1. Introduction

Large Language Model (LLM) based coding agents represent a paradigm shift in software engineering, moving beyond simple code completion to autonomously planning, implementing, and refining solutions. These agents operate through an iterative agentic loop: they observe the current state of the development environment and task context, reason about appropriate actions using the foundation model, execute actions through tool calls (such as reading/writing files, running tests, or searching code), receive feedback from the environment, and repeat until the task is complete.

The critical bottleneck in this loop is the initial observation phase: gathering relevant code context from the target repository. Modern codebases frequently exceed thousands of files and millions of lines of code, far beyond the effective context window of even the most advanced language models. An agent cannot simply ingest an entire codebase; it must selectively retrieve the subset of code that is relevant to the task at hand. The quality of this retrieval directly determines whether the agent can reason about the correct architectural patterns, dependencies, conventions, and implementation details needed to generate appropriate code.

Code retrieval for agents has evolved along several distinct technical trajectories. Lexical search approaches use pattern-matching tools like grep and ripgrep to locate code based on exact or regex-based text matching. Semantic search techniques, typically implemented through Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipelines, embed code chunks into vector spaces and retrieve based on conceptual similarity rather than keyword overlap. Language Server Protocol (LSP) integration provides structured symbol navigation (go-to-definition, find-references, and workspace symbol search) mirroring the tools used by human developers in IDEs. Agentic search strategies give models direct access to repository primitives (file listing, pattern search, shell commands) and allow them to dynamically compose retrieval queries at inference time. Finally, multi-agent architectures delegate retrieval to specialized sub-agents that handle context gathering independently from the primary coding agent.

Despite the rapid proliferation of these techniques, systematic evaluation remains scarce. Leading coding agents make divergent architectural choices: some rely entirely on lexical tools, others build sophisticated semantic indexes, and many employ hybrid approaches. Yet practitioners lack rigorous comparative data to guide these decisions. This paper investigates the fundamental trade-offs between retrieval techniques through qualitative analysis of how production coding agents approach code search in realistic software engineering tasks.

The generative prowess of the LLMs that power these agents is undeniably critical. LLMs possess vast stores of knowledge learned from extensive training on public repositories, including billions of lines of code. However, this parametric knowledge, while powerful, is inherently static and general-purpose. When applied within the scope of a specific software project, standalone LLMs exhibit several critical limitations that curtail their effectiveness and reliability.

Project-Specific Context. The model’s ability to generate syntactically correct code is of little value if that code is contextually inappropriate, architecturally inconsistent, or functionally incorrect within the scope of a specific project. Every software project has its own unique architecture, design patterns, coding conventions, and dependencies. LLMs, trained on a broad corpus of public code, lack awareness of these project-specific nuances. As a result, they may generate code that is syntactically valid but misaligned with the project’s architectural principles or coding standards.

Knowledge Cutoff Date. LLMs have a fixed knowledge cutoff date, meaning they are unaware of any developments, libraries, frameworks, or best practices that emerged after their training data was collected. In the fast-evolving landscape of software development, this limitation is significant. New programming frameworks and libraries are continually introduced, and existing ones evolve rapidly. For example, without documentation, models cannot update a codebase from Tailwind 3 to Tailwind 4.

1 This creates a gap between the model’s training and the current state of the software ecosystem, which can lead to outdated or suboptimal code suggestions.

Ability to Test and Debug. While LLMs can generate code, the code is of no use if it doesn’t work as intended. They lack context on how to test and debug code within an existing codebase.

Context Limitation. With new models like Claude Sonnet 3.7, 4.0 [

1] and GPT-5 [

2], reasoning isn’t the bottleneck anymore. Context quality is. According to the DeepMind technical report [

3], models with 1M context window like Gemini 2.5-pro [

4] only utilize 100k window for quality reasoning.

2 The content supplied within that context window becomes critical.

Overall, code retrieval is the process by which an agent sources relevant information (code snippets, guidelines, documentation, architectural patterns, and project-specific conventions) from the target codebase to inform its generation process. The choice of retrieval technique dictates the agent’s capacity to understand the existing context, handle the complexity of large and unfamiliar repositories, and generate code that is not just plausible in isolation but correct and appropriate for the specific task at hand.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Brief History of Development Environments

In the early days of interactive programming, the development environment was the command line, and the primary tool was the text editor. Two editors from this era, vi and Emacs, came to represent two distinct and enduring philosophies of tool design.

Developers were caught in a tedious and inefficient iterative cycle: write code in a text editor, save the file, switch to the command line to invoke a compiler, manually read the error messages (which often only provided line numbers), and then switch back to the editor to navigate to the correct line and fix the bug. Each step was a manual context switch that broke concentration and slowed progress [

5].

This gave birth to the integrated development environment (IDE), which combined editing, building, and debugging into a single application [

6].

In 2016, Microsoft released the Language Server Protocol (LSP)

3 [

7]. LSP decoupled language-specific intelligence (like code completion and error checking) from the editor itself, allowing any language to gain deep IDE support in any editor that implemented the protocol. This led to a renaissance in editor innovation, with lightweight editors like Visual Studio Code and Sublime Text gaining popularity alongside traditional IDEs like IntelliJ and Eclipse.

These days, programmers typically leverage IDE features such as IntelliSense for autocompletion, fuzzy search for quick file navigation, and plugins for version control. These tools emphasize human-centric interfaces, with searches often based on keywords or partial matches to handle typos or incomplete queries.

2.2. Lexical Search

The first major breakthrough in automated code retrieval came in 1973 with the creation of the grep utility at Bell Labs [

8]. The tool, whose name derives from the

ed editor command

g/re/p (global / regular expression / print), was written by Ken Thompson to solve a practical problem: the ed text editor could not search through the large text files of The Federalist Papers because it had to load the entire file into memory. Thompson extracted the regular expression matching code from ed into a standalone tool that could process files sequentially, regardless of their size.

grep was a revolutionary tool for developers. For the first time, they had an automated, powerful, and fast way to search across entire directories of source code for specific strings, variable names, function calls, or complex patterns using regular expressions. It became the prototypical software tool, embodying the Unix philosophy of small, single-purpose utilities that could be combined to perform complex tasks. Variants like egrep and fgrep were later added to support extended regular expressions and fixed-string searches, respectively.

The principles embodied by grep have been refined and optimized in modern tools specifically engineered for searching large codebases. A prominent example is

ripgrep (

rg) [

9], a line-oriented search tool built in Rust that is significantly faster than grep in many common developer scenarios. Its performance advantage stems from being built on Rust’s highly optimized regex engine, which uses finite automata and SIMD, and its ability to perform searches in parallel. Crucially for programmers,

ripgrep offers smarter defaults for code search: it automatically searches recursively, respects rules in .gitignore files, and skips hidden files and binaries. This focus on the developer workflow has led to its adoption within other popular tools; for instance, Visual Studio Code uses

ripgrep internally for its file search functionality.

While grep remains a ubiquitous and powerful utility, tools like ripgrep represent the next evolutionary step in lexical search, tailored for the scale and structure of modern software projects.

2.3. Semantic Search

Semantic code search is the task of retrieving relevant code given a natural language query. Instead of matching keywords, it aims to understand the intent and contextual meaning behind a user’s query. It operates on the principle of conceptual matching rather than literal matching. This approach aims to bridge the gap between natural language queries and programming implementations, understanding conceptual relationships rather than requiring exact keyword matches [

10].

While search for natural language documents and even images has made great progress, code search remains unsatisfying. Standard information retrieval methods do not work well for code search because there is often little shared vocabulary between search terms and results. For example, a method called

deserialize_JSON_obj_from_stream may be a correct result for the query "read JSON data," despite having no overlapping keywords. [

10]

2.3.1. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) for Code

The core idea behind RAG is to ground the LLM in external, authoritative knowledge, thereby reducing the likelihood of generating factually incorrect or contextually inappropriate responses.

4 When applied to software development, the codebase itself becomes the external knowledge base. The RAG pipeline for code involves steps such as:

Ingestion and Chunking: The source code of a project is first parsed and divided into smaller, meaningful units or "chunks." This step is more complex for code than for plain text. Naive splitting can break apart logical units. Therefore, effective strategies often use syntax-aware chunkers, for instance, those based on tree-sitter [

11],

5 to split code along logical boundaries like functions, classes, or methods, ensuring that each chunk is a complete, coherent unit [

12].

Embedding and Indexing: Each code chunk is then processed by an embedding model to produce a vector representation. These vectors are stored and indexed in a specialized vector database, which is optimized for efficient high-dimensional similarity search [

13,

14].

Retrieval: When a developer poses a query to the coding agent, the query is also converted into a vector using the same embedding model. The vector database is then queried to find the code chunks whose vectors are most similar to the query vector. [

14]

Augmentation and Generation: The content of the top-ranked retrieved code chunks is then concatenated with the original user query. This combined text, rich with relevant context from the actual codebase, is then fed into the LLM’s prompt. The LLM uses this augmented context to generate a final response that is grounded in the project’s specific code and conventions [

15].

Empirical studies have validated the effectiveness of RAG for code generation [

16,

17]. However, they also reveal important nuances. Some research indicates that not all retrieved information is equally helpful [

17]. While providing contextual code from the current file and relevant API documentation significantly boosts performance, retrieving "similar code" from other parts of the repository can sometimes introduce noise and degrade the quality of the final output.

However, industry practitioners have raised strong counter-arguments against the universal applicability of RAG for coding agents. Figures like Nick Pash, Head of AI at Cline, argue that RAG can be a ’seductive trap’ for coding tasks [

18]. The core of this critique is that code is inherently logical and structured; unlike unstructured text, it does not always benefit from being broken down into semantically similar but contextually isolated chunks [

pash2024ragcode]. This approach, critics argue, is fundamentally different from how a senior engineer familiarizes themselves with a new project by exploring folder structures, following import statements, and reading whole files to build a mental model of the architecture. Indexing an entire codebase with embeddings is seen as not only potentially unnecessary but also a security risk, leading some of the most prominent agent development teams to abandon RAG in favor of more direct, exploratory methods [

19].

2.3.2. Code Knowledge Graphs

A Code Knowledge Graph (CKG) is a specialized knowledge graph that represents a codebase as a network of interconnected entities. Nodes represent code elements such as classes, functions, variables, and files, while edges capture relationships including function calls, inheritance hierarchies, data dependencies, and cross-file references. This structured representation provides a deeper, more contextual understanding of software projects compared to traditional flat text analysis.

CKGs offer three key advantages for code retrieval: (a) they narrow the search space to highly relevant entities through explicit relationship paths, (b) they expose traceable multi-hop connections that improve explainability, and (c) they return compact structured context rather than verbose file dumps, thereby improving recall, precision, and auditability for repository-scale tasks [

20].

Recent empirical work demonstrates the effectiveness of coupling LLMs with code graph databases. CodexGraph, for instance, implements an LLM-graph database architecture where agents issue graph queries to retrieve structure-aware context for cross-file tasks, consistently outperforming similarity-based retrieval baselines [

21]. Similarly, repository-aware knowledge graphs that unify code entities with repository artifacts (issues, pull requests) have shown remarkable success in bug localization, with 69.7% of successfully localized bugs requiring multi-hop graph traversals and achieving 84.3% file-level coverage [

20].

However, CKGs require substantial engineering investment. Building and maintaining repository-level knowledge graphs involves complex challenges: multi-language parsers, schema design for diverse codebases, incremental updates in continuous integration pipelines, graph database optimization for large monorepos, and precise alignment between textual artifacts and code symbols.

2.4. Language Server Protocol (LSP)

The Language Server Protocol (LSP) is an editor server API that exposes symbol resolution (go-to-definition, find-references), type information, AST fragments, and diagnostics, making it a natural, structured source of semantic signals for retrieval in coding agents [

22].

Unlike lexical search tools, LSP maintains comprehensive symbol tables and abstract syntax trees, enabling precise code navigation that understands language semantics [

22].

LSP’s strength for coding agents lies in its ability to perform global and precise code retrieval across programming environments, supporting IDE-like functionality such as go-to-definition, find-references, and workspace symbol search. The protocol handles complex scenarios that text-based search cannot, such as resolving overloaded methods, navigating inheritance hierarchies, and distinguishing identically named symbols across different scopes.

Recent implementations in multi-agent systems demonstrate LSP’s effectiveness for agent workflows. The MarsCode Agent framework leverages LSP for fuzzy positioning techniques and multiple search strategies, achieving 88.3% file localization accuracy across 12 programming languages [

23]. LSP integration also enables sophisticated diagnostic workflows, allowing agents to validate code modifications and ensure syntactic correctness before application.

However, LSP requires initial setup and configuration for each project, and its optimization for human-interactive workflows may not align perfectly with agentic coding patterns. Despite these limitations, LSP provides a mature, standardized approach that bridges the gap between lexical search and deep semantic understanding, making it valuable for precise code retrieval in agent systems [

24].

2.5. Agentic Search

Agentic search represents a class of approaches where an LLM-driven agent is given repository and system-level primitives (e.g., list/find files, read files with

rg/

cat, pattern search like

grep, run

bash commands, or perform web lookups). The LLM itself decides at runtime which sequence of actions to take to gather the precise code context needed to answer a query. This interleaving of reasoning and acting (deciding and issuing tool calls, then conditioning on observations) is the core idea behind ReAct-style and tool-using agent paradigms [

25].

Crucially, the retrieval strategy is not hand-coded. Instead, developers expose a toolbox (find/read/search/exec/web), and the model synthesizes queries, selects files, composes

rg/

grep patterns, or elects to run commands to produce runtime traces, effectively deciding how to gather relevant code context without an explicit procedural retrieval plan. Work on automatic tool-use and action-interleaving (e.g., Toolformer, ReAct, and program-execution designs) documents how language models can learn or be prompted to choose and integrate such external operations [

26].

Concrete tooling examples exposed to agents include repository navigation (list/find), symbol or pattern search (

rg/

grep), executing builds/tests or running shell tools (

bash), and web/API lookups for documentation and package sites. Recent repository-aware agents and frameworks (e.g., CodeNav and RepoAgent family) explicitly implement these primitives and demonstrate how agents use them to assemble the runtime context needed for accurate retrieval and downstream code tasks [

27].

Empirically, several recent studies that instrument LLM agents with repository and shell-level tools report substantive improvements on repository-level tasks, including better pinpointing of relevant files and snippets, more reliable answers, and higher task success rates compared to single-shot or plain RAG baselines [

24,

27]. However, many systems combine multiple improvements, so isolated ablations comparing agentic versus non-agentic approaches with identical models and rerankers are required to quantify the causal effect precisely.

This empirical advantage is further validated by industry adoption patterns. Claude Code developers made a deliberate architectural choice to avoid RAG in favor of agentic search. In early development, the team experimented extensively with off-the-shelf RAG solutions, including embedding-based retrieval using Voyage

6 and various other RAG variants. However, these experiments were ultimately abandoned when agentic search consistently outperformed RAG approaches across both internal benchmarks and subjective quality evaluations.

7 This decision by a leading AI lab suggests that for production-grade coding agents operating at scale, the flexibility and context-awareness of agentic retrieval may offer advantages that static embedding-based approaches cannot match.

In summary, agentic search allows the model to compose repository and runtime-level actions at inference time to gather precisely the code context it needs. Early repository-aware agent work shows clear practical gains, but rigorous ablations are needed to isolate the benefit of tool-driven retrieval.

2.6. Multi-Agent and Sub-Agent Architectures

As coding tasks grow in complexity, a natural question emerges: should retrieval be handled by the same agent that performs code generation, or be delegated to a specialized retrieval agent? Multi-agent architectures partition responsibilities across multiple LLM-powered agents, each optimized for distinct subtasks such as code search, analysis, generation, and testing.

The architectural choice between integrated and decomposed retrieval has significant implications. In integrated architectures, a single agent uses retrieval tools (grep, LSP, RAG) as part of its general-purpose toolkit, interleaving search with reasoning and code modification. In contrast, multi-agent systems employ specialized retrieval agents that can be invoked by a coordinator or primary coding agent when context gathering is needed.

