1. Introduction

Oil palm plays a vital role in worldwide, providing an essential source of cooking oil and vegetable protein for human and animal use. It is an excellent oil for deep frying as the fruit mesocarp contains 50% oil content with a high amount of saturated fat, particularly palmitic and stearic acids [

1]. Kernels from palm trees produce a lower-quality oil, which is primarily used in the production of soap as well as an ingredient in cosmetics. When compared to other tropical industrial crops, oil palm offers greater profits to farmers, thus making it more desirable. Two cultivated species make up the genus or Class Elaeis:

Elaeis guineensis Jacq. and

Elaeis oleifera (Kunth) Cortés, both of which can cross through natural or artificial methods of hybridization. The

E. guineensis species is from Western and Central Africa, while

E. oleifera is from South America [

1]. There are numerous problems related to the research and production of oil palm. The oil palm seed germination process is infamously known for its low success rates and the years it takes to mature, as it grows in stages from seedling to establishment. In addition, plants are very vulnerable to infestations by insects and pathogens, as well as drought stress, thus making them susceptible to losses during the early phases of development.

It is a multifaceted process based on several ambitious breeding objectives, including heterosis, disease resistance, modification of fatty acid profiles, environmental stress tolerance, and adaptability. However, achieving these objectives is unlikely without adequate genetic variability. Conventionally, oil palm is improved through reciprocal recurrent selection, in which individual plants are selected within each group, such as Dura and Pisifera. Selected individuals are also evaluated for their ability to combine through progeny testing. Superior plants are crossed to develop “tenera” hybrids with better oil content. A selection gain of 18% per cycle has been observed in reciprocal recurrent selection. Germplasm resources have been evaluated based on morphological traits, such as fruit shell forms (thin, thick), exocarp color, and plant characteristics; i.e., plant height and fruit bunches related to oil palm improvement [

2]. Traits such as rachis length and nut mass exhibit high heritability (60%) and can be effectively utilized as selection criteria, as they also display a high coefficient of variability (0.72) [

3]. MOPB-Angula germplasm exhibits high genetic variability in terms of bunch yield and oil quality components [

4]. There is considerable variability in these traits, and "Dura" progenies, such as AGO 02.02, exhibited the highest fresh fruit bunches (240 kg tree

-¹) and oil yield (29.46 kg tree

-¹) [

4]. The genetic gain for fresh fruit bunches and the number of bunches per plant was 19% [

5].

Elite germplasm resources enable rapid improvement of the species by expanding yield potential and other desirable traits, such as early maturity, increased fruit-bearing branches, a higher proportion of mesocarp in the fruits, the number of fruits per bunch, and higher oil content. However, breeding goals such as host plant resistance to pathogens and insects, as well as growth modifications require the exploitation of secondary and wild germplasm of oil palm. E. oleifera is used as a parental species for improving host plant resistance to pathogens; however, this species is not cultivated on a large scale due to its poor yield potential (i.e., less than 1 t ha ¹, compared to 3–4 t ha-¹ for E. guineensis). The widespread cultivation of a single genotype has led to disease epidemics, necessitating the exploitation of novel genetic resources to enhance the oil palm species.

Between 1970 and 2000, oil palm breeding benefited from the use of genetic resources, resulting in disease-resistant germplasm, particularly against Fusarium wilt, and dwarf genotypes. During this period, there was a 42% increase in the utilization of genetic diversity within oil palm germplasm in various breeding programs across Africa and South America.

African genetic resources have contributed to the development of dwarf types (from Nigeria), large dura fruit [

6], and improvements in iodine value and oleic acid content during the second and third breeding cycles [

7] . Genetic diversity within Nigerian germplasm was assessed using simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers. Genetic differentiation among germplasm populations was moderate (Fixation term, FST = 0.12), and a core germplasm subset of 58 oil palm accessions was identified, representing 31% of the genetic diversity in Nigerian germplasm [

8]. Germplasm from Tanzania has contributed to favorable traits, including a high harvest index, thin-shelled tenera, and high fruit bunch yield [

6,

9,

10].

The germplasm resources of oil palm have been harnessed to introgress valuable traits, including dwarf types, long rachises, host plant resistance to pathogens, superior yield components, and enhanced oil characteristics. Ongoing exploitation and utilization of genetic resources will further support breeding new ideotypes with improved resistance to stress factors and enhanced adaptability to evolving farming systems. However, to fully realize the benefits of these germplasm resources, it is essential to implement effective conservation strategies across diverse systems, ensuring their long-term sustainability and enabling their continued use in future breeding programs.

