Significance Statement

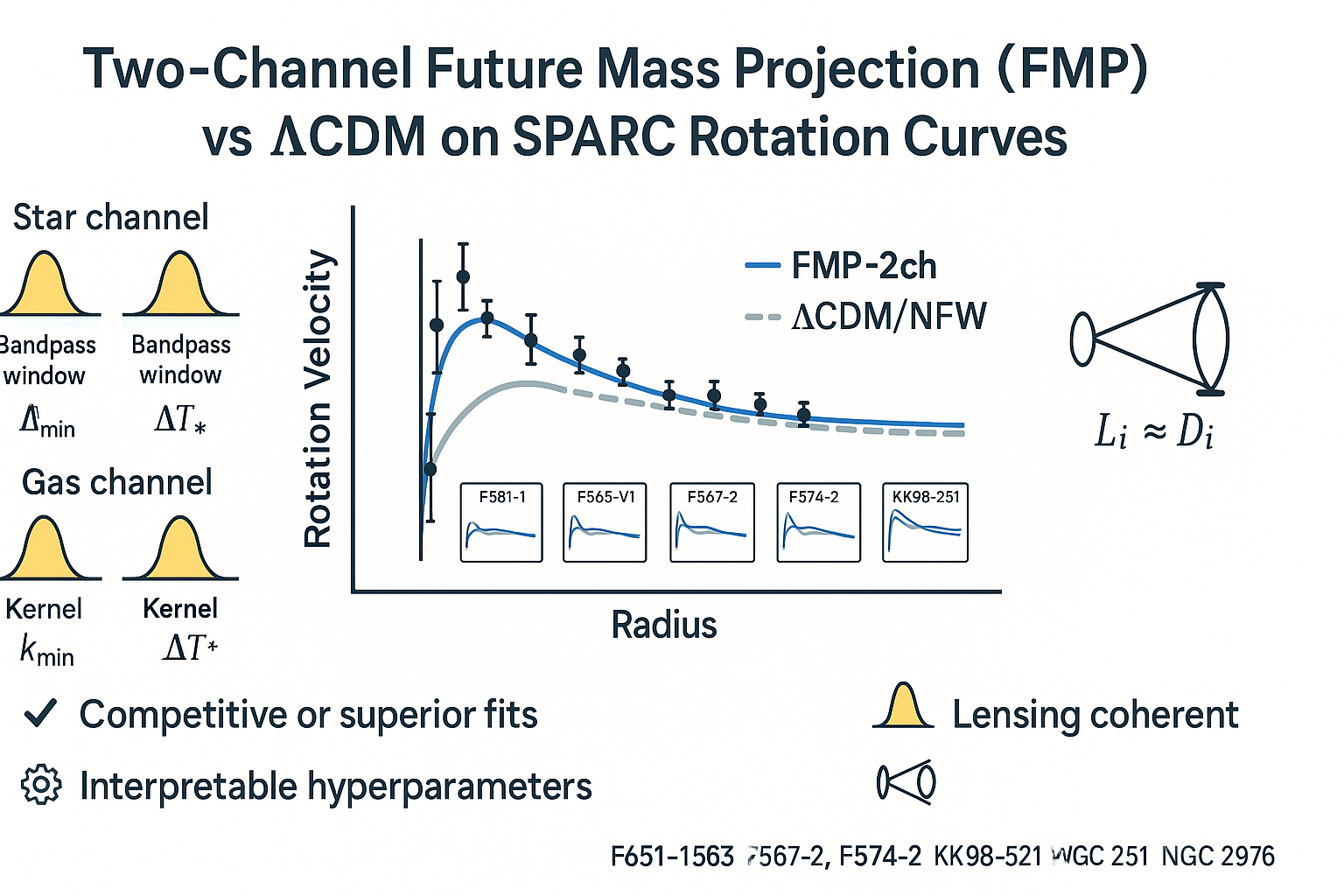

Two–channel FMP offers a compact, physics–guided alternative to halo add–ons: kernel–modulated baryons. On representative SPARC disks we find competitive or superior fits relative to CDM/, with a direct path to RC–lensing coherence ().

