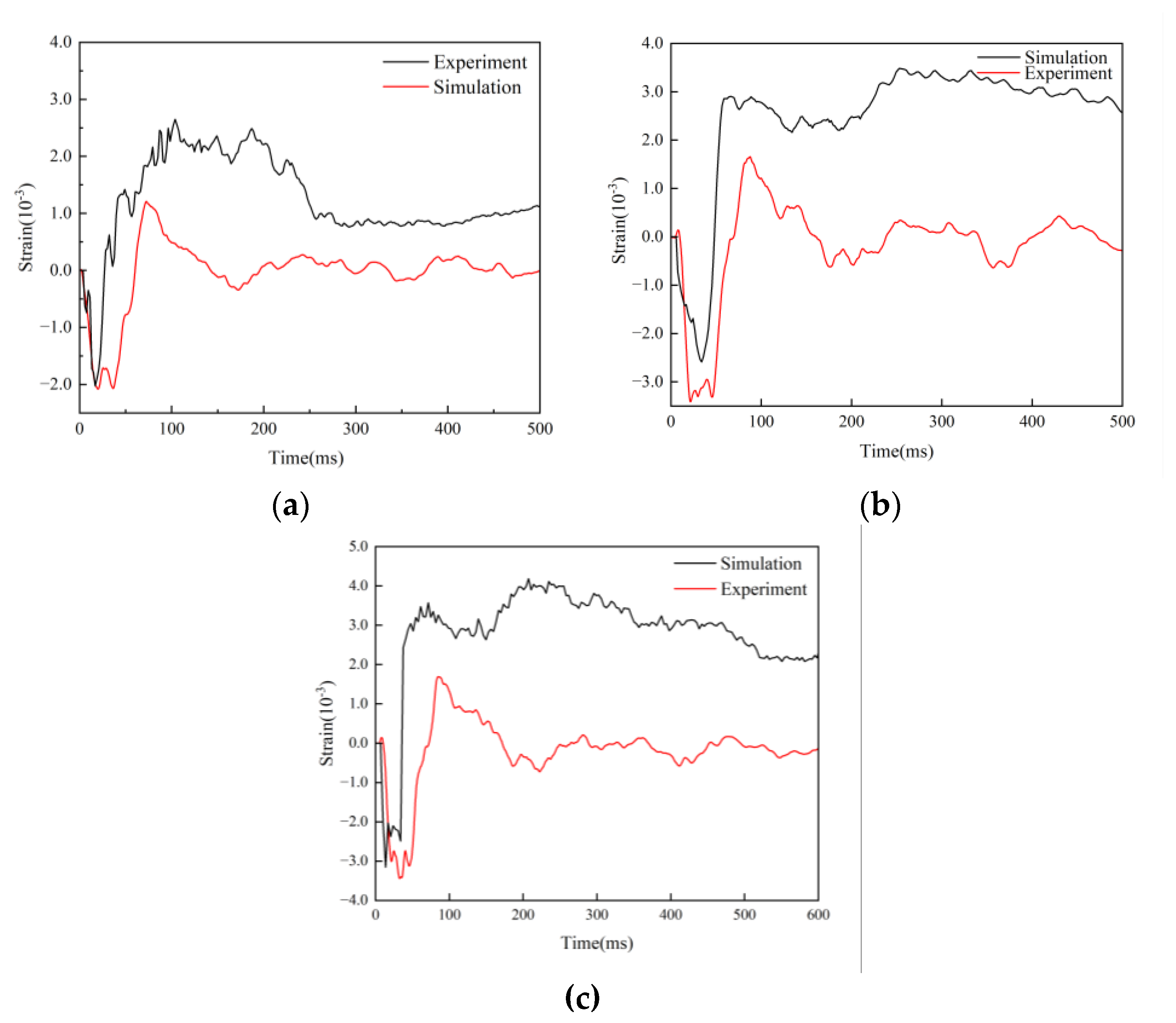

4.2. 115 g Bird Impacts Different Carbon Fiber Layering

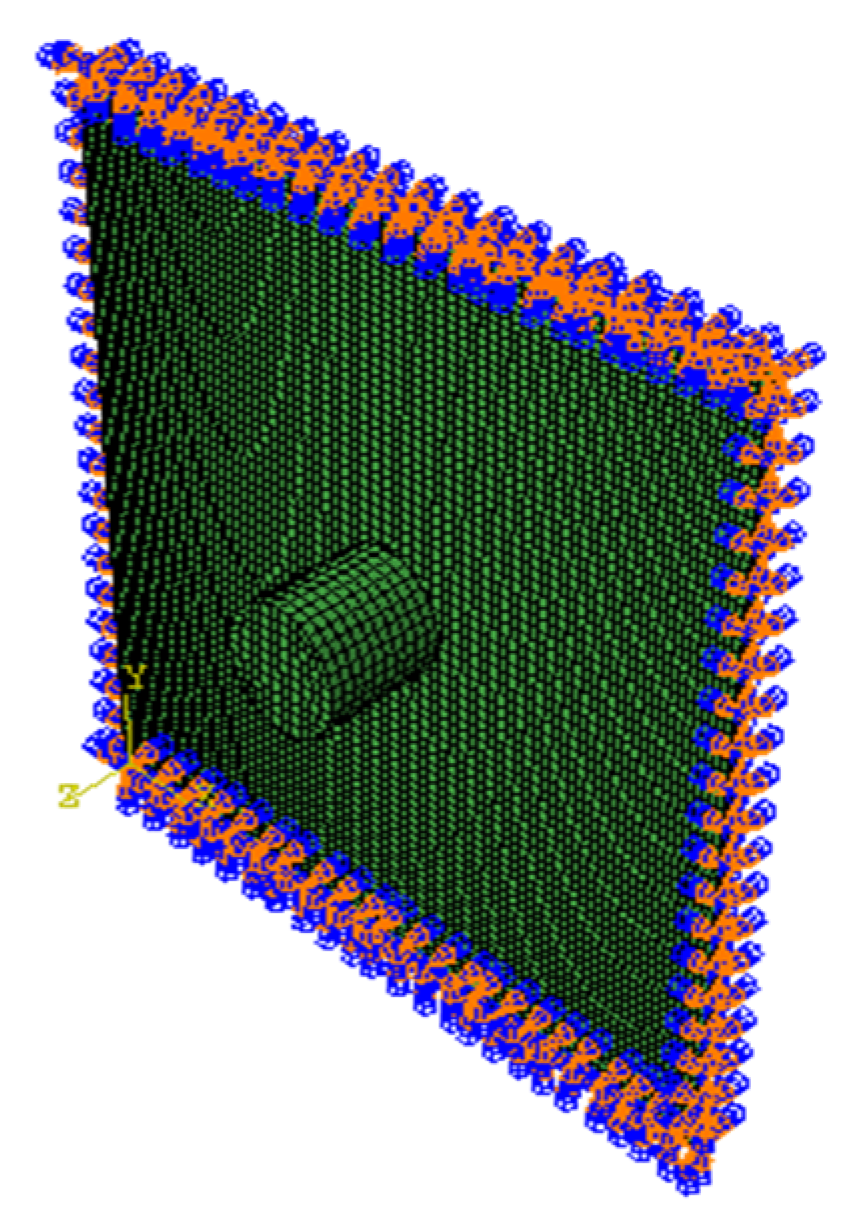

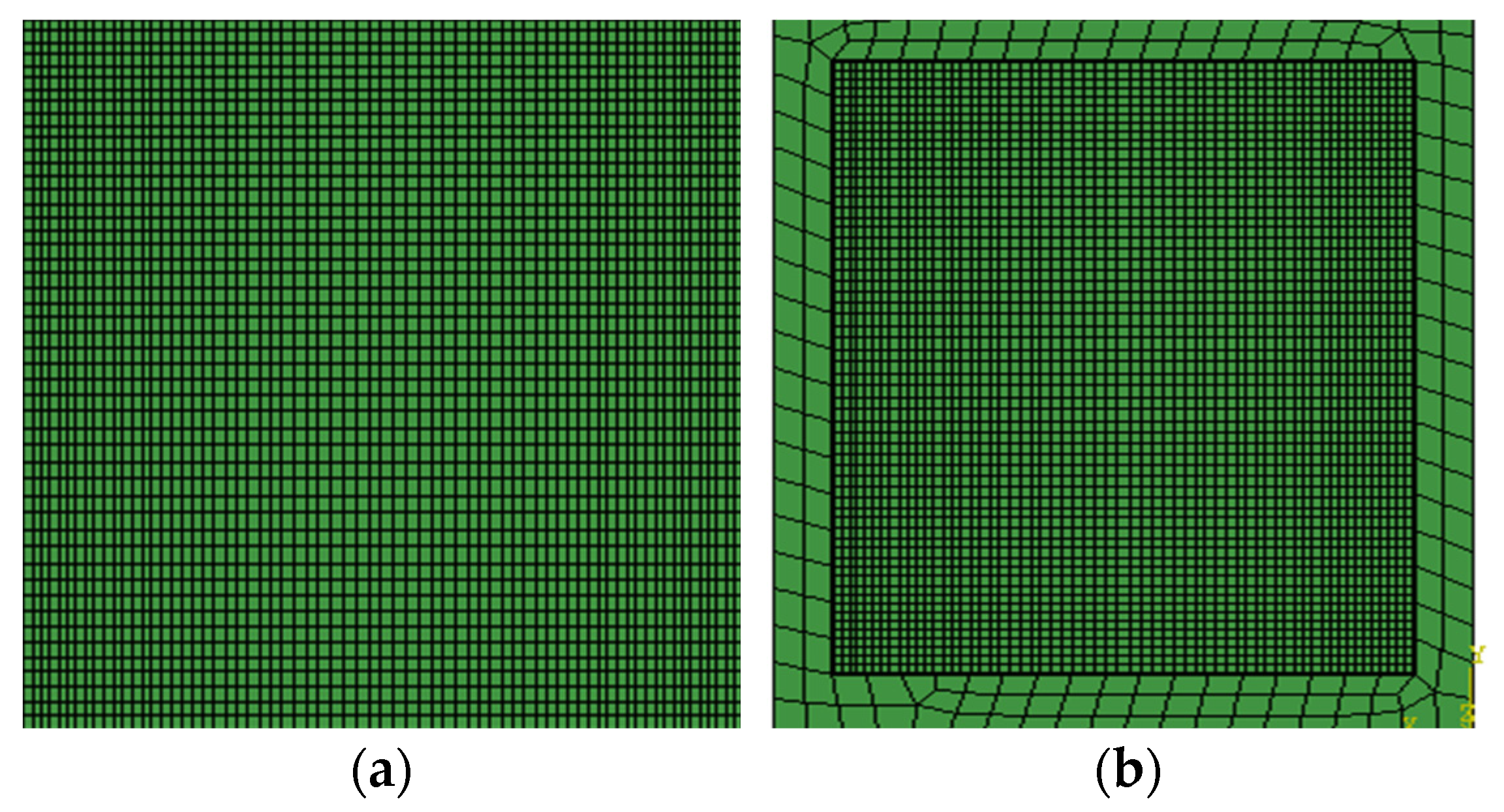

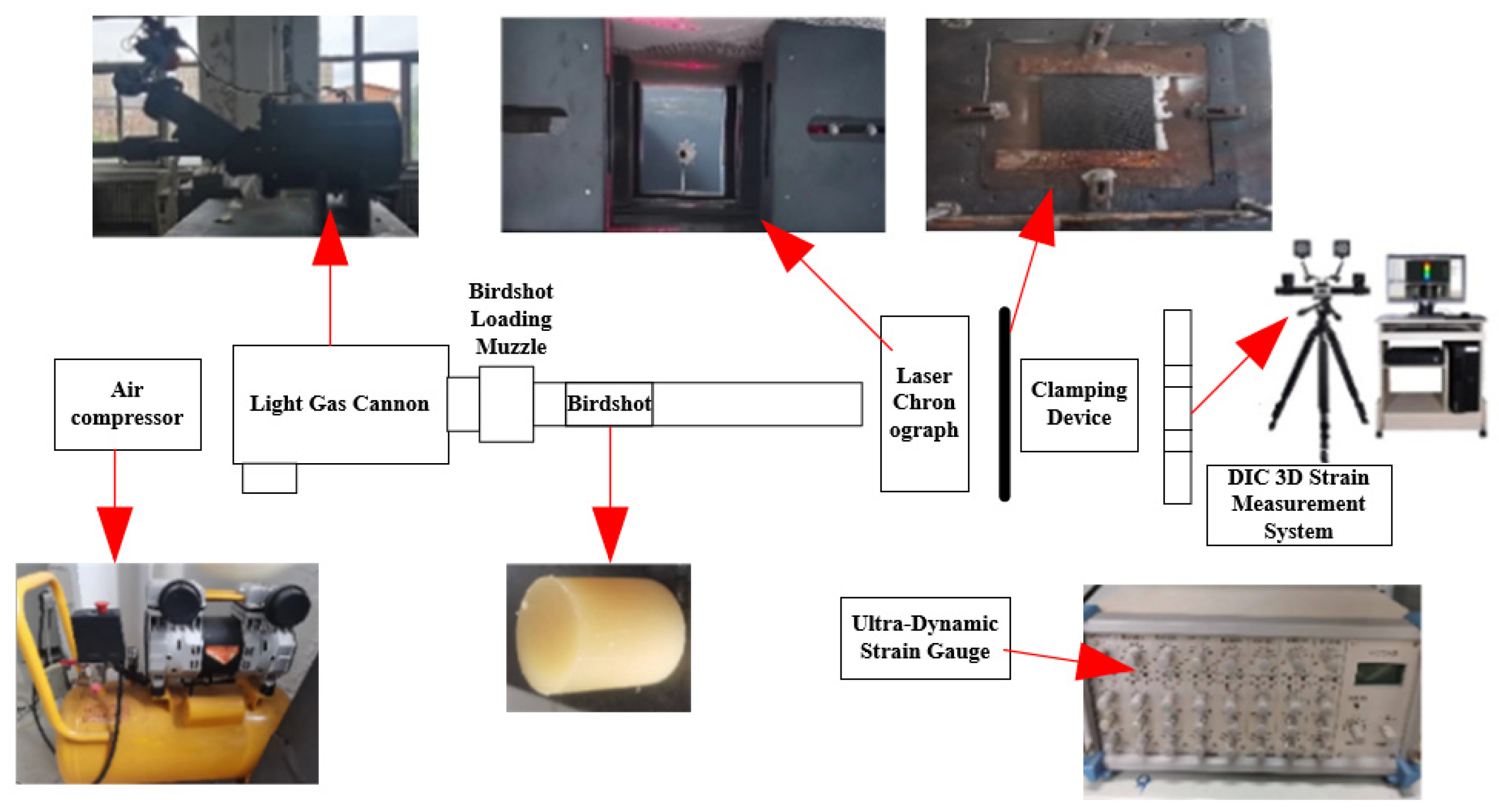

The mass of a 115g bird impact is employed to affect the carbon fiber laminate in these set of experiments, where the direction of layup is the