1. Introduction

HME is a rare autosomal dominant skeletal disorder caused by loss-of-function variants in the

EXT1 (8q24),

EXT2 (11p11–p13), or

EXT3 (19p) genes [

1]. It is characterized by the formation of multiple benign, cartilage-capped bony outgrowths (osteochondromas) that arise from the perichondrium adjacent to regions of actively growing cartilage. The estimated prevalence is approximately 1 in 50,000 individuals [

2,

3]. Also referred to as Hereditary Multiple Osteochondromas (HMO) or Hereditary Deforming Dyschondroplasia, HME exhibits nearly complete penetrance, particularly in males. More than half of affected individuals inherit the condition from a parent, most often the father [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Typically, asymptomatic males do not transmit the pathogenic variant, whereas asymptomatic females may act as silent carriers [

11]. HME accounts for only 5–10% of all cases of exostosis, with most lesions being solitary. Diagnosis is usually established before the age of 10 and occurs more frequently in males, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.5:1 [

5,

6]. Osteochondromas most commonly affect the metaphyseal regions of long bones but may also involve the scapulae, ribs, pelvis, and vertebrae. In contrast, the skull, carpal, and tarsal bones are generally spared [

6,

12]. Clinical severity varies depending on the number, morphology, and anatomical distribution of lesions, as well as the risk of malignant transformation into chondrosarcoma

[2,14,15]. Osteochondromas can impair longitudinal bone growth, leading to limb-length discrepancies, skeletal deformities, and joint complications, particularly at the hip, such as coxa valga, acetabular dysplasia, femoroacetabular impingement, and early-onset osteoarthritis [

12,

16]. Additional complications may include chronic pain, nerve entrapment, restricted mobility, and inflammatory symptoms. Short stature is commonly observed, especially among individuals harboring pathogenic

EXT1 variants [

12]. Management is primarily surgical and includes excision of symptomatic lesions, limb-lengthening procedures, and corrective osteotomies. Surgical intervention is generally reserved for patients with significant functional impairment or when malignant transformation is suspected [

17].

2. Materials and Methods

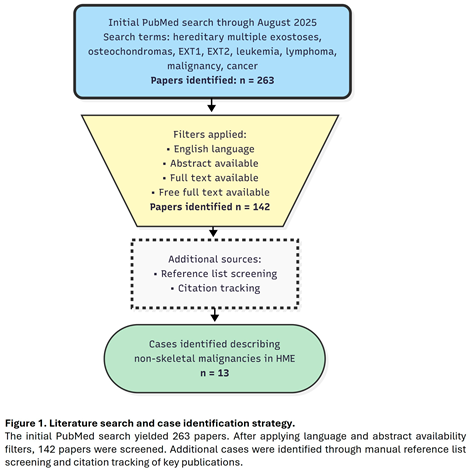

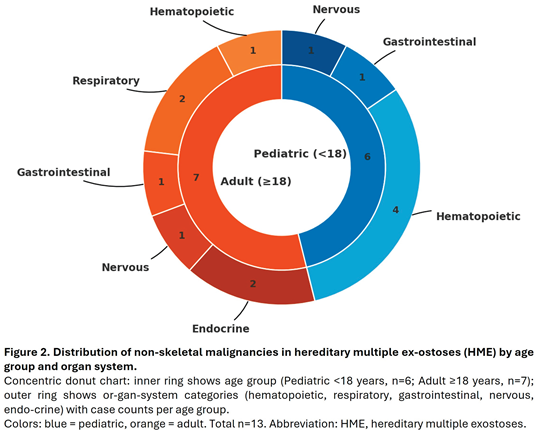

An extensive literature search was conducted using the PubMed database to identify reports of malignancies occurring in individuals with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses. The search, carried out through August 2025, employed combinations of the following terms: “hereditary multiple exostoses,” “osteochondromas,” “EXT1,” “EXT2,” “leukemia,” “lymphoma,” “malignancy,” and “cancer.” No language restrictions were applied. Case reports and case series were included if they described the coexistence of HME and a malignancy other than chondrosarcoma. Reports focusing exclusively on skeletal malignancies were excluded from the analysis of non-skeletal tumors. A total of 13 cases were identified and included in the final analysis (Figure 1). When available, the following data were extracted: patient age and sex, type and anatomical site of malignancy, and findings from any genetic or molecular analyses. Reported malignancies were categorized into five anatomical systems: hematopoietic, respiratory, gastrointestinal, nervous, and endocrine. Data were analyzed descriptively, with particular attention to age distribution and sex differences.

