1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence tools are transforming how developers write and maintain code. Platforms like GitHub Copilot [

1] and Cursor [

2] provide convenience by suggesting context-aware code snippets, acting as sophisticated auto-completion tools. However, their capabilities are largely limited to assisting with individual coding tasks, leaving a gap in automating the entire software development lifecycle.

As LLMs [

3,

4] mature, they have the potential to go beyond snippet-level assistance and enable full automation of routine and repetitive tasks. While initial setup may require effort, once established, automated workflows can execute complex, multi-step processes without human intervention. This paper demonstrates how such workflows can streamline even complicated software development workflows, such as refactoring, testing, or code reviews.

2. Related Work

Previous research and commercial tools, such as GitHub Copilot [

1] and Cursor [

2], primarily focus on providing immediate assistance by predicting and suggesting code snippets.

GitHub Copilot is an instrument for code completion and automatic programming, created by GitHub and OpenAI and that integrates with various IDEs, supporting the developer with suggestions for code snippets and auto-completion.

Cursor understands the code, suggests improvements, and can also write pieces of code. It offers AI code completion, error correction, and natural language commands. While it extends its functionality to include features such as in-file navigation and editing, its scope still centers on enhancing individual coding tasks rather than automating comprehensive workflows.

While beneficial, these approaches can overlook larger tasks like:

Refactoring large, complex codebases [

5].

Automating repetitive tasks such as boilerplate code generation for CRUD operations [

6] or DTO (Data Transfer Object) classes [

7].

Implementing multi-step workflows like creating database models, updating service layers, and generating API endpoints.

Conducting automated code reviews to ensure adherence to coding standards and best practices.

Detecting and fixing code smells, such as duplicated code or overly complex methods [

5].

Generating comprehensive unit and integration tests to ensure high code coverage [

8].

Replacing deprecated APIs with modern alternatives.

Addressing security vulnerabilities by identifying and fixing common issues like SQL injection [

9,

10] or hardcoded secrets.

GitHub Copilot has already gained popularity among developers, and it may be regarded as a substitute for human pair programming [

11]. Sometimes it is referred to as the "AI Pair Programmer". An empirical study that collected and analyzed the data from Stack Overflow and GitHub Discussions revealed that the major programming languages used with it are JavaScript and Python, while the main IDE with which it integrates is Visual Studio Code [

12].

A comprehensive analysis of the results of using GitHub Copilot concludes that the code snippets it suggested have the highest correctness score for Java (57%) while JavaScript is the lowest (27%). The complexity of the code suggestions is low, no matter the programming language for which they were provided. Also, the generated code proved to need simplifications in many cases, or it relied on undefined helper methods [

13].

Another metric of large interest is the quality of the code that is generated. According to the assessment from [

14], GitHub Copilot was able to generate valid code with a 91.5% success rate. Examining the code correctness, it was provided 164 problems, resulting in 47 (28.7%) correctly solved, 84 (51.2%) partially correctly solved, and 33 (20.1%) incorrectly solved.

Also, primarily known for its text generation capabilities, LLM can be adapted for NER (Named-Entity Recognition) tasks and be used for entity recognition in border security [

15]. Nature-inspired and bio-intelligent computing paradigms using LLMs have revealed effective and flexible solutions to practical and complex problems [

16].

Generating unit tests is also a crucial task in software development, but many developers tend to avoid it, being tedious and time-consuming. It is therefore an ideal type of task to be delegated to an AI assistant. An empirical study conducted to generate Python tests with the help of GitHub Copilot [

17] assessed the usability of 290 tests generated by GitHub Copilot for 53 sampled tests from open-source projects. The results showed that within an existing test suite, 45.28% of the generated tests were passing, while 54.72% of generated tests were failing, broken, or unusable. If the GitHub Copilot tests are created without an existing test suite in place, 92.45% of the tests are failing, broken, or unusable.

Without a unifying workflow, even with the aid of AI tools, developers must still control every step of the process and perform the integration, testing, refactoring, and merging of generated snippets manually. This reliance on manual oversight and intervention often leads to inconsistencies, errors, and inefficiencies in the development process, limiting the potential productivity gains of AI assistance.

Several attempts were made to automate the entire process of software development, which includes writing, building, testing, executing code, and pushing it to the server. AutoDev [

18] is an AI-driven software development framework for autonomous planning and execution of intricate software engineering tasks. It starts from the definition of complex software engineering objectives, assigned to AI agents that can perform the regular operations on the codebase: file editing, retrieval, building, execution, testing, and pushing.

AlphaCodium [

19] follows a test-based, multi-stage, code-oriented iterative process organized as a flow, using LLMs to address the problems of developing code. Its applicability is mainly for regular code generation tasks, that cover a large part of the time of a developer.

By adopting standardized workflows, developers can leverage AI more effectively to automate these tasks while ensuring that the generated code aligns with project requirements, coding standards, and best practices, reducing the need for constant manual oversight.

3. Foundational Building Blocks of the Workflow

To overcome the limitations of existing AI-assisted coding tools, the research proposes a workflow-centric framework that automates the entire software development lifecycle—from requirements gathering to code generation, testing, and deployment.

The framework’s foundational components are designed to address the key challenges in AI-driven development workflows and ensure seamless integration of AI-generated outputs into existing systems:

Including Files into Prompts – Allows developers to include multiple files or folders in a prompt by specifying paths, ensuring the LLM has the necessary context for accurate code generation.

Automated Response Parsing and File Organization – Once the LLM generates code, it must correctly create the files and place them in the appropriate project directories.

Automatic Rollbacks – If the generated code doesn’t meet expectations, the framework automatically reverts changes, keeping the project consistent and ready for the next update.

Automatic Context Discovery – Analyzes the project structure and dependencies to identify the minimal set of relevant files needed for a prompt, ensuring accuracy while avoiding unnecessary context overload.

These foundational components enable fully automated workflows for AI-driven code generation. The next sections examine each of these in detail.

3.1. Including Files into Prompts

One of the main challenges in AI-assisted development is ensuring that LLMs receive sufficient, relevant, and structured context to generate high-quality code. Current approaches often rely on manual copy-pasting of context, which is not only time-consuming but also error-prone and difficult to replicate.

The framework addresses this issue by introducing an automated method where developers specify the necessary context—such as code, requirements, and documentation—using file or folder paths in a prompt file. This approach ensures that LLMs consistently receive the relevant information required for accurate code generation.

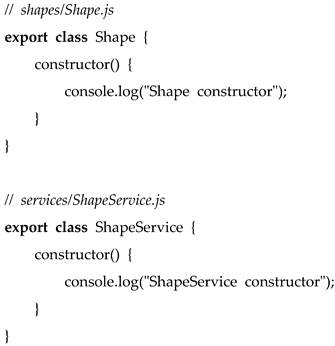

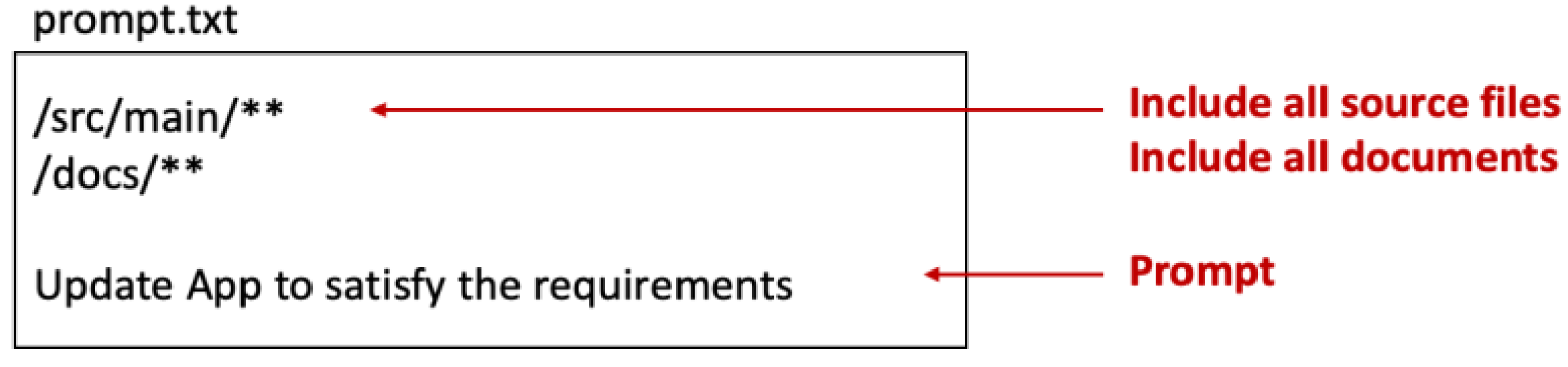

Figure 1 illustrates how necessary context is specified within the prompt.

