1. Introduction

The 2008 financial crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic and, more recently, the Russian-Ukrainian war have propelled research into the relationship between sovereign debt and financial stability. The literature on this topic is explained by two main theories. The first, known as the “vicious circle phenomenon”, argues that government budgetary problems exacerbate the financial instability of banks and vice versa. Indeed, a significant increase in public debt can lead to higher borrowing rates and a decline in the value of government bonds held by banks, triggering new banking problems in a vicious circle (Acharya and Steffen, 2015).

In the same vein, Valenzuela (2025) identifies this vicious circle between banking and sovereign risks: banks holding government bonds see their solvency threatened during debt crises. Other authors, such as Capponi et al. (2022), James (2024) and Fernandez-Perez et al. (2025), highlight economic activity as the main transmission channel. According to them, this cycle can lead to fiscal contraction, reducing economic activity, increasing non-performing loans, thereby worsening the situation of banks and increasing fiscal costs. The work of Marfo et al. (2025) has shown that the recent banking crisis has significantly worsened Ghana’s public debt level.

The second equally important theory is the “original sin” hypothesis developed by Eichengreen et al. 2005) and Borensztein et al. (2005). According to these authors, when a significant portion of a country’s public debt is denominated in foreign currency, it makes the country vulnerable to exchange rate shocks because a depreciation of the national currency can trigger a sovereign debt crisis by increasing the burden of foreign currency-denominated debt, leading to sovereign default. Recently, Athukorala (2024) showed that excessive reliance on short-term foreign borrowing exacerbated the 2022 crisis in Sri Lanka. Ghulam (2025) adds that external debt tolerance thresholds vary across regions, with complex interactions between political and economic factors. Finally, Reinhart (2002) argues that a debt crisis can lead to a downgrade in credit ratings and trigger a currency crisis. Indeed, an initial sovereign default can trigger a currency crisis if the central bank pursues expansionary monetary policies to avoid a recession following the withdrawal of foreign capital.

With regard to systemic risk and contagion, several studies show that in an environment of inter-institutional dependence, the failure of a major player can have a domino effect with repercussions for the entire system (Demirgüç-Kunt and Detragiache, 1998; Lim et al., 2011; Claessens and Kodres, 2014). For De Bandt and Hartmann (2002), any definition of systemic risk should include widespread events in the banking and financial spheres, as well as payment and settlement systems. They encourage the strict application of macroprudential policies and the adoption of more robust risk management practices, thereby helping to reduce non-performing loans (Dell’Ariccia et al., 2012). Furthermore, Reis (2021) shows that tightening these policies facilitates public debt refinancing by supporting bond prices and reducing bailout risks, but it can also restrict credit, slow economic activity and reduce future tax revenues.

Empirical research on the links between banks and sovereign debt has long focused on a key question: the influence of sovereign credit default swaps on bank stability. Pioneering work by Feyen and Zuccardi (2019) and Hardy and Zhu (2023) has mainly explored this phenomenon in emerging economies, where public debt volatility is more pronounced. In Europe, researchers such as Andreeva and Vlassopoulos (2019) and Fratzscher and Rieth (2019) have analyzed the impact of the 2008 financial crisis, showing how tensions on Greek and Spanish CDS weakened local banks. Others, such as Fiordelisi et al. (2020), have studied how regulatory reforms, such as the Basel rules, have changed this complex relationship.

However, the recent failures of several US banks, such as Silicon Valley Bank, serve as a reminder that the danger is not limited to fragile countries or periods of crisis. Even in developed economies, where governments enjoy strong credit ratings, excessive exposure of banks to public debt can become a ticking time bomb. Studies on peripheral European countries, such as those by Acharya et al. (2012), Li and Zinna (2018) and Gomez-Puig et al. (2019), had already warned of these risks. Numerous studies have examined the effects of financial crises on bond yields and the banking sector, as well as the determinants of banks’ exposure to sovereign debt (Basse et al., 2014; Sibbertsen et al., 2014; Moro, 2014; Gruppe et al., 2017; Baselga-Pascual et al., 2025).

Other approaches have also been used to synthesize sovereign credit risk, sovereign debt and financial markets. The first attempt at a bibliometric synthesis of the literature on financial stability and its interactions with other macroeconomic aggregates was made by Silva et al. (2017). Bahoo (2020) used a corpus of 819 research articles from the Web of Science database covering the period 1969 to 2019. Similarly, Tabak et al. (2021) explored the relationship between interbank financial networks and the financial system using articles from different sources with a bibliometric approach based on the trends and characteristics of published scientific articles.

However, the study by Zabavnik and Verbic (2021) consisted of analyzing the interdependencies between financial stability and macroeconomic variables by applying a bibliometric methodology. Through a bibliometric analysis using data extracted from Web of Science and Scopus, Bajaj et al. (2022) examined the dynamic link between sovereign credit risk and financial markets. They identified three components that include the determinants, interactions, and prices of sovereign credit risk and other financial markets. Their analysis is based on co-citation, mapping, and keyword trends. In addition, the study by Khan et al. (2022) conducts a bibliometric review of 121 bibliometric articles in the field of finance. Their results identify traditional finance journals that are particularly prominent in the publication of bibliometric studies. They also find a high abundance of bibliometric journals in sustainable and Islamic finance, credit risk, financial crises, and efficiency measurement.

Other recent bibliometric studies focus on banking regulation and performance (Mehrotra et al., 2022), the relationship between the Covid-19 pandemic and finance (Boubaker et al., 2023), financial stability (Ballouk et al., 2024) and climate finance (Carè and Weber 2023; Wang et al., 2025; Mohamad, 2025). Finally, Pacelli et al., (2025) examine the relationship between climate change and financial stability covering the period 2008-2024. Their results show that climate risk management is essential to maintaining financial market stability. Finally, Alaminos et al. (2024) look at financial speculation and its impact on financial markets using a bibliometric approach based on 2,642 articles published between 1971 and 2021.

Bibliometric analysis is a quantitative approach used to study the evolution of research in a specific field. It is based on two techniques, namely “performance analysis” and “scientific mapping” (Zupic and Čater, 2015; Donthu et al., 2021). According to these authors, the first technique involves studying the contributions of authors, institutions, countries and journals in the field of research using the number of citations and publications. The second technique allows the relationships between authors, countries and journals to be studied using an analysis of citations, co-citations, co-keywords, co-authors and bibliographic coupling. Bibliometric analysis is rapidly expanding among researchers in multidisciplinary fields thanks to the accessibility of online databases such as Scopus Elsevier, Web of Science, OpenAlex and Dimensions, which make it easier for researchers to find relevant articles and save them in various formats, on the one hand, and free software such as RStudio, VOSviewer and CitNetExplorer, on the other. However, for rigorous analysis, the Scopus and Web of Science data sources are highly recommended for their quality and periodic coverage.

The aim of this study is to provide a comprehensive understanding of global trends and to identify the frontiers of research on the link between sovereign debt and financial stability. Specifically, it seeks to identify emerging themes and the most influential authors and sources; to identify gaps in knowledge; and to provide guidance for future research. It makes four main contributions to the literature on the relationship between sovereign debt and financial stability. First, it quantifies and empirically validates the catalytic impact of the European sovereign debt crisis (2009-2012) on the field of research using 2,969 articles and showing that this event transformed a niche topic into a central area of financial macroeconomics. Second, it identifies and demonstrates distinct models of scientific production and collaboration. Third, it identifies where current cutting-edge research stands. Finally, it identifies emerging themes and research gaps and provides guidance for future research.

2. Methodology and Data

2.1. Data Collection

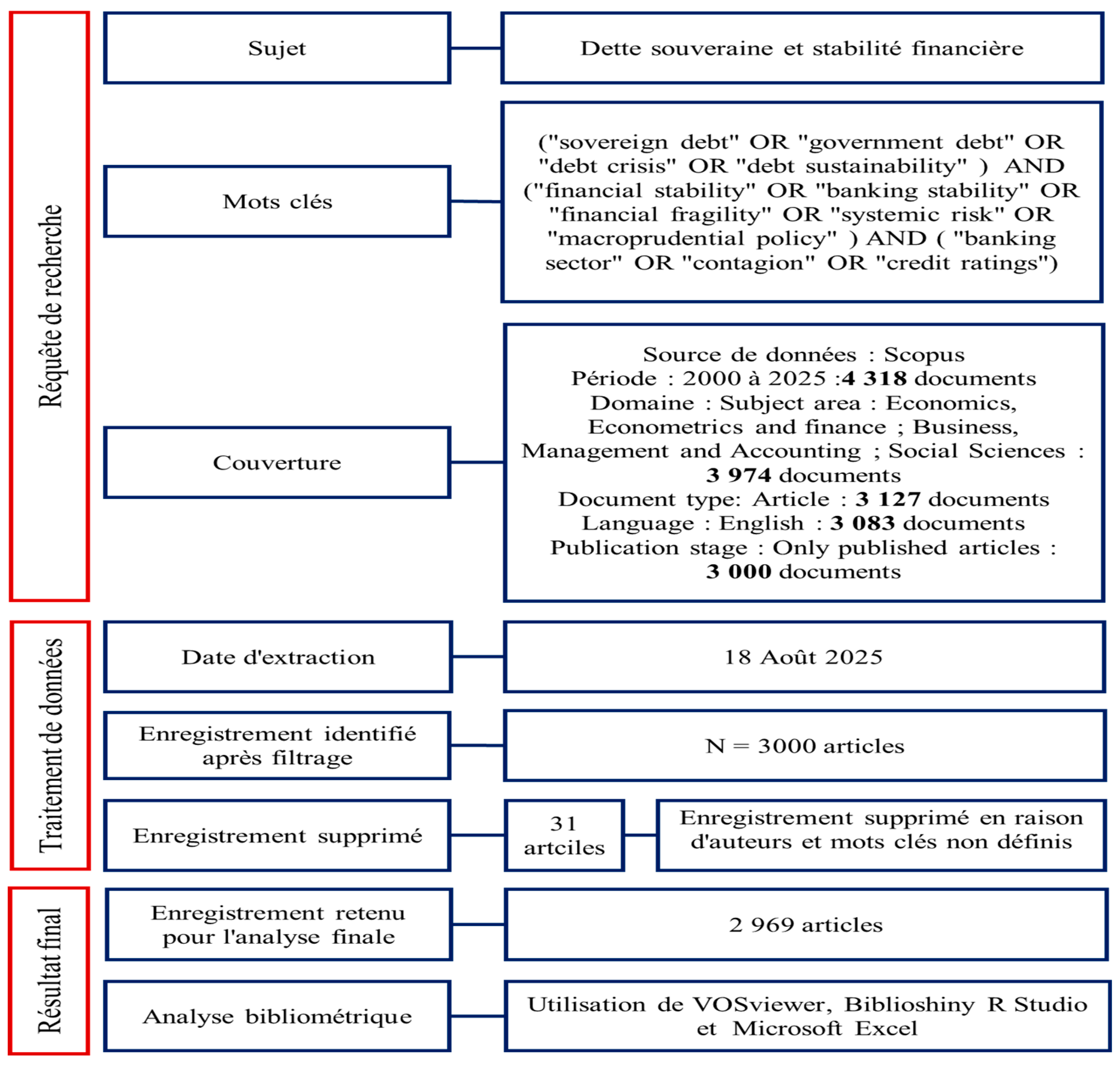

To examine trends in research on the relationship between sovereign debt and financial stability, the rigorous collection method used is illustrated in

