these changes, there is often a notable decrease in physical fitness with the consequent decrease of overall quality of life [

3]. Additionally, the psychological impact of the disease, including anxiety and depression, further exacerbates this condition, underscoring the critical need for interventions that promote physical activity and support the maintenance of independence to perform daily activities.

Individuals with cancer are not any more likely to be physical inactive than those who never had cancer, however, in a Canadian Community Health Survey with patients with current cancer or cancer history it was found that activity levels in all studied groups were much lower than recommended [

4]. While current treatment for patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia focuses on a multifaceted approach, aiming to address both physical and psychological challenges [

5], many patients still experience significant discomfort that hinder daily functioning and reduce their quality of life [

6].

Recent studies have explored the impact of physical activity on CLL patients with research suggesting that many treatment naïve CLL patients are physically inactive and have high levels on inflammation [

7]. Regular physical activity has been shown to have significant positive effects in general population, with moderate to vigorous exercise being associated with reduced risk of infections [

8], and improving immune competence acting as a countermeasure against chronic systemic inflammation [

9], characteristics of CLL disease symptoms.

Physical activity may play a crucial role in maintaining an active lifestyle before, during and after treatment [

10,

11] and regular physical activity may improve physical function enhancing mood, self-esteem, and overall well-being [

12]. With the need for more robust research to determine the most effective exercise intervention for cancer population, many studies have already provided strong evidence supporting the prescription of exercise therapy for managing metabolic syndrome-related disorders (insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity), heart and pulmonary diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure, intermittent claudication), muscle, bone and joint diseases (osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome) as well as cancer, depression, asthma and type 1 diabetes [

13]. Several controlled trials indicate significant improvements on cardiovascular fitness with aerobic exercise [

14,

15,

16], on muscle fitness with resistance exercise [

17], with impact on immunologic response [

17,

18,

19] and cancer related fatigue [

14,

15]. Yet, in a study with a population from Canada, with 606 survivors of hematologic cancer, only 22% met combined exercise guidelines, and just 10% met strength-only guidelines [

20].

Objectively assessed physical activity with accelerometry provide accurate and objective data [

21,

22] regarding prognostic and quality of life measures such as objectively quantification of time in sedentary behavior, light and moderate to vigorous physical activity, and body position [

23,

24]. This objective data on patients’ activity levels, have been linked to better survival outcomes and lower disease symptoms [

25,

26] and by integrating this technology and data, clinicians can tailor interventions to enhance physical activity levels, potentially improving patients overall health and treatment response [

27]. This approach offers a non-invasive, continuous monitoring tool that aligns with personalized medicine initiatives in oncology [

28] facilitating the accomplishment of clinical interventions.

Regarding CLL patients, a common symptom reported by patients is fatigue. From current studies interpretation, the circadian clock has been shown to influence numerous immune cells at both the molecular and cellular levels [

29]. The maturation of neutrophils, the most common leukocytes found in human blood, is rhythmic, and their antimicrobial activity behaves in a time-of-day dependent manner [

29]. The objectively assessed physical activity may enlighten if daily physical activity in CLL patients follows this circadian clock pattern.

The aim of the current study is to explore the interaction between daily physical activity levels with disease markers (blood counts and diagnose markers of the disease) and physical and functional capacity (aerobic and muscular), to analyze how CLL patients perceive their physical and functional capacity, and to investigate if different times of the day infers on physical activity patterns in diagnosed CLL patients in treatment naïve phase.

2. Results

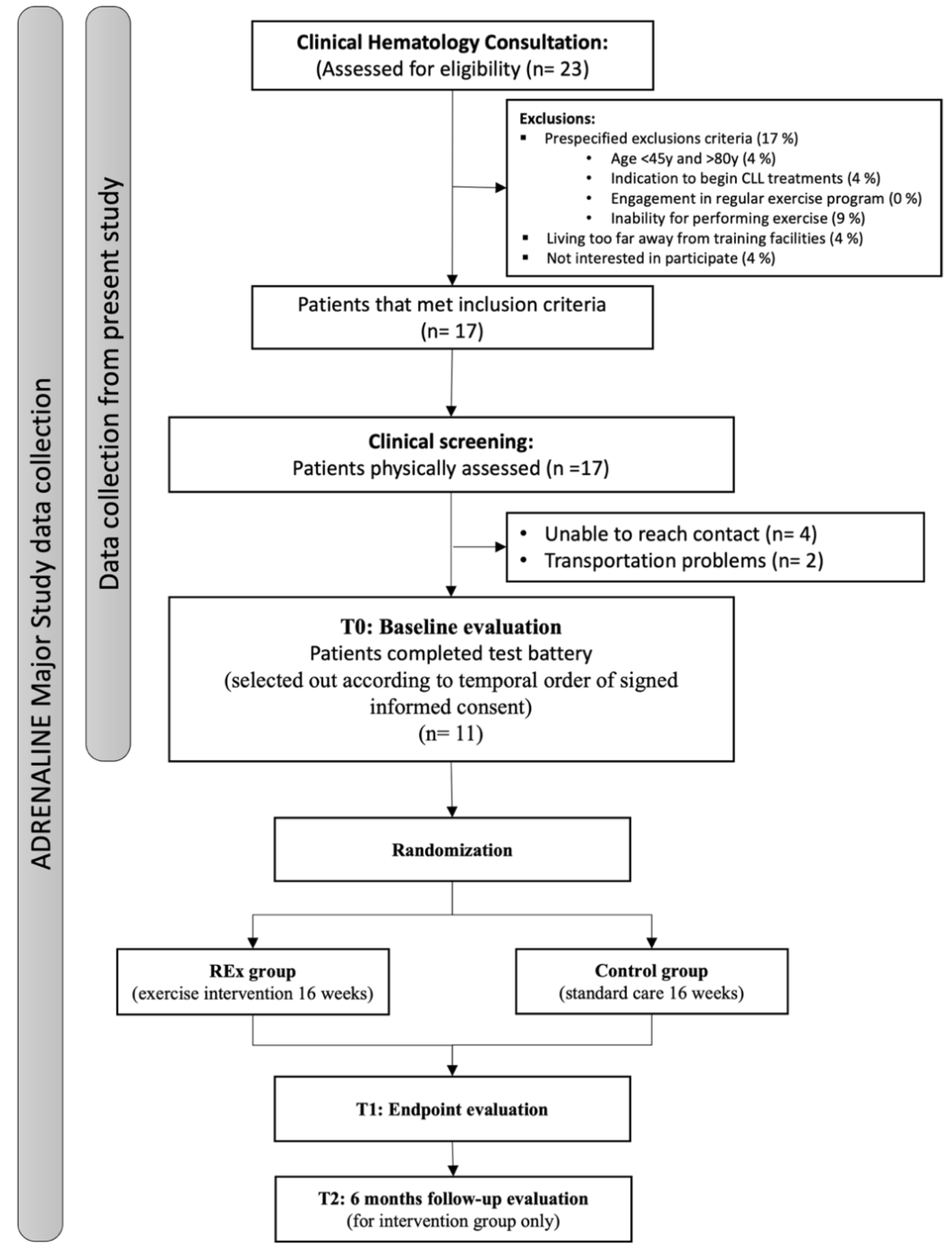

During the recruitment phase, from September 2023 until August 2024, twenty-three patients were assessed for eligibility in clinical hematology consultation, with 6 patients excluded due to not meeting inclusion criteria. After clinical screening we were unable to reach contact with 4 patients, while another 2 referred transportation issues to comply with physical fitness screening. Eleven participants were consented into the study. The complete flowchart can be consulted in

Figure 1.

