1. Introduction

Traditional performing arts have long served as dynamic carriers of folk beliefs and communal identity, mediating between the sacred and the secular, the past and the present. Teochew Opera (潮剧), a 580-year-old regional operatic tradition inscribed on China’s National Intangible Cultural Heritage List, stands as a paradigmatic example (Wu & Lin, 2015). Rooted in the Southern Opera (南戏) tradition of the Song and Yuan Dynasties, it has not only preserved Teochew cultural heritage across Guangdong, southern Fujian, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Southeast Asian diaspora communities (e.g., Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore) but also functioned as a living repository of Chaoshan folk beliefs and the emotional bonds among over 20 million Teochew people worldwide (Lin, 2019; Wu & Lin, 2015; Zhang, 2025).

Within Teochew Opera’s repertoire, Wufu Lian (五福连, Five Blessings Continuum) occupies a unique ritual position: as a sequence of five opening plays classified as Ban-sian-xi (扮仙戏, Ritual Deity Plays), it encapsulates the core of Chaoshan folk beliefs centered around the “Five Blessings” (五福)—longevity (寿), prosperity (财), official rank (禄), progeny (子), and familial harmony (团圆)—transforming abstract folk aspirations into tangible symbols embedded with profound connotations of prayer and auspiciousness (Lin, 1993; Zhang, 2024).

For centuries, Wufu Lian has operated as a ritual mechanism for reinforcing Chaoshan folk beliefs both within and beyond the Chaoshan region. Through repeated performances, this symbolically rich theatrical form evolved into a shared cultural memory among the Teochew people, significantly strengthening their communal identity. Within the Chaoshan homeland, performances during festivals and ceremonial occasions reinforced clan relations; in overseas communities, Wufu Lian became a vital medium of identity preservation—its stagings in Singaporean temples or Thai Teochew associations reconnected migrants with the belief systems of their homeland and sustained a sense of belonging amid geographic displacement (Yang, 2019; Huang & Zeng, 2020). In this way, Wufu Lian transcended mere theatrical performance to function as a “ritual of communion,” binding individuals together through shared beliefs, collective memory (Carey, 1989; Schechner, 1994), and a distinctive Teochew identity.

However, the digital revolution has fundamentally altered the transmission ecology of Teochew Opera and Wufu Lian. Platforms such as Bilibili, Douyin (TikTok China), and YouTube have dissolved the geographic and temporal constraints traditionally imposed by temple squares and ancestral halls, enabling Wufu Lian to circulate in the form of digital clips, full performances, and user-generated content (Huang, 2023; Nyman, 2022). Bilibili, a video platform particularly popular among young Chinese audiences, has become a pivotal space for such content. Its youth-dominated user base, interactive features—such as danmu (弹幕, “bullet screen” comments)—and algorithm-driven curation have collectively transformed the consumption and interpretation of Wufu Lian (Gao et al., 2023; Zheng & Xia, 2023). While digital mediation has substantially expanded the opera’s reach—connecting diasporic Teochew communities in Malaysia with rural Chaoshan villages and urban Chinese youth (Huang, 2020)—it also raises pressing questions concerning the evolution of folk belief systems, communal identity, and traditional performance art in the digital era.

Current academic research on Ban-sian-xi predominantly focuses on two domains: the historical evolution and development of Ban-sian-xi, and the theatrical artistic forms of this opera tradition. Relevant studies on the history of Teochew Opera include the works of scholars such as Lin Li (2021), Chen Hanxing (2022), Lin Xiaowei (2023), and Zhu Qinghui (2020). Among them, Yang Xiaoqing (2017) systematically delineated the formation and historical evolution of Teochew Opera. Zhu Qinghui (2020) explored the importance and specificity of preserving Teochew Opera and provided strategic recommendations for the protection and transmission of Teochew culture.

Other scholars have examined the theatrical artistic forms of this opera, among others. Liang Yi (2020) analyzed the symbolic meanings embedded in the lyrics, body movements, and props of Ban-sian-xi. Zhang Ludan’s (2024) research specifically focuses on Wufu Lian as its object of study, investigating the musical expression patterns and folkloric significance of this ritual opera. Nevertheless, these studies predominantly emphasize aesthetic and formal aspects of Ban-sian-xi, paying insufficient attention to its role in constructing religious beliefs and reinforcing communal identity. Moreover, there is a lack of systematic research on how digital media has reconfigured Teochew Opera’s function in reinforcing folk beliefs and community cohesion, particularly through the specific case study of Wufu Lian. In summary, current research on Teochew Opera and its Ban-sian-xi exhibits three significant gaps: First, existing studies predominantly concentrate on its historical evolution and artistic characteristics, while overlooking the social functions of Ban-sian-xi as a religious ritual in shaping folk beliefs and reinforcing communal identity. Second, there is a lack of systematic investigation into how digital media influences Teochew Opera’s role in constructing both folk beliefs and community identity. Third, most research treats Teochew Opera and its Ban-sian-xi as broad subjects, resulting in a scarcity of targeted case studies specifically centered on Wufu Lian. Against this backdrop, this research positions Ban-sian-xi as a unique fusion of Teochew folk belief expression and communal identity construction, and addresses the following three interrelated questions:

RQ1: How does the symbolic system of Ban-sian-xi articulate Teochew folk beliefs?

RQ2: What ritual functions does Ban-sian-xi perform in strengthening Teochew collective identity?

RQ3: What new characteristics emerge in Ban-sian-xi as it reconstructs Teochew folk beliefs in digital media contexts?

Terefore, this study adopts Wufu Lian (五福连) as a core case study, focusing intently on its five constituent plays—The Eight Immortals Celebrating Longevity(《八仙庆寿》), Jumping Jia Guan (《跳加冠》), The Fairy Princess Sends a Child (《仙姬送子》), Clearing the Stage (《净棚》), and Reunion in the Capital (《京城会》), to conduct a micro-level, systematic investigation. It employs an integrated theoretical framework that triangulates semiotics (Saussure, 1966; Peirce, 1998), James W. Carey’s (1989) ritual view of communication, and mediatization theory (Hjarvard, 2013; Hepp & Krotz, 2014), a methodological synthesis that addresses critical gaps in existing scholarship. Complementing this theoretical lens, the study deploys a dual-methods approach: textual analysis to decode symbolic meanings of Wufu lian and content analysis of Bilibili platform data to map digital dissemination patterns.

Specifically, through textual analysis, the research delves into the semiotic systems embedded in Wufu Lian. Beyond interpreting its symbolic meanings, the research further interrogates Wufu Lian’s role in forging communal identity and collective memory within Teochew communities—both in the Chaoshan homeland and across global diasporas. Finally, the study explores the characteristics of Wufu Lian’s dissemination on Bilibili (B 站), a platform that has redefined the transmission ecology of Teochew Opera in the digital age. By analyzing 59 Wufu Lian videos (2019–2025) —including metrics such as view counts, bullet comments (danmu弹幕), and user-generated adaptations—the research reveals how digital mediation both expands Wufu Lian’s reach and reshapes its ritual meaning.

Collectively, this study holds threefold significance. Academically, it fills gaps in Teochew Opera scholarship by centering Wufu Lian as a critical site of folk belief and identity construction, rather than a mere “ceremonial opening act.” Theoretically, it contributes to interdisciplinary dialogues across religious, cultural and media studies. In an era of globalization and digital fragmentation, this research ultimately illuminates how traditional performing arts can remain vital carriers of folk beliefs and communal identity, bridging the past and present for Teochew communities worldwide.

2. Theoretical Framework

An integrated theoretical framework is employed to analyze the ritual symbolism and identity-building functions of Ban-sian-xi within digital environments. Firstly, this study draws on semiotics and theatrical semiotics to decode the symbolic meanings embedded in Wufu Lian and their correspondence with Chaoshan folk beliefs; Secondly, applies James W. Carey’s ritual view of communication to interpret the ceremonial significance of Teochew opera and its role in shaping community identity. Finally, utilizes mediatization theory to examine the dissemination characteristics of Wufu Lian on the new media platform Bilibili.

2.1. Semiotics and Theatrical Semiotics Theory

Saussure’s (1966) distinction between the signifier (the perceptible form of a sign) and the signified (its conceptual meaning) provides a analytical framework for examining the religious symbolism inherent in Teochew Opera. This approach is particularly productive for interpreting elements such as libretto, props, and costumes, and for understanding their role in shaping folk beliefs (Reybrouck, 2017; Zhang, 2024; Wang, 2020). For instance, in Wufu Lian, specific colors (e.g., red and gold) and embroidered patterns on costumes function as signifiers of divinity and fortune, with their meanings deeply anchored in local belief systems (Yu, 2021). Similarly, physical props and auditory elements, such as ritual instruments and melodic motifs, serve as signifiers that convey notions of divine presence or spiritual transition to a culturally literate audience (Holywell, 2024). Thus, Saussure’s model facilitates a systematic semiotic decoding of Teochew Opera, revealing its dual function as both a form of artistic expression and a dynamic medium for transmitting religious meaning and constructing folk beliefs. Within this framework, the visual, auditory, and textual components of Wufu Lian can be analyzed as signifiers that activate shared Chaoshan folk beliefs (the signified).

Peirce’s (1998) classification of signs into icons, indexes, and symbols offers a refined framework for interpreting how Wufu Lian generates religious meaning through distinct modes of signification. Icons, which exhibit a physical resemblance to the signified, include visual or auditory elements such as gestures imitating deity movements or vocal patterns evoking ceremonial chants, thereby creating a sense of immediate supernatural presence (Santaella, 2015). Indexes, operating through contextual or causal connections, comprise elements like drums and gongs that mark ritual transitions, or lighting and smoke suggesting otherworldly atmospheres guiding attention to shifts in ceremonial context (Nabila & Sakinah, 2022). Symbols, grounded in cultural convention, involve objects such as the Ruyi 如意sceptre or costume colours like red and gold, which convey abstract concepts—including power, blessing, and immortality—within Chaoshan folk belief systems. Guided by Peirce’s triad, this study examines the iconic, indexical, and symbolic dimensions across each play of Wufu Lian, elucidating their representative meanings and their role in reinforcing Chaoshan religious and folk beliefs.

