Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Toxin accumulation. Insufficient CYP activity can lead to a slower metabolism of toxic substances, contributing to their accumulation in the liver and the development of hepatopathies.

- Oxidative stress: CYPOR and CYP are involved in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Disruptions in their function can lead to increased ROS formation, which causes oxidative stress and liver cell damage.

- Inflammatory processes: Metabolic products formed with the participation of CYP can cause inflammatory reactions that contribute to the development of hepatopathies.

- To study the ecological state of the reservoir and coastal zone to assess the fish habitat.

- To conduct hematological studies of the fish to assess their clinical status.

- To conduct a bacteriological and histological examination of the fish in order to assess their clinical status.

- To determine CYPOR levels and draw conclusions about the impact of the habitat on them.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hematological Examination

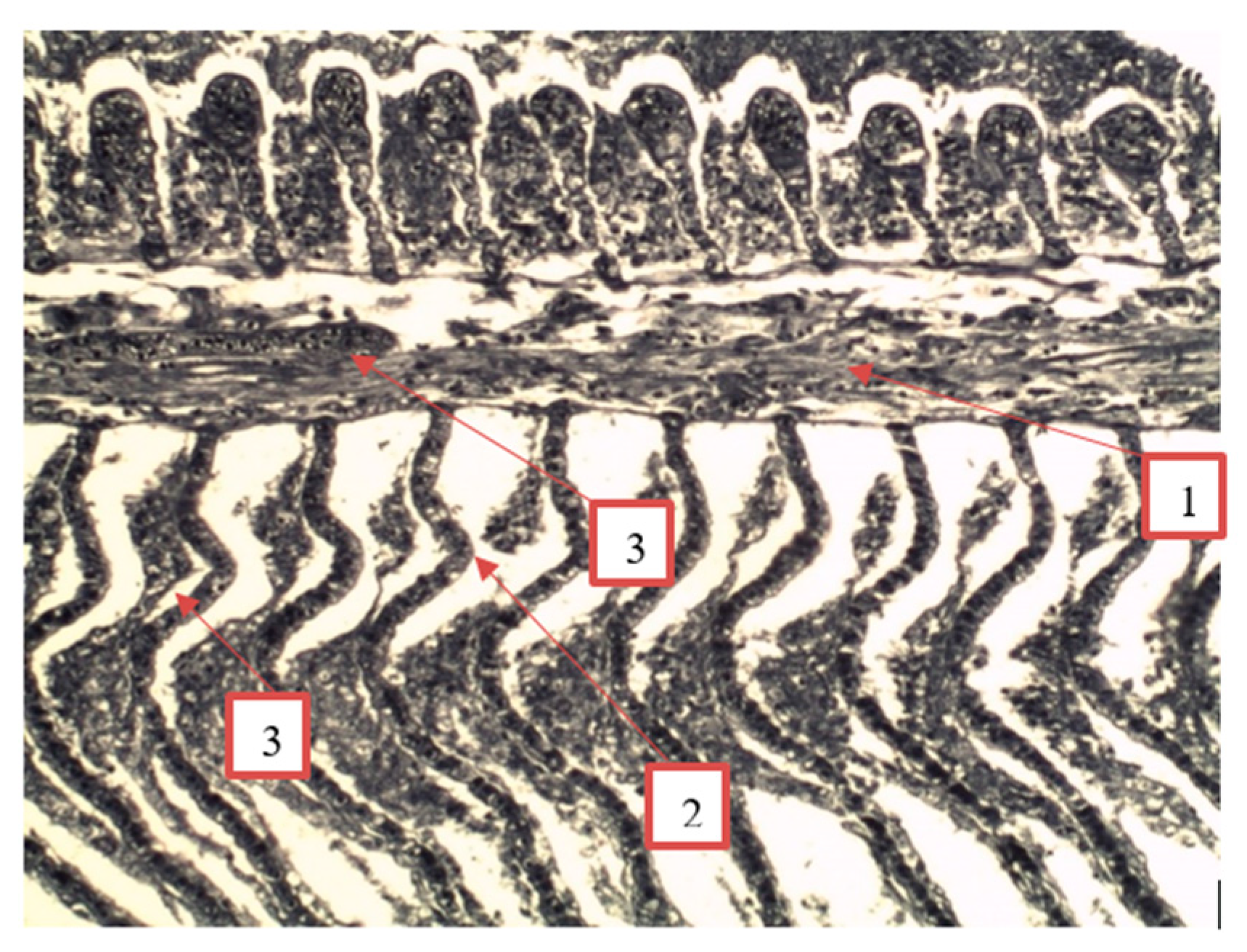

2.2. Bacteriological and Histological Studies

2.3. Studies to Determine CYPOR Concentrations in Liver Homogenates

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