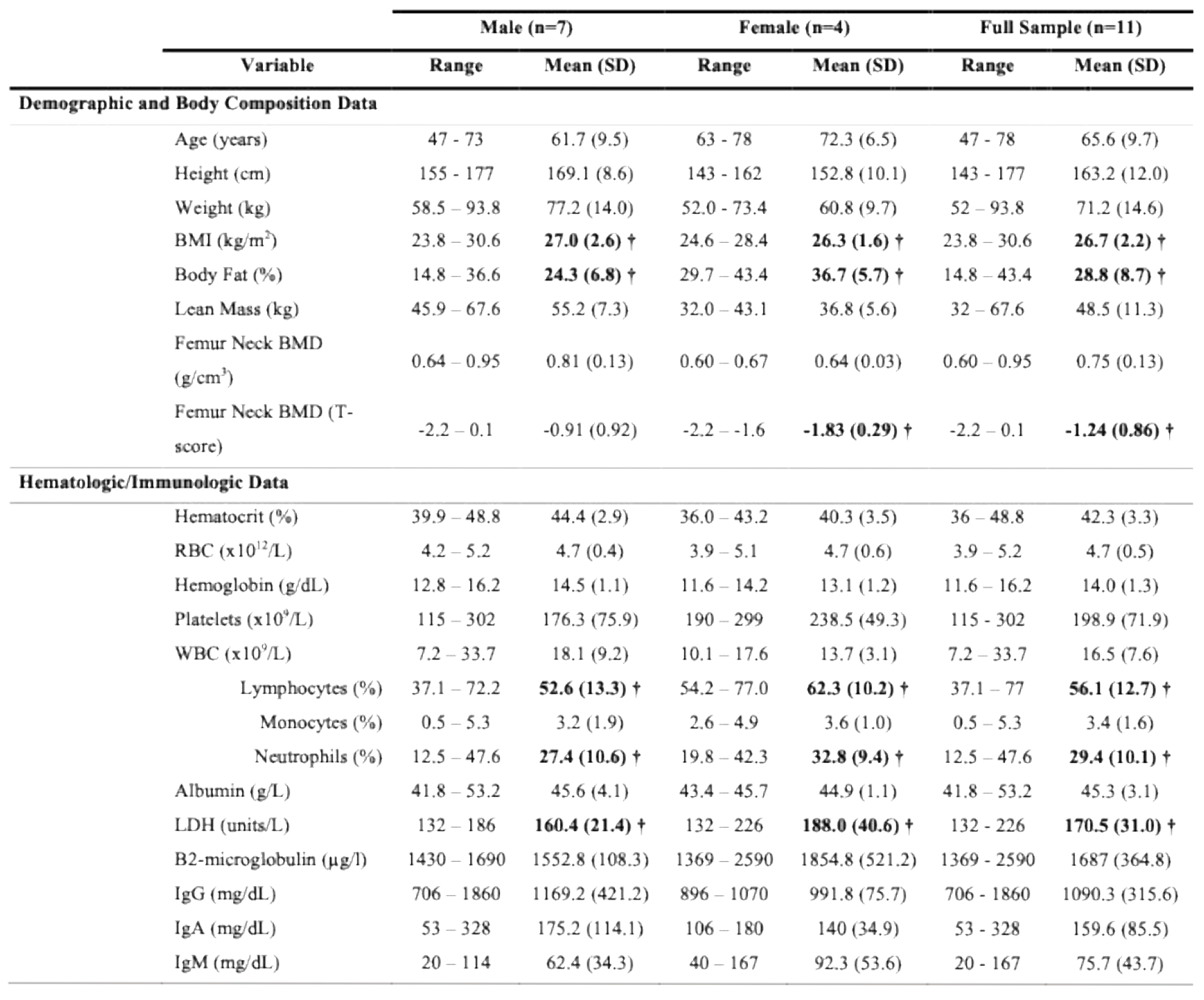

Total sample comprised eleven participants, 7 men and 4 women with mean age of 65.55 (±9.73) (range: 47-78) years. Regarding baseline characteristics for body composition, this group of patients presents above weight recommendations with overall average BMI = 26.72 (2.22), and slightly overfat with body fat percentage for male and female patients of 36.7 (5.7) and 24.3 (6.8) percent, respectively. Regarding bone health, measured by DEXA, female group is in osteopenia stage (T-score less than -1 SD from normal values), while in male group only 3 patients reveal this condition. None of the patients reveal osteoporosis, however only 4 (36.4%) patients revealed healthy bone measures. Differences between genders show relevant statistical significances in height, body fat percentage, lean mass and femur neck bone mineral density, favoring male participants.

Overall mean time since diagnosis was 3.65 (range: 1.12-10.31) years. Participants were mostly on RAI stage I (54.5%), BINET stage A (72.7%) and ECOG status 0 (63.6%). Due to inclusion and exclusion criteria, this was expected, since patients were in surveillance phase, without treatment.

When analyzing the measured hematologic parameters, patients show percentages of lymphocytes counts above normal values (expected in CLL disease), while neutrophils appear particularly low [40.0% (11.7)]. Regarding immunologic parameters, only 1 patient revealed unfavorable prognostic with B2-microglobulin above 2.5 µg/l, an indicator of high tumoral charge and disease activity, while immunoglobulins appear controlled, with favorable values indicating low risk for infections. The complete description, at baseline, of Demographic, Body Composition, Hematologic and Immunologic data can be consulted in

Table 1.

