1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common non-skin cancer in men and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in men [

1]. Treatment options for PCa, including proton beam and intensity-modulated radiation therapy, robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy, irreversible electroporation, photodynamic therapy, primary cryotherapy, focal laser ablation, and active surveillance, are extensive and continue to advance [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Among these, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation has emerged as a promising treatment option.

In 2015, the Food and Drug Administration approved HIFU for prostatic tissue ablation in the United States. Since then, studies have demonstrated that HIFU achieves oncologic and functional outcomes comparable to standard-of-care treatments for localized prostate cancer, such as radical prostatectomy and radiation therapy [

8,

9,

10]. Similarly, the use of HIFU in primary whole-gland PCa management has proven to yield satisfactory cancer control with minimal side effects [

11]. A recent prospective trial examining the 3-year outcomes of focal HIFU treatment for low-to-intermediate-risk PCa reported favorable functional outcomes, preservation of quality of life, minimal adverse events, and a low incidence of treatment failure [

12]. These findings are further supported by a phase two clinical trial that demonstrated HIFU’s efficacy as a treatment option for men with intermediate-risk PCa [

13]. Given its strong oncological control rates, excellent functional outcomes, and preservation of quality of life, HIFU is becoming increasingly recognized as a compelling option for focal treatment of PCa in both the primary and salvage settings [

14].

HIFU is also effective in the salvage setting for the management of radiation failure. [

8,

15,

16]. A meta-regression analysis found no significant difference in oncologic outcomes between Salvage Radical Prostatectomy (SRP) and Salvage High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (SHIFU) cohorts. However, patients treated with SRP experienced a higher incidence of incontinence compared to those treated with SHIFU [

5].

HIFU is non-invasive and delivers precise, highly localized ablative therapy, offering unique advantages, particularly to those with higher comorbidity indices, a history of abdominal surgery, or recurrent localized prostate cancer. These attributes make HIFU especially promising for the veteran population, which often has more complex medical needs due to various service-related exposures, patient characteristics, and higher average comorbidity burden [

17].

Despite these potential benefits, there is a lack of data regarding HIFU treatment outcomes for localized prostate cancer in the veteran population. Hence, we aim to report oncologic, complication, and functional outcomes after primary and salvage HIFU for localized prostate cancer in the Veteran population. To our knowledge, this paper presents the initial and largest United States retrospective case series of HIFU use for primary and salvage treatment of localized prostate cancer in veterans.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was a retrospective analysis approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) to evaluate outcomes for patients who underwent HIFU at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center between 2018 and 2022. Data was acquired from electronic medical records, including demographic and clinical information, with patient comorbidities assessed using the Charlson-Comorbidity Index.

The primary endpoints of this study were oncologic outcomes, measured using prostate-specific antigen (PSA) metrics: baseline PSA, PSA nadir, and percentage PSA decrease after ablation. Treatment failure was defined as persistent in-field tumor visualized on prostate MRI. Local recurrence was determined by biopsy-proven prostate cancer in the prostatic bed. Post-HIFU treatments, including salvage therapy, were also documented.

The secondary endpoints were functional outcomes assessed through questionnaires. Sexual function was evaluated using the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM), and urinary function was measured using the American Urological Association Symptom Score (AUASS), uroflowmetry, and post-void residual measurement.

All complications occurring 30 days following HIFU treatment were recorded and categorized according to the Clavien-Dindo classification system.

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 15. The percent reduction in PSA from baseline was calculated using the formula: [(Initial PSA – PSA at post-ablation month)/Initial PSA]. These reductions were compared across follow-up time points using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for both primary and salvage therapy groups. Changes in functional outcomes were assessed by comparing pre- and post-HIFU AUASS and SHIM scores using paired t-tests. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

During the study time frame of 2018-2022, 52 veterans were treated with HIFU, of which 43 had sufficient follow-up data to be included in our study. Of these, 31 patients (72.1%) received primary treatment for localized prostate cancer, and 12 patients (27.9%) received salvage therapy for localized recurrence after radiation therapy.