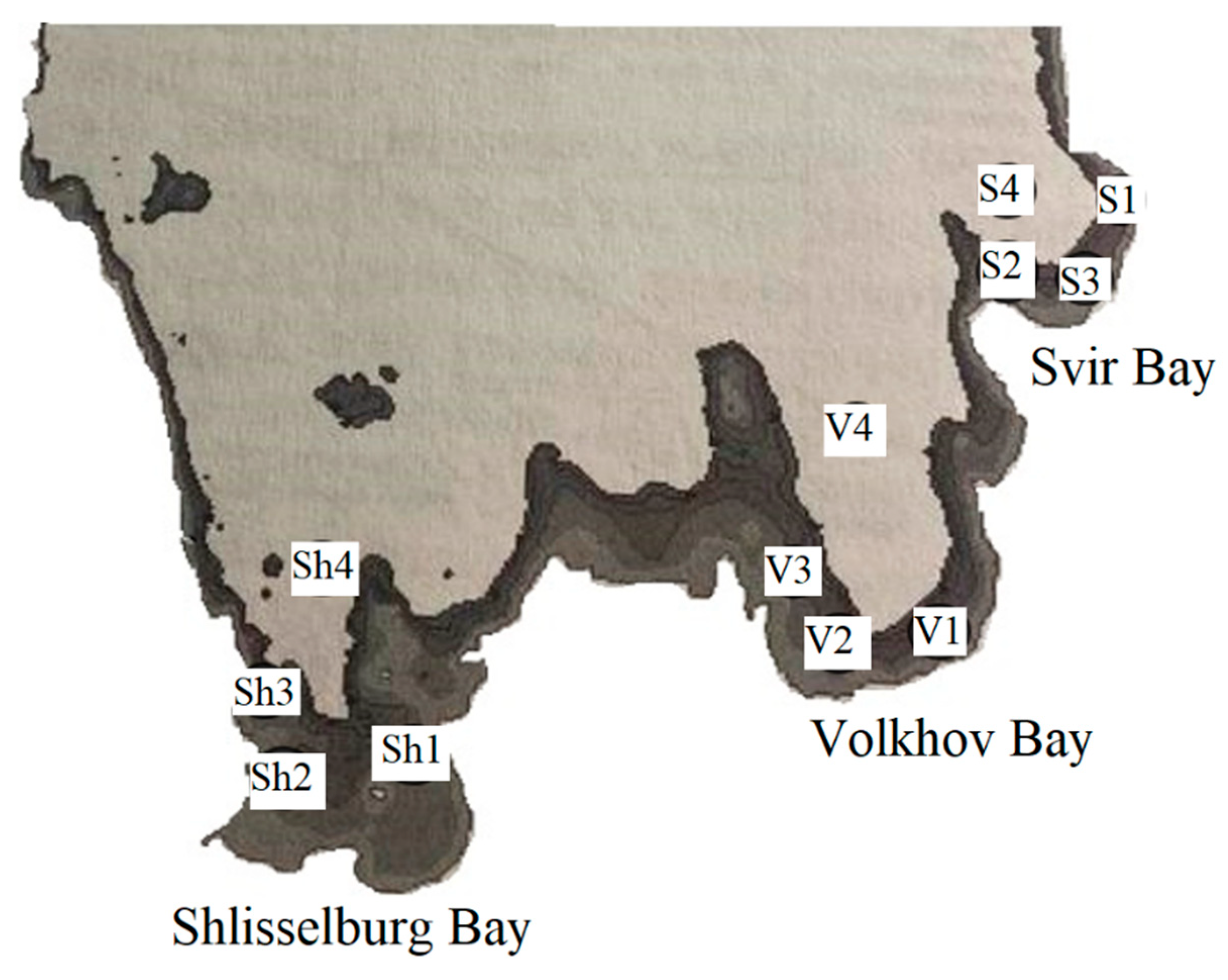

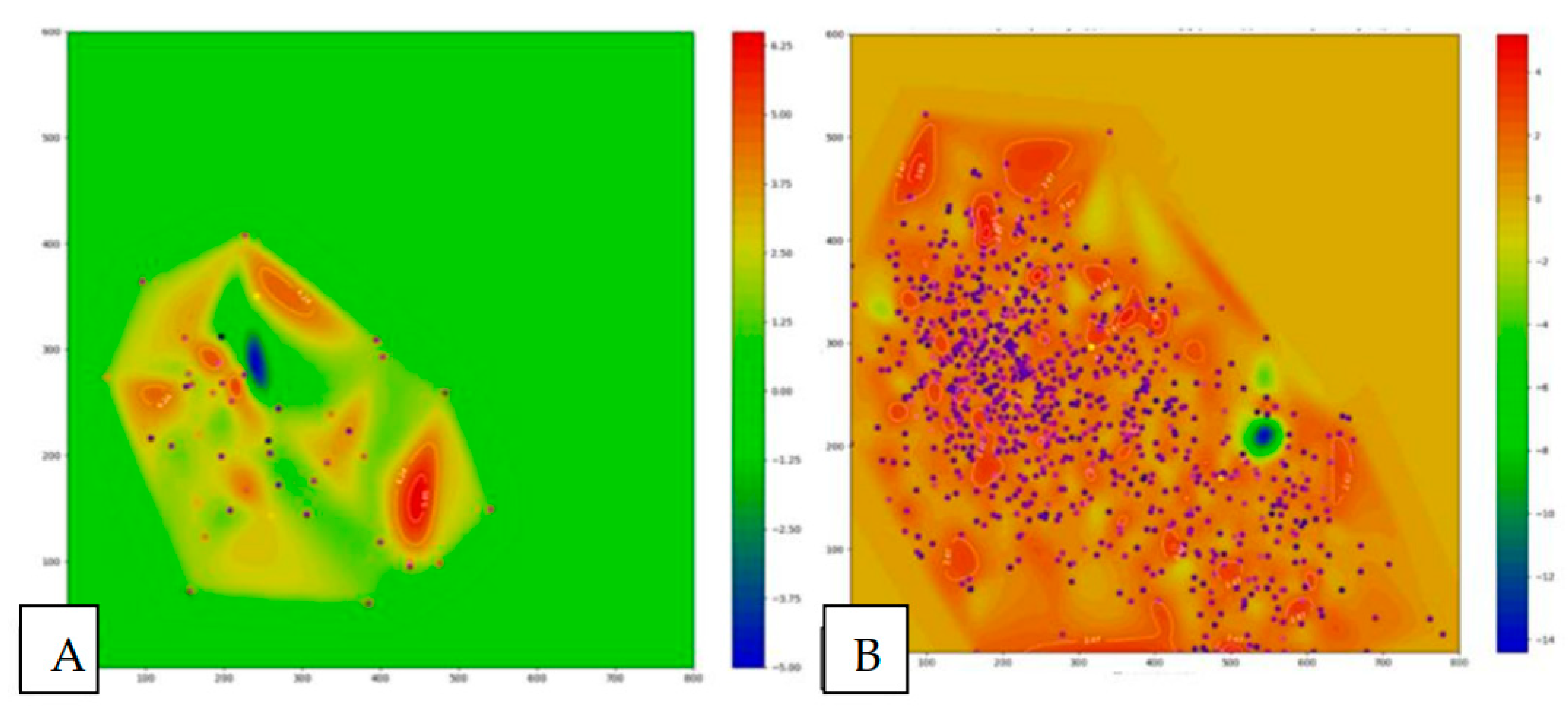

3.1. Ecological Status

3.2. Bacteriological Examination

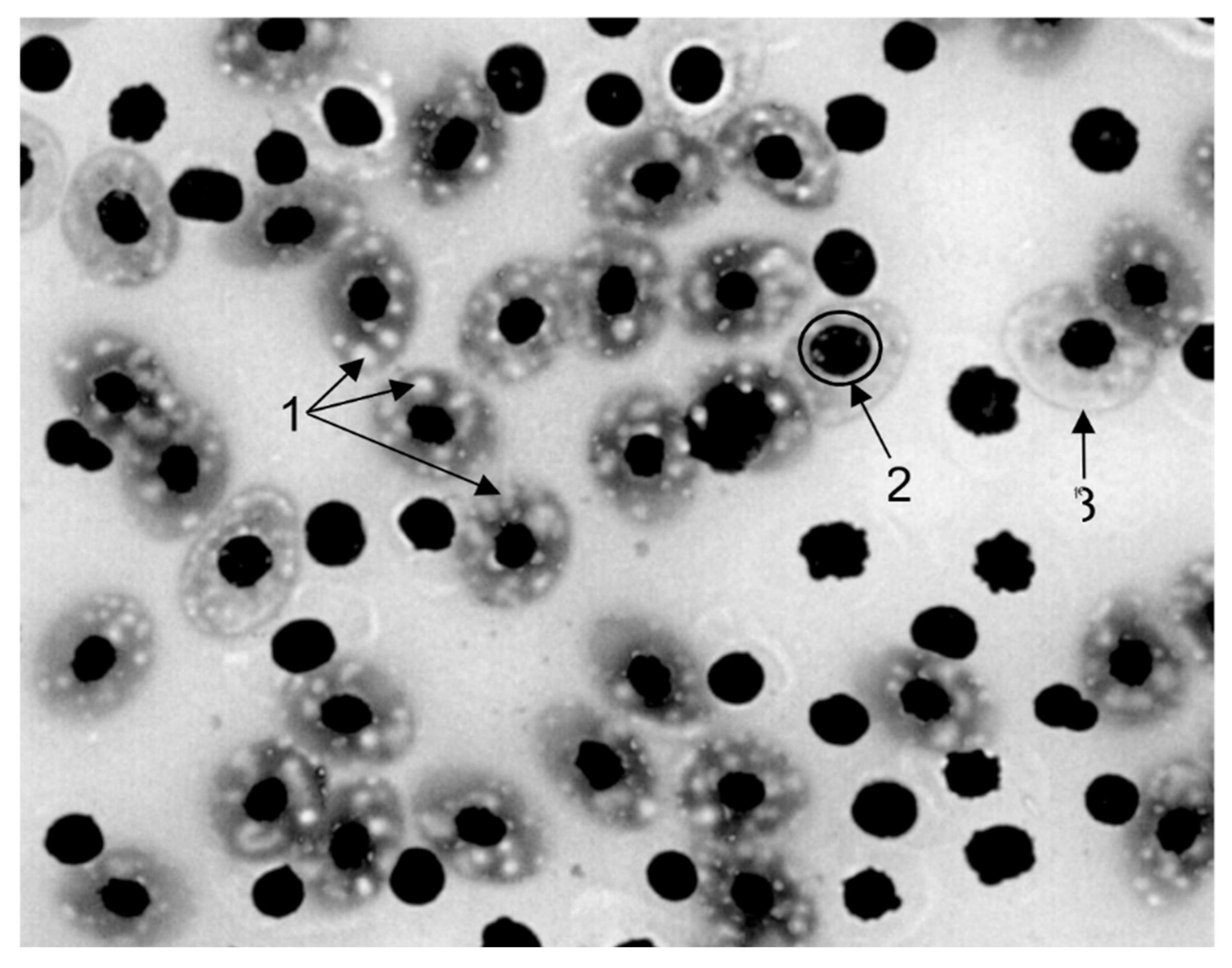

3.3. Hematological Examination

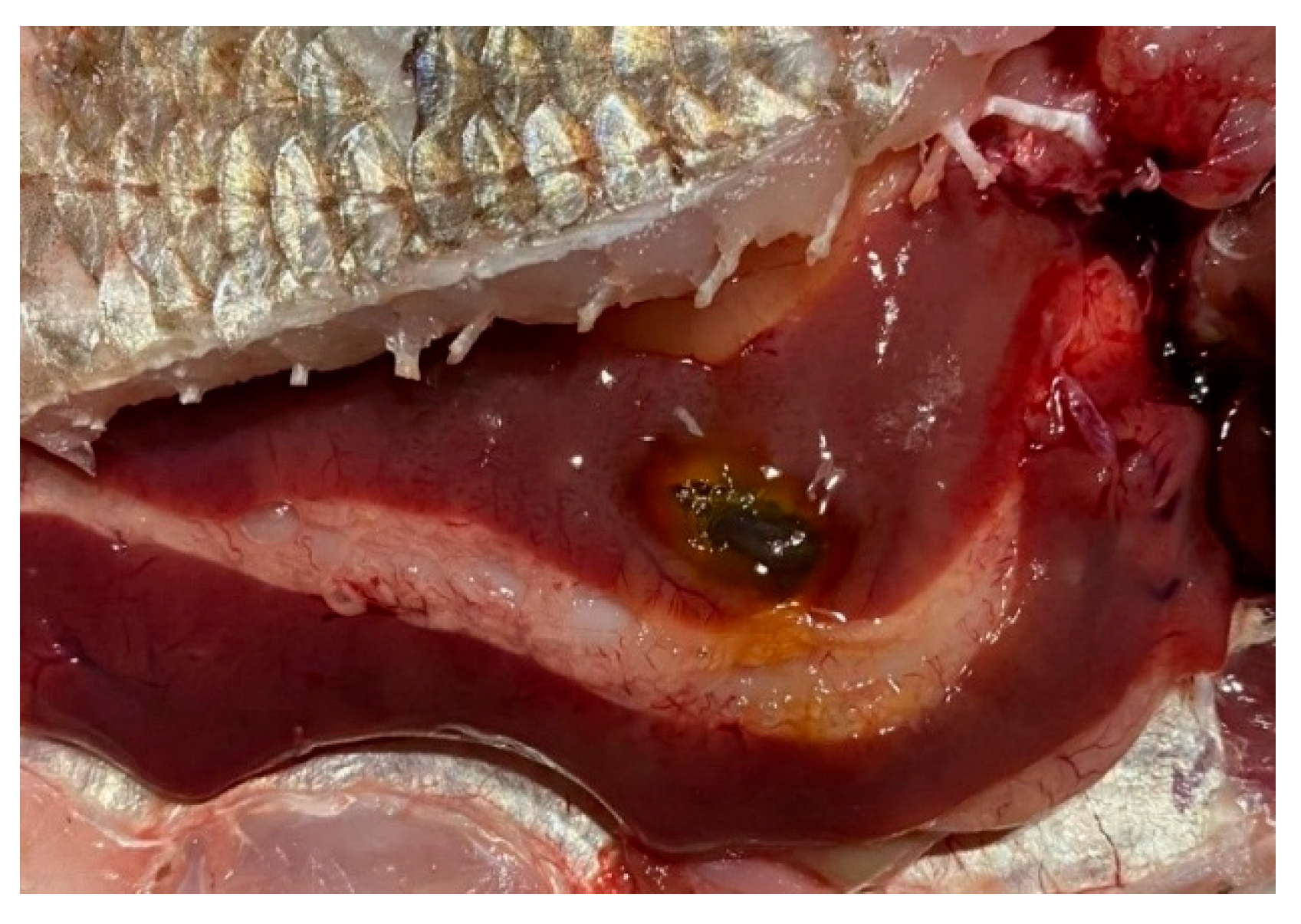

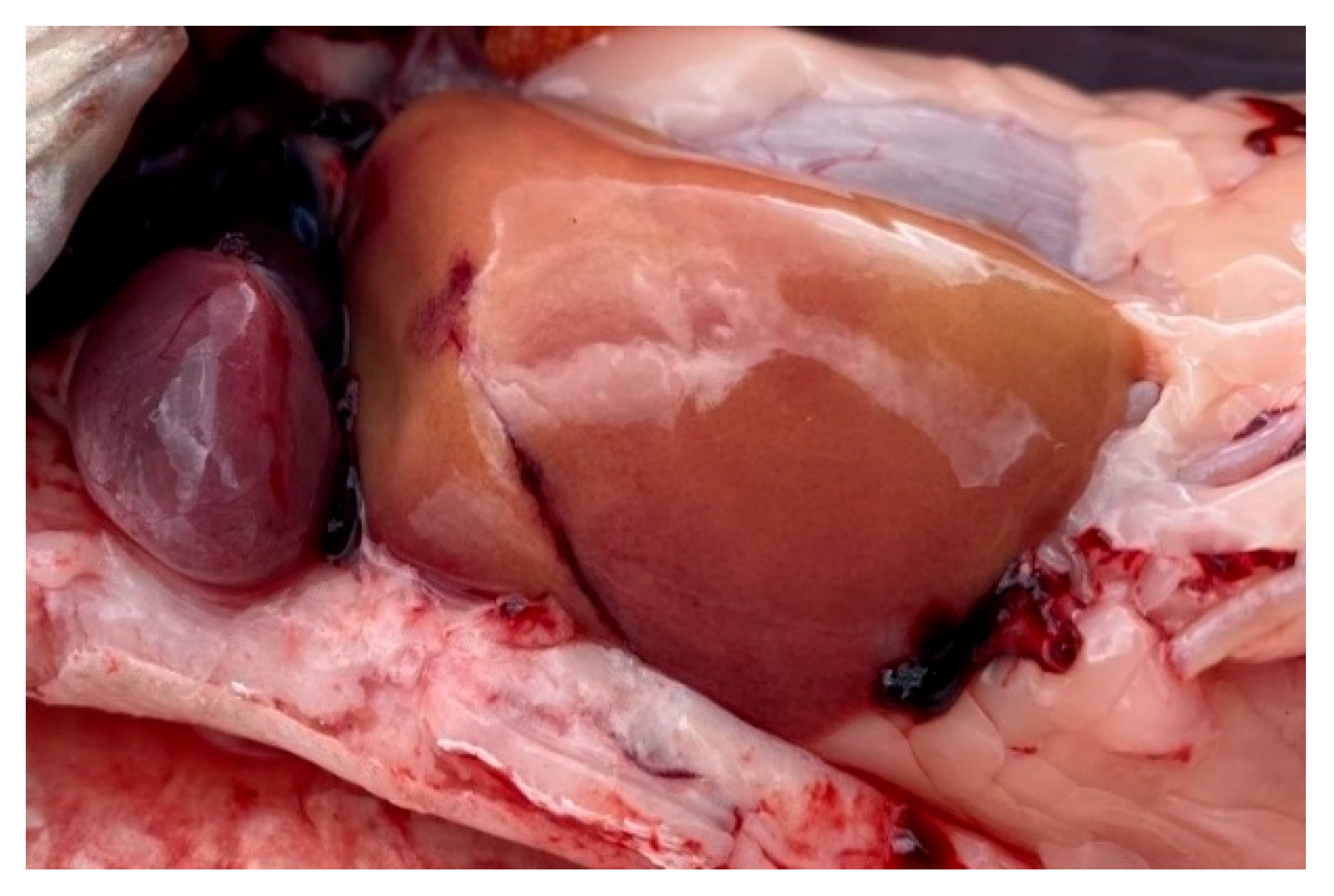

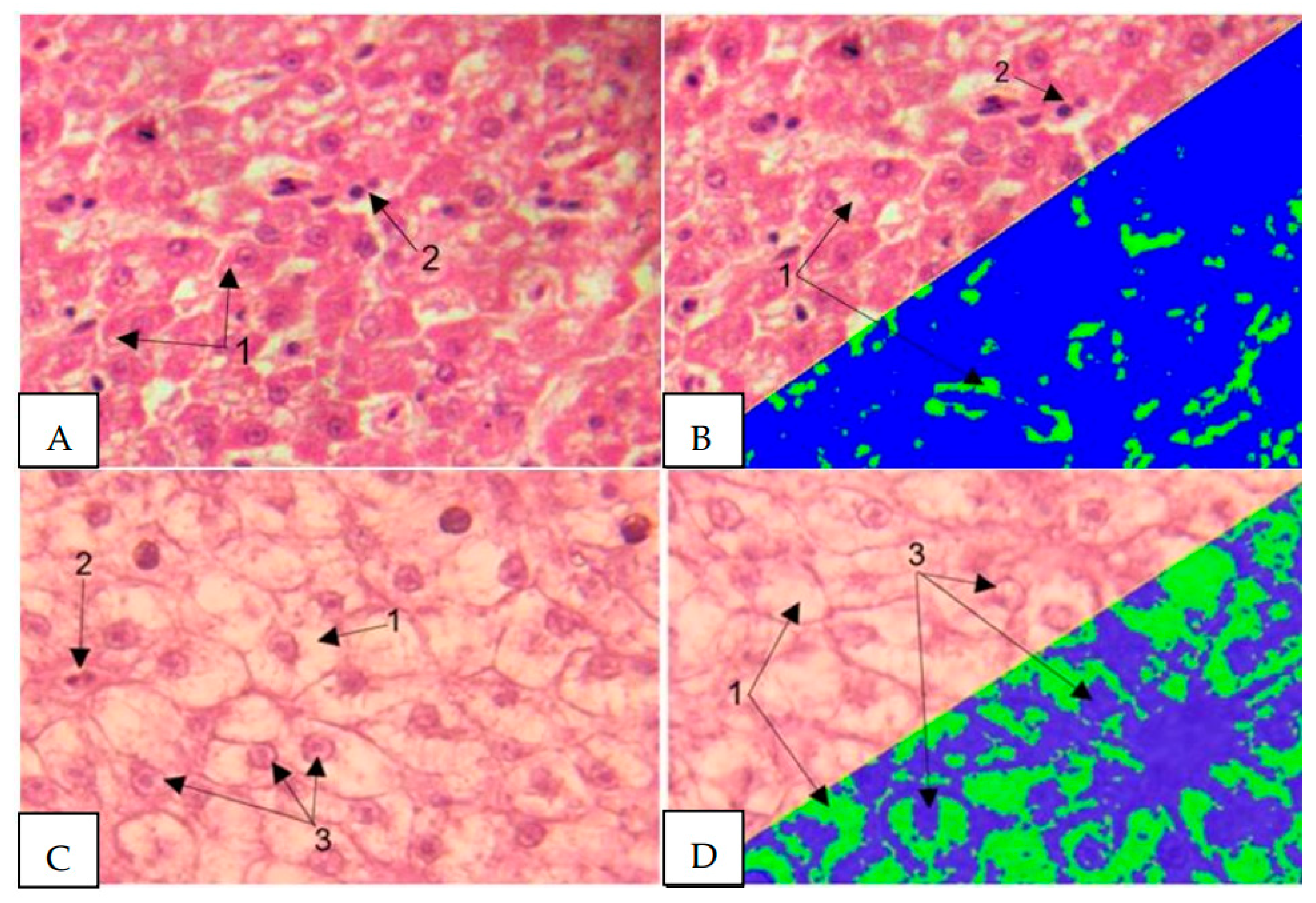

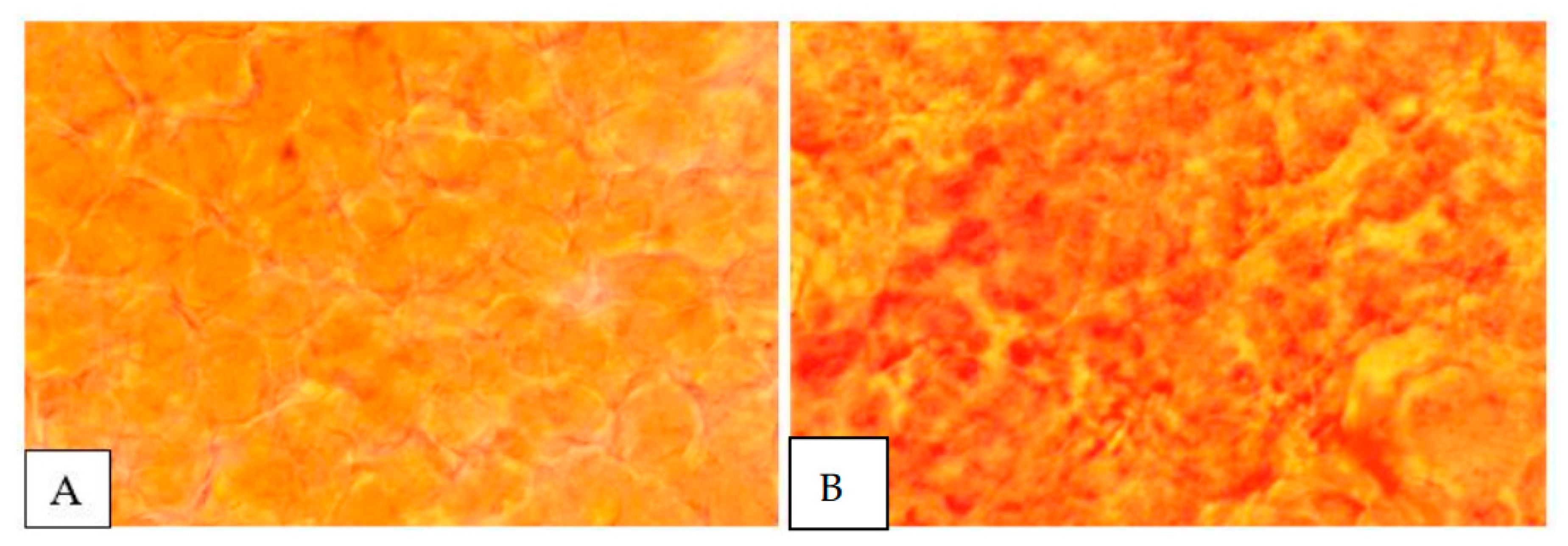

3.4. Histological Examination

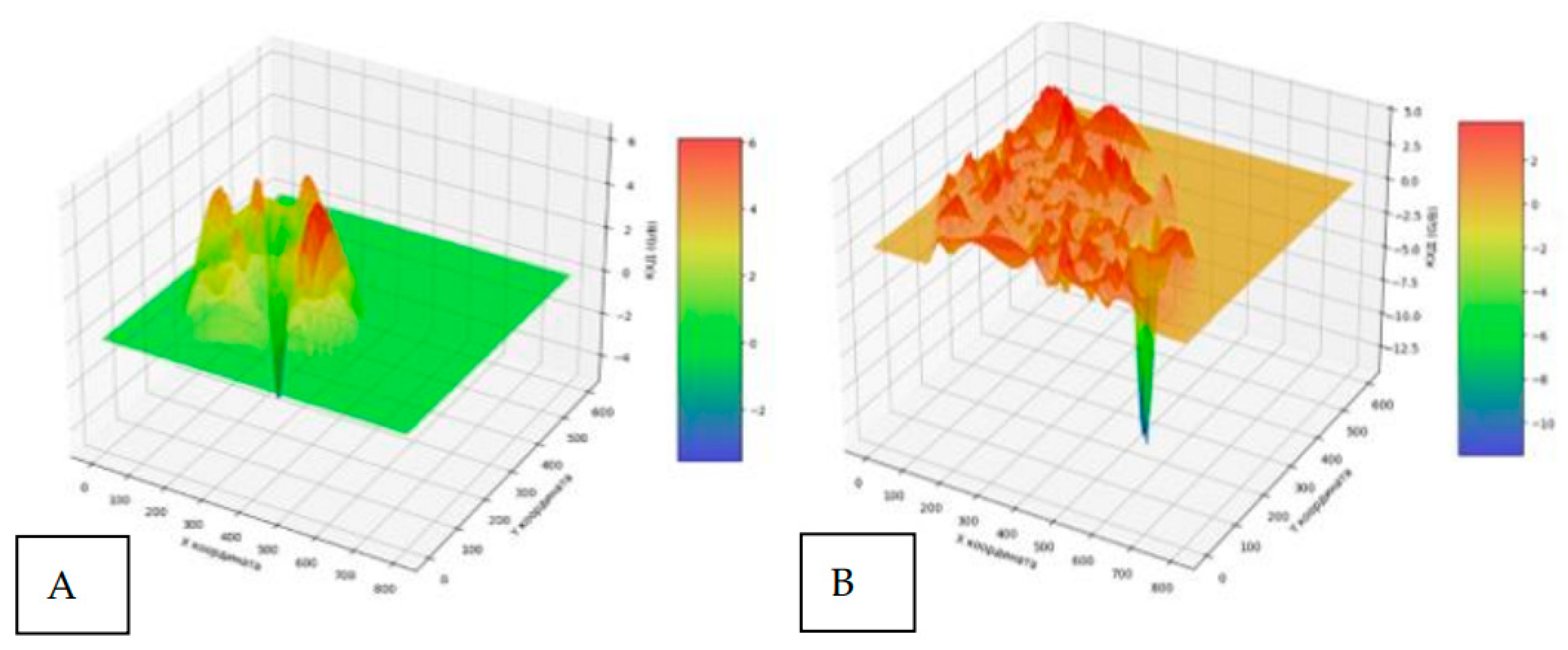

CYPOR Examination

- identification of specific factors (or their combination) responsible for induction;

- studying changes in the activity of CYPOR-dependent cytochrome P450 isoforms;

- assessment of the functional outcomes of such induction in vivo (e.g., clearance rate of specific substrates, formation of toxic metabolites, oxidative stress).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- While our study clearly established the presence of large-scale CYPOR induction, further research is required to fully understand the consequences:

- Identification of the specific pollutants (or combinations thereof) that contribute primarily to the observed induction.

- Concurrent measurement of the activity of key CYP isoforms (especially CYP1A and CYP3A) to assess the functional consequences of elevated CYPOR levels.