Figure 1 below. In order to guarantee the quality of the results, data extraction was performed on Scopus Elsevier using a Boolean query including keywords referring to sovereign debt, financial stability and the financial sector, in addition to filters, and formulated as follows: (“sovereign debt” OR “ government debt” OR “debt crisis” OR “debt sustainability”) AND (“financial stability” OR “banking stability” OR “financial fragility” OR “systemic risk” OR “macroprudential policy”) AND (“banking sector” OR “contagion” OR “credit ratings”) AND PUBYEAR>1999 AND PUBYEAR<2026 AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “ECON”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “BUSI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “SOCI”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE,”final”)). This search query is based on De Bandt and Hartmann’s (2002) definition of systemic risk and initially generated 3,000 published articles. It includes articles published in English only between 2000 and 2025. The processing allowed for the removal of 31 articles using RStudio and Excel tools due to their ineligibility due to missing authors, keywords and/or abstracts. Data extraction was carried out on 18 August 2025. This rigorous selection process and subsequent harmonization resulted in a final total of 2,969 articles being retained for this bibliometric study.

2.2. Methodology

The methodological approach used in this study is a three-step bibliometric analysis. The first step is a statistical analysis of total output and citations. The second step focuses on analyzing the performance of authors, sources, regions and articles. The last step proposes a mapping of keywords and keyword trends.

3. Descriptive Analysis

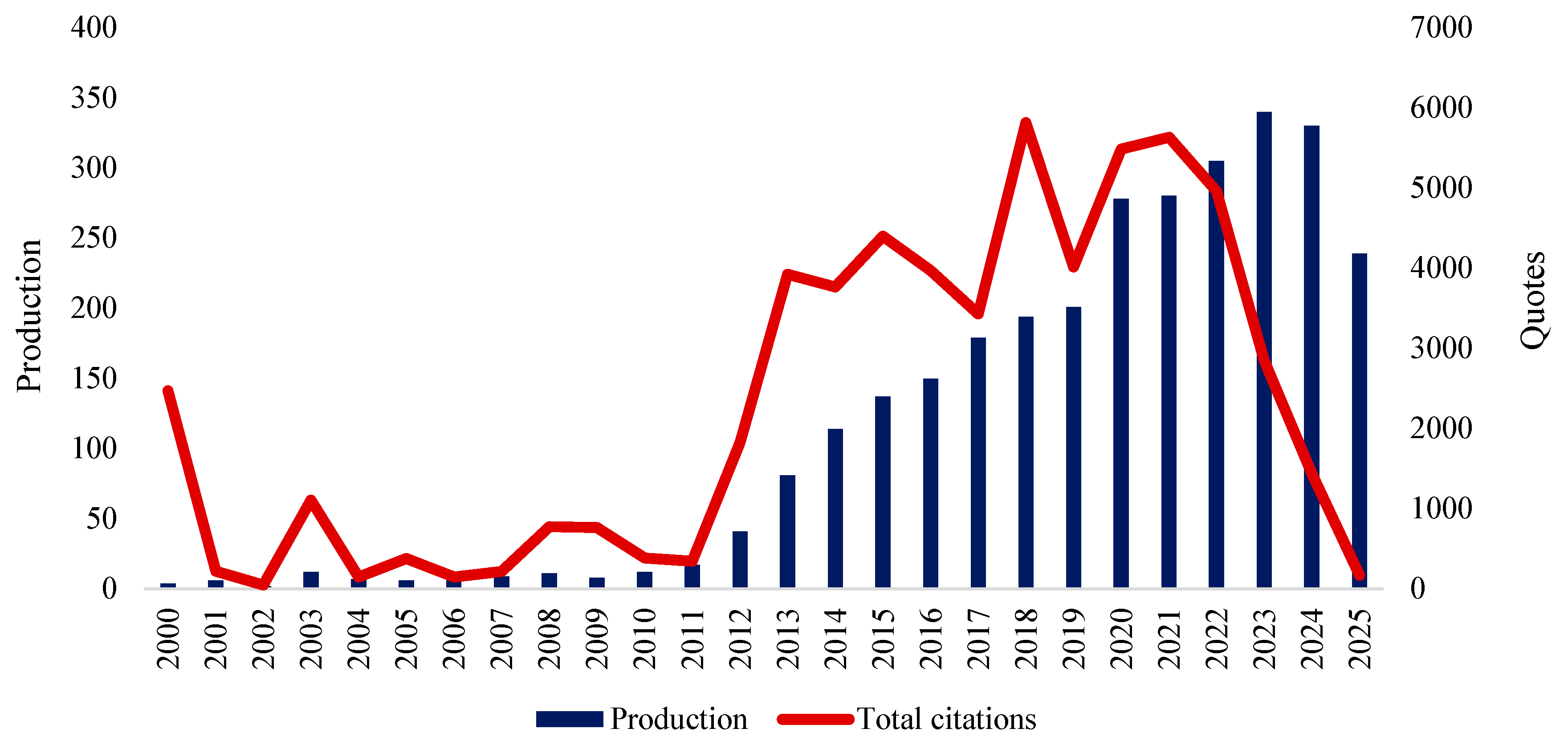

Figure 2 reveals an explosion in scientific productivity and total citations in this field since the early 2010s. While annual output was marginal, with fewer than 20 articles per year until 2011, it has grown rapidly since 2012-2013, which is no coincidence. It is directly correlated with the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. The subject was previously relatively niche, but events in Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain (2009-2012) brutally exposed the links between state solvency and the health of banking systems. During this period, sovereign debt thus evolved from a theoretical concept to a central and urgent issue of global financial stability.

The peaks in citations observed between 2018 and 2022 mark the phase of maturation and synthesis of knowledge. The seminal articles published during the growth phase (2013-2017) have been widely cited, validating their importance in financial economics. The high number of citations shows that the subject has moved from being a circumstantial concern to a central and enduring theme, essential for understanding the vulnerabilities of the global financial system, well beyond the European context. The number of publications then exploded, peaking in 2023 due to the Russian-Ukrainian crisis and its consequences on the financial and commodity markets.

The vigorous output for 2024-2025, despite still low citations due to its youth, proves the responsiveness and continued vitality of the field. Recent research no longer focuses solely on the 2012 crisis, but has adapted to analyze the impact of new shocks, such as the Covid-19 pandemic (which led to an explosion in public debt) and geopolitical tensions, on this same link between sovereign debt and financial stability.

4. Performance Analysis

4.1. Influential Journals: Analysis of Output

Based on a minimum threshold of publications (NP ≥ 50),

Table 1 below provides an assessment of the most influential journals in the field of financial economics. The hierarchy, mainly determined by the h-index, reveals a competitive landscape. The Journal of Financial Stability (h-index: 32), the International Review of Financial Analysis (h-index: 28) and the Journal of International Money and Finance (h-index: 30) stand out as pillars with 104, 91 and 90 publications, respectively. Furthermore, the h-index, reflecting a composite measure of the impact and productivity of journals, shows that the Journal of Banking and Finance, despite its 81 publications, is particularly noteworthy; although ranked fourth, it dominates the corpus by its gross cumulative impact, with a total number of citations (TC: 4,209) far exceeding that of its direct competitors and a g-index of 64, the highest in the ranking. This significant gap between its h-index (35) and g-index (64) indicates the presence of a substantial number of highly cited “flagship” articles, which contribute disproportionately to its overall influence. These four journals are the oldest with the largest number of publications.

The m-index measures publication growth and reveals uneven growth dynamics. Newer journals, such as the North American Journal of Economics and Finance (PY_start: 2014; m-index: 1.67) and Finance Research Letters (PY_start: 2014; m-index: 1.50), have annual impact rates that surpass those of many established journals, such as the International Review of Financial Analysis (PY_start: 2003; m-index: 1.22) or the Journal of International Money and Finance (PY_start: 2003; m-index: 1.30). This positions these emerging journals at the forefront of cutting-edge research, demonstrating remarkable scientific vitality. In contrast, the metrics of the International Journal of Finance and Economics (h-index: 15; TC: 600; m-index: 0.69), which began publication in 2004, indicate a comparatively slower accumulation of influence, despite being older than the most dynamic titles.

4.2. Influential Journals: Citation Analysis

Table 2 summarizes the most influential journals with at least 1,000 citations. Although dominated by the Journal of Banking and Finance with an impressive total number of citations (TC) of 4,209, it masks a more nuanced reality. This score is largely explained by a very high publication volume (NP: 81), a feature shared by other leaders such as the Journal of Financial Stability (TC: 3,159, NP: 104) and the Journal of International Money and Finance (TC: 2,777, NP: 90). Their leading position reflects their cumulative gross influence and longevity, as evidenced by their early start (2002-2003). However, the aberrant presence of the Journal of Political Economy in 5th position (CT: 2123) serves as a warning against reading CT too literally. Its score is entirely driven by a single hyper-cited article (NP: 1), which translates into an h-index of 1 and a minimal m-index of 0.04, revealing that this is a statistical artefact and not a measure of the journal’s consistent influence.

Beyond raw volume, the vitality and immediate influence of a journal can be measured by its m-index. This indicator, which normalizes the h-index by the number of years of activity, reveals that newer, more agile journals significantly outperform historical heavyweights in terms of impact per article and per year. The most striking example is Energy Economics (TC: 1641), which, despite only starting in 2017, has the highest m-index in the table (2.11), indicating phenomenal annual influence. It is closely followed by Economic Modelling (m-index: 1.64) and the North American Journal of Economics and Finance (m-index: 1.67), both launched in 2012 and 2014, respectively. Their high m-index scores, contrasting with more modest TCs, signal that they are at the forefront of current research trends and are prime platforms for the most influential work of the moment.