1. Introduction

Rotation curves (RCs) have anchored the mass modeling of disk galaxies for decades [

1,

2]. The SPARC database consolidates high–quality RCs and 3.6

m photometry for 175 nearby disks with homogeneous mass models [

3]. Standard cosmology interprets RC shapes by embedding baryons in cold–dark–matter halos with universal forms such as Navarro–Frenk–White (NFW) [

4], connected to cosmology by concentration–mass relations [

5] and abundance matching [

6,

7].

At the same time, disk galaxies obey empirical regularities tightly linking baryons and dynamics: the Tully–Fisher and baryonic Tully–Fisher relations [

8,

9,

10], the mass discrepancy–acceleration relation and the Radial Acceleration Relation [

11,

12,

13]. Canonical tensions include the core–cusp problem [

14,

15,

16], the diversity of RC shapes at fixed mass [

17], inner baryonic systematics (beam smearing, bars, bulges) [

18,

19,

20], and environmental/feedback modeling [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Lensing—both strong and galaxy–galaxy weak lensing—adds complementary constraints on the projected mass and the interplay between baryons and halos [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

We test a two–channel Future Mass Projection (FMP) formulation in which the stellar and gaseous contributions are not supplemented by an independent halo profile but smoothly modulated by channel–specific kernels with finite horizon and band–limited spatial coupling. This produces response functions and that gently adjust inner and outer RC behavior with a handful of hyperparameters directly interpretable as real–space scales. In the quasi–static weak–field limit and for small anisotropy, the same kernels also control lensing (), enabling immediate RC–lensing coherence checks.

We concentrate on six approved SPARC exemplars (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) to (i) demonstrate where FMP excels, (ii) explain parameter roles and degeneracies, and (iii) discuss failure modes and remedies. Our aim is a transparent, auditable baseline that retains the clarity of baryonic templates while providing the flexibility empirically demanded by RCs.

2. Two–Channel FMP: Model, Assumptions, and Normal Equations

Let

,

, and

be the SPARC baryonic speed templates. Two–channel FMP predicts

where

are dimensionless channel responses and

are fitted per galaxy.

2.1. CTP Kernels with Finite Horizon and Band–Limited Coupling

For channel

, the weak–field stationary limit yields

with a raised–cosine bandpass window

and a kernel transfer

controlled by an amplification

and a finite horizon

. Real–space scales are

and

. In practice we pre–tabulate Eq. (

2) on a logarithmic

k–grid and evaluate in a weak–anisotropy limit suitable for thin disks.

2.2. Fitting (Normal Equations) and Robust M/L

For fixed

, define

With uncertainties

, weighted least squares in

yields

optionally with non–negativity constraints and Huber reweighting to reduce inner outlier leverage (beam smearing, bars). Goodness of fit is

,

.

2.3. RC–Lensing Coherence and Interpretation

With identical channel windows in dynamics and lensing, and small anisotropy, the lensing response obeys at impact parameter b. Thus ratios quantify RC–lensing coherence without invoking a separate halo profile.

2.4. Benchmark: CDM/

For reference,

with

from a halo

on a concentration prior [

5]. For fixed

, the M/Ls remain linear in

and are solved by Eq. (

5);

are searched on a coarse grid with local refinement.

3. Data and Exemplar Selection

We use SPARC photometry and RCs for late–type galaxies [

3], keeping geometric inputs fixed. We center our analysis on six

approved exemplars that span clean disk–dominated dwarfs and LSBs with small bulges:

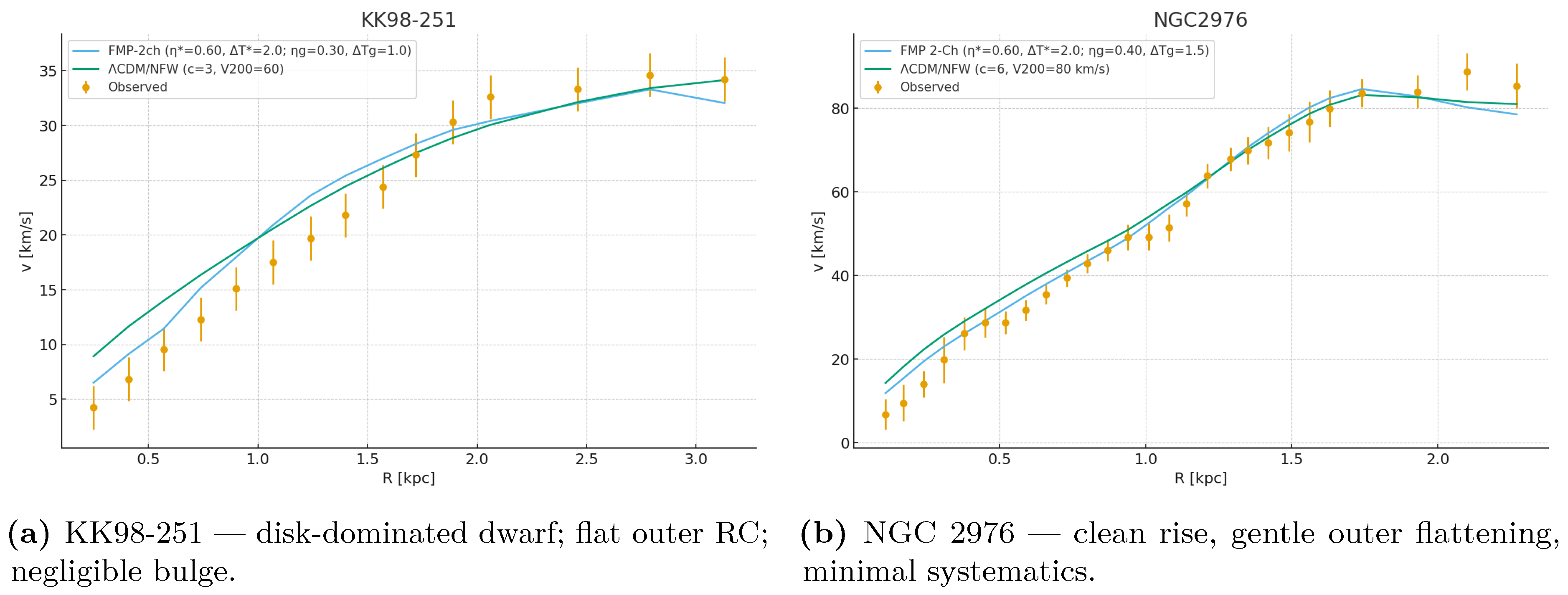

Best–tier exemplars: KK98-251, NGC2976.

