Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works of Multi-Sensor Fusion in Autonomous Vehicle

2.1. Camera Segmentation and LiDAR Signal Representation

2.2. Decision Making for Autonomous Vehicles

2.3. Route Planning and Path Finding

3. System Architecture and Implementation

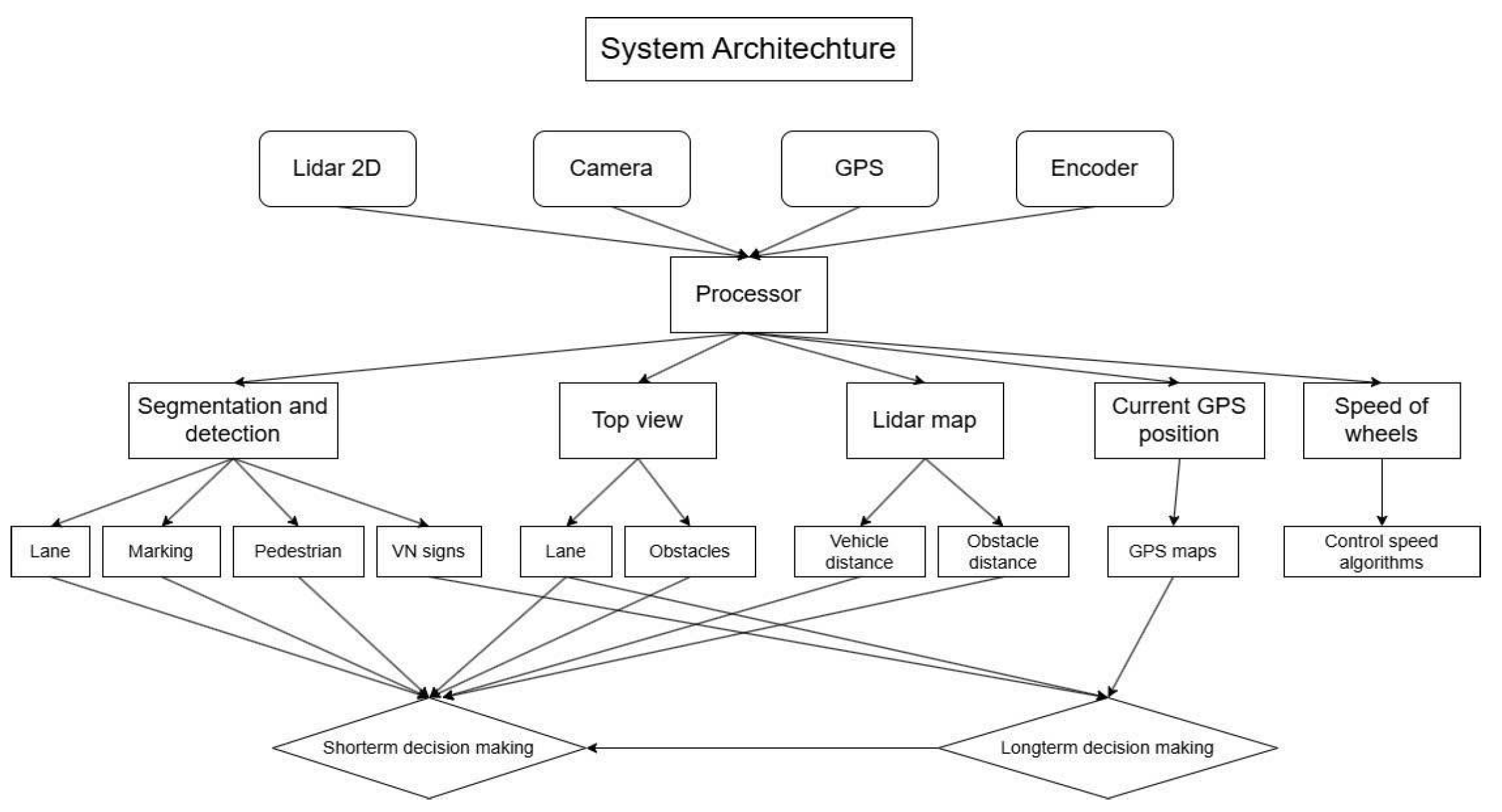

3.1. System Architecture Proposal

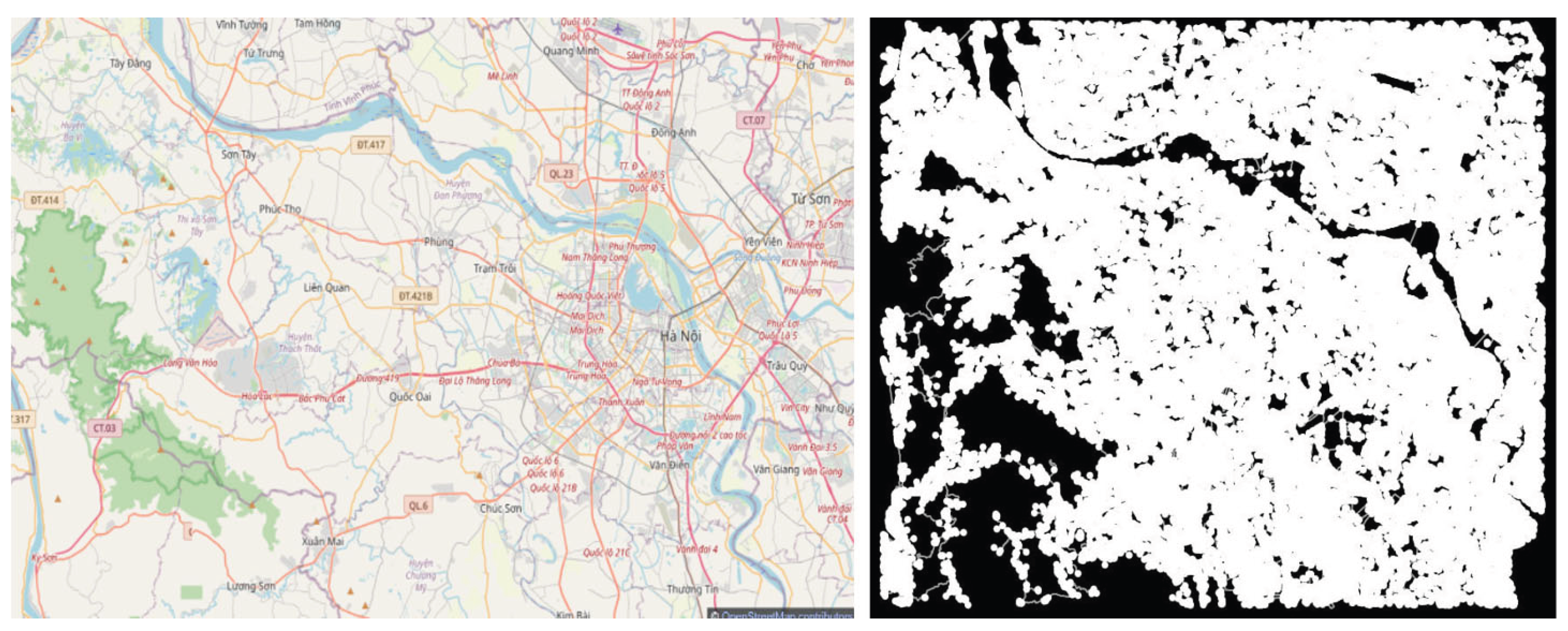

3.2. Implementations

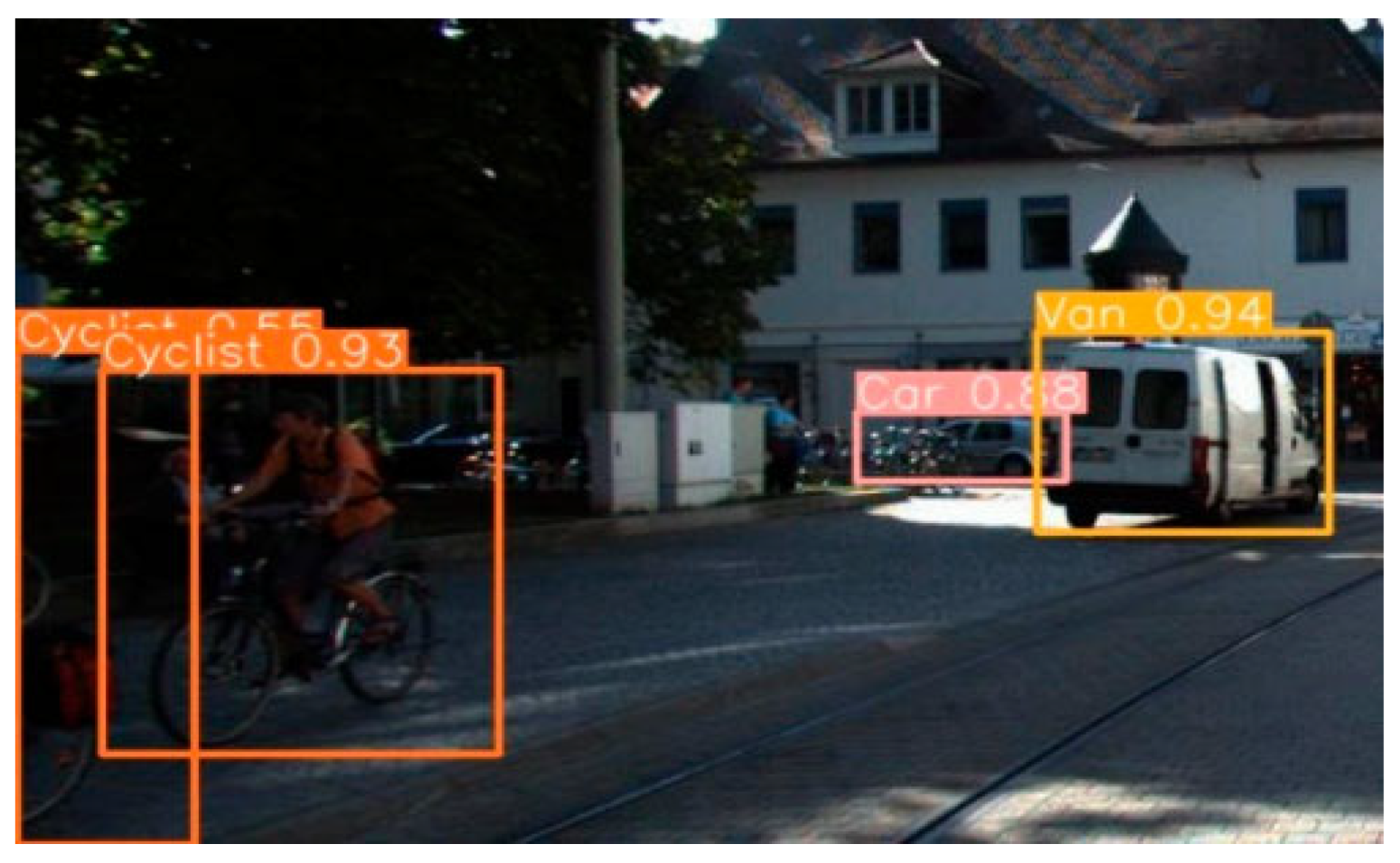

