1. Introduction

Forests, covering about 31 % of Earth’s land surface (FAO, 2020), are critical for biodiversity, climate regulation, and ecosystem services that sustain human well-being (Anandita et al., 2024). They store more carbon than the atmosphere, regulate hydrological cycles, and provide habitat for diverse species. Yet forests face mounting pressures from land-use change, overexploitation, and climate-driven shifts in temperature and precipitation (Sarkissian and Kutia, 2024). For managers and policymakers, assessing climate impacts on productivity, mortality, and species composition is essential for adaptive strategies that safeguard ecosystem services, support local livelihoods, and inform evidence-based policy (FAO, 2020; Au et al., 2023).

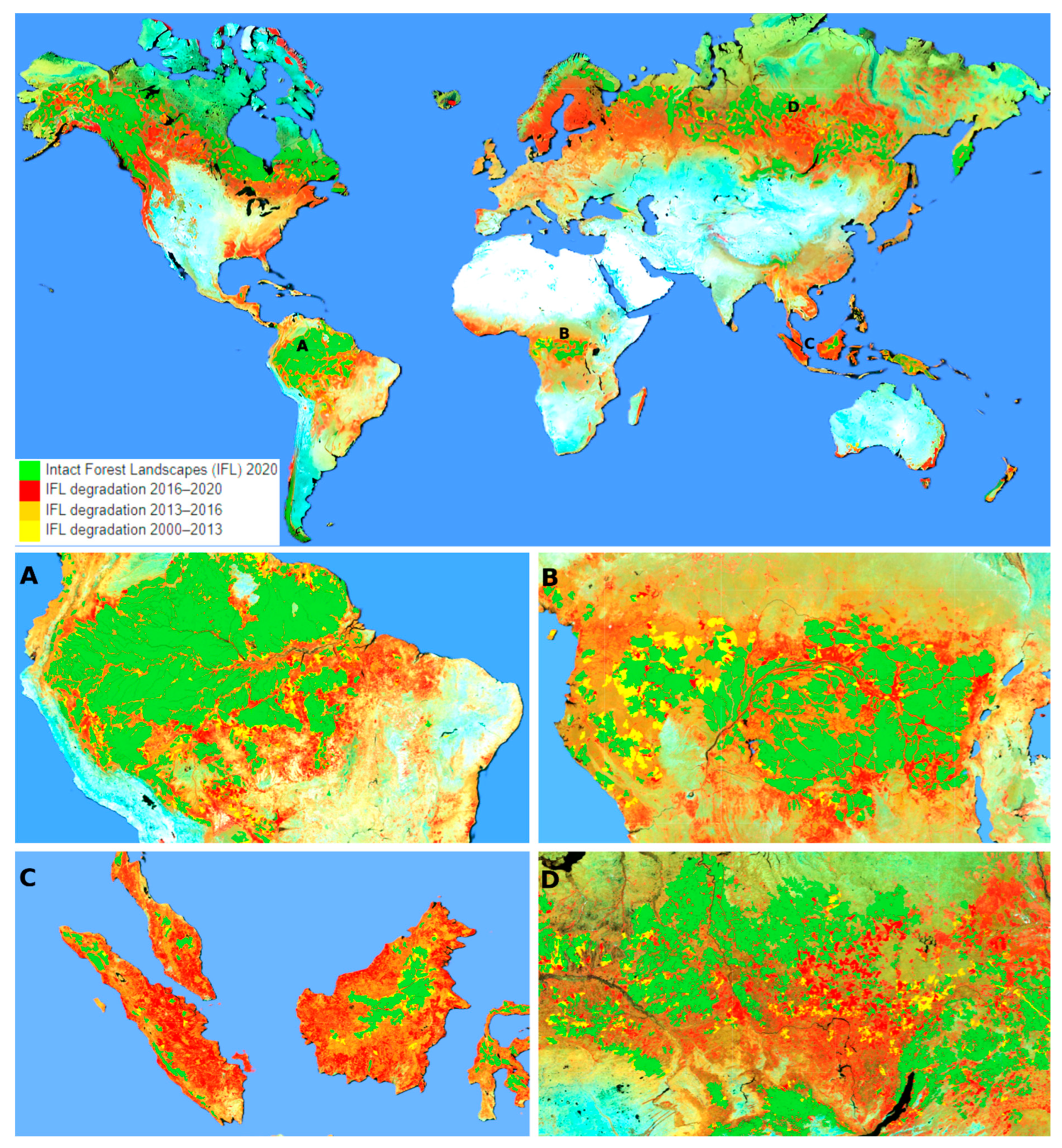

Ground-based inventories and permanent sample plots remain indispensable for monitoring forest structure and composition (Kulicki et al., 2025; Das, 2024). However, their limited spatial coverage, high costs, and logistical challenges—especially in remote regions—restrict their effectiveness for near-real-time detection of disturbances, invasive species, or climate-induced dieback (Coops et al., 2023). Integrating these field data with spatially continuous remote-sensing observations has therefore become a priority. Global assessments of forest cover loss between 2000 and 2020 (Fig. 1) highlight both the magnitude and spatial–temporal complexity of these changes, underscoring the need for regionally tailored monitoring approaches that contribute to global climate and biodiversity assessments.

Recent advances in satellite and airborne sensing have expanded capacity to monitor canopy traits and dynamics. Multispectral sensors such as Landsat and Sentinel-2 provide vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI, EVI, red-edge metrics) as proxies for canopy greenness, phenology, and photosynthetic activity (Wang et al., 2017). Hyperspectral systems extend these capabilities to foliar biochemical traits and species discrimination, while active sensors—synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and LiDAR—offer all-weather, three-dimensional perspectives for biomass estimation, structural profiling, and post-disturbance recovery (Santoro et al., 2022).

Ecosystem modelling has likewise advanced from conceptual frameworks to process-based simulators of coupled carbon, water, and nutrient cycles (Bueno De Mesquita et al., 2018). Models such as LPJ, ED2, and ORCHIDEE simulate forest responses to climate variability, disturbance regimes, and management interventions (Hall et al., 2019). Increasingly, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are applied to multi-sensor datasets to map biomass, predict disturbance patterns, and detect early-warning signals of stress (Reichstein et al., 2019). Hybrid approaches that combine process-based models with ML residual correction improve predictive accuracy, while explainable AI enhances interpretability (Ryo et al., 2021).

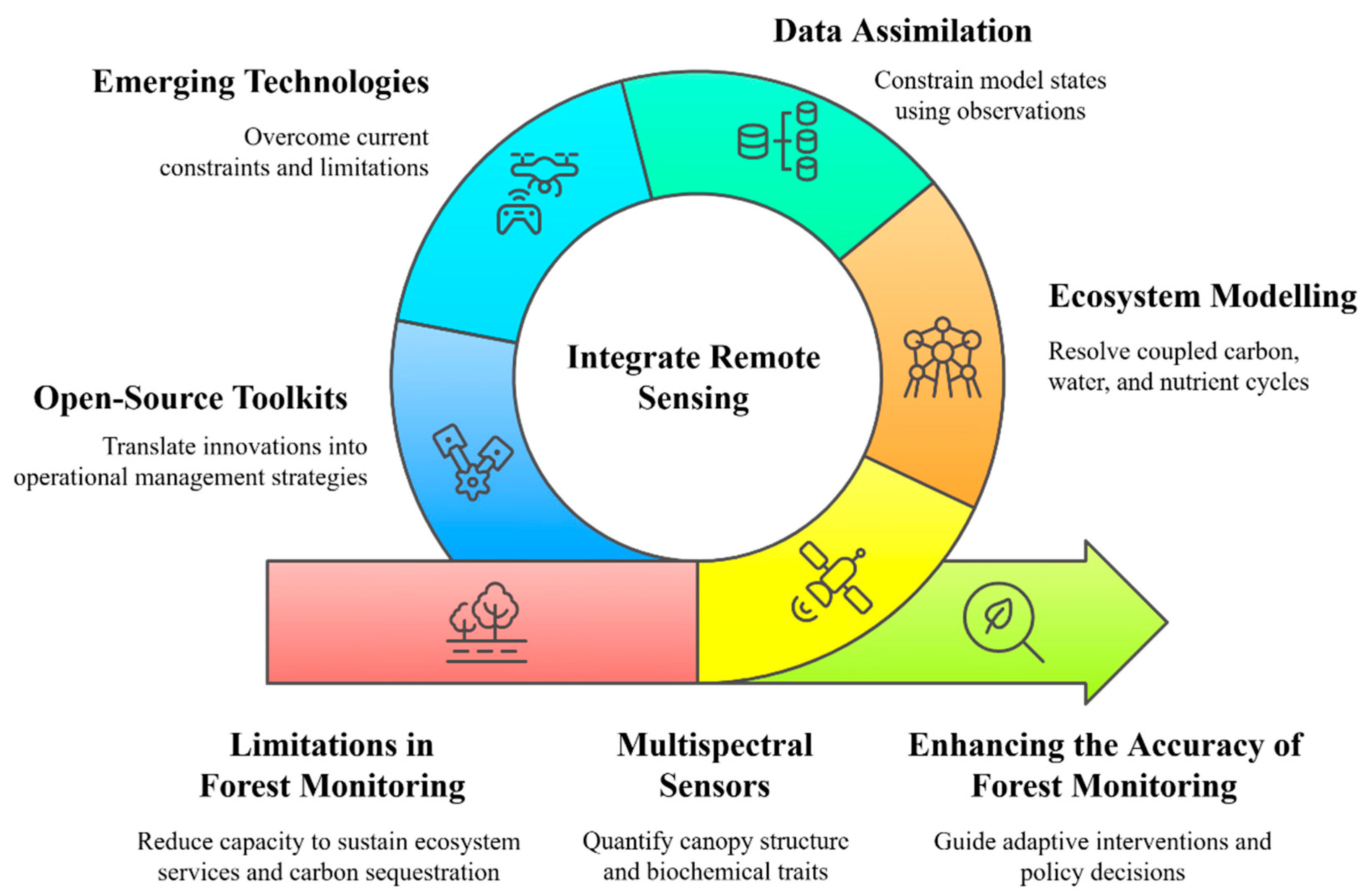

Emerging digital-twin frameworks integrate multi-sensor observations, ecosystem models, and data assimilation methods to generate continuously updated, spatially explicit representations of forest systems (Liu et al., 2023). These systems enable real-time scenario testing for forest health, productivity, and carbon accounting, providing decision-support for wildfire mitigation, biodiversity conservation, and climate-adaptive planning. Fig. 2 illustrates the development pathway toward operational digital-twin forests. However, adoption remains constrained by data heterogeneity, mismatched resolutions, computational demands, and challenges in communicating uncertainty (Ye et al., 2021). Addressing these barriers through co-developed platforms, standardised protocols, and user-friendly analytics will be essential for broad uptake.

