1. Introduction

Regular physical activity is essential for maintaining overall health, reducing the risk of chronic diseases, and enhancing physical and mental well-being across all age groups.The contribution of low physical activity to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and all-cause mortality,measured in DALYs, has increased by 83.9% and 82.9%, respectively, since 1990s [

1,

2,

3].The guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) strongly recommend (i.e., Class I, Level A) that adult of all ages should strive for at least 150-300min a week of moderate-intensity or 75-150 min a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination thereof [

1], which are in line with the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [

2].

While the health benefits of aerobic physical activity are well-documented, the impact of resistance training on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk remains less well understood and appreciated. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends engaging in resistance exercises at least twice per week, targeting all major muscle groups with 8–10 different exercises. Each exercise should comprise 1–3 sets of 8–12 repetitions, performed at an intensity of 60–80% of the individual’s one-repetition maximum. This regimen has been shown to significantly reduce blood pressure but has not been conclusively linked to a reduction in ASCVD risk [

2].Evidence from basic and clinical research indicates that resistance training improves muscular fitness, endothelial function, triglyceride metabolism, and insulin sensitivity [

4,

5,

6]. However, data on its effects on other cardiovascular risk factors and ASCVD risk remain limited. As our understanding of various physical activity modalities evolves, it is plausible that their effects on the cardiovascular system could complement one another, potentially influencing individualized exercise recommendations. For now, however, the role of regular resistance exercise in ASCVD prevention continues to be an area of active investigation [

6,

7].

To the best of our knowledge there is no study evaluating the long-term impacts of aerobic versus resistance or in combination with aerobic physical activity on cardiovascular riskin people from the general population.Thus, the aim of this study was to assess whether aerobic exercise, as opposed to resistance training or a combination of both, is associated with long-term ASCVD outcomes. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed physical activity trajectory data from the 20-year (2002-2022) follow-up of the ATTICA study [

8,

9]. Specifically, we hypothesized that individuals who engaged in a combination of aerobic and resistance exercises would experience the greatest benefits from maintaining an active lifestyle, particularly in reducing CVD mortality and morbidity.

2. Methods

Information about the objectives, design, sampling procedure, and methodology of the ATTICA study have been presented in previously published papers [

8,

9,

10].

2.1. Study Design

The ATTICA study is a prospective cohort.It has been designed to assess the distributionand long-term trends of various socio-demographic, lifestyle, clinical, biochemical, and psychological factors associated with CVD, as well as the relationships between these factors and CVD incidence.

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted in the Attica region of Greece; the area (with a total population of 3,5 million inhabitants) encompasses 58 municipalities, including the capital city, Athens. This region comprises 78% urban areas, with the remainder classified as rural. In 2001, a total of 4,056 individuals were randomly selected from municipality records and employment listings and invited to participate in the study. The sampling process was stratified according to the sex and age group distribution of the region, as outlined in the 2001 census. Preliminary evaluations for exclusion criteria (detailed below) were conducted at participants' residences or workplaces by the study's physicians and healthcare professionals.

2.3. Sample

Out of the 4,056 who were initially invited, 3,042 individuals (1,514 males, mean age 46(13), 1,518 females, mean age 45(14)), who werefree of CVD, cancer, or chronic inflammatory diseasesand were not living in institutions (i.e., exclusion criteria as described in the baseline paper, [

8]), and voluntarily agreed to participate, consisted the study’s sample (75% participation rate).

2.4. Follow-Up

Three follow-up examinations were conducted at 5 years (2006), 10 years (2012), and 20 years (2022) after the baseline assessment (2001–2002). During each follow-up, the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or other conditions (including fatal events), as well as clinical status, lifestyle factors (e.g., dietary habits, physical activity, and smoking status), and psychological well-being, were evaluated using consistent methodologies [

9,

10];in particular, 2,583 participants were found and agreed to re-examined at the 10-year follow-up in 2012(85% participation), and 2,169 participants were found and agreed to participate at the 20-year follow-up in 2022(71%participation). Among the 873 individuals who were lost to follow-up, 771 could not be reached due to changes in their contact information or errors in their addresses or phone numbers, while 102 declined to participate in the screening. For those who deceased, information was collected from their relatives and the death certificates.Comparing the age-sex distribution of thefollow-up samples with the baseline group, no significant differences were found (p-values >0.80).

