1. Introduction

2,2,2-Trifluoroethanol (TFE) and 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) are two fluorinated alcohols used as cosolvents for structural stabilization of secondary structure-forming peptides. In particular, NMR and CD studies show that their presence increases the population of

-helix and

-sheet content.[

1,

2,

3] The factors influencing the efficacy of structure-inducing cosolvents are their concentration in aqueous solution and the amino acid sequence of the peptide.

Computational and experimental techniques have investigated the mechanism of peptide stabilization by fluorinated solvents.[2,3,4,5] As stated in the review [2], there is as yet no single mechanism that accounts for all of the effects TFE and related cosolvents have on polypeptide conformation. In an early MD study of Mellitin in 30% (vol/vol) TFE/water mixtures, Roccatano er al. proposed an helix-stabilization mechanism whereby a layer of cosolvent molecules is formed around the peptide, which reduces the accessibility of water molecules and, consequently, increases the stability of the intermolecular hydrogen bonds between carbonyl and amide NH groups, as well as the secondary structure. In addition, the cosolvent molecules’ layer causes a lowering of the dielectric constant. The formation of clusters of cosolvent molecules has also been described in water as the concentration of the organic cosolvent increases.[

3]

To study the structural and dynamic properties of peptides in biomimetic media and cosolvent molecules in water at the molecular level, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations can be used.[

4,

6,

7] To accurately reproduce experimental findings, MD simulations need an accurate Force Field (FF),[

8,

9,

10,

11] which is characterized by a set of functional forms with a minimal set of adjustable parameters. In the present study, we make use of the refined FF recently proposed by some of us for TFE, HFIP and 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-one (HFA) fluorinated alcohols.[

12] The upgraded FF is based on General AMBER Force Field 2[

13,

14] with parameterization of atomic charges using

ab initio calculations on stable conformers previously identified using single–point energy evaluations on selected dihedral angles. To verify the accuracy of the FF to describe the structural and thermodynamic properties of cosolvent/water solutions, MD simulations with the upgraded FF were performed on TFE and HFIP water solutions with a concentration from 0 to 100% of TFE and HFIP. Furthermore, to study the secondary structure stabilization effect, MD simulations were performed on cosolvent/water solutions with a peptide. The peptide used was Mellitin (MLT), which is a 26-residue amphiphilic peptide (GIGAVLKVLTTGLPALISWIKRKRQQ) and is the principal component of the venom of

Apis mellifera. In pure water, at pH 4, MLT is unfolded[

15] while it assumes a helical conformation when it is bound to the membrane as well as in alcohol solutions.[

16] MLT consists of two

-helical regions, and these portions are connected by the residues Thr-11 and Gly-12.

The paper is organized as follows. In the "Methods" section, we describe MD simulations in some detail. In the section "Results and Discussion", we present the results obtained using the upgraded FF, and a critical assessment of them. Conclusive remarks and perspective are discussed in the "Conclusions" section.

2. Methods

2.1. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

To study the properties of cosolvent/water solutions, we used concentrations of 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90% (v/v) of TFE and HFIP. In addition, we also considered a pure solution of TFE and HFIP (Figure S1 of Supporting Information (SI)). To obtain the different concentrations of cosolvent/water solutions, we used the number of cosolvent and water molecules reported in

Table 1. The total number of molecules for all the simulated systems was 6000. The starting coordinates were generated using GROMACS standard tools[

17] and inserting a specified number of molecules in random positions.

For the simulation of MLT in cosolvent/water mixtures, we considered 10:90, 20:80, 30:70, 40:60, and 50:50 (v/v) cosolvent/water solutions, maintaining the same number of TFE, HFIP, and H

O molecules reported in

Table 1. MLT (pdb identification code 2MLT) was parametrized using AMBER99SB-ILDN FF;[

18] the two cosolvents with the upgraded FF[

12] and the water molecules with the 3-site TIP3P model.[

19,

20] For all systems, simulations were performed with a cubic box with periodic boundary conditions using GROMACS 2025.1.[

17] First, the steepest descent energy minimization was applied. The systems were then heated to 298.15 K for 1 ns while keeping the temperature constant using a V-rescale[

21] with a coupling time constant of 1 ps. The resulting configuration was used as a starting point for an NPT simulation (using the C-rescale exponential relaxation pressure coupling) with a period of pressure fluctuations at the equilibrium setting at 2.0 ps until the systems were allowed to converge to uniform density (2 ns, time-step 1 fs). The production run in the NPT ensemble was carried out for 100 ns with

t = 2.0 fs, imposing rigid constraints only on the X–H bonds (with X being any heavy atom) by means of the LINCS algorithm.[