Proponents of specialized retrieval agents argue that decomposition enables focused optimization: a retrieval agent can be fine-tuned or prompted specifically for search quality, employ domain-specific ranking heuristics, and maintain dedicated state for iterative refinement of search queries [

28]. Multi-agent frameworks like AutoGen and MetaGPT demonstrate how orchestrating multiple specialized agents can improve task decomposition and parallel execution [

29,

30].

However, specialized retrieval introduces coordination overhead. The primary agent must recognize when retrieval is needed, formulate explicit requests to the retrieval agent, and integrate returned context into its working memory. Recent empirical work suggests that for many repository-level coding tasks, well-prompted single agents with direct tool access can match or exceed the performance of multi-agent systems while avoiding inter-agent communication costs [

31].

A critical challenge in multi-agent architectures is context fragmentation: when agents operate in parallel without shared context, each action embeds implicit decisions that may conflict with decisions made by other agents. The Cognition team behind Devin argues that current LLMs lack robust mechanisms for decision synchronization across agents, recommending single-threaded approaches with explicit coordination points rather than naive parallel decomposition [

32]. This suggests that the key distinction is not single-agent versus multi-agent, but rather poorly coordinated versus well-coordinated agent systems with clear synchronization boundaries.

The debate mirrors broader questions in agentic system design: whether task decomposition should be architectural (multiple specialized agents) or behavioral (single agent with diverse tools and instructions). For code retrieval specifically, the choice depends on factors including task complexity, codebase scale, retrieval technique sophistication, and whether retrieval quality benefits from dedicated optimization versus tight integration with the generation loop.

3. Study Design

3.1. Research Objectives

Despite the rapid proliferation of coding agents and retrieval techniques, fundamental questions about their effectiveness remain unresolved. Practitioners report different experiences, and the lack of standardized evaluation makes it difficult to compare approaches systematically. This study addresses three central questions:

RQ1: Does semantic search provide advantages over lexical search for coding agents?

While RAG has transformed many AI applications, leading practitioners are divided on its value for autonomous coding. Some view RAG-based semantic search as essential for handling large, unfamiliar codebases, enabling agents to find conceptually relevant code even without exact keyword matches. Others characterize it as "cognitive overhead" that degrades reasoning quality by introducing noise through decontextualized code chunks [

18] [

pash2024ragcode]. Early experiments with off-the-shelf RAG solutions in prominent coding agents showed mixed results, with some teams ultimately abandoning semantic indexing in favor of agentic lexical search [

19]. This question seeks to understand under what conditions, if any, semantic retrieval provides measurable benefits to agent performance.

RQ2: Do agents benefit from the same retrieval tools that human programmers use?

Human developers rely heavily on IDE-integrated tools like LSP servers for precise code navigation: go-to-definition, find-references, and symbol search. These tools provide structured, semantically-aware retrieval that understands language constructs, scope, and cross-file dependencies. However, LSP was designed for interactive human workflows, not autonomous agent loops. It remains unclear whether agents can effectively leverage LSP’s precision, or whether simpler lexical tools like grep and ripgrep are more aligned with how models explore and synthesize context. This question investigates whether human-centric tooling translates to agent-centric performance.

RQ3: Does specialized retrieval delegation to sub-agents improve coding agent performance?

As coding tasks grow more complex, some systems employ multi-agent architectures where a dedicated retrieval agent handles context gathering, separate from the primary coding agent. This decomposition theoretically enables focused optimization of retrieval quality and parallel execution. However, it introduces coordination overhead and inter-agent communication costs. Single-agent systems with integrated tool access may achieve comparable or superior performance by tightly coupling retrieval with generation. This question examines whether architectural decomposition of retrieval provides measurable advantages over integrated approaches.

3.2. Research Approach

Answering these research questions requires both qualitative insight into practitioner decision-making and an understanding of how retrieval mechanisms are implemented in practice. This study adopts an exploratory, qualitative approach aimed at creating a rigorous foundation for quantitative benchmarking of retrieval techniques in coding agents.

Our objective is to conduct qualitative analysis of how leading coding agents approach code retrieval, document their strategies and trade-offs, and build hypotheses around creating a comprehensive benchmark for evaluating retrieval performance. We achieve this through manual experimentation with multiple agents on controlled tasks, analyzing their retrieval strategies, tool usage patterns, and resource consumption. The goal is to understand the diversity of approaches, surface design trade-offs, identify metrics that correlate with practical performance, and establish the methodological foundation for future quantitative evaluation.

This exploratory study answers the core research questions while generating insights that will inform the design of a rigorous, quantitative benchmark for evaluating retrieval techniques across diverse tasks, repositories, and agent configurations. The benchmark development, including controlled experiments with isolated variables, automated instrumentation, and statistical analysis, is discussed in the Future Work section.

3.3. Study Methodology

3.3.1. Task Selection

To study retrieval behavior in a realistic setting, we selected a non-trivial refactoring task on an open-source production codebase. The task requires multi-file code search, understanding of architectural patterns, and contextual reasoning: characteristics representative of real-world software engineering work.

Repository: InfraGPT, an open-source DevOps debugging agent [

33]. The repository contains over 50,000 lines of code across 338 files. It is a monorepo with 5 major components (cli agent, website, console, backend, and background agent service). Its moderate size and clear architectural boundaries make it suitable for controlled observation while remaining representative of practical coding agent use cases.

Table 1.

Repository code statistics showing language distribution.

Table 1.

Repository code statistics showing language distribution.

| Language |

Files |

Lines |

Blank |

Comment |

Code |

| JSON |

12 |

23,401 |

2 |

0 |

23,399 |

| Go |

97 |

12,334 |

1,693 |

348 |

10,293 |

| TypeScript JSX |

58 |

8,070 |

685 |

604 |

6,781 |

| Python |

63 |

5,762 |

1,109 |

349 |

4,304 |

| TypeScript |

26 |

2,700 |

326 |

292 |

2,082 |

| Markdown |

30 |

2,692 |

701 |

0 |

1,991 |

| JavaScript |

7 |

821 |

64 |

179 |

578 |

| SQL |

25 |

666 |

86 |

98 |

482 |

| Bourne Shell |

5 |

357 |

64 |

89 |

204 |

| CSS |

3 |

173 |

12 |

1 |

160 |

| Toml |

4 |

120 |

15 |

0 |

105 |

| Makefile |

1 |

76 |

9 |

8 |

59 |

| Protobuf |

2 |

88 |

25 |

21 |

42 |

| YAML |

1 |

41 |

8 |

0 |

33 |

| HTML |

1 |

20 |

3 |

0 |

17 |

| Docker |

1 |

38 |

10 |

11 |

17 |

| Autoconf |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

| Plain Text |

1 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| Total |

338 |

57,366 |

4,813 |

2,000 |

50,553 |

Retrieval Task description: Find GitHub connector interface implementations. This task requires:

Identifying the correct service directory where the GitHub connector is located across multiple folders and services

Finding the location where the GitHub connector interface is defined across multiple files

Understanding existing methods and validating whether they implement the GitHub connector interface

The task’s multi-file, context-dependent nature stresses retrieval mechanisms and reveals how agents gather and synthesize distributed code context.

3.3.2. Agent Selection

We selected prominent coding agents that represent diverse architectural paradigms and retrieval mechanisms. Selection criteria included:

Adoption and community engagement (measured by GitHub stars, issue activity, and social media discussion),

Diversity of retrieval approaches (agentic search, semantic indexing, LSP integration, multi-agent architectures), and

Availability for analysis through either open-source code or comprehensive documentation.

To understand retrieval implementation strategies, we analyzed both the source code and documentation of these agents. For open-source agents, we examined the codebase directly to understand retrieval mechanisms, tool implementations, and architectural decisions. Specifically, we analyzed the source code of Codex CLI [

34], Gemini CLI [

35], Cline [

36], and Aider [

37]. For closed-source agents with comprehensive public documentation, we studied their documented architecture, API specifications, and design rationale. Specifically, we analyzed the documentation of Claude Code [

38], Amp [

39], and Cursor [

40]. For LSP integration experiments, we utilized an open-source MCP server implementation [

41] to enable Language Server Protocol capabilities in Claude Code.

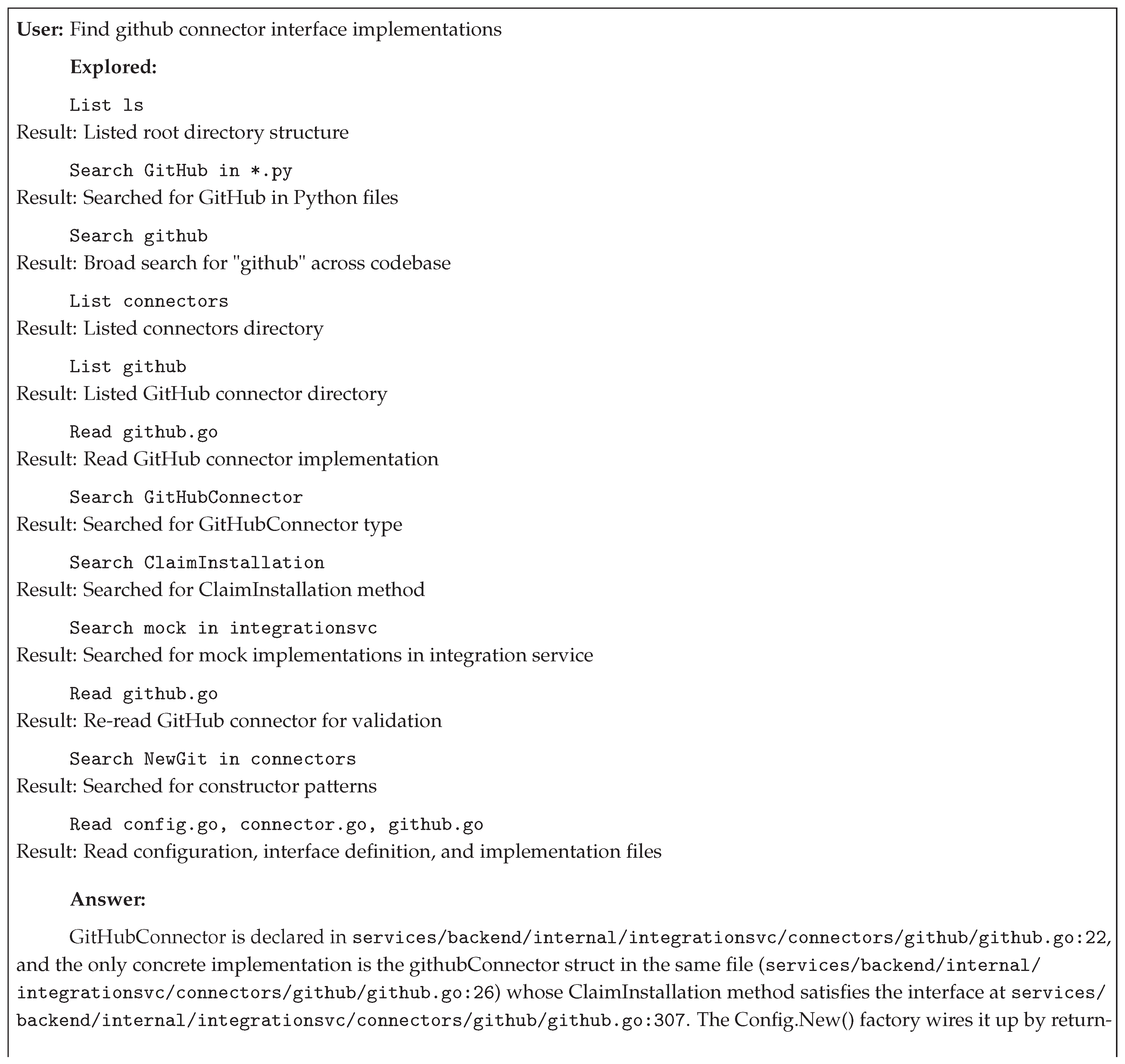

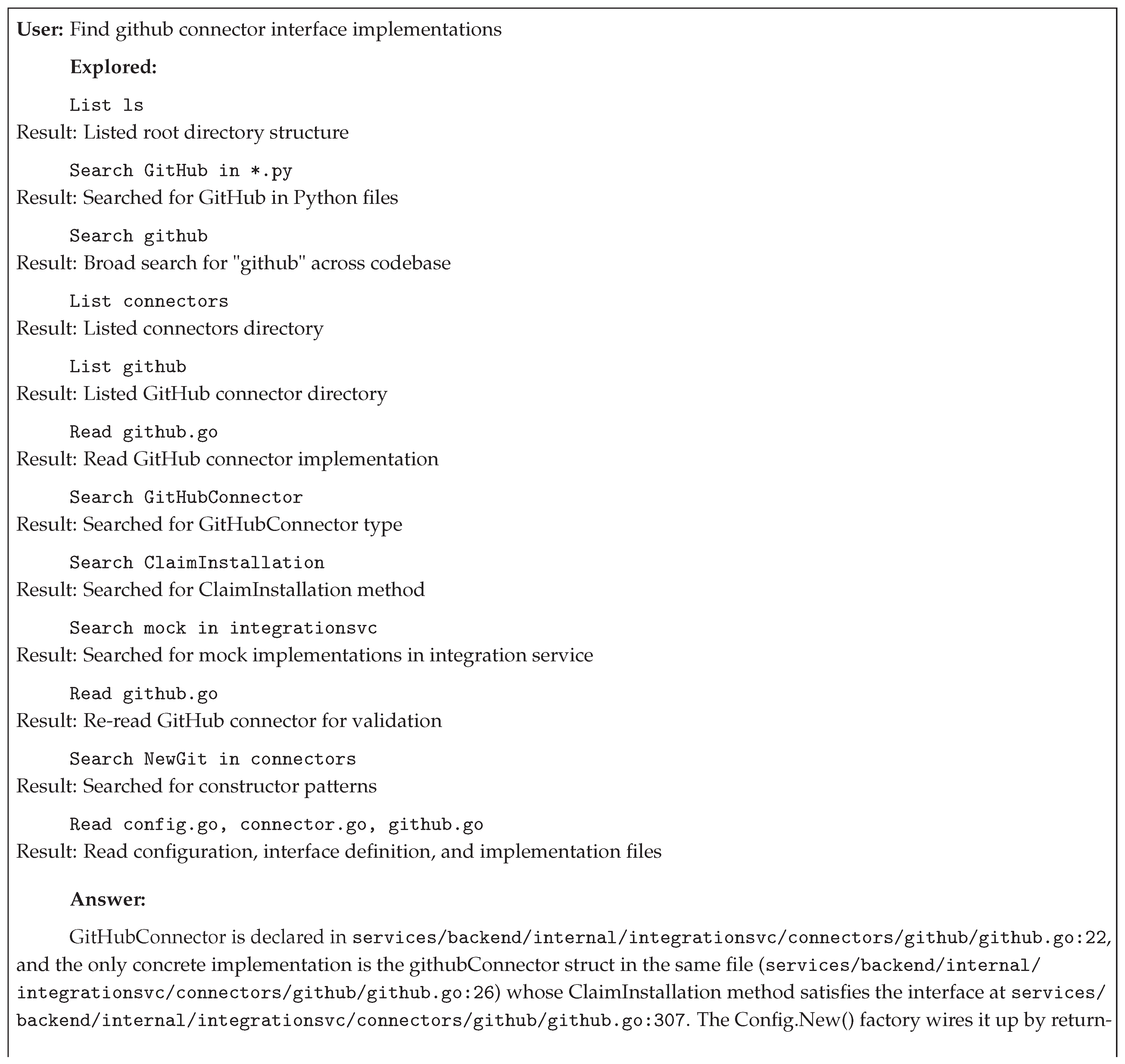

The selected agents, detailed in

Table 3, include Claude Code (agentic search with custom tools), Gemini CLI (agentic search with tool orchestration), Codex CLI (shell command orchestration), Cursor (hybrid semantic-lexical indexing), and Amp (hybrid multi-tool with guided context). This set spans CLI-native and IDE-integrated paradigms, explicit and implicit context provisioning, and single-agent and multi-agent architectures.