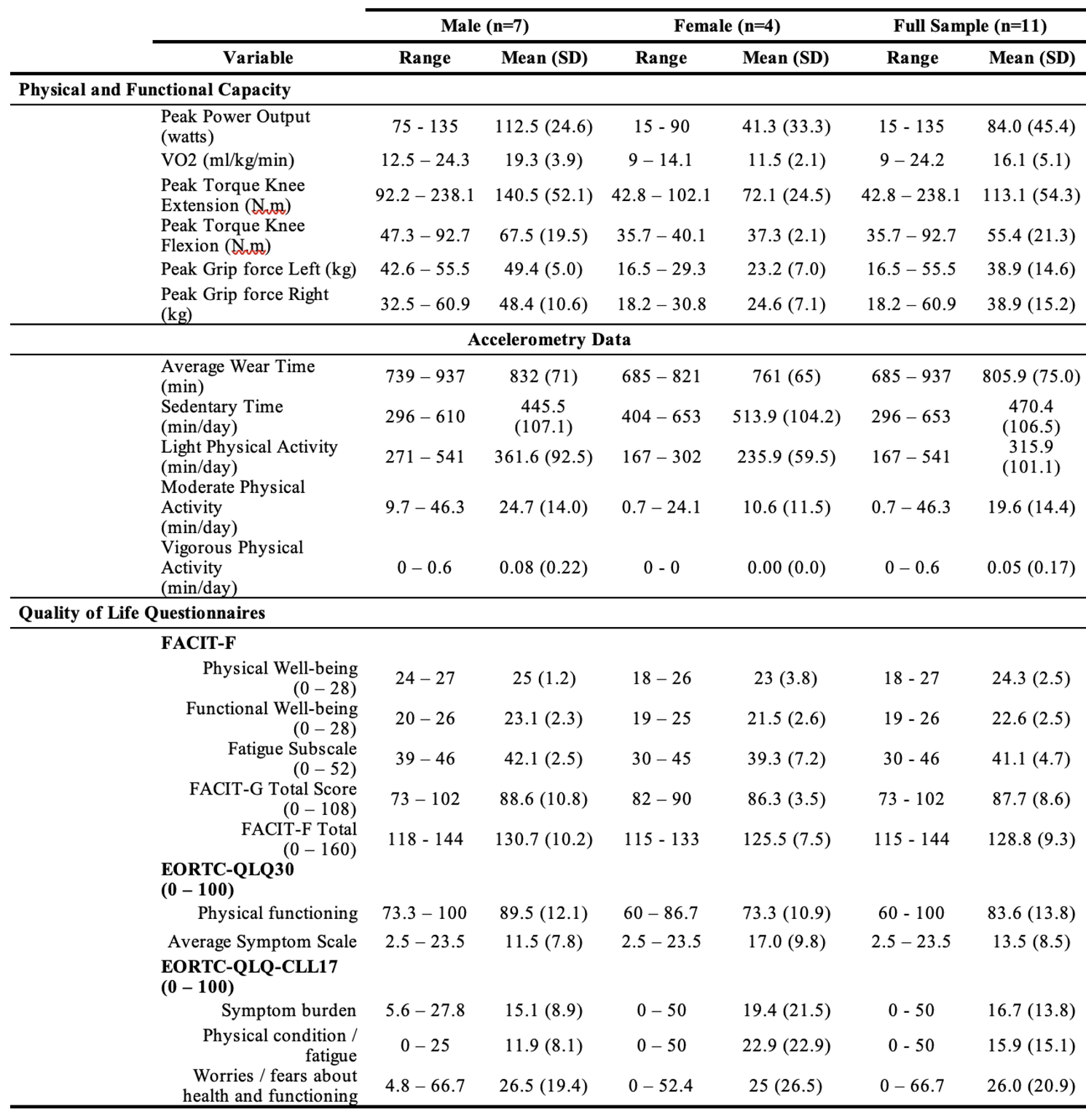

Regarding Physical Fitness parameters, this group of patients revealed a very low cardiovascular capacity with mean values of 16.1 (5.1) ml/kg/min ranging between 9.0 and 24.3 ml/kg/min VO2peak. None of the patients exceeded 135 watts of peak power in the cycle ergometer maximal test, reaching 85% maximal heart rate criteria, with a mean value of 84 (45.4) watts. Regarding strength characteristics, a peak torque knee extension of 113.1 (54.3) N.m and flexion of 55.4 (21.3) N.m reveal a ratio of 52.6% between agonist/antagonist. Differences between genders show relevant statistical significances in all physical fitness parameters, favoring male participants.