22] In addition to the calculation of the static dielectric constant, we also performed a NVT ensemble simulation (2ns, time-step 1 fs) starting from the last configuration of the previous NPT simulation. For all simulations, electrostatic interactions were evaluated using the particle-mesh Ewald (PME)[

23] method with a grid spacing of 1.2 Å, a real-space cutoff of 1.2 nm, and a spline interpolation of order 4. Van der Waals interactions were calculated using a cut-off of 1.0 nm. Long-range dispersion corrections for Lennard-Jones interactions were used for energy and pressure.[

17,

24] The procedure just described was performed considering the two cosolvents and several cosolvent/water solutions; therefore, we conducted an extensive study using 3.1

s atomic-detail molecular dynamics simulations.

Static dielectric constant (

), density (

), Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), and intermolecular Radial Distribution Functions (RDFs) were determined using GROMACS standard tools.[

17] In particular for

calculation, the total dipole plus fluctuations was used for the estimation according to Equation

1:

where

is the molecular dipole moment.

The secondary structure of MLT and its evolution were analyzed using the Define Secondary Structure of Proteins (DSSP) algorithm[

25]. To describe the interaction of the peptide with the cosolvent, the Local Cosolvent Concentration (LCC) was evaluated from the number of solvent and cosolvent molecules present in a shell of 6 Å around the peptide residues.[

26]

3. Results

3.1. Cosolvent/Water Solutions

In

Table 2, we reported the calculated thermodynamic properties for the cosolvent/water solutions. For both the cosolvents, the density increases and the static dielectric constant decreases with the concentration. The values of density and

at 10 % (v/v) concentration of TFE and HFIP highlight the distinct chemical and structural properties of the two cosolvents: TFE has a higher dipole moment and HFIP a higher molecular mass. The values at 50% and 100 % (v/v) are in agreement with those reported in our previous paper.[

12] The experimental values of density at 50% (v/v) are 1170 kg/m

and 1250 kg/m

[

3,

27,

28,

29,

30] for TFE and HFIP, respectively, in agreement with the computed ones. An excellent agreement is found also for density values for TFE and HFIP pure solutions, for which experimental values are 1383 kg/m

and 1607 kg/m

, respectively.

The agreement between the computed and experimental static dielectric constant is worse than that of densities. Analyzing all the computed values reported in

Table 2,

is overestimated for both cosolvents and for lower concentrations (10% and 20% (v/v)) and is underestimated for concentrations higher than 50%. The best agreement is obtained at 30%, 40% and 50% (v/v) concentrations and especially for TFE. However, the difference between computed and experimental

values was also found in previous studies. It was ascribed to insufficient sampling, and/or to the absence of an explicit polarization term in the FF.[

6,

7] Furthermore, to obtain comparable values of

using MD simulation is not easy, as was pointed out also in a paper of Caleman

et al. [

31] in which the dielectric constant has been defined “the hardest nut to crack".[

32]