3.3.3. Data Collection Protocol

For each agent, we executed the retrieval task multiple times to account for non-deterministic LLM behavior and capture variability in retrieval strategies. All runs used the same task prompt and initial repository state. We employed Sonnet 4.5 [

1], GPT-5 [

2], and Gemini 2.5 Pro [

4] in that order as the underlying models when configurable, selecting state-of-the-art reasoning models to isolate retrieval performance from model capability limitations.

For each run, we collected:

Qualitative observations: Retrieval strategy (tools invoked, search patterns, file exploration order), decision-making transparency (whether the agent’s retrieval logic is interpretable), and notable behaviors (iterative refinement, context re-gathering, tool failures).

Quantitative metrics: Context window utilization as our primary metric (total tokens consumed including input, output, and reasoning). In addition, we recorded cost per run (based on model pricing), tool call counts (categorized by type: file read, search, navigation, execution), and task completion status.

Execution traces: Trace of agent interactions, full chat logs or code files, and retrieved context snapshots (which files/snippets were included in prompts).

All execution traces are documented and will be made available in the paper’s Appendix section to support reproducibility and community scrutiny.

3.3.4. Analysis Approach

Our analysis is primarily qualitative and comparative, aimed at identifying patterns and trade-offs rather than establishing definitive causal claims. We perform:

Cross-agent comparison: Systematic comparison of retrieval strategies, identifying commonalities (e.g., all agents start with directory exploration) and divergences (e.g., semantic vs. lexical search, LSP vs. grep).

Metric correlation analysis: Examining whether token consumption, cost, or tool call patterns correlate with task completion success and output quality (assessed through manual code review).

Tool usage characterization: Categorizing which retrieval primitives each agent employs, how frequently, and in what sequences. This reveals whether certain tool combinations are more effective.

Failure mode identification: Documenting context window utilization from retrieval task executions. We analyze how different retrieval strategies impact context efficiency and identify scenarios where the agent drifts from the task, leading to context rot.

The exploratory nature of this study means findings are hypothesis-generating rather than hypothesis-testing. Our goal is to build intuition, surface unexpected behaviors, and identify promising directions for rigorous quantitative evaluation in future work.

3.4. Scope and Limitations

This exploratory study has several important limitations:

Single task, single repository: Findings may not generalize across different task types (bug fixing, feature addition, documentation), repository characteristics (language, size, architecture), or domains.

Subjective analysis: While we collect quantitative metrics, much of the analysis relies on qualitative interpretation of agent behavior. Different researchers might draw different conclusions.

No variable isolation: Agents differ in multiple dimensions simultaneously (model, prompt, tools, architecture). We cannot make causal claims about which specific factors drive observed differences.

Rapid ecosystem evolution: Coding agents and their retrieval mechanisms evolve quickly. Findings reflect the state of tools at the time of experimentation and may become outdated.

These limitations are acceptable for an exploratory study designed to inform future rigorous evaluation. This study provides a foundational understanding; future quantitative benchmark development will address these limitations through controlled experimentation and statistical rigor.

4. Analysis

This section analyzes the search techniques and retrieval strategies employed by different coding agents in our exploratory study. We examine each agent’s approach to code search, focusing on general techniques applicable to code retrieval rather than task-specific implementation details. The section concludes with comparative analysis of resource consumption patterns and architectural trade-offs. Detailed execution traces and task-specific findings are provided in the appendices.

4.1. Claude Code

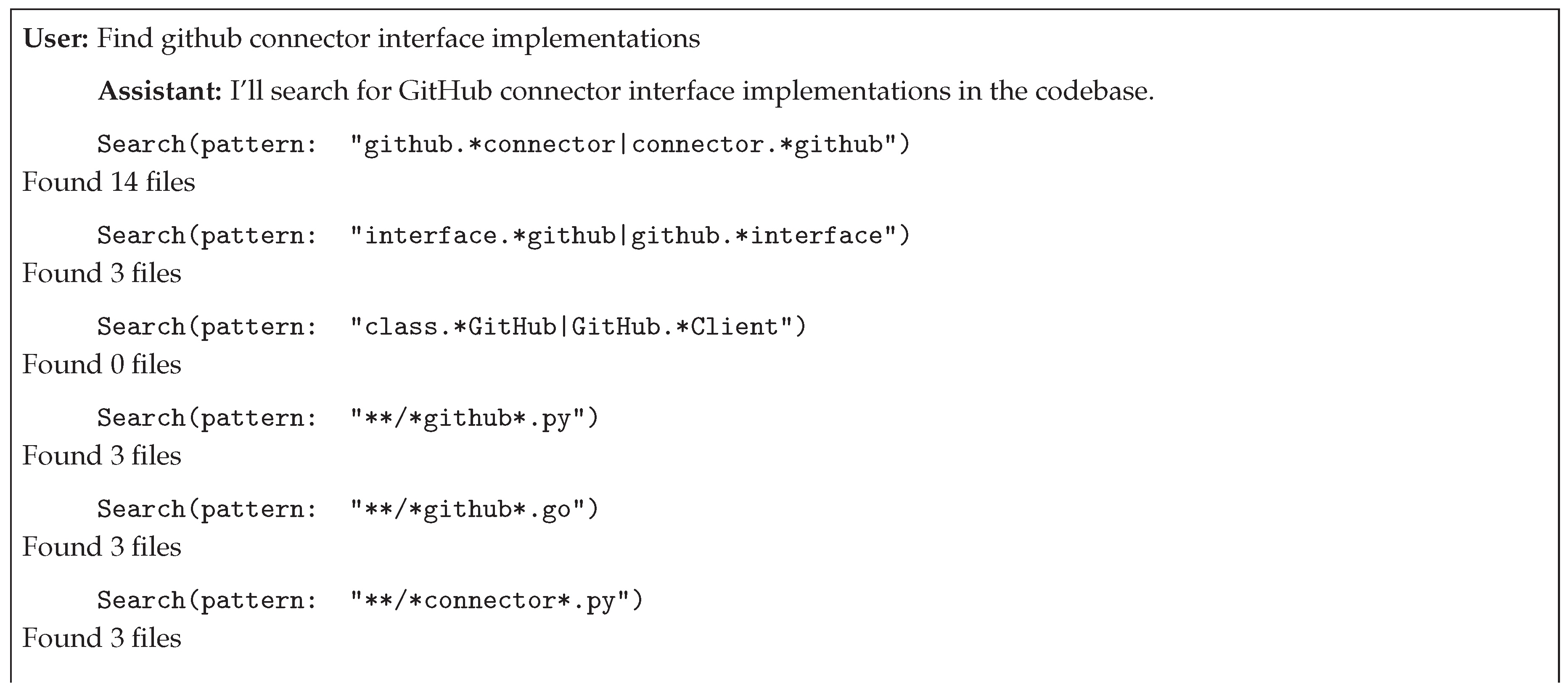

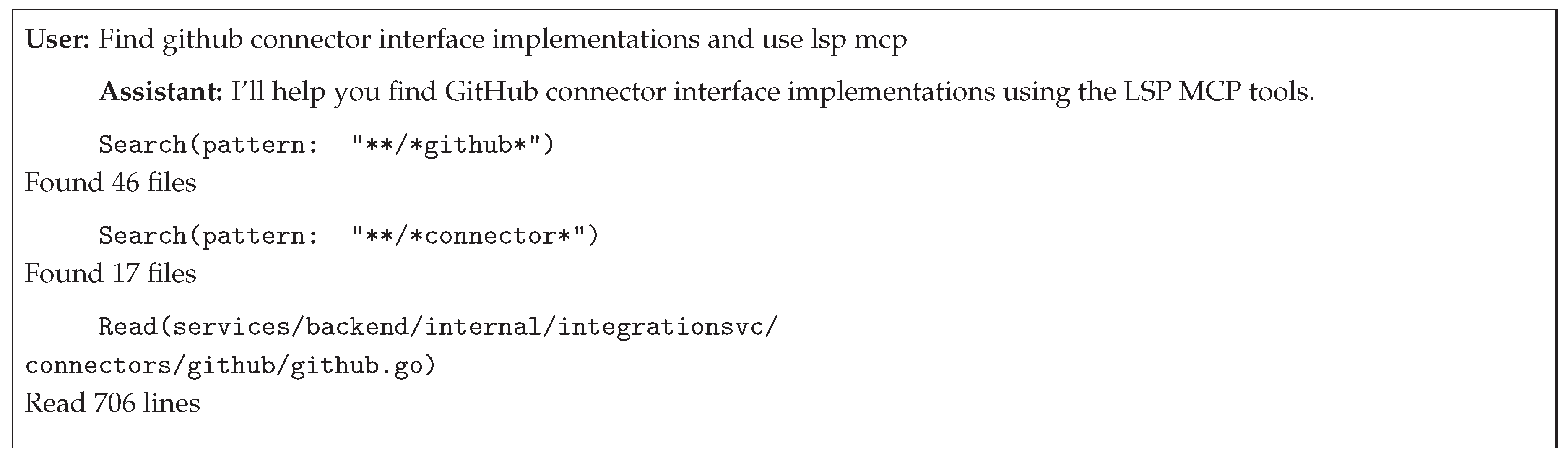

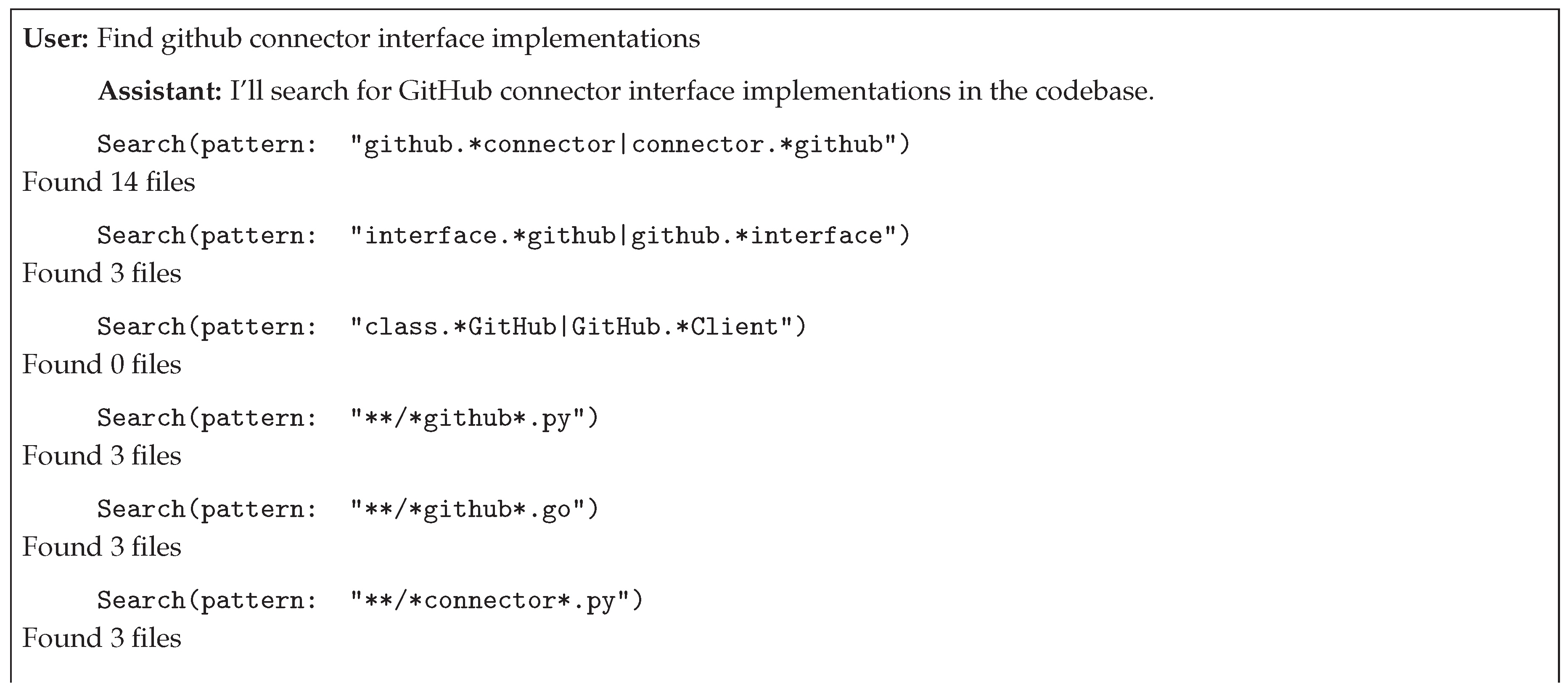

Claude Code employs lexical pattern matching with iterative refinement as its primary search strategy. The agent’s approach demonstrates a three-phase progression from broad discovery to targeted validation, applicable to general code retrieval tasks.

Multi-stage refinement strategy. The search process follows a systematic narrowing pattern:

Broad discovery phase: Initial pattern-based searches cast a wide net using general keywords to identify candidate locations across the codebase

Progressive refinement: Iterative narrowing of search scope through more specific patterns and filters, reducing candidate sets from broad matches to focused targets

Targeted examination: Selective file reading of high-confidence candidates to extract and validate findings

This strategy leverages complementary search primitives: content-based pattern matching using regex (grep search) and file-structure navigation (glob search). The approach enables systematic exploration from general to specific without requiring pre-indexed semantic embeddings or background processing.

