Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

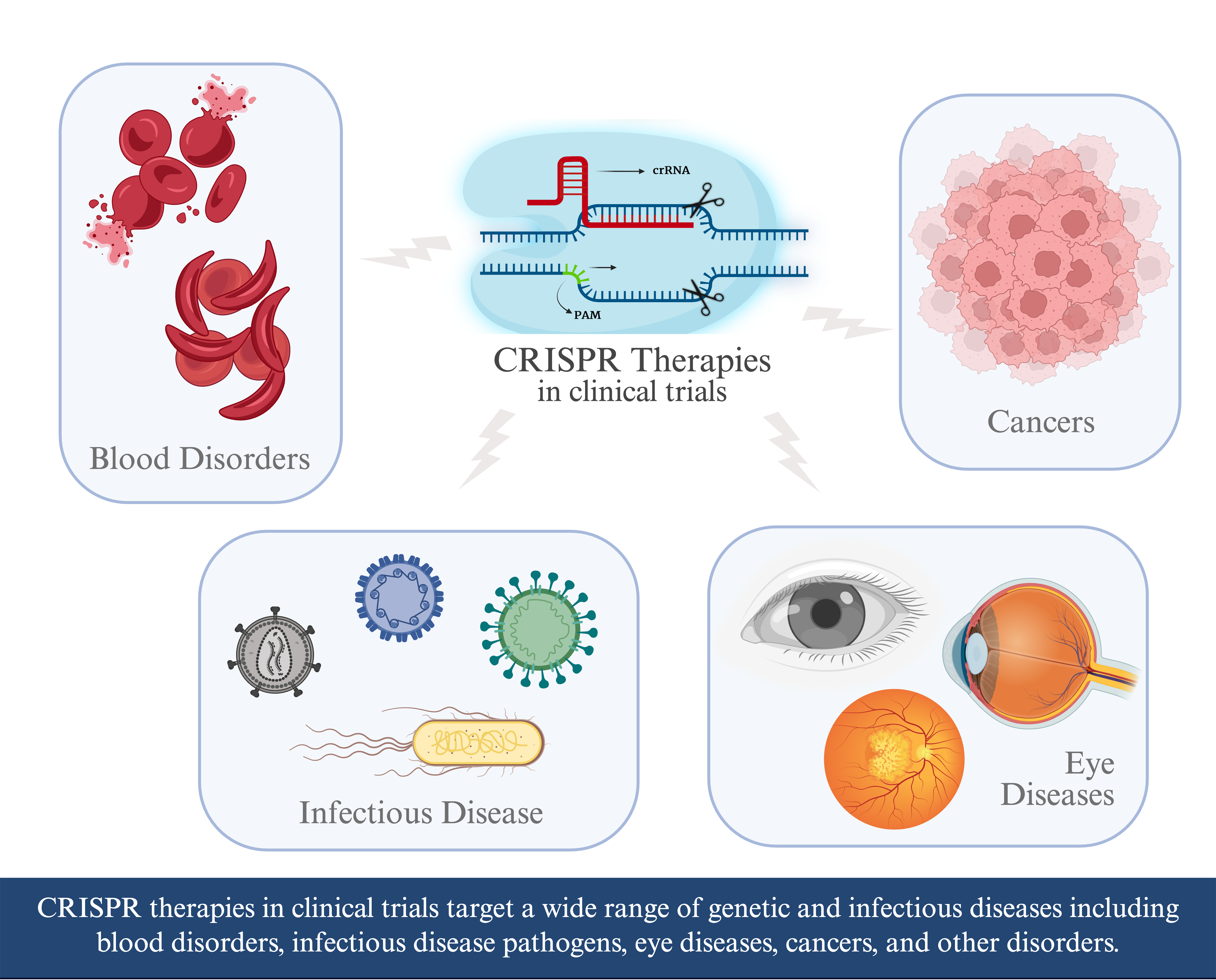

