Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

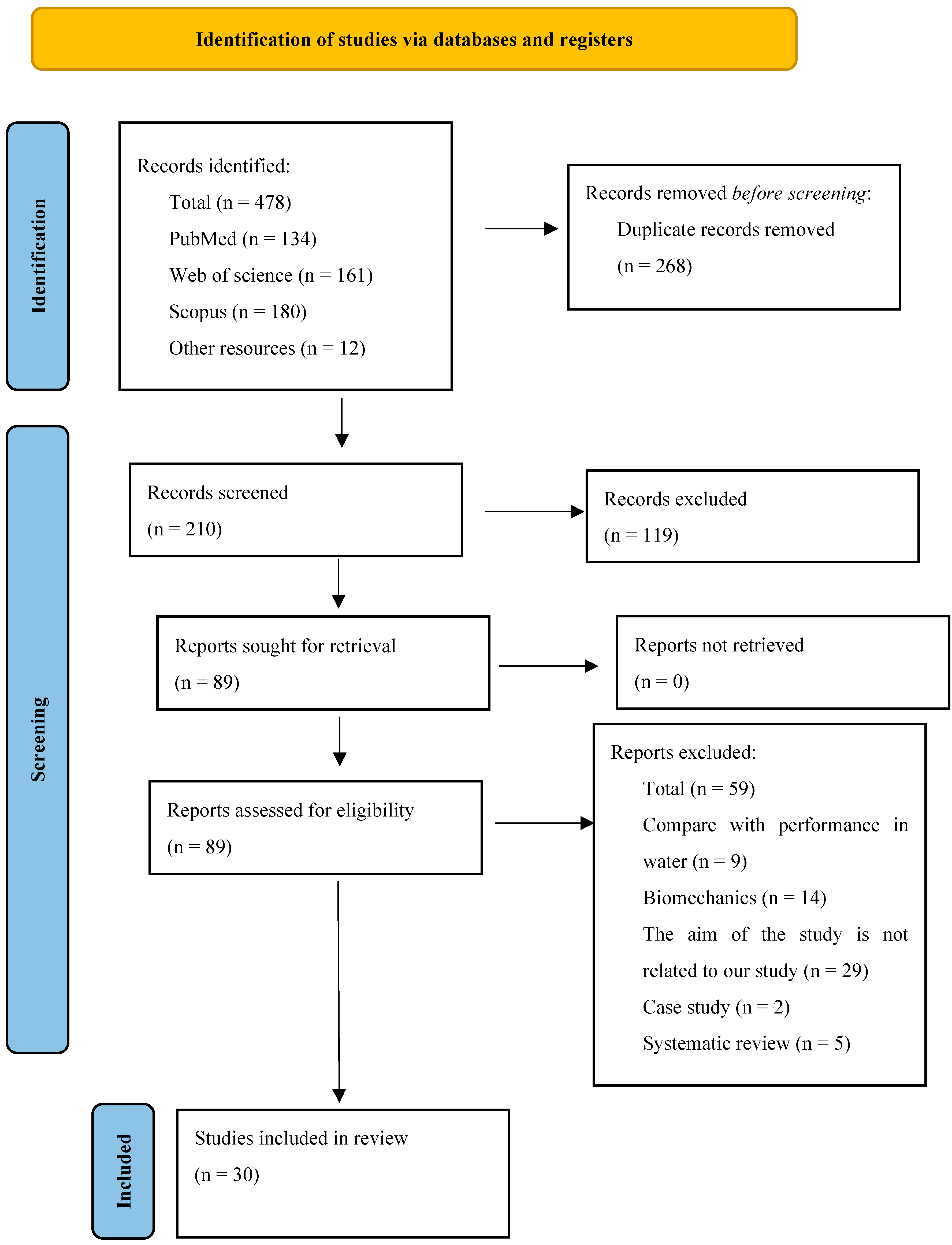

2.1. Systematic Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction Strategy

2.4. Study Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Review Statistics

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Main Tests for Performance Measurement

3.4. Main Findings

3.5. Study Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Characteristics

4.2. Main Tests for Performance Measurement

| Physiological Variable | Definition / Description | 2,000-m Performance | Advantages | Limitations |

| VO2max | Maximal oxygen uptake (L/min), measured during INCR using gas analysis. Reflects aerobic capacity. | Very high to almost perfect (r = 0.76–0.99) depending on athlete category. | Gold standard for aerobic fitness; high predictive power; validated across multiple populations. | Requires expensive equipment and lab setting; time-consuming; effort-dependent; less accessible for low-budget teams. |

| Estimated from 3-min all-out test– non-invasive protocol to derive VO₂max without gas exchange analysis. | Strong agreement with traditional gas-based VO₂max values. | Time-efficient; low-cost alternative; suitable for field testing; allows performance estimation without sophisticated tools. | Less widely validated; may not replace direct gas analysis in elite settings. | |

| Peak Power Output (INCR) | Highest power (W) achieved during an INCR to exhaustion (continuous or discontinuous). | High to almost perfect (r = 0.84–0.99) |