2.5. Bioethics

The study adheres to the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the First Cardiology Department of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (#017/01.05.2001) and the Ethics Committee of Harokopio University (#38/29.03.2022) approved the study. All participants were informed about the objectives and procedures, providingtheir consent prior to participation.

2.6. Measurements

2.6.1. Physical Activity Status Assessment

The translated into Greek version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form (IPAQ-SF) was utilized to assess participants' weekly energy expenditure and determine their engagement in aerobic training [

11,

12]. The frequency, duration, and intensity of leisure-time aerobic exercise during a typical week were recorded. Intensity was quantified using Metabolic Equivalent (MET) values, where 1 MET represents the energy expenditure at rest (approximately 3.5 ml of oxygen per kg of body weight per minute [ml/kg/min]). Participants were then classified into three groups: (a) inactive, (b) minimally active, and (c) engaging in health-enhancing physical activity (HEPA), based on the frequency and duration of moderate and vigorous activities, following the IPAQ scoring guidelines [

11]. Furthermore, based on a methodology described in a previous publication of the study by Tambalis et al., participants were classified (only or in combination with aerobic) in resistance exercise (isometric, isotonic or isokinetic); frequency and duration of resistance training was recorded. Thus, 3 groups of physical activity were defined in the study’s sample: (i) minimally or HEPA aerobic only, (ii) resistance only and (iii) combinedaerobic and resistance [

13]. Moreover, using the information retrieved through the follow-up examinations, 4 trajectories of physical activity were defined based on the tracking 2002-2022 of physical activity status. Participants were classified as (a) consistently inactive if reported sedentary or engagement in light physical activity in all three follow-up examinations held in 2006, 2012 and 2022, (b) became inactive from physically active if reported sedentary or engagement in light physical activity in the follow-up examinations held in 2012 or 2022, (c) became active from physically inactive if reported engagement in physical activities in all follow-up examinations held in 2012 or 2022,and (d) consistently active during the entire period 2002-2022 [

14].

2.6.2. Socio-Demographic, Lifestyle, Biochemical and Clinical Characteristics Assessment

Severalother characteristicsof the participants were also recorded at baseline examination, including place of residence, highest educational level achieved, smoking status (current/ever, and pack-years of smoking, i.e., average cigarettes per day per year), dietary habits (measured through a validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire [

15]), clinical assessment regarding resting blood pressure, and anthropometric indices and medical history, as well as blood lipids, triglycerides and inflammatory markers levels.Participants were classified as follows: those with total serum cholesterol levels exceeding 200 mg/dL or on lipid-lowering medication were identified as having hypercholesterolemia; those with blood sugar levels above 125 mg/dL or using antidiabetic medication were classified as having diabetes mellitus; and those with average systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or on antihypertensive medication were categorized as having hypertension. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated based on measured weight and height, with obesity defined as a BMI greater than 29.9 kg/m².

Adherence to a Mediterranean-type diet was evaluated using the MedDietScore (ranges from 0 to 55 points, higher values, the greater the adherence to the traditional dietary pattern) [

16].

2.6.3. Follow-Up Assessment

Development of fatal or non-fatal ischemic heart disease, stroke, any other type of ASCVD, was assessed at all follow-up examinations by the physicians of the study, followingthe International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 version.For the individuals who had multiple cardiovascular events (e.g.,those who might had first stroke or heart failure and then developed coronary heart disease), the first outcome was considered as the endpoint.The consequent event was used for further testing of potential competing risks.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviations, while categorical variables as relative frequencies (percentages). The associations between categorical variables were examined using Pearson’s chi-squared test. To compare the mean values of continuous variables, Analysis of Variance with the F-test was used, or the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed data, with Levene’s test assessing the equality of variances. When variances were unequal, the Welch’s F-test was applied. Adjustments for multiple between-group comparisons were made using the t-test or U-test, with Bonferroni correction to control for p-value inflation. The normality of variables was assessed using P-P plots. The cumulative incidence of ASCVD was calculated as the ratio of new cases to the total number of available cases in each group. The p-values for comparisons between physical activity groups or trajectories were determined using the Z-test for equality of proportions with continuity correction. The direct effect of physical activity trajectories on ASCVD incidence was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards models, with proportionality assumptions tested graphically.Results are presented as Hazard Ratios (HR) and their 95% CIs; all models were adjusted for age, sex, and baseline CVD risk factors. Goodness-of-fit statistics of the estimated models included likelihood ratio (LR) which was evaluated through chi-squared test, and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Higher LR values indicate a better fit, while lower AIC values indicate a better model. Nagelkerke’s R