Additionally, the framework supports wildcard-based inclusion, allowing multiple files or entire folders to be dynamically included.

Figure 2 demonstrates an example where all Java source files and documentation files are referenced using wildcard patterns.

Wildcards streamline the inclusion of necessary files but must be used thoughtfully. Providing excessive context can overwhelm the LLM, leading to irrelevant or suboptimal responses. To maintain efficiency, it is recommended to include only the most relevant files.

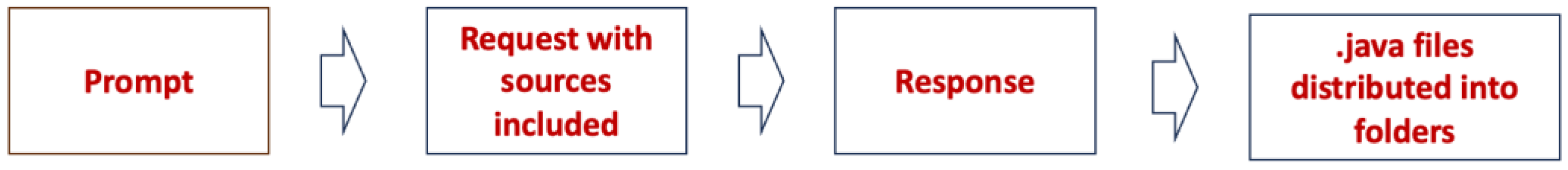

Figure 3 summarizes the full process, from providing context to generating a response.

Finally,

Section 3.4 will explore how the framework further enhances this process with automatic context discovery, which dynamically identifies the files most relevant to the developer’s request, reducing manual effort and improving workflow efficiency.

3.2. Automated Parsing of the Generated Code

Once the LLM generates code, it must be correctly structured within the project. In Java, package declarations naturally determine file placement.

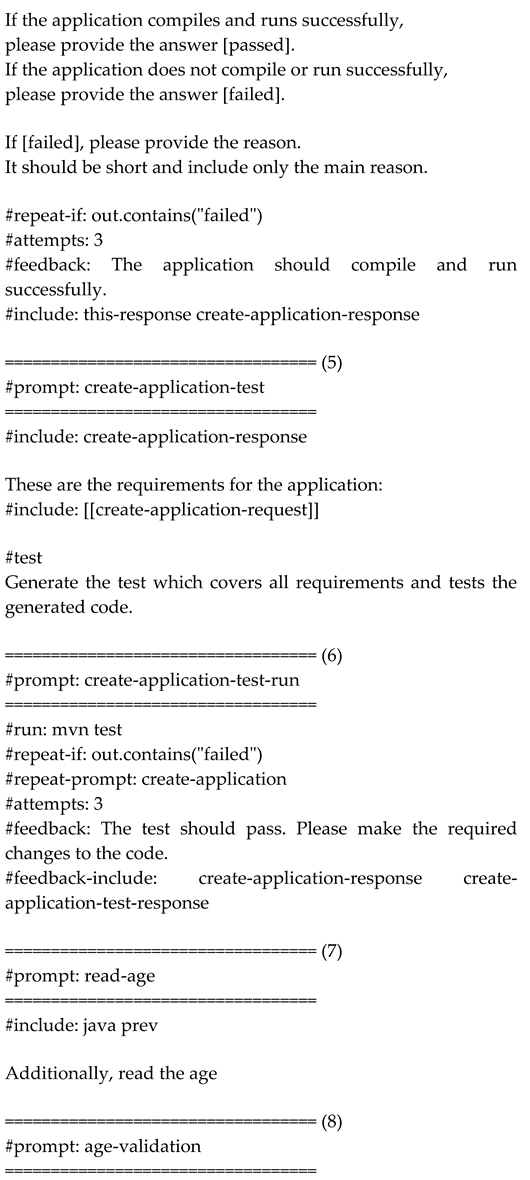

Figure 4 shows an example where generated Java classes include package names. The framework automatically parses these package declarations and organizes the files into appropriate folders based on the package names.

In this example, the generated code includes package declarations like package app.jtutor.shapes. The LLM is explicitly instructed to include package declarations in the generated code. This can typically be achieved by adding a prompt like "Ensure each generated class includes a package declaration." With these declarations, the framework can automatically place the generated code in the correct folder structure. As a result, developers can immediately compile and test the generated code. Without this feature, developers would usually have to manually create and organize the files generated by the LLM, which is both time-consuming and error-prone.

Figure 5 summarizes this automated parsing workflow:

While Java [

20,

21] has a direct mapping between package names and folder structures, other languages like JavaScript [

22,

23] require additional handling. In JavaScript, developers may need to specify the file path explicitly in the prompt. Listing 1 shows an example of this approach:

Listing 1. Example of JavaScript code with file paths included in comments

By including file paths as comments in the generated code, the framework can accurately place JavaScript files in their corresponding directories. Similar techniques can be applied to other programming languages to enable automatic code parsing and directory organization.

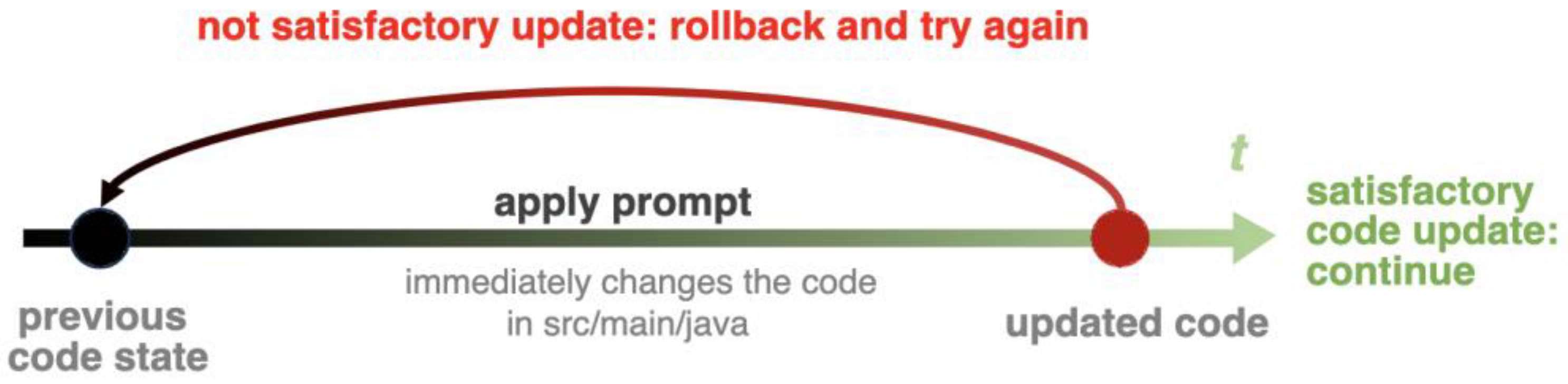

3.3. Automatic Rollbacks

Automatically applying changes to the codebase is a core feature of the framework, achieved through the automatic parsing of the LLM response. The framework handles both creating new files and overwriting updated versions of existing files, ensuring the changes are seamlessly integrated into the project. This allows developers to immediately run and test the generated code. However, there is always a possibility that the generated code may not meet expectations or introduce errors.

