Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

11 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

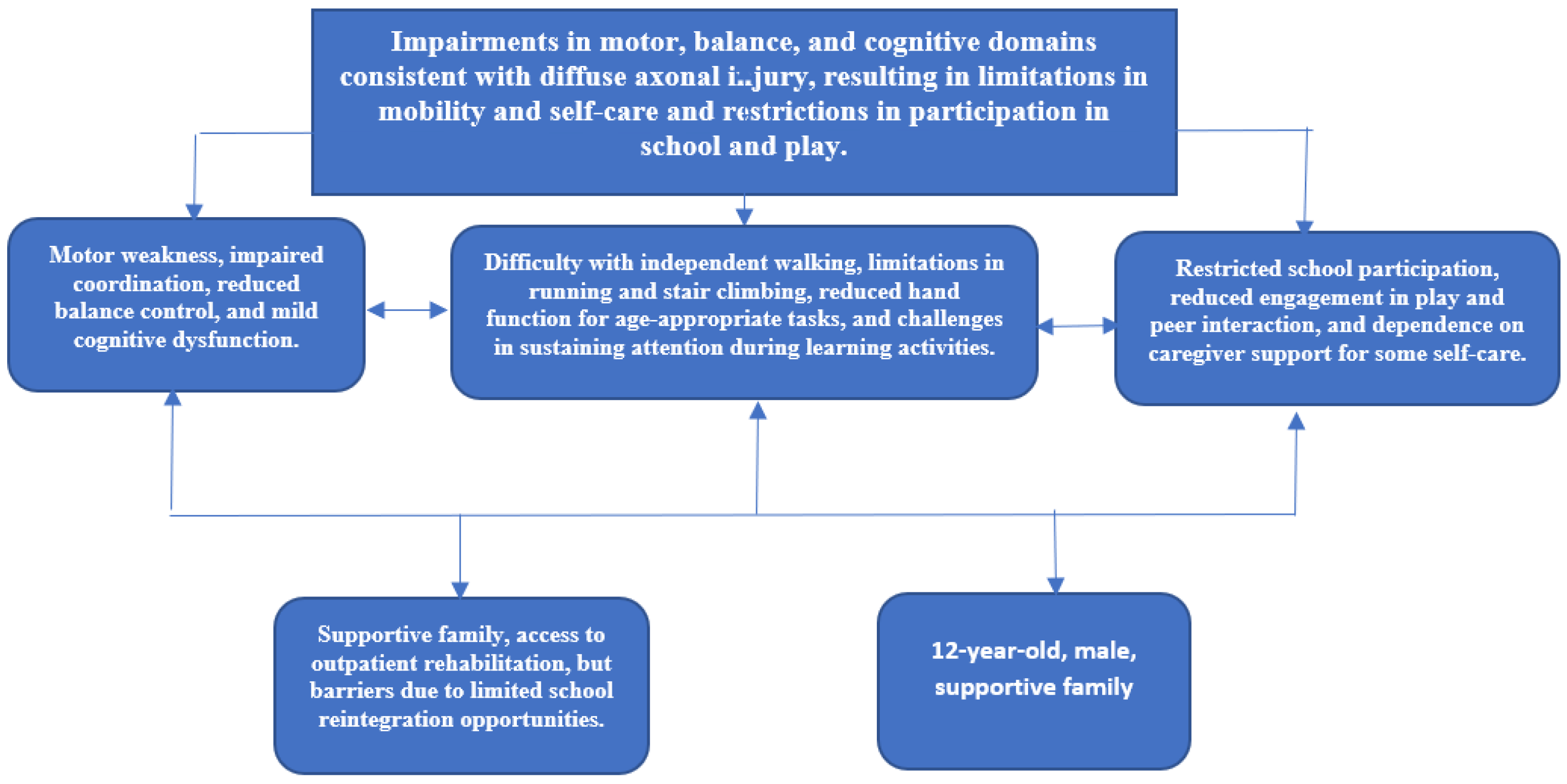

Background: Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) in children remains one of the most challenging outcomes of traumatic brain injury, characterized by widespread axonal disruption leading to complex motor, cognitive, and behavioral impairments. The pediatric brain, though endowed with remarkable plasticity, is particularly vulnerable to shearing injuries that compromise developmental milestones and participation. Rehabilitation, therefore, becomes the bridge between survival and meaningful recovery. This case report illustrates the structured application of the World Health Organization’s Package of Interventions for Rehabilitation (PIR) in the physiotherapy management of a pediatric outpatient with DAI, demonstrating the clinical and functional impact of a globally guided, play-based approach. Case Presentation: A 12-year-old boy presented to the outpatient physiotherapy unit with mild right-sided hemiparesis and gait asymmetry following a fall from a one-story building, diagnosed as diffuse axonal injury (Adams Grade III). The patient exhibited impaired coordination, poor gait toe-off, and limited endurance but intact cognitive and communication abilities. Rehabilitation goals were framed within the WHO PIR and ICF-CY domains, emphasizing motor recovery, activity participation, and environmental support. Intervention and Outcomes: Rehabilitation spanned seven months, combining weekly in-clinic physiotherapy with structured home programs guided by the caregiver. Therapy progressed from postural control and selective motor facilitation to interactive play-based activities such as obstacle courses, hopscotch, and task-oriented games designed to retrain balance, coordination, and gait mechanics. Play served not just as motivation but as a therapeutic medium linking movement, cognition, and social engagement. By week 28, the child regained independent ambulation, improved fine motor precision, and full reintegration into school and peer play. These gains reflected the adaptability and effectiveness of the WHO PIR framework in optimizing pediatric neuro-recovery within a resource-limited outpatient setting. Conclusions: This case reaffirms that physiotherapy, when guided by structured frameworks like the WHO PIR, transcends symptom relief to restore participation, confidence, and quality of life. The integration of play within a goal-oriented rehabilitation plan highlights the power of child-centered therapy to transform neuro-recovery into a holistic journey restoring not only function but the essence of childhood itself.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Importance of Rehabilitation in Recovery.

Relevance of Who PIR Guideline as a Structured Rehabilitation Framework.

Aim

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Demographics

2.2. Case Background

