Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

11 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

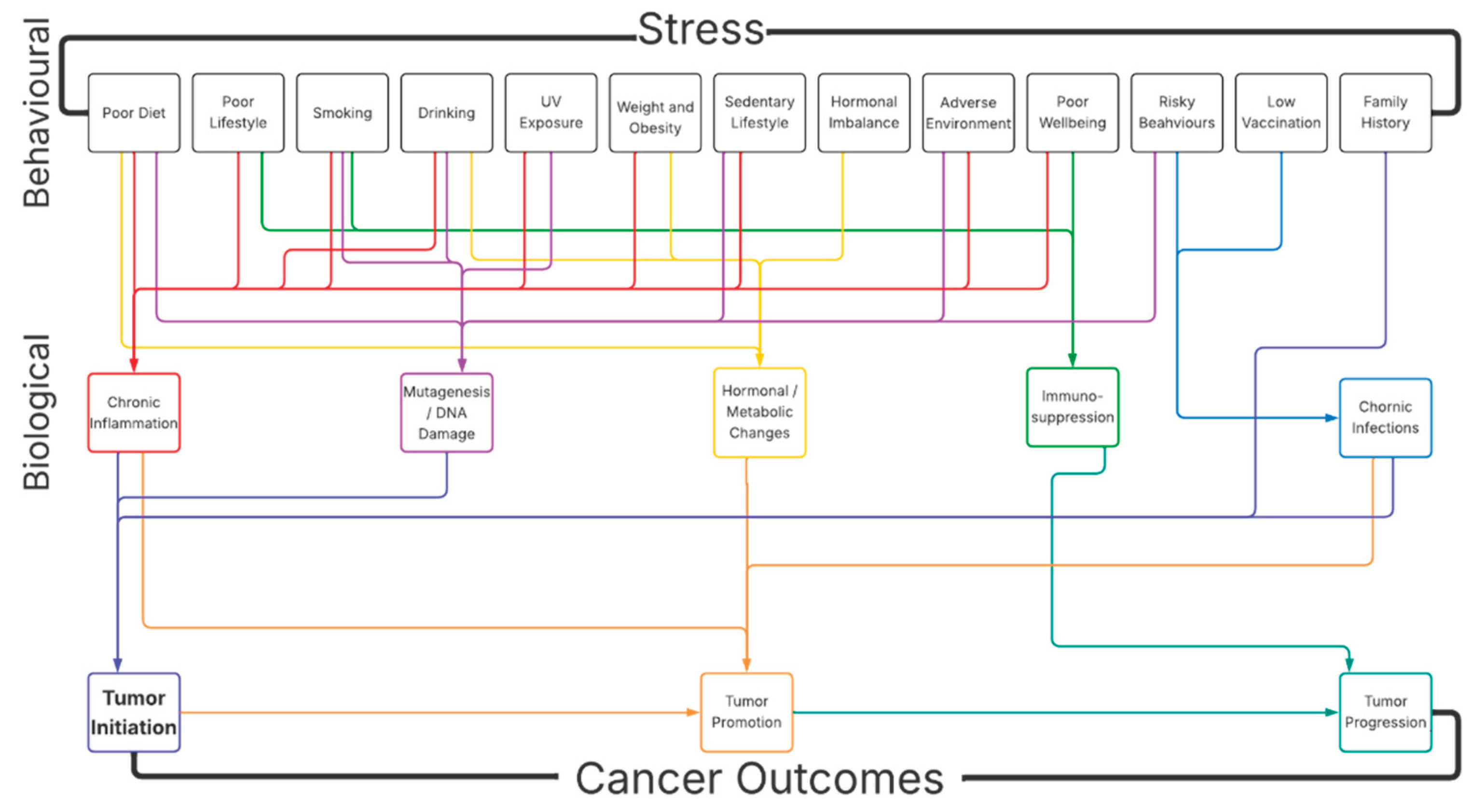

1.1. Stress and Risk for Cancer

1.2. Mechanistic Link Between Stress and Risk for Cancer

1.2.1. Mechanism of Stress-Related Maladaptive Response and Risk for Cancer

1.2.2. Stress-Induced Immunosuppression and Risk for Cancer

1.2.3. Stress-Induced Inflammation and Risk for Cancer

1.3. Indirect Role of Stress in the Risk for Cancer

1.3.1. Diet

1.3.2. Lifestyle

1.3.3. Smoking

1.3.4. Drinking

1.3.5. Sun Exposure

1.3.6. Weight and Obesity

1.3.7. Physical Activity

1.3.8. Family History

1.3.9. Hormones

1.3.10. Environment

1.3.11. Mental and Physical Wellbeing

1.3.12. Vaccination

1.3.13. Risky Behaviors

1.4. Conclusion

References

- Hamer, M.; Chida, Y.; Molloy, G.J. Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 66, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrinović, S.V.; Milošević, M.S.; Marković, D.; Momčilović, S. Interplay between stress and cancer—A focus on inflammation. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1119095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. and R.A. Weinberg, Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell, 2011. 144(5): p. 646-74.

- Suri, D.; Vaidya, V.A. The adaptive and maladaptive continuum of stress responses – a hippocampal perspective. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015, 26, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 5.Holmes, T.H. and R.H. Rahe, The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res, 1967. 11(2): p. 213-8.

- Chida, Y.; Hamer, M.; Wardle, J.; Steptoe, A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat. Clin. Pr. Oncol. 2008, 5, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc-Lapierre, A.; Rousseau, M.-C.; Weiss, D.; El-Zein, M.; Siemiatycki, J.; Parent, M. Lifetime report of perceived stress at work and cancer among men: A case-control study in Montreal, Canada. Prev. Med. 2017, 96, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Qiao, Y.; Xiang, S.; Li, W.; Gan, Y.; Chen, Y. Work stress and the risk of cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 2390–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P.G.; Antoni, M.H.; Lutgendorf, S.K.; Cole, S.W.; Dhabhar, F.S.; E Sephton, S.; Stefanek, M.; Sood, A.K. A biobehavioral perspective of tumor biology. . 2005, 5, 520–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Smith, M.; Lutgendorf, S.K.; Sood, A.K. Impact of Stress on Cancer Metastasis. Futur. Oncol. 2010, 6, 1863–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerling, A.; Ricon-Becker, I.; Sorski, L.; Sandbank, E.; Ben-Eliyahu, S. Stress and cancer: mechanisms, significance and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, E.K., et al., The sympathetic nervous system induces a metastatic switch in primary breast cancer. Cancer Res, 2010. 70(18): p. 7042-52.