variable. However, carbon fiber laminates are expensive and testing is too costly, this work uses the simulation method to model how various pavement layers may affect birds.

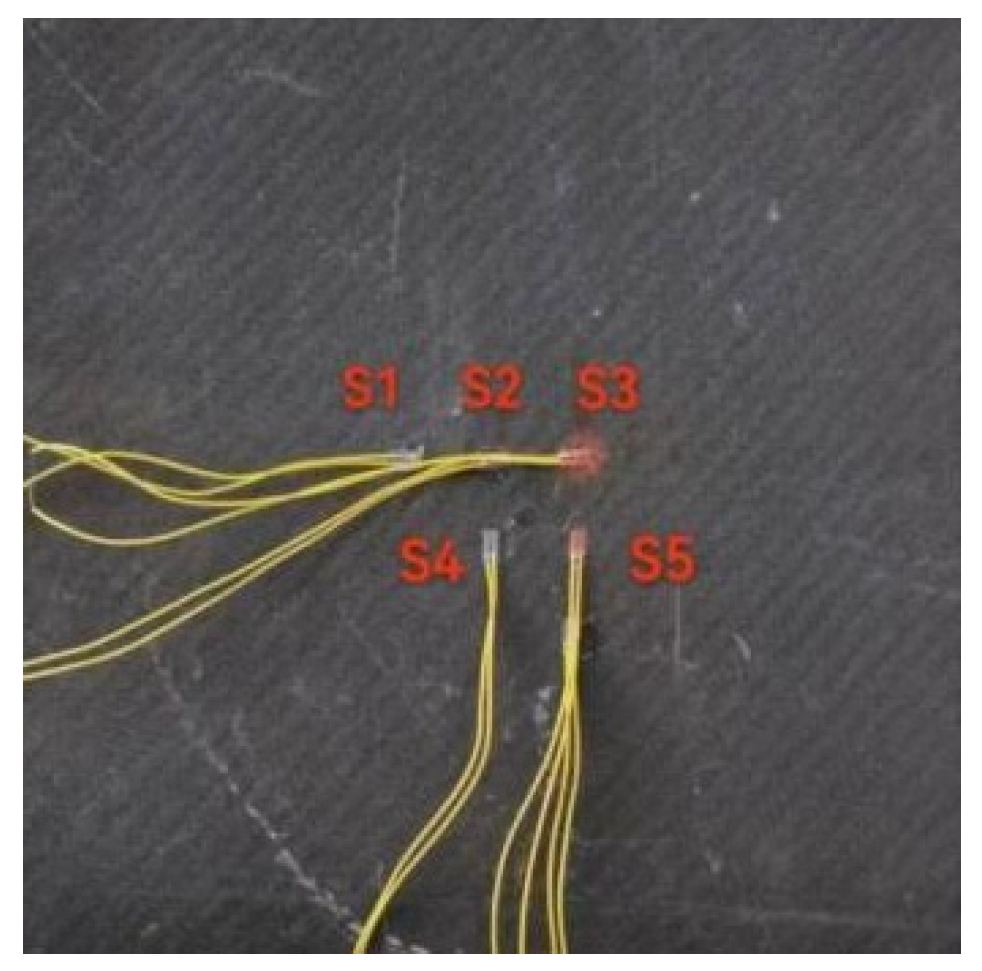

The strain (

Figure 9a), displacement (

Figure 9b), and stress (

Figure 9c) curves are displayed at the S3 point of the L1[45/-45/45/-45]2S layup, respectively, in