4.3. Influential Authors’: Analysis of Output

Among the most prolific authors, with at least 12 publications, the field is dominated by a cohort of researchers who began publishing in 2012, a sign of remarkable early productivity (

Table 3). Names such as Mensi W. (18 publications), a researcher affiliated with the Faculty of Economics and Political Science at Sultan Qaboos University, and Vo X.V. and Umar Z. (15 publications each), affiliated with the Institute of Commercial Research and CFVG, Ho Chi Minh City University of Economics, Vietnam, rank first and second, respectively, for their high output volume over a relatively short period. However, the number of publications (NP) tells only part of the story. A comparison of total citations (TC) reveals significant differences: Umar Z. (TC: 603) affiliated with the College of Commerce at Zayed University Abu Dhabi (United Arab Emirates) and Corbet S. (TC: 703 for 13 publications) associated with the University of Dublin in Ireland have produced work that has been cited much more widely than researchers such as Wang X. (TC: 146 for 14 publications) from the School of Finance at Shanxi University of Finance and Economics in Taiyuan or Foglia M. (CT: 180 for 12 publications) from Gabriele d’Annuanzio University in Chieti and Pescara (Italy), whose citation impact remains, for the moment, more modest in relation to their publication rate.

The most revealing metric is undoubtedly the m-index, which measures annual impact. It identifies the real rising stars who combine productivity with immediate influence. Vo X.V., with an m-index of 2.00 for a start in 2020, stands out clearly, displaying the most explosive influence rate in the ranking. He is closely followed by Umar Z. (m-index: 1.57 since 2019) and Foglia M. (m-index: 1.00 since 2019). Conversely, highly prolific authors such as Sosvilla-Rivero S. (m-index: 0.69 since 2013) and Ap Gwilym O. (m-index: 0.57 since 2012) have seen their impact decline over a longer period. This ranking thus reveals two profiles: recent researchers with meteoric trajectories and others with consistent productivity but more moderate annual influence.

4.4. Influential Authors’: Citation Analysis

The most cited authors (at least 600 citations) reveal an academic landscape divided between a handful of extremely influential articles and contemporary researchers combining volume and impact (

Table 4). The top of the ranking is dominated by renowned theoretical economists such as Allen F. (TC: 2,270) and Gale D. (TC: 2,166), whose position can be explained by a very small number of articles (NP: 4 and 2) published in 2000. Their presence at the top, despite very low h and m indices, indicates that their work, although limited in number, is fundamental and has been widely cited for more than two decades. This phenomenon is repeated with Acharya V.V. (TC: 615, NP: 5), whose articles are pillars in their field. At the other extreme, authors such as Antonakakis N. (CT: 940) and Metaxas V.L. (CT: 625) appear only because of a single, exceptionally cited article (NP: 1), which severely limits their h-index. The second part of the ranking illustrates a different kind of influence, based on regular and recent output. Corbet S. (TC: 703, NP: 13) and Umar Z. (TC: 603, NP: 15) stand out clearly. Their high number of publications and robust h-indexes (11 each) demonstrate that they have produced a continuous stream of influential work. Their high m-indexes (1.22 and 1.57) confirm that they are among the most active and immediately influential contemporary researchers.

4.5. Most Cited Articles

The final part of the performance analysis focuses on the most cited articles (at least 250 citations). The results in

Table 5 reveal the dominance of seminal articles that laid the foundations for entire fields of research. Allen and Gale’s (2000) study, “Financial Contagion”, is far ahead with 2,123 citations. This theoretical work, along with that of Bekaert and Harvey (2003) (417 citations) on emerging markets and Pan and Singleton (2008) on sovereign CDSs (423 citations), illustrates the lasting impact of pioneering conceptual frameworks. Their influence persists after more than fifteen years, confirming their status as essential references. The presence of these highly cited older articles (2000, 2003 and 2008) serves as a reminder that modern crises are based on pre-existing theoretical frameworks

A strong trend is the predominance of studies measuring systemic risks and financial interconnections. The article by Antonakakis et al. (2020) on dynamic connectedness via TVP-VAR models (940 citations), and that by Demirer et al. (2018) on global banking networks, testify to the importance of this field (414 citations). The recent paper by Ando et al. (2022) on quantile connectedness confirms the vitality of this methodological approach, which is crucial for understanding the propagation of financial shocks (484 citations).

Other pioneering articles cited focus on the analysis of specific crises and regional vulnerabilities. Indeed, the study by Louzis et al. (2012) on non-performing loans in Greece has become a reference for the European crisis (625 citations). Similarly, the work of Acharya and Steffen (2015) on the risks of eurozone banks, with 319 citations, and Frankel and Saravelos (2012) on crisis indicators, respond to an urgent need to understand economic vulnerabilities (276 citations). Debates on public policy and banking regulation have a significant academic impact. Articles by Greenwood et al. (2015) on vulnerable banks (287 citations), Duchin and Sosyura (2014) on the effect of government aid (264 citations), and Acharya et al. (2019) on unconventional monetary policy (255 citations) show how research directly informs the design of financial stability policies.

The presence of very recent articles (2020-2022) in the top 20, such as those by Balcilar et al. (2021) on commodity markets (298 citations), Okorie and Lin (2021) on Covid-19 (259 citations), and Ando et al. (2022), highlights the responsiveness of research to current events related to the health crisis and the Russian-Ukrainian war, as well as the emergence of new innovative approaches.

5. Scientific Mapping: Structure and Dominance of Major Collaborative Hubs

The second stage of mapping uses fractional counting. This technique allows the contribution of each publication to be weighted while ensuring methodological robustness. As a result, this mapping does not simply list popular terms; it accurately models the conceptual architecture of the research field. It serves as an analytical basis for discussing dominant trends, specialized niches and the density of thematic collaborations.

5.1. Analysis of the Collaboration Network

5.1.1. Country Network

The results identified 61 countries divided into eight distinct clusters. They reveal an asymmetrical collaborative architecture dominated by a few large networks (

Figure 3). Cluster 1 (in red), with 16 countries, emerges as the most important collaborative hub, forming the core of the network. Its size suggests a vast multinational alliance structured around several major research powers, including France, Greece and India. Cluster 2 (in green), comprising 12 countries, is led by the USA, the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany and Turkey. Cluster 3 (in blue), comprising 10 countries, including Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Ukraine, indicates that international collaboration is polarized around several major hubs rather than being completely centralized. This structure shows that knowledge production is the result of a few large strategic coalitions.

Clusters 4, 5 and 6, led by Australia, China and Chile with 8, 6 and 6 countries respectively, represent medium-sized networks. Although less extensive, these groups are crucial to the diversity and resilience of the global collaborative landscape. They often reflect specific regional or thematic alliances. For example, cluster 5 brings together emerging economies from the same region or countries united around a common research program (China, Hong Kong, Taiwan). Their existence demonstrates that substantial collaborations exist outside the largest hubs, allowing for some diversification of research profiles and perspectives.

At the other end of the spectrum, clusters 7 and 8, with only two (Colombia and Spain) and one country (Canada) respectively, are particularly revealing and constitute specialized niches or emerging collaborations. Cluster 7 (two countries) represents a pair of nations with extremely strong and exclusive collaboration due to historical ties. Cluster 8, reduced to a single country, is the most intriguing. This indicates that Canada operates in complete isolation in this field of research, with no significant international collaboration meeting the minimum threshold of 10 documents. This could be entirely domestic scientific production, or production whose main partners are not among the countries that have reached the threshold for inclusion in the analysis.

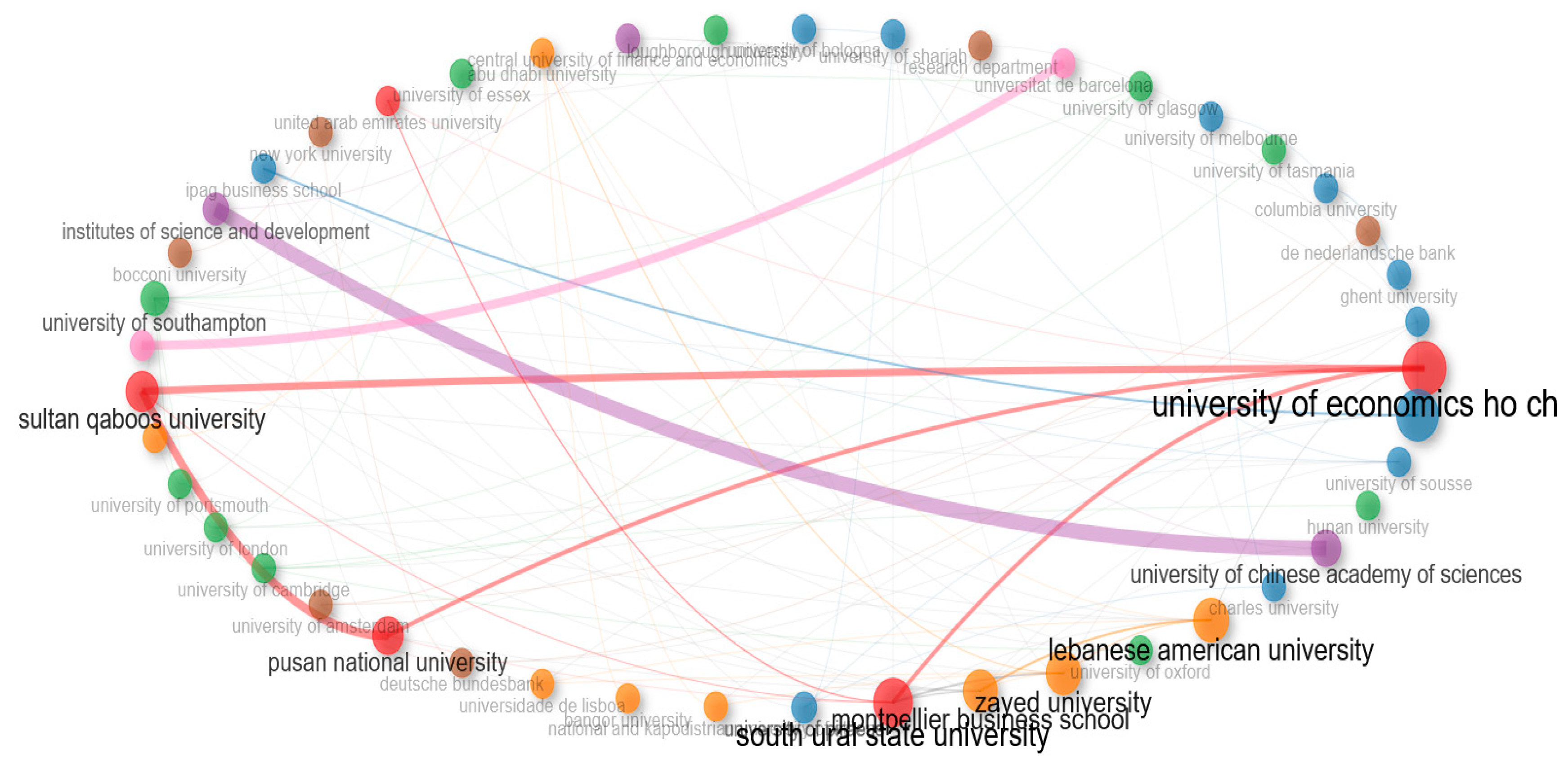

5.1.2. Institutional Collaboration Network

The results of the analysis of the global institutional collaboration network are structured around a few major hubs. Institutions such as the University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, Sultan Qaboos University and the University of Sharjah form cluster 1 and stand out as the most central and influential. The London School of Economics (LSE) stands out as the most central and influential institution in the entire network. Cluster 2 is mainly driven by the Athens University of Economics and Business, the London School of Economics, the University of Cambridge, the University of London and the University of Southampton, reinforcing the UK’s dominance as the center of this network. Strikingly, institutions from less dominant countries such as Zayed University, Montpellier Business School and Deutsche Bundesbank are also emerging as crucial nodes, demonstrating the diverse and decentralized nature of modern research. The presence of the Deutsche Bundesbank alongside academic institutions shows that the theme of the link between sovereign debt and financial stability lies at the intersection of finance and monetary policy.