Finally, the semiotics of drama, which emerged in the 1980s, provides a refined and systematic framework for analyzing the sign systems within Wufu Lian. Martin Esslin, in his work The Field of Drama (1987), proposed a comprehensive theatrical semiotic system that examines the structural principles and meaning-making mechanisms of dramatic signs from both synchronic and diachronic perspectives (De Corte, 1988). Esslin categorizes the sign systems of drama into five groups: (1) the extra-scenic frame system; (2) the actor-driven sign system; (3) the visual sign system; (4) the textual system; and (5) the auditory sign system. Guided by this framework, this study focuses specifically on the following sign systems within Wufu Lian: the textual system, through analysis of libretto and lyrical content; the actor-driven sign system, by examining ritual props handled by performers; and the visual sign system, via interpretation of costumes, especially their color symbolism and embroidered patterns.

Together, semiotic and theatrical semiotic theories facilitate a holistic analysis of Ban-sian-xi, elucidating its capacity to convey religious meanings and sustain the folk beliefs of the Chaoshan community.

2.2. Ritual View of Communication of James W. Carey

James W. Carey’s ritual view (1989) of communication offers a profound theoretical perspective through which to examine how Ban-sian-si , particularly as embodied in Wufu Lian, contributes to the sustenance of communal identity and the reinforcement of shared memory within the Chaoshan community. In contrast to a transmission model of communication focused on the conveyance of information, Carey emphasizes communication as a symbolic process that constructs and maintains shared beliefs, values, and social solidarity over time (Midtgarden, 2021). Within this framework, Wufu Lian is understood not simply as theatrical entertainment but as a culturally embedded ritual—reenacted during festivals, temple ceremonies that reinforces collective memory, values, and social cohesion among Teochew communities. Through its ritualized narratives, dialect lyrics, music, and gestures, the performance becomes a medium of symbolic communion that renews a sense of belonging and cultural continuity (Kotnik, 2016). Particularly in diasporic or modernized contexts, these performances function as acts of identity preservation, enabling participants to collectively reaffirm their distinct heritage. Thus, Carey’s model illuminates the mechanisms by which Wufu Lian operates as an enduring vehicle for communicative ritual, and constructing Chaoshan community identity.

2.3. Mediatization Theory

Finally, this study employs mediatization theory to investigate how digital platforms reconfigure the dissemination mechanisms and cultural significance of Ban-sian-si. As defined by Krotz (2007), mediatization refers to “the historical developments that took and take place as a change of communication media and its consequences—not only with the rise of new forms of media but also with changes in the meaning of media in general”. This conceptualization emphasizes that media logics—encompassing algorithmic curation, interactive design, and technical infrastructures—exert an increasingly formative influence on the production, distribution, and reception of cultural practices, reshaping how communities engage with traditional heritage. Complementing Krotz’s framework, Hepp and Hjarvard (2013) further posit that media are not neutral conduits for communication but active agents that reshape social institutions, cultural rituals, and modes of meaning-making over time. Their perspective highlights that digital platforms do not merely transmit Ban-sian-si but actively reframe its ritual function, audience relationships, and identity-building potential—transformations central to understanding its contemporary vitality.

Together, these mediated transformations demonstrate how digital mediatization reshapes Wufu Lian’s ritual symbolism, audience engagement, and identity-building functions.

By integrating semiotics, James W. Carey’s (1989) ritual view of communication, and mediatization theory, this research establishes a coherent, multi-layered analytical framework. Semiotics (Saussure, 1966; Peirce, 1998) decodes the structure of Ban-sian-si’s ritual meaning. Carey’s ritual view clarifies Ban-sian-si’s socio-cultural functions, framing its performances as “symbolic communion” that strengthens communal identity. Mediatization theory, in turn, illuminates the transformative impact of digital technology—revealing how Bilibili’s logics reshape Ban-sian-si’s practice and significance, from ritual space to audience interaction. This integrated framework offers a holistic understanding of how Ban-sian-si negotiates tradition and modernity in the digital age.

3. Methods

This study employs an integrated approach combining textual analysis and content analysis to examine the symbolic meanings, folk beliefs construction, identity formation, and digital dissemination characteristics of Wufu Lian on digital media platforms. The textual analysis primarily addresses RQ1and RQ2, focusing on symbolic systems and religious meaning and community identiy constuction; while the content analysis investigates communication features of Chao opera on new media platform Bilibili, corresponding to RQ3.

3.1. Textual Analysis

Textual analysis was conducted to interpret the symbolic structures embedded in the libretto, costumes, and props of Wufu Lian, aiming to uncover how these elements contribute to the construction of folk beliefs and the reinforcement of communal identity within Chaoshan culture. Materials including libretti, costume descriptions, and prop references of five plays, gathered from a various range of archival sources, such as Collection of Teochew Opera Musical Materials 《潮剧音乐资料汇编(共7册)》[1]and academic journals on Teochew Opera, official government publications of Guangdong, like《潮剧册》(Teochew Opera Songbooks)[2], and digital archives maintained by institutions like the Guangdong Teochew Opera Theatre[3].

3.2. Content Analysis

A content analysis was carried out utilizing the DiVoMiner (

https://www.divominer.com/en) platform[4], a specialized tool for quantitative content analysis and data mining. This approach was employed to examine the symbolic, ritual, and communicative aspects of

Wufu Lian within digital environments, with particular attention to its presence on Bilibili, a prominent Chinese video platform recognized for its strong engagement with youth and ACG (animation, comics, and games) subcultures. The research the following steps: (Wilson, 2016),

3.2.1. Sample Selection

To ensure representativeness, this study retrieved videos from Bilibili (

https://www.bilibili.com/) using the keywords "五福连" (Wufu Lian) and "潮剧" (Teochew Opera). The earliest upload of

Wufu Lian was identified in 2019 on Bilibili. And as of the cutoff date for this research, the initial search yielded 95 videos. After excluding those only tagged as “Chaozhou Opera潮剧” but not directly related to

Wufu Lian or its five segments, 59 valid samples were retained.

3.2.2. Database construction

Then, a manually constructed Excel database was developed to systematically store and manage the collected video data. It recorded thirteen key variables, including video title, duration, upload time, annual upload frequency, total views, coin count, favorites, likes, shares, video tags, and comment content, to facilitate subsequent analyses.

3.2.3. Category Coding

Building upon previous research on Peking Opera dissemination on Twitter (Gao et al., 2025) and Chaozhou Opera in new media environments (Huang et al., 2023), incorporating the distinctive features of Bilibili, a comprehensive coding scheme was developed. The resulting codebook is structured as follows:

Table 1.

Codebook for content analysis of Wufu lian videos on Bilibili.

Table 1.

Codebook for content analysis of Wufu lian videos on Bilibili.

| First-level indicators |

Secondary indicators |

| Communication effect |

Views Count

Likes Count

Reposts Count

Comments Count

Favorites Count

Bullet comments Count |

| Time variation characteristics |

Upload time distribution

View count over time

Interaction counts over time

Annual fluctuations

Influence of holiday events |

| Content Features |

(1) Completeness of opera performance

(2) Expression of auspicious meanings

(3) Elaborate character appearances

(4) Characteristics of Chaoshan music and singing styles

(5) Use of Chaoshan dialect |

| Communication characteristics |

Diversity of content and formats

Innovative interactive methods

Use of Chaoshan cultural symbols

Modernization of traditional elements

Bilibili community participation

|

| Construction of folk beliefs |

Re-enactment of traditional Chaoshan rituals

Interpretation of Chaoshan religious symbols

Identity with Chaoshan local culture

Expression of sacredness

Reflection of intergenerational inheritance

|

| Community identity building |

Reawakening of collective memory

Strengthening of Chaoshan identity

Generation of emotional resonance

Maintenance of Chaoshan cultural boundaries

Formation of participatory Chaoshan culture

|

| Collective memory association |

(1) Re-enactment of historical events

(2) Demonstration of traditional skills

(3) Use of nostalgic elements

(4) Expression of Chaoshan collective emotions

(5) Demonstration of the continuity of Chaoshan culture

|

| User interaction features |

Comment sentiment

Depth of interaction

User-generated content

Community discussion intensity

Chaoshan cultural sharing

|

| Chaoshan Cultural propagation |

Innovation in traditional Chaozhou opera art

Acceptance by young audiences

Strengthening of Chaozhou-Shantou cultural identity

Dissemination of Chaozhou-Shantou regional culture

Dissemination of Chaozhou-Shantou culture overseas |

3.2.4. Reliability Test

To ensure the credibility of the sample, the collected data were coded and analyzed using Divominer. Prior to formal coding, a preliminary coding trial was conducted on 30 randomly selected samples to validate the coding scheme. To enhance scientific rigor, two coders independently coded an additional set of 30 randomly selected samples. Inter-coder reliability, assessed using Scott’s pi via Divominer, yielded a value of 0.80, indicating a satisfactory level of agreement and supporting the feasibility of proceeding with full-sample coding.

3.2.4. Content and Textual Analysis

Finally, content and textual analyses were performed using DiVoMiner, structured around two core modules: quantitative indicator analysis and textual content analysis, following established methodological frameworks (Creswell, 2014; de Brito Silva et al., 2022; Shen, 2024).

The quantitative analysis assessed key video metrics, such as release date, view count, shares, coins count (a Bilibili specific reward mechanism), and comment frequency, to map dissemination trends and evaluate audience engagement.

The textual analysis concentrated on video tags and user comments, utilizing techniques including word clouds, keyword extraction, and LDA topic modeling and sentiment analysis to examine the digital dissemination of Ban-sian-xi and Teochew Opera on Bilibili.

4. Analysis of Symbolic System of Wufu lian

As a unique ritualistic theatrical form in the Teochew region, Teochew Opera’s Ban-xian-si performance constitutes a complex semiotic system through its artistic expressions. From the homophonic rhythms of lyrics to the patterns and colors of costumes, from the shapes and functions of props to the stylized movements of gestures, each element serves as a "signifier" carrying auspicious meanings and ritual codes. Intertwining and collaborating with each other, these elements construct a complete "semiotic ritual system". Ferdinand de Saussure’s distinction between "signifier" (the material form) and "signified" (the conceptual meaning) illuminates how divine figures and material objects in these rituals function as arbitrary yet socially agreed-upon symbols. Meanwhile, Charles Peirce’s triadic model, dividing signs into icons (resembling their referents), indexes (causally linked to their objects), and symbols (grounded in convention), reveals the multi-layered ways Ban-sian-si 戏communicates sacred meaning. Together, these theories help decode how Ban-xian-si constructs a shared symbolic order that bridges the mundane and the divine, serving as both a ritual language and a repository of Teochew ritual values.