2. Integration of Ex Situ Germplasm Resources with In Vitro Conservation Strategies

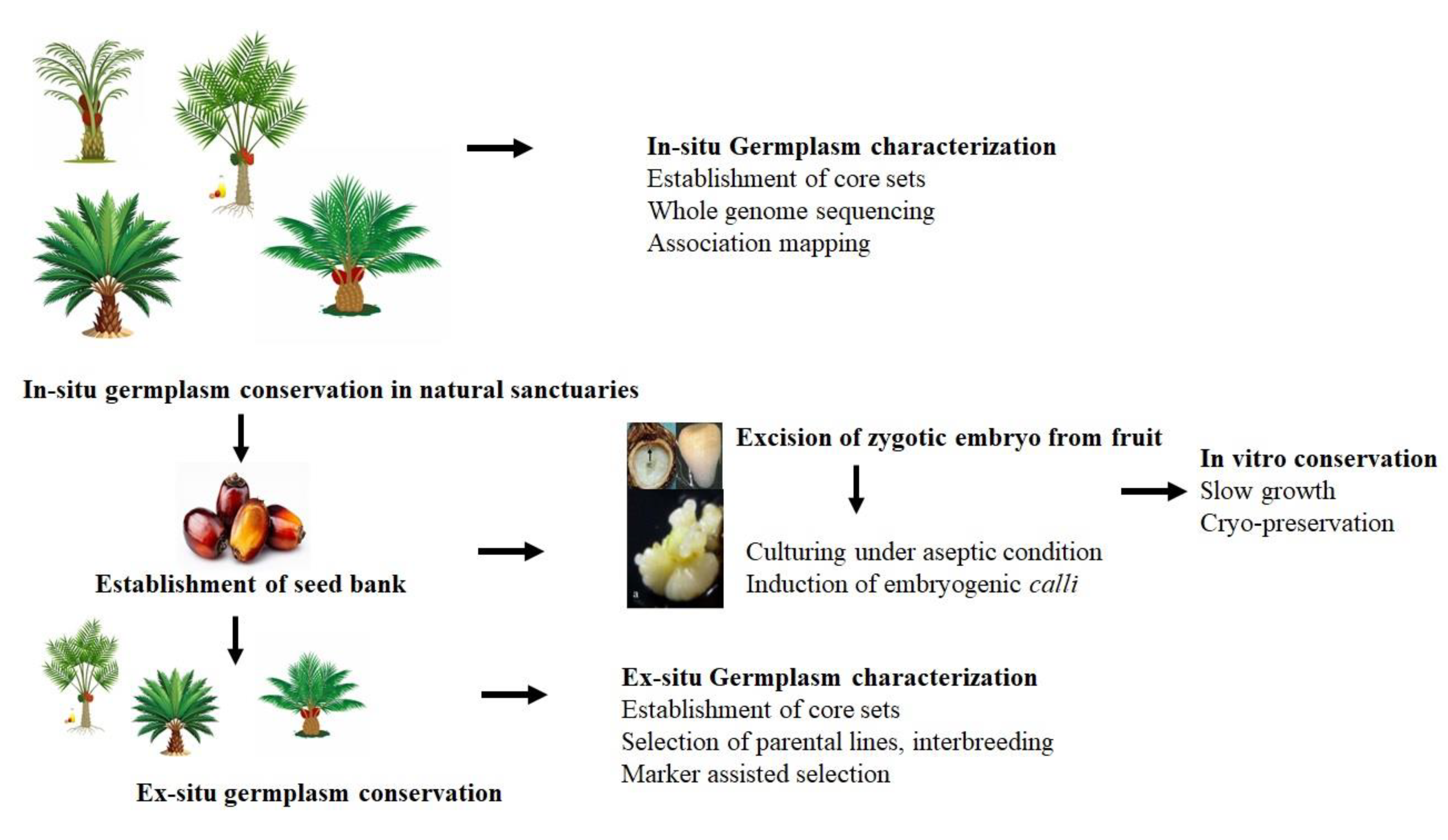

Conserving oil palm germplasm resources is crucial for preserving genetic diversity and ensuring the crop's long-term sustainability in the current global climate change scenario. Traditionally, germplasm has been conserved in natural sanctuaries or field banks (

Figure 1). Genetic diversity within these conserved sites is assessed using various morphological and molecular markers to determine the magnitude of genetic variation. This information helps formulate future strategies for conserving, utilizing, and managing oil palm germplasm resources.

Diversity within oil palm germplasm has been assessed using isozymes, which revealed high genetic differentiation (FST = 0.301) among West African germplasm [

11]. The genetic diversity of oil palm populations conserved as “ex-situ” sources decreased from Costa Rica towards Honduras and southeast Colombia [

12]. Alternatively, germplasm may be stored under in vitro conditions, and seed banks may be set up for early and mid-term conservation depending on the seed desiccation level and storage temperature. Seed storage also poses several challenges, such as the need to regenerate fresh seed at regular intervals, loss of viability due to poor seed stability, and changes in allele frequency caused by repeated germplasm cultivation.

Molecular markers were used to determine population structure; specifically, genetic differentiation was estimated with EST equal to 0.25 [

12]. A genetic distance of 0.77 was observed in a study involving a germplasm collection from 10 African countries (3 breeding populations and 1 semi-wild population), assessed through SSR analysis [

2,

13]. This study identified the genotypes from Madagascar as genetically distinct from those in other regions, such as Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire [

13]. The populations were distinct, indicating potential diversity and independent evolutionary histories. Human activities and environmental factors significantly affect these African wild populations, and ongoing destruction from biological or ecological influences could reduce the genetic diversity of wild African oil palm populations. The “Deli” population was also genetically different from the African populations. Breeding value, related to hybrid breeding and heterosis can be estimated by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based genetic distance among populations.

Germplasm in situ conservation has several challenges including spatial growth constraints, urban expansion, land deterioration, extreme temperature, unpredictable rainfall, climate change, and the accelerated onset of diseases and pest at collection sites [

8]. Ex-situ conservation also has problems, including purchasing land and other resources like agronomic management and farming practices which increases total spending. Germplasm can be stored for years using sterilized conditions in various tissue forms like meristematic tissues, calli, somatic embryos, and zygotic embryos. Such recovery methods take sophisticated biological skills and more sophisticated research facilities. The in vitro preservation of plant genetic resources involves the preservation of cell lines, tissues, meristems, somatic embryoids, zygotic embryos, micro-shoots, and pollen. It may need few months to several years of storing in sterile conditions [

14]. Nevertheless, some species need to improve in vitro conservation protocols for them to be effective [

15]. These conserved tissues are pest free and safe to be moved under phytosanitary rules [

16]. This shows that implementing in vitro germplasm conservation with the cryopreservation technique may help in avoiding genetic erosion and save the genetic resources of palms. Both methods could help to conserve plant germplasm under safe environment and could store germplasm for several years. However, the procedures involved in the in vitro and cryopreservation are expensive, require infrastructure and expertise and continues supply of expendables.

