1. Introduction

To reduce the waste of natural resources and protect the environment, nations worldwide have implemented various energy- and water-conservation strategies. In addition to improving resource-use efficiency and developing alternative resources, minimizing unnecessary exploitation of natural resources is a key principle for sustainable development. In Taiwan, the average per capita availability of water resources is far below the global average, making the island one of the world’s water-scarce regions. Consequently, the conservation and efficient utilization of groundwater resources have become critical issues, and reducing unnecessary groundwater extraction plays an important role in sustainable water management.

Groundwater serves as an essential resource for domestic, industrial, and agricultural uses. However, during the construction of high-rise buildings, deep excavation is often required to establish stable foundations within the soil layer. In areas with abundant groundwater, such excavation commonly leads to construction difficulties, particularly where the groundwater table is high. In such cases, groundwater levels must be lowered to maintain a dry environment suitable for foundation work.

In Taiwan, when groundwater infiltration or accumulation occurs during excavation, dewatering operations are commonly implemented by installing large pumping wells around the site to discharge groundwater outside the construction zone. This process, which uses pumping systems to lower groundwater levels, is known as dewatering engineering. However, dewatering systems are temporary facilities rather than part of the building’s structural framework. Their environmental impact is often overlooked by contractors or developers, resulting in excessive groundwater discharge directly into surface drainage systems or even the sea. Over pumping may also cause soil void formation or subsidence at the construction site and nearby residential areas. Therefore, understanding groundwater behavior and developing intelligent control of pumping rates in high-rise construction dewatering systems are of critical importance.

According to the Taiwan Water Resources Agency’s Drought-Resistance and Water-Finding Program Report (April 21, 2021), approximately 38,000 tons of groundwater per day are discharged from construction-site dewatering operations. Thus, reducing groundwater extraction during construction is essential for groundwater conservation.

Traditionally, groundwater levels at construction sites in Taiwan have been monitored through manually measured observation wells using measuring rods and scheduled human labor, a small number of contractors employ automated sensors for continuous monitoring, but these systems require significant cost and maintenance. To address these limitations, this study proposes an artificial intelligence (AI)-based groundwater prediction model that integrates artificial neural networks (ANN) with fuzzy logic theory to simulate groundwater levels and optimize dewatering operations.

In current construction practices, dewatering operations generally follow regulatory requirements stipulating that groundwater levels must be maintained 1–2 meters below the excavation surface during construction to prevent soil instability or ground subsidence in adjacent areas. However, this long-term and imprecise pumping strategy often leads to excessive groundwater discharge and wastage. This study further investigates the incremental loading behavior associated with the completion of each building floor and applies the expert judgment method to establish fuzzy membership functions representing construction progress. Based on this, a smart, energy- and water-saving dewatering model is developed to reduce unnecessary groundwater extraction. By applying the concept of balancing buoyant forces from higher groundwater levels against the increasing structural loads of the building during construction, the proposed method enables the early reduction of pumping volumes—thereby mitigating excessive dewatering before project completion.

This study focuses on the impacts of dewatering works for high-rise building foundations in metropolitan areas of Taiwan on the complex subsurface environment. Under conditions of limited data and resources, an intelligent management model for groundwater dewatering at high-rise building sites is developed to achieve the goal of water conservation. The main contributions and innovative aspects of this study are summarized as follows:

‧First application of ANN to urban high-rise dewatering impact studies:

Based on the authors’ literature review and data analysis, no previous studies have applied artificial neural networks (ANN) to investigate the effects of dewatering on groundwater at high-rise building construction sites in urban areas. This study introduces, for the first time, a novel concept by applying ANN to simulate groundwater levels under the nonlinear and complex conditions of urban high-rise dewatering operations.

‧Integration of expert judgment and fuzzy membership for water-saving:

Previous studies rarely employed the expert judgment method to evaluate building behaviors during high-rise construction under uncertain conditions. In this study, an expert-opinion-based approach is proposed to construct fuzzy membership functions representing floor completion status. By leveraging the concept of balancing buoyant forces from preemptively elevated groundwater levels against the gravitational load of completed floors, unnecessary pumping during construction is significantly reduced. This approach constitutes a new intelligent water-saving dewatering model for high-rise building foundations.

‧Combining ANN with MODFLOW simulations to overcome data scarcity:

In Taiwan, complete environmental monitoring data for high-rise dewatering operations are scarce. However, ANN modeling requires substantial hydrogeological data for training. This study addresses the data limitation by integrating MODFLOW numerical simulations to generate training datasets for ANN-based groundwater modeling. A limited set of actual monitoring data is then used to validate the combined ANN–MODFLOW approach. This method effectively mitigates the severe data scarcity issue in Taiwan and provides a practical and applicable framework for implementing AI-based groundwater management in urban high-rise construction dewatering operations.

2. Literature Review

This study aims to establish an intelligent water-saving model for dewatering in high-rise building sites in urban areas. The model predicts groundwater levels using an artificial neural network (ANN) and incorporates expert opinion surveys to construct fuzzy membership functions representing floor completion. By integrating ANN and fuzzy theory with expert knowledge, a fuzzy dewatering and water-saving model for urban high-rise buildings is developed. The following is a review of the relevant literature on these theories and their applications.

The primary function of ANNs is to enable machines to perform computations resembling the neural network structures of biological brains (including humans). The theory of artificial neural networks was first proposed in a pioneering scientific paper by two American mathematicians and logicians, Walter Pitts and Warren Sturgis McCulloch, titled A Logical Calculus of Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity (1943), which introduced the first mathematical model of a neural network [

1].

Although modern ANNs differ from traditional statistics in certain ways, they share some similarities. For instance, in statistical regression analysis, causal relationships are often established by fitting equations to observed behaviors when a reasonable physical model is not available. Similarly, ANNs derive relationships between input and output variables based on empirical data without explicitly considering the detailed underlying physical mechanisms. While regression analysis guarantees a good approximation of a continuous function, ANN theory ensures an accurate representation of the function (Emery Coppola Jr et al., 2003 [

2]).

In the field of engineering applications, many researchers have already achieved significant progress in applying artificial neural networks (ANNs) to subsurface hydrogeological environments. Examples include predictions of nonlinear problems such as precipitation, sediment load, river flow, chlorophyll-a levels, and regional index floods (Yicheng Gong et al., 2016[

3]). Therefore, ANNs can also be applied to predict nonlinear and complex groundwater levels. This paper provides a literature review of current research studies on the application of ANNs specifically to groundwater.

Sanghoon Lee et al. (2019) [

4] demonstrated that artificial neural networks (ANNs) can accurately predict and simulate the impacts of human development activities on groundwater levels, showing that ANNs are not limited to forecasting natural environmental changes. Zhenfang He et al. [

5] combined traditional ANN with wavelet analysis and fractal theory to form wavelet artificial neural networks (WANN). This approach captures variations under complex and irregular conditions to predict groundwater depth (GWD).

Huanhuan Li et al. (2019) [

6] optimized the original ANN gradient descent method by using the artificial bee colony (ABC) optimization algorithm to determine network weights and biases, addressing issues of local minima and over fitting to provide an effective tool for groundwater management.

Shishir Gaur et al. (2018) [

7] developed an ANN integrated with particle swarm optimization (PSO) for optimizing groundwater pumping wells and piping networks in the Dore River catchment in France , it emphasized that ANN can providing accurate groundwater level predictions.

Sasmita Sahoo et al. (2013) [

8] evaluated the predictive performance of multiple linear regression (MLR) versus ANN for groundwater level forecasting, the results indicated that ANN outperformed MLR, highlighting ANN’s superior capability in predicting nonlinear and complex groundwater level behavior.

Regarding research on artificial neural networks (ANNs), some studies have focused not only on comparing traditional versus modified ANN methods but also on investigating the intrinsic characteristics of ANNs. Xian Li et al. (2012) [

9] conducted a sensitivity analysis to identify the key parameters that determine the output of an ANN.

Other studies have focused on consolidating and comparing the strengths and weaknesses of various single ANN and integrating their advantages to develop new groundwater ANN models (Mohammad Ehterama et al., 2022) [

10]. Additionally, some researchers have analyzed groundwater simulations across different geological strata, demonstrating that ANNs can achieve highly accurate predictions of groundwater levels. (Emery Coppola Jr et al., 2003) [

2].

From the above literature review on artificial neural networks (ANNs), it is evident that research on ANN-based groundwater level prediction models is highly diverse. However, no studies have specifically addressed the impact of dewatering operations at high-rise building construction sites in urban areas on groundwater levels. Currently, monitoring the effects of construction dewatering in Taiwan requires substantial manpower and resources. In view of this, the present study employs ANNs to develop a groundwater level prediction model, with the primary objective of providing an alternative reference tool for situations where sufficient human and material resources are unavailable. This model aims to offer building contractors or project owners a scientific basis for managing construction activities.

Regarding the literature on the application of fuzzy theory combined with expert opinion, fuzzy theory was first proposed in 1965 by Professor L.A. Zadeh at the University of California, Berkeley. In his paper Fuzzy Sets published in the journal Information and Control, he developed this theory to address the ubiquitous vagueness present in the real world, fuzzy theory uses a mathematical model to describe semantic, imprecise information, enabling reasoning without requiring precise or complex calculations.

Regarding expert opinion methods, in many practical problems, data are often insufficient or entirely lacking, expert opinion surveys provide a suitable means to construct scientifically grounded models. Combining fuzzy theory’s strength in expressing human subjectivity with expert opinion surveys offers an ideal methodological approach for handling and interpreting expert-derived information.

Regarding the application of fuzzy theory combined with expert opinion in civil engineering, the relevant research findings are reviewed below based on their actual applications.

Mehrbakhsh Nilashi et al. (2015) [

11] employed the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) based on expert opinions for group decision-making, and applied a fuzzy inference system to conduct the final performance assessment of green buildings. Manuel Carpio et al. (2021)[

12] focused on preventive maintenance of heritage buildings, using fuzzy logic to handle the uncertainty and vagueness in expert assessments, converting input variables into fuzzy sets, and applying fuzzy inference to calculate output variables. In all above these studies, the authors used a similar technique: expressing the relative importance of each evaluation criterion as fuzzy numbers based on expert judgments and inputting these into a fuzzy inference system (FIS) for solution via fuzzy reasoning.

Additionally, some researchers have focused on theoretical analysis. Aleksandras Krylovas et al. (2015)[

13] extended traditional fuzzy sets to the Intuitionistic Fuzzy Set (IFS) framework and proposed an expert evaluation aggregation method based on Triangular Intuitionistic Fuzzy Numbers (TIFN), this approach reduces the probability of ranking errors compared to conventional methods; Yih-Tzoo Chen et al. (2024)[

14] aimed to deciding on matters related to bidding, modified traditional fuzzy set, they adopted the Spherical Fuzzy Set (SFS) to provide a more complete mathematical structure, capturing expert judgment logic under uncertain conditions.

Moreover, some studies have integrated expert opinions and fuzzy theory with other relevant methods to solve complex problems. Aminah Robinson Fayek (2019) [

15], the author incorporated machine learning techniques into the fuzzy expert data, combining fuzzy logic with machine learning to create a “fuzzy hybrid” approach and was validated through practical construction management case studies, demonstrating its advantages.

Konstantinos A. Chrysafis et al. (2012) [

16]. They combined fuzzy set theory with stochastic processes to develop a Fuzzy Statistical Model (FSM) to manage the uncertainty in expert estimates of construction activity durations, case studies showed that FSM achieved higher prediction accuracy for activity durations than traditional techniques.

Some researchers have focused on modifying traditional methods to address their limitations. Debashree Guha et al. (2010) [

17] represented traditional expert opinion fuzzy information using fuzzy numbers and further incorporated a “confidence degree” evaluation technique. This process emphasizes the views of “trustworthy experts” within the expert group, producing results that more accurately reflect real-world conditions.

Shahab Hosseini et al. (2024)[

18] aimed to enhance the model’s tolerance to uncertainty in expert knowledge, they applied Z-number theory, which can simultaneously handle both “semantic fuzziness” and “expert confidence,” and integrated it with a Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) to form the Z-FIS method, using circular foundations of building sites as a case study, the results demonstrated that Z-FIS outperformed traditional FIS of bearing capacity predictions.

Some researchers have addressed practical problems by integrating expert systems with fuzzy theory. Although these approaches do not directly apply the expert opinion method with fuzzy theory, expert experience is still required to construct the system. M. E. Emiroglu et al. (2002) [

19] applied this approach to dam type selection for alluvial foundations.

Additionally, fuzzy theory has been integrated into expert-based Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to form Fuzzy AHP (FAHP), allowing for the handling of uncertainty inherent in expert judgments. Mehrdad Sadeghi et al. (2022) [

20] employed this approach to determine the weight distribution of various green building evaluation criteria across different climate zones. Similarly, Pemika Hirankittiwong et al. (2025)[

21] used Fuzzy AHP(FAHP) to evaluate multiple criteria for designing smart windows in green buildings, identifying priority technologies for implementation.

From the literature review above, it can be seen that the combination of fuzzy theory and expert opinion has been applied in an almost unlimited variety of civil engineering cases, this demonstrates that integrating these two theories and techniques serves as a fundamental approach for establishing an initial scientific model, particularly in situations with insufficient data or when addressing uncertainty.

