1. Introduction

Single image dehazing plays an important role in fields such as autonomous driving, intelligent surveillance, and remote sensing, serving as a crucial link between low-level image restoration and high-level visual understanding. Over the past decade, researchers have explored a wide range of approaches. Prior-based physical models [

1,

2,

3] estimate the parameters of the atmospheric scattering model based on statistical assumptions. While these methods can enhance image quality to some degree, their strong dependence on simplified assumptions often limits their ability to handle complex and diverse real-world environments. With the rise of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

4] and Transformers [

5], data-driven methods [

6,

7,

8] have gradually become the dominant trend. By learning degradation patterns directly from large-scale datasets, these methods have achieved remarkable progress and consistently outperform traditional techniques. However, since most deep learning models are trained on synthetic datasets, their performance often drops significantly when applied to real-world hazy images due to the domain gap, resulting in limited generalization ability. In summary, the lack of high-quality and robust semantic priors remains one of the key challenges preventing existing dehazing methods from achieving stronger generalization in real-world scenarios.

In recent years, the advancement of deep learning and large-scale pre-trained models has provided new directions for image dehazing. In particular, prior-based methods incorporating pre-trained models have emerged as a research hotspot. Meta AI introduced the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [

9] in 2023, which achieves strong cross-domain generalization capability through large-scale pretraining and a prompt-driven segmentation paradigm. Subsequent works have extended this line with lightweight versions such as Mobile SAM [

10] and multimodal variants to broaden its applicability. The most recent SAM2 achieves breakthroughs in both architecture and training scale, significantly improving segmentation accuracy and robustness. Notably, SAM2 [

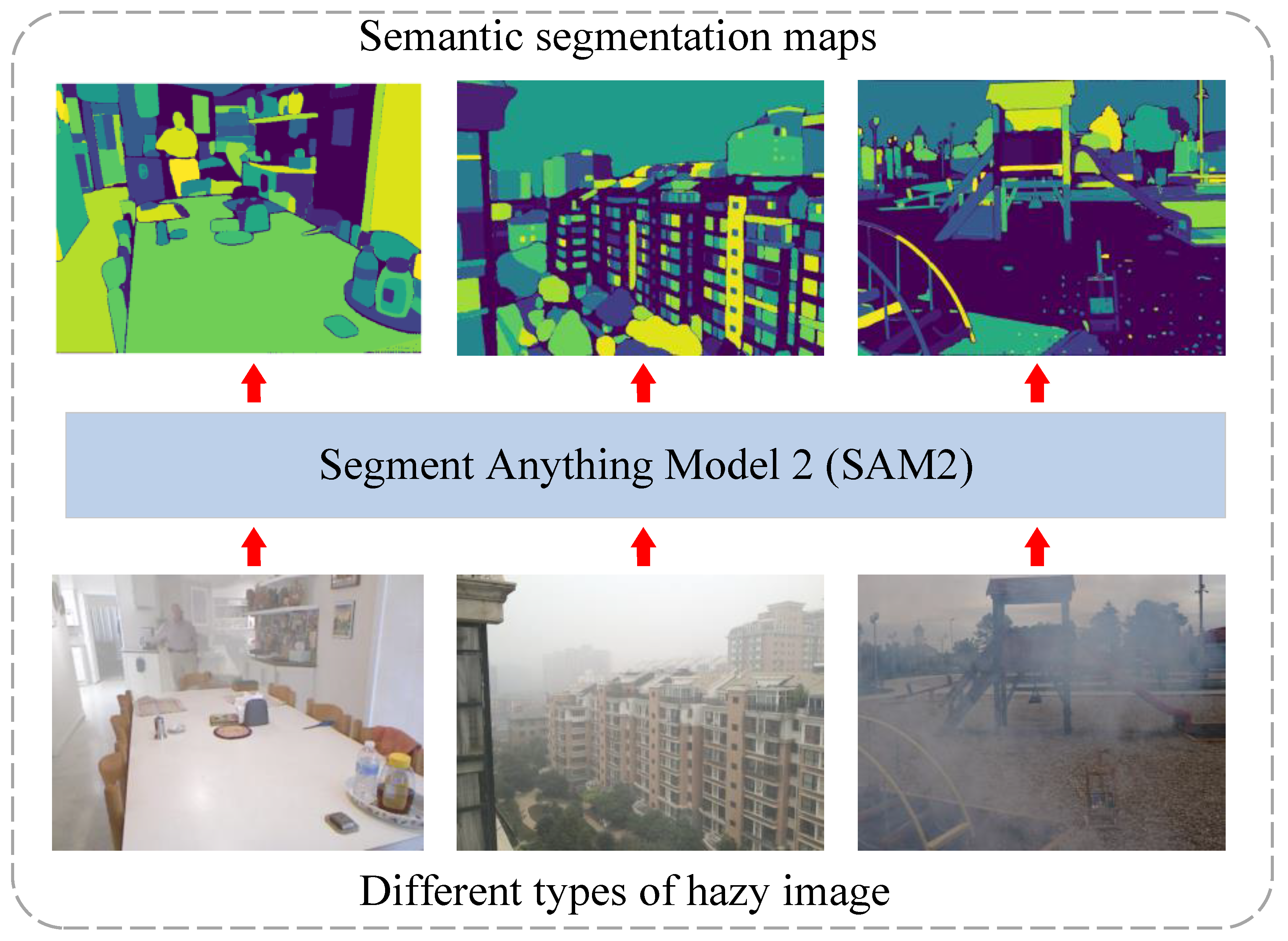

11] maintains superior performance even under degraded conditions such as hazy images (see

Figure 1), providing a reliable semantic prior for dehazing tasks.

To overcome the common problems of existing dehazing methods, such as limited semantic priors and poor detail recovery, we propose a new dehazing network called SAM2-Dehaze.

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

We design a Semantic Prior Fusion Block (SPFB), which introduces SAM2-derived semantic information at multiple stages of the U-Net backbone. This semantic fusion mechanism guides the model to highlight structural features in key regions, enhancing its perception and restoration of edges and textures.

We design a Parallel Detail-enhanced and Compression Convolution (PDCC), which combines standard, difference, and reconstruction convolutions to enable collaborative multi-level feature modeling. This module improves high-frequency detail representation while reducing redundancy.

We design a Semantic Alignment Block (SAB) in the reconstruction phase, which performs fine-grained semantic alignment to restore colors, textures, and boundaries of key regions, thereby ensuring semantic consistency, visual naturalness, and structural integrity of the dehazed results.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Image Dehazing

In the early stages of image dehazing research, prior-based methods emerged as the mainstream approach and were widely applied. These methods typically rely on the Atmospheric Scattering Model (ASM) and employ handcrafted empirical priors to model the statistical differences between hazy and haze-free images. By doing so, they estimate the transmission map and atmospheric light parameters to recover the clear scene. For example, He et al. [

12] proposed the Dark Channel Prior (DCP), which is based on the observation that in most local patches of outdoor haze-free images, at least a color channel exhibits very low intensity. This prior effectively aids in estimating the transmission map and has achieved impressive performance in dehazing tasks. Zhu et al. [

13] introduced the Color Attenuation Prior, which analyzes the differences in brightness and saturation to establish a linear relationship with scene depth, enabling the inference of the transmission map. Berman et al. [

14] proposed the Non-local Prior, which is based on the observation that pixels in the RGB color space tend to exhibit non-local clustering behavior. This structural property helps distinguish haze from the underlying scene content and provides effective guidance for image dehazing without the need for explicit depth information.

Although prior-based methods have achieved significant progress in early image dehazing tasks and demonstrated good performance in certain scenarios (e.g., ground or building regions), their effectiveness is often limited by the applicability of the underlying prior assumptions. When dealing with complex and non-uniform haze distributions in natural scenes, handcrafted priors often fail to accurately capture the intricate relationships between haze and image content. This limitation frequently leads to artifacts such as color distortion and halo effects, ultimately degrading the overall dehazing quality.

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Image Dehazing

With the rapid development of deep learning and the availability of large-scale synthetic dehazing datasets, learning-based image dehazing has rapidly become the mainstream research direction. Early methods mainly followed physics-guided learning frameworks, relying on the Atmospheric Scattering Model (ASM) to estimate intermediate parameters such as transmission maps and atmospheric light for haze-free reconstruction. For instance, Shi et al. [

15] proposed a zero-shot sand–dust image restoration method based on the atmospheric scattering model, enabling unsupervised recovery of real sand–dust images without paired data and achieving superior visual quality. Ren et al. [

16] proposed MSCNN to progressively refine transmission estimation, Li et al. [

17] introduced AOD-Net to jointly predict transmission and atmospheric light in an end-to-end manner, and Zhang et al. [

18] designed DCPDN with dual branches to improve estimation accuracy. Li et al. [

19] further enhanced performance under complex conditions by combining fuzzy region segmentation and haze density decomposition.