- Study of the temporal dynamics of CYPOR induction and its reversibility with decreasing pollution levels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CYPOR—cytochrome P450 reductase; |

| CYP—cytochrome P450; |

| NADPH—reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; |

| ROS—reactive oxygen species; |

| PAHs—polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; |

| PCBs—polychlorinated biphenyls; |

| ALT—Alanine Aminotransferase; |

| AST—aspartate aminotransferase; |

| PXR—pregnane X receptor; |

| CAR—constitutive androstane receptor; |

| AhR—aryl hydrocarbon receptor; |

| Mn—mineralization; |

| EC—electrical conductivity; |

| ORP—oxidation-reduction potential; |

| M—mean; |

| SD—standard deviation; |

| SE—standard error; |

| CV—coefficient of variation; |

| MAC—Maximum Allowable Concentration. |

References

- Popova, O.; Ponamarev, V. The prevalence of hepatopathy in productive animals and aquaculture objects. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Ensuring Sustainable Development: Ecology, Energy, Earth Science and Agriculture (AEES 2023), Moscow, Russia, 21–22 December 2023; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2024; p. 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, S.W.; Stentiford, G.D.; Kent, M.L.; Ribeiro Santos, A.; Lorance, P. Histopathological assessment of liver and gonad pathology in continental slope fish from the northeast Atlantic Ocean. Marine Environmental Research 2015; 106, 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Lopez, K.; Olivero-Verbel, J.; Caballero-Gallardo, K. Presence of Nematodes, Mercury Concentrations, and Liver Pathology in Carnivorous Freshwater Fish from La Mojana, Sucre, Colombia: Assessing Fish Health and Potential Human Health Risks. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2025, 88, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.A.; Aktar, M.N.A.S.; Halim, K.A.; Hasanuzzaman, K.M.; Islam, Md.A. Health and disease status of cultured Gulsha (Mystus cavasius) at Mymensingh region of Bangladesh. Research in Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries 2020, 7, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbabiaka, L.A.; Onwuzuruigbo, F.O.; Jimoh, O.A. Threat to fish food safety in Nigeria: Role of antimicrobial usage and resistance in aquaculture. Aquaculture Reports 2025, 40, 102643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zha, J.