2, a measure analogous to R

2 in linear regression modelling, which allows values ranging between 0 and 1, and shows at what extent factors included in a model may predict the outcome.Log-rank test was used to compare cumulative incidence between groups. The Sobel-Goodman test was applied to evaluate any potential mediating effect in the relationship between physical activity level and CVD incidence, and to calculate the percent of the effect of physical activity on CVD risk is explained by the indirect effect of physical activity onBMI, lipid and inflammation markers and the clinical CVD risk factors, i.e., hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia [

17]. P-values were based on two-sided hypotheses. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 17 (STATA Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics According to Trajectories of Physical Activity Status

At baseline examination, 39% of males and 33% of females were defined as physically active, as well 31% males and 26% females at 5-year follow-up (in 2005), 26% males and 19% females at 10-year follow-up (in 2012), and 30% males and 32% females at 20-year follow-up (in 2022). Moreover, 47% of the participants were classified as always inactive during the 2002-2022 period, 23% became inactive from physically active, 18% became active and, only 9% of males and 15% of females sustained physical activity levels (p<0.001). In a previous publication of the ATTICA Study baseline participants’ characteristics according to the 20-year trajectories of physical activity status have been presented in detail [

14].

3.2. Participants’ Characteristics According to Physical Activity Groups

In

Table 1, participants’ characteristics according to physical activity groups, i.e., aerobic only, resistance training only and combined are presented. Participants that were engaged in resistance training (along or in combination with aerobic) were younger than the rest, as well as they had lessexposure to smoking habit, better lipid and triglycerides profile; all participants involved in any type, aerobic or resistance exercise and the any level had lower BMI levels as compared to physically inactive. Only participants in aerobic HEPA and combined exercise had lower hs-CRP levels. These associations were considered to mediate potential residual confounding in the survival analyses.

