Introduction

In recent decades, attention has grown on managing and protecting heritage sites. Locals’ concerns about the value of cultural heritage are key obstacles to adopting sustainable communities [

1]. Heritage tourism depends on sustainable management and local environmental responsibility, requiring a balance between visitation, authenticity, and conservation, as high tourist numbers can have negative effects [

2]. Various management strategies have been proposed to mitigate these impacts and promote responsible behavior among heritage visitors [

3,

4].

Historical sites, as remnants of their communities, should be preserved as symbols of ethnicity, culture, and history. Awareness of attachment to these places fosters cultural consciousness and a sense of belonging [

5]. Environmentally conscious behavior is essential for heritage tourism, enhancing cultural heritage sustainability while benefiting the local economy and environment, though its development remains poorly understood.

Despite extensive research on heritage site development and management [

6,

7,

8], few studies have examined local visitors’ heritage responsibility behaviors.

To understand both general and site-specific sustainable behaviors of local visitors, this study conceptualizes sustainable behavior within heritage tourism, drawing on environmental psychology and tourism literature. It examines the antecedents of heritage resource conservation behaviors from a traditional cultural heritage protection perspective. An extended Norm Activation Model (NAM), widely used to explain pro-environmental behavior, is applied, incorporating place attachment as an additional variable.

Place attachment reflects the emotional connection residents or locals feel toward a location, which strengthens with social connections [

9]. This has important implications for heritage site management, as visitors’ appreciation and experiences at heritage sites can enhance support for heritage preservation and promote sustainable tourism development [

10].

This study aims to provide tourist organizations and heritage managers with insights to enhance sustainable heritage tourism planning by leveraging locals’ responsible behaviors. The success of sustainable tourism at cultural sites largely depends on local behaviors that support heritage management efforts. Accordingly, the study investigates whether local visitors’ awareness of negative consequences, ascribed responsibility, personal norms, and place attachment influence their pro-environmental behaviors, using the Norm Activation Theory as a framework.