Despite their effectiveness, physics-guided methods suffer from error accumulation in intermediate estimations, leading to degraded restoration quality. Recent studies have thus shifted toward purely data-driven approaches. For example, Liu et al. [

20] developed GridDehazeNet based on attention mechanisms, Qin et al. [

7] proposed FFA-Net with feature-level adaptive attention, and Wu et al. [

21] introduced AECR-Net with contrastive regularization. Hong et al. [

22] modeled prediction uncertainty via UDN, Cheng et al. [

23] presented DEA-Net for enhanced detail and structure preservation, and Wang et al. [

24] combined Retinex theory with self-supervised learning in Dehaze-RetinexGAN. Son et al. [

25] proposed a Retinex-based reinforced multiscale image pair training method for sand–dust removal, achieving superior color fidelity and clarity under severe atmospheric conditions.

Although these methods significantly improve image clarity and visual quality, they still tend to neglect structural information. Most focus on global color or brightness enhancement, often producing blurred edges or semantic inconsistencies, which limits their applicability in high-quality restoration tasks.

2.3. Semantic Priors for Image Dehazing

In recent years, several studies have incorporated semantic information to guide the dehazing process, aiming to enhance the modeling of image structure and content. For example, Zhang et al. [

26] utilized a pre-trained DeepLabv3+ network to extract semantic features and integrated them into the dehazing network through an adaptive fusion module, thereby improving semantic awareness and regional discrimination. Cheng et al. [

27] adopted the VGG16 network to extract semantic features and employed a global estimation module together with a color recovery module to transform semantic information into priors of object color and atmospheric light. Song et al. [

28] proposed a segmentation-guided dehazing framework that divides the task into two stages: semantic prediction and segmentation-guided restoration, significantly improving the reconstruction of edge structures and fine textures. Although these methods have achieved remarkable success in introducing structural priors and enhancing scene understanding, they generally rely on task-specific semantic segmentation models (e.g., DeepLabv3+ and VGG16) and require pre-training or fine-tuning on specific datasets, which to some extent limits their generalization ability.

With the introduction of the Segment Anything Model (SAM), the approach to semantic segmentation has shifted from task-specific to task-agnostic. As a large-scale pre-trained universal segmentation model, SAM shows strong structural perception and cross-domain generalization capabilities. It can produce high-quality masks without requiring extra supervision or task-specific training, which greatly expands the use of semantic priors in low-level vision tasks. For example, Zhang et al. [

29] proposed an image restoration framework that uses semantic priors extracted from SAM to improve the model’s ability to capture both structural and semantic information, all without increasing inference costs. Li et al. [

30] introduced the SAM-Deblur framework, the first to apply SAM to image deblurring. By using plug-and-play Mask Average Pooling (MAP) modules and a mask dropout strategy, they effectively added structural priors and improved generalization under non-uniform blur. Liu et al. [

31] proposed SeBIR, a general framework for burst image restoration guided by SAM’s semantic priors. It uses a joint explicit-implicit alignment strategy and a semantic-guided fusion module, leading to significant improvements in alignment accuracy and multi-frame information integration.

Although these methods demonstrate SAM’s great potential in image restoration, most still rely on simple semantic feature concatenation or shallow feature-guided strategies, which fail to fully utilize the power of SAM’s semantic priors in deep feature fusion. This limitation becomes especially noticeable in complex scenarios involving structural misalignment or regional degradation. In contrast, we propose a structure-aware enhanced image dehazing method that fully takes advantage of the semantic priors provided by SAM2. By designing three key modules, our approach integrates semantic guidance at every stage of the pipeline, from feature extraction to final reconstruction, leading to better semantic consistency, detail recovery, and structural preservation.

3. Proposed Model

3.1. Overview of SAM2-Dehaze Model

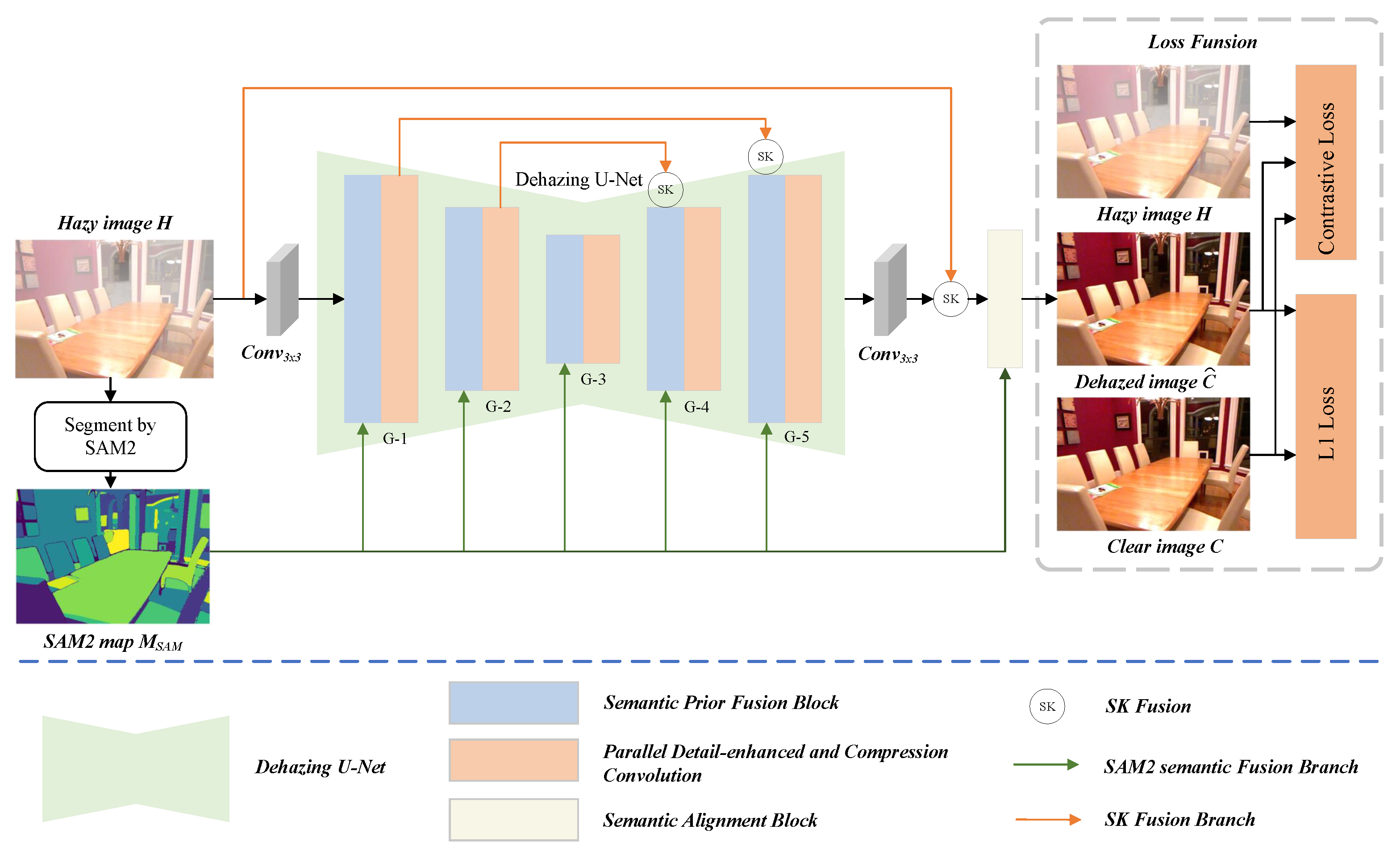

We propose a SAM2-guided image restoration method based on semantic information. The overall architecture of the proposed model is illustrated in

Figure 2. We first utilize a pre-trained SAM2 to generate semantic prior information, which is then effectively injected into the dehazing network via the SPFB, enhancing the network’s perception of semantic regions. However, considering that standard convolution has limited capability in capturing features around object boundaries and fine details, we introduce the PDCC to strengthen feature representation across different semantic regions, compensating for the deficiencies of conventional convolution in edge perception. In addition, to further improve the semantic consistency and structural fidelity of the dehazing results, we design a SAB. By modeling high-level relationships between the initially restored image and the semantic priors, SAB performs structural-level semantic alignment, enabling the final restored image to not only appear more realistic, but also exhibit clearer edges, richer details, and higher semantic coherence.

3.2. Semantic Prior Fusion Block

Due to its training on massive datasets and rich parameterization, SAM2 exhibits excellent segmentation capabilities across diverse scenarios and demonstrates strong robustness against various types of image degradation. In image restoration tasks, directly using degraded images as input may hinder the model’s ability to distinguish the true structure of target regions. Therefore, we leverage the semantic segmentation maps extracted from SAM2 as prior information to provide diverse and informative guidance for existing image dehazing tasks, thereby enhancing restoration performance.