Figure 9. The S3 point is the impact's central location; the subsequent layup spots are chosen similarly. The impact velocities are 38m/s, 58m/s, 78m/s, 98m/s and 118m/s respectively. The strain is 0.39% and 0.83% at 38m/s and 58m/s, respectively. The stresses were 319.64MPa and 419.03MPa, respectively. The displacements were 5.63mm and 7.24mm, respectively. The strain changes to 1.94% at 78m/s. The stress is 487.93MPa; The displacement is 8.52mm. The slight delamination failure between the composite's layers is essentially insignificant when combined with the impact state of the 78m/s composite in

Figure 9d. The strain is 3.10% at 98m/s, and the stratification is more noticeable at 98m/s and 118m/s. The displacement is 9.97mm, and the stress is 523.40MPa. The displacement rises from 9.97mm of 98m/s to 10.97mm, the stress is 637.98MPa, and the maximum strain of 118m/s reaches 7.85%. It may be concluded that the L1 laminated carbon fiber sheet starts to experience delamination failure at 98m/s when combined with the impact shape of 98m/s in

Figure 9d.

The changes of strain, displacement and stress under L2[45/0/45/0]2S are shown in

Figure 10. The speed of strain mutation of L2 paving is 58m/s, and its strain reaches 3.90%(

Figure 10a), stress 309.88MPa(

Figure 10c), and displacement is 8.30mm(

Figure 10b). When paired with

Figure 9, it is evident that the displacement is 1.06mm greater than that of the L1 layer and the strain L2 at 58m/s is four times that of the L1 layer. When combined with

Figure 10d's impact form, it is evident that there is no discernible delamination at 58m/s. However, at 78m/s, 98m/s, and 118m/s, delamination failure is evident, and the corresponding stresses are 398.60MPa, 527.01MPa, and 619.40MPa (

Figure 10c). At 78m/s, the L2 layer began to fail at 78m/s. The strain was distributed rather uniformly between 4% and 5.5%(

Figure 10a).

The strain and displacement of L2 are compared with those of L1. The displacement of the 118m/s L2 layer is greater than that of L1, but the strain is smaller. Its stress exceeds the tensile strength of the matrix but does not exceed the tensile strength of the fibers, indicating that the matrix has failed. At other speeds, the displacement and strain under the L2 layer are both greater than those under the L1 layer, suggesting that this layer has a poorer ability to absorb impact energy compared to the L1 layer. The recovery speed from displacement also shows that the composite under the L2 layer recovers less well than under the L1 layer, further confirming that the L1 layer has better stiffness

The strain (

Figure 11a), displacement (

Figure 11b), and stress (

Figure 11c) change curves during L3[45/0/-45/90]2S layup are displayed in

Figure 11. When affected by the velocity of 78m/s, the strain of this layup abruptly changes; it is 4.21%, the displacement is 8.22mm, and the stress is 586.7MPa. If the displacement is 0.08mm less than that of the L1 layer, it can be disregarded, and the strain is more than twice that of the L1 layer at 78m/s. However, the stress of L1 paving is lower, and when paired with the impact state

Figure 11d and

Figure 9d, it is evident that the two pavement layers' delamination failure at 78m/s is negligible and may be disregarded. L3 layering failure is more obvious at 98m/s, 118m/s layering. Nearly all of the plate is layered in the middle position, and the degree of delamination failure is greater than that of L1 layering. While the displacement of L3 layering is 10.9mm and the displacement of L3 layering is 118m/s, the stress under L3 layering is 674.5MPa, making it more susceptible to fiber fracture and other failure forms. It demonstrates that the L1 fiber layering technique has superior impact energy absorption and superior substrate and matrix stress and strain energy transfer. Furthermore, the carbon fiber layer and substrate beneath the L1 layer are better bonded and that lamination failure is difficult to achieve.

The strain (

Figure 12a), displacement (

Figure 12b), and stress (

Figure 12c) change curves under L4[0/90/0/90]2S layup are displayed in

Figure 12. At 78m/s, the layup strain abruptly changes, reaching 4.21%, with a displacement of 9.25mm and a stress of 527.6MPa. In comparison to the L1 layer, the strain is doubled, the displacement is 0.75mm greater, and the stress is 41.6MPa greater. The laminates exhibit noticeable delamination at 78m/s when combined with the impact condition, as seen in

Figure 8d, and the delamination failure degree of L4 is higher. With maximum strains of 5.60% and 5.71%, maximum displacements of 10.7mm and 12.06mm, and maximum stresses of 723.88MPa and 810.59MPa, respectively, the delamination failure of L4 is exacerbated at 98m/s and 118m/s. L4 should vary little at 118m/s, yet the stress and displacement are greater than those of L1, according to a comparison of L4's strain, displacement, and stress.L1 pavement has a lower failure degree than L4 when strain, stress, and delamination conditions of 78m/s and 98m/s are taken into account.