To address this, the framework automatically reverts changes when a prompt is modified and re-executed. This ensures that any unsuccessful code generation does not disrupt the codebase, enhancing system reliability and minimizing service disruptions [

24].

Automatic rollback works by comparing the code before and after prompt execution and restoring all modified files to their previous state if needed, as illustrated in

Figure 6. This allows developers to iteratively refine prompts without the risk of breaking the codebase.

Automatic rollbacks are essential for maintaining an agile and error-resistant development process. Developers can safely experiment with different prompts, refining them until the desired output is achieved. Without this feature, manual reversion would be required, leading to higher effort and increased potential for mistakes.

3.4. Automatic Context Discovery

As projects grow in complexity, providing the necessary context to LLMs becomes increasingly challenging. In small projects, developers can explicitly specify relevant files and documentation, but in large-scale systems, manually selecting the right context for each AI request is inefficient and error-prone. Without a structured approach, excessive or missing context can lead to irrelevant responses or incomplete code generation.

To address this, the framework introduces an automated context discovery mechanism that dynamically determines the minimum necessary context to resolve a given issue. This is achieved through a two-step process:

Step 1: Generate Project Index

Before an LLM can efficiently assist with development, it must understand the overall structure of the codebase. To enable this, the framework automatically generates a table of contents (ToC) that summarizes the key components of the project, including:

• Main classes, interfaces, and their relationships.

• API endpoints and exposed services.

• Core business logic modules.

• Database schema and key entities.

• Configuration files and external dependencies.

This project index acts as a navigational map, allowing the framework to locate and retrieve relevant components without analyzing the entire codebase.

Step 2: Select Relevant Context

Once the project index is created, the framework dynamically identifies the minimal context required to address the developer’s query. This process involves:

1. Understanding the Developer’s Request – The framework parses the prompt to identify the affected modules, classes, or APIs.

2. Dependency Analysis – The framework traces dependencies between classes and functions to determine what additional files must be included.

3. Automatic Context Assembly – Based on the identified dependencies, the framework dynamically constructs the optimal context before passing it to the LLM.

For example, if a developer requests:

“Modify the user authentication service to support multi-factor authentication.”

The framework will:

• Identify the UserService class as the main modification target.

• Retrieve dependencies like UserRepository, AuthController, and SecurityConfig.

• Include relevant API documentation and configuration files.

• Exclude unrelated parts of the project, preventing unnecessary context overload.

• Improved Accuracy – The LLM receives only the most relevant information, leading to better code suggestions.

• Scalability – The approach works even for large codebases with thousands of files.

• Efficiency – Reduces manual effort for context selection, enabling developers to focus on high-level tasks.

• Consistency – Ensures that similar queries retrieve the same structured context, improving predictability.

• Reliability – Ensures the inclusion of all relevant dependencies, minimizing errors caused by missing information.

4. Prompt Directives and Prompt Templates

4.1. Prompt Directives

In many cases, prompts need to be configured to achieve optimal performance and control over execution. Directives are special commands that define the behavior of the prompt and allow fine-tuning of various parameters.

Directives work in combination with global configuration settings. For example, while the default LLM model might be GPT-4o [

25], users may opt for a more powerful GPT-o1 model for specific prompts requiring advanced reasoning capabilities. The GPT-o1 series is designed for complex problem-solving tasks in research, strategy, coding, math, and science domains [

26]. By specifying a directive within a prompt, developers can dynamically adjust which model is used.

Commonly used directives include:

This directive specifies the LLM model to use for a given prompt. It allows selecting a more powerful model for complex tasks while opting for a faster, more cost-efficient model for simpler prompts.

This directive adjusts the creativity of the model’s responses. A higher temperature increases variability and creativity, while a lower temperature ensures more deterministic and precise output.

By default, the framework parses LLM responses as Java code and organizes them under

/src/main/java following the Maven folder structure [

27]. However, when the response is not code (e.g., documentation), developers must specify where the generated artifact should be saved. For example,

#save-to: ./docs/docs.md saves the response (generated documentation) to the

docs.md file in the

docs folder.

The framework supports many other directives, allowing developers to fine-tune output format, execution behavior, and additional context provided to the model.

4.2. Merging Generated Code and Manually Updated Code

In Software Engineering, requirements serve as the foundation for product development [

28]. In Agile environments [

29], developers frequently update both:

1. The codebase (manual changes)

2. The requirements (prompt modifications)

This dual evolution introduces a common challenge:

• When AI regenerates code based on updated prompts, it may overwrite manual changes, leading to data loss and frustration.

• Conversely, if a developer modifies the code without updating the prompt, future regenerations may not align with the developer’s manual adjustments.

Solution: AI-Assisted Code Merging

The framework resolves this issue by merging the newly generated output with manually updated code, as shown in

Figure 7. Instead of blindly replacing the code, it introduces a “merge prompt”, instructing the LLM to integrate manual edits with the regenerated version while maintaining consistency with the latest requirements.

This feature allows developers to make changes in the codebase and the requirements independently. The developer can update the codebase manually, and then regenerate the code based on the updated requirements. The framework will merge the manually updated code with the generated code, preserving the developer’s logic and adjustments.

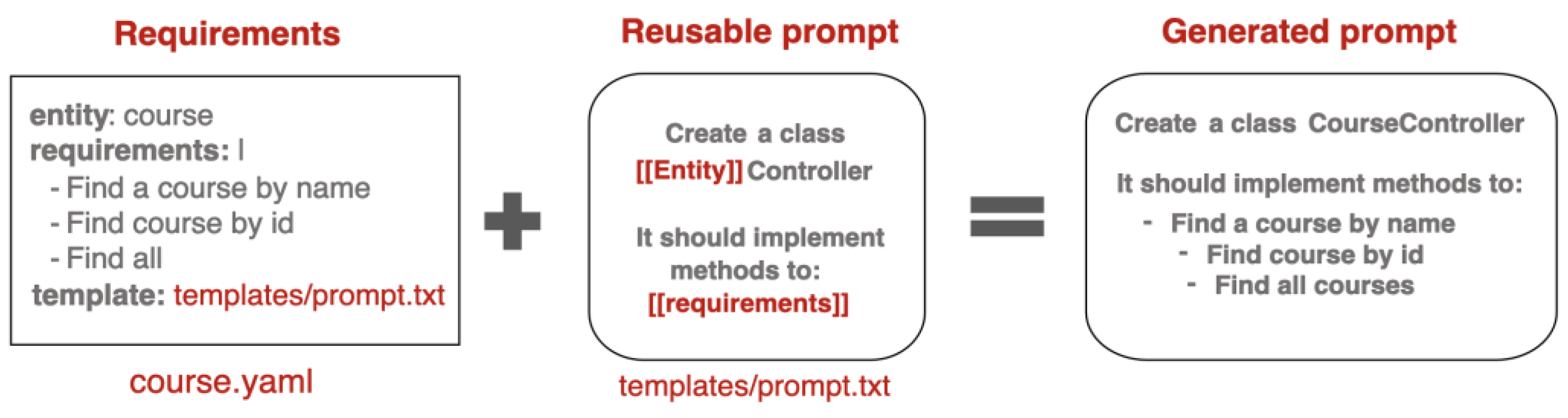

4.3. Reusable Prompt Templates

A key principle of efficient AI-driven automation is reusability. Rather than hardcoding requirements into every prompt, the framework uses placeholders, which are dynamically replaced at runtime with specific values from the requirements file.

In

Figure 8, placeholders such as Entity or requirements are automatically substituted based on real input data, such as course.yaml.

This approach enables:

- Reusing prompts across multiple use cases without modification.

- Adapting workflows dynamically based on changing requirements.

- Reducing redundancy in prompt engineering, making workflows more maintainable.

5. Automating Development with Workflow-Oriented Prompt Pipelines

A key concept for LLM-driven automation is the Chain of Thought [

30,

31], a method where a sequence of prompts is executed sequentially, with the output of each prompt serving as input for the next. This approach enables the automation of multi-step processes and simplifies complex tasks by breaking them into smaller, manageable parts. Similar to the “Divide and Conquer” principle [

32,

33], this strategy improves efficiency and reliability in task execution.