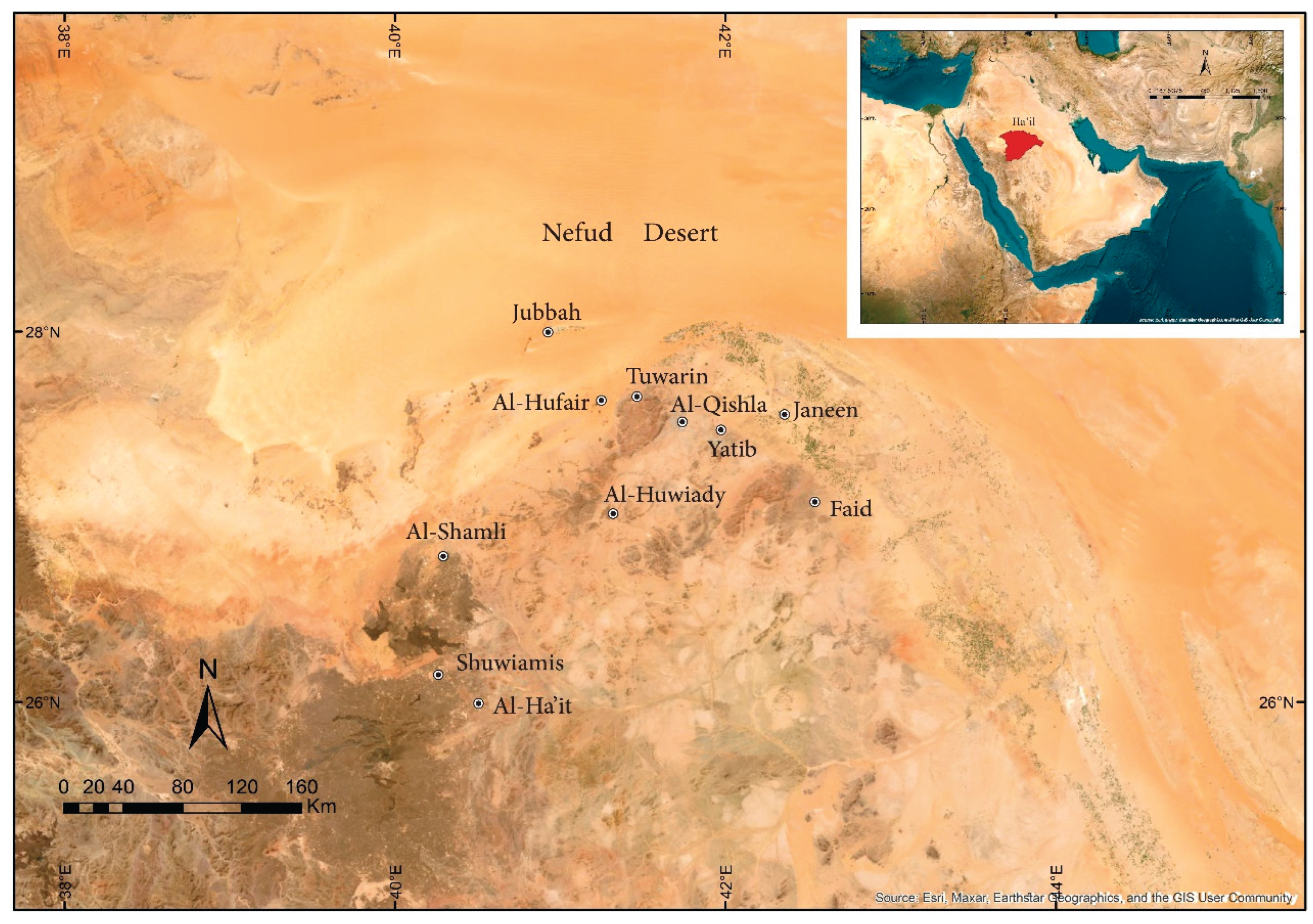

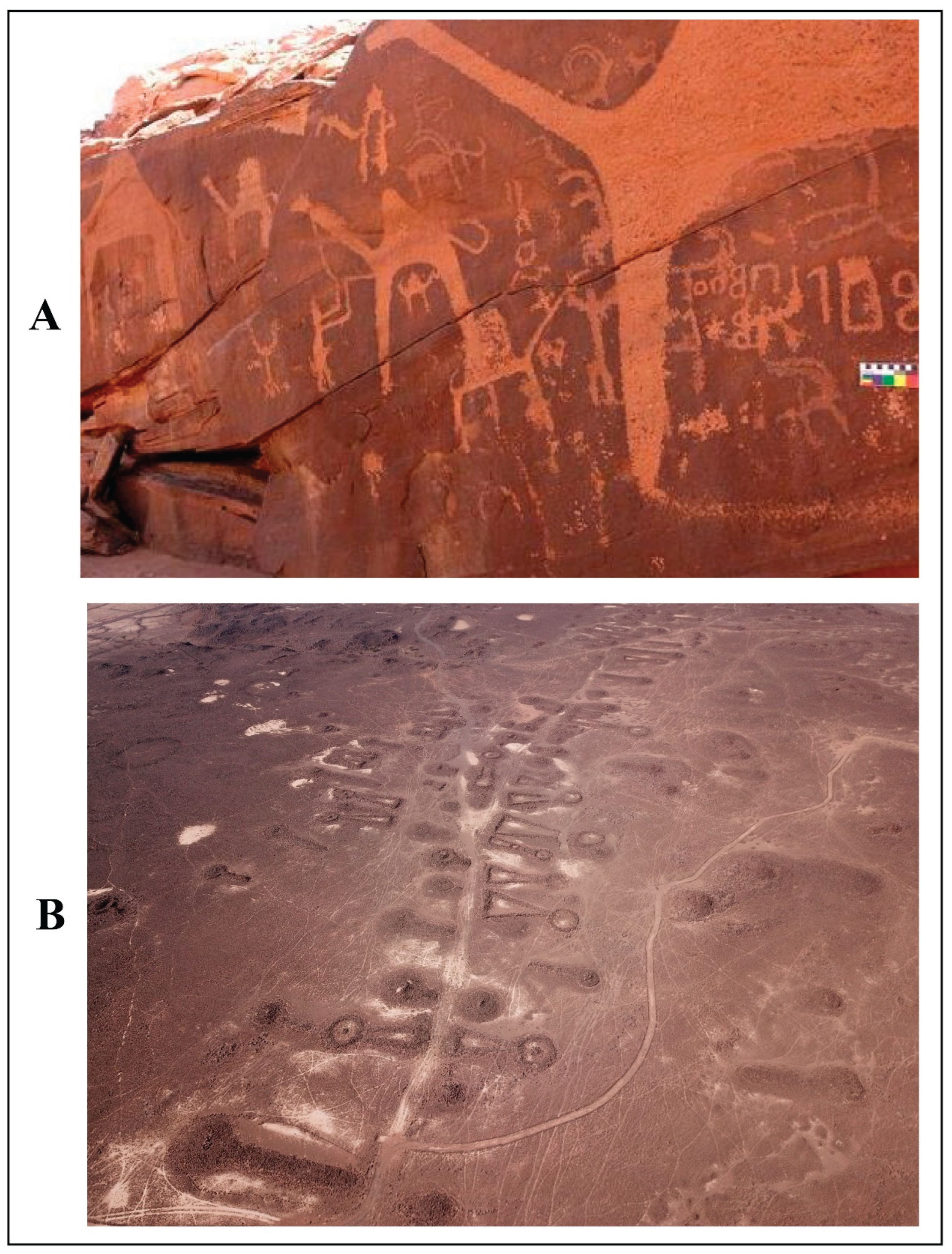

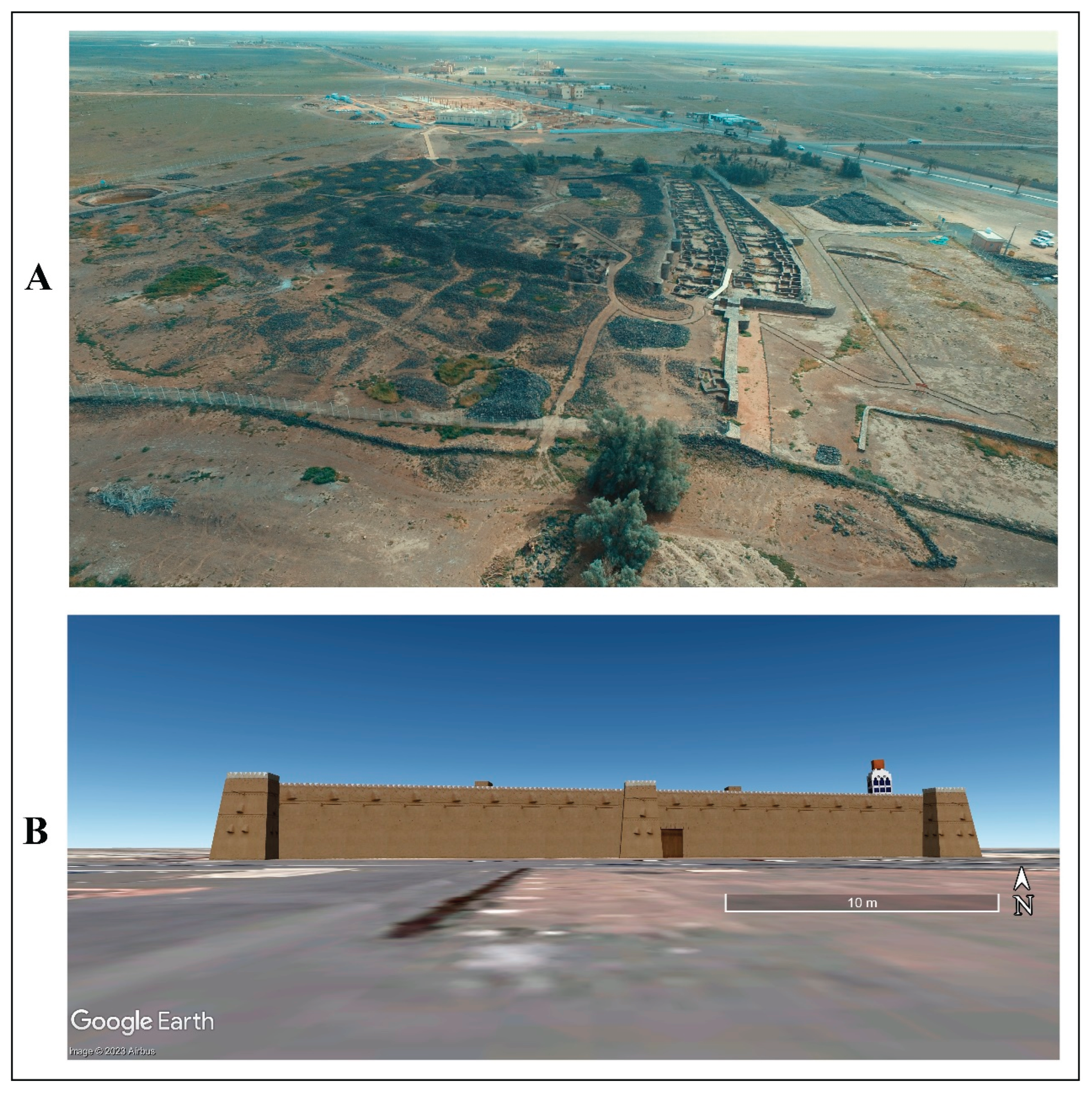

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), with its rich cultural heritage, has seen growing demand for cultural heritage tourism due to economic development. Sustainable heritage development requires scientifically grounded guidelines. Accordingly, this study focuses on Hail, one of KSA’s prominent cultural heritage sites, known for its historical significance. The research addresses the following questions:

How does awareness of negative consequences influence ascribed responsibility?

What is the impact of personal norms on ascribed responsibility?

How does ascribed responsibility mediate the relationship between awareness of consequences and personal norms?

To what extent do personal norms positively affect pro-environmental behavioral intentions?

How does place attachment positively influence pro-environmental behavioral intentions?

The tourism industry and cultural heritage are closely linked, as effective tourism management supports destinations and heritage resources, making them financially sustainable. The concept of "heritage" is multifaceted and evolving [

11], encompassing people, places, activities, monuments, artifacts, landscapes, and nature, with European heritage recognizing seven categories, including folk customs and traditions [