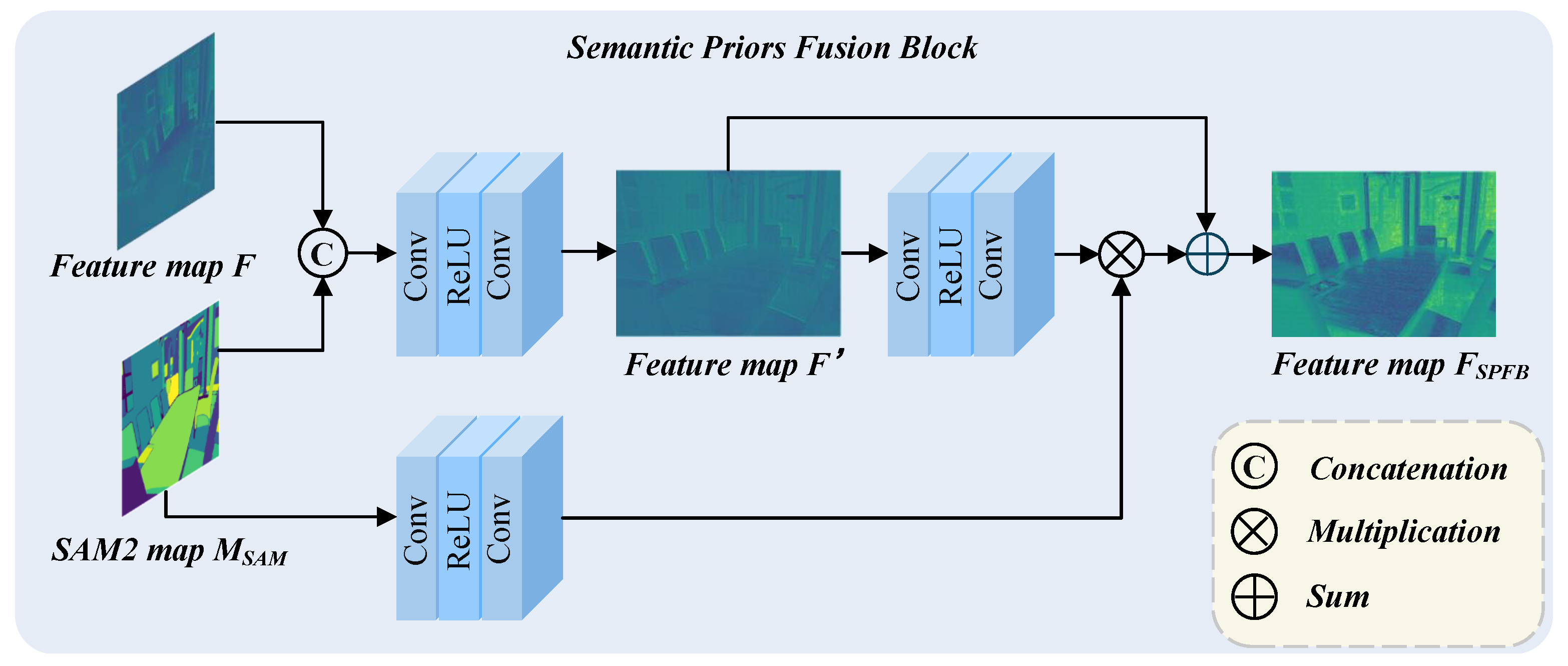

First, we utilize the semantic map

extracted by SAM2 as an explicit prior and fuse it with the feature map

F of the low-quality image to enhance the feature representation capability of the restoration model. Specifically, as shown in

Figure 3, the image feature

F and the semantic prior

are concatenated along the channel dimension and fed into a convolutional function

, which consists of two convolution layers and a ReLU activation function, to obtain the initial fused feature

.

where,

denotes the concatenation operation along the channel dimension. Next, we design a feature interaction mechanism to further enhance the role of semantic information during the restoration process. Specifically, we adopt two parallel feature extraction branches: one is used to extract the updated image features

, and the other to extract the semantic prior representation from

. Each branch consists of two convolutional layers and a ReLU activation function, and they are computed as follows:

where,

P represents the semantic feature extracted from the SAM segmentation map, and

denotes the image feature after further transformation. To establish explicit interaction between the two, we apply element-wise multiplication at the outputs of the two feature branches and introduce skip connections in the image feature branch. This design adaptively enhances the model’s ability to perceive important semantic regions during the restoration process.

where,⊗ denotes element-wise multiplication and ⊕ denotes element-wise addition.

3.3. Semantic Prior Fusion Block

In image dehazing tasks, the presence of haze often leads to changes in illumination and color, which typically manifest as the loss of low-frequency information. At the same time, natural scenes covered by haze may also lose high-frequency details such as edges and contours. Traditional convolutional operations mainly focus on capturing low-frequency information while neglecting the recovery of high-frequency components, which often becomes a bottleneck in dehazing performance. In addition, standard convolutions tend to introduce spatial redundancy, limiting the efficiency and effectiveness of dehazing networks. To address these issues, we propose a parallel detail-enhanced and compression convolution.

The PDCC module mainly consists of three parallel branches: Detail Enhancement Convolution (DEConv) [

23], Convolution Branch, and Spatial-Channel Construction Convolution (SCConv) [

32], as shown in

Figure 4. We first apply Batch Normalization to the input feature

to obtain the normalized input

. Then, the normalized features are directed into the three branches for separate processing. Specifically, the Conv branch is responsible for basic feature learning, ensuring effective retention of low-frequency information; the DEConv branch contains four types of difference convolutions: Center Difference Convolution (CDC), Angle Difference Convolution (ADC), Horizontal Difference Convolution (HDC), and Vertical Difference Convolution (VDC), used for multi-directional and multi-scale high-frequency detail extraction. Directly deploying these convolutions significantly increases the number of parameters and inference time. To address this issue, the paper [

23] proposes combining these convolution kernels at corresponding positions to obtain an equivalent kernel, thereby maintaining the detail extraction capability while reducing computational complexity. The specific operations are as follows:

where,

represents the kernels of the four convolution operations,

is the input feature map, ∗ denotes the convolution operation, and

is the equivalent kernel obtained by combining the four kernels. On the other hand, SCConv is designed to suppress feature redundancy and enhance feature representation capability. It consists of a Spatial Reconstruction Unit (SRU) and a Channel Reconstruction Unit (CRU), which are sequentially integrated. SRU reduces spatial redundancy using a “separation-and-reconstruction” strategy, while CRU adopts a “split-transform-fuse” scheme to minimize channel redundancy. The specific operations are as follows:

where,

denotes the feature map after spatial reconstruction. Finally, the features obtained from the Conv, DEConv and SCConv branches are summed and further refined through a 5 × 5 convolution layer to produce the final output feature

.