Based on the literature review presented above, although numerous studies have applied artificial neural networks (ANN) to investigate groundwater, to the best of the author’s knowledge, research on the impact of dewatering operations at high-rise building construction sites on the groundwater levels beneath building foundations remains limited. To date, no study has applied ANN to simulate dewatering processes at high-rise building construction sites in metropolitan areas. This study is the first to establish an ANN-based model for simulating groundwater levels beneath high-rise building foundations, addressing the complex and highly nonlinear hydrogeological conditions typically encountered at urban construction sites.

Moreover, no prior research has applied fuzzy mathematics combined with expert judgment to develop a water-saving dewatering strategy for high-rise building construction sites. This study is also the first to employ expert judgment in combination with fuzzy theory to determine the incremental floor weight pattern during construction. By establishing floor completion membership functions, the study incorporates the concept of net force equilibrium, where the gravitational increase due to floor construction is counterbalanced by the buoyant effect caused by the rise in groundwater resulting from reduced dewatering, this approach achieving a water-saving objective for foundation dewatering operations.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Framework and Methodological Basis

As described in the introduction, dewatering operations at high-rise building construction sites produce complex physical effects on groundwater. In metropolitan Taiwan, the construction period of high-rise buildings generally lasts 2–3 years. During this period, the rise and fall of groundwater levels after dewatering involve complex hydrogeological conditions, which change over time. Geological factors include soil surface infiltration, soil porosity, hydraulic conductivity, and aquifer storage capacity, while hydrological factors include solar radiation, precipitation, evapotranspiration, and the influence of nearby rivers. Traditionally, groundwater levels have been described using time-series approaches, but such methods often rely solely on historical groundwater data and time to establish autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models. These approaches are overly simplified and are limited in predicting groundwater levels in highly nonlinear and complex hydrogeological environments [

22].

Because time-series approaches are too simplified for highly nonlinear groundwater systems, several numerical simulation models have been developed to understand physical processes and mechanisms, including MODFLOW, FEFLOW, and HydroGeoSphere (HGS). However, these physics-based numerical models require extensive datasets, explicit physical parameters, and mathematical formulations to accurately represent the system. Acquiring such data is costly and time-consuming, and is particularly challenging when sufficient hydrological, geological, and geotechnical information is unavailable [

4].

Given the limitations of these traditional numerical methods, artificial neural networks (ANN) offer an alternative for predicting dynamic and highly nonlinear systems. ANNs are multi-layered networks inspired by human or animal brain structures, capable of representing complex nonlinear relationships between inputs and outputs that cannot be fully captured by physical models. For specific locations, ANN can effectively predict groundwater conditions influenced by irregular and nonlinear factors, particularly when hydrological and geological data are insufficient, the ANN provides a robust tool for modeling complex and uncertain groundwater environments, offering a new and effective approach for simulating nonlinear groundwater dynamics.

However, ANN training requires large amounts of data, which is currently difficult to obtain for dewatering operations at construction sites in Taiwan. Long-term variations in hydrogeological conditions during high-rise construction, make it nearly impossible to acquire sufficient datasets for ANN training. To address this challenge, this study uses a new concept based on the limited existing actual construction site hydrological and geomorphological data and combines it with theories based on clear physical theories and numerical calculation methods, these theories can still be confidently used in the design of MODFLOW operations, using this indirect method to obtain a large amount of hydrological and geomorphological data will help to establish a complete database for research objects that lack complete hydrological and geomorphological measured data. This database can also be applied to machine learning technology. In addition, if the groundwater level elevation obtained from these theories can be combined with actual data for comparison and verification, it can provide a highly effective alternative method for predicting groundwater levels in construction sites. The establishment of this simulation model can provide pioneering research on the application of neural networks in dewatering projects at construction sites in Taiwan.

The limited measured datasets at the study site include head test data, pumping rate data from dewatering wells, and groundwater level measurements, one monitoring well experienced data loss, and the remaining wells have insufficient data to train, test, and validate an ANN model independently. Therefore, secondary datasets from governmental agencies, universities, and research institutions were collected, constant-head test data at the study site were used to calibrate the MODFLOW model, enabling the generation of sufficient simulated data to train and validate the ANN model. Finally, the ANN predictions were compared with available field measurements again to assess the accuracy and reliability of the ANN-based groundwater simulation.

In addition, fuzzy theory often plays a key role in handling uncertain factors; its main advantage is that it does not require detailed data, to construct models for uncertainty. In particular, for uncertainty analysis in situations lacking historical data or when analyzing knowledge accumulated from human experience, fuzzy theory provides a robust tool for quantifying uncertainty.

Regarding the application of expert opinion methods in civil engineering, the discipline of civil engineering contains numerous procedures developed from theory, actual practice and ‘rules of thumb’(M. E. Emiroglu et al., 2002)[

19]. So according to this rule of thumb, In high-rise building construction, the manner in which floor weight increases during the construction process is not well documented statistically. Therefore, only experts with professional knowledge and practical experience can accurately assess how the weight of each floor increases during construction.

In this study, experts were directly consulted to determine the typical patterns of weight addition during construction. The resulting membership function quantifies the relationship between the weight added by completed floors and the net buoyant effect on groundwater levels caused by reduced dewatering, thereby achieving net force equilibrium. This approach allows for reduced groundwater extraction during construction, aligning with water-saving objectives.

3.2. Methodology Description

This study involves several theoretical frameworks and techniques, including artificial neural networks (ANNs), fuzzy theory, expert opinion methods, and finite difference methods. A brief description of each is provided below.

3.2.1. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

The concept of artificial intelligence (AI) first emerged in the 1950s. Its widely accepted definition today is “the capability of machines to mimic human behavior.” AI becomes particularly noteworthy when machines not only emulate human abilities but can even surpass human performance—for example, in terms of large memory capacity or high computational speed. Essentially, based on the current development and achievements in AI, AI can be interpreted as machine learning, which trains machines to acquire desired human-like behaviors. Machine learning involves providing input data and the expected outputs, allowing the machine to autonomously learn the mapping between them, and ultimately enabling the machine (computer) to generate a learning algorithm on its own.

Since machine learning (including deep learning) is currently the dominant approach in AI development, one key method to endow machines with learning capabilities is to imitate the computational patterns of biological neural networks, particularly those in the human brain, this approach constructs models that simulate the operation of biological neural networks and is referred to as artificial neural networks (ANNs), ANNs are a nonlinear statistical modeling tool, typically optimized through a mathematically-based learning method.

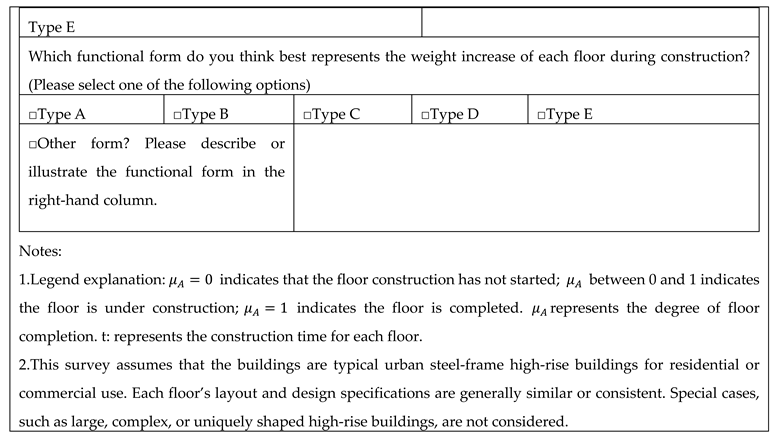

(a) Human Neural Networks

The development of artificial neural network models originates from our understanding of the human brain's neural system. The human brain is composed of tens of billions of nerve cells (neurons), each connected to thousands of other neurons through synapses, forming a vast and complex neural network. Each neuron extends numerous thin projections: axons, which are long projections responsible for transmitting signals outward, and dendrites, which are shorter projections responsible for receiving input signals into the cell body. The terminal of an axon forms a specialized structure that connects to a target cell, known as a synapse, which stores a large number of neurotransmitters responsible for signal transmission. Once released, these neurotransmitters transmit information to the next neuron. A conceptual diagram of a biological neuron is shown in

Figure 1.

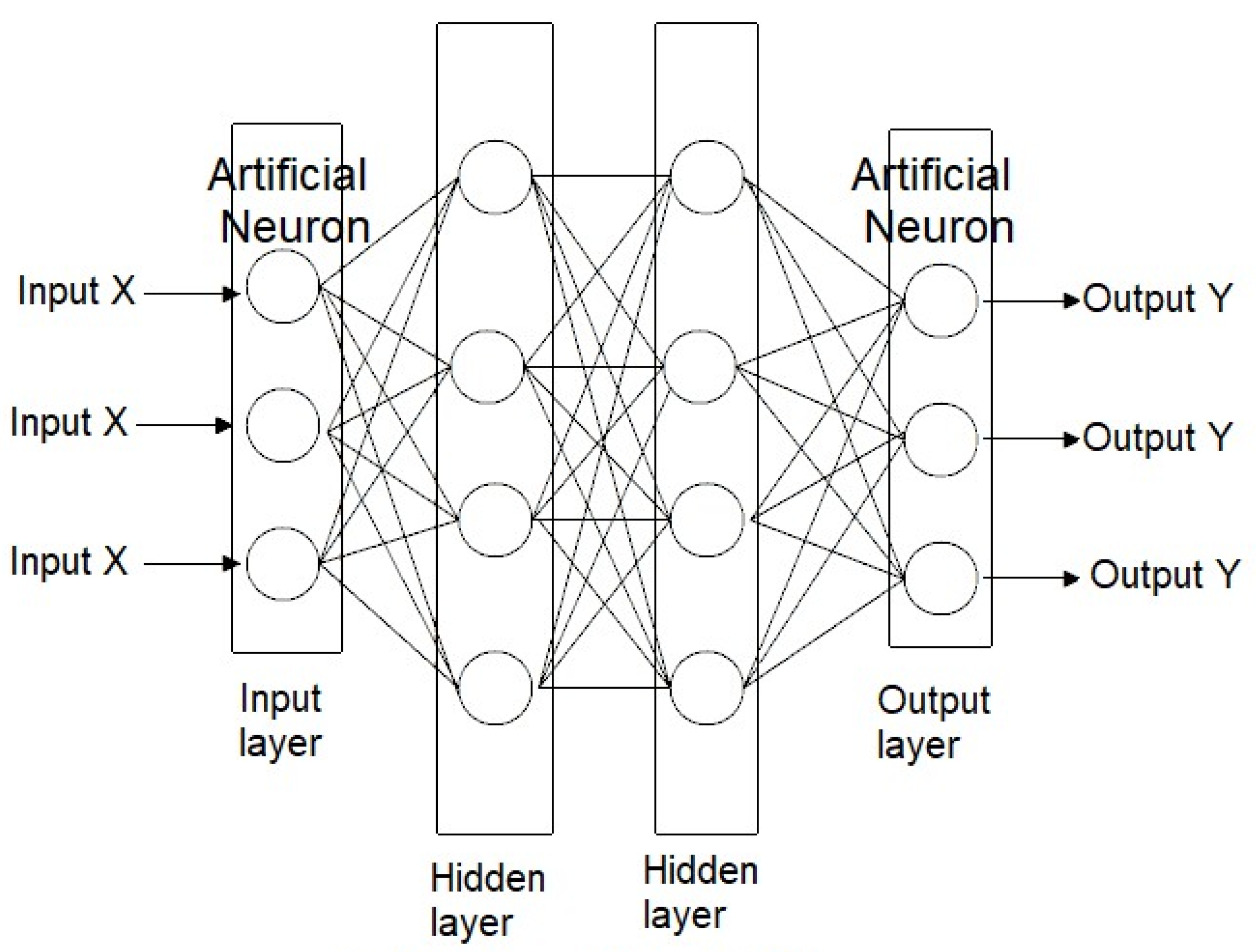

(b) Artificial Neural Networks

The theoretical foundation of artificial neural networks (ANNs) was pioneered by two American mathematicians and logicians, Walter Pitts and Warren Sturgis McCulloch, who co-authored a groundbreaking paper titled “A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity” in 1943 [

1]. This work first proposed a mathematical model of a neural network. Although the unit model is a simplified and formalized version of a neuron, it remains a fundamental reference in the field of neural networks to this day.

