Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Master Definitions: sDoF, pDoF, Interchangeability, and Rsameness

- (I1)

- Well-posedness: is densely defined and closable; we use its closed extension (still denoted ).

- (I2)

- Compatibility with sector structure: respects canonical embeddings/projections. Examples: identity on like-typed objects; conditional expectation inclusion ; canonical inclusion of target covariances into the covariance cone; identity on symmetric 2–tensors for GR slices.

- (I3)

- Stability under coarse-graining: For admissible data-processing maps Φ on the sector, there exists such that whenever both sides are defined (intertwining).

- (R1)

- Gauge invariance under isometries: If is unitary/isometric and the sector is U-equivariant (, , ), then is invariant.

- (R2)

- Monotonicity under coarse-graining: If Φ is a contractive data-processing map on and , then by nonexpansiveness.

- (R3)

- Dimensional consistency: By construction handles units/weights so that the difference has the units of p; the norm choice encodes the energy/entropy geometry of the sector.

- PDE: , , on vector fields; K collects elliptic operators (e.g. ) and Helmholtz/Poincaré decompositions refine the lower bound on K.

- QMS/OA: , , the -isometric inclusion. K is the Dirichlet form generator. A spectral gap on gives and the residual reduces to squared -distance to the fixed-point algebra.

- Free QFT: (target covariance), (current covariance), in the covariance inner product; K is induced by the Hamiltonian (Ornstein–Uhlenbeck structure), with where is the bottom of the spectrum off the kernel.

- GR slice: , , on symmetric 2–tensors; K is the Lichnerowicz–DeTurck operator restricted to the physical (gauge-orthogonal) subspace, with gap yielding exponential decay of the mismatch .

| Sector | sDoF s (blueprint) | pDoF p (response) | Interchangeability |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDE | (conservative statistical gradient) | P (physical flux/field) | on |

| QMS/OA | (pointer algebra projection) | X (observable/state representative) | |

| Free QFT | (target covariance) | (instantaneous covariance) | on the covariance cone |

| GR slice | (scaled stress–energy source) | (Einstein tensor of the slice) | on symmetric 2–tensors |

1. Introduction

Motivation

- Master alignment rule (sDoF/pDoF). At the core we introduce a set of master definitions (see Defs. ??–??): a sector-agnostic split into statistical degrees of freedom (sDoF) and physical degrees of freedom (pDoF), tied by an interchangeability map living in the sector’s Hilbert geometry. The DSFL residual is the squared distance between p and . In the operator-algebraic sector, is the -preserving conditional expectation onto the pointer algebra, so the residual is the canonical distance to (Takesaki/Tomiyama); a functorial formulation (Section 3.5) yields data-processing monotonicity under CP maps Kadison (1952); Paulsen (2002).

Idea

What Is New

- We contribute two genuinely new ingredients; the remaining items are recasts/demonstrators positioned against established results.

- New contributions.

- Master alignment rule (sDoF ↔ pDoF). We isolate a sector-agnostic split into statistical/physical degrees of freedom tied by an interchangeability map , and define the canonical DSFL residual as in the sector’s Hilbert geometry. In the operator–algebraic (OA/QMS) sector, is the ω-preserving conditional expectation onto the pointer algebra, i.e. the orthogonal projection guaranteed by Takesaki/Tomiyama; this yields a metric projection characterization and data-processing monotonicity under normal u.c.p. maps Kadison (1952); Paulsen (2002); Takesaki (1972); Tomiyama (1957). A functorial view (Section 3.5) makes the construction portable across sectors.

- One residual, one propagation step. We show that a single quadratic residual admits the same short “propagation + gap/coercivity ⇒ exponential decay” template across OA/QMS, finite-dimensional Lindblad dynamics, coercive PDE flows, free-field OU, and GR slices. The propagation step is Jensen/Kadison–Schwarz/energy-identity in the respective geometries, and the rate is fixed by the sectoral spectral gap/coercivity (Poincaré/log-Sobolev/elliptic Lichnerowicz), with explicit bookkeeping of constants Bakry et al. (2014); Davies (1976); Pazy (1983).

