1. Introduction

Semiconductor nanomaterials have been extensively researched for the past decades. In large part this is due to their robust and often tunable optical properties. The focal point of this attention has gradually shifted from colloidal AIIBVI quantum dots [

1] to the largely lead-based perovskite systems [

2], and then to the more sophisticated materials like nanoplatelets (NPLs) [

3] and colloidal quantum shells [

4]. The same optical properties are frequently used as a readily available and quick probe of the mean size of an ensemble, polydispersity [

5] or concentration of nanoparticles. It is not surprising then, that the seminal work of Peng et al. on calibration curves for cadmium chalcogenide quantum dots [

6] has accumulated more than 6 thousand citations to date.

Nanoplatelets are flexible 2D nanostructures, that are essentially monodisperse in their thickness of just several atomic layers, but can be grown to hundreds of nanometers in their lateral dimensions [

7,

8,

9]. Their inorganic cores are almost entirely "surface" in the sense the whole lattice is distorted and a lowered crystal symmetry can be observed in diffraction patterns [

9]. Of course, in these conditions the surface capping agent plays an integral role in formation and stabilization of the material and can even impart its own properties, like optical rotation, on the inorganic core [

9]. NPLs are also sought for due to their uniquely narrow absorption and photoluminescence features [

10] and giant oscillator strengths at low temperatures [

11], high exciton binding energy [

12], picosecond radiative recombination and high efficiency [

13].

Unexpectedly, the literature corpus on absorption coefficients of atomically-thin NPLs consists of only a few well-executed studies. CdSe is, yet again, the more studied system: the spectral dependencies were reported not only on the principal parameter of NPL thickness [

14,

15,

16,

17], but also on the lateral size, on which an unusual non-quadratic scaling was observed [

14]. The same set of publications also contains theoretical insight into absorption coefficients. As for CdTe NPLs, there is a single work [

18] on these objects wherein UV-Vis spectroscopy was combined with optical profilometry to obtain an absorption coefficient α of 1.5·10

4 cm

-1 for thin films.