Figure 1.

Global forest cover loss (2000–2020) from Landsat: intact forests (green) and degradation by epoch—2000–2013 (yellow), 2013–2016 (orange), 2016–2020 (red). Examples: (A) Amazon, (B) African tropics, (C) Southeast Asia, (D) Siberian boreal (Hansen et al., 2024).

Figure 1.

Global forest cover loss (2000–2020) from Landsat: intact forests (green) and degradation by epoch—2000–2013 (yellow), 2013–2016 (orange), 2016–2020 (red). Examples: (A) Amazon, (B) African tropics, (C) Southeast Asia, (D) Siberian boreal (Hansen et al., 2024).

This review synthesises recent developments in high-resolution remote sensing, ecosystem modelling, and their integration into digital-twin systems for climate-resilient forests. We evaluate the strengths and limitations of current approaches, highlight innovations such as federated learning and edge computing, and outline research priorities to accelerate operational deployment, with a focus on linking technological advances to societal benefits, policy frameworks, and sustainable forest management.

Figure 2.

Thematic components of digital-twin forest development: monitoring limits, canopy sensing, ecosystem modelling, data assimilation, emerging technologies, open-source tools, and adaptive management pathways.

Figure 2.

Thematic components of digital-twin forest development: monitoring limits, canopy sensing, ecosystem modelling, data assimilation, emerging technologies, open-source tools, and adaptive management pathways.

2. Methodology

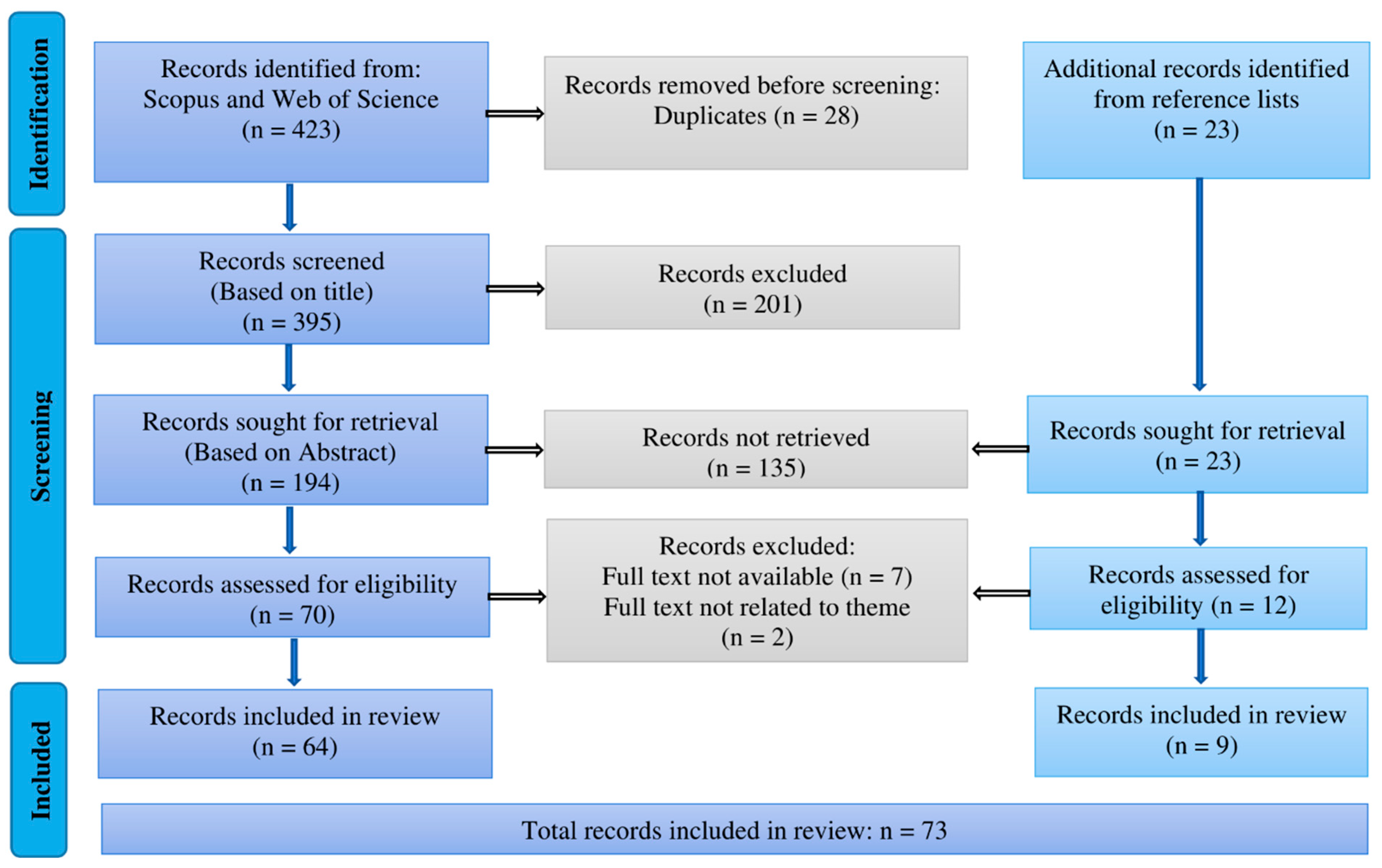

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Page et al., 2021) to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and minimize bias. The scope was restricted to peer-reviewed studies published between January 2016 and June 2025 that integrated remote-sensing data with ecosystem modelling to investigate climate-driven forest dynamics, with emphasis on management and conservation. The process consisted of three phases—identification, screening, and inclusion—summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 3).

Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection were queried using Boolean operators to combine controlled vocabulary and free-text keywords across three domains: (i) remote-sensing platforms (e.g., LiDAR, SAR, hyperspectral, multispectral, UAV); (ii) ecosystem modelling approaches (e.g., Dynamic Global Vegetation Models [DGVMs], process-based models, machine-learning surrogates); and (iii) forest-dynamics contexts (e.g., carbon fluxes, disturbance recovery, climate adaptation). Searches were limited to English-language journal articles. Reference lists of key reviews were screened, and forward citation tracking was conducted to capture recent developments (Haddaway et al., 2018).

Figure 3.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process for the systematic review.

Figure 3.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process for the systematic review.

Studies were included if they: (i) addressed terrestrial forest ecosystems under climate or disturbance drivers; (ii) integrated at least one remote-sensing dataset with an ecosystem model; and (iii) incorporated data assimilation or explicit model–data coupling. Exclusion criteria comprised studies limited to sensor calibration, non-forest biomes, or conceptual frameworks without empirical validation. Disagreements on eligibility were resolved by consensus. For each study, metadata were extracted on location, biome, spatial extent, sensing platform, modelling framework, assimilation method, validation strategy, performance metrics, and applications (Hall et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2023). Outcomes were coded by linkages to ecosystem processes, ecosystem-service provision, and policy targets such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), ensuring relevance to both scientific and decision-making communities.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics, regression for temporal trends, and chi-square tests for associations between biome type and platform selection. Analyses were conducted in R (v4.3.2; tidyverse, stats, ggplot2), with significance set at p < 0.05. While PRISMA enhanced rigour, limitations include restriction to English-language, peer-reviewed literature, exclusion of studies published after June 2025, and persistent challenges in integrating heterogeneous datasets and managing computational demands. These constraints are particularly acute in resource-limited contexts and biodiversity-rich regions, where monitoring capacity is most urgently needed.

