1. Introduction

Migraine is a chronic, episodic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent attacks of pulsating headache, often accompanied by nausea, photophobia, phonophobia, and sensory hypersensitivity [

27]. It ranks among the leading causes of disability worldwide and is the foremost cause of years lived with disability in adults under fifty years of age [

24,

25]. Global Burden of Disease estimates indicate that more than 1.1 billion individuals are affected by migraine worldwide, corresponding to a lifetime prevalence of approximately 14–15 percent [

24]. The disorder affects women nearly three times more frequently than men, with peak prevalence occurring in early adulthood during peak years of productivity, a disparity attributed in part to estrogen-mediated modulation of trigeminovascular sensitivity [

25,

27]. Migraine prevalence also varies geographically, with higher reported rates in North America and Europe compared with parts of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa [

24].

Despite its prevalence and societal impact, migraine remains underdiagnosed and incompletely understood. Population-based surveys suggest that up to half of individuals meeting diagnostic criteria have never received a formal diagnosis, and many rely primarily on over-the-counter medications for symptom relief [

26,

28]. Chronic migraine, defined as headache occurring on at least fifteen days per month for more than three months, affects approximately 1–2 percent of the population and is associated with heightened central sensitization, psychiatric comorbidity, and medication overuse [

26,

27]. Collectively, these factors contribute to substantial socioeconomic burden through lost productivity and increased healthcare utilization, including emergency department visits and specialist care [

26].

Although multiple pharmacologic therapies are available, including triptans, calcitonin gene–related peptide–targeted agents, beta-adrenergic blockers, and antiepileptic drugs, a significant proportion of patients experience incomplete symptom control or remain refractory to treatment [

27]. These therapeutic limitations have prompted increasing interest in identifying anatomical and physiological drivers of migraine that may serve as more proximal intervention targets.

Increasing evidence from angiographic and neuroimaging studies implicates the middle meningeal artery (MMA) as a critical contributor to migraine pathophysiology. Dynamic changes in MMA caliber and flow have been shown to correlate with headache onset and severity, and the artery’s close anatomical relationship with trigeminal sensory afferents positions it as a key site of neurovascular and neuroimmune interaction [

1]. Unlike intracranial arteries, the MMA resides at the interface of dura-associated immune cells, meningeal nociceptors, and extracranial vascular supply, conferring unique accessibility for targeted endovascular intervention. Accordingly, intra-arterial pharmacologic modulation of the MMA represents a promising strategy to intervene directly at the vascular–inflammatory interface underlying migraine pathogenesis.

2. Pathophysiology of the Migraine and the Role of the MMA

2.1. Neuromuscular Activation

Migraine often begins when the MMA exhibits abnormal vasomotion, or changes in diameter. Pulsatile dilation and mechanical stress activate endothelial cells, which then release nitric oxide, vasodilator, and prostaglandins, inflammatory mediators. The cells also increase adhesion molecules, such as Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. This sets the stage for the subsequent immune activation, mast cell recruitment, trigeminovascular sensitization, and amplification described in following subsections 2.2 through 2.6.

2.2. Trigeminovascular Activation

Perivascular sensory fibers from the ophthalmic branch of the Trigeminal Nerve, also known as Cranial Nerve V (CNV), run in close apposition to the MMA. These fibers contain two major nociceptive populations called Aδ fibers that are thinly myelinated and sense fast-pain and C fibers which are unmyelinated and sense slow-pain. Both of which express mechanosensitive ion channels, including Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), Acid-Sensing Ion Channels (ASICs), and Piezo channels, all of which convert mechanical stretch into electrical signals.

When the MMA dilates or constricts, the resulting deformation of the arterial wall mechanically distorts the surrounding perivascular space. This deformation opens mechanosensitive channels on the Trigeminal Nerve endings, causing cation influx (primarily Na⁺ and Ca²⁺), which depolarizes the nociceptor membrane and generates action potentials. Activation of these fibers triggers the release of several neuropeptides from their peripheral terminals, including:

CGRP (calcitonin gene–related peptide): a potent vasodilator that increases blood flow and vascular permeability.

Substance P: a neuropeptide that promotes plasma extravasation and mast cell degranulation.

Neurokinin A: a tachykinin involved in promoting prolonged vasodilation and inflammation.

CGRP, in particular, binds to the CGRP receptor complex (composed of CLR + RAMP1) on vascular smooth muscle and dural immune cells, leading to further vasodilation, increased release of inflammatory mediators, and additional activation of nearby nociceptors. This creates a positive feedback loop of neurogenic inflammation in the dura mater.

These events trigger the trigeminovascular reflex, a pathway in which peripheral trigeminal activation drives ascending pain transmission to the Trigeminal Nucleus Caudalis (TNC) in the brainstem. Neurons in the TNC then relay signals to higher-order pain centers, including the thalamus and somatosensory cortex, thereby converting peripheral MMA activity into the conscious perception of migraine pain.

