1. Introduction

Social representations are forms of shared knowledge that facilitate the interpretation of phenomena that disrupt everyday life through communication and social interaction [

1,

2]. They emerge in response to novel events and are constructed through anchoring, which links the unknown to pre-existing knowledge, and objectification, which organizes elements of the phenomenon into images or metaphors that are understandable to the group [

3]. The relevance of social representations becomes particularly evident in the face of new social phenomena, as they enable individuals to organize the vast amount of available information and promote social interaction. Castorina [

4] characterizes them as episodic, as they allow individuals to fill informational gaps by imaginatively constructing abstract concepts, thereby overcoming exceptional circumstances while adapting to the specific cultural and historical context of each social group.

The literature indicates that in every historical period, social groups construct their own representations of risk, which are analyzed through narratives and images [

5]. Bravi [

3] argues that, when addressing environmental issues, the media articulate scientific knowledge with common sense [

1]. In the digital era, this knowledge is disseminated primarily through social networks. According to Luhmann [

6], the mass media shape social knowledge and, from the perspective of Social Representations Theory, they not only transmit it but also integrate it into preexisting collective beliefs. Consequently, the analysis of media content makes it possible to understand how social groups interpret the environment and its socio-natural risks. This knowledge is adjusted and incorporated into pre-established interpretative frameworks, thereby facilitating the comprehension of environmental changes.

1.1. The Impact of Wildfires on Socio-Ecosystems

The Impact of Wildfires on Socio-Ecosystems In Chile, more than 95% of the wildfires that occur at the wildland-urban interface are caused by human activities [

7,

8]. The expansion of urban areas into rural areas has increased both the frequency of these events and the vulnerability of exposed communities [

9,

10]. This phenomenon poses significant challenges for the protection of housing, the safety of firefighting personnel, and the reduction of associated economic costs [

11].

The expansion of the interface, driven by internal migration to natural areas [

12], increases the risks for both individuals and critical infrastructure [

13,

14]. In addition, land-use changes exert greater pressure on ecosystems, homogenize landscapes, and generate new socio-environmental conflicts [

15]. As a result, wildfire management becomes increasingly complex, requiring a territorial approach that integrates social, environmental, and public health dynamics [

16].

1.2. Wildland–Urban Interface Areas in the Valparaíso Region

The main territorial transformations in central Chile are closely related to urbanization processes that increase the vulnerability of areas with significant environmental value [

17]. The urban and peri-urban expansion to protected wildland areas (Áreas Silvestres Protegidas, ASP) in the Valparaíso region grew substantially between 2003 and 2015, exerting pressure on these zones due to changes in land occupation driven by the presence of ASPs [

18]. This growth, which began in 1985, is evident in subdivision-type settlements located near areas of high ecological value [

19]. Such expansion may be explained by internal migration seeking greater comfort and proximity to nature, a phenomenon known as amenity migration, which reflects biocentric lifestyles [

20] and constitutes a key driver of global rural transformation [

21]. Moreover, it alters population composition, with a predominance of older adults [

22]. Therefore, population growth in areas vulnerable to wildfires requires territorial management strategies that integrate technological, environmental, and community dimensions, thereby shaping social representations of a territory that is still in the process of construction.

1.3. The Valparaíso Megafire of February 2024

The Valparaíso Region has historically been affected by wildfires. In particular, the municipalities of Valparaíso and Viña del Mar exhibit high vulnerability due to irregular land occupation, especially on hillsides and ravines where precarious settlements are located. These dwellings are highly exposed to fire hazards and lack adequate evacuation routes. Combined with institutional neglect, this situation resulted in none of the affected municipalities having an active Urban Regulatory Plan at the time of the megafire [

23]. The megafire that occurred between February 2 and 3, 2024, was the most devastating event recorded in the past 30 years, causing significant damage to both the population and infrastructure. The fire originated near Lake Peñuelas and spread rapidly towards the municipalities of Valparaíso, Viña del Mar, Quilpué, and Villa Alemana [

23]. It was brought under control on February 6, 2024, leaving a toll of 131 fatalities and more than 6,000 homes destroyed. According to Martínez et al. [

23], the affected area in the Valparaíso Region reached 9,215.9 hectares, affecting primarily forested areas (53%) and grassland-shrub ecosystems (39%). The damage assessment conducted across 136 evaluated sites identified 47 as critical infrastructure (34.6%), 38 as neighborhood or urban facilities (27.9%), and 51 as other categories, including destroyed residences in border areas (37.5%).