3. Literature synthesis and discussion

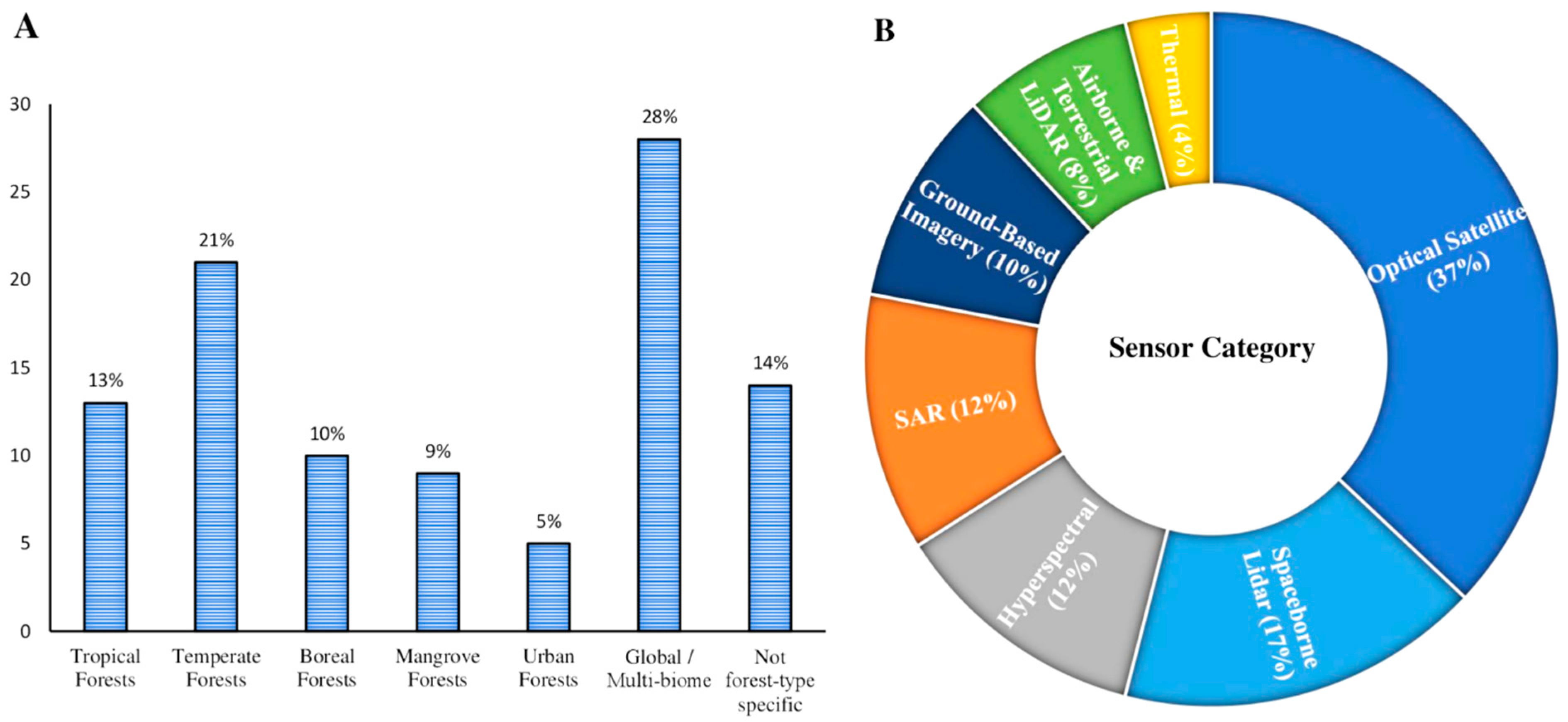

Descriptive analysis revealed uneven biome representation, with temperate forests most frequently studied (21 %), while tropical (13 %) and boreal (10 %) forests were under-represented. Mangrove (9 %), urban (5 %), global/multi-biome (28 %), and non-specific forest types (14 %) comprised the remainder. Platform usage was similarly skewed, dominated by optical satellite sensors (37 %), followed by spaceborne LiDAR (17 %), SAR (12 %), hyperspectral sensors (12 %), airborne/terrestrial LiDAR (8 %), ground-based imagery (10 %), and thermal sensors (4 %) (Fig. 4). Publication trends showed a significant annual increase (β = 0.86, p = 0.005), reflecting the accelerating integration of high-resolution remote sensing with ecosystem modelling. Chi-square analysis confirmed a non-random distribution of sensing platforms across biomes (χ2 = 15.68, df = 6, p = 0.027), with SAR disproportionately applied in tropical settings and optical sensors predominant in temperate zones. These disparities mirror infrastructure gaps noted by Haddaway et al. (2018) and highlight the need for targeted investment in biodiversity-rich, under-monitored regions to support equitable digital-twin deployment.

Figure 4.

(A) Geographic focus by forest biome: tropical, temperate, boreal, mangrove, urban, global/multi-biome, and non-specific. (B) Primary remote-sensing categories: optical, LiDAR (spaceborne/terrestrial), hyperspectral, SAR, ground-based, and thermal.

Figure 4.

(A) Geographic focus by forest biome: tropical, temperate, boreal, mangrove, urban, global/multi-biome, and non-specific. (B) Primary remote-sensing categories: optical, LiDAR (spaceborne/terrestrial), hyperspectral, SAR, ground-based, and thermal.

3.1. Emerging remote-sensing tools

Recent advances are transforming forest monitoring from plot-scale inventories into global, near-real-time systems that directly support management and policy. Miniaturisation of sensors, proliferation of satellite constellations, UAV fleets, and cloud-native analytics now enable high-frequency, multi-scale observation of structural and physiological change (Table 1).

Small satellite constellations (e.g., PlanetScope, SkySat) provide daily 3–5 m multispectral imagery for disturbance detection, fire-scar mapping, phenological tracking, and recovery assessment (Hethcoat et al., 2019), though spectral depth and calibration remain limiting. Hyperspectral missions such as ESA’s EnMAP and Italy’s PRISMA deliver 30 m imagery across hundreds of bands, enabling retrieval of foliar pigments, nitrogen, and lignin (Mohammed et al., 2019). Upcoming missions—NASA’s SBG and ESA’s CHIME—will enhance temporal resolution for operational forest-health monitoring.

Table 1.

Emerging remote-sensing tools for forest-dynamics monitoring.

Table 1.

Emerging remote-sensing tools for forest-dynamics monitoring.

| Tools |

Sensor type |

Spatial/temporal scale |

Capabilities |

Representative applications |

References |

| CubeSat constellations |

PlanetScope, SkySat |

3–5 m/daily |

Near daily multispectral change detection |

Deforestation fronts, phenology shifts, post fire regrowth |

Hethcoat et al., 2019 |

| Imaging spectroscopy |

EnMAP, PRISMA |

30 m/2–5 days |

Foliar trait retrieval (chlorophyll, N, lignin) |

Early drought stress detection, species mapping |

Mohammed et al., 2019 |

| Solar induced fluorescence (SIF) |

OCO 2, OCO 3, FLEX |

1–2 km (OCO); 300 m (FLEX)/daily |

Proxy for photosynthesis (GPP) |

Basin scale GPP anomalies, drought forecasting |

Fang et al., 2025 |

| Spaceborne LiDAR |

GEDI (ISS), ICESat 2 |

25–70 m footprints/repeat |

Vertical structure, canopy height, biomass |

Global vertical complexity, carbon stocks |

Tang et al., 2019 |

| SAR (emerging missions) |

NISAR (L/S band) |

10–25 m/12 days |

Biomass sensitivity, all weather mapping |

Biomass change in cloudy tropics, disturbance detection |

Cartus and Santoro, 2019 |

| UAV multi/hyperspectral |

Custom UAV mounted sensors |

0.05–1 m/campaign |

Fine scale canopy reflectance, traits, health |

Plot level leaf chemistry, early disease warning |

Dash et al., 2017 |

Solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) from NASA’s OCO-2 and OCO-3 provides a direct proxy for photosynthesis, complementing greenness indices in estimating gross primary productivity (Fang et al., 2025). ESA’s FLEX mission (launch 2025) will extend this capability with daily 300 m coverage.

LiDAR systems remain central for quantifying vertical structure and biomass. NASA’s GEDI provides 25 m footprint canopy-height profiles, while ICESat-2 offers photon-counting transects (Tang et al., 2019). Airborne and UAV-based LiDAR bridge scales, supporting biodiversity models, habitat assessments, and REDD+ carbon accounting (Dubayah et al., 2020; Savinelli et al., 2024; Thapa et al., 2025).

SAR missions (e.g., NISAR, RADARSAT Constellation) provide all-weather monitoring of biomass, disturbance, and soil moisture (Cartus and Santoro, 2019). SAR–LiDAR fusion improves biomass estimation in dense tropical forests where optical data are limited (Rodríguez Veiga et al., 2019).

At finer scales, UAV-mounted multispectral and hyperspectral systems (Dash et al., 2017) deliver centimetre-scale trait and stress mapping for precision forestry, including pest detection and site-specific management. UAV datasets are also critical for calibration and validation of satellite products (Massey et al., 2023).

Proximal sensing networks and IoT-enabled systems extend monitoring into the ground layer (Yan et al., 2021). Low-cost spectroradiometers, thermal imagers, and microclimate stations feed real-time data into inventories and participatory monitoring. Thermal infrared sensing from NASA’s ECOSTRESS and UAV-mounted microbolometers (Manase et al., 2025) detect canopy-temperature anomalies linked to hydraulic stress.

Edge computing and cloud platforms are increasingly central to digital-twin forestry. Innovations include CubeSats with onboard GPUs for in-orbit classification (Langer et al., 2023), UAV-mounted AI modules for real-time processing (Xia et al., 2022), and scalable infrastructures such as Google Earth Engine (Gorelick et al., 2017), AWS, and Open Data Cube. Containerised machine-learning workflows improve reproducibility, while platforms such as NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier and AWS IoT Greengrass extend GPU-accelerated inference and secure offline operation to the forest edge.

Figure 5.

Overview of emerging remote sensing platforms for high-resolution forest monitoring, including proximal sensors, CubeSats, spaceborne LiDAR, SAR, thermal infrared, hyperspectral imagers, SIF missions, UAV systems, and edge-computing architectures.

Figure 5.

Overview of emerging remote sensing platforms for high-resolution forest monitoring, including proximal sensors, CubeSats, spaceborne LiDAR, SAR, thermal infrared, hyperspectral imagers, SIF missions, UAV systems, and edge-computing architectures.

Multi-sensor fusion—via machine-learning downscaling, physics-informed neural networks, and Bayesian hierarchical models—produces coherent structural and functional maps with reduced uncertainty in canopy height, leaf area index, and water stress (Reichstein et al., 2019; Massey et al., 2023). Adoption of interoperable workflows and open data standards will be critical to embedding these tools into operational digital-twin systems, delivering actionable intelligence for adaptive management, biodiversity conservation, and climate-resilient policy frameworks (Fig. 5).