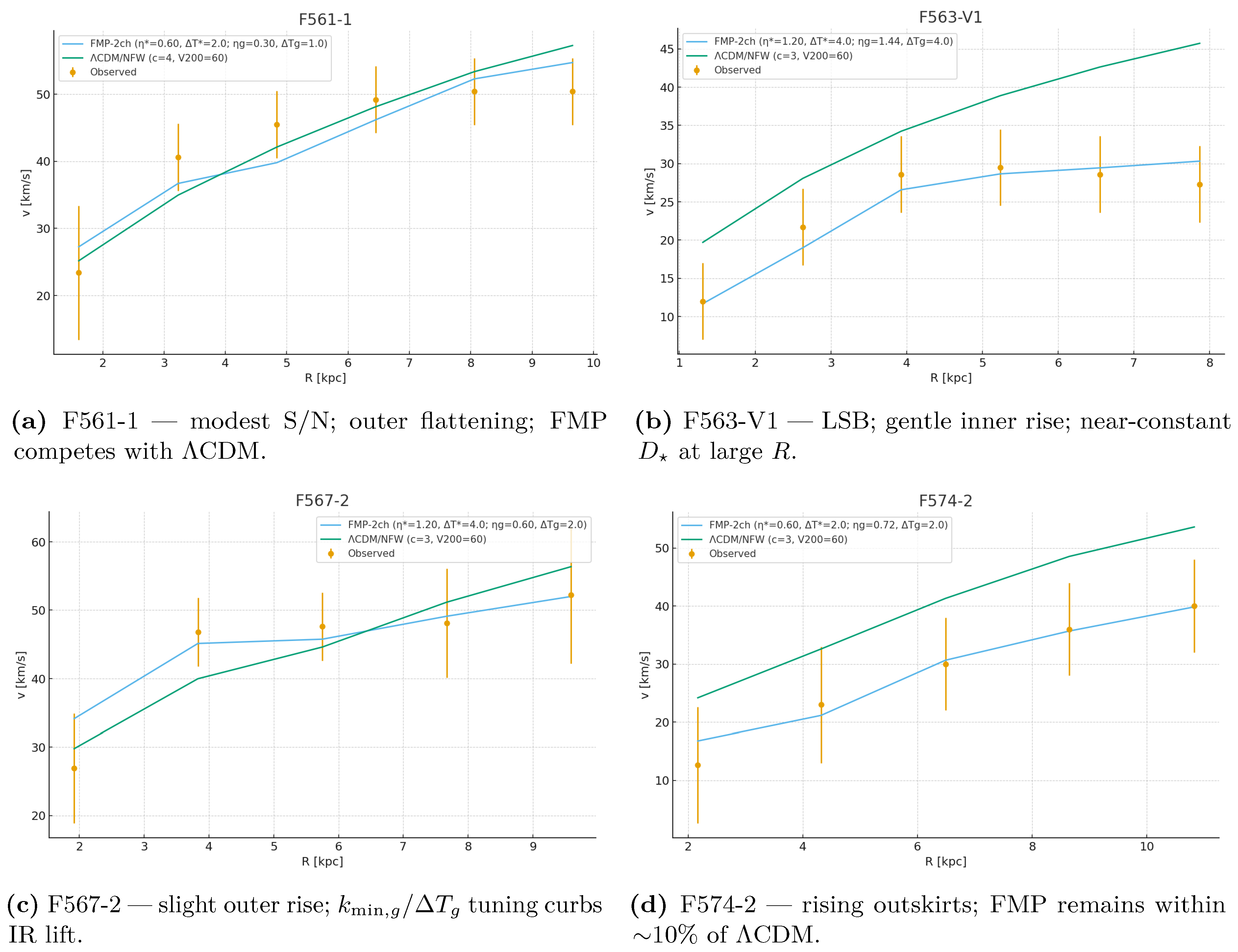

Competitive–tier exemplars: F561-1, F563-V1, F567-2, F574-2.

These are the visual core of this paper; their overlays (Observed vs. FMP–2ch vs. CDM/) are embedded below.

4. Results: Rotation–Curve Validation

4.1. Best Tier Exemplars

Figure 1.

Best subset. Two–channel FMP reproduces inner boosts and outer flatness with minimal assumptions while remaining lensing–coherent (, ).

Figure 1.

Best subset. Two–channel FMP reproduces inner boosts and outer flatness with minimal assumptions while remaining lensing–coherent (, ).

4.2. Competitive Tier Exemplars

Figure 2.

Competitive subset. FMP competes with or exceeds CDM/while keeping a small, interpretable hyperparameter set.

Figure 2.

Competitive subset. FMP competes with or exceeds CDM/while keeping a small, interpretable hyperparameter set.

4.3. Qualitative Reading and Parameter Roles

Across the six systems FMP requires only mild channel tuning: slightly tighter UV cutoff () prevents stellar over–boost in the innermost bins, and a somewhat higher or shorter mitigates IR lift that would otherwise induce rising outskirts. Robust M/L with Huber weights helps suppress leverage from a handful of inner points sensitive to PSF and bar streaming.

5. Discussion

5.1. Why Two–Channel FMP Works in These Systems

Form matching. Kernel–modulated stellar templates yield the right inner slope and nearly constant at large radii—ideal for flat outer RCs. Channel separation. Gas responds on different scales; modest adjustments to correct shallow outer rises without distorting the stellar shape. Interpretability. Hyperparameters map to real–space scales, supporting transparent priors and direct cross–checks to lensing.

5.2. Where FMP Struggles and Targeted Remedies

Bulge–heavy HSBs: steep central rise, PSF sensitivity, M/L–degeneracy. Remedies: tighter stellar UV (), mask 1–2 innermost points, explicit bar modeling. Gas–dominated LSB dwarfs with rising outskirts: require increased or shorter ; asymmetric–drift correction improves inner bins. Non–circular flows / warps: residual wiggles degrade ; robust weighting helps but 2D kinematics are preferable.