12]. Cultural heritage is defined as the artistic or symbolic material passed from one culture to another, representing a legacy for all humanity [

13]. Heritage tourism, a subset of cultural tourism, centers on heritage as the primary motivation for tourists [

14].

Heritage tourism is rapidly expanding internationally, driven by rising income, education, technological advancements, global awareness, and interest in historical, cultural, and natural sites [

15]. Cultural heritage tourism, which emphasizes cultural, historic, and environmental values, has become a key sector, attracting attention from scholars and professionals for its management and protection [

16,

17]. It supports the preservation of indigenous cultures, arts, crafts, and historical traditions while stimulating the economy and increasing employment [

18,

19]. Sustainability is essential to balance heritage conservation, tourism, and economic development, as neglecting economic and social factors can lead to irreversible heritage loss [

20]. Heritage tourism depends on sustainable resource management and local attitudes toward environmental and cultural preservation. Effective heritage-based tourism fosters sustainable development, though management approaches can produce both positive and negative outcomes, making the prioritization of cultural assets and sustainability critical [

21,

22].

Researchers use various terms to describe behaviors aimed at environmental conservation, including pro-environmental, environmentally significant, responsible, sustainable, and environmentally concerned behaviors [

23,

24,

25]. Pro-environmental behavior is defined as actions that reduce harm to built and natural environments, requiring individuals to balance personal interests with environmental benefits and can be single- or multi-dimensional [

26,

27,

28]. At heritage sites, it encompasses local visitors’ awareness of site values, willingness to preserve resources, and actions to safeguard cultural and natural assets for future generations [

29]. Encouraging pro-environmental behavior helps protect these assets, though balancing visitor numbers, authenticity, and preservation is essential for long-term sustainability [

30].

Norm Activation Theory (NAT) posits that altruistic behavior arises from a moral obligation to prevent harm to valued objects [

31]. The NAT framework has been applied to environmentally responsible behavior in contexts such as green hotels, heritage destinations, ecologically responsible conventions, cruise tourism, and environmental education [