Usually, the development team has an established workflow for development. The larger steps are divided into smaller ones, and each of them is executed sequentially. It is very similar to the Chain of Thought, but the steps are executed manually. The Chain of Thought automates this process.

To create a new feature, the workflow is divided into smaller steps:

Update the domain model

Modify the service layer

Create API endpoints

Write unit tests

Usually, these steps are done manually, although possibly with the aid of AI tools. The goal is to automate this process by defining a prompt pipeline—a sequence of prompts where the output of one step becomes the input for the next. This eliminates manual handoffs and ensures the workflow operates efficiently and consistently.

This way, the developer can automate the whole process of the feature development, ensuring that the generated code is consistent with the requirements.

5.1. Prompt Pipeline for Workflow Automation

A universal prompts pipeline can be defined once and applied to multiple business domains, effectively standardizing code generation across various projects. Usually, the pipeline consists of several prompts, each focusing on a specific aspect of the development process. One prompt can be responsible for generating the domain model, while another prompt can handle the service layer. This approach ensures that each prompt is focused on a specific small task, making the quality of the generated code more reliable.

Figure 9 illustrates how a prompt pipeline operates, with requirements dynamically inserted into placeholders in the prompts.

The important benefit is the ability to change the prompts pipeline and requirements independently. The generated code is decoupled from the workflow, allowing the workflow to be modified without altering the requirements. This separation of concerns provides greater flexibility and maintainability in the code generation process.

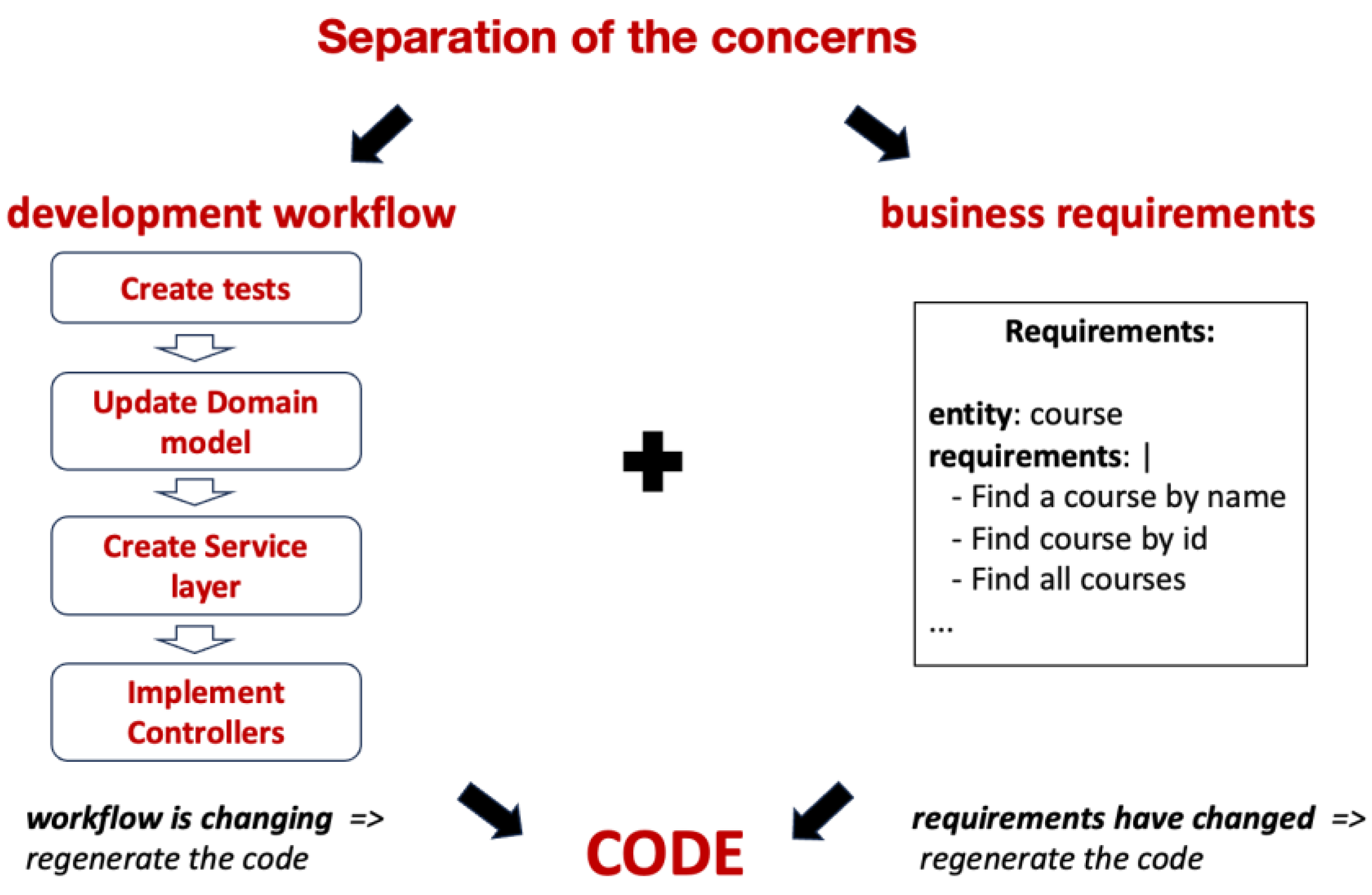

5.2. Separation of Concerns in Workflow Automation

Separation of concerns [

34] is a key principle of the workflow-oriented approach, ensuring that requirements (what should be done) are decoupled from workflows (how it should be done). This decoupling provides flexibility: the same requirements can be reused across multiple workflows, or workflows can be updated independently of the requirements.

Figure 10 illustrates this principle, showing how development workflows and business requirements can be defined independently yet work together to generate consistent, reliable code.

There are two scenarios of the independent changes:

Changing the workflow: When a workflow is updated (e.g., to generate additional documentation), the same requirements can be reapplied to the updated workflow. Steps that have already been executed (e.g., domain model generation) are not re-executed unless affected by the changes. However, if an early step in the workflow is modified, all subsequent dependent steps will be re-executed to ensure consistency.

Changing the requirements: When requirements change, the system automatically rolls back changes made by the previous workflow and regenerates the code to align with the updated requirements. This minimizes manual corrections and allows developers to focus on refining the requirements. Ideally, the workflow is established once, requiring only updates to the requirements or the addition of new ones, while the workflow handles the rest automatically.

The principle of separation of concerns is not new and is widely applied in software development. For example, the Spring Framework [

35] separates code from configuration, allowing developers to update configuration settings without altering the underlying code, and vice versa. Similarly, in the workflow-oriented approach, this principle ensures that workflows and requirements remain independent, enabling updates to one without disrupting the other.

6. Enhancing the Reliability of LLM-Generated Code

AI-powered code generation offers the potential to streamline development workflows, reducing manual effort in repetitive tasks. However, its effectiveness is heavily dependent on reliability. While LLMs have made significant progress in code generation, they are still prone to misinterpretations, inconsistencies, and errors. Mistakes in one step can propagate through subsequent steps, potentially disrupting the entire workflow. For instance, an incorrectly generated domain model may lead to errors in the service layer and API endpoints, requiring manual intervention to fix downstream issues.

One of the most effective ways to mitigate these risks is by breaking down development tasks into smaller, well-defined steps, rather than generating large volumes of code in a single attempt. LLMs excel at producing small code snippets rather than entire systems at once. However, even with smaller steps, compounded minor errors can lead to systemic failures. For example, if each prompt in a 10-step workflow has a 99% reliability rate, the overall success rate drops to 90%, making full automation unreliable without additional safeguards.

In the previous section, we introduced the Chain of Thought approach, which structures code generation into sequential steps, ensuring that the output of one step serves as validated input for the next. This structured workflow reduces the impact of individual errors, making it easier to detect and correct mistakes early. Instead of regenerating an entire feature if a single component is incorrect, the pipeline isolates and fixes only the affected step.