1.4. Media Representations of Risk

Historically, the term “natural disasters” has been commonly used; however, authors such as Hewitt [

24] argue that disasters are social constructions with political and cultural dimensions. Media outlets not only report on these events, but also shape their representation through discourses that combine scientific, common, and informational knowledge [

3,

25]. The media mold social representations of disasters, influencing public perceptions of risk and the role attributed to the state [

26]. Consequently, it becomes essential to examine how news spread through social networks and traditional outlets constructs the narrative of such events and their management phases.

In Spain, studies on the 2017 Galicia and Portugal wildfires revealed insufficient and alarmist media coverage of climate change, which obscured its anthropogenic origins [

27]. Similarly, Vázquez [

28] found that although the media tended to broadcast alarming images focused on the damage rather than its causes, differences in framing emerged depending on the outlet: El País adopted an institutional tone, while La Voz de Galicia relied on sensationalism. In the case of the Valparaíso megafire (February 2024), media coverage was intense and contributed to the social construction of the disaster, shaping public opinion regarding its prevention, suppression, and recovery [

29]. Therefore, this study seeks to describe how Chilean media outlets covered the megafire, with particular attention to its representation in the Valparaíso Region. To this end, we ask: What are the social representations of the Valparaíso megafire in Chilean media as reflected in their social media publications?

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological approach of this study is based on a multistage strategy for news analysis and classification, focusing on the social representations disseminated by media outlets. A mixed methods design is employed, combining manual and computational techniques to establish a sequence aimed at characterizing these representations on social networks. The purpose is to systematically examine how socio-natural disasters are portrayed within the Chilean information ecosystem, adopting a territorial perspective that considers the role of the media in disaster risk management. The proposed methodology constitutes an interdisciplinary framework of facilitation, triangulation, and methodological complementarity, as outlined by Leckner and Severson [

30], and involves three implementation stages. In the first stage, Facebook posts from media outlets published during the 2023–2024 wildfire season are collected. This process involves textual data mining from a selected set of Chilean media sources, accessing their posts through the CrowdTangle Research platform. Subsequently, a computational cleaning procedure is applied to the dataset, identifying and removing duplicate entries and posts unrelated to the study’s objectives. Finally, the sample is characterized using descriptive statistics. In the second stage, qualitative techniques are applied to analyze the media posts with the aim of identifying the social representations embedded in their content, taking into account both textual and visual elements. Deductive coding is employed as the primary qualitative analysis method, enabling the identification of categories and subcategories derived from the review of the publications. In the third and final stage, computational strategies are implemented to analyze the textual data of manually classified posts within each category. The objective is to describe posts related to socio-natural disasters during the 2023–2024 wildfire season. At this stage, statistical–computational natural language processing techniques are utilized to identify emerging topics in the documents, drawing on methods such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) [

31] and Word Embedding [

32].

2.1. Media Selection

The set of media outlets analyzed includes national, regional, and hyperlocal sources present on the social network Facebook, based on the following criteria:

The outlet must be officially registered in the media directory of the Dirección de Bibliotecas, Archivos y Museos (DIBAM).

The selection aims to ensure heterogeneity within the sample so that the data set is not only extensive but also diverse.

The final sample comprises media outlets that published content on Facebook between November 21, 2023, and March 21, 2024, corresponding to the 2023 - 2024 wildfire season.

2.2. Collection of Publications

This section describes the data collection process and the analytical methods employed. The study is based on articles from mass media outlets obtained through large-scale data extraction from 140 Chilean press sources. Previous research on media analysis has traditionally focused on national and regional print journalism [

33]. Although acknowledging the value of this approach, our proposal seeks to broaden the scope to include content disseminated by television and radio outlets. For this reason, we selected news units from social media, which allows us to encompass messages published by print, radio, and television media.