The following analysis will decode and interpret the symbolic meanings of these "icon-index-symbol" manifestations, namely lyrics, and propsand rituals, to study the semiotic ritual system and its symbolic significance in Wufu Lian (五福连) performance.

4.1. Linguistic Symbols

Lyrics of Wufu Lian performance form a symbolic system through dialect homophony and rhythmic cadence of Teochew region. In The Eight Immortals Celebrate Longevity (《八仙庆寿》, the line "Gourd adds fortune and longevity" (葫芦添福寿) uses the Teochew dialect homophony of "hu lu" (gourd葫芦) and "fu lu”, (fortune-prosperity福禄) to form an index, causally linking the prop to blessing meanings. And the reduplicated phrase "abundant fortunes" (福福满满) reinforces the community’s desire for prosperity through repetition. In Fairy Maiden Delivers a Child (《仙姬送子》, the lyric "Lotus blooms, noble son arrives" (莲开贵子来) uses "lotus" (莲lian ) homophonic with "continuous" (连, index) in dialect, implying "continuous births", aligning with Teochew’s "more children, more blessings" view. The slow rhythm (symbol) renders the ritual solemn. In Gathering in the Capita (《京城会》), "Topping the exam, returning to honor ancestors" (金榜题名时, 光宗耀祖归) features "honoring ancestors" directly echoing Teochew’s clan honor values, with parallelism (index) resembling classical prose to elevate text "sacredness". The incantatory lyrics in Cleaning the Stage《净棚》"Evils disperse, sacred realm tranquilizes" (邪魔皆退散,圣境自安宁) use imperative tone (index) to strengthen "exorcism" efficacy, while "sacred realm" constructs the ritual space’s sacredness.

4.2. Prop Symbols

Props in Wufu Lian construct symbolic meanings through formal resemblance and cultural relevance (Luan, 2023). In The Eight Immortals Celebrate Longevity (《八仙庆寿》) Lü Dongbin’s (吕洞宾) sword, resembling Taoist ritual implements, symbolizes "severing earthly ties" and serves as a "home-protecting amulet" (index) in Teochew folk culture. Tieguai Li’s (铁拐李) gourd (icon), homophonic with "fortune and prosperity" (index) in Chaoshan dialect, becomes a dual symbol of wealth and health. The lotus prop in Fairy Maiden Delivers a Child 《仙姬送子》(icon), resembling the symbol of Taoist pure land, connects to the custom of lotus cakes in Teochew’s coming-of-age ritual (出花园), signifying "pure new life".

The mask "Jia Guan" in Tiaojiaguan (《跳加官》) (symbol) conveys "joy" through a smiling face, while the held tablet (朝笏, icon), mimicking official ritual objects, enhances "blessing authority". The Zhuangyuan hat (状元帽, symbol) and folding fan (折扇, index) in Gathering in the Capital (《京城会》) represent academic success, with the fan’s opening or closing echoing the gentle image of Teochew scholars. The Lingguan’s golden whip (金鞭) in Cleaning the Stage《净棚》embling a torture instrument, symbolizes "punishing evil" (惩恶扬善) and aligns with the function of "exorcism" (驱魔) props in local temple fairs.

4.3. Costume Symbols

As a visual symbolic system, costumes in Wufu Lian distinguish sacred from secular and identify divine attributes. (Zeng, 2023). In The Eight Immortals Celebrate Longevity, the immortals Taoist robes embroidered with Eight Trigrams (八卦) patterns (icon) directly reflect Taoist cosmology, while the flowing water sleeves (水袖, icon) metaphorically represent the divine trait of "wandering the celestial realm". In Fairy Maiden Delivers a Child, the fairy maiden’s phoenix crown and robe (凤冠霞帔) with phoenix embroidery (symbol) signify auspiciousness吉祥, and the red (index) connects to Chaoshan’s color traditions in weddings and birthdays. The Heavenly Official’s red python robe in Gathering in the Capital is embroidered with dragon patterns (symbol), divine authority and aligning with local "red as auspicious" customs. And the Zhuangyuan’s official robe in Gathering in the Capital uses purple (symbol) to imply "auspicious qi from the east" (紫气东来) with bird patterns on the rank badge (icon) indicating academic status. The Lingguan’s (灵官) black facial makeup and golden armor (index) in Cleaning the Stage, enhance the dignity of "warding off evil" (镇煞驱邪) through visual contrast, while the reflective scales of the armor (铠甲鳞片, icon) metaphorically represent "invincibility" (刀枪不入) , the divine power.

4.4. Summary of the Symbolic System in Wufu Lian

Wufu Lian constructs a complete symbolic system through the synergy of three types of symbols:linguistic, prop, costume, centrally embodying the core logic of "utilitarian faith" and "communal identity" of Teochew culture (Lin, 1992; Xu, 2012). From a semiotic perspective, these elements precisely correspond to Peirce’s triadic structure of "icon-index-symbol": Bagua (八卦) patterned robes and lotus props serve as icons through formal resemblance, directly linking to Taoist sacred imagery. Teochew dialect homophonies "gourd-fortune and prosperity葫芦—招财进宝" "lotus-continuous莲花—连续" and associations between red costumes and festive occasions function as indexes, strengthening blessing meanings through causal connections. The Eight Immortals’ images and "fortune, prosperity, longevity" recitations act as symbols, carrying profound ritual values based on communal consensus.

The following table is a summary and comparison of the core symbols of each play of Wufu Lian:

Table 2.

Summary of Core Symbols of Wufu Lian.

Table 2.

Summary of Core Symbols of Wufu Lian.

| Play |

Divine Symbols |

Costume Symbols |

Prop Symbols |

Linguistic Symbols |

The Eight Immortals Celebrate Longevity

《八仙庆寿》 |

Eight Immortals

八仙

(Lü Dongbin吕洞宾, Han Xiangzi, 韩湘子etc.) |

Taoist robes with Bagua (八卦纹道袍) patterns,

water sleeves (水袖) |

Lü Dongbin’s sword, Tieguai Li’s gourd

吕洞宾,宝剑; 铁拐李,葫芦 |

Dialect homophony "gourd (葫芦hu lu) = fortune and prosperity (福禄 fu lu)", lyrics "Gourd adds fortune and longevity (葫芦添福寿)" |

Fairy Maiden Delivers a Child

《仙姬送子》 |

Fairy Maiden (symbol of fertility)

仙姬 |

Phoenix crown, red robe with phoenix embroidery

(凤冠、凤凰刺绣红袍) |

Lotus prop

(莲花) |

Dialect homophony "lotus (莲lian) = continuous (连 lian)", lyrics "Lotus blooms, noble son arrives (莲开贵子来)" |

Dancing Official

《跳加官》 |

Heavenly Official (embodiment of fortune, prosperity, longevity 天官 |

Red python robe with dragon patterns

龙纹红蟒袍 |

Jia Guan mask, imperial tablet

(“加官脸” 面具、朝笏) |

No lyrics, only body movements

|

Gathering in the Capita

《京城会》 |

Zhuangyuan (top scholar, symbol of academic success)

状元 |

Purple official robe with bird-patterned rank badge

禽鸟纹补子紫官袍 |

Zhuangyuan hat, folding fan

(状元帽、折扇) |

Lyrics "Topping the exam, returning to honor ancestors (金榜题名时, 光宗耀祖归) |

Cleaning the Stage

《净棚》 |

Lingguan (Taoist guardian deity, symbol of exorcism)

灵官 |

Black facial makeup,

黑色脸谱

golden armor with reflective scales

反光鳞片金甲 |

Golden whip

(金鞭) |

Incantatory lyrics "Evils disperse, sacred realm tranquilizes (邪魔皆退散, 圣境自安宁) |

5. Analysis of Ritual Significance of Wufu lian

The role of arts in fostering community identity is increasingly recognised within interdisciplinary scholarship (Belfiore & Bennett, 2010; Moran, 2011; Clements, 2016; Ille, 2024). As a performative art form, opera embodies a dual nature: the imitative and the ritual (Schechner, 1994; Zhou, 2003). Richard Schechner’s (1994) performance theory offers a foundational framework for this conceptual dichotomy, distinguishing between efficacious rituals, which aim to produce real-world outcomes, and entertainment performances, which focus on mimetic representation. Schechner (1994) observes that the mimetic dimension prioritises the theatrical enactment of narrative content. In contrast, the ritual function interprets performance not merely as storytelling, but as a form of ceremonial action that reinforces social cohesion through collective participation, shared experience, and the affirmation of communal beliefs (Xu, 2020; Li, 2020; Schechner, 2003). This aligns with James W. Carey’s “ritual view of communication”. Carey (1989) contends that communication is fundamentally a socio-cultural ritual, constituted through dynamic interactions between symbols and their meanings, effectively serving as a sacred ceremony that gathers individuals into a community united by shared identity. Such rituals facilitate the construction of collective belief systems, enabling participants to affirm their core sense of self and belonging.

Within Teochew communities, Chao Opera exemplifies this integrative nature. It is not merely a folk art; it functions as both entertainment and sacred practice, deeply embedded in religious ceremonies, ancestral veneration, and communal festivities (Tan, 2018; Huang & Lin, 2021). Through its performative narratives, musical traditions, and ritual enactments, it enhances social cohesion and fosters a shared sense of belonging, making a substantial contribution to the sustenance of Teochew cultural identity in contemporary society (Wang, 2019). Ultimately, Chao Opera serves to preserve communal memory and reinforce the collective identity of the Chaoshan community, embodying a fusion of artistic expression and socio-religious practice that strengthens cross-region bonds and a continuous sense of belonging.

The subsequent analysis will examine the ritual significance of the five constituent plays within Wufu Lian, aiming to elucidate their role in constructing collective memory and reinforcing identity within the Chaoshan community.

5.1. Eight Immortals Celebrate Longevity 《八仙庆寿》

Eight Immortals Celebrating Longevity adapted from The Peach Banquet (《蟠桃会》), depicts Dongfang Shuo 东方朔inviting the Eight Immortals to celebrate the birthday of the Queen Mother of the West (西王母). The performance symbolizes "longevity" (Zhang, 2024).