The baseline characteristics for this cohort are outlined in

Table 1. The median (IQR) Charlson-Comorbidity Index (CCI) was 7 for the primary treatment group and 5 for the salvage group. High-risk PCa was observed in 11 patients (35.5%) from the primary treatment group and 7 patients (58.3%) from the salvage group. All patients in the salvage group had previously undergone radiation therapy, and one had also received hormonal therapy as part of their primary treatment.

The median follow-up period was 23 months for the primary group and 25 months for the salvage group. The post-HIFU oncologic outcomes are detailed in

Table 2. The median PSA nadir was 0.16 ng/ml for the primary group and 0.12 ng/ml for the salvage groups. The median time to reach PSA nadir was 6 months in the primary group and 3 months in the salvage group. The median percent decrease in PSA over the follow-up period was 96% for the primary group and 98% for the salvage group. Local recurrence, identified by prostate MRI or post-ablation biopsy, was observed in five patients (16.1%) from the primary therapy group and two patients (16.6%) from the salvage therapy group.

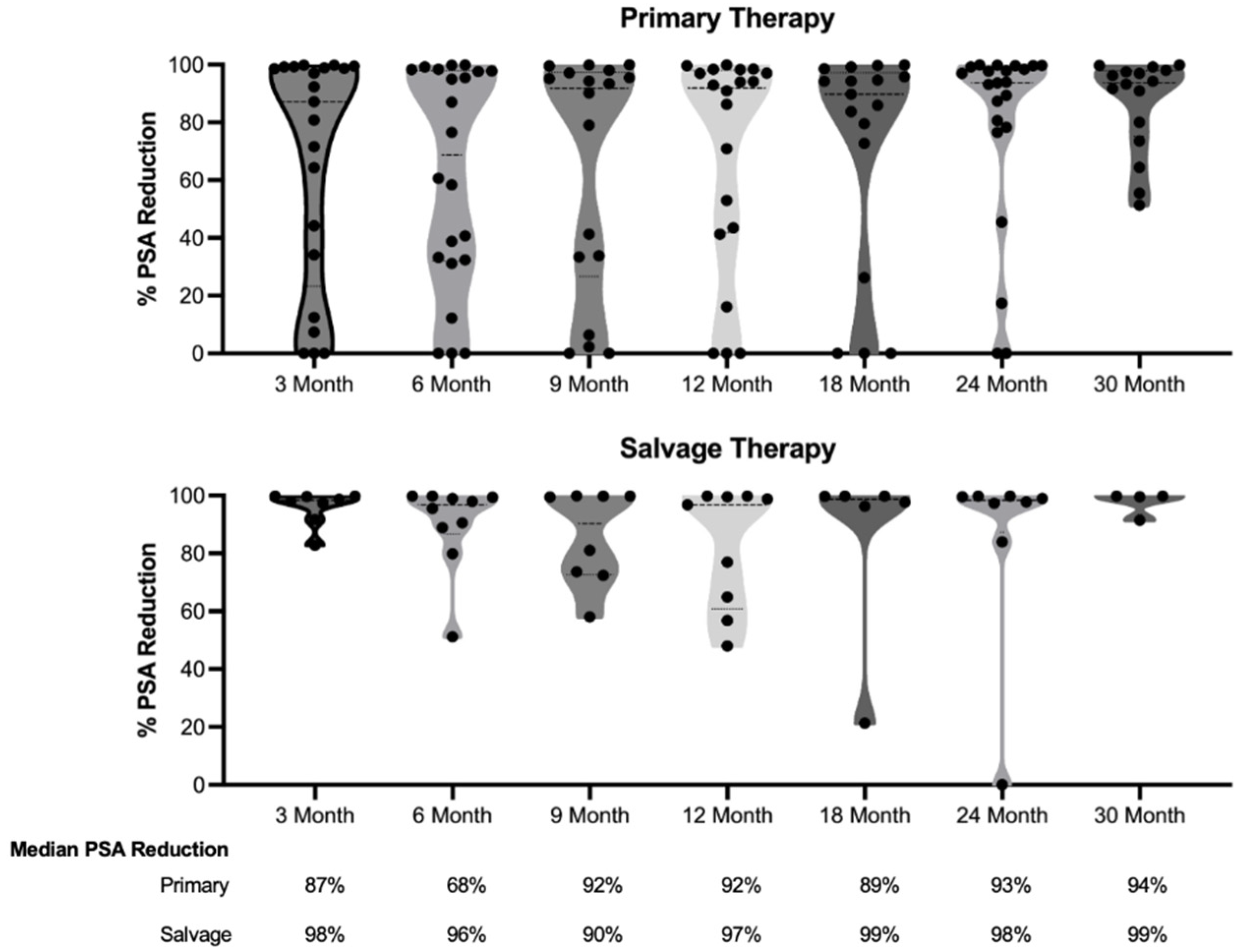

Figure 1 illustrates the reduction in PSA levels over a 30-month follow-up period for both the primary and salvage therapy groups. After the initial decrease measured 3 months post-therapy, there was no statistically significant change in PSA levels during the follow-up period for either group (P= 0.3553 for the primary group and P= 0.8057 for the salvage therapy group).