3.2. Ecosystem modelling approaches

Ecosystem models are vital for predicting forest responses to climate variability and human pressures, supporting biodiversity conservation, carbon policy, and sustainable forestry. Evolving from empirical regressions to process-based platforms, they now integrate biogeochemical, physiological, and demographic processes to simulate carbon, water, and nutrient fluxes alongside growth, mortality, and species shifts (Argles et al., 2022; Blanco and Lo, 2023). Beyond theory, these models inform vulnerability mapping, ecosystem-service projections, and resilience assessments that guide biodiversity conservation and climate-adaptation strategies. Table 2 outlines key approaches, scales, processes, assimilation methods, exemplar platforms, and contributions to ecological understanding.

Table 2.

Ecosystem-modelling approaches for climate-driven forest dynamics.

Table 2.

Ecosystem-modelling approaches for climate-driven forest dynamics.

| Modelling approach |

Operational scale |

Main processes |

Calibration methods |

Example models and references |

| Process based land surface models |

Plot to regional (~10−4–102 km2) |

Photosynthesis, respiration, transpiration, carbon–water balance |

EnKF, variational DA |

CLM; JULES (Li et al., 2021) |

| Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs) |

Regional to global (102–107 km2) |

PFT competition, allocation, mortality, succession |

Spin up with remote sensing initialization |

LPJ GUESS; ORCHIDEE (Argles et al., 2022) |

| Individual based/gap models |

Stand to landscape (10−3–102 km2) |

Tree demography, recruitment, competition, gap dynamics |

Calibration using TLS/UAV point clouds |

SORTIE ND; FORMIND (Rödig et al., 2017) |

| Trait based continuous spectrum models |

Patch to regional (10−2–103 km2) |

Trait tradeoffs (leaf, wood, height spectra) |

Bayesian estimation |

JeDi (Díaz et al., 2016) |

| Statistical/ML surrogates |

Plot to biome (10−4–106 km2) |

Empirical relationships (biomass, distribution, disturbance) |

Cross validation, emulator training |

MaxEnt; Random Forest (Angione et al., 2022) |

| Bayesian DA frameworks |

Plot to regional (10−3–103 km2) |

State and parameter uncertainty |

Particle filters; MCMC |

PEcAn; probabilistic EnKF (Bach and Ghil, 2023) |

Process-based land surface models (e.g., CLM, JULES) quantify photosynthesis, respiration, transpiration, and carbon allocation at daily to sub-daily scales. Incorporating plant hydraulic schemes improves prediction of drought thresholds and productivity loss, supporting climate-adapted plantation design (Li et al., 2021). Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs) such as LPJ-GUESS and ORCHIDEE embed these routines within Earth-system frameworks to simulate vegetation distribution and biogeochemical cycling, underpinning biome-shift projections and national carbon accounting (Argles et al., 2022).

Trait-based models (e.g., JeDi, aDGVM2) represent communities along continuous spectra of traits such as leaf area, wood density, and height, linking functional diversity to carbon storage and drought tolerance (Díaz et al., 2016). Statistical and machine-learning approaches—including species distribution models, Gaussian process emulators, and neural-network surrogates—offer rapid predictions of habitat suitability and emulate process-model outputs at lower computational cost (Angione et al., 2022).

Bayesian hierarchical models and assimilation frameworks (e.g., PEcAn) integrate observations with process-based models via probabilistic inference, reducing uncertainty in projections of carbon sequestration and hydrological regulation (Bach and Ghil, 2023). Coupled hydrology–vegetation models (e.g., HYDRUS-Plant, SPAC) simulate soil–plant–atmosphere water exchanges to identify hydraulic-failure thresholds, informing drought-risk zoning. Spatially explicit landscape models (e.g., LANDIS II) simulate disturbance–succession dynamics and management interventions across heterogeneous terrain, aiding fire management and connectivity conservation (Furniss et al., 2023).

Figure 6.

Overview of ecosystem-modelling approaches for forest ecology, including process-based and DGVM frameworks, demographic and trait-based models, statistical/ML methods, Bayesian inference, hydrology–vegetation coupling, spatially explicit models, and hybrid ensembles for climate-resilient prediction.

Figure 6.

Overview of ecosystem-modelling approaches for forest ecology, including process-based and DGVM frameworks, demographic and trait-based models, statistical/ML methods, Bayesian inference, hydrology–vegetation coupling, spatially explicit models, and hybrid ensembles for climate-resilient prediction.

Hybrid models combine mechanistic cores with statistical surrogates, balancing interpretability with computational efficiency (Futter et al., 2023). Ensemble frameworks (e.g., ISIMIP) compare outputs from multiple model types under harmonised forcing scenarios, identifying robust patterns of vulnerability and resilience. Together, this spectrum of approaches provides a robust basis for assessing forest dynamics across scales (Fig. 6).

Integration with high-resolution remote sensing, in situ monitoring, and cloud-computing infrastructure is enabling operational digital-twin forests for near-real-time monitoring of ecosystem state and services (Hajek et al., 2022; Blanco and Lo, 2023). Remaining gaps include below-ground processes and intraspecific trait variation, which limit predictive robustness. Bridging these gaps will be essential for translating modelling advances into actionable insights for forest governance, restoration planning, and climate-resilient policy frameworks.

3.3. Data assimilation approaches

Data assimilation (DA) integrates remote-sensing and in situ observations with ecosystem models to produce physically consistent, observation-constrained state estimates and projections. In forest ecology, DA enhances representation of canopy structure, biomass, and phenology, supporting ecosystem-service valuation and resilience forecasting under climate extremes. Table 3 summarises major DA frameworks, data sources, applications, strengths, and limitations.

The Ensemble Kalman Filter (EnKF) is a sequential Monte Carlo method that estimates forecast error covariances from ensembles (Fadaei et al., 2024). In forests, EnKF has assimilated MODIS LAI and FAPAR into models such as CLM for near-real-time phenology and carbon-flux updates (Su et al., 2024). Ensemble sizes (102–103) risk sampling errors, mitigated through localisation and inflation (Houtekamer and Zhang, 2016).

Table 3.

Data-assimilation frameworks integrating remote sensing into forest-ecosystem models.

Table 3.

Data-assimilation frameworks integrating remote sensing into forest-ecosystem models.

| Technique |

Data source |

Model application |

Strengths |

Limitations |

References |

| Ensemble Kalman Filter (EnKF) |

MODIS LAI, FAPAR |

Land surface models (e.g., CLM) |

Real time phenology and carbon flux updates |

Sampling error; spurious long-range correlations |

Houtekamer & Zhang, 2016; Su et al., 2024 |

| Particle Filter |

OCO 2 SIF |

Photosynthetic capacity modules |

Tightens GPP related parameters under stress |

Computationally demanding in high dimensions |

Sun et al., 2018; Bacour et al., 2019 |

| Four dimensional variational (4D Var) |

Multi sensor time series (e.g., MODIS, SIF) |

DGVMs, landscape simulators |

Coherent multi day assimilation |

Requires adjoint; computationally intensive |

Bannister, 2017; Dong et al., 2022 |

| Hybrid ensemble–variational |

Combined observations (optical, SIF, LiDAR) |

Hybrid DA schemes for ecosystem models |

Robustness in nonlinear regimes |

Complex; few forest benchmarks |

Carrassi et al., 2018 |

Particle Filters (PFs) represent full, non-Gaussian posteriors via weighted particles, making them suitable for threshold-driven processes such as die-off and regeneration. PFs have assimilated OCO-2 SIF to constrain photosynthesis and improve GPP forecasts during heat–drought stress (Sun et al., 2018; Bacour et al., 2019). Their computational cost can be reduced through dimensionality reduction and resampling (Elfring et al., 2021).

Variational methods (4D-Var) minimise a cost function over a time window, enforcing model dynamics via tangent-linear and adjoint operators (Dong et al., 2022). Assimilation of MODIS LAI and SIF into DGVMs yields consistent phenology and biomass projections, although adjoint development remains computationally demanding (Bannister, 2017).

Hybrid ensemble–variational schemes combine flow-dependent ensemble covariances with static variational covariances, improving canopy and growth forecasts under variable disturbances such as fire or pest outbreaks, while balancing realism and efficiency (Carrassi et al., 2018).

Each DA method has trade-offs: EnKF is sensitive to small ensembles, EnKF and 4D-Var struggle with strong nonlinearity, while PFs handle non-Gaussianity but are computationally expensive. Few direct intercomparisons exist, and scaling DA for operational ecosystem-service monitoring and climate-adaptation planning will require coordinated benchmarking across forest types, climates, and management scenarios. Future research should prioritise intercomparison studies, scalable workflows, and integration with policy-relevant indicators to ensure that DA frameworks deliver transparent, decision-relevant outputs for sustainable forest management.

3.4. Integration of remote sensing and modelling

The integration of high-resolution remote-sensing (RS) with process-based ecosystem models is central to quantifying forest dynamics, ecosystem services, and resilience under global change (Reichstein et al., 2019). RS provides spatially continuous measurements of canopy height, LAI, FAPAR, and SIF that inform model states and parameters, while models mechanistically represent biogeochemical and hydrological processes to extend forecasts beyond observations. Coupling these data streams reduces uncertainty, improves ecological realism, and supports scenario-based projections for carbon budgets, biodiversity conservation, ecosystem-service provision, and climate-adaptation planning. Table 4 summarises key RS platforms and modelling applications in forest ecosystem studies.

Multi-platform RS systems provide complementary perspectives. Sentinel-2 and Landsat deliver LAI and FAPAR time series for biomass and productivity mapping (Netsianda and Mhangara, 2025); airborne hyperspectral campaigns support trait-based modelling (Heidarian et al., 2024); CubeSat constellations enable near-real-time carbon-flux assimilation (Houborg and McCabe, 2018); and terrestrial/UAV LiDAR provides fine-scale structural data for parameterising microclimate and heterogeneity modules in DGVMs (Savinelli et al., 2024; Thapa et al., 2025). Model initialisation with Earth-observation (EO) products improves predictive skill and reduces spin-up time. GEDI LiDAR characterises vertical canopy profiles (Dubayah et al., 2020), while MODIS-derived LAI/FAPAR constrains phenology and photosynthetic capacity (Yan et al., 2021).