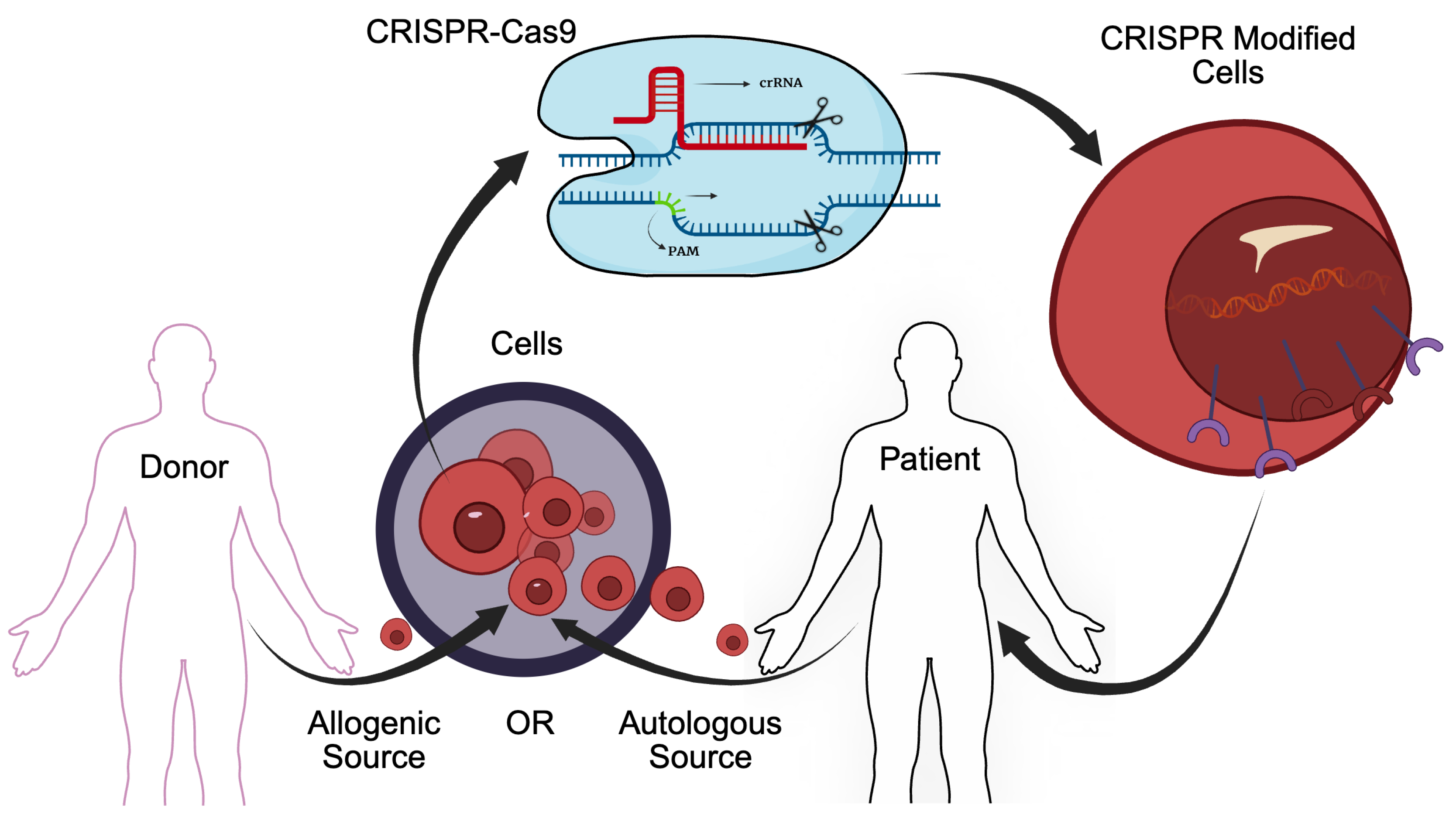

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. First Approved CRISPR-Cas9 Therapy