5.1.1. Ritual significance of Eight Immortals Celebrating Longevity《八仙庆寿》

Table 3.

Summary of Ritual significance of Eight Immortals Celebrating Longevity.

Table 3.

Summary of Ritual significance of Eight Immortals Celebrating Longevity.

| Dimension of Meaning |

Key Manifestations |

| Ritual Function |

Inviting divine presence (请神); offering tributes (颂神); sanctifying the performance space. |

Communal

Identity

Function

|

Collective blessings

for the community; transmission of filial piety; mnemonic anchor for diasporic cultural identity. |

5.1.2. Significance for Communal Identity Construction

Connecting with Overseas Communities

Eight Immortals Celebrating Longevity through the ritual of "presenting birthday felicitations" (献寿), it establishes a thematic framework that subordinates subsequent blessings: such as "bestowing offspring" (送子), "conferring official titles" (加冠), and "familial reunion" (团圆) under the grand Confucian virtue of "health and longevity" (健康长寿). This narrative structure imbues the performance with a closed-loop symbolism, reflecting the Chaoshan cultural ideal of "completion" (圆满) and embodying the community’s emphasis on holistic well-being and cosmic harmony (Xu, 2020). On a communal level, it serves as a vital cultural practice that reinforces collective identity. Traditionally performed for the benefit of the entire village or clan, it fosters community cohesion and transmits the ethic of filial piety. For the global Teochew diaspora, Eight Immortals Celebrating Longevity has long been a staple in the Teochew opera performances dedicated to religious offerings 酬神戏in Singapore and Thailan (Zhang, 2009). It serves as a crucial link connecting the Chaoshan region with its Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. As a performative ritual deeply embedded in Teochew opera tradition, Wufu Lian transcends geographical boundaries and temporal distances, facilitating a continuous exchange of symbolic meanings, religious values, and collective memories among dispersed populations. Its performance—whether staged in ancestral villages in Chaoshan or recreated in Malaysian temple festivals, Thai cultural associations, or Singaporean community gatherings—acts as a reaffirmation of shared identity rooted in Teochew culture.

Therefor, the significance of Wufu Lian in constructing communal memory and reinforcing group identity cannot be overstated (Zeng, 2025). Through its narrativized rituals, it translates abstract spiritual concepts into tangible collective practice. Each performance re-enacts a shared heritage, allowing participants to engage not only as spectators but as co-creators of cultural continuity.

5.2. Fairy Maiden Delivers a Child《仙姬送子》

Fairy Maiden Delivers a Child originates from a segment of The Legend of the Heavenly Fairy and the Mortal (《天仙配》), in which the Seventh Fairy (七仙女) send a son to Dong Yong (董永). The whole play has only four lines of dialogue, and due to the Chinese folk concept hat "having a child is a blessing多子多福", it implies "progeny" of five blessings (Zhang, 2024).

5.2.1. Ritual Significance of Fairy Maiden Delivers a Child《仙姬送子》

Table 4.

Summary of ritual significance of Fairy Princess Sends a Son《仙姬送子》.

Table 4.

Summary of ritual significance of Fairy Princess Sends a Son《仙姬送子》.

| Dimension |

Key Manifestations |

| Ritual Function |

The Celestial Maiden (七仙女), acting as a divine emissary under the Jade Emperor’s decree; the ritualized presentation of the "Prince Doll" figurine (太子爷) to the audience; the segment’s fixed position within the Wufu Lian sequence, following longevity prayers and preceding petitions for rank and wealth. |

| Communal Identity Function |

Performances are sponsored by the clan or village for collective benefit, not individual families; for the overseas Teochew diaspora, the ritual evokes powerful nostalgia and reinforces identity, serving as a "root seeking" practice. |

5.2.2. Significance for Communal Identity Construction

Continuity and Clan Perpetuation

Once longevity is ecured after Eight Immortals Celebrating Longevity, the natural subsequent hope is for the continuation and propagation of life. The Fairy Princess Sends a Son (《仙姬送子》) directly responds to this expectation, completing the thematic transition from "praying for the longevity of the individual" to "praying for the perpetuation of the family lineage." Ritually, it constitutes a sacred moment of divine–human interaction, physically delivering the symbol of a "heaven-sent son "天姬送子into the mortal world.

And the symbolism of this act is deeply anchored in its narrative, the Celestial Maiden (仙女), acting under the Jade Emperor’s (玉皇大帝) decree, presents a son to Dong Yong, a figure renowned for his virtue and filial piety (贤孝). This act is not simply an allegory of reproduction but represents a divine reward and endowment for moral excellence. During the performance, an actor presents a "Prince Doll" (太子爷), a figurine representing a child, to the audience, where it is received by the host family or spectators (Liang, 2020). This ritual symbolizes the tangible bestowal of divine grace upon a family or community, completing a sacred exchange between humans and deities, elevating the act to a transcendental ritual event, engaging with core values of traditional Chaoshan, such as "having many sons and much happiness" (多子多福). As a communal practice, it addresses the needs of the clan collective, reinforceing the identity of Teochew people both domestically and overseas, and embodies the fundamental ideal of "continuing the ancestral line" (续香火).

This perspective aligns with religious anthropological perspectives (e.g., Watson, 1985) that frame folk rituals as “social glue” for kinship-based communities, where symbolic performance and material practice converge to sustain clan and identity.

In this sense, when the clan members of Chaoshan gather to watch The Fairy Princess Sends a Child, the play’s narrative of immortal-bestowed offspring is not mere symbolism but a collective prayer for “continuing the ancestral line”: elders often remark that the performance “blesses the clan with more healthy boys to carry on the family name,” while younger couples participate in ritual offerings (e.g., placing red envelopes at the stage edge) to align their personal desires with the clan’s collective goal of lineage perpetuation (Liang, 2019; Wang, 2021). In sum, The Fairy Princess Sends a Child as a communal practice does more than “address clan needs” or “reinforce identity”—it weaves the individual, the clan, and the whole transnational Teochew community into a single fabric, bound by the shared ideal of “continuing the ancestral line.” By grounding this ideal in repeated, sensory-rich ritual, it ensures that Chaoshan clan identity and common memory are not just preserved, but actively lived—generation after generation, at home and abroad.

5.3. Tiao Jiaguan 《跳加官》

Tiao Jiaguan《跳加官》 constitutes a special play within the WufuLian. Uniquely, it is performed without libretto, conveying its meaning entirely through stylized movement, gesture, and musical accompaniment. It can be performed independently on auspicious occasions or integrated as a component of Wufu Lian sequence. In its absence, the performance is renamed Sifu Lian四福联(Four Fortunes). In Tiao Jiaguan, the term Jiaguan means adding the crown, symbolically means attaining official rank. The performer, wearing a "official hat mask" (加冠壳) and holding a ceremonial jade tablet (玉笏), embodies the appearance of a Heavenly Official (Tianguan天官), though some identify the figure as the God of Wealth of China 财神爷Zhao Gongming赵公明 (Liao, 2021). This act constitutes the core ritual segment within Wufu Lian for the blessing of official position and salary禄.

5.3.1. Ritual Significance of Tiao Jiaguan 《跳加官》

Table 5.

Summary of ritual significance of Tiao Jiaguan 《跳加官》.

Table 5.

Summary of ritual significance of Tiao Jiaguan 《跳加官》.

| Dimension of Meaning |

Key Manifestations |

| Ritual Function |

A wordless, masked pantomime; the ceremonial unfurling of scrolls bearing auspicious phrases like "加官晋爵" (Promotion to higher office and rank); the ritualized presentation of these blessings towards the audience or specific patrons. |

Communal

Identity

Function

|

The dancer’s costume (official’s robe and hat (加冠壳) symbolizes imperial bureaucracy; the scrolls function as potent textual talismans; the performance is a kinetic symbol of career advancement and familial honor. |

5.3.2. Significance for Communal Identity Construction

Tiao Jiaguan (《跳加官》) symbolizes the essential blessings of rank (禄) and wealth (财), thereby completing the narrative logic of the Wufu Lian sequence. It vividly portrays the tangible rewards of a virtuous life: scholarly achievement is met with official promotion, which in turn brings prosperity and enhances family honor. This narrative offers a ritually and emotionally fulfilling conclusion, reinforcing the shared worldview and aspirations of the Chaoshan community. Ultimately, Tiao Jiaguan 跳加冠 functions not simply as a theatrical performance but as a ritual act of investiture, translating the divine favor of the Heavenly Official (天官) into the earthly pursuit and attainment of official rank禄.

For Chaoshan communities, Tiao Jiaguan’s portrayal of “rank (禄)” and “wealth (财)” is deeply intertwined with the clan’s foundational pursuit of intergenerational prosperity and social legitimacy—key pillars of community construction. In traditional Chaoshan society, “禄” (official rank) was not merely an individual achievement but a clan-wide triumph: a scholar’s success in imperial examinations and subsequent official appointment elevated the entire clan’s status, granting access to social resources, political influence, and ancestral honor (Lin, 2015). In rural Chaozhou clan halls, Tiao Jiaguan ritual takes on even greater communal significance: during Lunar New Year gatherings, clan elders often select promising young scholars to receive the “gold ingots” from the performer, framing the act as a “divine blessing” for the clan’s future success. This practice embeds Tiao Jiaguan into the community’s structural fabric—turning abstract values of “禄” and “财” into shared goals that unite clan members across ages, strengthening the sense of collective memory that underpins community stability (Liang, 2019; Wang, 2021).

5.4. Cleaning the Stage《净棚》

Cleaning the Stage, also known as The Emperor Tang Ming Huang Cleaning the Stage (《唐明皇净棚》), is a foundational ritual segment in which the actor embodying Emperor Minghuang 唐明皇, recites only four lines of lyrics, while performing a series of stylized movements toward the four cardinal directions of the stage (Zheng, 2010). Within the ritual framework of the Wufu Lian, Cleaning the Stage does not directly correspond to any one of the "Five Fortunes". But it serves as the essential precondition for the entire performance sequence. It ensures the progression of the subsequent performances, establishing the sacred foundation necessary for the blessings of five fortunes to be invoked and received. And the lyrics delivered by the Emperor Tang Minghuang (唐明皇) carry the meaning of "subduing malevolent forces" (震慑恶煞) and "purifying the performance space" (肃清戏台) (Chen, 1997).