3.4. Semantic Alignment Block

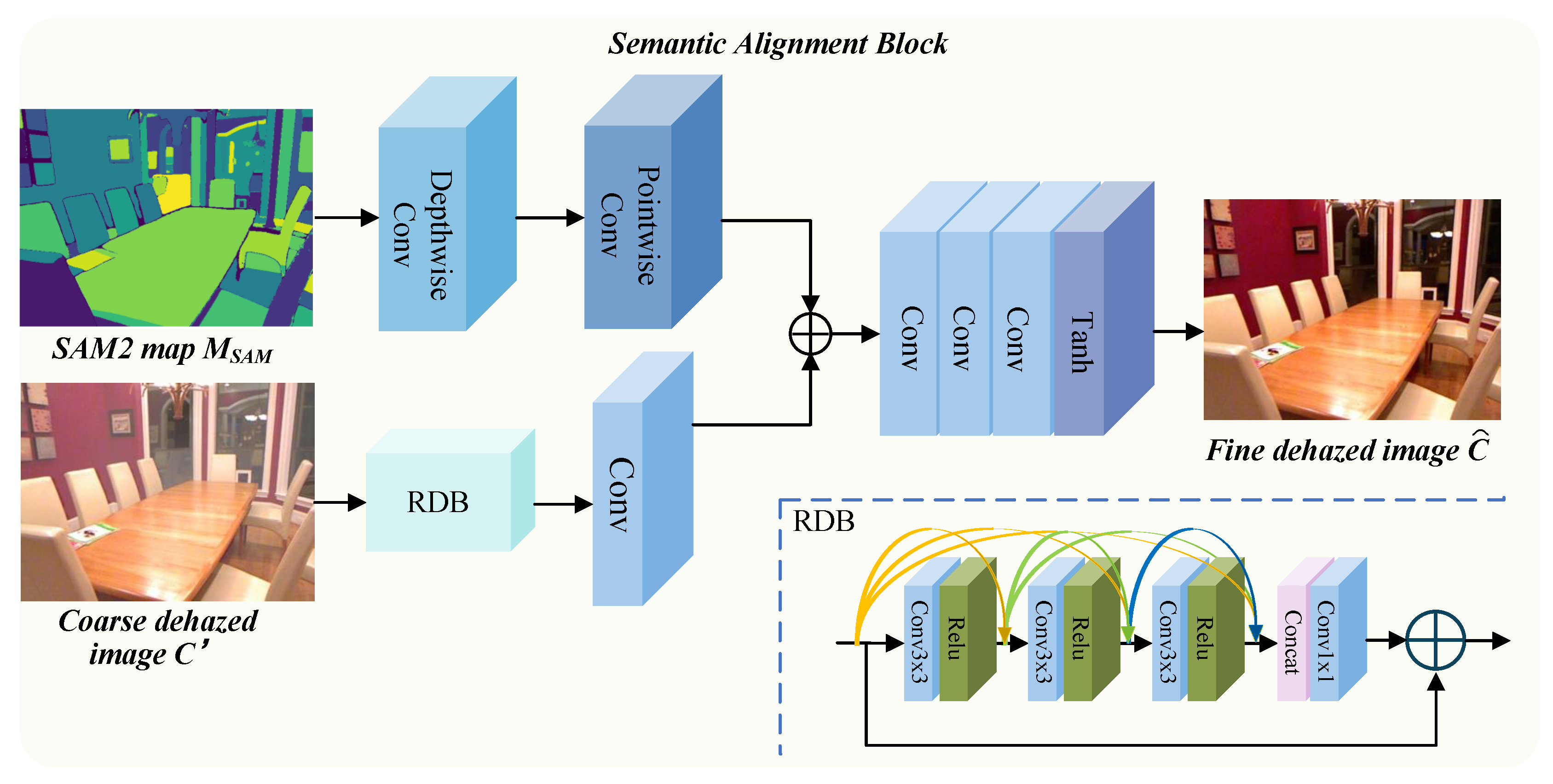

Semantic information provides crucial guidance during the restoration of degraded images, especially for reconstructing color, contrast, and texture consistency. Objects belonging to the same semantic category often share structural and visual similarities. Such intra-class semantic correlations can effectively constrain the solution space of image restoration, helping to preserve both large-scale structures and fine-grained details. To leverage this, we design a SAB in the post-processing phase of the dehazing network, using high-level semantics as structural priors to guide further refinement. SAB extracts key semantic features from the semantic segmentation map generated by SAM and deeply fuses them with the structural features of the coarsely dehazed image. This enhances the model’s ability to recognize semantic regions and restore structural integrity, significantly improving the clarity, naturalness, and semantic consistency of the final output.

Specifically, as shown in

Figure 5, we apply depth-wise separable convolutions to the semantic segmentation map

obtained from SAM2 to extract semantic-guided features. Subsequently, a residual dense block (RDB) [

33] is applied to the coarse-dehazed image

to extract clean image features. RDB is an efficient residual dense module, shown in

Figure 5, which is used in the final phase of image restoration to improve the representation of structures and fine details by using residual learning and dense connections. Next, the semantic-guided features and the coarse-dehazed image features are fused. To further improve the dehazing performance, multiple standard convolutional layers are employed to refine the fused features, and a hyperbolic tangent activation function (Tanh) is used to generate the final refined dehazed image

. With the guidance of high-level semantic information provided by SAM2, our network is capable of restoring clearer and more natural haze-free images.

3.5. Train Loss

During the training process, we adopt the L1 loss and contrastive loss to optimize the quality of the dehazed images. The L1 loss is used to directly constrain the pixel-level difference between the dehazed image and the ground-truth haze-free image, while the contrastive loss enforces the similarity of deep feature representations to improve structural fidelity and perceptual quality. Specifically, given a hazy image H and its corresponding clear image C, we denote the predicted dehazed image from our SAM2-Dehaze as

. The contrastive loss optimization objective can be formulated as:

where,

denotes the features extracted from the

i layer of a fixed pre-trained model, and

represents the corresponding weight coefficient for that layer. In our study, we extract features from layers 11, 35, 143, and 152 in the ResNet-152 [

4], and set the weights

to

and 1, respectively. In fact, previous research [

34] has demonstrated that, in image restoration tasks, compared to the L2 norm, the L1 norm yields better performance. The L1 loss is defined as:

where, N denotes the total number of pixels in the image, and

and

represent the predicted dehazed result and the

j pixel values of the ground truth haze-free image, respectively. By combining the L1 loss and contrastive loss, our final loss function is defined as:

where,

is the hyperparameter used to balance the two loss terms, and it is set to 0.1 in our experiments.

4. Experimentsl

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

Datasets: We conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed method on both synthetic and real-world image datasets. Realistic Single Image Dehazing (RESIDE) [

35] is a widely used benchmark dataset, consisting of the Indoor Training Set (ITS), the Outdoor Training Set (OTS), the Synthetic Objective Testing Set (SOTS), the Real-world Task-driven Testing Set (RTTS), and the Hybrid Subjective Testing Set (HSTS). In the synthetic experiments, we train our model on ITS and OTS, and evaluate it on SOTS-indoor and SOTS-outdoor, respectively. For real-world scenarios, we adopt the Dense-Haze [

36], NH-Haze [

37] and RTTS datasets to assess the performance of our method on real hazy images. Detailed settings are summarized in

Table 1.

Evaluation Metrics: For dehazing performance evaluation, we employ a total of seven widely used image quality assessment metrics, categorized into two types. The full-reference metrics include Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) [

38], and CIEDE2000 color difference [

39]. The no-reference metrics consist of Fog Aware Density Evaluation (FADE) [

40], Natural Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE) [

41], Perception-based Image Quality Evaluator (PIQE) [

42], and Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator (BRISQUE) [

43]. These metrics are widely adopted in the field of computer vision to measure visual quality and perceptual consistency of images. For network performance evaluation, we report the number of model parameters (Param, in millions), computational complexity (MACs, in billions of multiply-accumulate operations), and inference latency (Latency, in milliseconds). To ensure fairness, all experiments are conducted on images with a resolution of 250×250.

4.2. Implementation Details

We use the SAM2 pretrained model for segmentation. Compared with the SAM segmentation model, SAM2 demonstrates significant improvements in segmentation accuracy, speed, interaction efficiency, and applicability across various scenarios. In particular, it shows stronger information processing capabilities and generalization in zero-shot segmentation tasks. All experiments are conducted on an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU (48GB VRAM), and the model is implemented based on the Pytorch 2.4.1 framework. During training, we optimize the network using the AdamW optimizer, with decay parameters set to

and

. The initial learning rate is set to

, and it is gradually decreased to

using a cosine annealing strategy to ensure training stability. During training, input images are randomly cropped into 256 × 256 patches. We design three variants of SAM2-Dehaze, named S (Small), B (Basic), and L (Large).

Table 2 presents detailed configurations of each variant, with two key columns indicating the number of G-blocks in the network and their corresponding embedding dimensions.

4.3. Comparison with State-of-the-Arts

In this section, we compare our SAM2-Dehaze with eleven dehazing methods, including DCP [

12], MSCNN [

16], AOD-Net [

17], GridDehazeNet [

20], FFA-Net [

7], AECR-Net [

21], Dehamer [

44], MIT-Net [

45], RIDCP [

46], C2PNet [

47], and DEA-Net [

23], on the synthetic haze datasets SOTS-indoor and SOTS-outdoor. For real-world datasets, we compare seven methods (DCP, AOD-Net, FFA-Net, Dehamer, MIT-Net, RIDCP, MixDehazeNet [

48]) on the Dense-Haze and NH-Haze datasets. For the RTTS dataset, we compare our method with seven existing approaches, including GridDehazeNet, FFA-Net, Dehamer, C2PNet, MIT-Net, DEA-Net, and IPC-Dehaze [

49]. On the synthetic datasets, we report results for three variants of SAM2-Dehaze (-S, -B, -L), while on the real-world datasets, only the SAM2-Dehaze-L variant is evaluated. To ensure a fair comparison, for other methods, we either use their officially released code or publicly reported evaluation results. If these are not available, we retrain the models using the same training datasets.

