1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) represents a significant global health issue, necessitating effective and patient-centered treatment approaches [

1]. Standard whole-gland treatments, including radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy, remain the primary management strategies for clinically significant prostate cancer but are frequently associated with urinary, sexual, and bowel-related adverse effects [

2].

Focal therapy (FT) has emerged as a promising treatment option aimed at achieving comparable oncological outcomes to whole-gland therapies while minimizing treatment-related adverse events (AEs) [3-5]. This approach has generated considerable interest among urologists and patients, particularly for the management of low- to intermediate-risk PCa.[

6]. The growing enthusiasm for FT can largely be attributed to advancements in early detection of localized PCa through effective screening programs and the enhanced diagnostic accuracy provided by multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging (mpMRI) in identifying and localizing clinically significant lesions [

1,

4,

7].

FT primarily employs ablative techniques, with high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, irreversible electroporation, and focal brachytherapy being among the leading modalities [

8]. HIFU, specifically, is currently the most extensively utilized technology, with the largest body of clinical data available [

2,

9].

Despite its increasing adoption, current European Association of Urology (EAU) prostate cancer guidelines categorize FT as an experimental modality, recommending its application exclusively within clinical trial settings due to a significant lack of robust prospective evidence [10-12]. Nonetheless, surveys indicate widespread usage among urologists, with approximately half of European urologists recommending or performing FT [

13].

In this report, we present the outcomes of a prospective, single-arm, phase II clinical trial assessing both oncological efficacy and functional results of focal therapy using HIFU in patients diagnosed with low- to intermediate-risk PCa.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective, non-randomized, phase 2 clinical study was conducted at three hospitals in Lower Austria between 2021 and 2024. Approval was obtained from the Lower Austria Ethical Board (approval number GS4-EK-3/162-2020). All participants provided written informed consent after receiving comprehensive information regarding established treatment options such as radical prostatectomy (RP) or radiotherapy (RT) and explicitly chose not to pursue active surveillance.

Eligible patients were treatment-naïve males diagnosed with non-metastatic PCa categorized as low- or intermediate-risk according to the D’Amico classification [

14], with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels ≤15 ng/mL and clinical stage ≤T2. Additional inclusion criteria mandated the absence of significant lesions (classified as Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2.1 (PI-RADS ≥4) [

15] on the contralateral prostate side and biopsy-confirmed prostate cancer lesions concordant with mpMRI findings. Low-risk patients were included only if they had declined active surveillance.

Exclusion criteria encompassed prior prostate surgery within the preceding six months, tumor proximity of less than 7 mm to the urethral sphincter, and treatment areas more than 45 mm away from the rectum [

16]. Patients presenting with perilesional prostate calcification or rectal pathologies were also excluded. Additionally, patients showing evidence of extraprostatic tumor extension, suspicious regional lymph nodes, or distant metastases identified by mpMRI, cross-sectional imaging, or bone scans were excluded from participation.

Pre-treatment

Patient characteristics were systematically recorded. These included age at intervention, PSA level, prostate volume, PI-RADS classification, Gleason grade group, International Prostate Symptom Score Questionnaire (IPSS), International Index of Erectile Function Questionnaire (IIEF), Gaudenz Incontinence Questionnaire [

17], family history of prostate cancer, current medications, comorbidities, findings from digital rectal examination, and smoking history. Health-related quality of life was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (SF-36) [

18].

Treatment Protocol

HIFU procedures were performed using the Focal One system (EDAP TMS, Lyon, France). Ablation was directed at biopsy-confirmed index lesions with ISUP ≥2. In patients with low-risk PCa, the ISUP 1 lesions were treated. Treatment planning was based on mpMRI images, with urologists and radiologists collaboratively contouring the prostate. Treatment was monitored in real time via live sonography. A safety margin of 9 mm was applied around all targeted lesions. The neurovascular bundles and urethra were not specifically spared.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) (SonoVue®) was used intraoperatively to assess ablation completeness. If residual tissue was suspected, an additional treatment pass was administered.

A Foley catheter was placed at the end of the procedure. All treatments were performed under general anesthesia.

Adverse Events and Salvage Therapy

Complications were recorded prospectively and graded according to the Clavien–Dindo classification [

19]. The protocol permitted repeat HIFU sessions. Patients could undergo radical treatment based on follow-up biopsy findings [

20].

Follow-up

Follow-up included PSA testing every three months during the first two years post-treatment. Patients completed the IPSS, IIEF, and Incontinence Questionnaire at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. Health-related quality of life was assessed using the SF-36. [

18]

Multiparametric MRI was repeated at 12 and 24 months. Follow-up mpMRI/US Fusion biopsies were conducted at 12 months. These included systematic biopsies from both treated and untreated regions, and targeted biopsies if suspicious lesions were visible.