However, even with structured workflows, errors and inconsistencies can still occur. To address these challenges, this section explores key mechanisms to improve the reliability of LLM-generated code, focusing on automated validation and self-healing techniques that allow workflows to detect and correct errors efficiently.

6.1. Self-healing of the generated code

Self-healing mechanisms [

36] enable the system to recover from errors autonomously, minimizing the need for manual intervention. In AI-generated code, errors such as compilation failures, logic inconsistencies, or missing dependencies may arise. Without an automated correction system, developers must manually inspect, debug, and rerun the workflow—defeating the purpose of automation.

To prevent this, self-healing can be implemented through two key mechanisms:

Code Validation with Automated Tests: Generates and runs tests to verify that the code aligns with the requirements, identifying errors automatically.

Code Validation Using LLM Self-Assessment: Uses an LLM to analyze the generated code against predefined requirements.

These mechanisms help maintain code accuracy while reducing the likelihood of manual intervention.

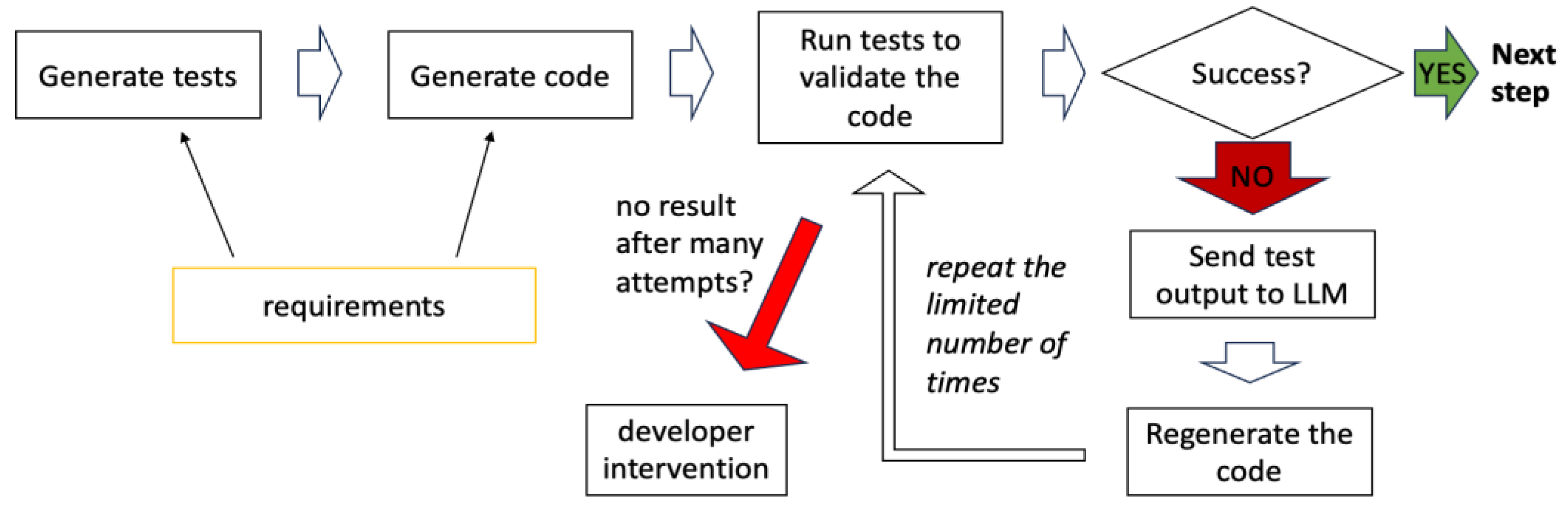

6.2. Code Validation with Automated Tests

Ensuring the reliability of each step in the workflow requires automated validation, which verifies the correctness of the generated code before moving to the next step. Tests should be dynamically generated based on the same requirements that govern code generation.

Figure 11 illustrates this validation workflow.

To prevent infinite loops when correcting errors, it is essential to define a retry limit. If the generated code fails validation, it should be retried a predetermined number of times before escalating the issue. This ensures that minor fixable issues can be resolved automatically while preventing excessive computational overhead.

If the maximum retry attempts are reached without success, the workflow triggers developer intervention, allowing a human to:

Refine the requirements to improve clarity for LLM processing,

Select an alternative model for validation or code regeneration,

Adjust the prompt pipeline to enhance the quality of generated output

Setting an appropriate retry threshold balances automation efficiency with error-handling robustness.

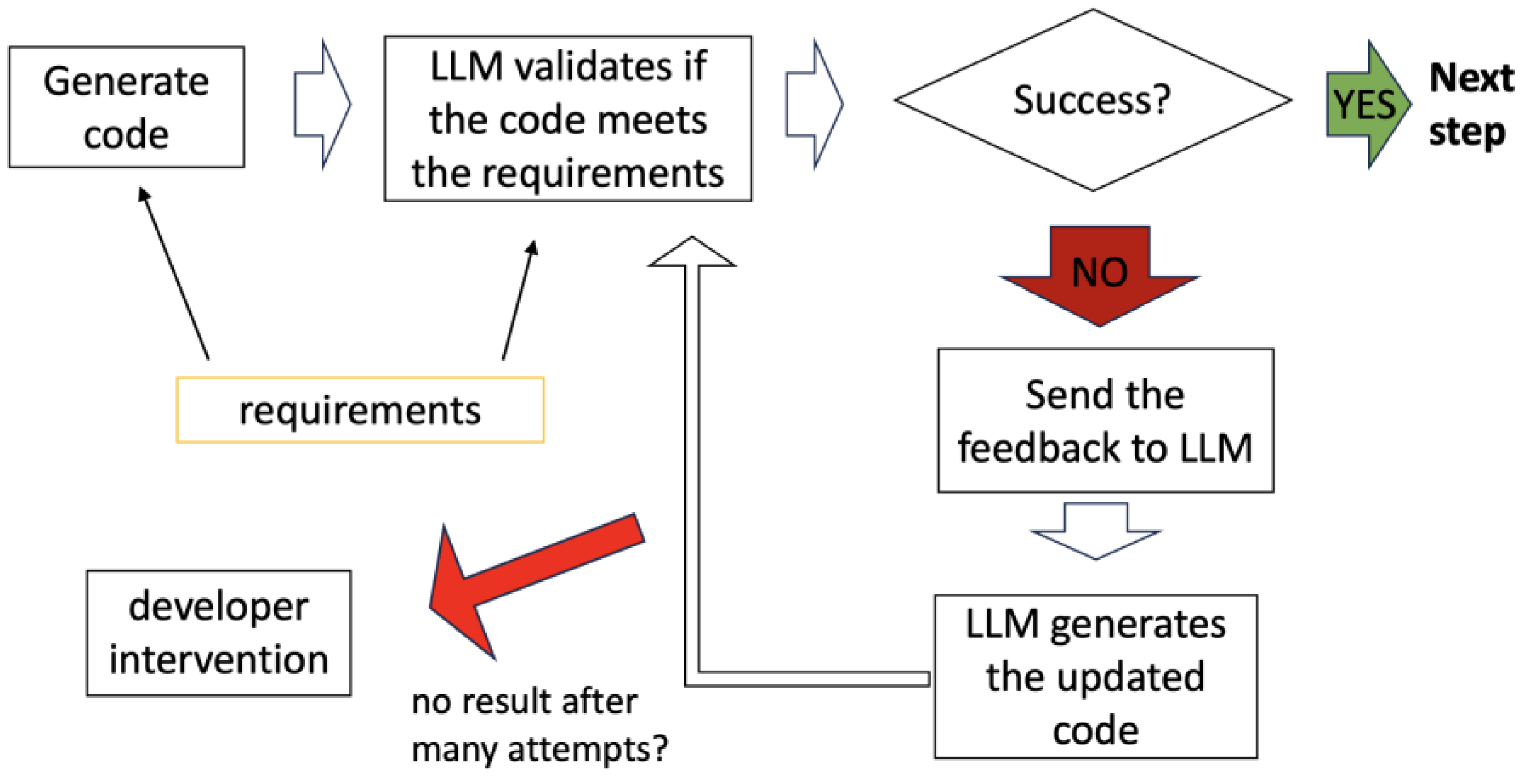

6.3. Code Validation Using LLM Self-Assessment

In some cases, automated tests alone are insufficient. A test may pass even if the generated code does not fully align with the requirements. To address this, LLM-based self-assessment introduces an additional layer of validation. The LLM compares the generated code against the original requirements and provides feedback if discrepancies are detected.