- Lu, D.; Andrae, B.; Valdimarsdóttir, U.; Sundström, K.; Fall, K.; Sparén, P.; Fang, F. Psychologic Distress Is Associated with Cancer-Specific Mortality among Patients with Cervical Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 3965–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego, M.; Tyurin, V.A.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Yellets, J.; Nacarelli, T.; Lin, C.; Nefedova, Y.; Kossenkov, A.; Liu, Q.; Sreedhar, S.; et al. Reactivation of dormant tumor cells by modified lipids derived from stress-activated neutrophils. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, L.D.; Rossignoli, M.T.; Delfino-Pereira, P.; Garcia-Cairasco, N.; de Lima Umeoka, E.H. A Comprehensive Overview on Stress Neurobiology: Basic Concepts and Clinical Implications. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gianaros, P.J. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 190–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poller, W.C.; Downey, J.; Mooslechner, A.A.; Khan, N.; Li, L.; Chan, C.T.; McAlpine, C.S.; Xu, C.; Kahles, F.; He, S.; et al. Brain motor and fear circuits regulate leukocytes during acute stress. Nature 2022, 607, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhabhar, F.S. Psychological stress and immunoprotection versus immunopathology in the skin. Clin. Dermatol. 2013, 31, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demers, M.; Suidan, G.L.; Andrews, N.; Martinod, K.; Cabral, J.E.; Wagner, D.D. Solid peripheral tumor leads to systemic inflammation, astrocyte activation and signs of behavioral despair in mice. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0207241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, B.; Liao, Q.; Zhou, M.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Xiong, W.; Li, G.; et al. Chronic Stress Promotes Cancer Development. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.X.; Andrzejak, S.E.; Bevel, M.S.; Jones, S.R.; Tingen, M.S. Exploring racial disparities on the association between allostatic load and cancer mortality: A retrospective cohort analysis of NHANES, 1988 through 2019. SSM - Popul. Health 2022, 19, 101185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinrib, A.Z.; Sephton, S.E.; DeGeest, K.; Penedo, F.; Bender, D.; Zimmerman, B.; Kirschbaum, C.; Sood, A.K.; Lubaroff, D.M.; Lutgendorf, S.K. Diurnal cortisol dysregulation, functional disability, and depression in women with ovarian cancer. Cancer 2010, 116, 4410–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Liu, Y.; Cao, C.; Zeng, Y.; Pan, Y.; Liu, X.; Peng, Y.; Wu, F. Chronic Stress: Impacts on Tumor Microenvironment and Implications for Anti-Cancer Treatments. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, V.B.; Cardoso, D.d.M.; Kayahara, G.M.; Nunes, G.B.; Tjioe, K.C.; Biasoli, É.R.; Miyahara, G.I.; Oliveira, S.H.P.; Mingoti, G.Z.; Bernabé, D.G. Stress hormones promote DNA damage in human oral keratinocytes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidron, Y.; Russ, K.; Tissarchondou, H.; Warner, J. The relation between psychological factors and DNA-damage: A critical review. Biol. Psychol. 2006, 72, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biometry of the temporomandibular joint]. Orthod Fr, 1990. 61 Pt 1: p. 265-78.