Figure 4.

Institutional collaboration network. Source: authors’, based on Biblioshiny.

Figure 4.

Institutional collaboration network. Source: authors’, based on Biblioshiny.

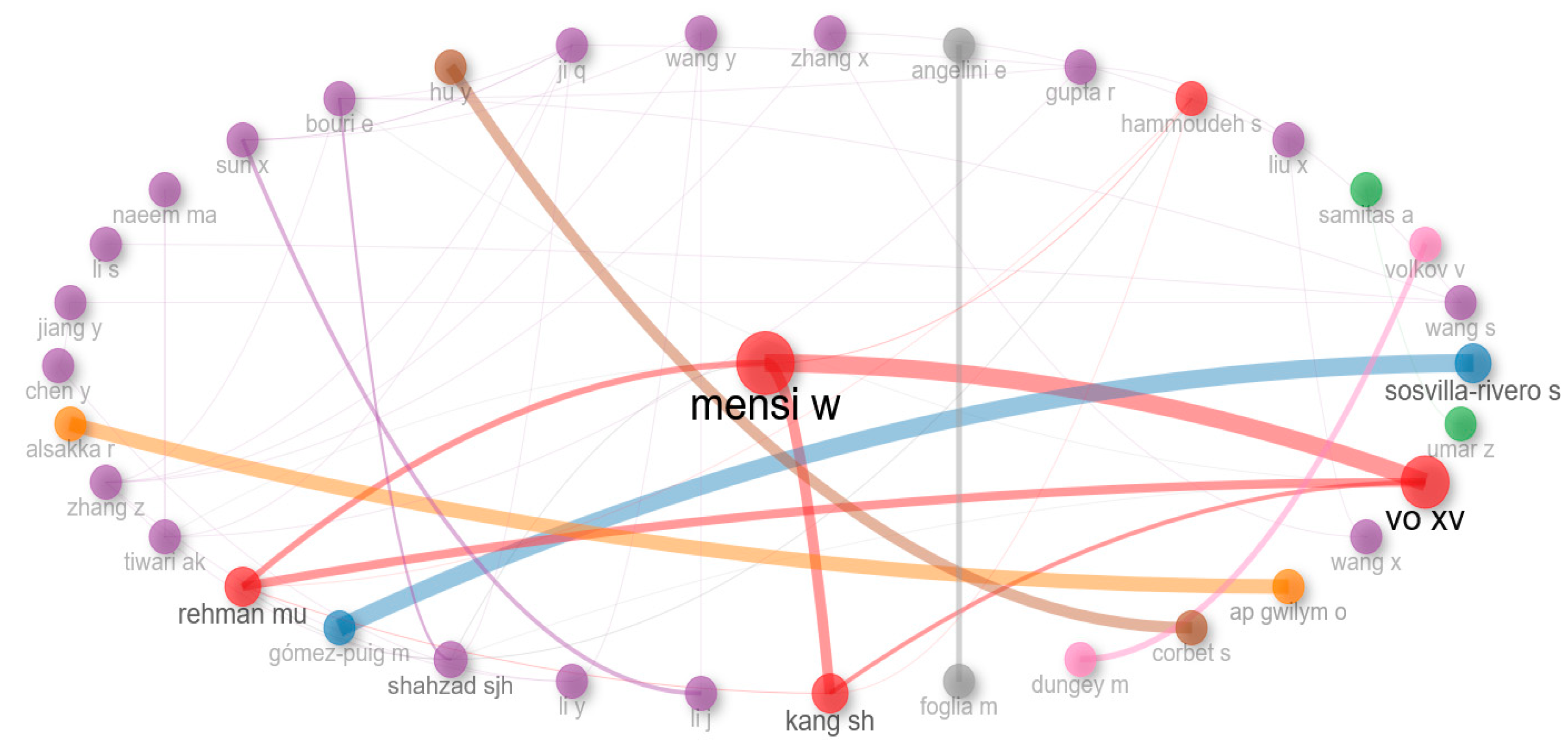

5.1.3. Author Collaboration Network

This analysis of the co-author network reveals a complex and hierarchical collaborative structure. Cluster 1 (in red) clearly emerges as the active core of the network, bringing together the most influential and strategic authors. It is composed of authors such as Mensi W, Vo VX, Kang SH, Rehman MU and Hammoudeh S, indicating that they are essential bridges connecting different groups and effectively disseminating information throughout the network. Similarly, cluster 10 (in purple), comprising authors Zhang Z, Shahzad SJH, Tawari AK, Chen Y, Gupta R, Wang S, Bouri E, and Ji Q, highlights their crucial role as bridges between different subgroups and their control over the flow of information. The other clusters indicate isolated pairs of authors who are less connected to the network.

Figure 5.

Author collaboration network. Source: authors’, based on Biblioshiny.

Figure 5.

Author collaboration network. Source: authors’, based on Biblioshiny.

5.1.4. Regions of Co-Authors’

The results of mapping the countries of corresponding authors with at least 50 articles show a landscape dominated by China, which emerged as the undisputed leader in production with 359 articles (

Figure 6 and

Table 6). It masters both aspects of modern research with a strong domestic base (SCP: 234) and strategic international integration (MCP: 125). This contrasting approach places China in a category of its own, both autonomous and globally connected. In contrast, the United States (165 articles) is a unique case with an ultra-domestic model. Their extremely low rate of international collaboration (MCP: 6) suggests a research ecosystem so vast and competitive that it can largely operate in a closed circuit, or that its most strategic collaborations are not captured in this specific database.

Europe stands out as the driving force behind collaborative science. Indeed, nations such as France (MCP %: 58.64%), Germany (MCP %: 45.76%) and Italy (MCP %: 39.18%) combine high production volumes with a very strong propensity to collaborate beyond their borders. Belgium has the highest internationalization rate of all (MCP %: 66.67%). Although its output is modest in volume (51 articles), it is mainly the result of international partnerships (MCP: 34), making it a crucial hub in global research networks. The United Kingdom and Spain present a more balanced model, favoring national collaborations (high SCP) while maintaining significant international openness (MCP % of 15.53% and 16.13%).

Australia (139 articles) and Greece (107 articles) illustrate how geographically isolated countries use international collaboration as a strategic lever. Australia has the highest MCP % of the top 12 (61.87%), showing that its global integration is vital to maintaining its visibility and competitiveness. Greece, meanwhile, also makes extensive use of international collaborations (MCP %: 39.25%) to amplify the impact of its scientific output. Finally, countries such as India (69 articles) and Turkey (61 articles) seem to be entering a phase of development where consolidating their domestic research ecosystem is a priority, as evidenced by their SCP scores, which are well above their MCP scores. Their internationalization, although real, is still a work in progress.

5.1.5. Classification of Countries by Annual Total Output and Citations

The scientific output ranking places China (803 publications) and the United States (681 publications) ahead of other nations (

Table 7). The United Kingdom (618 publications) completes the podium, but with a significantly lower volume. The landscape is then marked by a strong European presence, with Italy (405), Germany (380), France (312), Spain (260) and Greece (231) occupying the following places, demonstrating the collective vitality of European research. Australia (201) and Portugal (160) are also important hubs, while the presence of India (152) and Turkey (142) reveals the active emergence of new major contributors to global scientific output. At the African level, only Tunisia (118) appears in the ranking.

In terms of citations, China, with 6,223 citations, still dominates the scientific impact ranking, confirming that its massive volume of publications translates into significant global influence, while the United States (5,450 citations) remains a strong competitor, demonstrating particularly high average impact per publication. At the European level, Germany (3,819 citations), France (3,464 citations) and Italy (2,640 citations) dominate the rankings. This illustrates the exceptional quality of their scientific output, with an influence disproportionate to its volume. The presence of countries such as Austria (1,786 citations) and Ireland (1,230 citations), which outperform nations that are more productive in terms of volume, highlights that the impact of research depends less on raw quantity than on integration into international networks of excellence and the production of seminal work.

5.2. Thematic Trends

5.2.1. Analysis Authors’ Keyword Network

This visualization reveals the fundamental structure of the research field by mapping the frequent associations between keywords chosen by authors (

Figure 7). The presence of several distinct clusters, each with a specific color, indicates the existence of well-identified thematic sub-communities within the literature. The size of the nodes (keywords) is proportional to their frequency of use, while the thickness of the links between them reflects the intensity of their co-occurrence in the same publications. We can thus distinguish a landscape in which certain central themes (red cluster 1 with 13 items), such as “credit rating agencies”, “emerging market”, “global financial crisis,” “sovereign debt,” “credit default swaps,” “financial markets,” “financial regulation,” and “sovereign credit rating,” form the core of the research, centered on the role of sovereign debt and sovereign ratings in financial crises via the markets.

A major cluster, the true heart of the research (cluster 2 in green on the map), is structured mainly around the concepts of sovereign risk, health crises and uncertainties that are likely to spread via connectivity and contagion dynamics. Terms such as “connectedness”, “financial crisis”, “Covid-19”, “financial contagion”, “economic policy uncertainty” and “stock markets” are found here. The density of the links between these keywords shows that they are frequently discussed together, forming a coherent and intensively studied core. This cluster reflects the discipline’s ongoing concern with the mechanisms of financial and health shock propagation, interdependent failures and vulnerabilities in the global financial system in response to crises and the eurozone. Cluster 3 revolves around concepts related to macroeconomic policies, the most important of which are “monetary policy”, “macroprudential policy”, “financial stability”, “public debt”, “financial crises”, “fiscal policy” and “euro area”. These keywords, located at the intersection of several clusters, act as cross-cutting concepts. For example, the terms “monetary policy” and “fiscal policy” are connected to the cluster on crises as a response tool, to the cluster on emerging markets as a vulnerability factor, and to the methodological cluster as a study variable.

Cluster 5 forms a more distinct subdomain and focuses on the methodological aspects most commonly used to quantify systemic risk. These are the terms ‘CoVaR’, ‘Copula’ and ‘Systemic risk’. Finally, Clusters 6 and 7 feature terms such as “Covid-19 pandemic,” “sovereign bonds,” “CDS,” “quantile regression,” “network analysis,” “sovereign credit risk,” “contagion,” and “banking crises.”