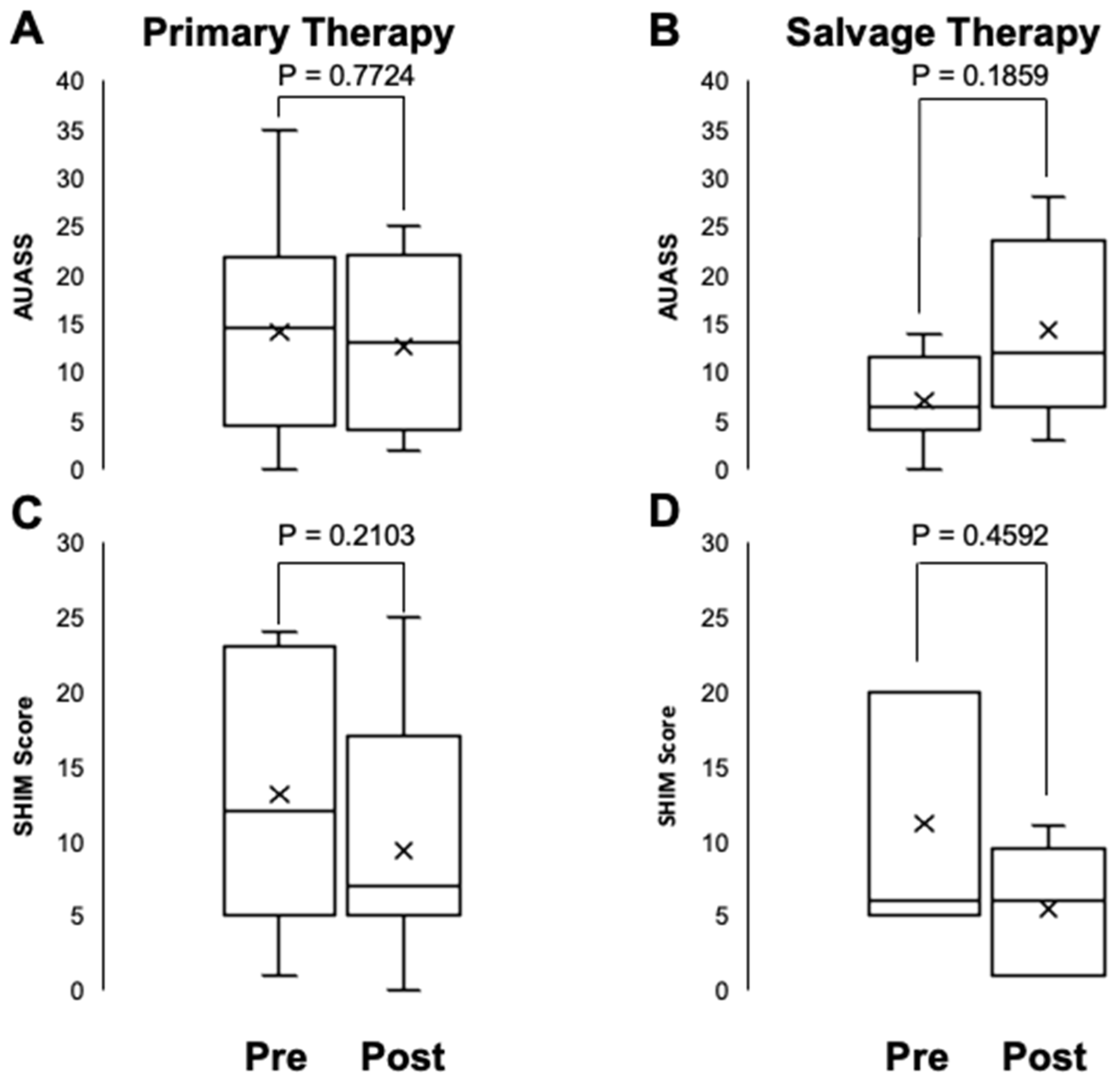

Patient-reported urinary and sexual function were evaluated using the American Urological Association Symptom Score (AUASS) and the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM).

Figure 2 displays the AUASS and SHIM scores before and after HIFU ablation for PCa. There were no statistically significant differences in AUASS or SHIM scores before and after HIFU therapy for either group (P= 0.2103 and 0.7724, respectively for the primary therapy group, and P= 0.4592 and 0.1859, respectively, for salvage therapy group).

Regarding complications, 2 patients (6.5%) from the primary treatment group experienced 30-day complications, including one case of epididymo-orchitis and one case of urethral stricture, which was managed with clinic urethral dilation. 3 patients (25%) from the salvage treatment group experienced 30-day complications, including one bladder neck contracture, which required surgical incision of the bladder neck, one urethral stricture, and one case of epididymo-orchitis.

4. Discussion

Our retrospective review presents encouraging early and intermediate outcomes for both primary and salvage HIFU treatment of localized prostate cancer in a veteran population. The results demonstrate that HIFU can achieve significant PSA reduction, with median decreases of 96% and 98%, in the primary and salvage therapy groups, respectively. These reductions remained stable over the 30-month follow-up period. Notably, HIFU appeared to preserve urinary and sexual function, as indicated by the lack of statistically significant changes in AUASS or SHIM scores post-treatment.

These findings align favorably with the 3-year outcomes of a recent study by Kaufmann et al., which reported excellent functional outcomes using focal HIFU ablation to treat PCa [

12]. However, in their study of 91 patients, 21% experienced worsening erectile function, suggesting potential long-term declines in men’s sexual function and quality of life. Alternatively, this disparity may reflect the advancements in HIFU technology or technique. Supporting this interpretation, a phase 2 clinical trial of MRI-guided HIFU therapy for intermediate-risk PCa conducted by Ghai et al. demonstrated no significant changes in erectile function. Additionally, among the 44 patients with clinically significant PCa (GG ≥ 2) in their study, 91% of patients had no clinically significant PCa and 84% had no cancer at all 2 years post-treatment [

13]. While local recurrence was observed in approximately 16% of patients in both groups, the overall complication rates were relatively low, particularly for the primary HIFU group. This aligns with findings from a prospective multicenter study of 98 men, in which 35.7% of patients reported adverse events, such as urinary tract infection or urinary retention, following HIFU treatment [

18,

19]. Overall, our findings suggest that HIFU may offer a viable treatment option for veterans with localized prostate cancer, including those with high-risk disease or those requiring salvage therapy.

