Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Protocol

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria (Population Concept Context (PCC) Framework)

- Population: Studies involving OSCC in any form. These included experiments on human oral cancer cell lines (e.g., ORL-48, SCC-9, and KB), animal models of oral/oropharyngeal carcinoma, and human subjects (patients) diagnosed with OSCC.

- Concept: This study investigated the antioxidant and anticancer activities of α-tocopherol and Stichopus hermanii extract. This encompassed α-tocopherol used as a single isolated compound (vitamin E) or as a component of crude extracts of S. hermanii. We included studies that measured relevant molecular or cellular outcomes such as oxidative stress markers (e.g., ROS levels, malondialdehyde [MDA], and antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, glutathione [GSH], and catalase) or cancer-related biomarkers/pathways (e.g., apoptosis induction, caspase activation, Bcl-2/Bax expression, cell proliferation, tumor growth, and expression of oncogenes or tumor suppressors).

- Context: Any research or clinical context relevant to oral squamous cell carcinoma was considered. These include in vitro laboratory experiments, in vivo studies in animal models, and clinical studies (including observational studies) involving patients with OSCC. We did not restrict the geographical location or setting.

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Charting and Extraction

- Citation details: Author(s), year of publication and title.

- Study design and context: Type of study (in vitro, in vivo, or clinical), specific model or population (cell line used, animal species and strain, patient population characteristics, etc.), and overall study aim related to OSCC.

- Intervention details: The form of α-tocopherol used (isolated α-tocopherol compound, synthetic vs. natural source, or S. hermanii extract containing α-tocopherol), dosage and duration of treatment, and route of administration (e.g., cell culture treatment, oral gavage in animals, and oral supplement in patients).

- Comparators: Description of control or comparison groups (such as untreated controls, vehicle controls, or alternative treatments such as standard antioxidants/drugs, if applicable).

- Outcomes measured: Molecular and biochemical targets or markers were assessed. These included antioxidant outcomes (e.g., levels of MDA and activities of SOD, GSH, and catalase), anticancer/cellular outcomes (e.g., cell viability, apoptosis rates, expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins such as caspase-3, caspase-9, Bcl-2, Bax, cell cycle phase distribution, tumor incidence, or size in animal models), and any other relevant OSCC-related molecular pathway data (e.g., signaling pathway activation/inhibition such as Akt phosphorylation status and expression of genes such as TP53 and VEGF, if reported).

- Key findings: A summary of the main results for these outcomes (for example, whether α-tocopherol treatment significantly reduced MDA levels or increased the apoptotic index compared to controls, including quantitative effects when reported).

- Conclusions of authors: The original study interpreted its findings (e.g., “α-tocopherol showed potential as an antiproliferative agent in OSCC cells by inducing apoptosis” or similar statements).