- Zong, C.; Yang, M.; Guo, X.; Ji, W. Chronic restraint stress promotes gastric epithelial malignant transformation by activating the Akt/p53 signaling pathway via ADRB2. Oncol. Lett. 2022, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Wang, F.; Yang, R.; Zheng, X.; Gao, H.; Zhang, P. Effect of Chronic Restraint Stress on Human Colorectal Carcinoma Growth in Mice. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, M.; Takahashi, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Saito, T.; Ishida, T.; Serada, S.; Fujimoto, M.; Naka, T.; Wada, N.; et al. Propranolol suppresses gastric cancer cell growth by regulating proliferation and apoptosis. Gastric Cancer 2021, 24, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeid, E.I.; Conzen, S.D. The role of adrenergic signaling in breast cancer biology. Cancer Biomarkers 2013, 13, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, A.; Lopez-Olivo, M.; Dubowitz, J.; Pratt, G.; Hiller, J.; Gottumukkala, V.; Sloan, E.; Riedel, B.; Schier, R. Effect of beta-blockers on cancer recurrence and survival: a meta-analysis of epidemiological and perioperative studies. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 121, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvani, M.; Pelon, F.; Comito, G.; Taddei, M.L.; Moretti, S.; Innocenti, S.; Nassini, R.; Gerlini, G.; Borgognoni, L.; Bambi, F.; et al. Norepinephrine promotes tumor microenvironment reactivity through β3-adrenoreceptors during melanoma progression. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 4615–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.M.A.; Rabelo-Santos, S.H.; Westin, M.C.D.A.; Zeferino, L.C. Tumoral and stromal expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-14, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and VEGF-A in cervical cancer patient survival: a competing risk analysis. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, M.; de Martel, C.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Franceschi, S. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2016, 4, e609–e616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Martel, C. , et al., Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob Health, 2020. 8(2): p. e180-e190.