A key finding of our study is the comparable efficacy of HIFU in both primary and salvage settings. Despite the inherent challenges of treating patients who have undergone previous radiation therapy, the salvage group achieved similar PSA reduction percentages and local recurrence rates to the primary HIFU group. This is particularly noteworthy given that the salvage group had a higher proportion of high-risk prostate cancer cases (58.3% vs 35.5% in the primary group). These results align with findings from a larger multicenter study by Crouzet et al., which reported promising outcomes for salvage HIFU after failed external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) [

20]. Their study of 418 patients showed 7-year cancer-specific and metastasis-free survival rates of over 80%. Notably, while Crouzet et al. reported significant morbidity, particularly in earlier cases, our study found a lower complication rate of 25% in the salvage group. This suggests that advancements in HIFU technology and technique may be improving the safety profile of salvage HIFU. These results collectively suggest that HIFU may be an effective option for patients who have failed primary radiation therapy, offering a less invasive alternative to salvage radical prostatectomy, with the potential for lower morbidity than previously reported.

The PSA kinetics observed in our study provide valuable insights into the oncological response to HIFU treatment. The median time to PSA nadir was shorter in the salvage group (3 months) compared to the primary group (6 months), which may reflect differences in prostate tissue composition and vascularity following prior radiation therapy. These findings are broadly consistent with a systematic review by Huang et al., which analyzed 27 studies encompassing 7393 patients [

21]. Their review reported mean times to PSA nadir of 2.4 to 5.4 months for whole-gland HIFU and 5.7 to 7.3 months for partial-gland HIFU. Our observed nadir times fall within these ranges, suggesting our results are in line with the broader literature. However, our study found lower PSA nadirs (median 0.16 ng/mL for primary and 0.12 ng/mL for salvage) compared to the systematic review’s reported means of 0.4 to 1.95 ng/mL for whole-gland and 1.9 to 2.7 ng/mL for partial-gland HIFU. This difference might be attributed to variations in patient populations, HIFU techniques, or the inclusion of salvage treatments in our study. The stability of PSA reduction over our 30-month follow-up period is encouraging, suggesting durable oncological control in the short to medium term. This contrasts with the wide range of positive biopsy rates (4.5% to 91.1% for whole-gland and 14% to 37.5% for partial-gland HIFU) reported in the systematic review, highlighting the need for standardized follow-up protocols and longer-term data. While our results are promising, longer-term follow-up will be essential to confirm the sustainability of these results and to better understand how our outcomes compare to those reported in larger, multi-institutional studies.

The differential in complication rates between primary and salvage HIFU (6.5% vs 25%, respectively) warrants discussion. The higher rate of complications in the salvage group is expected due to the challenges of treating previously irradiated tissue [

22]. Nonetheless, it is important to note that, in our study, most of these complications were low-grade and easily manageable with conservative measures or minor interventions. The lower complication rate in the primary group underscores HIFU’s potential as a first-line treatment option, particularly for patients who may not be ideal candidates for more invasive therapies.

The application of HIFU in a veteran population is of particular interest. Veterans often present with more complex medical conditions and a higher burden of comorbidities compared to the general population [

17,

23]. The median CCI in our primary HIFU group was 7, indicating a significant comorbidity burden. Despite this, the treatment was well-tolerated, with acceptable complication rates.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The follow-up period (median 23-25 months) is relatively short, particularly for assessing long-term oncological outcomes in PCa. Additionally, the sample size, while substantial for an initial series, is still modest, especially for the salvage therapy group. Larger, multi-center studies with longer follow-up will be necessary to confirm and extend our findings. Despite these limitations, our results have important implications for clinical practice. HIFU appears to be a viable option for both primary and salvage therapy in veterans with localized prostate cancer. The preservation of functional outcomes, coupled with acceptable oncological control, makes it an attractive alternative to more invasive treatments, particularly for patients with significant comorbidities or those seeking to avoid the side effects associated with radical therapies.