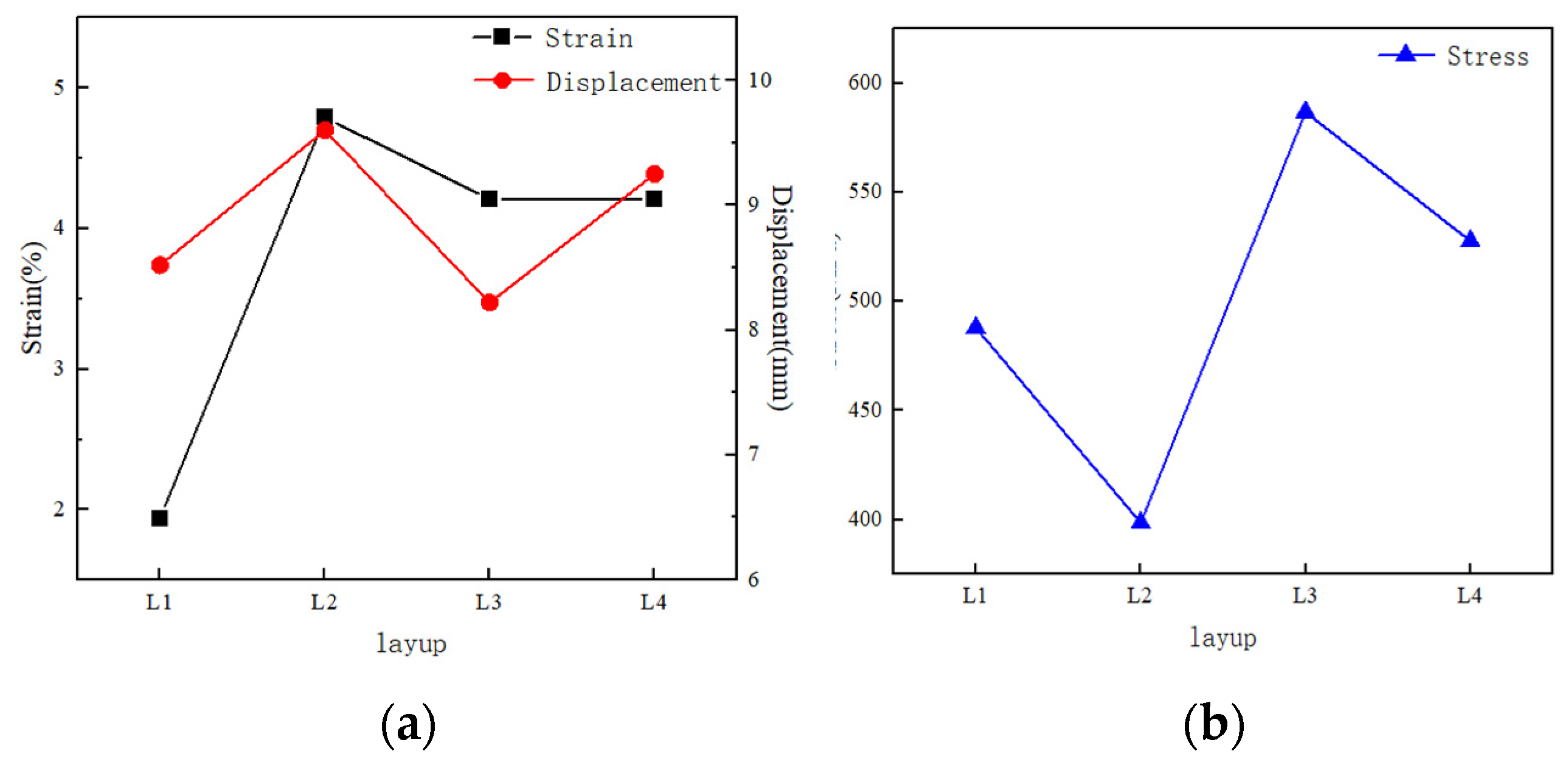

Based on the examination of the four data sets mentioned above, it can be inferred that the failure speed is essentially 78m/s, with the L1 layer's layup failure being the only one that is 98m/s. The four layup groups' maximum stress, strain, and displacement of 78m/s are contrasted. Of the four bedding groups, L2 bedding has the least amount of stress and the greatest strain and displacement. The stratification is rather clear, as evidenced by the 78m/s impact form of L2 in

Figure 10d. Although L4 pavement's layered impact morphology is also evident, as seen in

Figure 12d, its peak strain and displacement rank second out of the four paving groups, and its stress is comparatively low. The strain and displacement of L1 and L3 bedding are less than those of the other two groups, as shown by the fluctuation trend in

Figure 13a. However, stress

Figure 13b shows the opposite pattern of change. Given that the 78m/s impact state diagram in

Figure 9d and

Figure 11d shows a very small degree of delamination failure, it can be inferred that the carbon fiber composite's failure state is correlated with the values of strain and displacement. From good to bad, the four paving groups can be ranked as follows: L1, L3, L4, and L2.

4.3. Influence of Different Impact Angles on Bird Impact

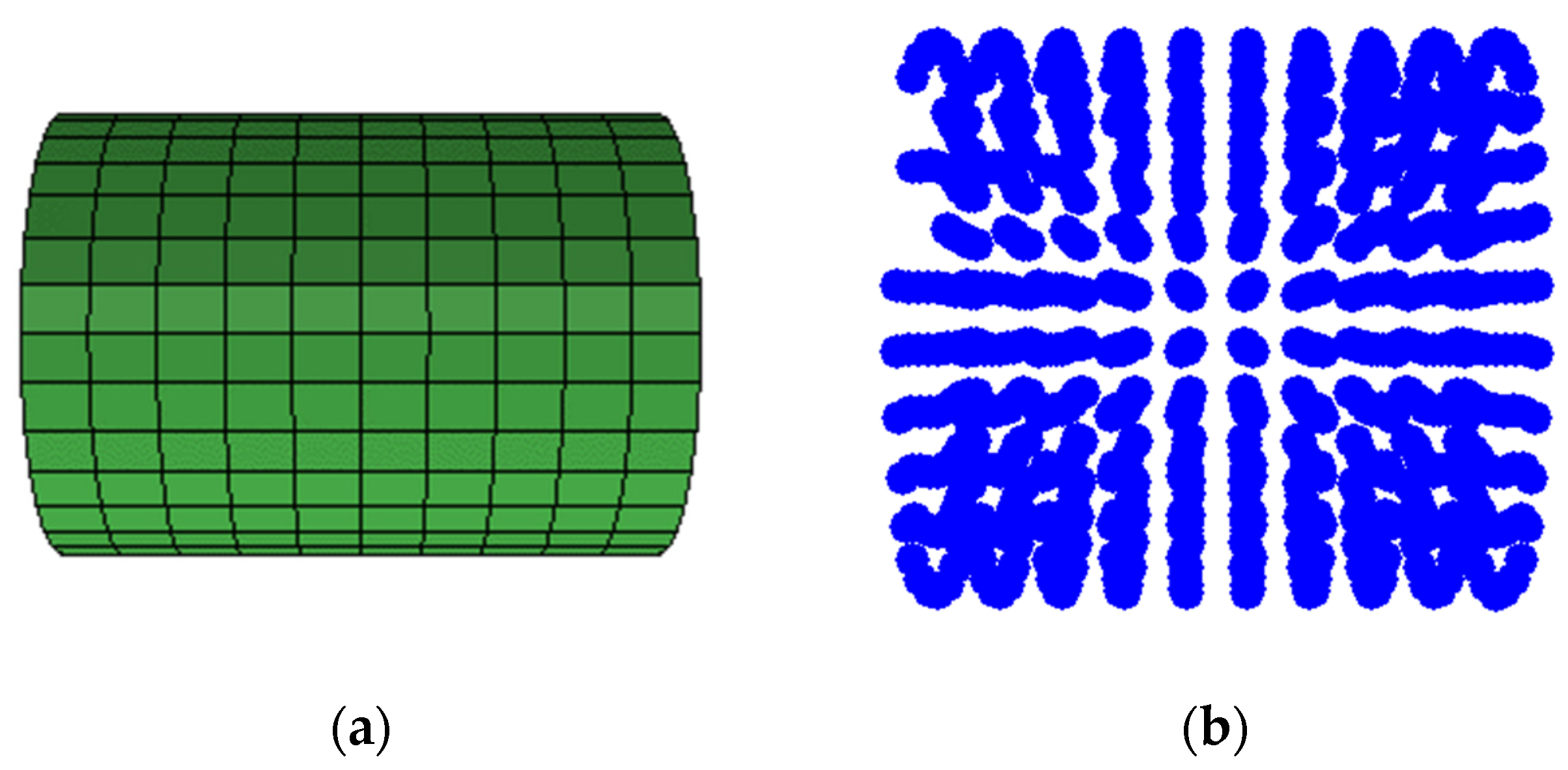

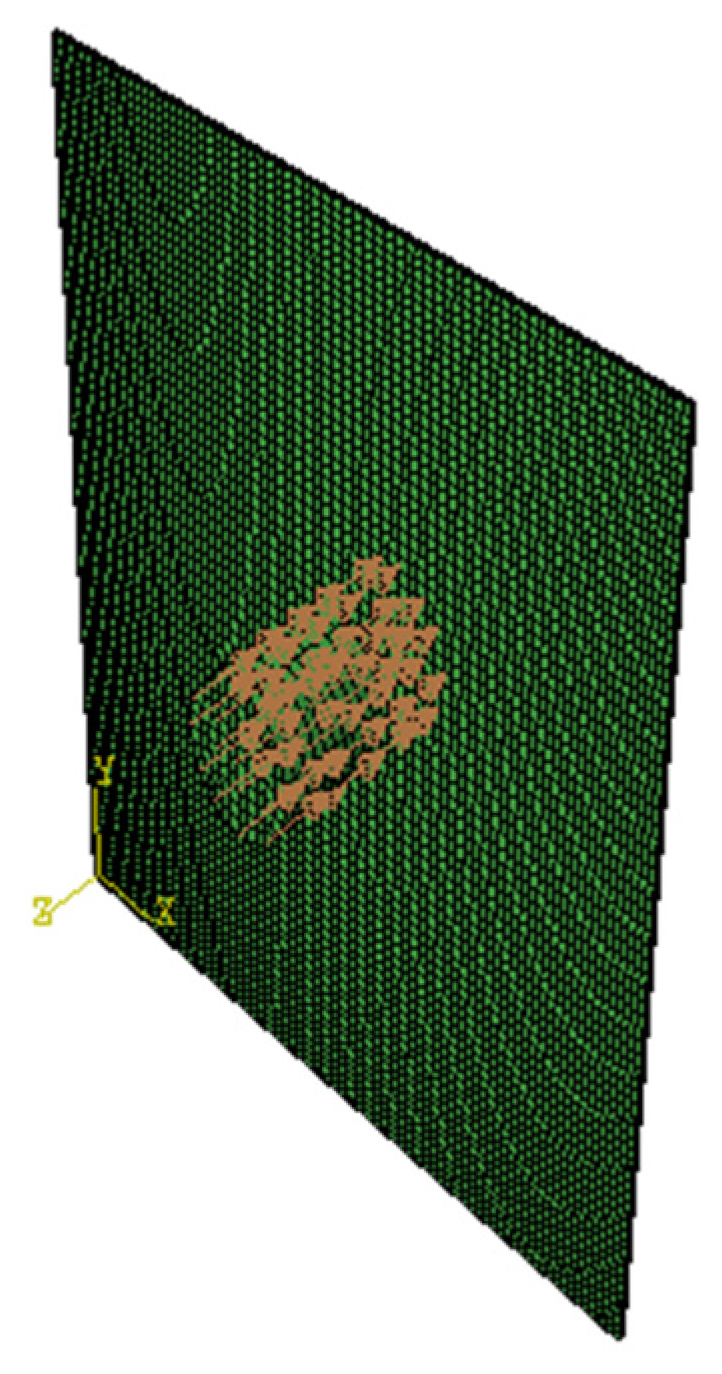

The purpose of the simulation is to examine how various paving layers react dynamically to bird impacts from various perspectives. This study examines which layering sequence performs better against bird impacts when many layering sequences are affected by the same angle. Determine the best layup for impact at various angles.