Beyond 12 months, biopsies were performed only when biochemical or imaging findings suggested recurrence, rather than on a fixed timetable [

21]. Triggers included PSA rise or suspicious lesions on mpMRI.

Our primary outcome was FFS defined as no transition to any of the following: local salvage therapy (radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy), systemic therapy, metastases, or prostate cancer-specific mortality [

22]. Contralateral positive biopsy was classified as outfield failure. Pathological failure was defined as the presence of clinically significant PCa in biopsy. No salvage treatment was initiated in the absence of pathological fail.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), while categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers with percentages. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.0.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

A total of 52 patients were enrolled. Data from one patient at a collaborating site were excluded from the analysis because of a major protocol deviation—his pre-treatment PSA level exceeded 15 ng/mL—leaving 51 patients in the per-protocol cohort. Mean follow up time was 12.9 months.

The median age was 66.9 (IQR 60.5 – 73.5). Median PSA level was 7.55 ng/mL (5.4 – 9.4) with a mean Prostate Volume of 40.2 mL (29 – 52). The prostate volume was measured on MRI. ISUP Grade Group distribution was ISUP 1 20 Patients (39.2%) ISUP 2 25 Patients (49%) and ISUP 3 6 Patients (11.8%). Additional characteristics of the study cohort are shown in

Table 1.

Treatment characteristics are summarized in

Table 2.

Thirty-one patients (60.1 % of the treated cohort) underwent at least one post-HIFU biopsy. Seven declined the protocol-mandated 12-month biopsy because their PSA values remained low and stable. Pathology was negative in 26/31 biopsied patients (83.9 %). Cancer was identified in five cases: three ISUP 1 lesions, one ISUP 2 lesion and one ISUP 4 lesion located contralaterally to the ablation field (out-of-field disease).

One of the ISUP 1 Patients proceeded to external-beam Rt, while the other two chose active surveillance and remain on that pathway. The patient with ISUP 2 lesion was also referred to Rt. One patient with the ISUP 4 cancer was scheduled for salvage open radical prostatectomy, but the operation was aborted intra-operatively because of dense peri-rectal adhesions; he subsequently received Rt plus androgen-deprivation therapy. Notably, the ISUP 4 case had been classified as ISUP 1 before the HIFU Therapy.

Beyond 12 months, biopsies were performed only when recurrence was suspected, defined by the triggers mentioned before. Three patients met one of these criteria. Two showed no residual malignancy, whereas one harbored an ISUP 1 cancer, considered clinically insignificant.

Overall, three patients (5.9%) had definitive salvage invasive treatment within the first 24 months after focal HIFU. No patient developed metastases or died of prostate cancer during follow-up.

3.1. Safety

Procedure-related adverse events (AEs), defined as those considered related or possibly related to treatment, observed within the first 2 years are summarized in

Table 3.

A total of 14 patients (27%) experienced at least one adverse event. The most common AE was transient acute urinary retention, occurring in 11 patients (21.6%), typically within 30 days following therapy. A single short hospital admission (2 %) was recorded. Six patients (11.8%) required placement of a suprapubic catheter under local anesthesia. Three patients experienced urinary tract infections post-procedure; two of these cases involved epididymitis, which resolved with oral antibiotic therapy. By the 12-month follow-up, only one moderate AE remained unresolved—a recurrent urethral stricture. All other adverse events had resolved by the 3-month follow-up visit. No Clavien-Dindo Grade 4 adverse events were reported.

A single patient developed muscle-invasive bladder cancer 19 months after HIFU; definitive staging and treatment decisions were still pending at data cut-off. Because of the tumour’s anatomical location and the long latency, the event was considered unlikely to be attributable to the focal HIFU procedure.

Two patients died during follow-up from cardiovascular events—one from an ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and the other from a mitral valve rupture, occurring 7 month and 13 months after the last HIFU session, respectively. Neither death was judged related to the malignancy or to the HIFU treatment.

3.2. PSA Dynamics

Figure 1. illustrates the serum PSA trajectory for the entire study population (n = 51) over 24 months. Baseline mean PSA was 7.55 ng/mL (95 % CI 6.57–8.53). A steep decline occurred within the first 3 months, reaching 2.31 ng/mL (95 % CI 1.69–2.92); this represents an absolute reduction of 5.24 ng/mL and a relative drop of 69.3 % from baseline.

Between 3- and 6-months PSA values stabilized at about 2.3 ng/mL (95 % CI 1.56–3.16). A modest upward inflection was observed at 9 months (mean 2.87 ng/mL, 95 % CI 1.91–3.84) and persisted through 12 months (2.93 ng/mL, 95 % CI 1.43–4.42). Thereafter, PSA oscillated within a narrow band (2.4–2.9 ng/mL) with overlapping confidence intervals at 15, 18, 21 and 24 months, indicating biochemical steadiness rather than progressive rise. Notably, the upper 95 % CI never exceeded 4.5 ng/mL during follow-up, suggesting durable PSA suppression for most patients.