Results on Synthetic Datasets:Table 3 presents the quantitative evaluation results of our SAM2-Dehaze and other state-of-the-art methods on the SOTS dataset. As shown, our SAM2-Dehaze-L achieves the best performance on the SOTS-indoor dataset, with a PSNR of 42.83 dB and an SSIM of 0.997, outperforming all other methods. Even the lightweight SAM2-Dehaze-S achieves the second-best performance, apart from ours, with a PSNR of 41.41 dB and an SSIM of 0.996. On the SOTS-outdoor dataset, our method does not achieve the best result but still ranks in the upper-middle tier overall. The best-performing variant, SAM2-Dehaze-L, reaches a PSNR of 36.22 dB and SSIM of 0.989. In addition, as shown

Table 4, we report Params, MACs, and Latency as the main metrics for computational efficiency. Compared to recent advanced methods, our SAM2-Dehaze achieves a balanced trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. Given the performance improvements, the slight increase in computational cost is acceptable. It is worth noting that Params, MACs, and Latency are evaluated based on 256 × 256 RGB input images.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the visual comparison results of our proposed method against several state-of-the-art dehazing methods on the synthetic datasets SOTS-indoor and SOTS-outdoor. To more comprehensively evaluate the performance of each method, we further incorporate the RGB histogram distribution of the images to quantitatively assess color consistency in addition to subjective visual analysis. On the SOTS-indoor dataset, traditional methods such as DCP and RIDCP perform poorly, with noticeable color distortions and residual artifacts in the restored images. AOD-Net also fails to remove most of the haze effectively. Although GridDehazeNet, FFA-Net, Dehamer, and MIT-Net produce visually plausible results, the histogram analysis shows that our method achieves a distribution in the RGB channels that is more consistent with the ground truth clear images, indicating its superiority in both color restoration and detail preservation. For the SOTS-outdoor scenario, DCP often introduces artifacts in sky regions, and although AOD-Net retains some structural information, noticeable haze still remains. It is worth noting that SOTS-outdoor is a synthetic dataset generated using the atmospheric scattering model, and some of the so-called "haze-free" images may still contain traces of real haze, which can introduce noise into model training and evaluation. While methods like GridDehazeNet, FFA-Net, Dehamer, MIT-Net, and RIDCP perform well on synthetic haze, they still exhibit limitations in handling residual real haze embedded in images. In contrast, our proposed method not only effectively removes synthetic haze but also demonstrates greater robustness and adaptability in dealing with residual real haze, achieving superior performance in both visual quality and detail preservation.

Results on Real-World Datasets:Table 5 shows the quantitative evaluation results of our SAM2-Dehaze-L compared with other state-of-the-art methods on the Dense-Haze and NH-Haze datasets. As observed, our method achieves competitive results on both datasets. On the Dense-Haze dataset, our method achieves the best performance with 20.61 dB in PSNR, 0.725 in SSIM, and 8.5909 in CIEDE2000. Compared with the baseline MixDehazeNet-L, our method improves PSNR by 4.71 dB, SSIM by 0.146, and CIEDE2000 by 28.99%. On the NH-Haze dataset, our method also achieves the best results, with a PSNR of 22.02 dB, SSIM of 0.831, and CIEDE2000 of 8.5108. Compared with the baseline, the improvements are 1.01 dB in PSNR, 0.004 in SSIM, and 10.53% in CIEDE2000. It is worth noting that the performance gain on the NH-Haze dataset is relatively smaller. We attribute this to the fact that the Dense-Haze dataset contains a higher concentration of haze and more severe image degradation, which poses greater challenges for traditional methods in feature extraction. In contrast, our method leverages semantic prior information from the SAM2, which significantly enhances the network’s structural perception and semantic representation capabilities under dense haze conditions, thereby leading to more substantial performance improvements.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the qualitative comparison results of our method on the Dense-Haze and NH-Haze real-world haze datasets. It can be observed that traditional methods such as DCP and RIDCP exhibit noticeable color distortions and residual haze on both datasets. Lightweight deep models like AOD-Net show limited dehazing capability. Although FFA-Net and MIT-Net perform better, they struggle with detail preservation, resulting in blurry regions in local areas. Dehamer improves image brightness, but introduces significant artifacts and unnatural regions. MixDehazeNet demonstrates overall improvement, but still fails to fully handle regions with dense haze. In contrast, our proposed method achieves superior dehazing performance on both datasets. It effectively restores realistic color and fine textures while suppressing noise and artifacts, producing results that are noticeably clearer, more natural, and more visually consistent with the ground truth images.

Results on RTTS datasets:Table 6 presents the quantitative comparison between our method and several state-of-the-art dehazing approaches on the RTTS dataset, evaluated using four no-reference image quality metrics: FADE, NIQE, PIQE, and BRISQUE. As shown in the table, although IPC-Dehaze achieves the best overall performance, our method outperforms most existing methods across all metrics.

We conduct a qualitative comparison on the RTTS dataset, as shown in

Figure 10. Overall, FFA-Net, Dehamer, GridDehazeNet, and MIT-Net exhibit limited dehazing performance across various complex scenes, with noticeable haze residuals remaining in the restored images. ICP-Dehaze demonstrates a certain level of effectiveness in some samples, but still falls short in terms of structural detail recovery and color fidelity. In contrast, our method consistently delivers superior visual quality across all test images. The restored results are significantly cleaner and more visually pleasing, with natural color reproduction and well-preserved details, without introducing noticeable artifacts or over-enhancement effects.

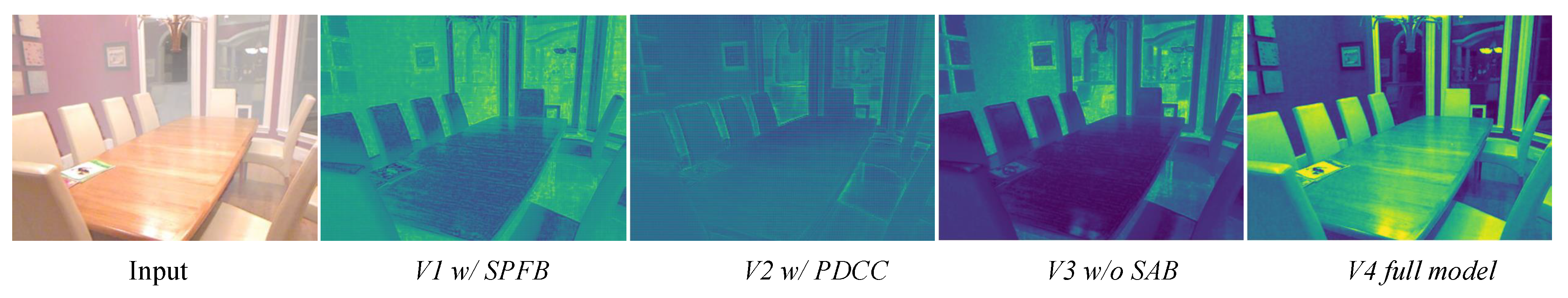

4.4. Ablation Study

Impact of Different Components in the Network. To further validate the effectiveness of each proposed component, we conduct ablation studies to analyze the contributions of the key modules, including the SPFB, the PDCC, and the SAB. We take MixDehazeNet-S as the baseline network and construct four variants based on it as follows:

- (1)

Base + SPFB → V1

- (2)

Base + HEConv → V2

- (3)

Base + SPFB + HEConv → V3

- (4)

Base + SPFB + HEConv + SAB → V4

All models are trained using the same training strategy, and the “S” variant is evaluated on the ITS-indoor test set. The experimental results are shown in

Table 7 and

Figure 11. As illustrated in

Table 7, each proposed module contributes to performance improvements in dehazing quality. In particular, the SPFB module improves PSNR by 1.77 dB, respectively, over the baseline. The PDCC module also brings notable gains. Overall, each component contributes to better dehazing performance, verifying the effectiveness of our design. We also visualize the feature maps of each module to further demonstrate their impact. As shown:

enhances some edge features but still suffers from coarse outputs and insufficient detail recovery;

improves edge and structure clarity to some extent but lacks fine-grained textures;

yields moderate global improvement, but fails to preserve table textures and background structures, resulting in blurry features. In contrast, the

, which integrates SPFB, PDCC, and SAB, produces much clearer features with better spatial sharpness and detail recovery, including more precise object boundaries. These visualizations further confirm the effectiveness of each proposed component.

Ablation Study on SPFB Module. To thoroughly validate the effectiveness of the proposed SPFB module, we designed a set of detailed ablation experiments from two perspectives: external fusion strategies and internal structural variations of the SPFB module. For the fusion strategy, we considered the following baselines: (1) SPFB-N1: The SPFB module is not used; instead, feature fusion is performed using simple element-wise addition. (2) SPFB-N2: The input RGB image is extended to four channels by appending the segmentation mask as the fourth channel and feeding it together into the dehazing network. For the internal structure of the SPFB module, we introduced the following variants: (1) SPFB-F1: The fusion with input feature F is removed, and only the intermediate semantic attention map

is fed into the function

. (2) SPFB-F2: The feature extraction branch used to obtain the semantic prior from

is removed. As shown in the results table, none of these alternatives whether in terms of fusion strategies or SPFB structural variants can match the performance of our original SPFB design. This clearly demonstrates the superior capability of our SPFB module in both structural fusion and semantic guidance. Moreover, we further analyzed the impact of inserting the SPFB module at different positions in the network. As illustrated in the

Table 8, increasing the number of inserted SPFB modules consistently improves the network performance. This progressive enhancement trend further confirms the effectiveness of the SPFB module, especially in boosting the modeling capacity of multi-level features through structural and semantic reinforcement.