The news extraction process was carried out using the Queltehue tool [

34], an automated web crawler that accesses the Facebook accounts of 140 media outlets every 24 hours to retrieve their posted content, indexing it into a NoSQL database. Subsequently, the collected data were filtered using specific keywords or exact expressions, or by querying a predefined set of accounts. For this research, the applied exact expressions were:

"Incendios forestales" OR "incendios en viña del mar" OR "incendios en valparaíso" OR "megaincendio" OR "incendios en quinta región" OR "incendios en la quinta región" OR "incendios en la región de valparaíso" OR "prevención de incendios" OR "recuperación de incendios" OR "mitigación de incendios" OR "combate de incendios" OR "restauración de incendios"

Through this extraction process, we obtained 4,802 news items referring to wildfires in general between November 21, 2023, and March 21, 2024. This period was selected to allow analysis of wildfire news coverage before, during, and after the Valparaíso megafire. After the automated filtering of posts, a manual review was conducted to remove items referring to other types of fires. As a result, 981 publications were excluded because they referred to fires in other countries or to different types of incidents (mainly residential or industrial).

3. Results

In the news coverage of wildfires by Chilean media outlets, three distinct cycles were identified. The first cycle, spanning from November to December, focuses primarily on news related to the coordination and prevention of wildfires. Among the main recommendations during December are the suspension of fireworks displays during end-of-year celebrations and warnings concerning the risk of fires caused by the release of sky lanterns. Additionally, some reports recount narratives from the localities most affected during the previous season. Another dimension addressed is police reporting, which informs about the status of investigations and prosecution of wildfire-related crimes. Regarding imagery, when prevention is discussed, media outlets tend to display photographs of wildfire outbreaks to visually convey the disaster’s impact [

35]. Conversely, although scientists are frequently cited in prevention topics, only one article includes an image of a scientist.

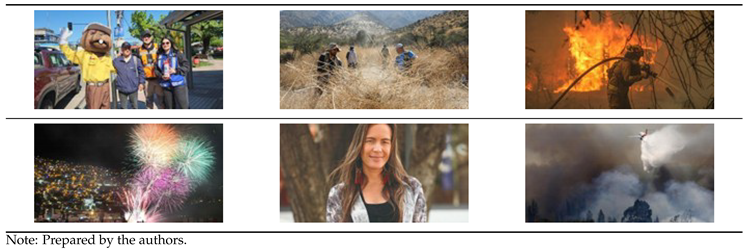

Table 1 presents examples of these media representations prior to the Valparaíso megafire, reflecting socially constructed representations of wildfire containment efforts (firefighters and aircraft) and prevention (the mascot Forestín and the construction of firebreaks).

The second cycle, beginning in January, expands coverage to include advisories targeted at residents and tourists, accompanied by imagery linked to preventive campaigns. The most frequent topics include the emergency alert system, weather conditions conducive to ignition, preemptive power outages, controlled burns, physical and mental health risks, pet safety, and patrols in high-risk zones. The most frequently mentioned entities are CONAF (National Forestry Corporation), SENAPRED (National Disaster Prevention and Response Service), and electrical utilities, often depicted in photographs of interagency meetings. However, the majority of news reports focus on the environmental impact of the various wildfire outbreaks, primarily accompanied by images of active fires [

35]. A limited presence of expert information is observed, with only two news items including images of scientists.

Table 2 provides examples of the imagery used during the mega-fire event, highlighting three representative categories: scientists, coordination meetings, and on-the-ground firefighting efforts.

The third cycle begins with the mega-fire in Valparaíso on February 2, which triggers a significant increase in media coverage, particularly within the environmental impact subcategory, with images documenting damage to natural ecosystems. The thematic categories also expand, incorporating news on social consequences, illustrated by photographs of destroyed homes and affected individuals. Additionally, there is a rise in depictions of social actors, primarily politicians and artists who supported victims during the Viña del Mar Festival.

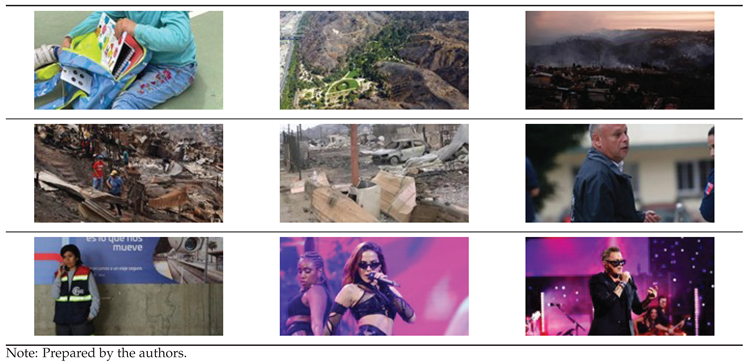

Table 3 provides examples of the imagery disseminated after the fire, highlighting representations of educational disruptions (a girl holding notebooks), biodiversity loss (Botanical Garden and hills), and infrastructure damage (houses and vehicles). Furthermore, political figures (the governor and mayor) and celebrities (Anitta and Alejandro Sanz) emerge as key figures in the recovery process.