Figure 8 adds a crucial dynamic dimension to the mapping. The overlay reveals the evolution of concepts over time. Traditionally, yellow colors indicate recent themes (2022-2025), while blue and green colors represent older concepts (before 2018). This visualization thus makes it possible to trace not only the dynamic structure of the trajectory over the last decade. These results show a very strong persistence of concepts related to historical financial crises and systemic risk. Terms such as “sovereign debt”, “sovereign debt crisis”, “emerging markets”, “eurozone”, “financial crisis” and “contagion” confirm their role as stable and enduring foundations of the literature. The presence of “eurozone” indicates that most of the work focuses on this area.

Conversely, keywords such as “Covid-19 pandemic”, “connectedness”, “Covid-19” and “economic policy uncertainty” are emerging and forming nodes that capture the most recent concerns relating to the health and geopolitical crises. The central position of some of these terms shows that they are not marginal but are reshaping the current debate around them.

5.2.2. Analysis of the Authors’ Keyword Index Network

Unlike

Figure 8, which used the authors’ keywords, this figure (

Figure 9) is based on the keyword index with an occurrence of 20, assigned by the databases to standardize and structure the content. This provides a more objective, standardized and detailed view of the intellectual architecture of the field. The themes are less likely to be influenced by authors’ trends or jargon, and better reflect established disciplinary foundations. The presence of well-defined and dense clusters indicates that research in this field is highly structured around several coherent and recognised thematic cores.

Figure 9 reveals major themes and their interconnections. A cluster typically emerges around the theme of the international environment, bringing together “risk assessment”, “financial markets”, “price dynamics”, “Covid-19”, “China”, “trade” and “United States”. This cluster (in red) reveals that researchers are particularly interested in the impact of health crises and the current trade war on financial markets and global price dynamics. A cluster on economic policy includes terms such as “debt”, “economic growth”, “exchange rate”, “financial system”, “fiscal policy”, “investment”, “interest rate” and “macroeconomics”. This cluster (in green) highlights a body of work on the driving role of the financial system in the conduct of economic policy. The last cluster (in blue) focuses more on “financial crisis”, “debt crisis”, “banking”, “monetary policy”, “credit provision”, “Europe” and “sovereignty”. The strong links between these terms show how intrinsically linked and mutually reinforcing these sub-domains are.

Figure 10 adds an essential layer of chronological analysis to the mapping in

Figure 8. The overlay reveals the evolution over time of the use of the normalized keyword index. This makes it possible to distinguish between the founding and persistent concepts and the emerging themes that are shaping the new frontiers of research. The view is more stable and standardized than that in

Figure 5, as it is based on a controlled vocabulary that is less subject to terminological variations among authors. The central clusters in

Figure 8, particularly those related to financial crises, financial markets (financial markets, systemic risk, contagion) and economic policies (monetary policy, fiscal policy), are likely to appear in cool colors (blue). This confirms their status as historical and enduring pillars of the discipline, whose centrality and relevance remain undiminished despite the changing context. Their stable position at the heart of the network indicates that they constitute the theoretical and empirical foundation on which new issues are built.

Conversely, specific terms related to recent shocks and new methodologies used appear in yellow. Concepts related to the Covid-19 pandemic, financial markets and their economic implications form a recent and highly connected node. The peripheral position of these terms shows how the discipline is gradually assimilating and integrating new objects and tools. The overlay makes it possible to identify the dynamics of renewal and research trajectories. Analysis of this network shows that older concepts (blue) such as “debt crisis” and “financial crisis” are connected to recent concepts (yellow) such as “Covid-19” and “financial markets”, illustrating how a stable issue is updated by a new context and shaping the current boundaries.

5.2.3. Analysis of the Keyword Cloud of Title

Figure 11 provides the results of the keyword cloud. It is dominated by terms such as “systemic risk” (172 occurrences), “sovereign debt” (128) and “financial crisis” (103), and reveals a marked focus of research on financial contagion mechanisms and state vulnerabilities. The strong presence of concepts such as sovereign risk, sovereign credit and sovereign bonds indicates that the literature analyses in depth the links between state fragility and financial system stability, particularly in the post-crisis context of the eurozone. The terms “financial stability”, “banking sector” and “risk contagion” highlight that the research specifically studies the channels through which shocks spread, while the recurrence of “non-performing loans” and “credit risk” points to persistent challenges in the banking sector. The mention of “Covid-19 pandemic” (42) and “emerging markets” (41) shows that research continues to adapt to new crisis contexts and the specificities of emerging economies, making this cloud a reflection of the most current concerns in financial economics.

5.2.4. Dynamics of Keywords in Title

Figure 12, “Trend Topics,” reveals the evolution of research topics in finance and economics over the last fifteen years, highlighting several strong trends. The persistence of topics related to sovereign risk (“sovereign credit risk”, “sovereign debt crisis”, “sovereign credit ratings”) and financial crises (“global financial crisis”, “European debt crisis”) shows a continuing interest in the vulnerabilities of states and their systemic implications, particularly in the context of the eurozone (“European monetary union”). The emergence of terms such as ‘machine learning approach’ and ‘panel data analysis’ highlights the growing adoption of advanced quantitative methods to model market complexity. Furthermore, the rise of the concepts of “extreme risk spillovers” and “systemic risk contagion” from 2018-2019 onwards, amplified by the Covid-19 period, reflects a growing concern about the interconnectedness of risks and the spread of shocks on a global scale. Finally, the recurring presence of “economic policy uncertainty” and “global stock markets” confirms that research is focused on understanding the impact of economic policies and geopolitical uncertainties on financial stability.

5.2.5. Dynamics of Author Keywords

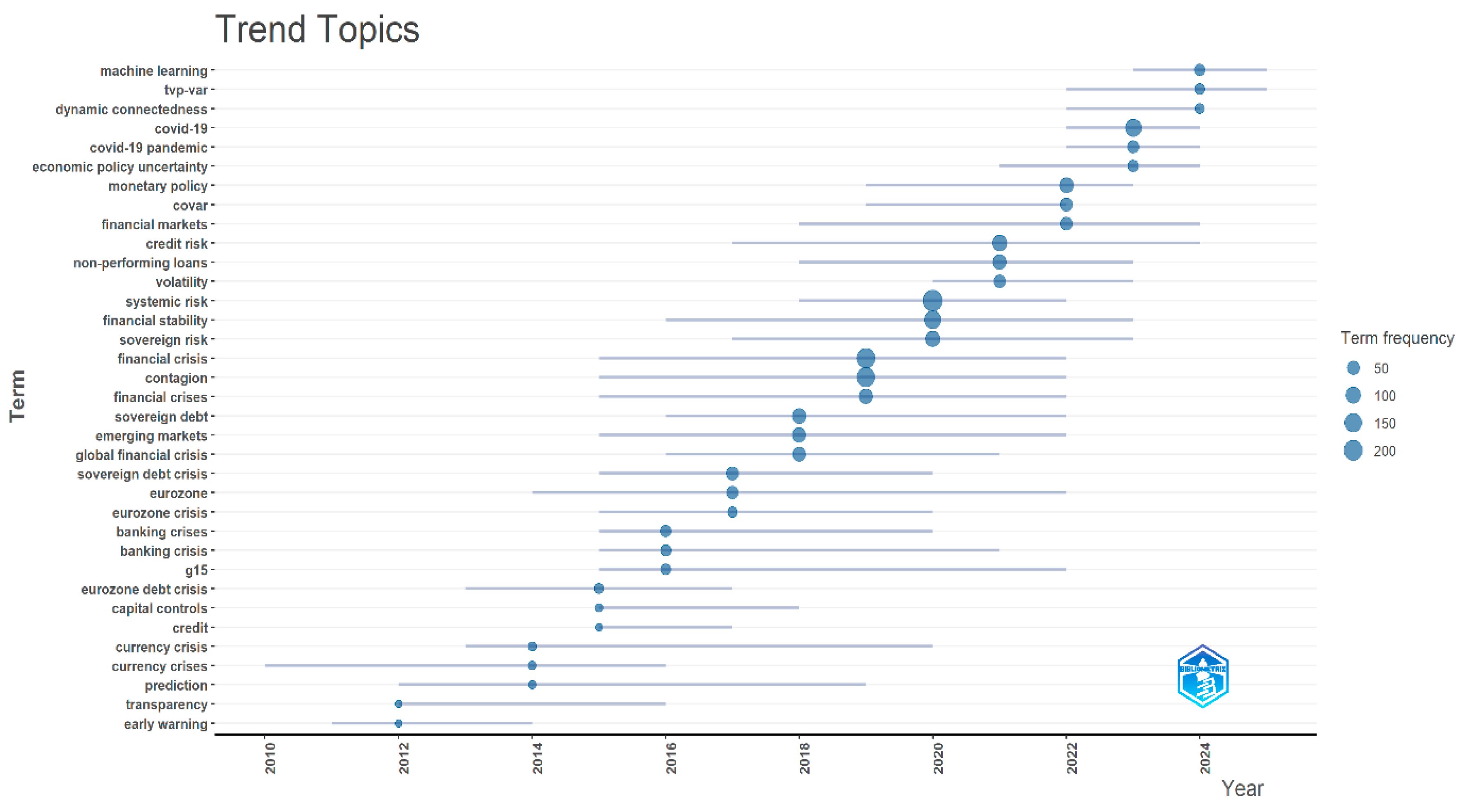

Author keywords strikingly illustrate the evolution of research concerns in finance over the last fifteen years (

Figure 13). There has been a clear transition from historical crises to modern analytical tools and new global shocks. The period 2010-2016 was dominated by the study of structural crises, with peaks for “sovereign debt crisis”, “eurozone crisis”, “global financial crisis” and “banking crisis”. These terms reflect research efforts to understand the mechanisms of the major crises of 2008-2012. From 2017-2019 onwards, new concepts emerged, signaling a methodological shift: “machine learning”, “dynamic connectedness” and “CoVar” show the growing adoption of advanced quantitative methods to model the complexity of financial systems.

The shocks of 2020 and 2022 are clearly visible with the sudden and massive explosion of “Covid-19” and “Covid-19 pandemic”, which became the focus of research and was linked to “economic policy uncertainty”. This period shows how the discipline reacts immediately to new global shocks. Finally, the most recent period (2023-2025) sees the persistence of “machine learning”, “tvp-var” and “dynamic connectedness”, indicating that these tools are now indispensable. The resurgence of themes such as “sovereign risk” and “non-performing loans” suggests that traditional vulnerabilities remain relevant in a new geopolitical and economic context.