Easy to measure with rowing ergometer; non-invasive; suitable for field or lab; correlates with VO₂max and 2,000-m performance |

Requires maximal effort and proper protocol standardization; results may vary with pacing strategy or motivation. |

| Blood Lactate Concentration | Blood lactate measured during rest intervals in INCR; commonly analyzed at anaerobic threshold (4 mmol/L). Reflects metabolic response and aerobic/anaerobic transition zones. | High to very high at threshold (r = 0.83–0.92); poor post-threshold (r = 0.19). | Enables individualized training zones; widely used in endurance sports; strong predictor at 4 mmol/L threshold; relevant for both HWT and LWT categories | Invasive (requires blood sampling); limited utility after threshold due to weak correlation with performance; needs biochemical analysis and trained personnel. |

4.3. Main Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| INCR | Incremental tests |

| FISA | Fédération Internationale des Sociétés d’Aviron |

| CP | Critical Power |

| CV | Critical Velocity |

| VO2max | Maximal oxygen uptake |

| W | Watts |

| PO | Power Output |

References

- Ingham, S.A.; Whyte, G.P.; Jones, K.; Nevill, A.M. Determinants of 2,000 m Rowing Ergometer Performance in Elite Rowers. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 88, 243–246. [CrossRef]

- Šarabon, N.; Kozinc, Ž.; Babič, J.; Marković, G. Effect of Rowing Ergometer Compliance on Biomechanical and Physiological Indicators during Simulated 2,000-Metre Race. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2019, 18, 264–270.

- Smith, T.B.; Hopkins, W.G. Measures of Rowing Performance. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 343–358. [CrossRef]

- Vogler, A.J.; Rice, A.J.; Withers, R.T. Physiological Responses to Exercise on Different Models of the Concept II Rowing Ergometer. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2007, 2, 360–370.

- Boyas, S.; Nordez, A.; Cornu, C.; Guével, A. Power Responses of a Rowing Ergometer: Mechanical Sensors vs. Concept2® Measurement System. Int. J. Sports Med. 2006, 27, 830–833. [CrossRef]

- Mäestu, J.; Jürimäe, J.; Jürimäe, T. Monitoring of Performance and Training in Rowing. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 597–617. [CrossRef]

- Possamai, L.T.; Borszcz, F.K.; de Aguiar, R.A.; de Lucas, R.D.; Turnes, T. Agreement of Maximal Lactate Steady State with Critical Power and Physiological Thresholds in Rowing. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2022, 22, 371–380. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.F.; de Almeida-Neto, P.F.; de Matos, D.G.; Riechman, S.E.; de Queiros, V.; de Jesus, J.B.; Reis, V.M.; Clemente, F.M.; Miarka, B.; Aidar, F.J.; et al. Performance Prediction Equation for 2000 m Youth Indoor Rowing Using a 100 m Maximal Test. Biology 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Mikulic, P. Anthropometric and Metabolic Determinants of 6,000-m Rowing Ergometer Performance in Internationally Competitive Rowers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 1851–1857. [CrossRef]

- Akça, F. Prediction of Rowing Ergometer Performance from Functional Anaerobic Power, Strength and Anthropometric Components. J. Hum. Kinet. 2014, 41, 133–142. [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, H.; Rahmani, A.; Chorin, F.; Lardy, J.; Giroux, C.; Ratel, S. The 1,500-m Rowing Performance Is Highly Dependent on Modified Wingate Anaerobic Test Performance in National-Level Adolescent Rowers. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2016, 28, 572–579. [CrossRef]

- Riechman, S.E.; Zoeller, R.F.; Balasekaran, G.; Goss, F.L.; Robertson, R.J. Prediction of 2000 m Indoor Rowing Performance Using a 30 s Sprint and Maximal Oxygen Uptake. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 681–687. [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, A.; Cerasola, D.; Russo, G.; Zangla, D.; Traina, M. Mean Power during 20 Sec All out Test to Predict 2000 m Rowing Ergometer Performance in National Level Young Rowers. J. Sports Med. Physiol. Fit. 2015, 55, 872–877.