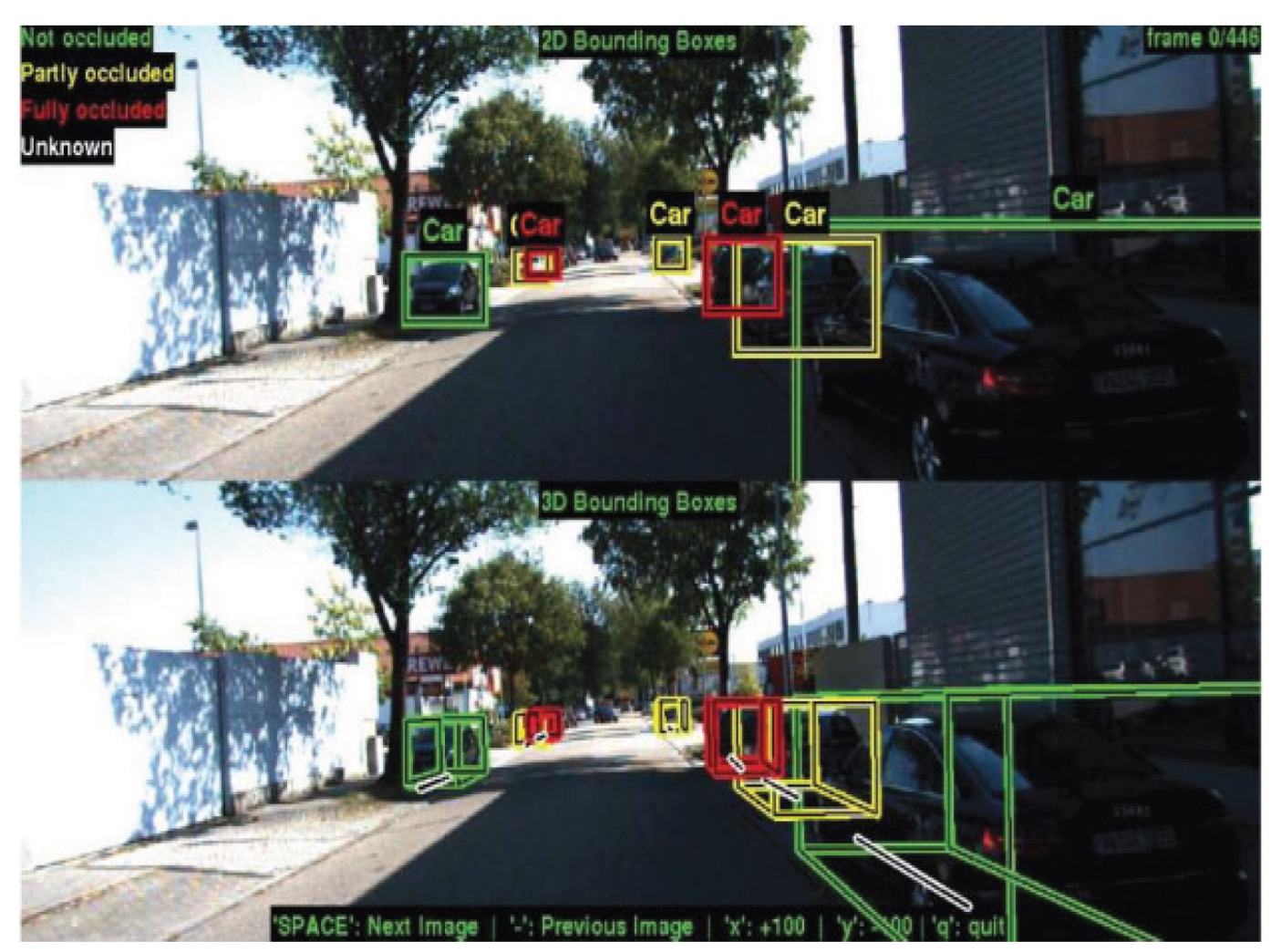

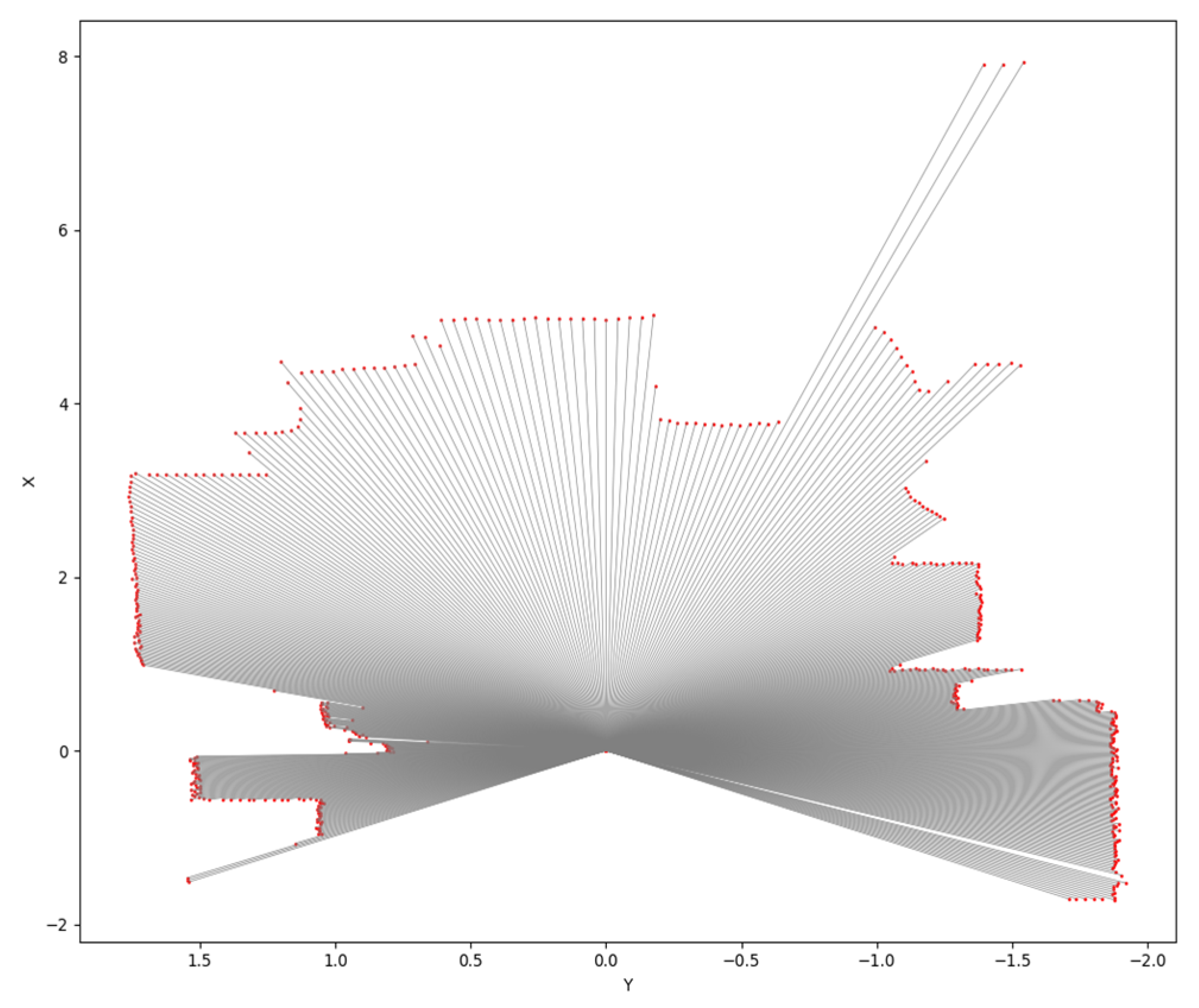

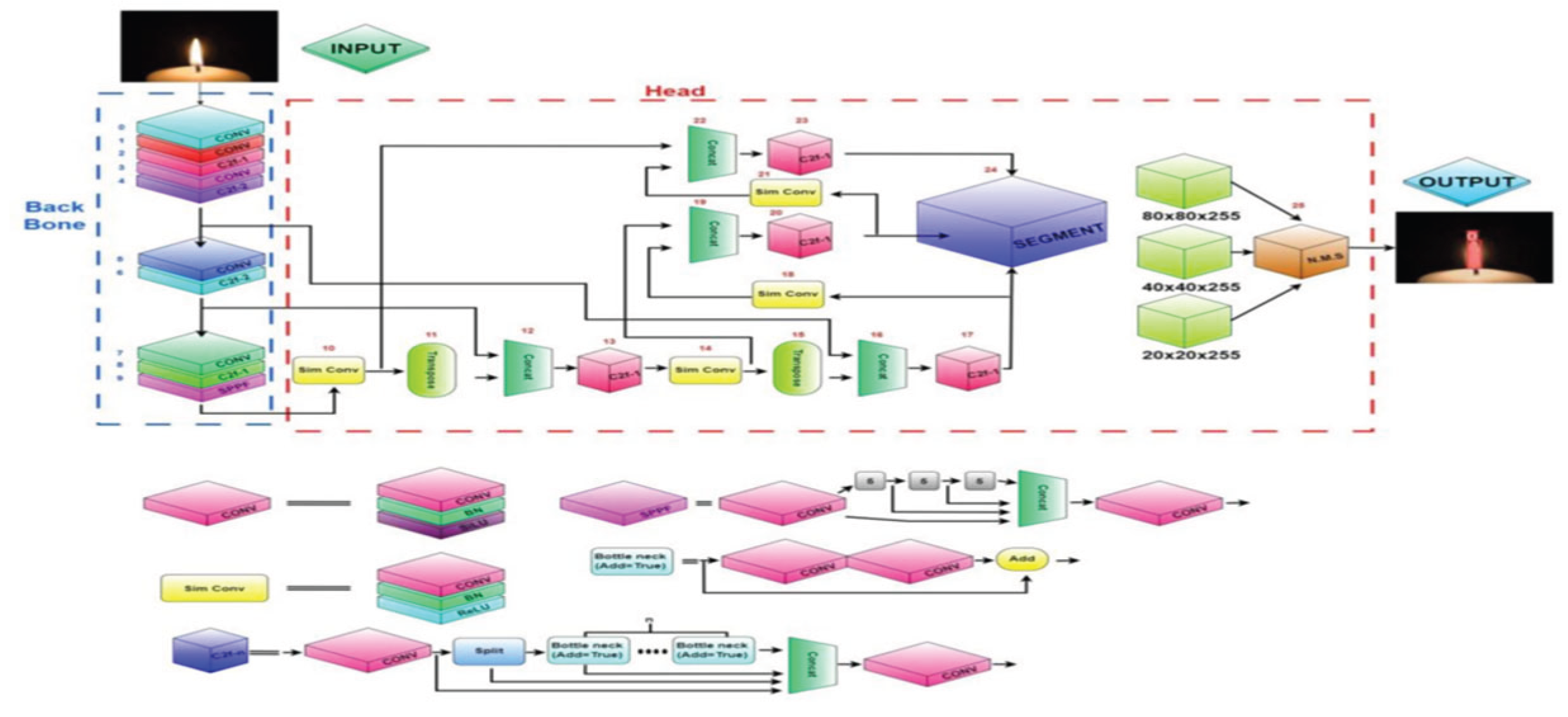

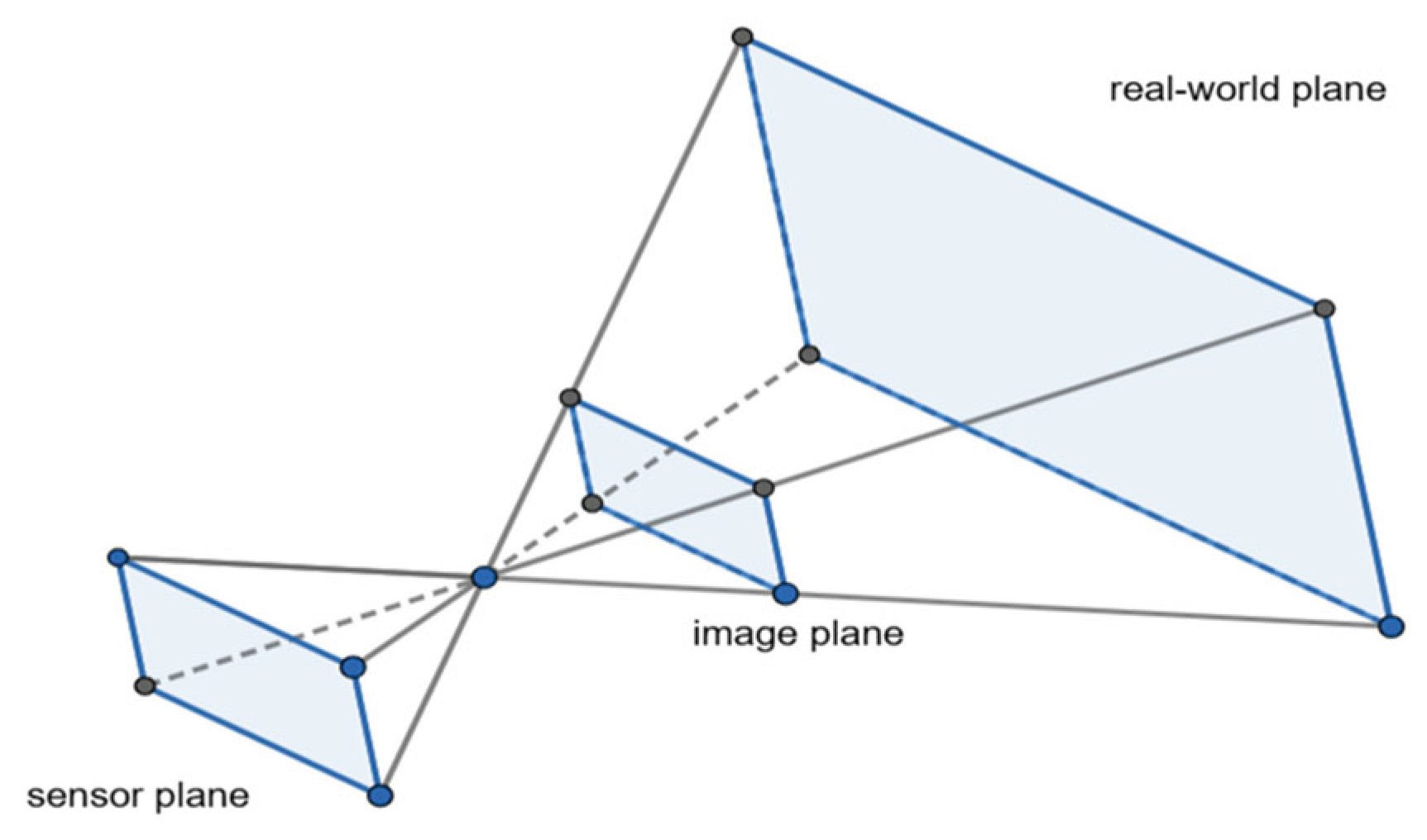

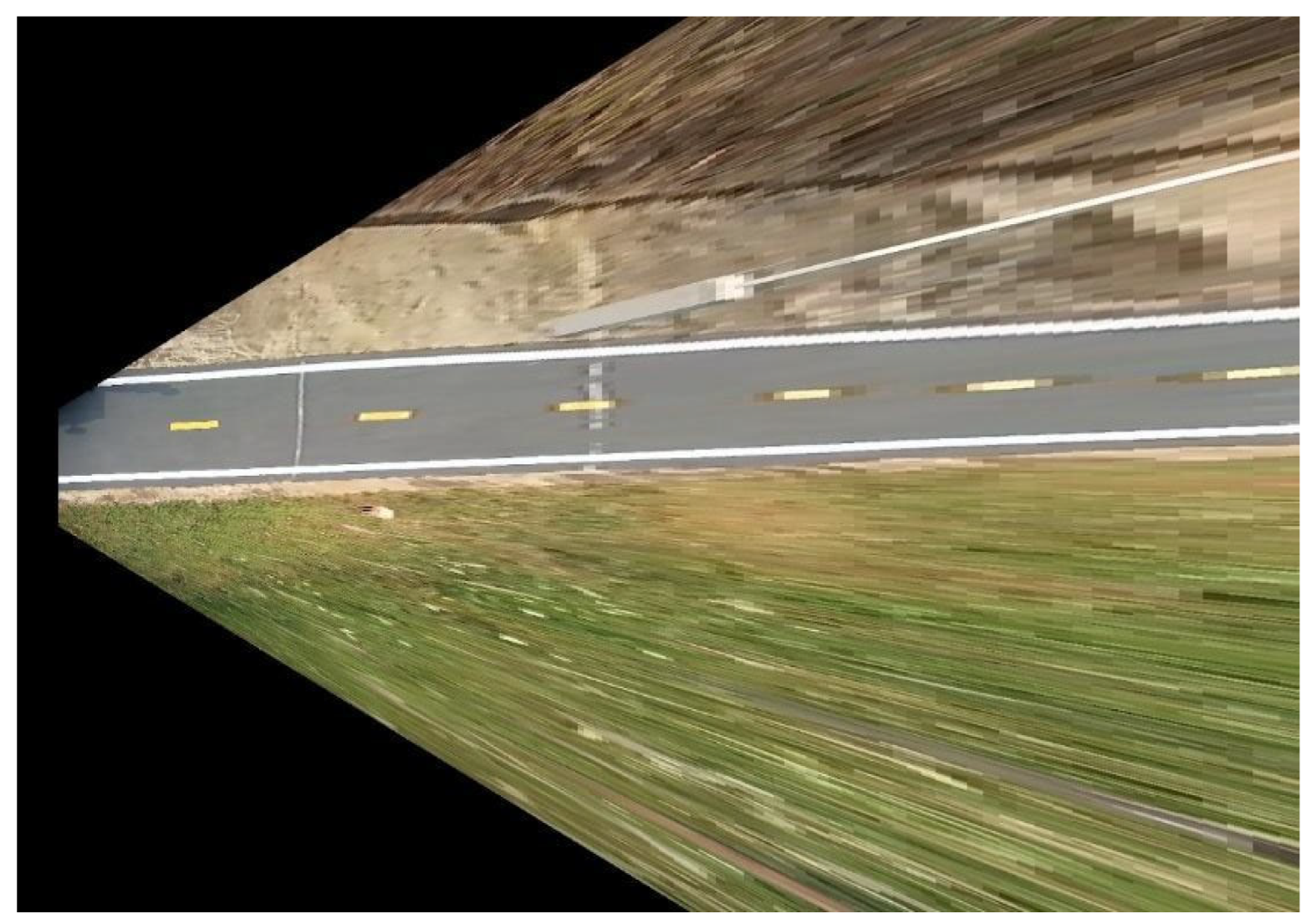

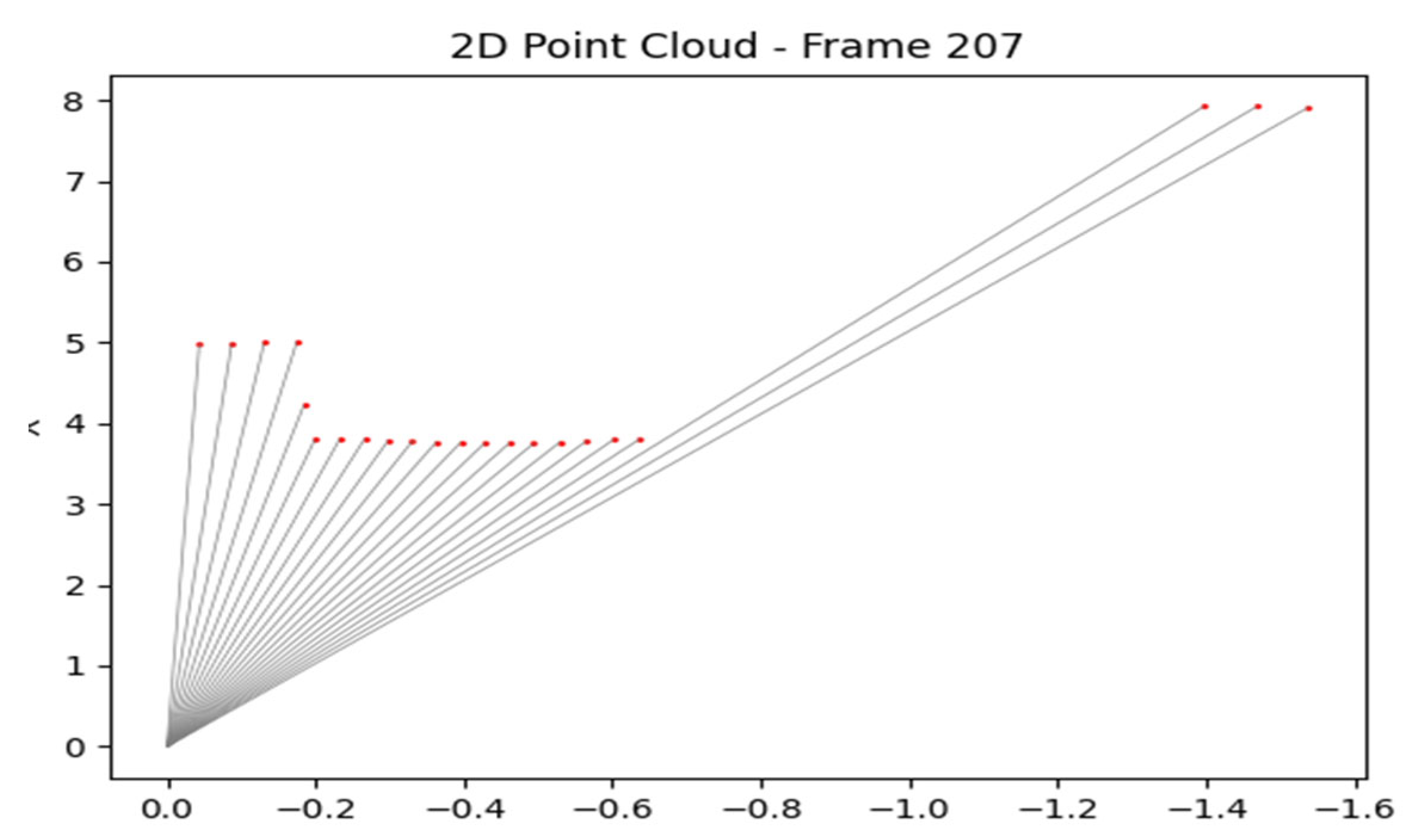