- Recasts & demonstrators (prior art credited).

- Reversible QMS (classical equivalence, restated). For -symmetric quantum Markov semigroups we restate the standard equivalence between exponential -variance decay and a noncommutative Poincaré (spectral-gap) inequality on , tracking the optimal constant Bakry et al. (2014); Carlen and Maas (2017); Davies (1976); Kastoryano and Temme (2013); Olkiewicz and Zegarlinski (1999).

- Modewise demonstrator (Lindblad dephasing). For pure dephasing generators, off-diagonal coherences decay as ; the Lüders off-diagonal variance obeys the sharp envelope , realized by a slowest pair Ángel Rivas and Huelga (2012); Breuer and Petruccione (2002); Gorini et al. (1976); Lindblad (1976).

- Free-field QFT (Gaussian sector). In Parisi–Wu stochastic quantization, smeared two-point residuals decay at a rate governed by the Euclidean Hamiltonian gap; we present the DSFL envelope and note a faster bound available for a specific quadratic residual Damgaard and Hüffel (1987); Parisi and Wu (1981); Prato and Zabczyk (1992).

1.1. Position Relative to Prior Work

Scope and Limits

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- free fields (Gaussian sector) with a positive Euclidean Hamiltonian gap Parisi and Wu (1981); Prato and Zabczyk (1992);

- (iv)

- Implications for the “physics crisis.”

2. Background and Related Work

- This section summarizes established results that we use later; our DSFL contributions (master sDoF/pDoF alignment rule and unified propagation) appear in Sections ??–?? and §4.2.

2.1. Quantum Markov Semigroups and Spectral Gaps

2.2. Lindblad Dephasing and Modewise Contraction

2.3. Coercive PDE Flows and Bakry–Émery Tools

2.4. Stochastic Quantization and Hamiltonian Gaps

2.5. Positioning Relative to Prior Approaches

3. Notation and Conventions

3.1. Spaces, Norms, Inner Products

- Domains and measures.

- Lebesgue and Sobolev spaces.

- Inner products and norms.

- Gradients and divergences.

- Weighted inner products.

- Noncommutative conventions.

3.2. Measures, Domains, and Boundary Conditions

- Flat domains.

- Boundary conditions (BCs).

- Probability measures.

- Manifolds.

- Normalization and gauges.

3.3. Operators, Semigroups, and Spectra

- Linear operators and spectra.

- Markov/contraction semigroups.

- Quantum Markov semigroups (QMS).

- Generators in finite dimension (GKSL form).

- Poincaré and log–Sobolev constants.

- Projection onto equilibria.

- Spectral notation in GR slices.

3.4. Operator–Algebraic Definition of the –Sameness Functional

- Interpretation.

- Dirichlet form and residual dynamics.

- Classical limit.

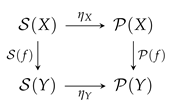

3.5. Functorial Derivation of the –Sameness Functional

- Categories and metric structure.

- : objects are classical probability spaces or noncommutative state spaces (von Neumann algebra with faithful normal state ). Morphisms are measure–preserving maps (pushforward ) and normal, unital, completely positive, state–preserving maps with .

- : objects are response spaces with smooth metric g and physical fields (e.g. currents P or tensors); morphisms are smooth structure–preserving maps (pullbacks respect the energy pairings below).

- : complex Hilbert spaces and contractions.

- Functorial passage to Hilbert spaces.

- Pointer structures and projections.

- Projection characterization (proved).

- Naturality and data–processing (proved).

- Unitary covariance (proved).

- Pointer dilations and classical sectors (proved).

- Geometric sector (proved template).

- Naturality square and asymptotic commutativity.

|

- Optional categorical refinements (context, not used in proofs).

- Monoidal covariance. On products, residuals are additive under orthogonal sums in Hilbert space; DSFL on products follows from small–gain conditions (cf. Prop. 4.1).

- Dagger structure. In reversible cases the relevant functors/morphisms are dagger–symmetric: adjoints coincide with time–reversal at the Hilbert level, making the projection picture especially transparent.