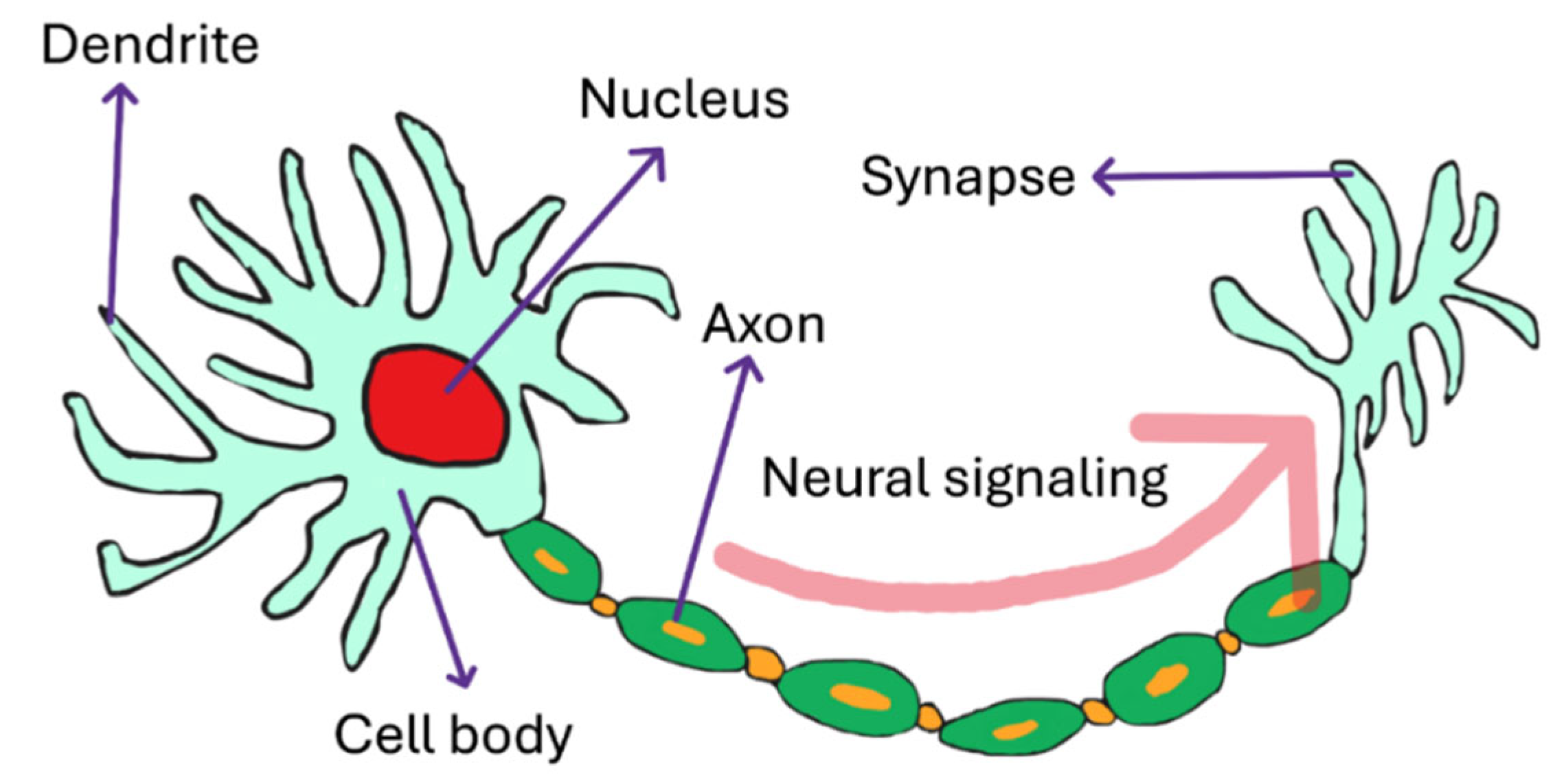

An artificial neuron (also called a perceptron) is designed to mimic the function of biological neurons as a unit for information processing.

Figure 2 illustrates the conceptual model of a single artificial neuron, showing the basic relationships and components, including inputs (X), weights (W), activation function (F(·)), and output (Y). These components together form the essential computational structure of an artificial neuron.

The foregoing describes the operation of a single artificial neuron, analogous to a biological neuron. However, to enable an artificial neural system to achieve better judgment and more complex predictive capabilities, it is necessary to increase the number of neurons. Multiple neurons can form a neural layer, and multiple layers together constitute an artificial neural network (ANN).

Figure 3 illustrates a typical architecture of such a neural network.

The first layer of neurons in the network is called the input layer, whose neurons primarily receive incoming signals. Once the input layer receives these signals, it transmits them to the subsequent hidden layers for computation. A hidden layer may consist of one or multiple layers of computational neurons, which process the information and pass the results to the final output layer, where the network produces its computed output.

(i) Operating Principle of Neural Systems

‧Operation of a Single Artificial Neuron

As shown in

Figure 2, the central circular structure represents the neuron. The left side of the neuron receives multiple input values (commonly denoted as x), similar to the dendrites of a biological neuron. After processing, the neuron transmits a single output value (commonly denoted as y) from its right side, analogous to the axon of a biological neuron.

The internal signal processing of the neuron is a mathematical operation. Each input value entering the neuron is multiplied by a corresponding weight (w), representing the relative importance of the input signal to the neuron. The products of all input values and their weights are summed and then added to a bias (b), a constant used to adjust the output of the neuron. This produces the value u, expressed as:

In Equation (1), a positive weight indicates a positive relationship between the input and output, while a negative weight represents a negative relationship. The bias b enhances the input signal when positive and suppresses it when negative.

The calculated u is then passed through the neuron’s activation function f (⋅), which introduces nonlinearity and endows the neuron with learning capabilities. The output of the activation function becomes the neuron’s final output y, which serves as the input for subsequent neurons:

‧Operation of a Multilayer Neural Network

For a neural network consisting of multiple neurons arranged in layers, the computation can be represented conveniently using vectors and matrices. The output of a multilayer neural network can be expressed as:

In Equation (3), the vector

can be expressed in matrix-vector form as:

Core Operator of Neural Networks: Activation Function

The input signals to an artificial neuron must be mapped to the output through a mapping function, known as the activation function. The ability of a neural network to discover the nonlinear complex relationships between input X and output Y largely depends on the computation of the activation function. In other words, the primary role of the activation function is to handle the nonlinear complex phenomena between inputs and outputs, enabling the neural network to clearly capture the contextual relationships and thereby providing the network with learning capabilities for nonlinear systems.

- Commonly used activation functions f (⋅) include:

-Step Function

-Sigmoid Function

-Hyperbolic Tangent Function (tanh)

-Rectified Linear Unit Function (ReLU)

-Leaky Rectified Linear Unit Function (Leaky ReLU)

-Softmax Function

-Identity Function

The choice of activation function should be appropriately applied depending on the specific requirements of the task.

‧Neural Network Training

The training of an artificial neural network (ANN) primarily aims to minimize the error of the loss function to achieve the predefined target value. In practice, the training process involves iteratively adjusting the weights and biases of all neurons. When the total error across all neurons reaches a minimum, the network is considered to have achieved optimal weights and biases.

Over time, various training algorithms have been developed for ANNs, each with its own advantages and limitations. Moreover, the performance of a particular training method may vary depending on the practical application context. In this study, five widely cited training methods are applied to construct the simulation model, and their characteristics are briefly described as follows:

Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) Training: Combines the advantages of the Newton method and gradient descent. Suitable for small- to medium-sized networks, with fast convergence.

Bayesian Regularization (BR) Training: Regularizes and normalizes all input parameters during training. Its main feature is to prevent overfitting.

Scaled Conjugate Gradient (SCG): An improved conjugate gradient algorithm that does not require line searches, making it suitable for large-scale networks.

Conjugate Gradient with Fletcher–Reeves Updates (CGF): A traditional conjugate gradient update method, characterized by low memory requirements.

BFGS Quasi-Newton Training: Proposed by Broyden, Fletcher, Goldfarb, and Shanno as a modification of the Newton method. This second-order derivative approximation optimization converges faster than simple gradient descent and is suitable for small- to medium-sized networks.

3.2.2. Fuzzy Theory and Expert Opinion Methods

(a) Fuzzy Theory and Fuzzy Membership Function

Fuzzy theory was first proposed in 1965 by Professor L. A. Zadeh at the University of California, Berkeley. In his seminal paper published in Information and Control, titled Fuzzy Sets, Zadeh introduced a mathematical framework to address the pervasive fuzziness in real-world phenomena. The theory provides a method to describe semantic ambiguity using a mathematical model.

Fuzzy theory is specifically designed to handle situations where the human brain processes imprecise or incomplete information. It allows for correct judgment without requiring complex or precise calculations, which is the key feature of the theory. The distinction between a fuzzy set and a classical binary set (crisp set, with elements 0 or 1, where 1 represents “belongs” and 0 represents “does not belong”) lies in how membership is defined. In a fuzzy set, the degree to which an element belongs to a set X is expressed by a membership function , which takes values in the interval [0, 1], rather than being limited to only 0 or 1.

Formally, let X denote the universe of discourse, i.e., the complete set of all objects under consideration, and let A be a fuzzy subset of X, representing a finite set within the domain. The fuzzy set A can be expressed as:

where

is the membership degree of element x in A. A membership degree of 1 indicates that the fuzzy prediction fully corresponds to the target, whereas a degree of 0 indicates that the fuzzy prediction does not belong to the target set.

(b)Expert Opinion Methods

The expert opinion method is essentially an approach that collects and integrates information based on the knowledge and experience of experts. It is widely applied across various fields. Commonly used expert opinion methods include the following categories:

(i)Individual Judgment Method(ii)Expert Panel Method(iii)Questionnaire Survey (Expert Survey)(iv)Delphi Method(v)Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)Although these five expert opinion survey methods can be used individually, in practice, two or more methods are often combined to increase flexibility. In this study, the questionnaire survey method is used in conjunction with the individual judgment method for expert opinion collection.

(c) Calculation of Static Equilibrium for Floor Completion Fuzzy Membership Function

In this study, the floor completion fuzzy membership function is used to calculate the static equilibrium between the weight added by completed floors and the buoyancy generated by the rise in groundwater level. The increase in groundwater level is achieved by reducing the pumping volume.

For each floor, the floor weight is known from the high-rise building project budget and acts as a downward gravitational force. When the groundwater level rises by , the resulting buoyant force can be expressed as the product of the foundation area , the height increase , and the soil water content m, because only the water within the soil contributes to buoyancy while other soil components do not.

The static force equilibrium can therefore be expressed as:

where:

is the floor completion fuzzy membership function, with t representing construction time. A value of indicates that the floor has not been constructed, while indicates that the floor is completed. is a function of the pumping volume Q and pumping duration t, obtained from ANN-based simulation data.

Since the rise in groundwater level is achieved by reducing the dewatering volume in advance, this approach effectively prevents unnecessary groundwater extraction, contributing to water-saving measures at the construction site.

3.3. Theoretical Basis and Calibration of the MODFLOW Model

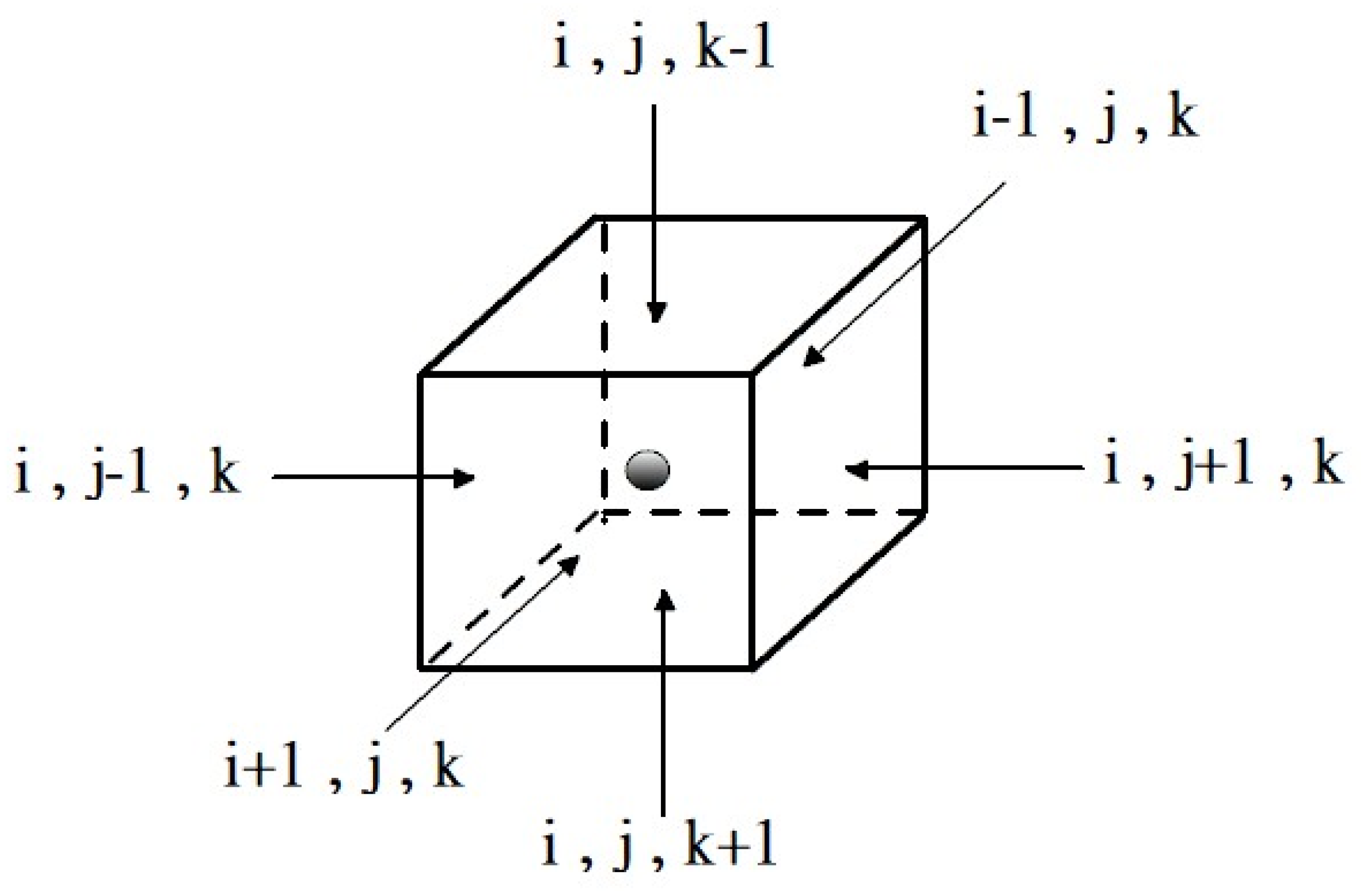

The MODFLOW groundwater flow model, officially named Modular Groundwater Flow Model, was developed by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). MODFLOW is an essential numerical simulation program in GMS (Groundwater Modeling System). The model is fundamentally based on the principle of mass conservation, which is applied to develop the continuity equation and subsequently the finite-difference form (FDM) of the groundwater flow equation to obtain approximate numerical solutions.