32,

33,

34,

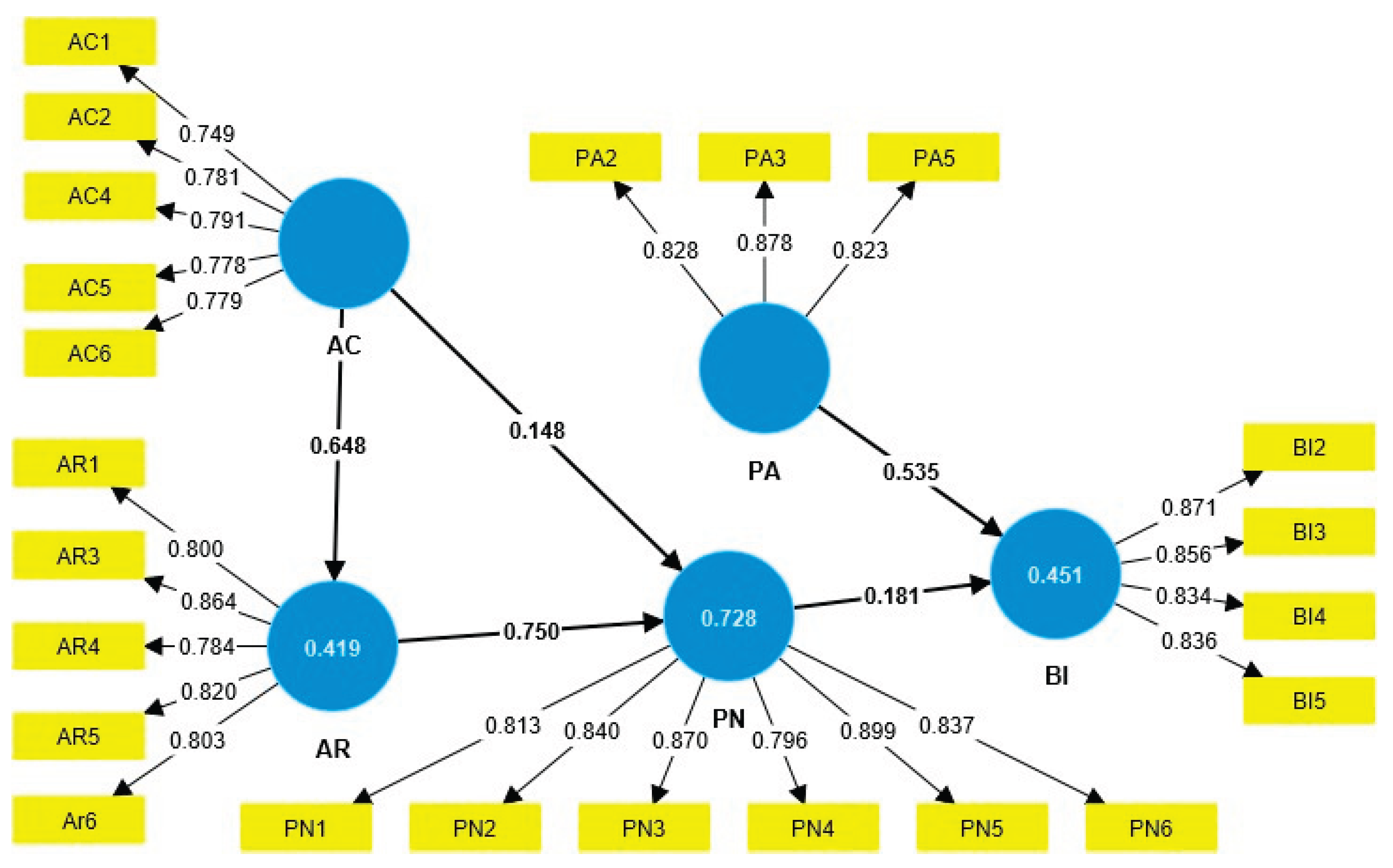

35]. NAT comprises four constructs: awareness of consequences (AC), ascription of responsibility (AR), personal norms, and environmentally responsible behavior intention [

36,

37]. According to NAT, individuals’ pro-social or altruistic intentions—such as volunteering—are shaped by personal norms, awareness of problems, and ascribed responsibility, all stemming from a sense of moral obligation [

38]. Awareness of potential negative consequences activates personal norms, guiding individuals to choose actions that avoid harm [

39].

In this research, NAT is extended by integrating place attachment into the formation of heritage tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior, emphasizing heritage site preservation. AC reflects an individual’s awareness of the negative consequences of non-social actions, including environmental impacts, while AR represents the sense of accountability for these negative outcomes [

40].