Table 4.

Key remote-sensing platforms and modelling applications (operational).

Table 4.

Key remote-sensing platforms and modelling applications (operational).

| Platform |

Sensor or output |

Resolution (spatial/temporal) |

Modelling application |

References |

| Satellite (Sentinel 2) |

Multispectral (NDVI, FAPAR) |

10 m/5–10 days |

Raster based biomass and productivity modelling |

Netsianda & Mhangara, 2025 |

| Hyperspectral aircraft |

Canopy chemistry indices |

1–5 m/campaign |

Trait based process models |

Heidarian et al., 2024 |

| CubeSat constellation (PlanetScope) |

Multispectral (RedEdge, NIR) |

3–5 m/daily–sub daily revisit |

Near real time carbon flux assimilation |

Houborg & McCabe, 2018 |

| UAV photogrammetry |

3D point clouds, orthomosaics |

~0.05 m/campaign |

High resolution structure inputs |

Ecke et al., 2022 |

| Terrestrial LiDAR (TLS) |

Stem and understory structure |

<0.01 m/site repeat |

Microclimate and structural heterogeneity in DGVMs |

Thapa et al., 2025 |

Trait-driven parameterisation aligns mechanistic processes with observed diversity. Radiative transfer models such as PROSPECT-SAIL and SCOPE retrieve leaf optical traits (chlorophyll, specific leaf area) directly linked to physiological parameters in models like JULES and CLM (Aasen et al., 2019). Bayesian calibration using spectral indices and SIF reduces equifinality and improves transferability across biomes. Model validation against independent RS products—such as MOD17 NPP and OCO-2 SIF-derived GPP—remains essential, revealing systematic biases including drought underestimation and canopy-clumping effects (Fang et al., 2025).

Figure 7.

Digital-twin forest workflow—from uncertainty assessment and remote-sensing initialization to data assimilation, calibration, validation, and cloud-based fusion for real-time, spatially explicit forest forecasts.

Figure 7.

Digital-twin forest workflow—from uncertainty assessment and remote-sensing initialization to data assimilation, calibration, validation, and cloud-based fusion for real-time, spatially explicit forest forecasts.

Multi-sensor fusion exploits complementary strengths: GEDI LiDAR with Sentinel-1 SAR extends biomass mapping into cloudy regions (Tamiminia et al., 2024). Cloud-based frameworks such as Google Earth Engine (Gorelick et al., 2017) and PEcAn support reproducible workflows for preprocessing, parameterisation, and benchmarking.

Digital-twin forest systems merge continuous EO data with optimised model ensembles for adaptive management (Buonocore et al., 2022). Workflows integrate EO-based initialisation, multi-sensor assimilation, trait-informed calibration, and cloud-based fusion to deliver spatially explicit, near-real-time forecasts for interventions such as thinning, fire mitigation, and pest control (Fig. 7).

Challenges remain in reconciling scale mismatches, mitigating sensor noise, and managing retrieval-related uncertainties (Schutgens et al., 2016). Future advances—including hyperspectral CubeSats, advanced SAR constellations, physics-informed neural networks (Raissi et al., 2019), and IoT-enabled microclimate networks—promise finer resolution, richer trait mapping, and accelerated modelling cycles, strengthening predictive capacity for climate-resilient forest management.

3.5. Applications and Case Studies

Integrating multi-sensor remote sensing with ecosystem models provides spatially explicit, decision-ready insights for forest structure, ecosystem services, and resilience. This fusion of optical, LiDAR, SAR, hyperspectral, thermal, and UAV data with process-based or statistical models underpins climate-smart forest management.

Figure 8.

(A) Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) for drought and (B) Burning Index (BI), 1991–2020, showing links to climate-change drivers in the western United States.

Figure 8.

(A) Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) for drought and (B) Burning Index (BI), 1991–2020, showing links to climate-change drivers in the western United States.

- ▪

Amazon photosynthetic response to El Niño: Castro et al. (2020) used OCO-2 solar-induced fluorescence (SIF) to assess gross primary productivity (GPP) during the 2015–2016 El Niño. Peak-season anomalies ranged from −31.1 % to +17.6 %, reflecting heterogeneous drought impacts across ecoregions. The study highlights the sensitivity of tropical forests to climate extremes and the value of SIF for quantifying carbon-sequestration resilience.

- ▪

Post-fire recovery in the Western United States: Recovery after the 2020 Creek Fire was assessed using fused Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope reflectance data, combined with GEDI LiDAR canopy metrics. Results showed that pre-fire stand structure and early-season precipitation strongly influenced regrowth, with high-severity areas recovering less than 15% canopy cover after two years (Dubayah et al., 2020; Abatzoglou and Williams, 2016). Fig. 8 situates these recovery trajectories within their climatic context, illustrating drought (SPI) and fire-weather (Burning Index) trends for 1991–2020. These findings underscore the need for targeted restoration strategies and adaptive fire-management policies.

- ▪

Mangrove restoration and blue-carbon management: Baloloy et al. (2020) created a Mangrove Vegetation Index (MVI) from Sentinel-2 imagery, validated with field data, to map canopy cover and height in the Philippines. The approach provided biomass and blue-carbon estimates, offering a scalable tool for restoration planning, blue-carbon accounting, and coastal-zone climate-mitigation strategies.

- ▪

Proactive pathogen surveillance: Zarco-Tejada et al. (2018) demonstrated that airborne hyperspectral imagery, coupled with trait-based modelling and machine-learning classification, can detect Xylella fastidiosa infection months before visible symptoms. While applied to Mediterranean olive systems, the method is transferable to forests, enhancing early-warning capacity for biosecurity, biodiversity protection, and ecosystem-service resilience.

4. Challenges and Limitations

Despite rapid advances in remote sensing (RS) and ecosystem modelling, several persistent barriers limit their integrated application for climate-resilient forest monitoring. These challenges not only constrain the accuracy of structural characterisation, ecosystem-service quantification, and resilience projections, but also reduce the policy relevance of RS-based insights for biodiversity conservation and climate adaptation.

Data quality and uncertainty remain central. RS products are affected by retrieval errors, atmospheric interference, sensor drift, and platform-specific biases, which propagate through model initialisation and assimilation. Uncertainty in LAI and canopy-height estimates can bias simulated carbon and water fluxes, leading to misestimation of sequestration potential and evapotranspiration-driven cooling (Liu et al., 2021; Savinelli et al., 2024). These errors undermine the reliability of carbon accounting frameworks such as REDD+ and weaken the credibility of RS-derived indicators in policy contexts. Addressing this requires harmonised error-characterisation protocols, cross-sensor calibration, and coordinated field–satellite campaigns—particularly in biodiversity-rich but data-poor regions where monitoring capacity is most urgently needed.

Scale mismatches between high-resolution EO (metre to sub-metre) and coarser model grids (≥ 1 km) obscure fine-scale heterogeneity in canopy structure and species composition (Grafius et al., 2016). Aggregation masks ecologically important features such as species-specific drought responses, while statistical downscaling introduces additional uncertainty (Pu, 2021). Multi-scale fusion and adaptive gridding offer potential solutions (Povak et al., 2024), but systematic evaluation of their ecological validity across diverse biomes remains limited. Without such validation, the operational use of these methods in resilience forecasting will remain constrained.

Model structural limitations also reduce predictive accuracy under novel climate regimes. Parameterisation with historical data restricts representation of extreme heat, multi-year droughts, or compound disturbances (Hajek et al., 2022). Simplified plant functional-type schemes mask interspecific variation in hydraulic traits, leading to underestimated vulnerability and overly optimistic recovery projections (Díaz et al., 2016). This gap highlights the need for trait-based modelling approaches that explicitly capture species-level diversity and its implications for resilience.

Computational constraints further hinder integration. Assimilating large, high-frequency EO datasets is resource-intensive: spaceborne constellations and UAV campaigns generate petabyte-scale archives, while advanced assimilation methods (e.g., Ensemble Kalman Filters, Particle Filters) require repeated forward model runs, amplifying computational loads. Cloud computing and containerised workflows offer partial solutions, but access disparities between the Global North and South persist (Reichstein et al., 2019). These inequities limit the ability of institutions in biodiversity hotspots to participate in global monitoring efforts, reinforcing the digital divide.

Data assimilation complexity compounds these issues. Heterogeneous datasets—optical indices, solar-induced fluorescence (SIF), LiDAR, SAR—have distinct error structures and ecological relevance. Observation-operator mismatches and violated Gaussian/linearity assumptions increase the risk of filter divergence or overconfident projections (Bach and Ghil, 2023). Developing robust, physics-informed assimilation frameworks that can accommodate non-linearities and uncertainty propagation is therefore a pressing research need.

Interoperability gaps also hinder workflow efficiency. Disparate file formats, metadata conventions, and limited model APIs restrict reproducibility and slow collaborative innovation (Choi et al., 2023). Community-driven standards and modular architectures are essential to enable transparent, reproducible, and scalable RS–model integration.

Finally, equity and capacity constraints remain significant. Access to high-resolution data, advanced models, and high-performance computing is concentrated in well-resourced institutions, while biodiversity hotspots in the Global South often lack infrastructure and expertise, limiting conservation outcomes (Slagter et al., 2023; Das, 2025). This imbalance not only limits scientific progress but also undermines the ability of vulnerable communities to access early-warning systems for drought, fire, and pest outbreaks. Moreover, rapid technological change—sensor upgrades, algorithm evolution, and shifting modelling paradigms—creates a moving target for operational integration. Sustaining frameworks over decadal timescales requires agile, modular systems and institutional commitment to ongoing validation (Langer et al., 2023).