3.1. News Analysis Categories

Three temporal phases were identified in the analysis of news coverage, corresponding to the stages of the wildfire management cycle: prevention, response, and recovery. In order to characterise the social representations disseminated by the media, analytical categories were defined based on key emerging topics identified in the literature, thereby linking media framing with the study of the phenomenon. During the manual review of news reports, additional emergent categories were identified, forming independent constructs related to media coverage of wildfires. These are detailed in

Table 4.

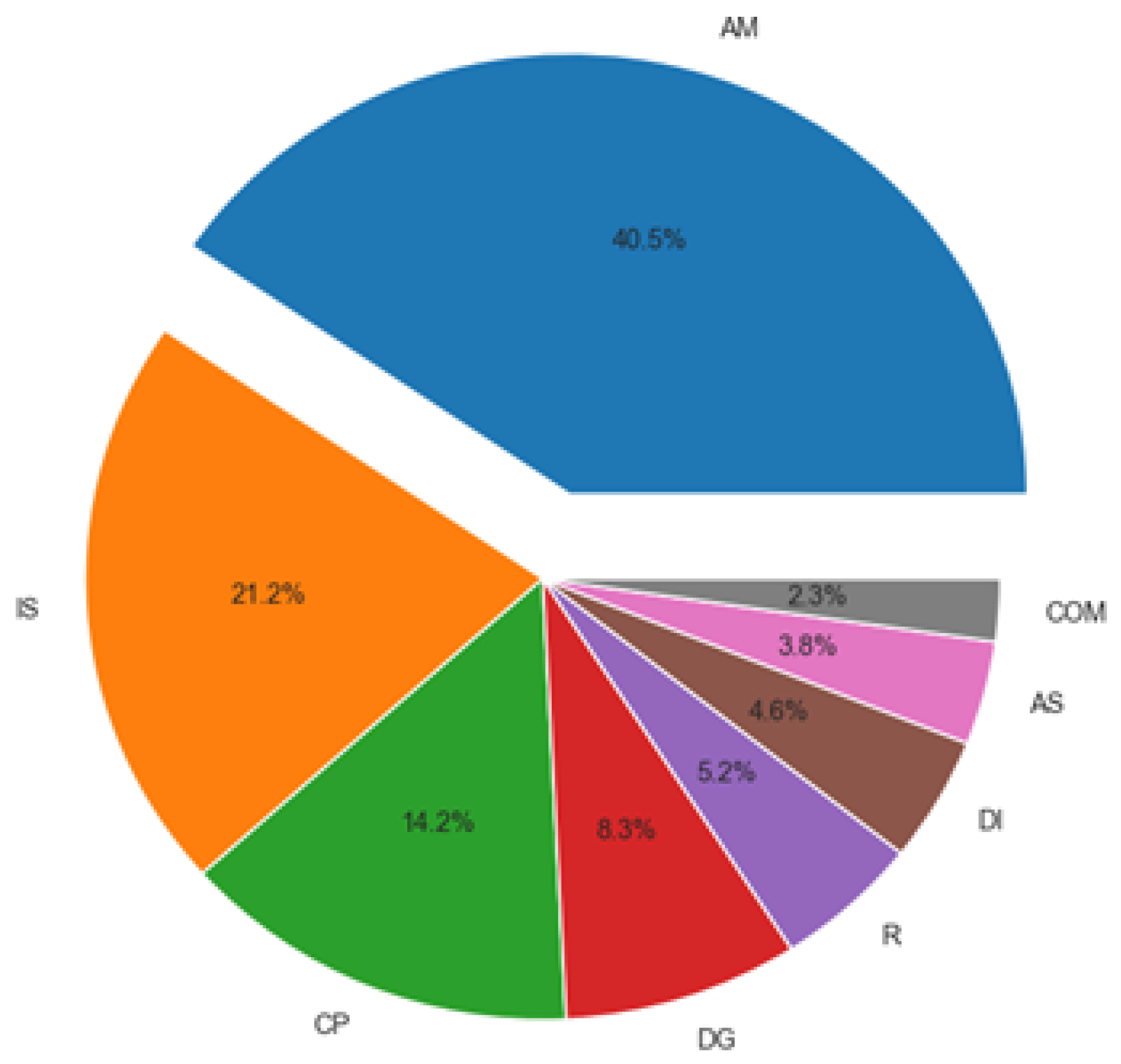

The categorization of publications reveals a predominance of social representations related to environmental impact (40.5%), followed by social and community impact (21.2%), demonstrating a clear tendency to emphasize wildfire effects on biodiversity and communities. In contrast, representations associated with firefighting efforts (2.3%) and social actors (3.8%) are the least frequent. The complete distribution of publications by category is presented in

Figure 1.

3.2. Coordination and Prevention (CP 14.2%)

This news category begins with reports focused on governmental coordination and wildfire prevention measures (n=115), including statements from President Gabriel Boric, cabinet members, and key institutions like CONAF and SENAPRED. Technical committees formed for risk-commune prevention are highlighted, comprising the Presidential Delegation, Public Order and Security Forces, SENAPRED, CONAF, and Chile’s Fire Department. The coverage details allocated prevention resources, including research funding, training programs, and equipment provision, with special emphasis on operational aircraft like the "Aero Tanker" and "Hercules" during fire season. Topics include agricultural burning restrictions, preventive campaigns for residents and tourists, animal welfare protocols, and preventive surveillance. News reports emphasize both invested resources and preemptive coordination between state and private entities (including power companies) for joint wildfire prevention, containment, and response. Among notable developments, government announcements about dedicated ecological recovery research funding for affected areas stand out. CONAF’s participation is prominent, with coverage focusing on previous season evaluation reports and 2023-2024 projections warning about potential simultaneous wildfire outbreaks. Automated analysis of these publications identified three latent topics (

Table 5) related to: Wildfire Prevention, Firefighting Coordination, Fire Spread Risk. This reveals a comprehensive approach encompassing both pre-event phases and active fire management.

3.3. Containment Efforts (COM 2.3%)