- Cerasola, D.; Zangla, D.; Grima, J.N.; Bellafiore, M.; Cataldo, A.; Traina, M.; Capranica, L.; Maksimovic, N.; Drid, P.; Bianco, A. Can the 20 and 60 s All-Out Test Predict the 2000 m Indoor Rowing Performance in Athletes? Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Cerasola, D.; Bellafiore, M.; Cataldo, A.; Zangla, D.; Bianco, A.; Proia, P.; Traina, M.; Palma, A.; Capranica, L. Predicting the 2000-m Rowing Ergometer Performance from Anthropometric, Maximal Oxygen Uptake and 60-s Mean Power Variables in National Level Young Rowers. J. Hum. Kinet. 2020, 75, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.J.; Hornikel, B.; Sullivan, K.; Fedewa, M. Associations between Multimodal Fitness Assessments and Rowing Ergometer Performance in Collegiate Female Athletes. Sports 2020, 8, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Gabarren, M.; De Txabarri Expósito, R.G.; De Villarreal, E.S.S.; Izquierdo, M. Physiological Factors to Predict on Traditional Rowing Performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 108, 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, M.; Lacour, J.-R.; Imbert, C.; Messonnier, L.A. Factors of Rowing Ergometer Performance in High-Level Female Rowers. Int. J. Sports Med. 2017, 38, 1023–1028. [CrossRef]

- Ingham, S.A.; Pringle, J.S.; Hardman, S.L.; Fudge, B.W.; Richmond, V.L. Comparison of Step-Wise and Ramp-Wise Incremental Rowing Exercise Tests and 2000-m Rowing Ergometer Performance. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2013, 8, 123–129. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.F.; Yang, Y.S.; Lin, H.M.; Lee, C.L.; Wang, C.Y. Determination of Critical Power in Trained Rowers Using a Three-Minute All-out Rowing Test. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 1251–1260. [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Estarli, M.; Barrera, E.S.A.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2016, 4, 148–160. [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 805–835. [CrossRef]

- Lawton, T.W.; Cronin, J.B.; McGuigan, M.R. Strength Testing and Training of Rowers: A Review. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 413–432. [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, P.C.; David, A.Z.; Buckley, J.D. A Single Exercise Test for Assessing Physiological and Performance Parameters in Elite Rowers: The 2-in-1 Test. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 205–211. [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, M.; Messonnier, L.; Hager, J.P.; Lacour, J.R. Peak Power Output Predicts Rowing Ergometer Performance in Elite Male Rowers. Int. J. Sports Med. 2004, 25, 368–373. [CrossRef]

- Mikulic, P.; Vucetic, V.; Sentija, D. Strong Relationship between Heart Rate Deflection Point and Ventilatory Threshold in Trained Rowers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 360–366.

- Cosgrove, M.J.; Wilson, J.; Watt, D.; Grant, S.F. The Relationship between Selected Physiological Variables of Rowers and Rowing Performance as Determined by a 2000 m Ergometer Test. J. Sports Sci. 1999, 17, 845–852. [CrossRef]

- Gillies, E.M.; Bell, G.J. The Relationship of Physical and Physiological Parameters to 2000 m Simulated Rowing Performance. Sports Med. Train. Rehabil. 2000, 9, 277–288. [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, M.; Fukunaga, T.; Higuchi, M.; Kawakami, Y. Stroke Power Consistency and 2000 m Rowing Performance in Varsity Rowers. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2009, 19, 83–86. [CrossRef]

- Kendall, K.L.; Smith, A.E.; Fukuda, D.H.; Dwyer, T.R.; Stout, J.R. Critical Velocity: A Predictor of 2000-m Rowing Ergometer Performance in NCAA D1 Female Collegiate Rowers. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 945–950. [CrossRef]

- Otter, R.T.A.; Brink, M.S.; Lamberts, R.P.; Lemmink, K.A.P.M. A New Submaximal Rowing Test to Predict 2,000-m Rowing Ergometer Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2426–2433. [CrossRef]

- Turnes, T.; Possamai, L.T.; Penteado Dos Santos, R.; De Aguiar, R.A.; Ribeiro, G.; Caputo, F. Mechanical Power during an Incremental Test Can Be Estimated from 2000-m Rowing Ergometer Performance. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2020, 60, 214–219. [CrossRef]

- Huerta Ojeda, Á.; Riquelme Guerra, M.; Coronado Román, W.; Yeomans, M.-M.; Fuentes-Kloss, R. Kinetics of Ventilatory and Mechanical Parameters of Novice Male Rowers on the Rowing Ergometer. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2022, 22, 422–436. [CrossRef]

- Huerta Ojeda, Á.; Guerra, M.R.; Román, W.C.; Yeomans-Cabrera, M.M.; Fuentes-Kloss, R. Six-Minute Rowing Test: A Valid and Reliable Method for Assessing Power Output in Amateur Male Rowers. PeerJ 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- McGrath, E.; Mahony, N.; Fleming, N.; Donne, B. Prediction of Rowing Functional Threshold Power Using Body Mass, Blood Lactate and GxT Peak Power Data. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2023, 16, 31–41.