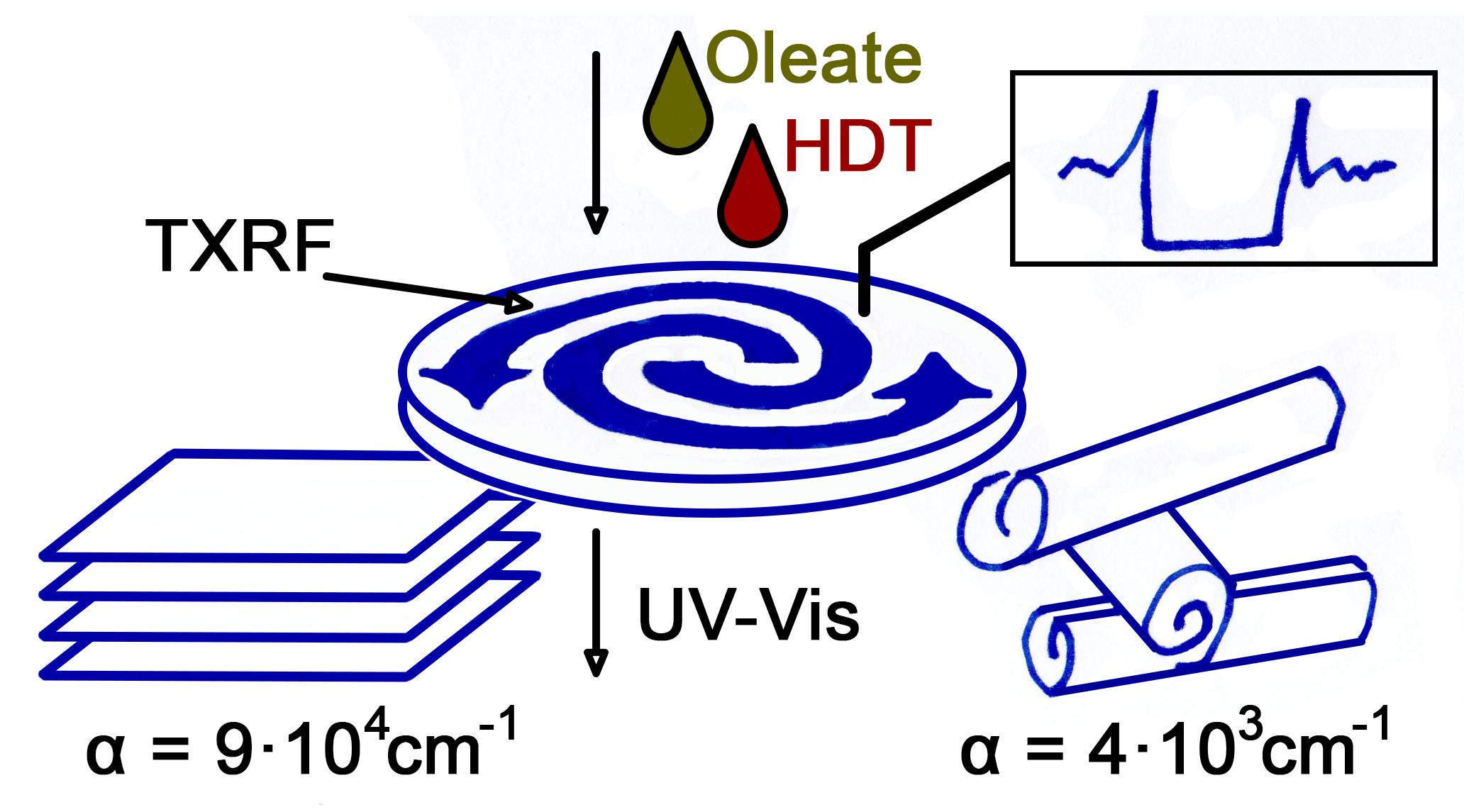

The elemental composition and narrow band gap (1.44 eV) of CdTe make NPLs of this compound one of the most promising materials for photovoltaics, photodetection and radiation detection [

19]. The flat two-dimensional shape of CdTe nanosheets enhances their technological compatibility with flexible substrates and typical microfabrication methods, expanding the possibilities of use in flexible electronic and optoelectronic systems. In our work we would like to build upon the existing work on the optical response of CdTe NPL films with addition of another powerful characterization technique – TXRF spectroscopy. In a “bottom-up” approach to our deductions, we aim to explore the relations between the nature of passivating ligand, nanomorphology and light attenuation in a NPL film.