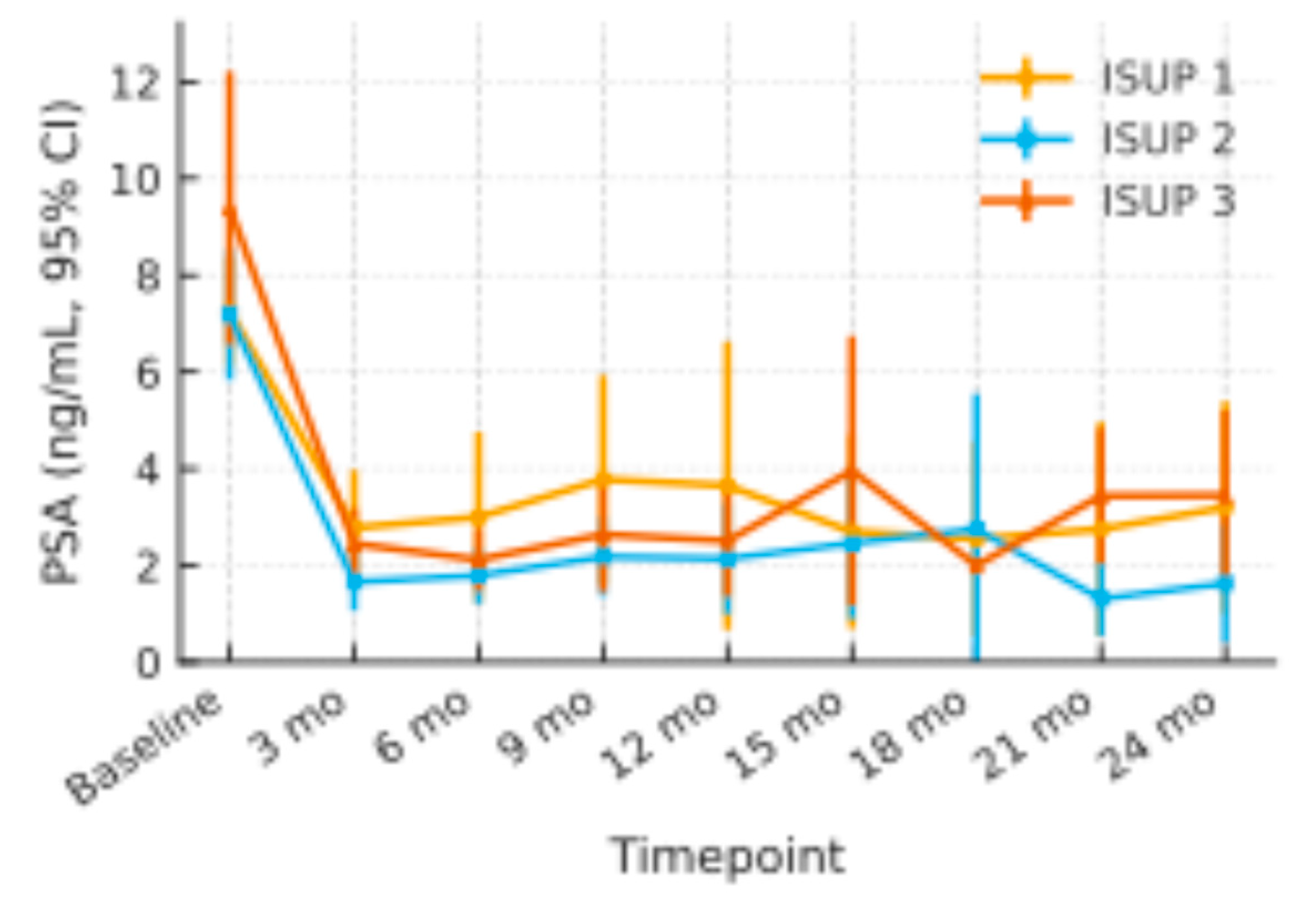

Figure 2.

PSA Changes through the ISUP Subgroups with 95% Confidence Interval.

Figure 2.

PSA Changes through the ISUP Subgroups with 95% Confidence Interval.

Across ISUP 1 (n =20), ISUP 2 (n = 25), and ISUP 3 (n =6) patients, baseline mean PSA values were 7.3 ng/mL (95 % CI 6.1–8.4), 7.2 ng/mL (5.8–8.5), and 9.4 ng/mL (6.6–12.2), respectively. All three groups showed a comparable early decline at 3 months (ISUP 1: 2.8 ng/mL; ISUP 2: 1.7 ng/mL; ISUP 3: 2.5 ng/mL) and maintained PSA levels within the 2–4 ng/mL range throughout 24 months. Confidence-interval widths overlapped at every time-point, and no sustained divergence of mean curves was observed

3.3. Imaging Follow Up

When the protocol was written, no validated mpMRI scoring system existed for the ablated prostate. Follow-up scans were therefore classified in binary fashion as “suspicious” or “not suspicious” for residual disease. Six scans were judged suspicious. Targeted biopsies confirmed cancer in two of those six cases—one out-of-field ISUP 4 lesion (described above) and one additional ISUP 1 focus—giving qualitative mpMRI a positive-predictive value of 33 % in this cohort.