Before simulation, the study area must be discretized into grid cells, each assumed to have homogeneous properties. The groundwater flow within porous media is governed by the three-dimensional groundwater flow equation, which is a partial differential equation (PDE). MODFLOW solves this PDE using the Block Centered Finite Difference Approach, in which grid nodes are located at the block centers. Flow rates through the six faces of each grid cell are calculated, and second-order finite differences are used to approximate the governing equations. Following the law of mass conservation, the three-dimensional flow of groundwater through saturated porous media with constant density can be expressed by the following PDE for a unit control volume in a saturated aquifer:

Where:

are the hydraulic conductivity coefficients in the x, y, and z directions (L/T), h is the hydraulic head (L), W is the volumetric flux per unit volume (1/T), is the specific storage coefficient (1/L), t is time (T).

In groundwater flow modeling, this partial differential equation (PDE) is generally approximated using the finite difference method. The simulation domain is discretized into block-shaped grid cells, which are arranged by:

Rows (), with spacing between each row,

Columns (), with spacing between each column,

Layers (), with spacing between each layer.

Assuming a constant groundwater density, for a given grid cell (i, j, k), the water exchange between the cell and its six neighboring aquifer cells [ (i-1, j, k), (i+1, j, k), (i, j-1, k), (i, j+1, k), (i, j, k-1), (i, j, k+1) ] must be considered. A schematic of the block-centered finite difference method is shown in

Figure 4.

The MODFLOW model can simulate various types of aquifers, including unconfined, confined, and semi-confined aquifers, and can also be classified based on geological characteristics as homogeneous or heterogeneous, and isotropic or anisotropic aquifers.

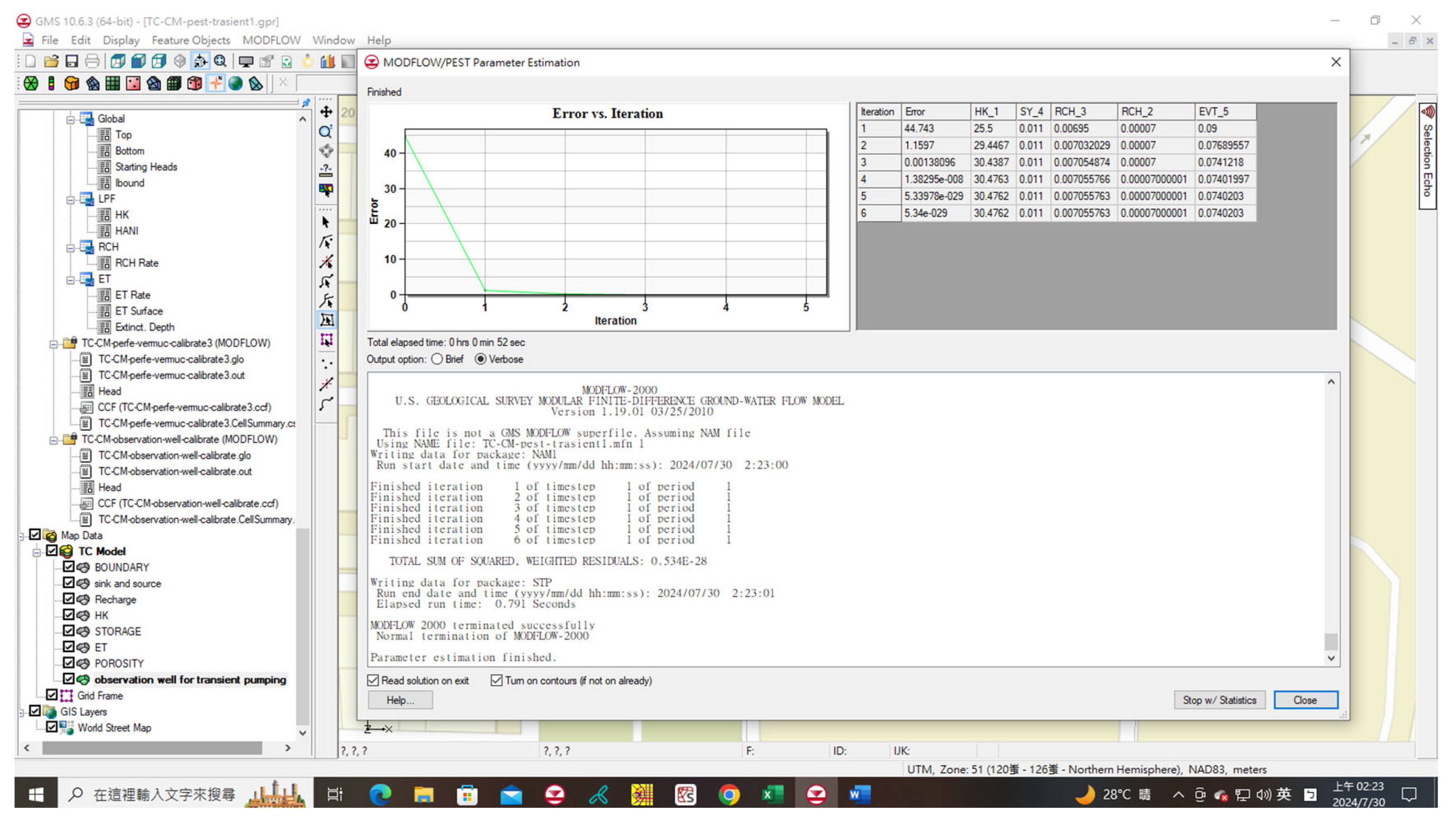

In MODFLOW, PEST (Parameter ESTimation) is a model-independent, nonlinear parameter estimation tool used for model calibration (inverse modeling) and data interpretation. PEST repeatedly runs the model while adjusting parameters to match simulated outputs with observed data.

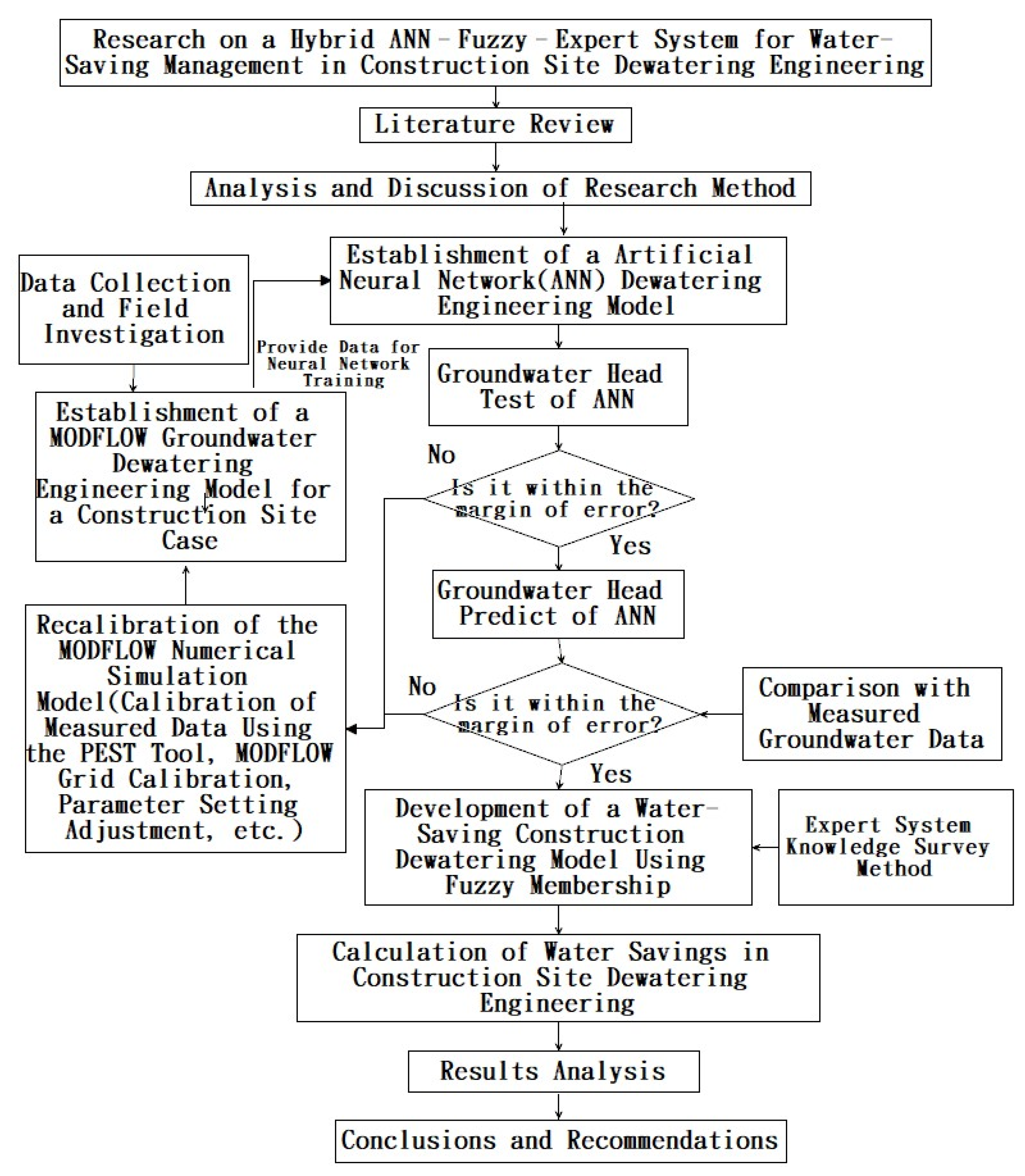

3.4. Research Workflow and Implementation Steps

The workflow and implementation steps of this study are summarized as follows:

1. Literature Review

2. Exploration of Research Methods

3. Establishment of a Water-Saving Dewatering Model for Construction Sites

4. Case Study

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The detailed flow chart of this study is shown in

Figure 5.

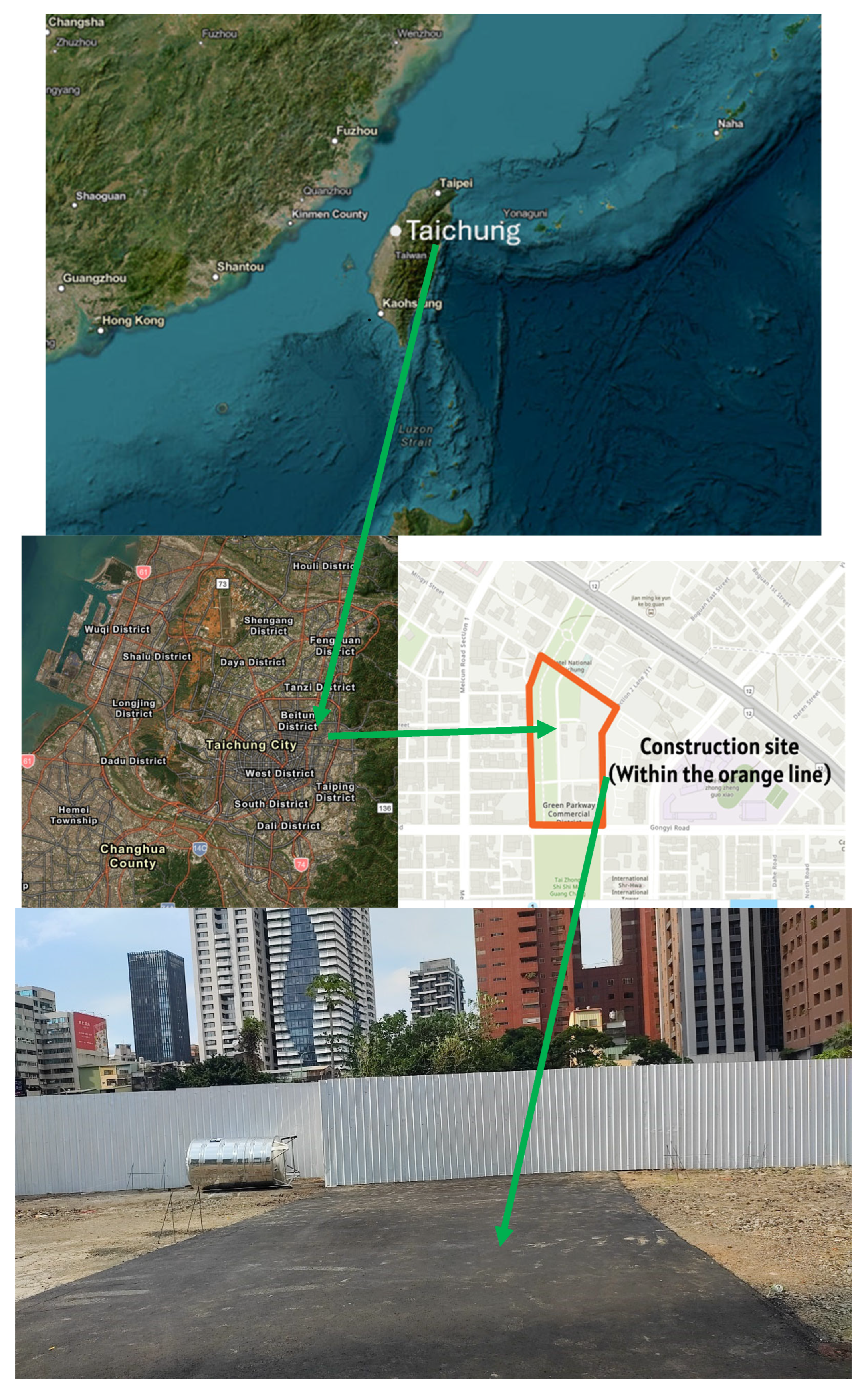

3.5. Case Study

To evaluate the effectiveness of an intelligent water-saving dewatering model for high-rise building construction sites in urban areas, this study conducted modeling and assessment at an actual construction site in Taichung City, Taiwan (

Figure 6). The site is a steel-structured high-rise building with a total area of approximately 10,500 m². According to pre-construction groundwater level monitoring data in June 2019, the surrounding groundwater level was approximately 6 m below ground level (GL ~ -6 m). The building design comprises 5 basement floors and 21 above-ground floors, and dewatering operations commenced simultaneously with the foundation excavation in 2019.