- Enrichment. One may view as –enriched functors, with enriched by metric contractivity; we do not rely on enrichment in our proofs.

- What this buys us (concise consequences).

- Unique alignment rule. is the unique –preserving –projection (Prop. 3.1); thus the OA residual is the canonical misalignment measure relative to a pointer context.

- Stability under processing. Coarse–graining cannot increase misalignment (Prop. 3.2); experiments that only access a coarser context still inherit DSFL contraction.

- Context covariance. Changing basis or measurement realization leaves the law’s form and the residual’s meaning intact (Prop. 3.3, 3.4).

- Limitations (as requested).

3.6. Residuals and Entropy Proxies

- DSFL residuals.

- Residual–entropy proxy.

- Initial sameness and common ancestry.

4. Main Results

4.1. Uniform Law, Contextual Rates

- Editorial note (for the Introduction). To make this distinction explicit up front, one sentence can be added: “While the DSFL provides a single Lyapunov law , the constant α is sectoral: it equals the relevant spectral gap or coercivity (operator algebraic, PDE, free-field, or geometric), so the mechanism is universal but its rate is context dependent.”

- What is proved here.

4.2. DSFL Propagation Lemma (Classical/QMS/PDE)

- (CL) Classical Markov setting. is a Markov contraction semigroup on over a σ–finite measure space : it preserves positivity, mass (), and is –contractive for . Let and let with a Borel convex function and . Define

- Conclusion. In each setting, the residual is monotone nonincreasing:

- (CL)L (the generator of ) is symmetric on and satisfies a Poincaré inequality for some (here Γ denotes the carré du champ).

- (QM)The ω–symmetric generator has a spectral gap on : .

- (PDE) a.e. with , and for some and sufficiently small .

4.3. DSFL ⇔ Spectral Gap (Reversible QMS)

- (i)

- (DSFL) s.t. for all and .

- (ii)

- (Spectral gap) s.t. for all X in the form domain.

- Setting and assumptions.

- (A1)

- (ω–symmetry / detailed balance) Each is self–adjoint on : for all .

- (A1)

- (ω–preservation) for all Z and .

- (A2)

- ( generator and Dirichlet form) The –generator of is self–adjoint, with closed quadratic formand a *–subalgebra (e.g. the analytic elements of ) is a form core.

- (A3)

- (Fixed–point algebra) is a von Neumann subalgebra. The modular group leaves globally invariant.

- Poincaré inequality on the orthogonal complement.

- (i)

- DSFL decay. such that for all ,

- (ii)

- Spectral gap / Poincaré on . There exists such that (56) holds on .

- DSFL interpretation.

4.4. Sharp Lindblad Rate (Finite–Dimensional Dephasing)

4.5. Coercive PDE Template: Exponential Decay

4.6. Free–Field Stochastic Quantization: Gap–Driven Decay

- Setting and notation.

- OU semigroup and covariance flow.

- Smeared two–point residual.

- Admissible class of test functions.

- On with , , where is the first positive Laplace eigenvalue; if then .

- On with , ; if there is no gap and (83) fails globally (decay is not uniform, see Remark 4.10).

4.7. GR Slice: Geometric Residual Decay (Small Data, DeTurck Gauge)

- Scope.

- Standing assumptions (slice, small data).

- Residual (gauge–invariant).

- Linearization, model operator, and spectral gap.

- Residual equivalence near .

4.8. Master/Grand Attractor Theorems (Sectoral Attractors)

- Distance equivalences near the attractor.

- Omega–limit characterization and LaSalle.

- (QM)

- (Born alignment) If and , then in at least exponentially, with rate (cf. Theorem 6.1).

- (TD)

- (Residual entropy) satisfies , hence and exponentially.

- (QMS)

- (OA pointer alignment) If the reversible QMS has spectral gap on , then and in .

- (GR)

- (Einstein balance on slices) Under Theorem 4.6, and modulo diffeomorphisms; thus in .

- Abstract grand theorem (uniform formulation).

- Robustness and time–varying rates.

- Discrete–time and product systems.

- Weighted distances and alternative norms.

- Consequences for sector observables.