3.4. Functional Outcomes

When all 37 evaluable patients were pooled, mean IPSS rose transiently at the first post-treatment visit (median +1.8 points vs. baseline), indicating short-term irritative/obstructive symptoms. Thereafter the score declined steadily, falling below the pre-treatment mean by month 12 and remaining stable through month 24. Because baseline symptom burden strongly influences clinical interpretation, we stratified patients by their pre-treatment IPSS.

In the Good-baseline group IPSS remained within the minimal clinically important difference (±3 points) throughout follow-up, signalling preservation of already satisfactory urinary function.

Men with Moderate/Severe baseline symptoms experienced a clinically meaningful improvement: mean IPSS fell by 7.8 points (-59 %) at 24 months, with the largest drop occurring between 6 and 12 months.

These divergent trajectories (illustrated in

Figure 3.) suggest that HIFU is function-sparing for patients who start with good LUTS profiles, while simultaneously offering symptom relief to those entering treatment with bothersome voiding complaints.

Figure 3.

IPSS Trajectory after Therapy, stratified by baseline LUTS Severity.

Figure 3.

IPSS Trajectory after Therapy, stratified by baseline LUTS Severity.

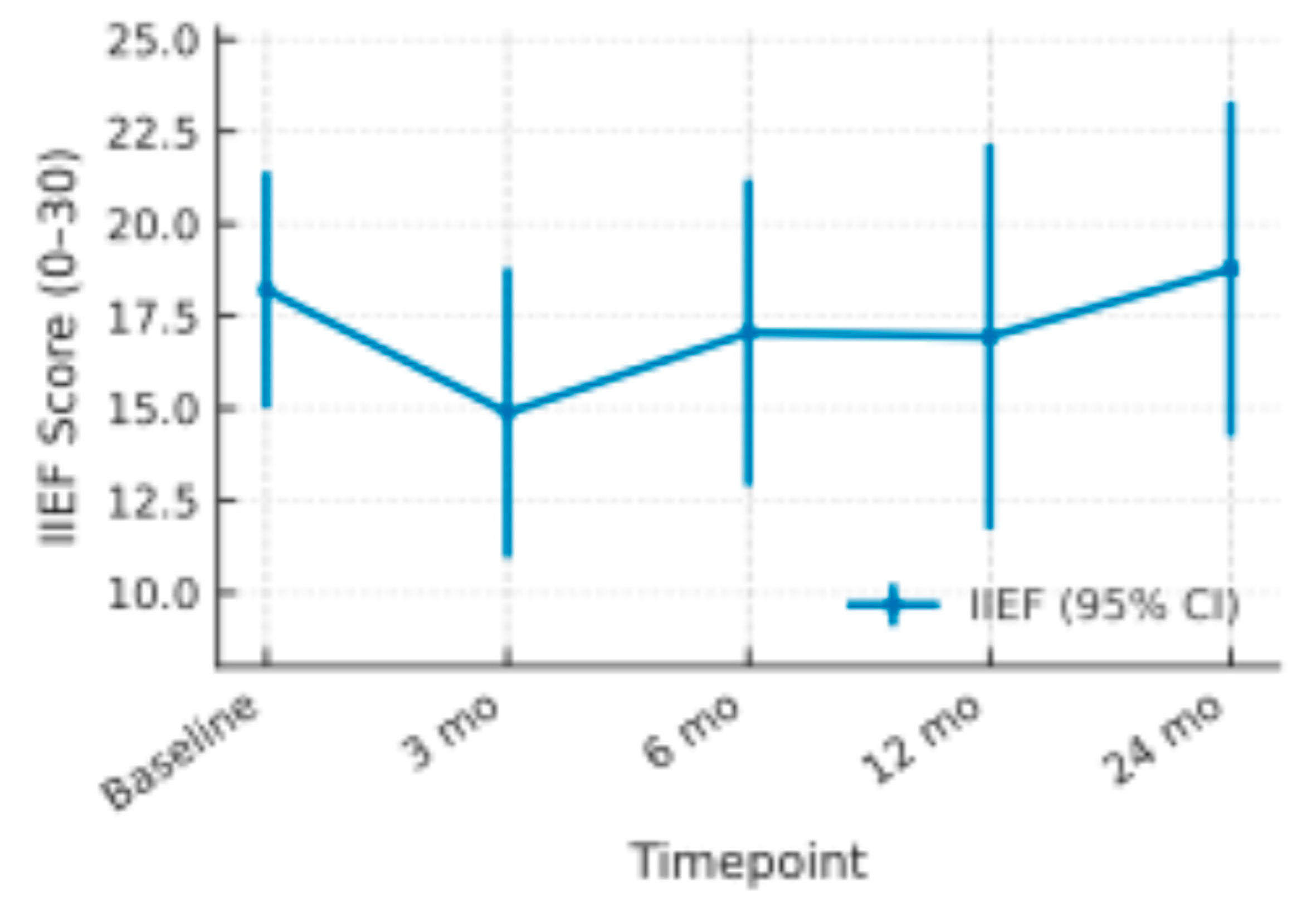

Figure 4.