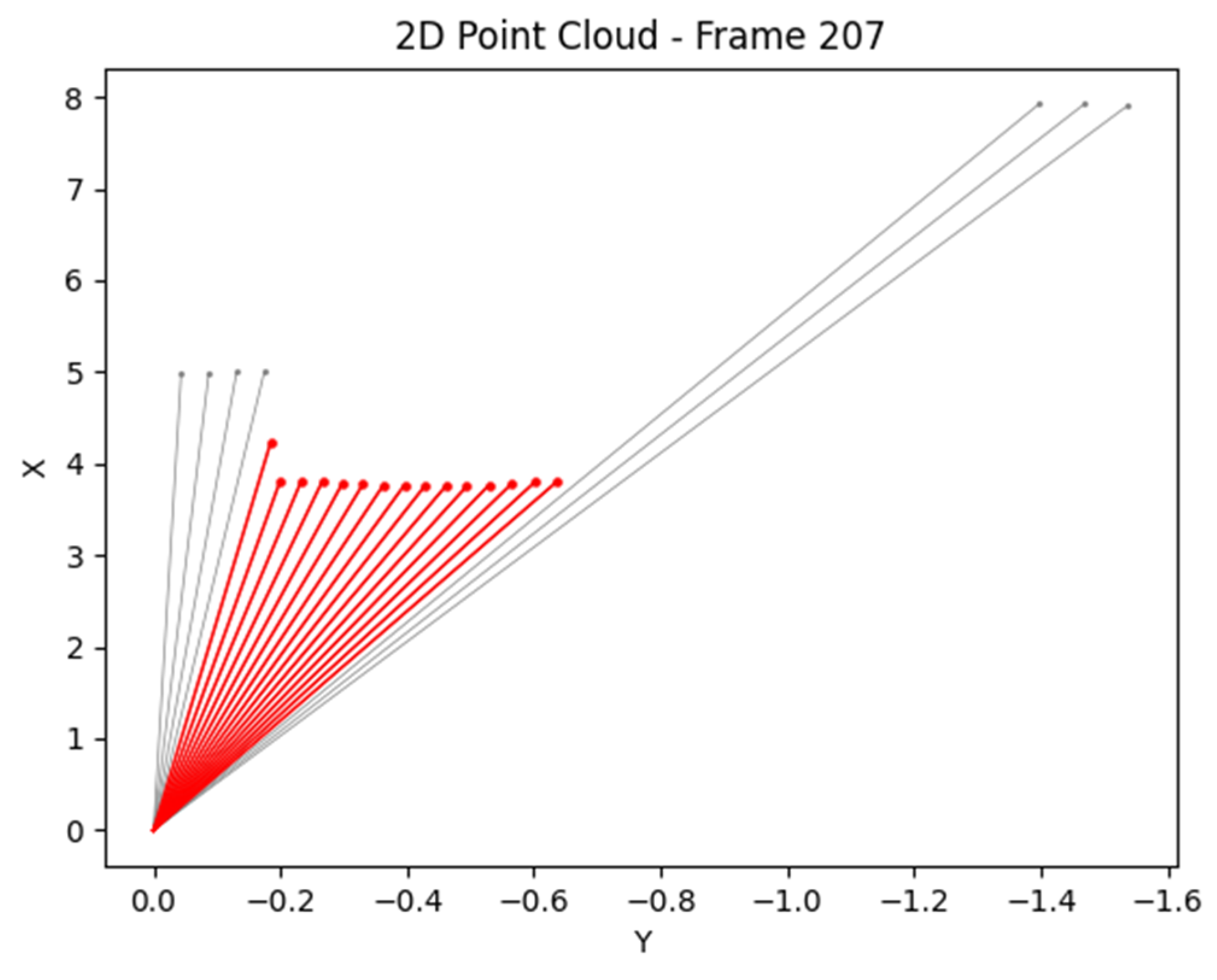

3.2.1. YOLOv8 Instance Segmentation and 2D Lidar Fusion and Perception Visualization

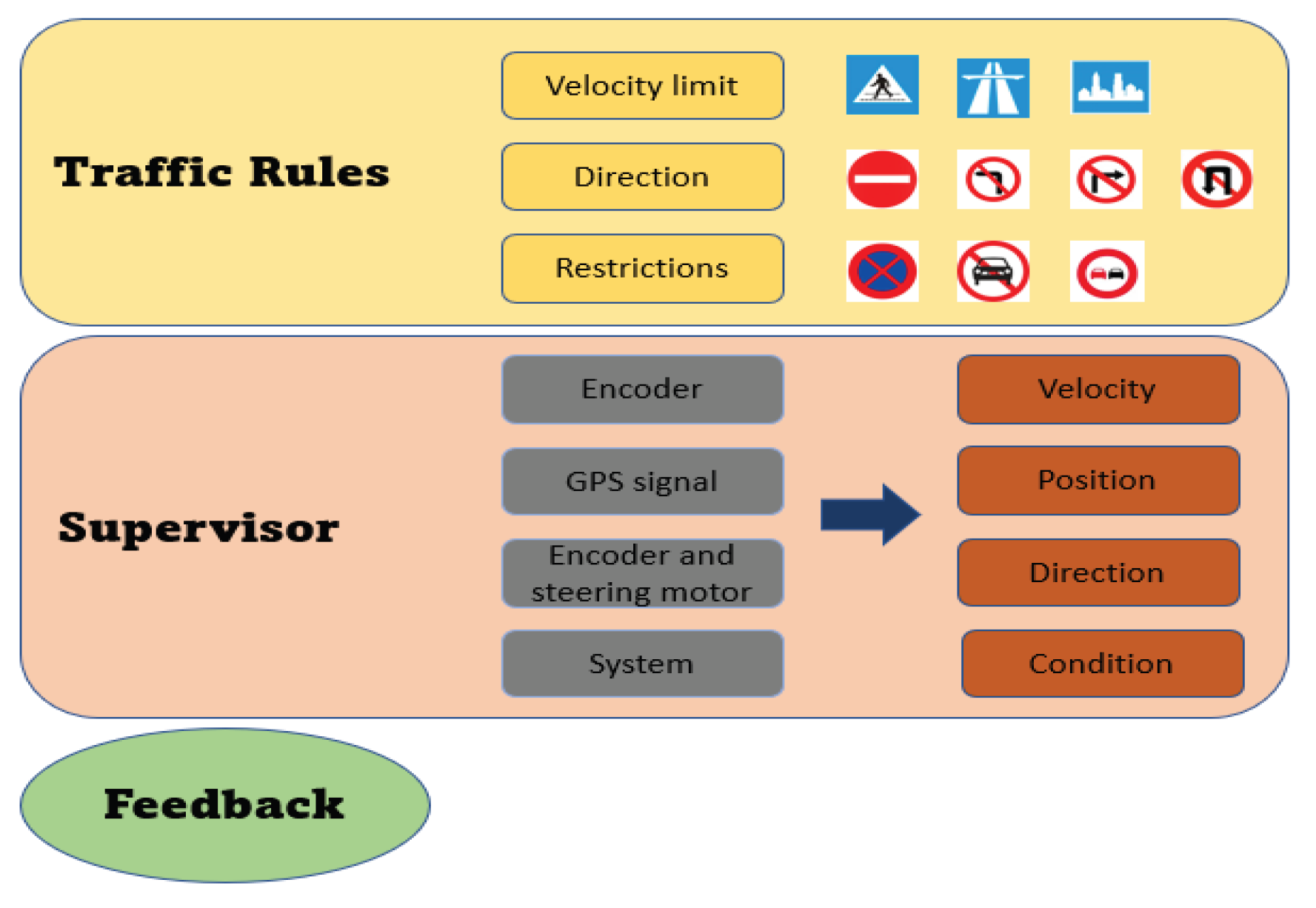

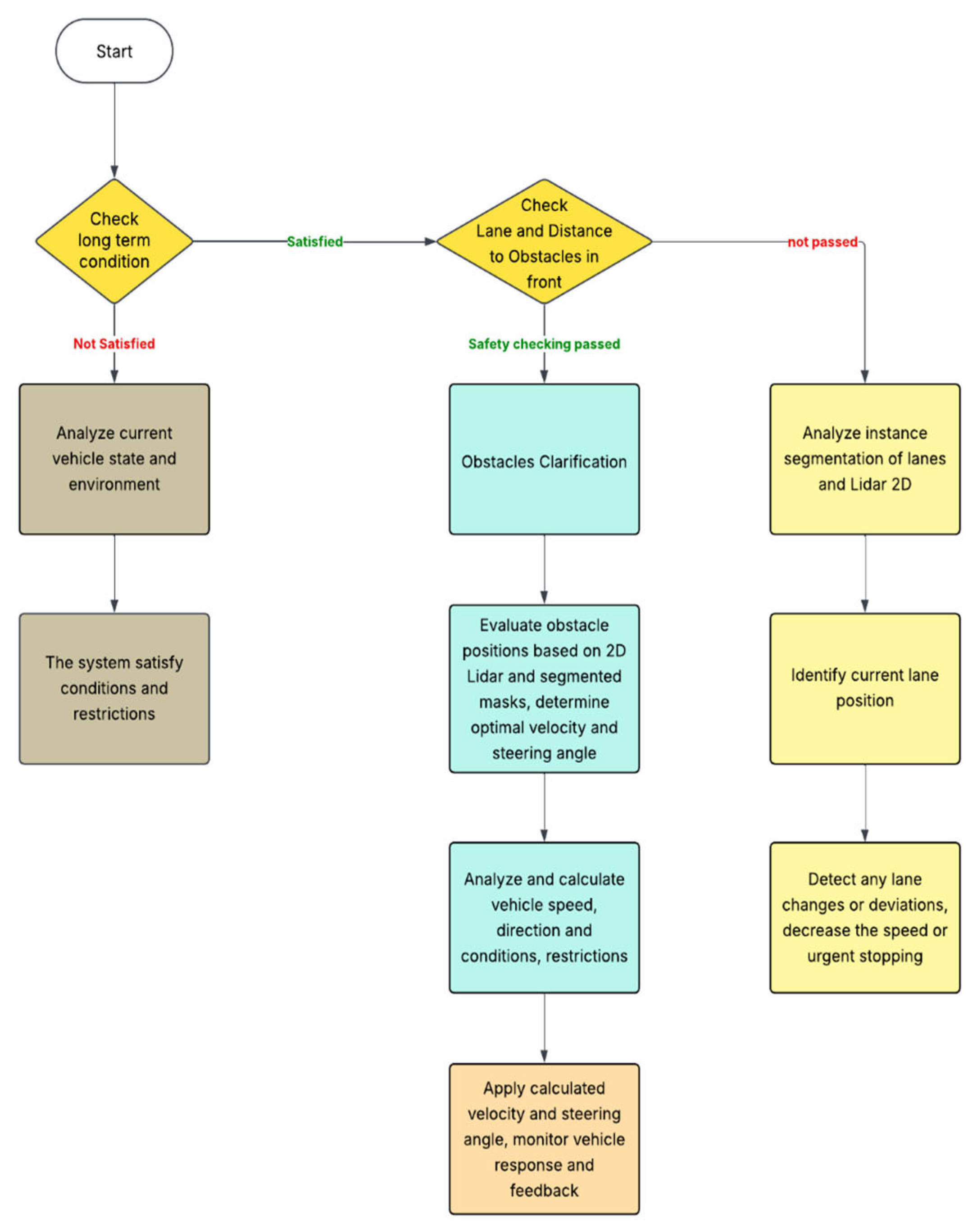

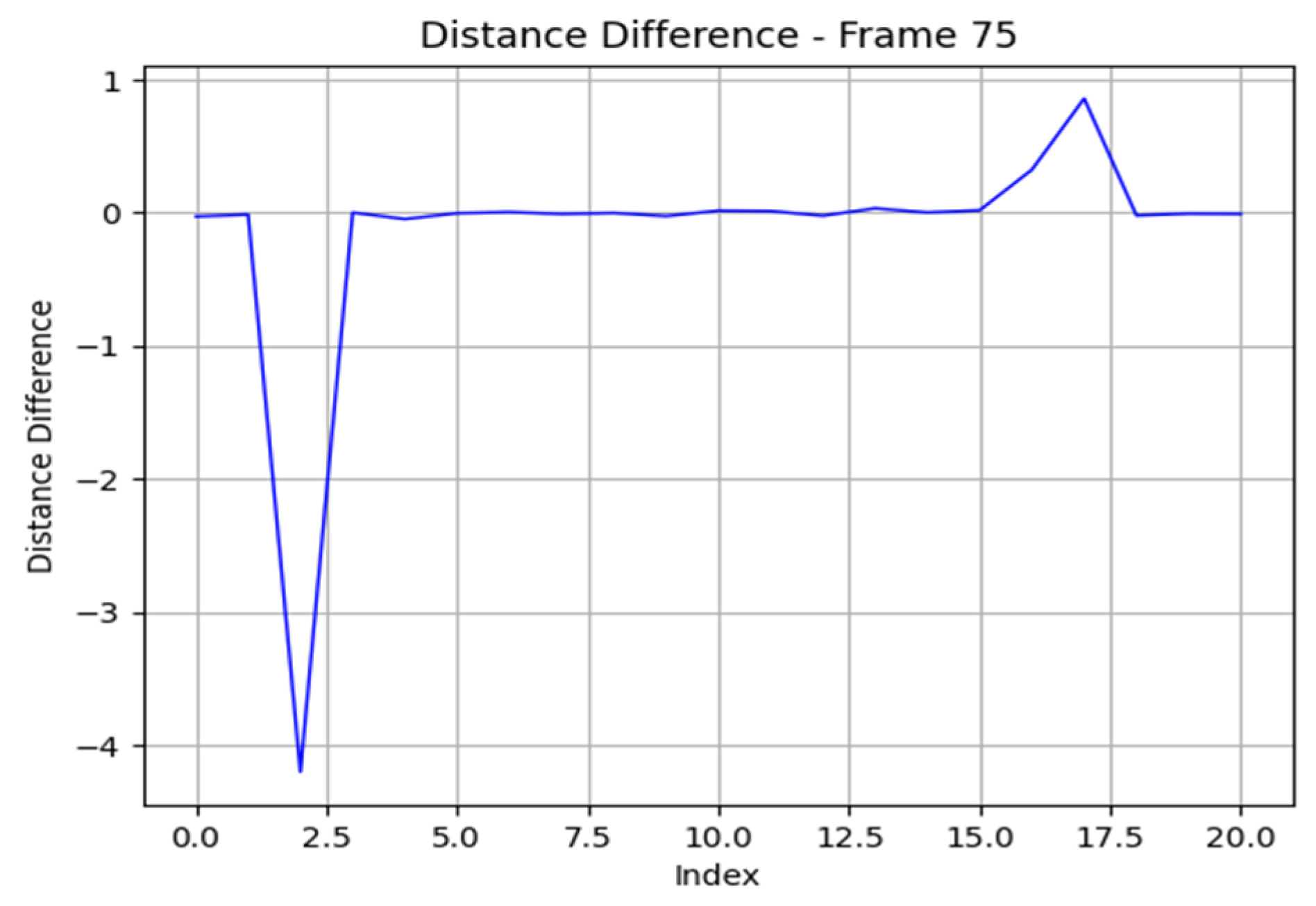