This review aims to provide an overview of the important steps and advances in the conservation of in vitro techniques and cryopreservation of oil palm germplasm. Additionally, this review provides insights into the challenges and the development of new protocols that could be successfully applied for the conservation of many germplasm accessions.

4. In Vitro Conservation and Plant Tissue Culture

In vitro conservation techniques are based on tissue culture protocols that enable the regeneration of pathogen-free plants from meristems or polyembryoids under aseptic conditions. These tissue culture protocols are aseptic methods of clonal propagation, allowing the regeneration of virtually any genotype through totipotent cells, tissues, or organs. In this process, cultured explants form an undifferentiated mass of cells known as 'calli.' The regeneration of plants from calli occurs through a process called 'somatic embryogenesis,' where embryogenic calli are induced using specific concentrations of nutrient media and plant growth regulators. Optimized culture media and growth conditions facilitate the development of heart-shaped structures known as 'somatic embryos. These somatic embryos mature, germinate, and produce viable shoots, thereby completing the regeneration process. A key prerequisite for in vitro conservation is the optimization of a highly efficient and regenerable protocol through somatic embryogenesis. Different explants and media protocols were optimized to obtain regeneration through somatic organogenesis in the optimized oil palm tissue culture [

18]. Somatic embryogenesis is influenced by genotype rather than by the concentration of the media, plant growth regulators, or types of explants, which is a major impediment to germplasm conservation, highlighting the need to develop a genotype-independent regeneration protocol to ensure the successful conservation of diverse germplasm sets [

19]. Alternatively, oil palm has been proposed for direct regeneration to simplify the procedure, potentially bypassing the need for callogenesis by regenerating shoots directly from the explant [

20,

21,

22].

Several types of explants, such as zygotic embryos, leaves, and inflorescences, have been used in tissue culture, each with a different success rate. Zygotic embryos, for example, are known for their high callus induction percentage. However, zygotic embryos may not guarantee 100% genetic fidelity to their maternal plants. Recently, a protocol for callus induction and somatic embryogenesis from various explants has been published [

18]. In this study, explants were obtained from the heart of the palm, and different leaf segments (L1–L8) were inoculated onto growth media. Leaf segments (L2–L8) exhibited a 10% callus formation rate, whereas somatic embryoids incubated in the RITA bioreactor with suitable plantlet regeneration growth media achieved a success rate of 5% [

18]. Embryogenic calli containing polyembryoids are subjected to in vitro conservation through slow growth or cryogenic preservation (