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J. Histopathological and proteomic responses in male Chinese rare minnow (Gobiocypris rarus) indicate hepatotoxicity following benzotriazole exposure. Environmental Pollution 2017, 229, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, G.L.; Jones, P.D.; Giesy, J.P. Pathologic alterations in adult rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, exposed to dietary 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Aquatic Toxicology 2000, 50, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponamarev, V. Methods for determining cytochrome P450 reductase in biological fluids of animals. BIO Web of Conferences 2025, 160, 01030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponamarev, V.S.; Popova, O.S.; Ukrainskaya, O.A. The role of the cytochrome system in the biotransformation of xenobiotics and drugs (review). Agrarian Science of the Euro-North-East 2025, 26, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyaeva, L.F.; Grishanova, A.Y.; Gromova, O.A.; Slynko, N.M.; Vavilin, V.A.; Lyakhovich, V.V. Microsomal monooxygenase system of living organisms in environmental biomonitoring. Analytical Review, Series “Ecology” 1994, 100. (Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences).

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, B.; Feng, S. Combined effects of two antibiotic contaminants on Microcystis aeruginosa. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2014, 279, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Xu, X.R.; Liu, S.S.; Zhou, G.J.; Sun, K.F.; Zhao, J.L.; Ying, G.G. Antibiotics in typical marine aquaculture farms surrounding Hailing Island, South China: occurrence, bioaccumulation and human dietary exposure. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2015, 90(1–2), 181–187. [CrossRef]

- Allameh, A.; Niayesh-Mehr, R.; Aliarab, A.; Sebastiani, G.; Pantopoulos, K. Oxidative Stress in Liver Pathophysiology and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larina, S.N.; Ignatiev, I.V.; Chebyshev, N.V.; Kukes, V.G. Nuclear receptors and xenobiotic metabolism. Antibiotics and Chemotherapy 2009, 54(3–4), 42–48. https://www.antibiotics-chemotherapy.ru/jour/article/view/221 (accessed 07 October 2025).

- Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Huerta, B.; Barceló, D. Bioaccumulation of emerging contaminants in aquatic biota: patterns of pharmaceuticals in Mediterranean river networks. In Emerging Contaminants in River Ecosystems: Occurrence and Effects under Multiple Stress Conditions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2016; pp. 121–141.