3. Additional CRISPR-Cas9 Therapies In Clinic Trials

4. Discussion

| Disease Category | Intervention | Study Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobinopathies | CTX001 | NCT05356195, NCT03655678, NCT05477563, NCT03745287, NCT05329649, NCT04208529, NCT05951205, NCT06287099 |

| BRL-101 | NCT06287086, NCT06300723, NCT05577312 | |

| ET-01 | NCT04925206 | |

| Plerixafor + Busulfan + Gene-modified CD34+ Cells | NCT06506461 | |

| CRISPR-SCD001 | NCT04774536 | |

| nula-cel Drug Product | NCT04819841 | |

| OTQ923 | NCT04443907 | |

| Hematologic Malignancies | CTX131 | NCT06492304, NCT04502446 |

| CTX110 | NCT04035434 | |

| Universal Dual Specificity CD19 and CD20 or CD22 CAR-T Cells | NCT03398967 | |

| CTX112 | NCT05643742 | |

| UCART019 | NCT03166878 | |

| CT125A cells + Cyclophosphamide + fludarabine | NCT04767308 | |

| PBLTT52CAR19 | NCT04557436 | |

| Donor-derived CD34+ HSC with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated CD33 deletion + emtuzumab Ozogamicin | NCT05662904 | |

| REGV131 + LNP1265 | NCT06379789 | |

| BE-101 | NCT06611436 | |

| NTLA-2002 + Normal Saline IV Administration | NCT06634420 | |

| Biological NTLA-2002 + Normal Saline IV Administration | NCT05120830 | |

| CTX120 | NCT04244656 | |

| Solid Tumor | Anti-mesothelin CAR-T cells | NCT03545815 |

| Mesothelin-directed CAR-T cells | NCT03747965 | |

| TGFR-KO CAR-EGFR T Cells | NCT04976218 | |

| MT027 cells suspension | NCT06726564 | |

| Autologous CD19-STAR-T cell + Fludarabine + Cyclophosphamide | NCT05631912 | |

| Allogeneic CD19-STAR T cell + Fludarabine + Cyclophosphamide | NCT06321289 | |

| TRAC and Power3 Genes Knock-out Allogeneic CD19-targeting CAR-T cell (ATHENA CAR-T) + Fludarabine + Cyclophosphamide | NCT06014073 | |

| CTX131 | NCT05795595 | |

| Fludarabine + Cyclophosphamide + CISH Inactivated TIL + Aldesleukin + Pembrolizumab | NCT05566223 | |

| Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization|BIOLOGICAL: PD-1 knockout engineered T cells | NCT04417764 | |

| Fludarabine + Cyclophosphamide + Interleukin-2 | NCT03044743 | |

| Cyclophosphamide + PD-1 Knockout T Cells | NCT02793856 | |

| MT027 cells suspension | NCT06742593, NCT06737146 | |

| Cyclophosphamide + Fludarabine + Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TIL) + Aldesleukin | NCT04426669 | |

| PD-1 Knockout T Cells | NCT03081715 | |

| AJMUC1- PD-1 gene knockout anti-MUC1 CAR-T cells | NCT05812326 | |

| Infectious Disease | CAZ/AVI plus Aztreonam + Conventional treatment | NCT05850871 |

| CCR5 gene modification | NCT03164135 | |

| EBT-101 | NCT05144386 | |

| TALEN + CRISPR/Cas9 | NCT03057912 | |

| PD-1 and ACE2 Knockout T Cells + PD-1 and ACE2 Knockout T Cells + PD-1 and ACE2 Knockout T Cells | NCT04990557 | |

| Ophthalmic Disorders | BD113vVLP | NCT06465537 |

| BD111 Adult single group Dose | NCT04560790 | |

| ZVS203e | NCT05805007 | |

| EDIT-101 | NCT03872479 | |

| Other Conditions | VCTX211 | NCT05565248 |

| VCTX210A unit | NCT05210530 | |

| NTLA-2001 | NCT04601051 | |

| Conclusive genetic testing + Genotype-phenotype correlation for personalized diagnosis + Personalized study of variants of uncertain clinical significance (VUS) through functional studies on 3D organ-on-a-chip | NCT06325072 |

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, Alison. 2016. A crispr vision. Nature 532(7600), 432–434.