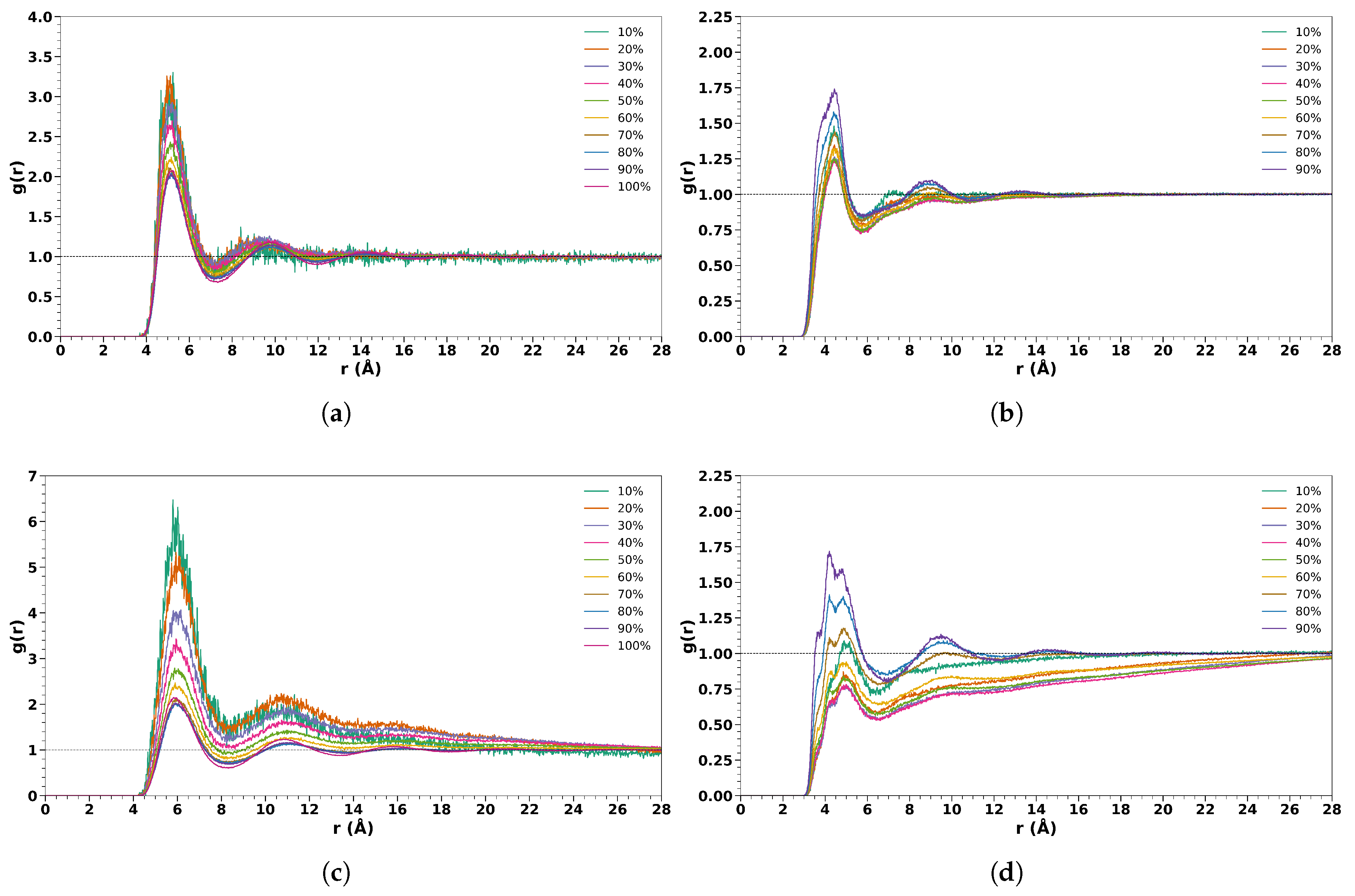

In

Figure 1, we reported the RDFs between the Center Of Mass (COM) of TFE-TFE, TFE-Water, HFIP-HFIP, and HFIP-Water. In all the analyses, there is a dependence on the concentration of the cosolvents. The average number of TFE molecules at 7.2 Å (first minimum of the RDF) from a reference TFE molecule ranges from 1.6 to 12.3 for 10% (v/v) to 100 % (v/v) TFE/water solutions. A similar trend was also found for HFIP mixtures with an average number of HFIP at 8.4 Å, ranging from 3.5 to 13.2 for 10% (v/v) to 100% (v/v) HFIP/water solutions. As expected, an opposite trend was found for the average number of water molecules at 5.6 Å from a reference TFE molecule and at 6.7 Å from a reference HFIP molecule, with values ranging from 18.2 to 2.4 for TFE and from 25.8 to 4.2 for HFIP for 10% (v/v) to 90% (v/v) cosolvent/water solutions (all values are reported in Table S1 of SI).