2.3. Neuroimmune Crosstalk and Amplification

Following neuropeptide release from activated trigeminal fibers, dural mast cells located adjacent to the MMA are among the first immune cells to respond. These sentinel immune cells are activated when exposed to CGRP, Substance P, and local mechanical or inflammatory signals. Once activated, mast cells degranulate and release a variety of mediators, including histamine, tryptase, Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), and prostaglandins, all of which intensify local inflammation within the dura mater.

In parallel, proinflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), TNF-α, and Interleukin-6 (IL-6), as well as chemokines such as C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), are released from resident immune cells and infiltrating leukocytes. These molecules recruit monocytes, neutrophils, and T cells into the dural space, further expanding the inflammatory milieu surrounding the MMA.

These cytokines exert direct effects on nearby trigeminal nociceptors. IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 all upregulate the expression of TRPV1 and CGRP genes by binding to their promoter regions and activating intracellular signaling pathways. IL-1β and TNF-α primarily signal through Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) and the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK) and Protein Kinase C (PKC) pathways, which enhance transcription of pro-nociceptive genes. IL-6 acts through the STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) pathway to increase gene expression and indirectly raise neuronal excitability.

The neuropeptides released from sensory fibers and the inflammatory mediators secreted by immune cells increase vascular permeability by loosening endothelial junctions. Plasma proteins then leak into the dura, causing tissue swelling (edema) that exerts mechanical pressure on nearby nociceptors. This swelling further activates mechanosensitive channels and sustains nociceptor firing, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of neurogenic inflammation that amplifies and prolongs migraine pain signaling.

2.4. Central Sensitization

As trigeminovascular activation persists, peripheral trigeminal neurons begin to upregulate ion channels and nociceptive receptors, including TRPV1, voltage-gated sodium channels (Nav1.7, Nav1.8), and purinergic receptors. This molecular remodeling lowers the neuronal activation threshold, allowing previously non-painful mechanical changes in the MMA to generate action potentials. In addition to increasing receptor number, inflammatory cytokines simultaneously sensitize existing TRPV1 channels, reducing their activation threshold for heat, mechanical deformation, and acidic environments. Together, these changes produce peripheral sensitization, in which nociceptors become hyper-responsive to normal dural or vascular stimuli.

Sustained afferent input from the MMA then drives long-term changes within the central nervous system (CNS). In the brainstem, continuous nociceptive signaling entering the Trigeminal Nucleus Caudalis (TNC) results in central sensitization, a phenomenon characterized by heightened excitability of second-order neurons. These neurons begin responding excessively to incoming trigeminal input and may even fire spontaneously, amplifying pain signaling independent of ongoing peripheral triggers.

Central sensitization is reinforced by glial activation. Microglia, the resident immune cells of the CNS, release IL-1β, TNF-α, and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), each of which increases neuronal excitability and enhances synaptic transmission. In parallel, astrocytes release the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, which accumulates in the synaptic cleft and further depolarizes TNC neurons. Microglia and astrocytes also downregulate inhibitory GABAergic signaling, tipping the system toward excitation.

The combined effect of enhanced glutamatergic drive, neuroinflammatory signaling, and reduced inhibitory tone results in a potentiation of synaptic strength within the TNC. Clinically, this manifests as allodynia that is a pain in response to normally non-painful stimuli and widespread sensory hypersensitivity which are the hallmark features of migraine escalation.

2.5. Clinical Correlation: Middle Meningeal Artery Dynamics and Migraine Expression

During migraine attacks, cyclic dilation and constriction of the MMA artery generate shear stress that activates the vascular endothelium and adjacent perivascular trigeminal afferents. Endothelial activation is associated with increased expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2, resulting in elevated local concentrations of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E₂. Nitric oxide diffuses into vascular smooth muscle cells and nociceptive terminals, activating cyclic guanosine monophosphate–dependent protein kinase signaling and subsequent phosphorylation of ion channels that heighten neuronal excitability. Concurrently, cyclooxygenase-2–derived prostaglandins sensitize prostaglandin E receptors on trigeminal afferents, facilitating calcitonin gene–related peptide release and amplification of trigeminovascular signaling through cyclic adenosine monophosphate–dependent protein kinase pathways that modulate TRPV1 and Nav1.7 channel activity [

1,

19].

Imaging and angiographic studies further support a clinically relevant role for the MMA in migraine, demonstrating that changes in arterial diameter and flow dynamics correlate with headache onset, severity, and chronicity. These observations suggest that MMA artery hemodynamics may serve not only as a biomarker of migraine activity but also as a modifiable therapeutic target. Collectively, these vascular, neuronal, and inflammatory interactions contribute to the characteristic throbbing headache of migraine, frequently accompanied by nausea, photophobia, and phonophobia. In chronic migraine, this neurovascular–immune feedback loop appears to become self-sustaining, reinforcing central sensitization and persistent symptom burden [

1].