The site is equipped with 13 pumping wells around the perimeter (also used as monitoring wells) and one central monitoring well to track water levels. During the construction period, it was planned that the 13 perimeter wells would operate for 500 days. However, continuous monitoring data from some wells were missing or incomplete, and the limited number of measurements could not provide sufficient data for effective ANN model training and testing.

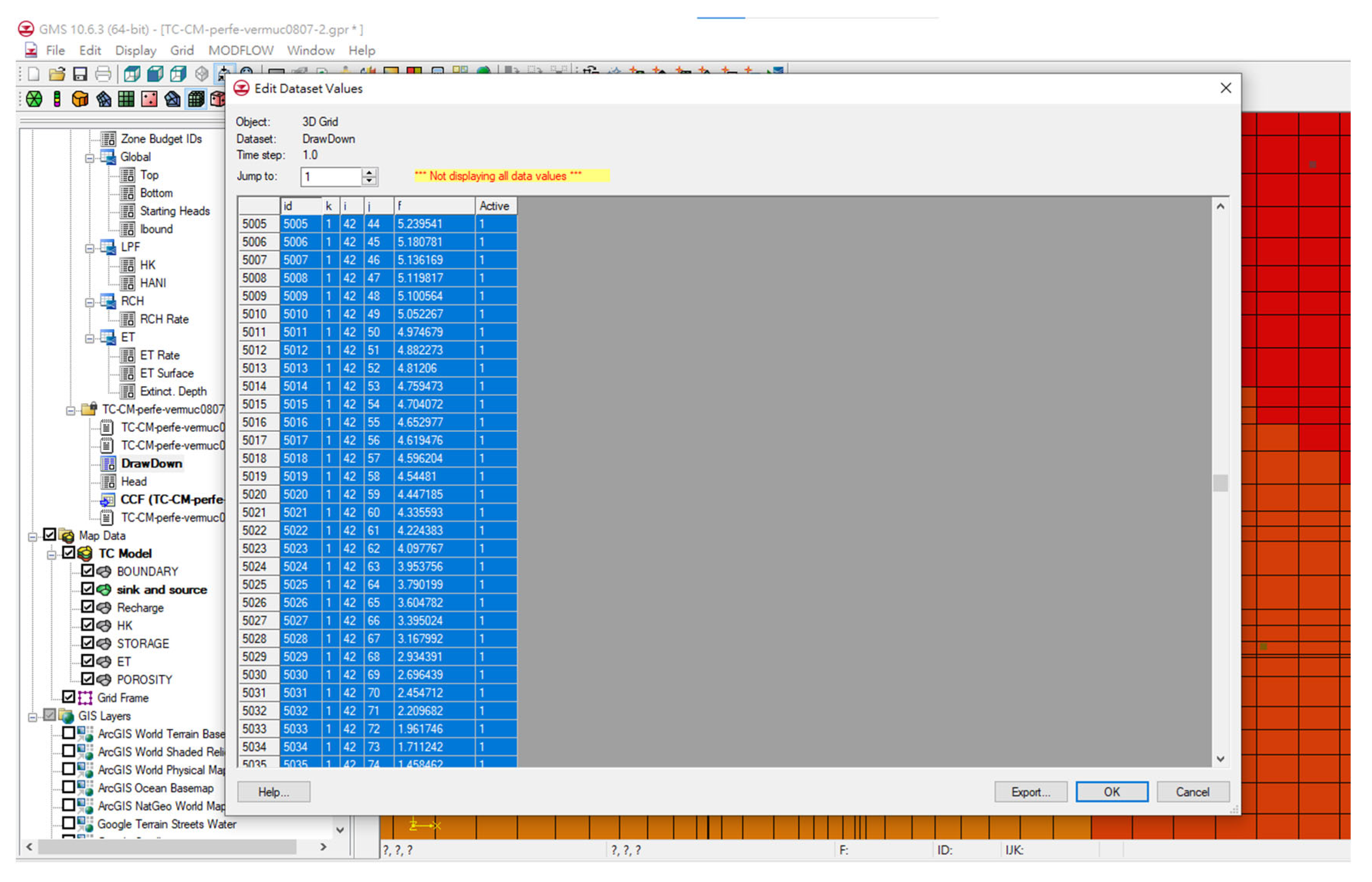

To overcome this, a MODFLOW groundwater simulation model for the construction site was developed using the Groundwater Modeling System (GMS). The model incorporated observed hydrogeological and geotechnical monitoring data as well as secondary data to establish a representative groundwater dewatering system for the Taichung steel high-rise construction site. The MODFLOW model was calibrated using actual constant-head testing data from the site to ensure accuracy.

Once the MODFLOW model was established, it was used to generate large datasets for training and testing the ANN model of the site’s groundwater dewatering system. The ANN predictions were then compared with the limited actual measured data to validate their accuracy. Finally, a smart water-saving dewatering model for the high-rise construction site was developed to optimize groundwater extraction, quantifying the potential reduction in water resource wastage achievable through intelligent dewatering management during the construction process.

3.6. Model Application and Parameter Setting

3.6.1. Construction of the Artificial Neural Network (Programming Language: MATLAB)

The artificial neural network (ANN) in this study was implemented using the MATLAB programming language. MATLAB, an abbreviation of Matrix Laboratory, is a high-level programming language specifically designed for numerical computation, matrix operations, engineering, and scientific applications.

A key feature of MATLAB is its matrix-centric computational framework, which allows all data types—including scalars, vectors, images, and other datasets—to be naturally represented and processed as matrices. MATLAB is equipped with an extensive mathematical function library, capable of addressing problems in linear algebra, statistics, signal processing, control systems, and optimization.

Furthermore, MATLAB provides specialized toolboxes that extend its capabilities to various professional domains, such as machine learning, image processing, and financial engineering. The MATLAB programming environment is not only graphical and user-friendly but also highly versatile, making it suitable for the development and implementation of complex ANN models.

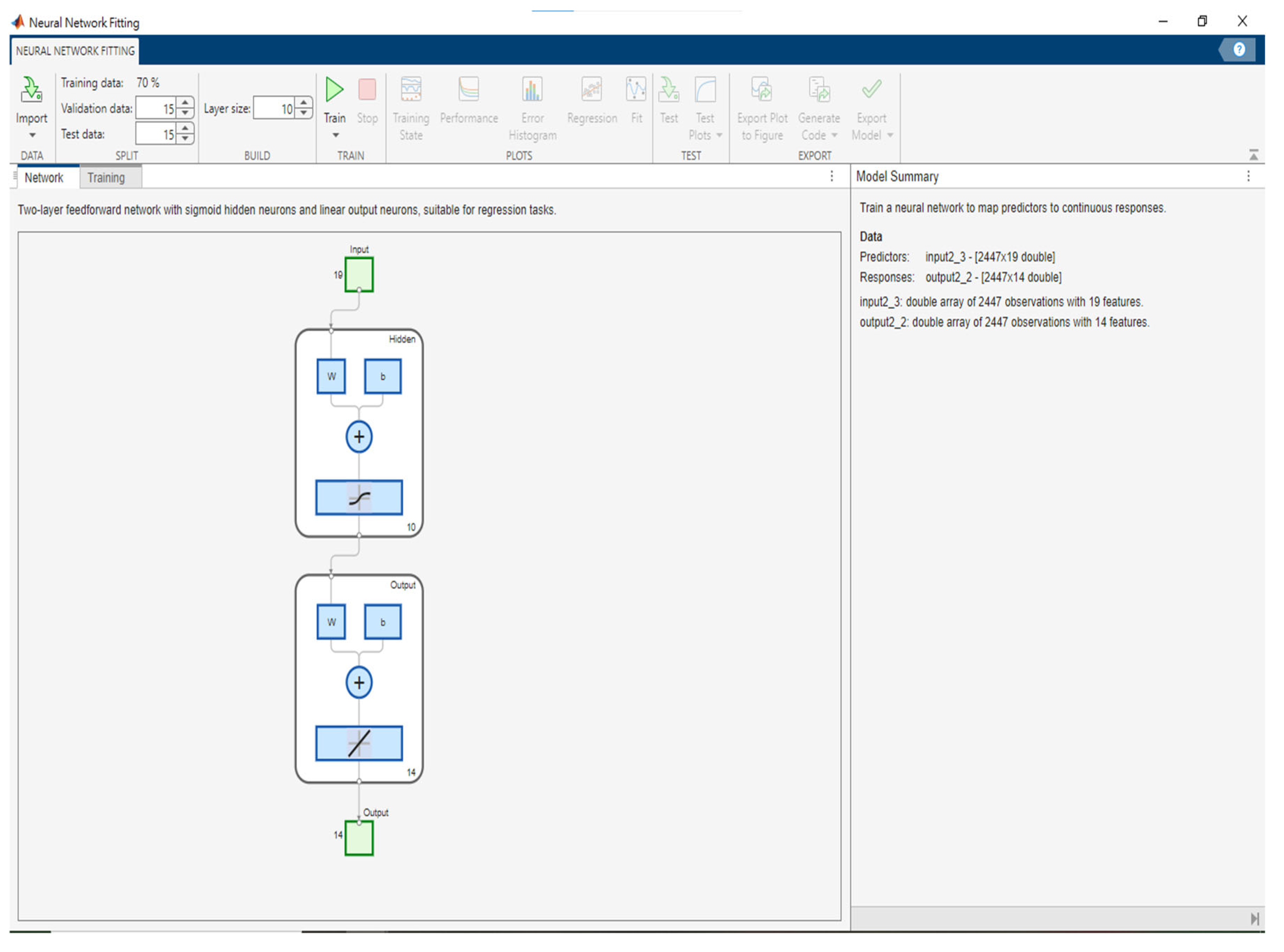

Figure 7.

MATLAB visualization interface for ANN programming (Case design in this study: 19 input variables, 14 output variables [i.e., groundwater levels of 13 pumping wells and 1 observation well, with 2,447 training samples]).

Figure 7.

MATLAB visualization interface for ANN programming (Case design in this study: 19 input variables, 14 output variables [i.e., groundwater levels of 13 pumping wells and 1 observation well, with 2,447 training samples]).

3.6.2. Implementation and Calibration of MODFLOW in Groundwater Modeling Systems and Big Data Modeling

Figure 8.

MODFLOW Construction Results for the Dewatering Engineering Case Study at the Building Site.

Figure 8.

MODFLOW Construction Results for the Dewatering Engineering Case Study at the Building Site.

Figure 9.

Calibration Results of the MODFLOW Using PEST with Observed Flow Data in the Case Study.

Figure 9.

Calibration Results of the MODFLOW Using PEST with Observed Flow Data in the Case Study.

Figure 10.

Schematic Representation of Large-Scale Data Output from the MODFLOW Simulation.

Figure 10.

Schematic Representation of Large-Scale Data Output from the MODFLOW Simulation.