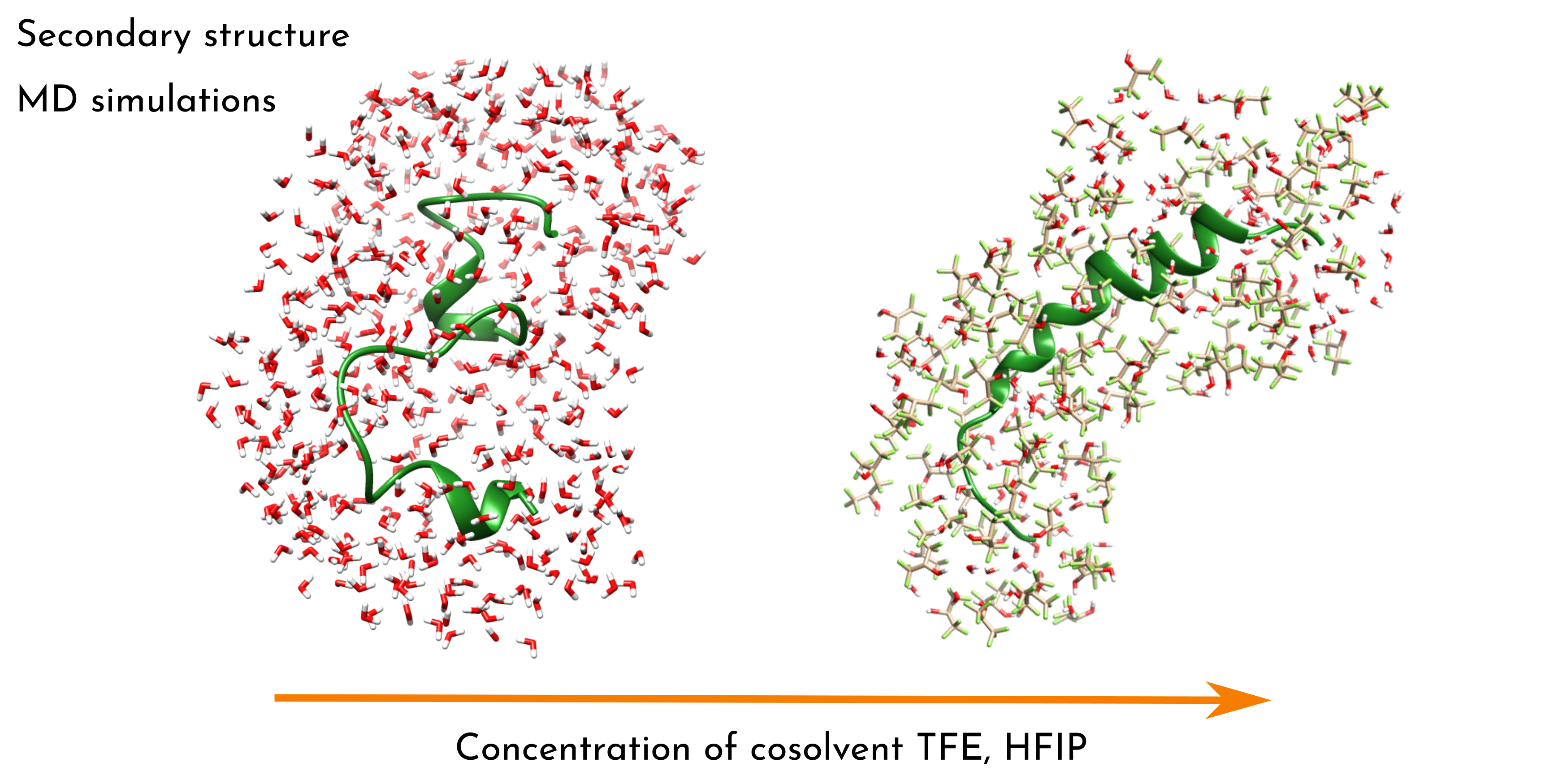

3.2. Melittin in Cosolvent/Water Solutions

To study the secondary structure stabilization effect of TFE and HFIP, we performed MD simulations of MLT peptide in five different cosolvent/water solutions (10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50%) and in pure water, although some studies[

3,

33] suggest that a concentration of around 30% is optimal for inducing secondary structure stabilization in peptides and proteins. In