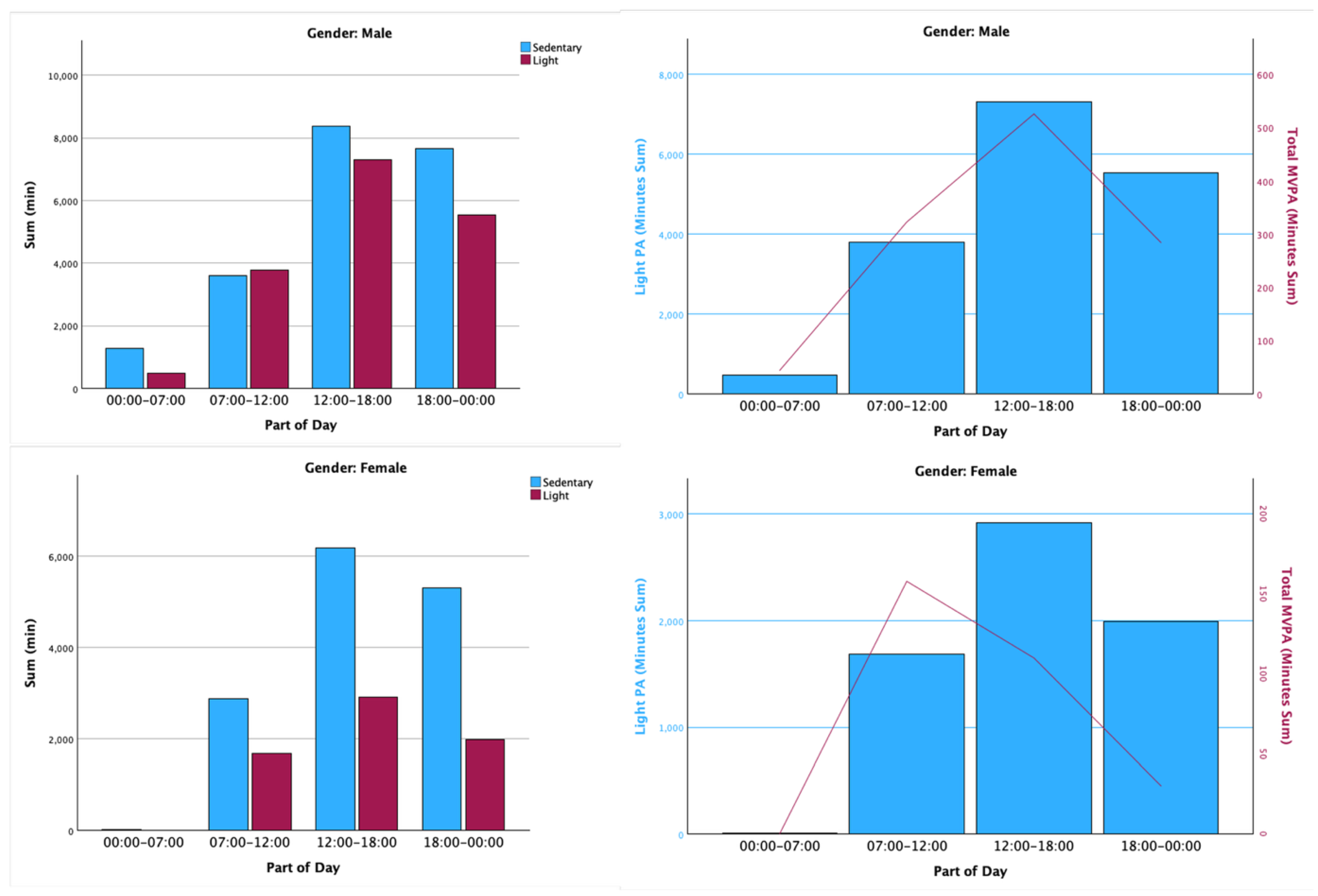

Concerning accelerometry, participants have coped with a minimum of 4 weekdays and 1 weekend day established as inclusion criteria for analysis. So, for this group of patients, the usability and feasibility of the wearable device wear were accomplished, exceeding it. When analyzing sedentary behavior, the patients spent 58% of their time in this behavior, while light, moderate and vigorous physical activity counts for 39%, 2.4% and approximately 0%, respectively. When exploring daily physical activity and sedentary time, male patients revealed less sedentary time and more physical activity when compared to female patients, with male groups showing 53.5% of the time in sedentary behavior while the female group showed 67.5%. When comparing light and moderate-to-vigorous PA, both genders reveal more light PA between 12h00 and 18h00, but patterns of moderate-to-vigorous PA are different between genders, with female group revealing more MVPA between 7h00 and 12h00, while in male group appears to be around 12h00 until 18h00, as depicted in

Figure 2.

When analyzing quality of life questionnaires our data reveal that in the EORTC, patients have a perception of high physical functioning 83.63 (13.79), also in line with FACIT-F with the perception of high physical well-being of 24.27 (2.49) of a maximal 28 points. The complete description of baseline of Physical and Functional capacity, Accelerometry and Quality of Life data can be consulted in

Table 2.

When analyzing the influence of MVPA on the outcomes of CLL patients, higher MVPA levels were associated, albeit without statistical significance, with a tendency toward lower B2-microglobulin levels and resting systolic blood pressure, as well as higher lean mass, BMI, and strength-related parameters, including left- and right-hand grip strength and isokinetic extension and flexion strength.

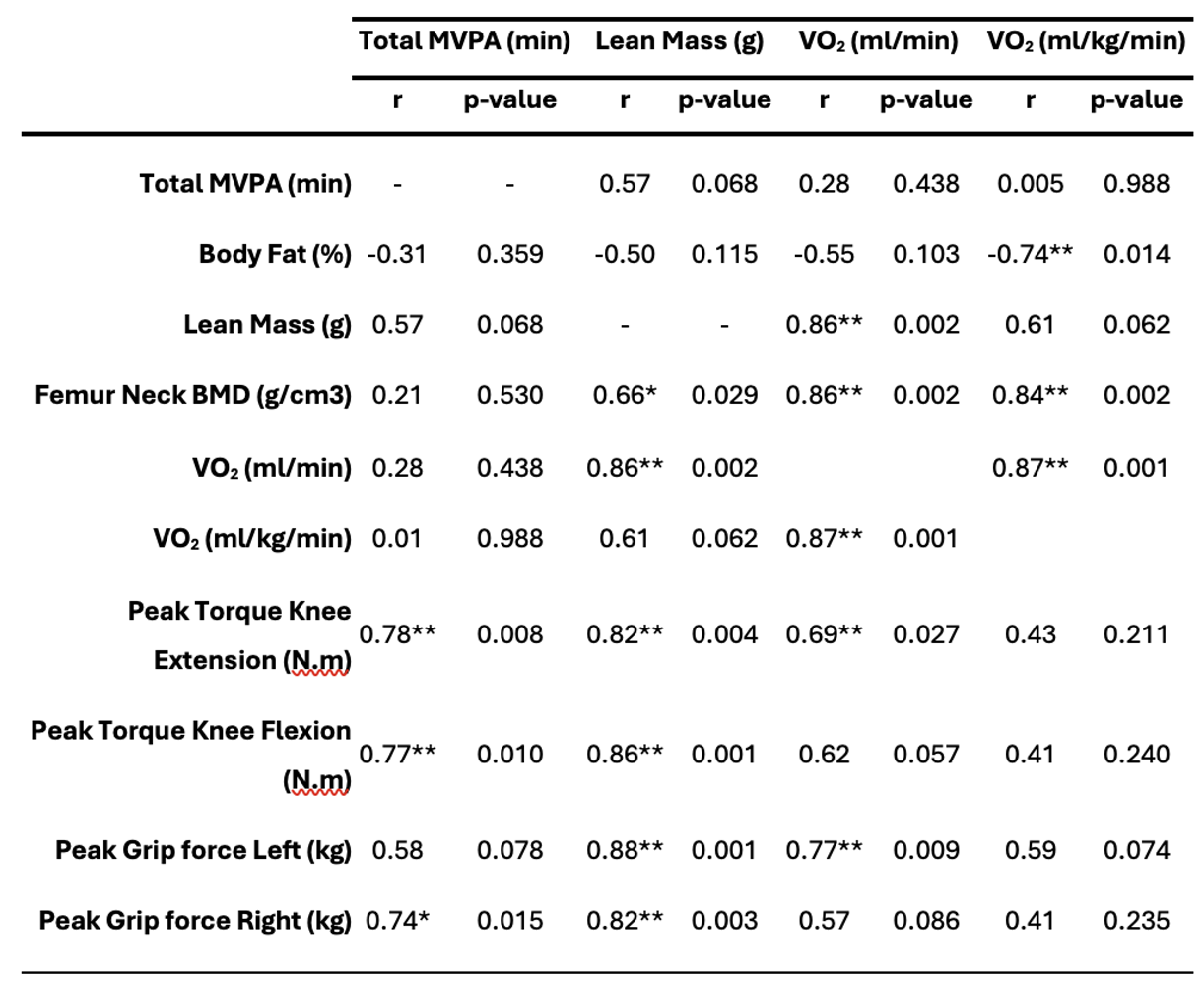

High positive correlations with statistical significance were found between total MVPA and peak torque knee extension (r = 0.78, p = 0.008), peak torque knee flexion (r = 0.77, p = 0.010), grip strength of right hand (r = 0.74, p = 0.015); and between Lean Mass and Femur Neck Bone Mass Density (r = 0.66, p = 0.029), VO2peak (r= 0.86, p=0.002), Peak Torque Knee (Extension (r= 0.82, p=0.004) and Flexion (r=0.86, p=0.001)), Peak Grip Force [Left (r= 0.88, p=0.001) and Right (r=0.82, p= 0.003)]. The association between Lean Mass and MVPA (r=-0.45 and r=-0.54 respectively) with B2-microglobulin disease marker revealed a negative medium correlation, but without statistical significance. The complete description of correlations can be found in

Table 3.