- Messonnier, L.; Aranda-Belthouze, S.E.; Bourdin, M.; Bredel, Y.; Lacour, J.-R. Rowing Performance and Estimated Training Load. Int. J. Sports Med. 2004, 26, 376–382. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.; Frydkjær, M.; Jensen, N.M.B.; Bannerholt, L.M.; Gam, S. A Maximal Rowing Ergometer Protocol to Predict Maximal Oxygen Uptake. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2021, 16, 382–386. [CrossRef]

- Mazza, O.B.; Gam, S.; I Kolind, M.E.; Kiaer, C.; Jensen, K. A Maximal Rowing Ergometer Protocol to Predict Maximal Oxygen Uptake in Female Rowers. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2021, 16, 382–386. [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, P.C.; Woolford, S.M.; Buckley, J.D. Effects of Varying the Step Duration on the Determination of Lactate Thresholds in Elite Rowers. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 687–693. [CrossRef]

- Nevill, A.M.; Allen, S.V.; Ingham, S.A. Modelling the Determinants of 2000 m Rowing Ergometer Performance: A Proportional, Curvilinear Allometric Approach. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Joyner, M.J.; Coyle, E.F. Endurance Exercise Performance: The Physiology of Champions. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Steinacker, J.M. Physiological Aspects of Training in Rowing. Int. J. Sports Med. 1993, 14.

- Astridge, D.J.; Peeling, P.; Goods, P.S.R.; Girard, O.; Hewlett, J.; Rice, A.J.; Binnie, M.J. Rowing in Los Angeles. Performance Considerations for the Change to 1500 m at the 2028 Olympic Games. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2023, 18, 104–107. [CrossRef]

- Penichet-Tomas, A.; Jimenez-Olmedo, J.M.; Pueo, B.; Olaya-Cuartero, J. Physiological and Mechanical Responses to a Graded Exercise Test in Traditional Rowing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 3664. [CrossRef]

- Astridge, D.J.; Peeling, P.; Goods, P.S.R.; Girard, O.; Watts, S.P.; Dennis, M.C.; Binnie, M.J. Shifting the Energy Toward Los Angeles: Comparing the Energetic Contribution and Pacing Approach Between 2000- and 1500-m Maximal Ergometer Rowing. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2024, 19, 133–141. [CrossRef]

| Author | Year | Number of participants |

Rowers Classification |

Age | Aim (s) of the study | |

| Male | Female | |||||

| Cosgrove et al. [28] | 1999 | 13 | Class C | 19.9 ± 0.6 | Examine the relationship between selected physiological variables and rowing performance as determined by a 2,000-m time-trial. | |

| Gillies and Bell [29] | 2000 | 10 | 22 | Class C | 22 ± 5 | Examine the physiological requirements of a simulated 2,000-m rowing trial to determine if this relationship differs between genders. |

| Ingham et al. [1] | 2002 | 19 HWT and 4 LWT | 13 HWT and 5 LWT | Class A | 25.8 ± 4.1 | Examine the aerobic and anaerobic determinants of performance during 2,000-m of rowing on an ergometer. |

| Riechman et al. [12] | 2002 | 12 | Class C | 21.3 ± 3.6 | Develop a model to predict 2,000-m indoor rowing performance time from sprint performance. | |

| Bourdin et al. [26] | 2004 | 31 HWT | Class B | 23 ± 3.7 | Test the hypothesis that power peak is an overall index of rowing performance and study the influence of selected physiological variables. | |

| 23 LWT | 22.6 ± 3.7 | |||||

| Messonnier et al. [37] | 2004 | 9 | Class A | 22 ± 3 | Relate rowing performance and associated physiological variables and investigate the specificity of the training intensity on these variables. | |

| 12 | Class C | |||||

| Bourdon et al. [25] | 2009 | 2 | 8 | Class A | 20.9 ± 2.1 | Determine whether incremental exercise and a 2,000-m time trial could be combined into a single test without affecting the validity of the blood lactate threshold and/or performance data collected. |