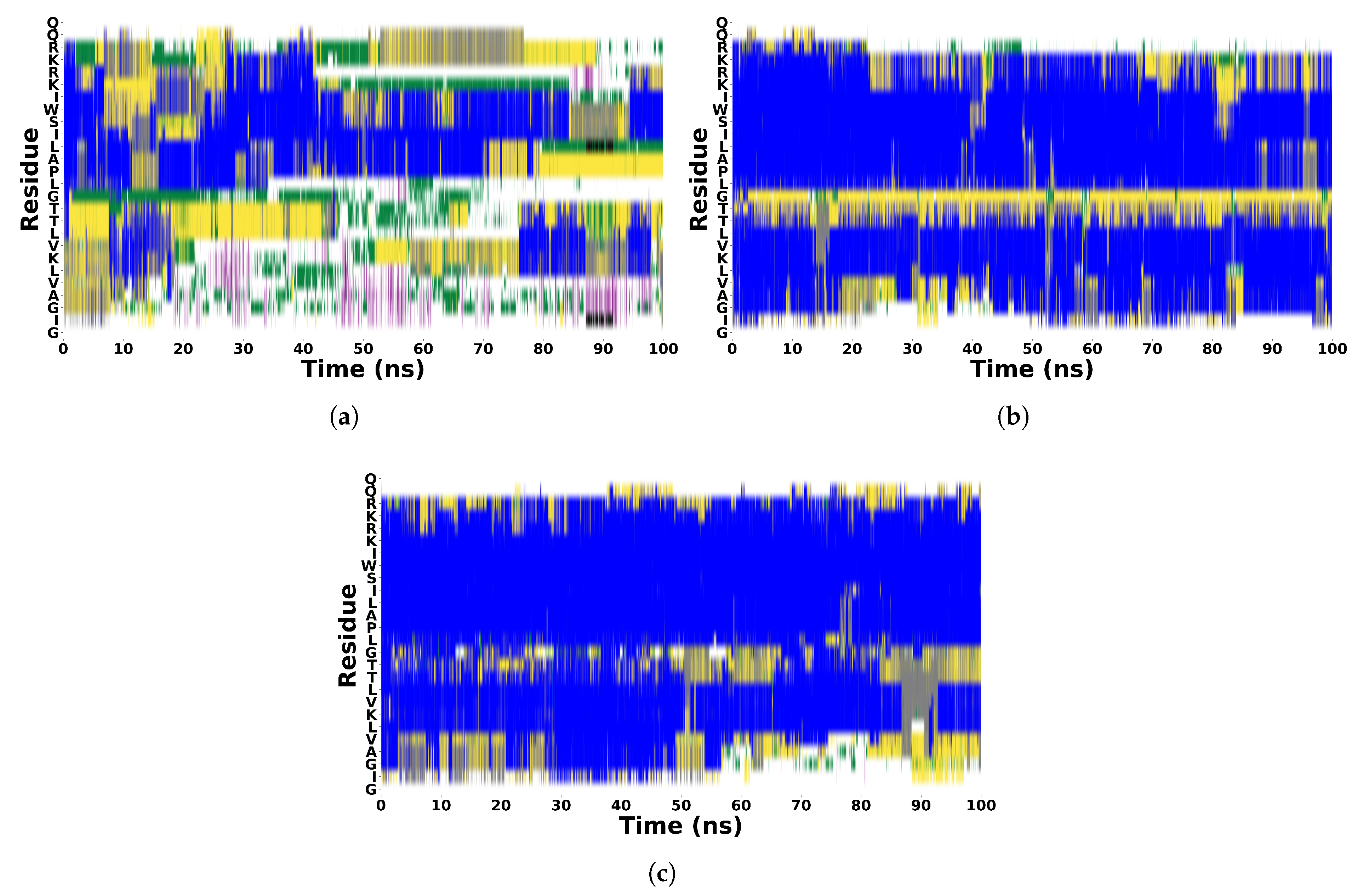

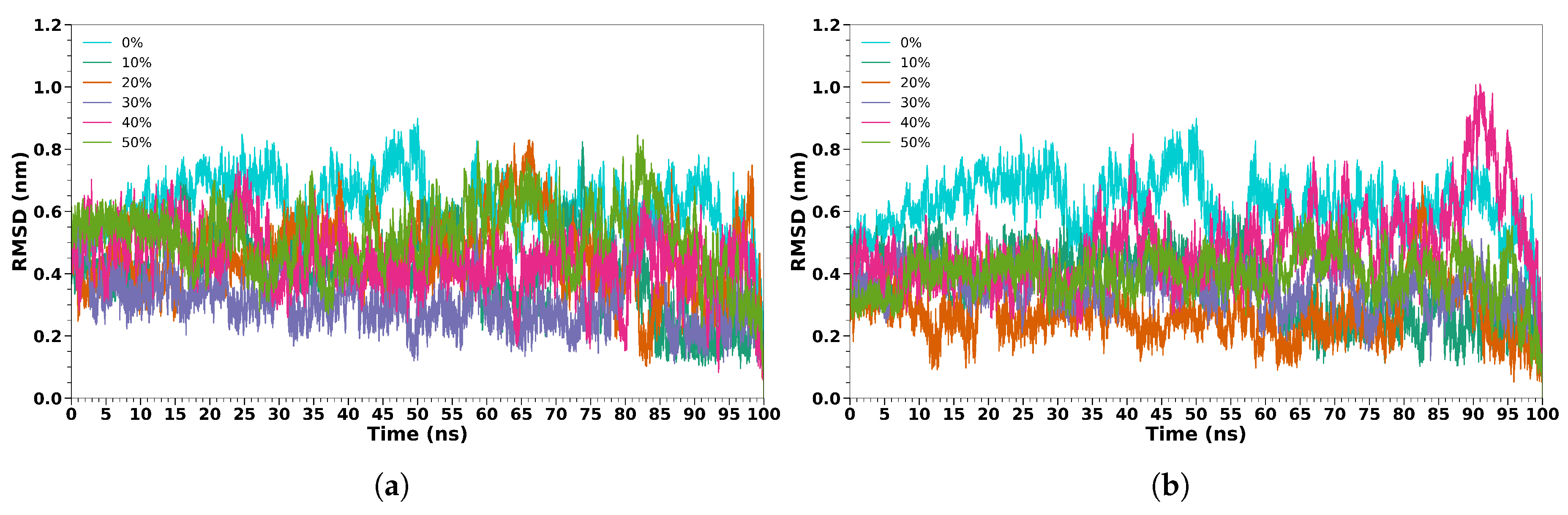

Figure 2, we reported the MLT backbone RMSD calculated in all concentrations for the two cosolvents. As expected, in water, the RMSD reaches the highest values during the 100 ns of the simulation. In TFE, the lower value is found when the MLT is dissolved in the 30% (v/v) cosolvent/water solution; in HFIP, when the concentration is 20%. Interestingly, for higher concentrations, such as 40% or 50% (v/v) cosolvent/water solutions, the RMSD is higher, although always lower than 0.7 Å. To study in more detail the evolution of the MLT secondary structure, in

Figure 3 we reported the DSSP of MLT in water, 30% (v/v) TFE/water, and 30% (v/v) HFIP/water solutions (the results for the other concentrations are reported in Figure S2 to S9 of SI). The DSSP calculation for MLT in aqueous solutions confirms the unstable structure already found in the RMSD analysis. The structure remains unstable throughout the simulation; a hint of an