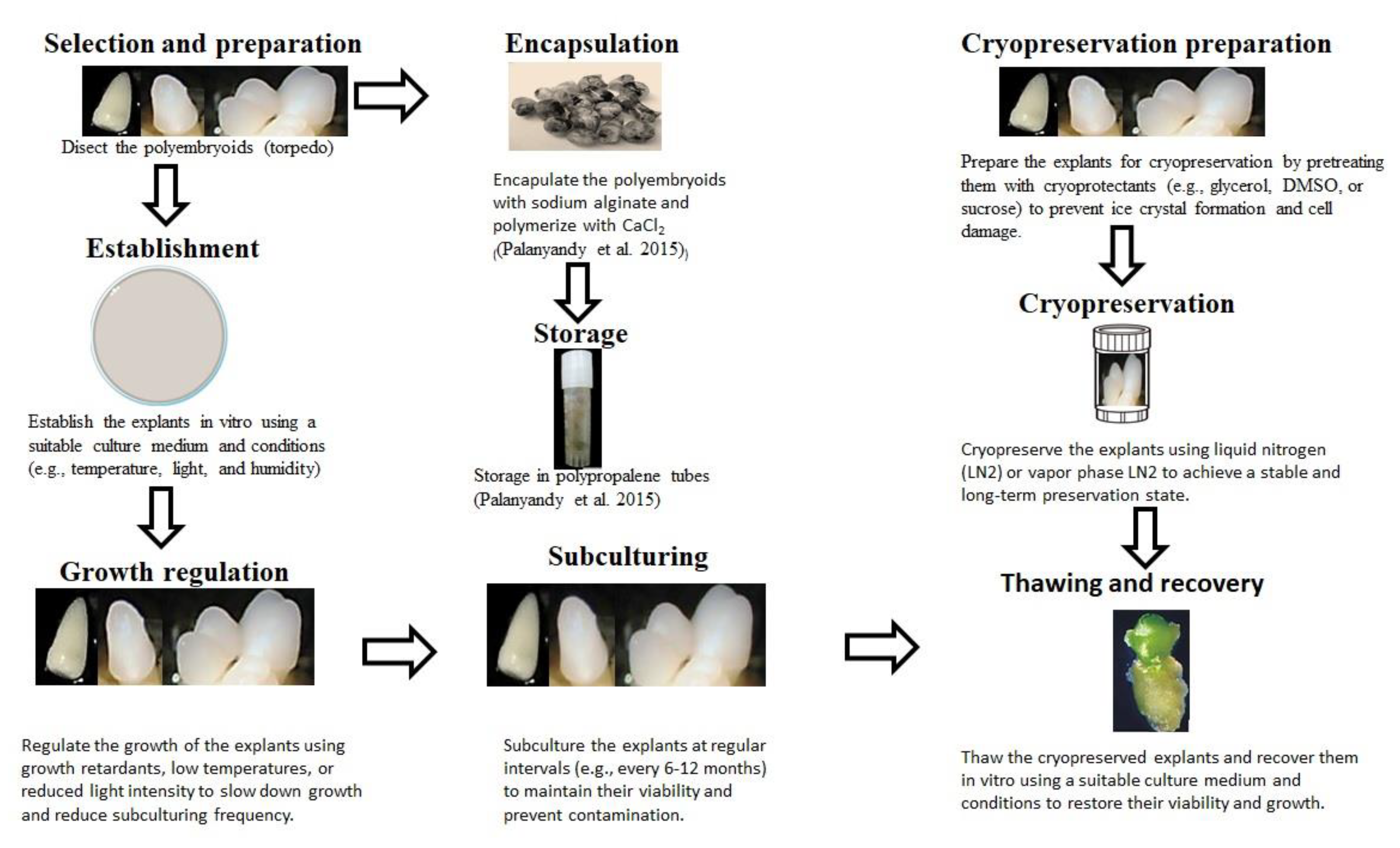

Figure 2).

A variety of calli, including compact granular and compact green, can be obtained from various concentrations of growth media and plant growth regulators. Calli are proliferated in suspension or bioreactors, such as temporary immersion systems. Somatic cells are generally cultured in liquid Murashige & Skoog (MS) media with 83 mM sucrose and 0.54 µM 2,4-D. These calli can be compact nodular, friable, or friable nodular. Studies indicate that compact nodular calli show high regeneration efficiency and can be used in slow-growth media or for cryopreservation of polyembryoid clumps. These polyembryonic aggregates, along with developing embryos, should be greater than 500 µm in diameter and should be selected from the cell suspension [

15]. Moreover, embryogenic calli with torpedo structures or haustoria are essential for the regression of polyembryoids after storage.

Methods of in vitro conservation can be practiced for mid-term storage, while cryopreservation is done for long-term storage (

Figure 2). Typically, in vitro meristematic tissues or somatic embryoids are inoculated into slow-growth media or into cryopreservation to sustain viability for medium to long-term preservation. Medium-term storage is achieved by inducing slow growth through the retardation of minimal growth media, using growth retardants or low temperatures [

23]. This enables the prolonging of subculturing intervals that range from 6 to 24 months. Increased subculturing cycles subsequently reduce the resources and labor needed for germplasm maintenance. “Cryopreservation” is a long-term storage method that requires samples to be kept under cryogenic conditions in liquid nitrogen to sustain viability and integrity for long durations [

23]. The procedure is expensive, complex, and time-consuming, requiring significant labor, resources, and expertise.

4.1. Factors Affecting In Vitro Conservation

The medium-term germplasm storage can be readily accomplished using standard procedures employed in plant tissue culture laboratories. However, the optimal procedure for propagule regeneration may be required before germplasm is subjected to in vitro conservation. A key consideration in medium- or long-term conservation methods is to slow or retard the growth of the cultures, while maintaining good viability during and after storage to ensure the successful recovery of conserved plant material. The following factors are optimized in protocols for germplasm conservation in vitro.

a. Growth Conditions

The factors considered include the photoperiod (or dark period), temperature, gaseous exchange, and media composition [

24,

25]. These factors were optimized individually or in combination for particular species. Temperature is critical during small- or medium-term storage, as it helps slow the growth of the explants [

26]. Low temperature is the most common medium-term strategy for conserving germplasm; however, tropical plant species, such as oil palms, are sensitive to low temperatures and require storage at higher temperatures. The storage temperature for cool-season crops ranges from 0 to 5ºC, while for tropical species, the optimum storage temperature is 10 to 20ºC, depending on the species [

26].

b. Osmotics and Encapsuation

Specialized growth media are tailored for the in vitro preservation of shoots, promoting slow explant growth. This gradual growth helps reduce the need for frequent subculturing by limiting cell division and growth, thereby maintaining genetic stability [

7]. As a result, cultures can be sustained for several years with minimal subculturing, depending on the plant species [

15]. The in vitro conservation of oil palm germplasm occurred at 20–25ºC using half-strength MS media supplemented with 3% mannitol. This method effectively inhibited the growth of aerial parts more than other osmotic agents like sorbitol and sucrose, achieving a 100% survival rate after one year of in vitro conservation [

27]. In comparison to the various osmotica (mannitol, sorbitol, and sucrose), the selection process was complicated by varying responses of palm cultivars to different concentrations of osmotica, making it challenging to identify a single optimal concentration effective across all cultivars [

27] . However, the study revealed that 3% mannitol provided better survival rates and better control over the growth of the aerial parts in oil palm [

27]. In date palm, sucrose provided the highest survival percentage in the cultivar ‘Sakkoty’. At the same time, the addition of 329.88 mM mannitol and 109.8 mM sorbitol resulted in the highest survivability in the cultivar ‘Bartamoda’ [

26].

Oil palm polyembryoids at the developmental stage of torpedo-shaped structures and haustoria were encapsulated with 3% sodium alginate by dipping in calcium-free MS media [

28]. The 6–7 mm beads encapsulating the polyembryoids were polymerized in 100 mL of 75 mM CaCl

2, which polymerizes the sodium alginate. The translucent coat was visually observed and turned opaque upon completion of the polymerization process [

28]. These encapsulated synthetic oil palm seeds were stored at temperatures ranging between 5 and 25ºC for up to 70 days. However, after just two months of storage, synthetic seeds lost their viability at high temperatures, especially at 25ºC. The best storage temperature was 5ºC, with the synthetic seeds retaining 67% viability, compared to 0% at 25ºC and 20% at 10ºC [

28].

c. Nutrient Media

Modifications in growth media, such as reducing the concentration of minerals, sucrose, and types of growth regulators, along with the use of chemicals to lower osmotic potentials (e.g. mannitol or polyethylene glycol), have also been beneficial for inducing slow growth [

23].