5.2.6. Identification of Future Research

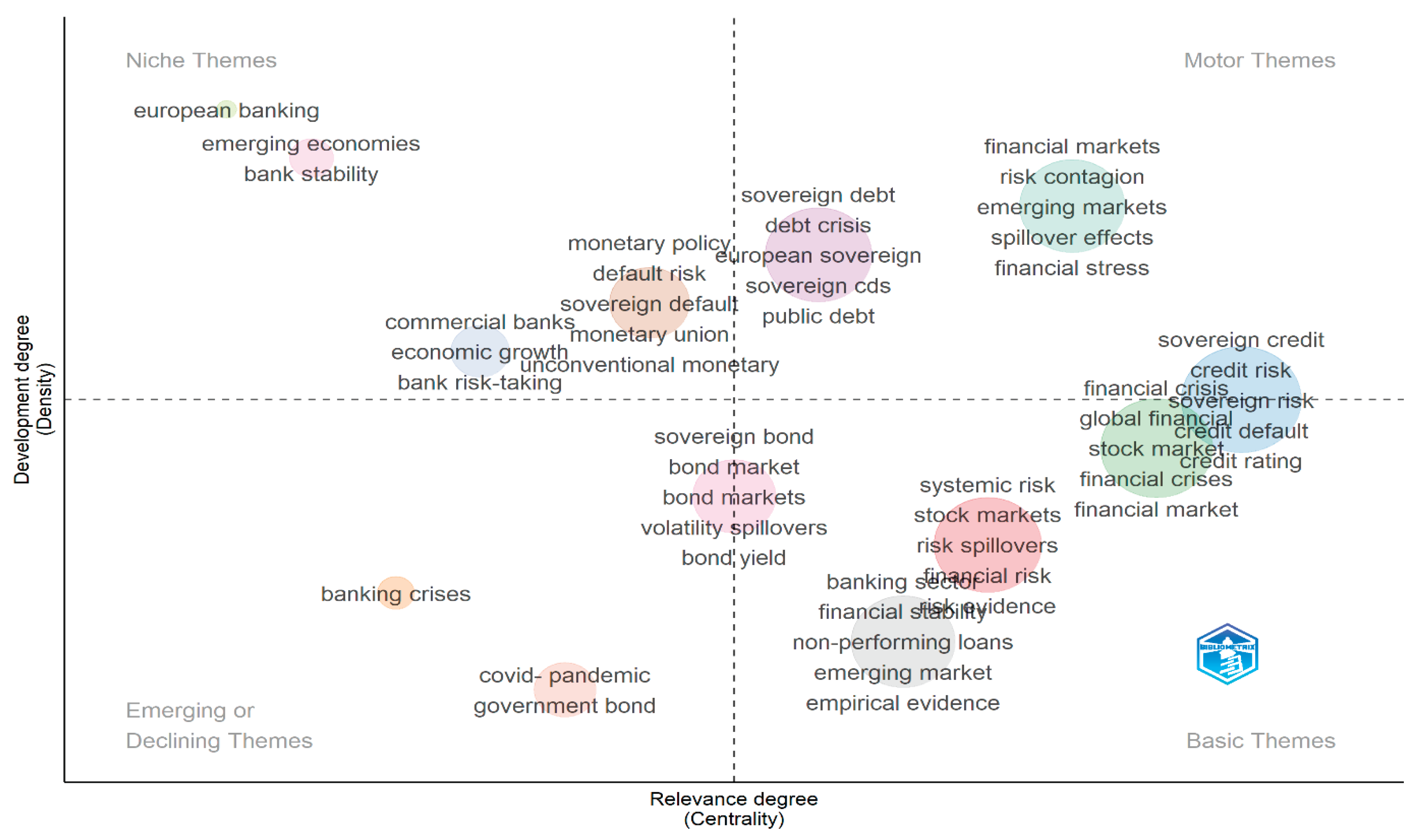

The results in Figure 14 reveal the intellectual structure of financial economics research. They classify themes into four categories based on their degree of development (density) and their centrality in the field of research (centrality). The basic themes (bottom right) relate to fundamental and cross-cutting concepts that serve as the foundation for the entire field. The high concentration of general terms such as ‘empirical evidence’, ‘financial market’, and ‘emerging market’ indicates that they are central to research (high centrality) but are so widely used that they do not define a specific niche (low density). They are also the tools and common language of the discipline. Terms such as “Covid-19 pandemic” and “banking crises” are also present, suggesting declining themes that are losing importance.

With high density and high centrality, the concepts “systemic risk”, “financial stability”, “sovereign debt”, “debt crisis”, “financial crisis”, “financial crises”, “credit risk”, “sovereign credit”, “non-performing loans”, “monetary policy”, “risk contagion” and “spillover effects” are the most developed central themes driving current research on the relationship between sovereign debt and financial stability. Finally, concepts with high density and low centrality, notably “European banking”, “bank stability” and “emerging economies”, form niche themes, showing that these are specialized, well-developed and internally structured areas, but that they are relatively peripheral to the most central debates in the field.

Overall,

Figure 15 shows that the core of the research is the study of the interconnections between sovereign debt crises and the stability of the banking and financial system. The most influential and structuring work focuses on understanding the risk of contagion, particularly between sovereign debt and the banking sector, and the implications for global financial stability.

6. Conclusions and Implications for Future Research

This bibliometric analysis deepens the field of research in financial economics, which is mature, dynamic and highly responsive to global crises. The results reveal a discipline structured around stable thematic cores, but constantly renewed by the emergence of new shocks and methodological innovations.

The analysis of journal and author performance highlights a competitive academic landscape. On the one hand, historical journals (such as the Journal of Banking and Finance) and authors (such as Allen and Gale, 2000), through their volume of output and longevity, provide a solid foundation and cumulative gross influence on topics related to financial crises and sovereign debt. On the other hand, more recent journals (such as Energy Economics and the Journal of Risk and Financial Management) and authors stand out for their rapid growth, with annual impact rates (m-index) higher than those of older journals and authors. This vitality is driven by recent researchers such as Umar and Vo, who combine productivity with immediate influence, often using cutting-edge quantitative methods.

Thematic mapping confirms the continuing centrality of studies of systemic risk, financial contagion and sovereign debt vulnerabilities as the core of the field. Thematic clusters such as “sovereign debt”, “financial contagion”, “banking sector” and “financial stability” form the fundamental and historical conceptual architecture of the field. This persistent focus can be explained by the aftermath of the 2008 crisis and the eurozone crisis, which have permanently shifted the research agenda towards understanding the mechanisms of shock propagation.

However, as research is constantly evolving, the discipline has demonstrated an exceptional ability to adapt by incorporating recent shocks, as evidenced by the explosion of research on Covid-19 and macroeconomic uncertainty, which have been added to existing analytical frameworks. Indeed, the Covid-19 crisis and the shocks of uncertainty linked to the Russian-Ukrainian war, geopolitical tension in the Middle East and the current trade war immediately emerged as a central and connecting theme, reconfiguring a significant part of the work around the analysis of the spread of health shocks, political uncertainty and market volatility. This ability to assimilate new global shocks demonstrates the vitality and contemporary relevance of the field.

The evolution of keywords shows a recent widespread adoption of advanced quantitative methods. The emergence and persistence of terms such as “machine learning”, “TVP-VAR”, “connectedness” and “quantile regression” signal a profound methodological transformation. These approaches, which have become indispensable, show that research has equipped itself with more powerful tools to model the complexity and non-linearity of global financial interconnections. At the same time, analysis of international collaborations reveals a globalized but asymmetrical scientific architecture. While China and the United States dominate in terms of production volume, European countries (France, Germany, Belgium) stand out for their highly collaborative model, which is essential for maintaining their excellence and influence.

Overall, the field of financial economics is driven by a dual dynamic, underpinned by a solid foundation in the study of past crises and financial stability and their fundamental mechanisms, and its ability to renew itself by integrating new exogenous shocks (pandemics, geopolitics) and methodological innovations. It remains an essential field for understanding and anticipating the vulnerabilities of an increasingly interconnected and complex global financial system in order to respond to the financial challenges of tomorrow.