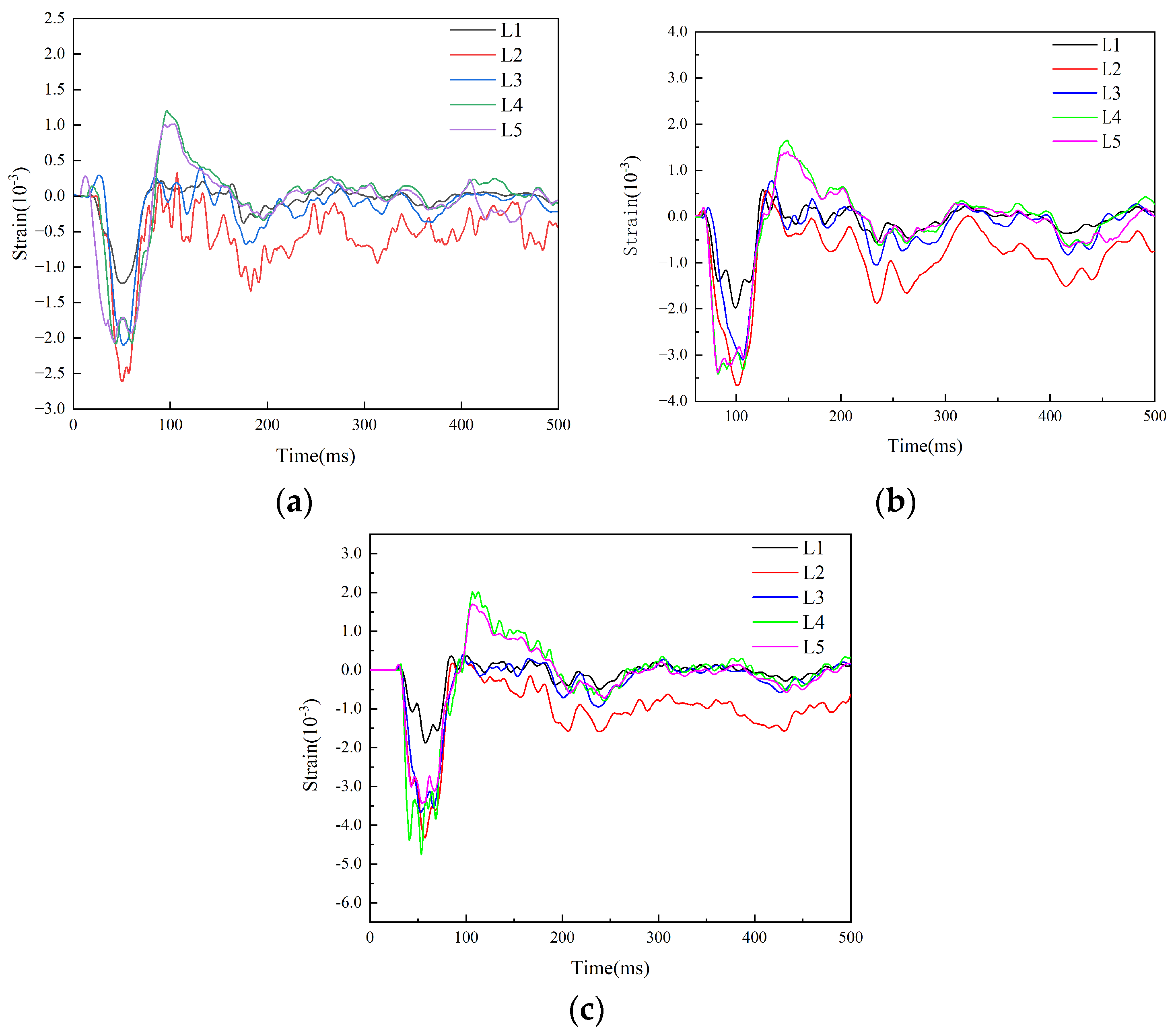

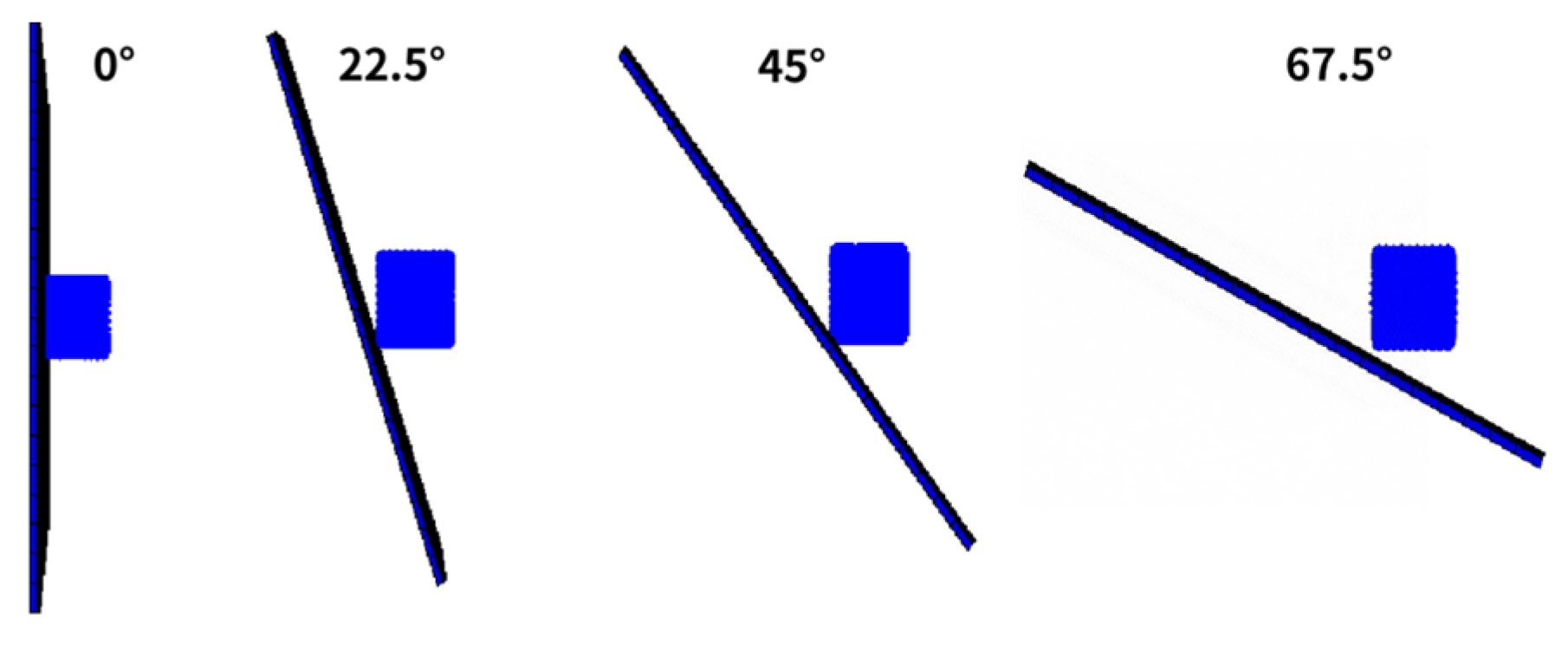

This section examines the dynamic response of carbon fiber composite laminates to a 115g gelatin birdshot impact at an impact velocity of 78 m/s.