2.6. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

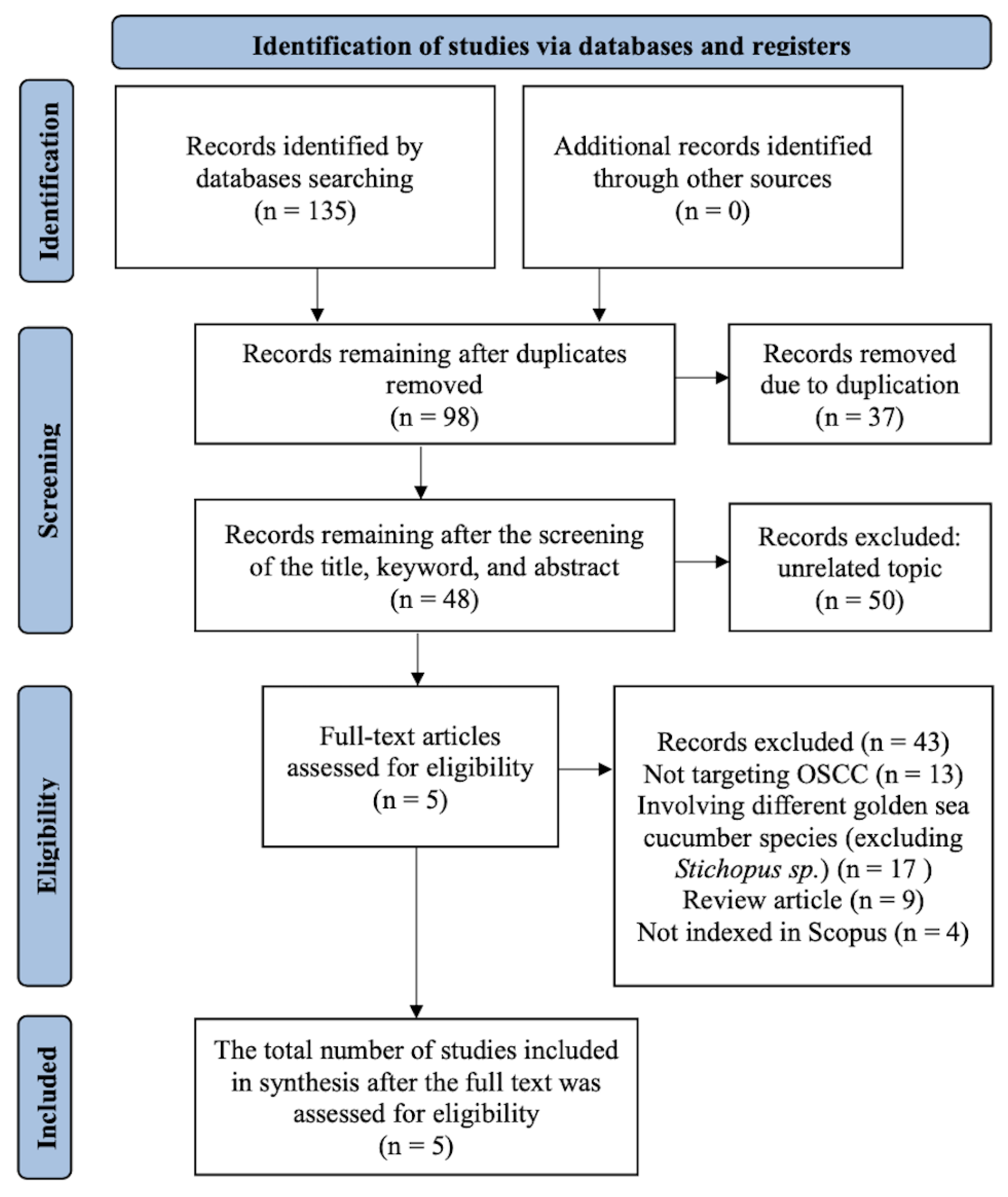

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Antioxidant and Pro-Apoptotic Effects of α-Tocopherol in OSCC Models

4.2. Trends, Heterogeneity, and Knowledge Gaps

4.3. Research Gaps and Future Directions

- Investigation of OSCC-Specific Pathways: Studies should investigate how α-tocopherol influences key oncogenic pathways (e.g., EGFR, MAPK, NF-κB, TP53, RAS, and angiogenesis) to determine whether its effects are broad-spectrum or pathway-specific.

- Standardization of Interventions: Future studies should standardize formulations and dosages, directly compare pure α-tocopherol with S. hermanii extracts, and establish equivalent dosing to guide preclinical and clinical applications.

- Expanded Preclinical Models: Dedicated OSCC animal models, including immune-competent and xenograft systems, should be used to evaluate molecular, histological, and therapeutic outcomes as well as long-term safety and toxicity.

- Clinical Trials in Patients with OSCC: Randomized controlled trials are urgently needed to test α-tocopherol and S. hermanii supplementation in patients with OSCC, assessing not only biochemical endpoints but also clinical outcomes, such as mucositis, tumor response, recurrence, and survival, with careful patient stratification and dosing strategies.

- Long-Term and Synergistic Effects: Research should explore the potential risks of high-dose antioxidants, their long-term safety, and their possible synergies with standard therapies (e.g., enhancing cisplatin cytotoxicity or protecting normal tissues during radiotherapy).