By identifying trends in authors’ keywords, strengths and niches, research directions for the future can be formulated. First, the predominance of concepts such as ‘systemic risk’, ‘sovereign debt’ and ‘spillover effects’ calls for methodological refinement. The recent and influential work of Ando et al. (2022) on “quantile connectedness” highlights the need for future research to focus on analyzing the interdependencies between sovereign debt and banks, and to examine whether these interdependencies change radically in periods of extreme stress compared to periods of stability. Secondly, the absence of topics such as “shadow banking” or “non-bank financial intermediation” from the keyword cloud and trends represents a clear gap and therefore a major opportunity. Future research could focus on the role of these non-bank actors in amplifying or mitigating sovereign debt crises. Finally, the recent emergence of the term “economic policy uncertainty” demonstrates the responsiveness of research to new crisis contexts. Future research could quantify how geopolitical tensions (conflicts and international sanctions) are transmitted via increased uncertainty about economic policies, undermining debt sustainability and ultimately weakening the stability of the financial system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.N., Z.D.H. and B.S.; methodology, S.N.N., Z.D.H and B.S.; software, S.N.N and Z.D.H.; validation, S.N.N., Z.D.H and B.S.; formal analysis, S.N.N., Z.D.H. and A.S.; data curation, S.N.N and Z.D.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N.N., Z.D.H. and A.S, writing—review and editing, S.N.N., and AT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acharya, V.; Engle, R.; Richardson, M. Capital shortfall: A new approach to ranking and regulating systemic risks. American Economic Review 2012, 102(3), 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, V. V.; Steffen, S. The “greatest” carry trade ever? Understanding eurozone bank risks. Journal of Financial Economics 2015, 115(2), 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, V. V.; Eisert, T.; Eufinger, C.; Hirsch, C. Whatever it takes: The real effects of unconventional monetary policy. The Review of Financial Studies 2019, 32(9), 3366–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaminos, D.; Guillén-Pujadas, M.; Vizuete-Luciano, E.; Merigó, J. M. What is going on with studies on financial speculation? Evidence from a bibliometric analysis. International review of economics & finance 2024, 89, 429–445. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, F.; Gale, D. Financial contagion. Journal of Political Economy 2000, 108(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T.; Greenwood-Nimmo, M.; Shin, Y. Quantile connectedness: modelling tail behaviour in the topology of financial networks. Management Science 2022, 68(4), 2401–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, D. C.; Vlassopoulos, T. Home bias in bank sovereign bond purchases and the bank-sovereign nexus. In 57th issue (March 2019) of the International Journal of Central Banking; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakakis, N.; Chatziantoniou, I.; Gabauer, D. Refined measures of dynamic connectedness based on time-varying parameter vector autoregressions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2020, 13(4), 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athukorala, P. C. The sovereign debt crisis in Sri Lanka: Anatomy and policy options. Asian Economic Papers 2024, 23(2), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahoo, S. Corruption in banks: A bibliometric review and agenda. Finance Research Letters 2020, 35, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, V.; Kumar, P.; Singh, V. K. Linkage dynamics of sovereign credit risk and financial markets: A bibliometric analysis. Research in International Business and Finance 2022, 59, 101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcilar, M.; Gabauer, D.; Umar, Z. Crude Oil futures contracts and commodity markets: New evidence from a TVP-VAR extended joint connectedness approach. Resources Policy 2021, 73, 102219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballouk, H.; Jabeur, S. B.; Challita, S.; Chen, C. Financial stability: A scientometric analysis and research agenda. Research in International Business and Finance 2024, 70, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga-Pascual, L.; Loban, L.; Myllymäki, E. R. Bank credit risk and sovereign debt exposure: Moral hazard or hedging? Finance Research Letters 2025, 71, 106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basse, T.; Reddemann, S.; Riegler, J. J.; von der Schulenburg, J. M. G. Bank dividend policy and the global financial crisis: Empirical evidence from Europe. European Journal of Political Economy 2014, 34, S25–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekaert, G.; Harvey, C. R. Emerging markets finance. Journal of Empirical Finance 2003, 10(1-2), 3–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borensztein, M. E.; Jeanne, M. O.; Mauro, M. P.; Zettelmeyer, M. J.; Chamon, M. M. Sovereign debt structure for crisis prevention; International Monetary Fund, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boubaker, S.; Le, T. D.; Ngo, T. Managing bank performance under Covid-19: A novel inverse DEA efficiency approach. International Transactions in Operational Research 2023, 30(5), 2436–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capponi, A.; Cheng, W. S. A.; Giglio, S.; Haynes, R. The collateral rule: Evidence from the credit default swap market. Journal of Monetary Economics 2022, 126, 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carè, R.; Weber, O. How much finance is in climate finance? A bibliometric review, critiques, and future research directions. Research in International Business and Finance 2023, 64, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, M. S.; Kodres, M. L. E. The regulatory responses to the global financial crisis: Some uncomfortable questions; International Monetary Fund, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Bandt, O.; Hartmann, P. Systemic risk in banking: a survey. Financial Crisis, Contagion, and the Lender of Last Resort: A Reader; Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002; pp. 249–297. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Ariccia, G.; Igan, D.; Laeven, L. U. Credit booms and lending standards: Evidence from the subprime mortgage market. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 2012, 44(2-3), 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirer, M.; Diebold, F. X.; Liu, L.; Yilmaz, K. Estimating global bank network connectedness. Journal of Applied Econometrics 2018, 33(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Detragiache, E. The determinants of banking crises in developing and developed countries. Staff papers 1998, 45(1), 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; amp; Lim, W. M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchin, R.; Sosyura, D. Safer ratios, riskier portfolios: Banks’ response to government aid. Journal of Financial Economics 2014, 113(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichengreen, B.; Hausmann, R.; Panizza, U. The mystery of original sin. Other people’s money: Debt denomination and financial instability in emerging market economies, 233-65. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Perez, A.; Gómez-Puig, M.; Sosvilla-Rivero, S. Examining the transmission of credit and liquidity risks: A network analysis for EMU sovereign debt markets. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 2025, 77, 102407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyen, E.; Zuccardi Huertas, I. E. The Sovereign-bank Nexus in EMDEs: What is It, is it Rising, and what are the Policy Implications?. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (8950). 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fiordelisi, F.; Girardone, C.; Minnucci, F.; Ricci, O. On the nexus between sovereign risk and banking crises. Journal of Corporate Finance 2020, 65, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J.; Saravelos, G. Can leading indicators assess country vulnerability? Evidence from the 2008–09 global financial crisis. Journal of International Economics 2012, 87(2), 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratzscher, M.; Rieth, M. Monetary policy, bank bailouts and the sovereign-bank risk nexus in the euro area. Review of Finance 2019, 23(4), 745–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghulam, Y. Examination and predictions of risk tolerance levels and thresholds in sovereigns’ external debt defaults. International Economics and Economic Policy 2025, 22(2), 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Puig, M.; Sosvilla-Rivero, S. Causality and contagion in EMU sovereign debt markets. International Review of Economics & Finance 2014, 33, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Puig, M.; Singh, M. K.; Sosvilla-Rivero, S. The sovereign-bank nexus in peripheral euro area: Further evidence from contingent claims analysis. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 2019, 49, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Landier, A.; Thesmar, D. Vulnerable banks. Journal of Financial Economics 2015, 115(3), 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruppe, M.; Basse, T.; Friedrich, M.; Lange, C. Interest rate convergence, sovereign credit risk and the European debt crisis: a survey. The Journal of Risk Finance 2017, 18(4), 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, B.; Zhu, S. Covid, central banks and the bank-sovereign nexus. BIS Quarterly Review 2023, (27). [Google Scholar]

- James, H. The IMF and the European debt crisis; International Monetary Fund, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky, G. L.; Reinhart, C. M. Financial markets in times of stress. Journal of Development Economics 2002, 69(2), 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Goodell, J. W.; Hassan, M. K.; Paltrinieri, A. A bibliometric review of finance bibliometric papers. Finance Research Letters 2022, 47, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zinna, G. How much of bank credit risk is sovereign risk? Evidence from Europe. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 2018, 50(6), 1225–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C. H.; Costa, A.; Columba, F.; Kongsamut, P.; Otani, A.; Saiyid, M.; Wu, X. Macroprudential policy: what instruments and how to use them? Lessons from country experiences, 2011.

- Louzis, D. P.; Vouldis, A. T.; Metaxas, V. L. Macroeconomic and bank-specific determinants of non-performing loans in Greece: A comparative study of mortgage, business and consumer loan portfolios. Journal of Banking & Finance 2012, 36(4), 1012–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Marfo-Ahenkorah, D.; Asravor, R.; Asare, N. The Linkage between Banking Crisis and Sovereign Debt Crisis: Evidence from Ghana. Research in Globalisation 2025, 10, 10–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, P.; Vyas, V.; Kumar, U. Impact of regulations on the performance of banks—a bibliometric analysis. Transnational Corporations Review 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, A. Green and climate finance research trends: A bibliometric study of pre- and post-pandemic shifts. Cleaner Production Letters 2025, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, B. Lessons from the European economic and financial great crisis: A survey. European Journal of Political Economy 2014, 34, S9–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorie, D. I.; Lin, B. Stock markets and the Covid-19 fractal contagion effects. Finance Research Letters 2021, 38, 101640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacelli, V.; Di Tommaso, C.; Foglia, M.; Povia, M. M. Spillover effects between energy uncertainty and financial risk in the Eurozone banking sector. Energy Economics 2025, 141, 108082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Singleton, K. J. Default and recovery implicit in the term structure of sovereign CDS spreads. The Journal of Finance 2008, 63(5), 2345–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, C. M. Sovereign credit ratings before and after financial crises. In Ratings, Rating Agencies and the Global Financial System; Boston, MA: Springer US, 2002; pp. 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, R. The constraint on public debt when r; Bank for International Settlements, Monetary and Economic Department, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sibbertsen, P.; Wegener, C.; Basse, T. Testing for a break in the persistence in yield spreads of EMU government bonds. Journal of Banking & Finance 2014, 41, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.; Kimura, H.; Sobreiro, V. A. An analysis of the literature on systemic financial risk: A survey. Journal of Financial Stability 2017, 28, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, B. M.; Silva, T. C.; Fiche, M. E.; Braz, T. Citation likelihood analysis of the interbank financial networks literature: A machine learning and bibliometric approach. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2021, 562, 125363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, P. Corporate Credit Ratings, Banking Fragility, and Sovereign Credit Risk. Finance Research Letters 2025, 107611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Cui, H.; Hausken, K. The evolution of green finance research: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2025, 11(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabavnik, D.; Verbič, M. Relationship between the financial and the real economy: A bibliometric analysis. International review of economics & finance 2021, 75, 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric methods in management and organisation. Organisational research methods 2015, 18(3), 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Data selection and processing process. Source: authors’ design.

Figure 1.

Data selection and processing process. Source: authors’ design.

Figure 2.

Annual evolution of scientific output and total citations. Source: authors’ design, based on Scopus data.

Figure 2.

Annual evolution of scientific output and total citations. Source: authors’ design, based on Scopus data.

Figure 3.

Visualization of the co-author network at national level with a minimum of 10 documents from the country. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 3.

Visualization of the co-author network at national level with a minimum of 10 documents from the country. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 6.

Countries of corresponding authors. Source: authors’ results, from Biblioshiny.

Figure 6.

Countries of corresponding authors. Source: authors’ results, from Biblioshiny.

Figure 7.

Visualization of the co-occurrence network of authors’ keywords with a minimum occurrence of 25. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 7.

Visualization of the co-occurrence network of authors’ keywords with a minimum occurrence of 25. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 8.

Visualization of the superimposition of the co-occurrence network within the authors’ keywords, with a minimum occurrence of 25. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 8.

Visualization of the superimposition of the co-occurrence network within the authors’ keywords, with a minimum occurrence of 25. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 9.

Visualization of the co-occurrence network within the keyword index, with a minimum occurrence of 25. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 9.

Visualization of the co-occurrence network within the keyword index, with a minimum occurrence of 25. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 10.

Visualization of the superimposition of the co-occurrence network within the keyword index, with a minimum number of 25 occurrences. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 10.

Visualization of the superimposition of the co-occurrence network within the keyword index, with a minimum number of 25 occurrences. Source: authors’, based on VOSviewer with fractional counting.

Figure 11.

Cloud of the 30 most frequent keywords in titles. Source: authors’ results, based on Biblioshiny.

Figure 11.

Cloud of the 30 most frequent keywords in titles. Source: authors’ results, based on Biblioshiny.

Figure 12.

Trend in keywords in titles with a frequency of at least 5%. Source: authors’, based on Biblioshiny.

Figure 12.

Trend in keywords in titles with a frequency of at least 5%. Source: authors’, based on Biblioshiny.

Figure 13.

Trend in authors’ keywords with a frequency of at least 5%. Source: authors’, based on Biblioshiny.

Figure 13.

Trend in authors’ keywords with a frequency of at least 5%. Source: authors’, based on Biblioshiny.

Figure 15.

Quadrant of themes. Source: authors, based on Biblioshiny.

Figure 15.

Quadrant of themes. Source: authors, based on Biblioshiny.

Table 1.

Most influential journals with at least 50 publications.

Table 1.