| Mikulic [9] | 2009 | 25 | Class A | 22.2 ± 4.8 | Examine the anthropometric and metabolic determinants of performance during 6,000-m of rowing on an ergometer. | |

| Shimoda et al. [30] | 2009 | 16 | Class C | 20.7 ± 0.9 | This prompted us to suppose dependence on stroke consistency, aerobic capacity, leg extension power and rowing performance. | |

| Izquierdo-Gabarren et al.[17] | 2010 | 24 | Class B | 28 ± 5 | Examine which one of the performance factors would be able to differentiate rowers at different standards in traditional rowing and determine the best predictors of traditional rowing performance. | |

| 22 | Class C | 23 ± 4 | ||||

| Author | Year | Number of participants |

Rowers Classification |

Age | Aim (s) of the study | |

| Male | Female | |||||

| Kendall et al. [31] | 2011 | 19 | Class C | 19.7 ± 1.4 | Assess the critical velocity test as a means of predicting 2,000-m performance and to study the effect of selected physiological variables. | |

| Cheng et al. [20] | 2012 | 18 | Class C | 17.7 ± 1.9 | Determine the test-retest reliability of the 3-minute all-out rowing test and the differences between traditional CP tests. | |

| Ingham et al. [19] | 2013 | 4 HWT and 6 LWT |

4 HWT and 4 LWT | Class C | 23.3 ± 3.1 | Examine the relationship between parameters derived from both an INCR in relation to 2,000-m ergometer rowing performance. |

| Akça [10] | 2014 | 38 | Class C | 20.1 ± 1.2 | Develop different regression models to predict 2,000-m rowing ergometer performance. | |

| Cataldo et al. [13] | 2015 | 20 | Class C | 15.2 ± 1.3 | Evaluate the relationship between the mean power during the 20-s all-out test rowing ergometer test and the 2,000-m indoor rowing performance. | |

| Otter et al. [32] | 2015 | 24 | Class C | 23 ± 1 | Assess the predictive value of the Submaximal Rowing Test on 2,000-m ergometer rowing time in competitive rowers | |

| Maciejewski et al. [11] | 2016 | 14 | Class C | 15.3 ± 0.6 | Determine whether anaerobic performance assessed from a 30-s all-out test could account for the 1,500-m rowing performance. | |

| Bourdin et al. [18] | 2017 | 43 HWT | Class B | 21.9 ± 3.7 | Point out the predictive factors of physical performance in high-level female rowers and evaluate whether the relative influence of these factors is like that observed in males. | |

| 27 LWT | 20.6 ± 2.9 | |||||

| Cerasola et al. [15] | 2020 | 15 | Class B | 15.7 ± 2.0 | Develop different regression models to predict 2,000-m rowing indoor performance time using VO2max and mean power established during a 60-s all-out test. | |

| Holmes et al. [16] | 2020 | 31 | Class C | 20.2 ± 1.1 | Examine the associations of CP from a three-minute all-out row test and peak power from the 1-Stroke with VO2peak, Wingate Test, 6,000-m and 2,000-m rowing ergometer test. | |

| Turnes et al. [33] | 2020 | 16 | 3 | Class C | 25.5 ± 10.6 | Identify the relationship between the mean PO of 2,000-m rowing ergometer performance with the peak PO obtained during an INCR, and verifying the possibility of achieving VO2max during a 2,000-m time trial and using the mean power of this test |

| Author | Year | Number of participants |

Rowers Classification |

Age | Aim (s) of the study | |

| Male | Female | |||||

| Da Silva et al. [8] | 2021 | 12 | Class B | 15.9 ± 1.0 | Develop a mathematical model capable of predicting 2,000-m performance from a 100-m maximal effort test. | |

| Jensen et al. [38] | 2021 | 7 | Class A | 25.4 ± 5.2 | (1) Compare VO2max measured in a 2,000-m test and a continuous INCR, (2) determine the linear relationship between mean power during 2,000-m and VO2max, (3) and determine the linear relationship between maximal PO measured in a continuous INCR and VO2max. | |

| Possamai et al. [7] | 2021 | 27 | Class C | 26 ± 13 | 1) Compare the intensities of maximal lactate steady state (MLSS) and CP in trained rowers 2) describe the relationship of MLSS with performances of 500-m, 1,000-m, 2,000-m and 6,000-m rowing ergometer time-trial tests | |

| 14 | Class B | |||||

| Cerasola et al. [14] | 2022 | 17 | Class B | 15.8 ± 2 | Investigate the relationship between the fixed-time 20-s and 60-s all-out tests and the fixed-distance 2,000-m indoor rowing performance. | |