- Banerji, A.; Busse, P.; Shennak, M.; Lumry, W.; Davis-Lorton, M.; Wedner, H.J.; Jacobs, J.; Baker, J.; Bernstein, J.A.; Lockey, R.; et al. Inhibiting Plasma Kallikrein for Hereditary Angioedema Prophylaxis. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 717–728. [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.; Kissner, T.; Gerrard, B.; Ivanov, S.; O'Brien, S.J.; Dean, M. Novel Alleles of the Chemokine-Receptor Gene CCR5. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 61, 1261–1267. [CrossRef]

- Chidharla, Anusha, Meghana Parsi, and Anup Kasi. 2023, May. Cetuximab. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459293/.

- den Hollander, A.I.; Koenekoop, R.K.; Yzer, S.; Lopez, I.; Arends, M.L.; Voesenek, K.E.; Zonneveld, M.N.; Strom, T.M.; Meitinger, T.; Brunner, H.G.; et al. Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) Gene Are a Frequent Cause of Leber Congenital Amaurosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 79, 556–561. [CrossRef]

- Drugs.com. 2024. Alemtuzumab (multiple sclerosis) (monograph). https://www.drugs.com/monograph/alemtuzumab-multiple-sclerosis.html.

- Eyquem, J.; Mansilla-Soto, J.; Giavridis, T.; van der Stegen, S.J.C.; Hamieh, M.; Cunanan, K.M.; Odak, A.; Gönen, M.; Sadelain, M. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature 2017, 543, 113–117. [CrossRef]

- FDA. 2023. FDA approves first gene therapies to treat patients with sickle cell disease. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapies-treat-patients-sickle-cell-disease.

- Feng, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Z. CRISPR/Cas9 technology for advancements in cancer immunotherapy: from uncovering regulatory mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Bin, Jiaoyang Liao, Shuanghong Chen, Wei Li, Qiudao Wang, Jian Hu, Fei Yang, Shenlin Hsiao, Yanhong Jiang, Liren Wang, et al. 2022. Crispr–cas9-mediated gene editing of the bcl11a enhancer for pediatric β0/β0 transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia. Nature medicine 28(8), 1573–1580.

- Fu, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Liao, J.; Chen, S.; Zheng, B.; Li, W.; Wang, F.; Li, D.; Liu, M.; et al. S271: AN UPDATED FOLLOW-UP OF BRL-101, CRISPR-CAS9-MEDIATED GENE EDITING OF THE BCL11A ENHANCER FOR TRANSFUSION-DEPENDENT BETA-THALASSE. HemaSphere 2023, 7, e406095b. [CrossRef]

- Godwin, C.D.; Gale, R.P.; Walter, R.B. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1855–1868. [CrossRef]

- Gridelli, Cesare, Antonio Rossi, David P Carbone, Juliana Guarize, Niki Karachaliou, Tony Mok, Francesco Petrella, Lorenzo Spaggiari, and Rafael Rosell. 2015. Non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature reviews Disease primers 1(1), 1–16.

- Hassan, R.; Thomas, A.; Alewine, C.; Le, D.T.; Jaffee, E.M.; Pastan, I. Mesothelin Immunotherapy for Cancer: Ready for Prime Time? J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4171–4179. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Zheng, Wencheng Ding, Da Zhu, Lan Yu, Xiaohui Jiang, Xiaoli Wang, Changlin Zhang, Liming Wang, Teng Ji, Dan Liu, Dan He, Xi Xia, Tao Zhu, Juncheng Wei, Peng Wu, Changyu Wang, Ling Xi, Qinglei Gao, Gang Chen, Rong Liu, Kezhen Li, Shuang Li, Shixuan Wang, Jianfeng Zhou, Ding Ma,, and Hui Wang. 2015. Talen-mediated targeting of hpv oncogenes ameliorates hpv-related cervical malignancy. The Journal of clinical investigation 125(1), 425–436.

- Hu, Zheng and CRISPR Medicine News Editorial Team. 2025, May. A safety and efficacy study of transcription activator-like effector nucleases and crispr/cas9 in the treatment of hpv-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia i (nct03057912). CRISPR Medicine News. Summarizes trial design, methods (CRISPR & TALEN targeting HPV E6/E7), plasmid-gel delivery, enrollment and status.

