Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

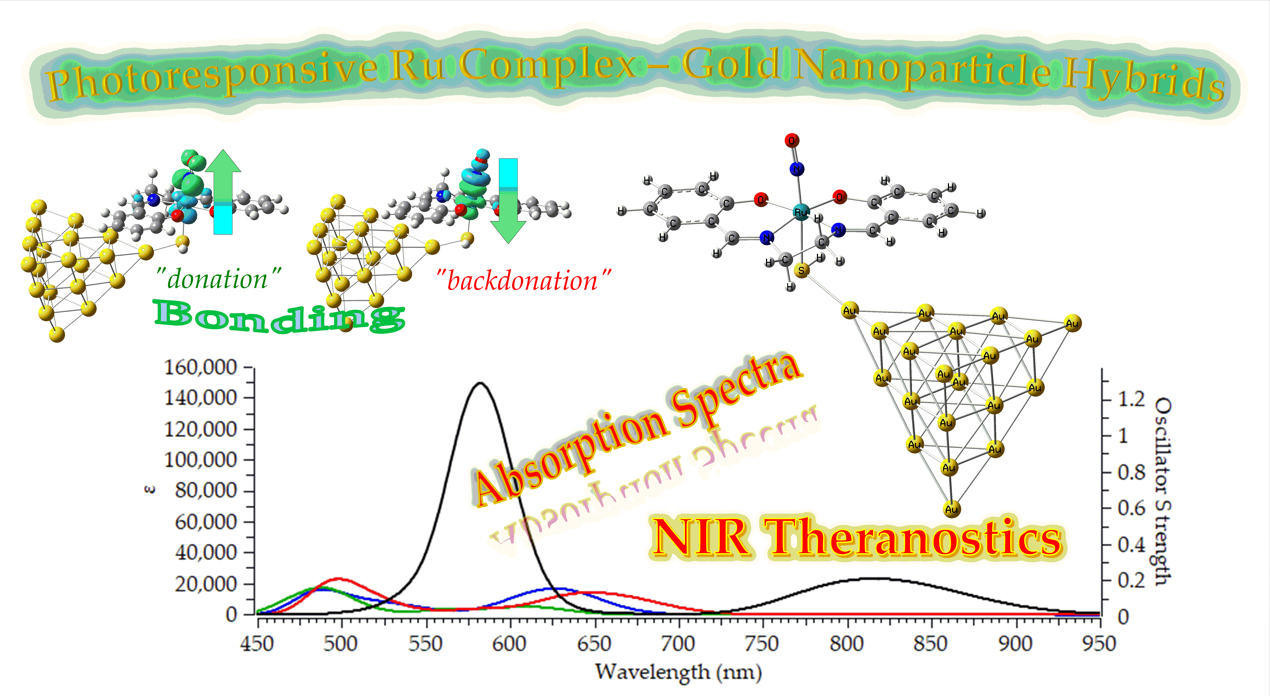

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

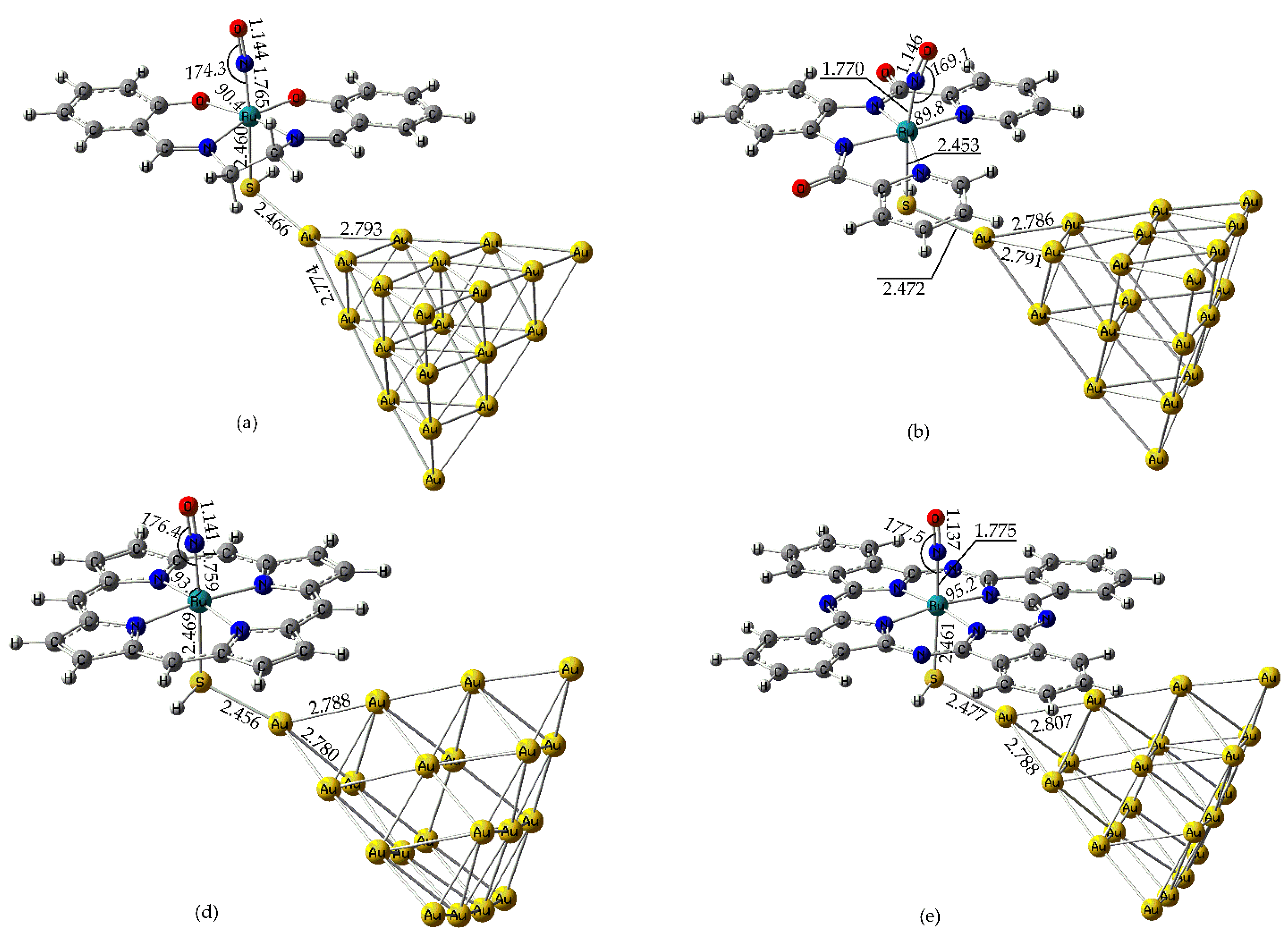

2.1. Structural Properties

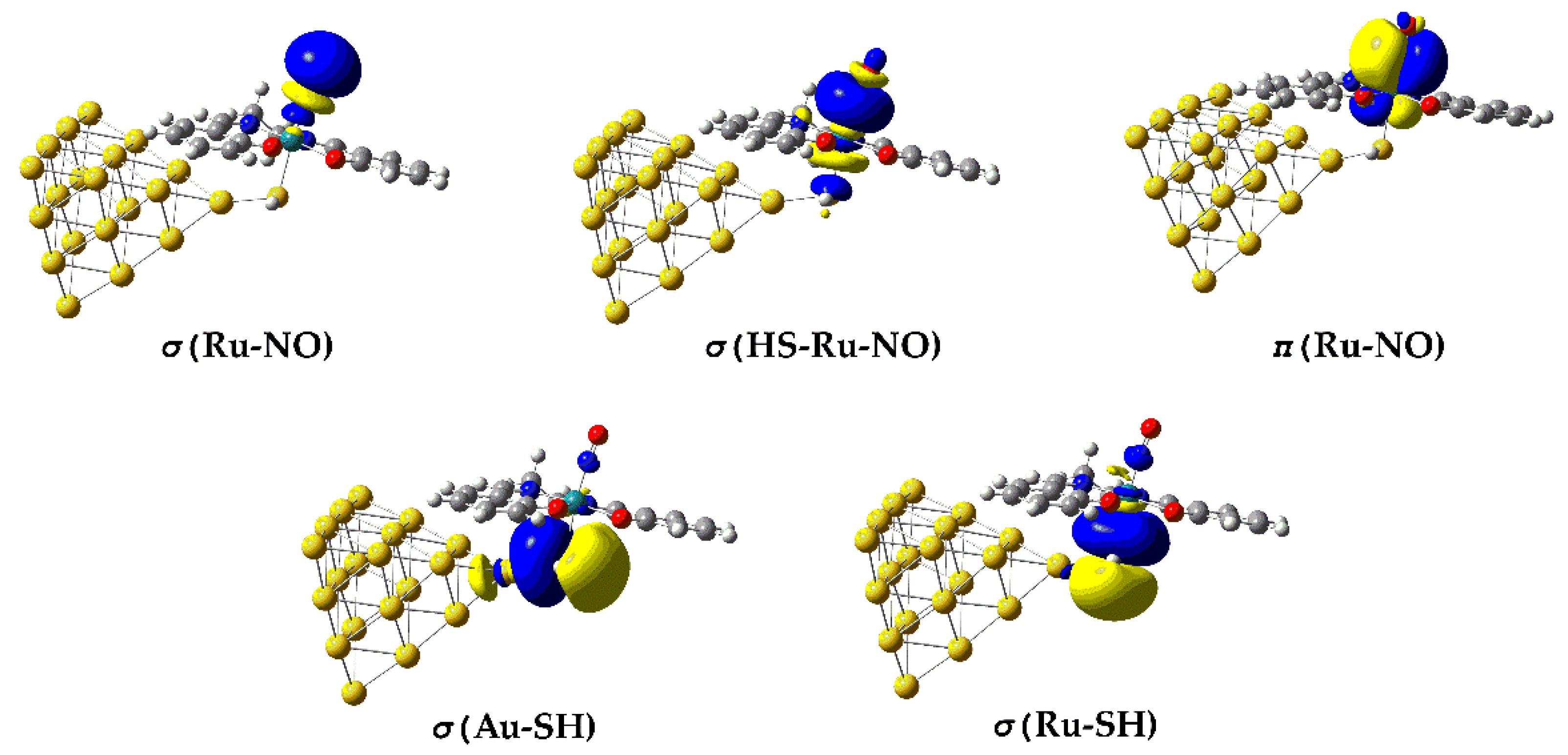

2.2. Electronic and Bonding Properties

2.2.1. NBO Analysis

2.2.2. NEDA

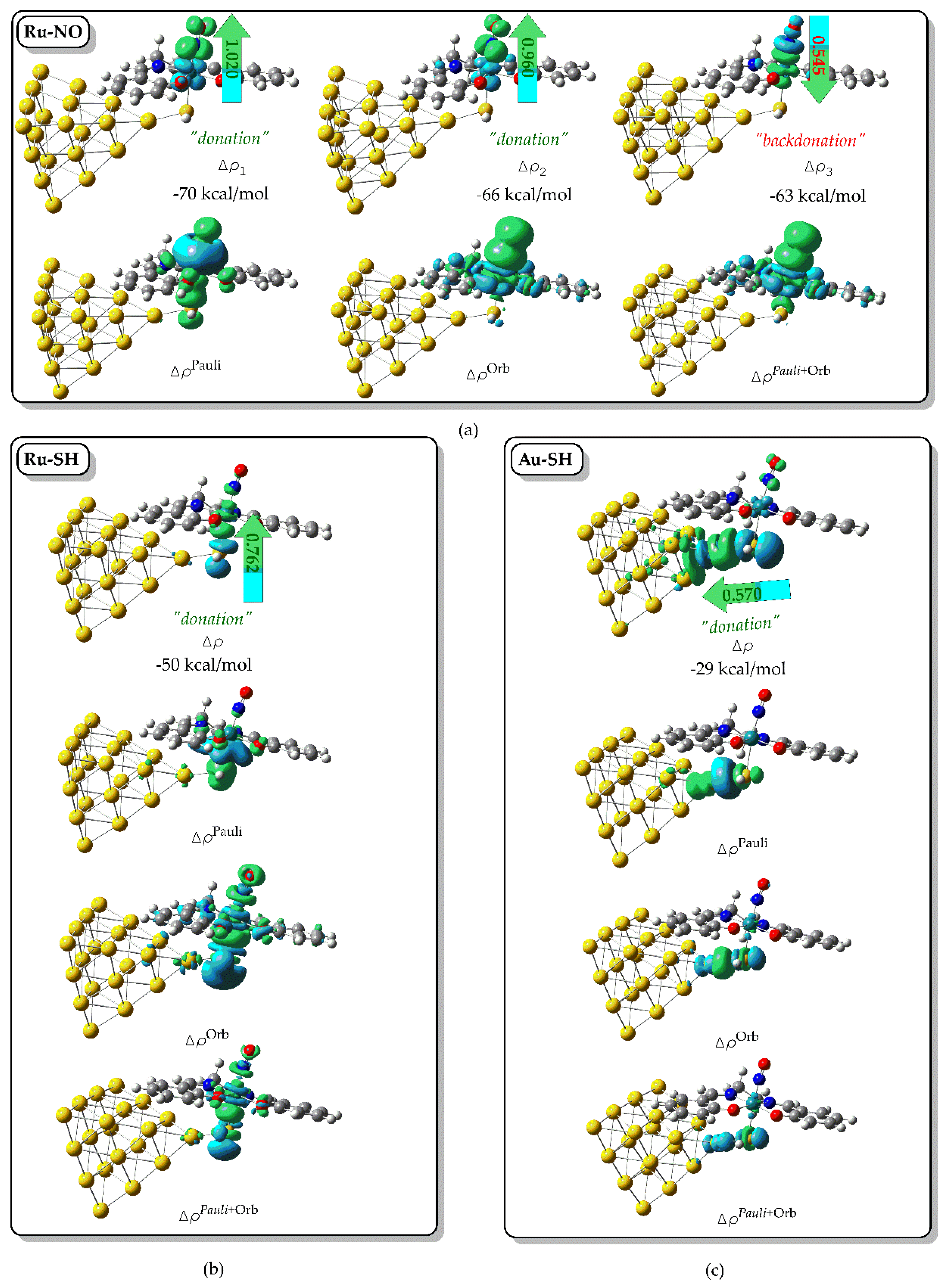

2.2.3. ETS-NOCV

2.3. Luminescence Based Detection

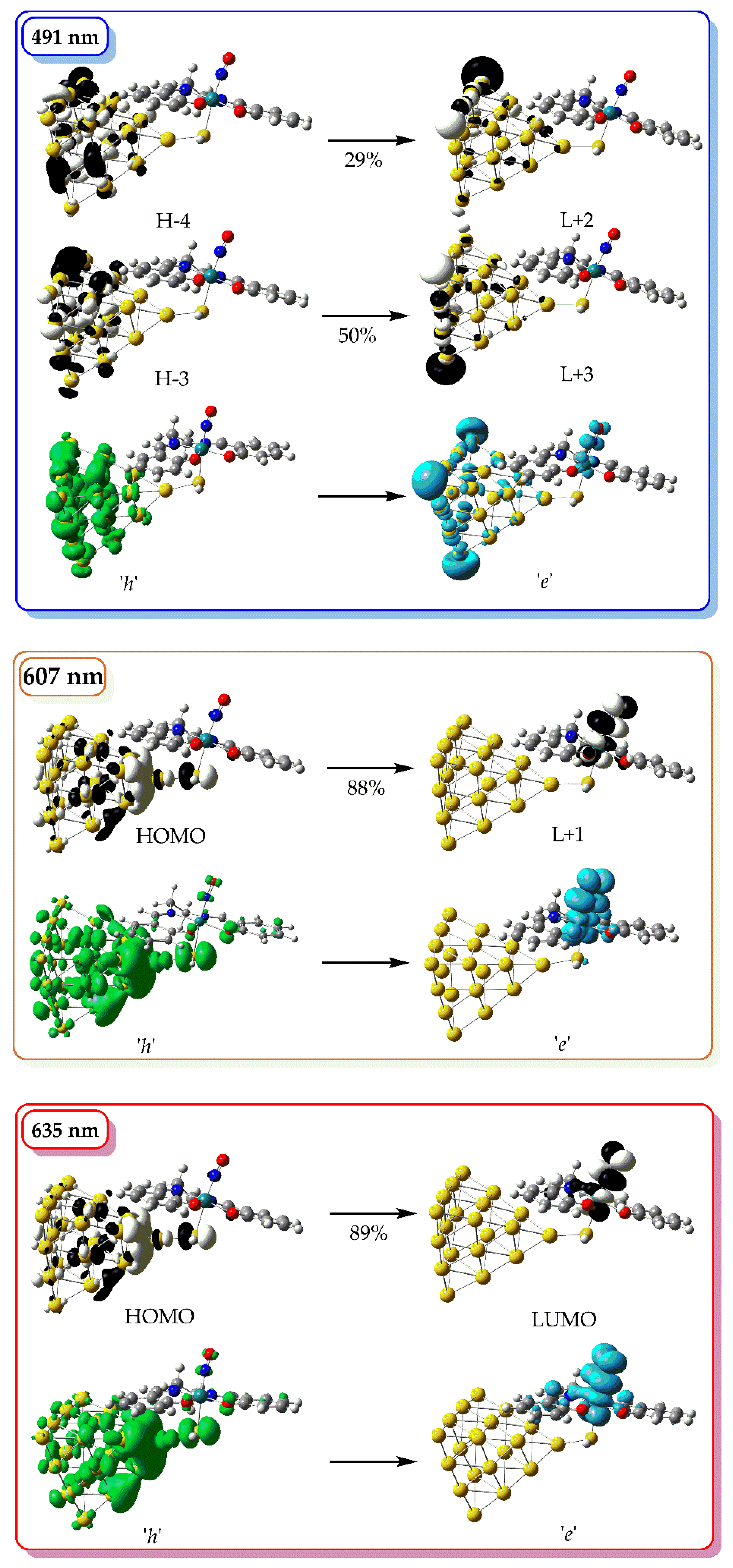

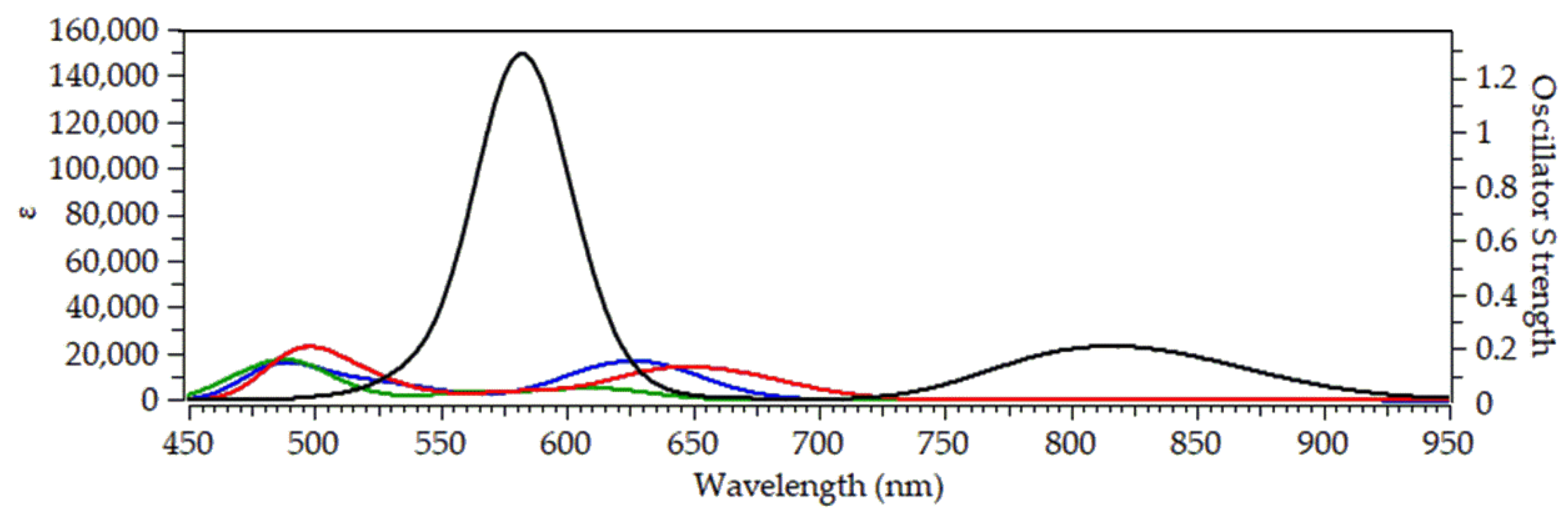

2.3.1. Absorption

2.3.2. Emission

3. Conclusions

4. Computational Details

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCleverty, J.A. Chemistry of nitric oxide relevant to biology A. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, B.; Laskin, D.L.; Heck, D.E.; Laskin, J.D. The Toxicology of Inhaled Nitric Oxide. Tox. Sci. 2001, 59, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo Jr., J.C.; Augusto, O. Connecting the Chemical and Biological Properties of Nitric Oxide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 975–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlström, M.