5.4.1. Rutial Significance of Cleaning the Stage 《净棚》

Table 6.

Summary of the Rutial Significance of Cleaning the Stage 《净棚》.

Table 6.

Summary of the Rutial Significance of Cleaning the Stage 《净棚》.

| Dimension |

Key Manifestations |

| Ritual Function |

Spatial Purification: Expels malevolent forces and impurities through invocations, gestures, and horn blasts sound 号角.

Cosmic Demarcation: Stylized movements toward the four directions (踏四角) establish a ritually bounded microcosm.

Divine Invitation: Invites deities to witness the performance, lending divine authority to the subsequent blessings. |

Communal Identity

Function

|

Public Affirmation of Beliefs: Public performance reaffirms the community’s commitment to traditional spiritual practices;

Serves as a practice for overseas Teochew people to preserve cultural memory,

enacting the folk belief: "no worship without purification" (不净不拜) |

5.4.2. Significance for Communal Identity Construction

Spatial Purification and Sacred Initiation

Cleaning the Stage《净棚》 serves as the ritual foundation of Wufu Lian, although it does not directly represent any of the "Five Fortunes五福," it is the essential precondition that enables the entire ritual drama to unfold with efficacy and legitimacy. This segment performs a purification rite aimed at cleansing the performance space of negative influences and inviting divine presence (驱邪祈福), thereby constructing a consecrated, protected, and spiritually endorsed environment. It eliminates impurities through spatial purification, establishes a sacred field for communication between humans and deities, and embodies the Chaoshan folk belief of "no worship without purification不净不拜". Through this ritual, the Teochew community does not merely perform a play but actively reaffirms its cosmology, social values, and unique cultural identity.

Therefore, unlike more “visible” Wufu Lian segments focused on blessings like “rank” or “progeny,” Cleaning the Stage’s power lies in its quiet, foundational role: it creates the “sacred ground” upon which the community’s collective identity is built. Whether performed in a rural Chaozhou clan hall, a Singaporean diasporic temple, Cleaning the Stage reminds every Chaoshan person: they are part of a community bound not just by blood or geography, but by the shared ritual of “purifying the space—and the memory”. Its ability to turn abstract “ritual order” into tangible practice—linking every community member to shared beliefs, historical experiences, and a sense of belonging. This aligns with religious anthropologist Victor Turner’s (1969) concept of “liminal ritual,” where acts of purification create a “sacred middle ground” that unites participants in a shared state of collective consciousness, reinforcing their communal identity.

5.5. Reunion in the Capital 《京城会》

Reunion in the Capital is selected from an excerpt of The Story of the Painted Tower (《彩楼记》), showing the scene where the the impoverished scholar Lü Mengzheng, after enduring hardship, achieves the highest rank(状元) in the imperial examinations of China and is reunited with his wife, Liu Yuezhen in the capital. Its meaning transcends narrative conclusion, serving as the ritual culmination of the suite’s blessings, embodying the meaning of meritocratic success (功名) and represents the wish for a "reunion" of family (团圆) (Zhang, 2024).

5.5.2. Significance for communal identity construction

Academic Glory and Communal Identity

Reunion in the Capital consolidates communal identity through the concept of "townsmen同乡". It completes the "Five Fortunes" by showcasing the rewards of life: Lü Mengzheng’s intellectual merit is rewarded with the highest imperial honor, while his wife’s loyalty is rewarded with shared prosperity. This provides a narrative resolution that is satisfying both ritually and emotionally. The play is not merely about individual success but about the validation of the entire family and lineage harmon (圆满). The reunion signifies the restoration and elevation of family honor, making it a powerful expression of core Confucian values within a communal setting (Lin, 2019). Its performance during celebrations projects these aspirations on to the entire community, making it a collective prayer for and celebration of achieved success.

By recreating the glorious scene of imperial examination 科举考试 success, Reunion in the Capital reinforces the Teochew common cultural value of "pursuing official rank through scholarly achievement "(攻读功名) It completes the ideal of Five Fortunes (五福) by dramatizing their tangible rewards: Lü Mengzheng’s intellectual diligence is honored with the highest imperial distinction, while his wife’s loyalty is rewarded with shared prosperity and honor. The play offers a narrative resolution that is both ritually significant and emotionally satisfying ( Lin, 2015). The reunion symbolizes the restoration and enhancement of the family social standing, making the play a powerful expression of core Confucian values of familial harmony (圆满). When performed during communal celebrations, it projects these aspirations onto the whole community, serving as a collective prayer for success and moral fulfillment.

Table 7.

Summary of ritual significance of Reunion in the Capital《京城会》.

Table 7.

Summary of ritual significance of Reunion in the Capital《京城会》.

| Dimension |

Key Manifestations |

| Ritual Function |

Transforms the secular success story (top scholar reunion 状元) into a divine affirmation, showing that worldly achievement is a manifestation of heavenly favor and ancestral virtue.

Its performance during festivals projects the hope for official rank, academic success, and family prosperity onto the entire community. |

Communal Identity

Function

|

Affirms the Chaoshan community’s deep-rooted Confucian values, most notably the ethos of "studying for officialdom" (攻读功名).

The individual triumph indicates "elevation of family honor"(门楣增辉); it is a validation of lineage honor of the whole Chaoshan community. |

5.6. Summary of the Ritual Significance of Wufu lian五福连

The ritual structure of Wufu Lian follow the logical sequence of "prayer–blessing–celebration–completion (祈愿—赐福—欢庆—圆满)" forming an interconnected organic whole. This framework binds its five plays into a meaningful ritual continuum. Firstly, The Eight Immortals Celebrate Longevity embodies the blessing of longevity (寿). Fairy Maiden Delivers a Child focus on the aspirations of clan continuity. Dancing Official opens a channel for divine-human communication to seek blessings for material prosperity (禄). Cleaning the Stage establishes a sacred atmosphere through spatial purification. Finally, Gathering in the Capital represents the culmination of this spiritual pursuit, symbolizing the attainment of scholarly achievement (名) and familial harmony (圆满), thereby completing the entire chain of the Five Fortunes (Wufu五福).

Each play, through its iconic actions, symbols, and ritual process, not only embodies Chaoshan folk belifes, such as “no worship without purification不净不拜,” “utilitarian faith 有求必应,” and “valuing farming and reading for family inheritance重视耕读,以传家业”, but also incorporates the audience into the ritual system through interactive performance, making the entire Wufu Lian a living vehicle for sustaining collective memory and communal identity of Teochew.

The following table summarizes the three core dimensions of Wufu Lian’s ritual significance, emphasizing its role in constructing the folk beliefs system of Teochew people, fulfilling their ritual needs, and sustaining Teochew common identity across its generations and geographic boundaries.

Table 8.

Summary of the Ritual Significance of Wufu lian.

Table 8.

Summary of the Ritual Significance of Wufu lian.

| Dimension |

Significance |

Key Manifestations |

Folk

Belief Construction |

Embodies and materializes the core folk belief concepts of "Five Fortunes 五福" through performative ritualization, transforming abstract blessings into tangible theatrical reality. |

Personifies abstract blessings of Longevity, Rank, Wealth, Progeny, Harmony寿、禄、财、子、团圆)

Dramatizes the principle of “no worship without purification不净不拜”

Visualizes the folk belief in "prayers answered through ritual correctness 有求必应" |

| Ritual Function |

Serves as a complete ritual system that facilitates divine-human communication, ensures efficacy of blessings, and maintains cosmic order through prescribed performative actions. |

Follows the sacred sequence of invitation-blessing-fulfillment;

Incorporates ritual elements: directional movements, symbolic props, and ceremonial music, such as horn号角, drump beats击鼓(Zhang, 2024);

Creates a consecrated and cleaning space for interaction between human and divine realms with a ceremony of cleaning the stage. |

Communal Identity

Function

|

Reinforces Teochew identity by perpetuating shared values, creating collective memory, and maintaining spiritual connections across global diaspora through ritual participation.

|

Performed during community festivals and life-cycle events, such as the Chinese New Year, the Lantern Festival etc (Lin, 2019);

Transmits core values: family continuity, scholarly achievement, and clan prosperity;

Serves as cultural anchor for overseas Teochew communities, such as

Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailan (Yang, 2019; Liang, 2020) through ritual practice. |

6. Analysis of the New Communication Characteristics of Wufu lian on Bilibili

The proliferation of digital media has fundamentally transformed the dissemination landscape of Teochew opere (Huang, 2023; Zheng, 2023; Dong, 2025). The emergence of video - sharing platforms like Bilibili, TikTok, and YouTube offers a compelling solution, creating a new digital ecosystem for the opera’s dissemination. This section explores how the Bilibili platform, leveraging its unique technological features such as algorithm driven content discovery, real - time interaction enabled by danmu (弹幕bullet comments), and on demand accessibility, is shaping the way Teochew opera is shared and consumed in the digital media age.

6.1. Data Collection

6.1.1. Video Screening Process

This study uses Bilibili (

https://www.bilibili.com/), a major Chinese video-sharing platform, as the data source and uses "潮剧Chaozhou Opera" and "五福连Wufu Lian" as keywords for video retrieval.The research time frame covers from 2019 (the earliest year when such videos were uploaded on Bilibili) to 2025 (the cut-off year of the paper’s research).

An initial search collected a total of 95 videos. However, a detailed verification revealed that some of these videos only with the label "潮剧Chaozhou Opera" but actually featured other repertoires of Chaozhou Opera, which were irrelevant to the "Wufu Lian" repertoire or its subordinate individual plays. To ensure data accuracy, these irrelevant videos were excluded, and finally, 59 valid samples were retained, including Wufu Lian repertoire and its individual plays, such as Celebration of the Eight Immortals , The Fairy Sends a Child, and Meeting in the Capital.

6.1.2. Data Storage

To realize the standardized management and subsequent analysis of the 59 valid videos, a self-designed Excel sheet was manually created to build an exclusive database. Thirteen core metrics of each video were recorded: "Title", "Video Duration", "Release Time", "Annual Releases Count", "Total Views", "Coin Count", "Favorite Count", "Like Count", "Share Count", "Video Tags", "Lable Content","Comment Count", and "Comment Content". The establishment of this structured Excel database provides standardized data support for the subsequent content and textual analysis.