3. Discussion

The early dissemination of study baseline data offers important contributions to the understanding of CLL in treatment naïve stage characteristics. The data collected to date offers valuable insights into the initial profile of patients, allowing sample characterization and identification of initial trends, that may diverge from common knowledge from available literature and clinical practice. The present study addresses the characteristics of diagnosed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia patients in “watch and wait” phase and the relation between PA levels with significant health outcomes, without implemented immunochemotherapy treatment or indication for treatment initiation.

Participants revealed values above baseline normative data in healthy populations regarding the percentage of body fat parameter. Considering that there are no universally accepted norms for body fat percentage, according to ACSM an optimal range of 10%-22% and 20%-32% for men and women, respectively, has long been viewed as satisfactory for health [

48]. This group of patients, slightly above with 24.3% and 36.7% of body fat for men and women, respectively, reveal a factor that may impact symptom burden, since correlations of present data suggest a statistically significant association between body fat percentage and VO2peak, Fatigue, Physical Functioning and Average Symptom Burden (last one with median correlation without statistical significance), also in line with available studies with CLL population [

14,

15,

17].

The unfavorable body composition profile may be partially explained by the Physical Condition parameter, where this group of patients revealed a low cardiovascular fitness, with the best test value in our overall sample of 24.3 ml/kg/min VO2peak, taken by a male patient nevertheless still below the minimal expected for a healthy female adult which is of 27 ml/kg/min according to literature [

48]. Current knowledge advises that the increment in VO2 is associated with lower levels of fatigue [

14,

15], higher levels of muscular resistance and bone mineral density [

14,

15,

16], improving physical functioning and well-being [

12], which may directly impact daily tasks, maintaining daily physical activity, and reducing disease-related fatigue.

One factor that remains underexplored, is the influence of strength and muscle mass on CLL patients. Several studies show a preference for low-moderate intensities or endurance effort on resistance training (65-70% of 1-RM), but as the literature suggests, exercise-induced myokines production may have a critical role in increasing cytotoxicity and the infiltration of immune cells into the tumor [

49]. When comparing aerobic-only, Strength and Combined Guidelines in the Hazard Ratio for All-Cause Mortality, strength training was considered better than Aerobic in the case of cardiovascular disease mortality and in cancer mortality, where isolated strength training was shown to be the better option compared to other modes of training [

50]. The presence of low muscle mass when compared to healthy adults [

51] is similar between our study and other interventions with exercise training in CLL patients; however, there are still few studies addressing the use of strength training on CLL patients. In our data, correlation analysis suggests that greater muscle mass is strongly associated with higher strength levels in patients with CLL, similar to what is observed in the general population. Given that one of the major symptoms of the disease is the loss of weight, this underscores the potential importance of incorporating strength training into the management of CLL to keep muscle mass and physical function. Given that training intensity can influence long-term adherence, strength training—using weights at approximately 75–85% of one-repetition maximum—may be better tolerated than continuous aerobic endurance training. This is particularly relevant as fatigue and dyspnea during routine physical activity are among the most prominent symptoms of disease progression. The structure of strength training, which typically involves short sets with extended rest intervals (60–90 seconds), may facilitate greater respiratory comfort and improve exercise adherence.

One of the factors that may influence the auto-conscience for this problem is that when analyzing the quality-of-life questionnaires, the individuals do not report significant symptoms impairing their daily life quality. However, their perception of high physical functioning does not align with their fitness levels. Several longitudinal studies show that a higher perception of physical functioning by the CLL patient is very close to healthy control values [

52,

53]. When crossing this data with interventions with exercise with CLL patients, we can confirm this tendency. In a study from Artese et al. [

54] data show that CLL patients with 31% of body fat, VO2 of 26.7 ml/kg/min., considered their Physical Well-Being and Functional Well-Being with a value of 27 and 25.7 (in a scale from 0-28), respectively; in another study from Furzer et al. [

15], patients with 34.6% body fat and16.10 in 75% VO2/kg reported a FACT-G score of 82 (in a scale from 0-108); another study with a wider sample of patients, but that also included CLL patients, Courneya et al. [

14] found a value in FACT-An of 147.1 (in a scale from 0-188) in a group with 32.6% body fat and a VO2 of 25.4 ml/kg/min.

One piece of evidence that arises from our data is that MVPA is not significant with any parameter besides lymphocyte percentage. Even after exploring data with median and tertile ranking, MVPA appears to have no impact on disease parameters. Nevertheless, in our sample, the hours of peak MVPA and light PA lays between 7:00 and 18:00, in line with the latest studies, that speculate a lower risk of incidence of cardiovascular diseases and cancer risk for those who are active between this timeline [

55,

56]. The protective effect of chronoactivity may be one variable, but we cannot disregard that, besides the low number of patients in our sample, the lack of minutes in MVPA recommended from major organizations [

48,

57], defining at least 150min of moderate to vigorous activity per week, is critically low in our study barely reaching 19.61 minutes per day in this intensity, not according to available literature that explores the association of CLL and physical activity patterns [

17,

58] who got higher values of objectively measured daily physical activity.

Regarding immunologic parameters, when comparing our sample values with normative values for Portugal healthy population [

59], our CLL sample only presents above normal in Lymphocytes and Neutrophils percentage, with patients showing percentages of Lymphocytes high and above normal values (expected in CLL disease), and Neutrophils appearing particularly low revealing increased risk for infections. Literature concerning immunologic parameters of CLL patients in exercise interventions are scarce. As far as our knowledge, when comparing with the two available studies that implement immunologic analysis from Crane et al. [

18] and Macdonald et al. [

17], our sample present similar values for main serologic data, differing only with lower white blood cells counts, lower lymphocytes and monocytes percentages, higher neutrophils percentages, lower B2-microglobulin, lower LDH and Albumin. This may impact in future study analysis, because our sample of patients reveal a more favorable diagnostic of disease.

We recognize that limitations arising from ongoing recruitment may impact the generalizability of findings and the statistical power of the analysis. However, data presented in present study establishes a baseline analysis for CLL treatment naïve patients.

4. Materials and Methods

Study Design

The rAndomiseD contRollEd cliNical triAL of exercIse as Intervention in chroNic lymphocytic leukEmia (ADRENALINE), is a single-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) study. The present manuscript reports baseline data from the undergoing research project, before randomization.

Patients with confirmed CLL, with stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, were consecutively recruited at the Hematology Department in the participating Hospital (São João University Hospital Center), which represents the largest hospital in the Porto region (Portugal). The data on the present study, regarding initial evaluations (T0) of the ADRENALINE study and data collection, refers from September 2023 until August 2024. At this moment (T0 evaluation), no exposure to the ADRENALINE concept was done, neither follow-up.

