Recent studies in science education methodology demonstrate that the mode of content presentation significantly influences the quality of new knowledge acquisition. K. Christopher and K. Nesbitt emphasize that material should be presented uniformly and consistently to enhance comprehension. Another study shows that the way material is delivered affects both learning efficiency and final outcomes.

A distinctive feature of the pre-university stage is the dual challenge of developing both linguistic and subject-specific competencies aligned with the material’s level. If subject competencies are underdeveloped due to the lack of an equivalent course in the student’s native country, compensating for this gap “results in a multiple increase in time required”.

Despite research into the scientific style of speech, the differences in symbolic notation of physical quantities across national traditions remain insufficiently addressed. This gap defines the novelty of the present study, which aims to examine these differences to develop strategies for overcoming the multiple difficulties experienced during the acquisition of physics course content.

Symbolic notation represents physical quantities conventionally using letters from the Latin or Greek alphabets, as well as Cyrillic abbreviations. To specify the letters of Latin and Greek alphabets used in physics, subscripts may be applied. According to the Big Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language under the general editorship of S.A. Kuznetsov, a subscript is defined as a “numerical or letter pointer usually placed below the letter within a mathematical expression”.

The objective of this work was to identify qualitative discrepancies between the Russian system of subscript usage for physical quantities and foreign systems. The study tasks included investigating subscripts in various national physics teaching traditions; analyzing the structure of subscript notation in the Russian system; identifying differences between national systems; and compiling a list of inconsistencies.

As a starting reference, the FIPI recommendations for the Unified State Exam preparation in Russia were selected, covering the following physics sections: Mechanics; Molecular Physics and Thermodynamics; Electrodynamics (electric field, DC laws, magnetic field); Electrodynamics (electromagnetic induction, oscillations and waves, optics); and Quantum Physics.

Comparison materials were drawn from publicly available resources, including Wikipedia pages in English, Chinese, Arabic, Vietnamese, and Persian languages. The methodology employed general scientific methods of comparison and classification.

In total, 120 symbolic notations from the Russian tradition of physics teaching were analyzed, with 27 involving subscripts. The analysis of subscript structure revealed the following classification by origin:

abbreviations (e.g., Fравн)

acronyms (e.g., Fт)

shortened forms tending toward acronyms (e.g., ацс)

- 2.

Latin (e.g., WL)

- 3.

Greek (e.g., P)

- 4.

Numeric (e.g., R0)

- 5.

Abstract (e.g., t°)

Cyrillic subscripts were found to be the most frequently used.

Subscripts were also classified by their position relative to the main symbol:

right-lower (e.g., Fx)

right-upper (e.g., t°)

left-upper (e.g., mass number)

left-lower (e.g., charge number)

A notable feature of subscript use in the Russian tradition is the openness of the list of Cyrillic abbreviations, allowing instructors to introduce new subscripts to specify physical quantities as needed. Additionally, synonymy of subscripts of different origins was observed (e.g., Fупр and Fx).

Comparison of Russian subscripts with those in other national traditions revealed several discrepancies:

-

Mismatch between Cyrillic and Latin subscripts.

For example, friction force is denoted as Fтр in Russia and Ff in American tradition.

-

Absence of a subscript in one system.

Boltzmann’s constant is represented as k without a subscript in the Russian tradition, while in Chinese, English, Arabic, Persian, and Vietnamese systems it is kB.

-

Replacement of a subscript with a diacritical mark.

For instance, molar volume is noted as Vm in Russia but with a tilde (Ṽ) in the Chinese system. Such diacritic use was not found in the analyzed Russian materials.

Variation in subscript placement.