3. Materials and Methods

This study was designed as a focused narrative review, given the limited number of centers, heterogeneous study designs, and evolving nature of intra-arterial pharmacologic interventions targeting the middle meningeal artery (MMA) for migraine management. A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify mechanistic and clinical evidence relevant to this emerging therapeutic strategy.

Electronic searches of the PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, and Neuroscience Abstracts databases were performed for studies published between January 2000 and September 2025. Additional relevant articles were identified through manual review of reference lists from selected publications.

Search terms included combinations of the following keywords: “middle meningeal artery,” “migraine,” “intra-arterial,” “nimodipine,” “verapamil,” “lidocaine,” “refractory headache,” “status migrainosus,” “reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome,” “MMA embolization,” “calcitonin gene–related peptide,” and “neuroinflammation.” Boolean operators (“AND,” “OR”) were applied to refine search results.

Peer-reviewed abstracts, case reports, case series, reviews, and clinical studies were eligible for inclusion if they described intra-arterial administration of pharmacologic agents targeting the MMA or closely related cerebrovascular pathways implicated in migraine pathophysiology. Studies focusing exclusively on non-arterial routes of administration or headache etiologies unrelated to migraine were excluded.

Article screening and selection were performed by the authors based on relevance to the study objective. When questions regarding eligibility arose, inclusion was determined by consensus discussion. Given the exploratory and narrative nature of the review, no formal risk-of-bias assessment was applied.

The included literature was synthesized thematically to contextualize current intra-arterial treatment approaches according to mechanistic targets within the trigeminovascular and neuroimmune cascade, as well as reported clinical outcomes. To enhance transparency regarding evidence strength, data on study design, sample size, patient characteristics, follow-up duration, and reported limitations were extracted and summarized in

Supplementary Table S1.

4. Operative Technique

Access to the MMA is usually obtained via transradial or transfemoral catheterization under biplane angiography. After sheath placement, a diagnostic catheter is placed in the external carotid artery and a microcatheter is navigated into the frontal and parietal MMA branches using standard technique. Detailed catheter steps have been described elsewhere and will not be re-iterated in the present work.

For chronic subdural hematoma, commonly used permanent embolic agents include nonadhesive liquid embolics such as Onyx and Squid, n-butyl cyanoacrylate, and particulate embolic agents including polyvinyl alcohol or calibrated microspheres such as Embozene, sometimes used in conjunction with adjunctive coils. Liquid embolics are ethylene–vinyl alcohol copolymers dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and combined with a radiopaque tantalum component. These agents permit controlled, progressive injection but may be associated with dimethyl sulfoxide–related vasospasm, endothelial irritation, microcatheter entrapment, and nontarget embolization if reflux is not adequately recognized. n-Butyl cyanoacrylate polymerizes rapidly upon contact with blood, and injection that is overly proximal or excessively rapid may result in microcatheter adhesion or migration into nontarget arterial branches. Particle embolization typically results in more proximal vessel occlusion and may reduce the likelihood of embolic material traversing potentially dangerous anastomoses, at the expense of less consistent distal penetration into the neomembrane microvasculature. Contemporary clinical series report low overall complication rates on the order of two to three percent, with no definitive difference in safety profiles between embolic agents when injections are performed slowly and selectively [

21].

Serious adverse events are rare but warrant careful consideration. Reported complications include ischemic stroke, ophthalmic artery occlusion with ipsilateral vision loss due to embolic material traversing meningo-ophthalmic or MMA–ophthalmic anastomoses, facial nerve palsy secondary to embolization of the petrosal branch, additional cranial neuropathies, venous sinus thrombosis, dural arteriovenous fistula formation, pseudoaneurysm of the MMA, and ischemia of the scalp or masticatory musculature. Risk mitigation begins with selective internal and external carotid angiography prior to embolization to delineate hazardous anastomoses, with particular attention to meningo-ophthalmic connections and petrosal branches. The microcatheter is advanced distal to these collateral pathways, followed by test injections and slow, controlled delivery of liquid embolic agents with frequent assessment for reflux. Embolization is deferred in the presence of active vasospasm to minimize the risk of retrograde flow. Completion angiography of the internal and external carotid circulations confirms successful occlusion of the targeted MMA branches and the absence of unintended anastomotic opacification. [

22].

For headache indications, the MMA may also be used as a conduit for intra-arterial lidocaine, typically administered at doses of approximately 40 to 50 mg per side and infused slowly over several minutes, sometimes in combination with methylprednisolone. Published case series in patients with refractory migraine and headache associated with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage report rapid pain relief without permanent neurologic complications and only minor, transient adverse effects. From a pharmacologic perspective, lidocaine has a narrow therapeutic window, and elevated systemic concentrations may result in circumoral numbness, tinnitus, agitation, seizures, or cardiac arrhythmias. Accordingly, MMA artery infusion protocols restrict total doses to levels below standard intravenous thresholds, administer the drug in small aliquots with intermittent pauses for reassessment of neurologic and cardiorespiratory status, and avoid concomitant medications that lower the seizure threshold. As with other endovascular interventions, general procedural risks remain, including access-site hematoma, vessel dissection or perforation, contrast-related reactions, and radiation exposure, although these events appear infrequent in published MMA series. [

23].