3.3. Assessment of 20-Year Incidenceof Cardiovascular Disease in Relation to Aerobic, Resistance or Combinedexercise

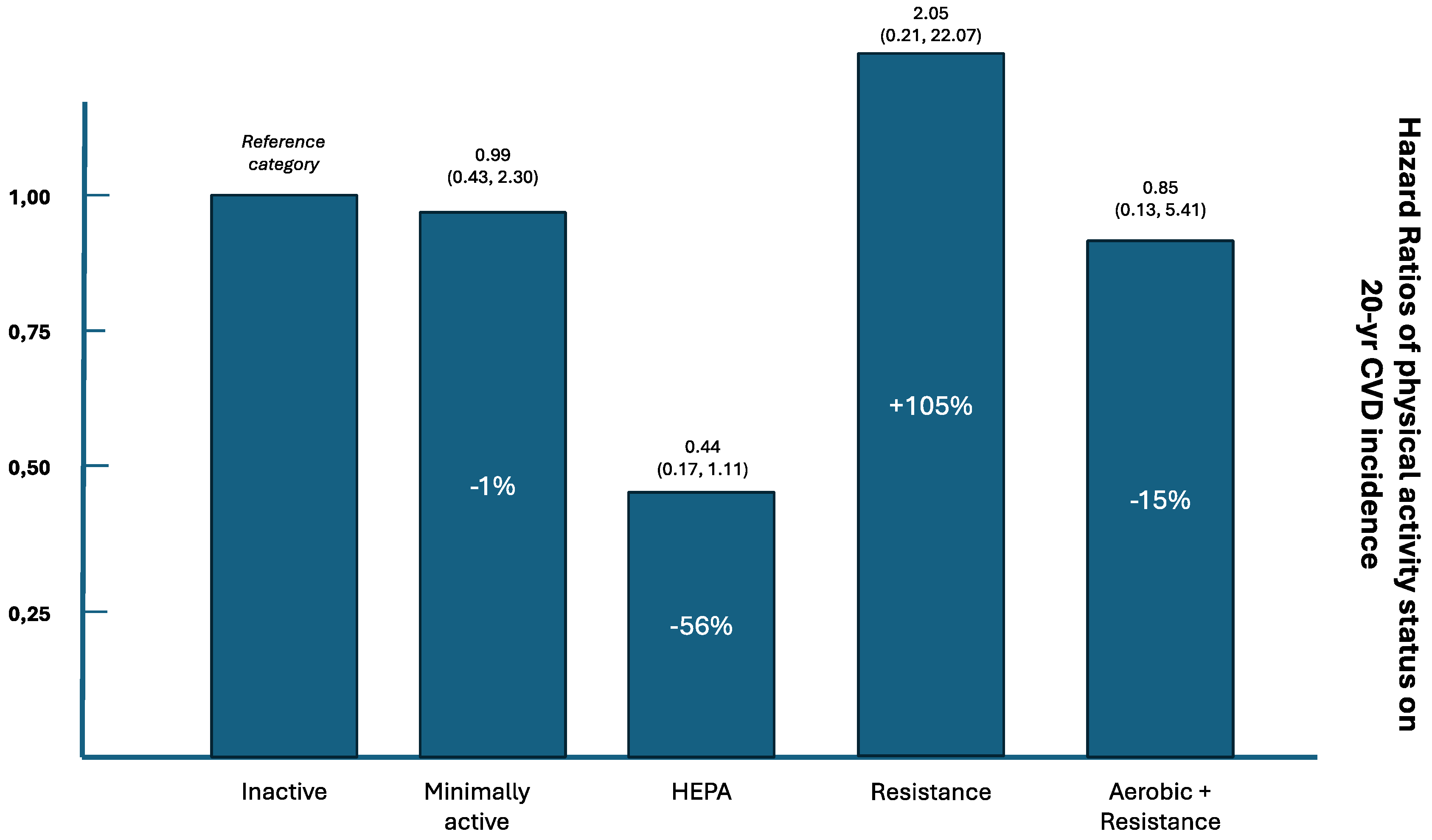

Of those participants who were defined as physically active, consistently or at any time point during the 20-year follow-up, 1271 (42%) were engaged only in aerobic training (minimal or HEPA), 37 (1.2%) only in resistance training and 168 (5.5%) as combined aerobic and resistance training. No significant differences were observed between genders regarding the distribution of types of physical activity (p=0.657). The 20-year cumulative incidence of CVD was 375 cases / 940 participants (39.9%) who were consistently physically inactive, versus 194 cases / 497 participants (39.0%) who were engaged at minimal aerobic exercise group (age, sex adjusted p<0.001), 118 cases / 390 participants (30.3%) who were engaged at HEPA aerobic exercisegroup (p<0.001), 7 cases / 30 participants (23.3%) who were engaged at resistancetraining group (p=0.067), and 24 cases / 131 participants (18.3%) who were engaged at combined aerobic and resistanceexercise group (p<0.001). No gender differences in terms of CVD incidence, could be tested between physical activity groups due to the small number of cases in each group.

Age, sex adjusted survival analysis revealed that participants in the combined, aerobic and resistance exercise group had 0.41-times [95%CI (0.20, 0.82)] lower risk of developing ASCVD during the 20-year of follow-up, as compared to inactive. Moreover, participants in the HEPA aerobic exercise group had 0.54-times [95%CI (0.36, 0.80)] lower risk of developing CVD as compared to inactive. No significant associations were observed regarding minimally activeaerobic group [HR, 0.81, 95%CI(0.57, 1.17)], and resistance training only group [HR, 1.17, 95%CI(0.25, 1.52)], as compared to inactive.

However, residual confounding may still exist as several associations between physical activity groups and several baseline participants characteristics (

Table 1). Thus, nested survival models were estimated; the basic

Model 1was adjusted for age, sex as wellMET-minute/week, to account for the age differences observed between groups, and energy expenditure. It was revealed that the HEPA group and the combined aerobic and resistance training group had lower risk of developing CVD, as compared to physically inactive.Then, in

Model 2social and lifestyle factors were considered, without altering the previous findings suggesting a beneficial association of HEPA,as well as the combined aerobic and resistance training towards CVD risk. However, when intermediate biochemical CVD risk markers were entered in

Model 3, physical activity was not associated with CVD risk. Similarly, allsignificant associationswere lost when medical history and management (i.e., treated or untreated) of hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia were also considered (