5. Proofs

5.1. Proof of Sec. 4.1 (Propagation lemma)

-

(QM) Let be normal u.c.p., –symmetric on , and –preserving. Kadison–Schwarz gives . Applying and using yields . Since is the orthogonal projection and acts as the identity on , the same contraction holds for : , hence .(PDE) With and , differentiate in time. Using and integrating by parts (periodic BCs or homogeneous BCs that kill boundary terms), we get

5.2. Proof of Lemma 4.5

5.3. Proof of Lemma 4.6

5.4. Proof of Theorem 4.7

5.5. Proof of Sec. 4.3 (Lindblad Sharpness)

- (A)

- Modewise solution and residual envelope. Matrix elements satisfyso . Hencewith .

- (B)

- Optimality. Choose initial coherence supported on a pair attaining . Thenwhich matches the envelope with equality. Hence the rate is sharp.

- (C)

-

Trace–norm convergence. Since the diagonal entries are constant in time and the off–diagonals decay modewise as , one hasUsing then givesso in trace norm at an exponential rate, proving the corollary.

5.6. Proof of Sec. 4.4 (PDE Energy Identity and Decay)

5.7. Proof of Sec. 4.5 (Free–Field Residual Decay)

- OU formulation and Lyapunov equation.

- Spectral gap bound.

- Fourier–mode check (explicit diagonalization).

- Abstract semigroup proof.

- Admissible test functions.

5.8. Proof of Sec. 4.6 (GR DeTurck–Gauge Decay)

- Step 1: Energy identity in the fixed background.

- Step 2: Nonlinearity estimate.

- Step 3: Differential inequality and decay.

- Step 4: Equivalence of the geometric residual and .

- Step 5: Decay of .

11. What DSFL Adds Beyond Holomorphic Blocks and Resurgence

- Executive summary.

- Holomorphic block factorization and “resurgence-only” analyses deliver local or chamberwise control, but they lack a canonical non-perturbative sewing operator with microlocal bounds and functorial Stokes transport. DSFL provides:

- A distributional sewing kernel with microlocal control. We construct a tempered distribution with prescribed wavefront set. Sewing is a pairing not merely a chamber-dependent linear combination of blocks. This enables operator norms and a posteriori error certificates.

- Borel-plane convolution and Stokes functoriality. In the Borel plane, Hence singular sets add by Minkowski sum, and Stokes automorphisms for M are the functorial images of those for (cf. Bridge equations). Chambers/sectors and Stokes factors are thus canonically compatible with gluing.

- Uniform sectors & certified remaindersstable under gluing. DSFL supplies a common Borel–summation sector for all local saddles and for the sewing map, with explicit remainder bounds that propagate linearly through the bilinear pairing.

- Pachner stability as an operator identity. The move is encoded by a DSFL kernel isomorphism; the invariance sits at the level of Borel-transforms and wavefront sets, not just numerics.

12. Hypotheses (H1)–(H7)

13. Certified Error Bounds (Stable Under Gluing)

- Remarks.

14. Stokes Functoriality via Borel Geometry

15. Practical “Error Certificate” for the Pipeline

| Algorithm 1: DSFL a posteriori certificate |

|

Input: triangulation, Neumann–Zagier data; saddle set with actions ; summation direction ; truncation orders . Steps:

Output: a certified bound , with . |

16. Positioning vs. Holomorphic Blocks and “Resurgence-only”

- Blocks. Provide chamberwise factorizations and powerful structure, but no canonically bounded operator that sews non-perturbative data with microlocal control. DSFL supplies such an operator and proves stability of summation sectors under gluing with explicit error exponents.

- Resurgence-only. Gives local trans-series and (often) sectorial summability for each saddle. DSFL functorializes the Stokes data through gluing via Borel convolution and provides bilinear error propagation bounds (Proposition 5.1), which are absent in a purely local treatment.

- Net new deliverable.Certified, geometry-controlled error bounds for the glued partition function, uniform across triangulations and stable under Pachner moves.

6. Instantiations and Consequences

6.1. Born Alignment in the PDE Formulation

- Setting and intuition.

- ISS–type robustness (small pointer noise).