5. Pharmacologic Interruption of the Cascade

5.1. Intra Arterial Calcium Channel Blockers

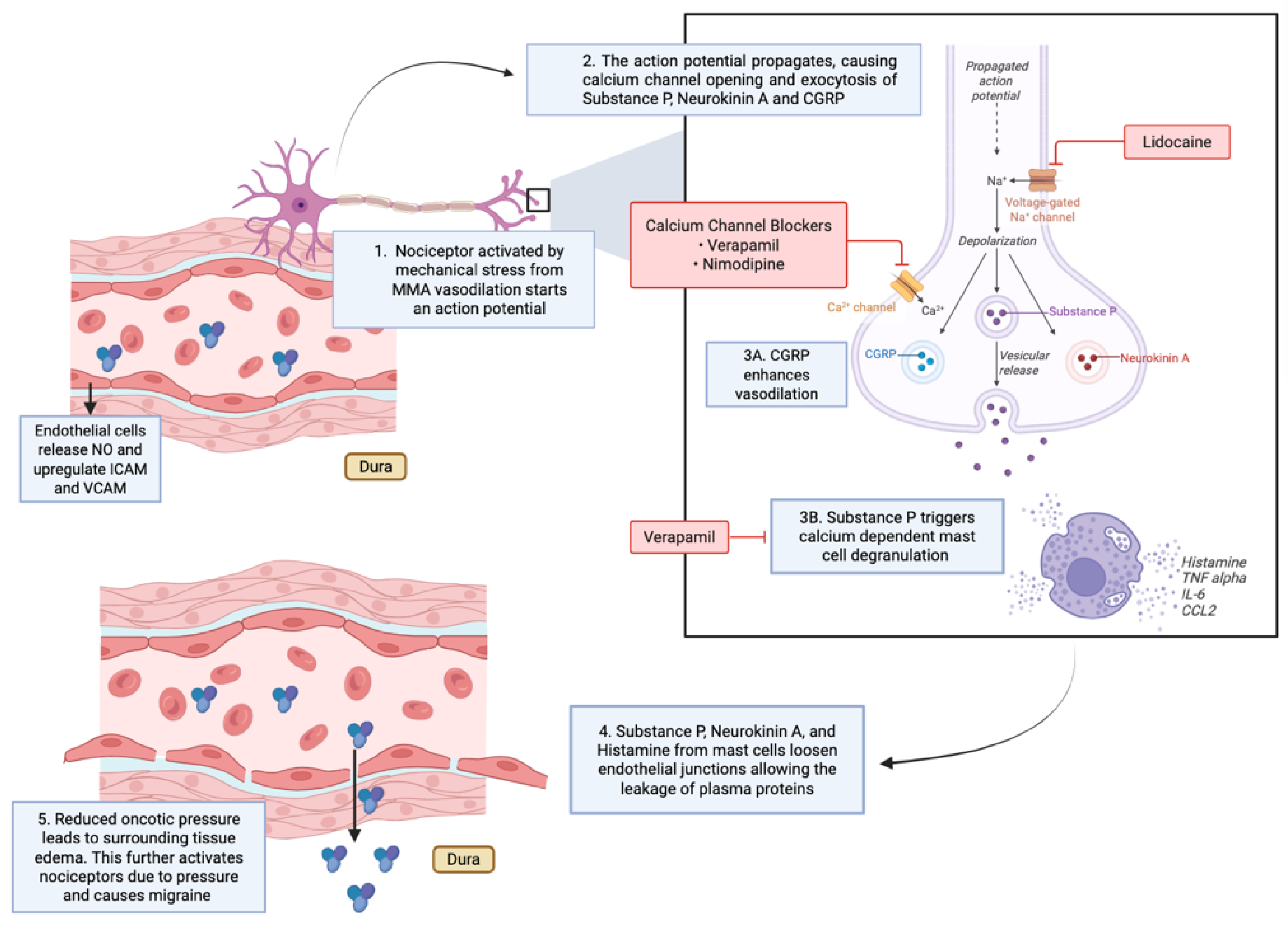

Within this signaling framework, outlined in

Figure 1, several intra-arterial pharmacologic strategies act at distinct points in the migraine cascade. Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) intervene upstream of sustained nociceptor activation by modulating vascular smooth muscle tone (

Figure 1, Steps 1–2). By inhibiting L-type calcium channels in middle meningeal artery (MMA) smooth muscle, these agents stabilize arterial caliber and reduce pulsatile mechanical stress, a key driver of perivascular trigeminal nociceptor activation (

Figure 1, Step 1). This vascular stabilization also exerts secondary effects on endothelial cells by attenuating shear-dependent signaling (

Figure 1, Step 3).