The study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committees of São João University Hospital Center and the Faculty of Sport from the University of Porto. All patients provided written informed consent upon recruitment to participate in the study. The ADRENALINE trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Participants

All patients received a screening assessment including medical history, blood chemistry and hemogram, and physical examination (for skin pallor, palpable cervical lymph nodes, and hepatomegaly) during Hematology routine workup, before the assessment of health-related quality of life using questionnaires and fitness assessments. Objectively assessed levels of daily physical activity were acquired after baseline assessments using accelerometry technology to collect data on the Physical Activity (PA) patterns of participants over a period of seven consecutive days, with a minimum of 10 hours of daily assessment.

Inclusion criteria comprise a confirmed CLL diagnostic as per the International Workshop on CLL Guidelines [

30], age between 45-80 years old, no history of previous treatment of CLL, ability to walk on a treadmill or cycle on an ergometer, ability to carry weights or use weight machines, that have passed initial evaluations (Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test + Electrocardiogram (CPET+ECG) for cardiac health and dynamometer for muscular health), and with a signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria included previous immunochemotherapy CLL treatments, ongoing engagement in a regular exercise program, an indication of disease progression or for starting treatment within 6 months (according to recommendations of the International Workshop on CLL Guidelines), other primary tumors, inability to perform exercise (heart, advanced stage respiratory, renal, hepatic, neurological or osteoarticular disease), and unable to travel to facilities or to comply with other study requirements.

Figure 1 demonstrates the patient recruitment and data collection of the present study within the development of the ADRENALINE study.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Primary outcomes encompass the characterization of objective levels of physical activity, using accelerometry and quality of life and well-being, using questionnaires, body composition measures, anthropometric, strength evaluation, cardiac and respiratory capacity.

Secondary outcomes includes medical assessments performed by clinicians during the routine Hematology consultation before the baseline evaluations, including disease-related symptoms/complications, physical exam (for skin pallor, palpable cervical lymph nodes, and hepatomegaly) and clinical exams.

Evaluation

Exercise testing

At baseline, patients were evaluated on: i) anthropometric, body composition measures and bone mineral density; ii) strength; iii) cardiac and respiratory CPET on a cycle ergometer with a stress electrocardiogram with spirometry.

The CPET performed to assess cardiorespiratory fitness and potential cardiovascular and cardiorespiratory limitations followed international guidelines concerning standardization and interpretation strategies [

31]. The CPET was performed on a cycle ergometer Lode Corival CPET (Lode, The Netherlands) under the supervision of a sports physician. Throughout the test, the Electrocardiogram (ECG) and blood pressure were monitored, and heart rate (HR) and gas exchange variables were recorded continuously, averaged at 30-second intervals (COSMED Quark CPET, Rome, Italy). The protocol comprehends 2 minutes rest without movement, for respiratory adaptation, followed by a 3-minute warmup unloaded phase at 60 revolutions per minute (RPM) and zero watts. After warmup, the incremental exercise phase is initiated, with each step incrementing 15 watts per minute until 85% heart rate is achieved or other standardized criteria for stopping occurs [

31]. After the incremental phase, the recovery phase took place with 2 minutes of active cool down with unloaded pedaling followed by 3 minutes of passive cool down without movement [

32]. The highest recorded oxygen uptake (VO2peak) was used as an indicator of cardiorespiratory fitness. VO2peak represents the highest oxygen consumption achieved during the test rather than a true maximal effort. This approach is commonly used when maximal exertion is not feasible, particularly in clinical populations.

Upper extremity muscle strength was assessed using a handgrip dynamometer JAMAR PLUS (Sammons Preston, Chicago IL), calibrated according to standard protocols, and using 3 trials for each hand, with a contraction of 2-4 seconds, and with 30 seconds interval between attempts [

33,

34]. For lower muscle strength it was used an Isokinetic Dynamometer BIODEX 850-000 System 4 Pro (Biodex Medical Systems, USA) following the standard procedures recommended by standard protocols, measuring Extension/Flexion of the dominant knee, and using the protocol Concentric/Concentric with 60 deg/s speed to evaluate strength, with 5 repetitions warmup and 3 repetitions for maximal effort after 1-2 min rest between warmup and maximal effort [

35].

Data collection of height and body mass were determined by standard anthropometric methods (SECA 217 stadiometer and SECA 899 digital floor scale). Body mass index was calculated from the ratio weight/height2 (kg/m2). Body composition and bone mineral density were collected using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry [DEXA scans (Horizon Wi, Hologic)], to quantify percent body fat, fat mass, trunk fat mass, fat-free mass and bone mineral density (from whole body test) and hip bone mineral density (from non-dominant hip side).

Objectively assessed levels of physical activity (PA) were acquired using the GT9XLink accelerometer (Actigraph, USA) to collect data on the PA patterns of participants over a period of seven consecutive days, with a minimum 4 weekdays and 1 weekend day and of 10 hours of daily assessment [

36]. Accelerometers were worn on the dominant side over the hip and aligned with the kneecap, and patients were instructed to use them all day long except during baths, water sports, potential hazard activities, or during sleep. A report sheet for the description of daily accelerometer usage was also provided.

All the referred tests were conducted at lab facilities, with medical surveillance during physical fitness protocols.

Clinical, Immunologic and Inflammatory testing

Clinicians performed clinical assessments during routine hematology consultations comprising standardized clinical assessments, including exercise- and disease-related symptoms/complications, hemogram and blood chemistry (hepatic, renal, mineral and metabolic markers), and physical exams (for skin pallor, palpable cervical lymph nodes, and hepatomegaly). Pre-intervention disease markers for characterization of CLL were also available (LDH, beta2-microglobulin, immunoglobulins, immunophenotyping and B cells characterization measurements). The CLL staging index (RAI and BINET) [

37,

38], and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Scale (ECOG) [

39] were used due to typical clinical practice of participating hospital. The genetic characterization of the disease (needed for the CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI)) is not available since genetic markers are only asked when the disease criteria evolve to treatment phase.

Quality of Life

At baseline, two self-reported questionnaires were used to assess clinical status, well-being and quality of life: the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) [

40] to evaluate Well-Being, and where the maximum score is 160, with higher scores indicating greater Well-Being for all domains; and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaires Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [

41] with the Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Module (EORTC QLQ-CLL17) evaluating Health-Related Quality of Life (QoL) and where high score for a functional scale represents a high/healthy level of functioning, a high score for the global health status / QoL represents a high QoL, but a high score for a symptom scale/item represents a high level of symptomatology/problems.

BIAS

Risk of BIAS was assessed with the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cross-Sectional Studies [

42], part of the Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tools. This checklist is specifically designed for cross-sectional studies, such as the present research, which assesses baseline differences between male and female participants. It evaluates potential biases in sample selection, measurement reliability, and statistical analysis. Additionally, it helps ensure the comparability of groups and the validity of data collection methods, thereby strengthening the study’s methodological rigor.

