1. Introduction

The Fisher information matrix of a regular parametric family of probability distributions induces a natural Riemannian structure on the parameter space [

1,

2,

3]. This structure provides the foundation for the intrinsic analysis of statistical estimation, see [

4,

5] and, beyond statistics, it has also been shown to reveal connections with physical laws [

6].

In this intrinsic framework, estimators are assessed through tools that do not depend on any particular parametrization of the model. Consequently, non-intrinsic criteria such as the squared error loss should be replaced by intrinsic measures. A natural choice is the squared Riemannian (Rao) distance, which serves as an intrinsic loss function. The associated risk can behave very differently from that based on squared error loss, especially in small-sample regimes. Similarly, the classical definition of bias must be reformulated in terms of a vector field determined by the geometry of the model, whose squared norm provides a natural intrinsic bias measure.

The estimator itself should also be intrinsic, i.e., independent of parametrization. Consider, for instance, the exponential distribution under two parametrizations,

where

is the positive real numbers indicator. The UMVU estimator computed under each parametrization

and

are not related by

. This apparent inconsistency arises because UMVU estimators rely on non-intrinsic notions such as unbiasedness and variance. As a result, the UMVU estimator is parametrization-dependent and cannot be regarded as intrinsically defined.

When the statistical model is invariant under the action of a transformation group on the sample space, it is natural to restrict attention to equivariant estimators, i.e., estimators

U satisfying

where

is the transformation group acting on the space of all samples of size

n and

is the induced transformation on the parameter space

. This restriction ensures logical consistency: only equivariant estimators remain coherent under data transformations. It is therefore a requirement that should be imposed prior to any attempt to minimize an intrinsic risk function.

As an illustration, consider the estimation of the unconstrained mean

of a

p–variate normal distribution. The MLE of

(which really defines and intrinsic estimator) based on a sample of size

n, is just the sample mean vector

. However, for

, the James–Stein estimator is known to have smaller quadratic risk [

7]. In our view, this does not undermine the MLE. Although the James–Stein estimator enjoys a lower risk under the non-intrinsic quadratic loss, it lacks the essential property of equivariance, which is crucial from the intrinsic perspective.

In this work we focus on classical statistical estimation, as is standard in the absence of prior knowledge. Nonetheless, intrinsic Bayesian approaches based on non-informative priors are also possible [

5,

8], and represent an interesting avenue for future research. Here, we adopt the squared Rao distance as a natural loss function, since it is the conceptually simplest intrinsic analogue of the quadratic loss, despite potential computational challenges. For a broader background on statistical estimation and its intrinsic developments, see [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Specifically, we consider the univariate linear normal model with a fixed design matrix. First, we explicitly characterize the class of equivariant estimators under the action of a suitable subgroup of the affine group–namely, those affine transformations of the data that leave the column space of the design matrix unchanged. This subgroup is the largest one that preserves the model’s structure. Next, we prove the existence and uniqueness of the estimator within this class that minimizes intrinsic risk, i.e., the equivariant estimator that minimizes the mean squared Rao distance. We also derive an explicit expression for the intrinsic bias of any equivariant estimator.

Furthermore, we compare the intrinsic bias and risk of the proposed estimator with those of the MLE, highlighting their differences in small samples and showing how these differences diminish as the sample size grows. Finally, we propose a computable approximation of the optimal estimator, which mitigates most of the intrinsic bias and risk issues that affect the MLE in finite samples.

2. Equivariant estimators for linear models

Let us consider the univariate linear normal model,

where

is a

random vector,

is a

matrix of known constants with

,

is a

vector of unknown parameters to be estimated and

is the fluctuation or error of

about

. We assume that the errors are unbiased, independent, with the same variance

and following a

n–variate normal distribution, that is

, where

is the

identity matrix. Therefore

distributes according to an element of the parametric family of probability distributions

with parameter space

, a

– dimensional simply connected real manifold. Hereafter, we shall identify the elements of

with

column vectors, when necessary.

Denote by

where

E is a subspace of

and

is the group of

orthogonal matrices with entries from

. Define

F as the subspace of

spanned by the columns of

, that is

. Observe that

,

,

and if

then

. Moreover, every

induces, in

F and

, two isomorphisms isomorphisms preserving the Euclidean norm in each subspace.

is invariant under the action of the subgroup of the affine group in

given by the family of transformations

where

.

Observe that

induces an action on the parameter space

given by

where this result is obtained taking into account that

is the projection matrix into

F and thus, if

there exists a unique

such that

and

.

Since the family is invariant under the action of , it is natural to restrict our attention to the class of equivariant estimators of i.e. an estimator satisfying for all .

Proposition 1.

Let be an equivariant estimator of . Then belongs to the family where,

Proof. Let

. The equivariance condition for

involves,

for any

.

Any

can be written in a unique form as

where

and

. Specifically

If we choose

in the previous expressions, we obtain

First we focus on

. If we let

, we have

with

Now observe that (

5) is satisfied for any

and

in

, in particular for

and

. Therefore

But

which leads to

Next, we consider

. Let

and

in (), it follows

Accordingly, it is enough to determine

on

. Let us take a unit vector

such that

. Then ().

for any

. Observe that any arbitrary unit vector in

can be written as

for a proper

. Therefore, for any

,

, we have

Observe also that if then and, choosing , we have that . This implies .

Finally, from (

7) and (

4) we have

□

Observe that the standard maximum likelihood estimator, MLE, for the present model is an equivariant estimator, with .

3. Minimum Riemannian risk estimators

In the framework of intrinsic analysis, where the loss function is the square of the Rao distance, the Riemannian distance induced by the information metric in the parameter space , once the class of the equivariant estimators has been determined a natural question arises: which is the equivariant estimator that minimizes the risk?

First of all, we summarize the basic geometric results corresponding to the model (

1) which are going to be used hereafter. We are going to use a

standardized version of the information metric, given by the usual

information metric corresponding to this linear model divided by a constant factor

n, i.e. the number of rows of matrix

. This metric is given by

which is, up to a linear coordinate change, the

Poincaré hyperbolic metric of the upper half space

, see [

13]. The Riemannian curvature

is constant and negative and the unique geodesic, parameterized by the arc–length, which connects two points

and

, when

, is given by:

where

s is the arc–length,

and

are

vectors whose components, and also

, are convenient real integration constants, such that

,

,

,

being

the Riemannian distance between

and

. Finally,

K is given by

. When

, the geodesic is given by

where

B is a positive integration constant.