| Huerta Ojeda et al. [34] | 2022 | 12 | Class C | 20.3 ± 1.6 | Describe and analyze the kinetics of ventilatory and mechanical parameters on the rowing ergometer. | |

| Huerta Ojeda et al. [35] | 2022 | 12 | Class C | 20.3 ± 1.6 | The main objective of this study was to determine the validity and reliability of the 6-min all-out test as a predictor of Maximal Aerobic Power (MAP). | |

| Mazza et al. [39] | 2023 | 10 | Class A | 23.3 ± 2.8 | Develop an equation that can be used to estimate VO2max in female rowers using the same INCR method. | |

| McGrath et al. [36] | 2023 | 11 | 20 | Class C | 25.5 ± 3.2 | The m-FTP equation could accurately predict rowing Functional Threshold Power (r-FTP) data in a more heterogeneous cohort of club-level male and female rowers |

| Author | Test | Power in W (Mean ± DS) | Time in s (Mean ± DS) | ||||||||

| Akça [10] | 1) 2,000-m | 2) Wingate Test | 2) 638 ± 41.80 | 1) 398.50 ± 20.11 | |||||||

| Bourdin et al. [26] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 462.9 ± 36.8 | |||||||||

| Bourdin et al. [18] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 275 ± 32 | |||||||||

| Bourdon et al. [25] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 430.0 ± 7.3 | |||||||||

| Cataldo et al. [13] | 1) 2,000-m | 2) 20-s | 2) 501.7 ± 113.0 | 1) 425.0 ± 25.8 | |||||||

| Cerasola et al. [14] | 1) 2,000-m | 2) 60-s | 2) 476.1 ± 91.0 | 1) 417.1± 21.8 | |||||||

| Cerasola et al. [15] | 1) 2,000-m | 2) 20-s | 3) 60-s | 2) 525.1 ± 113.7 | 3) 476.1 ± 91.0 | 1) 418.5 ± 23.1 | |||||

| Cheng et al. [20] | 1) 3-min all-out | 1) EP: 269 ± 39 | |||||||||

| Cosgrove et al. [28] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) ? | |||||||||

| Da Silva et al. [8] | 1) 2,000-m | 2) 100-m | 1) 235.9 ± 29.0 | 2) 376.9 ± 62.7 | |||||||

| Gillies and Bell [29] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 475.1 ± 7.4 | |||||||||

| Holmes et al. [16] | 1) 2,000-m | 2) 6,000-m | 3) 3-min all-out | 3) EP: 232.61 ± 31.27 | 1) 444.96 ± 10.83 2) 1432.73 ± 35.71 | ||||||

| Huerta Ojeda et al. [34] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 431.4 ± 12.7 | |||||||||

| Huerta Ojeda et al. [35] | 1) 6-min | 1) 289.83 ± 20.91 | |||||||||

| Ingham et al. [1] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) ? | |||||||||

| Ingham et al. [19] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 346.5 ± 75.5 | |||||||||

| Izquierdo-Gabarren et al. [17] | 1) 2,000-m | 2) 6-min | 2) 272.69 ± 30 | 1) 386 ± 10.47 | |||||||

| Author | Test(s) | Power in W (Mean ± DS) | Time in s (Mean ± DS) | ||||||||

| Jensen et al. [38] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 333 ± 69 | |||||||||

| Kendall et al. [31] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 467.6 ± 17.8 | |||||||||

| Maciejewski et al. [11] | 1) 1,500-m | 2) Wingate Test | 1) 279.7 ± 49.1 | 2) 429.2 ± 92. | |||||||

| Mazza et al. [39] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) ? | |||||||||

| McGrath et al. [36] | 1) 6-min | 1) 230 ± 64 | |||||||||

| Messonnier et al. [37] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) MP: 432 ± 12 | |||||||||

| Mikulic [9] | 1) 6,000-m | 1) 1195.4 ± 36.1 | |||||||||

| Otter et al. [32] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 389 ± 14 | |||||||||

| Possamai et al. [7] | 1) 2,000-m | 2) 6,000-m 3) 500-m 4) 1,000-m | 1) 317 ± 38 | 2) 258 ± 28 | 3) 499 ± 47 | 4) 372 ± 40 | |||||

| Riechman et al. [12] | 1) 2,000-m | 2) Wingate Test | 2) 368 ± 60.0 | 1) 466.8 ± 12.3 | |||||||

| Shimoda et al. [30] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 409.3 ± 1.2 | |||||||||