3. Results

3.1. Skeletal Malignancies

The association between HME and skeletal malignancies is well established. Malignant transformation of osteochondromas occurs in approximately 4–10% of affected individuals, with peak incidence in the third decade of life [

18,

19,

20]. Histologically, approximately 94% of these malignant lesions are classified as chondrosarcomas [

17,

21,

22], which are typically low-grade tumors associated with a favorable prognosis; reported long-term survival rates range from 70% to 90% [

18]. Less frequent histological subtypes include osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma [

2]. Notably, carriers of

EXT1 mutations appear to have a higher risk of malignant transformation compared to those with

EXT2 variants [

17].

3.2. Hematologic Malignancies

To date, three cases of leukemia have been reported in association with HME. The first, described in Turkey, involved an 8-year-old girl diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia; no genetic testing was performed [

23]. A second report, from Japan, described a 14-month-old boy with pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia and an

EXT1 deletion. The authors proposed a potential leukemogenic role for the gene alteration [

24]. The third case, reported in Italy, involved a 14-year-old girl with pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia and an

EXT2 mutation. It was suggested that disruption of heparan sulfate biosynthesis due to

EXT2 dysfunction may have contributed to malignant transformation [

25]. Two additional cases of lymphoma have also been reported. One involved a 52-year-old man from Germany with high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the bone [

26], and the other, a 10-year-old boy from the United States diagnosed with abdominal Burkitt lymphoma [

27]. Neither case included molecular genetic analysis.

3.3. Other Malignancies

Two cases of lung cancer have been reported in individuals with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses. The first, published in Russia in 1981, involved a 56-year-old man with a history of heavy smoking and a family history of pulmonary disease. Histological examination identified a squamous cell carcinoma, likely attributable to tobacco exposure [

28,

30]. The second case, reported in China in 2020, concerned a 33-year-old man with no history of smoking or alcohol use who was diagnosed with primary lung adenocarcinoma; a metastatic origin was excluded [

29]. In both cases, no

EXT gene analysis was performed. Two cases of intestinal malignancy were also identified. In 2009, Italian researchers described a 31-year-old man with juvenile-onset colon carcinoma harboring a missense variant in

EXTL3 [

31]. The second case, from Ghana in 2023, involved a 12-year-old boy diagnosed with colorectal cancer; no genetic evaluation was reported [

32]. Sporadic cases of central nervous system tumors have likewise been reported. A 15-year-old boy from the United States was diagnosed with cerebellar astrocytoma [

33], and an 18-year-old male in China was found to have an intracranial atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor [

34]. Neither case included molecular genetic testing. One case of papillary thyroid carcinoma was described in a 36-year-old man from the Netherlands; no

EXT1 or

EXT2 mutations were identified [

2]. Finally, in 2015, a German group reported a case of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) in a 47-year-old man carrying both a novel

EXT1 mutation and a pathogenic variant in the

MEN1 gene [

35].