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. Nitric Oxide Signaling and Regulation in the Cardiovascular System: Recent Advances. Pharm. Rev. 2024, 76, 1038–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.R.; Rouillard, K.R.; Suchyta, D.J.; Brown, M.D.; Ahonen, M.J.R.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Mode of Nitric Oxide Delivery Affects Antibacterial Action ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 433–441. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta, S. Nitric oxide for cancer therapy. Future Sci. 2015, 1, FSO44. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, J.; Vedenko, A.; Rosete, O.; Shah, K.; Goldstein, G.; Hare, J.M.; Ramasamy, R.; Arora, H. Current Advances of Nitric Oxide in Cancer and Anticancer Therapeutics. Vaccines 2021, 9, 94–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, J.L.; Hinsen, K.J.; Reynolds, M.M.; Smith, T.A.; Tucker, H.O.; Brown, M.A. Anticancer potential of nitric oxide (NO) in neuroblastoma treatment. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 9112–9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yoon, B.; Dey, A.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Park, J.H. Recent progress in nitric oxide-generating nanomedicine for cancer therapy. J. Contr. Rel. 2022, 352, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, P.C.; Bourassa, J.; Miranda, K.; Lee, B.; Lorkovic, I.; Boggs, S.; Kudo, S.; Laverman, L. Photochemistry of metal nitrosyl complexes. Delivery of nitric oxide to biological targets. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1998, 171, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, P.C. Polychromophoric Metal Complexes for Generating the Bioregulatory Agent Nitric Oxide by Single- and Two-Photon Excitation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, A.D.; Ford, P.C. Metal complexes as photochemical nitric oxide precursors: Potential applications in the treatment of tumors. Dalton Trans. 2009, 10660–10669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, N.L.; Mascharak, P.K. Photoactive Ruthenium Nitrosyls as NO Donors: How To Sensitize Them toward Visible Light. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levina, A.; Mitra, A.; Lay, P.A. Recent developments in ruthenium anticancer drugs. Metallomics 2009, 1, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, K.M.; Bu, X.; Lorkovic, I.; Ford, P.C. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Several Ruthenium Porphyrin Nitrosyl Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 36, 4838–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Works, C.F.; Ford, P.C. Photoreactivity of the Ruthenium Nitrosyl Complex, Ru(salen)(Cl)(NO). Solvent Effects on the Back Reaction of NO with the Lewis Acid RuIII(salen)(Cl)1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7592–7593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Works, C.F.; Jocher, C.J.; Bart, G.D.; Bu, X.; Ford, P.C. Photochemical Nitric Oxide Precursors: Synthesis, Photochemistry, and Ligand Substitution Kinetics of Ruthenium Salen Nitrosyl and Ruthenium Salophen Nitrosyl Complexes1. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 3728–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.J.; Mascharak, P.K. Photoactive ruthenium nitrosyls: Effects of light and potential application as NO donors Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 2093–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.J.; Fry, N.L.; Marlow, R.; Hink, L.; Mascharak, P.K. Sensitization of Ruthenium Nitrosyls to Visible Light via Direct Coordination of the Dye Resorufin: Trackable NO Donors for Light-Triggered NO Delivery to Cellular Targets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8834–8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.J.; Olmstead, M.M.; Mascharak, P.K. Photosensitization via Dye Coordination: A New Strategy to Synthesize Metal Nitrosyls That Release NO under Visible Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5342–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.J.; Mascharak, P.K. Photosensitization of Ruthenium Nitrosyls to Red Light with an Isoelectronic Series of Heavy-Atom Chromophores: Experimental and Density Functional Theory Studies on the Effects of O-, S- and Se-Substituted Coordinated Dyes. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 6904–6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauaia, M.G.; de Lima, R.G.; Tedesco, A.C.; da Silva, R.S. Photoinduced NO Release by Visible Light Irradiation from Pyrazine-Bridged Nitrosyl Ruthenium Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 