This approach ensures that even if all tests pass, the generated code is still reviewed for logical correctness.

Figure 12 illustrates this validation process.

6.4. Combining Tests and Self-Assessment

Combining automated tests and LLM-based self-assessment offers a comprehensive validation strategy. Tests verify the technical correctness of the code, while self-assessment ensures it meets business requirements—addressing scenarios where tests alone may fall short.

The validating LLM can be different from the generating LLM, adding another layer of reliability. For example:

By separating the roles of generation and validation, inconsistencies in the generating model can be identified before they propagate through the workflow. This division of responsibilities ensures that even complex, multi-step workflows remain accurate and aligned with expectations.

By integrating automated tests and self-assessment mechanisms, workflows can effectively catch both technical errors and requirement misinterpretations. Combining these strategies with multiple LLMs for generation and validation significantly enhances reliability, reducing the need for manual corrections and improving the feasibility of fully automated code generation.

7. Prompt Pipeline Language

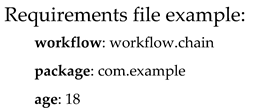

The Prompt Pipeline Language is an experimental approach for describing and executing sequences of prompts for LLMs. It enables prompt chaining, where the output of one prompt serves as the input for the next, supports execution conditions, provides feedback for refinement, and incorporates self-healing mechanisms to address errors.

This language is designed to facilitate automated workflows, allowing for reusable and flexible configurations. The key directives and their usage are examined with a step-by-step example in the next paragraphs.

7.1. Directives in the Prompt Pipeline Language

Directives are commands that define the behavior of the prompt pipeline. They control execution flow, provide feedback, and enable LLMs to generate code based on specified requirements.

Example: In Step (1), the context named java is defined with instructions for generating Java code.

#prompt Specifies a prompt name. Prompts are the building blocks of the pipeline.

#include Includes the specified context or output of a previous prompt into the current prompt. The special keyword prev includes the output of the immediately preceding prompt.

Example: In Step (2), the java context is included (defined in Step (1)), while in Step (6), the prev keyword includes the previous prompt output. Other keywords that can be used are this-response and this-request, prev-request, <prompt-name>-request, and <prompt-name>-response. It allows the inclusion of the input or output of this, or previous or specific prompt into the context provided to the LLM.

Example: In Step (3), feedback is provided if the compilation fails, instructing the LLM to ensure the application compiles and runs.

Example: In Step (3), both the output of the previous prompt (prev-response) and the request of the current prompt (this-request) are included in the feedback to ensure the LLM understands the requirements and the code it has generated.

Example: In Step (3), the prompt repeats if the output contains "failed", with feedback provided to the LLM.

Example: In Step (6), if the create-application-test-run prompt fails, the create-application prompt is executed to regenerate the application code and ensure earlier errors are corrected.

#attempts Specifies the maximum number of attempts for a prompt, including the first attempt and retry attempts. If all attempts fail (#repeat-if condition is met), the workflow stops and requires human intervention.

Example: In Step (3), the number of attempts is 3, which means that the compilation will be retried up to two times if it fails.

Example: In Step (10), the generated documentation is saved to the ./_tests/docs.md file.

Example: In Step (4), the #test directive automatically parses and places the test in the /src/test/java directory.

Example: In Step (3), the mvn exec:java command is run to validate the application.

7.2. Example Workflow

Listing 2 examines an example of the prompt pipeline that generates a Java application to read the name and surname and then validates whether the code meets the requirements.

Next, it attempts to compile the application. If compilation fails, it provides feedback to the LLM and repeats the prompt. If compilation is successful, the test is generated based on the requirements and executed. If the test fails, the prompt is repeated.

Then, it generates the test based on the requirements and runs it. The directive

#test parses the test and places it in the

/src/test/java directory, adhering to the Maven folder structure [

27]. The test is then executed using the Maven command

mvn test. If the test fails, the LLM receives targeted feedback: “The test should pass. Please make the required changes to the code.”

New requirements are then added: the age should be read additionally, and the age must be validated to be greater than the value specified in the requirements. A test for age validation is generated and run. In the final step, short end-user documentation is generated in markdown format and saved to the ./_tests/docs.md file.

Listing 2. Prompt pipeline generating a simple Java application

Initially, the chain of prompts contains only steps (1) to (6). The steps (7) to (10) are added later, after the new requirements are introduced. When new steps are added, the previous steps are not executed again, because they are not changed. Only the new steps are executed.

However, if any of steps (1) to (6) are changed, all subsequent steps are re-executed, because the output of the modified steps can affect the following steps.

This makes adding the new steps to the existing workflow easy and flexible. Additionally, the workflow can be updated independently from the requirements, and the code will be regenerated based on the new requirements.

Step-by-Step Workflow Explanation

-

Step (1): Context Definition

The #context directive defines the reusable block java, which specifies that Java code should follow certain conventions, such as using package com.example.

-

Step (2): Application Creation

The create-application prompt generates an application that reads the user’s name and surname.

Includes: The java context.

Fallback: If this prompt fails, the create-application prompt is retried.

-

Step (3): Application Validation

The validate-application-code prompt validates if the generated code meets the requirements: 1. The class must begin with the package declaration package com.example. 2. It must contain a main method. 3. It must read the name and surname from the console. 4. It must print the name and surname.

-

Step (4): Application Compilation and Execution

The create-application-compile prompt compiles and runs the application using mvn exec:java.

Condition: If the application fails to compile or run, feedback is provided, and the prompt is retried up to two times.

Feedback: "The application should compile and run successfully."

-

Step (5): Test Generation

The create-application-test prompt generates test cases to validate the application’s functionality. - Includes: Output of the create-application prompt and requirements.

-

Step (6): Test Execution

The create-application-test-run prompt executes the tests using mvn test.

Attempts: If the tests fail, they are retried up to two times (the overall number of attempts is 3).

Feedback: "The test should pass. Please make the required changes to the code."

Fallback to Application Creation: If test execution fails, the directive #repeat-prompt: create-application re-executes the earlier prompt to regenerate the code.

New Requirements: Example of the Workflow modification

The Prompt Pipeline Language supports incremental updates to workflows by allowing new steps to be added seamlessly without disrupting prior steps. For example, Steps (7) to (10) were introduced to accommodate additional requirements (reading and validating age, generating documentation). The ability to re-execute only the affected steps ensures that updates are efficient and do not compromise existing functionality.

-

Step (7): Additional Requirements

The read-age prompt updates the application to also read the user’s age.

-

Step (8): Age Validation

The age-validation prompt ensures that the entered age is greater than a specified value from the requirements.

-

Step (9): Age Validation Test

The test-age-validation prompt generates test cases to validate the age input logic.

-

Step (10): Documentation Generation

The final prompt generates end-user documentation for the application, specifying acceptable age values.