Research shows that simply recognizing environmental issues does not automatically foster responsibility; individuals must be aware of the impact of their actions [

41]. Eco-friendly behavior links environmental issues to personal actions, promoting accountability [

42]. In tourism, assigning accountability increases awareness of stakeholders’ actions, encouraging responsible behavior among tourists [

43,

44]. However, generational differences exist: while all generations recognize over-tourism, younger individuals often show indifference [

45]. Moreover, raising awareness alone is insufficient for responsible travel, as tourists frequently struggle to understand tourism impacts and sustainability information, resulting in a denial of responsibility [

46,

47].

The hypothesis is as follows:

H1: Ascribed responsibility is affected positively by awareness of the negative consequences.

Within the Norm Activation Theory (NAT) framework, personal norm (PN) reflects a moral obligation to act, originating from individuals and enhancing pride and self-esteem [

48]. PN highlights an internal commitment to pro-environmental behavior, shaped by awareness of environmental consequences and personal responsibility. Ascribed responsibility (AR) involves feeling accountable for the negative outcomes of non-pro-social actions, often linked to guilt and belief in one’s impact on others [

49]. NAT posits that norms are activated when individuals recognize the benefits of their behavior and feel responsible for its negative consequences [

50]. Evidence from conservation and tourist behavior indicates that moral obligation drives environmentally responsible actions [

51], and assigning responsibility triggers personal norms, with stronger ascription leading to behaviors aligned with these norms [

52,

53,

54].

The hypothesis is as follows.

H2: Ascribed responsibility affects positively the personal norms.

Research on pro-social and pro-environmental behavior emphasizes the strong links between problem awareness, ascribed responsibility, and personal norms [

50]. According to NAT, self-awareness of potential negative outcomes activates personal norms, fostering responsible behavior [

31]. Personal norms have both direct and mediating roles in amplifying the effects of awareness of consequences and ascribed responsibility on altruistic behavior [

55,

56]. Studies show that problem awareness and ascribed responsibility significantly influence travelers’ environmentally conscious choices, with ascribed responsibility directly shaping personal norms [

31,

40]. Additionally, awareness of negative consequences enhances a sense of responsibility and strengthens personal norms, which in turn positively impacts behavior [

35,

57]. Based on these findings, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Ascribed responsibility moderates significantly the impact of awareness of consequences on the personal norms.

Personal norm, moral norm, and moral duty are often used interchangeably in the literature [

58], guiding pro-environmental and pro-social behavior. Individuals’ sense of moral duty to minimize harm strengthens when they perceive wrongdoing [

59]. Personal norms represent internalized social norms and moral obligations [

32], and are long-lasting beliefs about personal responsibility, making them key drivers of environmentally sustainable behavior. Research shows that personal moral norms strongly predict support for pro-environmental interventions and behavioral intentions [

60]. A heightened sense of moral obligation can promote eco-friendly actions by eliciting anticipated guilt and pride, with evidence indicating that individuals are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors when they perceive them as morally required [

44,

61]. Planned environmentally sensitive behavior is also influenced by personal norms [

62].

Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses in the heritage tourism setting.

Hypothesis 4: Personal norms affect positively pro-environmental behavioral intention.

Place attachment, derived from attachment theory, is a key concept in environmental psychology, reflecting social and emotional bonds to specific environments such as places, houses, landscapes, and cities [

63,

64]. Its dimensionality varies across studies, with some viewing it as one-dimensional and others identifying dimensions such as place identity, place affect, place dependence, and place social bonding [

65,

66]. Place identity captures an individual’s connection to their environment through memories, perceptions, concepts, and emotions [

67]; place affect reflects sentimental attachment [

68]; place dependence denotes the importance of a location for specific activities [

25]; and place social bonding represents social connections among people, communities, and cultures at a location [

66,

69]. Overall, place attachment represents the emotional investment and value individuals place on a particular environment [

70]. Empirical research shows that place attachment plays a significant role in shaping pro-environmental intentions and behaviors [

68,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75], and it strongly influences heritage protection through tourists’ attachment to heritage sites and destinations [

76,

77]. Based on these findings, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5: Place attachment positively affects positively pro-environmental behavioral intention.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we give a short review of the associated theory, which results in the development of the conceptual model and hypotheses. Then, we describe the data collection and analysis. Next, the results are presented. The article closes with a profound discussion of the findings, implications, the limitations and future research.