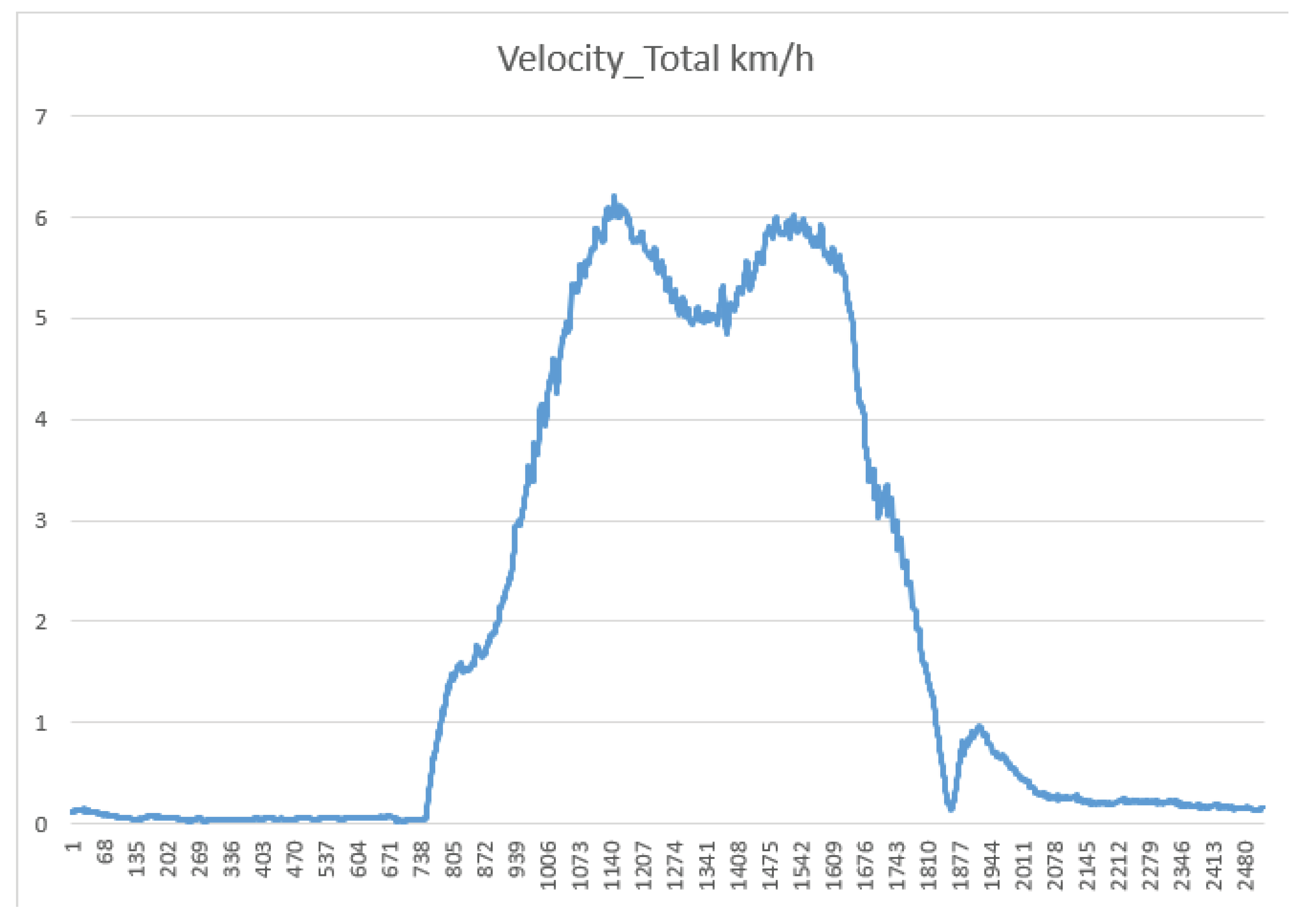

3.2.2. Long short-term decision-making architecture based on sensor exploitation

- is the risk to the vehicle

- is the distance from individual ray to lidar

- is the number of values in sliding array.

- risky coefficient respect to different

- is the lateral offset (if applicable).

- is the wheelbase (distance between front and rear axles).

- is the cotangent of the steering angle.

- is the track width of the vehicle.