14718–14719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauaia, M.G.; de Lima, R.G.; Tedesco, A.C.; da Silva, R.S. Nitric Oxide Production by Visible Light Irradiation of Aqueous Solution of Nitrosyl Ruthenium Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 9946–9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, C.; Cifuentes, M.P.; Humphrey, M.G. Transition metal complex/gold nanoparticle hybrid materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2316–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, C.; Morshedi, M.; Wang, H.; Du, J.; Cifuentes, M.P.; Humphrey, M.G. Exceptional Two-Photon Absorption in Alkynylruthenium–Gold Nanoparticle Hybrids. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hone, D.C.; Walker, P.I.; Evans-Gowing, R.; Fitzgerald, S.; Beeby, A.; Chambrier, I.; Cook, M.J.; Russell, D.A. Generation of Cytotoxic Singlet Oxygen via Phthalocyanine-Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles: A Potential Delivery Vehicle for Photodynamic Therapy. Langmuir 2002, 18, 2985–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, S.; Moeno, S.; Antunes, E.; Nyokong, T. Effects of gold nanoparticle shape on the aggregation and fluorescence behaviour of water soluble zinc phthalocyanines. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Claire, S.; Teixeira, R.I.; Dosumu, A.N.; Carrod, A.J.; Dehghani, H.; Hannon, M.J.; Ward, A.D.; Bicknell, R.; Botchway, S.W.; Hodges, N.J.; Pikramenou, Z. Iridium Nanoparticles for Multichannel Luminescence Lifetime Imaging, Mapping Localization in Live Cancer Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 10242–10249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Calavia, P.; Bruce, G.; Perez-Garcia, L.; Russell, D.A. Photosensitiser-gold nanoparticle conjugates for photodynamic therapy of cancer. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 1534–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Moreira, V.; Thorp-Greenwood, F.L.; Coogan, M.P. Application of d6 transition metal complexes in fluorescence cell imaging. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, R.; et al. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10346–10413. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häkkinen, H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1847–1859. [CrossRef]