The Rao distance

between the points

and

is

where

and

or, equivalently,

Let

be the inverse of the exponential map corresponding to Levi-Civita connection and

its components corresponding to the basis field

. Then, we have

It is well know that the Riemannian distance induced by the information metric is invariant under equivariant estimator transformations. We shall supply a direct and alternative proof for the linear model setting.

Proposition 2.

The Rao distance ρ given by (11) is invariant under the action of the induced group by on the parameter space, . In other words

Proof: Observe that

and taking into account that

is the projection matrix into

F, we have

Therefore

and the invariance of

and

trivially follows. □

Proposition 3.

acts transitively on Θ.

Proof: The transitivity follows observing that a is an arbitrary positive real number and is the projection matrix into F with . □

Since

, and thus

, is invariant under the action of

and

acts transitively on

, the distribution of

does not depend on

, and therefore, the risk of any equivariant estimator remains constant and independent of the target parameter provided that this risk is finite. More precisely, observe that if we let

from (

1) and (

4) we clearly have that

with a rank

m idempotent covariance matrix, and

and

are independent random variables following a chi-square distribution with

m and

degrees of freedom, equal to the dimensions of

F and

since

and

are quadratic forms based on the projection matrices on these subspaces of

and

(or

) and

are independent random vectors. Therefore, since

and

, we have that

and

or

which have a distribution which depend only on

and

, independent random variables with fixed distribution, whatever the value of

.

Since the risk of any equivariant estimator remains constant on the parameter space, it’s enough to examine it at one point, for instance at the point . Let us denote the expectation with respect to the n–variate linear normal model by and by E the . We can prove the following propositions.

Proposition 4.

for any .

Proof: From (

14) and (

13), since

we have

developing the square of the difference and taking into account that the standard Euclidean norm of a vector is less or equal to the absolute value of the sum of its components, we obtain

Notice that both bounds (

22) and (

23) are invariant under the action of the induced group on the parameter space.

As we mentioned before, from [

14], it is enough to prove that the risk is finite at

. Taking into account (

16) it follows, from (

23), that

Observe that if

Q has a chi-square distribution with

k degrees of freedom

Therefore, since

and

are independent random variables following a central chi-square distribution with

m and

degrees of freedom, we have

and

Then, taking the average, it follows that

Since n and m are positive integers being , we conclude that the risk is finite if . □

Proposition 4 is a sufficient condition for the existence of the Riemannian risk of the equivariant estimator

, thus

is well defined for

, which we shall assume hereafter.

Proposition 5.

There exists a unique minimizer of the Riemannian risk given by Φ.

Proof:

Let us consider the Riemannian risk at

as a function of

s, that is

The particular selection of

, from which

F follows, relies on the Riemannian structure of

induced by the information metric. The Riemannian curvature is constant and equal to

and taking into account (

10) we have that

is a geodesic in

; precisely a geodesic parameterized by the arc–length, see [

13] for further details.

Then, following [

15], the real valued function

is strictly convex. Since almost surely convexity of a stochastic process carries over the mean of a process, the map

F is strictly convex as well.

On the other hand, from Fatou’s Lemma as or . This, together with the strict convexity of F yield the existence of a unique minimizer of the function F, which depends on n and m.

Finally, since the map is a strictly monotonous function; must exist a unique , namely , such that . □

In fact, this result guarantees the unicity of the MIRE, although a numerical analysis is required to obtain it explicitly (see next section). It could be useful to develop a simple approximate estimator, that shall be referred hereafter

a-MIRE, obtained, luckily, minimizing a convenient upper bound of

. Since

we shall have

and therefore

the upper bound

it is clearly a convex functions with an absolute minimum attained when

satisfy

Furthermore, given an arbitrary

m, we have

and, therefore,

a-MIRE is very close to MLE for large values of

n. Observe also that it is possible to compute

a-MIRE for

, a condition which is slightly stronger that the result required for the existence of MIRE in proposition (4).

A further aspect is the intrinsic bias of the equivariant estimators. In fact connections between minimum risk, bias and invariance have been established, see [

14]. Since the action of the group

G is not commutative, we cannot guarantee the unbiasedness of the MIRE and an additional analysis must be performed. First of all we are going to compute the vector bias, see [

4], a quantitative measure of the bias which is compatible with Lehmann results.

Let

and

be the components of

corresponding to the basis field

,

. With matrix notation,

. Furthermore, let us define

for

and

; taking into account (

16), (

19) and from (

11) and (

15) we have

where

and

Let be the intrinsic bias vector corresponding to an equivariant estimator evaluated at the point and let be their components. In matrix notation, . We have

Proposition 6.

If , the bias vector is finite and

where and are independent random variables following a chi-square distribution with m and degrees of freedom respectively.

Moreover, the square of the norm of the bias vector is constant and given by

Proof: Observe that if

we have

where

denotes the Riemannian norm at the tangent space at

.

On the other hand taking into account (

31) and defining

as in (

16) observe that

,

is independent of

and

and

has the same distribution. Then we have

and since

it follows that

.

is obtained directly from (

31). The distribution of

and

follow from basic properties of multivariate normal distribution. Finally, the norm of the bias vector field follows from (

32) and (

8).

□

We may remark, finally, that the norm of the bias vector field of any equivariant estimator,

, is invariant under the action of the induced group,

, on the parameter space and since this group acts transitively on

, this quantity must be constant, which is clear from (

33).

4. Numerical Evaluation

In this section we are going to compare, numerically, the MIRE estimator with the standard MLE. Observe that both estimators only differ in the estimation of the parameter

(or

). Precisely, the MIRE and the MLE of

are, respectively,

namely, they only differ by the factor

, since

.

In order to compare MLE with the MIRE we have computed the factor , the intrinsic risk and the square of the norm of the bias vector for each estimators. All the computations have been performed using Mathematica 10.2.