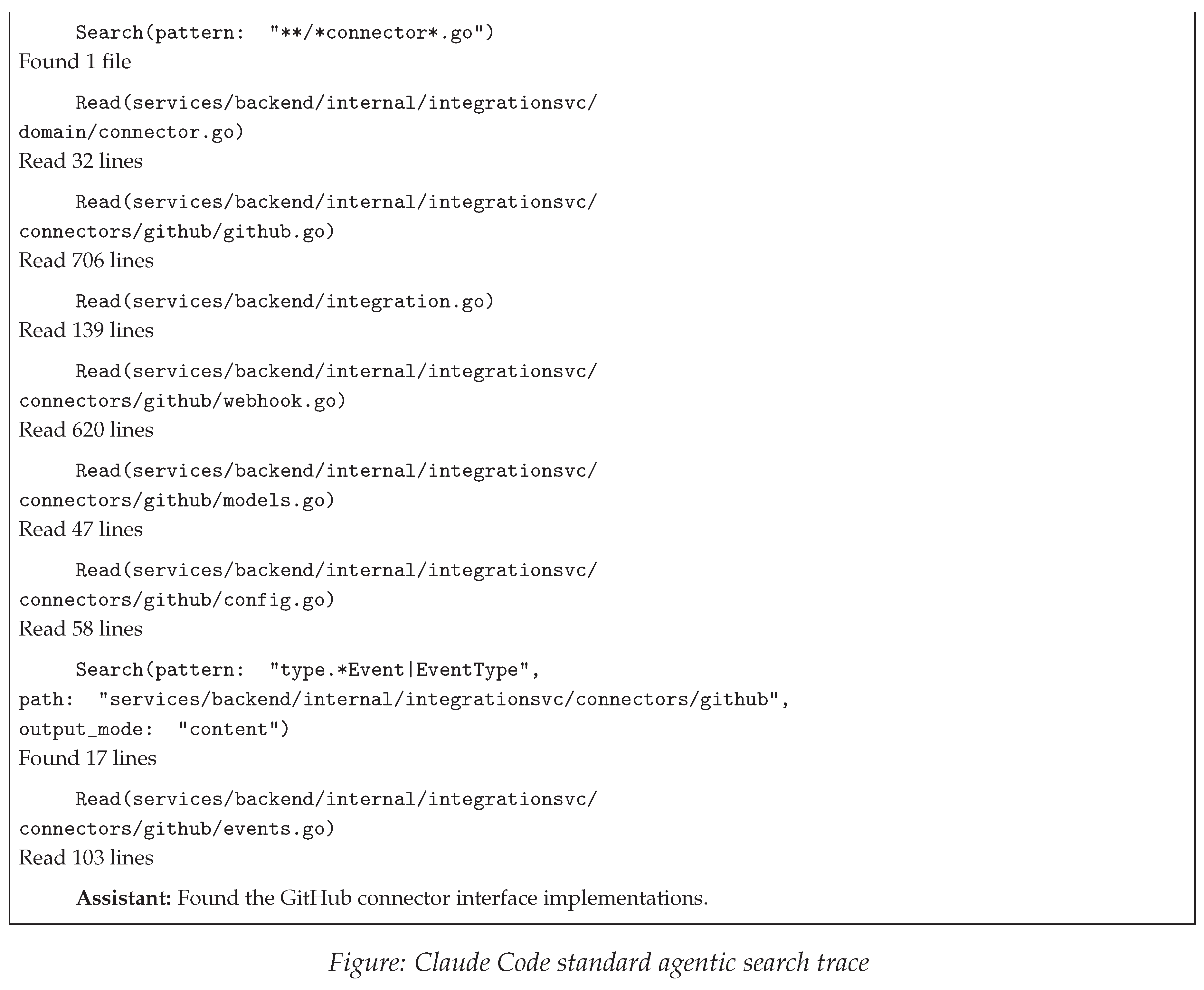

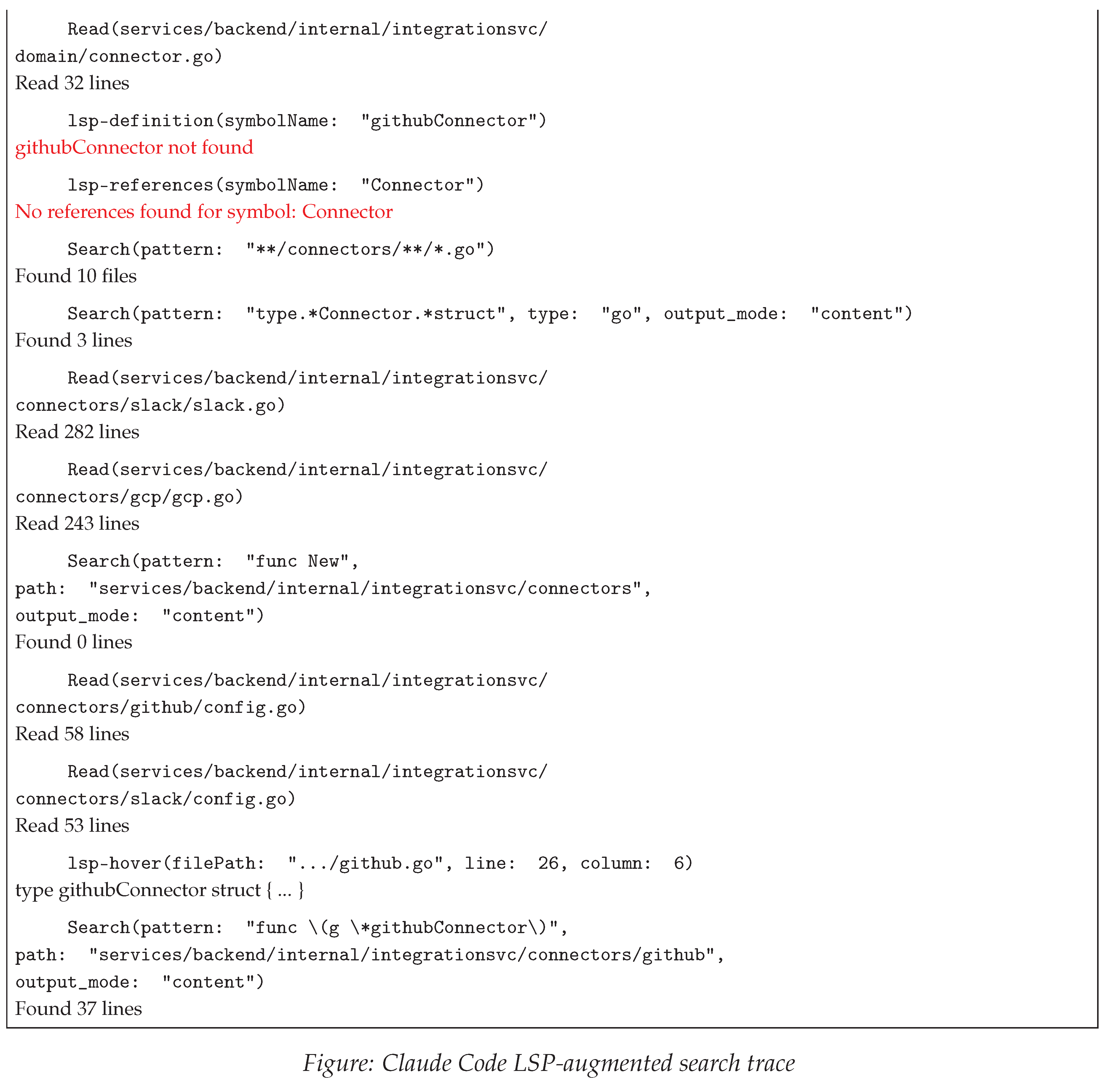

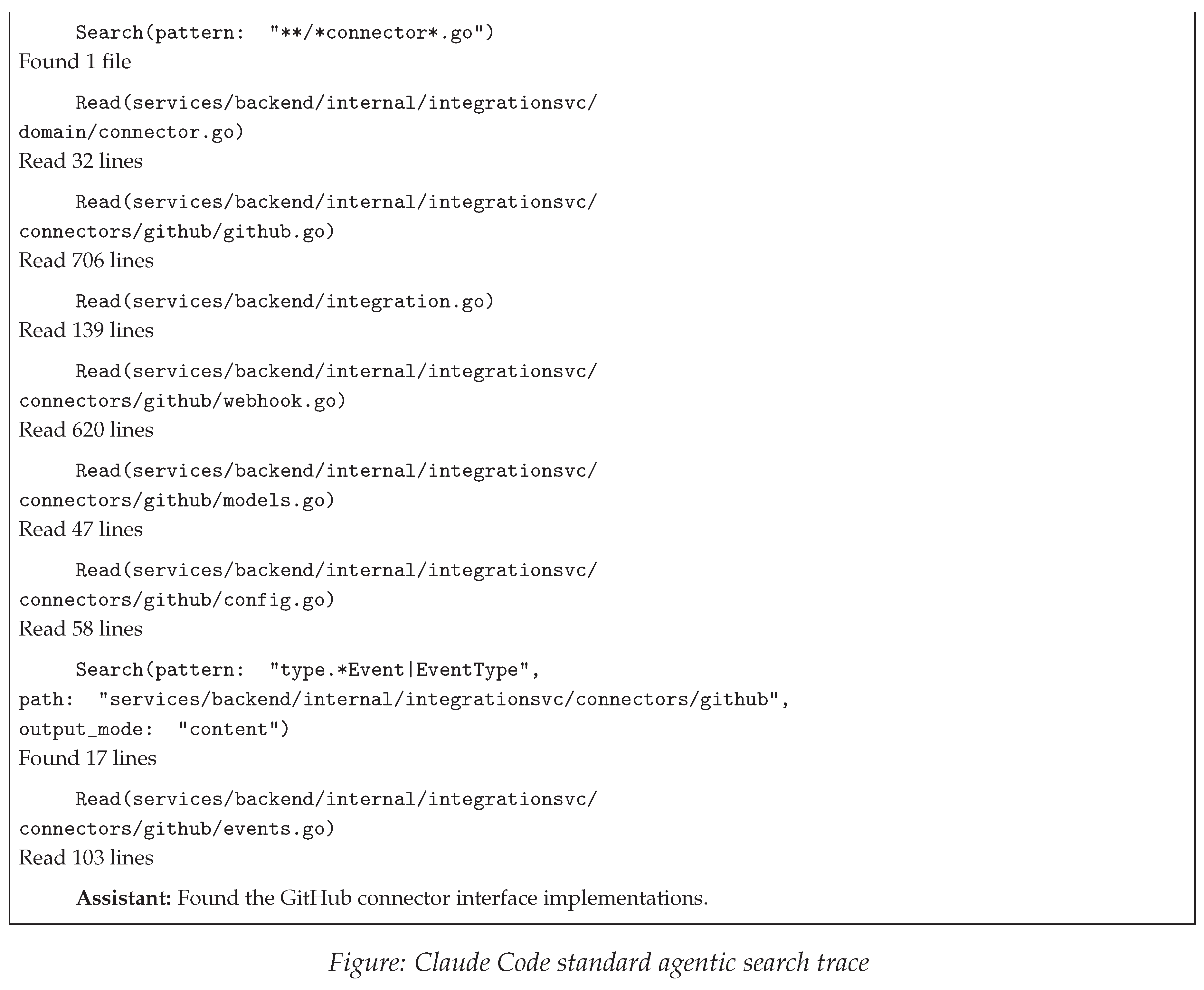

LSP integration experiment. An alternative approach attempted to augment lexical search with Language Server Protocol capabilities through MCP integration. The experiment revealed practical limitations of IDE-oriented tools for autonomous agents. LSP operations (symbol lookup, reference finding, and type information queries) frequently failed due to coordinate precision requirements and unexported symbol handling. The agent fell back to traditional lexical search for task completion, suggesting that tools designed for interactive human workflows may not transfer directly to autonomous operation without significant adaptation.

Architecture characteristics. Claude Code relies on agentic search, employing a tool-first architecture centered on transparent lexical search [

38]. The retrieval mechanism combines pattern matching (grep search), file discovery (glob search), and direct file access, with optional shell command orchestration for complex operations. A key architectural choice is whole-file reading: when accessing files, the agent retrieves entire file contents rather than targeted snippets, contributing to higher token consumption but ensuring complete context availability. The architecture enables sub-agent delegation for multi-step searches through specialized task invocation upon user prompt.

The system prioritizes transparency and tool availability over token efficiency: all search operations, patterns, and file accesses are visible to users, enabling verification of retrieval logic. This contrasts with opaque semantic indexing where relevance scoring and document ranking occur in background systems. The comprehensive tool inventory (system tools + optional MCP integration [

42]) consumes approximately 25.5k tokens (12.7% of context) before any retrieval operations begin, reflecting a design trade-off favoring rich functionality and interpretability. Optional LSP server augmentation [

41] is supported, though lexical tools proved more reliable for autonomous operation in our evaluation.

4.2. Codex CLI

Similar to Claude Code, Codex CLI employs an iterative refinement strategy combining broad keyword discovery with progressive pattern specialization. The search approach demonstrates systematic narrowing through multiple refinement cycles, characteristic of human developer exploration patterns.

Search technique. The agent follows a three-phase exploration pattern:

Broad keyword searches to identify initial candidate sets,

Pattern-based refinement using regex to reduce candidates through structural constraints, and

Targeted file reading with connector-specific validation. The approach leverages negative evidence, where searches returning zero results inform architectural understanding and guide subsequent query formulation. Progressive pattern specificity enables spatial reasoning about codebase organization, narrowing from general terms to type-specific constructs.

The strategy demonstrates effective use of lexical search without pre-indexed embeddings, validating agentic pattern matching for code retrieval tasks.

Architecture characteristics. Codex [

34] employs fuzzy file search as its primary retrieval mechanism, distinct from semantic indexing approaches. The implementation uses scoring systems that reward prefix matches, contiguous character sequences, and spatial proximity in filenames. File system traversal respects repository conventions (gitignore rules) while supporting parallel search. The architecture delegates contextual understanding to LLM reasoning rather than implementing sophisticated pre-processing or indexing, prioritizing simplicity and transparency.

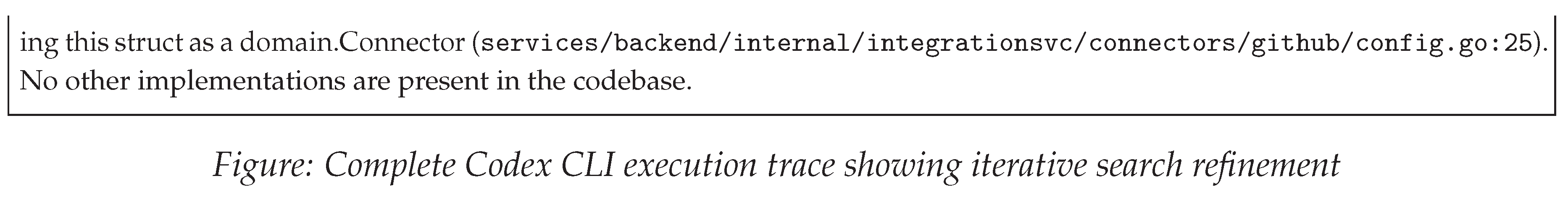

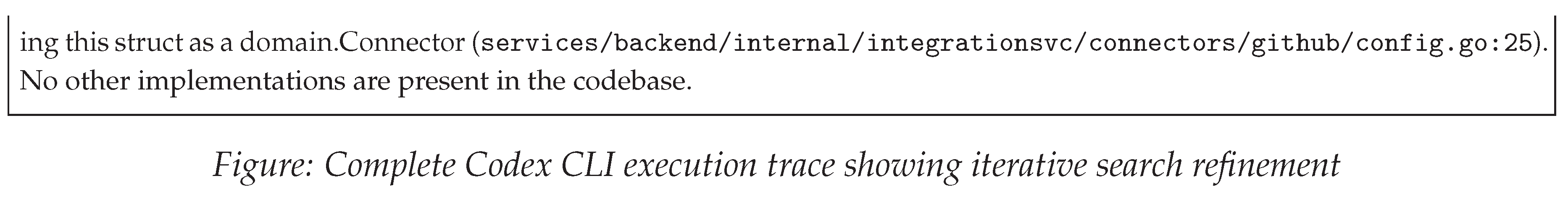

4.3. Gemini CLI

Similar to Claude Code, Gemini CLI employs an iterative agentic search strategy combining file discovery, content search, and cross-referencing. The approach demonstrates systematic orchestration of complementary search operations with batch optimization.

Search technique. The agent coordinates four distinct search patterns:

Broad file pattern discovery using glob-based matching to identify candidate locations,

Structural file location using targeted patterns to discover definitions,

Parallel batch file reading to efficiently gather context from multiple sources, and

Cross-reference searches to identify usage patterns and implementations.

The strategy demonstrates intelligent sequencing: locating definitions before searching for implementations, and using discovered context to inform subsequent queries.

Notable characteristics include batch optimization (reading multiple files per operation), strategic glob pattern usage for targeted discovery, and cross-referencing techniques where initial findings guide subsequent searches. The approach leverages caching mechanisms to reduce redundant operations while maintaining search effectiveness.

Gemini CLI demonstrates effective tool orchestration for agentic search, successfully completing retrieval tasks without semantic indexing through systematic operation sequencing.

Architecture characteristics. Gemini CLI [

35] combines multiple retrieval layers: file discovery with adaptive caching, fuzzy search with algorithm selection based on codebase size, and content search with fallback strategies. The system employs batch file operations for parallel reading and multi-level caching to optimize repeated operations.

A distinctive feature is the specialized Codebase Investigator Agent: a sub-agent with autonomous exploration capabilities using dedicated search tools. This architectural pattern delegates complex investigation tasks to focused agents with constrained operation windows, maintaining investigation state through scratchpads and generating structured reports. Unlike semantic search systems relying on embeddings, the architecture depends on traditional file operations optimized for speed, with intelligence emerging from LLM-driven orchestration.