- Antoni, M.H.; Lutgendorf, S.K.; Cole, S.W.; Dhabhar, F.S.; Sephton, S.E.; McDonald, P.G.; Stefanek, M.; Sood, A.K. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R.; Cole, S.W. Reciprocal regulation of the neural and innate immune systems. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Hidalgo, A.; Sung, C.; Cole, S. Adrenergic inhibition of innate anti-viral response: PKA blockade of Type I interferon gene transcription mediates catecholamine support for HIV-1 replication. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2006, 20, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Malarkey, W.B.; Laskowski, B.F.; Rozlog, L.A.; Poehlmann, K.M.; Burleson, M.H.; Glaserb, R. Autonomic and Glucocorticoid Associations with the Steady-State Expression of Latent Epstein–Barr Virus. Horm. Behav. 2002, 42, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, R.; Friedman, S.B.; Smyth, J.; Ader, R.; Bijur, P.; Brunell, P.; Cohen, N.; Krilov, L.R.; Lifrak, S.T.; Stone, A.; et al. The Differential Impact of Training Stress and Final Examination Stress on Herpesvirus Latency at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Brain, Behav. Immun. 1999, 13, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, F.; Fall, K.; Sparén, P.; Adami, H.-O.; Valdimarsdóttir, H.B.; Lambe, M.; Valdimarsdóttir, U. Risk of Infection-Related Cancers after the Loss of a Child: A Follow-up Study in Sweden. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, T.; Wang, J.; Lin, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Levine, A.J.; Hu, W. Chronic restraint stress attenuates p53 function and promotes tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7013–7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, A.N.; Oberyszyn, T.M.; Daugherty, C.; Kusewitt, D.; Jones, S.; Jewell, S.; Malarkey, W.B.; Lehman, A.; Lemeshow, S.; Dhabhar, F.S. Chronic Stress and Susceptibility to Skin Cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, B.W.; Takahashi, R.; Tanaka, T.; Macchini, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Dantes, Z.; Maurer, H.C.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Z.; Westphalen, C.B.; et al. β2 Adrenergic-Neurotrophin Feedforward Loop Promotes Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 75–90.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, G.L.; Delgado, B.; Tretiakova, M.; Cavigelli, S.A.; Krausz, T.; Conzen, S.D.; McClintock, M.K. Social isolation dysregulates endocrine and behavioral stress while increasing malignant burden of spontaneous mammary tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 22393–22398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasen, N.S.; O'LEary, K.A.; Auger, A.P.; Schuler, L.A. Social Isolation Reduces Mammary Development, Tumor Incidence, and Expression of Epigenetic Regulators in Wild-type and p53-Heterozygotic Mice. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010, 3, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Y. , et al., Stressing Out about Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell, 2019. 36(5): p. 468-470.

- Heidt, T.; Sager, H.B.; Courties, G.; Dutta, P.; Iwamoto, Y.; Zaltsman, A.; Muhlen, C.v.Z.; Bode, C.; Fricchione, G.L.; Denninger, J.; et al. Chronic variable stress activates hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrinović, S.V.; Budeč, M.; Marković, D.; Ajtić, O.M.; Jovčić, G.; Milošević, M.; Momčilović, S.; Čokić, V. Nitric oxide-dependent expansion of erythroid progenitors in a murine model of chronic psychological stress. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 153, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhabhar, F.S. Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol. Res. 2014, 58, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.J.; Corr, E.M.; van Solingen, C.; Schlamp, F.; Brown, E.J.; Koelwyn, G.J.; Lee, A.H.; Shanley, L.C.; Spruill, T.M.; Bozal, F.; et al. Chronic stress primes innate immune responses in mice and humans. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109595–109595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yin, L.; Shen, S.; Hou, Y. Inflammation and cancer: paradoxical roles in tumorigenesis and implications in immunotherapies. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nøst, T.H.; Alcala, K.; Urbarova, I.; Byrne, K.S.; Guida, F.; Sandanger, T.M.; Johansson, M. Systemic inflammation markers and cancer incidence in the UK Biobank. Eur. J. Epidemiology 2021, 36, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.S.; Apple, C.G.; Kannan, K.B.; Funk, Z.M.; Plazas, J.M.; Efron, P.A.; Mohr, A.M. Chronic stress induces persistent low-grade inflammation. Am. J. Surg. 2019, 218, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’orazi, G.; Cordani, M.; Cirone, M. Oncogenic pathways activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines promote mutant p53 stability: clue for novel anticancer therapies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 78, 1853–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, J.K.; Yoo, J.-Y. NFκB and STAT3 synergistically activate the expression of FAT10, a gene counteracting the tumor suppressor p53. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 8, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartikasari, A.E.R.; Huertas, C.S.; Mitchell, A.; Plebanski, M. Tumor-Induced Inflammatory Cytokines and the Emerging Diagnostic Devices for Cancer Detection and Prognosis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, A. , et al., IL-6 promotes head and neck tumor metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the JAK-STAT3-SNAIL signaling pathway. Mol Cancer Res, 2011. 9(12): p. 1658-67.