3. Results and Discussion

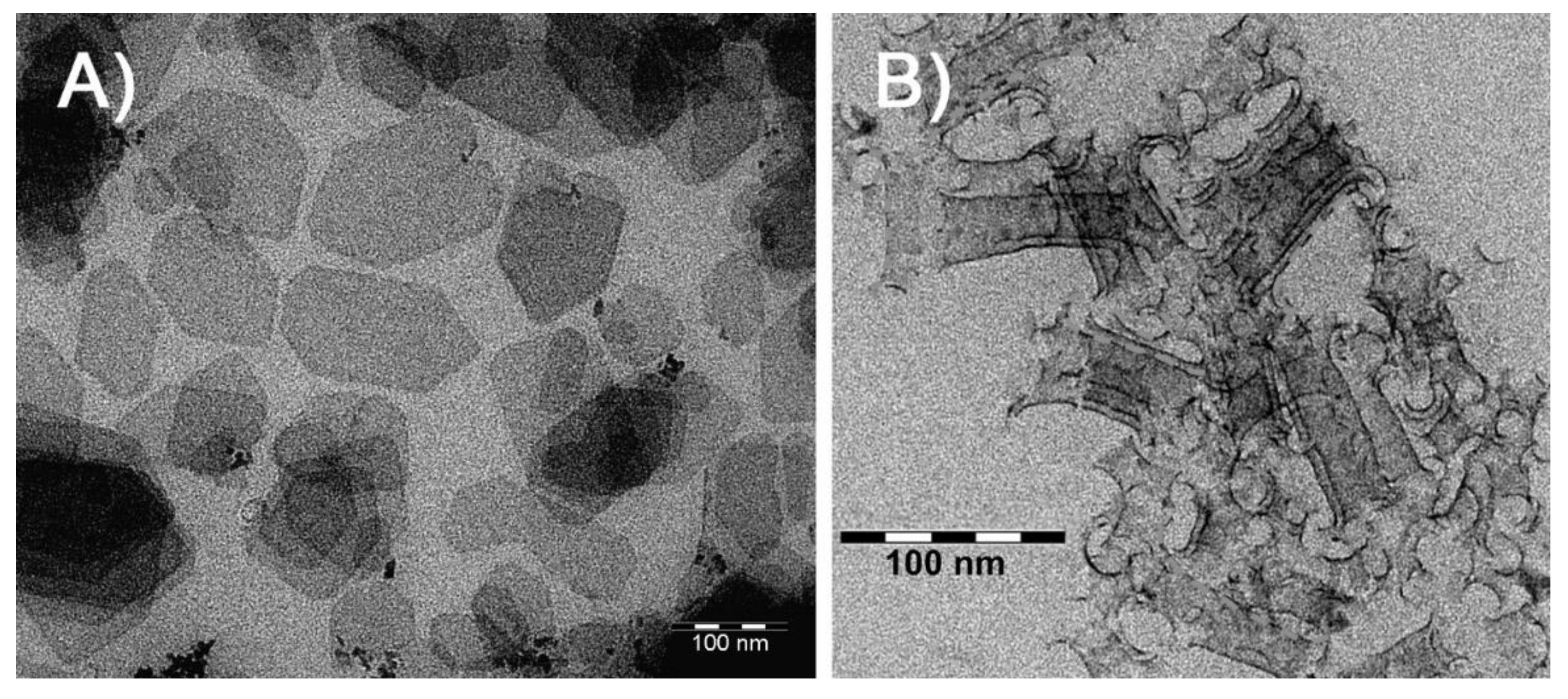

We start our discussion by examining the dimensions and morphology of the studied particles. Determination of NPL thickness is a cumbersome task, however, it can be circumvented by the fact that it stays constant within a certain NPL population. The population itself is uniquely characterized by the position of its first absorption maximum. In our case, the position at 500 nm corresponds to 3.5 monolayer 1.9±0.3 nm thick CdTe nanoplatelets [

18]. The lateral dimensions of unexchanged NPLs were obtained with TEM imaging (

Figure 1(a)). The fabricated NPL gravitate towards predominantly rectangular shape, often with splayed angles. Their mean lateral dimensions are 110×70 nm

2, the distributions of lengths, widths and basal plane areas are given in Section S1 of the Supplementary Information. Exchange of stabilizer with thiol, expectedly [

7], leads to formation of nanoscrolls with mean radius of curvature of 9 nm (

Figure 1(b)).