4.4. Cursor

Cursor employs a hybrid retrieval strategy combining semantic and lexical search tools [

40]. The Cursor documentation lists distinct search capabilities: a "Codebase" tool for semantic searches against pre-indexed embeddings, and a "Grep" tool for exact keyword matching [

40]. Background indexing creates embeddings for each file in the workspace, with indexing time ranging from 1-15 minutes depending on project size [

40].

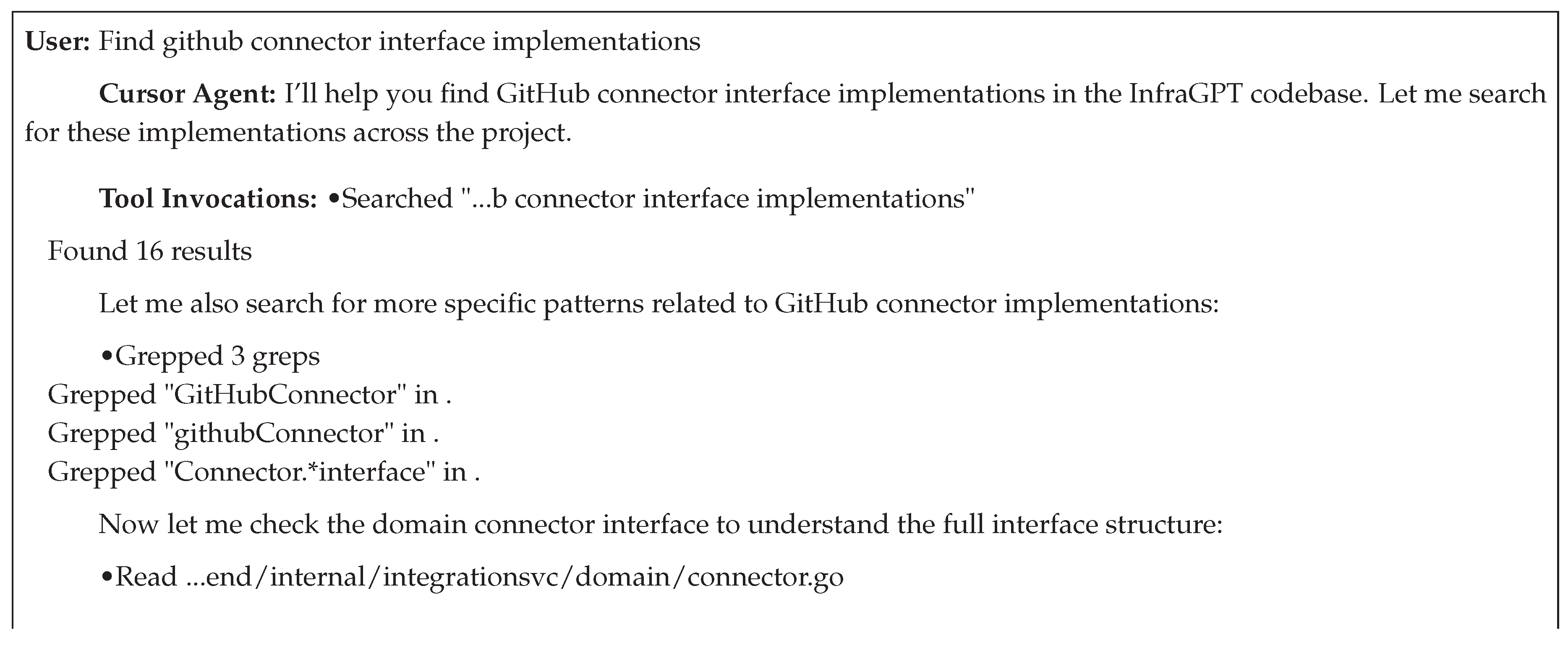

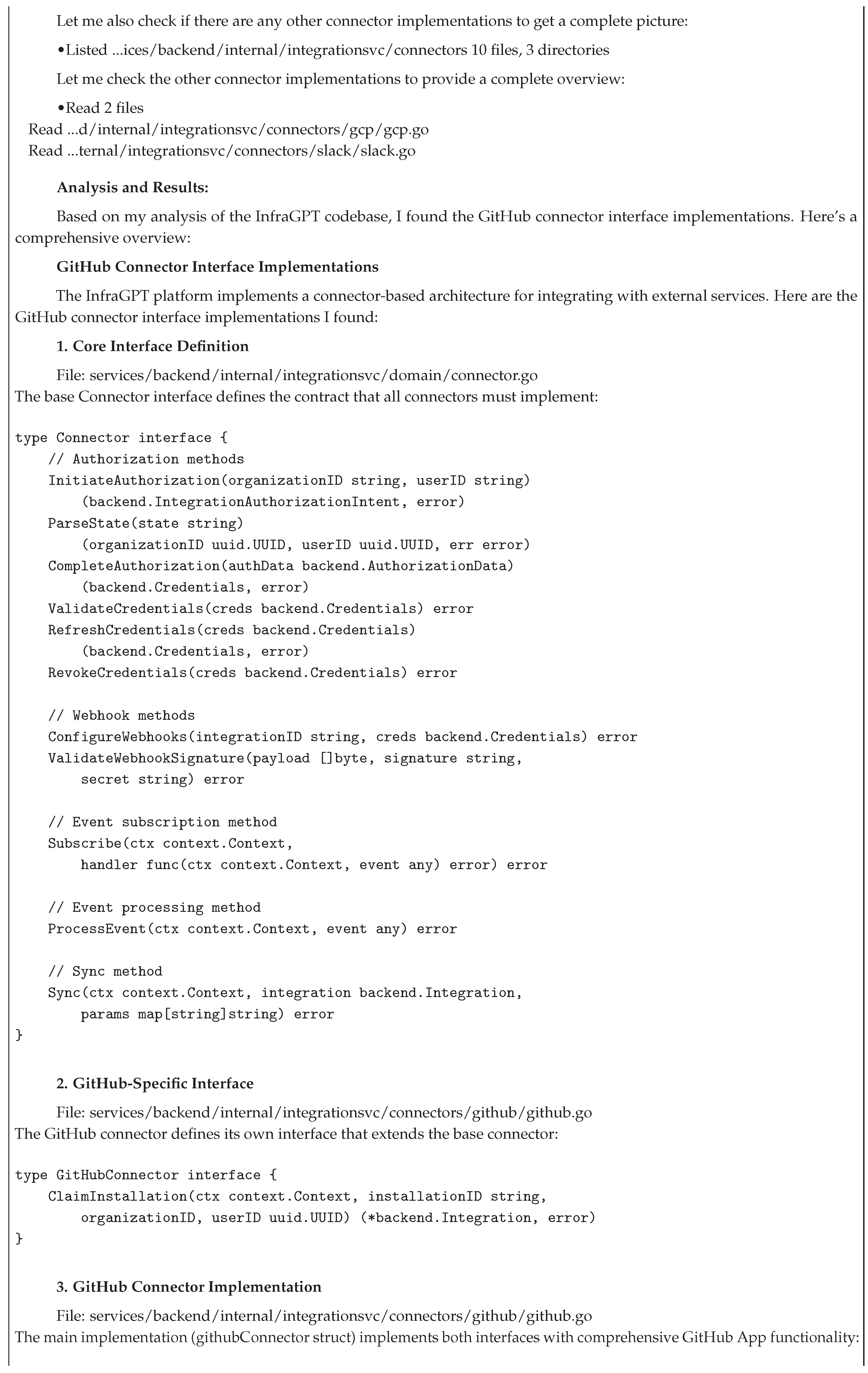

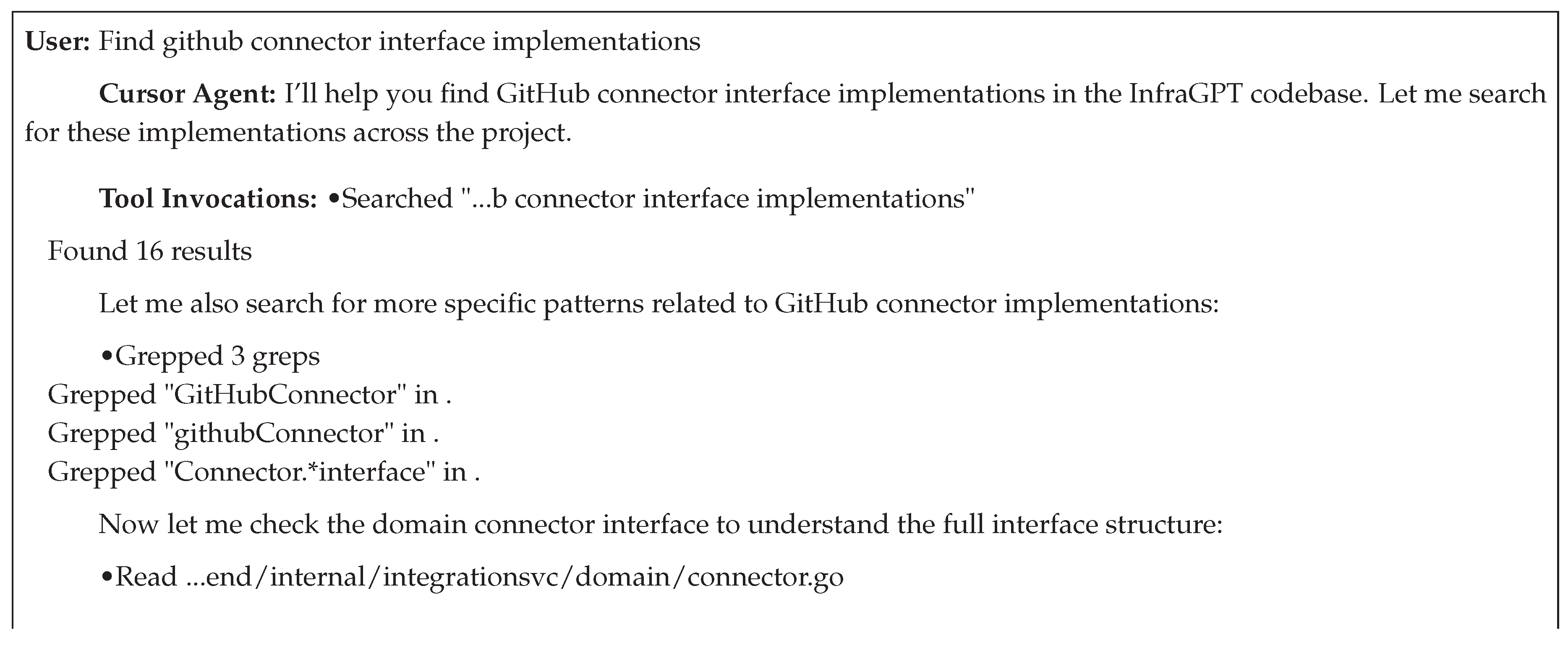

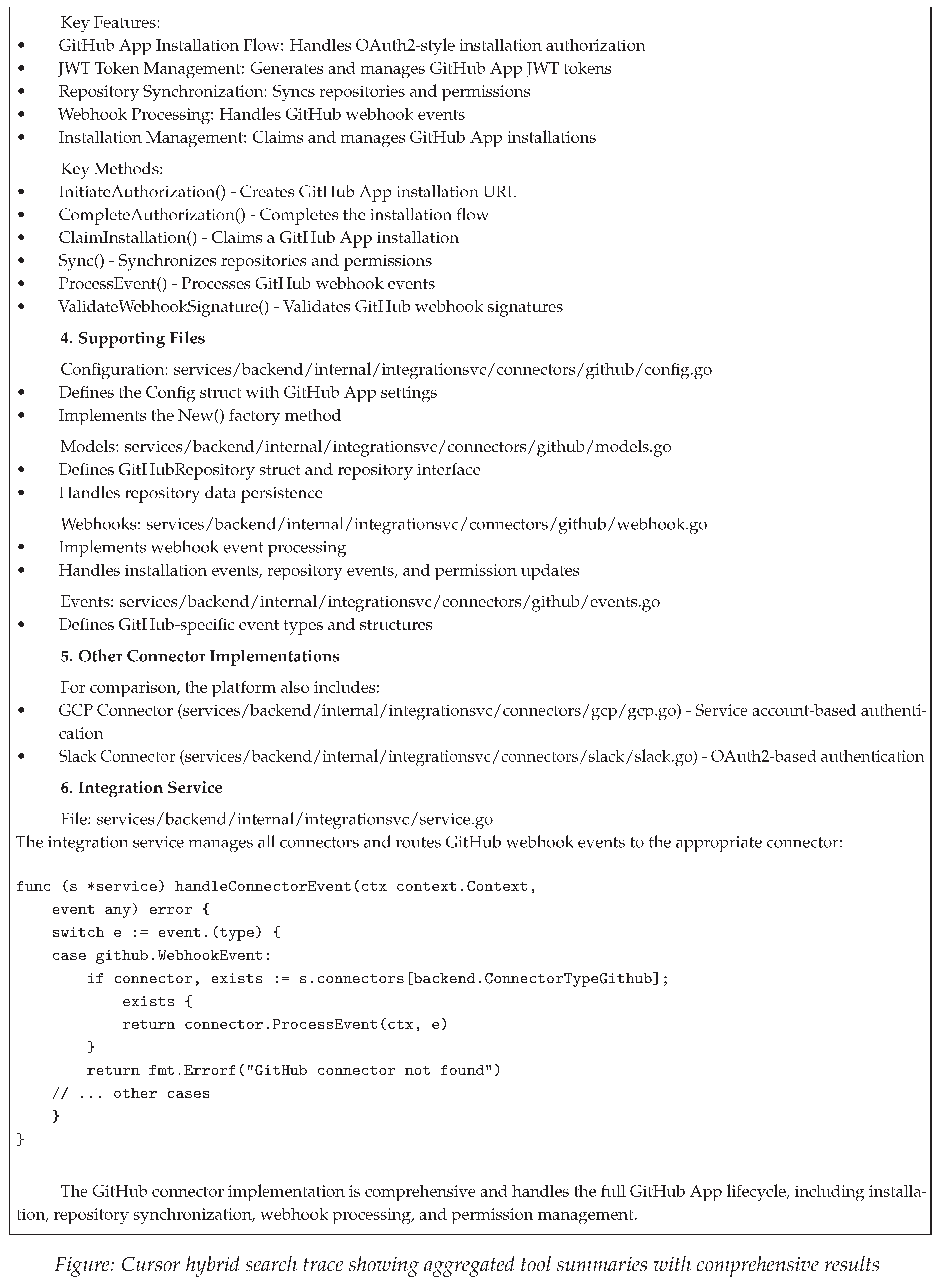

Search technique. The retrieval strategy combines both search approaches within a single query execution: (1) semantic search using the Codebase tool queries pre-indexed embeddings to find conceptually related code, (2) lexical search using the Grep tool targets exact keyword patterns for precision matching, (3) file reading and directory listing tools retrieve specific content from identified files. The observed trace demonstrates this hybrid approach: initial semantic search identified candidate files, followed by targeted grep patterns to locate specific implementations, culminating in selective file reads.

The dual-search architecture enables queries without requiring users to specify regex patterns or file paths explicitly. However, search tool invocations are visible only at a high level (e.g., "Searched ’...b connector interface’", "Grepped 3 greps"). The specific embedding matches, similarity scores, or grep patterns used are not exposed in the interface. This provides partial transparency: users observe that search operations occurred and which tool categories were used, but not the detailed retrieval logic or ranking heuristics.

Architecture characteristics. Cursor integrates search capabilities within an IDE environment, operating through background processes and agent-managed tools [

40]. The Codebase tool requires prior indexing of workspace files (excluding those in .gitignore or .cursorignore), while Grep operates directly on file contents without preprocessing requirements [

40]. Search tools execute automatically based on agent decisions. Users issue natural language queries and observe aggregated tool usage ("Found 16 results"), but do not control which search method is applied or when the agent switches between semantic and lexical approaches.

The agent also includes tools for file operations (Read File, List Directory), command execution (Terminal), and web search [

40], providing broader context gathering capabilities beyond code retrieval. The architecture prioritizes automatic tool selection and aggregated result presentation, trading fine-grained search control for natural language query interfaces and simplified developer interaction.