-helix is observed in the region between Pro-14 and Trp-19, but it is not stable. For TFE and HFIP (30% (v/v)), a well-defined flexible region from Thr-11 to Leu-13 connects two

helical regions. The two

-helices are stable during the 100 ns MD simulations. For the cosolvent concentrations lower than 30 %, in HFIP we observe a similar pattern to the 30% (v/v) concentration, while in TFE the two

helical regions involve a smaller number of aminoacids, particularly in the first segment (from Gly-1 to Thr-10) where the first residues are disordered. In the concentration higher than 30 %, in both cosolvents, the first segment exhibits disorder, and the flexible region connecting the two

helical regions involves a larger number of aminoacids.

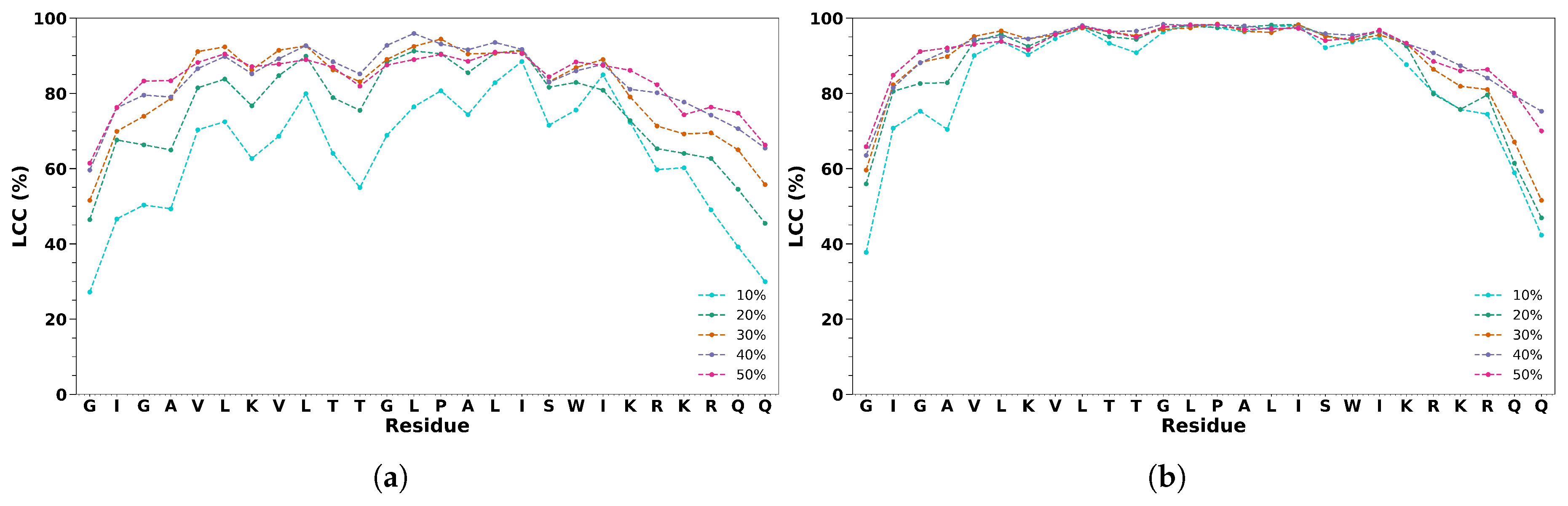

To verify the formation of a layer of cosolvent molecules around MLT, we calculated the LCC around the C