- Chung, S.S.; Wu, Y.; Okobi, Q.; Adekoya, D.; Atefi, M.; Clarke, O.; Dutta, P.; Vadgama, J.V. Proinflammatory Cytokines IL-6 and TNF-αIncreased Telomerase Activity through NF-κB/STAT1/STAT3 Activation, and Withaferin A Inhibited the Signaling in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M.D.; Godbout, J.P.; Sheridan, J.F. Repeated Social Defeat, Neuroinflammation, and Behavior: Monocytes Carry the Signal. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 42, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, K., J. Fornaguera-Trias, and J.F. Sheridan, Stress-Induced Microglia Activation and Monocyte Trafficking to the Brain Underlie the Development of Anxiety and Depression. Curr Top Behav Neurosci, 2017. 31: p. 155-172.

- Ulrich-Lai, Y.M.; Fulton, S.; Wilson, M.; Petrovich, G.; Rinaman, L. Stress exposure, food intake and emotional state. 2015, 18, 381–399. [CrossRef]

- Cortes, M.L.; Louzado, J.A.; Oliveira, M.G.; Bezerra, V.M.; Mistro, S.; Medeiros, D.S.; Soares, D.A.; Silva, K.O.; Kochergin, C.N.; Carvalho, V.C.H.S.; et al. Association between perceived stress and health-risk behaviours in workers. Psychol. Heal. Med. 2020, 27, 746–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayedi, A.; Emadi, A.; Shab-Bidar, S. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Site-Specific Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2018, 9, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asensi, M.T.; Napoletano, A.; Sofi, F.; Dinu, M. Low-Grade Inflammation and Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption: A Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauby-Secretan, B.; Scoccianti, C.; Loomis, D.; Grosse, Y.; Bianchini, F.; Straif, K. Body Fatness and Cancer — Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, Z.; Wassie, M.M.; Mekonnen, T.C.; Reynolds, A.C.; Melaku, Y.A. Difference in Gastrointestinal Cancer Risk and Mortality by Dietary Pattern Analysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, e991–e1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffetta, P. and M. Hashibe, Alcohol and cancer. Lancet Oncol, 2006. 7(2): p. 149-56.

- Schneiderman, N.; Ironson, G.; Siegel, S.D. Stress and Health: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stults-Kolehmainen, M.A.; Sinha, R. The Effects of Stress on Physical Activity and Exercise. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 81–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walser, T.; Cui, X.; Yanagawa, J.; Lee, J.M.; Heinrich, E.; Lee, G.; Sharma, S.; Dubinett, S.M. Smoking and Lung Cancer: The Role of Inflammation. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008, 5, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgendorf, S.K. and A.K. Sood, Biobehavioral factors and cancer progression: physiological pathways and mechanisms. Psychosom Med, 2011. 73(9): p. 724-30.