4.5. Amp

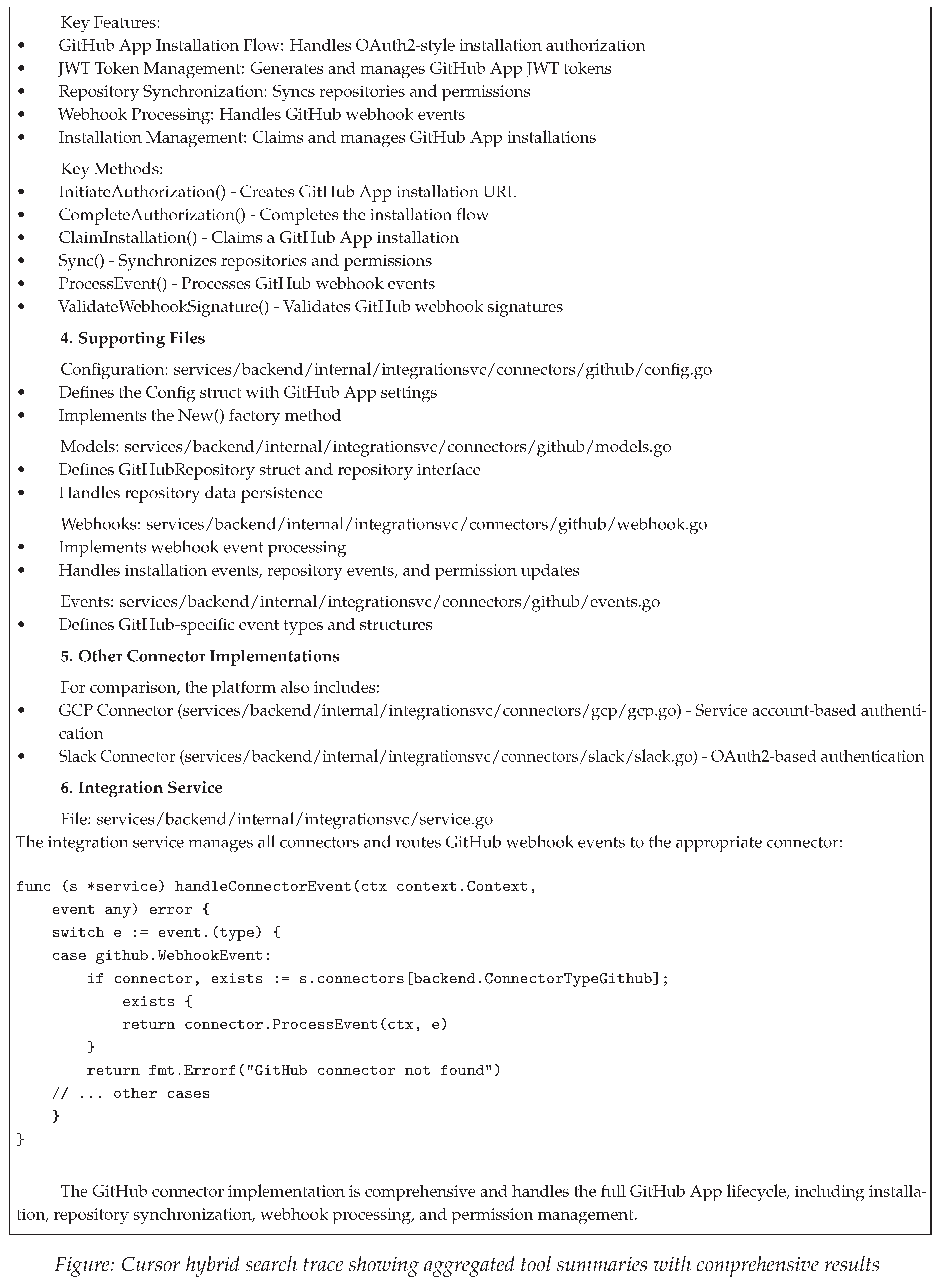

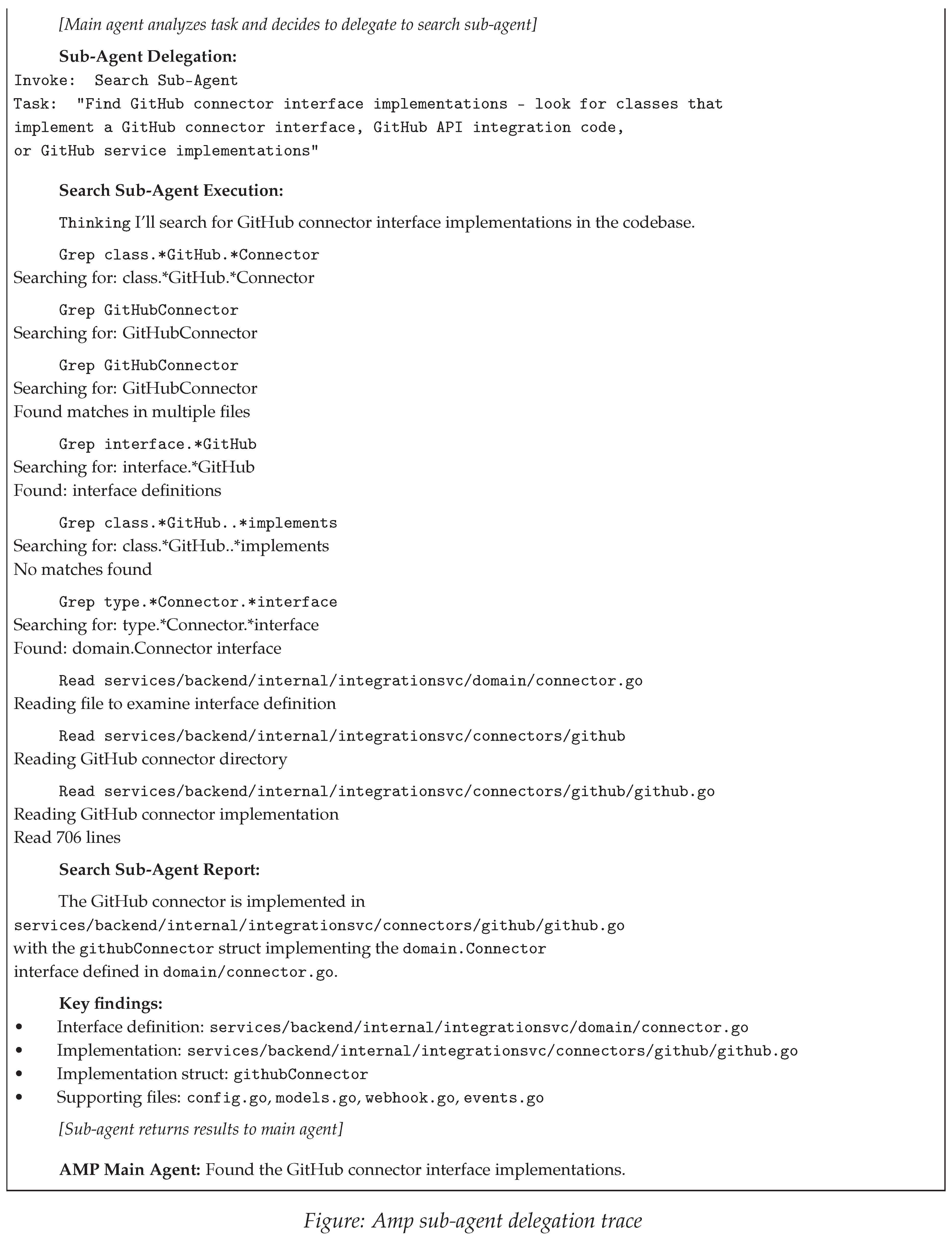

Amp employs a specialized sub-agent architecture for code search, delegating exploration tasks to dedicated search agents rather than executing searches directly. The approach demonstrates explicit task decomposition with clear boundaries between coordination and execution.

Search technique. The system uses a two-layer delegation model: the main agent identifies retrieval needs and invokes specialized search sub-agents with isolated contexts and tool access. Search sub-agents perform systematic exploration using lexical pattern matching, file discovery through glob patterns, and targeted file reading. The sub-agent compiles findings into structured results before returning control, enabling clear separation between search execution and result synthesis.

The execution demonstrates progressive refinement within the sub-agent context: broad initial searches narrowing to targeted pattern matching and validation. Notable characteristics include transparent tool execution through detailed logging, context isolation preventing pollution between agents, and structured result marshaling for information transfer.

Architecture characteristics. Amp [

39] implements multi-agent orchestration where specialized sub-agents handle specific task domains. The architecture comprises a main agent for task decomposition and result synthesis, and specialized sub-agents with dedicated tool access for code exploration. Unlike monolithic agents where a single LLM performs all operations, Amp uses explicit delegation with independent context windows per sub-agent.

The architecture enables parallel sub-agent execution for independent tasks and supports modularity through focused prompting: search agents receive retrieval-specific instructions independent of main task prompts. The system allows user-guided context through configuration files specifying relevant code locations, providing hybrid automatic-manual curation. Context isolation prevents contamination but requires careful engineering for effective information transfer between agents.

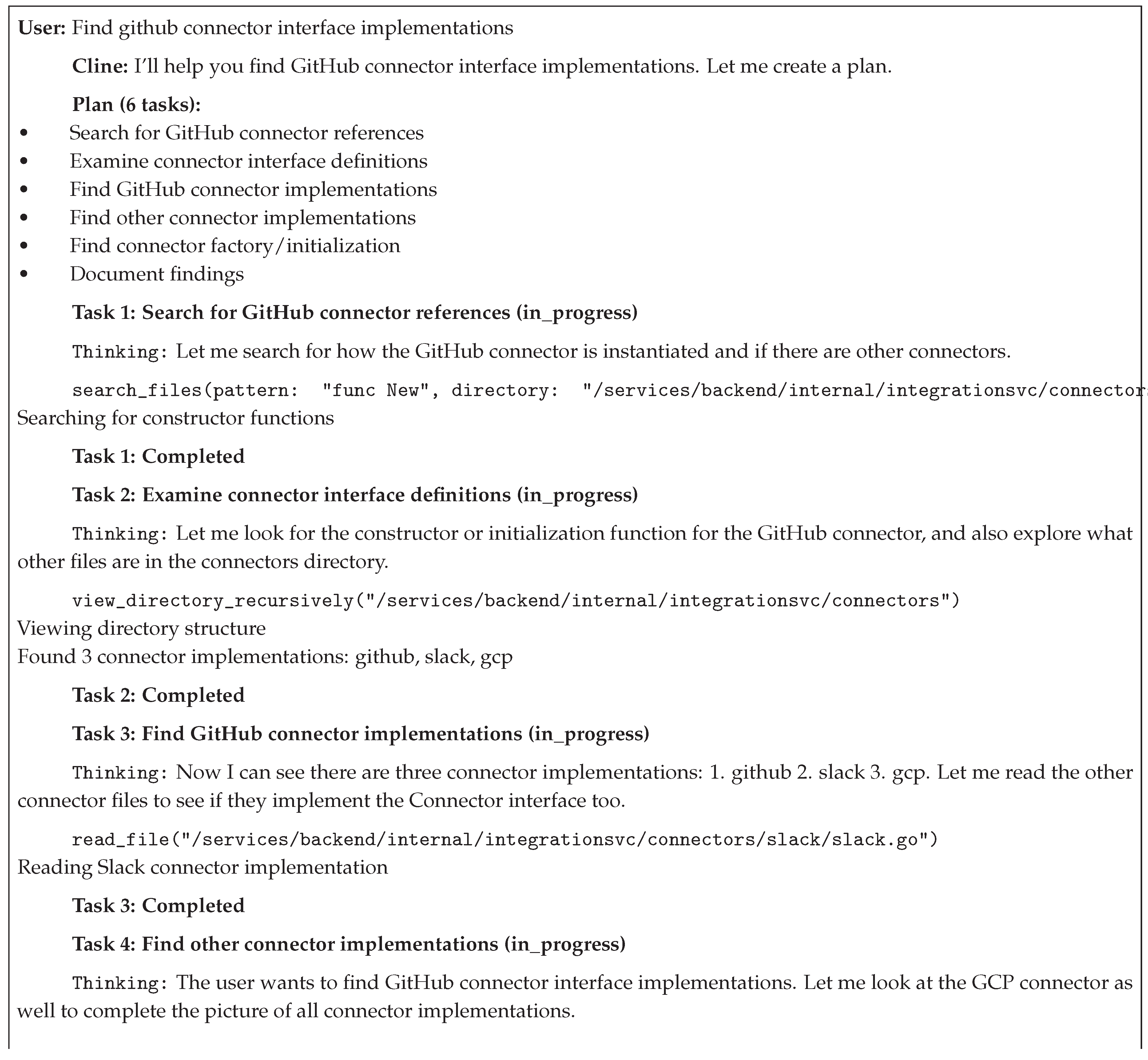

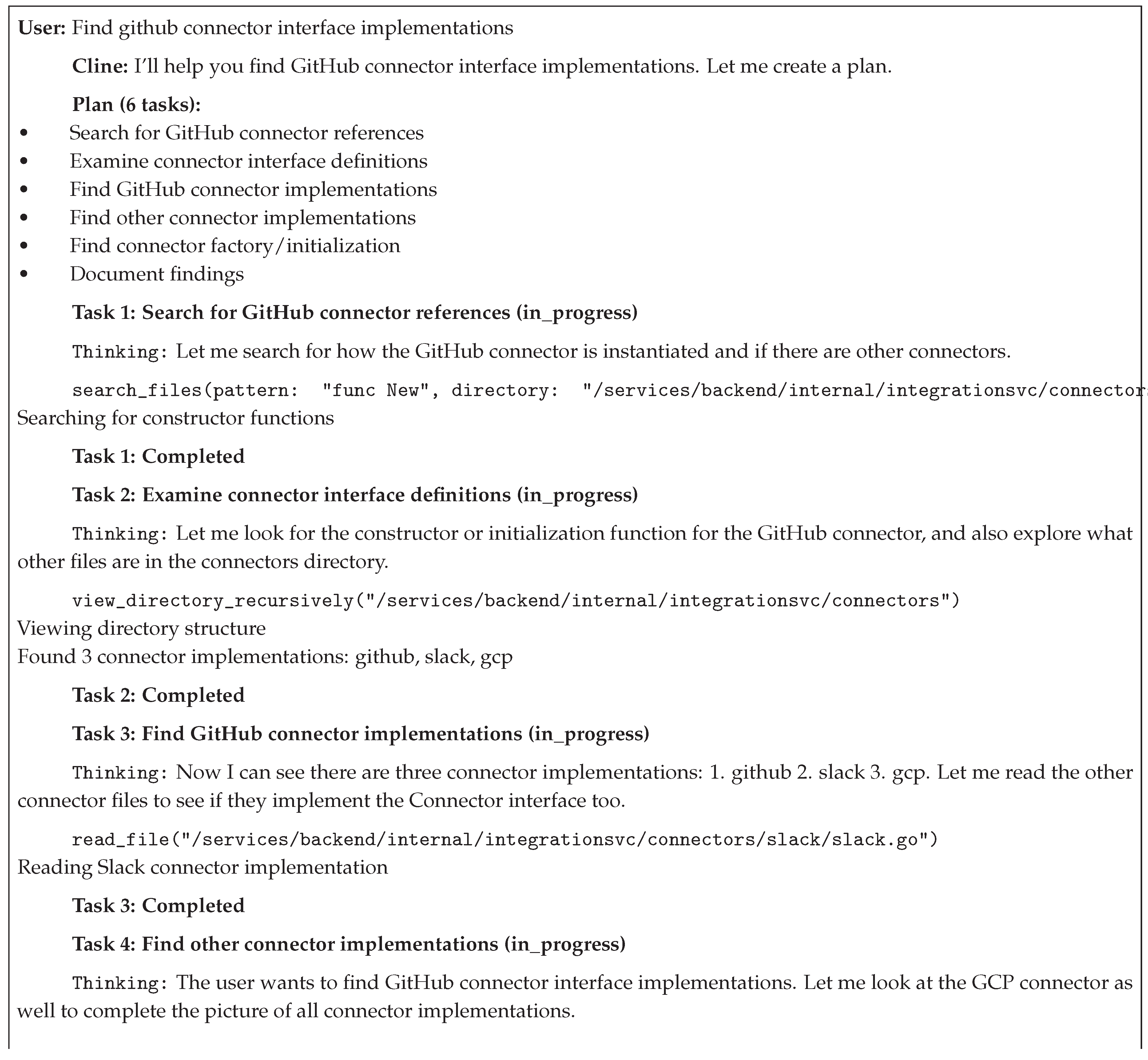

4.6. Cline

Cline employs a hybrid search strategy combining three complementary retrieval mechanisms: content-based pattern matching, fuzzy file path matching, and AST-based code structure extraction. The approach demonstrates multi-granularity search across different code representation levels.