Model 4) (

Table 2). In addition, when aerobic HEPA or combined aerobic and resistance physical activity was compared to resistance training the risk for CVD was reduced by 22% [HR 0.78, 95%CI (0.53, 1.01)] and by 29.7% [HR 0.70, 95%CI (0.37, 1.02)], respectively. Hazard ratios and attributable risks are illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.4. Mediation Analysis

The later findings, underline the need for further, mediation analysis to explore by which mechanism HEPA or combined physical activity reduces CVD risk. Sobel-Goodman test revealed that the association between aerobic and or resistance exerciseon CVD risk is mediated by 21.7%through the indirect effect of physical activity on hypertension (p<0.001), by 15.5% through the indirect effect of physical activity on diabetes (p<0.001), by 22.1% through the indirect effect of physical activity on cholesterol levels (p<0.001), and by 5.5% through the indirect effect of physical activity on hs-CRP levels (p=0.023).

4. Discussion

This study investigated whether aerobic exercise, resistance training, or a combination of both is associated with long-term cardiovascular outcomes. It was revealed that aerobic HEPA or combined aerobic and resistance training is associated with a substantial reduction in CVD incidence over the 20-year follow-up, with a superior effect on CVD risk reduction compared to resistance training alone. Despite the limitations carried on due to the observational design of the study, these findings carry a strong public health message, underscoring the importance of incorporating aerobic or combined aerobic-resistance training into physical activity guidelines to enhance cardiovascular health and reduce the long-term risk of CVD.

4.1. Relevant Studies Evaluating Aerobic, Resistance or Combined Exercise in Relation to CVD Outcomes

The effects of aerobic exercise on the cardiovascular system have been extensively studied over the past decades, revealing various pleiotropic benefits, such as regulating arterial blood pressure, lowering lipid and triglyceride levels, reducing inflammatory markers, and improving endothelial function [

2]. However, relatively few studies have demonstrated the benefits of resistance exercise in reducing surrogate risk markers for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), as well as cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the lipid profile in healthy women found that combined exercise training improved triglyceride and total cholesterol levels, contributing to optimal cardiovascular health [

18,

19]. Similarly, a network meta-analysis by Liang et al., showed that combined exercise was most effective in controlling blood glucose and triglyceride levels, while resistance exercise was most efficient in improving LDL cholesterol levels [

20]. Consistent with these findings, Lee et al. reported that aerobic exercise, either alone or combined with resistance training, improved the composite cardiovascular risk profile compared to the control group, which included either resistance exercise alone or no physical activity [

21].Our findings on the associations between various types of physical activity and clinical and biochemical markers showed that the HEPA group and the combined physical activity group exhibited lower levels of HDL-C and hs-CRP compared to the resistance exercise and combined training groups. Additionally, engaging in HEPA or combined aerobic and resistance training was linked to a significant reduction in CVD incidence over a 20-year follow-up period, demonstrating a more pronounced effect on reducing CVD risk than resistance training alone.It was also found that resistance training improves triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL-cholesterol (see

Table 1), but these changes were insufficient to reduce the risk of ASCVD (see

Table 2).

4.2. Recommendations Regarding Physical Activity and CVD

Based on the existing large body of scientific evidence, the latest European Society of Cardiology Guidelines (2021) strongly recommend that “

all adults should be engaged in regular aerobic physical activities to reduce all-cause mortality, as well as ASCVD-specific mortality, and morbidity” [

1], which are in line with the World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour [

22].It is also recommended that people who cannot achieve at least the lowest levels of physical activity, should stay as active as their abilities and health condition allow and try to reduce sedentary time throughout the day [

1]. For older adults or individuals with chronic conditions who cannot achieve 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity a week, they should be as active as their abilities and health conditions allow. Also, the 2019 Joint Guidelines by the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association strongly recommend that all adults should be routinely counseled in healthcare visits to optimize a physically active lifestyle (Class I, Level B) and that decreasing sedentary behavior may be reasonable to reduce ASCVD risk (Class IIb, Level C) [

3]. In line with the previous guidelines, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) also recommends that adults should engage in, at least moderate-intensity aerobic exercise training, and resistance exercises for about 2 to 3 times per week [

23].