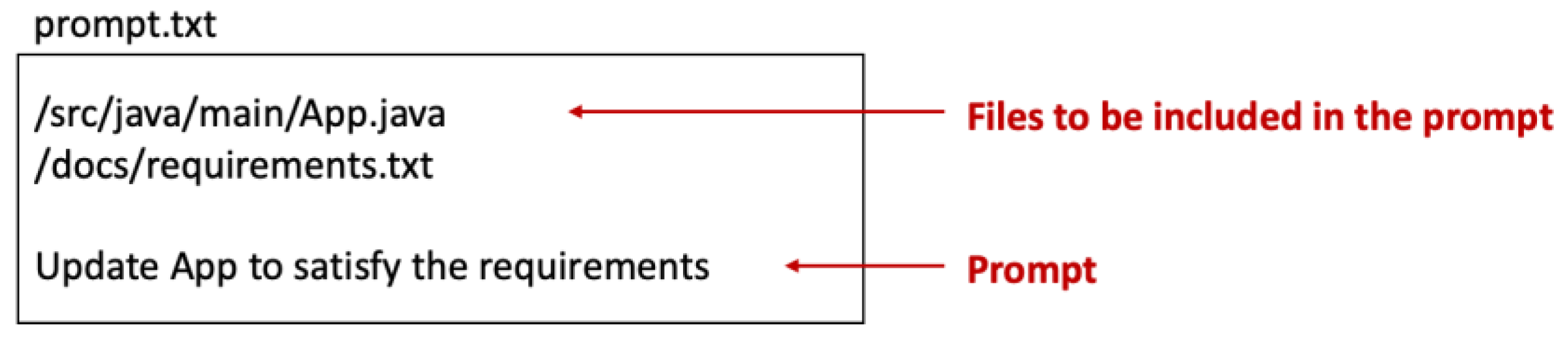

The placeholders, like package or age, are taken from the requirements.yaml file.

The workflow relies on a requirements.yaml file to provide customizable parameters, such as the package name and age requirements.

Here, workflow specifies the chain of prompts to execute, the package defines the Java package name, and age sets the minimum age requirement. These parameters are used to replace the placeholders in the prompt pipeline, making it more flexible and adjustable.

7.3. Automating Workflow Creation

The Prompt Pipeline Language enables the creation of structured, reusable workflows that automate multi-step processes while ensuring both flexibility and reliability. By enforcing a structured execution flow and incorporating validation mechanisms, workflows not only ensure consistency but also enhance predictability and determinism. Each step follows predefined logic, reducing variability in results and minimizing errors. This structured approach ensures that given the same inputs, the workflow consistently produces the same, reliable output—eliminating unexpected deviations and making AI-driven development more controlled and repeatable.

However, manually designing a workflow can be time-consuming and complex, especially for large projects. Developers must carefully define each step, specify execution conditions, and implement retry mechanisms to ensure reliability. While this structured approach enhances automation, the initial effort required to create a workflow may slow down adoption. Additionally, for similar types of tasks, manually defining a workflow repeatedly introduces unnecessary redundancy.

To address these challenges, workflow generators can be introduced to automate workflow creation while maintaining reliability and predictability. Instead of manually defining each prompt, a workflow generator constructs a complete pipeline using best practices from a minimal set of user-provided requirements.

A workflow generator can:

• Analyze the described task and determine the optimal sequence of prompts.

• Apply best practices for execution flow, validation, and error handling.

• Automatically construct a structured workflow in the Prompt Pipeline Language.

Using a workflow generator offers several advantages over manual workflow creation:

• Reduces setup time: Manually defining a workflow requires specifying each step, handling errors, and structuring execution logic. A workflow generator eliminates this overhead.

• Ensures best practices: The generated workflow follows proven patterns for validation, error handling, and execution.

• Maintains predictability and reliability: While the workflow is automatically generated, it still executes in a structured and deterministic manner.

• Allows rapid iteration: Developers can refine requirements and regenerate workflows on demand without manually modifying each step.

Example: Generating a Workflow from Minimal Input

A developer might describe a task as follows:

“Create a Java application that reads name, surname, and age from the console, then validates that the age is greater than 18.”

A workflow generator could automatically construct the corresponding Prompt Pipeline Language workflow, ensuring that:

The application reads name, surname, and age from the console.

The generated code is validated.

The application is compiled and executed.

Tests are generated and executed.

If errors occur, the process automatically retries or provides feedback to the LLM for corrections.

By combining the Prompt Pipeline Language with AI-driven workflow generation, developers can seamlessly transition from natural language requirements to fully automated development workflows.

Automation does not mean loss of control—developers can review, modify, and refine generated workflows while benefiting from faster setup, best practices, and structured execution. Workflow generators enable faster onboarding, reduced manual effort, and increased consistency, ensuring that automation remains both efficient and predictable.

8. Practical Applications of Workflow-Oriented AI Code Generation

The workflow-oriented approach to AI code generation offers numerous practical applications by automating repetitive, routine tasks that developers frequently encounter. By applying this framework, developers can streamline tasks across various stages of the software development lifecycle, as illustrated in the following examples:

Implement New Features: The framework can automate the generation of boilerplate code, including REST API endpoints [

39], service classes, and database models, using reusable prompt pipelines. This speeds up repetitive tasks, such as creating CRUD operations [

6], standard controllers, and DTO classes [

7]. This approach is particularly effective for established practices where processes are well-defined and easily automated.

Code Review: The framework can automate code reviews to ensure adherence to coding standards, best practices, and potential bug detection [

40]. It generates detailed reports with suggestions for improvements, streamlining and enhancing the thoroughness of the review process. Users can customize the rules to be checked, specify ignored rules, and define the report format. Additionally, the framework can automatically apply fixes for detected issues, further reducing manual effort.

Fixing Bugs: The framework can assist in fixing simple bugs that do not require extensive debugging (with future potential to incorporate debugging capabilities). It analyzes the code, identifies the issue, applies a fix, and runs tests to verify the resolution.

Generate Tests: The framework can automatically generate unit tests for existing classes, improving test coverage. Test cases are created based on the code structure, method signatures, and expected behavior, providing a robust foundation for test-driven development (TDD).

Code Refactoring: The framework enhances code quality by refactoring large, complex methods into smaller, more manageable ones. It offers suggestions for optimizing code and improving readability, maintainability, and efficiency.

Analyze Security Flaws: The framework identifies and resolves common security vulnerabilities, such as SQL injection, by analyzing the code and recommending secure coding practices.

Replace Deprecated APIs: The framework automates the process of updating code that uses deprecated APIs by identifying outdated methods and classes and applying appropriate replacements. This ensures seamless migration to newer API versions, provided the framework has knowledge of the deprecations and their replacements.

Fix Code Smells: The framework detects code smells [

5], such as duplicated code, long methods, and complex conditionals, and offers refactoring suggestions to enhance code quality and maintainability.

Generate the Documentation: The framework automates the generation of documentation for code segments, such as REST endpoints, classes, and methods. It produces detailed, customizable documentation in the desired format, ensuring alignment with the latest code changes.

These use cases demonstrate the transformative potential of workflow-oriented AI code generation in automating repetitive tasks, improving code quality, and accelerating development cycles. As this approach evolves, it promises to further integrate into software development pipelines, fostering greater productivity and innovation.

9. Framework Reference Implementation: JAIG

Building on the principles of workflow-oriented AI code generation discussed earlier, this section introduces a practical reference implementation: JAIG (Java AI-powered Code Generator). JAIG serves as a proof of concept, demonstrating the core capabilities of the workflow-centric framework while enabling experimentation with workflow automation.

JAIG is a command-line tool designed to automate various stages of the software development lifecycle through AI-driven code generation. Targeted at Java projects, JAIG leverages OpenAI GPT models for code generation and integrates seamlessly with IntelliJ IDEA [

41]. As an open-source project, JAIG encourages collaboration and experimentation, with its source code and documentation available on GitHub.

This paper outlines the conceptual ideas behind JAIG, while the official documentation on GitHub and the website

https://jaig.pro provide detailed guidance on installation, usage, and configuration.

While JAIG is still a work in progress, it already implements several core features that showcase the potential of the workflow-centric framework. These include feeding necessary context to the LLM, automatic parsing of generated code, and automatic rollbacks, making it suitable for practical experimentation. Upcoming features, such as self-healing mechanisms, automated code validation through tests, and full support for the Prompt Pipeline Language, are currently under development and will further enhance JAIG’s capabilities.

10. Conclusions

The workflow-centric framework for AI-driven code generation presented in this paper addresses key limitations of existing AI-assisted coding tools. By automating the entire software development lifecycle—from requirements gathering to code generation, testing, and deployment—the framework significantly reduces the need for manual intervention. The foundational building blocks, including feeding the necessary context to LLMs, automatic parsing of generated code, and automatic rollbacks, enable developers to streamline multi-step workflows while ensuring reliability and scalability.