Search technique. The agent orchestrates three distinct search layers through a plan-and-act loop: (1) ripgrep-based content search for keyword pattern matching across file contents, (2) directory-scoped structural exploration using recursive traversal to build spatial codebase awareness, and (3) AST-based definition extraction for syntactic code structure discovery. The strategy demonstrates progressive refinement from broad patterns to specific signatures, with cross-referencing across multiple implementations to understand common patterns.

Notable characteristics include systematic directory traversal for spatial reasoning, multi-implementation cross-referencing to infer architectural patterns, and transparent tool execution with visible search operations. The combination of content search (keyword matching), file name search (fuzzy matching), and structure search (AST parsing) enables exploration across different granularity levels: from broad keyword matches to precise symbol definitions.

Architecture characteristics. Cline [

36] implements a three-tier retrieval system: regex-based content search using ripgrep with result limits and output caps, fuzzy file/folder search combining file listing with fzf [

43] matching and custom scoring, and AST-based definition extraction using Tree-sitter parsers for multi-language syntactic analysis. The architecture supports multi-workspace operation, permission control through ignore files, and performance optimization via result limiting and parallel searching.

The system prioritizes context-aware search by weighting currently open files in results and implements multi-language support through Tree-sitter grammars. Unlike semantic indexing, the architecture relies on lexical search and syntactic parsing optimized for speed, with intelligence emerging from LLM-driven orchestration rather than vector embeddings.

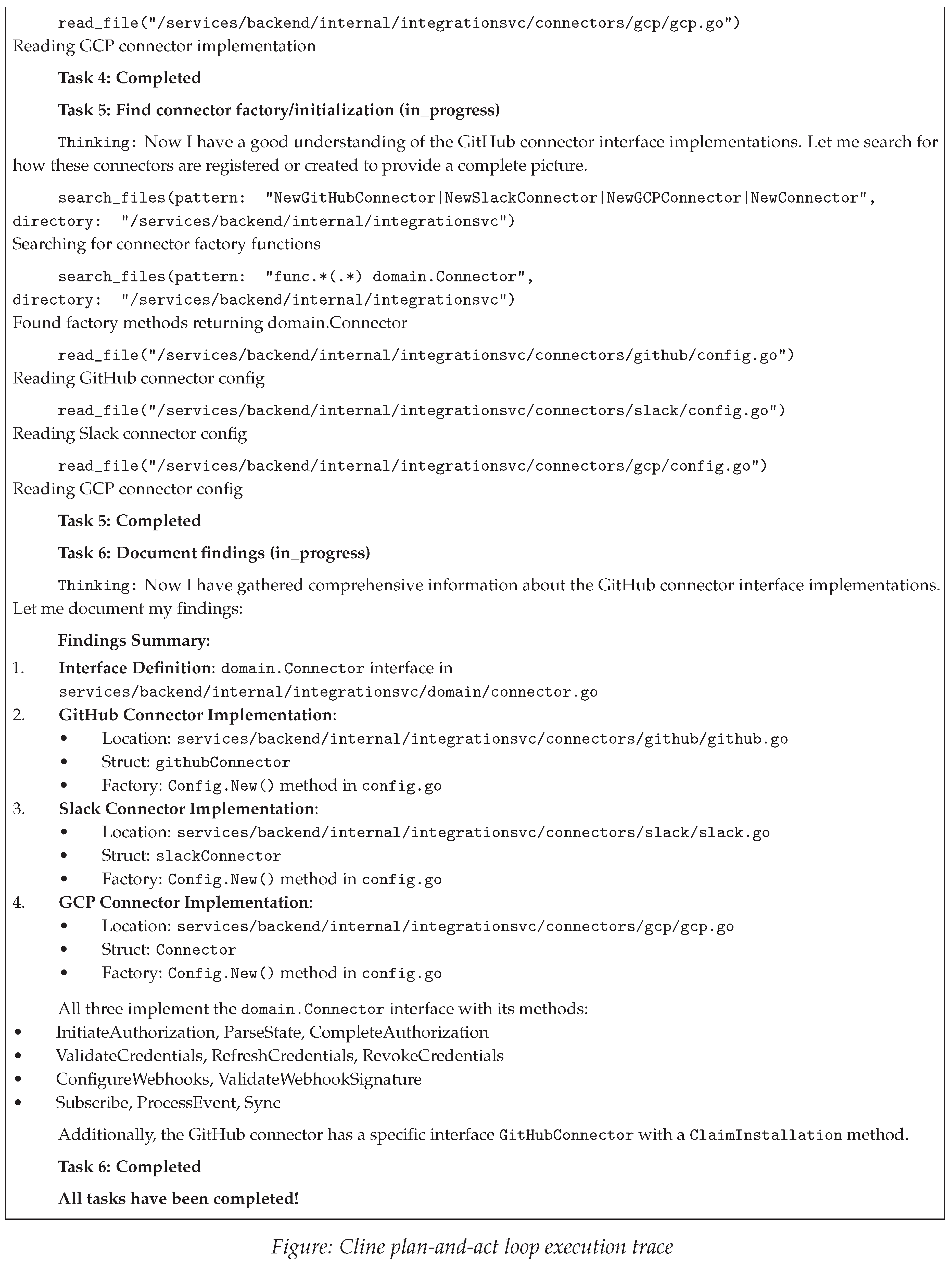

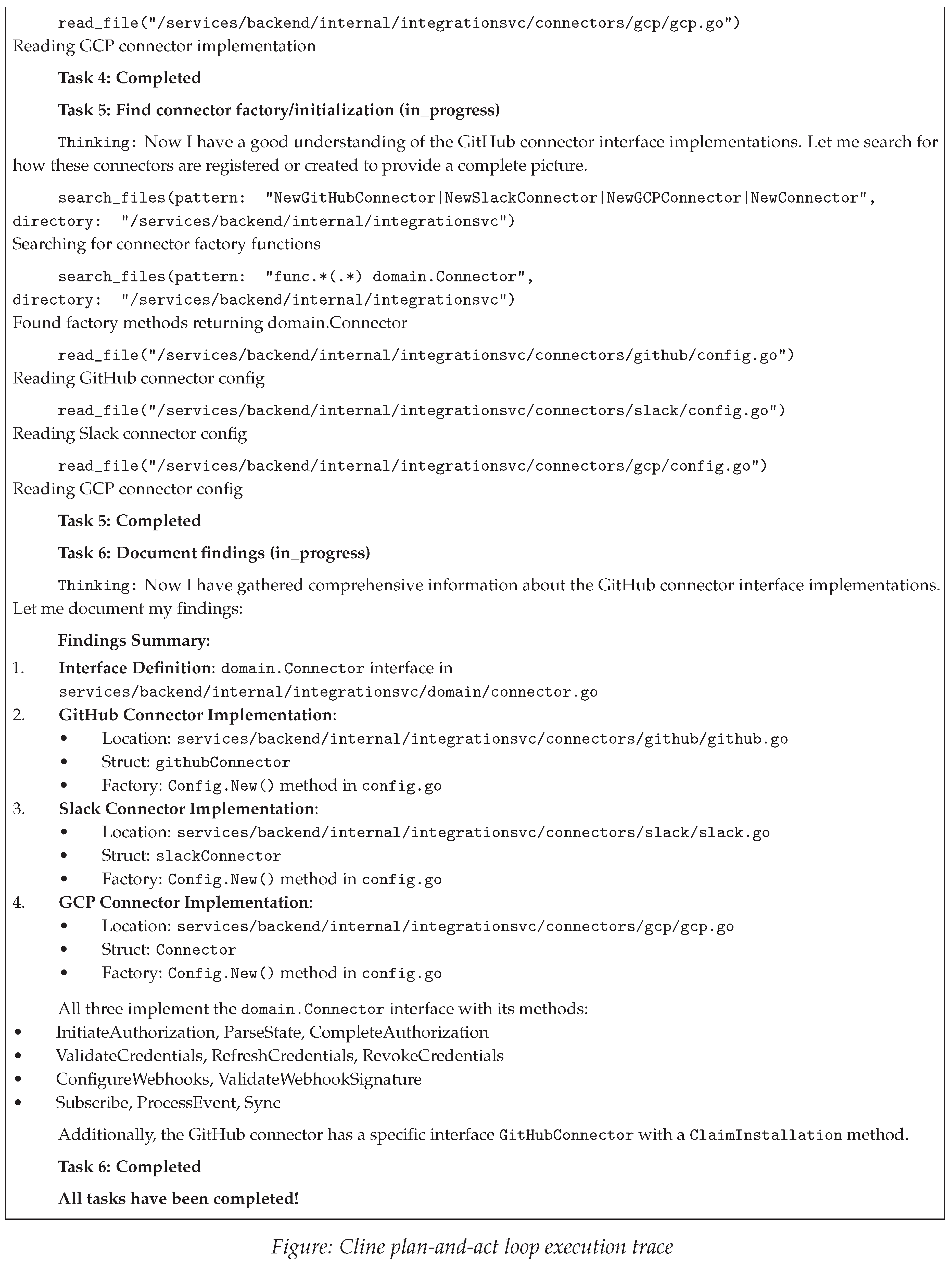

4.7. Aider

Aider employs graph-based AST-driven retrieval fundamentally distinct from both embedding-based semantic search and iterative lexical exploration. The approach combines static analysis techniques inspired by Language Server Protocol with graph topology algorithms to identify relevant code through structural relationships.

Search technique. The retrieval strategy operates through graph-based ranking rather than pattern matching or vector similarity: (1) repo-map construction using Tree-sitter AST parsing to extract definitions and references across the codebase, (2) dependency graph building where nodes represent files and edges represent reference relationships, and (3) PageRank [

44] ranking to identify high-relevance files based on graph centrality. The repo-map provides symbol-level visibility: function signatures and dependency edges without requiring full file content, enabling precise file identification from initial queries.

Notable characteristics include dependency-aware discovery through graph traversal, interface completeness analysis via AST-based structural comparison, and cached parsing to avoid redundant processing. The approach achieves symbol-level visibility within constrained token budgets through binary search optimization, maximizing information density of repository maps. Unlike semantic approaches relying on conceptual similarity, relevance derives from structural relationships (function calls, imports, inheritance). Unlike iterative lexical search, the graph-based approach provides upfront ranking of file relevance.

Architecture characteristics. Aider [

37] implements a four-layer system combining Tree-sitter AST parsing for definition/reference extraction across 40+ languages, NetworkX [

45] graph analysis with PageRank [

44] ranking using personalization factors for context weighting, token-optimized repository maps using binary search to fit symbols within configurable budgets, and disk-based caching with modification-time tracking to avoid redundant parsing.

The architecture emphasizes graph topology over semantics: relevance determined by structural relationships (function calls, imports, inheritance) rather than embedding similarity. The approach is lightweight and deterministic, requiring no GPU, embedding models, or vector databases, while operating offline without external dependencies. Unlike RAG-based systems chunking code into isolated fragments, the graph-based approach preserves architectural context through explicit dependency edges. The repo-map provides symbol-level visibility with function signatures and dependency relationships without full file retrieval, enabling efficient file identification within constrained token budgets.

4.8. Resource Consumption Analysis

Context window utilization varies significantly across agents, reflecting different trade-offs between retrieval comprehensiveness and efficiency.

Table 2 presents token consumption and context window utilization for each agent during the code search task.

Token consumption varies by more than an order of magnitude (8,500 to 117,000), yet all agents successfully completed the task. This variation reveals distinct efficiency profiles across retrieval strategies:

Highly efficient agents (2–7% utilization): Aider and Amp demonstrate minimal context consumption through graph-based ranking and sub-agent delegation, respectively. Aider’s repo-map approach provides symbol-level visibility without full file retrieval, while Amp’s isolated sub-agent contexts prevent main agent contamination.

Moderate efficiency agents (15–18% utilization): Cursor and Cline occupy a middle range through hybrid semantic-lexical indexing (Cursor) and hybrid three-tier search (Cline). These approaches balance retrieval comprehensiveness with context constraints.

Higher-consumption agents (51–70% utilization): Gemini, Claude Code, and Codex demonstrate substantial context usage, though for different reasons. Gemini’s batch file operations consume 51.1% of context. Claude Code’s consumption (54–58.5%) stems primarily from architectural choices: tool inventory overhead ( 12.7% of context consumed by system and MCP tool definitions before any operations), whole-file reading rather than snippet-based retrieval, and autocompact buffer allocation (22.5% of context reserved for conversation history). Codex CLI’s actual consumption reaches 70.2% when cached tokens are included, though its interface misleadingly displays only 14.5% based on non-cached tokens—a significant discrepancy that can cause users to underestimate context pressure by nearly 5x.

The LSP-augmented Claude Code variant (58.5%) consumed 8.5% more context than the standard approach (54%) without measurable performance improvement, suggesting IDE-oriented tools add overhead for autonomous agents. Notably, Amp’s 968k context window substantially larger than other agents, enabled 2% utilization despite absolute token consumption similar to Cline.

These patterns suggest significant optimization opportunities exist in current retrieval approaches. Graph-based ranking (Aider) and architectural isolation (Amp) achieve task completion with minimal context, while iterative lexical search may over-provision context through redundant exploration.

4.9. Comparison of Code Search Tools in Coding Agents

Different coding agents employ varying approaches to code retrieval and search.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive comparison of popular coding agents, analyzing their primary retrieval mechanisms, architectural paradigms, context provisioning methods, key strengths, and noted limitations.

Table 3.

Comparison of Code Search and Retrieval Mechanisms in Coding Agents.

Table 3.

Comparison of Code Search and Retrieval Mechanisms in Coding Agents.

| Agent |

Primary Retrieval Mechanism |

Architectural Paradigm |

Context Provisioning |

Key Strengths |

Noted Limitations |

| Claude Code |

Agentic Search (grep) |

CLI-Native |

Explicit tools + Bash |

Predictability and simplicity |

High token consumption, potential for irrelevant context |

| Gemini CLI |

Agentic Search (grep) |

CLI-Native |

Explicit tools + Bash |

Parallel tool calls, fastest retrieval |

High token consumption |

| Codex CLI |

Shell Command Orchestration |

CLI-Native |

Explicit tools + Bash |

Progressive search, directory scoped pattern search |

Highest token consumption, incorrect token usage reporting |

| Cursor |

Hybrid Semantic-Lexical (Embeddings + Grep) |

IDE-Integrated (Hybrid CLI) |

Background indexing and Explicit tools |

Whole-codebase awareness, fast interactive queries |

Partial transparency (aggregated tool summaries), initial indexing overhead |

| Cline |

Hybrid Agentic Search (ripgrep + fzf + Tree-sitter AST) |

IDE-Integrated (VS Code) |

Explicit (plan-and-act loop) |

Three-tier retrieval (lexical + fuzzy + AST), multi-language AST parsing, efficient context usage (35k tokens) |

Limited AST depth (top-level only), 300 result limit, relies on effective agent planning |

| Aider CLI |

Graph-Based AST Ranking (Tree-sitter + PageRank) |

CLI-Native |

Repo-map with symbol-level visibility |

Graph topology preserves architecture, PageRank relevance scoring, deterministic offline operation, 40+ languages, lowest token usage (8.5k-13k), symbol signatures visible without full file retrieval |

Indexing overhead |

| Amp |

Multi-Agent Orchestration (Sub-Agent Delegation) |

CLI-Native |

Hybrid (explicit sub-agent + agentic search) |

Modularity, parallel sub-agent execution, specialized prompting, efficient token usage ( 19k, 2% of 968k context) |

Context isolation complexity, requires careful result marshaling |

This comparison reveals several key insights about retrieval strategy evolution in coding agents. CLI-native agents like Claude Code, Gemini CLI, and Codex CLI prioritize transparency and predictability through explicit search commands: developers can understand and verify. These approaches mirror traditional developer workflows but vary significantly in resource efficiency (see

Table 2).