This category comprises initial news reports focused on wildfire containment operations by response agencies. Manual analysis identified three subcategories: Fire containment and progression, featuring minute-by-minute updates (n=76); Evacuation alerts and human rescue operations (n=29); Animal evacuation and rescue efforts (n=15). Automated content analysis revealed three emergent topics (

Table 6) aligning with manual subcategories, reflecting media representations associated with: Firefighting operations; Damage assessment by authorities; Social impact on affected communities.

3.4. Deficiencies in Emergency Management (DG 8.3%)

This category comprises news reports addressing shortcomings in emergency response, with manual analysis identifying three subcategories: Investigations into management failures (n=19); Political accountability, primarily focusing on criticism of Viña del Mar’s mayor regarding urban planning regulations and fatalities in the Botanical Garden fire (n=12); Broad critiques of government response, largely voiced by opposition politicians (n=41)

Automated content analysis reveals three predominant social representations (see

Table 7): Political accountability centered on the mayor and municipal government, the disaster’s unprecedented scale, and its hyperlocalized impacts.

3.5. Environmental Impact (AM 40.5%)

Manual analysis identified four wildfire representations related to environmental effects: affected areas (n=90) featuring real-time reports with aerial/satellite imagery of fire progression; biodiversity impacts (n=41); animal welfare consequences (n=7); climate change connections (n=6).

The most frequent subcategory was affected areas. Notably, animals were represented as rights-bearing subjects deserving disaster protection. Automated analysis revealed three media representations (see

Table 8): Human casualties in affected communities, Ongoing damage monitoring, and Biodiversity loss.

3.6. Social Actors (AS 3.8%)

Political figures -predominantly government officials (n=589)- emerged as the most frequently cited social actors in press coverage. Their presence remained constant from wildfire season preparedness through post-disaster phases, spanning: Institutional coordination, State-led relief efforts. This coverage primarily featured statements from: The President, Cabinet members, and Local authorities (Suggesting media prioritization of official disaster management narratives).

Expert participation ranked third (n=206), with consistent representation across all phases addressing: environmental damage assessments, predictive modeling, public health advisories, and animal welfare protocols.

Notable platform disparity: Experts appeared most frequently on radio programs (Universidad de Chile Radio, Bio Bio Radio), discussing ecological impacts, anthropogenic fire origins, and AI-enhanced early detection systems.