atom of each residue of the peptide at 6 Å (

Figure 4). For TFE, we found a marked change with the cosolvent concentration. For the 10% (v/v) concentration, the first and the last residues, as well as the connecting residues (Thr-11 and Gly-12), show lower values of LCC reaching the value of 50 %. For the other concentrations, the values of LCC grow, retaining values of 50% and 60 % for the first and last residues. The net decrease around the flexible region (Thr-11 and Ile-20) is evident for all the concentrations. For HFIP, we have a similar trend for all the concentrations: smaller values of LCC for the first two and the last three residues, and a value around 90% for the residues from 5 to 21. Also in this case, we have a decrease around the flexible region (Thr-11 and Ile-20). The difference between the two solvents can be ascribed to the difference in the dipole moment and to the presence of two -CF

groups in HFIP.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we have shown the results obtained performing molecular dynamics simulations using an upgraded GAFF2 force field to simulate TFE and HFIP water solutions at several concentrations. The same force field has also been used to simulate Mellitin in several cosolvent/water mixtures to verify its efficacy in stabilizing the secondary structure. Thermodynamic properties of cosolvent/water solutions are in agreement with experimental findings, although the calculation of the static dielectric constant requires in-depth analysis. The new force field allows a correct description of the secondary structure of MLT in a range of concentrations of 10% to 50% v/v of cosolvent, showing that maximum helical stabilization is reached for biosolvent concentration of 30 % v/v in full agreement with experimental evidence. The different analyses performed on molecular dynamics simulations afford an accurate characterization the structure of the peptide and the spatial organization of cosolvent around the MLT, showing that TFE/HFIP molecules cluster near the central peptide backbone and side chains, displacing bulk water. In particular, for biosolvent concentration in the range 30%-40% v/v, we showed that the TFE/HFIP “coating” of MLT increases in the inner residues leaving the C- and N-termini more exposed to water. Our results provide a thorough and convincing explanation of the stabilization effect of the helical structure in MLT promoted by the mixing of biosolvents in water.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and M.M.; methodology, M.C., M.P., P.P., M.M.; validation, M.C., M.P., C.A., A.M.P, P.P., M.M.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C. and M.M.; resources, C.A. and A.M.P.; data curation, M.C. and M.M.; writing, review and editing, M.C., M.P., C.A., A.M.P, P.P., M.M.; visualization, M.C.; supervision, M.P., P.P., M.M.; project administration, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Supporting Information available: Molecular structure of TFE and HFIP; Average number of cosolvent and water molecules calculated at the first minimum of g(r); Evolution of secondary structure from DSSP algorithm of MLT in TFE/water and HFIP/water solutions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank MUR-Italy ("Progetto Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023-2027" allocated to Department of Chemistry "Ugo Schiff") and the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Mission 4 Component 2 - Investment 1.4 - NATIONAL CENTER FOR HPC, BIG DATA AND QUANTUM COMPUTING - funded by the European Union - NextGenerationEU - CUP B83C22002830001. Calculations were performed in the LEONARDO HPC cluster, for which we acknowledge the CINECA award under the ISCRA initiative (HP10C06NZI), for the availability of high-performance computing resources and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Searle, M.S.; Zerella, R.; Williams, D.H.; Packman, L.C. Native-like β-hairpin structure in an isolated fragment from ferredoxin: NMR and CD studies of solvent effects on the N-terminal 20 residues. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 1996, 9, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, M. Trifluoroethanol and colleagues: cosolvents come of age. Recent studies with peptides and proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1998, 31, 297–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.P.; Hoshino, M.; Kuboi, R.; Goto, Y. Clustering of fluorine-substituted alcohols as a factor responsible for their marked effects on proteins and peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 8427–8433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccatano, D.; Colombo, G.; Fioroni, M.; Mark, A.E. Mechanism by which 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol/water mixtures stabilize secondary-structure formation in peptides: a molecular dynamics study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 12179–12184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, L.S.; Pande, J.; Shekhtman, A. Helical Structure of Recombinant Melittin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 356–368. [Google Scholar]