Because they reduce smooth muscle contraction, calcium channel blockers such as nimodipine have been used in headache disorders characterized by pathologic vasoconstriction. In a reported case, Elstner et al. administered intra-arterial nimodipine via the internal carotid and vertebral arteries in a patient with migraine who was subsequently diagnosed with reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS). This intervention reversed diffuse cerebral vasospasm and ischemic changes, with rapid resolution of headache symptoms and sustained improvement at follow-up [

4]. Although performed for diagnostic and therapeutic management of RCVS, this case illustrates how intra-arterial calcium channel blockade can acutely modulate aberrant cerebrovascular tone and associated headache phenotypes by interrupting early vascular drivers of the cascade (

Figure 1, Steps 1–2).

Verapamil, another calcium channel blocker, similarly promotes vascular relaxation and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects that extend beyond hemodynamic modulation. In addition to stabilizing arterial tone, verapamil reduces endothelial activation and inflammatory mediator release, contributing to improved vascular homeostasis and attenuation of downstream neurogenic inflammation (

Figure 1, Steps 3–4).

Like nimodipine, verapamil is administered intra-arterially through the internal carotid or vertebral arteries in suspected RCVS. In this context, verapamil induces arterial dilation that aids in both diagnosis and treatment. Case series report increased arterial calibers and improved neurologic symptoms following intra-arterial verapamil, including in patients with severe, medication-refractory disease. These observations support the role of intra-arterial calcium channel blockade in headache syndromes driven primarily by vasoconstriction rather than neuropeptide-mediated vasodilation (

Figure 1, Step 1 vs Step 3A).

In contrast to CCBs, lidocaine acts predominantly at the neuronal and neuro-immune interface. Lidocaine blocks voltage-gated sodium channels on trigeminal afferents, suppressing action potential propagation and inhibiting the release of CGRP and substance P (

Figure 1, Step 2). This neuronal silencing directly limits mast cell degranulation and downstream neurogenic inflammation (

Figure 1, Step 3B).

Beyond its effects on neuronal excitability, lidocaine modulates immune signaling by inhibiting NF-κB activation in immune cells, thereby reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α and preserving endothelial junctional integrity (

Figure 1, Step 4). The combined effect is interruption of signaling at the neuro-immune synapse. Whereas calcium channel blockers primarily reduce cascade initiation by stabilizing vascular tone, lidocaine is suited to terminating an already active migraine cascade by suppressing neuronal and inflammatory amplification (

Figure 1, Steps 2–4).

5.2. Intra-Arterial Lidocaine

Several studies have investigated intra-arterial lidocaine infusion into the MMA for headache relief, targeting neuronal propagation and neurogenic inflammation within the trigeminovascular system (

Figure 1, Steps 2–3). A case series of 45 patients with refractory headaches found that intra-arterial lidocaine infusion provided immediate relief in 64.4% of patients. At one month, 57% of participants maintained a reduction of more than 50% in headache days; however, the effect declined over the subsequent three months. The procedure was generally safe, with only minor adverse events [

8].

For patients with severe headaches from subarachnoid hemorrhage, intra-arterial lidocaine led to immediate and sometimes complete headache relief. This benefit may reflect vasoconstriction of the MMA, reversing migraine-related vasodilation and attenuating trigeminal nociceptor activation (

Figure 1, Steps 1–2) [

9,

10].

In patients with severe headaches and status migrainosus, intra-arterial lidocaine injected into the MMA immediately lowered headache intensity. In those with status migrainosus, it also improved Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) scores at three months. The benefits are related to sodium channel blockade and central desensitization of trigeminovascular signaling (

Figure 1, Step 2). Long-term effects were limited, and further trials with alternative intra-arterial analgesics are recommended before this invasive procedure sees widespread use [

11].

Recent reports describe combined strategies involving intra-arterial lidocaine followed by posterior MMA embolization, reflecting complementary interruption of neuronal signaling and vascular sensitization pathways (

Figure 1, Steps 2–3). One study used intra-arterial lidocaine injection followed by bilateral MMA embolization in 10 patients with refractory headaches, resulting in significant improvement in Headache Impact Test (HIT) scores over six months [

13]. Similar approaches using intra-arterial lidocaine with Onyx embolization have also been reported [

14].

A review of the literature supports the anatomical and experimental basis for targeting the MMA with intra-arterial lidocaine in migraine, while emphasizing the need for further research to refine protocols and clarify long-term efficacy across headache phenotypes (

Figure 1) [

15].