Mean IIEF Scores with 95% Confidence Intervals.

Figure 4.

Mean IIEF Scores with 95% Confidence Intervals.

Mean baseline IIEF was 18.2 (95 % CI 15.0–21.4). Scores dropped by roughly three points at 3 months (14.9; 11.0–18.8) but climbed to 17.1 at 6 months and 16.9 at 12 months. By 24 months the mean slightly surpassed baseline at 18.8 (14.2–23.3). Across all assessments the 95 % confidence intervals overlapped the pre-treatment range, indicating only a transient, largely reversible decline in erectile function after therapy.

Only a single participant experienced de-novo urinary incontinence, classified as grade 2 incontinence (loss of urine during physical activity or positional change). The episode followed a prolonged urinary-tract infection in a patient with poorly controlled diabetes and prior acute urinary retention.

3.5. Outcome of Quality of Life

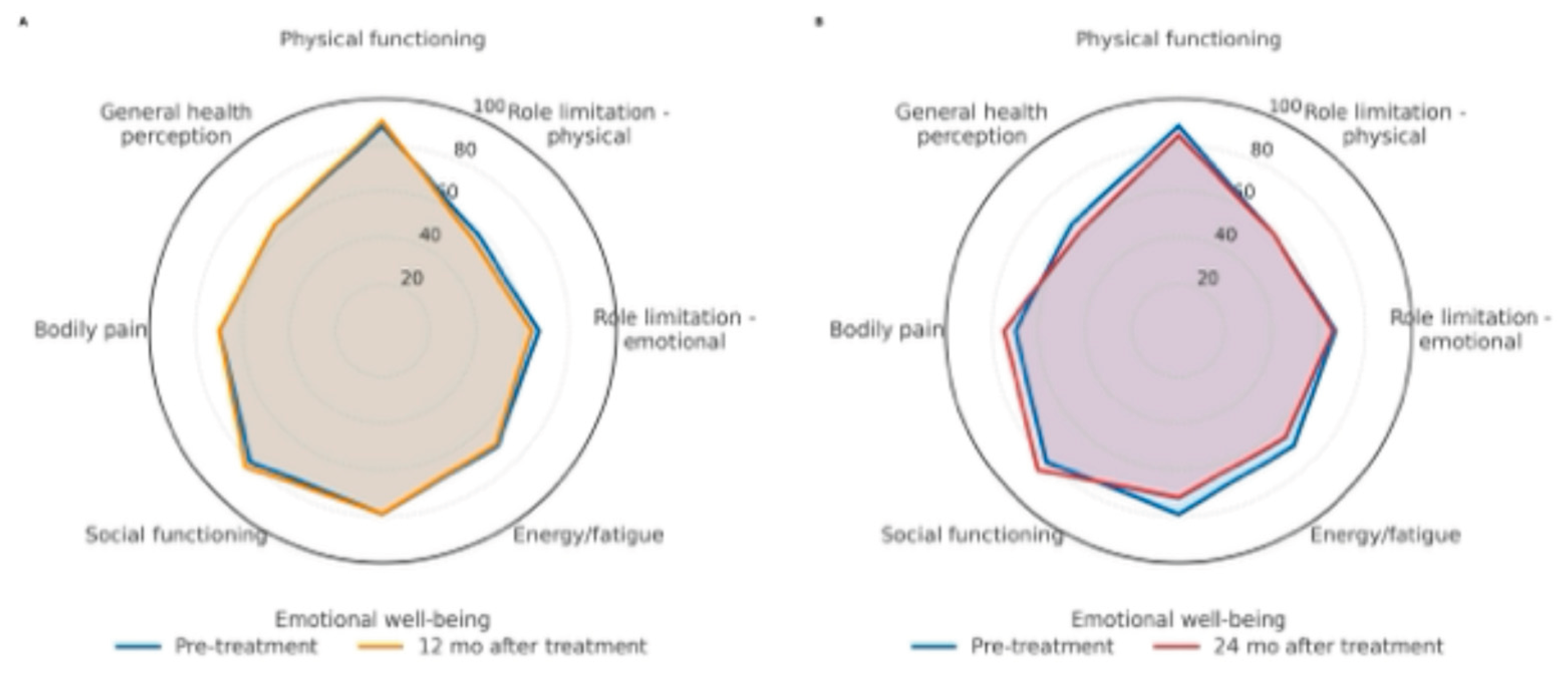

Regarding health-related quality of life, 53% of patients completed the SF-36 questionnaire at scheduled follow-up visits. Adjusted mean scores at baseline and throughout follow-up were calculated using mixed-model analyses. Scores remained stable across all dimensions, with no statistically significant differences observed over time. Stability of scores suggests a sustained quality of life following the intervention. For clarity and improved readability, only data from pre-intervention, 12-month, and 24-month follow-up visits are illustrated in the radar chart.