The reference implementation, JAIG, demonstrates the practical application of this framework for Java-based projects. While it showcases the potential of AI to handle repetitive tasks and automate complex workflows, certain advanced features like self-healing mechanisms, automated test generation, and the full implementation of the Prompt Pipeline Language are still under development.

Opportunities for Future Development

• Broader Language Support: Extending beyond Java to support languages like Python, JavaScript, and C++.

• Integrated Debugging Capabilities: Introducing automated debugging tools that can identify, analyze, and suggest fixes for issues in generated code or workflow execution. This feature would reduce manual intervention during error handling.

• Integration with CI/CD Pipelines: Incorporating the framework into continuous integration and deployment pipelines can further streamline development workflows.

• Interactive Workflow Optimization: Adding real-time feedback and recommendations for improving prompts or workflows during execution will make the framework more intuitive and user-friendly.

• Workflow Visualization: Incorporating visualization features would enable developers to gain a clear understanding of their workflows, identify bottlenecks, and optimize processes effectively. Adding debugging capabilities, such as setting breakpoints to pause execution and visually inspecting the state of each step, would streamline troubleshooting and make it easier to analyze and refine complex workflows.

• Testing Workflow Reliability: Verifying that a sequence of prompts consistently produces the intended outputs across various requirements could be a valuable addition.

• Integration with Industry-Standard Tools: Enhancing compatibility with tools such as IDEs, testing frameworks (e.g., JUnit, Mocha), and project management platforms (e.g., Jira, GitLab) will make the framework a central component of existing software development ecosystems.

Final Thoughts

This paper moves beyond AI-assisted coding toward full automation of software development workflows. By combining structured execution, self-healing mechanisms, and automated validation, the framework improves consistency, reduces human intervention, and accelerates software delivery.

As AI technology evolves, this approach has the potential to redefine software engineering, allowing developers to focus on high-level architecture and logic while AI automates repetitive development tasks. Future research will continue to refine these methodologies, bridging the gap between AI-driven assistance and fully autonomous software generation—while ensuring human oversight and control remain central.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S..; formal analysis, V.S.; investigation, V.S. and C.T.; methodology, V.S..; software, V.S.; supervision, V.S. and C.T.; validation, V.S. and C.T.; writing—original draft, V.S..; writing—review and editing, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- GitHub Copilot, Available online: https://github.com/features/copilot.

- Cursor, the AI Code Editor, Available online: https://www.cursor.com/.

- Iusztin, P.; Labonne, M. LLM Engineer's Handbook: Master the art of engineering large language models from concept to production; Packt Publishing, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raschka, S. Build a Large Language Model; Manning: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, M. Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code (2nd Edition); Addison-Wesley Professional, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bonteanu, A.-M.; Tudose, C.; Anghel, A.M. Multi-Platform Performance Analysis for CRUD Operations in Relational Databases from Java Programs using Spring Data JPA. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Advanced Topics in Electrical Engineering (ATEE), Bucharest, Romania, 23–25 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tudose, C. Java Persistence with Spring Data and Hibernate; Manning: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tudose, C. JUnit in Action; Manning: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, E. Mastering SQL Injection: A Comprehensive Guide to Exploiting and Defending Databases; 2023.

- Caselli, E.; Galluccio, E.; Lombari, G. SQL Injection Strategies: Practical techniques to secure old vulnerabilities against modern attacks; Packt Publishing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, S. Is GitHub Copilot a Substitute for Human Pair-programming? An Empirical Study, ACM/IEEE 44th International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceedings, 2022, 319-321.

- Nguyen, N.; Nadi, S. An Empirical Evaluation of GitHub Copilot's Code Suggestions, 2022 Mining Software Repositories Conference, 2022, 1-5.

- Zhang, B.Q.; Liang, P.; Zhou, X.Y.; Ahmad, A.; Waseem, M. Demystifying Practices, Challenges and Expected Features of Using GitHub Copilot. International Journal of Software Engineering and Knowledge Engineering 2023, 33, 1653–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetistiren, B.; Ozsoy, I.; Tuzun, E. Assessing the Quality of GitHub Copilot's Code Generation, Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Predictive Models and Data Analytics in Software Engineering, 2022, 62-71.

- Suciu, G.; Sachian, M.A.; Bratulescu, R.; Koci, K.; Parangoni, G. Entity Recognition on Border Security, Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, 2024, 1-6.

- Jiao, L.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, F.; Li, L.; Shang, R.; Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Yang, S. Nature-Inspired Intelligent Computing: A Comprehensive Survey. Research 2024, 7, 0442. [Google Scholar]

- El Haji, K.; Brandt, C.; Zaidman, A. Using GitHub Copilot for Test Generation in Python: An Empirical Study, Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automation of Software Test, 2024, 45-55. A.

- Tufano, M.; Agarwal, A.; Jang, J.; Moghaddam, R.Z.; Sundaresan, N. AutoDev: Automated AI-Driven Development. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.08299. [Google Scholar]

- Ridnik, T.; Kredo, D.; Friedman, I. Code Generation with AlphaCodium: From Prompt Engineering to Flow Engineering. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.08500. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K.; Gosling, J.; Holmes, D. The Java Programming Language, 4th ed.; Addison-Wesley Professional: Glenview, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, K.; Bates, B.; Gee, T. Head First Java: A Brain-Friendly Guide, 3rd ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, P. JavaScript: The Comprehensive Guide to Learning Professional JavaScript Programming; Rheinwerk Computing, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Svekis, L.L.; van Putten, M.; Percival, R. JavaScript from Beginner to Professional: Learn JavaScript quickly by building fun, interactive, and dynamic web apps, games, and pages; Packt Publishing, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Amazon AWS Documentation, Available online: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/wellarchitected/latest/devops-guidance/dl.ads.2-implement-automatic-rollbacks-for-failed-deployments.html.

- Chatbot App, Available online: https://chatbotapp.ai.

- Using OpenAI o1 models and GPT-4o models on ChatGPT, Available online: https://help.openai.com/en/articles/9824965-using-openai-o1-models-and-gpt-4o-models-on-chatgpt.

- Varanasi, B. Introducing Maven: A Build Tool for Today's Java Developers; Apress, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville, I. Software Engineering, 10th ed.; Pearson, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anghel, I.I.; Calin, R.S.; Nedelea, M.L.; Stanica, I.C.; Tudose, C.; Boiangiu, C.A. Software development methodologies: A comparative analysis. UPB Sci. Bull. 2022, 83, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Z.; Fang, Y.H.; Li, X.L.; Huang, Z.; Lee, M.; Memisevic, R.; Su, H. Deductive Verification of Chain-of-Thought Reasoning Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 2023.

- Li, L.H.; Hessel, J.; Yu, Y.; Ren, X.; Chang, K.W.; Choi, Y. Symbolic Chain-of-Thought Distillation: Small Models Can Also "Think" Step-by-Step, Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, 1, 2665-2679.

- Cormen T., H.; Leiserson, C.; Rivest, R.; Stein, C. Introduction to Algorithms; MIT Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.R. Top-Down Synthesis of Divide-and-Conquer Algorithms. Artificial Intelligence 1985, 27, 43–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daga, A.; de Cesare, S.; Lycett, M. Separation of Concerns: Techniques, Issues and Implications. Journal of Intelligent Systems 2006, 15, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, C. Spring in Action; Manning: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D.; Sharman, R.; Rao, H.R.; Upadhyaya, S. Self-healing systems - survey and synthesis. Decision Support Systems 2007, 42, 2164–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claude Sonnet Official Website, Available online: https://claude.ai/.

- Claude 3.5 Sonnet Announcement, Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-5-sonnet.

- Fielding, R.T. Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures. PhD Thesis, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.C. Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship; Pearson, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- IntelliJ IDEA Official Website, Available online: https://www.jetbrains.com/idea/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).