Most influential journals with at least 50 publications.

| Rank |

Source |

h_index |

g_index |

m_index |

TC |

NP |

PY_start |

| 1 |

Journal of Financial Stability |

32 |

53 |

1.60 |

3159 |

104 |

2006 |

| 2 |

International Review of Financial Analysis |

28 |

46 |

1.22 |

2411 |

91 |

2003 |

| 3 |

Journal of International Money and Finance |

30 |

50 |

1.30 |

2777 |

90 |

2003 |

| 4 |

Journal of Banking and Finance |

35 |

64 |

1.46 |

4209 |

81 |

2002 |

| 5 |

Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money |

22 |

38 |

1.10 |

1737 |

80 |

2006 |

| 6 |

Economic Modelling |

23 |

37 |

1.64 |

1648 |

74 |

2012 |

| 7 |

Research in International Business and Finance |

23 |

39 |

1.28 |

1693 |

72 |

2008 |

| 8 |

North American Journal of Economics and Finance |

20 |

29 |

1.67 |

1011 |

70 |

2014 |

| 9 |

International Review of Economics and Finance |

15 |

30 |

1.25 |

1033 |

67 |

2014 |

| 10 |

Finance Research Letters |

18 |

34 |

1.50 |

1220 |

54 |

2014 |

| 11 |

International Journal of Finance and Economics |

15 |

23 |

0.69 |

600 |

53 |

2004 |

Table 2.

Most influential journals with at least 1,000 citations.

Table 2.

Most influential journals with at least 1,000 citations.

| Rank |

Source |

h-index |

g-index |

m_index |

TC |

NP |

PY_start |

| 1 |

Journal of Banking and Finance |

35 |

64 |

1.46 |

4209 |

81 |

2002 |

| 2 |

Journal of Financial Stability |

32 |

53 |

1.60 |

3159 |

104 |

2006 |

| 3 |

Journal of International Money and Finance |

30 |

50 |

1.30 |

2777 |

90 |

2003 |

| 4 |

International Review of Financial Analysis |

28 |

46 |

1.22 |

2411 |

91 |

2003 |

| 5 |

Journal of Political Economy |

1 |

1 |

0.04 |

2123 |

1 |

2000 |

| 6 |

Journal of Financial Economics |

14 |

17 |

0.67 |

1953 |

17 |

2005 |

| 7 |

Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money |

22 |

38 |

1.10 |

1737 |

80 |

2006 |

| 8 |

Research in International Business and Finance |

23 |

39 |

1.28 |

1693 |

72 |

2008 |

| 9 |

Economic Modelling |

23 |

37 |

1.64 |

1648 |

74 |

2012 |

| 10 |

Energy Economics |

19 |

37 |

2.11 |

1641 |

37 |

2017 |

| 11 |

Finance Research Letters |

18 |

34 |

1.50 |

1220 |

54 |

2014 |

| 12 |

Journal of Risk and Financial Management |

9 |

34 |

1.29 |

1172 |

42 |

2019 |

| 13 |

International Review of Economics and Finance |

15 |

30 |

1.25 |

1033 |

67 |

2014 |

| 14 |

North American Journal of Economics and Finance |

20 |

29 |

1.67 |

1011 |

70 |

2014 |

Table 3.

Most influential authors with at least 12 publications.

Table 3.

Most influential authors with at least 12 publications.

| Rank |

Author |

h_index |

g_index |

m_index |

TC |

NP |

PY_start |

| 1 |

Mensi W |

11 |

18 |

1.10 |

399 |

18 |

2016 |

| 2 |

Vo X V |

12 |

15 |

2.00 |

427 |

15 |

2020 |

| 3 |

Umar Z |

11 |

15 |

1.57 |

603 |

15 |

2019 |

| 4 |

Sosvilla-Rivero S |

9 |

15 |

0.69 |

385 |

15 |

2013 |

| 5 |

Wang X |

7 |

12 |

1.00 |

146 |

14 |

2019 |

| 6 |

Corbet S |

11 |

13 |

1.22 |

703 |

13 |

2017 |

| 7 |

Ap Gwilym O |

8 |

13 |

0.57 |

240 |

13 |

2012 |

| 8 |

Shahzad SJH |

9 |

12 |

1.00 |

519 |

12 |

2017 |

| 9 |

Kang SH |

8 |

12 |

0.80 |

307 |

12 |

2016 |

| 10 |

Foglia M |

7 |

12 |

1.00 |

180 |

12 |

2019 |

| 11 |

Li J |

7 |

12 |

0.58 |

149 |

12 |

2014 |

| 12 |

Dungey M |

6 |

12 |

0.55 |

264 |

12 |

2015 |

| 13 |

Li Y |

5 |

10 |

0.71 |

115 |

12 |

2019 |

Table 4.

Most influential authors with at least 600 citations.

Table 4.

Most influential authors with at least 600 citations.

| Rank |

Author |

h-index |

g_index |

m_index |

TC |

NP |

PY_start |

| 1 |

Allen F |

4 |

4 |

0.15 |

2270 |

4 |

2000 |

| 2 |

Gale D |

2 |

2 |

0.08 |

2166 |

2 |

2000 |

| 3 |

Gabauer D |

4 |

4 |

0.67 |

1551 |

4 |

2020 |

| 4 |

Chatziantoniou I |

3 |

4 |

0.43 |

1135 |

4 |

2019 |

| 5 |

Antonakakis N |

1 |

1 |

0.17 |

940 |

1 |

2020 |

| 6 |

Louzis D P |

4 |

5 |

0.29 |

893 |

5 |

2012 |

| 7 |

Vouldis A T |

3 |

4 |

0.21 |

869 |

4 |

2012 |

| 8 |

Corbet S |

11 |

13 |

1.22 |

703 |

13 |

2017 |

| 9 |

Ji Q |

8 |

9 |

0.89 |

652 |

9 |

2017 |

| 10 |

Metaxas V L |

1 |

1 |

0.07 |

625 |

1 |

2012 |

| 11 |

Acharya V V |

5 |

5 |

0.45 |

615 |

5 |

2015 |

| 12 |

Umar Z |

11 |

15 |

1.57 |

603 |

15 |

2019 |

Table 5.

Most influential papers with at least 250 citations.

Table 5.

Most influential papers with at least 250 citations.

| Rank |

Authors |

Title |

Cited by |

Source title |

| 1 |

Allen F.; Gale D. (2000) |

Financial contagion |

2123 |

Journal of Political Economy |

| 2 |

Antonakakis N.; Chatziantoniou I.; Gabauer D. (2020) |

Refined Measures of Dynamic Connectedness based on Time-Varying Parameter Vector Autoregressions |

940 |

Journal of Risk and Financial Management |

| 3 |

Louzis D.P.; Vouldis A.T.; Metaxas V.L. (2012) |

Macroeconomic and bank-specific determinants of non-performing loans in Greece: A comparative study of mortgage, business and consumer loan portfolios |

625 |

Journal of Banking and Finance |

| 4 |

Ando T.; Greenwood-Nimmo M.; Shin Y. (2022) |

Quantile Connectedness: Modeling Tail Behavior in the Topology of Financial Networks |

484 |

Management Science |

| 5 |

Pan J.; Singleton K.J. (2008) |

Default and recovery implicit in the term structure of sovereign CDS spreads |

423 |

Journal of Finance |

| 6 |

Bekaert G.; Harvey C.R. (2003) |

Emerging markets finance |

417 |

Journal of Empirical Finance |

| 7 |

Demirer M.; Diebold F.X.; Liu L.; Yilmaz K. (2018) |

Estimating global bank network connectedness |

414 |

Journal of Applied Econometrics |

| 8 |

Furfine C.H. (2003) |

Interbank exposures: Quantifying the risk of contagion |

338 |

Journal of Money, Credit and Banking |

| 9 |

Acharya V.V.; Steffen S. (2015) |

The greatest carry trade ever? Understanding eurozone bank risks |

319 |

Journal of Financial Economics |

| 10 |

Summers L.H. (2000) |

Richard T. Ely Lecture: International financial crises: Causes, prevention, and cures |

319 |

American Economic Review |

| 11 |

Neaime S.; Gaysset I. (2018) |

Financial inclusion and stability in MENA: Evidence from poverty and inequality |

318 |

Finance Research Letters |

| 12 |

Gabaix X.; Maggiori M. (2015) |

International liquidity and exchange rate dynamics |

303 |

Quarterly Journal of Economics |

| 13 |

Balcilar M.; Gabauer D.; Umar Z. (2021) |

Crude Oil futures contracts and commodity markets: New evidence from a TVP-VAR extended joint connectedness approach |

298 |

Resources Policy |

| 14 |

Greenwood R.; Landier A.; Thesmar D. (2015) |

Vulnerable banks |

287 |

Journal of Financial Economics |

| 15 |

Mathis J.; McAndrews J.; Rochet J.-C. (2009) |

Rating the raters: Are reputation concerns powerful enough to discipline rating agencies? |

283 |

Journal of Monetary Economics |

| 16 |

Panizza U.; Sturzenegger F.; Zettelmeyer J. (2009) |

The economics and law of sovereign debt and default |

282 |

Journal of Economic Literature |

| 17 |

Frankel J.; Saravelos G. (2012) |

Can leading indicators assess country vulnerability? Evidence from the 2008-09 global financial crisis |

276 |

Journal of International Economics |

| 18 |

Duchin R.; Sosyura D. (2014) |

Safer ratios, riskier portfolios: Banks’ response to government aid |

264 |

Journal of Financial Economics |

| 19 |

Okorie D.I.; Lin B. (2021) |

Stock markets and the Covid-19 fractal contagion effects |

259 |

Finance Research Letters |

| 20 |

Acharya V.V.; Eisert T.; Eufinger C.; Hirsch C. (2019) |

Whatever It Takes: The Real Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy |

255 |

Review of Financial Studies |

Table 6.

Countries of corresponding authors with at least 50 publications.

Table 6.

Countries of corresponding authors with at least 50 publications.

| Rank |

Country |

Articles |

Articles % |

SCP |

MCP |

MCP % |

| 1 |

China |

359 |

12.09 |

234 |

125 |

34.82 |

| 2 |

Germany |

177 |

5.96 |

96 |

81 |

45.76 |

| 3 |

Italy |

171 |

5.76 |

104 |

67 |

39.18 |

| 4 |

USA |

165 |

5.56 |

159 |

6 |

3.64 |

| 5 |

France |

162 |

5.46 |

67 |

95 |

58.64 |

| 6 |

United Kingdom |

161 |

5.42 |

136 |

25 |

15.53 |

| 7 |

Australia |

139 |

4.68 |

53 |

86 |

61.87 |

| 8 |

Greece |

107 |

3.6 |

65 |

42 |

39.25 |

| 9 |

Spain |

93 |

3.13 |

78 |

15 |

16.13 |

| 10 |

India |

69 |

2.32 |

55 |

14 |

20.29 |

| 11 |

Turkey |

61 |

2.05 |

48 |

13 |

21.31 |

| 12 |

Belgium |

51 |

1.72 |

17 |

34 |

66.67 |

Table 7.

Ranking of countries with at least 100 publications and at least 1,000 citations.

Table 7.