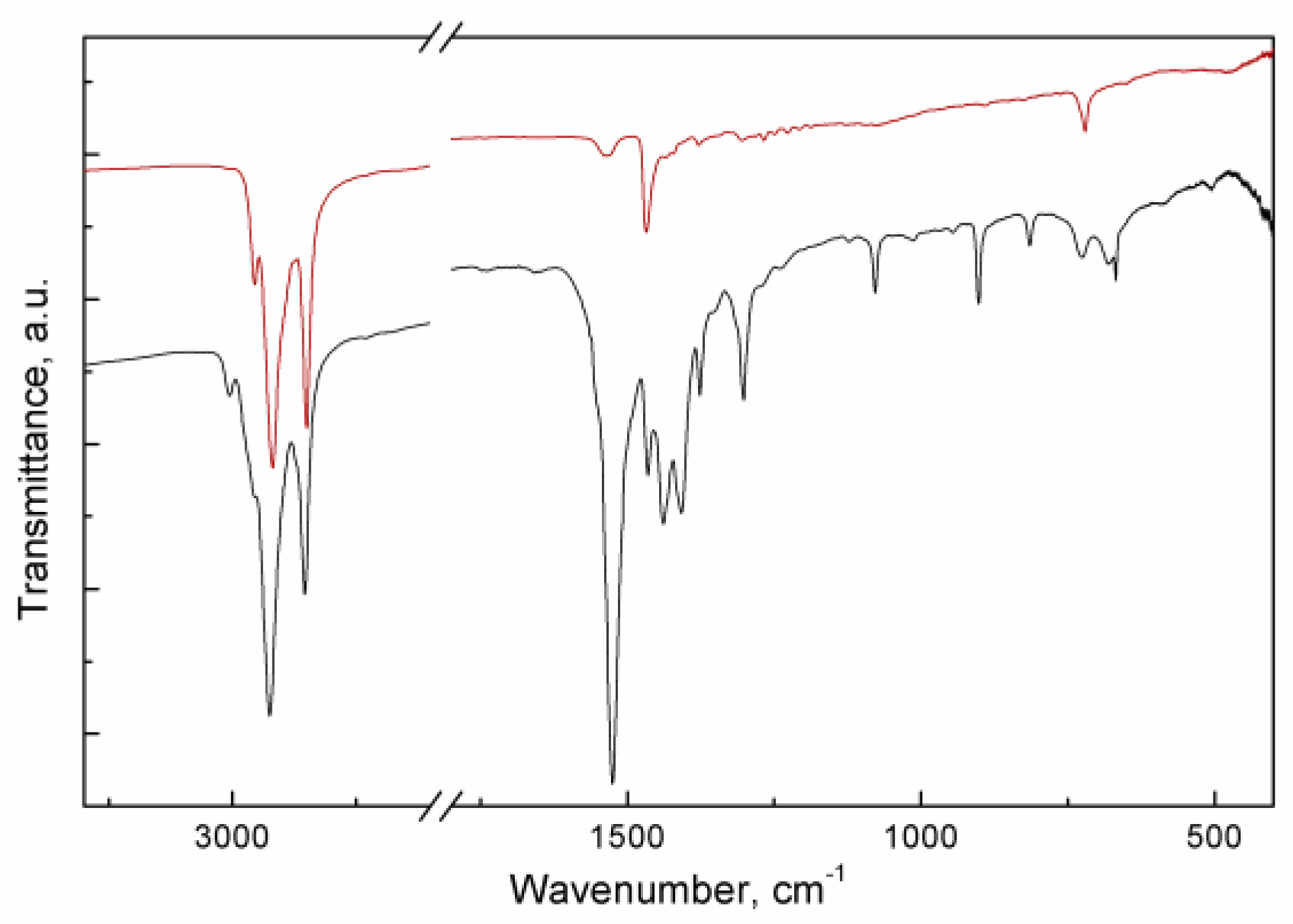

Ligand exchange is confirmed by IR spectra as well (

Figure 2). After thiol treatment almost the entirety of the spectrum is explained with C-H vibrations: functional group region only reveals characteristic C-H bands:

νas(CH

3) at 2955 cm

-1,

νas(CH

2) at 2920 cm

-1,

νs(CH

2) at 2850 cm

-1, scissoring vibration of CH

2 at 1470 cm

-1, rocking vibration of CH

2 at 720 cm

-1 [

21]. At the same time, the contribution of carboxylate vibrations is greatly diminished: only the strongest band of

νas can be seen at 1530 cm

-1. The spectrum of the original NPLs is richer in features. For instance, ν(=C-H) is seen at 3010 cm

-1 and (COO

-) – at 1410 cm

-1 [

9,

21].

Next, we explore the properties of NPLs in the form of thin films. For these objects the question of thickness is of utmost importance. In this work we assessed the thickness with two methods: step-profilometry and XRF. Profilometry allows to study thickness at a granular level, assess the film's surface roughness, measure absolute thickness values. Surface roughness was characterized with

Ra parameter, the values of which were found for individual profiles and then averaged. The individual profile measurements for the film of thiol-covered NPLs were within 110 – 125 nm range and worked out to

Ra of 120 nm. We averaged the thickness values within each profile and treated the result as a single measurement for the sake of statistics. The results are present in

Table 1. The average thickness of this film is 590±60 nm. The uniformity is about ±15% of this value within 2 mm radius of the film’s center – a region, from which TXRF and UV/Vis absorption data were collected and where the thickness was studied. The relative value of roughness of the film of thiolated NPLs amounts to 20%. For a film of carboxylated NPLs we likewise obtain

Ra of 20 nm and a mean thickness of 127±11 nm. The film is significantly thinner, but the quality in terms of relative parameters is similar to the thiolated case.