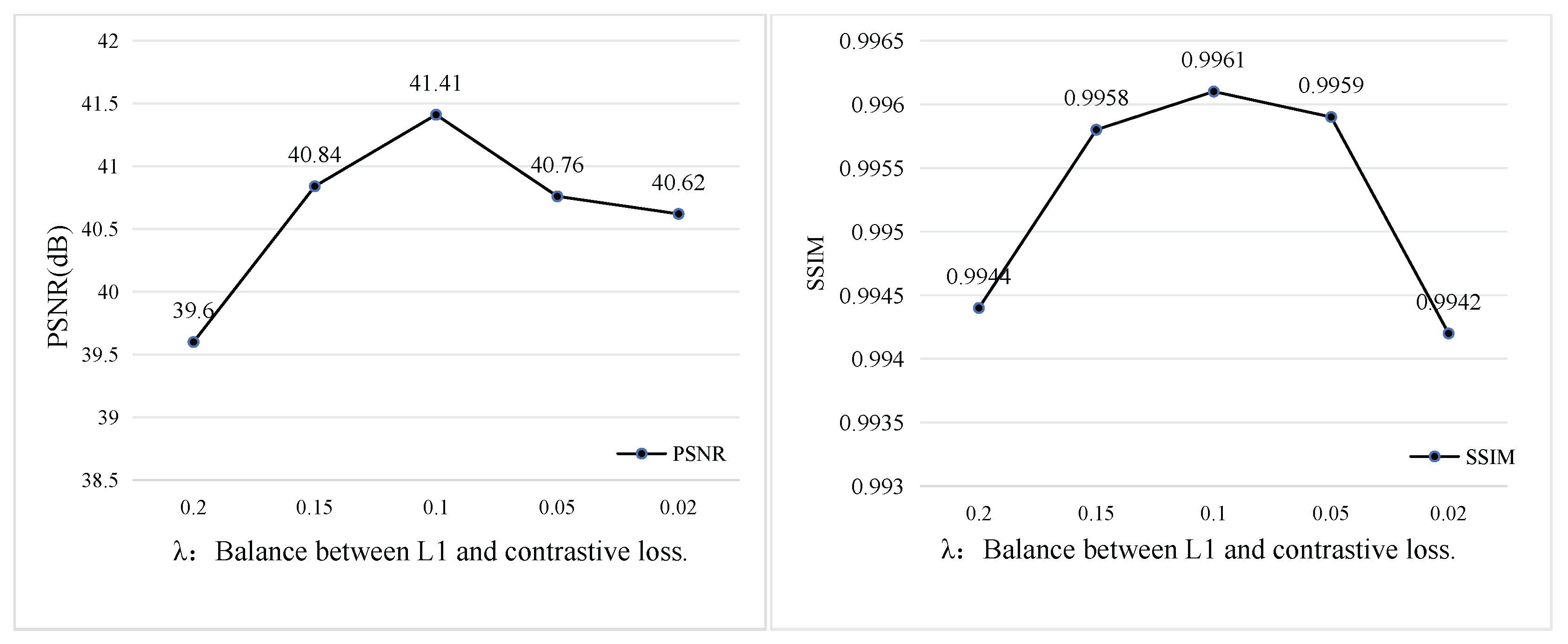

Impact of Loss Function Hyperparameters. To select the optimal hyperparameters, we conduct ablation experiments on the weight parameters of the contrastive loss and L1 loss. A penalty factor

lambda is introduced before the contrastive loss to determine its optimal contribution. As shown in

Figure 12, when

, the model achieves the best performance in both PSNR and SSIM, indicating the most effective dehazing capability.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses the limitations of traditional image dehazing methods in semantic understanding and detail restoration by proposing a novel dehazing framework, SAM2-Dehaze, which integrates semantic prior information from a large-scale pretrained model. We incorporate the SAM2 model to fully exploit its powerful capabilities in semantic segmentation and structural perception, and design three key modules: the Semantic Prior Fusion Block (SPFB), the Parallel Detail-enhanced and Compression Convolution (PDCC), and the Semantic Alignment Block (SAB). These modules work collaboratively to significantly enhance semantic consistency, detail preservation, and structural reconstruction during the dehazing process. Extensive experiments on multiple standard hazy image datasets demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms existing state-of-the-art approaches in both quantitative metrics and subjective visual quality, showing strong generalization and practical potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H.; methodology, S.L. and Z.H.; software, S.L.; validation, S.L. and Y.M.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, S.L., Y.M. and J.W.; resources, Z.H.; data curation, Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.H., Y.M. and J.W.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, Z.H.; project administration, Z.H.; funding acquisition, Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No. 242300420284), the Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (No. 252102211015), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Universities of Henan Province (No. NSFRF240820).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SAM |

Segment Anything Model |

| SPFB |

Semantic Prior Fusion Block |

| PDCC |

Parallel Detail-enhanced and Compression Convolution |

| SAB |

Semantic Alignment Block |

| ASM |

Atmospheric Scattering Model |

| DCP |

Dark Channel Prior |

| U-net |

U-shaped convolutional neural network |

| VGG16 |

Visual Geometry Group 16-layer network |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

| DEConv |

Detail Enhancement Convolution |

| CDC |

Center Difference Convolution |

| ADC |

Angle Difference Convolution |

| HDC |

Horizontal Difference Convolution |

| VDC |

Vertical Difference Convolution |

| SCConv |

Spatial-Channel Construction Convolution |

| SRU |

Spatial Reconstruction Unit |

| CRU |

Channel Reconstruction Unit |

| RDB |

Residual Dense Block |

| PSNR |

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SSIM |

Structural Similarity Index |

| FADE |

Fog Aware Density Evaluation |

| NIQE |

Natural Image Quality Evaluator |

| PIQE |

Perception-based Image Quality Evaluator |

| BRISQUE |

Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator |

References

- Ju, M.; Ding, C.; Ren, W.; et al. IDE: Image dehazing and exposure using an enhanced atmospheric scattering model. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 2180–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Ren, W.; et al. Compensation atmospheric scattering model and two-branch network for single image dehazing. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2024, 8, 2880–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, W.; Xudong, Z.; Jun, Z.; et al. Image dehazing algorithm by combining light field multi-cues and atmospheric scattering model. Opto-Electronic Engineering 2025, 47, 190634-1–190634-14. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2016, 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; et al. An image is worth 16×16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.; et al. EENet: An effective and efficient network for single image dehazing. Pattern Recognition 2025, 158, 111074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, Z.; Bai, Y.; et al. FFA-Net: Feature fusion attention network for single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2020, 34, 11908–11915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, F.L.; et al. UCL-Dehaze: Toward real-world image dehazing via unsupervised contrastive learning. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2024, 33, 1361–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; et al. Segment Anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 2023, 4015–4026.

- Zhang, C.; Han, D.; Qiao, Y.; et al. Faster Segment Anything: Towards lightweight SAM for mobile applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.14289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, N.; Gabeur, V.; Hu, Y.-T.; et al. SAM 2: Segment anything in images and videos. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.00714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Sun, J.; Tang, X. Single image haze removal using dark channel prior. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2010, 33, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Mai, J.; Shao, L. A fast single image haze removal algorithm using color attenuation prior. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2015, 24, 3522–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, D.; Avidan, S. Non-local image dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2016, 1674–1682.

- Shi, F.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, Y. Zero-Shot Sand–Dust Image Restoration. Sensors 2025, 25, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Pan, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Single image dehazing via multi-scale convolutional neural networks with holistic edges. International Journal of Computer Vision 2020, 128, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. AOD-Net: All-in-one dehazing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2017, 4770–4778.

- Zhang, H.; Patel, V. M. Densely connected pyramid dehazing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2018, 3194–3203.

- Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Ren, W.; et al. Single Image Dehazing Using Fuzzy Region Segmentation and Haze Density Decomposition. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2025. (in press). [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Shi, Z.; et al. GridDehazeNet: Attention-based multi-scale network for image dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 2019, 7314–7323.

- Wu, H.; Qu, Y.; Lin, S.; et al. Contrastive learning for compact single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2021, 10551–10560.