5. Future Perspectives

High-resolution remote sensing (RS) and ecosystem modelling are entering a transformative phase, but their promise for climate-resilient forests will only be realised if research moves beyond incremental sensor advances toward integrated, policy-relevant digital-twin frameworks. Below, we outline four interlinked priorities that define the next frontier.

5.1. Multi-Sensor Integration for Whole-System Monitoring

Emerging optical, hyperspectral, SAR, and LiDAR platforms are rapidly improving canopy-trait, biochemical, and structural retrievals (Aoyanagi et al., 2025; Quegan et al., 2019; Bolton et al., 2018). Yet each sensor class has limitations—SAR struggles in dense tropical forests, hyperspectral systems remain costly, and LiDAR coverage is spatially patchy (Rodriguez Veiga et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019). Future research must prioritise fusion architectures that combine these modalities to reduce uncertainty in biomass, carbon flux, and disturbance forecasts, thereby strengthening biodiversity conservation strategies and informing sustainable forest management. Hybrid SAR–LiDAR–hyperspectral assimilation pipelines, coupled with physics-informed machine learning (Raissi et al., 2019; Karniadakis et al., 2021), represent a critical step toward operational resilience forecasting that can directly support land-use planning, REDD+ initiatives, and national adaptation strategies.

5.2. Coupling Above- and Below-Ground Processes

Most digital-twin prototypes remain canopy-centric, overlooking root–soil–hydrology interactions that govern drought resilience and carbon turnover. Advances in ground-penetrating radar, electrical resistivity tomography, and fibre-optic sensing now allow non-invasive mapping of root architecture and soil moisture dynamics (Konings et al., 2016). Integrating these below-ground indicators with canopy stress metrics in coupled process models should be a research priority, enabling more realistic resilience thresholds and early-warning indicators (Bracco et al., 2024). Such coupled approaches are particularly relevant for tropical and semi-arid regions where drought-induced mortality threatens both local livelihoods and global carbon budgets.

5.3. Equity, Capacity, and Governance

Technological innovation risks deepening the digital divide if not matched by investment in equity and capacity building. Open-access curricula, benchmark datasets, and cloud-based code laboratories are essential (Wilkinson et al., 2016; Buonocore et al., 2022), but so too are funding models that support long-term operations, training, and maintenance (Qiu et al., 2023). Governance frameworks must ensure data sovereignty, equitable access, and interoperability through adoption of FAIR principles and community-driven APIs. Without such institutional scaffolding, digital-twin systems will remain fragmented and inaccessible, limiting their ability to support vulnerable communities in climate adaptation, disaster preparedness, and sustainable resource management.

5.4. Policy-Relevant Digital Twins

The ultimate test of digital-twin forests is their ability to inform adaptive governance. Near-real-time assimilation of EO data streams, IoT networks, and UAV-borne sensors can deliver forecasts that guide interventions—fire mitigation, pest control, targeted thinning—before resilience thresholds are crossed (Soltani et al., 2024). To be actionable, these forecasts must quantify uncertainty, align with national climate strategies, and provide metrics such as avoided emissions, biodiversity-risk indices, and water-security projections (Frieler et al., 2017; Bracco et al., 2024). Transparent, scenario-based workflows will be pivotal for bridging science and policy, ensuring that digital-twin outputs are directly integrated into climate policy, restoration planning, and ecosystem service valuation.

6. Conclusion

The integration of high-resolution remote sensing technologies with advanced ecosystem modelling frameworks is transforming our ability to monitor forest structure, quantify ecosystem services, and anticipate resilience under climate change. By coupling multispectral, hyperspectral, SAR, and LiDAR observations within robust data assimilation systems, it is now possible to detect subtle structural shifts, attribute variability in carbon–water fluxes, and provide early-warning indicators of stress.

Persistent barriers—including observation gaps, limited calibration networks, and high computational demands—still constrain large-scale deployment. Yet, advances in long-wavelength SAR, hyperspectral LiDAR, and physics-informed modelling, embedded within FAIR-compliant digital-twin frameworks, offer clear pathways toward transparent, reproducible, and decision-relevant metrics.

Realising this potential will require sustained co-design among researchers, agencies, and local stakeholders to ensure innovations are context-appropriate, equitable, and institutionally supported. Such collaboration is essential to translate technological advances into adaptive strategies that safeguard biodiversity, sustain ecosystem services, and strengthen forest resilience in a changing climate. By embedding these innovations within policy and management frameworks, digital-twin approaches can provide actionable insights that bridge science, society, and sustainability at regional to global scales.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the generous support and constructive feedback from researchers at the Global Forest Observations Initiative (GFOI), whose insights substantially enriched the scope and clarity of this review. The author also thanks the international remote sensing and ecosystem modelling community—including the developers of open-access datasets, algorithms, and processing platforms—for advancing the shared resources that made this synthesis possible. Special appreciation is extended to forest ecologists and technical staff whose meticulous work underpins the reliability of the global forest observation networks referenced herein. This work also benefited from the collaborative spirit fostered by cross-institutional partnerships and the open-data principles that continue to drive innovation in Earth system science.

References

- Aasen, H., Van Wittenberghe, S., Sabater Medina, N., Damm, A., Goulas, Y., Wieneke, S., Hueni, A., Malenovský, Z., Alonso, L., Pacheco-Labrador, J., Cendrero-Mateo, M.P., Tomelleri, E., Burkart, A., Cogliati, S., Rascher, U., Mac Arthur, A., 2019. Sun-induced chlorophyll fluorescence II: Review of passive measurement setups, protocols, and their application at the leaf to canopy level. Remote Sens. 11, 927. [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T., Williams, A.P., 2016. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 11770–11775. [CrossRef]

- Anandita, K., Sinha, A.K., Jeganathan, C., 2024. Understanding and mitigating climate change impacts on ecosystem health and functionality. Rend. Fis. Acc. Lincei. [CrossRef]

- Angione, C., Silverman, E., Yaneske, E., 2022. Using machine learning as a surrogate model for agent-based simulations. PLoS One. 17, e0263150. [CrossRef]

- Aoyanagi, Y., Doi, T., Arai, H., Shimada, Y., Yasuda, M., Yamazaki, T., Sawazaki, H., 2025. On-orbit performance and hyperspectral data processing of the TIRSAT CubeSat mission. Remote Sens. 17, 1903. [CrossRef]

- Argles, A.P.K., Moore, J.R., Cox, P.M., 2022. Dynamic global vegetation models: Searching for the balance between demographic process representation and computational tractability. PLOS Clim. 1, e0000068. [CrossRef]

- Au, J., Bloom, A.A., Parazoo, N.C., Deans, R.M., Wong, C.Y.S., Houlton, B.Z., Magney, T.S., 2023. Forest productivity recovery or collapse? Model–data integration insights on drought-induced tipping points. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 5652–5665. [CrossRef]

- Bach, E., Ghil, M., 2023. A multi-model ensemble Kalman filter for data assimilation and forecasting. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 15, e2022MS003123. [CrossRef]

- Bacour, C., Maignan, F., MacBean, N., Porcar-Castell, A., Flexas, J., Frankenberg, C., Peylin, P., Chevallier, F., Vuichard, N., Bastrikov, V., 2019. Improving estimates of gross primary productivity by assimilating solar-induced fluorescence satellite retrievals in a terrestrial biosphere model using a process-based SIF model. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 124, 3281–3306. [CrossRef]

- Baloloy, A.B., Blanco, A.C., Sta. Ana, R.R.C., Nadaoka, K., 2020. Development and application of a new mangrove vegetation index (MVI) for rapid and accurate mangrove mapping. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 166, 95–117. [CrossRef]

- Bannister, R.N., 2017. A review of operational methods of variational and ensemble-variational data assimilation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 143, 607–633. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.A., Lo, Y.H., 2023. Latest trends in modelling forest ecosystems: New approaches or just new methods? Curr. For. Rep. 9, 219–229. [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D.K., Coops, N.C., Hermosilla, T., Wulder, M.A., White, J.C., 2018. Evidence of vegetation greening at alpine treeline ecotones: three decades of Landsat spectral trends informed by lidar-derived vertical structure. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 084022. [CrossRef]

- Bracco, A., Brajard, J., Dijkstra, H.A., Hassanzadeh, P., Lessig, C., Monteleoni, C., 2024. Machine learning for the physics of climate. Nat. Rev. Phys. 7, 6–20. [CrossRef]

- Bueno De Mesquita, C.P., Tillmann, L.S., Bernard, C.D., Rosemond, K.C., Molotch, N.P., Suding, K.N., 2018. Topographic heterogeneity explains patterns of vegetation response to climate change (1972–2008) across a mountain landscape, Niwot Ridge, Colorado. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 50, e1504492. [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, L., Yates, J., Valentini, R., 2022. A proposal for a forest digital twin framework and its perspectives. For. 13, 498. [CrossRef]

- Carrassi, A., Bocquet, M., Bertino, L., Evensen, G., 2018. Data assimilation in the geosciences: An overview of methods, issues, and perspectives. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change. 9, e535. [CrossRef]

- Cartus, O., Santoro, M., 2019. Exploring combinations of multi-temporal and multi-frequency radar backscatter observations to estimate above-ground biomass of tropical forest. Remote Sens. Environ. 232, 111313. [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.O., Chen, J., Zang, C.S., Shekhar, A., Jimenez, J.C., Bhattacharjee, S., Kindu, M., Morales, V.H., Rammig, A., 2020. OCO 2 solar induced chlorophyll fluorescence variability across ecoregions of the Amazon Basin and the extreme drought effects of El Niño (2015–2016). Remote Sens. 12, 1202. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.D., Roy, B., Nguyen, J., Ahmad, R., Maghami, I., Nassar, A., Li, Z., Castronova, A.M., Malik, T., Wang, S., Goodall, J.L., 2023. Comparing containerization-based approaches for reproducible computational modeling of environmental systems. Environ. Model. Softw. 167, 105760. [CrossRef]