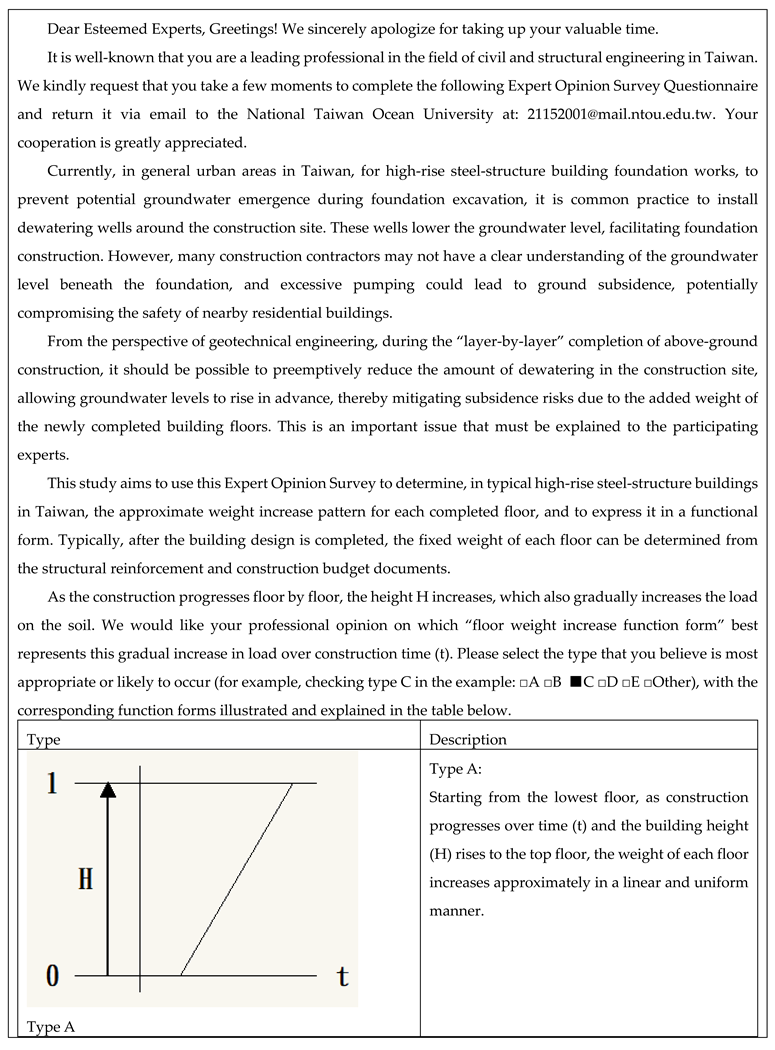

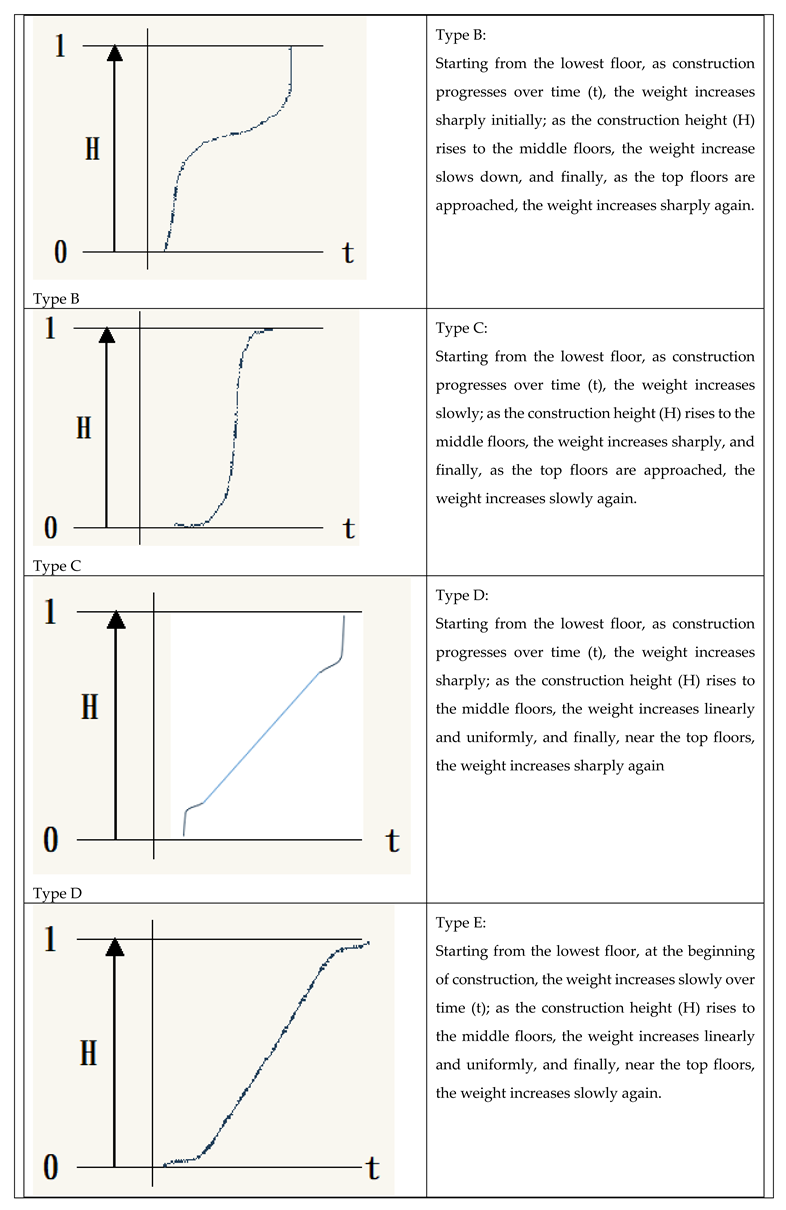

3.6.3. Questionnaire Design for Expert Opinion Survey and Guidance on Expert Knowledge and Experience

In this study, the questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first section provided an explanation of the survey’s objectives and the relevant theoretical background, while the second section focused on collecting expert opinions, including detailed explanations of the fuzzy membership functions representing the completion status of high-rise steel building floors.

The survey involved distributing 65 questionnaires to civil and construction engineering professionals, including 50 university professors, 9 government officials, and 6 industry practitioners. A total of 38 responses were received; however, 10 questionnaires were either blank or contained responses outside the scope of professional expertise, leaving 28 valid expert responses for analysis, the detailed expert survey questionnaire is provided in the Appendix.

4. Results

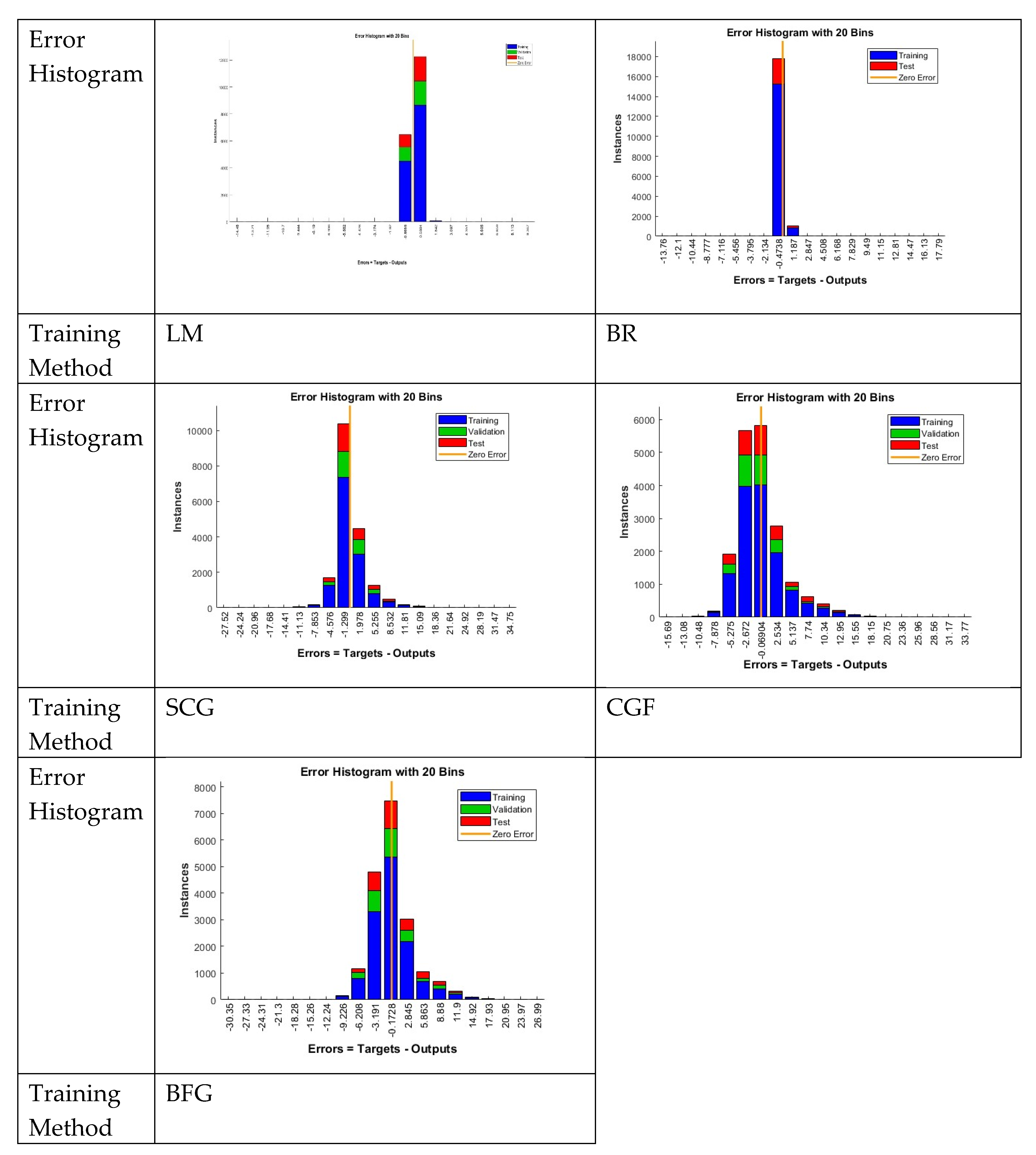

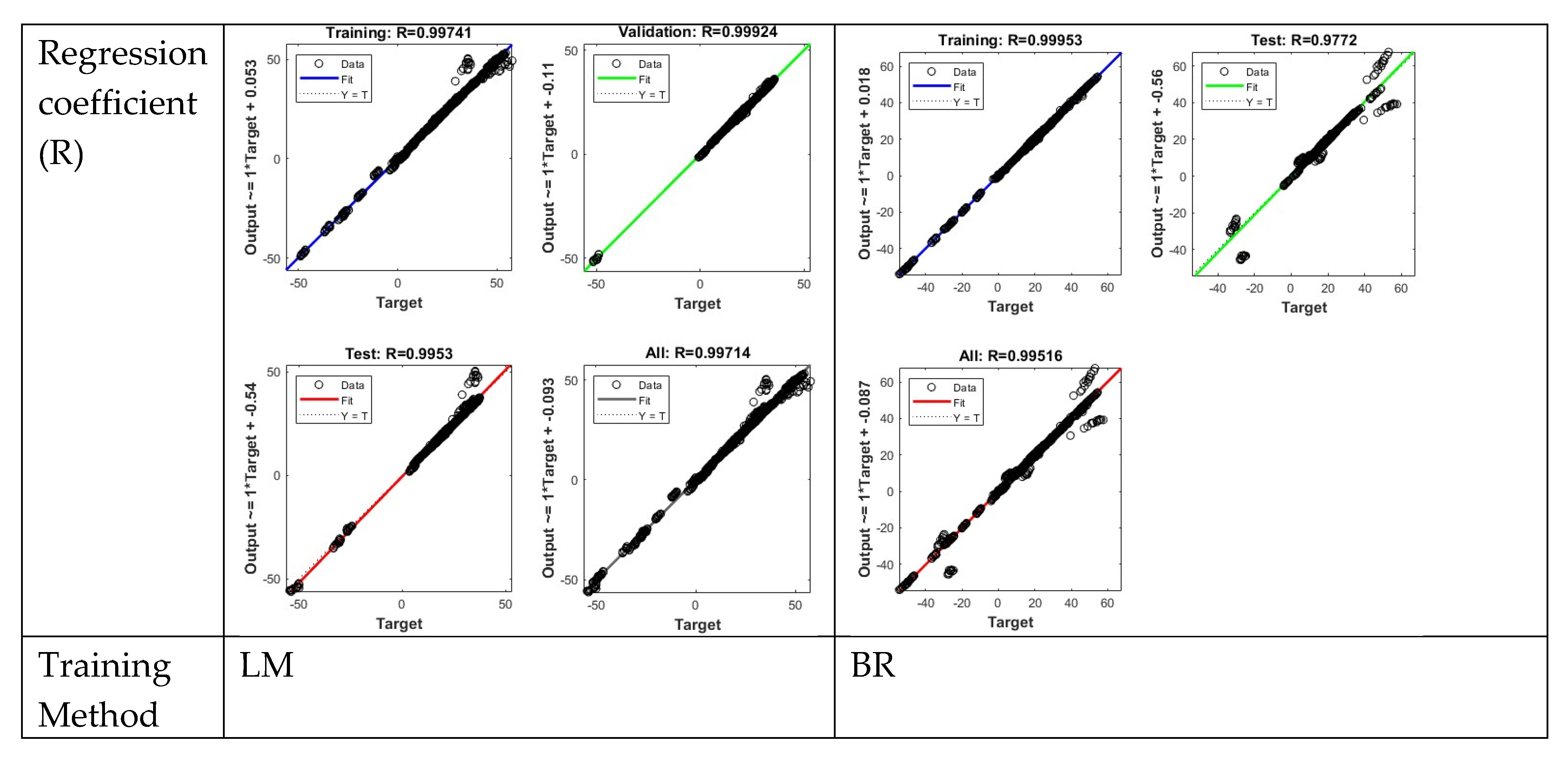

In this study, a neural network model was developed with a hidden layer consisting of 10 neurons (hiddenLayerSize = 10) and a training parameter of 1,000 epochs (trainParam.epochs = 1000). A total of 2,447 data samples were used for training, testing, and validation, with 70% of the data allocated for training and the remaining 30% equally split between testing and validation. The training and testing results are presented in the following figures.