Moreover, we have suggested a rather simple approximation for

, or

, which allow us to approximate MIRE estimator through (

29), i.e.

The corresponding estimator, that shall be referred hereafter as a-MIRE, has been also compared with MLE and MIRE in terms of intrinsic risk.

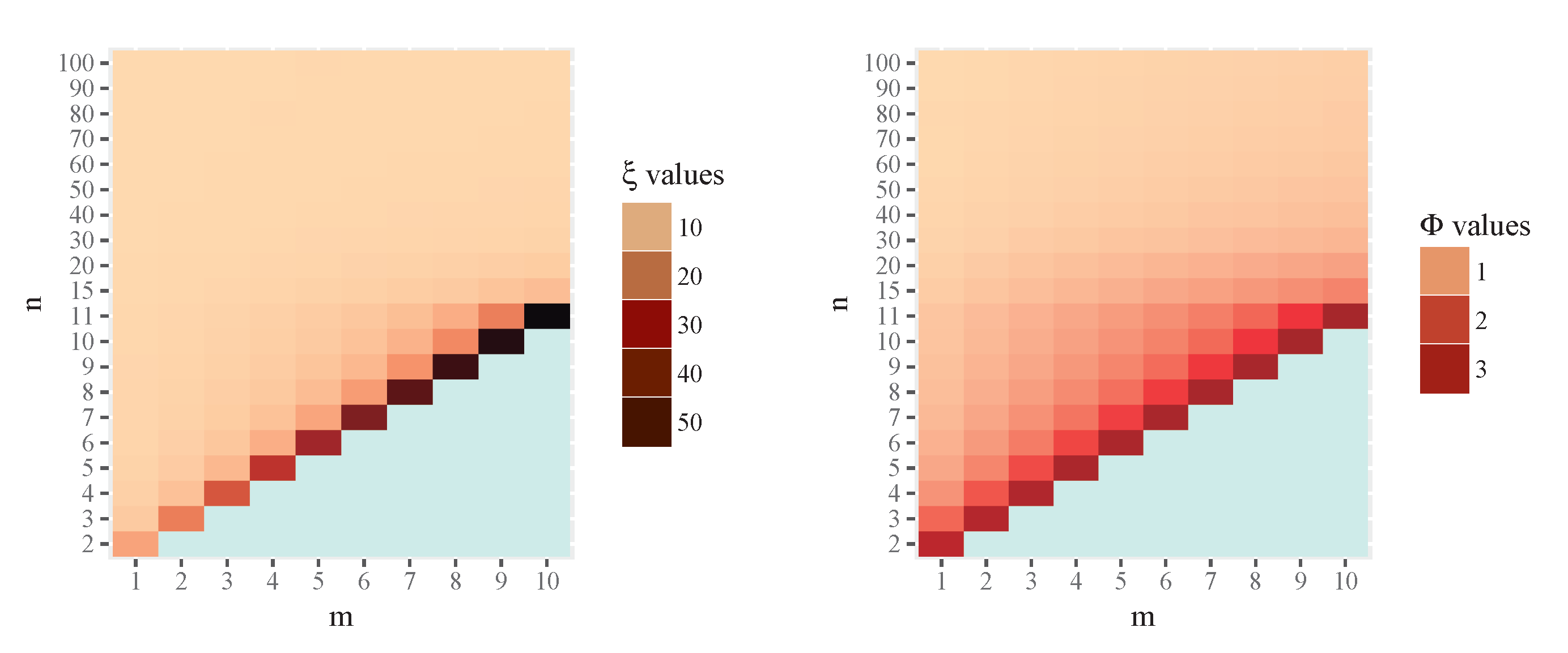

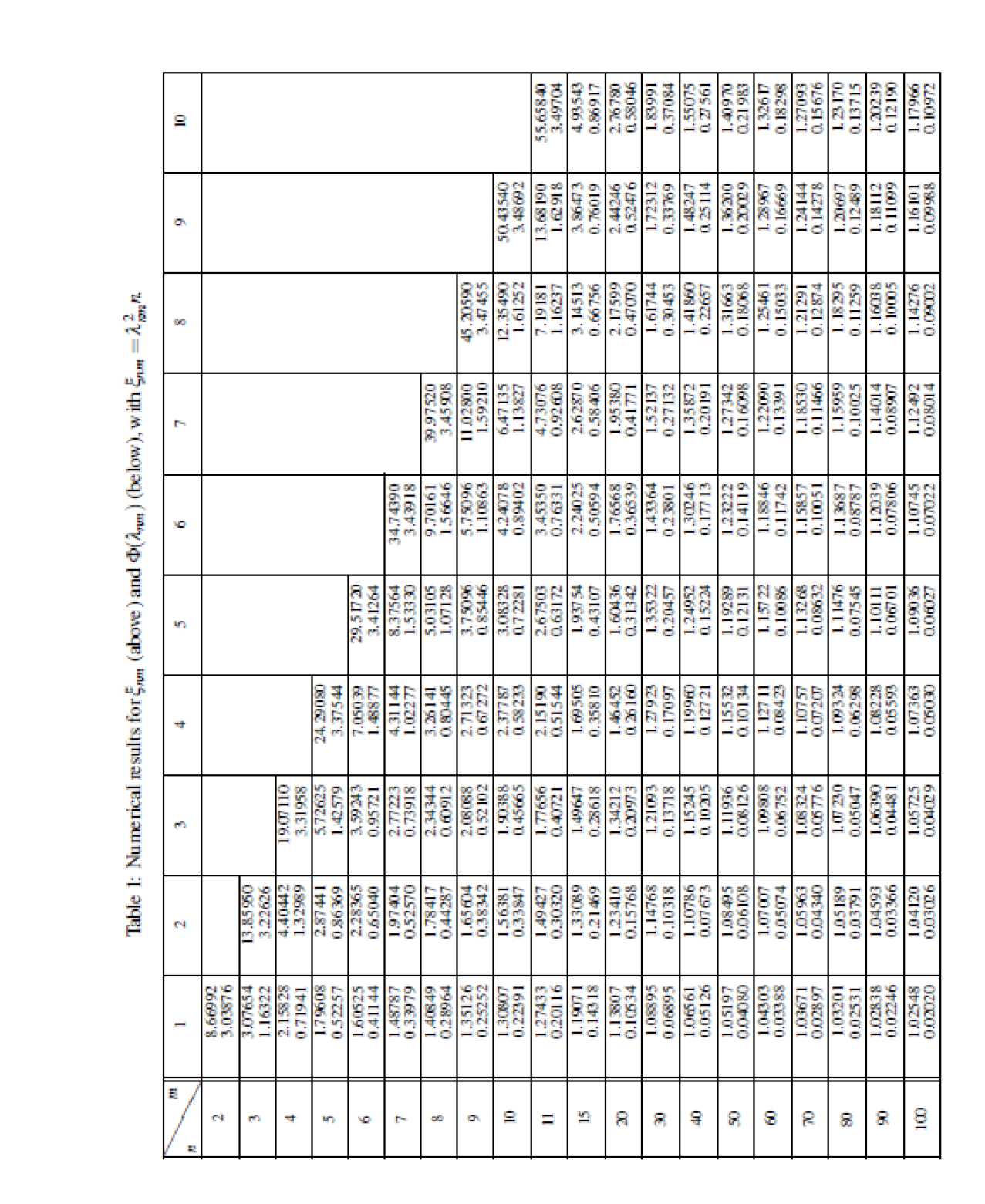

The results are summarized in the following figures which summarize the tables given in the Appendix, see [

16] for a convincing argument for the use of plots over tables. In