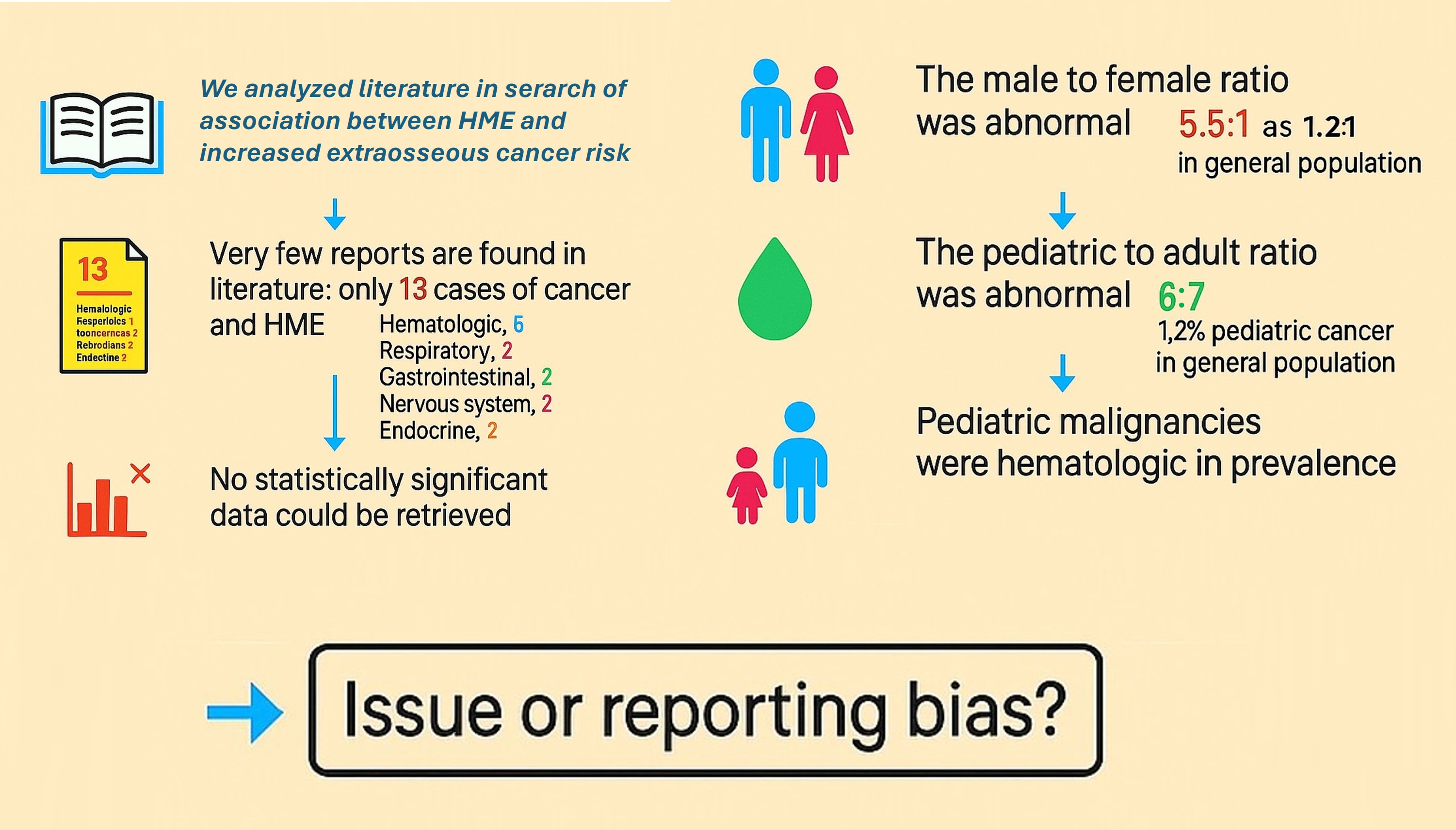

4. Discussion

Our comprehensive literature review identified 13 reported cases of non-skeletal malignancies in individuals with HME. Fewer than half (5/13) underwent genetic or molecular analysis (

Table 1).

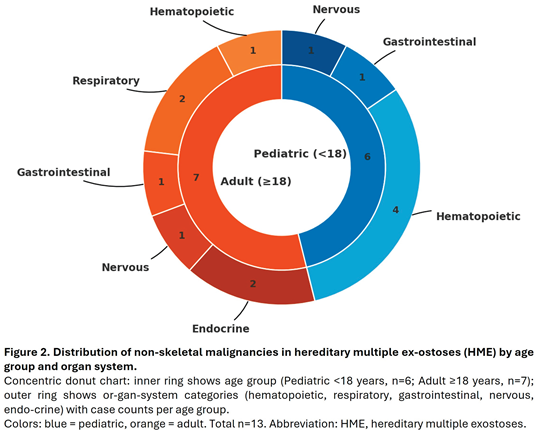

The majority of cases occurred in males (11 males vs. 2 females), yielding a male-to-female ratio of 5.5:1, substantially higher than the 1.2:1 ratio reported in general cancer epidemiology [