IDE-integrated solutions split into two paradigms: Cursor leverages hybrid semantic-lexical indexing to provide whole-codebase awareness with moderate efficiency (14.7% context utilization), though this comes at the cost of partial transparency (aggregated tool summaries) and initial setup overhead. Cline employs a three-tier retrieval approach (ripgrep lexical search, fzf fuzzy matching, Tree-sitter AST parsing) with a plan-and-act loop, achieving high transparency and similar efficiency (17.5% utilization) while maintaining structural code awareness.

Aider represents a distinct paradigm combining graph-based static analysis with symbol-level repository maps. The approach achieves the highest efficiency (4.3–6.5% utilization) while preserving architectural context through dependency graphs. This LSP-inspired approach eschews semantic embeddings entirely, relying instead on structural relationships to rank file relevance. The repo-map provides function signatures and dependency edges without requiring full file retrieval, enabling precise file identification from initial queries. The trade-off is no semantic understanding: files with conceptual similarity but no explicit dependencies won’t be connected. However, it gains deterministic, explainable retrieval that works offline without GPU or embedding model dependencies.

Multi-agent architectures like Amp balance modularity and specialization through sub-agent delegation while maintaining exceptional efficiency (2% of its larger 968k context window).

The choice of retrieval mechanism significantly impacts agent effectiveness, with each approach optimized for different use cases and developer preferences. As the field evolves and models get adapted to use different retrieval strategies, we observe trends toward hybrid systems that can dynamically adapt retrieval strategies based on task and context requirements.

4.10. Code Search Transparency Comparison

Transparency in code search refers to user visibility into retrieval operations: which queries are executed, which files are retrieved, and how long this information remains observable. This dimension affects agent debuggability, user trust, and the ability to verify retrieval correctness.

Table 4 compares search transparency across agents.

Query Visibility indicates whether users can observe the actual search patterns (grep regex, file globs, or semantic queries).

File Visibility indicates whether retrieved file lists are exposed.

Duration describes information persistence.

CLI-native agentic agents (Claude Code, Gemini CLI) provide full transparency: all search patterns, regex details, and file retrievals are persistently visible in execution traces. Codex CLI and Cline show partial query visibility: Codex displays search terms and scope ("Search GitHubConnector", "Search mock in integrationsvc") without underlying fuzzy-search scoring details; Cline exposes lexical search patterns (ripgrep invocations) but hides semantic retrieval and AST traversal details. Cursor provides partial transparency across both dimensions: semantic searches show truncated queries ("Searched ’...b connector interface’"), grep patterns are fully visible ("Grepped ’GitHubConnector’"), but auto-retrieved files from semantic indexing remain unlisted. Aider provides minimal transparency, displaying only file addition notifications ("Added file.go to chat") without exposing search operations or query details. Amp uniquely combines full transparency during sub-agent execution with transient persistence: detailed search operations are visible while the sub-agent operates but removed from the main thread upon completion, typically visible for under one second.

These transparency patterns reflect architectural trade-offs between verifiability and interface simplicity. Full transparency enables debugging and trust calibration but increases information density, while abstracted summaries reduce cognitive load at the cost of observability into retrieval logic.

5. Results

This section presents findings from the exploratory study, addressing the three research questions through comparative analysis of agent performance on the code retrieval task. All seven agents (Claude Code, Codex CLI, Gemini CLI, Cursor, Amp, Cline, and Aider) successfully completed the task of locating GitHub connector interface implementations in the InfraGPT repository, enabling comparison of their retrieval approaches, resource consumption, and observable behaviors.

5.1. RQ1: Semantic Search vs. Lexical Search

The study compared one hybrid semantic-lexical agent (Cursor) against six lexical/agentic search agents (Claude Code, Codex CLI, Gemini CLI, Cline, Amp, and Aider).

Token consumption. Cursor consumed approximately 29,400 tokens (14.7% of its 200k context window). Lexical search agents showed varied consumption: Claude Code (108k–117k tokens, 54–59%), Codex CLI (39.5k tokens, 34.4k input + 5k output with 151k cached), Gemini CLI (102k tokens with 52.1% cache hit rate), Cline (35k tokens, 17.5%), Amp (19k tokens, 2% of 968k window), and Aider (8.5–13k tokens). Note that prompt caching reduces computation cost and API charges but does not reduce context window consumption: cached tokens still occupy context space. Aider’s graph-based AST ranking achieved the lowest token consumption, while Cursor’s hybrid approach fell in the middle range.

Task completion. All agents successfully identified the GitHub connector interface and its implementations, indicating that both semantic and lexical approaches are viable for this task type. Task completion alone did not differentiate the approaches.

Retrieval transparency. Lexical search agents provided visible tool execution traces (grep patterns, file reads, search refinements), enabling users to observe and verify retrieval logic. Cursor’s hybrid retrieval provided partial transparency: tool invocations were visible at an aggregated level ("Searched", "Grepped 3 greps") with result counts, but specific search patterns, embedding matches, file rankings, and relevance scores remained hidden.

Contextual breadth. Cursor demonstrated whole-codebase awareness through semantic indexing, cross-referencing the GitHub connector with other implementations (GCP, Slack) and presenting architectural context without explicit searches. Lexical agents achieved similar architectural understanding through iterative exploration and cross-file reading, but required multiple explicit tool invocations.

Setup requirements. Cursor required background indexing before query execution, introducing initial overhead. Lexical agents operated without pre-indexing, enabling immediate task execution at the cost of potentially higher query-time token consumption.

No clear performance advantage emerged for semantic search in this single-task exploratory study. Both approaches successfully completed the retrieval task, with trade-offs in transparency, token efficiency, setup overhead, and contextual awareness. Lexical search provided greater interpretability and required no indexing infrastructure, while semantic search enabled broader context gathering with less explicit tool orchestration.

5.2. RQ2: Human Developer Tools for Agents

Claude Code’s LSP integration experiment provided direct evidence on whether agents benefit from IDE-level developer tools.

LSP integration attempt. Claude Code attempted to use Language Server Protocol tools via MCP integration, invoking lsp-definition for "githubConnector" symbol lookup, lsp-references for "Connector" interface usage, and lsp-hover for type information. These LSP queries largely failed: "githubConnector not found" (symbol resolution failed for unexported types), "No references found for symbol: Connector" (workspace-wide searches returned empty), and hover information required precise file coordinates that were difficult to specify without prior knowledge.

Fallback to lexical search. Despite LSP tool availability, the agent achieved task completion primarily through traditional grep-based searches and file reading. The LSP-augmented run consumed 117k tokens (59% context usage) with 8 searches and 8 file reads, compared to 108k tokens (54%) with 7 searches and 6 file reads for the standard grep-only approach. LSP integration added tool invocations and token consumption without measurable retrieval improvement.

Aider’s adapted approach. Aider demonstrated an alternative strategy: rather than using LSP directly, it employed LSP-inspired techniques adapted for autonomous workflows. The agent used Tree-sitter AST parsing with NetworkX PageRank to build dependency graphs, achieving symbol-level visibility and architectural awareness without interactive LSP queries. This approach consumed 8.5–13k tokens (the lowest among all agents) and successfully identified interface implementations, missing methods, and dependency relationships through static analysis.

The findings suggest that LSP, designed for interactive human workflows with IDE integration, does not translate directly to autonomous agent performance. Symbol resolution failures, empty reference searches, and coordinate-precision requirements created friction for agent-driven exploration. However, the underlying principles of LSP (structural code understanding, dependency tracking, symbol resolution) proved valuable when adapted for autonomous operation (as demonstrated by Aider’s graph-based AST approach). Human-centric tooling requires adaptation for agent contexts rather than direct adoption.

5.3. RQ3: Specialized Retrieval Sub-Agents

Two agents employed multi-agent architectures with specialized retrieval delegation (Amp and Gemini CLI), enabling comparison with single-agent approaches.

Token efficiency. Amp’s sub-agent architecture consumed approximately 19k tokens (2% of its 968k context window), achieving the second-lowest token consumption among all agents. Gemini CLI consumed 102k tokens with 52.1% cache hit rate. Single-agent approaches showed varied efficiency: Aider (8.5–13k tokens, lowest overall), Cline (35k tokens), Codex (39.5k tokens displayed, but 191k actual including cached tokens—70.2% of 272k context), and Claude Code (108–117k tokens).

Architectural characteristics. Amp employed explicit sub-agent delegation: the main agent identified the need for code search and spawned a dedicated search sub-agent with isolated context and tool access. The sub-agent performed grep searches, glob patterns, and file reads independently, then returned structured results to the main agent. Gemini CLI used a "Codebase Investigator Agent" with autonomous exploration capabilities, investigation scratchpads, and structured XML reports (maximum 15 turns, 5-minute timeout). Both approaches successfully completed the task.

Coordination overhead. Multi-agent architectures required explicit result marshaling: context from the search sub-agent needed to be serialized and transferred to the main agent’s context. This created communication overhead absent in single-agent systems where retrieval results were immediately available in the same context window.

Modularity benefits. Sub-agent delegation enabled specialized prompting: the search sub-agent received retrieval-specific instructions independent of the main agent’s task-focused prompt. This separation theoretically enables focused optimization of retrieval quality, though performance benefits were not conclusively demonstrated in this single-task study.

The findings indicate that specialized retrieval sub-agents can achieve competitive or superior token efficiency compared to single-agent approaches (Amp’s 19k tokens vs. Cline’s 35k tokens vs. Claude Code’s 108–117k tokens), though Aider’s single-agent graph-based approach achieved the lowest consumption (8.5–13k tokens). Sub-agent architectures introduce modularity and specialization benefits but require careful context management to avoid coordination overhead. Both architectural paradigms successfully completed the task, suggesting the choice depends on factors beyond raw retrieval performance, such as extensibility requirements, prompt engineering flexibility, and context window constraints.

5.4. Cross-Cutting Observations

Several patterns emerged across all agents regardless of retrieval approach:

Iterative refinement. All agents employed progressive search narrowing: broad initial queries (e.g., "github") followed by targeted refinement (e.g., "interface.*github", "type.*Connector"). This pattern appeared in lexical search (grep), semantic search (Cursor’s natural language queries), and graph-based search (Aider’s PageRank-driven file ranking).

Multi-file context synthesis. The task required understanding distributed code across multiple files (interface definition in domain/connector.go, implementation in connectors/github/github.go, configuration in config.go). All agents successfully synthesized this cross-file context, whether through explicit file reading sequences (lexical agents), background indexing (Cursor), or repo-map symbol visibility (Aider).

Tool diversity. Agents employed complementary tools beyond primary retrieval: directory exploration (ls, recursive file viewing), file type filtering (glob patterns), and content extraction (file reading, AST parsing). Effective retrieval combined multiple tool types rather than relying on a single search mechanism.

Resource consumption variability. Token consumption varied by an order of magnitude (8.5k to 117k tokens), yet all agents completed the task successfully. This suggests significant opportunity for optimization: current retrieval approaches may over-provision context or employ inefficient search strategies. Aider’s graph-based approach and Amp’s sub-agent delegation demonstrate that substantial token reductions are achievable without sacrificing task completion.

These findings establish baseline performance for diverse retrieval approaches on a controlled task, revealing trade-offs in transparency, efficiency, setup requirements, and architectural complexity. However, the exploratory nature of this single-task study limits generalizability: findings may not extend to different task types, repository characteristics, or complexity levels. Future quantitative evaluation with controlled variables and diverse tasks is required to establish causal relationships and definitive performance rankings.

6. Limitations

This exploratory study examines retrieval behavior on a single refactoring task within a single repository (InfraGPT, a 50k-line Go/TypeScript/Python monorepo). Several factors limit the generalizability of findings:

Task diversity. The controlled task of locating interface implementations through multi-file code search represents one category of software engineering work. Findings may not extend to other task types such as debugging runtime failures, implementing new features requiring architectural changes, refactoring legacy code with poor documentation, or synthesizing cross-cutting concerns (security, performance, error handling). Different task categories may favor different retrieval mechanisms.

Repository characteristics. InfraGPT’s moderate size (338 files, 50k lines of code), clear architectural boundaries, and well-structured module organization may not reflect challenges in larger-scale repositories (100k+ lines), legacy codebases with inconsistent naming conventions, polyglot repositories with language-specific tooling requirements, or codebases with poor documentation and minimal comments. Retrieval effectiveness likely varies with repository complexity and code quality.

Limited evaluation scope. The study examines seven agents on a single task instance. Statistical significance cannot be established, variability across multiple task instances is not measured, and long-tail failure modes (rare edge cases, non-deterministic errors) are not captured. Token consumption and tool usage patterns observed may not be representative of typical performance.

Confounding variables. Agents differ in multiple dimensions simultaneously, including underlying models (Sonnet-4.5, GPT-5, Gemini-2.5-pro), prompt engineering and system instructions, tool implementations and APIs, context window sizes (200k to 968k tokens), and architectural paradigms (CLI-native vs. IDE-integrated). Observed performance differences cannot be attributed to retrieval mechanisms alone: model reasoning capabilities, prompt quality, and architectural choices confound results.

Qualitative analysis subjectivity. Interpretation of agent behavior, classification of retrieval strategies, and assessment of context relevance rely on manual observation and subjective judgment. Different researchers may categorize tool usage patterns differently or draw alternative conclusions from execution traces.

These limitations are inherent to this exploratory methodology. The study’s value lies in surfacing hypotheses, identifying trade-offs, and informing the design of future rigorous quantitative evaluation with diverse tasks, controlled variables, and statistical analysis. Findings should be interpreted as preliminary insights rather than definitive evidence of retrieval mechanism superiority.

7. Challenges

The code retrieval problem presents fundamental challenges that extend beyond simple search. These challenges span technical, architectural, and evaluation dimensions, each contributing to the complexity of building effective coding agents.

7.1. Retrieval Quality and Context Management

Noise injection and context overflow. Imprecise retrieval introduces irrelevant code that degrades agent performance. Conversely, overly broad retrieval generates contexts that exceed model capacity, forcing truncation or overwhelming the model’s reasoning capabilities. This tension between recall and precision becomes particularly acute in large codebases where relevant code may be scattered across multiple files.

Cross-language variability. Retrieval effectiveness varies significantly across programming languages due to differences in syntax, idioms, and structural patterns. Semantic search approaches trained primarily on Python or JavaScript may perform poorly on languages with different paradigms (e.g., functional languages like Haskell, or systems languages like Rust), requiring language-specific tuning or universal representations that remain elusive.

7.2. Evaluation and Success Criteria

Defining successful retrieval. Unlike traditional information retrieval where relevance can be assessed independently, code retrieval success is task-dependent. Retrieval that includes sufficient context for one task may be insufficient for another. The lack of standardized metrics for "sufficient retrieval" complicates both evaluation and comparison across systems. Furthermore, success often depends on downstream task completion rather than retrieval precision, making isolated retrieval evaluation problematic.

7.3. Architectural and Distributed Challenges