- Huang, D.; Li, Y.; Rui, W.; Sun, K.; Zhou, Z.; Lv, X.; Yu, L.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.; Liu, V.; et al. TCR-mimicking STAR conveys superior sensitivity over CAR in targeting tumors with low-density neoantigens. Cell Rep. 2024, 43. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Victoria. 2024, May. Crispr-editing ebt-101 therapy safe, temporarily suppresses hiv infection.

- Kalaitzidis, Demetrios, Mohammed Ghonime, Robert Chain, Nivedita Jaishankar, Davis Settipane, Zinkal Padalia, Lauren Zakas, Meghna Kuppuraju, Paul Tetteh, Mary-Lee Dequeant, et al. 2023. 274 development of ctx112 a next generation allogeneic multiplexed crispr-edited cart cell therapy with disruptions of the tgfbr2 and regnase-1 genes for improved manufacturing and potency. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J.; DiPersio, J.F.; Leavey, P.; Shyr, D.C.; A Thompson, A.; Porteus, M.H.; Intondi, A.; Lahiri, P.; Dever, D.P.; Petrusich, A.; et al. Cedar Trial in Progress: A First in Human, Phase 1/2 Study of the Correction of a Single Nucleotide Mutation in Autologous HSCs (GPH101) to Convert HbS to HbA for Treating Severe SCD. Blood 2021, 138, 1864–1864. [CrossRef]

- Kurachi, S.; Deyashiki, Y.; Takeshita, J.; Kurachi, K. Genetic Mechanisms of Age Regulation of Human Blood Coagulation Factor IX. Science 1999, 285, 739–743. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, L.; Zeng, Y.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Mu, W. Anti-CD5 CAR-T cells with a tEGFR safety switch exhibit potent toxicity control. Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Lonez, C.; Breman, E. Allogeneic CAR-T Therapy Technologies: Has the Promise Been Met?. Cells 2024, 13, 146. [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, H.; Fijen, L.; Lindsay, K.; Butler, J.; Golden, A.; Maag, D.; Xu, Y.; Cohn, D. IN VIVO CRISPR/CAS9 EDITING OF KLKB1 IN PATIENTS WITH HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA: A FIRST-IN-HUMAN STUDY. Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2022, 129, S10–S11. [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, J.P.; Tam, C.S.; Kröger, N.; Riedell, P.A.; Murthy, H.S.; Ho, P.J.; Maakaron, J.E.; Waller, E.K.; Awan, F.T.; Shaughnessy, P.J.; et al. CTX110 Allogeneic CRISPR-Cas9-Engineered CAR T Cells in Patients (Pts) with Relapsed or Refractory (R/R) Large B-Cell Lymphoma (LBCL): Results from the Phase 1 Dose Escalation Carbon Study. Blood 2022, 140, 10303–10306. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, V.; Khodabandehloo, E.; Alidadi, M.; Omidkhoda, A.; Ahmadbeigi, N. Progress and pitfalls of gene editing technology in CAR-T cell therapy: a state-of-the-art review. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1388475. [CrossRef]

- Munari, E.; Mariotti, F.R.; Quatrini, L.; Bertoglio, P.; Tumino, N.; Vacca, P.; Eccher, A.; Ciompi, F.; Brunelli, M.; Martignoni, G.; et al. PD-1/PD-L1 in Cancer: Pathophysiological, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5123. [CrossRef]

- Musunuru, K.; Grandinette, S.A.; Wang, X.; Hudson, T.R.; Briseno, K.; Berry, A.M.; Hacker, J.L.; Hsu, A.; Silverstein, R.A.; Hille, L.T.; et al. Patient-Specific In Vivo Gene Editing to Treat a Rare Genetic Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2235–2243. [CrossRef]

- Narisawa-Saito, M.; Kiyono, T. Basic mechanisms of high-risk human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis: Roles of E6 and E7 proteins. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 1505–1511. [CrossRef]

- Nathans, J.; Hogness, D.S. Isolation and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding human rhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 4851–4855. [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health. 2022. The basics. https://www.nih.gov/health-information/nih-clinical-research-trials-you/basics.