2.3. Assessment

2.4. Rehabilitation Goals (Based on WHO PIR and ICF Framework)

2.5. Functional Outcomes and Progress Across Rehabilitation Phases

2.6. Prognosis

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DAI | Diffuse Axonal Injury |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PIR | Package of Interventions for Rehabilitation |

| ICF-CY | International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health – Children and Youth Version |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| TBI | Traumatic Brain Injury |

| GMFM-88 | Gross Motor Function Measure – 88 Item Version |

| BBS | Berg Balance Scale |

| PBS | Pediatric Balance Scale |

| 10-MWT | 10-Meter Walk Test |

| WeeFIM | Functional Independence Measure for Children |

| PedsQL | Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| ICF | International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health |

References

- Sasun AR, Qureshi MI. Physiotherapy rehabilitation as an adjunct to functional independence in diffuse axonal injury: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30255. [CrossRef]

- Lalwani SS, Dadgal R, Harjpal P, Saifee SS, Lakkadsha TM. Perks of early physical therapy rehabilitation for a patient with diffuse axonal injury. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30886. [CrossRef]

- Dangare MS, Saklecha A, Harjpal P. A case report emphasizing an early approach in a patient with diffuse axonal injury. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e52750. [CrossRef]

- Smith DH, Hicks R, Povlishock JT. Therapy development for diffuse axonal injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(5):307–23. [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa-Arredondo T, Choreño-Parra JA, Corona-Ruiz JA, Rodríguez-Muñoz PE, Pacheco-Sánchez FJ, Rodríguez-Nava AI, et al. Beneficial effects of a multidomain cognitive rehabilitation program for traumatic brain injury-associated diffuse axonal injury: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):36. [CrossRef]

- Alkhalifah A, Alkhalifa M, Alzoayed M, Alfaraj D, Makhdom R. Unusual presentation of diffuse axonal injury: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14(11):e31336. [CrossRef]

- Wu XL, Liu LX, Yang LY, Zhang T. Comprehensive rehabilitation in a patient with corpus callosum syndrome after traumatic brain injury: case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(28):e21218. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Package of interventions for rehabilitation (PIR): introduction and overview. Geneva: WHO; 2022.

- World Health Organization. Package of interventions for rehabilitation (PIR): module 3 — neurological conditions. Geneva: WHO; 2023.

- World Health Organization. Package of interventions for rehabilitation (PIR): module 5 — neurodevelopmental disorders. Geneva: WHO; 2023.

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation in health systems: a guide for action. Geneva: WHO; 2019.