Figure 1 numerical results of

(left) and

(right) are displayed graphically. Observe that, for

m fixed, as

n increases

goes to zero and

goes to one. The exact numerical values are given in the Appendix, Table 1.

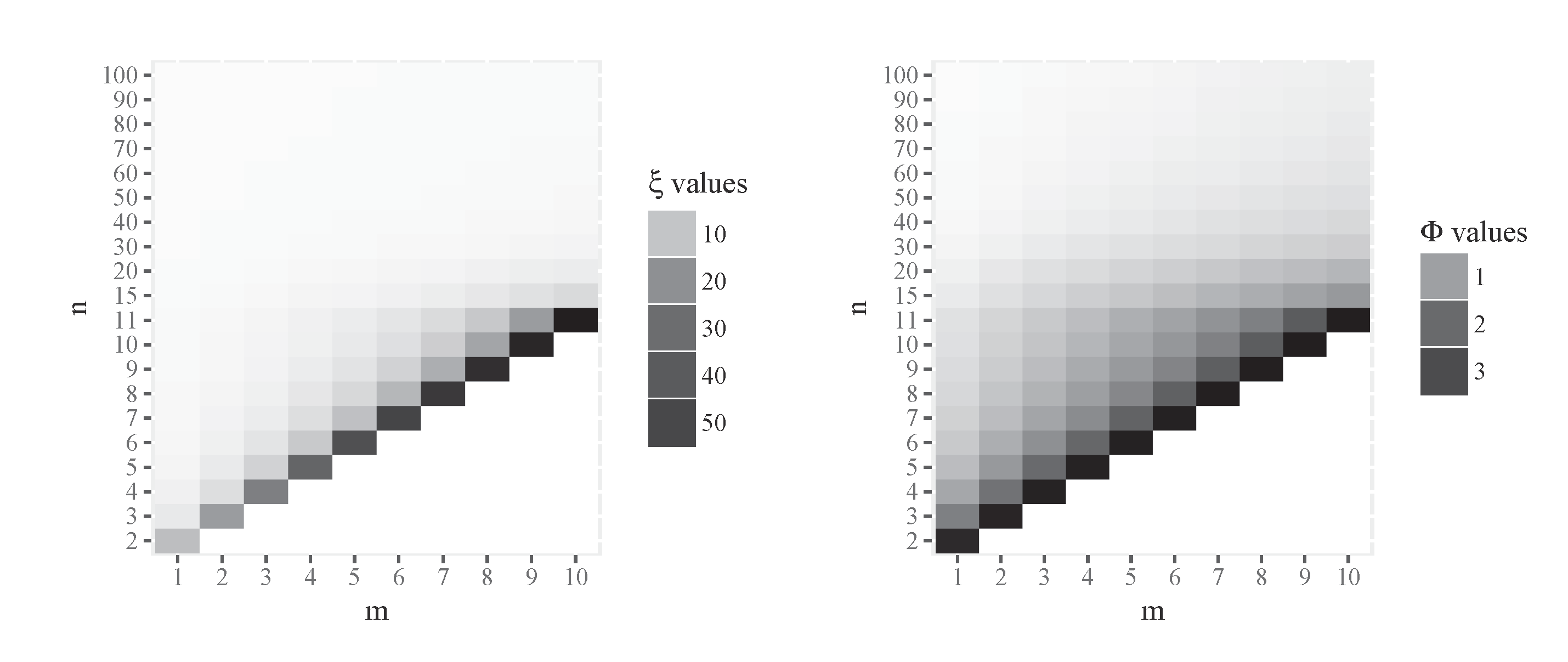

Figure 1.

Numerical results for (left) and (right), with .

Figure 1.

Numerical results for (left) and (right), with .

Figure 2.

Numerical results for (left) and (right), with .

Figure 2.

Numerical results for (left) and (right), with .