Long-term follow-up data will be crucial to establish the durability of oncological control and functional preservation. Larger studies comparing HIFU to other treatment modalities in veteran populations would provide valuable comparative effectiveness data. Furthermore, research into predictive factors for HIFU success or failure could help refine patient selection criteria and improve outcomes.

Another limitation of HIFU, compared to other focal therapy options, e.g., cryotherapy, urethral-based focused ultrasound, transperineal laser ablation, etc. is the inability to treat cancers in the anterior prostate of large glands, > 4 cm in Anterior-Posterior height, due to the maximum focal length of the treatment transducer. Addressing this limitation through advancements in technology could broaden the applicability of HIFU.

5. Conclusions

Our review demonstrates that HIFU is a promising treatment option for localized prostate cancer in veterans, showing effectiveness in both primary and salvage therapy settings. The combination of significant PSA reduction, preservation of urinary and sexual function, and acceptable complication rates supports the continued exploration and refinement of this technique. As we accumulate more long-term data and experience, HIFU may become an increasingly important tool in our armamentarium against prostate cancer, offering veterans a less invasive option that balances oncological control with quality-of-life preservation

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J., N.S.; methodology, A.A., S.P.; validation, G.S., B.F.; formal analysis, S.P., J.S., J.T..; data curation, A.A., S.P., N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., G.S.; writing—review and editing, A.A., G.S.; B.F. J.S.; supervision, J.J., N.S.; project administration, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board protocol # H-52700 approved February 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

The retrospective outcomes review did not require prospective informed consent to be obtained in order to review de-identified quality outcomes data.

Data Availability Statement

A raw complete dataset is not readily available due to concern for confidentiality, however a limited de-attributed dataset could be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Micheal Brooks MD was contributory in early HIFU surgeries and outcomes data acquisition, Frank Velasquez and Haarika Gudlavalleti contributed by filing IRB documents, and support from the Prostate Cancer Foundation- VALOR Challenge Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J Clinicians. 2023;73(1):17-48. [CrossRef]

- Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR. Trends in Management for Patients With Localized Prostate Cancer, 1990-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(1):80. [CrossRef]

- Williams, Thomas R., Tavya G. R. Benjamin, Michael J. Schwartz, & Ardeshir R. Rastinehad. “Narrative review—focal therapy: are we ready to change the prostate cancer treatment paradigm?.” Annals of Translational Medicine [Online], 11.1 (2023): 24.

- Ong, S.; Leonardo, M.; Chengodu, T.; Bagguley, D.; Lawrentschuk, N. Irreversible Electroporation for Prostate Cancer. Life 2021, 11, 490. Author 1, A.B. (University, City, State, Country); Author 2, C. (Institute, City, State, Country). Personal communication, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, Rengarajan, et al. “Clinical Development of Photodynamic Agents and Therapeutic Applications.” Biomaterials Research, vol. 22, no. 1, 26 Sept. 2018, Author 1, A.B. Title of Thesis. Level of Thesis, Degree-Granting University, Location of University, Date of Completion. [CrossRef]

- Jung JH, Risk MC, Goldfarb R, Reddy B, Coles B, Dahm P. Primary cryotherapy for localised or locally advanced prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 May 30;5(5):CD005010. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Luijtelaar, A., Greenwood, B.M., Ahmed, H.U. et al. Focal laser ablation as clinical treatment of prostate cancer: report from a Delphi consensus project. World J Urol 37, 2147–2153 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Philippou Y, Parker RA, Volanis D, Gnanapragasam VJ. Comparative Oncologic and Toxicity Outcomes of Salvage Radical Prostatectomy Versus Nonsurgical Therapies for Radiorecurrent Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Regression Analysis. Eur Urol Focus. 2016 Jun;2(2):158-171. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle LF, Lehrer EJ, Markovic D, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Local Salvage Therapies After Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer (MASTER). European Urology. 2021;80(3):280-292. [CrossRef]