- Coops, N.C., Tompalski, P., Goodbody, T.R.H., Achim, A., Mulverhill, C., 2023. Framework for near real-time forest inventory using multi-source remote sensing data. For. 96, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Das, N., 2024. Tree species diversity, composition and structure in the tropical moist deciduous forest of Kadigarh National Park, Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Asian J. For. 8(1), 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Das, N., 2025. Biodiversity in forest ecosystems: Patterns, drivers, and conservation strategies. Nova Science Publishers, New York. [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.P., Watt, M.S., Pearse, G.D., Heaphy, M., Dungey, H.S., 2017. Assessing very high-resolution UAV imagery for monitoring forest health during a simulated disease outbreak. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 131, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S., Kattge, J., Cornelissen, J.H.C., Wright, I.J., Lavorel, S., Dray, S., Reu, B., Kleyer, M., Wirth, C., Colin Prentice, I., Garnier, E., Bönisch, G., Westoby, M., Poorter, H., Reich, P.B., Moles, A.T., Dickie, J., Gillison, A.N., Zanne, A.E., Chave, J., Joseph Wright, S., Sheremet’ev, S.N., Jactel, H., Baraloto, C., Cerabolini, B., Pierce, S., Shipley, B., Kirkup, D., Casanoves, F., Joswig, J.S., Günther, A., Falczuk, V., Rüger, N., Mahecha, M.D., Gorné, L.D., 2016. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature. 529, 167–171. [CrossRef]

- Dong, R., Leng, H., Zhao, J., Song, J., Liang, S., 2022. A framework for four-dimensional variational data assimilation based on machine learning. Entropy. 24, 264. [CrossRef]

- Dubayah, R., Blair, J.B., Goetz, S., Fatoyinbo, L., Hansen, M., Healey, S., Hofton, M., Hurtt, G., Kellner, J., Luthcke, S., Armston, J., Tang, H., Duncanson, L., Hancock, S., Jantz, P., Marselis, S., Patterson, P.L., Qi, W., Silva, C., 2020. The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation: High resolution laser ranging of the Earth’s forests and topography. Sci. Remote Sens. 1, 100002. [CrossRef]

- Ecke, S., Dempewolf, J., Frey, J., Schwaller, A., Endres, E., Klemmt, H.-J., Tiede, D., Seifert, T., 2022. UAV-based forest health monitoring: A systematic review. Remote Sens. 14, 3205. [CrossRef]

- Elfring, J., Torta, E., Molengraft, R., 2021. Particle filters: A hands-on tutorial. Sensors. 21, 438. [CrossRef]

- Fadaei, M., Ameri, M.J., Rafiei, Y., 2024. Constraint optimization of an integrated production model utilizing history matching and production forecast uncertainty through the ensemble Kalman filter. Sci. Rep. 14, 13589. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J., Lian, X., Ryu, Y., Jeong, S., Jiang, C., Gentine, P., 2025. A long-term reconstruction of a global photosynthesis proxy over 1982–2023 using OCO 2 SIF. Sci. Data. 12, 546. [CrossRef]

- FAO, 2020. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main report. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. [CrossRef]

- Frieler, K., Lange, S., Piontek, F., Reyer, C.P.O., Schewe, J., Warszawski, L., Zhao, F., Chini, L., Denvil, S., Emanuel, K., Geiger, T., Halladay, K., Hurtt, G., Mengel, M., Murakami, D., Ostberg, S., Popp, A., Riva, R., Stevanovic, M., Suzuki, T., Volkholz, J., Burke, E., Ciais, P., Ebi, K., Eddy, T.D., Elliott, J., Galbraith, E., Gosling, S.N., Hattermann, F., Hickler, T., Hinkel, J., Hof, C., Huber, V., Jägermeyr, J., Krysanova, V., Marcé, R., Müller Schmied, H., Mouratiadou, I., Pierson, D., Tittensor, D.P., Vautard, R., Van Vliet, M., Biber, M.F., Betts, R.A., Bodirsky, B.L., Deryng, D., Frolking, S., Jones, C.D., Lotze, H.K., Lotze-Campen, H., Sahajpal, R., Thonicke, K., Tian, H., Yamagata, Y., 2017. Assessing the impacts of 1.5 °C global warming – simulation protocol of the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP2b). Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 4321–4345. [CrossRef]

- Furniss, T.J., Povak, N.A., Hessburg, P.F., Salter, R.B., Duan, Z., Wigmosta, M., 2023. Informing climate adaptation strategies using ecological simulation models and spatial decision support tools. Front. For. Glob. Change. 6, 1269081. [CrossRef]

- Futter, M.N., Dirnböck, T., Forsius, M., Bäck, J.K., Cools, N., Diaz-Pines, E., Dick, J., Gaube, V., Gillespie, L.M., Högbom, L., Laudon, H., Mirtl, M., Nikolaidis, N., Poppe Terán, C., Skiba, U., Vereecken, H., Villwock, H., Weldon, J., Wohner, C., Alam, S.A., 2023. Leveraging research infrastructure co-location to evaluate constraints on terrestrial carbon cycling in northern European forests. Ambio. 52, 1819–1831. [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N., Hancher, M., Dixon, M., Ilyushchenko, S., Thau, D., Moore, R., 2017. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Grafius, D., Corstanje, R., Warren, P., Evans, K., Hancock, S., Harris, J., 2016. The impact of land use/land cover scale on modelling urban ecosystem services. Landsc. Ecol. 31, 1509–1522. [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R., Macura, B., Whaley, P., Pullin, A.S., 2018. ROSES reporting standards for systematic evidence syntheses: Pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ. Evid. 7, 7. [CrossRef]

- Hajek, P., Link, R.M., Nock, C.A., Bauhus, J., Gebauer, T., Gessler, A., Kovach, K., Messier, C., Paquette, A., Saurer, M., Scherer-Lorenzen, M., Rose, L., Schuldt, B., 2022. Mutually inclusive mechanisms of drought-induced tree mortality. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 3365–3378. [CrossRef]

- Hall, A., Cox, P., Huntingford, C., Klein, S., 2019. Progressing emergent constraints on future climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 269–278. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C., Potapov, P.V., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S.A., Tyukavina, A., Thau, D., Stehman, S.V., Goetz, S.J., Loveland, T.R., Kommareddy, A., Egorov, A., Chini, L., Justice, C.O., Townshend, J.R.G., 2024. Global Forest Change 2000–2023 (v1.11). University of Maryland, Department of Geographical Sciences. https://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest (accessed 30 June 2025).

- Heidarian Dehkordi, R., Candiani, G., Nutini, F., Carotenuto, F., Gioli, B., Cesaraccio, C., Boschetti, M., 2024. Towards an improved high-throughput phenotyping approach: Utilizing MLRA and dimensionality reduction techniques for transferring hyperspectral proximal-based model to airborne images. Remote Sens. 16, 492. [CrossRef]

- Hethcoat, M.G., Edwards, D.P., Carreiras, J.M.B., Bryant, R.G., França, F.M., Quegan, S., 2019. A machine learning approach to map tropical selective logging. Remote Sens. Environ. 221, 569–582. [CrossRef]

- Houborg, R., McCabe, M., 2018. Daily retrieval of NDVI and LAI at 3 m resolution via the fusion of CubeSat, Landsat, and MODIS data. Remote Sens. 10, 890. [CrossRef]

- Houtekamer, P.L., Zhang, F., 2016. Review of the ensemble Kalman filter for atmospheric data assimilation. Mon. Weather Rev. 144, 4489–4532. [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E., Kevrekidis, I.G., Lu, L., Perdikaris, P., Wang, S., Yang, L., 2021. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 422–440. [CrossRef]

- Konings, A.G., Piles, M., Rötzer, K., McColl, K.A., Chan, S.K., Entekhabi, D., 2016. Vegetation optical depth and scattering albedo retrieval using time series of dual-polarized L-band radiometer observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 172, 178–189. [CrossRef]

- Kulicki, M., Cabo, C., Trzciński, T., Będkowski, J., Stereńczak, K., 2024. Artificial intelligence and terrestrial point clouds for forest monitoring. Curr. For. Rep. 11, 5. [CrossRef]

- Langer, D.D., Orlandić, M., Bakken, S., Birkeland, R., Garrett, J.L., Johansen, T.A., Sørensen, A.J., 2023. Robust and reconfigurable on-board processing for a hyperspectral imaging small satellite. Remote Sens. 15, 3756. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Yang, Z., Matheny, A.M., Zheng, H., Swenson, S.C., Lawrence, D.M., Barlage, M., Yan, B., McDowell, N.G., Leung, L.R., 2021. Representation of plant hydraulics in the Noah MP land surface model: Model development and multiscale evaluation. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 13, e2020MS002214. [CrossRef]

- Liu, A., Cheng, X., Chen, Z., 2021. Performance evaluation of GEDI and ICESat 2 laser altimeter data for terrain and canopy height retrievals. Remote Sens. Environ. 264, 112571. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Calders, K., Origo, N., Disney, M., Meunier, F., Woodgate, W., Gastellu Etchegorry, J. P., Nightingale, J., Honkavaara, E., Hakala, T., Markelin, L., Verbeeck, H., 2023. Reconstructing the digital twin of forests from a 3D library: Quantifying trade offs for radiative transfer modeling. Remote Sens. Environ. 298, 113832. [CrossRef]

- Manase, A., Manyevere, A., Elbasit, M.A.M.A., Mashamaite, C., 2025. The use of UAV based systems in monitoring forest health: Potentials and challenges. Sci. Afr. 28, e02724. [CrossRef]