36,

37]. The distribution of pediatric versus adult cases (6 vs. 7) contrasts with the expected rarity of childhood cancers, which account for only 1.2% of all malignancies [

38]. Among the six pediatric cases identified, four involved hematologic malignancies (67%), yielding an observed-to-expected ratio of approximately 185, far from the baseline prevalence of hematologic cancers in general pediatric population, which account for 25-30% of childhood malignancies [

38] (Figure 2). This apparent overrepresentation, however, must be interpreted with caution given the small sample size and the substantial influence of publication bias in such rare co-occurrences. The marked male predominance similarly deviates from expected cancer epidemiology patterns, further suggesting selective reporting rather than a true biological association. The observed predominance of pediatric hematologic malignancies warrants cautious interpretation considering potential reporting bias. Malignancy in children is rare, representing only 1.2% of all cancers, and its co-occurrence with HME is likely to prompt case reporting due to perceived novelty. Common adult malignancies in HME patients may lack sufficient clinical interest for publication, leading to systematic underrepresentation. Hematologic malignancies in children are typically managed in specialized centers where genetic workup is more routine, increasing the likelihood of identifying HME as a comorbidity. The mechanistic plausibility of EXT gene involvement in hematopoietic pathways may create confirmation bias favoring publication of leukemia cases. The marked male predominance (11:2) similarly exceeds expected patterns and may reflect preferential reporting rather than genuine sex-specific risk. Without systematic surveillance data or population-based registries, distinguishing true association from publication artifacts remains impossible. Large-scale cohort studies are needed to clarify whether HME confers increased risk for specific non-skeletal malignancies.

5. Study Limitations

This review has several important limitations. The findings are hypothesis-generating, based on only 13 case reports with insufficient statistical power to establish causal associations. The absence of denominator data prevents calculation of incidence rates or relative risks, leaving uncertain whether observed cases represent genuine increased risk or sporadic co-occurrence. Publication bias represents a significant concern, as unusual associations in pediatric populations are preferentially reported, potentially inflating the apparent frequency of hematologic malignancies in children with HME, while common adult cancers co-occurring with HME may be underreported. The observed male predominance may similarly reflect reporting preferences rather than biological predisposition.

Inconsistent genetic testing (5/13 cases) limits genotype-phenotype correlation, and heterogeneity in clinical detail and reporting quality further complicates interpretation. The apparent overrepresentation of pediatric hematologic malignancies should therefore be considered a preliminary observation requiring validation through large-scale, population-based studies with appropriate controls.

6. Conclusions

Based on the currently available evidence, a definitive association between HME and non-skeletal malignancies cannot be established. This review identified an apparent overrepresentation of pediatric hematologic malignancies (4 of 6 pediatric cases), but the small sample size, absence of denominator data, and substantial risk of publication bias limit causal inference. The findings are hypothesis-generating and require validation through large-scale, population-based cohort studies with appropriate controls. Although no screening recommendations can currently be made, clinicians should maintain awareness of potential hematologic malignancies in pediatric patients with HME presenting with unexplained constitutional symptoms. Future research incorporating clinical, genetic, and epidemiological data is essential to determine whether HME confers genuine increased risk for specific non-skeletal cancers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.F.C. and A.M.C.; methodology F.F.C., A.M.C., E.E. and S.S.; validation, F.F.C., A.M.C., E.E. and S.S.; formal analysis, F.F.C., A.M.C., E.E. and S.S..; investigation, F.F.C., A.M.C., E.E.; data curation, A.M.C. and E.E.; writing, original draft preparation, F.F.C., A.M.C.; writing, review and editing, F.F.C., A.M.C.; visualization, E.E., S.S.; supervision, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Francannet C, Cohen-Tanugi A, Le Merrer M, Munnich A, Bonaventure J, Legeai-Mallet L. Genotype-phenotype correlation in hereditary multiple exostoses. J Med Genet. 2001, 38, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bovée JV, Sakkers RJ, Geirnaerdt MJ, Taminiau AH, Hogendoorn PC. Intermediate grade osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma arising in an osteochondroma. A case report of a patient with hereditary multiple exostoses. J Clin Pathol. 2002, 55, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ryckx A, Somers JF, Allaert L. Hereditary multiple exostosis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013, 79, 597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Wicklund CL, Pauli RM, Johnson DR, Hecht JT. Natural history of hereditary multiple exostoses. Am J Med Genet. 1995, 55, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmale GA, Conrad EU, Raskind WH. The natural history of hereditary multiple exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994, 76, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanacci, M. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors; Springer-Verlag Wien GmbH: Bologna, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, L. Hereditary multiple exostosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1963, 45, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno T 1, Ichioka Y, Yagi T, Ishii S. Spindle-cell sarcoma in patients who have osteochondromatosis. A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988, 70, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krooth RS, Maklin MT, Hilsbish TS. Diaphyseal aclasis (multiple exostoses) on Guam. Am J Hum Genet. 1961, 13, 340–347. [Google Scholar]