6. Other Pharmacological Targets

Preclinical and translational studies examining meningeal and trigeminovascular models suggest that purinergic signaling within the middle meningeal artery may be relevant to migraine-related mechanisms. Experimental work has shown that P2X3 receptor activity is associated with trigeminal nociceptor sensitization and neuropeptide release, while P2Y13 signaling has been implicated in modulation of meningeal vascular tone and inflammatory signaling pathways linked to headache phenotypes [

16,

17,

18]. Separately, studies investigating vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 signaling in meningeal vasculature demonstrate its involvement in regulating arterial reactivity and neuropeptide-mediated communication within the dura, processes that have been associated with migraine-like responses in experimental systems [

16,

17,

18]. Human vascular studies further support these mechanistic findings by demonstrating marked, dose-dependent CGRP-mediated dilation of the middle meningeal artery following systemic CGRP administration, supporting the relevance of CGRP signaling within the meningeal vasculature, despite the absence of direct clinical MMA-specific intervention studies [

19].

Table 1.

Summary of Indications Vasoactive Substances Targeting the MMA.

Table 1.

Summary of Indications Vasoactive Substances Targeting the MMA.

| Vasoactive Substance |

Use |

Mechanism of Action |

Citations |

| Nimodipine (CCB) |

Case use in RCVS-related vasospasm and migraine relief |

Inhibits L-type calcium channels in MMA smooth muscle → reduces vasomotion and pulsatile stress; stabilizes vascular tone |

Elstner et al., 2009 |

| Verapamil (non-DHP CCB) |

RCVS treatment; diagnostic and therapeutic intra-arterial use for vasoconstriction-driven headaches |

Smooth muscle relaxation via calcium channel blockade; modest immunomodulatory effects (↓ inflammatory signaling) |

Farid et al., 2011

Ospel et al., 2020

Sequeiros et al., 2020 |

| Lidocaine |

Refractory headaches, status migrainosus, SAH-related headache |

Blocks voltage-gated sodium channels on trigeminal afferents → silences action potentials; prevents CGRP/substance P release; stabilizes mast cells; ↓ NF-κB signaling & cytokines; preserves endothelial junctions. |

Khattar et al., 2025; Mancuso-Marcello et al., 2023;

Sirakov et al., 2025; Jaikumar et al., 2025 |

| Lidocaine + MMA Embolization (Onyx, PVA, etc.) |

Refractory migraine and chronic headache (combined strategy) |

Combines sodium channel blockade with embolization-induced reduction of dural vascular contribution to pain |

Catapano et al., 2022; Vanzin & Manzato, 2025 |

| Purinergic Receptor Modulators (P2Y13 agonists, P2X3 antagonists) |

Experimental/preclinical migraine targets |

Modulate MMA vasoreactivity and trigeminal neuropeptide release |

Haanes et al., 2019 |

| VPAC1 Receptor Modulation (PACAP/VIP pathways) |

Experimental/preclinical |

PACAP and VIP cause vasodilation of MMA; receptor modulation may attenuate vasodilatory/mast cell-mediated pathways |

Boni et al., 2009; Bhatt et al., 2013 |

| CGRP Receptor Antagonists (e.g., zavegepant) |

Translational/clinical migraine therapy |

Block CGRP-induced MMA dilation. |

De Vries et al., 2023 |

7. Discussion

7.1. Overview of the Evidence Base

Available evidence from both preclinical and early clinical investigations suggests that the MMA may represent a biologically plausible therapeutic target for refractory headache and migraine disorders, although the clinical literature remains preliminary. Mechanistic support derives from controlled in vivo rodent studies and a multimodal translational investigation demonstrating that vasoactive and neuroimmune mediators, including calcitonin gene–related peptide, pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide, vasoactive intestinal peptide, and purinergic ligands, modulate middle meningeal artery vasoreactivity, mast cell activation, and trigeminovascular signaling through complementary animal and human ex vivo dural artery models [

16,

17,

18]. Additional human vascular pharmacology evidence is provided by an ex vivo study comparing calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist potency across human arterial beds, supporting direct pharmacologic modulation of CGRP-responsive vascular tissue despite not being performed in the middle meningeal artery itself [

19].

The clinical evidence base remains limited and consists primarily of small, single-center observational studies. These include retrospective and prospective case series evaluating intra-arterial lidocaine infusion for refractory headache and migraine [

8,

11,

20], small prospective or retrospective series describing middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic or refractory headache syndromes [

12,

13], and observational studies of intra-arterial calcium channel blocker administration in patients with reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome presenting with severe headache [

5,

6,

7]. Several additional single-patient case reports further demonstrate procedural feasibility and short-term symptom modulation but do not establish comparative efficacy or durability [

4,

14].

7.2. Anatomical and Neuroimmune Rationale

Anatomically, the MMA lies in close proximity to dural vessels, trigeminal afferent fibers, calcitonin gene–related peptide–rich perivascular nerve endings, and dural mast cell populations, all of which are key contributors to headache initiation and propagation [

1,

16]. This unique neurovascular arrangement positions the artery as both a conduit and amplifier of trigeminovascular and immune signaling during migraine attacks.

Experimentally, preclinical studies demonstrate that mediators such as calcitonin gene–related peptide, pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide, and purinergic ligands modulate MMA dilation, receptor activation, and neurogenic inflammation [

16,

17,

18]. These mechanistic findings, derived from rodent models and complementary studies using human neurosurgical tissue, reinforce the biological plausibility of targeting the MMA pharmacologically.