- National Library of Medicine. 2025. Rho gene: Medlineplus genetics. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/rho/#conditions.

- Oppermann, M. Chemokine receptor CCR5: insights into structure, function, and regulation. Cell. Signal. 2004, 16, 1201–1210. [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano, G.; Georgiadis, C.; Gkazi, S.A.; Syed, F.; Zhan, H.; Etuk, A.; Preece, R.; Chu, J.; Kubat, A.; Adams, S.; et al. Phase 1 clinical trial of CRISPR-engineered CAR19 universal T cells for treatment of children with refractory B cell leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabq3010. [CrossRef]

- Quigley, H.A.; Hohman, R.M.; Addicks, E.M.; Massof, R.W.; Green, W.R. Morphologic Changes in the Lamina Cribrosa Correlated with Neural Loss in Open-Angle Glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1983, 95, 673–691. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, I.; Muthalib, A.; Edina, B.C.; Wiyono, L.; Winston, K. Role of Anti-B-Cell Maturation Antigen (BCMA) in the Management of Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2022, 14, 3507. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Hiroki, K.; Yamashita, Y. The Role of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Cancer Metastasis and Microenvironment. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Scialo, F.; Daniele, A.; Amato, F.; Pastore, L.; Matera, M.G.; Cazzola, M.; Castaldo, G.; Bianco, A. ACE2: The Major Cell Entry Receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung 2020, 198, 867–877. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.M.; Irfan, H.M.; Fatima, E.M.; Nazir, Z.M.; Verma, A.M.; Akilimali, A. Revolutionary breakthrough: FDA approves CASGEVY, the first CRISPR/Cas9 gene therapy for sickle cell disease. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 4555–4559. [CrossRef]

- Terrett, JA, D Kalaitzidis, ML Dequeant, S Karnik, M Ghonime, C Guo, et al. 2023. Ctx112 and ctx131: next-generation crispr/cas9-engineered allogeneic (allo) car t cells incorporating novel edits that increase potency and efficacy in the treatment of lymphoid and solid tumors. Cancer Res 83, 7_Suppl.

- Vertex Pharmaceuticals. 2024. Vertex Announces US FDA Approval of CASGEVY™ (exagamglogene autotemcel) for the Treatment of Transfusion-Dependent Beta Thalassemia. https://investors.vrtx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/vertex-announces-us-fda-approval-casgevytm-exagamglogene.

- Wang, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Nie, J.; Shen, L.; Jiang, P.; He, J.; Ye, X.; et al. Phase I study of CRISPR-engineered CAR-T cells with PD-1 inactivation in treating mesothelin-positive solid tumors.. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3038–3038. [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.; Yin, D.; Zhai, Z.; Ling, S.; Le, H.; Tian, L.; Xu, J.; Paludan, S.R.; Cai, Y.; Hong, J. In vivo CRISPR gene editing in patients with herpetic stromal keratitis. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 3163–3175. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Huang, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Xu, X.; Li, Y. Mechanisms of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity of CAR T-cell therapy and associated prevention and management strategies. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Xie, L.; Su, B.; Mou, D.; Wang, L.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; et al. CRISPR-Edited Stem Cells in a Patient with HIV and Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1240–1247. [CrossRef]

- Ishino, Y.; Krupovic, M.; Forterre, P. History of CRISPR-Cas from Encounter with a Mysterious Repeated Sequence to Genome Editing Technology. J. Bacteriol. 2018, 200, e00580-17. [CrossRef]

- Zetsche, B.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Slaymaker, I.M.; Makarova, K.S.; Essletzbichler, P.; Volz, S.E.; Joung, J.; van der Oost, J.; Regev, A.; et al. Cpf1 Is a Single RNA-Guided Endonuclease of a Class 2 CRISPR-Cas System. Cell 2015, 163, 759–771. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Cheng, Jun Liu, Jiang F Zhong, and Xi Zhang. 2017. Engineering car-t cells. Biomarker research 5(1), 22.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).