The thickness can also be evaluated via XRF, which serves as a complementary technique. When the thickness of the film is low, so that attenuation of outgoing characteristic X-rays is less than 5%, the intensity of characteristic fluorescence is proportionate to the areal density of an element. If we assume consistent density within one film and between different films of the same material and deposition conditions, then XRF intensity is proportionate to the film's thickness. As tungsten anode bremsstrahlung maximum lies at lower energy than TeKα, we only computed the intensity of the CdKα line. We did so by integration in the spectral region of 22.96 – 23.36 keV after the background was fit locally with a straight line. The choice of integration window is to minimize the error (Section S2 of the Supplementary Information). XRF measurements corroborate the profilometry results on film uniformity, the size of signal acquisition area does not allow to obtain roughness. We note here, that the precision of XRF as a thickness probe was comparable or better than that of step-profilometry, however, XRF thickness is in arbitrary units, so the final calculation would include the error of a direct method as well.

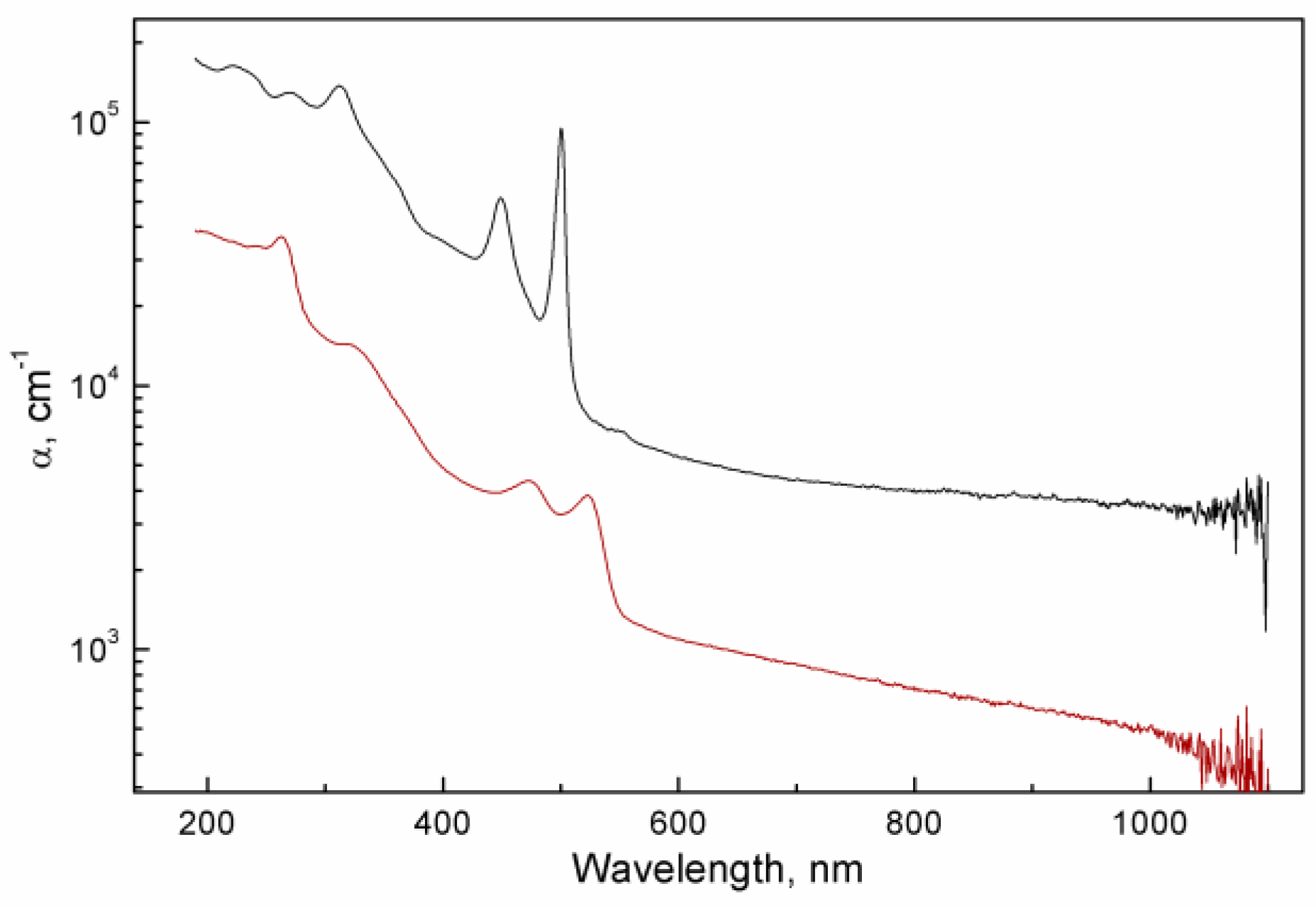

As UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy is a non-destructive method, it was possible to study the same films prior to profilometry. Absorbance values can then be normalized by the thickness to produce the spectral dependencies of the absorption coefficient α (

Figure 3).

(black line) and thiol-exchanged (red line) NPLs.

A film made up of carboxylated NPLs attenuates light much more efficiently per unit length of optical path. In the region of 400 – 600 nm, where the respective first (electron – heavy hole) excitonic maxima of absorption are situated, the difference amounts to 1.5 orders of magnitude. Specifically,

α500 for carboxylated NPLs is measured to be 94700 cm

-1, while

α523 for the thiolated sample is 3840 cm

-1. These can be immediately compared to the previously measured value of 1.5·10

4 cm

-1 for the films of the same carboxylated CdTe NPLs [

18] and (2 – 3)·10

4 cm

-1 measured for different populations of CdSe NPLs [

15]. The observed differences between all these values are likely due to different efficiency of packing, as the films in Ref.18 were obtained with drop-casting. For a crystalline CdTe slab, the absorption coefficient is around 10

4-10

5 cm

-1 across the visible part of the spectrum [

22]: the band edge is immediately in its vicinity in the IR region for this direct narrow-band semiconductor. Transition into ultradisperse state blue-shifts the band gap and increases the oscillator strength of HOMO-LUMO transition because of quantum confinement [