7.3. Translational and Pharmacologic Implications

Intra-arterial pharmacological approaches directed at the MMA offer a unique opportunity to intervene at distinct stages of the migraine cascade. Although direct human MMA pharmacology studies remain limited, related vascular experiments help contextualize these mechanisms. For example, an ex vivo pharmacologic analysis using isolated human coronary artery segments demonstrated that calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonism produces measurable, tissue-specific vascular effects across human arterial beds [

19]. While not conducted in the MMA, these findings support the broader principle that CGRP-responsive vascular structures can be modulated directly in a manner consistent with observations from preclinical MMA studies [

16,

17,

18].

Animal and translational studies further elucidate receptor distributions, vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide signaling, calcitonin gene–related peptide release, and the responsiveness of the MMA to vasoactive challenges [

16,

17,

18]. Collectively, these data demonstrate consistent acute changes in arterial diameter and inflammatory mediator release across species and experimental contexts.

7.4. Clinical Signal and Therapeutic Strategies

Complementary clinical observations indicate that intra-arterial calcium channel blockers can interrupt excessive vasomotion, while intra-arterial lidocaine appears capable of suppressing trigeminal neuronal activity and mast cell degranulation. These mechanisms are believed to underlie the rapid symptom relief reported in several small observational case series [

5,

6,

7,

8,

11,

20]. Although durability and comparative efficacy remain uncertain, these early experiences provide proof of concept that the MMA can be safely accessed and pharmacologically modulated in select patient populations.

The future of MMA–targeted interventions likely lies in therapies that exploit immunological and neuroinflammatory cascades, reflecting a broader shift in migraine science away from purely vascular stabilization and toward immune-based modulation. Early clinical experiences, ranging from intra-arterial lidocaine infusion to MMA embolization, demonstrate procedural feasibility and therapeutic promise, while the exploration of additional molecular targets such as purinergic receptors further highlights the central role of the MMA in migraine biology [

8,

12,

13,

16].

7.5. Limitation and Safety Considerations

To date, MMA–based embolization and intra-arterial pharmacologic therapies for migraine are limited by predominantly observational study designs, small sample sizes, and short follow-up intervals [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

11,

12,

13,

14,

20]. The clinical evidence base is largely derived from single-center experiences and small cohorts, with randomized comparative data remaining scarce [

8,

11,

12,

13,

20]. The largest published series evaluating intra-arterial lidocaine infusion via the MMA artery included forty-five patients and lacked both randomization and a control arm, leaving uncertainty regarding the durability of benefit beyond several months [

8,

23]. MMA embolization for migraine has similarly been reported only in small prospective self-controlled cohorts with limited follow-up, and no large randomized controlled trials in migraine have yet been published [

12,

13]. These limitations constrain conclusions regarding comparative efficacy relative to conventional medical or surgical management, optimal embolic agent selection, and long-term durability of clinical benefit [

8,

11,

12,

13,

20]. In addition, delayed complications such as late recanalization, chronic dural ischemia, or progressive cranial neuropathy may be underrepresented due to limited longitudinal surveillance [

21,

22]. We recommend the development of adequately powered clinical trials incorporating blinding or sham control, standardized clinical endpoints, and extended longitudinal follow-up to more concretely define efficacy, safety, and durability.

Patient selection also represents an additional source of uncertainty. Many reported series exclude individuals with complex external–internal carotid anastomoses, advanced atherosclerotic disease, or prior cranial interventions, potentially biasing safety estimates toward lower-risk populations [

12,

21,

22]. The applicability of published outcomes to older patients, those with significant vascular comorbidity, or those requiring repeat embolization therefore remains incompletely defined.

For headache-directed interventions, the mechanism by which MMA–delivered lidocaine confers analgesia is incompletely understood, and it remains unclear whether symptom relief reflects local dural nociceptor modulation, transient neural blockade, or secondary vascular effects [

11,

15,

20]. The absence of standardized dosing regimens and outcome measures further complicates cross-study comparison and limits conclusions regarding reproducibility and durability of response [

8,

11,

15].