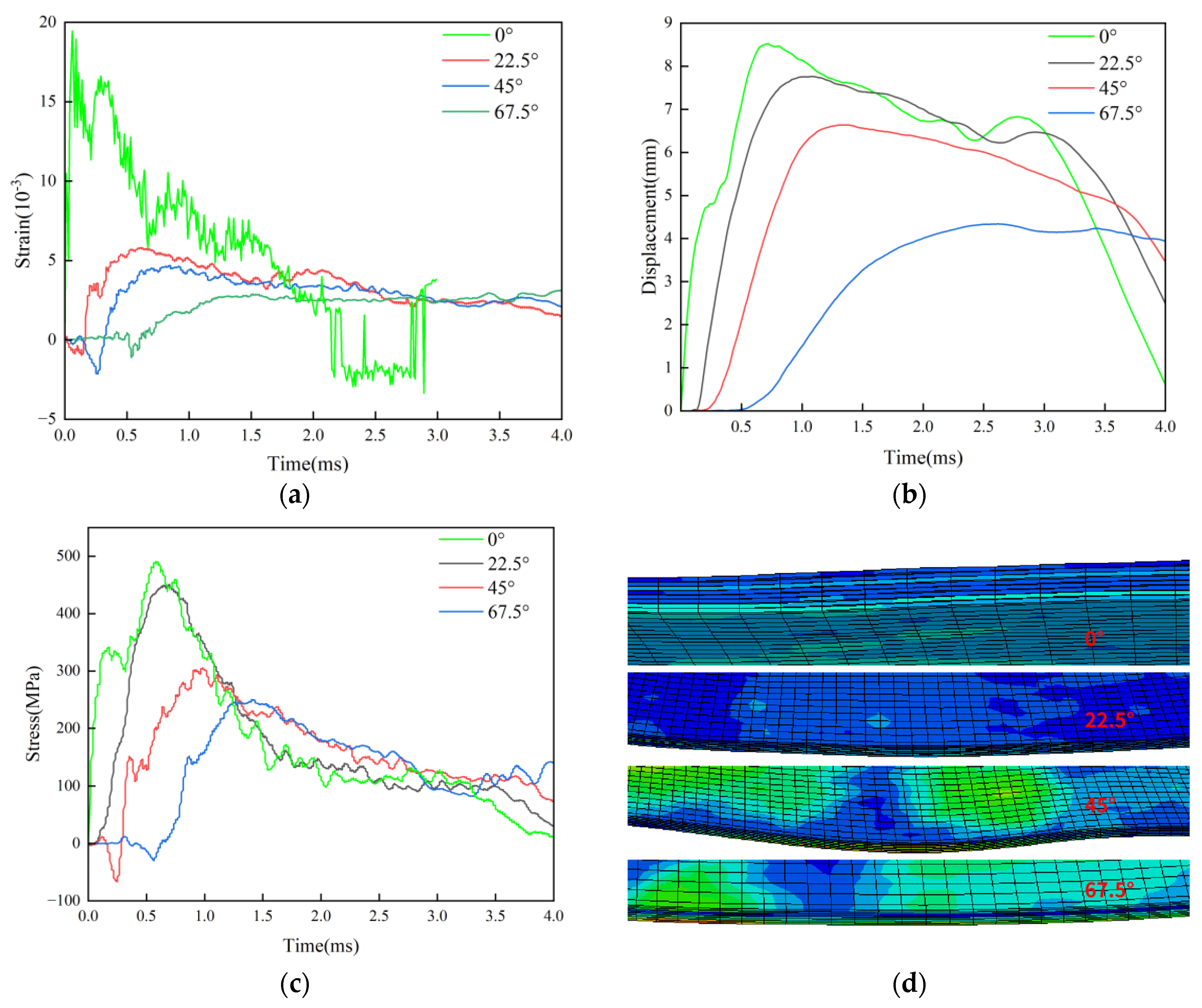

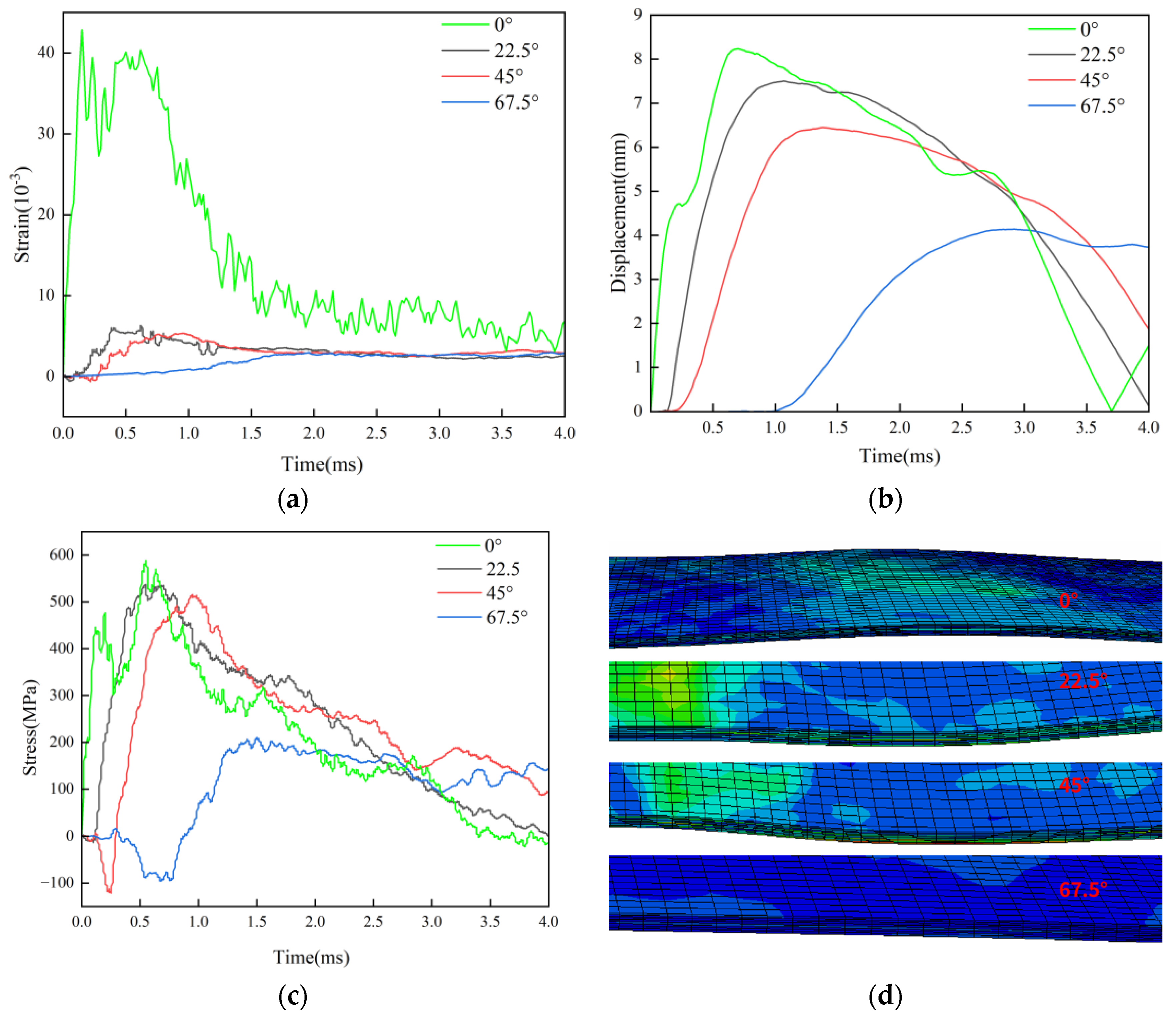

Figure 14 illustrates the varied angles at which carbon fiber composite laminates and birdshot laminates are created. Since the laminates' normal vector is 0°, four angles are set: 0°, 22.5°, 45°, and 67.5°. At various impact angles of 0°, 22.5°, 45°, and 67.5°, the strain, displacement, and stress curves of L1[45/-45/45/-45]2S pavement impacting the carbon fiber laminates are displayed in

Figure 15. The S3 point is the impact's central location. After simulating all the layers being struck at several speeds, it was determined that nearly all of the layers were unable to stratify at 78m/s when struck by a 115g bird. It is evident from strain curve

Figure 15a that the maximum strain is produced when the normal vector is at 0°. The highest impact strain for 22.5°, 45°, and 67.5° is 0.57%. The highest tensile strain for L1 paving group are: 1.94% at 0°, 0.57% at 22.5°, 0.46% at 45° and 0.29% at 67.5°.

Figure 15b displays the displacement change curve under impact at each angle. When the laminate is oriented normally, the maximum displacement of birdshot impact at 0° is 8.52mm; at 22.5°, it is 7.75mm; at 45°, it is 6.63mm; and at 67.5°, it is 4.33mm. The stress change curve is displayed in

Figure 15c, where the displacement of 67.5° is 247.28MPa, the stress at 0° is 490.54MPa, the stress at 22.5° is 450.91MPa, and the stress at 45° is 305.89MPa. According to

Figure 15d of impact morphology at all angles, there is no obvious delamination failure or fiber fracture failure at all angles, indicating that L1 layering failure is not significantly related to Angle.