- Stocks P, Barrington A. Hereditary Disorders of Bone Development. Vol. 3. Treasury of Human Inheritance; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Terry Canale, S. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics; Mosby: St. Louis, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- D'Arienzo, A., L. Andreani, F. Sacchetti, S. Colangeli, and R. Capanna. Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: Current Insights. Orthopedic Research and Reviews 2019, 11, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Ambrosi R, Ragone V, Caldarini C, Serra N, Usuelli FG, Facchini RM. The impact of hereditary multiple exostoses on quality of life, satisfaction, global health status, and pain. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017, 137, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ropero S, Setien F, Espada J, Fraga MF, Herranz M, Asp J, Benassi MS, Franchi A, Patiño A, Ward LS, Bovee J, Cigudosa JC, Wim W, Esteller M. Epigenetic loss of the familial tumor-suppressor gene exostosin-1 (EXT1) disrupts heparan sulfate synthesis in cancer cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2004, 13, 2753–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajiao, K., X. Tomas, A. B. Larque, and P. Peris. Chondrosarcoma Transformation in Hereditary Multiple Exostosis: When to Suspect? International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2023, 26, 2095–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaishya, R., S. Swami, V. Vijay, and A. Vaish. Bilateral Total Hip Arthroplasty in a Young Man With Hereditary Multiple Exostoses. BMJ Case Reports 2015, 2015, bcr2014207853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter DE, Lonie L, Fraser M, Dobson-Stone C, Porter JR, Monaco AP, Simpson AH. Severity of disease and risk of malignant change in hereditary multiple exostoses. A genotype-phenotype study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004, 86, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sønderskov E, Rölfing JD, Baad-Hansen T, Møller-Madsen B. Hereditary multiple exostoses. Ugeskr Laeger. 2024, 186, V07240452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei L, Ngoh C, Porter DE. Chondrosarcoma transformation in hereditary multiple exostoses: A systematic review and clinical and cost-effectiveness of a proposed screening model. J Bone Oncol. 2018, 13, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rueda-de-Eusebio A, Gomez-Pena S, Moreno-Casado MJ, Marquina G, Arrazola J, Crespo-Rodríguez AM. Hereditary multiple exostoses: an educational review. Insights Imaging. 2025, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ha TH, Ha TMT, Nguyen Van M, Le TB, Le NTN, Nguyen Thanh T, Ngo DHA. Hereditary multiple exostoses: A case report and literature review. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022, 10, 2050313X221103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Handa T, Asanuma K, Yuasa H, Nakamura T, Hagi T, Uchida K, Sudo A. Osteosarcoma Arising from Iliac Bone Lesions of Hereditary Multiple Osteochondromas: A Case Report. Case Rep Oncol. 2024, 17, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gözdaşoğlu S, Uysal Z, Kürekçi AE, Akarsu S, Ertem M, Fitöz S, Ikincioğullari A, Cin S. Hereditary multiple exostoses and acute myeloid leukemia: an unusual association. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000, 17, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakane T, Goi K, Oshiro H, Kobayashi C, Sato H, Kubota T, Sugita K. Pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a boy with hereditary multiple exostoses caused by EXT1 deletion. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014, 31, 667–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comisi F, Fusco C, Mura R, Cerruto C, D'Agruma L, Carnazzo S, Castori M, Savasta S. Hereditary Multiple Osteochondromas and Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Possible Role for EXT1 and EXT2 in Hematopoietic Malignancies. Am J Med Genet A. 6405. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neben K, Werner M, Bernd L, Ewerbeck V, Delling G, Ho AD. A man with hereditary exostoses and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the bone. Ann Hematol. 2001, 80, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince SD, Krieger PA, Walter AW. Burkitt lymphoma in a pediatric patient with hereditary multiple exostoses. Jefferson Digital Commons, Pediatric and Adolescent Cancer and Blood Diseases Faculty Papers, 2013. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1149&context=pacbfp.