Phase-specific patterns: Celebrity/influencer mentions emerged (n=356), because of viral social media campaigns or proximity to Viña del Mar Festival (amplifying victim support initiatives). Affected communities: Minimal direct representation (n=114), but limited to first-person accounts, Aid requests.

Automated content analysis revealed three dominant social representations (

Table 9): presidential leadership, ministerial crisis response, and community organization roles.

3.7. Recovery Phase (R 5.2%)

This category is dominated by coverage of government-led recovery actions (n=336), including: Policy measures (e.g., reconstruction funding), Security interventions, Victim support programs. Secondary coverage features: Municipal initiatives (n=69), Private-sector efforts (n=40). Notably, NGO participation remains marginal (n=2).

Automated topic modeling reveals three emergent themes (see

Table 10): Geographic scope (regional/national impact assessment), Damage valuation as basis for recovery planning, Inter-regional comparisons of fire effects.

3.8. Wildfire-Related Crimes (DI 4.6%)

This category comprises news coverage on the investigation and prosecution of forest fire offenses. The majority of reports (n=90) reference the Public Prosecutor’s Office regarding: Progress in investigations from previous fire seasons, Arrests made during the 2023-2024 season. A secondary subset (n=70) covers ancillary offenses, including: Additional detainments, Victim reports of potential looting/fraud (Sources: Chilean Order and Security Forces + Armed Forces). Automated analysis reveals three dominant media representations (see

Table 11): Community vulnerability during emergencies, Investigative procedures into fire causes, Characterization of the alleged primary perpetrator.

3.9. Social and Community Impact (IS 21.2%)

This category encompasses the effects on individuals’ lives and community systems. The most covered subcategory was affected persons (n=297), including reports on fire-related fatalities. This was followed by community-led responses (n=240), focusing on solidarity campaigns, communal kitchens, and other victim-support initiatives. The third significant subcategory, service disruptions (n=63), played an informational role with respect to outages/restoration of: Basic utilities, public transport, canceled cultural/sporting events. The analysis reveals conceptual clusters reflecting: Impact Assessments: focusing on victim counts and human losses, Aid infrastructure: Representations of available relief centers/resources (see

Table 12).

4. Discussion

Consistent with the theory of social representations [

1], mass media actively construct social representations by anchoring elements within systems of social cognition. This function becomes critical in contexts of information overload, such as disasters, where selective information organization creates coherent representations responsive to historical and cultural contexts. Media coverage of the Valparaíso mega-fire exemplifies this process, shaping social representations of wildfires through culturally resonant mental imagery [

25]. This facilitates public identification with news content and the integration of media representations into individual social cognition. Notably, coverage prioritized landscape, human, and infrastructure damage – a strategy seemingly designed to align media representations with community experiences.

During the initial prevention and containment phases, media coverage constructs a representation of nature as governable by the State – a concept documented by Gould et al. [

26]. This representation becomes entrenched through reporting on: State-led prevention measures (interagency coordination, private sector partnerships); Official emergency protocols (evacuation orders, utility disruptions, crisis management).

At this stage, the news media serve as critical risk communication channels, particularly for unaffected regions by: Disseminating authoritative information, Reinforcing institutional credibility, and Framing disasters as controllable through state intervention.

As the wildfires in Valparaíso intensified, media constructed a dual representation of nature as an uncontrollable force and the state as a policing entity [

26], emphasizing restrictive measures (curfews, arson prosecutions) where authorities appeared as security providers while citizens were predominantly framed as demanding victims. Concurrently, an exceptional tragedy narrative became dominant [

28] through: (1) environmental coverage focused on biodiversity loss and damaged protected areas; (2) sensationalist reporting featuring daily victim counts and emotional testimonials; and (3) viral dissemination of dramatic aerial footage and user-generated content from affected individuals. While effective at generating social alarm, this approach systematically neglected structural causes (only 17% of the reports mentioned anthropogenic factors versus 83% limited to weather conditions), reducing wildfire understanding to isolated incidents and privileging reactive (police control) over preventive solutions. Image analysis revealed 72% of recovery-phase visuals featured security forces versus merely 11% including scientific experts, demonstrating a representational imbalance in media coverage.