Growth retardants act as signals and precursors of growth and development. They typically bind to receptors in the cell, inducing various responses by modifying gene expression. These retardants activate novel gene expression and block normal growth and development. Different growth retardants, such as gibberellin inhibitors paclobutrazol (PBZ 0 - 10.34 μM) and tranexamic acid ethyl ester (TNE 0 - 13.7 μM), have been applied to reduce growth during in vitro conservation. A study in non-palm species showed that a concentration of 3.44μM (PBZ) and 4.56 μM (TNE) successfully retarded the growth of the aerial parts of the explants without affecting the survivability (96%) of the species even after 180 days of culture [

29].

In date palm, MS media supplemented with 2 mg/L abscisic acid and an osmotic concentration of 90 mg/L sucrose successfully induced the survivability of germplasm without the need for subculturing for up to 10 months at a low temperature of 18ºC and a light intensity of 10 μmol m

2s¹ [

30].

The size and volume of culture vessels were also crucial for storing explants. Activated charcoal was used to control the secretion of substances from the explants. The culture media included modifications in vitamins and antibiotics to avoid bacterial growth. Dormancy and bacterial growth were minimized by carefully selecting protocols and optimizing the subculturing process for oil palm explants.

5. Cryopreservation

Tissues or cells can be cryopreserved indefinitely in liquid nitrogen, allowing for long-term storage without losing viability or genetic stability of the preserved germplasm. Cryopreservation inhibits all metabolic activities and cell division, maintaining the germplasm indefinitely without changes in its genetic or phenotypic characteristics [

31]. Cryopreservation protocols have been established to prevent damage to the explants while preserving their regeneration capacity after rewarming and rehydration [

24,

25] (

Figure 3). The effect of various factors including the pre-culture and loading solution on the survival of explant has been documented in

Table 1.

Generally, tissues with high water content do not survive during cryopreservation. Additionally, dehydration must be rapid and uniform to avoid intracellular ice formation. Therefore, small-sized explants are recommended for more successful cryopreservation of genetic material. Meristematic and embryonic tissues, shoot tips, somatic embryoids, pollen, and zygotic embryos are commonly considered for in vitro cryopreservation [

31,

32]. Tissues exhibit varying responses to cryopreservation, and cultivars within species also respond differentially, necessitating the optimization of genotype-independent protocols.

Both penetrating and non-penetrating cryoprotectants are used to prevent injuries during dehydration. Various vitrification protocols, such as PVS2 and PVS3, have been developed for the cryopreservation of somatic embryos and apices in tropical and temperate species [

15]. PVS2 has been successfully applied in cryopreserving apical meristem tissues, calluses, cells, and somatic embryoids in clonally propagated species.

Encapsulation and dehydration techniques, which involve embedding plant material in beads, protect against dehydration and freezing damage. This technique has been successfully applied in clonally propagated species [

33]. Somatic and zygotic embryoids are often used for preservation, with factors such as sucrose concentration, dehydration period, and freezing damage being carefully considered during the cryopreservation process [

34].

5.1. Preparation of Propagules or Explants for Cryopreservation

Somatic embryoid clumps, zygotic embryos, pollen, seeds, and kernels have been studied for cryopreservation. Notably, the most effective techniques have focused on somatic or zygotic embryoids due to their superior viability and survival rates post-cryopreservation and thawing [

31]. Engelmann [

14] established the first cryopreservation protocol using somatic embryoids at the torpedo stage, created through two-month cultures with 0.3 M sucrose as the carbon source, which outperformed mannitol and sorbitol. Immature zygotic embryos and their endosperm were dehydrated for three days, transferred into 2 mL cryopreservation tubes, and preserved in liquid nitrogen for a duration of 1 to 60 days. The samples were then thawed in a water bath at 40 °C for 30 minutes. After thawing, zygotic embryos were dissected and placed on Y3 media enriched with 87.6 mM sucrose and 2.67 μM phytagel. Results showed that zygotic embryos had over 93% viability and 84% germination, whereas somatic embryoids maintained only 68% viability after cryopreservation [

34].

Somatic embryoids from 28 clones, regenerated after 20 years of cryopreservation, showed an overall average survivability of 33% [

36]. However, three clones were lost due to contamination and poor growth under in vitro conditions. Pollen was first incubated for cryopreservation in 1998. Pollen viability was assessed using the fluorescein diacetate (FDA) test and in vitro germination. The in vitro germination test media included 0.292 mM sucrose, 1.615 mM boric acid, and 10% polyethylene glycol. Pollen viability and in vitro germination rates were 62% and 52% for both procedures [

38], and the moisture content was 23.3% during storage. Pollen samples were removed in 2008, thawed, and warmed at 38°C for 5 minutes, after which their viability (52%) was evaluated. This was statistically insignificant compared to the original value of 62%, while in vitro pollen germination was 49% [

38] .

Meristematic tissues are also preferred explants in some species for

in vitro conservation of germplasm. Micromeristematic tissues, excised under aseptic conditions, are generally considered free from viruses and bacteria. Moreover, these tissues produce true-to-type plants and are less prone to mutations than callus or cell cultures [

39] . However, meristematic tissues in oil palm may not be suitable due to their limited availability, and their excision may cause the loss of the entire plant. Clonal propagation of oil palm is significantly more challenging than other palm species, such as date palm, because oil palms do not produce offshoots.