Finally, while procedural complication rates are consistently reported as low, the rarity of serious adverse events necessitates cautious interpretation, as even large single-center experiences may be underpowered to detect uncommon but clinically significant outcomes [

21,

22]. As adoption increases, multicenter registries and prospective trials will be essential to more accurately define risk profiles, refine patient selection criteria, and establish standardized technical and pharmacologic protocols.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; methodology, J.S and C.G.L; formal analysis, J.S.; investigation, J.S. and C.G.L..; resources, J.S. and C.G.L; writing—original draft preparation, J.S, C.G.L, D.S.; writing—review and editing, J.S, C.G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Christensen, C.E.; Younis, S.; Lindberg, U.; et al. Intradural artery dilation during experimentally induced migraine attacks. Pain 2021, 162, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorella, D.; Monteith, S.J.; Hanel, R.; et al. Embolization of the middle meningeal artery for chronic subdural hematoma. N Engl J Med 2025, 392, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.M.; Knopman, J.; Mokin, M.; et al. Adjunctive middle meningeal artery embolization for subdural hematoma. N Engl J Med 2024, 391, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstner, M.; Linn, J.; Müller-Schunk, S.; Straube, A. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a complicated clinical course treated with intra-arterial application of nimodipine. Cephalalgia 2009, 29, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, H.; Tatum, J.K.; Wong, C.; et al. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: treatment with combined intra-arterial verapamil infusion and intracranial angioplasty. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011, 32, E184-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospel, J.M.; Wright, C.H.; Jung, R.; et al. Intra-Arterial Verapamil Treatment in Oral Therapy-Refractory Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020, 41, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeiros, J.M.; Roa, J.A.; Sabotin, R.P.; et al. Quantifying Intra-Arterial Verapamil Response as a Diagnostic Tool for Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020, 41, 1869–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattar, N.K.; Arthur, A.S.; Santori, D.; et al. Middle meningeal artery lidocaine infusion for refractory headache. J Neurointerv Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, A.; Bains, N.; Bhatti, I.; et al. Abstract TMP6: Intra-arterial Lidocaine Administration of Lidocaine in Middle Meningeal Artery for Treatment of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage-Related Headaches. Stroke 2025, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirakov, A.; Ninov, K.; Sirakova, K.; Sirakov, S.S. Blazing the trail! Commentary on “Intra-arterial lidocaine administration in middle meningeal artery for short-term treatment of subarachoid hemorrhage-related headaches” by Qureshi et al. Interv Neuroradiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.I.; Pfeiffer, K.; Babar, S.; et al. Intra-arterial injection of lidocaine into middle meningeal artery to treat intractable headaches and severe migraine. J Neuroimaging 2021, 31, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catapano, J.S.; Karahalios, K.; Srinivasan, V.M.; et al. Chronic headaches and middle meningeal artery embolization. J Neurointerv Surg 2022, 14, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanzin, J.R.; Manzato, L.B. Chronic migraine and bilateral occlusion of the middle meningeal artery. Interv Neuroradiol 2025, 15910199251337520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaikumar, V.; Moser, M.; Lim, J.; et al. Advanced Treatment Approach: Intra-arterial Lidocaine Injection and Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization With Onyx for Relief of Refractory Migraine: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2025.

- Mancuso-Marcello, M.; Qureshi, A.I.; Nikola, C.; et al. Intra-arterial lidocaine therapy via the middle meningeal artery for migraine headache: Theory, current practice and future directions. Interv Neuroradiol 2023, 15910199231195470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haanes, K.A.; Labastida-Ramírez, A.; Blixt, F.W.; et al. Exploration of purinergic receptors as potential anti-migraine targets using established pre-clinical migraine models. Cephalalgia 2019, 39, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boni, L.J.; Ploug, K.B.; Olesen, J.; et al. The in vivo effect of VIP, PACAP-38 and PACAP-27 and mRNA expression of their receptors in rat middle meningeal artery. Cephalalgia 2009, 29, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.K.; Gupta, S.; Olesen, J.; Jansen-Olesen, I. PACAP-38 infusion causes sustained vasodilation of the middle meningeal artery in the rat: possible involvement of mast cells. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, T.; Boucherie, D.M.; van den Bogaerdt, A.; et al. Blocking the CGRP Receptor: Differences across Human Vascular Beds. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.I.; Qureshi, M.H.; Khan, A.A.; Suri, M.F.K. Effect of intra-arterial injection of lidocaine and methyl-prednisolone into middle meningeal artery on intractable headaches. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2014, 7, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Vollherbst, D.F.; Berlis, A.; Zaki, M.; et al. Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization for the Treatment of Chronic Subdural Hematomas—a German Nationwide Multi-center Study On 718 Embolizations. Clin Neuroradiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoville, J.P.; Joyce, E.; Tonetti, D.A.; et al. Radiographic and clinical outcomes with particle or liquid embolic agents for middle meningeal artery embolization of nonacute subdural hematomas. Interv Neuroradiol. 2023, 29, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattar, N.K.; Arthur, A.S.; Santori, D.; et al. Middle meningeal artery lidocaine infusion for refractory headache. J Neurointerv Surg 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.J.; Stovner, L.J.; Jensen, R.; Uluduz, D.; Katsarava, Z. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women. J Headache Pain. 2020, 21, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buse, D.C.; Lipton, R.B. Global perspectives on the burden of episodic and chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2013, 33, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodick, D.W. Migraine. Lancet 2018, 391, 1315–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipton, R.B.; Bigal, M.E. Migraine: epidemiology, impact, and risk factors for progression. Headache 2005, 45 Suppl 1, S3–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).