4.3. Pathophysiological Mechanisms Regarding Aerobic, Resistance Exercise and CVD

While aerobic exercise is widely recognized as a primary cardioprotective lifestyle intervention for reducing ASCVD risk, some studies suggest that adding resistance exercise to aerobic activity may provide additional benefits for ASCVD risk reduction. However, the independent effects of resistance exercise alone on ASCVD risk remain unclear and underappreciated [

2,

6,

7]. Resistance training primarily improves muscular strength and bone density. Some interventional and experimental studies have shown that resistance exercise, such as weightlifting or bodyweight exercises, increase energy expenditure, improve muscle mass and metabolism, by increasing metabolic rate, which, accordingly, assists in weight management and reduces the risk of obesity [

24]. Resistance exercise has also been associated with better blood pressure regulation [

25]; a finding that was observed in our analyses, too, both at baseline and during the 10-year follow-up examination. Moreover, several clinical trials have shown that engagement in resistance exercise has improved individuals’ lipid profile, by increasing levels of HDL-cholesterol and reducing levels of LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides, which was also evident in the present study, as well. Resistance training has also shown that increases insulin sensitivity, allowing cells to better respond to insulin and regulate blood sugar, as well as decreases levels of inflammatory markers, which are strongly associated with the development and progression of ASCVD [

26].Our study also revealed that participants engaged in resistance or combined exercise training had significantly lower prevalence and 10-year incidence of diabetes. A few studies have also demonstrated that resistance exercise can enhance endothelial function [

27].It is important to note that the significant pressure load placed on the heart during resistance exercise may result in a mild form of cardiac hypertrophy. Additionally, resistance exercise can cause a substantial increase in blood pressure, which may have adverse effects on individuals with uncontrolled hypertension, particularly when performing high-intensity resistance activities [

27]. It should be underlined here that all significant associations between physical activity status and 20-year CVD incidence were lost when medical history and management of hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia were considered in the analyses. This finding suggests that these medical conditions and their management may play a more dominant role in determining long-term CVD risk, potentially attenuating the independent protective effect of physical activity. As discussed earlier, physical activity influences CVD risk partly by reducing hypertension, improving glycemic control, and lowering cholesterol levels. However, if these factors are already well managed (e.g., through medication or lifestyle interventions), the independent contribution of physical activity to CVD risk reduction may be diminished. Specifically, the association between physical activity and reduced CVD risk might be partly explained by its effect on these conditions. Adjusting for their management isolates their impact, revealing that the observed benefits of physical activity could largely be mediated through improvements in these risk factors.

4.4. Limitations

The present study has several strengths but also notable limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. The observational design of the study carries on residual confounding that may persist despite the adjustments for known factors made, as unmeasured variables or imperfectly measured covariates could still affect the observed associations.One other limitation is the reliance on self-reported physical activity data collected through the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. While widely used, this method is subject to recall bias, as participants may inaccurately remember or overestimate their activity levels. Additionally, self-reports are prone to social desirability bias, where individuals might exaggerate their physical activity to align with perceived societal norms or expectations. These inaccuracies can lead to misclassification of activity levels, potentially affecting the validity of the findings and weakening the observed associations between physical activity and CVD incidence.However, it should be noted that this tool has been shown to be reliable, repeatable, and widely used in epidemiological research. Another limitation of the study is the lack of precise, objective measurements to assess strength during resistance exercises. The reliance on indirect or self-reported data for such activities can lead to inaccuracies, as it does not capture the intensity, frequency, or progression of resistance training. Objective methods, such as one-repetition maximum testing or standardized strength assessments, would have provided more reliable and detailed information about participants' muscular strength and effort during resistance exercises. This absence of precise evaluation limits the ability to fully understand the relationship between resistance training and cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence or other health outcomes.Finally, although the loss to follow-up rate was within acceptable levels for observational studies, it may have introduced some bias into the data analysis.

5. Conclusions

By highlighting the greater efficacy of aerobic and combined training in CVD prevention, this study supports a strategic approach to exercise interventions, which can play a pivotal role in public health efforts aimed at reducing the burden of CVD across diverse populations.

Author Contributions

N.D., D.P., K.D.T., Conceptualization and writing the manuscript; C.C., F.B., clinical investigation; D.P., G.A., C.T., critical review of the manuscript, D.P., C.C., C.P., C.T., E.L., P.P.S, methodology; D.P., K.D.T., supervision and primary responsibility for final content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The ATTICA Study has received funding from the Hellenic Cardiology Society (2002), and the Hellenic Atherosclerosis Society (2007).