5.1. Pre-Culturing of Somatic Embryoids

Somatic embryoid clumps, zygotic embryos, pollen, seeds, and kernels have all been explored for cryopreservation. However, the most successful methods have involved somatic or zygotic embryoids, which exhibit better viability and survival rates following cryopreservation and thawing [

31,

32] . The protocol for cryopreservation of somatic embryoids at the torpedo stage was established by Engelmann [

24]. These somatic embryoids were produced through two-month cultures with 0.3 M sucrose as the carbon source, which proved more effective than mannitol and sorbitol. Immature zygotic embryos and their endosperm were dehydrated for 3 days, placed in 2 ml cryopreservation tubes, and stored in liquid nitrogen for 1–60 days. The samples were thawed in a water bath at 40°C for 30 minutes. Zygotic embryos were dissected and cultured on Y3 media supplemented with 87.6 mM sucrose and 2.67 μM phytagel. The zygotic embryos exhibited over 93% viability and 84% germination, compared to the somatic embryoids, which showed only 68% viability after cryopreservation [

34].

Somatic embryoids from 28 clones, regenerated after 20 years of cryopreservation, showed an overall average survivability of 33% [

36]. However, three clones were lost due to contamination and poor growth under in vitro conditions. Pollen was first incubated for cryopreservation in 1998. Pollen viability was assessed using the fluorescein diacetate (FDA) test and in vitro germination. The in vitro germination test media included 73.03 mM sucrose, 1.615 mM boric acid, and 10% polyethylene glycol. Pollen viability and in vitro germination rates were 62% and 52% for both procedures [

38], with a moisture content of 23.3% during storage. Pollen samples were removed in 2008, thawed, and warmed at 38°C for 5 minutes, after which their viability (52%) was evaluated. This was statistically insignificant compared to the original value of 62% [

38] , while in vitro pollen germination was 49% [

38].

Meristematic tissues are also preferred explants for in vitro conservation of germplasm in some species. Micromeristematic tissues, excised under aseptic conditions, are generally considered free from viruses and bacteria. Moreover, these tissues produce true-to-type plants and are less prone to mutations than callus or cell cultures [

39]. However, meristematic tissues in oil palm may not be suitable due to their limited availability, and their excision may lead to the loss of the entire plant. Clonal propagation of oil palm is significantly more challenging than that of other palm species, such as date palm, because oil palms do not produce offshoots. Historically, oil palms were cultivated from seeds before the optimization of somatic embryogenesis protocols.