4. Experiments and Results

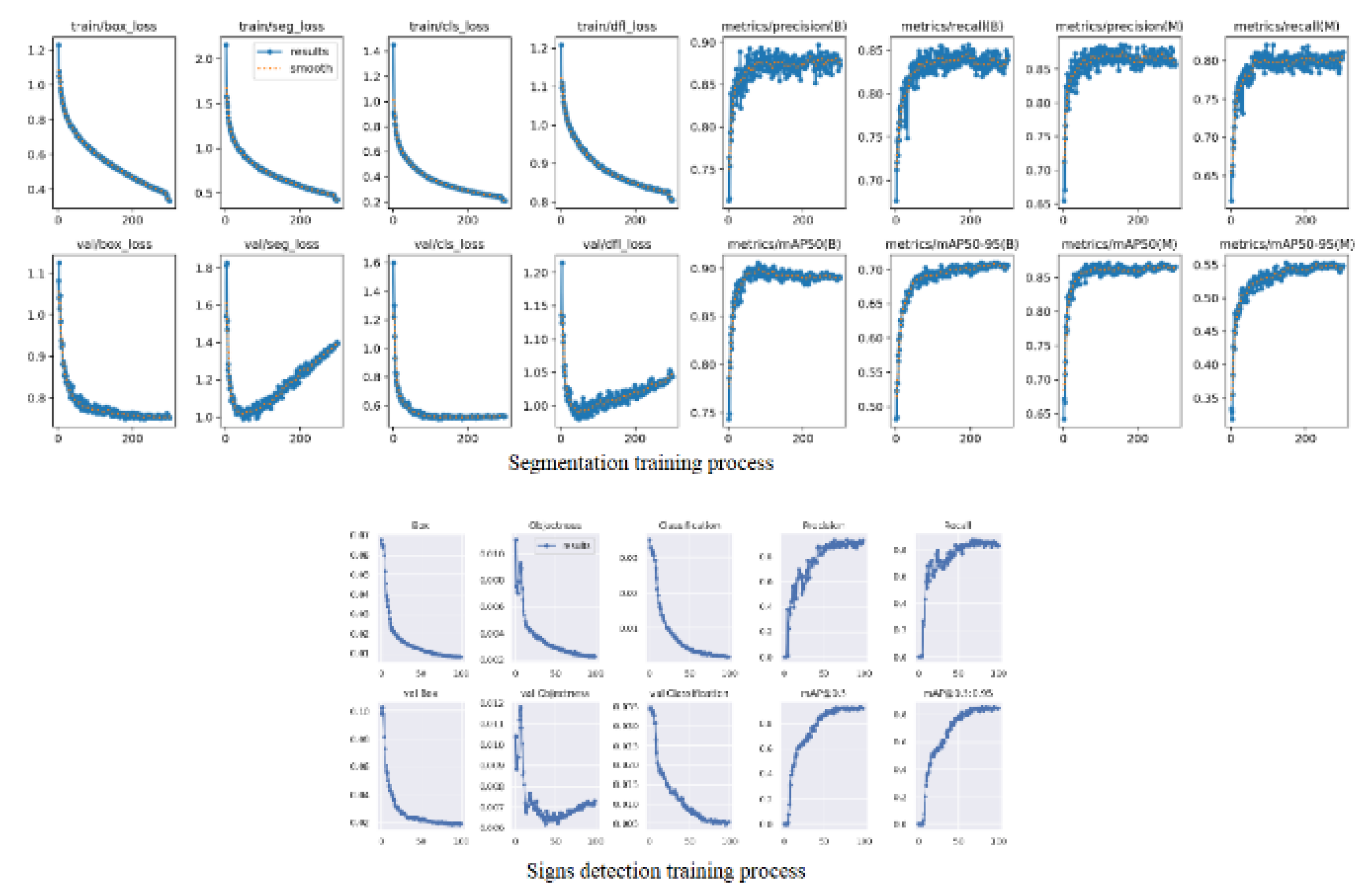

4.1. Results of YOLOv8 Instance Segmentation and 2D Lidar Fusion and Top View for Vehicle Front-view Visualization

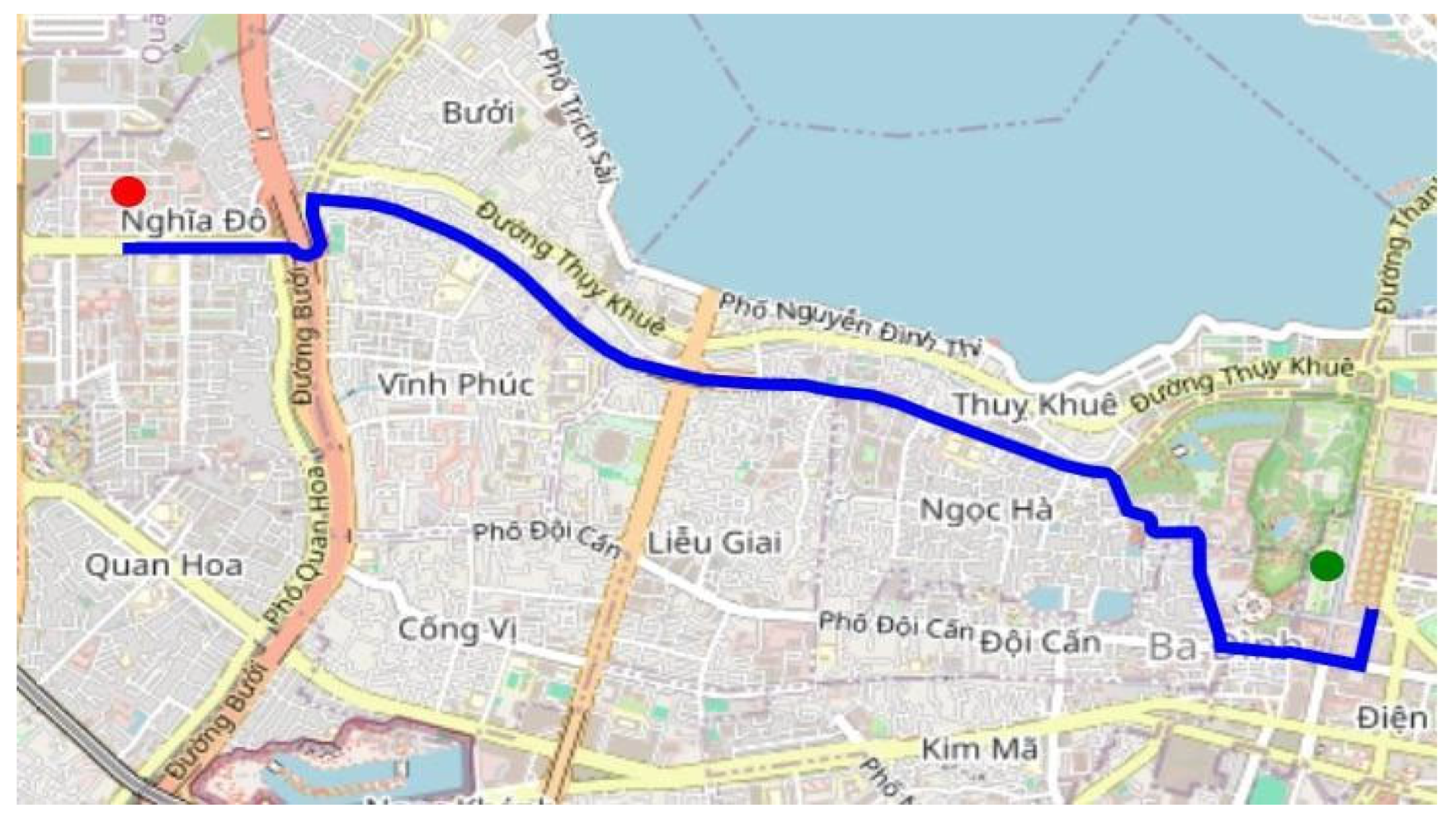

3.1. Result of System Response

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| BEV | Bird’s-eye view |

References

- Ghraizi, D.; Talj, R.; Francis, C. An overview of decision-making in autonomous vehicles. IFAC-PapersOnLine 56 2023, 2, 10971–10983. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q.P.; Luong, T.N.; Xuan, T.P.; Duc, M.T.; Van Bach, N.P.; Minh, T.P.; Trong, T.B.; Huy, H.L. Study on a method for detecting and tracking multiple traffic signals at the same time using YOLOv7 and SORT object tracking. International Conference on Robotics and Automation Engineering 2023, 8, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, P.X.; Thien, N.L.; Ngoc, P.V.B.; Vu, M.H. Research and Development of a Traffic Sign Recognition Module in Vietnam. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research. 14 2024, 1, 12740–12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y.Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, H.; Hu, L. Vehicle–pedestrian detection method based on improved YOLOv8. Electronics 13 2024, 11, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Improved YOLOv8 for small traffic sign detection under complex environmental conditions. Franklin Open 8 2024, 1, 100167. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Ma, J.; Zhao, P. SDG-YOLOv8: Single-domain generalized object detection based on domain diversity in traffic road scenes. Displays 87 2025, 1, 102944. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Guan, Z.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Y.; Sun, F. Enhanced object detection in autonomous vehicles through LiDAR—camera sensor fusion. World Electric Vehicle Journal 15 2024, 7, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtsever, E.; Lambert, J.; Carballo, A.; Takeda, K. A survey of autonomous driving: Common practices and emerging technologies. IEEE Access 8 2020, 1, 58443–58469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Chitta, K.; Geiger, A. Multi-modal fusion transformer for end-to-end autonomous driving. ArXiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Fu, W.; Song, Q.; Zhou, J. Potential risk assessment for safe driving of autonomous vehicles under occluded vision. Scientific Reports 12 2022, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Q. Evolutionary decision-making and planning for autonomous driving based on safe and rational exploration and exploitation. Engineering 33 2024, 1, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.K.; Singh, P.K.; Kumar, R. An overview of decision-making in autonomous vehicles. IFAC-PapersOnLine 56 2023, 2, 10971–10983. [Google Scholar]