- Molina, B.; et al. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 16486–16494. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhai, H.-J.; Wang, L.-S. Science 2003, 299, 864–867. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Acevedo, O.; et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12597–12604. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Frisch, M.J., Trucks, G.W., Schlegel, H.B., Scuseria, G.E., Robb, M.A., Cheeseman, J.R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Petersson, G.A., Nakatsuji, H., et al., Eds.; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vetere, V.; Adamo, C.; Maldivi, P. Performance of theparameter free’PBE0 functional for the modeling of molecular properties of heavy metals. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 325, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Inexpensive and accurate predictions of optical excitations in transition-metal complexes: The TDDFT/PBE0 route. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2000, 105, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernzerhof, M.; Scuseria, G.E. Assessment of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Scuseria, G.E.; Barone, V. Accurate excitation energies from time-dependent density functional theory: Assessing the PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 111, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunning, T.H., Jr.; Hay, P.J. Modern Theoretical Chemistry; Schaefer, H.F., III, Ed.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1977; Volume 3, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, P.J.; Wadt, W.R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for the transition metal atoms Sc to Hg. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.J.; Wadt, W.R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for main group elements Na to Bi. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.J.; Wadt, W.R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Curtiss, L.A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gisbergen, S.J.A.; Kootstra, F.; Schipper, P.R.T.; Gritsenko, O.V.; Snijders, J.G.; Baerends, E.J. Density-functional-theory response-property calculations with accurate exchange-correlation potentials. Phys. Rev. A At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1998, 57, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamorski, C.; Casida, M.E.; Salahub, D.R. Dynamic polarizabilities and excitation spectra from a molecular implementation of time-dependent density-functional response theory: N2 as a case study. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 104, 5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauernschmitt, R.; Ahlrichs, R. Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time dependent density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 256, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Jacquemin, D. The calculations of excited-state properties with Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comp. Chem. 2012, 33, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Tenderholt, A.L.; Langner, K.M. Cclib: A library for package-independent computational chemistry algorithms. J. Comp. Chem. 2008, 29, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | [(L)Ru(NO)(SH)@Au20] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L = Salen | L =bpb | L = porph | L = pc | |

| QRu | 0.695 | 0.582 | 0.597 | 0.552 |

| QN | 0.363 | 0.338 | 0.400 | 0.388 |

| QS | -0.474 | -0.446 | -0.452 | -0.441 |

| QAu | 0.065 | 0.061 | 0.083 | 0.059 |

| WBI(Ru-NO) | 1.242 | 1.216 | 1.252 | 1.204 |

| WBI(N-O) | 1.948 | 1.926 | 1.965 | 1.980 |

| WBI(Ru-S) | 0.485 | 0.481 | 0.479 | 0.493 |

| WBI(S-Au) | 0.272 | 0.265 | 0.266 | 0.246 |

| L | Bond | ES | POL | CT | XC | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru-N | -75.1 | -212.0 | -520.5 | -75.5 | -201.0 | |

| [(salen)Ru(NO)(SH)@Au20] | Ru-S | -119.6 | -130.7 | -161.6 | -67.6 | -96.7 |

| Au-S | -74.4 | -45.1 | -85.7 | -56.3 | -28.3 | |

| Ru-N | -95.7 | -187.5 | -525.2 | -76.5 | -202.0 | |

| [(bpb)Ru(NO)(SH)@Au20] | Ru-S | -127.0 | -128.0 | -165.3 | -66.9 | -102.2 |

| Au-S | -73.2 | -44.0 | -82.5 | -54.2 | -27.6 | |

| Ru-N | -79.2 | -220.7 | -521.7 | -78.2 | -195.8 | |

| [(porph)Ru(NO)(SH)@Au20] | Ru-S | -115.5 | -125.8 | -162.2 | -67.7 | -88.5 |

| Au-S | -74.4 | -47.9 | -85.1 | -56.9 | -27.4 | |

| Ru-N | -66.2 | -218.5 | -500.3 | -75.9 | -180.8 | |

| [(pc)Ru(NO)(SH)@Au20] | Ru-S | -119.1 | -139.6 | -184.9 | -75.2 | -93.5 |

| Au-S | -90.8 | -56.3 | -90.8 | -61.8 | -22.6 |

| Complex | λvib (eV) | E0-0 (nm) | ΔES0-T1 (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [(salen)Ru(NO)(SH)@Au₂₀] | 0.790 | 1931 | 1733 |

| [(bpb)Ru(NO)(SH)@Au₂₀] | 0.837 | 1803 | 1643 |

| [(porph)Ru(NO)(SH)@Au₂₀] | 0.866 | 2232 | 1972 |

| [(pc)Ru(NO)(SH)@Au₂₀] | 0.760 | 3737 | 3010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).