- Chudina AP, Akulenko LV, Prokopenko VD. Combination of multiple exostoses and lung cancer in 1 family. Vopr Onkol 1981, 27, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jia X, Liu Y, Wu C, Wu Z, Ji N, Huang M. Hereditary multiple exostoses complicated with lung cancer with cough as the first symptom: a case report. Transl Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 3040–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barbone F, Bovenzi M, Cavallieri F, Stanta G. Cigarette smoking and histologic type of lung cancer in men. Chest. 1997, 112, 1474–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pata G, Nascimbeni R, Di Lorenzo D, Gervasi M, Villanacci V, Salerni B. Hereditary multiple exostoses and juvenile colon carcinoma: A case with a common genetic background? J Surg Oncol. 2009, 100, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez Calas RA, González Millán T, Mohammed S, Azahares Leal G, Amadu M, Sadat Seidu A. Advanced colon cancer coexisting with multiple Osteochondromatosis in a child; coincidence or causality? - A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023, 108, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Decker RE, Wei WC. Thoracic cord compression from multiple hereditary exostoses associated with cerebellar astrocytoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1969, 30, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu Q, Xiao BO, Li LI, Feng LI. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor with hereditary multiple exostoses in an 18-year-old male: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2015, 10, 1561–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Remde H, Kaminsky E, Werner M, Quinkler M. A patient with novel mutations causing MEN1 and hereditary multiple osteochondroma. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2015, 2015, 14–0120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- I numeri del Cancro in Italia, AIOM, https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024_NDC-web.

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 203. 10.3322/caac.21830. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisci S, Guzzinati S, Dal Maso L, Sacerdote C, Buzzoni C, Gigli A; AIRTUM Working Group. An estimate of the number of people in Italy living after a childhood cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017, 140, 2444–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Non-skeletal malignancies reported in individuals with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses.

Table 1.

Non-skeletal malignancies reported in individuals with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses.

| System |

Pt |

Malignancy |

Age |

Sex |

Genetic Anomaly |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Hematopoietic |

1 |

AML |

8y |

F |

Not available |

| 2 |

Pre-B ALL |

14m |

M |

EXT1 deletion |

| 3 |

Pre-B ALL |

14y |

F |

EXT2 mutation |

| 4 |

High grade NHL |

53y |

M |

Not available |

| 5 |

BL (abdomen) |

10y |

M |

Not available |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Respiratory |

6 |

Lung SCC (uncertain correlation) |

56y |

M |

Not available |

| 7 |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

33y |

M |

Not available |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gastrointestinal |

8 |

Colon carcinoma |

31y |

M |

EXTL3 variant |

| 9 |

Colorectal carcinoma |

12y |

M |

Not available |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Nervous |

10 |

Cerebellar astrocytoma |

15y |

M |

Not available |

| 11 |

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor |

18y |

M |

Not available |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Endocrine |

12 |

Papillary thyroid carcinoma |

36y |

M |

No EXT1/EXT2 alterations |

| 13 |

MEN Type 1 |

47y |

M |

EXT1 and MEN1 mutations |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).