- Stubbs, B.; Veronese, N.; Vancampfort, D.; Prina, A.M.; Lin, P.-Y.; Tseng, P.-T.; Evangelou, E.; Solmi, M.; Kohler, C.; Carvalho, A.F.; et al. Perceived stress and smoking across 41 countries: A global perspective across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islami, F.; Marlow, E.C.; Thomson, B.; McCullough, M.L.; Rumgay, H.; Gapstur, S.M.; Patel, A.V.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States, 2019. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, J.M.; Parker, M.O. The role of stress-reactivity, stress-recovery and risky decision-making in psychosocial stress-induced alcohol consumption in social drinkers. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 3243–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fell, G.L.; Robinson, K.C.; Mao, J.; Woolf, C.J.; Fisher, D.E. Skin β-Endorphin Mediates Addiction to UV Light. Cell 2014, 157, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agar, N.S.; Halliday, G.M.; Barnetson, R.S.; Ananthaswamy, H.N.; Wheeler, M.; Jones, A.M. The basal layer in human squamous tumors harbors more UVA than UVB fingerprint mutations: A role for UVA in human skin carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 4954–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brash, D.E. Sunlight and the onset of skin cancer. Trends Genet. 1997, 13, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clydesdale, G.J.; Dandie, G.W.; Muller, H.K. Ultraviolet light induced injury: Immunological and inflammatory effects. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2001, 79, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J.; Seidler, A.; Diepgen, T.; Bauer, A. Occupational ultraviolet light exposure increases the risk for the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 164, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, D.C.; Whiteman, C.A.; Green, A.C. Childhood sun exposure as a risk factor for melanoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2001, 12, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, A.C.; Rutsch, L.; Kenausis, K.; Selzer, P.; Zhang, Z. Can an hour or two of sun protection education keep the sunburn away? Evaluation of the Environmental Protection Agency's Sunwise School Program. Environ. Health 2003, 2, 13–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschbacher, K.; Kornfeld, S.; Picard, M.; Puterman, E.; Havel, P.J.; Stanhope, K.; Lustig, R.H.; Epel, E. Chronic stress increases vulnerability to diet-related abdominal fat, oxidative stress, and metabolic risk. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 46, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, S.; Irfan, W.; Jameel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTiernan, A. Mechanisms linking physical activity with cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolin, K.Y.; Yan, Y.; Colditz, G.A.; Lee, I.-M. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.S.; Blackburn, E.H.; Lin, J.; Dhabhar, F.S.; Adler, N.E.; Morrow, J.D.; Cawthon, R.M. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17312–17315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; Phillips, K.-A.; Mooij, T.M.; Roos-Blom, M.-J.; Jervis, S.; Van Leeuwen, F.E.; Milne, R.L.; Andrieu, N.; et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA 2017, 317, 2402–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Nguyen, H.; Michels, D.; Bazinet, H.; Matkar, P.N.; Liu, Z.; Esene, L.; Adam, M.; Bugyei-Twum, A.; Mebrahtu, E.; et al. BReast CAncer susceptibility gene 2 deficiency exacerbates oxidized LDL-induced DNA damage and endothelial apoptosis. Physiol. Rep. 2020, 8, e14481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ravendranathan, N.; Frisbee, J.C.; Singh, K.K. Complex Interplay between DNA Damage and Autophagy in Disease and Therapy. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikfarjam, S.; Singh, K.K. DNA damage response signaling: A common link between cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Cancer Med. 2022, 12, 4380–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedovic, K.; Duchesne, A.; Andrews, J.; Engert, V.; Pruessner, J.C. The brain and the stress axis: The neural correlates of cortisol regulation in response to stress. NeuroImage 2009, 47, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast, C. , Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol, 2012. 13(11): p. 1141-51.

- Loomis, D.; Grosse, Y.; Lauby-Secretan, B.; El Ghissassi, F.; Bouvard, V.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Baan, R.; Mattock, H.; Straif, K. The carcinogenicity of outdoor air pollution. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 1262–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Kawai, N.; Umemoto, T. Preoperative Inspiratory Muscle Training and Postoperative Complications. JAMA 2007, 297, 697–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-H.; You, S.-L.; Chen, C.-J.; Liu, C.-J.; Lee, C.-M.; Lin, S.-M.; Chu, H.-C.; Wu, T.-C.; Yang, S.-S.; Kuo, H.-S.; et al. Decreased Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Hepatitis B Vaccinees: A 20-Year Follow-up Study. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcaro, M.; Castañon, A.; Ndlela, B.; Checchi, M.; Soldan, K.; Lopez-Bernal, J.; Elliss-Brookes, L.; Sasieni, P. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. Lancet 2021, 398, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howren, M.B.; Lamkin, D.M.; Suls, J. Associations of Depression With C-Reactive Protein, IL-1, and IL-6: A Meta-Analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, F.I. , et al., Malignant melanoma. Effects of an early structured psychiatric intervention, coping, and affective state on recurrence and survival 6 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 1993. 50(9): p. 681-9.

- Glaser, R.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).