6.1.3. Data Analysis Tools and Methods

Subsequently, the sorted and cleaned Excel dataset was imported into DiVoMiner, a professional platform for processing textual data using content analysis methods. The analysis was structured into two interrelated modules: quantitative indicator analysis and textual content analysis, as in previous studies (Creswell, 2014; de Brito Silva et al., 2022; Shen, 2024).

Quantitative Indicator Analysis

Mapping Dissemination Trajectories and Audience Engagement Dynamics

Firstly, quantitative metrics such as video release, total views, sharing count, coin cout[5], and comment count were carried out in a depth analysis to gain a understanding of the videos’ dissemination patterns and audience engagement.

Textual analysis

Decoding potential information in tags and comments

Then, two key text types: video tag content and user comment content were analised, employing a suite of analytical techniques, including Word cloud visualization, Keyword extraction, LAD topic analysis were conducted to excavate the latent cultural, emotional, and cognitive dimensions embedded in the textual data.

In terms of coding variables for content analysis, this study builds on the research of Kozinets et al.’s (2010) by focusing on five variables: (1) (Ritual Anchoring and folk beliefs construction; (2) Collective memory association; (3) Cultural transmission; (4) Diaspora connectivity and community building; (5) Video quality evaluation

6.2. Results and Discussion of Wufu Lian Videos on Bilibili

6.2.1. Data Overview

Table 9.

Data Overview of Wufu Lian videos on Bilibili.

Table 9.

Data Overview of Wufu Lian videos on Bilibili.

| Metric |

Value |

Observations |

| Time Range |

2019- 2025 |

The earliest upload found is from 2019. And the search period is until August of 2025. |

| Play Count Range |

151 - 89,000 |

A significant disparity exists, with most videos having modest view counts. |

| Highest Play Count |

89,000 |

Achieved by "潮剧吉祥戏-《十仙庆寿》修复高清版" (Chaozhou Opera Auspicious Play - Ten Immortals Celebrate Longevity Restored HD Version). |

| Lowest Play Count |

151 |

Achieved by五福连-十仙庆寿 (比例调整, 字幕重制, 图像质量提高至1080P)

(Wufulian Ten Immortals Celebrating Birthday (adjusted scale, remastered subtitles, improved image quality to 1080P) |

| Average Play Count |

~13,650 |

|

The data presents a overview of the presence of Wufu Lian on Bilibili. Overall, the collection of 59 videos, spanning from 2019 to August of 2025, shows a sustained upward trend in publication volume. This indicates Bilibili’s role as a vital digital repository and community hub for Chaozhou Opera.

The viewership metrics reveal a significant disparity in engagement, with an average play count of approximately 13,650, the most notably is "Restored HD Version" of the auspicious play Ten Immortals Celebrate Longevity, which leads with 89,000 plays, while the lowest was only 151, reflecting substantial differences in the popularity of videos, and the vast majority of videos have more modest view counts. This pattern is consistent with typical content platform (Gao, 2024; Zheng, 2024) and underscores the strong appeal of specific classic performances among the Chaoshan diaspora and traditional culture enthusiasts. That said, for audiences less familiar with Chaoshan culture, plays like Wufu Lian may hold limited appeal and struggle to generate broader engagement.

6.2.2. Temporal Distribution of Uploads

Table 10.

Temporal distribution of Wufu Lian videos on Bilibili.

Table 10.

Temporal distribution of Wufu Lian videos on Bilibili.

| Time Period |

Number of Posting |

Trend Description |

| 2019-2021 |

7 |

Initial Phase: Relatively low and stable release volume. |

| 2022-2023 |

31 |

Significant Growth Period: The number of releases began to increase markedly, reaching its first peak (19) in 2023. |

| 2024 |

15 |

Sustained Activity Period: Release volume remained stable but declined. |

| 2025 |

6 |

Partial Year Data: until August of 2025, uploads are ongoing.

(until the study was conducted) |

| Total |

59 |

|

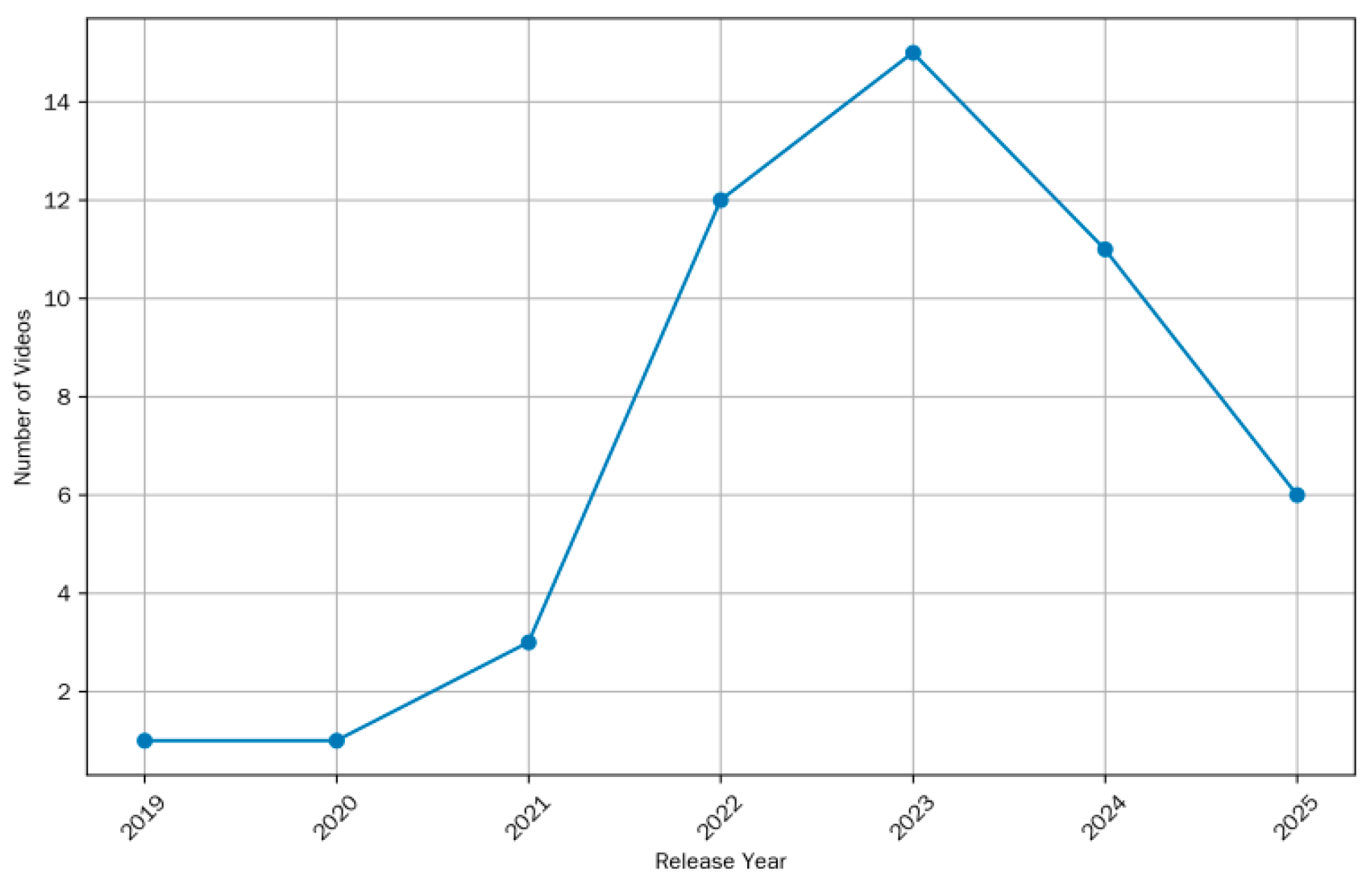

Based on the yearly data, an overall upward trend in the number of video releases can be observed from 2019 to 2023, reflecting growing interest in uploading such content during this period. In terms of specific trends, the period from 2019 to 2021 was characterized by a relatively low and stable release volume, with an average of approximately 3 to 5 videos per year, indicating an initial phase of posting the video of Wufu Lian on Bilibili. From 2022 to 2024, the number of releases began to increase significantly, reaching its first peak in 2023. The decrease in releases in 2025 attributes to the fact that the data collection of this study only extended until August of 2025, the cutoff date for data collection of this study. Therefore, further research should be undertaken in the future to track the dissemination of Teochew Opera on Bilibili.

Figure 1.

Annual Release Trend of Wufu Lian on Bilibili.

Figure 1.

Annual Release Trend of Wufu Lian on Bilibili.

6.2.3. Engagement Metrics analysis

Table 12.

Top 10 Tags of Wufu Lian Videos on Bilibili.

Table 12.

Top 10 Tags of Wufu Lian Videos on Bilibili.

| Rank |

Tag (English) |

Tag (Chinese) |

Count |

| 1 |

Teochew Opera |

潮剧 |

38 |

| 2 |

Chinese Opera |

戏曲 |

32 |

| 3 |

Traditional Culture |

传统文化 |

18 |

| 4 |

Chinese Traditional Opera |

中国戏曲 |

14 |

| 5 |

Local Opera |

地方戏 |

9 |

| 6 |

Ten Immortals’ Birthday |

十仙庆寿 |

7 |

| 7 |

Five Blessings (Wulian) |

五福连 |

6 |

| 8 |

Spring Festival |

春节 |

5 |

| 9 |

Capital Meeting (Jingchenghui) |

京城会 |

4 |

| 10 |

Chaoshan (region) |

潮汕 |

4 |

Table 12.

Wufulian’s Engagement Metrics.

Table 12.

Wufulian’s Engagement Metrics.

| Metric |

Analysis |

| Play Count |

Extreme variance. The top few videos attract the vast majority of views. |

| Coins, Favorites, Likes, Shares |

High correlation with play count. The most viewed video is also the most engaged-with, suggesting content quality and cultural significance drive interaction. |

| Comments |

Comment counts vary but are notably high on popular videos , for example, 94 comments on the top video. |

The play count reflects substantial differences in the popularity of various videos. The top few videos attract the vast majority of views. Then we conducted a further analysis of these videos, and found that videos uploaded by creators with a large number of followers typically achieve higher view counts. In contrast, videos published by less-followed creators or performed by youth troupes, such as the Guangdong Xiaolihua Youth Teochew Opera Troupe (广东小梨花青年潮剧团), with only 385 views, generally receive lower view counts. This indicates that the influence of the uploader significantly affects the video’s reach. Moreover, audiences show a stronger preference for classic performances, while younger troupes attract relatively less attention.