- Hong, M.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; et al. Uncertainty-driven dehazing network. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2022, 36, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, Z.; Lu, Z.M. DEA-Net: Single image dehazing based on detail-enhanced convolution and content-guided attention. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2024, 33, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Ye, T.; et al. Dehaze-RetinexGAN: Real-World Image Dehazing via Retinex-based Generative Adversarial Network. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 39, 7997–8005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.M.; Huang, J.R.; Lee, S.H. Image Sand–Dust Removal Using Reinforced Multiscale Image Pair Training. Sensors 2025, 25, 5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ren, W.; Tan, X.; et al. Semantic-aware dehazing network with adaptive feature fusion. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2021, 53, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; You, S.; Ila, V.; et al. Semantic single-image dehazing. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.05624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, C.; Shen, Y.; et al. SPG-Net: Segmentation prediction and guidance network for image inpainting. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.03356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; et al. Distilling semantic priors from SAM to efficient image restoration models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2024, 25409–25419.

- Li, S.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. SAM-Deblur: Let Segment Anything boost image deblurring. In ICASSP 2024 – IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing 2024, 2445–2449.

- Liu, H.; Shao, M.; Wan, Y.; et al. SeBIR: Semantic-guided burst image restoration. Neural Networks 2025, 181, 106834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; He, L. ScConv: Spatial and channel reconstruction convolution for feature redundancy. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2023, 6153–6162.

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Yan, X.; et al. USCFormer: Unified transformer with semantically contrastive learning for image dehazing. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 24, 11321–11333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gallo, O.; Frosio, I.; et al. Loss functions for image restoration with neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging 2016, 3, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ren, W.; Fu, D.; et al. Benchmarking single-image dehazing and beyond. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2018, 28, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancuti, C. O.; Ancuti, C.; Sbert, M.; et al. DENSE-HAZE: A benchmark for image dehazing with dense-haze and haze-free images. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP) 2019, 1014–1018.

- Ancuti, C. O.; Ancuti, C.; Timofte, R. NH-HAZE: An image dehazing benchmark with non-homogeneous hazy and haze-free images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops 2020, 444–445.

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; et al. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Wu, W.; Dalal, E.N. The CIEDE2000 color-difference formula: Implementation notes, supplementary test data, and mathematical observations. Color Research & Application 2005, 30, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, L.K.; You, J.; Bovik, A.C. Referenceless prediction of perceptual fog density and perceptual image defogging. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2015, 24, 3888–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Soundararajan, R.; Bovik, A.C. Making a “completely blind” image quality analyzer. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2012, 20, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatanath, N.; Praneeth, D.; Bh, M. C.; et al. Blind image quality evaluation using perception based features. In 2015 Twenty First National Conference on Communications (NCC) 2015, 1–6.

- Mittal, A.; Moorthy, A.K.; Bovik, A.C. No-reference image quality assessment in the spatial domain. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2012, 21, 4695–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C. L.; Yan, Q.; Anwar, S.; et al. Image dehazing transformer with transmission-aware 3D position embedding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2022, 5812–5820.

- Shen, H.; Zhao, Z. Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Mutual information-driven triple interaction network for efficient image dehazing. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia 2023, 7–16.

- Wu, R. Q.; Duan, Z. P.; Guo, C. L.; et al. RIDCP: Revitalizing real image dehazing via high-quality codebook priors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2023, 22282–22291.

- Zheng, Y.; Zhan, J.; He, S.; et al. Curricular contrastive regularization for physics-aware single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2023, 5785–5794.

- Lu, L. P.; Xiong, Q.; Xu, B.; et al. MixDehazeNet: Mix structure block for image dehazing network. In 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) 2024, 1–10.

- Fu, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z.; et al. Iterative Predictor-Critic Code Decoding for Real-World Image Dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2025, 12700–12709.

Figure 1.

Illustration of SAM’s robustness on different types of hazy images. The figure demonstrates that SAM can accurately segment objects even when the input is a low-quality hazy image. This observation motivates us to leverage the semantic priors extracted from SAM, a large-scale foundation model, to enhance image restoration performance.

Figure 1.

Illustration of SAM’s robustness on different types of hazy images. The figure demonstrates that SAM can accurately segment objects even when the input is a low-quality hazy image. This observation motivates us to leverage the semantic priors extracted from SAM, a large-scale foundation model, to enhance image restoration performance.

Figure 2.

The architecture of SAM2-Dehaze. The input hazy image H is processed by SAM2 to generate a semantic map . The backbone U-Net consists of five stages (G1–G5), each integrating Parallel Detail-enhanced and Compression Convolution (PDCC) and Semantic Prior Fusion Block (SPFB), and finally outputs a clear image through the Structure-Aware Block (SAB). Training uses a combination of L1 and contrastive losses.

Figure 2.

The architecture of SAM2-Dehaze. The input hazy image H is processed by SAM2 to generate a semantic map . The backbone U-Net consists of five stages (G1–G5), each integrating Parallel Detail-enhanced and Compression Convolution (PDCC) and Semantic Prior Fusion Block (SPFB), and finally outputs a clear image through the Structure-Aware Block (SAB). Training uses a combination of L1 and contrastive losses.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the Semantic Prior Fusion Block (SPFB). The SPFB unit takes the semantic map and feature map F as input. After concatenation, they are processed to generate an intermediate feature , which is then fused with guidance features from via element-wise multiplication. The output is passed to subsequent network modules to enhance semantic representation and restoration quality.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the Semantic Prior Fusion Block (SPFB). The SPFB unit takes the semantic map and feature map F as input. After concatenation, they are processed to generate an intermediate feature , which is then fused with guidance features from via element-wise multiplication. The output is passed to subsequent network modules to enhance semantic representation and restoration quality.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the Parallel Detail-enhanced and Compression Convolution (PDCC). The module consists of a DEConv branch (VDC, HDC, CDC, ADC), a Conv branch, and an SCConv branch (SRU, CRU), which are responsible for detail extraction, basic feature learning, and spatial–channel refinement, respectively. The outputs are fused and further processed by a 5×5 convolution to generate the enhanced feature representation.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the Parallel Detail-enhanced and Compression Convolution (PDCC). The module consists of a DEConv branch (VDC, HDC, CDC, ADC), a Conv branch, and an SCConv branch (SRU, CRU), which are responsible for detail extraction, basic feature learning, and spatial–channel refinement, respectively. The outputs are fused and further processed by a 5×5 convolution to generate the enhanced feature representation.

Figure 5.

Detailed structure of the Semantic Alignment Block. The generated close dehazed image is fused with the semantic-guided features to produce a finer dehazed result. Benefiting from high-level semantic information, the refined dehazed image can better preserve the structure, color, and details of objects.

Figure 5.

Detailed structure of the Semantic Alignment Block. The generated close dehazed image is fused with the semantic-guided features to produce a finer dehazed result. Benefiting from high-level semantic information, the refined dehazed image can better preserve the structure, color, and details of objects.

Figure 6.

Visual and histogram results of SOTS-indoor dataset by different methods. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 6.

Visual and histogram results of SOTS-indoor dataset by different methods. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 7.

Visual and histogram results of SOTS-outdoor dataset by different methods. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 7.

Visual and histogram results of SOTS-outdoor dataset by different methods. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 8.

Visual results of NH datasets by different methods. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 8.

Visual results of NH datasets by different methods. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 9.

Visual results of Dense datasets by different methods. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 9.

Visual results of Dense datasets by different methods. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 10.

Visual comparison on RTTS. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 10.

Visual comparison on RTTS. Zoom in for best view.

Figure 11.

Visual Comparison of Intermediate Features in Ablation Models.

Figure 11.

Visual Comparison of Intermediate Features in Ablation Models.

Figure 12.

Effect of the parameter on dehazing performance. The plots illustrate the impact of different values—used to balance the L1 loss and contrastive loss—on PSNR (left) and SSIM (right). The best performance is achieved when = 0.1, yielding the highest PSNR of 41.41 dB and the highest SSIM of 0.9961.

Figure 12.

Effect of the parameter on dehazing performance. The plots illustrate the impact of different values—used to balance the L1 loss and contrastive loss—on PSNR (left) and SSIM (right). The best performance is achieved when = 0.1, yielding the highest PSNR of 41.41 dB and the highest SSIM of 0.9961.

Table 1.

The details of the datasets used in our experiments. ITS–L represents a model of type L trained on the ITS dataset.

Table 1.

The details of the datasets used in our experiments. ITS–L represents a model of type L trained on the ITS dataset.

| Datasets |

Train (GT/Hazy) |

Test (GT/Hazy) |

Train epochs |

Pretrained weights |

| RESIDE |

ITS (1399/13990) |

SOTS-indoor (500/500) |

500 |

– |

| OTS(8970/313950) |

SOTS-outdoor (500/500) |

50 |

– |

| RTTS (4322) |

50 |

– |

| Dense-Haze |

Dense-Haze (45/45) |

Dense-Haze (5/5) |

5000 |

ITS–L |

| NH-Haze |

NH-Haze (45/45) |

NH-Haze (5/5) |

5000 |

ITS–L |

Table 2.