Discussion

The topic of environmentally responsible behavior in heritage sites has not received much research attention. By including place attachment construct into the original NAT, the current study aims to improve understanding of environmentally responsible behavior of local visitors. This study examined the correlations that exist between the intention to act in an ecologically responsible manner, personal norms, place attachment, responsibility ascription, and the intention to act in a way that is ecologically friendly.

The findings showed that the suggested model has a higher capacity for predicting the environmentally responsible actions of local visitors in heritage sites. The NAT's conceptual framework played a crucial role in illuminating the environmentally conscious actions of heritage site visitors. In particular, the results showed that awareness of consequences directly affects ascribed responsibility, and that both awareness of consequences and ascribed responsibility drive personal norms, which in turn affects visitors' behavioral intention. According to [

104], among others, these findings are consistent with the first stream in the connection between the three basic variables in the NAT. To sum up, every hypothesis was validated, and every study goal was accomplished.

The research findings make multiple contributions to the literature on sustainable heritage tourism. Firstly, the study applied the NAT approach to the literature on heritage tourism, which broadened its scope in comparison to earlier studies (e.g., [

35] by incorporating a significant variable (place attachment).

Overall, the application of environmental psychology's insights into the field of tourism management regarding the connections between place attachment, personal norms, awareness of consequences, and pro-environmental behavior strengthens the validity of the NAT framework in the context of heritage tourism. This is because the inclusion of place attachment has been shown to be crucial in activating locals' pro-environmental behavior. Second, the issue of sustainable heritage tourism for the unique context of Hail is relevant in practice despite the theory and model used in this research, since other destinations facing a similar issue may find the article's analysis useful from a managerial standpoint.

The results confirm that there is a significant relationship between awareness of the consequences and ascription of responsibility to mitigating possible damage to heritage sites. The strong correlation might be attributed to the community's sense of concern and responsibility for the long-term preservation and development of cultural heritage resources. This finding is consistent with previous empirical environmental research suggesting that attribution of responsibility is “activated” by awareness of consequences [

35,

44,

105]. When tourists are more conscious of and worried about the effects, they are more inclined to behave responsibly [

44]. To cultivate strong responsibility ascription and environmentally conscious behavior, it is crucial to raise awareness of the consequences of tourism [

31].

Additionally, the original norm activation model with empirical evidence predictably indicates that the relationship between awareness of consequences and personal norm is entirely mediated by the ascription of responsibility [

48]. However, other studies did not confirm a significant relationship between awareness of the consequences and ascription of responsibility. For example, in order to encourage appropriate travel behavior, [

46] found that raising awareness alone would not be sufficient. Visitors found it difficult to grasp how to react to the effects of tourism and had a poor level of awareness of them. Therefore, as hypothesized in H1 and H3, personal norms are influenced by both awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility. Ascription of responsibility is strongly related to personal norms. Ascribed responsibility has a stronger impact on personal norms than being aware of the consequences. This demonstrates how crucial the notion of Ascription of responsibility is in establishing the personal norms of visitors. This finding aligns with earlier environmentalism-related empirical research, which argues that personal norms will be "activated" by consequences awareness and awareness of consequences [

51,

53,

54,

106]. The NAT model states that when people are aware of the benefits of their actions and take responsibility for the consequences of acting in a non-pro-social way, they are more likely to activate norms [

50]. Furthermore, the intention of tourists to support heritage places and their personal norms were shown to be significantly correlated. The significance of personal norms in forecasting pro-environmental conduct corroborates the findings of [

60]. This finding demonstrate how engaging in environmentally friendly activity can be prompted by a stronger awareness of one's own personal norms. Further emphasizing this point, [

62] state that people are more likely to plan to conduct an environmentally good activity when they sense profound obligation.

The findings also confirm that there is a significant relationship between place attachment and behavioral intention to mitigate possible damage to heritage sites. This finding is consistent with previous empirical environmental research [

30,

74]. Researchers came to the conclusion that "place attachment" may play a major role in forecasting visitors' behavioral intentions toward the area after discovering that travelers and their destination had to have an emotional tie [

107]. Furthermore, [

105] found that pro-environmental behaviors are more strongly influenced by place attachment than by awareness of consequences of disasters.