The neural network was trained using five methods, including the Levenberg-Marquardt (L-M) algorithm, Bayesian Regularization (BR), Conjugate Gradient with Fletcher–Reeves updates (CGF), Scaled Conjugate Gradient (SCG), and Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno quasi-Newton method (BFG), all implemented in MATLAB. Evaluation metrics included error analysis between training, testing, and validation data, as well as the coefficient of determination (R-value) to assess the fitting performance of the neural network.

Furthermore, sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the contribution of all input parameters, identifying the key influential factors in the groundwater dewatering process at the construction site. The results of the expert survey on the fuzzy floor-completion membership function, together with the final calculation of the water-saving effect of the model, are summarized and analyzed in the following sections.

4.1. Neural Network Training, Testing, and Validation Results

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 illustrate the histograms of training, testing, and validation errors for neural networks constructed using different training methods. In addition, the corresponding coefficient of determination (R-value) plots are presented to evaluate the data fitting performance of each neural network model.

The results of the error magnitude between the test values and target values, the distribution of the error histograms, and the regression analysis with determination coefficient R indicate that among the five ANN training methods, the L-M and BR methods exhibit significantly smaller errors. Their regression determination coefficients R exceed 0.99, and the values from both methods are evenly distributed along the line where the test values equal the target values (i.e., Y = X), demonstrating higher accuracy. The other three methods deviate from the Y = X line, indicating lower precision in their training results.

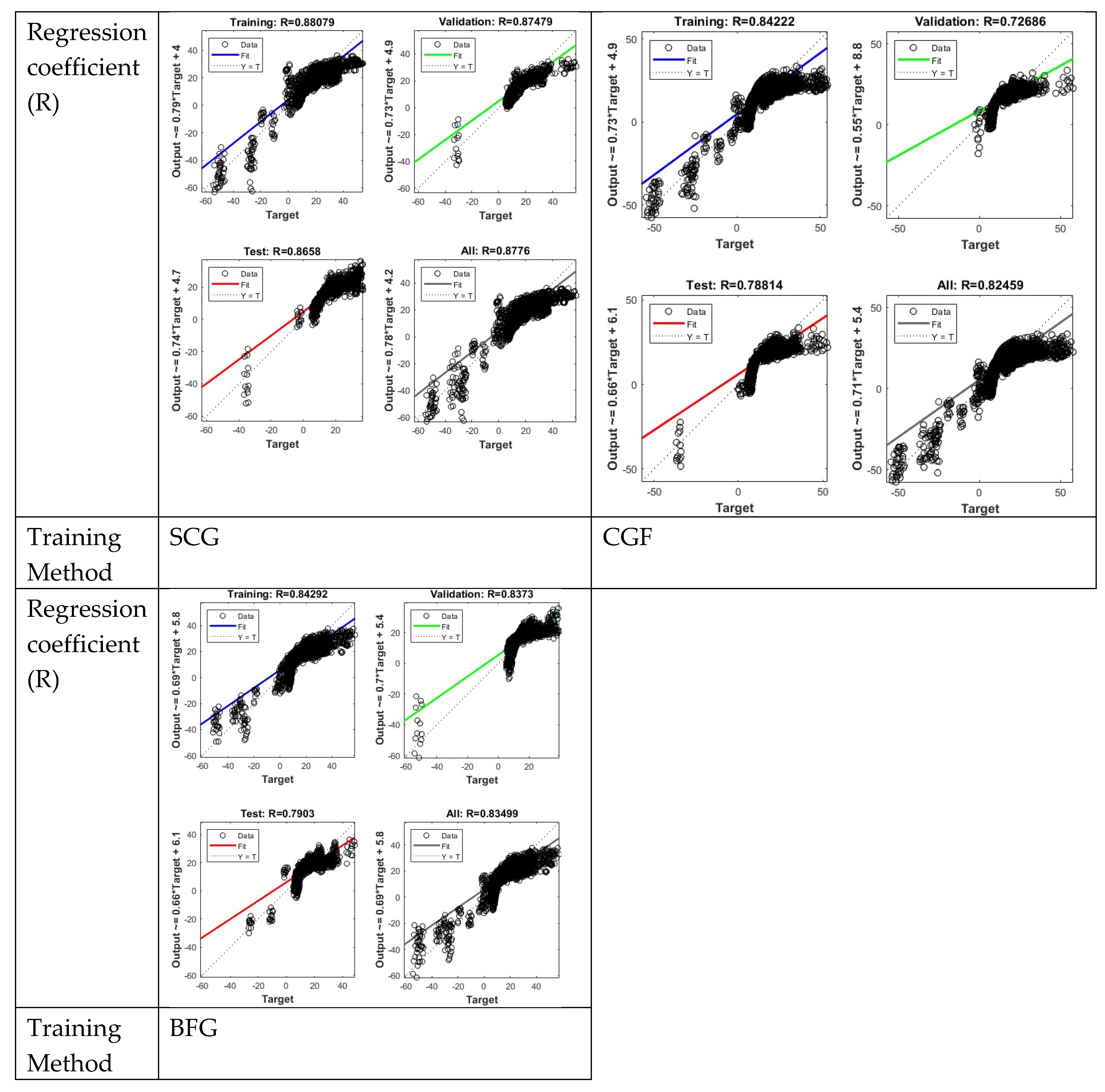

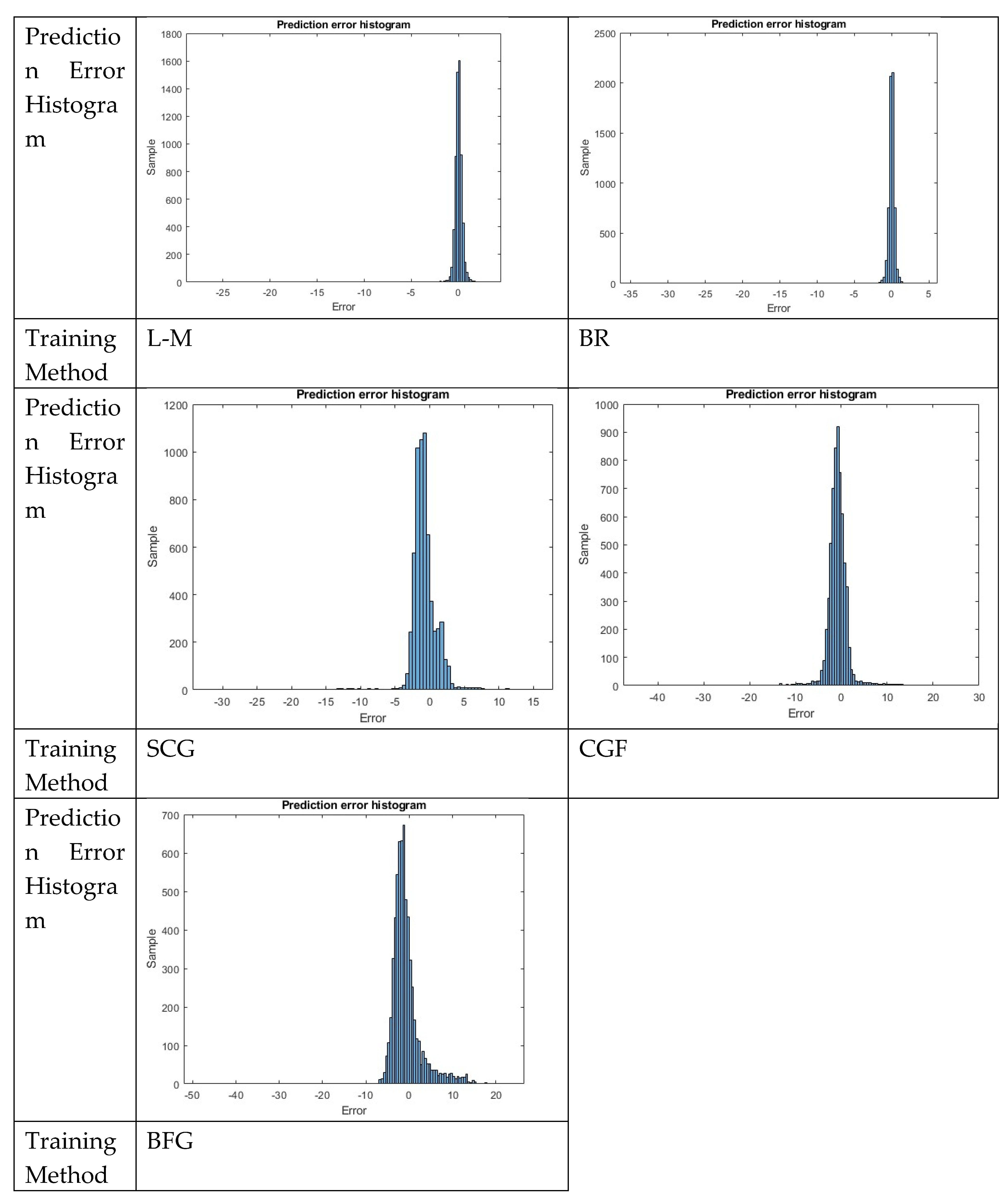

4.2. Comparison Analysis of ANN Predicted Values and Measured Values

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show the error histograms and regression analysis with determination coefficient R for the calculated predicted values versus the measured values.

The error histogram distribution and regression analysis of predicted versus measured values indicate that among the five ANN training methods, the L-M (Levenberg-Marquardt) and BR (Bayesian Regularization) methods exhibit significantly smaller prediction errors. The predicted values from these two methods are distributed uniformly along the line Y = X, demonstrating higher accuracy. The other three methods show deviations from the Y = X line, indicating lower prediction precision. These conclusions regarding predicted values are generally consistent with the results observed during the training and testing phases.

4.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis Results

Based on the results of the neural networks trained with five different training algorithms shown in

Figure 15, it can be observed that an increase in the dispersion of the simulated data leads to insufficient data representativeness. This condition may cause stronger interdependence among parameters, resulting in overlapping effects of each parameter on the output values. Such interactions are likely responsible for the poor training performance observed with the SCG, CGF, and BFG algorithms, and consequently for the partial distortion that appeared in the sensitivity analysis. Therefore, according to the sensitivity analysis results (

Figure 15), the LM training algorithm provides more reliable and interpretable outcomes. The sensitivity results obtained using the LM method indicate that the key parameter influencing groundwater level output is the hydraulic conductivity of the soil layer, followed by surface soil evaporation. The sensitivities of the remaining input parameters to the output are relatively similar, with only minor differences.

4.4. Training Time and Error Analysis of Different ANN Training Methods

Based on the two calculation results of training time and MSE error in

Table 1, it can be concluded that among the five ANN training methods, the L-M (Levenberg-Marquardt) method remains the most advantageous. When combined with the tansig activation function, it achieves sufficiently fast training speed and the smallest MSE error, with a minimum value as low as MSE = 1.5646535.

4.5. Analysis of ANN with Different Hidden Layer Numbers and Training Epochs

In this study, various ANN training methods, hidden layer configurations, and training epochs were tested to determine the optimal neural network setup within a computer-acceptable training time. Using the five aforementioned training methods, the number of hidden layers was set from 2 to 10, and the training epochs started from 100, increasing in increments of 100 up to 900, resulting in a total of 405 combinations. The mean squared error (MSE) was calculated for each combination. The heatmaps of MSE results for each training method are shown in

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18,

Figure 19 and

Figure 20

Among these 405 combinations, the minimum MSE was achieved using the trainlm method with 6 hidden layers and 600 training epochs, yielding an MSE of 0.65612858.

4.6. Survey Results of Floor Completion Membership Functions

Due to the “gradual” characteristic of fuzzy theory, which allows consideration of differences in actual completion levels, the gradual membership functions can be represented as continuous functions. Based on the expert survey questionnaire results, two main types of floor completion membership functions were selected: Type A and Type E.

Further consultation with the surveyed experts revealed the reason for choosing Type A (linear increase throughout the construction process) is that human resources and material transportation remain consistent during construction and do not fluctuate with the process. Hence, the linear membership function can reflect the completion process.

The difference between Type E (S-curve increase throughout the construction process) and Type A is that near the completion of each floor, interface integration issues may occur in Type E, and affecting the construction speed at the beginning and near the end of each floor completion.

Therefore, these two membership functions were used as the basis for calculating the reduction in groundwater extraction. The Type A membership function can be represented by a linear equation, while the Type E membership function can be expressed by an S-curve equation (as in Equations (8)– (9)). Since the number of experts selecting each type was similar, equal weighting was roughly applied to calculate the potential groundwater savings.

Linear Membership Function:

S-Curve Membership Function:

Where:

t = floor construction time

a =each floor construction start time

b = each floor completion time

k = shape adjustment parameter for the S-curve (here k=2 was used).