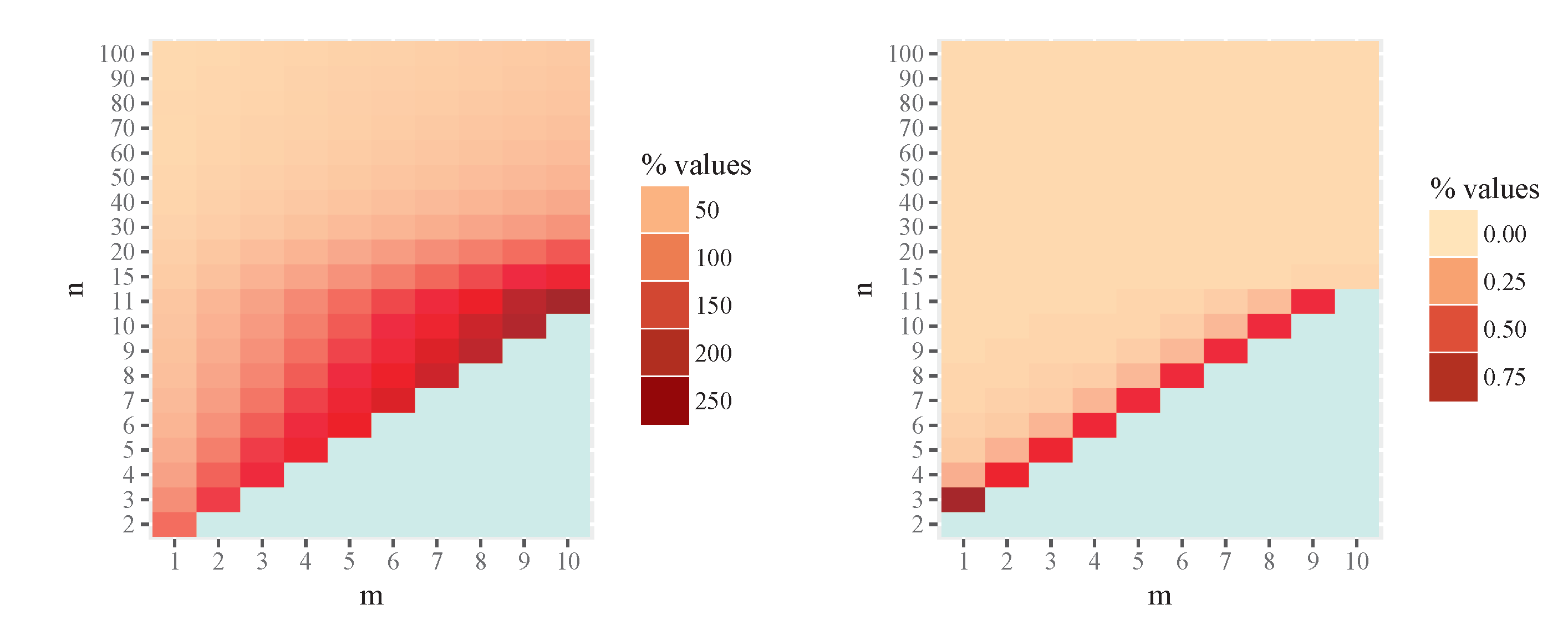

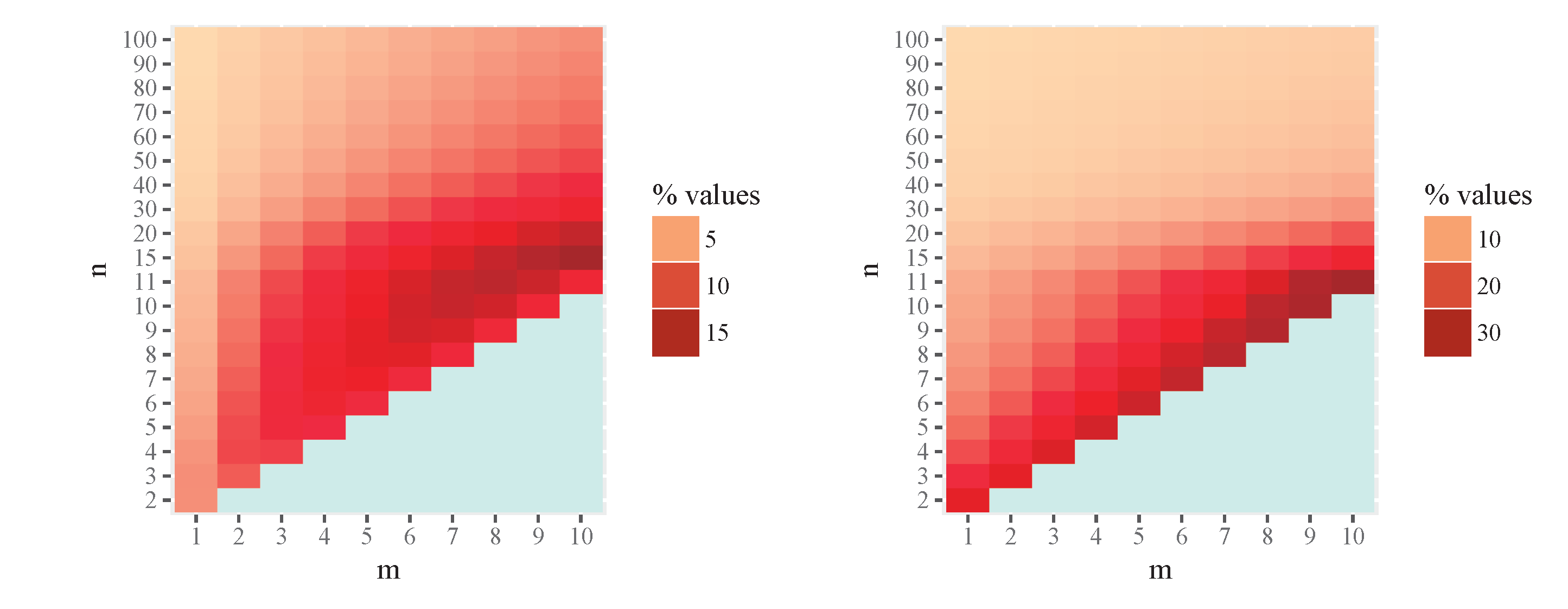

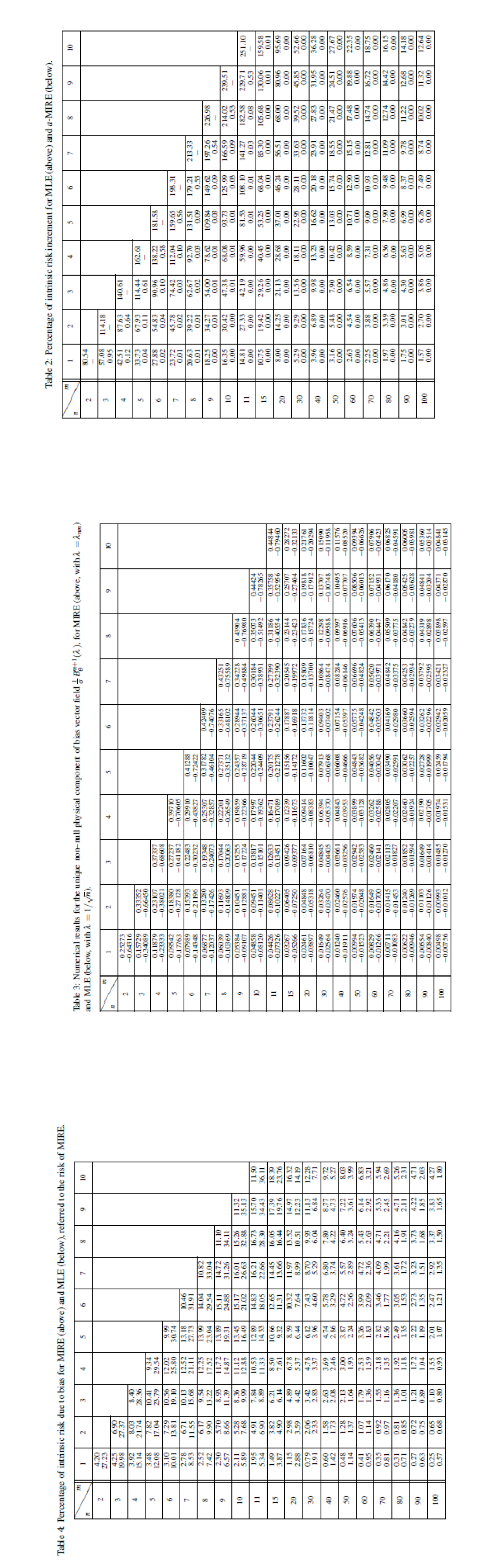

Figure 3 shows graphically the percentage of intrinsic risk increment for MLE (left) and

a-MIRE (right), that is

respectively, for some values of

n and

m. The exact numerical results are given in the Appendix, Table 2.

Observe that if we approximate the MIRE by the MLE for a certain value of

m, the relative difference of risk decreases as

n increases. Notice that these relative differences of risks are rather moderate or small (about 10-15%) only if

. Let us remark also the non appropriate behavior of the MLE for small values of

. This regards to the intrinsic risk increment: when we use MLE instead of MIRE this increment oscillates between

and

when

with

m from 1 to 10. On the other hand, the behavior of the