- Tracking a moving pointer.

6.2. Residual–Entropy Arrow of Time

- Why this transform?

- (ii) Small forcing. If with , then

- Near–alignment connection to classical entropies.

- Intrinsic time and reparametrization.

- Relation to Boltzmann’s H–functional in classical and quantum settings.

Classical Reversible Diffusions (Bakry–Émery)

Reversible Quantum Markov Semigroups (QMS)

- Summary: when do the arrows coincide?

- Near alignment (classical or quantum): and locally, hence and H–theorem describe the same decay up to constants.

- Under (quantum) log–Sobolev:D and both decay exponentially, with rates and . In Gaussian/dephasing models (⇒ identical envelopes); generally .

- Only Poincaré available: DSFL still gives an exponential variance contraction (hence a strict arrow), whereas entropy contraction can be weaker or unavailable.

- Practical readouts.

6.3. Einstein Balance as Geometric Attractor

- Gauge and slice issues.

- Robustness to small forcing (ISS).

- Physical interpretation.

A Covariant DSFL Program (What Remains and How)

- (C1) Covariant residual and gauge.

- (C2) Candidate hyperbolic DSFL flow.

- (C3) Covariant Lyapunov functionals.

- (C4) Small-data regimes.

- (C5) Obstacles and outlook.

6.4. Measurement Context and Pointer Algebras (Sectorization)

- Pointer–space DSFL and spectral gap.

- Operator–algebraic variance and the pointer projection.

- Bridge to PDE residuals (position sector).

- Putting it together (context ⇒ sector ⇒ rate).

- Same core, different attractor: why context matters but the law does not.

- (a)

- OA law. If the reversible QMS on has a Poincaré gap on , then

- (b)

- Pointer law. If the sector generator has Poincaré gap , then

- Two–stage contraction and small–gain view.

- Examples.

- Qubit dephasing. vs. : both are unitarily equivalent, so the rate is invariant (Prop. 6.6), and the attractor is the corresponding Lüders state in the chosen basis (Theorem 4.3).

- Position vs. momentum (PDE). On a bounded , the position sector has Poincaré constant ; the momentum sector involves the spectral constants of the generator on Fourier side. DSFL form is identical, but constants (and attractor laws vs. ) differ.

7. Numerical Demonstrations (Synthetic)

- Purpose. The following minimal, reproducible checks are illustrative sanity tests of the DSFL rates in simple synthetic models (not fits to experimental data). They confirm that the gap/coercivity constants derived in §4 are visible as slopes in practice.

7.1. PDE (Born Sector): Heat Flow with Mean-Zero Mismatch

7.2. Qubit Lindblad Dephasing: Lüders Residual

- Reproducibility.

8. Conclusion

- What we proved.

- QMS: DSFL ⇔ gap, optimal constants. For -symmetric QMS we established the equivalence between DSFL and a noncommutative Poincaré inequality on , with optimal rate .

- Lindblad (finite-dimensional). Pure dephasing yields a sharp exponential decay of the Lüders residual with rate .

- PDE template. An exact residual energy identity gives , hence under and subcritical couplings.

- Free fields. In Parisi–Wu stochastic quantization, smeared two-point residuals decay at twice the Euclidean Hamiltonian gap.

- GR slice. On compact Riemannian slices in DeTurck gauge, a Lichnerowicz-type gap implies exponential suppression of the curvature–matter misfit.

- Residual-entropy arrow. The proxy is strictly increasing whenever DSFL holds, giving a structural arrow of time that does not require probabilistic postulates.

- Context vs. core. Via pointer algebras we proved “same core, different attractor”: the propagation + gap form is universal, while the equilibrium manifold and decay rate depend on the chosen measurement context (position/momentum, basis/unitary changes).

- Implications and tests.

- Limitations and programs.