- Fioroni, M.; Burger, K.; Mark, A.E.; Roccatano, D. Model of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-propan-2-ol for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 10967–10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioroni, M.; Burger, K.; Mark, A.E.; Roccatano, D. A New 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol Model for Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 12347–12354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchiagodena, M.; Mancini, G.; Pagliai, M.; Del Frate, G.; Barone, V. Fine-tuning of atomic point charges: Classical simulations of pyridine in different environments. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 677, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchiagodena, M.; Mancini, G.; Pagliai, M.; Cardini, G.; Barone, V. New atomistic model of pyrrole with improved liquid state properties and structure. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2018, 118, e25554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchiagodena, M.; Pagliai, M.; Andreini, C.; Rosato, A.; Procacci, P. Upgraded AMBER Force Field for Zinc-Binding Residues and Ligands for Predicting Structural Properties and Binding Affinities in Zinc-Proteins. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 15301–15310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchiagodena, M.; Pagliai, M.; Andreini, C.; Rosato, A.; Procacci, P. Upgrading and Validation of the AMBER Force Field for Histidine and Cysteine Zinc(II)-Binding Residues in Sites with Four Protein Ligands. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 3803–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casoria, M.; Macchiagodena, M.; Rovero, P.; Andreini, C.; Papini, A.M.; Cardini, G.; Pagliai, M. Upgrading of the general AMBER force field 2 for fluorinated alcohol biosolvents: A validation for water solutions and melittin solvation. J. Pept. Sci. 2024, 30, e3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wolf, R.M.; Caldwell, J.W.; Kollman, P.A.; Case, D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1157–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GAFF and GAFF2 are public domain force fields and are part of the AmberTools23 distribution, available for download at https://ambermd.org/ internet address (accessed 23). According to the AMBER development team, the improved version of GAFF, GAFF2, is an ongoing project aimed at “reproducing both the high-quality interaction energies and key liquid properties such as density, the heat of vaporization and hydration free energy”. GAFF2 is expected “to be an even more successful general purpose force field and that GAFF2-based scoring functions will significantly improve the success rate of virtual screenings". 20 May.

- Kemple, M.D.; Buckley, P.; Yuan, P.; Prendergast, F.G. Main chain and side chain dynamics of peptides in liquid solution from 13C NMR: melittin as a model peptide. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 1678–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, N.; Mizuno, K.; Goto, Y. Group additive contributions to the alcohol-induced α-helix formation of melittin: implication for the mechanism of the alcohol effects on proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 275, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1-2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindorff-Larsen, K.; Piana, S.; Palmo, K.; Maragakis, P.; Klepeis, J.L.; Dror, R.O.; Shaw, D.E. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins 2010, 78, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, M.; Macchiagodena, M.; Procacci, P.; Cardini, G. Evidence of a Low–High Density Turning Point in Liquid Water at Ordinary Temperature under Pressure: A Molecular Dynamics Study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 6414–6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.; Fraaije, J.G. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N·log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.P.; Tildesley, D.J. Computer Simulation of Liquids; 1987.

- Kabsch, W.; Sander, C. Dictionary of Protein Secondary Structure: Pattern Recognition of Hydrogen-bonded and Geometrical Features. Biopolymers 1983, 22, 2577–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roccatano, D.; Fioroni, M.; Zacharias, M.; Colombo, G. Effect of hexafluoroisopropanol alcohol on the structure of melittin: A molecular dynamics simulation study. Protein Science 2005, 14, 2582–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madelung, O. Static Dielectric Constants of Pure Liquids and Binary Liquid Mixtures. Numerical Data and Functional Relationships in Science and Technology 1991, 6, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, C.; Symonds, J. Densities of solutions of four fluoroalcohols in water. J. Fluor. Chem. 1974, 4, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabani, S.; Gianni, P.; Mollica, V.; Lepori, L. Group contributions to the thermodynamic properties of non-ionic organic solutes in dilute aqueous solution. J. Solut. Chem. 1981, 10, 563–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Kelly, C.P.; Thompson, J.D.; Hawkins, G.D.; Chambers, C.C.; Giesen, D.J.; Winget, P.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Minnesota solvation database (MNSOL) version 2012 2020. [CrossRef]

- Caleman, C.; van Maaren, P.J.; Hong, M.; Hub, J.S.; Costa, L.T.; van der Spoel, D. Force Field Benchmark of Organic Liquids: Density, Enthalpy of Vaporization, Heat Capacities, Surface Tension, Isothermal Compressibility, Volumetric Expansion Coefficient, and Dielectric Constant. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchiagodena, M.; Mancini, G.; Pagliai, M.; Barone, V. Accurate prediction of bulk properties in hydrogen bonded liquids: amides as case studies. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 25342–25354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Harris, K.; J. Newitt, P.; J. Derlacki, Z. Alcohol tracer diffusion, density, NMR and FTIR studies of aqueous ethanol and 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol solutions at 25°C. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1998, 94, 1963–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Random Coil

Random Coil  -Helix

-Helix  Bent

Bent  Turn

Turn  5-Helix

5-Helix  3-Helix.

3-Helix.

Random Coil

Random Coil  -Helix

-Helix  Bent

Bent  Turn

Turn  5-Helix

5-Helix  3-Helix.

3-Helix.