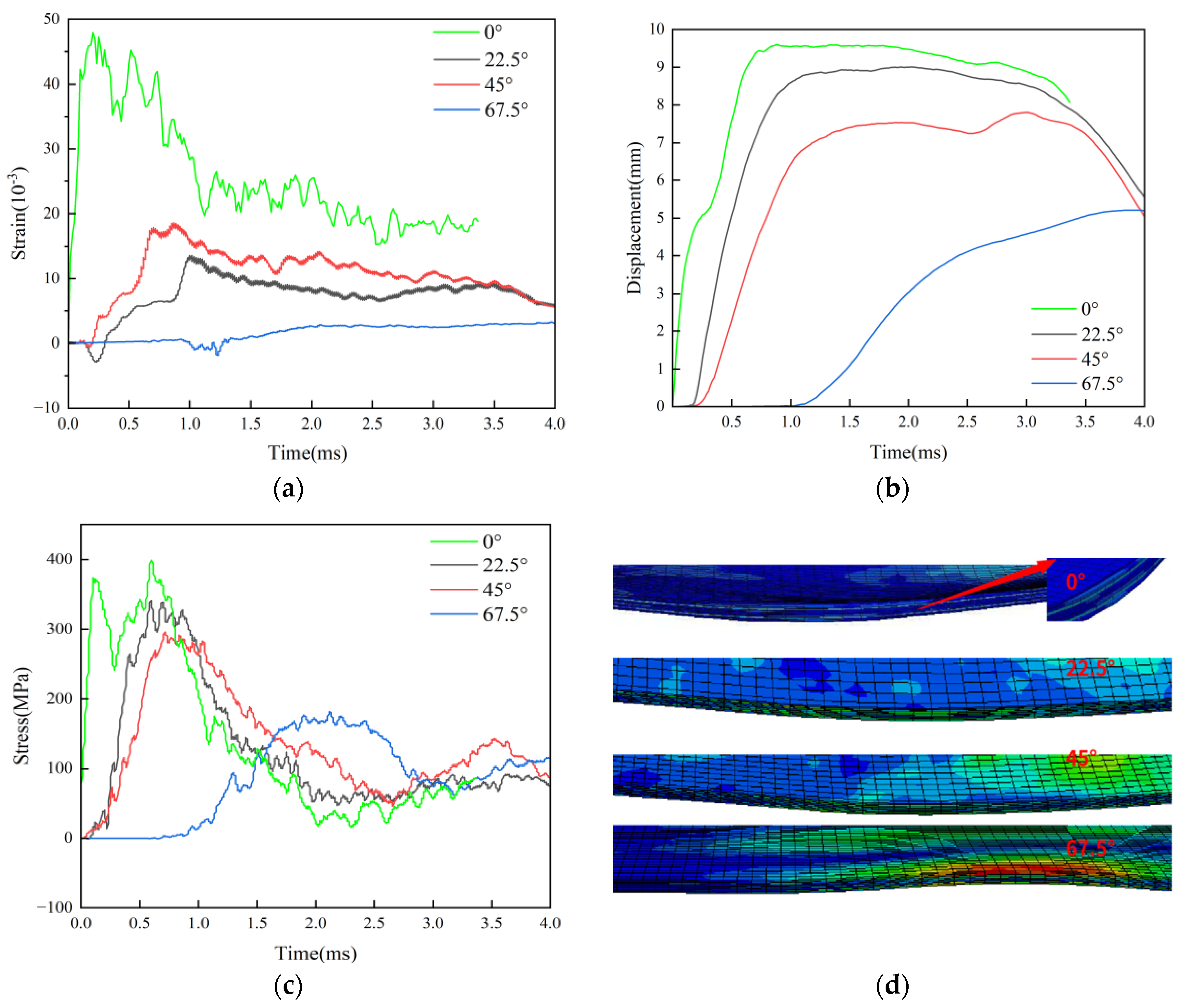

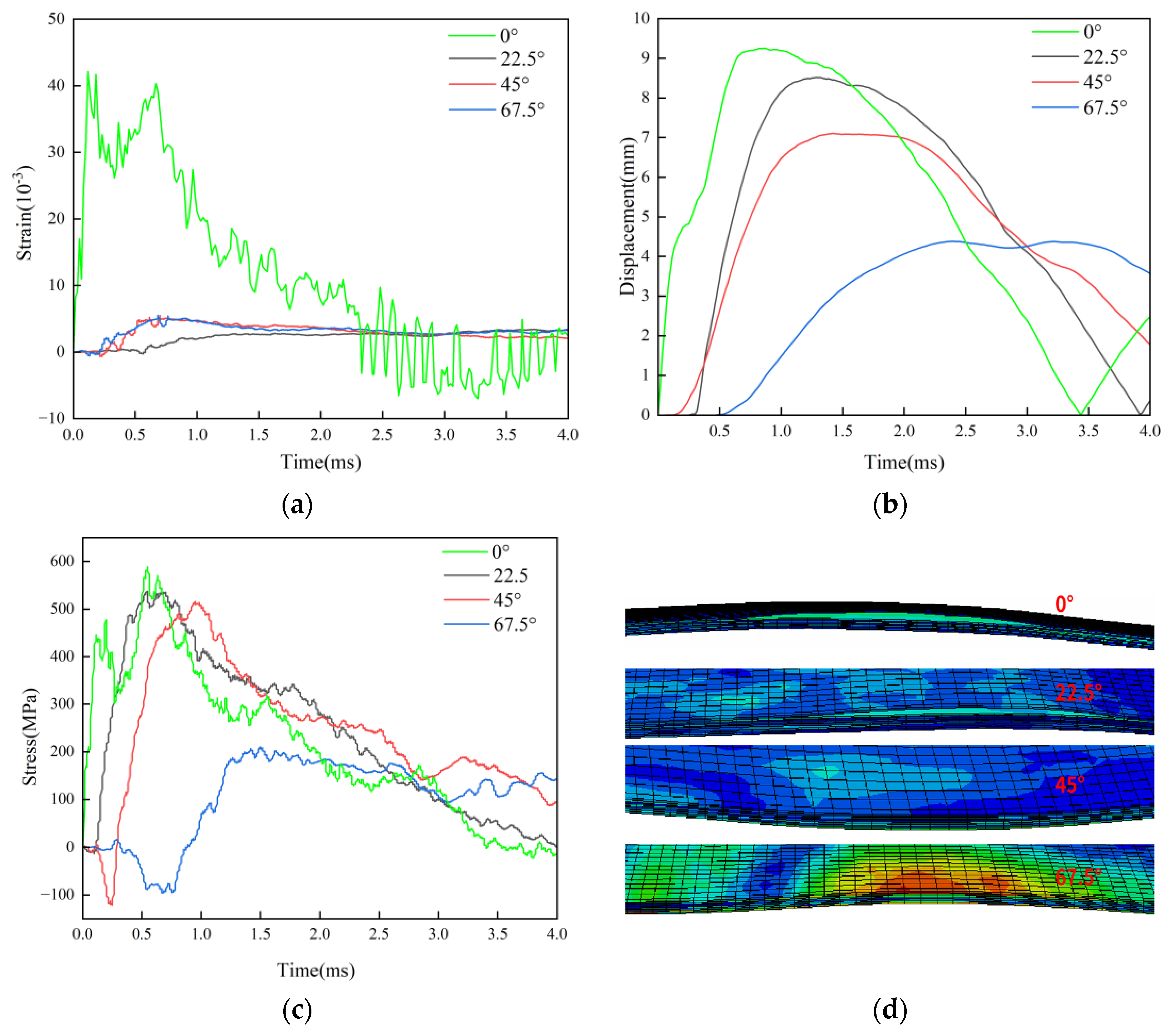

L2[45/0/45/0]2S layer-strain curve

Figure 16a shows that the strain caused by bird is greatest at 0° with the normal vector and gradually diminishes with the oblique angle. As the impact angle increases, the displacement (

Figure 16b) likewise reduces; however, at 67.5°, the change in displacement rapidly diminishes. At 0°, 22.5°, and 45°, the maximum stress (

Figure 16c) varies minimally, but at 67.5°, it rapidly drops. The strain associated with each angle of the L2 paving group is as follows: the maximum tensile strain at 0°, 22.5°, 45° and 67.5° angles is 4.79%, 1.86%, 1.35% and 0.46%.