- Adams JH, Doyle D, Ford I, Gennarelli TA, Graham DI, McLellan DR. Diffuse axonal injury in head injury: definition, diagnosis and grading. Histopathology. 1989;15(1):49–59. [CrossRef]

- Franjoine MR, Gunther JS, Taylor MJ. Pediatric balance scale: a modified version of the Berg Balance Scale for the school-age child with mild to moderate motor impairment. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2003;15(2):114–28. [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, RW. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20–79 years: reference values and determinants. Age Ageing. 1997;26(1):15–9. [CrossRef]

- Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. The WeeFIM® instrument: the functional independence measure for children. Version 5.1. Buffalo (NY): State University of New York at Buffalo; 1993.

- Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL™ 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39(8):800–12. [CrossRef]

- Russell DJ, Rosenbaum PL, Avery LM, Lane M. Gross motor function measure (GMFM-66 & GMFM-88) user’s manual. London: Mac Keith Press; 2002.

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Standards and operational guidance for ethics review of health-related research with human participants. Geneva: WHO; 2011. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310666/.

| Domain | Findings In Patient |

|---|---|

| Mental/cognitive function | Mild attention deficits, slowed information processing, occasional difficulty with memory recall. |

| Mental/emotional function | Frustration when unable to complete tasks independently; eager to return to school. |

| Vision impairment | No visual deficits reported. |

| Hearing impairment | Hearing intact. |

| Speech, language and communication | Mild word-finding difficulty; reduced fluency under stress but able to communicate needs. |

| Ingestion function and dysphagia management | No swallowing or feeding difficulties reported. |

| Nutrition | Normal diet maintained; caregiver supervises adequate intake. |

| Pain management | Intermittent headaches post-injury, manageable without daily analgesics. |

| Bowel/bladder management and toileting | Independent; no incontinence reported. |

| Sexual function and intimate relationship | Nil abnormality detected. |

| Respiration function | Stable; no respiratory compromise. |

| Cardiovascular and hematological function | Normal vital signs, no cardiovascular limitation. |

| Motor function and mobility | Impaired balance and coordination; unsteady gait; reduced endurance for prolonged walking and stair use. |

| Activities of daily living | Needs supervision with bathing and dressing for safety; able to perform feeding independently. |

| Exercise and fitness | Reduced stamina; unable to engage in vigorous play compared to peers. |

| Interpersonal interaction and relationship | Avoids group play due to fear of falling; interacts mainly with close family. |

| Education and vocation | School attendance disrupted; difficulty sustaining classroom attention. |

| Community and social life | Limited outdoor play; reduced participation in peer activities. |

| Family and care support | Strong caregiver involvement; mother highly engaged in rehabilitation program. |

| Self-management | Limited insight due to age; relies on caregiver support for adherence to therapy. |

| Lifestyle modification | Family encouraged to promote safe play, structured exercise, and rest periods. |

| Problem | Missing Components | Underlying Reasons | Indicators / Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impaired balance and gait instability | Postural control, dynamic balance, lower limb coordination | Diffuse axonal injury leading to impaired proprioceptive feedback and cerebellar pathway disruption | Pediatric Balance Scale. |

| Reduced endurance and exercise tolerance | Muscular strength, aerobic fitness | Deconditioning secondary to limited mobility and inactivity post-injury | 10-meter Walk Test. |

| Cognitive and attention deficits | Sustained attention, short-term memory, concentration | Diffuse white matter injury affecting prefrontal cortical connections | Raven Cognitive Assessment and Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. |

| Reduced participation in school and social activities | Environmental interaction, peer engagement | Fatigue, anxiety, reduced confidence due to motor limitations | Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation. |

| Dependence in activities of daily living (ADLs) | Independence in self-care (bathing, dressing) | Impaired balance and fine motor coordination | Pediatric Functional Independence Measure (WeeFIM). |

| Emotional and behavioral adjustment difficulty | Self-regulation, coping, motivation | Psychological impact of trauma and prolonged recovery process | Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory. |

| Poor coordination and upper limb control | Fine and gross motor precision | Neural disconnection from axonal damage in motor tracts | Nine-Hole Peg Test, Box and Block Test. |

| Reduced community and outdoor participation | Confidence in mobility, safety awareness | Fear of falling, environmental barriers | Caregiver report, frequency of outdoor activity. |

| Limited self-management skills | Self-monitoring | Pediatric age and cognitive limitations | Caregiver adherence checklist. |