a-MIRE is reasonably good, with its intrinsic risk very similar to the risk of the MIRE estimator: here the percentage on risk increment is less than

for all studied cases and also this percentage decreases as

n increases. In fact this percentage is lower than 1‰ when

, which indicates the extraordinary degree of approximation, being therefore the

a-MIRE a reasonable and useful approximation of MIRE. In particular as an example, for a two way analysis of variance, with

a and

b levels for factors

A and

B respectively, with a single replicate for treatment we shall have

with

and

, while the corresponding quantity for MLE is

.

In particular if

and

we shall have

and

, which is sensibly different. At this moment, it could be useful to recall that the quadratic loss and the squared of the Riemannian distance behaves very different, see [

5].

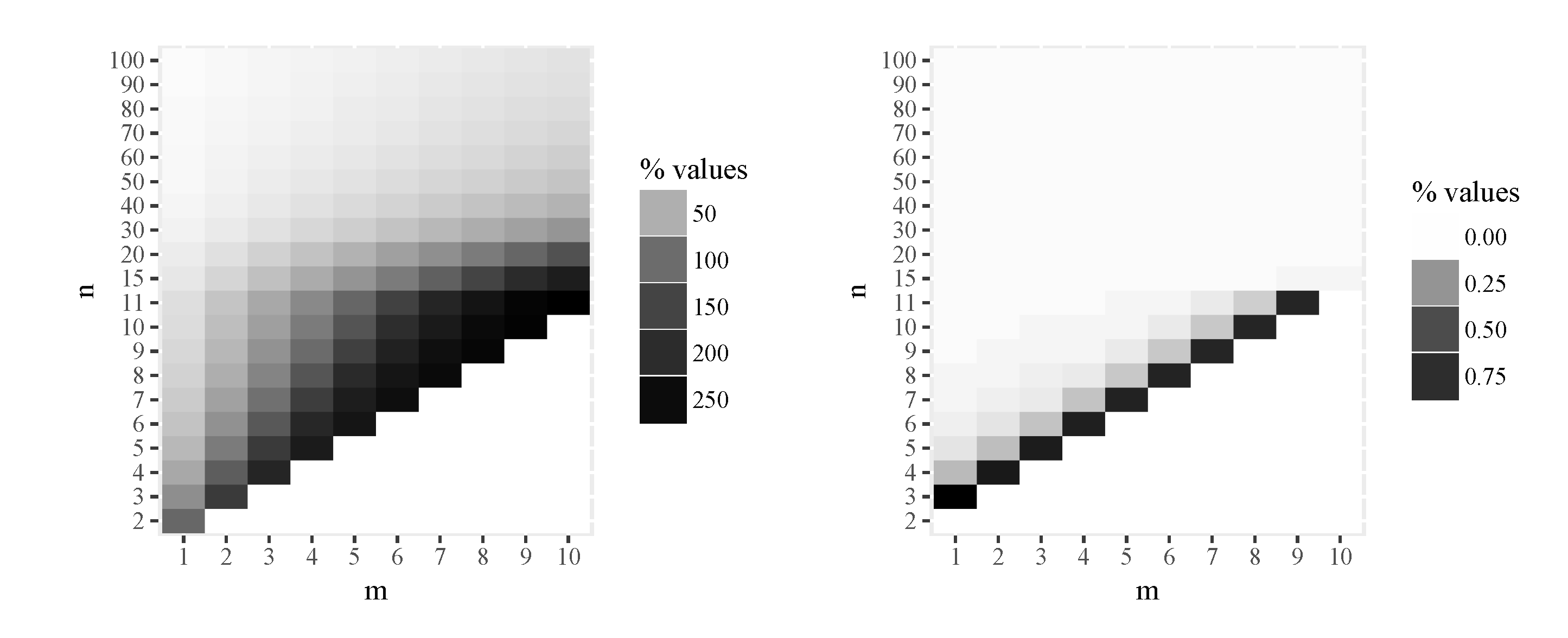

Figure 3.