- Ambili, T.R.; Saravanan, M.; Ramesh, M.; Abhijith, D.B.; Poopal, R.K. Toxicological effects of the antibiotic oxytetracycline to an Indian major carp Labeo rohita. Archives of environmental contamination and toxicology 2013, 64, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.H.D. Combined Toxicity of Microplastics and Antimicrobials on Animals: A Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paramonov, S.G.; Zelikova, D.D.; Sklyarova, L.V.; Alkhutova, I.M. Environmental risks from micropollution of the environment with tetracycline. Pharmacy Formulas 2022, 4, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ai, W.; Ding, N.; Wang, H. Joint toxicity of fluoroquinolone and tetracycline antibiotics to zebrafish (Danio rerio) based on biochemical biomarkers and histopathological observation. The Journal of toxicological sciences 2017, 42, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au-Yeung, C.; Tsui, Y.-L.; Choi, M.-H.; Chan, K.-W.; Wong, S.-N.; Ling, Y.-K.; Lam, C.-M.; Lam, K.-L.; Mo, W.-Y. Antibiotic Abuse in Ornamental Fish: An Overlooked Reservoir for Antibiotic Resistance. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, N.L.; Lunegov, A.M.; Baryshev, V.A.; Popova, O.S.; Kuznetsova, E.V. Pharmacology in aquaculture: Study guide. St. Petersburg State Academy of Veterinary Medicine: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2017, 76 p.

- Petrova, E.A. Algorithm for taking blood from different animal species. Krasnoyarsk State Agrarian University: Krasnoyarsk, Russia, 2024, 115 p.

- Sula, E.; Aliko, V.; Pagano, M.; Faggio, C. Digital light microscopy as a tool in toxicological evaluation of fish erythrocyte morphological abnormalities. Microscopy research and technique 2020, 83, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canedo, A.; de Jesus, L.W.O.; Bailão, E.F.L.C.; Rocha, T.L. Micronucleus test and nuclear abnormality assay in zebrafish (Danio rerio): Past, present, and future trends. Environmental pollution (Barking, Essex : 1987) 2021, 290, 118019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorodumov, D.I.; Subbotin, V.V. Microbiological diagnostics of bacterial diseases of animals. Izograf: Moscow, Russia, 2005, 656 p.

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M. B.; Fernández, J. A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D. G.; Dunne, P. D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R. T.; Murray, L. J.; Coleman, H. G. , et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 16878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stritt, M.; Stalder, A.K.; Vezzali, E. Orbit Image Analysis: An open-source whole-slide image analysis tool. PLoS Computational Biology 2020, 16, e1007313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elabscience®. Cytochrome P450 Reductase (CPR) Activity Assay Kit Manual. No. E-BC-K808-M, p. 16. https://www.elabscience.com/p/cytochrome-p450-reductase-cpr-activity-assay-kit--e-bc-k808-m?srsltid=AfmBOopI_JLEBko6qm6MqBJlsC7K5d_tokVjeglzfoxDDnHfxX3TkR5k (accessed 7 October 2025).

- Kudersky, L.A. Selected works: Research in ichthyology, fisheries and related disciplines. Vol. 3. KMK: Moscow, Russia, 2013, 526 p.

- Zahran, E.; Mamdouh, A.Z.; Elbahnaswy, S.; El-Son, M.M.A.; Risha, E.; ElSayed, A.; El Barbary, M.I.; El Sebaei, M.G. The impact of heavy metal pollution: bioaccumulation, oxidative stress, and histopathological alterations in fish across diverse habitats. Aquacult Int 2025, 33, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, S.; Biswas, J.K. Histopathological fingerprints and biochemical changes as multi-stress biomarkers in fish confronting concurrent pollution and parasitization. iScience 2024, 27, 109457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.V.S. Biomarkers of trace element toxicity in fish: A new paradigm in environmental health risk assessment. In book: Fish Species in Environmental Risk Assessment Strategies. Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2024, 6-31. [CrossRef]

| Water Area | Shlisselburg Bay | Volkhov Bay | Svir Bay | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station | Sh1 | Sh2 | Sh3 | Sh4(C*) | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4(C*) | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4(C*) |

| Depth, m | 8 | 3,5 | 5 | 15 | 6 | 6,3 | 6,5 | 10 | 7,1 | 8,3 | 6,4 | 20 |

| Water area | Station | h, m | Horizon | Т,℃ | El, µS/cm | Mn, g/l | О2, mg/l | % sat, (О2) | pH | Eh, mV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volkhov Bay | V1 | 6 | surface | 19,1±0,7 | 162,2±0,5 | 0,103±0,060 | 9,5±0,5 | 103,2±1,3 | 8,2±0,4 | 133,0±1,3 |

| bottom | 19,8±0,6 | 187,3±0,6 | 0,122±0,020 | 8,8±0,3 | 95,5±1,5 | 7,8±0,3 | 80,0±1,2 | |||

| V2 | 6,3 | surface | 19,4±0,2 | 158,9±0,9 | 0,103±0,030 | 9,8±0,7 | 106,2±0,9 | 8,3±0,3 | 43,0±0,9 | |

| bottom | 18,6±0,3 | 171,1±0,7 | 0,115±0,050 | 9,5±0,5 | 101,3±1,5 | 8,1±0,4 | 62,0±0,7 | |||

| V3 | 6,5 | surface | 16,7±0,2 | 177,7±0,5 | 0,067±0,008 | 10,6±0,3 | 110,5±1,6 | 8,1±0,5 | 71,0±1,2 | |

| bottom | 15,8±0,6 | 103,3±0,2 | 0,066±0,003 | 10,2±0,1 | 106,7±1,2 | 8,2±0,5 | 83,0±1,2 | |||

| V4 | 10 | surface | 18,6±0,3 | 102,2±0,9 | 0,114±0,010 | 9,8±0,6 | 103,5±1,4 | 8,0±0,6 | 66,0±1,8 | |

| bottom | 17,4±0,3 | 101,2±0,7 | 0,095±0,001 | 11,0±0,4 | 96,5±1,3 | 7,8±0,2 | 84,0±0,9 | |||

| Svir Bay | S1 | 7,1 | surface | 12,8±0,5 | 94,5±0,8 | 0,061±0,002 | 11,2±0,3 | 105,7±1,7 | 8,0±0,1 | 99,0±0,6 |