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ATTICA study group of investigators: Evangelia Damigou, ElpinikiVlachopoulou, Christina Vafia, Dimitris Dalmyras, Konstantina Kyrili, Petros Spyridonas Adamidis, Georgia Anastasiou, Amalia Despoina Koutsogianni, Asimina Loukina, Giorgos Metzantonakis,EvrydikiKravvariti, EvangelinosMichelis, Manolis Kambaxis, Kyriakos Dimitriadis, Ioannis Andrikou, Amalia Sofianidi, Natalia Sinou, Aikaterini Skandali, Christina Sousouni, for their assistance on the 20-year follow-up, as well as Ekavi N. Georgousopoulou, Natassa Katinioti, Labros Papadimitriou, Konstantina Masoura, Spiros Vellas, Yannis Lentzas, Manolis Kambaxis, Konstantina Palliou, Vassiliki Metaxa, AgathiNtzouvani, Dimitris Mpougatsas, Nikolaos Skourlis, Christina Papanikolaou, Georgia-Maria Kouli, Aimilia Christou, Adella Zana, Maria Ntertimani, Aikaterini Kalogeropoulou, Evangelia Pitaraki, Alexandros Laskaris, Mihail Hatzigeorgiou and Athanasios Grekas, Efi Tsetsekou, Carmen Vassiliadou, George Dedoussis, Marina Toutouza-Giotsa, Konstantina Tselika and Sia Poulopoulou and Maria Toutouza for their assistance in the initial and follow-up evaluations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- VisserenFLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, Benetos A, Biffi A, Boavida JM, Capodanno D, Cosyns B, Crawford C, Davos CH, Desormais I, Di Angelantonio E, Franco OH, Halvorsen S, Hobbs FDR, Hollander M, Jankowska EA, Michal M, Sacco S, Sattar N, Tokgozoglu L, Tonstad S, TsioufisKP, van Dis I, van Gelder IC, Wanner C, Williams B; ESC National Cardiac Societies; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 7;42(34):3227-3337. [CrossRef]

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, Michos ED, Miedema MD, Muñoz D, Smith SC Jr, Virani SS, Williams KA Sr, Yeboah J, Ziaeian B. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart AssociationTask Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(10):1376-1414.

- Ammar A, Trabelsi K, Hermassi S, Kolahi AA, Mansournia MA, Jahrami H, Boukhris O, Boujelbane MA, Glenn JM, Clark CCT, Nejadghaderi A, Puce L, Safiri S, Chtourou H, Schöllhorn WI, Zmijewski P, Bragazzi NL. Global disease burden attributed to low physical activity in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: Insights from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. Biol Sport. 2023;40(3):835-855. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Kim Y, Kuk JL. What Is the Role of Resistance Exercise in Improving the Cardiometabolic Health of Adolescents with Obesity? J ObesMetabSyndr. 2019;28(2):76-91. [CrossRef]

- Smith LE, Van Guilder GP, Dalleck LC, Harris NK. The effects of high-intensity functional training on cardiometabolic risk factors and exercise enjoyment in men and women with metabolic syndrome: study protocol for a randomized, 12-week, dose-response trial. Trials. 2022;23(1):182. [CrossRef]

- Rao P, Belanger MJ, Robbins JM. Exercise, Physical Activity, and Cardiometabolic Health: Insights into the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiometabolic Diseases. Cardiol Rev. 2022;30(4):167-178. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis N, Panagiotakos D. Aerobic or Resistance Exercise for maximum Cardiovascular Disease Protection? An Appraisal of the Current Level of Evidence. J Prev Med Hyg. 2024(in press). [CrossRef]

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, Stefanadis C. Epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors in Greece: aims, design and baseline characteristics of the ATTICA study. BMC Public Health, 2003;3:32. [CrossRef]

- PanagiotakosDB, Georgousopoulou EN, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Metaxa V, Georgiopoulos GA, Kalogeropoulou K, Tousoulis D, Stefanadis C. Ten-year (2002-2012) cardiovascular disease incidence and all-cause mortality, in urban Greek population: the ATTICA Study. Int J Cardiol. 2015;180:178-184. [CrossRef]

- Damigou E, Kouvari M, Chrysohoou C, Barkas F, Kravvariti E, Pitsavos C, Skoumas J, Michelis E, Liberopoulos E, Tsioufis C, Sfikakis PP, Panagiotakos DB; ATTICA Study Group. Lifestyle Trajectories Are Associated with Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease: Highlights from the ATTICA Epidemiological Cohort Study (2002-2022). Life (Basel). 2023;13(5):1142. [CrossRef]

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95. [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou G, Georgoudis G, Papandreou M, Spyropoulos P, Georgakopoulos D, Kalfakakou V, Evangelou A. Reliability measures of the short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in Greek young adults. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2009;50(4):283-94.