| PIR Domain / Functional Area | Baseline Intervention | 7-13 Weeks | 14-20 Weeks | 21-28 Weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Function & Coordination | Engaged in simple play-based fine motor tasks (pegboard, stacking blocks, ball transfer); facilitated right upper limb activation using games and PNF patterns; introduced grasp-and-release play | Introduced bilateral hand coordination games (sorting toys, puzzles); object manipulation and sensory-rich play to enhance proprioceptive input | Play gym sessions with resistance bands, target-throwing, and drawing activities for fine motor endurance | Timed dexterity games, creative art play, and dual-task coordination challenges simulating school/playground activities |

| Mobility & Gait Training | Assisted walking with visual feedback; focus on right toe-off facilitation and weight-shift using toy-retrieval games | Obstacle course walking with colored targets; treadmill walking using storytelling play cues | Hopscotch and ladder games to improve stride length and rhythm; stair games for balance | Playground simulation—jumping, skipping, and sports-play tasks for independent gait control |

| Balance & Postural Control | Seated balance play on therapy ball; bubble-catching games to encourage trunk control | Dynamic balance through reaching games and step-stone play; musical freeze tasks | Single-leg balance and hopping games; catching-throwing while standing on uneven surfaces | Balance relay games, dual-task postural control play; eye–foot coordination tasks |

| Functional Activities / ADL Training | Encouraged self-dressing as play, toy-cleanup routines, and snack preparation games; caregiver-assisted transfers | Play-simulated daily routines (tooth brushing, toy washing) for independence | Household imitation games to reinforce ADL skills | Independent completion of morning routines and school readiness tasks with supervision |

| Cognitive & Behavioral Function | Short structured play tasks (memory card games, sequencing toys) to improve attention span | Problem-solving through play—building blocks, maze navigation | Role-play and imaginative play to enhance memory and decision-making | Independent game planning and rule-following; sustained participation without prompts |

| Communication & Interaction | Used sing-along games and interactive storytelling to stimulate speech | Peer play to enhance turn-taking and expressive communication | Group therapy play and storytelling with peers | Full verbal expression and cooperative play participation |

| Caregiver / Home Program | Education on home-based play therapy and safe toy selection; encouraged family participation | Home exercise games (throw–catch, hop–count) recorded in a caregiver diary | Progressed to structured play sessions 20–30 mins daily emphasizing balance and strength | Transitioned to self-directed functional play; caregiver supervision maintained for safety |

| Outcome Domain / Measure | Baseline (Week 0) | After 8 Weeks (Early Phase) | After 16 Weeks (Intermediate Phase) | After 28 Weeks (Late Phase / Discharge) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Function (GMFM-88) | Mild right-sided hemiparesis; reduced coordination during fine motor tasks of the upper limb; decreased dexterity in grasp and release activities | Improved fine motor coordination; able to perform bilateral hand activities with minimal assistance | Near-symmetric upper limb use during reaching and object manipulation | Normalized fine motor function with efficient bilateral coordination and hand control |

| Mobility (Gait / 10-Meter Walk Test) | Independent gait with lack of toe-off on the right side; shortened stride length and mild asymmetry | Improved foot clearance and partial toe-off during terminal stance; reduced limp | Nearly symmetrical gait pattern; stable cadence and improved step length | Normal gait with full toe-off and smooth weight transfer during ambulation |

| Balance (Pediatric Balance Scale) | Score: 32/56 - mild instability when turning or reaching | Score: 40/56 - steadier posture during transitions and static tasks | Score: 48/56 - improved dynamic balance, minimal sway | Score: 54/56 - independent balance; able to perform single-leg stance for 10s |

| Functional Independence (WeeFIM) | Mostly independent; needs help in dressing and stair climbing (score: 90/126) | Improved dressing and toileting independence (score: 102/126) | Fully independent in most ADLs except high-demand tasks (score: 115/126) | Fully independent; age-appropriate task performance (score: 123/126) |

| Cognitive Function (Attention & Task-following) | Mild difficulty sustaining attention; forgets multi-step tasks | Improved focus with structured cues | Follows two-step commands reliably | Sustained attention throughout tasks; independent recall of therapy routines |

| Emotional / Social Interaction | Initially shy and withdrawn; limited interaction during sessions | Engages willingly with therapist and peers | Increased social confidence; responds to praise | Fully expressive, active peer engagement and motivation maintained |

| Caregiver Burden (Zarit Short Scale) | Mild stress due to home program adjustment | Confidently implements exercise schedule | Positive feedback on home progress | Comfortable with self-management and long-term follow-up adherence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).