23]. Taking all these considerations into account, our observations are consistent with dilute films of CdTe NPLs.

Absorption coefficient α is the product of molar absorption coefficient ε and concentration, which is directly proportional to density of the film with respect to the light-absorbing material. To decouple the contribution of these factors to the observed difference between carboxylated and thiolated NPL films, we have studied another set of films with TXRF and absorption spectroscopy.

So long as the film is infinitesimally thin for the characteristic fluorescence, absolute masses of the elements are determined within the signal acquisition spot. These can be normalized for the area of the film to obtain areal density. When the latter parameter is divided over the molar mass, we obtain the

c·

l product of the Beer-Lambert’s law. Selected parameters from TXRF studies as presented in Table 2. We have used the values of areal density to confirm the correctness of the analysis. Mass attenuation coefficients

μ for CdLα, TeLα and SKα [

24] were divided by cos(30º), which is the mean angle between the normal to the sample and the detector of our instrument, as discussed in another our work, which currently under consideration [

25]. The attenuation by organic matter was introduced as an additional term to

μCd values, seen as organic stabilizers are bound to surface cadmium atoms. For the sake of this calculation, we estimated that 1 stabilizer moiety is present in the samples for every 2 Cd atoms (Cd

4Te

3X

2 formula unit, where X is the organic stabilizer).

Even when multiplied by an angle-based factor, all

μ values are below 1800 cm

2/g (Section S3 of the Supplementary Information). From summation over the products

ρA·μ we obtain that every line in question would be attenuated by less than 1% even by the full thickness of the film. Mean attenuation is then less than 0.5%, which is lower than the uncertainly in area determination, so no correction for the sample self-absorption was adopted. The Cd-to-Te ratio has changed dramatically after the ligand exchange procedure. While there are no apparent indications of this process in TEM images, we suggest that some of the NPLs could be etched with the excess of hexadecanethiol. The resultant cadmium thiolate is soluble in non-polar organics, is not colored, and therefore could remain unnoticed in the sample. Tellurides, on the other hand, are readily oxidized to the elemental form, which is insoluble and produces very apparent changes in the color of the sample. Due to that, we link the quantity of NPLs with Te content and normalize for it. Chalcogenide content has been used previously when there was a similar ambiguity in

ε determination [

14].