| Turnes et al. [33] | 1) 2,000-m | 1) 284.2 ± 49.9 | |||||||||

| Author | INCR | Main findings | |

| Maximal Power | VO2max | ||

| Akça [10] | Wingate mean power correlated with 2,000-m time (r = -0.796; p<0.01) | ||

| Bourdin et al. [26] | INCR disc. | Peak power in INCR correlated with 2,000-m mean power (r =0,92; p<0.0001), VO2max correlated with 2,000-m mean power (r = 0.84; p<0.0001) and with INCR peak power (r = 0.84; p < 0.0001) | |

| 441.6 ± 33.9 W | 5.68 ± 0.32 L/min | ||

| Bourdin et al. [18] | INCR disc. | Peak power in INCR correlated with 2000-m mean power (r = 0.88; p < 0.001), VO2max correlated with 2000-m performance (r = 0.83; p<0.001) and with INCR peak power (r = 0.81; p < 0.001) | |

| 278 ± 29 W | 3.68 ± 0.30 L/min | ||

| Bourdon et al. [25] | INCR disc. | 2,000-m mean power correlated with INCR disc. VO2max (r = 0.99; p = 0,22) | |

| MP: 286.7 ± 16.8 | 4.23 ± 0.22 L/min | ||

| Cataldo et al. [13] | INCR cont. | 2000-m mean power correlated with 20-s mean power (r = -0.947; p<0.001) VO2max correlated with 2000-m mean power (r = -0.884; p<0.0001) | |

| ? | 4.62 ± 0.66 L/min | ||

| Cerasola et al. [14] | INCR cont. | 2000-m mean power correlated with 60-s mean power (r = -0.943; p<0.0001) and with VO2max (r = -0.761; p<0.0001) | |

| ? | 4.66 ± 0.84 L/min | ||

| Cerasola et al. [15] | 2000-m mean power correlated with 60-s mean power (r = -0.914; p<0.0001) and 20-s mean power (r = -0.920; p< 0.0001) | ||

| Cheng et al. [20] | INCR disc. (CP test) | 3-min all-out correlated with Critical Power (r =0.745; p < 0.05), 3-min all-out correlated with VO2max (r=0.664, p<0.05) | |

| ? | ? | ||

| Cosgrove et al. [28] | INCR disc. | VO2max correlated with 2,000-m velocity (r =0.85; p<0.001); PO at lactate threshold correlated with 2,000-m velocity (r=0.73; p<0.004) | |

| ? | ? | ||

| INCR cont. | |||

| ? | 4.5 ± 0.4 L/min | ||

| Da Silva et al. [8] | 100-m mean power correlated with 2000-m mean power (r = 0.734; p=0.006) | ||

| Author | INCR | Main findings | |

| Maximal Power | VO2max | ||

| Gillies and Bell [29] | INCR cont. | 2,000-m time correlated with VO2max (r =0.96, p<0.05) and with PO at VO2max (r=0.83; p<0.05) | |

| ? | 3.52 ± 0.84 L/min | ||

| Holmes et al. [16] | 3-min mean power correlated with 6,000-m time (r=-0.62; p<0.001) and 2000-m time (r=-0.61; p<0.001), 1 maximal stroke power correlated with 6000-m time (r=-0.63; p<0.001) and 2000-m time (r=-0.62; p<0.001) | ||

| Huerta Ojeda et al. [34] | INCR cont. | VO2max in INCR and 2000-m have high correlation (p<0.05) | |

| PO at VO2max: 334.7 ± 20.2 |

4.07 ± 0.26 L/min | ||

| Huerta Ojeda et al. [35] | INCR cont. | VO2max in INCR correlated with 6-min VO2max (p=0.16), maximal aerobic power correlated with de PO at VO2max in 6-min test (p=0.0001) and Mean Power (p=0.004) | |

| PO at VO2max: 325.54 ± 39.82 W |

4.09 ± 0.26 L/min | ||

| Ingham et al. [1] | INCR disc. | 2000-m performance correlated with power of 5 Maximal Strokes (r=0.95; p<0.001) with VO2max (r=0.93; p<0.001) and with the power in 4 mmol/L of the INCR (r=0.92; p<0.001) | |

| ? | |||

| Ingham et al. [19] | INCR disc. | 2,000-m power correlated with INCR cont. Maximum minute power (r = 0.98; p<0.05), VO2max correlated with the power associated with VO2max in INCR disc. (r = 0.90; p<0.05) and VO2max of INCR cont. (r = 0.88; p<0.05) | |