- Hopstaken JS, Bomers JGR, Sedelaar MJP, Valerio M, Fütterer JJ, Rovers MM. An Updated Systematic Review on Focal Therapy in Localized Prostate Cancer: What Has Changed over the Past 5 Years? European Urology. 2022;81(1):5-33. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, L., Arya, M., Afzal, N., Cathcart, P., Charman, S. C., Cornaby, A., Hindley, R. G., Lewi, H., McCartan, N., Moore, C. M., Nathan, S., Ogden, C., Persad, R., van der Meulen, J., Weir, S., Emberton, M., & Ahmed, H. U. (2016). Medium-term Outcomes after Whole-gland High-intensity Focused Ultrasound for the Treatment of Nonmetastatic Prostate Cancer from a Multicentre Registry Cohort. European urology, 70(4), 668–674. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, B. Kaufmann, B., Raess, E., Schmid, F.A., Bieri, U., Scherer, T.P., Elleisy, M., Donati, O.F., Rupp, N.J., Moch, H., Gorin, M.A., Mortezavi, A. and Eberli, D. (2024), Focal therapy with high-intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer: 3-year outcomes from a prospective trial. BJU Int, 133: 413-424. [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Finelli, A.; Corr, K.; Lajkosz, K.; McCluskey, S.; Chan, R.; Gertner, M.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Incze, P.F.; Zlotta, A.R.; et al. MRI-Guided Focused Ultrasound Focal Therapy for Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer: Final Results from a 2-Year Phase II Clinical Trial. Radiology 2024, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraj Y, Falkenbach F, Veleva V, Pose RM, Ekrutt J, Abrams-Pompe R, et al. MP73-02 FOCAL THERAPY - 7 YEARS EXPERIENCE WITH FOCAL HIGH INTENSITY FOCUSED ULTRASOUND IN 164 PATIENTS WITH PROSTATE CANCER: SINGLE CENTER RESULTS. Journal of Urology. 2023 Apr 1;209(Supplement 4):e1034. [CrossRef]

- Hill CR, Ter Haar GR. High intensity focused ultrasound—potential for cancer treatment. The British Journal of Radiology. 1995;68(816):1296-1303. [CrossRef]

- Sundaram K, Chang S, Penson D, Arora S. Therapeutic Ultrasound and Prostate Cancer. Semin intervent Radiol. 2017;34(02):187-200. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Patel, S.; Gaitonde, K.; Greene, K.; Liao, J.C.; McWilliams, G.; Sawyer, M.; Schroeck, F.; Alrabaa, A.; Saffati, G.; et al. The Management of Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer in a Veteran Patient Population: Issues and Recommendations. Current Oncology 2024, 31, 6686–6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid FA, Schindele D, Mortezavi A, Spitznagel T, Sulser T, Schostak M, Eberli D. Prospective multicentre study using high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for the focal treatment of prostate cancer: Safety outcomes and complications. Urol Oncol 2020; 38(4):225–230.

- Basseri, S., Perlis, N. & Ghai, S. Focal therapy for prostate cancer. Abdom Radiol (2024). [CrossRef]

- Crouzet S, Blana A, Murat FJ, et al. Salvage high-intensity focused ultrasound ( HIFU ) for locally recurrent prostate cancer after failed radiation therapy: Multi-institutional analysis of 418 patients. BJU International. 2017;119(6):896-904. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Tan P, He M, et al. The primary treatment of prostate cancer with high-intensity focused ultrasound: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(41):e22610. [CrossRef]

- Autran-Gomez AM, Scarpa RM, Chin J. High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound and Cryotherapy as Salvage Treatment in Local Radio-Recurrent Prostate Cancer. Urol Int. 2012;89(4):373-379. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez KM, Venkat A, Elbers DC, et al. Prostate cancer patient stratification by molecular signatures in the Veterans Precision Oncology Data Commons. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2023;9(4):a006298. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).