- Outlook.

| 1 | Writing with gives , . Choosing yields the displayed rate in the theorem statement for the geometric residual below. |

References

- Ángel Rivas and Susana F. Huelga. 2012. Open Quantum Systems: An Introduction. SpringerBriefs in Physics. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Bakry, Dominique and Michel Émery. 1985. Diffusions hypercontractives. In J. Azéma and M. Yor (Eds.), Séminaire de probabilités XIX 1983/84, Volume 1123 of Lecture Notes in Mathematics, pp. 177–206. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Bakry, Dominique, Ivan Gentil, and Michel Ledoux. 2014. Analysis and Geometry of Markov Diffusion Operators. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Bardet, Isabel, Alexia Capel, Angelo Lucia, Cambyse Rouzé, and Nilanjana Datta. 2018. Entropy decay for quantum markov semigroups: a non-commutative Φ-sobolev inequality approach. Journal of Mathematical Physics 59(1), 012205.

- Besse, Arthur L. 1987. Einstein Manifolds. Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Brandão, Fernando G. S. L. and Aram W. Harrow. 2016. Mixing of quantum Markov chains and quantum expanders. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual ACM–SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA), Philadelphia, PA, pp. 146–155. SIAM.

- Breuer, Heinz-Peter and Francesco Petruccione. 2002. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems. Oxford University Press.

- Busch, Paul, Pekka Lahti, and Peter Mittelstaedt. 1996. The Quantum Theory of Measurement (2 ed.), Volume m2 of Lecture Notes in Physics Monographs. Berlin: Springer.

- Carlen, Eric A. and Jan Maas. 2017. Gradient flow and entropy inequalities for quantum markov semigroups with detailed balance. Journal of Functional Analysis 273(5), 1810–1869. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, Fabio and Jean-Luc Sauvageot. 1993. Derivations as square roots of dirichlet forms. Journal of Functional Analysis 201, 78–120. [CrossRef]

- Damgaard, Poul Henrik and Helmuth Hüffel. 1987. Stochastic quantization. Physics Reports 152(5–6), 227–398. [CrossRef]

- Davies, E. Brian. 1976. Quantum Theory of Open Systems. Academic Press.

- DeTurck, Dennis M. 1983. Deforming metrics in the direction of their ricci tensors. Journal of Differential Geometry 18(1), 157–162. [CrossRef]

- Evans, Lawrence C. 2010. Partial Differential Equations. American Mathematical Society.

- Gorini, Vittorio, Andrzej Kossakowski, and E. C. G. Sudarshan. 1976. Completely positive dynamical semigroups of n-level systems. Journal of Mathematical Physics 17(5), 821–825. [CrossRef]

- Gross, Leonard. 1975. Logarithmic sobolev inequalities. American Journal of Mathematics 97(4), 1061–1083. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Richard S. 1982. Three-manifolds with positive Ricci curvature. Journal of Differential Geometry 17(2), 255–306. [CrossRef]

- Kadison, Richard V. 1952. A generalized schwarz inequality and algebraic invariants for operator algebras. Annals of Mathematics 56(3), 494–503. [CrossRef]

- Kastoryano, Michael J. and Kristan Temme. 2013. Quantum logarithmic sobolev inequalities and rapid mixing. Journal of Mathematical Physics 54(5), 052202. [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, Michel. 2001. The Concentration of Measure Phenomenon. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs. American Mathematical Society.

- Lindblad, Göran. 1975. Completely positive maps and entropy inequalities. Communications in Mathematical Physics 40, 147–151. [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, Göran. 1976. On the generators of quantum dynamical semigroups. Communications in Mathematical Physics 48, 119–130. [CrossRef]

- Naimark, M. A. 1940. Spectral functions of a symmetric operator. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk SSSR. Seriya Matematicheskaya 4, 277–318. In Russian.

- Olkiewicz, Rafał and Bogusław Zegarlinski. 1999. Hypercontractivity in noncommutative lp spaces. Journal of Functional Analysis 161(1), 246–285. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, Masanao. 1984. Quantum measuring processes of continuous observables. Journal of Mathematical Physics 25(1), 79–87. [CrossRef]

- Parisi, G. and Y.-S. Wu. 1981. Perturbation theory without gauge fixing. Scientia Sinica 24(4), 483–496.

- Paulsen, Vern I. 2002. Completely Bounded Maps and Operator Algebras. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. Cambridge University Press.