The coin mechanism is a distinctive feature of Bilibili China, compared to other short video platforms in China (such as TikTok), allowing users to reward high-quality content. However, data shows that even videos with high view counts receive very few coins, suggesting that users generally prefer free viewing and are less willing to pay.

Other metrics, including saves, likes, shares, and comments, also show large differences in means and standard deviations, further highlighting significant variability in engagement across videos. A closer look reveals that the top 10 videos by view count perform noticeably better across these interaction metrics compared to the bottom 10 videos. This aligns with logical expectations, lower view counts typically correlate with reduced secondary dissemination and interaction.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that aside from videos with high view counts, many videos garner relatively few or even zero shares, likes, and favorites. In addition, comment sections of these Wufu Lian videos on Bilibili tend to show low levels of comment activity, indicating that although users watch the content, their willingness to engage in discussions or other forms of interaction remains relatively limited.

This indicates that Teochew Opera and Wufu Lian currently have limited reach and influence beyond the Teochew community. Further efforts are needed to promote the dissemination of this regional opera, both within China and among international audiences, in order to enhance its reach and preserve its cultural significance.

6.2.3. Tags Analysis

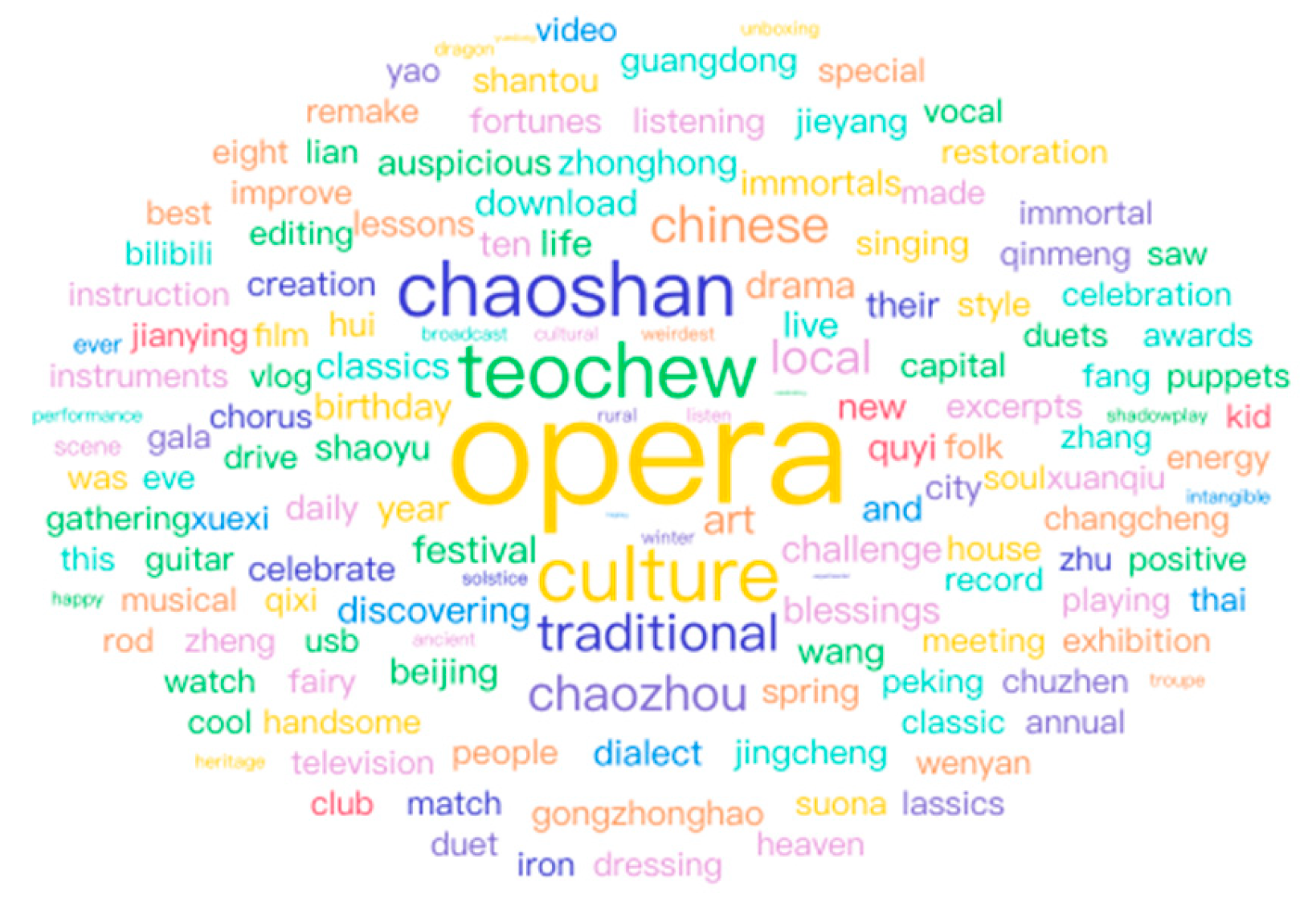

Figure 2.

Tags Word Cloud of Wufu Lian Videos on Bilibili.

Figure 2.

Tags Word Cloud of Wufu Lian Videos on Bilibili.

The Top 10 frequency tags of Wufu Lian videos , are Teochew Opera (潮剧), Traditional Culture (传统文化), and Local Opera (地方戏), etc, effectively categorize the content within broad cultural and artistic genres.

The Spring Festival 春节, emerged as a frecunt keyword among video tags. When examined in conjunction with upload timing, it was observed that videos published during traditional Chinese festivals, particularly the Spring Festival 春节and the Lantern Festival元宵节consistently garnered higher view counts. This pattern underscores the strong thematic relevance between the content and these cultural celebrations. This phenomenon can be largely attributed to the traditional Teochew custom of conducting deity worship ceremonies 拜神 during the Spring Festival, wherein performances such as Wufu Lian are ceremonially broadcasted. Thus, the elevated viewership during these periods reflects not only seasonal interest but also deeply rooted ritual practices.

These findings further illuminate the integral relationship between Teochew Opera’s Ban-sian-Xi and the construction of festive customs and folk beliefs within the Chaoshan region. The opera serves as both cultural entertainment and a medium of spiritual and ritual expression, reinforcing its role in sustaining regional identity.

Finally, the prevalence of secondary tags like Ten Immortals’ Birthday and Capital Meeting is significant. This pattern arises because, on Bilibili, alongside full performances of the Wufu lian, individual plays are predominantly from these two specific acts. This prevalence not only reflects their popularity but also underscores a deep-seated cultural value within the Chaoshan community: a profound pursuit of longevity and the celebration of scholarly achievement and official success, which are central themes in these celebrated works.

6.2.5. Coments Analysis

Keywords of Comment

The top 10 keywords of Chinese and English comment content ranked by frequency of appearance are:

Table 13.

Top 10 keywords of Wufu Lian五福连videos on Bilibili.

Table 13.

Top 10 keywords of Wufu Lian五福连videos on Bilibili.

| Rank |

Keyword |

Frequency |

Example Context in Comments |

| 1 |

Worship (拜神) |

28 |

"used for worship", "拜天公必备" |

| 2 |

Thank you |

18 |

"Thank you uploader" "感谢Upper |

| 3 |

Version |

15 |

"old version", "老版本" |

| 4 |

Classic |

12 |

"classic" "经典拜老爷曲目", |

| 5 |

Home |

11 |

"feels like home","家里拜神" |

| 6 |

Auspicious Play

(吉祥戏) |

9 |

"auspicious play" "吉祥戏" |

| 7 |

Childhood |

8 |

"childhood memories", "童年回忆", |

| 8 |

Play |

8 |

"play this", "投屏播放" |

| 9 |

Music |

7 |

"music" ,"配乐好听" |

| 10 |

Chaoshan (潮汕) |

7 |

"Chaoshan people","潮汕人" |

LDA Comment Topic Analysis[6]

Table 14.

LDA Comment Topic of Wufulian Videos on Bilibili.

Table 14.

LDA Comment Topic of Wufulian Videos on Bilibili.

| LDA Topic |

Keywords |

Count |

Theme 1 Opera culture

(0.55) |

支持 (0.0104) 五福 (0.0077) 潮剧 (0.0070) 前排 (0.0067) 庆寿 (0.0064)

Support (0.0104) Five Blessings (0.0077) Teochew Opera (0.0070) Front Row (0.0067) Birthday Celebration (0.0064)

|

18 |

谢谢 (0.0060) 经典 (0.0058) 版本 (0.0056) 感覺 (0.0051)功底 (0.0051)

Thank you (0.0060) Classic (0.0058) Version (0.0056) Feeling (0.0051) Skill (0.0051)

|

| Theme 2 Audiovisual experience (0.24) |

支持 (0.0064) 诡异 (0.0061) 大团 (0.0061) 潮剧 (0.0055)小时候 (0.0054) 好听 (0.0054)

Support (0.0064) Weird (0.0061) Big Group (0.0061) Teochew Opera (0.0055) kid (0.0054) Nice to listen to (0.0054) |

8 |

高清 (0.0047) 何仙姑 (0.0046) 评论 (0.0045) 天公(0.0044)

High Definition (0.0047) He Xiangu (0.0046) Commentary (0.0045) God of Heaven (0.0044)

|

Theme 3

Chaoshan Overseas Community

(0.21) |

很棒 (0.0069), 用心 (0.0066), 视频 (0.0056), 有没有(0.0050), 泰国 (0.0049)

Great (0.0069), Careful (0.0066), Video (0.0056), Is there (0.0050), Thailand (0.0049)

|

7 |

感谢 (0.0049) 作者 (0.0049) 版本 (0.0049) 八仙 (0.0049)祝寿 (0.0047)

Thanks (0.0049) Author (0.0049) Version (0.0049) Eight Immortals (0.0049) Birthday Wishes (0.0047) |

Based on LDA topic analysis, comments on the Wu Fulian videos on Bilibili reflect three major topics: traditional Teochew culture, audiovisual experience of Teochew Opera, and the Chaoshan overseas community. For example, there are references to overseas Chinese communities in countries such as Thailand and Singapore watching these videos, especially during festive occasions like the Chinese Spring Festival春节.