| bottom | 12,0±0,85 | 95,9±0,6 | 0,060±0,005 | 11,00±0,1 | 106,6±1,0 | 8,0±0,3 | 112,0±1,0 | |||

| S2 | 8,3 | surface | 12,8±0,6 | 84,3±0,8 | 0,056±0,005 | 11,1±0,4 | 105,5±0,9 | 7,9±0,5 | 90,0±1,3 | |

| bottom | 12,6±0,4 | 83,9±0,7 | 0,055±0,006 | 11,3±0,2 | 105,5±1,5 | 7,9±0,2 | 125,0±1,8 | |||

| S3 | 6,4 | surface | 15,8±0,2 | 71,8±0,6 | 0,032±0,003 | 10,2±0,3 | 102,3±1,8 | 7,7±0,3 | 109,0±1,6 | |

| bottom | 15,5±0,3 | 71,2±0,5 | 0,030±0,006 | 10,3±0,5 | 100,8±1,4 | 7,4±0,2 | 130,0±0,9 | |||

| S4 | 22 | surface | 9,7±0,2 | 92,8±0,7 | 0,060±0,003 | 12,2±0,6 | 105,8±1,9 | 7,4±0,5 | 131,5±1,2 | |

| bottom | 9,5±0,4 | 95,2±0,2 | 0,060±0,002 | 12,3±0,5 | 102,6±1,8 | 7,1±0,4 | 110,0±1,0 | |||

| Shlisselburg Bay | Sh1 | 8 | surface | 16,0±0,4 | 92,5±0,5 | 0,061±0,001 | 10,5±0,1 | 105,8±1,2 | 7,6±0,4 | 84,2±0,3 |

| bottom | 14,5±0,2 | 94,7±0,5 | 0,061±0,001 | 10,4±0,2 | 98,7±1,4 | 7,8±0,4 | 156,2±1,9 | |||

| Sh2 | 3,5 | surface | 14,5±0,1 | 84,2±0,5 | 0,053±0,002 | 10,7±0,2 | 105,5±1,6 | 8,4±0,1 | 70,5±0,2 | |

| bottom | 13,0±0,2 | 87,3±0,4 | 0,053±0,004 | 11,2±0,3 | 105,5±1,2 | 8,0±0,5 | 92,5±0,3 | |||

| Sh3 | 5 | surface | 11,2±0,3 | 91,4±1,2 | 0,055±0,003 | 11,4±0,3 | 103,0±1,6 | 8,4±0,1 | 87,0±0,5 | |

| bottom | 10,2±0,7 | 90,7±0,5 | 0,063±0,005 | 11,5±0,4 | 98,9±1,0 | 7,9±0,1 | 98,3±1,0 | |||

| Sh4 | 15 | surface | 10,3±0,5 | 94,3±1,0 | 0,065±0,003 | 10,6±0,2 | 101,6±1,7 | 7,6±0,7 | 96,0±1,5 | |

| bottom | 10,0±0,4 | 93,5±0,7 | 0,066±0,001 | 10,5±0,9 | 97,7±1,2 | 7,4±0,6 | 95,0±1,7 |

| Seasons | Fishing stationsб | Fish species | Number of fish examined | Fish condition assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of fish with pathological changes (%) | Pathology severity (points) | Number of fish by points | ||||

| Spring | V1 5 km from the mouth of the Volkhov River |

bream pike-perch roach perch |

10 10 10 10 |

50 50 60 50 |

2-3-4,0 2-3,0 2-3-4,0 2-3,0 |

2-2,0;2-3,0;1-4,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 3-2,0;2-3,0;1-4,0 2-2,0;2-3,0; 1 -4,0 |

| V2 Syassky Pulp and Paper Mill area |

bream pike-perch roach perch |

10 10 10 10 |

60 70 60 50 |

2-3,0 2-3-4,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 |

2-2,0;4-3,0 2-2,0;4-3,0; 1-4,0 2-2,0; 4-3,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 |

|

| V3 5 km to the left of the mouth of the Volkhov River |

bream pike-perch roach perch |

10 10 10 10 |

50 40 50 40 |

2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 |

2-2,0;3-3,0 2-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 2-2,0;2-3,0 |

|

| V4 Outside the littoral zone |

bream pike-perch perch smelt |

10 10 10 10 |

40 40 50 30 |

2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 2,0 |

2-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0;2-3,0 1-2,0;4-3,0 3-2,0 |

|

| Summer | V1 5 km from the mouth of the Volkhov River |

bream pike-perch roach perch |

10 10 10 10 |

50 60 50 50 |

2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 |

2-2,0;3-3,0 4-2,0;2-3,0 3-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 |

| V2 Syassky Pulp and Paper Mill area |

bream pike-perch roach perch |

10 10 10 10 |

60 60 50 60 |

2-3-4,0 2-3-4,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 |

2-2,0;3-3,0;1-4,0 2-1,0;4-3,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 2-2,0;4-3,0 |

|

| V3 5 km to the left of the mouth of the Volkhov River |

bream pike-perch roach perch |

10 10 10 10 |

50 40 50 40 |

2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 |

2-2,0;3-3,0 1-2,0;3-3,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 2-2,0;2-3,0 |

|

| V4 Outside the littoral zone |

bream pike perch roach smelt |

10 10 10 10 |

40 30 50 30 |

2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 2,0 |

2-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0;1-3,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 3-2,0 |

|

| Autumn | V1 5 km from the mouth of the Volkhov River |

bream pike-perch roach perch |

10 10 10 10 |

40 50 40 50 |

2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 |

2-2,0;2-3,0 3-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 |

| V2 Syassky Pulp and Paper Mill area |

bream pike-perch roach perch |

10 10 10 10 |

50 60 50 50 |

2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 |

3-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0;4-3,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 2-2,0;3-3,0 |

|

| V3 5 km to the left of the mouth of the Volkhov River |

bream pike-perch roach perch |

10 10 10 10 |

40 40 30 40 |

2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 |

2-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0;1-3,0 2-2,0;2-3,0 |

|

| V4 Outside the littoral zone |

bream pike perch roach smelt |

10 10 10 10 |

40 30 40 20 |

2-3,0 2-3,0 2-3,0 2,0 |

3-2,0;1-3,0 2-2,0;1-3,0 2-2,0;2-3,0 2-2,0 |

|

| Pathological material tested | Bacteriological examination results | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample No. 1 | Isolated:

|

|

| Sample No. 2 | Isolated:

|

|

| Sample No. 3 | Isolated:

|

|

| Sample No. 4 | Isolated:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).