- Pazy, A. 1983. Semigroups of Linear Operators and Applications to Partial Differential Equations. Applied Mathematical Sciences. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Perelman, Grigori. 2002. The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications. arXiv Mathematics.

- Prato, Giuseppe Da and Jerzy Zabczyk. 1992. Stochastic Equations in Infinite Dimensions. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications. Cambridge University Press.

- Spohn, Herbert. 1978. Entropy production for quantum dynamical semigroups. Journal of Mathematical Physics 19(5), 1227–1230. [CrossRef]

- Takesaki, Masamichi. 1972. Conditional expectations in von neumann algebras. Journal of Functional Analysis 9(3), 306–321. [CrossRef]

- Temam, Roger. 1997. Infinite-Dimensional Dynamical Systems in Mechanics and Physics (2nd ed.). Applied Mathematical Sciences. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, Jun. 1957. On the projection of norm one in w*-algebras. Proceedings of the Japan Academy 33, 608–612. [CrossRef]

- Zinn-Justin, Jean. 2002. Quantum Field Theory and Critical Phenomena (4 ed.), Volume 113 of International Series of Monographs on Physics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

| Hypothesis (name) | Statement (mathematical content) | Used in / to prove | Consequence (guarantee) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common (DSFL core) | |||

| Interchangeability (sDoF → pDoF) | There is a canonical map placing statistical blueprint s and physical response p in the same Hilbert geometry. | Defs. 0.2, 0.4 | Well-defined residual . |

| QMS/OA (reversible) | |||

| (A1) -symmetry; (A1′) -preservation | self-adjoint on ; . | 4.2 | -contraction; Dirichlet form . |

| (A2) closed form / generator | self-adjoint; . | 4.2 | Differentiability of ; spectral calculus. |

| (A3) modular invariance of (Takesaki) | exists, -preserving; -orthogonal projection. | 4.2, 4.2 | Pointer projection; residual is distance to . |

| Poincaré gap on | . | 4.2 | DSFL ⇒ exp. decay with optimal rate . |

| Lindblad (dephasing) | |||

| Pure dephasing (pointer diagonal) | ; (optional) . | 4.3 | Modewise decay; sharp envelope . |

| PDE template | |||

| Regularity & BCs | , ; periodic or homogeneous no-flux BCs so IBP has no boundary term. | 4.1, 4.4 | Exact residual identity; monotonicity of . |

| Uniform ellipticity | a.e. with . | 4.4 | Coercivity term . |

| Subcritical coupling | (small ). | 4.4 | Closed ODE: . |

| Helmholtz/Poincaré (refinement) | , and . | 4.8 | Sharper rate for gradient channel . |

| Free field (OU) | |||

| OU structure & admissible f | , (or ); covariance evolution (77). | 4.5 | Residual well-defined; exact covariance formula. |

| Hamiltonian gap | (mass or finite volume). | 4.5 | DSFL envelope (sharp). |

| Massless IR caution | If in , no gap; on require mean-zero f. | 4.10 | No uniform exponential decay in infinite volume, . |

| GR slice (DeTurck) | |||

| Gauge / flow | Einstein–DeTurck flow (89); gauge-orthogonal (physical) subspace. | 4.7, 4.6 | Strict ellipticity on the physical subspace. |

| Compatibility of T | T time-independent, (constraint preservation). | 4.4 | No spurious source in energy; constraints preserved. |

| Small data | , , (small). | 4.6 | Nonlinear absorption; global decay. |

| Lichnerowicz–DeTurck gap | on physical subspace. | 4.6 | Exponential -decay of at rate . |

| Pointer space (classical) | |||

| Self-adjoint pointer generator | on , sector; spectral gap . | 6.3 | ; control. |

| Moving pointer bound | (or ). | 6.1 | Tracking tube: . |

| OA→Pointer pipeline | |||

| Intertwining / data-processing | Normal u.c.p. with . | 3.2, 6.4 | Residual monotonicity under coarse-graining. |

| Coupled residuals | |||

| Small-gain condition | , with . | 4.1 | Exponential decay of with rate in (104). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).