The results of this study contribute to the literature on environmentally sustainable tourism in several ways. First, the results of this study are of theoretical value because the process of forming individuals' pro-environmental behavioral intentions to reduce negative impacts on heritage sites is described for the first time in Saudi Arabia. Second, this study was motivated by the researchers' call to promote local visitors` support for cultural heritage tourism. Third, in order to test the interplay of relationships between residents' intentions to support cultural heritage tourism and their awareness of the consequences, ascription of responsibility, subjective norms, and place attachment in a single integrative model, we drew on literature on environmental psychology, environmental social psychology, and sustainable tourism. Fourth, by including the place attachment concept, this study expanded on the norm activation theory. It has been shown that place attachment construct increases the predictive value of NAT in predicting the behavioral intentions of visitors from the area. Put differently, the behavioral intentions of local visitors are more accurately predicted by PA when combined with NAT constructs. As a result, the current study provides a clearer explanation of people's intents to support cultural sites through eco-friendly behavior. These findings provide insights into how place attachment influences the ability of local visitors in heritage sites to behave sustainably and offer strategies for raising the expected feelings of tourists.

Several managerial implications emerge from the present research:

Raise awareness of negative consequences of irresponsible behavior at heritage sites to foster responsibility and promote ecologically conscious conduct. Destination managers and local governments can run campaigns and increase sensitivity to environmental issues related to heritage tourism.

Promote eco-friendly personal norms among tourists visiting historic sites. Encourage tourists to engage in environmentally friendly practices and educate them about the detrimental effects of careless actions on heritage resources.

Incorporate environmental protection advice into scenic maps and tickets to visually and audibly educate local visitors about the conservation of heritage treasures.

Educate local visitors about the significance of practicing ecologically responsible behavior and the negative effects of inappropriate behavior on the ecosystem. This will enhance their personal norms and sense of responsibility for conserving heritage sites.

Utilize various environmentally friendly communication methods to alert local visitors of their responsibility for environmental issues resulting from their activities. Emphasize ascribed responsibility to activate the personal norms of the community's citizens.

Implement initiatives that support the instillation of environmental protection duty in local visitors.

Destination managers and policy makers should improve and cultivate a sense of responsibility toward environmental issues, for instance, by communicating the consequences of individual behaviors that, although individually bearable, when thousands of people become intolerable (like littering in heritage sites).

This study showed that the level of visitors ' place attachment is high and that place attachment in the heritage of the Hail area is an important predictor of pro-environmental behavior. It's important to strength community visitors' place attachment via creating opportunities to participate in heritage sites planning and decision-making. Furthermore, government should try their best to develop tourism and balance the residents' dependence and identity of local economy, society, culture and environment in heritage sites at the same time, as any aspect of place attachment may affect environmental conservation behaviors positively.

The promotion of their cultural tourism and heritage industries depends on a number of tourist locations' heritage sources. The discourse surrounding cultural resource conservation and visitation has grown over time, with calls for the implementation of more sustainable solutions that are nevertheless essential for heritage locations. This is also a result of how heritage management has evolved, which demands combining a more visitor-focused strategy that takes into account visitors' choices and the quality of their individual experiences with a more conventional curatorial approach motivated by the necessity of conservation. By examining the shared impacts of awareness of environmental consequences, ascribed responsibility, personal norms, and place attachment on pro-environmental behavioral intention, this study adds to the body of knowledge already available on pro-environmental behavioral intention. The suggested model's empirical testing yielded the following results: That awareness of consequences directly affects ascription of responsibility; awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility drive PN; The ascription of responsibility completely mediates the link between awareness of consequences and personal norm; Ascription of responsibility have a greater influence on personal norms than awareness of consequences ; There was a significant correlation found between tourists' intention to support heritage sites and their personal norms; and Place attachment directly affects behavioral intention to mitigate possible damage to heritage sites.

The study also revealed that the region of Ha’il is rich in heritage sites, which are frequented by many visitors. To ensure its sustainability, future visions must be developed on local community awareness about the importance of heritage and its role in sustainable tourism development, and to clarify ways to protect the heritage sites through workshops, lectures, and official media. As well as trying to create a partnership between decision-makers, stakeholders, and visitors to develop tourist behavior in these heritage sites and ensure their preservation for future generations.