- Tambalis K, Panagiotakos D, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Skoumas J, Kavouras S, Sidossis L, Stefanadis C. The influence of aerobic and combined with resistance exercise on lipid-lipoprotein profile; evidence from the epidemiological ATTICA study. Arch Hellenic Med 2009; 26(2):230-239.

- Dimitriadis N, Tsiampalis T, Arnaoutis G, Tambalis KD, Damigou E, Chrysohoou C, Barkas F, Tsioufis C, Pitsavos C, Liberopoulos E, Sfikakis PP, Panagiotakos D. Longitudinal trends in physical activity levels and lifetime cardiovascular disease risk: insights from the ATTICA cohort study (2002-2022). J Prev Med Hyg. 2024;65(2):E134-E144. [CrossRef]

- Katsouyanni K, Rimm EB, Gnardellis C, Trichopoulos D, Polychronopoulos E, Trichopoulou A. Reproducibility and relative validity of an extensive semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire using dietary records and biochemical markers among Greek schoolteachers. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;Suppl 1: S118-127. [CrossRef]

- Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Dietary patterns: a Mediterranean diet score and its relation to clinical and biological markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;16(8): 559-568. [CrossRef]

- Mize, Trenton D. "sgmediation2: Sobel-Goodman tests of mediation in Stata." Accessed through https://www.trentonmize.com/software/sgmediation2, at November 14, 2024.

- Paluch AE, Boyer WR, Franklin BA, Laddu D, Lobelo F, Lee DC, McDermott MM, Swift DL, Webel AR, Lane A; on behalf the American Heart Association Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Resistance Exercise Training in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease: 2023 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(3):e217-e231. [CrossRef]

- Pourmontaseri H, Farjam M, Dehghan A, Karimi A, Akbari M, Shahabi S, Nowrouzi-Sohrabi P, Estakhr M, Tabrizi R, Ahmadizar F. The effects of aerobic and resistant exercises on the lipid profile in healthy women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J PhysiolBiochem. 2024 Jun 12. [CrossRef]

- Liang M, Pan Y, Zhong T, Zeng Y, Cheng ASK. Effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise on metabolic syndrome parameters and cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. RevCardiovascMed. 2021 Dec 22;22(4):1523-1533. [CrossRef]

- Lee DC, Brellenthin AG, Lanningham-Foster LM, Kohut ML, Li Y. Aerobic, resistance, or combined exercise training and cardiovascular risk profile in overweight or obese adults: the CardioRACE trial. EurHeart J. 2024 Apr 1;45(13):1127-1142. [CrossRef]

- Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, Carty C, Chaput JP, Chastin S, Chou R, Dempsey PC, DiPietro L, Ekelund U, Firth J, Friedenreich CM, Garcia L, Gichu M, Jago R, Katzmarzyk PT, Lambert E, Leitzmann M, Milton K, Ortega FB, Ranasinghe C, Stamatakis E, Tiedemann A, Troiano RP, van der Ploeg HP, Wari V, WillumsenJF. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J SportsMed. 2020 Dec;54(24):1451-1462. [CrossRef]

- Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, Nieman DC, Swain DP; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. MedSciSportsExerc. 2011;43(7):1334-59. [CrossRef]

- Westcott WL. Resistance training is medicine: effects of strength training on health. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(4):209-16. [CrossRef]

- Kirkman DL, Lee DC, Carbone S. Resistance exercise for cardiac rehabilitation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;70:66-72. [CrossRef]

- Mcleod JC, Stokes T, Phillips SM. Resistance Exercise Training as a Primary Countermeasure to Age-Related Chronic Disease. Front Physiol. 2019;10:645. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen SL, Kierkegaard-Brøchner S, Bohn MB, Høgsholt M, Aagaard P, Mechlenburg I. Effects of blood-flow restricted exercise versus conventional resistance training in musculoskeletal disorders-a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2023;15(1):141. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).