- Massey, R., Berner, L.T., Foster, A.C., Goetz, S.J., Vepakomma, U., 2023. Remote sensing tools for monitoring forests and tracking their dynamics, in: Girona, M.M., Morin, H., Gauthier, S., Bergeron, Y. (Eds.), Boreal Forests in the Face of Climate Change. Springer Int. Publ., Cham, pp. 637–655. [CrossRef]

- Milodowski, D., Smallman, T., Williams, M., 2023. Scale variance in the carbon dynamics of fragmented, mixed use landscapes estimated using model–data fusion. Biogeosciences 20, 3301–3320. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, G.H., Colombo, R., Middleton, E.M., Rascher, U., Van Der Tol, C., Nedbal, L., Goulas, Y., Pérez Priego, O., Damm, A., Meroni, M., Joiner, J., Cogliati, S., Verhoef, W., Malenovský, Z., Gastellu Etchegorry, J.P., Miller, J.R., Guanter, L., Moreno, J., Moya, I., Berry, J.A., Frankenberg, C., Zarco Tejada, P.J., 2019. Remote sensing of solar induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) in vegetation: 50 years of progress. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111177. [CrossRef]

- Netsianda, A., Mhangara, P., 2025. Aboveground biomass estimation in a grassland ecosystem using Sentinel 2 satellite imagery and machine learning algorithms. Environ. Monit. Assess. 197, 138. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., Moher, D., 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Povak, N.A., Manley, P.N., Wilson, K.N., 2024. Quantitative methods for integrating climate adaptation strategies into spatial decision support models. Front. For. Glob. Change 7, 1286937. [CrossRef]

- Pu, R., 2021. Assessing scaling effect in downscaling land surface temperature in a heterogenous urban environment. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 96, 102256. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H., Zhang, H., Lei, K., Zhang, H., Hu, X., 2023. Forest digital twin: A new tool for forest management practices based on spatio temporal data, 3D simulation engine, and intelligent interactive environment. Comput. Electron. Agric. 215, 108416. [CrossRef]

- Quegan, S., Le Toan, T., Chave, J., Dall, J., Exbrayat, J.F., Minh, D.H.T., Lomas, M., D’Alessandro, M.M., Paillou, P., Papathanassiou, K., Rocca, F., Saatchi, S., Scipal, K., Shugart, H., Smallman, T.L., Soja, M.J., Tebaldini, S., Ulander, L., Villard, L., Williams, M., 2019. The European Space Agency BIOMASS mission: Measuring forest above ground biomass from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 227, 44–60. [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P., Karniadakis, G.E., 2019. Physics informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707. [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M., Camps Valls, G., Stevens, B., Jung, M., Denzler, J., Carvalhais, N., Prabhat, 2019. Deep learning and process understanding for data driven Earth system science. Nature 566, 195–204. [CrossRef]

- Rödig, E., Huth, A., Bohn, F., Rebmann, C., Cuntz, M., 2017. Estimating the carbon fluxes of forests with an individual based forest model. For. Ecosyst. 4, 4. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Veiga, P., Quegan, S., Carreiras, J., Persson, H.J., Fransson, J.E.S., Hoscilo, A., Ziółkowski, D., Stereńczak, K., Lohberger, S., Stängel, M., Berninger, A., Siegert, F., Avitabile, V., Herold, M., Mermoz, S., Bouvet, A., Le Toan, T., Carvalhais, N., Santoro, M., Cartus, O., Rauste, Y., Mathieu, R., Asner, G.P., Thiel, C., Pathe, C., Schmullius, C., Seifert, F.M., Tansey, K., Balzter, H., 2019. Forest biomass retrieval approaches from Earth observation in different biomes. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 77, 53–68. [CrossRef]

- Ryo, M., Angelov, B., Mammola, S., Kass, J.M., Benito, B.M., Hartig, F., 2021. Explainable artificial intelligence enhances the ecological interpretability of black box species distribution models. Ecography 44, 199–205. [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M., Cartus, O., Wegmüller, U., Besnard, S., Carvalhais, N., Araza, A., Herold, M., Liang, J., Cavlovic, J., Engdahl, M.E., 2022. Global estimation of above ground biomass from spaceborne C band scatterometer observations aided by LiDAR metrics of vegetation structure. Remote Sens. Environ. 279, 113114. [CrossRef]

- Sarkissian, A.J., Kutia, M., 2024. Editorial: Sustainable forest management under climate change conditions — A focus on biodiversity conservation and forest restoration. Front. For. Glob. Change 7, 1533425. [CrossRef]

- Savinelli, B., Tagliabue, G., Vignali, L., Garzonio, R., Gentili, R., Panigada, C., Rossini, M., 2024. Integrating drone-based LiDAR and multispectral data for tree monitoring. Drones 8, 744. [CrossRef]

- Schutgens, N., Gryspeerdt, E., Weigum, N., Tsyro, S., Goto, D., Schulz, M., Stier, P., 2016. Will a perfect model agree with perfect observations? The impact of spatial sampling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 6335–6353. [CrossRef]

- Slagter, B., Reiche, J., Marcos, D., Mullissa, A., Lossou, E., Peña Claros, M., Herold, M., 2023. Monitoring direct drivers of small scale tropical forest disturbance in near real time with Sentinel 1 and 2 data. Remote Sens. Environ. 295, 113655. [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.S., Ataie Ashtiani, B., Al Bitar, A., Simmons, C.T., Younes, A., Fahs, M., 2024. Assimilating multivariate remote sensing data into a fully coupled subsurface land surface hydrological model. J. Hydrol. 641, 131812. [CrossRef]

- Su, W., Wang, B., Chen, H., Zhu, L., Zheng, X., Chen, S.X., 2024. A new global carbon flux estimation methodology by assimilation of both in situ and satellite CO2 observations. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 287. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Frankenberg, C., Jung, M., Joiner, J., Guanter, L., Köhler, P., Magney, T., 2018. Overview of solar induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) from the Orbiting Carbon Observatory 2: Retrieval, cross mission comparison, and global monitoring for GPP. Remote Sens. Environ. 209, 808–823. [CrossRef]

- Tamiminia, H., Salehi, B., Mahdianpari, M., Goulden, T., 2024. State wide forest canopy height and aboveground biomass map for New York with 10 m resolution, integrating GEDI, Sentinel 1, and Sentinel 2 data. Ecol. Inform. 79, 102404. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H., Armston, J., Hancock, S., Marselis, S., Goetz, S., Dubayah, R., 2019. Characterizing global forest canopy cover distribution using spaceborne lidar. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111262. [CrossRef]

- Thapa, N., Narine, L.L., Wilson, A.E., 2025. Forest aboveground biomass estimation using airborne LiDAR: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. For. 123, 389–412. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Schaaf, C.B., Sun, Q., Kim, J., Erb, A.M., Gao, F., Román, M.O., Yang, Y., Petroy, S., Taylor, J.R., Masek, J.G., Morisette, J.T., Zhang, X., Papuga, S.A., 2017. Monitoring land surface albedo and vegetation dynamics using high spatial and temporal resolution synthetic time series from Landsat and the MODIS BRDF/NBAR/albedo product. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 59, 104–117. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I.J., Appleton, G., Axton, M., Baak, A., Blomberg, N., Boiten, J. W., Da Silva Santos, L.B., Bourne, P.E., Bouwman, J., Brookes, A.J., Clark, T., Crosas, M., Dillo, I., Dumon, O., Edmunds, S., Evelo, C.T., Finkers, R., Gonzalez Beltran, A., Gray, A.J.G., Groth, P., Goble, C., Grethe, J.S., Heringa, J., ’T Hoen, P.A.C., Hooft, R., Kuhn, T., Kok, R., Kok, J., Lusher, S.J., Martone, M.E., Mons, A., Packer, A.L., Persson, B., Rocca Serra, P., Roos, M., Van Schaik, R., Sansone, S. A., Schultes, E., Sengstag, T., Slater, T., Strawn, G., Swertz, M.A., Thompson, M., Van Der Lei, J., Van Mulligen, E., Velterop, J., Waagmeester, A., Wittenburg, P., Wolstencroft, K., Zhao, J., Mons, B., 2016. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X., Fattah, S.M.M., Babar, M.A., 2022. A survey on UAV enabled edge computing: Resource management perspective. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z., Guo, Z., Serbin, S.P., Song, G., Zhao, Y., Chen, Y., Wu, S., Wang, J., Wang, X., Li, J., Wang, B., Wu, Y., Su, Y., Wang, H., Rogers, A., Liu, L., Wu, J., 2021. Spectroscopy outperforms leaf trait relationships for predicting photosynthetic capacity across different forest types. New Phytol. 232, 134–147. [CrossRef]

- Ye, S., Rogan, J., Zhu, Z., Eastman, J.R., 2021. A near real time approach for monitoring forest disturbance using Landsat time series: Stochastic continuous change detection. Remote Sens. Environ. 252, 112167. [CrossRef]

- Zarco Tejada, P.J., Camino, C., Beck, P.S.A., Calderon, R., Hornero, A., Hernández Clemente, R., Kattenborn, T., Montes Borrego, M., Susca, L., Morelli, M., Gonzalez Dugo, V., North, P.R.J., Landa, B.B., Boscia, D., Saponari, M., Navas Cortes, J.A., 2018. Previsual symptoms of Xylella fastidiosa infection revealed in spectral plant trait alterations. Nat. Plants 4, 432–439. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., Wulder, M.A., Roy, D.P., Woodcock, C.E., Hansen, M.C., Radeloff, V.C., Healey, S.P., Schaaf, C., Hostert, P., Strobl, P., Pekel, J.F., Lymburner, L., Pahlevan, N., Scambos, T.A., 2019. Benefits of the free and open Landsat data policy. Remote Sens. Environ. 224, 382–385. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).