Statistical Methods

Sample size calculation for the major ADRENALIN study (GPower software) was based on the means and standard deviations of prior studies [

43]. An initial estimation indicated that a minimum of 16 subjects was required to detect differences with a power of 95% and a significance level of 5% (two-tailed). However, due to external constraints beyond our control—such as the distance between participants’ residences and training facilities, as well as the challenge of recruiting treatment-naïve patients without pharmacological intervention—only 11 participants were included in the study. A post-hoc power analysis revealed a statistical power of 66.7% for detecting an effect size of 0.8. While this is below the conventional threshold of 80%, the significance of observed effects remains valid, as meaningful differences were detected despite the reduced sample size.

Descriptive statistics are presented as means and standard deviations (SD), or median and inter-quartile range. Normality analysis was conducted using the Shapiro-Wilk test. T-Test was employed to analyze differences between genders. To analyze the relationship between variables, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated, and all assumptions for Pearson correlation were checked and met. To evaluate the influence of Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity (MVPA), the participants were divided into tertiles based on their MVPA levels, creating three groups to compare the most active and the least active individuals. Parametric (ANOVA) and non-Parametric (Kruskal-Wallis) tests were deployed to verify differences across these groups for continuous variables and goodness-of-fit chi-square for categorical. Effect size was assessed using Hedges’ g scores (due to tendency of hyper estimation with Cohen’s d effect size on small samples), where values of 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 were considered small, medium, and large effects, respectively [

44]. Significance was maintained at p < 0.05.

For the questionnaire subdomains and composite scores, we followed recommendations from the authors (EORTC [

41] and FACIT [

40]) and similar exercise studies in cancer [

45,

46,

47]. Therefore, in line with recommendations and the independence of each subdomain, no adjustments for multiple comparisons between subdomains were performed.

Accelerometry analysis was conducted using the algorithm Troiano (2007) defining non-wear period with minimum length of 60 minutes, with spike level to stop at 100 counts per minutes, over seven consecutive days, with a minimum four weekdays and one weekend day and of 10 hours of daily assessment [

36]. For scoring algorithms, it was used Freedson VM3 2011 for energy expenditure, Freedson Adult 1998 for METs, and Troiano Adult 2008 for Cut Points and MVPA.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS mac version 29 (Armonk, NY, United States), and accelerometry analysis were conducted using Actigraph Actilife version 6.13.6 (Pensacola, FL, United States).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrate that our sample of patients with CLL in treatment naïve phase present values above baseline normative data for healthy populations in the body composition parameter, fact that may be explained by the Physical Condition parameter, where this group of patients revealed a low cardiovascular fitness. We also show that, for this sample of patients, they do not report significant symptoms impairing their daily life quality due to their perception of high physical functioning unaligned with their fitness levels. Our data, reflects that greater muscle mass appears to be strongly associated with higher strength levels in patients with CLL, similar to what is observed in the general population. Although there is an increasing body of literature that links exercise training, muscle function and immune functions in older adults, the effects of strength training on CLL patients remains underexplored. Given that one of the major symptoms of the disease is the loss of weight, this underscores the potential importance of incorporating strength training into the management of CLL to keep muscle mass and physical function, and further studies who can measure the outcomes in physical fitness, quality of life and well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C.; methodology, P.C.; validation, J.R.; investigation, P.C.; resources, J.M. and J.R.; data curation, P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.; writing—review and editing, R.R., A.P., J.M. and J.R.; supervision, R.R. and J.R.; project administration, P.C. and J.R.; funding acquisition, P.C., J.M. and J.R.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Fellowships Research for Doctorate granted by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT - National Public Agency from Portugal) (FCT grant n.: 2021.07178.BD: DOI 10.54499/2021.07178.BD), and as sources of Outside Support for Research, we had support with equipment’s and facilities by Research Center in Physical Activity, Health and Leisure (CIAFEL) - Faculty of Sports-University of Porto (FADEUP) and Laboratory for Integrative and Translational Research in Population Health (ITR) (CIAFEL UIDB/00617/2020: doi:10.54499/UIDB/00617/2020 and ITR: LA/P/0064/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Centro Hospitalar de São João (CE 431-19), and by the Faculty of Sport - University of Porto (CEFADE 14_2024), and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the present study will not be publicly available but can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CLL |

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| PA |

Physical Activity |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| |

|

References

- Ou, Y., et al., Trends in Disease Burden of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia at the Global, Regional, and National Levels From 1990 to 2019, and Projections Until 2030: A Population-Based Epidemiologic Study. Front Oncol, 2022. 12: p. 840616.

- Yao, Y., et al., The global burden and attributable risk factors of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2019. Biomed Eng Online, 2022. 21(1): p. 4.

- Artese, A.L., et al., Quality Of Life Changes Following High-intensity Interval Training In Older Adults With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 2022. 54(9): p. 157-158.

- Neil, S.E., C.C. Gotay, and K.L. Campbell, Physical activity levels of cancer survivors in Canada: findings from the Canadian Community Health Survey. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 2014. 8(1): p. 143-149.

- Veliz, M. and J. Pinilla-Ibarz, Treatment of relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Control, 2012. 19(1): p. 37-53.

- Shanafelt, T.D., et al., Quality of life in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an international survey of 1482 patients. British Journal of Haematology, 2007. 139(2): p. 255-264.

- Sitlinger, A., et al., Exercise and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) - Relationships Among Physical Activity, Fitness, & Inflammation, and Their Impacts on CLL Patients. Blood, 2018. 132: p. 3.

- Chastin, S.F.M., et al., Effects of Regular Physical Activity on the Immune System, Vaccination and Risk of Community-Acquired Infectious Disease in the General Population: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine, 2021. 51(8): p. 1673-1686.

- Krüger, K., F.C. Mooren, and C. Pilat, The Immunomodulatory Effects of Physical Activity. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 2016. 22(24): p. 3730-3748.

- De Backer, I.C., et al., Long-term follow-up after cancer rehabilitation using high-intensity resistance training: persistent improvement of physical performance and quality of life. Br J Cancer, 2008. 99(1): p. 30-6.

- Chen, L.J., et al., The effects of exercise on the quality of life of patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on the QLQ-C30 quality of life scale. Gland Surgery, 2023. 12(5): p. 633-650.

- Campbell, K.L., et al., Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2019. 51(11): p. 2375-2390.

- Pedersen, B.K. and B. Saltin, Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in chronic disease. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 2006. 16: p. 3-63.

- Courneya, K.S., et al., Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Physical Functioning and Quality of Life in Lymphoma Patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2009. 27(27): p. 4605-4612.