Figure 5.

SF-36 radar: Pre vs 12 months (A) and Pre vs 24 months (B).

Figure 5.

SF-36 radar: Pre vs 12 months (A) and Pre vs 24 months (B).

4. Discussion

This prospective study evaluated the medium-term oncological, functional and quality of life outcomes of HIFU in patients with localized prostate cancer. At 24 month 94.1% of the patients avoided radical whole gland treatment. These real-life, multicenter, prospective results confirm the data from other international studies [23-26].

A key finding is the preservation of quality of life: patients treated with HIFU maintained stable health-related QoL scores throughout follow-up. [

27].

Urinary outcomes were particularly encouraging, which can be caused by the shrinkage of the prostate after the HIFU therapy [

28,

29].

As expected, IPSS rose briefly at one month, reflecting transient irritative/obstructive symptoms. Thereafter, scores declined steadily. Stratification by baseline LUTS burden revealed a clinically important dichotomy:

Good baseline function (IPSS ≤ 8)—scores remained within the minimal clinically important difference throughout follow-up, indicating true function-sparing.

Moderate/severe baseline LUTS (IPSS > 8)—mean IPSS fell from 13.1 to 5.8 (-45 %) by 24 months, suggesting that prostate shrinkage after focal therapy can translate into durable symptom relief

Thus, HIFU not only preserves satisfactory voiding function but can rehabilitate clinically bothersome LUTS, broadening its appeal across patient phenotypes.[

29]

The AE profile in our series closely paralleled that of earlier HIFU reports, both in frequency and in severity [

7,

23,

30]. The two deaths observed during follow-up were attributed to pre-existing cardiovascular disease in older participants and were adjudicated as unrelated to either the cancer or the HIFU procedure.

Clinical practice continues to reveal two groups gravitating toward focal HIFU: younger patients focused on preserving erectile function and older, comorbidity-burdened individuals seeking to avoid the systemic stress of radical treatment [

27,

31,

32]. The present findings indicate that HIFU meets the therapeutic priorities of both cohorts.

Limitations

This study has several noteworthy constraints. First, enrollment and most follow-up visits took place during the COVID-19 pandemic; clinic-access restrictions meant that some assessments were captured at the nearest feasible visit rather than on the protocol date, introducing timing bias. Second, although the multicentre design enhances generalisability, it also led to minor inter-site differences in protocol adherence. Third, the trial was sized for feasibility, not for definitive oncological endpoints; with 51 evaluable patients and a median follow-up of 24 months, the study is under-powered to provide precise estimates of biochemical-recurrence-free, salvage-therapy-free, overall or cancer-specific survival.

Our diagnostic pathway relied on mpMRI with targeted plus systematic biopsies; however, mpMRI has an imperfect positive predictive value and sensitivity for clinically significant prostate cancer. Even with fusion-guided targeting, sampling error and MRI-occult foci can lead to under-grading or missed tumors. Such undetected or incompletely characterized lesions outside the ablation field can drive progression or salvage needs.

Functional data carry additional caveats. Erectile-function outcomes relied solely on the patient-reported IIEF-5, and 32 % of participants missed at least one IIEF-5 follow-up, widening confidence intervals and opening the door to responder bias. Overall questionnaire compliance fell from 100 % at baseline to 63 % at 24 months, leaving sizeable blocks of missing data. Only 31 of 51 patients (61 %) underwent the protocol-mandated 12-month biopsy, so residual disease may have been underestimated and the true positive-predictive value of mpMRI could not be fully assessed.

Finally, the two-year horizon is too short to detect late oncological failures or delayed declines in urinary and sexual function. These limitations caution against over-interpreting the favourable early results and underscore the need for larger trials with longer, more complete follow-up.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion this prospective multicentric 2 years follow up study demonstrates that mpMRI-guided focal HIFU yields encouraging early oncologic outcomes with low genitourinary morbidity and preserved quality of life.

The authors would like to acknowledge the entire teams that helped coordinate and execute this clinical study.