| PO at VO2max: 285.0 ± 44.5 W |

4.62 ± 0.82 L/min | ||

| INCR cont. | |||

| MMP: 352.0 ± 68.2 | 4.67 ± 0.85 L/min | ||

| Izquierdo-Gabarren et al. [17] | INCR disc. | Power at 4 mmol/L correlated with 20-min (r = 0.65; p<0.01) and with 10 maximal strokes power (r = 0.5; p<0.05) | |

| PO at 4 mmol/L: 253.2 ± 34 |

|||

| Jensen et al. [38] | INCR disc. | 2,000-m mean power correlated with INCR disc. Maximum power (p<0.001) and 2,000-m VO2max correlated with INCR disc. VO2max (p=0.51) | |

| 350 ± 65 W | 4.81 ± 0.78 L/min | ||

| Kendall et al. [31] | INCR cont. | 2000-m performance correlated with critical velocity (r=0.886; p<0.001) and VO2max correlated with 2000-m performance (r=-0.923, p<0.001) | |

| 261 ± 27 | 3.14 ± 0.31 L/min | ||

| Author | INCR | Main findings | |

| Maximal Power | VO2max | ||

| Maciejewski et al. [11] | Wingate mean power correlated with 1,500-m mean power (r = 0.83; p<0.0001) | ||

| Mazza et al. [39] | INCR disc. | Predicted and measured VO2max had a high correlation in female rowers (r = 0.97; p<0.001) | |

| T: 843 ± 57 s | 3.50 ± 0.60 L/min | ||

| McGrath et al. [36] | INCR disc. | The estimated FTP with INCR disc. test correlated with calculated in a 20-min test (r=0.98) | |

| PP: 286 ± 77 | ? | ||

| Messonnier et al. [37] | INCR disc. | INCR disc. test power correlated with 2,000-m mean power (r = 0.73; p < 0.001) and INCR disc. test VO2max correlated with 2,000-m VO2max (r = 0.54, p < 0.01) | |

| ? | 5.32 ± 0.14 L/min | ||

| Mikulic [9] | INCR disc. | INCR disc. power at VO2max and 6000-m power at VO2max (r = -0.732; p < 0.01) and INCR disc. power and 6,000-m time (r = -0.484, p < 0.05) | |

| PO at VO2max: 423.8 ± 38.1 |

5.50 ± 0.30 L/min | ||

| Nevill et al. [41] | The 2,000-m performance have correlation with VO2max (r=0.94), power at VO2max (r = 0.96) and 5 maximal strokes peak power (r = 0.94) | ||

| Otter et al. [32] | INCR cont. | The SmRT was able to accurately predict 2,000-m rowing time when performed on an indoor rowing ergometer. Stage 1 power (70% of HRmax) with 2,000-m (r = -0.73), Stage 2 power (80% of HRmax) with 2,000-m (r = -0.85) and Stage 3 power (90% of HRmax) with 2,000-m (r = -0.93). | |

| 290 ± 44 W | 5.3 ± 0.4 L/min | ||

| Possamai et al. [7] | INCR disc. | Critical power correlated with MLSS (p<0.001). 500-m mean power with MLSS (r = 0.65), 1,000-m mean power with MLSS (r = -0.86), 2,000-m mean power with MLSS (r = 0.78) and 6,000-m mean power with MLSS (r = 0.39) | |

| 308 ± 37 W | 4.19 ± 0.39 L/min | ||

| INCR cont. | |||

| 311 ± 35 W | 4.08 ± 0.47 L/min | ||

| Riechman et al. [12] | INCR disc. | Wingate mean power correlated with 2,000-m mean power (r = -0.870; p < 0.001) INCR disc. power at LT correlated with 2,000-m mean power (r = -0.822; p < 0.001) and INCR disc. VO2max correlated with 2,000-m mean power (r = 0.502) | |

| PO at LT: 138 ± 27.2 | 3.18 ± 0.35 L/min | ||

| Shimoda et al. [30] | INCR cont. | VO2max correlated with 2000-m time (r = - 0.61; p = 0.012) | |

| ? | 4.1 ± 0.4 L/min | ||

| Turnes et al. [33] | INCR disc. | INCR disc. peak power correlated with 2,000-m mean power (r = 0.978; p < 0.01) and INCR disc. VO2max correlated with 2,000-m mean power (r = 0.883; p < 0.01) | |

| 284.8 ± 44.7 | 4.61 ± 0.62 L/min | ||

| Type of test | ||

| Distance [2,000-m] | n=30 [23] | |

| INCR | Discontinuous | n=16 |

| Continuous | n=11 | |

| Time | n=12 | |

| Maximal Strokes | n=3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).