Model Architecture Detailed.

Table 2.

Model Architecture Detailed.

| Model Name |

Num. of Blocks |

Embedding Dims |

| SAM2-Dehaze-S |

[2, 2, 4, 2, 2] |

[24, 48, 96, 48, 24] |

| SAM2-Dehaze-B |

[4, 4, 8, 4, 4] |

[24, 48, 96, 48, 24] |

| SAM2-Dehaze-L |

[8, 8, 16, 8, 8] |

[24, 48, 96, 48, 24] |

Table 3.

Quantitative comparison on SOTS-indoor/outdoor. We report PSNR, SSIM and CIEDE2000. The symbol “–” indicates that the value is unavailable. Bold and underlined values represent the best and second-best results.

Table 3.

Quantitative comparison on SOTS-indoor/outdoor. We report PSNR, SSIM and CIEDE2000. The symbol “–” indicates that the value is unavailable. Bold and underlined values represent the best and second-best results.

| Method |

SOTS-indoor |

|

SOTS-outdoor |

| PSNR↑ |

SSIM↑ |

CIEDE2000↓ |

|

PSNR↑ |

SSIM↑ |

CIEDE2000↓ |

| DCP (TPAMI’10) |

16.61 |

0.855 |

6.7998 |

|

19.14 |

0.861 |

11.0133 |

| MSCNN (ECCV’16) |

19.84 |

0.833 |

7.6254 |

|

22.06 |

0.908 |

6.2546 |

| AOD-Net (ICCV’17) |

20.51 |

0.816 |

8.0860 |

|

24.14 |

0.920 |

8.9375 |

| GridDehazeNet (ICCV’19) |

32.16 |

0.984 |

1.7784 |

|

30.86 |

0.960 |

2.2747 |

| FFA-Net (AAAI’20) |

36.39 |

0.989 |

1.1645 |

|

33.38 |

0.984 |

2.4797 |

| AECR-Net (CVPR’21) |

37.17 |

0.990 |

1.1423 |

|

— |

— |

— |

| Dehamer (CVPR’22) |

36.63 |

0.988 |

0.9881 |

|

35.18 |

0.986 |

0.9676 |

| MIT-Net (MM’23) |

40.23 |

0.992 |

0.9920 |

|

35.18 |

0.988 |

0.9800 |

| RIDCP (CVPR’23) |

18.36 |

0.757 |

9.9759 |

|

21.62 |

0.833 |

7.9011 |

| C2PNet (CVPR’23) |

42.46 |

0.995 |

0.6997 |

|

36.68 |

0.990 |

0.9762 |

| DEA-Net (TIP’24) |

41.21 |

0.992 |

0.7994 |

|

36.24 |

0.989 |

0.9771 |

| SAM2-Dehaze-S |

41.41 |

0.996 |

0.7766 |

|

35.62 |

0.982 |

1.1625 |

| SAM2-Dehaze-B |

41.56 |

0.996 |

0.7526 |

|

35.69 |

0.985 |

0.9956 |

| SAM2-Dehaze-L |

42.83 |

0.997 |

0.6929 |

|

36.22 |

0.989 |

0.9823 |

Table 4.

Computational efficiency comparison. Bold and underlined values denote the best and second-best results, respectively.

Table 4.

Computational efficiency comparison. Bold and underlined values denote the best and second-best results, respectively.

| Method |

Overhead |

| Param. (M) |

MACs (G) |

Latency (ms) |

| GridDehazeNet (ICCV’19) |

0.96 |

21.43 |

39.69 |

| FFA-Net (AAAI’20) |

4.45 |

287.53 |

164.94 |

| AECR-Net (CVPR’21) |

2.61 |

52.20 |

36.26 |

| Dehamer (CVPR’22) |

132.45 |

48.93 |

— |

| MIT-Net (MM’23) |

2.73 |

16.54 |

14.57 |

| C2PNet (CVPR’23) |

7.17 |

460.95 |

173.86 |

| DEA-Net (TIP’24) |

3.65 |

34.04 |

16.12 |

| SAM2-Dehaze-S |

5.06 |

43.07 |

97.93 |

| SAM2-Dehaze-B |

9.78 |

71.36 |

242.21 |

| SAM2-Dehaze-L |

19.24 |

127.96 |

519.89 |

Table 5.

Quantitative comparison on the Dense-Haze and NH-Haze datasets. Bold and underlined values denote the best and second-best results, respectively.

Table 5.

Quantitative comparison on the Dense-Haze and NH-Haze datasets. Bold and underlined values denote the best and second-best results, respectively.

| Method |

Dense-Haze |

|

NH-Haze |

| PSNR↑ |

SSIM↑ |

CIEDE2000↓ |

PSNR↑ |

SSIM↑ |

CIEDE2000↓ |

| DCP (TPAMI’10) |

11.06 |

0.417 |

23.5067 |

|

13.28 |

0.482 |

18.0389 |

| AOD-Net (ICCV’17) |

12.82 |

0.468 |

24.0294 |

|

15.69 |

0.573 |

19.3886 |

| FFA-Net (AAAI’20) |

16.24 |

0.561 |

13.8080 |

|

16.29 |

0.562 |

13.1681 |

| DeHamer (CVPR’22) |

16.63 |

0.587 |

12.8506 |

|

20.66 |

0.686 |

9.1162 |

| MIT-Net (MM’23) |

16.97 |

0.623 |

12.5450 |

|

21.25 |

0.712 |

8.5118 |

| RIDCP (CVPR’23) |

8.09 |

0.438 |

32.2540 |

|

12.27 |

0.503 |

20.2104 |

| MixDehazeNet-L (IJCNN’24) |

15.90 |

0.579 |

12.0986 |

|

21.01 |

0.827 |

9.5122 |

| SAM2-Dehaze-L |

20.61 |

0.725 |

8.5909 |

|

22.02 |

0.831 |

8.5108 |

Table 6.

Quantitative comparison on RTTS. Bold and underlined values indicate the best and second-best results, respectively.

Table 6.

Quantitative comparison on RTTS. Bold and underlined values indicate the best and second-best results, respectively.

| Method |

FADE ↓ |

NIQE ↓ |

PIQE ↓ |

BRISQUE ↓ |

| GridDehazeNet (ICCV’19) |

1.72 |

4.85 |

23.85 |

29.73 |

| FFA-Net (AAAI’20) |

2.07 |

4.93 |

24.59 |

34.44 |

| Dehamer (CVPR’22) |

1.92 |

4.91 |

23.31 |

34.55 |

| C2PNet (CVPR’23) |

2.06 |

5.03 |

25.05 |

34.80 |

| MIT-Net (MM’23) |

1.97 |

4.92 |

23.25 |

34.37 |

| DEA-Net (TIP’24) |

1.90 |

4.92 |

24.95 |

31.99 |

| IPC-Dehaze (CVPR’25) |

1.15 |

4.08 |

12.34 |

24.79 |

| SAM2-Dehaze (Ours) |

1.71 |

4.75 |

23.23 |

30.09 |

Table 7.

Ablation study on the RESIDE-indoor dataset. Bold values indicate the best results.

Table 7.

Ablation study on the RESIDE-indoor dataset. Bold values indicate the best results.

| Variants |

baseline |

V1 |

V2 |

V3 |

V4 |

| MixDehazeNet-S |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| SPFB |

w/o |

✓ |

w/o |

✓ |

✓ |

| HEConv |

w/o |

w/o |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| SAB |

w/o |

w/o |

w/o |

w/o |

✓ |

| PSNR |

39.47 |

41.24 |

40.26 |

41.37 |

41.41 |

| SSIM |

0.995 |

0.996 |

0.995 |

0.996 |

0.996 |

Table 8.

Ablation study on different fusion methods (left) and SPFB insertion locations (right). Bold values indicate the best results.

Table 8.

Ablation study on different fusion methods (left) and SPFB insertion locations (right). Bold values indicate the best results.

| Variants |

|

Location |

| Method |

PSNR |

SSIM |

|

Block |

PSNR |

SSIM |

| SPFB-N1 |

38.91 |

0.994 |

|

G-1 |

40.16 |

0.995 |

| SPFB-N2 |

40.26 |

0.995 |

|

G-2 |

40.66 |

0.995 |

| SPFB-F1 |

41.14 |

0.996 |

|

G-3 |

40.89 |

0.995 |

| SPFB-F2 |

41.24 |

0.996 |

|

G-4 |

41.31 |

0.996 |

| SPFB |

41.41 |

0.996 |

|

G-5 |

41.41 |

0.996 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).