Funding

This research received fundings from the Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences, Krems, Austria. The authors want to appreciate the contribution of NÖ Landesgesundheitsagentur, legal entity of University Hospitals in Lower Austria, for providing the organizational framework to conduct this research. The authors also would like to acknowledge support by Open Access Publishing Fund of Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences, Krems, Austria.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Lower Austria Ethical Board (protocol code GS4-EK-3/162-2020, date of approval 02.12.2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Original data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT (OpenAI o3, February 2025 release) for the purposes of linguistic polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.:

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HIFU |

High Intensity Focused Ultrasound |

| PCa |

Prostate Cancer |

| mpMRI |

Multiparametric Magnet Resonance Imaging |

| FFS |

Failure Free Survival |

| IIEF |

International Index of Erectile Function |

| IPSS |

International Prostate Symptom Score |

| AEs |

Adverse Event |

| FT |

Focal Therapy |

| RP |

Radical Prostatectomy |

| RT |

Radiotherapy |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| PI-RADS |

Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| SF-36 |

Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 |

| 5ARI |

5-alpha reductase inhibitor |

| CEUS |

Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound |

| LUTS |

Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms |

References

- James, N.D.; Tannock, I.; N'Dow, J.; Feng, F.; Cillessen, S.; Ali, S.A.; Trujillo, B.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Attard, G.; Bray, F.; et al. The Lancet Commission on prostate cancer: planning for the surge in cases. The Lancet 2024, 403, 1683–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopstaken, J.S.; Bomers, J.G.R.; Sedelaar, M.J.P.; Valerio, M.; Fütterer, J.J.; Rovers, M.M. An Updated Systematic Review on Focal Therapy in Localized Prostate Cancer: What Has Changed over the Past 5 Years? Eur Urol 2022, 81, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouraviev, V.; Mayes, J.M.; Polascik, T.J. Pathologic basis of focal therapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2009, 6, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Rooij, M.; Hamoen, E.H.; Witjes, J.A.; Barentsz, J.O.; Rovers, M.M. Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Local Staging of Prostate Cancer: A Diagnostic Meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2016, 70, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.U.; Freeman, A.; Kirkham, A.; Sahu, M.; Scott, R.; Allen, C.; Van der Meulen, J.; Emberton, M. Focal therapy for localized prostate cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Urol 2011, 185, 1246–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, N.; Shariat, S.F.; Remzi, M. Focal therapy of prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol 2018, 28, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Finelli, A.; Corr, K.; Chan, R.; Jokhu, S.; Li, X.; McCluskey, S.; Konukhova, A.; Hlasny, E.; van der Kwast, T.H.; et al. MRI-guided Focused Ultrasound Ablation for Localized Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer: Early Results of a Phase II Trial. Radiology 2021, 298, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polascik, T.J.; Mayes, J.M.; Sun, L.; Madden, J.F.; Moul, J.W.; Mouraviev, V. Pathologic stage T2a and T2b prostate cancer in the recent prostate-specific antigen era: implications for unilateral ablative therapy. Prostate 2008, 68, 1380–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.; Peters, M.; Shah, T.T.; van Son, M.; Tanaka, M.B.; Huber, P.M.; Lomas, D.; Rakauskas, A.; Miah, S.; Eldred-Evans, D.; et al. Cancer Control Outcomes Following Focal Therapy Using High-intensity Focused Ultrasound in 1379 Men with Nonmetastatic Prostate Cancer: A Multi-institute 15-year Experience. Eur Urol 2022, 81, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottet, N.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Cumberbatch, M.G.; De Santis, M.; Fanti, S.; Fossati, N.; Gandaglia, G.; Gillessen, S.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2020 Update. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur Urol 2021, 79, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Poel, H.G.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Cornford, P.; Govorov, A.; Henry, A.M.; Lam, T.B.; Mason, M.D.; Rouvière, O.; De Santis, M.; et al. Focal Therapy in Primary Localised Prostate Cancer: The European Association of Urology Position in 2018. Eur Urol 2018, 74, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, C.R.; Adewuyi, T.E.; Gray, J.; Hislop, J.; Shirley, M.D.; Jayakody, S.; MacLennan, G.; Fraser, C.; MacLennan, S.; Brazzelli, M.; et al. Ablative therapy for people with localised prostate cancer: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2015, 19, 1–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, G.; Ploussard, G.; Ost, P.; De Visschere, P.J.L.; Briganti, A.; Gandaglia, G.; Tilki, D.; Surcel, C.I.; Tsaur, I.; Van Den Bergh, R.C.N.; et al. Focal therapy in localised prostate cancer: Real-world urological perspective explored in a cross-sectional European survey. Urol Oncol 2018, 36, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amico, A.V.; Whittington, R.; Malkowicz, S.B.; Schultz, D.; Blank, K.; Broderick, G.A.; Tomaszewski, J.E.; Renshaw, A.A.; Kaplan, I.; Beard, C.J.; et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Jama 1998, 280, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkbey, B.; Rosenkrantz, A.B.; Haider, M.A.; Padhani, A.R.; Villeirs, G.; Macura, K.J.; Tempany, C.M.; Choyke, P.L.; Cornud, F.; Margolis, D.J.; et al. Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2. 1: 2019 Update of Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2. Eur Urol 2019, 76, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Hardenberg, J.; Westhoff, N.; Baumunk, D.; Hausmann, D.; Martini, T.; Marx, A.; Porubsky, S.; Schostak, M.; Michel, M.S.; Ritter, M. Prostate cancer treatment by the latest focal HIFU device with MRI/TRUS-fusion control biopsies: A prospective evaluation. Urol Oncol 2018, 36, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudenz, R. [A questionnaire with a new urge-score and stress-score for the evaluation of female urinary incontinence (author's transl)]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 1979, 39, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jenkinson, C.; Coulter, A.; Wright, L. Short form 36 (SF36) health survey questionnaire: normative data for adults of working age. Bmj 1993, 306, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; de Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; de Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, C.E.; Peters, M.; Guillaumier, S.; Arya, M.; Afzal, N.; Dudderidge, T.; Hosking-Jervis, F.; Hindley, R.G.; Lewi, H.; McCartan, N.; et al. Evaluation of functional outcomes after a second focal high-intensity focused ultrasonography (HIFU) procedure in men with primary localized, non-metastatic prostate cancer: results from the HIFU Evaluation and Assessment of Treatment (HEAT) registry. BJU Int 2020, 125, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bos, W.; Muller, B.G.; Ahmed, H.; Bangma, C.H.; Barret, E.; Crouzet, S.; Eggener, S.E.; Gill, I.S.; Joniau, S.; Kovacs, G.; et al. Focal therapy in prostate cancer: international multidisciplinary consensus on trial design. Eur Urol 2014, 65, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, L.; Arya, M.; Afzal, N.; Cathcart, P.; Charman, S.C.; Cornaby, A.; Hindley, R.G.; Lewi, H.; McCartan, N.; Moore, C.M.; et al. Medium-term Outcomes after Whole-gland High-intensity Focused Ultrasound for the Treatment of Nonmetastatic Prostate Cancer from a Multicentre Registry Cohort. Eur Urol 2016, 70, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, B.; Raess, E.; Schmid, F.A.; Bieri, U.; Scherer, T.P.; Elleisy, M.; Donati, O.F.; Rupp, N.J.; Moch, H.; Gorin, M.A.; et al. Focal therapy with high-intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer: 3-year outcomes from a prospective trial. BJU Int 2024, 133, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mala, K.S.; Plage, H.; Mödl, L.; Hofbauer, S.; Friedersdorff, F.; Schostak, M.; Miller, K.; Schlomm, T.; Cash, H. Follow-Up of Men Who Have Undergone Focal Therapy for Prostate Cancer with HIFU-A Real-World Experience. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Velthoven, R.; Aoun, F.; Marcelis, Q.; Albisinni, S.; Zanaty, M.; Lemort, M.; Peltier, A.; Limani, K. A prospective clinical trial of HIFU hemiablation for clinically localized prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2016, 19, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladjevardi, S.; Ebner, A.; Femic, A.; Huebner, N.A.; Shariat, S.F.; Kraler, S.; Kubik-Huch, R.A.; Ahlman, R.C.; Häggman, M.; Hefermehl, L.J. Focal high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy for localized prostate cancer: An interim analysis of the multinational FASST study. Eur J Clin Invest 2024, 54, e14192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.; Gebben, D.; Tarver, M.E.; Joyce Lee, T.H.; Wang, S.; Siddiqui, M.M.; Sonn, G.A.; Viviano, C.J. Patient Preferences for Benefit and Risk Associated With High Intensity Focused Ultrasound for the Ablation of Prostate Tissue in Men With Localized Prostate Cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2024, 22, 102113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madersbacher, S.; Kratzik, C.; Szabo, N.; Susani, M.; Vingers, L.; Marberger, M. Tissue ablation in benign prostatic hyperplasia with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Eur Urol 1993, 23 Suppl 1, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearini, L.; Nunzi, E.; Giovannozzi, S.; Lepri, L.; Lolli, C.; Giannantoni, A. Urodynamic evaluation after high-intensity focused ultrasound for patients with prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer 2014, 2014, 462153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duwe, G.; Boehm, K.; Haack, M.; Sparwasser, P.; Brandt, M.P.; Mager, R.; Tsaur, I.; Haferkamp, A.; Hofner, T. Single-center, prospective phase 2 trial of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) in patients with unilateral localized prostate cancer: good functional results but oncologically not as safe as expected. World J Urol 2023, 41, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziglioli, F.; Baciarello, M.; Maspero, G.; Bellini, V.; Bocchialini, T.; Cavalieri, D.; Bignami, E.G.; Maestroni, U. Oncologic outcome, side effects and comorbidity of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for localized prostate cancer. A review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2020, 56, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivas, N.; Eberli, D.; van der Poel, H. How Sound Are High-intensity Focused Ultrasound Data? Eur Urol 2025, 87, 534–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).