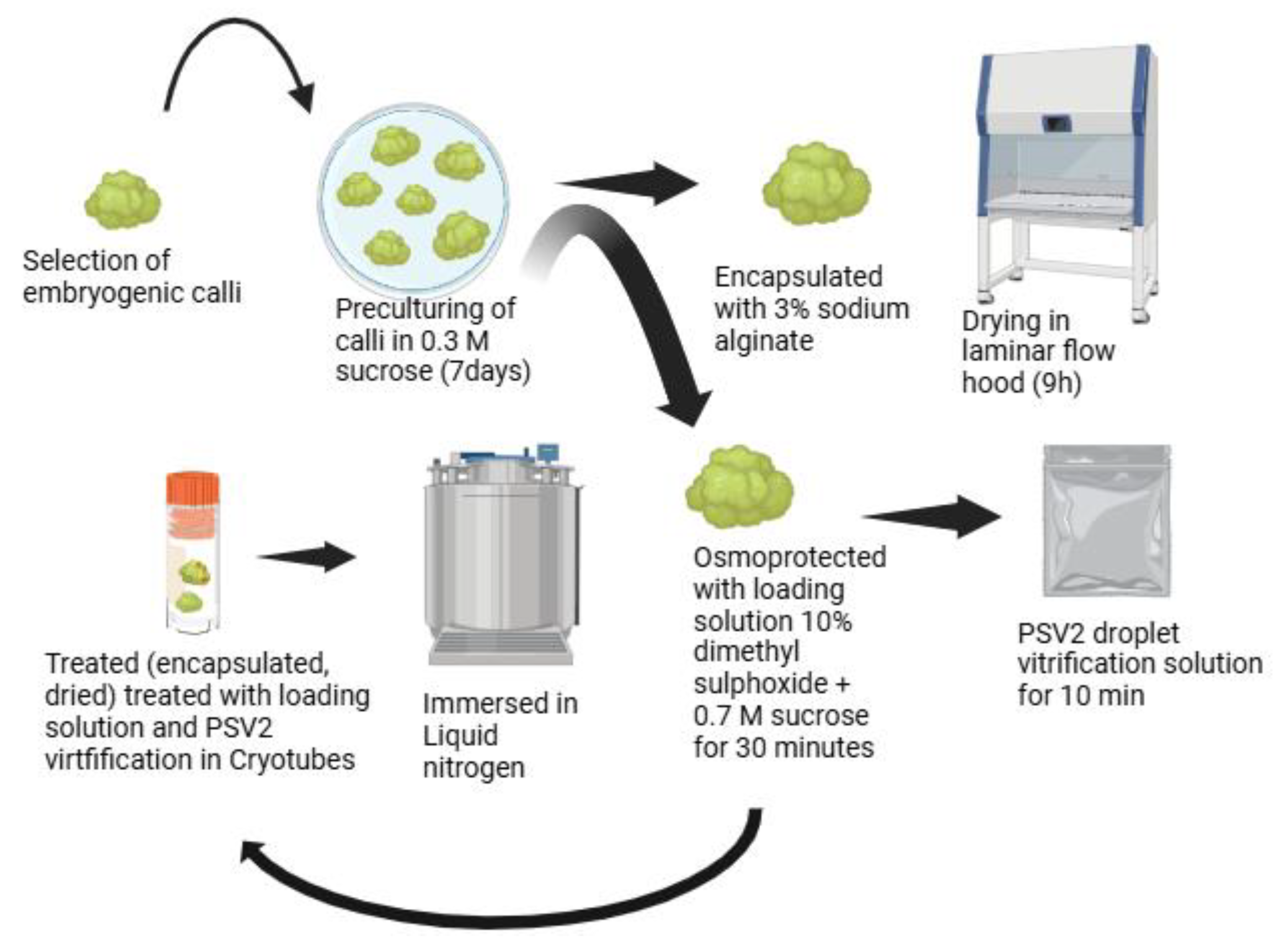

5.2. Encapsulation-Dehydration

Embryos of oil palm were encapsulated in alginate beads to protect them from direct exposure to vitrification solutions, thus safeguarding against the harmful effects of rapid dehydration. Initially, somatic embryoids were pre-cultured in a sucrose solution ranging from 0.3 to 1 M for 7 days. They were subsequently encapsulated in 3% sodium alginate together with 100 mM CaCl2, followed by a drying period of 9 hours that lowered their moisture content to 23%. The dehydrated encapsulated embryoids were then placed in cryotubes, stored in liquid nitrogen for 1 hour, thawed, and cultured on regeneration media. The cryopreserved and thawed polyembryoids showed a survival rate of 73% [

28]. In another study, somatic embryoids were selected and pre-cultured on 0.5 M sucrose for 12 hours. They were then osmoprotected using a loading solution of 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 0.7 M sucrose for 30 minutes, followed by treatment with the PSV2 droplet vitrification solution [

35]. Following this, the embryoids were placed into cryovials, stored in liquid nitrogen for 1 hour, thawed, and inoculated onto regeneration media [

35], resulting in a viability rate of 68%. Moreover, somatic embryoids were dried to a moisture content of 22% before undergoing cryopreservation for a period of 20 years [

36].

5.3. Vitrification

Vitrification is the physical process by which a concentrated solution transforms into a metastable glass under very low temperatures without crystallization [

40]. The theory of vitrification aims to convert tissues into a vitrified state without forming intra- or extracellular ice. Ice crystals formed due to improper handling can damage the propagule, leading to loss of tissue viability. The vitrification process requires careful selection and concentration of vitrification salts to avoid injury or salt toxicity during the desiccation process. Vitrification-based cryopreservation is the most common method, and several protocol modifications exist, including encapsulated vitrification, droplet vitrification, V-cryoplate, and D-cryoplate. Several vitrification solutions have been proposed, which are presented in

Table 2. Vitrification has been regarded as a powerful tool in numerous studies conducted on oil palm cryopreservation. The duration of exposure to various vitrification solutions, such as PVS2, is a critical factor, as different studies have shown that polyembryoid survivability declines with increasing exposure time. A 5-minute exposure induced vitrification in samples [

33]. In another study, PVS2 was recommended for 10 minutes for oil palm. The list of preservation media is documented in

Table 2. Among the loading solutions, L5 treated for 30 minutes was considered closest to the control due to its minimal detrimental effects on somatic embryoid viability [

33].

5.4. Droplet Vitrification

This is a modified vitrification technique that utilizes small droplets of cryoprotectants, with the samples placed on aluminum foils. Rapid cooling of the samples is achieved by directly exposing them to liquid nitrogen. Cryoprotectants help maintain the samples in the form of droplets. Microdroplets freeze spontaneously to a temperature below the glass transition phase, forming glass without ice crystal formation. This method has been used for the cryopreservation of polyembryos and is known as V-cryoplates in the context of droplet vitrification. The primary advantage of this technique is the rapid cooling of the sample, which allows direct transition to the glassy state. Additionally, microdroplet formation enables the cryopreservation of small-sized samples, such as cells, somatic embryoids, and torpedoes, and is more effective than other vitrification methods. Pre-cultured polyembryoids were treated with a loading solution of 1.5 M glycerol, 0.4 M sucrose, and 5% (w/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 30 minutes under continuous light at 60 μmol m

−2 s

−1 photosynthetically active photon flux density (PPFD) at 26°C [

33]. Polyembryoids precultured on 0.5 M sucrose and treated with the loading solution were then subjected to pre-chilled 100 µL of PVS2 vitrification solution, with varying drying durations. A drying period of 10 minutes reduced the moisture content to 47%, and the survival rate was approximately 68% after exposure to liquid nitrogen [

37] .

7. Problems with Cryopreservation and the Way Forward

The major problem with cryopreservation is the genotype specificity for somatic embryogenesis and its variable responses to cryopreservation. Each genotype comprises a specific set of alleles in the genome that help it respond to the in vitro conditions for somatic embryogenesis. Several genes related to somatic embryogenesis, specifically

15 WUSCHEL-related homeobox (

WOX) genes and

BROOM, have been identified in the genome of oil palm [

57]. Other genes related to somatic embryogenesis include

EgIAA9,

EgHOX1,

EgLSD, and

EgER6, which are activated by indole acetic acid and other growth regulators [

58,

59,

60]. There is a need to understand the upregulation of genes related to somatic embryogenesis, and fine-tuning their expression may help induce somatic embryogenesis in recalcitrant types. Moreover, epigenetic factors related to callus induction and somatic embryogenesis may also be considered, as it was identified that procambial cells of leaf sheath undergo hypomethylation (5%) triggered by indole acetic acid. In contrast, non-responsive cells (Parenchymatous sheath cells) show contrasting behavior; i.e., hypermethylation [

61]. Methylation-sensitive DNA markers may be used to differentiate the responsive and non-responsive cellular genotypes. There is also the variable response of genotypes to cryopreservation, with few genotypes successfully preserved through this process, while others exhibit a recalcitrant response. This differential response may be due to the variability among germplasm accessions in their tolerance to adverse conditions, such as salt toxicity, chilling, and abiotic stress. Generally, stresses induce the leakage of the membrane due to reactive oxygen species (ROS), which activate ROS species scavenging enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POD) [