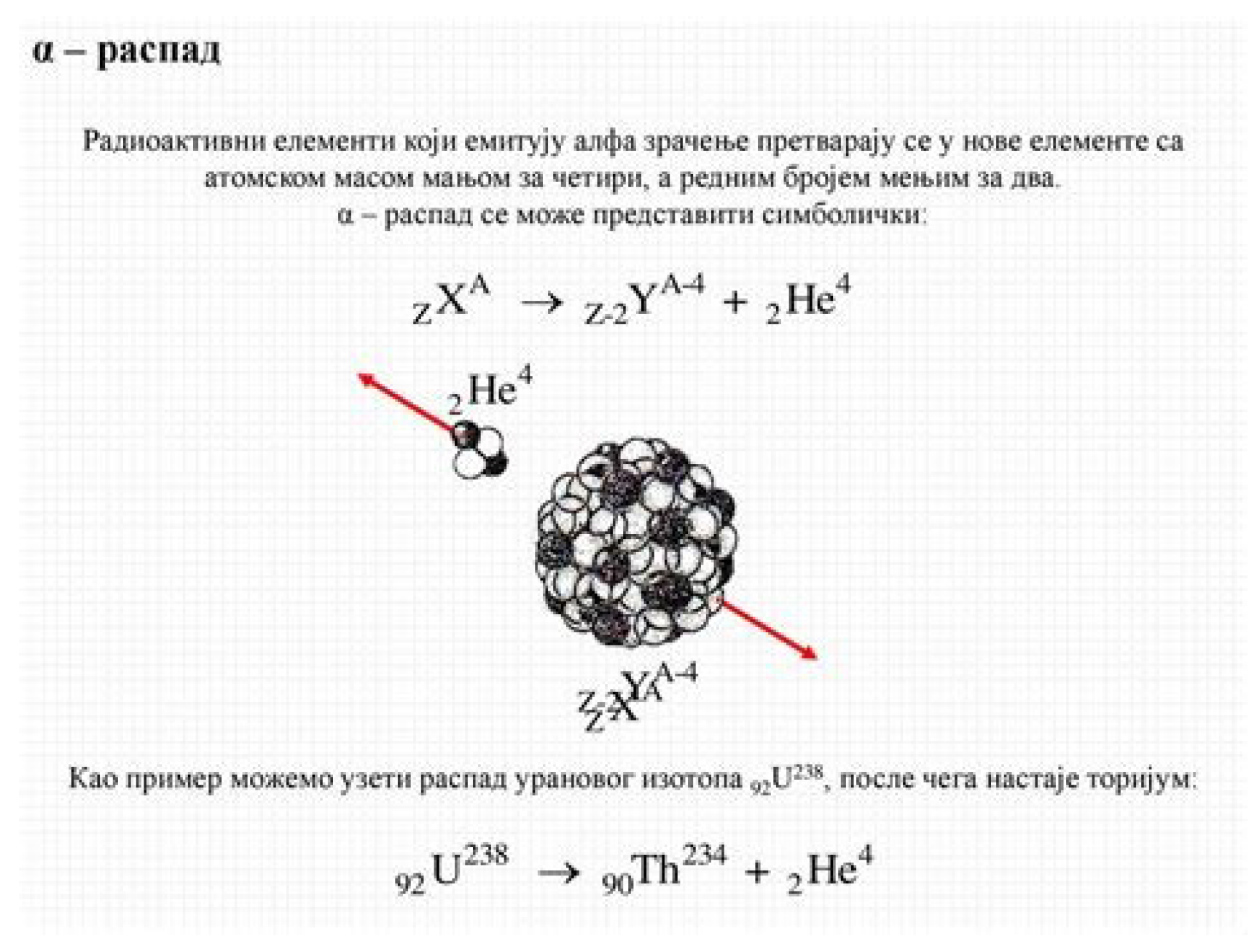

Figure 1.

Illustrates that the mass number is positioned to the left above the element symbol in Russian notation, but to the right above in Serbian tradition.

Figure 1.

Illustrates that the mass number is positioned to the left above the element symbol in Russian notation, but to the right above in Serbian tradition.

The most frequent discrepancy detected was linguistic differences in abbreviations and acronyms. Consequently, the data analyzed provide evidence for divergence in subscript notation of physical quantities across national traditions. These include language-based inconsistencies in identical subscript types, atypical substitution of subscripts by diacritical marks absent from the Russian tradition, and presence of subscripts where Russian notation omits them.

It should be noted that discrepancies in subscript use are only part of broader divergences in physical symbolic notations, as the symbols themselves may differ between national physics teaching traditions. All these factors contribute to multiple difficulties complicating the mastery of physics course content at the preparatory stage.

At this stage, only qualitative differences in subscript notation have been identified. Further research will aim to quantify the frequency and statistical significance of the detected discrepancies. Additionally, it is important to investigate other types of inconsistencies in physical symbolic notation.

Ethical Statement

This study does not require an ethical statement, as it involves the analysis of publicly available academic publications and does not include any human or animal subjects or sensitive data.

References

- Christofer, C., & Nesbitt, K. (2023). Consistency and inconsistency in learning experiences across the early grades. Educational Psychology, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P., Kumar, N., & Ting, H. (2023). An impact of content delivery, equity, support and self-efficacy on student’s learning during the COVID-19. Current Psychology, 42(3), 2460–2470. [CrossRef]

- Lagun, I. M., & Khvalina, E. A. (2018). Formation of language competencies in teaching natural science disciplines in a non-native language. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Scientific and Practical Conference “Teaching Natural Science and Humanities in Russian to a Foreign Language Audience” (pp. 26). Moscow.

- Kuznetsov, S. A. (Ed.). (n.d.). Big explanatory dictionary of the Russian language. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https://gramota.ru/poisk?query=%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%81&mode=slovari&dicts%5b%5d=42.

- Federal Institute of Pedagogical Measurements. (n.d.). Navigator for independent preparation for the Unified State Exam. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https://fipi.ru/navigator-podgotovki/navigator-ege#fi.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).