A factor of 4.63±0.15 difference remains between the molar absorption coefficients. It follows that there is 5-fold change in the volume fraction of CdTe cores fraction between the films of carboxylated and thiolated NPLs. This, of course, was indicated earlier by the XRF signal values for the first set of films (

Table 1). We quantify the volume fraction by calculating concentration with the use of both

α and

ε values for the two sets of films, as well as density of bulk CdTe of 5.85 g/cm

3. Films of carboxylated CdTe exhibit a volume fraction of inorganic cores of 8%, thiolated films - 1.5%. The densest possible packing occurs through stacking of NPLs and interdigitation of organic terminating chains. In a stack on NPLs the volume fraction of cores can be assessed by relating the core thickness to the stacking period, measured with TEM. For the 500 nm population of alkylated CdTe NPLs an estimate of 30 – 40% can be obtained from the literature [

18].

The difference in packing density appears feasible. Pre-formed scrolls are incapable of stacking in the same manner as flat NPLs. The folding is spontaneous and therefore should reach only local energy maxima. Inherent (comparatively) poor control over lateral dimensions of NPLs [

26,

27] leads to scrolls that are mismatched in their form, working further to slightly detriment the density of closest attainable packing. Moreover, there is a "dead volume" inside of the scroll, which is unable to accommodate other NPL cores. We advocate for the combination of (T)XRF spectroscopy and profilometry of thin films as a fast and high-throughput technique to evaluate or control NPL morphology. We have to note that XRF intensity is very well correlated to absorbance when we compare different films of the same material (

Table 1 and

Table 2,

Figure 3).

When the difference in packing is accounted for, the difference in the intensity of optical response between NPLs with different anchor groups of ligands remains very substantial. Quantitative models for a quantum well always include direct proportionality between the absorption cross-section and frequency [

14,

16,

18], however, between 500 and 523 nm there is only a factor of 1.05 difference. Next, we evaluate surface and dielectric effects. A particular study [

28] has shown that the per-mole-value of ε for ZnSe colloidal quantum dots grows sharply with decreasing nanocrystal diameter, already reaching 10

4 M

-1·cm

-1 at the first maximum frequency for the mean diameter of 4 nm. This can be rationalized either with the effect of quantum confinement on the electron-hole pair, or with better electromagnetic field penetration of the cores [

16]. Both these effects work to the advantage of NPLs in terms of the magnitude of ε [

16,

17], moreover, in the case of CdTe both elements are the heavier counterparts to the components of ZnSe, and have higher polarizability that is beneficial for light-matter interactions. The value of ε was measured at 2·10

4 M

-1·cm

-1 for 513 nm population of CdSe NPLs [

14], which is in line with our findings and deductions. We note here, that the absorption efficiency is also frequently presented as intrinsic absorption coefficient, we calculate this value for oleate-capped CdTe NPLs to be 2.8·10

6 cm

-1 at the first exciton transition, even higher than that of 2 monolayer CdSe NPLs [

17]. In the search for the ultimate light-absorbing material an investigation of thinner CdTe NPL populations is warranted.

The role of surface states was highlighted in the case of ZnSe quantum dots. Se-terminated cores have shown the values of ε at the first maximum of transition almost 2 times higher than that of their Cd-terminated counterparts [

28]. In our case, what is essentially an addition of a layer of sulfur on the surface of NPLs lowers the molar absorption coefficient by about a factor of 5. To explain that we recall that in bulk the conduction band alignment of CdTe and CdS is rather close [

29], and that strain can shift band energy in nanostructures to result in quasi-type II heterojunctions [

30,

31]. We believe that sulfur atoms in thiolated CdTe NPLs provide surface states for electrons thus decreasing the wavefunction overlap with holes.