Figure 16b displays the displacement change curve under impact at each angle. Maximum displacement of birdshot impact at 0° with the laminate's normal direction is 9.59 mm; at 22.5°, it is 8.92mm; at 45°, it is 7.80 mm; and at 67.5°, it is 5.21 mm. The stress change curve is displayed in

Figure 16c, where the displacement of 67.5° is 208.53MPa, the stress corresponding to 0° is 398.18MPa, the stress corresponding to 22.5° is 340.71MPa, and the stress corresponding to 45° is 295.85MPa. Delamination failure in the L2 layer occurs at 0° impact when combined with the impact morphology of

Figure 16d. However, at 22.5°, 45°, and 67.5° angles, the impact delamination failure vanishes, suggesting that the impact damage of carbon fiber composite impact laminates is minimized at these angles. It also demonstrates how the angle of the birdshot and composite laminates affects the extent of impact damage.

The strain caused by bird is greatest at 0° with the normal vector, as shown by L3[45/0/-45/90]2S layer-strain curve 17a, and the inclined strain rapidly declines with the angle. The displacement (

Figure 17b) also decreases as the impact Angle increases. However, when the impact angle is 67.5°, the displacement rapidly reduces, and the impact at other angles barely affects the displacement. At 0°, 22.5°, and 45°, the maximum stress (

Figure 17c) barely changes, but at 67.5°, it rapidly drops, and a fairly noticeable negative stress also manifests. The strain associated with each angle of the L3 paving group is as follows: the maximum tensile strain at 0°, 22.5°, and 45° angles is 4.28%, 0.62%, and 0.53%, respectively. At a 67.5° angle, the maximum tensile strain is 0.28%.

Figure 17b displays the displacement change curve under impact at each angle. With the laminates oriented normally, the maximum displacement of birdshot impact at 0° is 8.23mm; at 22.5°, it is 7.49mm; at 45°, it is 6.43mm; and at 67.5°, it is 4.12mm.

Figure 17c displays the stress change curve. The stress at 0° is 588.71MPa, the stress at 22.5° is 537.17MPa, the stress at 45° is 512.34MPa, and the displacement at 67.5° is 181.23MPa. When combined with the impact morphology shown in

Figure 17d, it is evident that the four sets of angles under the L3 paving layer do not cause any discernible delamination failure or other failure modes.

The strain produced by bird is greatest when it forms 0° with the normal vector, and the inclined strain rapidly declines with the angle, according to the L4[0/90/0/90]2S lay-up strain curve

Figure 18a. However, the strain curves at 22.5° and 45° have a greater degree of overlap. As the impact angle increases, the displacement (

Figure 18b) likewise reduces, and it is nearly equal at 22.5° and 67.5°. At 0°, 22.5°, and 45°, the maximum stress (

Figure 18c) varies slightly; however, at 67.5°, it rapidly declines, and the coincidence degree of the stress curve at 22.5° and 45° is higher. The maximum tensile strain for the L4 pavement group is 4.21% when struck at 0°, 0.55% when struck at 22.5°, and 0.55% when struck at 45°.

These strains correspond to each of the following angles. At a 67.5° angle, the maximum tensile strain is 0.33%. The displacement change curve under impact at each Angle is shown in

Figure 14b1. The maximum displacement of bird impact at 0° with the normal direction of the laminates is 9.25mm; the maximum displacement of bird impact at 22.5° is 8.50mm; the maximum displacement of birdshot impact at 45° is 7.10mm; and the maximum displacement of birdshot impact at 67.5° is 4.33mm.

Figure 18c displays the stress change curve. The displacement of 67.5° is 238.87MPa, the stress corresponding to 0° is 654.76MPa, the stress corresponding to 22.5° is 570.27MPa, and the stress corresponding to 45° is 549.37MPa. The carbon fiber composite laminates exhibit varying degrees of delamination failure under impact of 0° and 22.5° when combined with the impact state shown in

Figure 18d. The layer and plate of L4 layering have the weakest impact resistance, and it is the only group that experiences delamination failure under the impact of bird at 22.5°. This is demonstrated by the fact that no delamination failure occurred in the four groups of Angle impact morphology

Figure 18 22.5° combined with the three groups of layering mentioned above.

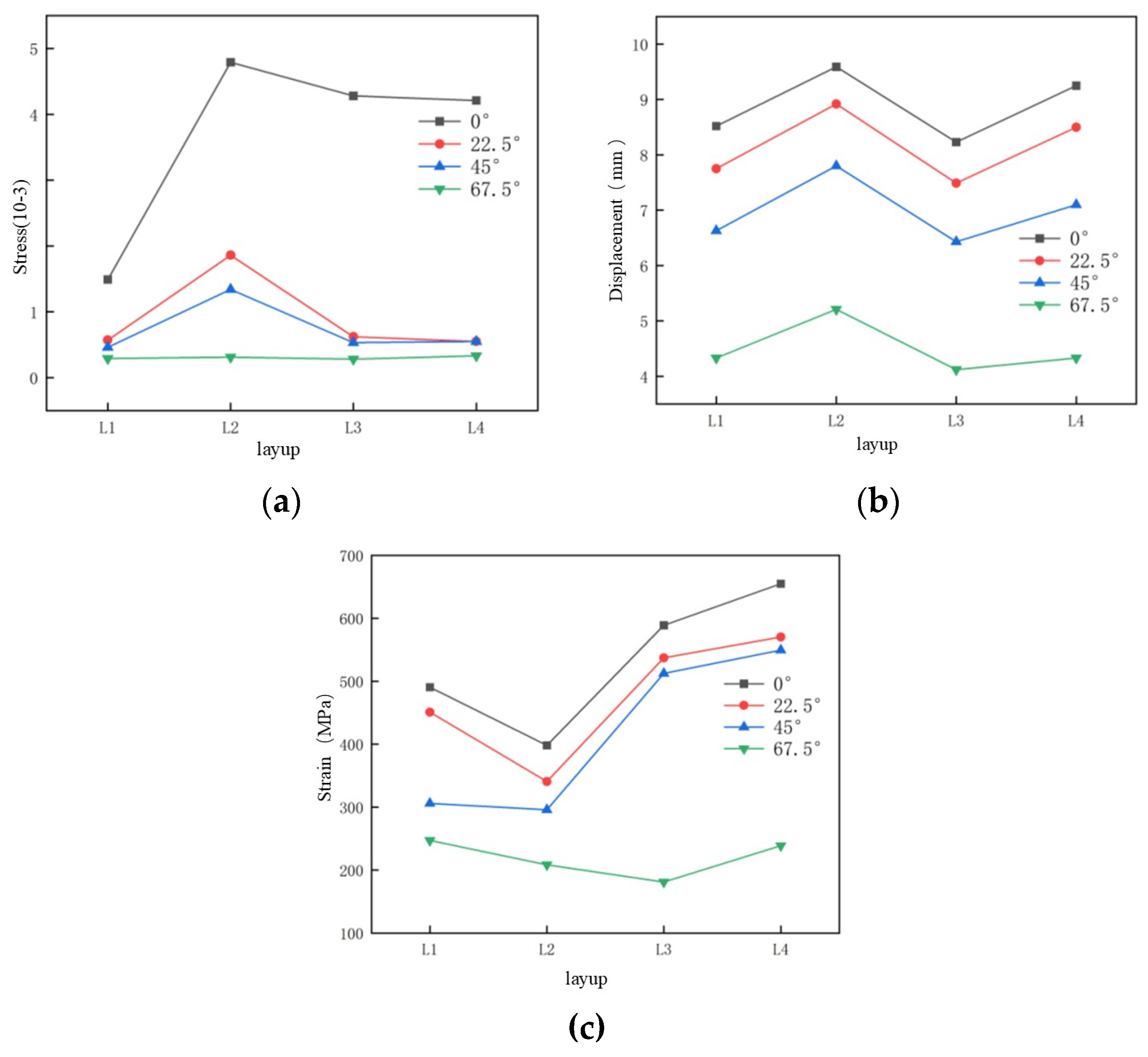

The displacement, strain, and stress are essentially the maximum values of 0° with the normal direction of the composite material, according to the analysis of the four sets of data above. The maximum strain values of four sets of distinct bedding layers affected by birdshot at various angles are displayed in

Figure 19a.

Figure 19a shows that the peak value of strain is greatly impacted by changes in the impact angle, with the L1 bedding strain being the only one that is least impacted. The other three bedding layers are all susceptible to changes in the impact angle. It is evident from the displacement (

Figure 19b) that the displacement evenly diminishes as the impact angle increases. The maximum displacement decreases dramatically around 67.5°, whereas the displacement reduction of the four groups of distinct pavement layers is quite close. L1 and L3 paving have superior anti-bird impact performance because their displacement is less than that of L2 and L4. Angle affects the stress beneath the four paving layers (

Figure 19c). At 45° and 67.5°, the stress of the L1 paving layer dramatically drops, but the stress of the L2 paving layer remains rather constant with angle. At 0°, 22.5°, and 45°, the stress values of the L3 and L4 pavement layers are larger, and at 67.5° impact angle, the stress decreases off significantly. L1 pavement offers the best impact resistance, according to the data above.