Notably, media coverage systematically avoids in-depth examination of the climate change-wildfire nexus, limiting reporting to meteorological conditions favoring ignition (e.g., rising temperatures in vulnerable areas). This aligns with findings by Ripollés [

29] and Morote et al. [

27], who warn that climate change information remains insufficient and sensationalized, with digital media serving as primary sources for future educators, directly shaping public perception.

Yet an emerging science-based representation attributes most Chilean wildfires to anthropogenic causes [

7,

8], advocating state-citizen co-responsibility in prevention through agencies like CONAF and SENAPRED. This scientific-social convergence [

3] initially surfaced in reports emphasizing anthropogenic origins, though such representation diminished after megafire onset, displaced by conventional media tropes.

Automated topic modeling validated manual analysis: prevention-coordination coverage mirrored media framing patterns, while environmental impact topics precisely mapped manual subcategories (affected areas, victims, damage conditions). This methodological triangulation enhanced findings robustness.

5. Conclusions

The media play a pivotal role in constructing social representations of wildfires, employing imagery and narratives that resonate with the culture and emotions of affected communities. During the Valparaíso mega-fire, an evolution in these representations was observed: from a nature controllable by the State, to an overwhelming natural force and a policing State, and finally to a sensationalist approach emphasizing tragedy while overlooking structural causes like climate change.

Although an emerging representation integrating scientific knowledge and shared State-citizen responsibility did surface, it was ultimately overshadowed by more simplistic and alarmist narratives. The integrated manual-automated analysis confirmed the consistency of these findings, highlighting the media’s critical influence in shaping social perceptions of socio-natural disasters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V. and C.O.; methodology, M.V.; software, C.O. and L.C; validation, M.V. and C.O.; formal analysis, M.V.; investigation, M.V.; resources, L.C.; data curation, C.O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V.; writing—review and editing, C.O.; visualization, C.O.; supervision, M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moscovici, S. El psicoanálisis: su imagen y su público. In El psicoanálisis: su imagen y su público; Editorial Huemul, 1979; pp. 366–366.

- Jodelet, D.; et al. La representación social: fenómenos, concepto y teoría. Moscovici, Serge (comp.), Psicología Social II, Barcelona, Paidós.

- Bravi, C. Representaciones sociales de la inundación. del hecho físico a la mirada social. Redes. com: revista de estudios para el desarrollo social de la Comunicación.

- Castorina, J.A. La significación de la teoría de las representaciones sociales para la psicología. Perspectivas en psicología 2016, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gascón, M.; Ahumada, N.; Galdame, E. Percepción del desastre natural; Editorial Biblos, 2009.

- Luhmann, N. La realidad de los medios de masas; Vol. 40, Universidad Iberoamericana, 2007.

- González, M.; Sapiains, R.; Gómez-González, S.; Garreaud, R.; Miranda, A.; Galleguillos, M.; Jacques, M.; Pauchard, A.; Hoyos, J.; Cordero, L.; et al. Incendios forestales en Chile: causas, impactos y resiliencia. Centro de Ciencia del Clima y la Resiliencia (CR) 2020, 2, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo, R.A.; Galleguillos, M.; González, M.E.; Vásquez, F.; Arriagada, R. Assessing the socio-economic and land-cover drivers of wildfire activity and its spatiotemporal distribution in south-central Chile. Science of the total environment 2022, 810, 152002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, V.C.; Helmers, D.P.; Kramer, H.A.; Mockrin, M.H.; Alexandre, P.M.; Bar-Massada, A.; Butsic, V.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Martinuzzi, S.; Syphard, A.D.; et al. Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarricolea, P.; Serrano-Notivoli, R.; Fuentealba, M.; Hernández-Mora, M.; De la Barrera, F.; Smith, P.; Meseguer-Ruiz, Ó. Recent wildfires in Central Chile: Detecting links between burned areas and population exposure in the wildland urban interface. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 706, 135894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, M.; Ghodrat, M.; Sharples, J.J. LES simulation of wind-driven wildfire interaction with idealized structures in the wildland-urban interface. Atmosphere 2020, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, R.; Borsdorf, A.; Plaza, F. Parcelas de agrado alrededor de Santiago y Valparaíso:?` Migración por amenidad a la chilena? Revista de Geografía Norte Grande. [CrossRef]