Percentage of intrinsic risk increment for MLE (left) and a-MIRE (right).

Figure 3.

Percentage of intrinsic risk increment for MLE (left) and a-MIRE (right).

Figure 4.

Percentage of intrinsic risk increment for MLE (left) and a-MIRE (right).

Figure 4.

Percentage of intrinsic risk increment for MLE (left) and a-MIRE (right).

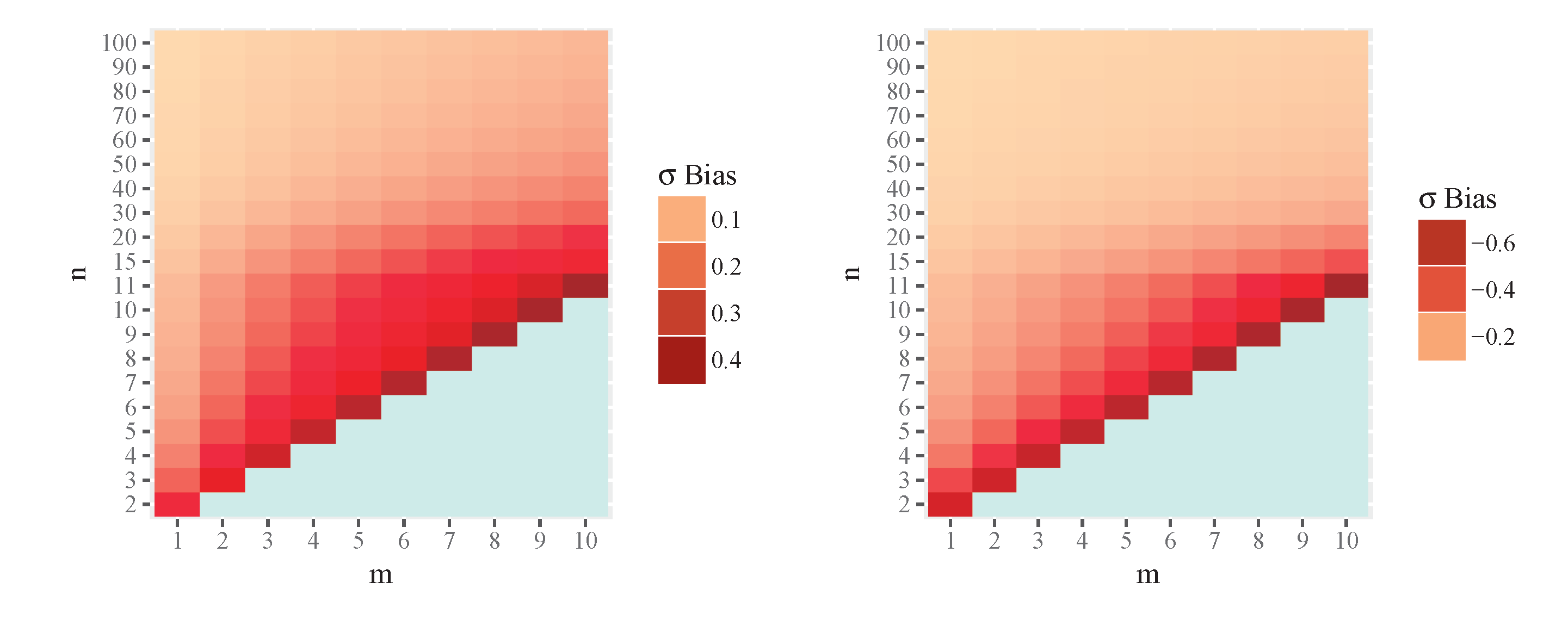

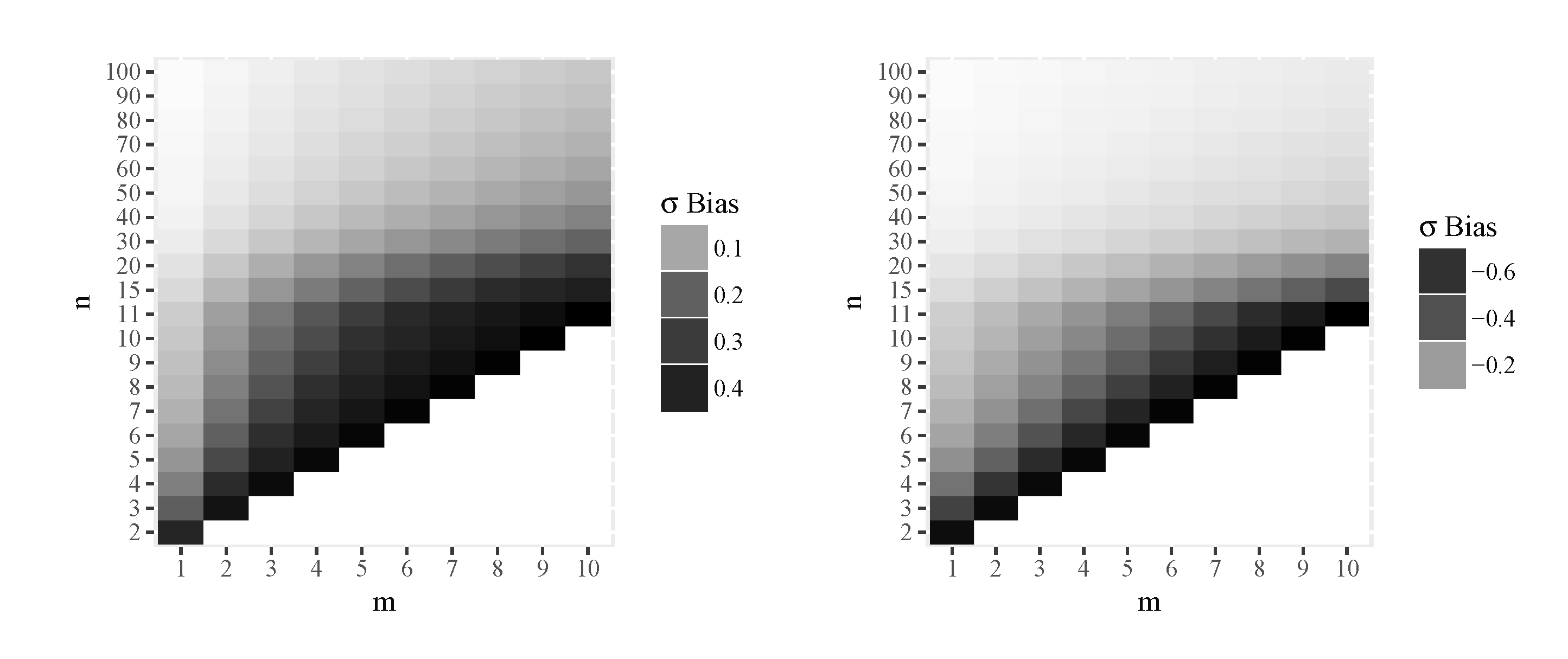

Figure 5 displays graphically the numerical results of the

component of the bias vector divided by

, i.e. the unique non zero physical component of this vector field, for MIRE (left) and MLE (right),

and

respectively, for some values of

n and

m. Observe the sign differences, meaning that MIRE overestimates, in average,

while MLE underestimates this quantity, in average as well. This follows from the equation of the geodesics of the present model (

9). The exact numerical values are given in the Appendix, Table 3.

Figure 5.

Numerical results for the unique non–null physical component of bias vector field , for MIRE (left, with ) and MLE (right, with ).

Figure 5.

Numerical results for the unique non–null physical component of bias vector field , for MIRE (left, with ) and MLE (right, with ).

Figure 6.

Numerical results for the unique non–null physical component of bias vector field , for MIRE (left, with , positive values) and MLE (right, with , negative values).