- Furzer, B.J., et al., A randomised controlled trial comparing the effects of a 12-week supervised exercise versus usual care on outcomes in haematological cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 2016. 24(4): p. 1697-1707.

- Nadler, M.B., et al., The Effect of Exercise on Quality of Life, Fatigue, Physical Function, and Safety in Advanced Solid Tumor Cancers: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 2019. 58(5): p. 899-+.

- MacDonald, G., et al., A pilot study of high-intensity interval training in older adults with treatment naive chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 23137.

- Crane, J.C., et al., Relationships between T-lymphocytes and physical function in adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results from the HEALTH4CLL pilot study. European Journal of Haematology, 2023. 110(6): p. 732-742.

- Sitlinger, A., D.M. Brander, and D.B. Bartlett, Impact of exercise on the immune system and outcomes in hematologic malignancies. Blood Advances, 2020. 4(8): p. 1801-1811.

- Vallerand, J.R., et al., Correlates of meeting the combined and independent aerobic and strength exercise guidelines in hematologic cancer survivors. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2017. 14.

- Troiano, R.P., et al., Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 2008. 40(1): p. 181-188.

- Tudor-Locke, C., et al., Accelerometer profiles of physical activity and inactivity in normal weight, overweight, and obese US men and women. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2010. 7.

- Stevens, W.R., A.M. Anderson, and K. Tulchin-Francis, Validation of Accelerometry Data to Identify Movement Patterns During Agility Testing. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 2020. 2.

- Khakurel, J., et al., A Comprehensive Framework of Usability Issues Related to the Wearable Devices, in Convergence of ICT and Smart Devices for Emerging Applications, S. Paiva and S. Paul, Editors. 2020, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 21-66.

- Bade, B.C., et al., Assessing the Correlation Between Physical Activity and Quality of Life in Advanced Lung Cancer. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 2018. 17(1): p. 73-79.

- Chan, C., et al., Wearable Activity Monitors in Home Based Exercise Therapy for Patients with Intermittent Claudication: A Systematic Review. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, 2021. 61(4): p. 676-687.

- Ormel, H.L., et al., Self-monitoring physical activity with a smartphone application in cancer patients: a randomized feasibility study (SMART-trial). Supportive Care in Cancer, 2018. 26(11): p. 3915-3923.

- Ferriolli, E., et al., Physical Activity Monitoring: A Responsive and Meaningful Patient-Centered Outcome for Surgery, Chemotherapy, or Radiotherapy? Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 2012. 43(6): p. 1025-1035.

- Ella, K., R. Csepányi-Kömi, and K. Káldi, Circadian regulation of human peripheral neutrophils. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 2016. 57: p. 209-221.

- Hallek, M., et al., iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood, 2018. 131(25): p. 2745-2760.

- Pritchard, A., et al., ARTP statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing 2021. Bmj Open Respiratory Research, 2021. 8(1).

- Radtke, T., et al., Standardisation of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic lung diseases: summary of key findings from the ERS task force. European Respiratory Journal, 2019. 54(6).

- Harkonen, R., R. Harju, and H. Alaranta, Accuracy of the Jamar dynamometer. J Hand Ther, 1993. 6(4): p. 259-62.

- Research, N.I.f.H., Procedure for Measuring Hand Grip Strength Using The JAMAR Dynamometer. 2014, NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre: Southampton. p. 6.

- Kannus, P., Isokinetic evaluation of muscular performance: implications for muscle testing and rehabilitation. Int J Sports Med, 1994. 15 Suppl 1: p. S11-8.

- Broderick, J.M., et al., A guide to assessing physical activity using accelerometry in cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 2014. 22(4): p. 1121-1130.

- Binet, J.L., et al., A New Prognostic Classification of Chronic Lymphocytic-Leukemia Derived from a Multivariate Survival Analysis. Cancer, 1981. 48(1): p. 198-206.

- Rai, K.R., et al., Clinical Staging of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood, 1975. 46(2): p. 219-234.

- Sorensen, J.B., et al., Performance status assessment in cancer patients. An inter-observer variability study. Br J Cancer, 1993. 67(4): p. 773-5.

- Webster, K., D. Cella, and K. Yost, The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2003. 1: p. 79.

- Oerlemans, S., et al., International validation of the EORTC QLQ-CLL17 questionnaire for assessment of health-related quality of life for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol, 2022. 197(4): p. 431-441.

- Institute, J.B., Checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies. 2020, Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia.

- Kang, H., Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 2021. 18.

- Cohen, J., Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd Edition ed. 1988, New York: Routledge.

- Yamada, P.M., C. Teranishi-Hashimoto, and E.O. Bantum, Paired exercise has superior effects on psychosocial health compared to individual exercise in female cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 2021. 29(11): p. 6305-6314.

- Segal, R.J., et al., Randomized Controlled Trial of Resistance or Aerobic Exercise in Men Receiving Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2009. 27(3): p. 344-351.

- Milne, H.M., et al., Effects of a combined aerobic and resistance exercise program in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 2008. 108(2): p. 279-288.

- ACSM, ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Tenth ed. 2018, Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Kim, J.S., et al., Exercise-induced myokines and their effect on prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol, 2021. 18(9): p. 519-542.

- Stamatakis, E., et al., Does Strength-Promoting Exercise Confer Unique Health Benefits? A Pooled Analysis of Data on 11 Population Cohorts With All-Cause, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Mortality Endpoints. Am J Epidemiol, 2018. 187(5): p. 1102-1112.

- Imboden, M.T., et al., Reference standards for lean mass measures using GE dual energy x-ray absorptiometry in Caucasian adults. Plos One, 2017. 12(4).

- Holzner, B., et al., Quality of life of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of a longitudinal investigation over 1 yr. European Journal of Haematology, 2004. 72(6): p. 381-389.

- Youron, P., et al., Quality of life in patients of chronic lymphocytic leukemia using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CLL17 questionnaire. European Journal of Haematology, 2020. 105(6): p. 755-762.

- Artese, A.L., et al., Effects of high-intensity interval training on health-related quality of life in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A pilot study. J Geriatr Oncol, 2022.

- Stein, M.J., et al., Diurnal timing of physical activity and risk of colorectal cancer in the UK Biobank. Bmc Medicine, 2024. 22(1).

- Albalak, G., et al., Setting your clock: associations between timing of objective physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk in the general population. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 2023. 30(3): p. 232-240.

- Okely, A.D., et al., 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. Sports Medicine and Health Science, 2021. 3(2): p. 115-118.

- Persoon, S., et al., Randomized controlled trial on the effects of a supervised high intensity exercise program in patients with a hematologic malignancy treated with autologous stem cell transplantation: Results from the EXIST study. Plos One, 2017. 12(7).

- Portugal, A.M.S. VALORES LABORATORIAIS DE REFERÊNCIA (ADULTOS). 2018 [cited 2025 5 of March]; Available from: https://www.acss.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Tabela_Final.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).