Topic 1: Traditional Teochew Culture (55%)

This topic is characterized by keywords including: Five Blessings (五福), Teochew Opera (潮剧), Worship (拜神), and Birthday Celebration (祝寿). It centers on traditional Teochew culture, encompassing holiday celebrations (e.g., Five Blessings, Birthday Celebration祝寿), religious rituals (e.g., Worship拜神). This indicates that Teochew culture is a central topic, with related terms appearing across all three themes, especially in discussions of classic repertoires and performances.

Topic 2: Audiovisual Experience of Teochew Opera (24%)

This topic highlights the audiovisual qualities of Wu Fulian 五福连videos, with core keywords such as: Teochew Opera, Good to Listen, Version, and Childhood . It includes viewer evaluations of audiovisual quality (e.g., high definition, pleasant listening), nostalgic references (e.g., childhood memories), and comparisons among different performance versions. Notably, there are also critical comments such as “weird” (奇怪), pointing out that some modern adaptations are perceived as inferior in production technique and content compared to classic versions. This aligns with earlier observations of our study that audiences prefer classical interpretations and are often dissatisfied with adaptations on new media platforms or performances by younger troupes.

Topic 3: Chaoshan Overseas Community (21%)

This set of comments incorporates international perspectives, including descriptions of deity worship activities and Thanksgiving Opera performances 酬神戏(Yang, 2019), within overseas Chinese communities in Thailand and Singapore during events such as the Spring Festival.

These elements resonate with the worship 拜神practices highlighted in Topic 1. Moreover, the religious and folk conventions from Theme 1 (e.g., worshiping gods拜神) and the contemporary creative features of Theme 3 together illustrate a continuum spanning tradition and innovation. These insights help elucidate how Bilibili, as a new media platform, facilitates innovative formats for disseminating Teochew opera and underscores the distinctive characteristics of Teochew Opera’s propagation in digital environments.

However, it is also essential to note the “weird” and other critical comments in user feedback, as well as the fact that the new adaptations of Teochew Opera on the emerging platform, like Bilibili, has failed to attract a broader audience, viewers consistently regard the classic versions as more valuable. This perspective should be taken into account to improve the quality of content of the videos on new media platforms. Therefore, efforts to promote Teochew Opera must ensure not only innovative its formats but, more critically, a steadfast commitment to content quality.

Comment sentiment analysis

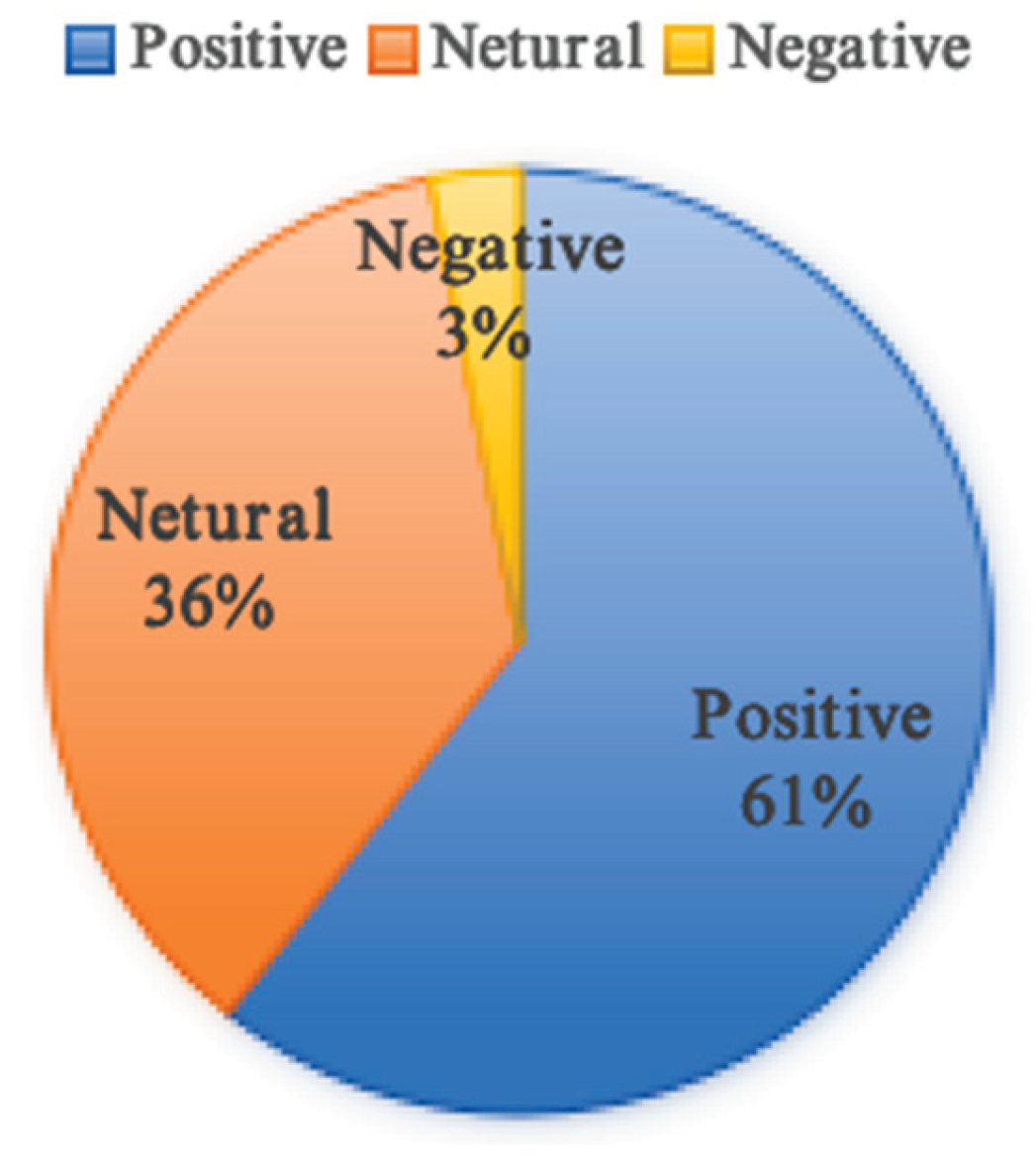

Figure 3.

Comment Sentiment of Wufulian.

Figure 3.

Comment Sentiment of Wufulian.

Sentiment analysis of comments on Wu Fulian videos reveals that positive sentiments account for 60.6%, neutral (36.4%) and negative sentiments represent 3%. This indicates that the majority of viewers hold a positive attitude toward the video content, with limited negative feedback. For instance, comments frequently include positive remarks such as "good" "the soundtrack is pleasant配乐好听" "great special effects特效很好" and expressions of gratitude to the content creators ("感谢UP主").

The neutral feedback consists of factual statements related to Teochew Opera, such as "the actress playing He Xiangu is called Huang Xiaohong何仙姑扮演者叫黄小虹" , "I’m watching the video on Bilibili我在B站看视频" or "Chen Wenyan performed at the first Teochew Opera Festival首届潮剧节那个就是陈文炎", which convey information without strong emotional tone.

Although negative feedback is limited, some criticisms were noted, including descriptions of the adapted versions as "weird奇怪" , "inferior to the classic ones不如旧版" , "decline in artistic technique技艺下降" "somewhat odd很魔性", "blurry picture quality画质低" and "falsely high-definition伪高清". These points highlight areas that need improvement in future content production on Bilibili .

Comment Content Analysis.

Table 15.

Typical comments of Wufu Lian videos on Bilibili.

Table 15.

Typical comments of Wufu Lian videos on Bilibili.

| Category |

Typical comments |

Ritual Anchoring and folk beliefs

construction

|

"Perfect timing to play this for the tonight worshipping";

"Worshipping the deities at home tonight";

"I can use this for tonight worshipping;

"Worshipping +1" "Dedicated for playback during ancestor worship".

拜天公正好要播;今晚家里拜神;刚好今晚用到;拜神+1;拜公祖播放专用; |

| Collective memory association |

"carved in DNA";

"childhood memories";

"Listening to it again is like returning to my childhood".

"这个是潮汕人刻在DNA里的";

"童年回忆"

"重新听就像回到童年" |

| Cultural Transmission |

"Eight Immortals Celebrate Longevity," which carries meanings of praying for blessings, auspiciousness, and good wishes.

"This play is invariably the premiere performance during New Year festivals, or celebrations";

"It is an auspicious opera beloved by the masses".

《八仙庆寿》, 寓有祈福、吉祥、祝愿的意义.

逢年过节或喜庆之日演出潮剧必首演此戏,

是群众喜闻乐见的吉祥戏. |

| Diaspora Connectivity And Community building |

"When I’m away from home... it feels like returning"; "Teochew Opera art is well-developed in Southeast Asia."

"在外地...感觉像回家了一样"

"潮剧艺术在东南亚发展得很好"

|

| Video quality evaluation |

"Nowadays, Teochew opera is just about singing, with no acting to speak of";

"It’s a classic; one can only say that contemporary Teochew opera is unusually declined.

"现在的潮剧, 就是唱, 没有演技可言了"

"经典, 只能说现在的潮剧不是一般的落寞了"; |

These user comments reveal the multifaceted role of Wufu Lian. First, the videos serve a ritual function. Comments explicitly describe their use in specific worship practices, such as 拜天公 (worshipping the Heaven God), highlighting that these videos are not merely entertainment but essential digital ritual object on Bilibili.

Second, the content acts as an anchor of collective memory, triggering personal and collective nostalgia. Phrases like "carved into DNA" indicate these performances are deeply embedded in Chaoshan identity, serving as an auditory and visual time capsule that reinforces this shared heritage.

Regarding cultural transmission, users in the comment section highlighted the symbolic meanings and traditional values embodied in Wufu Lian. This helps other viewers gain a deeper understanding of Ban-xian-xi , thereby facilitating the cultural transmission of Teochew Opera through digital platforms, especially among younger audiences.

Fourth, the content strengthens diaspora connectivity. For overseas Chaoshan people, it provides a cultural lifeline, alleviating homesickness through accessible sensory experiences. Comments such as "feels like returning home" illustrate how these videos strengthen transnational community bonds and ensure cultural continuity of the Chaosha community.