62]. The mechanism of abiotic stress tolerance may be fully understood, and strategies may be formulated. For instance, a study has shown that the expression of several cold-tolerant genes, including CBF1 and CBF2, is related to osmolytes such as proline and sucrose, while cold injury is associated with the accumulation of proline [

63]. Moreover, secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, plant hormones, and vitexin, isovitexin, and apigenin 6-C-glucoside were accumulated in response to chilling stress and contributed to their antioxidant activities under stress conditions [

62]. The synthesis of L-glutamic acid and sarcosine in resistant accessions under chilling stress aids in protein synthesis and supports cell recovery and repair mechanisms. The

EgCBF3 gene has been reported to be activated in response to several abiotic stresses through abscisic acid signaling [

64]. Thus, inducing progressive treatment of stress or allowing embryos to harden before cryopreservation, or exposing them to osmolytes and enhancing the media composition with antioxidants and amino acids, may help better acclimate them during cryopreservation.

8. Outlook

Advances in cryopreservation have revolutionized the concept of germplasm conservation. Newly optimized techniques, such as vitrification and encapsulation-dehydration, have proven highly effective for storing somatic and zygotic embryos. The advantage of these methods includes preventing crystal formation during storage, which may otherwise damage the plant cell and reduce the mortality rate of the zygotic embryo. The optimization of cryoprotectants, such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and sucrose solutions, has significantly reduced the toxicity and osmotic stress experienced by embryos, thereby increasing the overall success of long-term storage. The success of cryopreservation may play a significant role in conserving genetic diversity, particularly in the case of oil palm. All kinds of genetic variability, such as obsolete cultivars or wild species, may be stored for longer times. The cryopreservation could help oil palm breeding programs by conserving genetic libraries or core germplasm containing valuable traits over extended periods. This may reduce the costs associated with conserving intensive field gene banks. It is also a convenient method for the transfer and exchange of plant materials from various geographical regions, thereby contributing to the conservation of global genetic resources. This may provide a stable foundation for the long-term genetic improvement of oil palm. Moreover, cryopreservation enables the preservation.

This technology will not only help conserve genetic diversity but also facilitate molecular research. For instance, the vitrified embryo has been a viable alternative to the fresh zygotic embryo for CRISPR/Cas9 microinjection, with a survival rate of 63% compared to 49% and an almost comparable mutation rate. The real challenge for future research may be to explore the non-toxic alternative DMSO, which could provide a significantly higher protection against cryoinjury and potentially lead to better survival rates. The use of genetic modification technology may be exploited to modify genes or disrupt the mechanisms that induce injuries during cryopreservation. The bioreactor systems can also be utilized for the mass production of somatic embryoids, which can later be stored, thereby enhancing our efforts in large-scale production and cryopreservation. This could be a game-changer for the large-scale conservation efforts.

The major shortcoming in the cryopreservation of somatic embryoids is the genotype specificity of somatic embryogenesis, which may hinder the large-scale production of somatic embryoids in targeted accessions. Research has shown that the success of cryopreservation has been applied to a limited number of genotypes within species, and there is significant variability among these genotypes in terms of their totipotency potential. Moreover, the cultivars also exhibit variable responses to dehydration and cryoprotectant treatment. This genotype dependency complicates the development of universal protocols for oil palm cryopreservation. Understanding the genetic and physiological factors that affect genotypic responses to cryopreservation is required, as it may enable the development of standardized, genotype-independent protocols.

9. Conclusion

In vitro conservation is a potential technique for preserving genetic diversity within a plant species. This technique has been exploited for the preservation of polyembryoids for medium to long-term storage in oil palm. Polyembryoids were subjected to mid-term conservation at low temperatures, with a slow growth rate induced by the use of different osmotica. In certain instances, they were encapsulated with sodium alginate to enhance low-temperature tolerance before storage. In long-term conservation, the polyembryoids were desiccated and precultured on various osmotica before being subjected to the loading solution. Moreover, polyembryoids were also subjected to vitrification, including droplet vitrification, before cryopreservation. The cryopreserved embryos were thawed and cultured in regeneration media, which yielded variable results in terms of survivability and growth. In vitro conservation is based on a tissue culture-based procedure that necessitates the development of a genotype-independent protocol for inducing somatic embryogenesis, followed by the regeneration of somatic embryoids after storage. The somatic embryogenesis process is strongly genotype-dependent, and the composition of the growth media and concentration of plant growth regulators also influence its success. Thereby, the applicability of this technique is limited to a restricted number of genotypes, which can reduce its usefulness. In vitro conservation requires a standardized procedure that can be applied universally, regardless of the plant genotype, to ensure the conservation of larger germplasm sets. Continued research is necessary to identify optimal cryoprotectants, both penetrating and non-penetrating, and their interactions with different explant types. Utilizing non-toxic cryoprotectants and refining dehydration methods can reduce cryoinjuries during freezing, improving long-term survival rates. Encapsulation-dehydration methods combined with cryopreservation can protect against dehydration and ice formation, which is crucial for maintaining tissue viability. Furthermore, the genetic stability of the conserved plant material must be maintained and not compromised during storage. The genetic stability of the genotypes can be determined through advanced molecular techniques, such as genome sequencing, to identify potential sites of mutations and genome modifications that may occur during storage. This enables the detection of any genetic changes that may have happened, ensuring that the conserved plant material remains genetically stable and accurately represents its type. There is also a need to understand the mechanisms behind cryoinjuries and how to mitigate them effectively, a topic that remains underexplored. Therefore, research is needed to know how to prevent damage caused by ice formation and osmotic stress during the cryopreservation process.