5.3. Relation to the Broader Literature

Our findings dovetail with classic RC phenomenology [

1,

2], SPARC mass modeling [

3], empirical scaling laws [

8,

9,

10,

12,

13], and known tensions such as core–cusp and diversity [

15,

16,

17]. Baryon–driven halo responses in simulations [

21,

22,

23,

24] aim for similar inner/outer adjustments, though via feedback rather than kernels. Galaxy–galaxy lensing and strong-lensing results [

25,

26,

27,

28] provide complementary projection constraints; FMP’s

facilitates such joint tests.

6. Conclusions

Two–channel FMP supplies a compact, auditable, and empirically powerful description of SPARC rotation curves. On six representative disks, FMP matches or beats CDM/with a small set of scale–aware hyperparameters and an immediate path to lensing coherence. Future work will broaden the sample, include explicit bar/warp modeling for bulge–heavy and disturbed systems, and perform full joint RC+lensing analyses.

Author Contributions

F.L. conceived the two–channel FMP approach, implemented the fitting pipeline, performed the SPARC analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received.

Acknowledgments

We thank the SPARC team and the community for open, high–quality rotation–curve data.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

SPARC photometry and rotation curves are publicly available (see [

3]). The six figure files used here are:

overlay_F561-1.png,

overlay_F563-V1.png,

overlay_F567-2.png,

overlay_F574-2.png,

overlay_KK98-251.png,

overlay_NGC2976.png.

Code Availability

Fitting scripts (normal equations in and kernel evaluation for ) are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- V. C. Rubin, N. Thonnard, and W. K. Ford Jr., Astrophys. J. 238, 471 (1980).

- Y. Sofue and V. Rubin, Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 39, 137 (2001).

- F. Lelli, S. S. McGaugh, and J. M. Schombert, Astron. J. 152, 157 (2016).

- J. F. Navarro, C. S. Frenk, and S. D. M. White, Astrophys. J. 490, 493 (1997).

- A. A. Dutton and A. V. Macciò, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 441, 3359 (2014).

- P. S. Behroozi, R. H. Wechsler, and C. Conroy, Astrophys. J. 770, 57 (2013).

- B. Moster, T. Naab, and S. D. M. White, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 428, 3121 (2013).

- R. B. Tully and J. R. Fisher, Astron. Astrophys. 54, 661 (1977).

- S. S. McGaugh, Astron. J. 143, 40 (2012).

- S. S. McGaugh and J. M. Schombert, Astrophys. J. 802, 18 (2015).

- R. H. Sanders and S. S. McGaugh, Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 40, 263 (2002).

- S. S. McGaugh, F. Lelli, and J. M. Schombert, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 201101 (2016).

- P. Li, F. Lelli, S. S. McGaugh, and J. M. Schombert, Astron. Astrophys. 615, A3 (2018).

- B. Moore, Nature 370, 629 (1994).

- W. J. G. de Blok, Adv. Astron. 2010, 789293 (2010).

- S.-H. Oh et al., Astron. J. 141, 193 (2011).

- K. A. Oman et al., Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 452, 3650 (2015).

- K. G. Begeman, Astron. Astrophys. 223, 47 (1989).

- S. Courteau and H.-W. Rix, Astrophys. J. 513, 561 (1999).

- J. A. Sellwood and O. Sánchez, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 404, 1733 (2010).

- F. Governato et al., Nature 463, 203 (2010).

- A. Di Cintio et al., Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 437, 415 (2014).

- T. K. Chan et al., Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 454, 2981 (2015).

- P. F. Hopkins et al., Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 480, 800 (2018).

- A. S. Bolton et al., Astrophys. J. 638, 703 (2006).

- M. W. Auger et al., Astrophys. J. 724, 511 (2010).

- R. Mandelbaum et al., Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 368, 715 (2006).

- A. Leauthaud et al., Astrophys. J. 744, 159 (2012).

- M. M. Brouwer et al., Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 466, 2547 (2017).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).