- Badue, C.; Guidolini, R.; Carneiro, R.V.; Azevedo, P.; Cardoso, V.B.; Forechi, A.; Jesus, L.; Berriel, R.; Paixão, T.; Mutz, F.; Veronese, L.; De Souza, A.F. Self-driving cars: A survey. ArXiv 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Qu, X.; Lyu, N.; Li, S.E. Decision making of autonomous vehicles in lane change scenarios: Deep reinforcement learning approaches with risk awareness. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 134 2022, 1, 103452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Koltun, V.; Krähenbühl, P. Learning to drive from a world on rails. ArXiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Duhautbout, T.; Talj, R.; Cherfaoui, V.; Aioun, F.; Guillemard, F. Efficient speed planning in the path-time space for urban autonomous driving. 25th IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC) 2022, Macau, China, pp. 1268–1274.

- Sprenger, F. Microdecisions and autonomy in self-driving cars: Virtual probabilities. AI & Society 2022, 37, 619–634. [Google Scholar]

- Delling, D.; Sanders, P.; Schultes, D.; Wagner, D. Engineering route planning algorithms. In Lerner, J., Wagner, D. and Zweig, K. A. (eds), Algorithmics of Large and Complex Networks, Springer 2009, pp. 117–139.

- Fahmin, A.; Shen, B.; Cheema, M.A.; Toosi, A.N.; Ali, M.E. Efficient alternative route planning in road networks. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 25 2024, 3, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X. Deep reinforcement learning based dynamic route planning for minimizing travel time. 2021 IEEE-ICC Workshops 2021, 1–6.

- Verbytskyi, Y. Delivery routes optimization using machine learning algorithms. Eastern Europe: Economy, Business and Management 2023, 38, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alton, K.; Mitchell, I.M. Optimal path planning under different norms in continuous state spaces. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2006) 2006, 866–872.

- Choudhary, A. Sampling-based path planning algorithms: A survey. arXiv preprint.

- Ojha, P.; Thakur, A. Real-time obstacle avoidance algorithm for dynamic environment on probabilistic road map. 2021 International Symposium of Asian Control Association on Intelligent Robotics and Industrial Automation (IRIA); 2021; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F.; Rafique, S.; Khan, S.; Hasan, L., Jr. I. Smart Fire Safety: Real-Time Segmentation and Alerts Using Deep Learning. International Journal of Innovative Science and Technology (IJIST) 2024, 6, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Mulyanto, A.; Borman, R.I.; Prasetyawana, P.; Sumarudin, A. 2D LiDAR and camera fusion for object detection and object distance measurement of ADAS using Robotic Operating System (ROS). JOIV.

- Szeliski, R. Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications. Springer, 2010, p. 66.

- Li, Y.; Guan, H.; Jia, X. An interpretable decision-making model for autonomous driving. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2024, 16, 16878132241255455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Localization and Mapping Based on Multi-feature and Multi-sensor Fusion. Int.J Automot. Technol. 2024, 25, 1503–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).