Figure 6.

Numerical results for the unique non–null physical component of bias vector field , for MIRE (left, with , positive values) and MLE (right, with , negative values).

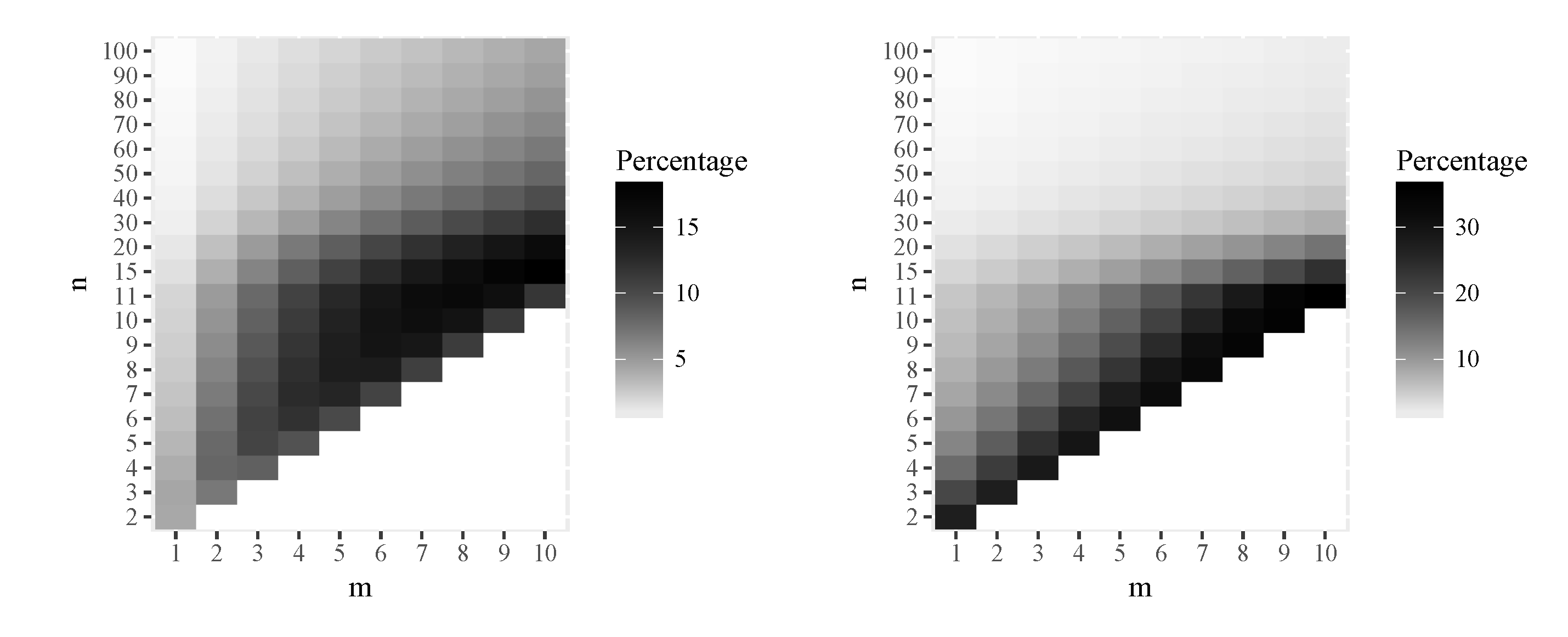

Figure 7 shows graphically the numerical results of the percentage of intrinsic risk due to bias for MIRE and MLE, that is

respectively, for some values of

n and

m. Observe that the bias is moderate, with respect the intrinsic risk, in both estimators. The bias of MIRE estimator is smaller than the bias of MLE for small values of

m and the opposite for large values. The exact numerical results are given in the Appendix, Table 4.

Figure 7.

Percentage of intrinsic risk due to bias for MIRE (left) and MLE (right), referred to the risk of MIRE.

Figure 7.

Percentage of intrinsic risk due to bias for MIRE (left) and MLE (right), referred to the risk of MIRE.

Figure 8.

Percentage of intrinsic risk due to bias for MIRE (left) and MLE (right), referred to the risk of MIRE.

Figure 8.

Percentage of intrinsic risk due to bias for MIRE (left) and MLE (right), referred to the risk of MIRE.

Acknowledgements: We have to thank the referees and the editor comments and suggestions for the improvement of this paper.