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Riskayanti NP, Riyanto D, Winias S. Manajemen multidisiplin oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC): laporan kasus. Intisari Sains Med. 2021;12(2):621–626. [CrossRef]

- Matsuo K, Akiba J, Kusukawa J, Yano H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: subtypes and morphological features affecting prognosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2022;323:C1611–C1623. [CrossRef]

- Cabral LGS, Martins IM, Paulo EPA, Pomini KT, Poyet JL, Maria DA. Molecular mechanisms in the carcinogenesis of oral squamous cell carcinoma: a literature review. Biomolecules. 2025;15(5): Article 621.

- Gamal-Eldeen AM, Raafat BM, Alrehaili AA, El-Daly SM, Hawsawi N, Banjer HJ, et al. Anti-hypoxic effect of polysaccharide extract of brown seaweed Sargassum dentifolium in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Front Nutr. 2022;9:854780. [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):309–316. [CrossRef]

- Rivera C. Essentials of oral cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(9):11884–11894. PMID: 26617944.

- Fatwati K, Amin A, Indriani L, Ladju RB, Akbar FH, Hamrun N. GC-MS analysis and in silico approaches to Stichopus hermanii as anti-inflammatory through PKC-β inhibition. Results Chem. 2025;??:102086. [CrossRef]

- Fachry MF, Damayanti I, Damoro P, Jubhari EH, Thalib B, Habibie A. Effectiveness of golden sea cucumber (Stichopus hermanii) extract gel on increasing RANKL expression process modeling in post-extraction tooth. Makassar Dent J. 2025;14(1):35–39.

- Damaiyanti DW, Soesilowati P, Arundina I, Sari RP. Effectiveness of gold sea cucumber (Stichopus hermanii) extracts in accelerating the healing process of oral traumatic ulcer in rats. Padjadjaran J Dent. 2019;31(3):208–214. [CrossRef]

- Salindeho N, Nurkolis F, Gunawan WB, Handoko MN, Samtiya M, Muliadi RD. Anticancer and anticholesterol attributes of sea cucumbers: an opinion in terms of functional food applications. Front Nutr. 2022;9:986986. [CrossRef]

- Niki E. Role of vitamin E as a lipid-soluble peroxyl radical scavenger: in vitro and in vivo evidence. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;66:3–12. [CrossRef]

- Bei MF, Domocoş D, Szilágyi G, Varga DM, Pogan MD. Influence of vitamins and antioxidants in oral carcinogenesis – a review. Pharmacophore. 2023;14(6):39–45. [CrossRef]

- Talib WH, Jum’ah DAA, Athamneh K, Jallad MS, Kury LTA, Hadi F, et al. Role of vitamins A, C, D, E in cancer prevention and therapy: therapeutic potentials and mechanisms of action. Front Nutr. 2024;10:1281879. [CrossRef]

- Zulkapli R, Razak FA, Zain RB. Vitamin E (α-tocopherol) exhibits antitumour activity on oral squamous carcinoma cells ORL-48. Integr Cancer Ther. 2016;16(3):414–425. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran P, Athira AP, Yin OF, Swathy SS, Nishanth R, Sakthivel KM, et al. PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-mediated autophagy in oral carcinoma: a comprehensive review. Int J Med Sci. 2024;21(6):1165–1175. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhuo X, Khuri FR, Shin DM. Induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by a combined treatment with 13-cis-retinoic acid, interferon-α2a, and α-tocopherol in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2007;29(4):351–361. [CrossRef]

- Safithri M, Tarman K, Setyaningsih I, Fajarwati Y, Dittama IYE. In vitro and in vivo malondialdehyde inhibition activities of Stichopus hermanii and Spirulina platensis. Hayati J Biosci. 2022;29(6):771–781.

- Xu M, Yang H, Zhang Q, Lu P, Feng Y, Geng X, et al. α-Tocopherol prevents esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by modulating PPARγ–Akt signaling pathway at the early stage of carcinogenesis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(56):95914–95930. [CrossRef]

- Chitra S, Devi SS. Effect of α-tocopherol on pro-oxidant and antioxidant enzyme status in radiation-treated oral squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J Med Sci. 2008;62(4):141–148. PMID: 18445980.

- Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49(11):1603–1616. [CrossRef]

- Hossain A, Dave D, Shahidi F. Antioxidant potential of sea cucumbers and their beneficial effects on human health. Mar Drugs. 2022;20(8):521. [CrossRef]

| No. | Author (Year) | Title | Study Design | Intervention | Comparison | Analysis Technique | Outcome Measures | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Zulkapli et al. (2017) [11] | Vitamin E (α-Tocopherol) Exhibits Antitumour Activity on Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells ORL-48 | In vitro (cell culture of OSCC ORL-48 cells) | Treatment with pure α-tocopherol | Control group (untreated ORL-48 cells) | MTT assay (cell viability), flow cytometry (apoptosis), DAPI staining (nuclear morphology) | Cell viability percentage, number of apoptotic cells, nuclear morphology | α-Tocopherol significantly reduced ORL-48 cell viability and induced dose-dependent apoptosis |

| 2. | Zhang et al. (2007) [12] | Induction of Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis by a Combined Treatment with 13-Cis-Retinoic Acid, Interferon-α2a, and α-Tocopherol in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck | In vitro (lab study on squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck) | Combination of 13cRA, IFN-α, and α-tocopherol | Single agents, dual combinations and untreated control | SRB assay, FACS, Western blot, ELISA, Annexin V staining | Cell growth inhibition, apoptosis %, G1/S arrest, caspase and Bcl-2 expression | Triple combination synergistically induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest |

| 3. | Safithri et al. (2022) [13] | In Vitro and In Vivo Malondialdehyde Inhibition Activities of Stichopus hermanii and Spirulina platensis | Combined in vitro and in vivo study (STZ-induced diabetic rats) | Methanolic extracts of S. hermanii and S. platensis; α-tocopherol as positive control | In vitro: α-tocopherol 200 ppm; In vivo: normal, STZ only, +SH, +SP, +glibenclamide | MDA-TBA assay, serum/liver MDA, RBC SOD & CAT via ELISA | MDA inhibition (%), serum/liver MDA (nmol/ml), SOD, CAT activity | SH reduced serum MDA (~86%), SP reduced liver MDA (~59%) |

| No. | Author (Year) | Title | Study Design | Intervention | Comparison | Analysis Technique | Outcome Measures | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Xu et al. (2017) [14] | Alpha-Tocopherol Prevents Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Modulating PPARγ-Akt Signaling Pathway at the Early Stage of Carcinogenesis | In vivo (study on F344 rats induced with NMBA carcinogen) | Dietary administration of pure α-tocopherol | Negative control, NMBA only, NMBA + α-Tocopherol | Western blot, IHC, qPCR, H&E staining, pathology scoring | Lesion count and severity, expression of PPARγ, Akt, p-Akt, caspase-3, Bcl-2, Bax | α-Tocopherol inhibited carcinogenesis via PPARγ upregulation and Akt phosphorylation suppression |

| 2. | Safithri et al. (2022) [13] | In Vitro and In Vivo Malondialdehyde Inhibition Activities of Stichopus hermanii and Spirulina platensis | Combined in vitro and in vivo study (STZ-induced diabetic rats) | Methanolic extracts of S. hermanii and S. platensis; α-tocopherol as positive control | In vitro: α-tocopherol 200 ppm; In vivo: normal, STZ only, +SH, +SP, +glibenclamide | MDA-TBA assay, serum/liver MDA, RBC SOD & CAT via ELISA | MDA inhibition (%), serum/liver MDA (nmol/ml), SOD, CAT activity | SH reduced serum MDA (~86%), SP reduced liver MDA (~59%) |

| No. | Author (Year) | Title | Study Design | Intervention | Comparison | Analysis Technique | Outcome Measures | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Chitra et al. (2008) [15] | Effect of α-Tocopherol on Pro-Oxidant and Antioxidant Enzyme Status in Radiation-treated Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Clinical observational study (OSCC patients undergoing radiotherapy) | Oral supplementation of α-tocopherol during radiotherapy | OSCC patients without vitamin E supplementation | Spectrophotometry: estimation of MDA, SOD, GSH, and catalase activity | MDA levels, SOD, GSH, and catalase activity before and after radiotherapy | α-Tocopherol significantly reduced MDA and enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).