- Norman, S.P.; Christie, W.M. Precise mapping of disturbance impacts to US forests using high-resolution satellite imagery. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-266, chapter 6 2022, 2022, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino, G.; Fuentes, A.; Valdivia, A.; Auat-Cheein, F.; Reszka, P. Assessing wildfire risk to critical infrastructure in central Chile: application to an electrical substation. International Journal of Wildland Fire 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A.R.; Helmers, D.P.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Mockrin, M.H.; Radeloff, V.C. The wildland–urban interface in the United States based on 125 million building locations. Ecological applications 2022, 32, e2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, G.C.L.; Prince, S.E.; Rappold, A.G. Trends in fire danger and population exposure along the wildland–urban interface. Environmental science & technology 2021, 55, 16257–16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Tangarife, C.; Burrows, A.S.; Peñaloza, J.O.; Guajardo, F.J. Tipología funcional para áreas naturales protegidas: ruralización y urbanización en la zona central de Chile. Cuadernos de Geografía: Revista Colombiana de Geografía 2023, 32, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo, F.J.; Burrows, A.S.; Montoya-Tangarife, C. Nexos espacio-temporales entre la expansión de la urbanización y las áreas naturales protegidas. Un caso de estudio en la Región de Valparaíso, Chile. Investigaciones Geográficas 2017, 54, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Muñoz, A.; del Río, C.; Leguia-Cruz, M.; Mansilla-Quinones, P. Spatial dynamics in the urban-rural-natural interface within a social-ecological hotspot. Applied Geography 2023, 159, 103060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumelzu, M.S. Migración por estilos de vida y tensiones socioterritoriales: El caso de Villarrica-Pucón en un horizonte post pandemia. PhD thesis, Tesis de Magíster en Asentamientos Humanos y Medio Ambiente]. Repositorio …, 2021.

- Gosnell, H.; Abrams, J. Amenity migration: diverse conceptualizations of drivers, socioeconomic dimensions, and emerging challenges. GeoJournal 2011, 76, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, G.; Castillo, B.; Steiniger, S. Envejecer en la playa. La emergente migración de personas mayores hacia el Litoral Central de Chile (1987–2017). AUS-Arquitectura/Urbanismo/Sustentabilidad. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.; León, J.; Bonet, M.; Inzunza, S.; Guerrero, N.; Román, R.; Acevedo, R.; Araya, E. Incendios 02 y 03 de febrero de 2024, Viña del Mar (Región de Valparaíso). Technical report, CIGIDEN, 2024.

- Hewitt, K. Excluded perspectives in the social construction of disaster. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters 1995, 13, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verón, E. Prefacio” e “Introducción” en Construir el acontecimiento. Los medios de comunicación masiva y el accidente en la central nuclear de Three Mile Island; Gedisa. Buenos Aires, 1987.

- Gould, K.A.; Garcia, M.M.; Remes, J.A. Beyond" natural-disasters-are-not-natural": the work of state and nature after the 2010 earthquake in Chile. Journal of Political Ecology 2016, 23, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morote, Á.F.; Campo, B.; Colomer, J.C. Percepción del cambio climático en alumnado de 4º del Grado en Educación Primaria (Universidad de Valencia, España) a partir de la información de los medios de comunicación. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, E.C. Comunicación de crisis: fake news y seguimiento informativo en la ola de incendios de Galicia en octubre de 2017. Revista Española de Comunicación en Salud. [CrossRef]

- Ripollés, A.C. El control político de la información periodística. Revista latina de comunicación social 2009, 12, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckner, S.; Severson, P. Exploring the meaning problem of big and small data through digital method triangulation. Nordicom Review 2019, 40, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of machine Learning research 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhou, H.; He, J.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Li, L. On the sentence embeddings from pre-trained language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.05864, arXiv:2011.05864 2020. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, S.; Enander, A. “Damned if you do, damned if you don’t”: Media frames of responsibility and accountability in handling a wildfire. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 2020, 28, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárcamo-Ulloa, L.; Cárdenas-Neira, C.; Scheihing-García, E.; Sáez-Trumper, D.; Vernier, M.; Blaña-Romero, C. On politics and pandemic: how do Chilean media talk about disinformation and fake news in their social networks? Societies 2023, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisóstomo Flores, P.; Rosique Cedillo, G. La cobertura informativa de la televisión pública chilena (TVN) sobre acontecimientos imprevistos: el caso de los incendios forestales. Anàlisi: quaderns de comunicació i cultura, 0085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).