4.7. Water Savings Calculation Results Using the Fuzzy Floor Completion Membership Function Mode

Traditional dewatering practices usually follow only the basic regulatory requirements, maintaining the groundwater level 1–2 meters below the foundation slab and using safety monitoring measures to check for subsidence or tilting in nearby buildings.

In the case study of this research, the original groundwater level was approximately −6 meters, the building is designed as a 5-story underground and 21-story aboveground structure, with a foundation excavation depth of around 21 meters, before the start of floor construction, the groundwater level was maintained about 1.5 meters below the foundation slab. Using 13 dewatering wells with the same fixed dewatering rate, the expected drawdown at the site center should reach approximately 22.5 meters from the start of foundation construction. Each main structural floor requires about 60 days for construction.

After the start of underground floor construction in the case study, applying the fuzzy water-saving dewatering mode proposed in this study—where the increase in groundwater level (buoyancy) offsets the weight of completed floors—the calculated total dewatering volume for the construction site is reduced by approximately 2,927,400 metric tons compared to conventional regulatory-compliant dewatering methods.

This result demonstrates that the intelligent fuzzy floor completion water-saving dewatering mode developed in this study has a significant effect on conserving valuable groundwater resources.

5. Discussion

Based on the computational results of the model constructed in this study, the following discussion points are drawn:

The study demonstrates that using an artificial neural network (ANN) to simulate dewatering activities at high-rise building construction sites can successfully and accurately predict the impacts on groundwater levels, highlighting the strong predictive capability of ANN in complex groundwater hydrological environments.

The ANN model in this study was trained using five methods: Levenberg-Marquardt (LM), Bayesian Regularization (BR), Scaled Conjugate Gradient (SCG), Conjugate Gradient with Fletcher-Reeves updates (CGF), and BFGS quasi-Newton (BFG), with 10 hidden layers (hiddenLayerSize = 10) and 1,000 training epochs. Analysis of training, testing, and validation errors and the regression coefficient R indicates that the LM and BR methods outperform the other training methods. Comparison of predicted and observed groundwater levels further again, the results also confirm the superiority of LM and BR in prediction accuracy.

When combining the five ANN training methods with varying numbers of hidden layers, different training epochs, and various activation functions, the optimal ANN configuration was found to be the LM training method with the tansig activation function. Consequently, this study adopts LM with tansig for ANN-based groundwater level prediction to provide reliable input data for the fuzzy water-saving dewatering calculations.

Sensitivity analysis of the ANN model indicates that the primary parameter influencing groundwater output levels is the hydraulic conductivity, followed by surface soil evaporation. The remaining ANN input parameters show relatively minor differences in their impact on the output.

Comparing the fuzzy intelligent dewatering mode proposed in this study with conventional dewatering methods that comply only with basic construction regulations in Taiwan, the results show that the intelligent water-saving approach can significantly reduce unnecessary groundwater extraction during construction, offering substantial conservation of this valuable resource.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The final conclusions and recommendations of this study are summarized as follows:

The primary objective of this study was to predict and assess the impact of dewatering activities at high-rise building construction sites on groundwater levels. Considering the limitations of conventional time-series-based groundwater prediction models which often rely on too few parameters and the dilemma of not being able to use numerical simulation models due to the lack of clear physical mechanisms—this study provides an alternative approach for groundwater level assessment. Validation against measured field data confirms that artificial neural networks (ANN) can achieve accurate predictions.

In the absence of a large amount of data available for ANN training, this study adopted a small portion of actual case data in conjunction with the MODFLOW groundwater drainage simulation model for error evaluation and validation. The validation results indicated that, under variations of hydrogeological parameters, the simulated groundwater levels and drainage volumes produced by the developed MODFLOW model were all within the acceptable error range. This demonstrates that the established MODFLOW groundwater drainage model is capable of accurately representing the actual dewatering conditions. Consequently, this validated MODFLOW model was further utilized to perform large-scale data simulations, providing the training and prediction datasets required for the neural network modeling process.

To promote sustainable water resource management, this study applies ANN to simulate groundwater behavior at high-rise construction sites and integrates the principle of balancing building weight with groundwater buoyancy to proactively reduce dewatering volumes. This approach addresses the current practical issue in Taiwan of excessive groundwater extraction during construction.

Since ANN does not require explicit consideration of intermediate physical mechanisms or mathematical formulations of physical phenomena, predictions can be accurately obtained through repeated training and adjustment of neuron weights and biases. Future research could expand the ANN by including additional input variables (e.g., aquifer leakage, aquifer thickness, solar radiation, air temperature, and other hydrogeological parameters) and output variables (groundwater levels at the construction site) to better understand their relationships.

In Taiwan, limited and incomplete field measurements of groundwater and geological data make it challenging to fully leverage ANN’s predictive capability. By combining MODFLOW-generated large datasets with available site measurements for training and testing, this study demonstrates that ANN can achieve high prediction accuracy. This highlights the ANN’s superior performance in handling nonlinear and complex environments and suggests that with sufficient and comprehensive field measure data, accurate predictions of groundwater conditions are feasible in the future.

This study primarily addresses practical challenges in dewatering management at high-rise construction sites and proposes a pioneering water-saving dewatering concept management mode, future work can extend and refine this water-saving strategy.

The water savings achieved by the intelligent dewatering mode in this study are based on the hydrogeological conditions of Taichung City and may not represent the potential water-saving performance in other regions. Modeling in areas with different hydrogeological characteristics is expected to yield varying results.

Author Contributions

The contents of this article are part of J.-M.H.’s PhD dissertation research. C.-M.F. and C.-H.L. served as the academic advisers of J.-M.H. The research topic and theoretical framework were jointly discussed and determined by all authors. J.-M.H. was responsible for developing the research concept, model formulation, data analysis, software programming, methodological construction, and manuscript writing. C.-M.F. and C.-H.L. provided supervision, research guidance, and manuscript review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Architecture and Building Research Institute, Ministry of Interior, for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Expert Opinion Survey

References

- WARREN S. MCCULLOCH AND WALTER PITTS. A LOGICAL CALCULUS OF THE IDEAS IMMANENT IN NERVOUS ACTIVITY. The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics.1943, Vol. 5, pp. 115-133.

- https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~epxing/Class/10715/reading/McCulloch.and.Pitts.pdf.

- Emery Coppola Jr.; Ferenc Szidarovszky ; Mary Poulton; and Emmanuel Charles. Artificial Neural Network Approach for Predicting Transient Water Levels in a Multilayered Groundwater System under Variable State, Pumping, and Climate Conditions. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering.2003, Volume 8, Issue 6. pp. 348-360.https://ascelibrary.org/doi/abs/10.1061/(ASCE)1084-0699(2003)8:6(348).

- Yicheng Gong; Yongxiang Zhang; Shuangshuang Lan; Huan Wang. A Comparative Study of Artificial Neural Networks, Support Vector Machines and Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System for Forecasting Groundwater Levels near Lake Okeechobee, Florida. Water Resource Manage. 2016, 30:375–391. [CrossRef]

- Sanghoon Lee; Kang-Kun Lee; Heesung Yoon. Using artificial neural network models for groundwater level forecasting and assessment of the relative impacts of influencing factors. Hydrogeology Journal.2019, 27:567–579. [CrossRef]

- Zhenfang He; Yaonan Zhang; Qingchun Guo; Xueru Zhao. Comparative Study of Artificial Neural Networks and Wavelet Artificial Neural Networks for Groundwater Depth Data Forecasting with Various Curve Fractal Dimensions. Water Resource Manage. 2014, 28:5297–5317. [CrossRef]

- Huanhuan Li; Yudong Lu; Ce Zheng; Mi Yang; Shuangli Li. Groundwater Level Prediction for the Arid Oasis of Northwest China Based on the Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm and a Back-propagation Neural Network with Double Hidden Layers. Water. 2019, 11, 860; doi:10.3390/w11040860. www.mdpi.com/journal/water.

- Shishir Gaur; Apurve Dave; Anurag Gupta; Anurag Ohri; Didier Graillot; S. B. Dwivedi. Application of Artificial Neural Networks for Identifying Optimal Groundwater Pumping and Piping Network Layout. Water Resources Management. 2018, 32:5067–5079. [CrossRef]

- Sasmita Sahoo; Madan K. Jha. Groundwater-level prediction using multiple linear regression and artificial neural network techniques: a comparative assessment. Hydrogeology Journal. 2013, 21: 1865–1887. [CrossRef]

- Xian Li ; Longcang Shu ; Lihong Liu ; Dan Yin ;Jinmei Wen. Sensitivity analysis of groundwater level in Jinci Spring Basin (China) based on artificial neural network modeling. Hydrogeology Journal. 2012, 20: 727–738. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Ehteram; Zahra Kalantari; Carla Sofia Ferreira; Kwok-Wing Chau; Seyed-Mohammad-KazemEmami. Prediction of future groundwater levels under representative concentration pathway scenarios using an inclusive multiple models coupled with artificial neural networks. The Authors Journal of Water and Climate Change. 2022, Vol 13 No 10, 3620. [CrossRef]

- Mehrbakhsh Nilashi; Rozana Zakaria; Othman Ibrahim; Muhd Zaimi Abd. Majid ; Rosli Mohamad Zin ;Muhammad Waseem Chugtai ; Nur Izieadiana Zainal Abidin ; Shaza Rina Sahamir ; Dodo Aminu Yakubu. A knowledge-based expert system for assessing the performance level of green buildings. Knowledge-Based Systems. Knowledge-Based Systems. 2015, 86 194–209. [CrossRef]

- Manuel Carpio; Andrés J. Prieto. Expert Panel, Preventive Maintenance of Heritage Buildings and Fuzzy Logic System an Application in Valdivia, Chile. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 6922. [CrossRef]

- Aleksandras Krylovasa; Natalja Kosareva. Expert Estimates Averaging by Constructing Intuitionistic Fuzzy Triangles. Mathematical Modelling and Analysis. May 2015, Volume 20 Number 3, 409-421. [CrossRef]

- Yih-Tzoo Chen; Thi-Hien Dao; I-Hsin Chiu. A spherical fuzzy objective weighting framework for factors affecting bidding decisions for construction projects: A case study of Taiwan. Heliyon. 2024, Volume 10, Issue 16, e36420. [CrossRef]

- Aminah Robinson Fayek. Fuzzy Logic and Fuzzy Hybrid Techniques for Construction Engineering and Management. ASCE. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. 2020, 146(7): 04020064. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinos, A. Chrysafis; Demetrios Panagiotakopoulos; Basil K. Papadopoulos. Hybrid (fuzzy-stochastic) modelling in construction operations management. Int. J. Mach. Learn. & Cyber. 2013, 4:339–346. [CrossRef]

- Debashree Guha; Debjani Chakraborty. Fuzzy multi attribute group decision making method to achieve consensus under the consideration of degrees of confidence of experts’ opinions. Computers & Industrial Engineering. 2011, 60 493–504. [CrossRef]

- Shahab Hosseini; Behrouz Gordan; Erol Kalkan. Development of Z number-based fuzzy inference system to predict bearing capacity of circular foundations. Artificial Intelligence Review. 2024, 57:146. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Emiroglu; A. Tuna; A. Arslan. Development of an Expert System for Selection of Dam Type on Alluvium Foundations. Engineering with Computers. 2002, 18: 24–37.

- Mehrdad Sadeghi; Reza Naghedi ; Kourosh Behzadian ; Amiradel Shamshirgaran; Mohammad Reza Tabrizi ; Reza Maknoon. Customization of green buildings assessment tools based on climatic zoning and experts judgement using K-means clustering and fuzzy AHP. Building and Environment. 2022, 223 109473. [CrossRef]

- Pemika Hirankittiwong ; Nguyen Van Thanh ; Apichart Pattanaporkratana; Nattaporn Chattham ; Chawalit Jeenanunta ; Vannak Seng. Intelligent Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision-Making for Energy-Saving Building Designs in Construction. Energies. 2025, 18, 2726. [CrossRef]

- Yang ZP; Lu WX; Long YQ; Li P. Application and comparison of two prediction models for groundwater levels: a case study in western Jilin Province. China J Arid Environ. 2009, 73(4–5):487–492.

- Gonzalo L. Pita; B´arbara S. Albornoz; Juan I. Zaracho. Flood depth-damage and fragility functions derived with structured expert judgment. Journal of Hydrology. 2021, 603, 126982. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Shakir Ali Ali; Saman Ebrahimi; Muhammad Masood Ashiq; M. Sobhi Alasta; Babak Azari. CNN-Bi LSTM Neural Network for Simulating Groundwater Level. COMPUTATIONAL RESEARCH PROGRESS IN APPLIED SCIENCE & ENGINEERING (CRPASE).CRPASE: TRANSACTIONS OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING. March 2022, 8 (1) Article ID: 2748, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Vahid Gholami; Hossein Sahour. Prediction of groundwater drawdown using artificial neural networks. Environmental Science and Pollution Research.2022, 29:33544–33557. [CrossRef]

- Md. Arif Chowdhury; Hasnat Sabrina; Rashed Uz Zzaman; Syed Labib Ul Islam. Green building aspects in Bangladesh: A study based on experts’ opinion regarding climate change. Environment, Development and Sustainability.2022, 24:9260–9284. [CrossRef]

- Dmytro Perepolkin; Erik Lindstrom; Ullrika Sahlin. Quantile-Parameterized Distributions for Expert Knowledge Elicitation. Decision Analysis. 2025, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–20.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).